Abstract

As the pandemic hit, governments asked legislatures to set aside or modify established budget practices and adopt solutions to expedite emergency responses. At the same time COVID-19 presented serious operational challenges for legislatures. They responded with creative solutions for swift action while maintaining effective oversight and accountability, demonstrating their resilience. Legislatures in most OECD countries were also supported with information and analysis from independent parliamentary budget offices and fiscal councils.

Introduction

Legislatures fulfil core functions of representation, law-making, and oversight. Governance goals of participation, transparency and accountability are directly related to these three functions. Legislative oversight, in particular, seeks to ensure that the executive and its agencies, or those to whom authority is delegated, remain responsive and accountable.

The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Budgetary Governance (OECD, 2015[1]) states that “parliament has a fundamental role in authorising budget decisions and in holding government to account ([1])” and that governments should “provide for an inclusive, participative and realistic debate on budgetary choices by offering opportunities for the parliament and its committees to engage with the budget process at all key stages of the budget cycle, both ex ante and ex post.” While OECD legislatures have a range of different legal frameworks, procedures, customs and traditions, all play an essential role in influencing and approving the budget and holding governments accountable for how money is spent.

During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, parliamentary oversight came under stress on several fronts. This policy brief describes the main challenges during this time: (1) the operations of legislatures were threatened by health and safety concerns, and (2) governments asked legislatures to accommodate swift policy action, either through faster budget procedures or by improvising new ones. The brief then describes how parliaments demonstrated their resilience by responding with flexible solutions to maintain oversight.

The policy brief highlights how legislatures were helped in their task by internal research units and independent fiscal institutions that provided timely background research, assessments of planning assumptions, and impartial analysis of policy initiatives to support legislatures in holding governments to account. Finally, it notes actions legislatures are considering to restore oversight norms as the urgency of policy responses subsides, both in reviewing the actions that took place during the initial response period and overseeing the next phase of the response as governments move to repair scarred economies, mend public finances, and return to medium-term objectives.

Part I: Challenges to budget oversight during the pandemic

The chain of oversight has many links, with parliaments and their committees performing well-established routines throughout the budget cycle. These routines include engaging in pre-budget debates, seeking stakeholder input, scrutinising the budget in the context of fiscal rules and medium and longer-term constraints, reviewing audit reports, and using their powers to compel information from the government and put it into the public sphere to promote transparency.

The COVID-19 crisis threatened to disrupt legislative oversight of national budgets by forcing the shut-down of parliaments out of concern for the safety of their members and the public. The pressure to respond quickly to support households and the economy also led governments to ask legislatures to shorten and amend long-established budget routines, potentially eliminating opportunities to exercise oversight and influence.

Legislatures faced operational disruptions

Legislatures faced significant challenges stemming from public health concerns. Many had to make rapid changes to their procedural rules and working arrangements.1 Disruptions to parliamentary work included:

Parliamentarians faced illnesses and had a high incidence of exposure to the virus. Legislators are highly engaged with the communities they represent and frequently meet face-to-face with stakeholders. This places them at high risk for exposure to a pandemic. In France, 18 members of the National Assembly tested positive for coronavirus by mid-March (Bargiacchi, 2020[2]). In the U.S., nine members of the House of Representatives and one U.S. senator tested positive for the virus by early April, while several more self-quarantined with symptoms or tested positive for antibodies from previous symptoms (Grisales and Carlsen, 2020[3]).

Parliaments suspended meetings and restricted access. Many legislatures took early or extended recesses while access to parliamentary grounds was closed until alternative arrangements could be implemented to deal with health concerns. For example, the UK parliament passed its main Coronavirus Act 2020 then broke for recess a week early, on 25 March instead of 31 March, and did not sit again until 21 April (UK Parliament, 2020[4]). Australia passed its Coronavirus Economic Response Package Omnibus Act 2020 on 23 March and suspended parliamentary sittings until August, but parliament was recalled intermittently for emergency sessions to pass additional legislation (Parliament of Australia, 2020[5]). Portugal’s parliament remained open during its declared emergency phase (45 days from 19 March until 2 May), but ordinary plenary sessions were reduced from three to one per week; sectoral committee meetings were also reduced from between two to three a week to one. Israel’s Knesset is a notable exception; legislators did not declare their usual spring recess, opting instead to remain in session in person to confront the crisis and allow for continuous oversight during the emergency response.

Legislatures that were suspended gradually returned partially or fully with safety precautions such as physical distancing and attendance caps, and video conferencing for virtual meetings. However, in some cases regional lockdowns continued to prevent representatives from traveling to or from their constituencies, raising concerns that the needs of remote communities would be underrepresented when passing emergency laws.

Parliamentarians and their support staff faced obstacles as remote working was implemented. Representatives and staff had to adjust to the technology used for virtual meetings. In some legislatures, security concerns held back the adoption of teleconferencing apps, particularly for confidential proceedings. Official transcripts of parliamentary debates commonly suffered considerable delays at first, causing difficulties for those unable to attend sessions in person. In multilingual countries with either statutory or practical translation requirements, the establishment of remote translation services was a barrier. In Canada, translation was cited as a major obstacle in timely adoption of virtual plenary and committees, with 40 of 70 translators unable to work from home due to health, technological, or childcare constraints (House of Commons of Canada, 2020[6]).

Some legislatures were caught in the middle of government formation. When the pandemic hit, several countries were in a period of transition following elections, with governments not yet formed. Within legislatures, committees may not have been established and inexperienced legislators had to step rapidly into their role. For example, during the caretaker period in Israel that resulted from the political deadlock following an early March election, the Knesset established a temporary Finance Committee with fewer powers than the permanent Finance Committee.2 Ireland was similarly affected following elections that led to its longest caretaker government in history from 8 February to 27 June. Although the Irish Parliament established a caretaker COVID-19 committee, there were no other oversight committees during that period.

The annual budget submission and reporting cycle was disrupted. Governments were unable to wait for opportunities within their scheduled budget calendar to react to the crisis. Countries with financial calendars that begin in the spring and summer were hit worst by the pandemic’s timing and most delayed the submission of routine budget laws and statements. For example, Australia, whose financial year runs from 1 July and ends on 30 June, delayed its routine budget from 12 May until 6 October, focusing on emergency pandemic-response legislation. Canada, whose financial year runs from 1 April to 30 March, postponed its scheduled spring budget indefinitely, opting for emergency sittings to pass legislation limited to the pandemic response.

Legislatures on calendar year cycles fared better and were largely able to react with supplementary budget bills (discussed below); however, scheduled opportunities for in-year adjustments were rushed forward. For example, the Netherlands broadly stuck to business-as-usual budgetary procedures, although the spring budgetary adjustment that typically occurs close to the deadline of 1 June was brought forward to 24 April.

