New Approaches to Economic Challenges (NAEC)

Abstract

Policymakers often have a linear view of the world, where pulling the right levers will get the economy and society back on track after shocks and crises. This paper argues that such an approach ignores how systems interact and how their systemic properties shape this interaction, leading to an over-emphasis on a limited set of characteristics, notably efficiency. The emphasis on efficiency in the operation, management and outcomes of various economic and social systems was not a conscious collective choice, but rather the response of the whole system to the incentives that individual components face. This has brought much of the world to rely upon complex, nested, and interconnected systems to deliver goods and services around the globe. While this approach has many benefits, the Covid-19 crisis shows how it has also reduced the resilience of key systems to shocks, and allowed failures to cascade from one system to others. A systems approach based on resilience is proposed to prepare socioeconomic systems for future shocks.

“Everything we do before a pandemic will seem alarmist, everything we do after a pandemic will seem inadequate.” US Health and Human Services Secretary Michael Leavitt in 2007

Recent decades have emphasised efficiency in the operation, management and outcomes of various economic and social systems. This was not a conscious collective choice, but the response of the whole system to the incentives that individual components face. As a result, much of the world now relies on complex, nested, interconnected systems to deliver goods and services. While this has provided considerable opportunities, it has also made the systems we rely on in our daily lives (e.g., international supply chains) vulnerable to sudden and unexpected disruption (Juttner and Maklan, 2011; OECD and FAO, 2019). In complex systems, tensions exist between efficiency and resilience, the ability to anticipate, absorb, recover, and adapt to unexpected threats. Resilience is a focus of specific parts of some systems, for instance military and health systems, but some systemic risks are the consequence of attempts to maximise efficiency in subsystems leading to suboptimal efficiency at higher levels.

The Covid-19 outbreak is the first global pandemic to be caused by a coronavirus, leading to a crisis with considerable losses in terms of health but also to much of the global economy, with high social costs. The pandemic has reminded us bluntly of the fragility of some of our most basic human-made systems. Shortages of masks, tests, ventilators and other essential items have left frontline workers and the general population dangerously exposed to the disease itself. At a wider level, we have witnessed the cascading collapse of entire production, financial, and transportation systems, due to a vicious combination of supply and demand shocks.

At the moment, national governments are struggling to absorb the shock generated by the pandemic, but in time the international community will overcome the crisis and begin the recovery phase. The OECD response to help them in this process has been twofold: address immediate concerns, and propose an approach to dealing with the longer-term issues the pandemic highlights. In the short term, that means identifying the people and activities most affected, assessing how measures to help them will impact others, and underlining that difficult trade-offs between health, economic, social, and other goals are inevitable. In the longer term, an approach that reacts to the systemic origins and impacts of major shocks is needed if policies are to be effective.

The Covid-19 crisis also shows how important it is to keep resources in reserve for times when unexpected upheavals in the system prevent it from functioning normally. Furthermore, given the interdependence of economic and social systems, the pandemic also highlights the need for strengthened international co-operation (building on existing frameworks for emergency preparedness) based on evidence, to tackle systemic threats and help avert systemic collapse.1 Helbing (2012) and others have noted that the consequences of failing to appreciate and manage the characteristics of complex global systems and problems can be immense.

The Covid-19 Outbreak

The New Approaches to Economic Challenges (NAEC) Group Conference in September 2019 on Averting Systemic Collapse identified how growing complexity and interdependence has made various systems (economic, public health, cyber, etc.) susceptible to widespread, irreversible, and cascading failure. Aspiring for maximum efficiency and optimisation, such systems have neglected resilience against disruptions whose shocks may leave governments, the public, and the environment in a weakened state. More specifically, the concentration of industrial capacities and economic activity into smaller and more efficient sectors, up to the international level, has produced highly lucrative yet fragile supply chains, and economic exchanges whose disruptions could have significant effects in unexpected areas.

Such notions have been thoroughly described by leading economists and scholars since the onset of the 2007-2009 Financial Crisis, yet primarily in an abstract context. A key question was not whether systemic risk would cause substantial cascading losses to the international economy, but what type of disruption would trigger such a chain of events in the first place. One answer is the 2019-2020 coronavirus outbreak. Declared a pandemic by the World Health Organisation (WHO) on 11 March 2020, Covid-19 quickly spread globally. The NAEC conference on Integrative Economics on 5-6 March 2020 highlighted that the outbreak was an example of a long-standing message of NAEC. We are not living in a linear, Newtonian world where actions cause predictable reactions. We are in fact part of a complex system of environmental, socio‑political and economic systems that we are constantly reconfiguring and that is constantly affecting us. In such a world, a small change can be transmitted and amplified by the interconnectedness of the system to have enormous consequences, far beyond the time, place, and scale of the initial perturbation. We saw this in 2007-2008 when problems in a national home loans market escalated into a financial crisis that almost destroyed the global banking system. Ten years later, we are still suffering the consequences of the 2008 crisis because it provoked an economic recession and widening inequalities that in turn caused political and social upheaval.

The Covid-19 crisis is another illustration of how systems change each other. The initial cause, as in previous coronavirus outbreaks, was transmission from animals to human of a virus. When we look in more detail at how this happened, we will probably find that a range of social, economic, and environmental changes contributed to creating the conditions where zoonosis could become so damaging – changing land-use patterns and agricultural practices for instance - but more immediately, legal and illegal wildlife trade. But we should not stop at the immediate interactions. We could argue that the 2020 health crisis was made far worse by the 2008 financial crisis, or more precisely, the austerity measures that left many health systems without the basic human and other resources needed to cope with a sudden, unexpected rise in the number of patients.

Covid-19 also shows how subjective or cultural factors such as trust in institutions and willingness to follow their advice and instructions, the sentiment of belonging to a community or the type of neighbourhood, can influence how a disaster unfolds. A full understanding of such factors requires an approach based on integrative economics, which calls on the insights and methods of the range of disciplines needed to paint a realistic picture of how the economic system is shaped and helps shape the larger “system of systems” it is part of. Furthermore, systems thinking allows us to identify the key drivers, interactions, and dynamics of the economic, social, and environmental nexus that policy seeks to shape, and to select points of intervention in a selective, adaptive way. Critically, this allows us to emphasise the importance of system resilience to a variety of shocks and stresses, allowing systems to recover from lost functionality and adapt to new realities regarding international economics, societal needs, and human behaviour and the risks of a more unpredictable climate.

