Abstract

As the roll out of coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccines begins, this policy brief asks how to ensure vaccines for all. In doing so, it examines the case for multilateral approaches to access and delivery, maps key challenges, and identifies priority actions for policy makers. The absence of a comprehensive approach to ensure vaccine access in developing countries threatens to prolong the pandemic, escalating inequalities and delaying the global economic recovery. While new collaborative efforts such as ACT Accelerator and its COVAX initiative are helping to bridge current gaps, these are not enough in circumstances where demand far outstrips supply. Based on the current trajectory, mass immunisation efforts for poorer countries could be delayed until 2024 or beyond, prolonging human and economic suffering for all countries. Policy actions to support equitable vaccine access in developing countries include: (i) supporting multilateral frameworks for equitable allocation of vaccines and for crisis response, resilience and prevention; (ii) highlighting the role of development finance; and, (iii) promoting context-driven solutions.

The case for a co-ordinated approach to vaccines

On 26 January 2021, on the occasion of the World Economic Forum in Davos, OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría described the challenges surrounding global access to vaccines against COVID-19 as the “greatest test for mankind as a whole and for OECD countries in particular”. He highlighted the need for joined up solutions to end the pandemic, including the important role of international development assistance to support developing countries (Gurria, 2021[1]). His statement followed new warnings from the World Health Organization (WHO) on the growing risk that “me first” approaches to securing vaccines will undermine multilateral efforts (Ghebreyesus, 2021[2]).

As the OECD Development Co-operation Report 2020 highlights, the case for a co-ordinated multilateral response to the crisis is well established, and further attention to expanding access to vaccines for developing countries and closing the financing gap is urgently needed (OECD, 2020[3]). Without such action, the pandemic is unlikely to be contained, inequalities within and between countries are set to escalate, and recovery of the global economy will be delayed, exacerbating negative spillovers from the current crisis across the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Meanwhile, a report from the International Chamber of Commerce estimated that should countries continue to pursue an uncoordinated approach to vaccine distribution, the world risked global GDP losses in 2021 alone of as much as USD 9.2 trillion, with around half of that loss expected to be borne by advanced economies (Çakmaklı et al., 2021[4]).

The COVID-19 pandemic compounds pre-existing challenges and inequalities for developing countries. The OECD Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2021 estimates that development flows from all sources may have fallen by as much as USD 700 billion in the past year (OECD, 2020[5]). This is equivalent to more than four times the value of Development Assistance Committee (DAC) official development assistance (ODA). Despite global efforts to suspend debt repayments for the poorest countries, the pandemic has given rise to new levels of unsustainable sovereign debt as exports dwindle, access to finance is constrained and public spending grows. Meanwhile, developing or emerging market economies where tourism is critical are expected to continue to see their circumstances deteriorate in 2021 and will require further international assistance (OECD, 2020[5]).

In the face of this unfolding crisis, many developing countries find themselves lacking the same response tools deployed by OECD governments (such as large monetary and fiscal stimulus packages) to raise debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratios. On current estimates, developing countries would have required an additional USD 800 billion to USD 1 trillion in emergency stimulus to respond to the crisis at a comparable magnitude of spending. Sub-Saharan Africa as a whole, would need to spend an additional 6% of its GDP to match the scale of OECD countries’ recovery relief packages (OECD, 2020[5]).

As the world’s biggest and wealthiest economies look forward to new vaccines in 2021 and 2022, the question of how to provide equitable access to vaccines globally remains unresolved. By current estimates, the bulk of the adult population in advanced economies will have been vaccinated by mid-2022. For middle-income countries, this timeline may stretch to late 2022 or early 2023, while for poorer countries, mass immunisation will stretch until 2024, if it happens at all (Duke Global Health Institute, 2020[6]; BMJ, 2020[7]; The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021[8]). Meanwhile, vaccine diplomacy is also expected to play a major role in determining which developing countries will have access to vaccines first, as countries with vaccine supply capacity compete for international influence (Kumar, 2021[9]; Shepherd and Seddon, 2021[10]; Choudhury, 2021[11]).

Collaborative efforts – such as the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator and its associated tools have emerged to help bridge current gaps in the world’s ability to respond to the crisis, including through the provision of international development assistance (OECD, 2020[3]; WHO, 2020[12]). These efforts make a powerful economic case for joined up global action on access to vaccines, focused on the links between health security and global economic recovery (WHO, 2020[13]). Within the ACT Accelerator’s vaccines pillar, COVAX (the global initiative to ensure rapid and equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines for all countries, regardless of income level) has arrangements in place to access nearly two billion doses of COVID-19 vaccine candidates, on behalf of 190 participating economies. This includes delivering at least 1.3 billion donor-funded doses of approved vaccines by the end of 2021 to the 92 low- and middle-income countries eligible for the COVAX Advance Market Commitment (COVAX AMC) (Gavi, 2020[14]). Yet these efforts remain seriously underfunded and are competing for limited vaccine supply against bilateral agreements negotiated by developed countries.

Even if enough vaccine doses are eventually made available through multilateral and other channels, success will be also constrained by challenges in the health systems of many developing countries. These challenges range from a lack of trained medical personnel and inadequate health infrastructure (including adequate vaccine storage facilities) to limited tracking mechanisms. Despite the clear evidence on the importance of a more holistic approach, as of January 2021 the ACT Accelerator’s pillar on strengthening health systems had received less funding than any other area (Usher, 2021[15]).

To ensure vaccines for all, key challenges ahead include:

Availability: High income countries have purchased a high proportion of available vaccine doses, signing purchasing agreements for quantities of vaccines sufficient to vaccinate their entire populations several times over;

Cost: While some pharmaceutical companies have set lower vaccine prices for developing countries, or have committed to sell without profit for the duration of the pandemic (Oxford University-AstraZeneca), others have not;

Barriers to local production: While several developing countries have the capacity to manufacture vaccines, intellectual property (IP) rights and limited technology transfer remain barriers to build local production capacity; and

Logistics and infrastructure challenges: Beyond access, developing countries have different challenges and capacities. As such, they must have a central role in rolling out and communicating vaccination programmes, including in determining key risk groups and prioritising those most in danger of being left behind.

Beyond learning from evaluations and increased development finance, effective responses to the pandemic will also require policy makers in advanced economies to adopt more coherent approaches on the speed and scale of vaccination efforts. This includes ensuring more effective and efficient multilateral co-operation on access in close co-ordination with developing countries’ strategies, as well as broader efforts to strengthen health systems (see the policy options below).

Overall, in the absence of a comprehensive solution to effective and efficient global immunisation efforts, poor and vulnerable countries are at risk of falling further behind in their development and integration into the global economy, and ongoing health security threats will delay a global recovery (OECD, 2020[5]).

Situate the work on development co-operation for vaccine access in the broader discussion on preparedness for – and response to – global challenges. Health security can only be achieved by ensuring coherence between domestic and international policies on vaccine access and delivery, thereby helping to address the inequality gaps within and between countries. Recovery will be faster and resilience to new crises will be stronger if vaccines are rolled out equitably to all countries, including the poorest and most vulnerable.

Back collective and co-ordinated global responses. To fulfil their objectives, multilateral initiatives such as the ACT Accelerator and its vaccines pillar will need strong support, not only to provide funding, but also to help to ensure timely vaccine supply for developing countries, including through increased transparency on bilateral contracts and through dose sharing.

