Abstract

This note focuses on the implications of COVID-19 on rural development and the policy responses that OECD member countries are adopting. It first discusses the economic effects on rural regions followed by an identification of opportunities and associated challenges. The note then summarises how governments are responding to the crisis and identifies how governments can prepare to leverage opportunities. Delegates of the Working Party on Rural Policy discussed and shared their input to a first draft of this note at the 23rd meeting on 20 April, 2020 and provided some examples that have been incorporated. The note will be subsequently revised with further inputs provided by countries.

Introduction

Every major crisis, such as the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, brings opportunities to rethink our systems and make them more resilient to future shocks. This is also true for rural regions. Rural economies have provided essential goods and services - including food and energy - to households, hospitals and health centres during confinement periods. In some countries, rural areas have also served as a temporary, but safer, location for urban dwellers. Taking a longer perspective, the pandemic can change consumption and production patterns, remote working habits and forms of mobility, which may open new opportunities for sustainable growth in rural regions. Revisiting globalisation of production chains could also open new opportunities in some rural areas.

However, rural businesses and dwellers have been also confronted with several pressures, including those emerging from the pandemic and associated containment measures. Demographic characteristics (a higher share of elderly population) and geographic features (larger distances to access health care centres), coupled with reduced health care staff and facilities, definitely hamper the ability of rural regions to respond to the pandemic. Moreover, the overall slowdown in aggregate demand has affected some primary sectors, and the expected further slow-down in trade and global demand will hit rural economies severely given their higher reliance on tradable activities, such as mining and tourism.

In this context, this note assesses the potential effects and challenges of the pandemic on the economy and well-being of rural regions over the short-term and medium/long term, but also identifies a number of possible opportunities. Finally, it outlines a number of policy responses relevant for rural areas.

COVID-19: What economic and social effects on rural regions?

Several factors are at play. Over the short run, the temporary relocation of urban dwellers to rural areas may have produced positive consumption effects, despite the overall decline in demand with confinement measures. Using transactional data, researchers in the US observed a temporary increase in consumption of primary consumption goods, while the demand for luxury goods declined both in urban and rural areas.1 Rural areas specialised in agriculture production may have benefited from these trends.

Nonetheless, rural regions have been particularly vulnerable because they have:

A large share of population who are at higher risk for severe illness, notably the elderly and the poor.

A much less diversified economy.

A high share of workers in essential jobs (agriculture, food processing, etc.) coupled with a limited capability to undertake these jobs from home. This makes telework and social distancing much harder to implement.

Lower incomes and lower savings may have forced rural people to continue to work and/or not visit the hospital when needed.

Health centres that are typically not well suited for dealing with COVID-19 (i.e. lack of ICUs and doctors with specialised skills).

Larger distance to access hospitals, testing centres, etc.

A large digital divide, with lower accessibility to internet (both in coverage and connection speed) and fewer people with adequate devices and the required skills to use them.2

Although primary sectors, especially agriculture, have typically been classified as an essential activity, and therefore maintained during confinement, high labour intensive sectors critical for rural economies are experiencing labour shortages. Shortages of seasonal and temporary workers are a significant challenge, with some jurisdictions reliant on foreign seasonal workers indicating they may lose a planting season as a result of border closures that have impeded the flow of labour3. There are also higher controls on cargo trade that affect food markets and could create an additional burden for rural food business.4 The current crisis is also disrupting the functioning of food supply chains, in particular through labour shortages and disruptions to transport and logistics services.5

These disruptions are affecting the agro-food sector in some rural regions – driving down prices of some products and putting pressure on rural business. For example, in the UK a quarter of dairy farms have become financially unviable because of falls in milk demand and prices.6 The impact on food demand is particularly severe for suppliers to tourism or the aviation sector. Other bottlenecks for rural business include tighter credit conditions, supply shortages or delays for processing plants and farmers (i.e. shortage of packaging for some agro-food products in Europe).