For example, the nuclear power industry in OECD countries relies on a safety philosophy known as “integrated defence in depth.” This framework requires consideration of not just reactor design and hardware performance but also the human and organisational elements (e.g. emergency response organisations) necessary for safe reactor operation (NEA, 2016). This framework, consistent with integrative economics, assesses overall system resilience, while recognising that one must consider a variety of complex, interconnected variables. Energy supply security, that demands a policy response from government, may offer additional insights. Most electricity systems are, as a result, resilient by law: mandatory levels of additional dispatchable capacity are kept in reserve should the output of some technologies, or individual plants, become variable.

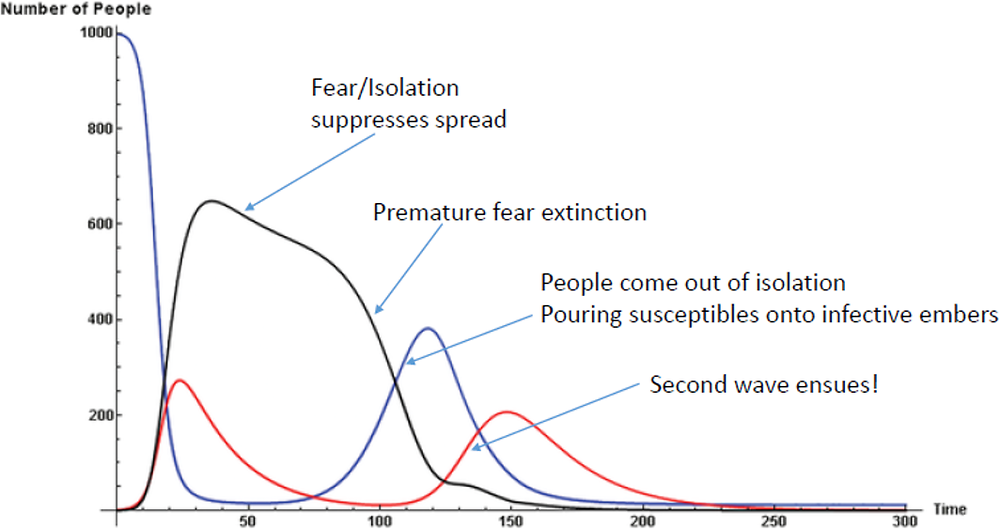

The ability to react to changing demand is crucial in health care systems too. Ferguson et al (2020) provided simulations of Covid-19’s diffusion which indicated that the United Kingdom’s health service would be overwhelmed and might face 500,000 deaths if the government took no action. This led to the implementation of restrictions on social movement. Using a similar modelling approach, simulations for the United States suggested 2.2 million deaths if no actions were taken. After it was shared with the White House, new guidance on social distancing was issued. Epidemiologist Joshua Epstein from New York University outlined the global spread of pandemics with a focus on Covid-19 in which the interaction between the infection dynamics (created by the pandemic) and the social dynamics (created by fear) – what he terms as a “coupled contagion”- produce volatile outcomes.2 Individuals contract fear through contact with the disease-infected (the sick), the fear‑infected (the scared), and those infected with both fear and disease (the sick and scared). Scared individuals - whether sick or not - withdraw from circulation with a certain probability, which affects the course of the disease epidemic proper. If individuals recover from fear and return to circulation, the disease dynamics become rich, and include multiple waves of infection, such as occurred in the 1918 Influenza Pandemic (see figure below) (Epstein, 2014).

Source: Epstein JM, Parker J, Cummings D, Hammond RA (2008) Coupled Contagion Dynamics of Fear and Diseas: Mathematical and Computational Explorations, PLOS ONE 3(12): e3955. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003955.

One could push the argument further, using the example of financial system. The two contagions – the virus and fear – operate in tandem and the behaviour of individuals is changed. The movements in capital markets engendered by the change in decisions of market participants, who were originally affected neither by the virus or fear of it, may set off an epidemic of market movements. This can lead, as we have observed recently, to a crash of unprecedented proportions.

What are the impacts?

Economic

The OECD Interim Economic Outlook released on 2 March 2020 showed how restrictions on movement of people, goods and services, added to containment measures such as business closures, cut manufacturing and domestic demand sharply in China, and how the impact on the rest of the world was growing through business travel and tourism, global supply chains, commodities, and loss of confidence.

The initial direct impact of the shutdowns could be a decline in the level of output of between one-fifth to one-quarter in many economies, with consumer expenditure potentially dropping by around one-third. This is far greater than anything experienced during the 2008 financial crisis. And this estimate only covers the initial direct impact in the sectors involved and does not take into account any additional indirect impacts. Nonetheless, it is clear that the direct impact of the shutdowns imposed on many economies will weaken short-term growth prospects substantially, equivalent to a decline in annual GDP growth of up to 2 percentage points for each month of containment, not taking into account the potentially large indirect impact (loss of confidence etc.)3. If the shutdown continued for three months, with no offsetting factors, annual GDP growth could be between 4-6 percentage points lower than it otherwise might have been. However, the worst potential impacts may be offset by measures such as the USD 5 trillion in fiscal spending the G20 countries agreed to inject into the global economy at their summit on 26 March 2020.

The Covid-19 epidemic and measures to counteract it are likely to disproportionally affect poorer people. “How’s Life?” 2020 shows that 36% of people in OECD countries are financially vulnerable, meaning they lack the financial assets needed to avoid falling into poverty if they lost 3 months of their income. This figure climbs to over 60% in some OECD countries. Those working in the “gig economy” are among the most exposed to the economic fall-out. These workers often work on short contracts, sometimes with weak or no social protections, with limited options for working remotely, and with risks of job loss and forgone earnings if they have to remain away from their place of work due to illness, quarantine, or government-mandated closures of specific activities. Anti-virus measures will affect them significantly since they are often employed in occupations demanding a high degree of contact with a wide range of clients, such as restaurants, taxis, and delivery services.