Support a new global consensus to establish principles for equitable access between and within countries beyond current multilateral efforts. Research and development of vaccines, as well as production capacity, is concentrated in just a few countries in the world, thereby requiring most low- and middle-income countries to import vaccines. A global consensus on principles for equitable access can usefully build on Gavi’s work to establish principles for sharing vaccine doses between countries through COVAX (Gavi, 2020[16]). It should also translate into allocation sequences and distribution mechanisms that are legally binding and can be enforced. Where possible, the transfer of technical know-how to manufacturers in developing countries should be encouraged.

Ensure that key decision makers in global fora (e.g. UN, G20, and G7) have the evidence they need for joined up leader-level commitments on crisis response and improved resilience for the future. This includes:

Providing latest costings for additional development finance required for the ACT Accelerator;

Ensuring that flows to collaborative initiatives and vertical health funds reinforce and complement capacity and infrastructure for healthcare delivery at the national level;

Encouraging efforts to minimise IP barriers to the production of COVID-19 vaccines, including through recording pledges of commitment made under the Solidarity Call to Action to voluntarily share COVID-19 health technology-related knowledge, intellectual property and data through the WHO COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP) and/or mechanisms for licensing of intellectual property as provided by the Doha Declaration on TRIPS Agreement and Public Health and the TRIPS flexibilities (see footnote 6);

Supporting initiatives to co-pilot innovative solutions such as Advance Market Commitments and Product Development Partnerships.

Recognise the role of ODA as an important source of finance for health systems strengthening and vaccines in the poorest countries, while reiterating that this source of financing will fall far short of the additional investments required. The contribution of surplus vaccines from development provider countries is considered ODA-eligible if fit for the specific context of developing countries. Such contributions should be considered as additional so as not to crowd out other development assistance flows or undermine the objectives of multilateral mechanisms (e.g. ACT Accelerator). Effective delivery of vaccines will rely on strong health systems; yet access to vaccines and better health systems for developing countries in the future go well beyond the capacity and resources of international aid programmes. More domestic investment in national systems (e.g. training workers, ensuring logistics) is needed. At the same time, many sectors such as education, also lack development resources and are necessary to help build strong, resilient societies and address social determinants of health.1

Provide context-driven solutions to vaccination roll-out in developing countries. This goes beyond research and development, manufacturing and procurement to produce more doses. Vaccination campaigns need to be well-planned and executed, requiring a functioning health system with sufficient infrastructure, population outreach and human resources, as well as appropriate information systems to schedule and track vaccinations. To sustain these efforts, developing countries should have a central role in determining strategies for vaccination roll-out, including in targeting vulnerable groups and communications. In an effort to help fill this gap, the recently announced “hundred-hundred initiative” of WHO, UNICEF and the World Bank aims to support 100 countries to conduct rapid readiness assessments and develop country-specific plans within 100 days for vaccines and other COVID-19 tools (Ghebreyesus, 2020[17]).

Addressing the unique challenges inherent in vaccine access for populations in the most fragile contexts. In addition to broader inequities, fragility increases inequity in immunisation coverage by reducing the ability to undertake vaccination campaigns or restricting access for certain population groups (including women and ethnic minorities). Development co‑operation providers can help with preparedness, and addressing fragility overall, strengthening health and development outcomes for vulnerable populations directly and limiting broader negative spillovers globally.

Strengthen support to and co-operation with civil society, in particular, local civil society organisations (CSOs), to enable them to contribute to equitable access to COVID‑19 vaccines in the following areas:

Advocacy to draw attention to the benefits of equitable access, break down social and cultural barriers to vaccination and increase trust in vaccination programmes;

Oversight of vaccine roll-out to ensure accountability on key issues such as policies, budget and spending to make COVID-19 vaccines available to and affordable for all; and

Provision of knowledge, technical expertise, and outreach at the grassroots level to inform vaccine coverage policies and support vaccine delivery particularly in fragile, conflict-affected or remote settings, to help ensure no one is left behind.

Ensuring adequate planning for the range of potential scenarios for development co‑operation in the future, including through greater use of foresight analysis. While ensuring access to vaccines in developing countries is key for global health security, adequate consideration and financing must also be given to treatment access and improvement of testing and tracing protocols, as well as boosting intensive care capacity. At the same time, efforts to respond to COVID-19 and reinforce preparedness for new health crises should not take away from ODA finance for other sectors, where progress towards many of the SDGs has been set back 10-20 years.

Additional measures are necessary to prepare countries transitioning towards higher income levels for the eventual loss of access to preferential pricing and donor support for vaccine financing. Since 2014, more than a dozen countries have seen their funding from Gavi end and more than 10 countries have had financial support from the Global Fund cease. At the same time, revised forecasts for many middle income countries – particularly small island developing states and countries reliant on tourism or remittances – have been faced with severe economic impacts which will require adequate international support.to access vaccines, as well as broader concessional finance and reconstruction packages.

Challenges for vaccine access and delivery in developing countries

Providing timely and equitable access to vaccines against COVID-19 for all people in developing countries presents enormous challenges, especially when taking into account competing health priorities and broader commitments in line with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. At the same time, it is clear that failure to meet these challenges will jeopardise global recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and limit the integration of developing countries into the global economy. There is also evidence that delays in vaccine roll-out will deepen inequalities both within and between countries, with estimates that an additional 150 million people have already been forced into extreme poverty due to COVID-19 (World Bank, 2020[18]). In this context, key challenges faced by developing countries include overcoming barriers to availability, cost, local production, and logistics and infrastructure. In addressing these challenges, much can be learned from past approaches in dealing with health crises, while also taking on board emerging evidence from initial responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Availability of vaccines

Despite the many positive steps towards international co-ordination and collaboration in response to the crisis throughout 2020 and 2021, demand for vaccines is expected to far outstrip supply, at least throughout the early months of 2021. Of the 12.5 billion doses that the principal vaccine producers have so far pledged to deliver in 2021, an estimated 6.4 billion have been pre-ordered, most of them by wealthy countries (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021[8]). Some advanced economies have faced claims of harmful practices such as “vaccine hoarding,” hedging their bets on potential candidates and reserving vaccine volumes sometimes several times greater than their populations (NYT, 2020[19]). At the same time, at least one advanced economy is reported to have paid far more than other countries to secure doses of the Pfizer vaccine (Rabinovitch, Lubell and Scheer, 2021[20]). In the wake of these developments, civil society has raised concerns1 around the impact of “vaccine nationalism” – where countries prioritise their own citizens and insist on priority access to vaccines through bilateral deals (Oxfam, 2020[21]). Meanwhile, WHO has called on countries with bilateral contracts – and control of supply – to be transparent on these contracts, including on volumes, pricing and delivery dates. This includes calling on these same countries to give greater priority to COVAX’s place in the queue, and to share their own doses with COVAX, especially once they have vaccinated their own health workers and older populations, so that other countries can do the same. At the same time, WHO has called on vaccine producers to provide full data for regulatory review in real time to accelerate approvals and to allow countries with bilateral contracts to share doses with COVAX, while also prioritising filling COVAX orders rather than signing new bilateral deals (Ghebreyesus, 2021[2]).