Rural regions will also face important challenges to deliver public services. With increased demand for public health services, small rural areas will face particularly acute shortages of medical workers, an issues that might be exacerbated by the extra demand if urban dwellers temporarily increase the rural population. Furthermore, some rural communities have a significant share of their populations at higher risk. These include the elderly, mining communities (e.g. in the US, coal mine workers are more likely to suffer from respiratory issues),7 Indigenous peoples8, and populations with larger shares of smoking9 and obesity rates.10

Rural communities specialised in some particularly exposed sectors may be more vulnerable to the global slowdown. Identified vulnerable sectors11 include mining/oil and gas, transportation, employment services, travel arrangements, and leisure and hospitality. For example, the OECD estimates that the international tourism economy is expected to fall in 2020 between 60% and 80%. Yet, depending on the countries, rural regions may see increased domestic tourism from displaced international travel. In the case of mining, unlike the 2008 financial crisis, the drop in demand for minerals and metals has been accompanied by significant supply-side upheaval due to restriction in mining operations, particularly affecting mining communities. In contrast, rural regions specialised in agriculture may prove more resilient.12

In terms of rural regions specialised in manufacturing, their vulnerability will depend on the participation in global value chains (GVCs). As production and sourcing move closer to end users, these processes could also open new opportunities in some rural areas, through an increased demand for basic services and proximity products.

Over the medium and long term, rural regions will remain vulnerable with a deepening of the global slowdown. The gap in GDP per capita, productivity levels and service delivery between rural areas and metropolitan cities widened since the 2008 global financial crisis, due to a lower diversification and a higher dependency on tradeable export markets for primary goods (raw materials, forestry, agro-food) and imports of non-primary raw materials or intermediate goods as compared to cities. This gap will likely be amplified13 in the coming years. Likewise, the aftermath of this crisis may further push rural-related economic sectors (mining, forestry) to speed up automation of certain tasks, challenging local labour markets. On the other hand, the COVID-19 crisis may accelerate the uptake and usage of digital technologies in rural areas, increasing the attractiveness of rural areas for people and firms. The gaps in access to digital services during the pandemic have elevated the political discussion on whether having access to quality broadband across all the territory should be a basic right for development. For this reason, it is highly relevant to identify the opportunities emerging from this crisis and design appropriate strategies to seize them.

Identifying opportunities

The COVID-19 crisis is accelerating the use and diffusion of digital tools. Confinement measures are fomenting remote working practices, remote learning and e-services. This is particularly important in rural areas where distances and commuting times tend to be longer. All this could promote attractiveness of rural areas.

With changing habits and greater willingness to embrace digital tools, government and private operators might increase investments to realise their potential benefits. In rural areas, the increased connectivity of services can further unlock opportunities for work, synergies and regional integration between rural areas and their surroundings.

Therefore, the COVID-19 outbreak may incentivise the growth of new firms and jobs that offer digital solutions and connect cities and rural areas in a more integrated way. Due to the high concentration of jobs in large urban areas, the use of remote distributed networks could increase the linkages between rural and urban areas. This concept also reflects an ongoing shift in working methods – from the traditional office based workers, to more flexible methods including working at home options, working in different and multiple time zones and nomadic workers (remote workers traveling around different locations).

Another opportunity could be related to changes in social and policy preferences towards services of proximity, greater local consumption and recovery of strategic industries:

There may be a shift in buying habits to favour local goods and tourism sites, as well as production from small local businesses and primary producers. For example, in terms of tourism, overcrowded destinations might see high reductions in tourism flows, while smaller rural destinations may become more popular. The Veneto region (Italy) for example, wants to leverage lesser-known UNESCO heritage sites to shift volumes from Venice to different attractions as part of its recovery plan,14

In some OECD countries, discussions about reshoring and repatriation of strategic industries that were once delocalised (i.e. raw materials) can reactivate rural economies as a host of those industries.

These changes could also favour the transition towards a zero carbon economy. The positive effect of lockdown measures on pollution and CO2 emissions levels can lead to increased social demands for policies to support green and sustainable growth. The recovery process should accelerate the transition to a zero carbon economy by offering sustainable development paths for rural communities, especially those relying on extractive economic activities.

Indeed, rural areas are crucial for the environmental and energy transition in at least two ways:

First, rural economic sectors, such as agriculture, mining and forestry, are important emitters of greenhouse gasses. Reducing emissions in these sectors to avoid the worst impacts of climate change and safeguard biodiversity, while remaining economically viable, will be a key priority in the coming years.

Second, rural areas comprise the vast majority of the land, water and other natural resources, which are fundamental to absorbing CO2, providing eco-system services and safeguarding biodiversity. Supporting countries in developing pathways for climate conscious rural economic development will be key to the recovery of COVID-19.