Measures to compensate people and firms for lost earnings, involving postponement of taxes, and debt repayments and government paid leave for people in countries which do not have paid sick leave, will alleviate the situation. But in economies dominated by short-term contracts and where poorer people have little or no savings, no amount of monetary stimulus will re-energise demand. Furthermore, informal workers (except agriculture), who make up 60% of employment globally and 90% in developing countries will likely suffer massive layoffs due to the supply-demand shock even before the severity of the pandemic reaches them.

A re-examination of social protection systems and social contracts might be needed in the longer term. Nevertheless, as an immediate and practical response, conditional cash transfers were scaled up very effectively following the Global Financial crisis and even in LDCs, food for work programmes and other forms of social protection can provide some relief. On the supply side of the economy, firms that have had to reduce their activities will take time to restart production and contribute to global supply chains.

In the longer term, the following impacts could be especially serious for the economy.

The first is the impact on international relations and the vectors of globalisation. China’s merchandise trade was down 17% in the first two months of 2020. While trade may rebound when the situation improves, there may be longer term, structural effects: firms may retreat from globalisation, seeking shortened supply chains and suppliers located in countries that seem less prone to disruption or they may reshore manufacturing. This would have consequences for production structures, jobs, and income in different parts of the world. This adds business reasons to the more political reasons that have already led to a backlash against globalisation in recent years, partly because globalisation hasn’t delivered well-being for all, and partly because a number of countries have embraced trade protectionism and border controls. This is worrying when international cooperation is literally vital in coordinating the response to Covid-19 and future systemic threats. Unfortunately, the mechanisms that might provide a coordinated international response do not exist, except for limited monetary arrangements.

The international financial system is already seeing the impacts of Covid-19, with increased volatility and sharp drops in share prices. If these falls are the beginning of a longer downward trend, there is a direct negative wealth impact on asset holders. This may in particular affect funded pensions and pensioners' living standards. Further easing of monetary policies by central banks (especially by the ECB where deposit rates are already negative) may reinforce the income effect for pensioners or push savers to higher risk investment. On the other hand, low interest rates may further fuel inflation in assets that are considered safe havens (real estate, gold, government bonds) making inequalities in wealth worse. Covid-19 has exposed the vulnerability in financial markets, with corporate debt doubled since the 2008 financial crisis to now reach a record 47% of GDP. These companies will struggle to repay the debt given the lockdown and breakdown in supply chains.

Once again, the shadow of 2008 falls over the outlook today. The IMF’s Global Debt Database shows that total global debt (public plus private) reached USD188 trillion at the end of 2018, up by USUSD3 trillion when compared to 2017 (and up by over USD90 trillion from 2007).4 The global average debt-to-GDP ratio (weighted by each country’s GDP) edged up to 226 percent in 2018, 1½ percentage points above the previous year. Despite efforts to reduce fiscal deficits, many governments still have high levels of debt following their interventions to deal with the financial crisis and its aftermath, and sovereign spreads for some countries are starting to widen. Private debt, encouraged by low interest rates, is even more worrying. In advanced economies IMF data show that the corporate debt ratio has gradually increased since 2010 and it is now at the same level as in 2008, the previous peak. In several major economies debt is, or was, increasingly used for financial risk-taking (to fund distribution of dividends, share buybacks, and merger and acquisitions). Much of the debt is high speculative-grade debt, and a significant fraction of corporate debt is now rated BBB, the lowest investment grade rating. Almost half of all US corporate bonds maturing in the next five years are below investment grade. Global household debt is over USD47 trillion, compared to USD35 trillion going into the 2008 crisis.

Producing a vaccine is relatively simply, but before getting to the production phase, a number of actors including researchers, producers, governments, and purchasers will have played a role in a complex supply chain. The traditional way to look at developing vaccines (or other drugs) was to think of it as a linear process, a “pipeline”. This gives the impression of an orderly progression from identifying a need to fulfilling it, with one step following the other in a predictable sequence. In fact, rather than a pipeline, a better metaphor is an ecosystem, where “no part of the value chain is viable on its own accord, but depends on the success of the other parts in a systemic manner.”1

A systems approach to vaccines would integrate a strong anticipation component to understand how the different parts of the ecosystem interact. “Springing into action” after a disaster is a poor substitute for being prepared. As the OECD argued in a recent report on New Health Technologies2, “many early awareness and alert initiatives rely on describing technologies in the pipeline, pushed by industry, providers and other actors. Member countries should be more proactive in defining public health needs and research agendas to help build the right incentives for technology development, especially when the market will not do it.”

When an alert is given, emergence would be a particularly important system property to consider in order to understand the origins of the disease a vaccine was being sought for. Emergence refers to a situation that arises through the interaction of a number of actors and influences, without any intention to create that situation. Covid-19 may have been an unintended consequence of interactions among the agriculture and food system, changing land use patterns, and loss of habitat that brought animals into closer and more frequent contact with humans.3

The response once the danger was identified is a particularly powerful illustration of the ecosystem model of how systems react, and what they react to. The latest report from CEPI, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations4 identifies 115 Covid-19 candidates in various stages of development as of 8 April 2019. The best candidate may turn out to be derived from research that was started for a totally different condition, or even no particular condition at all. The UK antimicrobial resistance review recognised this in recommending the creation of a “Global Innovation Fund for early-stage and non-commercial research. This fund will support “blue sky” research as well as work focused on neglected areas such as vaccines and diagnostics.”5

However, in developing vaccines, the logics of different systems often clash, notably around the costs and risks of development versus the expected benefits. This is one reason why CEPI was established in 2016. It is a global partnership between public, private, philanthropic, and civil society organisations, created after the Ebola epidemic showed that the usual market processes for developing vaccines would not produce the medicines needed to deal with new types of epidemics. As the OECD report on new health technologies puts it, “Pharmaceutical companies will not develop new products if the market isn’t attractive enough”, so governments will have to pay more.