Regular fiscal monitors, year-end financial statements, accounting submissions, and other departmental performance reports are crucial to ex post legislative scrutiny. Office closures and teleworking caused delays in publications, particularly among countries with 31 March financial year-ends. Reporting delays were compounded by a general low priority placed on the work of public accounts committees during the crisis.

Legislatures were asked to accommodate swift government action

Governments sought permission from their legislatures to speed emergency responses through the scrutiny and oversight process. Most countries had flexible budget routines and supplementary budget processes that allowed governments to respond quickly using business-as-usual procedures. Some governments, however, asked legislators to agree to more improvised procedures.3

Business-as-usual budget procedures

Even at the height of the crisis, some legislatures were able to work with governments to finance economic and social support and public health responses while maintaining business-as-usual budget procedures, albeit working more quickly than usual and with fiscal room created from the relaxation or suspension of fiscal rules.

These procedures included using supplementary budget bills to fund unexpected spending and emergencies. The use of supplementary budgets is in line with the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Budgetary Governance, which advocates that spending for new purposes or significant changes to previously approved allocations should be authorised by parliament (OECD, 2015[1]).

For example, Norway’s flexible budget procedures allowed it to provide COVID-19 emergency support and additional measures to strengthen the economy via a spring supplementary budget. Similarly, Sweden made no changes to its financial procedures but submitted 11 supplementary budget bills in the spring on top of its normal budget legislation.4 Korea introduced a third supplementary budget for the first time in 50 years, which was also its largest supplementary budget in history (Government of South Korea, 2020[7]).

Elsewhere, governments used supplementary budgets, but legislatures agreed to eliminate requirements for accompanying analysis. For example, in Finland there were no formal changes to procedures for its four supplementary budgets. But in practice, the requirement for new economic and revenue forecasts in supplementary budgets was dropped, and no reference to the financing of expenditure was required. In the Netherlands the spring supplementary budget adjustment did not contain the usual adjusted forecasts for the budgetary balance and national debt.

Governments also created fiscal space using provisions to reallocate spending across budget programmes. These have been used in past periods of fiscal stress and gained traction following the global financial crisis (OECD, 2019, p. 9[8]). For example, Austria, Czech Republic, France, Latvia, Lithuania, and Sweden reported relying on existing reallocation procedures to finance at least some of their emergency responses. However, as a result of the extreme need presented by the pandemic, reallocations from other programme areas was insufficient in most countries. For example, Israel, which typically tries to fund new in-year spending by internal budgetary reallocations, took the exceptional step of amending its Basic Law and approved a significant supplementary budget.

Governments relied on financial resources from contingency reserves and rainy-day funds. Contingency reserves are specific budget provisions or adjustments to planning assumptions to cover unexpected expenditure in limited amounts so that the government does not have to return to parliament for spending authorisation. A majority of OECD countries (23 countries) have contingency reserves or ‘margins for error’ specifically for events like natural disasters (OECD, 2019[8]); however these were not designed for the scale of economic downturns and fiscal interventions resulting from the COVID‑19 crisis. For example, in Latvia, the government is legally required to set aside a fiscal safety reserve of at least 0.1% of GDP, with the specific amount linked to its regular fiscal risks assessment. In the UK, parliament has long provided for unexpected contingency spending outside the normal budget process of up to 2% of the previous year’s cash spending. This was raised by the Contingencies Fund Act to 50% of 2019’s spending in a rushed procedure that drew criticism from parliamentarians (House of Commons, 2020[9]). In Sweden and Canada, a buffer is provided in planning assumptions that is based in economic uncertainty (smaller in the current year and growing further out). In Canada, the adjustments reduce planned revenues by between CAD 1.5 billion to 3 billion typically, while in Sweden the guideline for the margin is at least 1% of the ceiling-based expenditure for the current year (t), at least 1.5% for year t + 1, at least 2% for year t + 2 and at least 3% for year t + 3. These provisions partially absorbed the cost of initiatives to fight the crisis but were ultimately insufficient.

Seven OECD countries also set aside reserves in good times to mitigate the business cycle in bad times—so-called ‘rainy day’ funds (OECD, 2019[8]).5 Most tapped these funds to counteract the crisis either within a discretionary or rules-based framework, generally seeking parliamentary approval to do so. For example, Norway’s government presented a revised national budget that planned to withdraw a record amount from its sovereign wealth fund, accumulated from oil revenues, to combat the pandemic and support its economy. The withdrawal was consistent with the fund’s rules-based management tied to the economic cycle and the revised budget was approved by the parliament after the negotiated support of parties in the opposition (Norway Ministry of Finance, 2020[10]).

Governments sought additional fiscal flexibility by activating provisions to suspend fiscal rules. Fiscal frameworks in 29 OECD countries are bound by strict legal limits on borrowing or spending, either nationally or under an international treaty such as the EU’s Fiscal Compact (OECD, 2019, p. 48[8]).6 Fiscal rules typically contain mechanisms to accommodate emergency spending under specific criteria, the exclusion of one-off emergency policy responses from the calculation of fiscal aggregates, or cyclical fiscal targets that control for negative shocks to the economy. Legislatures are responsible for scrutinising compliance with fiscal rules and in some cases for approving their suspension. For example, in Germany the constitution forbids the federal government from running a structural deficit exceeding 0.35% of GDP under normal circumstances. The government has also followed a ‘schwarze Null’ or ‘black zero’ policy maintaining a formally balanced budget since 2015. In response to the pandemic, the government introduced a supplementary budget that would bring the federal deficit above the limits set by its corrective mechanisms and parliament approved that budget based on “exceptional circumstances”.

Improvised budget procedures

According to Schick (2009[11]), changes to budget procedures in response to the global financial crisis showed that a crisis tends to overwhelm established practices and lead to the creation of “improvised” budget procedures. This was also the case for most countries in responding to COVID‑19. In addition, power tends to become more top-down and centralised in a crisis.

Faced with unusual urgency and budget cycle timing challenges, most governments found that normal financial proceedings were inadequate to facilitate swift public health interventions and to implement measures to support households and businesses during lockdowns. They instead worked with their legislatures to improvise budget procedures to enact faster and greater relief. Many of these improvisations had the effect of limiting the time and scope for comprehensive parliamentary oversight.

Declaring states of emergency. The constitutions of most countries provide for the emergency suspension of business-as-usual checks and balances to empower the government to respond to a crisis quickly. Emergency acts concentrate power in the executive branch, allowing government to enact policy with fast-tracked or reduced parliamentary procedures, spend without parliamentary authorisation, or eliminate certain public procurement requirements. To limit the potential for prolonged power and abuse, constitutions or enabling legislation typically include provisions for states of emergencies to automatically expire and face judicial scrutiny. Enacting a state of emergency also often requires consent of the legislature. With few exceptions, states of emergency to face the COVID-19 crisis were taken with the involvement and consent of opposition parties.