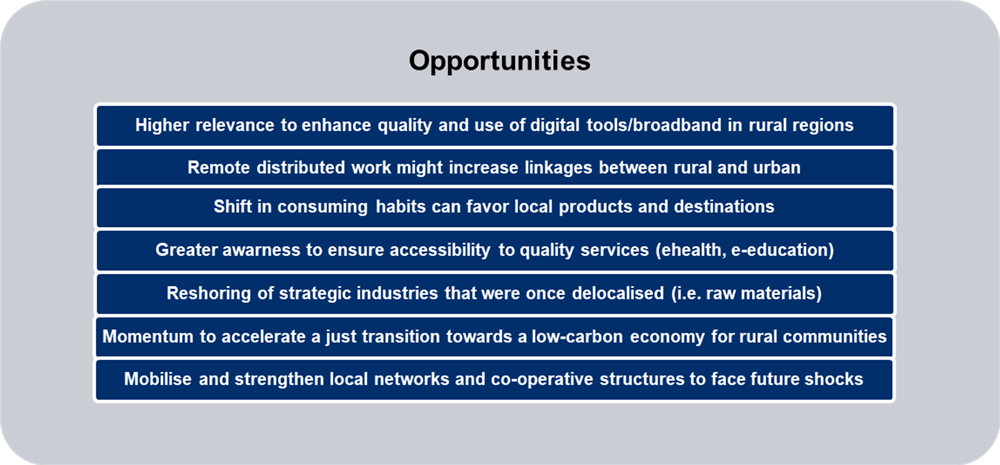

Finally, this crisis offers rural communities an opportunity to mobilise and strengthen their local networks and co-operative structures to face the economic shock. Rural areas tend to benefit from tight community networks able to self-organise to adapt to structural changes. Local initiatives that emerged temporarily to address the immediate economic and social effects of the pandemic (i.e. community fleets transporting medical workers and elderly population) can be useful mechanisms to promote well-being and cohesion in rural communities in the long term. Figure 1 summarises the main opportunities for rural areas emerging from the COVID-19 crisis.

Source: Own elaboration

Preparing for the challenges ahead

The first immediate challenge concerns how to provide essential medical services and testing facilities to rural citizens, especially given the higher share of vulnerable population groups in rural areas, especially elderly and Indigenous populations.

Countries and sub-national governments will need to implement innovative solutions (e.g. mobile medical services) to provide health services to elderly population. Rural areas must also carefully track possible medical and care staff shortages, and plan accordingly. This is particularly critical given the higher proportion of elderly population requiring in-person care services. Some measures are currently being implemented as described in the following section.

There is also concern about the capacity of rural areas to implement current national emergency measures (e.g. areas with quarantine), given their lower administrative capacity (e.g. staffing).

Furthermore, across different countries, a number of urban dwellers have moved away from cities to spend the lockdown in secondary houses, or with their families in rural regions. This movement of people increases the risk of spreading the virus to lower density areas. It could also increase pressures on public health services designed for lower numbers of inhabitants.

Scattered information also affects the preparedness and reaction capacity of rural regions, especially in remote ones. However, some local governments are requesting a better flow of information from the situation in neighbouring regions or in the main cities to prepare health care responses and learn from other rural areas.15

Short-term responses during the COVID-19 crisis have focused on emergency measures to improve health and access to medical services and to maintain basic services in rural areas. These have shed light of the high vulnerability some rural communities face. The stark inequality within countries call for measure that can improve the resilience of vulnerable rural communities to current and future shocks. Measures that can accelerate digitalisation and provide essential services in innovative ways should be at the forefront of policy priorities. In addition to these, other relevant measures to leverage some of the opportunities include:

Speed up investments in digital infrastructure and supporting eco-system to increase the uptake of digital tools in rural areas.

Encourage the uptake of remote services by better adapting national rules to the specificities of rural communities, training of teachers and health care professionals to adopt remote forms of service delivery.

Provide financial and technical assistance to support community-based and social innovation projects that aim at protecting the most vulnerable citizens in rural areas, including the elderly and migrants.

Include sustainability criteria in COVID-19 recovery actions so that they also contribute to long-term resilience by addressing climate change and ecological transition.