In deciding whether to do so, governments should consider at least two ways in which economics interacts with vaccines. The broader systemic approach is to say that vaccines are an investment that will make people and the socio-economic system more resilient, and not just to disease. Better health is an example of a positive feature cascading through different systems. The fight against malaria provides countless examples, ranging from the “growth penalty” of up to 1.3% per year the disease has been calculated to inflict on some African countries6, to poorer educational outcomes and therefore life chances for infected children.

There is also a more specific systems analysis to be made in the case of an epidemic such as Covid-19. The pharmaceutical industry invokes the uncertainty of drug production to justify patent protection and high prices on new products. But for Covid-19, the research is publicly funded, and governments could also finance the following stages through clinical trials and approval, paying manufacturers simply to make the treatments. In that case, the benefits and protections of the patent system would have to be examined in relation to that system’s contribution to the common good.

Health and social impacts

The elderly are the most affected, but the effects on them do not depend on biological factors alone. A number of factors contribute to the total impact. The elderly are exceptionally exposed to death from the disease, but also risks arising from isolation and weak social ties, compounded by the fragmentation of health and social care services. Nearly one-third of adults aged 65 and older in many G20 countries are estimated to live alone (and twice as many elderly women live alone compared to men, and they generally have lower pensions). Older people are almost three times more likely to lack social support than younger people, and if they do fall ill, it may take longer to detect, and care at home may be impractical. This is, of course, highly dependent on the country in question, and older people are much better cared for in those with a better social safety net.

School closures are the main impact on children and young people, but the capacity and adaptability to compensate for the projected loss in learning varies according to socio-economic profiles of students and schools, with those from low-income and/or single-parent families likely to be the most affected by the closure of schools and childcare facilities as well as a full transition to digital learning. The PISA 2018 surveys reveal that on average across OECD, only 69% of 15-year-old socio-economically disadvantaged students – as opposed to 90% of advantaged students – have a quiet place to study at home and a computer to use for schoolwork. The poorest children will also suffer by being deprived of school meals and other support measures based on schools. During the Covid-19 epidemic, despite government efforts, online courses and classes will be difficult to access for disadvantaged students. Tackling the digital divide between students from different backgrounds, by providing them with free or affordable devices and internet access for example, would provide an example of how action to tackle a crisis could make a system more resilient, and better suited to its mission than before, what we call “bouncing forward” below. Ultimately, resilience in education could be developed through building of skills and competencies in individuals and groups, but this requires a differentiated strategy to make up for the unequal starting conditions.

Comparing country responses to Covid-19

Evidence-based policy relies on data, but in the case of Covid-19, the basic statistics on the number of cases are unreliable due to insufficient testing, unreported cases, asymptomatic cases, and countries deliberately under-reporting cases. The OECD is however tracking four key measures that health systems in member countries are putting in place in response to the epidemic,5 while emphasizing that data on the cost-effectiveness of containment and mitigation policies is still limited. The measures tracked are: ensuring access of the vulnerable to diagnostics and treatment; strengthening and optimising health system capacity to respond to the rapid increase in caseloads; digital solutions and data to improve surveillance and care; and R&D for accelerated development of diagnostics, treatments and vaccines.

Success in dealing with the epidemic depends on a combination of socioeconomic and political factors that include the state of the health system before the outbreak, social norms, the rapidity and intensity policy responses such as lockdowns, and testing.

Korea combines a number of the characteristics that appear to favour an effective response, for example a tradition of wearing face masks to prevent spreading colds and other diseases. Legislation had already established a comprehensive framework to address infectious diseases and coordinate government and lower-level responses, including on how to allocate resources and collect data. In a statement issued on April 156, the Korean government explained its success as a result of the third of the measures the OECD is tracking, digital solutions: “Mobile devices were used to support early testing and contact tracing. Advanced ICTs were particularly useful in spreading key emergency information on novel virus and help to maintain extensive ‘social distancing’. The testing results and latest information on Covid-19 was made available via national and local government websites. The government provided free smartphone apps that flagged infection hotspots with text alerts on testing and local cases.”

Germany’s first outbreak of locally transmitted Covid-19 was around January 22, a month before Italy’s first reported case, but Germany has recorded just over 2000 deaths at the time of writing, compared with nearly 18,000 in Italy. The German government attributes some of its success to its National Pandemic Preparedness Plan.7 The response included a health ministry information campaign and widespread testing. Deutsche Welle (DW), Germany’s international broadcaster, suggests that the way health care is managed under country's federal system of government may explain some of the country’s success, with hundreds of health officials overseeing the pandemic response across the 16 states, rather than one centralised response from the national health ministry.

The importance of regional authorities is also highlighted in Italy, where the Veneto region has been successful, thanks to broad testing of symptomatic and asymptomatic cases, active tracing of possible positives, and a strong emphasis on home diagnosis and care to reduce the load on hospitals. Central government does have to recognise its responsibilities though.

Comparing what we know of successes and failures so far enables the OECD to draw some policy conclusions for health care management:

The Covid-19 crisis demonstrates the importance of universal health coverage as a key element for the resilience of health systems. High levels of out-of-pocket payments may deter people from seeking early diagnosis and treatment, and thus contribute to an acceleration in the rate of transmission.

Planning for a “reserve army” of health workers, which was introduced in several countries after previous epidemics, has proven to be very useful to provide additional support to the regular workforce and allows for a more flexible management of human resources across regions.

Crisis situations like the coronavirus epidemic can provide opportunities to change the traditional roles of different health care providers and expand the roles of some providers like nurses and pharmacists, so that they can take on some of the tasks from doctors and thereby allow them to spend their time more effectively on the most complex cases.

Strategic reserves of masks and other protective equipment may be considered to avoid exposing doctors and other health workers to high risk of infections.

Use routine and big data for early warning and surveillance as well as digital diagnosis and take advantage of digital technologies to advise the public and limit physical contacts as well as to monitor people who have been diagnosed.

Use new approaches, including through AI and machine learning, to accelerate and improve the effectiveness of R&D efforts. For example, explore whether drugs used for one pathology could be useful in treating others.

Prepare fast-track regulatory and emergency approval pathways for new diagnostic tests and treatments. Regulatory agencies should also agree that they will co-ordinate their efforts internationally to ensure that evidence used for approval in one jurisdiction is sufficient for others, rather than applying different standards.