Most executive actions taken using state of emergency declarations during the COVID-19 crisis focused on public health interventions that would have otherwise been restricted by individual and subnational rights, such as issuing stay-at-home orders and superseding subnational government authority over hospital systems. Others had more significant public financial management implications.

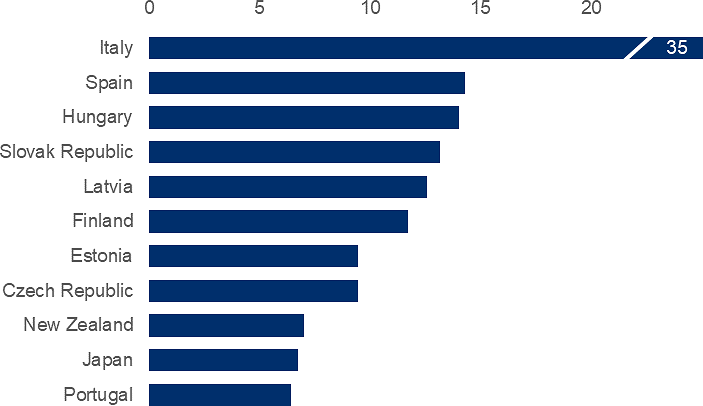

In total, states of emergency were declared in roughly half of OECD countries, with widely varying lengths of time (Figure 1). Several other countries, such as the UK and Canada, empowered their governments with authorities similar to declaring a state of emergency, without fully invoking formal emergency provisions.

Source: Authors.

Issuing decrees by heads of state. Decree powers are provided for under constitutions or financial administration laws to authorise urgent unforeseen expenditure in states of emergency or to avoid a shutdown of government when parliament is not meeting, such as when parliament is dissolved pending an election. These were repurposed in some countries for COVID-19 interventions or to sustain government during initial lockdowns until alternative safety procedures could be put in place in legislatures. In Belgium, a royal decree was used to freeze reductions and expirations of statutory unemployment benefits (King of Belgium, 2020[12]). In Canada, the crisis occurred before a new budget was submitted and parliament amended its Financial Administration Act to permit Governor General’s special warrants—previously used to fund government during election periods—to provide funding during the pandemic-related public health suspension of parliament, before members returned to pass a substantial crisis response bill in an emergency sitting.

Spain’s Constitution also provides the government with royal decree authority under article 86. The royal decree law allows the executive to legislate in cases of “extraordinary and urgent need” without having to go through the ordinary legislative procedure. Royal decree laws in Spain must always be ratified by the Congress of Deputies within 30 days from their approval by the Council of Ministers. By mid-June, over 15 Royal Decree laws had been used to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and were subsequently ratified by the Congress, of which 80% were processed as government bills through the Congress’s fast-track procedure.

Empowering cabinet or individual ministers with emergency expenditure and law-making authority. When time is of the essence, or when parliament itself is unable to meet, legislatures may delegate law-making authority for both primary and secondary legislation to the government and individual ministers, allowing them to enact policies without seeking additional parliamentary approval. In May 2020, Portugal introduced an amendment to its budget bill that granted cabinet the authority normally reserved by parliament to shift spending allocations across budgetary programmes (including from one ministry to another). Canada’s Act respecting certain measures in response to COVID-19 empowered cabinet with broad spending authority and granted the federal Minister of Employment and Social Development powers to change the Employment Insurance Act.

Using emergency advances and retroactive funding approval. National financial management laws may contain provisions for government to spend without ex ante parliament approval in cases of national interest or emergency. For example, in the Netherlands some supplementary budgets were introduced with reference to an article of the Dutch budgetary law (Comptabiliteitswet 2016) that grants the power to spend in the ‘national interest’ before formal parliamentary approval. In Australia, so-called “Advances” are permitted, allowing government to spend in the national interest and seek parliamentary authorisation later. In Switzerland, a joint Financial Delegation consisting of representatives from both chambers of the Swiss Parliament can approve urgent credit to fund government initiatives and did so three times during the emergency response to the crisis.

Using fast-tracked approval procedures. Fast-tracked procedures follow the main elements of routine parliamentary proceedings but on a much shorter time scale (House of Lords Constitution Committee, 2009[13]). Under fast-tracked procedures, the plenary and committees have less time to review and report on government proposals and to suggest amendments, in many cases passing spending bills in as little as a single day.

For example, the United Kingdom’s Coronavirus Act 2020 received royal assent on 25 March, having been fast-tracked through parliament in just four sitting days compared to the usual 11 weeks. In Sweden, a supplementary budget bill was submitted to parliament, passed, and promulgated by the Riksdag in two days (of which one was for opposition parties to submit counter proposals). Under normal circumstances the process would take several weeks.

In the Czech Republic, a state of legislative emergency (which was declared 12 March) empowered the President of the Chamber of Deputies to invoke a “summary consideration” procedure. Under summary consideration, first reading provisions are not applied and general debate in the plenary during second reading is strictly limited (speeches of individual members are no more than 5 minutes). With the consent of the Chamber of Deputies, the second reading may be cancelled entirely. Summary consideration was used to submit and pass three amendments to the State Budget Act, including the authorisation of reallocations of expenditure and increases in borrowing.

Fast-track procedures meant less committee scrutiny and fewer or no feedback opportunities and evidence-seeking from experts, interest groups, and civil society to improve policy design and increase legitimacy in the eyes of stakeholders. For example, in New Zealand, fast-tracked legislation to boost the economy with construction projects initially included provisions to bypass consultations with local councils, environmental groups and marginalised communities (Parliamentary Counsel Office, 2020[14]). The legislation was later amended to reinstate consultations after pressure from opposition parties.

Fast-tracked procedures risk being exploited by governments for actions unrelated to the crisis, such as attaching unpopular policy initiatives to emergency legislation, or exploiting the procedure purely for the political optics of moving quickly (House of Lords Constitution Committee, 2009[13]). Reduced scrutiny also increases the chance that policy will be ill-designed and require revision. Parliaments that have empowered governments with procedural changes to fast track legislation must make extra efforts to ensure that emergency actions remain in keeping with the will of the parliament and the electorate.

Limiting the role of upper chambers. Half of OECD legislatures are bi-cameral (OECD, 2019[8]). Upper chambers typically play a limited role in the budget process, having shorter time to debate, and often no right to amend or reject the budget. Only four OECD parliaments have upper and lower chambers with co-equal budgetary powers.7 In some cases, fast-track procedures reduced the role of the upper house further, or even eliminated it. For example, the upper house in Slovenia’s parliament customarily gives up the right to veto laws on urgent matters, shortening the promulgation timeline by eight days. Canada’s senate was asked not to amend or block bills, and instead send them through for royal assent immediately.

Limiting explanatory budget statements and other fiscal planning information. Governments reduced or eliminated explanatory budget statements and exercises that typically accompany budget bills, such as budget statements, formal speeches, and medium-term economic and fiscal outlooks. This was justified under time and resource constraints, with most public service efforts focused on rapid policy responses.