Support the resilience of rural communities by enhancing social solidarity networks that meet the basic living standards of the vulnerable citizens in the rural areas.

Indigenous communities residing in rural areas face particular challenges. There are approximately 39 million Indigenous peoples across 13 OECD countries16. Countries that work closely with the OECD, also have significant Indigenous populations (e.g. Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Indonesia and Peru). Indigenous peoples are nearly three times as likely to be living in extreme poverty, making it more difficult to sustain themselves when unable to work.17 Indigenous peoples are also more concentrated in rural areas than non-Indigenous populations.18 Many Indigenous communities experience overcrowded and multi-generational housing, poorer health outcomes, with limited access to health services and infrastructure. All these factors exacerbate the risk of contracting COVID-19 especially in remote communities. Research from the US suggest that the rate of new COVID-19 cases per 1,000 people is four times higher on Indian reservations than in other parts of the US.19 Indigenous SME’s also have a tougher time (relative to non-Indigenous) accessing the loans they might need to survive the lockdown.

Policy responses such as travel restrictions to Indigenous lands, which often time are Indigenous-led and agreed, as well as the provision of information in Indigenous languages are important to keep communities safe and Indigenous cultures alive. Yet, policies must also ensure requisite supplies of food and essential items and to compensate for loss of income, for instance Indigenous businesses reliant on tourism. While some countries are providing targeted support to Indigenous peoples and their businesses, other are lagging behind. Particularly alarming is the situation for Indigenous peoples in countries where their rights are inadequately protected, for instance in cases where illegal miners and loggers are infringing on traditional lands, increasing the risk of infections and reducing the long term economic development opportunities of their communities.

In developing responses, Indigenous peoples should be partners in contributing to solutions addressing the consequences of the pandemic, while also strengthening communities’ resilience by putting their traditional governance knowledge for protecting biodiversity as well as their own health and food systems to use. To this end, the design of policy and programmes needs account for the specific needs and requirements of Indigenous populations and account for their views. With regards to regional development, this also includes promoting local data collection on the impact of COVID-19 as well as strengthening local economies through facilitating supply- chain management, ensuring access to markets, and support for Indigenous entrepreneurs.20

How are OECD countries responding

Confinement and ongoing de-confinement measures have brought new challenges to citizens and firms across the OECD. Beyond economy-wide measures, national, regional and local governments are also rolling out a number of measures targeting people, firms and communities in rural areas. In parallel, bottom-up initiatives involving civil society and voluntary support groups have emerged to support rural communities coping with the new challenge brought by the COVID-19 pandemic.