Governments should allocate public funding to build capacity to produce vaccines and treatments before regulatory approval, in exchange for commitments from industry to make products widely available and accessible at moderate prices once approved.

Avoid international competition to access the first lots of vaccines or treatments, to ensure that any effective vaccine or treatment is first supplied to where need is the highest and where it can have most impact.

New incentive mechanism, such as global innovation funds, market entry rewards, and advance purchase commitments, may be required to finish the development process of products being developed for Covid-19 to prepare for future crises if the immediate need for these products disappears.

Dealing with the Covid-19 shock and other epidemics through resilience strategies and policies

In addition to the health care system, how should we deal with the considerable shock that Covid-19 places upon international markets, social activity, and governance? How can we address the cognitive and especially behavioural effects of fear at the individual and collective level, which can trigger substantial slowdowns in economic activity, as well as the systemic effects that strain various sectors of international trade and governance?

Two overarching philosophies and methodologies are available for stakeholders to draw upon. Until recently, the consensus would have insisted upon preventing a threat from happening in the first place or substantially mitigating its consequences after the event if absolute prevention or avoidance is impossible. As the basis of conventional risk management (i.e., to prepare for and absorb shocks), this option is politically appealing at the onset, as it offers the possibility that unacceptable risks may be bought down before they cause serious problems.8 In a world of rapid feedback loops and increasingly nested systems where cascading failures are inevitable, however, such options might be ineffective at protecting economic and social systems and calming perturbations, or would be ruinously expensive to implement to the extent needed to assure policymakers and other stakeholders of adequate protection (Michel-Kerjan, 2012; Linkov et al, 2019). Risk management is too often construed as a means of maintaining the leanest possible operations in the name of efficiency, and consequently, reducing redundancy to zero. Without redundancy, there is much greater vulnerability and little or no ability to absorb shocks, which in turn can quickly turn into failures.

The second approach is one that accepts the inherently uncertain, unpredictable, and even random nature of systemic threats and addresses them through building system resilience.9 Rather than rely solely upon the ability of system operators to prevent, avoid, withstand, and absorb any and all threats, resilience emphasises the importance of recovery and adaptation in the aftermath of disruption. Such a mind-set acknowledges that the infinite variety of future threats cannot be adequately predicted and measured, nor can their effects be fully understood. Resilience acknowledges that massive disruptions can and will happen – in future, climate disruption will likely compound other shocks like pandemics – and it is essential that core systems have the capacity for recovery and adaptation to ensure their survival, and even take advantage of new or revealed opportunities following the crises to improve the system through broader systemic changes.10 The Covid pandemic for example provides an opportunity to address other emergencies such as climate change more effectively. This is sometimes characterised as not just bouncing back, but “bouncing forward” (Linkov, Trump, and Keisler, 2018; Ganin et al, 2016; Ganin et al, 2017).

Interconnectivity between systems is one of the structuring and determining features of the modern world, which is becoming ever more complex and dynamic. This is a product of economic opportunity as well as global political interconnectedness, and has brought considerable benefits to much of the global population. An instinctive reaction to the Covid-19 outbreak would be to limit or reduce such interconnectedness, yet such sweeping policy changes would not better protect countries or international markets against future systemic threats. Instead, an emphasis upon developing resilience within the international economic system is a necessary evolution for a post-Covid-19 world, where systems are designed to facilitate recovery and adaptation in the aftermath of disruption.

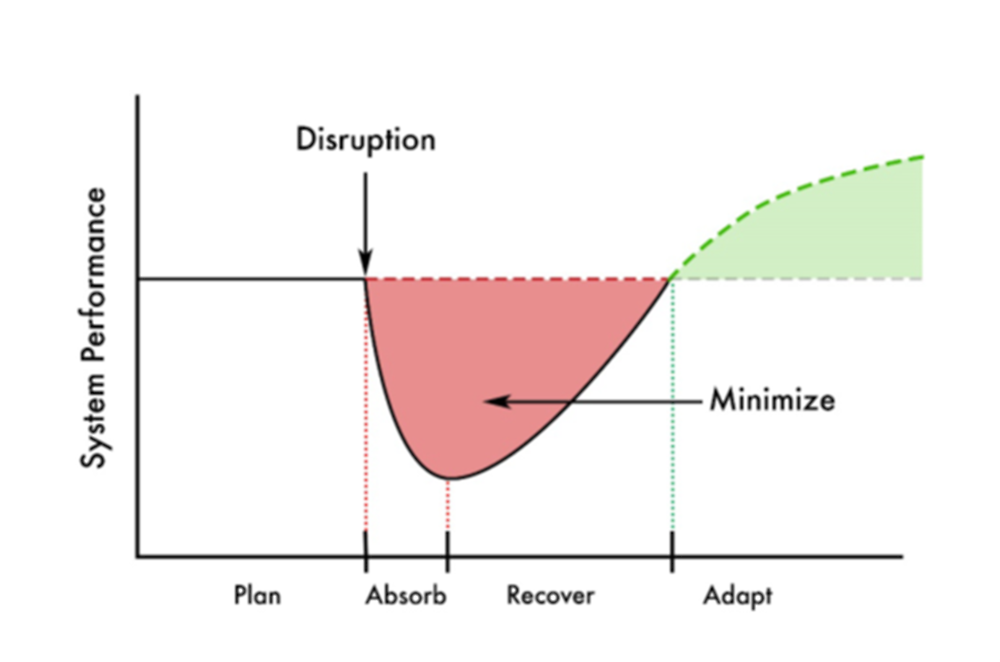

Complementing risk-based with resilience-based approaches for the management of epidemics, as well as for other systemic threats, is a necessity. Risk management of a system driven by resilience as a goal would identify those uncertainties (unpredictable risks) likely to have an effect on resilience The resilience we are talking about here, however, is not resilience in the traditional sense the OECD tended to use, meaning the capacity to resist downturns and get back to the same situation as before. There is an awareness that the systemic threats modern societies face are increasingly difficult to model, and are often too complex to be solved for the “optimal response” using traditional approaches of risk assessment that focus primarily upon system hardness and ability to absorb threats before breaking. The new approach to resilience will focus on the ability of a system to anticipate, absorb, recover from, and adapt to a wide array of systemic threats (see figure below).