Governments were also commonly reluctant to publish medium-term fiscal planning documents given the enormous uncertainty in the economic and fiscal environment. Some shortened their explanatory statement horizons to the immediate financial year or suspended forecasts entirely. For example, in Iceland the Minister of Finance typically submits a five-year plan for the scrutiny of the Budget Committee by April; however, these planning documents were postponed until 1 October. Australia and Canada, who opted to postpone their spring budgets, also postponed their annual medium-term outlooks, releasing simplified economic and fiscal snapshots showing only the concurrent fiscal year (the former on 23 July and the latter on 8 July). The EU changed its guidance to member states for submitting medium-term objectives as part of the EU framework for monitoring economic policies and budget progress, allowing countries to shorten the planning horizon and simplify projections. Countries commonly opted to use the simplified EU framework and reflected it in their domestic planning publications.

Relying on extra-budgetary entities and external grants. Governments set up extra-budgetary funds with alternative financing arrangements or co-ordinated external funding. These arrangements often bypass annual votes and budget acts, complicating the job of legislators in forming a complete picture of the public finances or relief efforts. For example, Hungary established two extra-budgetary funds to fund its emergency response with transfers from the state budget and taxes on multinational companies and the financial sector, among other financial sources.8 The Lithuanian government worked with the Nordic Investment Bank to reduce the impact of the COVID-19 crisis with measures that included direct financing of struggling large businesses (Lithuania Ministry of Finance, 2020[15]).

Using alternative financing tools such as loans and guarantees. Governments relied heavily on balance sheet measures and contingent liabilities to fund emergency responses. These do not impact the reported deficit as cash outlays do. For example, a guarantee will only affect the government’s cash flow if the recipient defaults. Lithuania’s Economic and Financial Action Plan established several programmes that guaranteed the loans of businesses having difficulties borrowing to sustain themselves through the crisis. Although plans for loans and guarantees are usually submitted to the legislature for approval, they may be obscured in larger envelopes for the funding of independently operating state-owned enterprises, with little control over how funds are dispensed in practice, or parliamentarians may have less experience and expertise in overseeing these often complicated arrangements.

Part II: Solutions to maintain oversight

Legislatures overcame operational disruptions

Legislatures demonstrated resilience in overcoming operational disruptions by adopting a wide range of solutions to continue meeting. These included:

Physical separation and barriers. Legislatures adjusted their facilities to allow for in-person attendance while maintaining public health guidelines. For example, in Denmark voting lines were extended through the hallway connecting its chambers so that members could stay two metres apart and be let into the chamber ten members at a time, in accordance with the government’s health recommendations for the general public (UK House of Commons Library, 2020[16]). In Israel, seating for Knesset members was expanded to the press gallery to maintain safe distance and committees were divided across multiple rooms and linked by teleconference facilities. In Greece, a Plexiglas box was constructed around the speaker’s podium to protect nearby staff (ABC News, 2020[17]).

Virtual sittings, electronic voting, and digital democracy tools. Legislatures developed remote participation procedures, such as teleconference question periods and virtual committee meetings. Some even allowed legislators to vote remotely, either from within their parliamentary offices or from home. Some had no procedural or constitutional roadblocks to digital solutions and had already piloted such processes. For example, for plenary sessions Spain applied its existing remote voting procedures, which were originally developed for parliamentarians on parental leave or with serious illness (Congress of Deputies, 2012[18]). Others, such as the Polish Sejm, changed their parliamentary rules to allow virtual sessions and virtual voting for quarantined members, in the face of challenges to their constitutionality. In May, Latvia’s Saeima launched an e-Saeima platform allowing parliamentarians to attend plenary sittings and vote in real time from a secure website both inside and outside the parliament (Republic of Latvia Saeima, 2020[19]).

Legislatures also found ways to maintain citizen engagement and consultation through digital democracy tools. Many asked stakeholders and expert advisory groups to appear before committees using teleconferencing apps. In Spain, an email address was made available to receive suggestions and proposals from the public related to the work of four working groups created within a special COVID-19 committee.

Proxy voting or pairing of government and opposition members. Legislatures allowed members to eschew votes in person while preserving relative party composition using proxy voting or pairing. Proxy voting allows a parliamentarian who is unable to vote in person during a period of absence to nominate another parliamentarian to vote in their place. For example, on 10 June 2020 the UK parliament agreed to extend its trial proxy voting scheme for new parents absent for childcare responsibilities to MPs unable to attend parliamentary votes in person for pandemic-related medical or public-health reasons (UK Parliament, 2020[20]). MPs who wished to vote by proxy had to register to do so and nominate the parliamentarian who would cast the vote for them. Pairing is a matter of convention (enforced only by moral and political obligation), whereby party whips arrange deliberate absences across party members to cancel each other out. For example, Australia used long-standing pairing conventions in both the House of Representatives and the Senate for members that would need to travel a considerable distance by plane or were battling poor health to pass the government’s main stimulus legislation before parliament went into recess (Harris, 2020[21]).

Reduced quorum and attendance caps. Some legislatures restricted their attendance to maintain physical distancing and lessen the risks of contagion. In Germany, the rules of procedure of the Bundestag were changed to reduce quorum to 25% of members for plenary sessions and committees. In France, only the president (or a delegate) and a maximum of two Deputies from each party group were permitted to attend budget bill debates in the National Assembly (Library of Congress, 2020[22]). In Portugal, quorum for plenary sessions was reduced to 20% and committees were capped at a maximum of six in-person attendees.

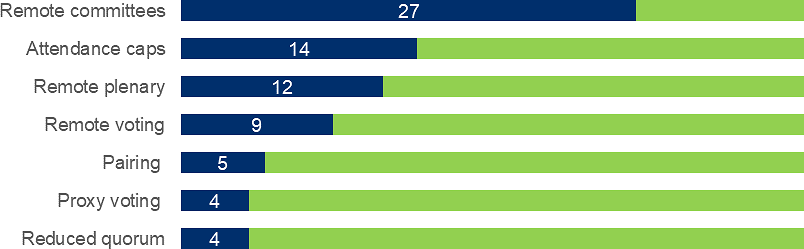

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of these solutions across the OECD. Virtually all sitting procedures were amended in some way. Remote committee hearings were a popular solution. Few legislatures implemented remote voting, pairing, or proxy voting, with some facing constitutional or other legal hurdles to do so (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2020[23]).

Source: (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2020[24]) and Parliamentary websites.

Legislatures maintained budget oversight while accommodating swift fiscal responses

Legislatures also demonstrated resilience by proactively implementing special oversight mechanisms and using their influence to amend acts to include greater transparency and checks on executive power.