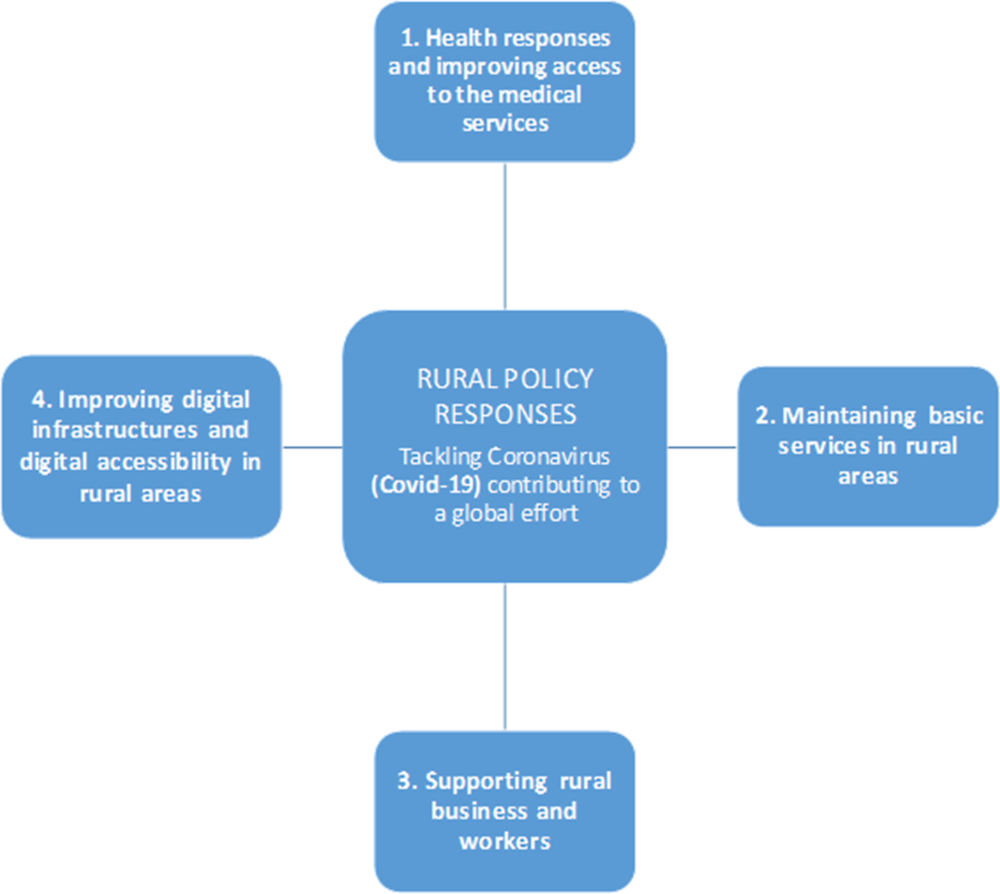

This section summarises actions and initiatives in four broad areas:

Health responses and improving access to the medical services,

Maintaining basic services in rural areas,

Supporting rural business and workers, and

Improving digital infrastructures and digital accessibility in rural areas.

The first two are short-term emergency response measures to mitigate the effects of COVID-19, while the last two are measures that can transform rural economies and communities.

Source: Own elaboration

Health responses and improving access to the medical services

The effects of the pandemic have been quite asymmetric within countries, as some regions and communities have experienced higher rates of exposure to COVID-19. All things equal, more densely populated areas with a high concentration of population have a higher risk of infection than lower-density areas. Despite the lower risk, a number of low density and remote areas experienced pockets of infection in high concentration. For example, rural counties in the United States with large tourist and recreation economies have infection rates that are more than three times higher than for rural counties with other kinds of economies.21

Providing sufficient health responses has been at the forefront of national pandemic strategies and aligned with confinement measures. Medical responses to the virus have been asymmetric, largely due to the concentration of health facilities across territories, with a higher availability of services in more populated regions. In addition, access to medical equipment in remote places is more limited than in the cities, and there tends to be longer delivery times due to greater distances from economic centres and insufficiently developed infrastructure. Several countries have mobilised health workers in different ways to ensure responses to more remote territories. Initiatives range from making health services more accessible in remote places and delivering medical equipment, to information and self-assessment tools for citizens in remote areas, or alternatively bringing rural citizens closer to health services.

Joint responses between national, regional and local levels to COVID-19 have been essential to improve the provision of services for rural areas. A number of voluntary bottom-up initiatives involving co-operatives, businesses and civil organisations have emerged to help temporarily providing health products and services linked to citizen’s needs.

Initiatives to deliver and make available medical equipment

Countries are using open sources to produce medical material

The European Union developed a platform containing a growing list of open source software and hardware solutions to assist medical staff, public administrations, businesses and citizens in their daily activities.22

In Mexico, a platform of about 300 professionals from different fields continue to unite to address the COVID-19 pandemic. It began by joining their efforts to create and donate 3D-printed medical devices to different local hospitals in the country. The platform has facilitated the donation of medical equipment, such as masks and respirators, to a large number of hospitals and have collected in-kind and monetary donations to supply needs of local hospitals throughout the country.23.

Community responses have initiated bottom-up initiatives in vulnerable rural communities aiming to make medical equipment available

In France, the agricultural co-operatives of the French Vexin (northwest Île-de-France) aided caregivers by delivering their reserves of masks and protective equipment to the hospital of Gisors.24

In Spain, a community of 11 villages and about 12 000 inhabitants took a number of notable initiatives, including producing masks and creating of a common household aid fund for the most vulnerable in the community.25

In Brescia, Italy, a hospital with many COVID-19 patients needed ventilators. They were out of stock of breathing valves and suppliers were not able to meet the sudden increased demand. Thanks to a Brescia-based engineering company, they were able to use 3D printing to meet the hospital’s demands and save patients’ lives.26

Upgrading health delivery systems and mobilising local networks

Solutions to upgrade or make medical systems more accessible in rural areas

Korea has provided on-demand services in locations where physical facilities are unavailable, as well as improved medical services to all people regardless of location. The Korean government plans to transform medium-sized regional hospitals into first-class medical institutions that can treat all kinds of diseases, and to increase the number of doctors and nurses in those facilities. The government will allocate 102.6 billion won (USD 88.5 million) to support rural hospitals by 2020.