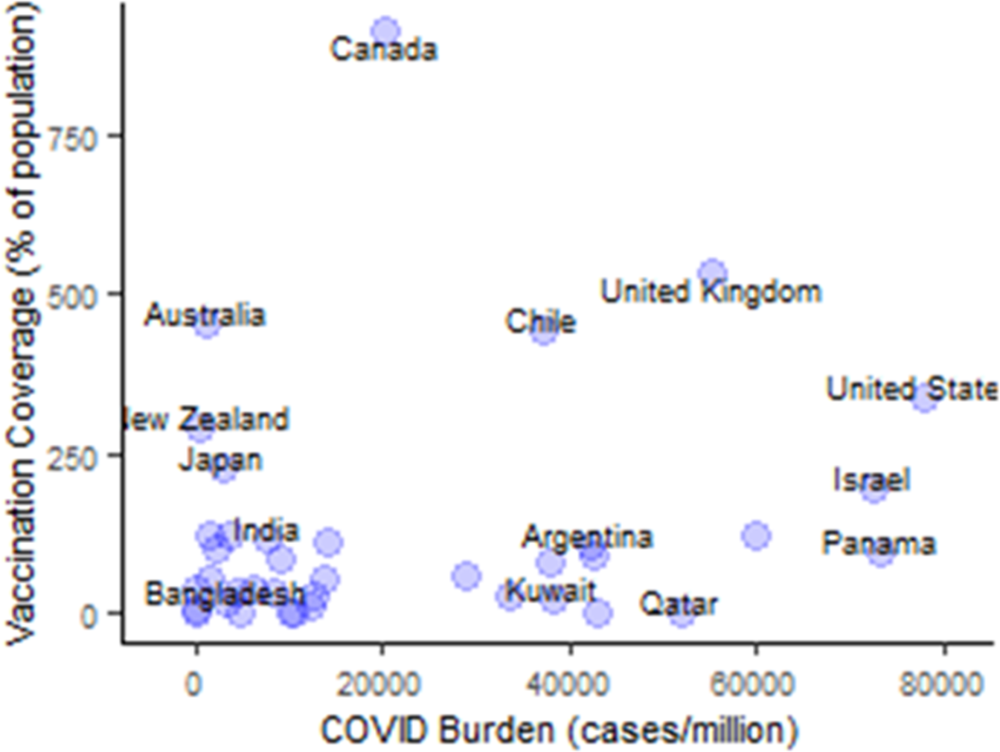

Data aggregated by Duke University (2021[22]), as well as a new initiative by UNICEF (n.d.[23]), highlight the disparities in vaccine doses secured by advanced, middle-income and low-income countries, as shown below in Figure 1.2 However, it should be noted that estimations on vaccine availability may change quickly throughout 2021 as additional vaccines come on to the market. At the same time, the People’s Republic of China (“China”), India and the Russian Federation (“Russia”) are stepping up new “vaccine diplomacy” engagement with developing countries (Kumar, 2021[9]; Choudhury, 2021[11]; Shepherd and Seddon, 2021[10]).

Note: Authors’ illustration based on Duke University (2021[22]) Launch and Scale Speedometer at: https://launchandscalefaster.org/COVID-19 (last accessed 28 February 2020) and has not yet been compared with recently released UNICEF data on this topic for comparison.

2. Overcoming cost barriers

Multilateral, regional and bilateral efforts to increase access to vaccines and treatments in developing countries are increasing. Nevertheless, the cost of vaccines remains prohibitive for many developing countries. The Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator is the most prominent example of a collaborative co‑ordination effort bringing together state and non-state actors to develop and deliver vaccines, diagnostics, and therapeutics (Figure 2). Yet even this high profile initiative lacks financing at a critical time, with an additional USD 23.9 billion required in 2021 if tools are to be deployed across the world as they become available (WHO, 2020[24]). A decision by the World Bank’s Board of Executive Directors in October 2020 to provide USD 12 billion for developing countries to finance the purchase and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, tests, and treatments for their citizens may go some way towards meeting the financing shortfall facing developing countries (World Bank, 2020[25]). But further efforts are urgently needed to close the remaining funding gap for the ACT initiative and to ensure further support for strengthening national health systems in developing countries.

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on the following sources: Requested amount taken form initial ACT Accelerator investment case publishing in September 2020 (WHO, 2020[26]) at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/an-economic-investment-case-financing-requirements; Total funding gap and funding gaps for each pillar provided by WHO directly to OECD; and funding gap breakdown for vaccine pillar taken from WHO (2021[27]) funding tracker at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/access-to-covid-19-tools-tracker and analysis in Health Systems Neglected by COVID-19 Donors in the Lancet on 9 January 2021 (Usher, 2021[15]) at: https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736%2821%2900029-5.pdf.

* Funding estimates for the ACT Accelerator are evolving quickly. In particular, an additional amount (currently estimated at USD 9.7 billion) has not yet been added to the ACT Accelerator request and is based on internal cost estimates by the Global Fund, World Bank and WHO for strengthening health systems in LICs and LMICs to cope with the pandemic.

** Funding gap as at 1 February 2021 pending the finalisation of a USD 4 billion commitment to the vaccines pillar from the government of the United States of America.

The ACT Accelerator is organised into four work pillars: diagnostics, treatment, vaccines and health systems strengthening (the Connector). Each pillar is vital to the overall effort and involves innovation and collaboration. In addition to the Connector, cutting across all of the work, and fundamental to the goals of the ACT Accelerator, is the Access and Allocation workstream that is led by WHO and is developing the principles, framework and mechanisms needed to ensure the fair and equitable allocation of these tools (WHO, 2020[12]). The economic investment case for this mechanism, launched by WHO and partners in April 2020 (WHO, 2020[26]), notes that required funding commitments would considerably shorten the duration of the crisis while costing less than 1 % of combined G20 government domestic stimulus packages (WHO, 2020[13]).

Within the ACT vaccines pillar, a total of USD 16 billion is required for 2020-21, with an outstanding funding gap of USD 7.8 billion to address.3

R&D for funding of vaccines through the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI). Of the requested funding of USD 2.4 billion in 2020-21, a gap of 1.3 billion remains.

Joint procurement of vaccines through Gavi COVAX, which includes indirect financing of R&D costs and building of manufacturing capacity through joint purchase commitments on behalf of participating countries for vaccines under development. This mechanism has two tiers: one for self-funding countries, and a second for a donor-funded Advance Market Commitment to support procurement for 92 low- and middle-income countries and ensure equal access at same time as wealthier countries. For the COVAX AMC, an additional USD 5 billion is required for 2021.

Delivery preparedness: For country readiness and delivery, including guidance, tools, co‑ordination, technical expertise and support, an estimated USD 492 million was required in 2020, with an additional USD 1 billion needed for roll out in 2021.

Furthermore, the cross-cutting Health Systems Connector pillar aims to strengthen, on a country-by-country basis, human resources, infrastructure, and data management. This pillar is still under development but work is expected to go beyond vaccination to include prerequisites for vaccination campaigns such as cold chains (WHO, 2020[28]). While the challenges are huge in some countries, the funding requirements of USD 9 billion for the Connector represent a small portion of the estimated USD 38 billion required for the ACT Accelerator to the end of 2021.4 In addition, despite the central importance of health system capacity to deliver vaccines, the Connector remains one of the most underfunded elements in the entire mechanism, with a funding gap of USD 7.9 billion. As Figure 2 indicates, further funding of USD 9.7 billion may also be required to help low- and middle‑income countries to cope with the pandemic throughout 2021 through further efforts to strengthen their health systems.5 In 2021, the OECD will undertake further analysis on access and delivery of vaccines against COVID-19, including the implications for fragile states.