The NAEC report “Resilience Strategies and Policies to Contain Systemic Threats” defines concepts related to systemic threats and reviews the analytical and governance approaches and strategies to manage these threats (including epidemics) and build resilience to contain their impacts. This aims to help policymakers build safeguards, buffers and ultimately resilience to physical, economic, social and environmental shocks.

Recommendations

Recovery and adaptation in the aftermath of disruptions is a requirement for interconnected 21st Century economic, industrial, social, and health-based systems, and resilience is an increasingly crucial part of strategies to avoid systemic collapse. Based on NAEC reports and the resilience literature, specific recommendations for building resilience to contain epidemics and other systemic threats include:

- 1.

Design systems, including infrastructure, supply chains, and economic, financial and public health systems, to be resilient, i.e. recoverable and adaptable.

- 2.

Develop methods for quantifying resilience so that trade-offs between a system’s efficiency and resilience can be made explicit and guide investments.

- 3.

Control system complexity to minimise cascading failures resulting from unexpected disruption by decoupling unnecessary connections across infrastructure and make necessary connections controllable and visible.

- 4.

Manage system topology by designing appropriate connection and communications across interconnected infrastructure.

- 5.

Add resources and redundancies in system-crucial components to ensure functionality.

- 6.

Develop real-time decision support tools integrating data and automating selection of management alternatives based on explicit policy trade-offs in real time.

Procedurally, a complement to such resilience-based approaches is included in the International Risk Governance Centre’s Guidelines for the Governance of Systemic Risks (IRGC 2018). The IRGC highlights a multi-step procedure to identify, analyse, and govern systemic risks, as well as better prepare affected systems for such risks by mitigating possible threats and transitioning the system towards one of resiliency-by-design. The IRGC’s cyclical process for the governance of systemic risk includes:

- 7.

Explore the system, define its boundaries and dynamics.

- 8.

Develop scenarios considering possible ongoing and future transitions.

- 9.

Determine goals and the level of tolerability for risk and uncertainty.

- 10.

Co-develop management strategies dealing with each scenario.

- 11.

Address unanticipated barriers and sudden critical shifts.

- 12.

Decide, test and implement strategies.

- 13.

Monitor, learn from, review and adapt.

The purpose of the IRGC exercise is not to generate a deterministic model that applies to any and all systems – this is neither possible nor helpful. Instead, it is designed to produce more introspective, collaborative, and multi-system viewpoints regarding the threats that may be lingering along the peripheries of systems, as well as where a system’s critical functions or resilience challenges should be improved within future strategic management opportunities.

An example of applying similar approaches to disease epidemics is presented in Massaro et al (2018). The methodological resilience framework discussed above was applied to the analysis of spread of infectious diseases across connected populations. They monitor the system–level response to the epidemic by introducing a definition of engineering resilience that compounds both the disruption caused by the restricted travel and social distancing, and the incidence of the disease. They confirm that intervention strategies, such as restricting travel and encouraging self-initiated social distancing, reduce the risk to individuals of contracting the disease. However, given the expected repercussions of restricted population mobility for critical functionality of the economy, consideration could be extended to address how to keep the system resilient even under necessary and life-saving measures such as lockdowns.

So although containment measures are unavoidable to slow down the epidemic’s progression, such measures may drive the system into negative health and economic outcomes. Multiple dimensions of a socio-technical system must be considered in epidemic management, based on treaties like international health regulations which govern infectious disease response internationally and set out a framework for analysing contingency plans at the national and international levels. For Covid-19, this implies that countries should resist the temptation to self-isolate from their international partners in an attempt to build national self-reliance. Viruses do not respect borders or administrative silos and the response to them has to be international and inter-sectoral. Multilateral action, as called for by G20 and G7 Leaders, will make governments’ initiatives far more effective than if countries continue to act alone. The encouraging examples of medical equipment, personnel, best practices, and even hospital capacity being shared among countries can motivate and justify an integrated, multilateral approach to helping national and international systems to recover better. One way of doing it is to protect existing ODA commitments, targeting supports to health systems and vulnerable people in developing countries. Multilateral funds are efficient and effective ways of disbursing funding fast to places where it is most needed, but the cooperation and mechanisms to encourage international coordination that emerged in tackling Covid-19 should not be allowed to fade when the crisis ends.

Governments are considering a wide variety of political and economic policies to safeguard and recover lost economic and societal functions due to the Covid-19 pandemic. OECD’s value‑added to this exercise is to identify strategic opportunities to shape intermediate and future policy in a manner that not only preserves and recovers from this crisis, but also improves national and international economic systems. Policy actions to facilitate recovery must be analysed and selected now, and any policy decisions in the short term will shape not only the nature of economic recovery in the next year, but the economic and political priorities of economic globalisation as well.11 Policy choices made for the recovery will also have a strong influence on the world’s ability to avert dangerous climate change, as well as to become more resilient to the climate impacts already locked in.

In recovering from the Covid shock, the OECD can use economic models and other analytical resources to assess the efficiency of different regulatory policies discussed in Box 2. These immediate needs are of critical importance. Equally important will be OECD inputs to develop strategic priorities and building resilience in national and regional responses to the crises. In both cases, policy interventions and priorities to address Covid-19 must incorporate principles of system resilience to systemic disruption now, for not doing so will limit future socioeconomic recovery for the next decade at least.

Systems thinking is the most powerful tool we have at our disposal to accomplish this task, if it is part of a trilogy completed by anticipation and resilience. On a theoretical level, systems thinking shows that crises are an intrinsic characteristic of complex systems such as public health or financial markets. In practical terms, policymakers must factor in the certainty that sooner or later all systems fail, including the ones they are making policy for. So they have to be prepared, even if preparation does not appear to be cost effective until the crisis happens. The excuse that dangers are clear only in hindsight does not stand up to objective scrutiny. Major simulation exercises in OECD countries predicted accurately how a crisis like Covid-19 could unfold12, but they were not acted on, or not sufficiently, judging by what has happened.