In the United States, the CARES Act assigned USD 200 million to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for telehealth purposes. The programme seeks to assist eligible health care providers in acquiring telecommunications services, information services, and devices required to deliver critical care services, including treatment for COVID-19 and other health conditions during the pandemic.

Digital solutions created to disseminate information on the pandemic and help health self-assessments

Croatia developed an application to all Croatian smart phone users called Andrija. The application advises people how to diagnose and manage suspected COVID-19 infections and provides users with personalised health advice and guidance.27 This tool is of special relevance for citizens living in places with remote access to health services.

Canada also developed an application “Canada COVID-19 app” to help Canadians track symptoms, receive the latest updates and access trusted resources.28 The application, which allows symptoms to be recorded, is updated as the guidelines evolve to ensure that individuals receive the most recent recommendations. The tracker records results anonymously to help researchers identify how quickly symptoms are spreading and better prepare local health workers for new cases.

The United Kingdom developed an application, the C-19 COVID Symptom Tracker, designed to bring together information that could be useful to medical professionals to better plan their responses. This tool provides support to the deployment of resources and research of the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), and it is especially relevant in rural areas with low accessibility to medical services.29

Mobilising local networks of health care workers and pharmacists

Local network responses and volunteer programmes have emerged to help rural communities face the effects of COVID-19

France has implemented policies on public awareness and resilience to address the emergency in remote rural areas. As an example, the network of Millevaches30 brings together 15 practitioners, pharmacists, physiotherapists, etc., preparing to deal with the pandemic from remote rural regions to hospitals with greater capacity to provide health services.

Spain has set up a free phone line, where expert therapists are available to provide support and initial psychological care to people struggling to manage their mental health during the quarantine. In the Basque Country region, a programme relying on volunteers and the network of pharmacies provides a service to the elderly population with chronic diseases and living alone, ensuring they will not have to go to the pharmacy and thus avoid coronavirus exposure.31

Croatia developed “Call for Health” – a project by the Croatian Medical Chamber and the Croatian Red Cross designed to provide medical advice and free drug delivery to immobile and chronic patients. Any patient in self-isolation or treatment in isolation can use telephone counselling and home medication delivery during the COVID-19 epidemic.32

Initiatives to maintain basic services in rural areas

Lockdown measures to mitigate the spread of the virus have severely affected some rural communities. Against this backdrop, government and support groups have implemented a number of emergency measures to maintain basic services for citizens in rural communities. Maintaining and providing services in rural areas with lower density is more challenging than in urban areas due to greater distances between pockets of economic activity and higher unit costs. These measures range from securing food availability in rural areas, assisting elderly and solidarity initiatives, providing emergency aid and maintaining essential services.

Securing food availability and assisting elderly

Networks of local citizens/producers to deliver food and basic products

Lithuania has developed StiprūsKartu (StrongTogether) 33 – a National Volunteer Support Co-ordination Centre, which co-ordinates those who can provide assistance and those who need assistance during quarantine.

In Spain, the network Guztion Artean (Among All) promoted by the Basque Government to channel volunteer-supported solidarity initiatives to perform strictly necessary and basic tasks for asymptomatic people who cannot leave home, specifically to people over 70 years of age and/or dependents or people in other vulnerable situations.34

In Italy, some cooperatives are offering free grocery deliveries to citizens over 65-years. The Famiglia Cooperativa Valle di Ledro and the Alimentari Ribaga Self Service are two examples of volunteers, delivering groceries for the elderly. 35

Government and community responses to ensure food accessibility

The United States announced a collaboration with associations and private companies to deliver nearly one million meals a week to students in a limited number of rural schools closed due to COVID-19. 36

In Canada, small municipalities offer to deliver food boxes by volunteers from the Food Banks to people who are unable or unwilling to leave their homes. 37