In addition to global initiatives, a number of regional initiatives have emerged, such as the COVID-19 African Vaccine Acquisition Task Team (AVATT) to support the roll out of the African Union’s Africa Vaccine Strategy (African Union, 2020[29]) and the Asia-Pacific Vaccine Access Facility (Asian Development Bank, 2020[30]). At the bilateral level, vaccine manufacturers in China and Russia are making agreements with low- and middle-income countries to supply COVID-19 vaccines (So and Woo, 2020[31]). Meanwhile, Australia and New Zealand have committed to purchase vaccines for their Pacific island neighbours (Ministry of Health, New Zealand[32]). A number of other advanced economies (including Australia and Canada) have committed to share unused or excess doses from their national stock with developing countries, although how this arrangement would work, or when it could be put in place, remains unclear. To help guide these initiatives and other emerging access deals, Gavi has released Principles for Dose Sharing in December 2020 (Gavi, 2020[16]; 2020[33]).

3. Barriers to local production

Intellectual property rights (IPRs) are regularly cited as a constraint to scaling up access to vaccines in developing countries. At the same time, the sharing of technical knowledge, expertise and know-how is increasingly seen as critical for a joined up response to the current crisis. Global health security has long been recognised as a global public good, whereas vaccines are private goods that are “excludable and rival”. Despite the strong arguments in favour of sharing IP widely or at no or low cost, G20 leaders in 2020 called for voluntary licensing of intellectual property6 (OECD, 2020[3]; G20, 2020[34]). Alternatively, the Chair of the WHO Solidarity Trial of COVID-19 treatments, among others, has argued for a “partnership model”, where individual companies would be encouraged to grant non-exclusive licences and technology transfer of their products, along the lines of the agreements that AstraZeneca and Novavax have established with the Serum Institute of India for vaccines (Usher, 2020[35]). Many high-income countries have so far opposed more ambitious proposals for making IP widely available (Usher, 2020[35]).

Beyond rights to vaccine production, analysis of the trade-related impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on developing economies highlights a broad range of negative effects, from severe disruptions to supply chains and falls in GDP, to restrictions on the movement of people, goods and services (OECD, 2020[36]). Ongoing fragility could continue to have impacts on vaccine supply chains for developing countries. Available trade data on COVID-19 goods (such as medical devices and instruments, and protective equipment) reveals only a few, mostly OECD, countries are the main exporters and importers of certain goods required to fight COVID-19. Globally, over 86% of global exports are from just 20 countries.7 Smaller and developing countries are therefore heavily dependent on these suppliers, even if they have also proven their own ability to adapt when required, for example through rapid retooling to produce personal protective equipment and medical supplies. This underlines the importance of avoiding export restrictions, removing tariffs on essential goods and enabling wider trade facilitation (OECD, 2020[36]).

4. Logistics and infrastructure challenges

Even if there were enough vaccine doses available for the world’s entire population, roll out in developing countries presents a range of challenges in terms of human capacity and infrastructure. At least one-half of the world’s population does not have full coverage of essential health services, with public health systems that are often fragile and undersized in relation to challenges faced (WHO & World Bank, 2017[37]). Many developing countries struggle to provide sufficient and affordable supplies of quality medicines and are lagging behind in introducing recommended vaccines for a number of existing diseases (e.g. rotavirus and pneumococcal-conjugated vaccine). Low-income countries also have fewer health workers per capita than in other countries, with Africa, Southeast Asia, the eastern Mediterranean and parts of Latin America expected to bear the brunt of the shortfall of 5.9 million nurses and 18 million health care workers globally by 2030. Furthermore, the vaccine candidates currently likely to be available via the COVAX AMC require refrigerated storage and in most cases multiple doses – a key constraint for many countries, particularly where electrification levels are low. (For a discussion on how the ACT Accelerator is working to increase capacity for these challenges in the context of vaccine roll out, see the discussion on the cross-cutting Health Systems Connector pillar above).

Rather than accelerating progress in strengthening national health systems, the COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced existing challenges. For example, over the past year, many existing national immunisation programmes8 against diseases such as diphtheria, measles and polio, have been substantially disrupted in at least 68 countries, affecting up to 80 million children under 12 months of age9 (UNICEF & WHO, 2020[38]). These findings are in line with analyses of several Ebola crises, primarily in western and central Africa, which have shown that large-scale health crises severely limit access to health services at a time when such services are needed the most and their capacity expanded, potentially inflicting serious long term effects (OECD, 2020[39]). Ultimately, strengthening heath security at the global level will require health services in developing countries to be better integrated into national health delivery systems, limiting disruptions through vaccination programme closures and enabling all population segments (including those most at risk from COVID-19) to be reached.

The presence of a quality health system and social protection policies and programmes are two key factors that help determine a country’s ability to prevent, withstand, recover and adapt to impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, including through effective immunisation campaigns. Despite developing countries having younger populations who may suffer less from the worst health effects of COVID-19, other factors make developing countries more vulnerable to the pandemic’s effects. These may include poor socio-economic conditions, high population density, high rates of informal labour and heavy reliance on the services and manufacturing sectors for employment and foreign exchange (OECD, 2020[40]).

The importance of evaluating vaccine initiatives

A wealth of evidence is available to guide development co-operation providers in achieving equitable access: including ways of effectively supporting sustainable long-term health systems strengthening, supporting uptake of vaccines, and innovative financing mechanisms. Analysis of past experiences – notably with pneumococcal vaccines (BCG, 2015[41]), swine flu and Ebola – can assist decision makers in advancing the understanding of common barriers to equitable vaccine access. With participation from the evaluation departments of the Asian Development Bank, the Global Affairs Canada, the Norwegian Agency for Development Co-operation (Norad), the United Kingdom, the Global Vaccine Initiative (GAVI) and WHO, the COVID-19 Global Evaluation Coalition is currently compiling key evidence and lessons to help decision makers and operational staff. A first brief provides evidence-based recommendations for issues to consider when communicating with the public about vaccines (Glenton and Lewin, 2020[42]). A second brief looks at the effectiveness and impacts of using digital communications tools to promote vaccine uptake (Lewin and Glenton, 2020[43]).

Plans to evaluate the use of ODA to support equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines for low- and middle-income countries are currently being developed by the participants of the COVID-19 Global Evaluation Coalition. This collaborative evaluation work, supported by the OECD, will complement accountability and governance mechanisms in place among the key international organisations, including Gavi and the WHO.10 Criteria to be considered, based on the OECD-DAC evaluation criteria, are outlined in Box 1.

Even if the considerable financing challenges on COVID-19 vaccines for developing countries are overcome, past experiences highlight the need for development co-operation providers to work together in ways that will achieve desired impacts and avoid unintended harm. In other words, it is not enough to throw money at these problems; success in responding to the pandemic and achieving sustainable development goals means providing support that is relevant and effective and is delivered efficiently and coherently to achieve positive impacts that last. The OECD-DAC evaluation criteria can be applied to and inform the design of vaccination initiatives and subsequent evaluations to understand delivery and outcomes. The criteria encourage decision makers to ask critical question about the set-up and outcomes of interventions (whether national or international) to support equitable access, such as:

Relevance: Understanding if and how vaccine access and related health care support are addressing priority health needs, particularly those of the furthest behind; relevance of plans to the needs and wider health plans of national governments and global priorities (such as eradicating the disease).