Resilience is a safe option in intangible domains such as financial systems too. Many people saw the present financial crisis coming and many experts pointed to debt as a major contributing factor to system fragility. A policy approach based on systems thinking would accept that although we do not know what the trigger of the next crisis will be, we do know it will come and that certain factors can make it more likely and more damaging, and that there are better policy options than waiting for it to happen then paying for bailouts.

Finally, a systems approach is in tune with the OECD’s repeated calls to “break down silos”. We are seeing how a health crisis does not remain simply a health crisis for long. It can quickly spread to other systems that at first sight seem to be unconnected. In a world where an ecosystem in a Chinese province can trigger a global economic crisis, we have to abandon our traditional, linear, compartmentalised way of making and applying policy, and cooperate pragmatically at local to international levels.

Strategic Need: Preserve and Recover from Disruptions to Local Economies

Policy Response: Identify interventions to improve business recovery post-Covid-19. Funding should be prioritised based on immediate needs for economic recovery at the system level that includes consideration of local demand and regional/global supply chain and impact of the region to regional, state, and global economy.

Economic Action: Prioritise and invest within critical economic sectors and businesses based upon value-added to local community (i.e., the dollar/euro yielded for taxes, salaries, local spending per dollar/euro invested into the company)

OECD Response: Assist governments (both national and local) to prioritize (a) critical economic sectors, and (b) critical industries/businesses that have a socially and economically net-positive contribution to society. Any low-interest loans or targeted investment/disbursement should be targeted, rather than prioritizing businesses or industries with social or economic net negatives/harms to broader society (i.e., high downstream costs with low immediate benefits via exploitative wages and sending money outside of the local economy). For example, renewable energy should be subsidised, industries based on extraction should not.

Strategic Need: Bolster consumer/household resilience to shock

Policy Response: Identify interventions to improve household recovery post-Covid-19. As the core of economic growth, individual households need to be provided resources/support at the system level across necessary goods, services, and social/cognitive support. Optimisation should be based on individual/community resilience to avoid the impact of shocks and optimise recovery.

Economic Action: Revisit recommended assumptions upon household budgets, and identify areas of required slack/redundancy in household spending/savings.

OECD Response: First, analyse government stimulus proposals based upon their ability to meet all or most of the critical household needs of various segments of the population disrupted by the crisis.1 Second, adopt recommendations to prevent household brittleness or fragility to shock (high cost of core essentials like housing, food, utilities, education, public health, etc.). Identify governmental investments and policy options to mitigate rising cost concerns of core industries and incentivise ‘slack’, or household savings to accommodate disruption of lost wages.

Strategic Need: Prevent Company Bankruptcies, Layoffs, and/or Shutdown While Complying With Pandemic Response Requirements.

Policy Response: Identify critical companies whose disruptions and layoffs would reduce national capacities to deliver goods and services in a non-linear fashion (i.e., lost synergy, social capital, institutional memory, etc.)

Economic Action: Targeted loans and investments into select companies and large corporations whose disruptions are not easily recoverable, and losses in institutional memory/social capital would have long-term ramifications.

OECD Response: Identify industries who historically have had difficulties in recovery post-disruption (i.e., the ‘Dot Com Bubble’, the September 11th Terrorist Attacks, the Financial Crisis/Great Recession of 2007-2009, etc. Within those industries, identify economic interventions (low/zero-interest loans or other investment) that have policy requirements of keeping sections of their labour force on payroll throughout the crisis and during recovery. Require the company to cover a portion of their payroll (i.e. 1 day each week), with government investments covering the majority of that time (i.e. 4 days each week). Labour covered by government investment should be in full compliance with WHO recommendations regarding social distancing and pandemic response requirements. This proposal will (a) prevent mass lay-offs of high-intensity corporations that require considerable institutional and technical knowledge to operate, and (b) remove the need for such workers to seek new economic opportunities for lost wages and remain in compliance with pandemic response requirements.

Ministers of Social Affairs recently mandated the OECD to develop a framework for assessing households’ risks and identify how the policy package should be adapted to better help them addressing these risks. A Strategy is also being developed to collect the required additional data.

Conclusions

A resilience mind-set acknowledges that the infinite variety of future threats cannot be adequately predicted and measured, nor can their effects be fully understood. Adopting such an approach means rethinking our priorities, and especially the role of optimisation and efficiency. The science of systems engineering teaches us that when you try to optimise one part of a complex system, you can end up destabilising the system as a whole. We see that in global supply chains, surely one of the most efficient components of the international economy. The French Minister for the Economy, Bruno Le Maire, argues that that there will be a before and after Covid-19 for the world economic system: “We need to draw all the conclusions from this epidemic on the way globalisation is organised, and notably value chains” (Le Maire, 2020). When your highly optimised workflow is disrupted by shocks such as Covid-19, maybe just-in-time needs a dose of just-in-case.

When Bill Gates in 2015 said that "We are not prepared for the next outbreak" and suggested creating an army of specialists from many disciplines to meet whatever crisis or epidemic might arise - 27 million people viewed his talk but as he said in 2020, nobody in power heard the message. We are now in the midst of a systemic upheaval foreshadowed at the NAEC Group meeting in September 2019 on Averting Systemic Collapse which pointed out that “a new crisis could emerge suddenly, from many different sources, and with potentially harmful effects”. The radical uncertainty associated with complex systems makes it impossible to predict where the next crisis will come from but that does not stop us learning the lessons of the past to prepare a systemic response for the future. One lesson from Covid-19 is that crises do not repeat themselves. The fact that we were able to contain previous coronavirus crises such as SARS led to a sense of complacency in some instances about our ability to contain any future crisis.

We cannot afford to be complacent about the other grave crisis we are facing: the climate emergency. In systemic terms, this is not a shock, with all that implies of a sudden, unexpected occurrence, but more like a stress. Systems analysis teaches us that stresses such as global warming are nonlinear. The system may continue to function more or less normally for a long period and only degrade slowly, but it can then reach a tipping point from which it cannot recover, and collapse can then be extremely rapid. Covid shows that we have to act now, because we simply don’t know how changes in one system may evolve and impact other systems, in this case how a mutation in a virus could cripple the world economy. We can anticipate however that serious damage to a natural system, such as biodiversity loss, or significant changes such as sea level rise or increased occurrence of extreme weather, will have serious impacts on economic and social systems too. And all the while we have to keep in mind that the next crisis may not have “natural” origins. It could for example be a due to a failure of telecommunication systems due to cyberattack or accident.