Producing and promoting local food

In Scotland, UK, in a region northwest of Edinburgh (Forth Valley), a food and drink business network is being launched to promote the area’s rich local larder. By choosing to make local purchases, the community is supporting the local economy by strengthening the local food supply chain.38

In the United States, the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development’s (USDA) Local Food Directory Update and Registration site for retail and wholesale food outlets is a free-of-charge service that assists farmers in advertising their business and contacting buyers. 39

Emergency aid and maintaining essential basic services

Provision of grant payments to rural residents

In the United States, USDA developed numerous actions to help rural housing providers and protect residents. Immediate Rural Development Assistance Tenant Vouchers were developed for Multiple Family Residents Payment Assistance. In addition, provisions were established for direct and guaranteed multi-family vouchers through the specialised Rural Development Voucher Program Office. 40

Reconnection of basic services

In Romania, rural communities are vulnerable to essential services price increases. As of 29 March 2020, the price of electricity and heating, natural gas, water, sanitation and fuels cannot be increased. In contrast, they can be reduced in line with demand and supply. 41

Several European Union Member States have established measures to ensure that services cannot be suspended in the event of non-payment. These include drinking water, sewage, electricity, piped gas and the telecommunications system. For example, Spain has banned the cutting off of basic services as part of a programme to provide EUR 600 million to regions and municipalities to ensure the provision of basic services42, and France approved a similar set of measures.43

In Chile, companies that are providing basic household services may not cut or suspend their provision or continuity due to non-payment by users. Users’ debts will be prorated on the accounts for the 12 months following the end of confinement. 44

Supporting rural business

Rural economies are particularly vulnerable to economic shocks due to their less diversified economic base and greater dependency on tradable activities, which tend to suffer during economic shocks. The current shock, driven by containment and lockdown measures, is halting economic activity and affecting the service economy. Without further support, one-third of SMEs are at risk of going out of business within one month, and up to 50% within three months.45 Many countries have put in place a wide range of policies to help SMEs46, including those targeted for rural SMEs. There are measures to support agro-food activities, forestry, mining tourism and Indigenous communities.

Support for rural businesses and SMEs

Support rural businesses and communities by providing them access to capital

The Canadian government provided CAD 287 million through the Community Futures Network. This is a non-profit network across Canada that provides small business services to people living in rural communities. Each of the 267 offices offers small business loans, tools, training and events for people who want to start, expand a franchise or sell a business.47 New funding allocated to the Community Futures Network as part of the COVID-19 response will be used to provide rural SMEs with interest-free, partially forgivable loans of up to CAD 40 000 to help them meet their fixed operating costs through the crisis.

In Poland, a newly adopted Anti-Crisis Shield stipulates the availability of loans for microenterprises recognising the great relevance of SMEs for rural areas. The total estimated value of loans available for businesses will amount to approximately PLN 9.6 billion, of which up to PLN 8.7 billion may be forgiven. In addition, relief on repayment of loans has been granted under the “Start-up support” loan programme.48

The United States government announced a USD 39 billion package targeting the regions most affected by the coronavirus crisis including rural ones. This package includes emergency funding for small businesses and other stimulus measures, as well as those businesses with incomes below USD 78,000 loan guarantees, to ensure that they can access credit easily and cheaply. Commercial banks and national savings banks will also allow the renewal of loans for small businesses that cannot pay on time.49

The European Commission proposed a European agricultural fund that grant loans or guarantees on favourable terms and be more flexible and simple to promote rural development. Aligned actions to cushion the impact of the pandemic such as very low interest rates or favourable payment schedules to cover operating costs of up to EUR 200,000.50

Measures to support primary sectors

Grant private storage aid for dairy and meat products

The European Union announced additional exceptional measures to further support the agricultural and food markets most affected by the current crisis by granting aid for private storage of dairy and meat products in particular, which will result in a decrease in the supply available on the market and will restore the balance of the market in the long term.51

Establishment of mechanisms to stabilise food prices, support farmers and ensure food security

Korea and the United Kingdom support farmers in ensuring food security by protecting access to primary sector inputs (fertilisers, pesticides), covering the costs of marketing and logistics for agricultural product exporters and supporting the operation of restaurants and food service providers.52