Coherence: The extent to which countries’ other policies and actions – including national policies to address COVID-19 within their own populations – are coherent with plans for equitable access to vaccines.

Effectiveness: Understanding whether and how plans and activities to increase access to vaccines are reducing inequalities and speeding up vaccination coverage to reduce morbidity and mortality. The extent to which vaccines are reaching vulnerable or priority groups to deliver appropriate coverage within countries.

Efficiency: Considering the extent to which allocation of resources for vaccines has been an effective use of resources to achieve the outcomes at a local, national and global level, compared to feasible alternative uses of resources. Within this context it is important to consider the extent to which efficient decisions were made about expenditure based on the long-term global trajectory of the pandemic.

Impact: Understanding the impact and specific contribution of different equitable vaccines uptake initiatives on saving lives, reducing morbidity and limiting wider negative social, economic and environmental impacts. It is valuable to assess opportunities for positive impact on building back in ways that are sustainable and more equitable.

Sustainability: Considering the extent to which support for health systems, the economy and social systems will/has increased resilience and will be maintained over time, including impacts on capacities to respond to future pandemics and global health crises.

Development finance: current status

Development finance for health is increasing. Between 2000 and 2019 (latest data), ODA targeting health for developing co-operation increased from USD 3 billion to USD 27 billion (Figure 3). This growth was accompanied by a rapid rise in the number of active development partners working in the health sector, with the number of entities reporting health-related disbursements to the OECD’s Creditor Reporting System (CRS) expanding from 27 in 2000 to 86 in 2018, although part of this increase was also due to an increased level of reporting from foundations, multilateral organisations and other providers. In terms of contributions channelled, a small number of development partners dominate the landscape. Among the key players are DAC members such as the United States and the United Kingdom, but also private philanthropic foundations – notably the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) – as well as a number of global programmes designed to target specific health issues and diseases. Overall, development assistance to health represented 12% of total health spending in lower middle-income countries, and 29% for low-income countries in 2019 (latest data). Data on allocations for 2020 are not yet available, although initial evidence indicates that an increase in spending for this sector can be expected.

Source: OECD Creditor Reporting System (OECD[44]) at: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=crs1#, disbursements to health, USD billion constant 2018 (bars) and share of total (line).

This rise in health-related support has largely been driven by increasing contributions to vertical health funds and specific diseases. Between 2016 and 2018, DAC members contributed an annual average of USD 129.5 million in health development finance to vertical funds – in particular to Gavi, the Vaccines Alliance, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (Global Fund) and UNAIDS. On average, since 1996, ODA commitments to health systems (regardless of aid modality) have constituted 14% of total ODA commitments to health for DAC members. In recent years, international focus and funding commitments shifted to infectious diseases, such as Ebola, whereas funding for health systems declined to 11% over the period 2013-18 (OECD, 2020[40]). Given the need to improve the functioning of health systems in many developing countries, development co-operation providers (including vertical funds) are increasingly making efforts to ensure that even disease-specific interventions and programmes raise capacity of health systems (Kim, Kessler and Poensgen, forthcoming[45]). In this vein, efforts are needed to organise the roll-out of immunisation campaigns in a way that maximises spill-over effects on health systems overall.

A stronger focus on strengthening national systems in procurement and public financial management can enable more effective COVID-19 vaccine delivery while using and supporting these systems to provide the multi-sectoral response necessary to combat the crisis (e.g. training workers, ensuring logistics, attention to social determinants of health) (OECD, 2020[40]). For this reason, the DAC 2020 High Level Meeting statement prioritises both investment in health systems and social safety nets, which are central to every country’s strategy to combat the medical, social and economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis (OECD DAC, 2020[46]).

The 2014-15 Ebola epidemic sparked a new political level interest in health crisis response and preparedness, bringing these issues to the G20 Leaders’ Summit for the first time in 2014. In 2016, the World Bank established the Pandemic Emergency Finance Facility and the World Health Organisation published its Blueprint list of diseases and pathogens to be prioritised for research and development in public health emergency contexts. Later that year leaders agreed at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland to explore new ways to drive product innovation for high-priority epidemic threats, leading to the establishment of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), which finances research projects to develop vaccines against emerging infectious diseases.

Despite the significant scale up in funding and collaboration on health financing at the time of the Ebola crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the overall vulnerability of existing preparedness and response mechanisms and the need for a broader global response to health crises. To this end, G20 Leaders offered full support to the ACT Accelerator initiative in their declaration of 22 November 2020 (G20, 2020[34]), including for the role of “extensive immunisation” and committed to addressing remaining global financing needs, albeit without an agreed timeline.

Beyond the financing challenges outlined above, the ACT Accelerator’s vaccines pillar aims to promote equitable access and fair allocation globally, with an initial focus on high risk and vulnerable people in all countries. Principles for vaccine distribution within countries have been proposed (e.g. prioritisation of health workforce and older people) and will need fine-tuning based on individual country contexts. However, it is important to note that, while being a step in the direction of more equitable vaccine allocation, COVAX falls short of being a mechanism to distribute vaccines equitably among people on a global scale. Self-funding countries will receive volumes sufficient for between 10-50% of their populations in proportion to their financial contributions, while the 92 low- and middle-income countries are promised volume for up to 20% of their populations, subject to funding availability (Gavi, n.d.[47]).

Discussions are ongoing within the OECD DAC over the issue of ODA eligibility of contributions towards pandemic preparedness and response. In particular whether contributions directly benefit developing countries as development co-operation. For example, the OECD Secretariat has advised that research for vaccines/tests/treatments for COVID-19 cannot be seen today as complying with the ODA criterion of having the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective (OECD, 2020[48]). For this reason, a case-by-case approach is needed to identify the ODA-eligibility of such activities.11 Contributions to the Gavi COVAX AMC are fully ODA-eligible as they are used to support procurement and delivery of vaccines for ODA eligible countries. Nevertheless, at the time of writing, the ODA-eligibility of some activities related to ACT Accelerator tools (i.e. the ODA share of CEPI’s COVID-19 activities, funded by earmarked contributions to CEPI) are still under discussion. Another emerging issue is whether excess vaccines from pre‑purchased bilateral deals can be donated to developing countries as aid “in kind”. While ODA eligibility will largely depend on whether the surplus vaccines are fit for the specific context of developing countries, it will also be important to ensure that any ODA provided in this form is additional and does not lead to crowding out of other development assistance flows, particularly for countries that have a fixed ODA/GNI target. The extent to which bilateral deals can be considered to have undermined the objectives of multilateral mechanisms like the ACT Accelerator for equitable access to vaccines remains an issue of contention.

According to an article published in the Lancet on 9 January 2021 (Usher, 2021[15]), of the total USD 5.8 billion contributed by donors to the ACT-Accelerator, some USD 3.9 billion had gone to vaccine procurement and distribution in low-income and middle-income countries, while just 6% has been reserved for strengthening health care systems. Canada, European Union, Gates Foundation, Germany, Norway, Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom are the leading providers of development finance for the ACT Accelerator. However, to date, only Germany has provided funding support for health systems strengthening within this initiative, prompting calls for a re-balancing of political attention towards stronger health systems rather than vaccine doses alone (Usher, 2021[15]).

In parallel to the ACT Accelerator, other solutions, such as vaccine and product development partnerships, have emerged to develop vaccines, drugs and diagnostics for neglected and poverty-related diseases and make them available at affordable costs. For example, Gavi’s International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm) is a model that might be adapted to the case of COVID-19: i.e. Gavi would issue a bond backed by donors, which allows the organisation to obtain immediate funding to develop logistics chains in the hardest-hit countries, purchase and distribute a vaccine or a cure. Donor countries thus spread the cost over a longer period of about 20 years (Gavi[49]).