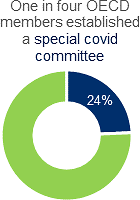

Legislatures established special COVID-19 committees or granted additional powers to existing committees. One quarter of parliaments in the OECD set up special COVID-19 committees or cross-party working groups to consider emergency responses as they were implemented.9 For example, the New Zealand Parliament created an opposition-chaired special committee from 25 March to 26 May 2020 with 11 members from all five parties to review and report on the government’s response to COVID-19 (New Zealand Parliament, 2020[25]). The committee had broad powers to summon testimony and documents from ministers and experts and meetings were publicly broadcasted on traditional media and online.

In Norway, a special committee to consider urgent matters related to the COVID-19 crisis was created on 16 March (The Storting, 2020[26]). The committee included the President of the Storting and one MP from each of the nine parliamentary party groups. In Austria, a special subcommittee of the Budget Committee responsible for parliamentary oversight and control of COVID-19 measures was created after parliamentarians raised objections over a lack of transparency in the government’s emergency response. In Israel, a Special Temporary Committee for Corona Issues was established to address both public health issues and monitor the economic crisis and its effect on certain sectors. In addition, a Special Temporary Committee on Labour and Welfare was established to monitor implications for employment and the well-being of households and to provide potential policy solutions.

In Spain, the Congress created a temporary special committee to receive proposals, hold discussions, and draft conclusions on measures to be taken for “social and economic recovery”. The committee had four major working groups on the subjects of (1) strengthening public health; (2) reactivating the economy and modernising the production model; (3) strengthening social protection and care systems and improving the tax system; and (4) Spain’s position with regard to the European Union. The committee was highly active, holding dozens of hearings with political decision-makers, experts, and academics on economic and social matters. Further, existing sectoral committees increased the frequency at which they called ministers and senior public service officials to hearings, and the Health Minister appeared weekly during the state of emergency period.

The US Congress built transparency and oversight mechanisms into the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, including a special congressional commission and two new inspector general arrangements to oversee the more than USD 2 trillion in relief. The House of Representatives also established a Select Subcommittee to examine and report on the government’s preparedness for the pandemic and its response.

The COVID-19 Congressional Oversight Commission (COC) is a temporary committee with five members appointed by congressional leaders from each chamber. The COC’s mandate is to report to Congress on the actions and transparency of the Treasury Secretary, Federal Reserve Board of Governors, and government in implementing the Act, specifically emergency loans and guarantees to US businesses in sectors that have experienced losses as a result of COVID-19. It will report every 30 days until 30 September 2025.

The Pandemic Response Accountability Committee (PRAC) is an independent oversight committee made up of 21 federal Inspectors General from the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency, an independent council within the executive branch. The committee’s purpose is to “promote transparency and conduct and support oversight of covered funds and the Coronavirus response to (1) prevent and detect fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement; and (2) mitigate major risks that cut across programme and agency boundaries.”

The Special Inspector General for Pandemic Recovery will sit on the PRAC and work within the Treasury Department to “conduct, supervise, and co-ordinate audits and investigations” of the actions of the Secretary of the Treasury related to any programme under the Act, submitting quarterly reports on findings. The holder of the position is nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate.

The Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis is composed of 12 members representing both parties and is appointed by the speaker of the House of Representatives, of which five may be recommended by the minority leader. The committee is authorised and directed to conduct an investigation and issue a final report on the government’s preparedness for the pandemic; the effectiveness of its response; any waste, abuse, and fraud associated with spending; and a wide range of other issues related to the COVID-19 crisis.

Notes: The Senate’s oversight will be carried out via the Senate Banking Committee in co-ordination with other Senate committees.

Sources: United States Government (2020), About the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee, https://pandemic.oversight.gov/about.

Congressional Research Service (2020), COVID-19 Congressional Oversight Commission (COC), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11304.

Congressional Research Service (2020), Special Inspector General for Pandemic Recovery: Responsibilities, Authority, and Appointment, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11328.

US House of Representatives Resolution 935, Establishing a Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis as a select investigative subcommittee of the Committee on Oversight and Reform, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-resolution/935/text.

The cornerstone of the U.S. response to the pandemic was the CARES Act, which contained clauses to establish several well-resourced commissions and committees with considerable legal powers to seek information to hold the government accountable for the more than USD 2 trillion in relief (Box 1).

Other parliaments have granted existing committees additional oversight powers in emergency legislation. For example, Canada’s House Finance Committee was given the power to recall the suspended parliament within 48 hours if it was unsatisfied with the transparency of the government’s reporting of spending measures or found other cause to do so.

Legislatures set limits on emergency spending. Some legislatures empowered governments with freedom for additional spending but limited it with caps. In Australia, for example, opposition parties successfully negotiated an agreement that the Finance Minister would be required to consult the opposition on “Advances to the Finance Minister” greater than AUD 1 billion. Advances fund expenditures during the year without parliamentary approval if an urgent need is not sufficiently provided for in existing appropriations.

Legislatures required sunset clauses and contingent renewal accountability mechanisms. Some legislatures insisted that emergency laws contain sunset clauses (fixed end dates). For example, opposition members in Canada agreed to support the government’s bill to empower ministers to be able to make changes to social benefits legislation without parliament’s approval, provided the ministerial orders contained specific end dates or would automatically expire after one year.

Some legislatures pressured governments to include renewals of legislation beyond a fixed time horizon contingent on scheduled parliamentary or judicial reviews. For example, after pressure from members of the House of Commons, the UK’s Coronavirus Act 2020 was amended by the government to require six-month reviews and renewals by the legislature. In Switzerland, the government issued many ordinances based on an article of the Swiss Constitution that permits the government to take certain emergency actions to confront serious disruptions to public order, but parliament required the ordinances to be limited in duration. In Ireland, legislators argued successfully in favour of an amendment to proposed emergency legislation providing for a review by parliament by 9 November 2020, after which a vote would need to be taken on whether to renew the legislation or let it expire.

Legislatures required additional monitoring and reporting requirements. In the absence of robust scrutiny during the passage of legislation, post-legislative scrutiny will take on greater importance as legislatures monitor the intended and unintended effects of policies and suggest corrections where necessary. Some legislatures passed emergency legislation conditional on scheduled reporting. In Canada the Minister of Finance was required by An Act respecting certain measures in response to COVID-19 to report to the budget committee every two weeks on the use of emergency financial powers that were granted. The Austrian Parliament passed a resolution to improve the traceability of spending and established new reporting requirements.

In Israel, the Temporary Finance Committee of the caretaker parliament successfully compelled government to improve the transparency of its initially vague and broad emergency aid package by including a breakdown of the additional funding for areas such as health, social security, and assistance to businesses and employers and obliged the Ministry of Finance to publish planned expenditure details on its website. The Knesset also introduced provisions to require the Finance Minister to send the Finance Committee a monthly report on actual expenditures and to seek the approval of the Finance Committee for any significant reallocations between components of the plan.

In Spain, the parliament added a provision to the state of emergency requiring the government to inform parliament on a weekly basis of measures taken during the emergency period.