In the spirit of Gate’s call, the OECD has to help its Members to better anticipate, prepare and build resilience for future crises. There are four specific areas where NAEC could contribute, working with Directorates, Committees and Members: 1.) further developing systemic resilience approaches at the OECD building on existing NAEC work (Linkov et al, 2018; Linkov et al 2019), 2.) promoting the use of systems thinking and anticipation (including through the OECD-IIASA Task Force) to better understand the interactions, tipping points, feedback loops and multiple equilibrium which systems of all types are subject to, 3.) Fostering the use of new analytical tools and techniques to simulate the dynamics of crises using network and agent-based models to better understand how shocks emerge and propagate whether a pandemic, financial crisis, collapsing production networks, environmental shocks or social breakdown, 4.) Working with the Open Markets Institute to swiftly develop a set of principles and rules policymakers can use to shock-proof all vital human-made systems and engineer these systems in ways that make them more transparent, accountable, and more open to forms of innovation that will empower us to deal with other pressing crises.

References

www.oecd.org/naec/averting-systemic-collapse

www.oecd.org/naec/integrative-economics

Aubin, J.P. (2010), Une approche viabiliste du couplage des systèmes climatique et économique Natures Sciences Sociétés 2010/3 (Vol. 18), pages 277 à 286

Epstein, J. (2014), Agent_Zero: Toward Neurocognitive Foundations for Generative Social Science, Princeton University Press: Trenton

Ferguson, N. M. et al. (2020), Preprint at Spiral https://doi.org/10.25561/77482

Ganin A. A., Kitsak, M., Marchese, D., Keisler, J. M., Seager, T., & Linkov, I. (Dec. 2017), “Resilience and efficiency in transportation networks,” Science Advances, 3(12), e1701079.

Ganin, A. A., et al. (Jan. 2016). “Operational resilience: concepts, design and analysis,” Scientific Reports, 6, 19540.

Helbing, D. (2012), Systemic risks in society and economics. In Social Self-Organization, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

IRGC (2018), Guidelines for the Governance of Systemic Risks: In systems and organisations In the context of transitions. ETH Zurich

Linkov, I., Trump, B. D., & W Hynes (2019) Resilience Strategies and Policies to Contain Systemic Threats

Linkov, I., Trump, B. D., & K Poinsatte-Jones, P Love, W Hynes, G Ramos (2018) Resilience at OECD: Current State and Future Directions IEEE Engineering Management Review 46 (4), 128-135

Linkov, I. & B. D. Trump (2019), The Science and Practice of Resilience. Berlin, Germany: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-04565-4

Linkov, I., Trump, B. D., & Keisler, J. (2018), “Risk and resilience must be independently managed”, Nature, 555(7694), 30-30.

Michel-Kerjan, E. (2012), “How resilient is your country?”, Nature News, 491 (7425), 497.

U. Juttner & S. Maklan (2011). Supply chain resilience in the global € financial crisis: an empirical study. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal , 16(4), 246 –259.

E. Massaro, A. Ganin, N. Perra, I. Linkov and A. Vespignani, (2018) Resilience management during large-scale epidemic outbreaks, Nature Scientific Reports 8, 1859 (2018) Also available at: http://www.oecd.org/naec/integrative-economics/Resilience_management_during_epidemics.pdf

NEA (2016), Implementation of Defence in Depth at Nuclear Power Plants: Lessons Learnt from the Fukushima Daiichi Accident, Nuclear Regulation, OECD Publishing, Paris https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264253001-en

OECD/FAO (2019), Background Notes on Sustainable, Productive and Resilient Agro-Food Systems: Value Chains, Human Capital, and the 2030 Agenda, OECD Publishing, Paris/FAO, Rome, https://doi.org/10.1787/dca82200-en.

Le Maire (2020), Coronavirus : "Il y aura, dans l'histoire de l'économie mondiale, un avant et un après coronavirus", déclare Bruno Le Maire"

Schelling, T. (1999), “Social mechanisms and social dynamics. In Social mechanisms: An analytical approach to social theory”, edited by P. Hedström and R. Swedberg, 32-44. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Notes

The WHO inter alia has developed a strategic framework for emergency preparedness. After this epidemic crisis, no doubt the international community would have to reflect very seriously about how to bring health emergency preparedness to a new (much higher).

Another very clear and interesting contagion model, highlighting the role of social dynamics, lags and threshold effects in recurrent waves of measles in Africa (due in part to lulls in vaccination) (Schelling, 1998).

OECD Assessment (27 March 2020)

OECD’s Sovereign Borrowing Outlook also emphasises increase in public debt and persistent low interest rates as destabilising factors: http://www.oecd.org/finance/Sovereign-Borrowing-Outlook-in-OECD-Countries-2020.pdf

https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/faqs/EN/topics/civil-protection/coronavirus/coronavirus-faqs.html

This is not to discount the importance of risk management. A stronger risk approach would, for example, have led to complete development of a SARS vaccine, on the grounds that a coronavirus outbreak of some sort was likely at some point, and the costs of completion would have been trivial in comparison.

For example, the protective function of buffers, the psychological and organisational functions of slack (see Shafir & Mullainathan or the adaptive function of redundancy by design (there are many examples of this in biology and engineering).

Just as advanced economies, governments in developing countries need to take swift action, but their institutional and fiscal capacities are limited. The crisis has exposed an aspect of fiscal policy in developing countries that was previously less examined: their resilience. Timely international coordination to enable developing countries to face the crisis with the economic packages needed will be fundamental in the short to medium term. The financial pressure that economic packages will put fiscal systems should not be under-estimated. Most developing countries face high levels of informality – both workers and firms – requiring innovative channels to reach the vulnerable population in times of crisis. The OECD is naturally the place for a policy dialogue on building fiscal resilience in developing countries that would help countries preparedness for future crises.

For example, Crimson Contagion in the US or Exercise Cygnus in the UK