In order to strengthen resilience and improve preparedness for future shocks like COVID-19, any of the solutions envisaged will require new levels of international co-ordination, as well as new sources of financing and financial instruments. A recent WHO and OECD analysis identified an overall financing gap of USD 95 billion over five years in middle-income and low-income economies for common public goods functions contributing to pandemic preparedness (OECD, 2020[39]). While much of this financing is expected to come from increased domestic resource mobilisation, especially in middle-income countries, WHO has estimated that it would also require an almost 50% increase in ODA for developing countries’ health sectors to help meet this shortfall, particularly for the poorest countries (amounting to an additional USD 12 billion annually on top of the USD 26 billion currently allocated). Writing in the OECD Development Co-operation Report 2020, Professor Inge Kaul suggests that rather than stretching ODA budgets further to fund global public goods like health security, an overhaul of development co-operation finance is needed to give these public goods their own budget line and enable more transparent provision of financing (OECD, 2020[3]). This call is highlighted as part of a broader discussion on the way forward in the Development Co-operation Report 2020, pointing to the need to clarify the role and contribution of public finance to global public goods and to study innovative structures like the ACT-A as a model for tackling other global issues.

Finally, it will be critical to ensure financing is not diverted to COVID-19 related areas at the expense of other areas of the health system, or other sectors, and that any additional financing should be equitably distributed across all areas of the Sustainable Development Goals. This is especially important given that the pandemic is estimated to have set back progress towards many of the goals by up to two decades.12 Overall, the additional billions in development finance to address the COVID-19 crisis must be considered in the broader context of the estimated USD 7 trillion cost to the global economy through lost GDP growth by the end of 2021 due to COVID-19 (OECD, 2020[5]). Moreover, as new research shows (WHO, 2020[50]), if the financing shortfall for low- and middle-income countries to access vaccines, treatments and diagnostics is not met, this will result in a protracted pandemic and severe economic consequences – not just for poorer countries but also for the wider global economy.13

Preparing for the future: potential scenarios for vaccine access and roll-out

In planning for the future, development co-operation specialists and other policy makers will need to consider various plausible scenarios14 on vaccine roll-out and access based on science and reflecting emerging social, economic and geopolitical signals. Key questions to consider will include:

Vaccine effectiveness and evolving research: how many times will we need to redevelop or modify the vaccines, and at what cost? While vaccine immunologic targets remained relatively stable during 2020, several variants were identified in December 2020. There are concerns that such mutations may impact the efficacy of existing vaccines.15 Research has already been driven by the need to overcome certain logistical or infrastructural issues for vaccine roll-out – for example, to reduce required vaccine storage temperatures in countries where cold chains are less reliable. Future research may also evolve to take into account inter-generational or ethnic differences in immune responses to different vaccines (e.g. a vaccine has not yet been approved for use on children). In addition, prioritisation of research into vaccines for adult populations may have ramifications for developing countries where children and youth make up around half of the overall population.

Longevity of immunity: will maintaining herd immunity against COVID-19 require recurrent vaccine administration? The duration of immunity conferred by the various vaccines remains unclear. Initially, it was thought that the immune response in infected individuals was dependent on the severity of the disease and might not be durable. More recent analysis indicates immunity post-infection might in fact last for several years (like MERS or SARS), if not for a lifetime. However, this will depend on the evolution of the virus and further mutations.

Social acceptability and trust in vaccinations: Demand and uptake depend on transparency, trust, and understanding the benefits of vaccines. Meaningful community engagement, particularly with marginalised groups, those with low levels of trust in government services and/or disproportionately impacted by the pandemic are crucial to successful and equitable uptake of vaccines.

Towards a global solution or not?: Even if the world agrees on an equitable way to distribute vaccines, they may take years to reach many developing countries and excluded populations and we do not know how many people will agree to be vaccinated. Harvard Professor Kenneth Rogoff is amongst those encouraging policy makers to consider the increasingly likely possibility that the coronavirus could prove more stubborn than expected (Rogoff, 2020[51]), or that first-generation vaccines might only be effective for a short period.

Policy makers need to examine all plausible scenarios available and, while awaiting safe vaccines, significant advances can be made to improve testing, tracing protocols, and treatment in developing countries to assist in adaptation to less optimistic scenarios. At the same time, investments in data management, policy research and evaluation can inform strategic decision making on national and global responses to the pandemic – for example, on how to maximise efficient use of funds and improve the relevance of planning.

References

[29] African Union (2020), “Statement on AU vaccines financing strategy”, https://www.africa-newsroom.com/press/au-statement-on-au-vaccines-financing-strategy (accessed on 7 January 2021).

[30] Asian Development Bank (2020), “ADB’s support to enhance COVID-19 vaccine access”, in Policy Paper, Asian Development Bank, Manila, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/662801/adb-support-covid-19-vaccine-access.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2021).

[41] BCG (2015), The Advance Market Commitment Pilot for Pneumococcal Vaccines, Gavi, The Vaccines Alliance, https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/document/pneumococcal-amc-outcomes-and-impact-evaluationpdf.pdf.

[7] BMJ (2020), Covid-19: Many poor countries will see almost no vaccine next year, aid groups warn, BMJ, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4809.

[4] Çakmaklı, C. et al. (2021), “No economy can recover fully from the COVID-19 pandemic until we have secured equitable global access to effective vaccines”, in Key findings and implications of the new study: The economic case for global vaccination: An epidemiological model with international production networks, International Chamber of Commerce, Paris, https://iccwbo.org/content/uploads/sites/3/2021/01/icc-summary-for-policymakers-the-economic-case-for-global-vaccination.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2021).

[52] Chadwick, L. and L. Monella (2020), “Which parts of Europe are likely to be most hesitant about a COVID-19 vaccine?”, Euronews, https://www.euronews.com/2020/12/09/which-parts-of-europe-are-likely-to-be-most-hesitant-about-a-covid-19-vaccine (accessed on 7 January 2021).

[11] Choudhury, S. (2021), How Covid-19 vaccines can shape China and India’s global influence, CNBC, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/01/29/how-covid-19-vaccines-can-shape-china-and-indias-global-influence.html (accessed on 1 February 2021).

[6] Duke Global Health Institute (2020), Research News: Will Low-Income Countries Be Left Behind When COVID-19 Vaccines Arrive?, Duke University, https://globalhealth.duke.edu/news/will-low-income-countries-be-left-behind-when-covid-19-vaccines-arrive.

[22] Duke University (2021), Duke University Launch & Scale Spedometer, https://launchandscalefaster.org/COVID-19.

[34] G20 (2020), Leaders’ Declaration, G20 Riyadh Summit, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/46883/g20-riyadh-summit-leaders-declaration_en.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2020).

[14] Gavi (2020), “92 low- and middle-income economies eligible to get access to COVID-19 vaccines through Gavi COVAX AMC”, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/92-low-middle-income-economies-eligible-access-covid-19-vaccines-gavi-covax-amc (accessed on 7 January 2021).

[33] Gavi (2020), “COVAX announces additional deals to access promising COVID-19 vaccine candidates; plans global rollout starting Q1 2021”, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/covax-announces-additional-deals-access-promising-covid-19-vaccine-candidates-plans (accessed on 7 January 2021).