Legislatures involved national auditors early in assessing pandemic responses. Some legislatures ensured that auditors were involved in assessing COVID-19 emergency responses from the beginning, such as by requiring emergency legislation to have provisions for regular audits and analytical reports from the country’s supreme audit institution.

The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) agreed to requests from the Shadow Minister for Finance to undertake regular assurance reviews of the Advances to the Finance Minister, which provided the Finance Minister with considerable funding to meet urgent and unexpected expenditures (ANAO, 2020[27]).

The German Bundesrechnungshof, or Federal Court of Auditors, sent an initial analysis and assessment paper to the Bundestag’s Budget Committee in May and committed to further monitoring of the government’s relief and stimulus packages.

The Netherlands’ Court of Audit warned in its annual report that parliament had to be prudent in its oversight of public spending on emergency measures and launched a monitor to show the costs and impact of responses to the pandemic (Court of Audit, 2020[28]). The Czech State Audit Office amended its audit plan for 2020 to carry out an audit of public funds spent on protective equipment, with plans to publish in November 2020 and present to the Committee on the Budget Control of the Chamber of Deputies.

Part III: Independent fiscal institutions

Legislators were supported in their scrutiny role by their own internal budget research services which quickly stepped in to establish and populate dedicated COVID-19 research hubs and provide budgetary analysis and new report series, factsheets and briefings.

The crisis also brought to the fore the importance of the role of independent fiscal institutions (independent parliamentary budget offices and fiscal councils, or IFIs) that have been established in most OECD countries since the financial crisis. IFIs stepped up to provide rapid analysis of emergency measures which was particularly important in informing the parliamentary debate and in promoting transparency and accountability on emergency spending related to the pandemic.

The OECD conducted and published a review describing the response of IFIs during the first rescue phase of the crisis (OECD, 2020[29]).10 The review identified four main actions that IFIs took:

- 1.

Providing rapid analysis of the economic and/or budgetary impact of the pandemic, including self-initiated briefing notes; responses to requests from committees and individual legislators, economic and fiscal forecasts in real time; economic and fiscal scenario analysis; and assessments of government planning assumptions (see Figure 3. Breakdown of rapid analysis from members of the OECD PBO Network (number of IFIs)Figure 3).

- 2.

Monitoring activation and implementation of escape clauses as governments moved to suspend fiscal rules to respond to the pandemic.

- 3.

Costing emergency legislation either in an official capacity, upon request of legislators, or as self-initiated scrutiny of official figures.

- 4.

Promoting transparency and accountability of the emergency procedures that governments and legislatures may have introduced to expedite responses to the crisis.

In many countries, IFIs provided the only economic and fiscal forecasts and scenario analysis during the crisis that legislatures could draw on, as governments were reluctant to provide planning assumptions because of the high uncertainty and potential political consequences of prediction errors. One third of IFIs responded directly to requests from committees and individual legislators to supply analysis and commentary on pandemic-related issues. For example, the president of Spain’s Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility (Autoridad Independiente de Responsabilidad Fiscal, AIReF) appeared before the Treasury Committee of the Congress of Deputies and the newly-created Social and Economic Recovery Committee to provide her views on the government’s COVID‑19 response and offered her institution’s technical analysis capacity to the service of parliament.

Note: The dataset includes 40 IFIs, covering institutions within the OECD (including two sub-national IFIs and one independent advisory body established at the European level) and Brazil.

Source: OECD (2020[29])

IFIs’ opinions informed parliamentary deliberations on suspension of national fiscal rules—for example, the Italian Parliamentary Budget Office provided a memorandum on the government’s request to deviate from the fiscal rules to the parliamentary budget committees before the parliamentary vote (Parliamentary Budget Office, 2020[30]).

Around 40% of OECD IFIs had responsibility for costing emergency legislation put before parliaments to fight the pandemic. Seventeen did so and published their results (as of 20 May 2020). For example, the United States Congressional Budget Office (CBO) produced cost estimates for the Congress for a series of bills addressing the pandemic and its effects. In early April, the CBO also released a preliminary update of its economic baseline for cost estimates, updated its economic projections through 2021, and produced preliminary estimates of federal deficits and debt for 2020 and 2021, reflecting the effects of the pandemic and the legislation that had been enacted in response.

All IFIs supported their legislatures in promoting fiscal transparency and accountability. Several IFIs used their independent voice to draw the legislature’s attention to issues of transparency. For example, the Austrian PBO highlighted a lack of transparency on COVID-19 measures, inadequate information for parliamentarians, and the need for comprehensive reporting to parliament. Its criticisms and recommendations for the minimum content of reports attracted public attention and led directly to a successful joint motion by the opposition to establish the COVID-19 subcommittee of the Budget Committee (described above) along with successful parliamentary resolutions calling for increased reporting requirements, greater spending details, and separate accounts to trace COVID-19 funds through central and line ministries. The Canadian PBO warned publicly that the government’s draft emergency COVID-19 legislation was “concerning” and that measures were “totally unprecedented”, in some cases allowing the government to “do whatever they want” despite the will of Parliament (Snyder and Tumilty, 2020[31]). The PBO’s comments were delivered in statements to several national newspapers and the bill was subsequently amended following backlash from opposition parties and the public.

Part IV: Oversight as countries recover

As lockdowns are lifted and the recovery gets underway, some legislatures have expressed concerns that governments will continue to take advantage of emergency procedures. For example, an extra-budgetary fund introduced to support the economy might become a tool during normal times when the government wants to avoid parliamentary budget controls.

This potential one-way expansion of executive powers has been described as the “crisis ratchet”. However, there is little empirical evidence of trends to this effect over time or following past emergencies (Posner and Vermeule, 2003[32]). This may be because legislatures consciously reassert their role in the policy and budgeting process following a crisis. Indeed, OECD legislatures have reported that they will be taking specific steps to avoid long-term post-emergency institutional damage following the pandemic.

Some legislatures have announced formal reviews. For example, in Switzerland the Federal Assembly has announced a review of the preparedness of the government and public service to face the crisis, and how the Federal Council and other bodies managed their responses (Federal Assembly of Switzerland, 2020[33]). The review aims to strengthen the accountability of the Federal Council and the federal administration and to draw lessons for the management of future crises.

Other legislatures will simply follow through on procedures established to limit emergency measures, such as sunset provisions or the scheduled reversal of suspensions to multi-year planning frameworks. But particular attention should be paid to the following, which will be important in limiting the crisis ratchet of the pandemic.

Ensure that financial reporting and other oversight information is reinstated. Data collection and publication has suffered from shutdowns and physical distancing. This includes both public financial management data and official statistics programmes. Many data programmes will be dealing with interruptions and departments may be tempted to abandon well-established products. Parliaments will need to monitor whether the departments and agencies responsible for reinstating information and producing additional oversight information are adequately empowered with information access and resources to fulfil their responsibilities.