[16] Gavi (2020), “Principles for sharing COVID-19 vaccine doses with COVAX”, Gavi, https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/covid/covax/COVAX_Principles-COVID-19-Vaccine-Doses-COVAX.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2021).

[47] Gavi (n.d.), COVAX Facility (webpage), https://www.gavi.org/covax-facility (accessed on 7 January 2021).

[49] Gavi (n.d.), International Finance Facility for Immunisation (webpage), Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, https://www.gavi.org/investing-gavi/innovative-financing/iffim (accessed on 7 January 2021).

[55] Georgieva, K. (2020), “Opening remarks at a press briefing by Kristalina Georgieva following a conference call of the International Monetary and Financial Committee (IMFC)”, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/03/27/sp032720-opening-remarks-at-press-briefing-following-imfc-conference-call/ (accessed on 12 October 2020).

[2] Ghebreyesus, T. (2021), “WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at 148th session of the Executive Board”, World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-148th-session-of-the-executive-board (accessed on 1 February 2021).

[17] Ghebreyesus, T. (2020), “WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 21 December 2020”, World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---21-december-2020 (accessed on 13 January 2021).

[42] Glenton, C. and S. Lewin (2020), Communicating with the public about vaccines: Implementation considerations, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, http://www.covid19-evaluation-coalition.org/documents/VACCINES-Brief-1.pdf.

[60] Gneiting, U., N. Lusiani and I. Tamir (2020), Power, Profits and the Pandemic: From Corporate Extraction for the Few to an Economy that Works for All, Oxfam International, Oxford, UK, https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/power-profits-and-pandemic (accessed on 12 October 2020).

[1] Gurria, A. (2021), Covid vaccine rollout is the greatest test for mankind (webpage), CNBC, https://www.cnbc.com/video/2021/01/26/covid-vaccine-rollout-is-the-greatest-test-for-mankind-oecds-gurria.html (accessed on 1 February 2021).

[53] Jerving, S. (2020), “4 out of 5 Africans would take a COVID-19 vaccine: Africa CDC survey”, Devex, https://www.devex.com/news/4-out-of-5-africans-would-take-a-covid-19-vaccine-africa-cdc-survey-98812?access_key=OXMmhDICKsn_NniKAdcUn362xeFo3BeR&utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=newswire&utm_campaign=yourheadlines&utm_content=text&mkt_tok=eyJpIjoiTURBeVpUZGtaR016WXpnMSIsInQiOiJXZ3NuTXpDMm1kdHFCN3JtUW1CYjI2UERCU0ZYcnB3RFQzRSsyWnZlUnRCQjNHVGQ2enJqWVNQZllDY1RzR1BhUndKVjFnVkZzQ1wvMDNXMHBFVjRWUk9zR0RJbzBzNFZaXC80bFE5akVBXC9wUTVPWklcL3VhUFRoOFZ5Q1lTUHRGRm0ifQ%3D%3D (accessed on 7 January 2021).

[54] Kharas, H. and M. Dooley (2020), “Sustainable development finance proposals for the global COVID-19 response”, Global Working Paper, No. 141, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Development-Financing-Options_Final.pdf.

[45] Kim, J., M. Kessler and K. Poensgen (forthcoming), Financing transition in the health sector- What can DAC members do?, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[9] Kumar, R. (2021), “For the global development community, 7 predictions for 2021”, Devex, https://www.devex.com/news/for-the-global-development-community-7-predictions-for-2021-98845 (accessed on 1 February 2021).

[43] Lewin, S. and C. Glenton (2020), Effects of digital interventions for promoting vaccination uptake, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, http://www.covid19-evaluation-coalition.org/documents/VACCINES-Brief-2.pdf.

[32] Ministry of Health, New Zealand (n.d.), COVID-19: Vaccine planning (webpage), Ministry of Health, https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-response-planning/covid-19-vaccine-planning (accessed on 7 January 2021).

[19] NYT (2020), With First Dibs on Vaccines, Rich Countries Have ‘Cleared the Shelves’, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/15/us/coronavirus-vaccine-doses-reserved.html.

[40] OECD (2020), “Six decades of ODA: insights and outlook in the COVID-19 crisis”, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5e331623-en.

[3] OECD (2020), Development Co-operation Report 2020: Learning from Crises, Building Resilience, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f6d42aa5-en.

[48] OECD (2020), Frequently Asked Questions on the ODA Eligibility of COVID-19 Related Activities, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/ODA-eligibility_%20of_COVID-19_related_activities_final.pdf.

[5] OECD (2020), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2020 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/39a88ab1-en.

[39] OECD (2020), “Strengthening health systems during a pandemic: The role of development finance”, in OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/strengthening-health-systems-during-a-pandemic-the-role-of-development-finance-f762bf1c/ (accessed on 12 November 2020).

[36] OECD (2020), “Trade interdependencies in Covid-19 goods”, in OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/trade-interdependencies-in-covid-19-goods-79aaa1d6/ (accessed on 8 January 2021).

[59] OECD (2019), Health at a Glance 2019, OECD Publishing, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4dd50c09-en.

[44] OECD (n.d.), Creditor Reporting System (CRS), OECD.Stat, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=crs1# (accessed on 3 February 2021).

[46] OECD DAC (2020), “DAC High Level Meeting Communiqué 2020”, http://www.oecd.org/dac/development-assistance-committee/dac-high-level-meeting-communique-2020.htm (accessed on 25 November 2020).

[21] Oxfam (2020), “Campaigners warn that 9 out of 10 people in poor countries are set to miss out on COVID-19 vaccine next year”, Reliefweb, https://reliefweb.int/report/world/campaigners-warn-9-out-10-people-poor-countries-are-set-miss-out-covid-19-vaccine-next (accessed on 5 January 2021).

[20] Rabinovitch, A., M. Lubell and S. Scheer (2021), “Pizza-sized boxes and paying a premium: Israel’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout”, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-israel-vaccination/pizza-sized-boxes-and-paying-a-premium-israels-covid-19-vaccine-rollout-idUSKBN29B0KJ (accessed on 1 February 2021).

[51] Rogoff, K. (2020), “Here’s how policymakers can help the global economic recovery”, World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/09/pandemic-uncertainty-covid-coronavirus-economics-kenneth-rogoff/ (accessed on 5 January 2021).

[57] Sample, I. and N. Davis (2020), “Will Covid-19 mutate into a more dangerous virus?”, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/10/will-covid-19-mutate-into-a-more-dangerous-virus (accessed on 5 January 2021).

[10] Shepherd, C. and M. Seddon (2021), Chinese and Russian vaccines in high demand as world scrambles for doses, Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/f5fa265d-6616-4fcf-988a-deaefa532669 (accessed on 1 February 2021).

[31] So, A. and J. Woo (2020), “Reserving coronavirus disease 2019 vaccines for global access: Cross sectional analysis”, The BMJ, Vol. 371, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4750.

[8] The Economist Intelligence Unit (2021), Coronavirus vaccines: expect delays Q1 global forecast 2021, The Economist, London/New York/Hong Kong.

[56] UNCTAD (2020), Trade and Development Report 2020: From global pandemic to prosperity for all: Avoiding another lost decade, United Nations, Geneva, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/tdr2020_en.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2020).

[23] UNICEF (n.d.), “COVID-19 Vaccine Market Dashboard (webpage)”, https://www.unicef.org/supply/covid-19-vaccine-market-dashboard (accessed on 14 January 2021).

[38] UNICEF & WHO (2020), “In 2019, an estimated 14 million infants were still not reached by vaccination services”, UNICEF Data, https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/immunization/.

[58] UNOCHA (2021), COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan (web page), https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/952/summary (accessed on 3 February 2021).

[15] Usher, A. (2021), “Health systems neglected by COVID-19 donors”, The Lancet, Vol. 397, p. 83, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00029-5.

[35] Usher, A. (2020), South Africa and India push for COVID-19 patents ban, The Lancet, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32581-2.

[27] WHO (2021), “Access to COVID-19 tools funding commitment tracker”, World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/access-to-covid-19-tools-tracker (accessed on 3 February 2021).

[26] WHO (2020), ACT Accelerator: An economic investment case & financing requirements, World Health Organization, Geneva, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/an-economic-investment-case-financing-requirements (accessed on 8 January 2021).

[28] WHO (2020), ACT Accelerator: Status Report & Plan, World Health Organization, Geneva, https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/act-accelerator/status-report-plan-final-v2.pdf?sfvrsn=ee8f682b_4 (accessed on 8 January 2021).

[24] WHO (2020), “ACT-Accelerator update”, World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/news/item/26-06-2020-act-accelerator-update.

[50] WHO (2020), “Global equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines estimated to generate economic benefits of at least US$ 153 billion in 2020–21, and US$ 466 billion by 2025, in 10 major economies, according to new report by the Eurasia Group”, World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/news/item/03-12-2020-global-access-to-covid-19-vaccines-estimated-to-generate-economic-benefits-of-at-least-153-billion-in-2020-21 (accessed on 5 January 2021).

[12] WHO (2020), The Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator (webpage), World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/initiatives/act-accelerator (accessed on 25 November 2020).

[13] WHO (2020), Urgent Priorities & Financing Requirements at 10 November 2020, World Health Organization, Geneva, https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/urgent-priorities-financing-requirements-at-10-november-2020 (accessed on 13 January 2021).

[37] WHO & World Bank (2017), Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2017 Global Monitoring Report, World Health Organization, Geneva, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259817/9789241513555-eng.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2021).

[18] World Bank (2020), Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: Reversals of fortune, World Bank Group, Washington D.C., https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/34496/9781464816024.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2020).

[25] World Bank (2020), “World Bank approves $12 billion for COVID-19 vaccines”, World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/10/13/world-bank-approves-12-billion-for-covid-19-vaccines (accessed on 7 January 2021).

[61] WTO, WIPO and WHO (2020), Promoting Access to Medical Technologies and Innovation: Intersections between public health, intellectual property and trade, 2nd edition, World Health Organization, World Intellectual Property Organization, World Trade Organization, https://www.wto.org/English/res_e/booksp_e/who-wipo-wto_2020_e.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2021).

Contact

Kerri ELGAR (✉ kerri.elgar@oecd.org)

Ruth LOPERT (✉ ruth.lopert@oecd.org)

Eleanor CAREY (✉ eleanor.carey@oecd.org)

Martin WENZL (✉ martin.wenzl@oecd.org)

Notes

Research commissioned by Oxfam in 2020 found that 9 out of 10 people in poor countries were expected to miss out on a vaccine in 2021, despite research showing a higher level of vaccine acceptance in developing countries than in high-income countries (Chadwick and Monella, 2020[52]; Jerving, 2020[53]).

While this illustration is based on latest information, it should be noted that many of these doses are of vaccines still in development and may not eventuate.

Note this total figure for the vaccine pillar includes commitments for self-financing countries (see Figure 2) whereas the outstanding commitments largely concern the areas where funding is required to assist low and middle‑income countries.

To put the requested USD 9 billion for the ACT connector in perspective, it should be noted that the average annual health expenditure of an OECD country is estimated at about USD 4 000 per capita (OECD, 2019[59]). Of this, only some 20% is spent on supplies such as medicines and vaccines, with the remaining 80% spent on various services delivered by health systems. More specific to COVID-19, the OECD’s Working Party of Senior Budget Officials recently estimated that, on average, 0.19% of GDP would need to be invested in OECD countries (range 0.04-0.77%) for an effective COVID‑19 testing and vaccination programme. While the latter estimates only present order-of-magnitude estimates rather than precise cost accounting exercises, they illustrate that even in developed countries with mature health systems, additional investments in health systems capacity required for testing and vaccination campaigns can be substantial.

See the section below on development finance for an overview on development co-operation contributions so far to the ACT Accelerator.

For further information on these issues see the Development Co-operation Report 2020 (OECD, 2020[3]). For a discussion of TRIPS flexibility and other intellectual property issues such as patent pooling, see WHO, WIPO, & WTO (2020[61]) at https://www.wto.org/English/res_e/booksp_e/who-wipo-wto_2020_e.pdf. For a discussion of the political obstacles to agreement on these issues, see Gneiting, Lusiani and Tamir (2020[60]) at https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/power-profits-and-pandemic.

According to OECD calculations using World Customs Organisation list of COVID-19 goods (Annex A) and BACI International Trade data, the top five global exporters, which together account for 49% of trade, are China, Germany, Ireland, Switzerland and the United States. Similar patterns emerge for imports, where the top 20 countries represent 76% of trade in COVID-19 related goods; the United States alone represents 18% of global imports.

In 2019, 13.8 million infants worldwide did not benefit from routine immunisation services. Among those children, three out of five (8.8 million or 63%) were living in fragile contexts (UNICEF & WHO, 2020[38]).

This was despite despite the particularly high level of financial support on offer from the international community in response to the crisis, with 39.4% of the USD 9.5 billion humanitarian appeal already funded (UNOCHA, 2021[58]).

For more information, see the COVID-19 Global Evaluation Coalition website: http://www.covid19-evaluation-coalition.org.

For further information and clarification on the OECD Secretariat’s current interpretation on ODA eligibility of vaccine financing for developing countries, please refer to the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) document which offers preliminary guidance on ODA Reporting Directives, available at https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/ODA-eligibility_%20of_COVID-19_related_activities_final.pdf.

The DAC High Level Meeting Communique available to developing countries already fell short of what was needed to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals prior to the COVID-19 crisis. On top of this, developing countries experienced large private finance outflows, declining international trade opportunities and still-high debt levels due to the pandemic, resulting in serious pressures on their public finances. OECD DAC members have so far only pledged to “strive to protect” ODA budgets (OECD, 2020[3]).

Kharas and Dooley (2020[54]) estimate that the developing world faces a potential funding shortfall of close to USD 2 trillion to respond to the pandemic and associated economic shocks. See https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Development-Financing-Options_Final.pdf. Their estimate is close to that of the International Monetary Fund and the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), which put the shortfall at USD 2.5 trillion. See, respectively (Georgieva, 2020[55]) at https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/03/27/sp032720-opening-remarks-at-press-briefing-following-imfc-conference-call/ and (UNCTAD, 2020[56]) at https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/tdr2020_en.pdf.

These plausible future trajectories are not meant to be exhaustive but rather illustrative.

For further information see Sample & Davis (2020[57]) on research led by Martin Hibberd, Professor of emerging infectious diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. See also preliminary concerns based on two small studies, yet to be peer reviewed, as this paper went to publication on the South African variant and potential challenges around vaccine effectiveness at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.01.18.427166v1 and https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.01.15.426911v1.