Re-examine emergency measures for effectiveness, technical errors, and unintended consequences. Many COVID-19 laws were passed in the form of omnibus bills with volumes of measures packed into texts that received little scrutiny. Legislatures will need to revisit these bills and ensure that goals are being achieved effectively and that there are no unintended consequences.

Make use of auditors to examine pandemic issues. SAIs will feature prominently in ex post accountability of emergency responses to provide the analysis legislators need on the effectiveness and efficiency of emergency responses. Legislatures should be conscious that the scale of responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the special requests that are already being received by SAIs, will place considerable demand on the resources of national auditors.

Bring back feedback and consultation in the recovery programmes. Stakeholder consultation, expert policy advice, and participatory initiatives were largely set aside as governments and legislatures focused on speed. Legislatures have generally been slow to adopt digital tools and approaches that could rapidly reach a wider group of stakeholders during a crisis. For budget matters in particular, legislatures continue to rely mainly on traditional forums for participation such as in-person hearings of permanent committees (OECD, 2019[8]). The pandemic forced many parliaments to make greater use of digital tools. There is an opportunity to use these tools to expand how legislatures solicit policy input from stakeholders, provided potential risks are weighed and security concerns are overcome. Countries could look to France, Greece, and Switzerland, which hold online policy debates among social media participants, and Austria, which has experimented with an interactive crowdsourcing platform for scrutinising planned reforms (OECD, 2018[34]).

There are also questions legislatures are likely to face as the crisis moves beyond emergency relief to recovery spending and as they prepare for the next emergency. These include:

How will fiscal space be rebuilt during the recovery? The levers with which to return to medium-term budget objectives will be under the public’s microscope and legislators will need to ensure that they have the tools and support to adequately assess government plans. Independent fiscal institutions can play an important role in this debate.

Will fiscal frameworks be adjusted to mitigate future crises? Legislators may review the performance of their country’s fiscal framework in responding to the crisis, and perhaps more importantly, its performance in mitigating the crisis.

Should public policy be reprioritised during the recovery? Already many governments have issued statements that the crisis provides an opportunity to adjust priorities during the economic recovery. Parliamentarians will be asked to scrutinise and influence these reprioritisations. Among them:

Prioritising climate change. Governments are building environmental considerations into recovery programmes. These may require new tools and new oversight bodies to monitor, such as green budgeting. For example, Canada has proposed attaching environmental reporting conditions to emergency loans to businesses. The EU has promoted the Green Deal as a cornerstone of the economic response to the pandemic.

Prioritising gender dimensions of the recovery. The economic and social impact of the pandemic and lockdowns has affected women more than men. Recovery initiatives may be geared toward addressing this gender disparity.

Conclusions

In responding to the COVID-19 crisis, governments had to mobilise resources and act quickly. The challenges legislatures faced in simply holding regular parliamentary sittings during a pandemic, combined with the pressures they received from governements to expedite legislation, were a stress test that threatened to weaken parliamentary oversight and influence in many jurisdictions.

The operational disruptions to legislatures themselves were unique circumstances for which few had planned. Legislators faced many of the same challenges of remote working and illness as were being faced by households and businesses, compounded by formal constitutional requirements and strict legal procedures.

Legislators are accustomed to navigating national budget cycles that thrive when changes are routine and at the margin. Traditional built-in flexibility such as scheduled supplementary budgets and scope for limited reallocation of funds across spending categories was ill suited for what was for many countries the largest peacetime shock to national economies and public finances in history.

But throughout the crisis, OECD legislatures demonstrated resilience and ensured that emergency responses were fast, representative of the public interest, and that governments could ultimately be held accountable for their policies. In doing so, they commonly departed from usual oversight practices, but crafted creative improvisations to overcome both operational safety restrictions and procedural challenges to reassert their influence in the budget process. Despite the considerable transfer of powers over the public purse to executive governments, the pandemic holds many reassuring examples of legislators from both governing and opposition parties asserting influence over emergency responses.

Their resilience was, in part, achieved through the support of still young independent parliamentary budget offices and fiscal councils established to foster and ensure institutional knowledge and formal accountability and transparency fail-safes. Although those institutions themselves suffered from remote working challenges and shortened legislative timelines, they delivered briefing notes, economic and fiscal analysis, cost estimates, and other interventions to promote transparency and accountability.

As the urgency of the public health crisis subsides, legislatures and the institutions that support them will play a key role in ensuring accountability and transparency during the next phase of economic recovery. The OECD will continue to monitor how legislatures reassert their role as guardians of the public purse and return to less urgent, but no less important, deliberative policy formulation and oversight.

References

[17] ABC News (2020), Plexiglass houses: Parliaments adapt to the coronavirus age, https://abcnews.go.com/Health/wireStory/plexiglass-houses-parliaments-adapt-coronavirus-age-70630464 (accessed on 27 July 2020).

[27] ANAO (2020), Request for audit: The Australian Government’s economic response to COVID-19, https://www.anao.gov.au/work/request/the-australian-government-economic-response-to-covid-19 (accessed on 7 July 2020).

[2] Bargiacchi, M. (2020), “26 cas de coronavirus Covid-19 à l’Assemblée nationale”, France bleu, https://www.francebleu.fr/infos/politique/l-assemblee-nationale-foyer-de-coronavirus-covid-19-1584430482 (accessed on 27 July 2020).

[18] Congress of Deputies (2012), Resolution of the Bureau of the Congress of Deputies, of May 21, 2012, for the development of the telematic voting procedure, http://www.congreso.es/portal/page/portal/Congreso/Congreso/Hist_Normas/Norm/NormRes/21052012vottelem (accessed on 27 July 2020).

[28] Court of Audit (2020), The Court of Audit is investigating the fight against the corona crisis, https://www.rekenkamer.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/06/08/algemene-rekenkamer-onderzoekt-bestrijding-coronacrisis (accessed on 9 July 2020).

[33] Federal Assembly of Switzerland (2020), The Management Commitees of the Federal Chambers launch an inspection to assess the management of the COVID-19 pandemic by the federal authorities, https://www.parlament.ch/press-releases/Pages/mm-gpk-n-s-2020-05-26.aspx (accessed on 27 July 2020).

[7] Government of South Korea (2020), 3rd Supplementary Budget of 2020 Passed, http://english.moef.go.kr/pc/selectTbPressCenterDtl.do;jsessionid=7R5H9vUbz1S-57wqVluRN0NL.node20?boardCd=N0001&seq=4932 (accessed on 27 July 2020).

[3] Grisales, C. and A. Carlsen (2020), How Many Lawmakers Got The Coronavirus Or Self-Quarantined? : NPR, https://www.npr.org/2020/04/15/833692377/how-the-coronavirus-has-affected-individual-members-of-congress?t=1595869094707 (accessed on 27 July 2020).

[21] Harris, R. (2020), Coronavirus: Scaled-back Parliament to meet for stimulus legislation as building access restricted, https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/scaled-back-parliament-to-meet-for-stimulus-legislation-as-building-access-restricted-20200316-p54anr.html.

[9] House of Commons (2020), HC Deb, 24 March 2020, c. 281, https://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=2020-03-24b.281.1 (accessed on 25 July 2020).

[6] House of Commons of Canada (2020), Committee Report No. 5 - Parliamentary Duties and the COVID-19 Pandemic, https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/43-1/PROC/report-5/page-207.

[13] House of Lords Constitution Committee (2009), Fast-track Legislation: Constitutional Implications and Safeguards, United Kingdown (15th Report, Session 2008-09, HL Paper 116).

[24] Inter-Parliamentary Union (2020), Country compilation of parliamentary responses to the pandemic, https://www.ipu.org/country-compilation-parliamentary-responses-pandemic (accessed on 12 July 2020).

[23] Inter-Parliamentary Union (2020), Voices: Legislating in times of pandemic (Laura Rojas), https://www.ipu.org/news/voices/2020-05/legislating-in-times-pandemic (accessed on 8 July 2020).

[12] King of Belgium (2020), Royal Decree on relaxing conditions under which the unemployed access full unemployment benefits, http://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/eli/arrete/2020/04/23/2020202000/moniteur.

[22] Library of Congress (2020), Continuity of Legislative Activities during Emergency Situations, https://www.loc.gov/law/help/emergency-legislative-activities/index.php.

[15] Lithuania Ministry of Finance (2020), Nordic-Baltic Ministers, Governors of the Nordic Investment Bank (NIB), have today invited the Bank to take swift action to help alleviate the effects from the corona crisis (web page), http://finmin.lrv.lt/en/news/nordic-baltic-ministers-governors-of-the-nordic-investment-bank-nib-have-today-invited-the-bank-to-take-swift-action-to-help-alleviate-the-effects-from-the-corona-crisis.

[25] New Zealand Parliament (2020), COVID-19: What is the Epidemic Response Committee?, https://www.parliament.nz/en/get-involved/features/covid-19-what-is-the-epidemic-response-committee/.

[10] Norway Ministry of Finance (2020), Revised National Budget: A budget to help us safely reclaim ordinary life, https://www.regjeringen.no/en/aktuelt/a-budget-to-help-us-safely-reclaim-ordinary-life/id2701787/.

[35] OECD (2020), Financial Management and reporting in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, Newsletter to the SBO Network on Financial Management and Reporting.

[29] OECD (2020), Independent fiscal institutions: promoting transparency and supporting accountability during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, OECD Publishing, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/independent-fiscal-institutions-promoting-fiscal-transparency-and-accountability-during-the-coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic-d853f8be/.

[8] OECD (2019), Budgeting and Public Expenditures in OECD Countries 2019, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/e192ed6f-en.

[34] OECD (2018), Austria Country Profile, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/9789264303072-12-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/9789264303072-12-en.

[1] OECD (2015), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Budgetary Governance, OECD Publishing, http://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/Recommendation-of-the-Council-on-Budgetary-Governance.pdf.

[5] Parliament of Australia (2020), COVID-19 and parliamentary sittings, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/FlagPost/2020/April/COVID-19_and_parliamentary_sittings (accessed on 27 July 2020).

[30] Parliamentary Budget Office (2020), Memo of the President of the UPB on the Report to Parliament prepared pursuant to Law 243/2012, http://en.upbilancio.it/memorandum-of-the-chairman-of-the-pbo-on-the-report-to-parliament-prepared-pursuant-to-law-2432012.

[14] Parliamentary Counsel Office (2020), “COVID-19 Recovery (Fast-track Consenting) Act 2020, Schedule 2: Listed projects”, New Zealand Legislation, http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2020/0035/latest/LMS345621.html.

[32] Posner, E. and A. Vermeule (2003), “Accommodating emergencies”, Stanford Law Review, pp. 605-644.

[19] Republic of Latvia Saeima (2020), The Latvian Parliament ready for work using the e-Saeima platfor, https://www.saeima.lv/en/news/saeima-news/28986-the-latvian-parliament-ready-for-work-using-the-e-saeima-platform (accessed on 16 July 2020).

[11] Schick, A. (2009), “Crisis budgeting”, OECD Journal on budgeting, Vol. 9/3, pp. 1-14.

[31] Snyder, J. and R. Tumilty (2020), COVID-19 bill would give Liberals power to raise taxes without parliamentary approval until end of 2021 | National Post, https://nationalpost.com/news/covid-19-bill-would-give-liberal-government-power-to-raise-taxes-without-parliamentary-approval-until-end-of-2021 (accessed on 27 July 2020).

[26] The Storting (2020), The Storting constitutes coronavirus special committee, https://www.stortinget.no/en/In-English/About-the-Storting/News-archive/Front-page-news/2019-2020/the-storting-constitutes-coronavirus-special-committee/ (accessed on 27 July 2020).

[16] UK House of Commons Library (2020), Coronavirus: Changes to practice and procedure in the UK and other parliaments, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8874/.

[20] UK Parliament (2020), Amended Proxy Voting Scheme, https://www.parliament.uk/business/publications/commons/proxy-voting-scheme/.

[4] UK Parliament (2020), Changes to House of Lords sittings and business, https://www.parliament.uk/business/news/2020/march/changes-to-house-of-lords-sittings-and-business/ (accessed on 27 July 2020).

Notes

Unless a specific reference is cited, the observations in this report were accumulated from a questionnaire sent to members of the OECD PBO Network and the country monitoring underlying OECD (2020[29]).

In normal times, the Knesset’s Finance Committee has considerable authority over budget allocations and approvals, but these were delegated instead to the Accountant General of the Minister of Finance, a government-appointed position.

This section has been prepared in coordination with survey responses received from delegates of the SBO Network on Financial Management and Reporting from May to August 2020, circulated in a newsletter to the network.

According to a survey response received 18 June 2020.

These include Norway, Sweden, Hungary, Latvia, Chile, Estonia, and Mexico.

The 29 countries mentioned includes the addition of data from Lithuania which was not included in (OECD, 2019[8]).

Chile, Italy, Switzerland, and the United States.

The two funds were the Economy Protection Fund, aimed at restarting the economy and supporting the job market, and the Disease Control Fund, aimed at financing health-related expenditures such as purchasing medical equipment and building temporary emergency hospitals.

Early formal COVID-19 special committees were established in Australia, Canada, Israel, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, and the United States, among others. Mexico formed a cross-party working group to monitor the government’s response, and the United Kingdom established an all-party parliamentary group to conduct an independent inquiry into the handling of the coronavirus crisis. Many more parliaments created ex post public inquiry committees to assess responses, for example in Denmark, Czech Republic, and Ireland.

See (OECD, 2020[29]) for a detailed description of IFI actions by country.