The European Union announced a new set of measures to support the agro-food sector, including flexible financial instruments or the reallocation of funds. Farmers and other beneficiaries of rural development will be able to benefit from loans or guarantees to cover operational costs of up to EUR 200 000 on favourable terms. Furthermore, EU countries can allocate the money still available in their rural development programmes (RDPs) to finance relevant crisis actions.41

India is ensuring access to credit for farmers and providing new employment opportunities for tribal groups. The public agricultural and rural credit agency (NABARD) will also provide additional refinancing support for rural bank crop lending requirements, targeting small and marginal farmers. It will provide concessional loans to farmers through credit cards and make available employment opportunities for afforestation and plantation work to those in need. 53

In Czech Republic, the government released CZK 3.3 billion for the 2020 Rural Development Program. This funding should help entrepreneurs in agriculture, food and forestry while fighting the coronavirus crisis.54

Measures for tourism, mining and indigenous communities

Support measures for tourism

Several countries have dedicated financial assistance and promotional campaigns supported by the allocation of funds dedicated to the tourism sector. Subsidies for workers and companies in the sector will allow the revival of the sector with a constant focus on the promotion of domestic tourism. These measures will be especially relevant for a number of rural regions specialised in tourism.55

The Australian Government introduced a Stimulus Package, which includes assistance for severely affected regions as one of four main pillars. This involves AUD 1 billion to support those sectors, regions and communities that have been disproportionately affected by the economic impacts of the coronavirus, including tourism. The assistance measure include waiving fees and charges for tourism businesses that operate in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park and Commonwealth National Parks, and assistance to help businesses identify alternative export markets or supply chains.56

In Italy, a number of measures have been undertaken to support tourism sector. Those more closely related with rural areas include extraordinary allowances for tourism and culture workers, vouchers for hotels to refund for trips and tourist packages cancelled, and a special compensation of EUR 600 in March to tourism seasonal workers who lost their job as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. 57

In Iceland, the government suspended the payment and collection of the tax on overnight stays (bed-night tax) until 31 December 2021 and launch a package of ISK 1.5 billion worth of travel vouchers to provide Icelandic residents over 18 years of age to spend domestically.58

Support measures for mining and extractives industries

In Canada, the Mining Association of Canada (MAC) has brought 18 national and regional industry associations and partners together to donate a total of CAD 36,000 to food banks across the country to bolster support for Canadian families in need. Young Mining Professionals Toronto has also launched Mining Cares, a mining industry initiative designed to consolidate its participants to make a meaningful difference in the global fight against COVID‑19.59

The South Australian State Government in Australia has cut all exploration and licence fees in the minerals sector to soften the impact to the industry during the region’s COVID-19 containment procedures. It includes an immediate deferral of mineral exploration licence fees due in the next six months and a 12-month waiver of committed expenditure for all mineral exploration licence holders. Furthermore, different Australian mining firms have announced financial packages to help rural communities. For instance, the BHP Group Limited has launched plans to establish an AUD 50 million fund to support communities in the regions of Australia where it operates, with investment to be directed into critical health services and resilience building.60

In the state of Tennessee, United States, medical centres are providing special attention to COVID-19 related symptoms for miners. Specific medical protocols have been established during the pandemic due to the fragility of these workers. In Lafollette, Tennessee, the Black Lung Clinic monitors and treats patients suffering from the incurable and fatal respiratory disease caused by exposure to coal dust. In addition, for decades there have been mutually supportive networks among local rural communities connected to each other. Their usual forms of resource-sharing assistance are being reinforced during the pandemic.61

Support measures for Indigenous peoples

The Government of Canada will provide up to around CAD 307 million in short-term, interest-free loans and non-repayable contributions for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis businesses. This measure is part of the Government of Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan.62 Crucial to the this programme is that the financial support is channelled through Aboriginal Financial Institutions (AFI) and administered by the National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association, as well as the Métis Capital Corporations in partnership with Indigenous Services Canada. This ensures better take-up as AFIs are particularly well integrated in Indigenous communities and the go-to source for indigenous businesses for loans.

Australia is responding with several measures and programmes targeted for Indigenous communities.63 Most importantly, it has decided to restrict movement of people to remote communities to slow the spread of COVID-19 and protect vulnerable people in these areas. Importantly, this decision was based on the advice from Indigenous leaders who were consulted in developing responses. Further, information on COVID-19 is available in various Indigenous languages to ensure public information on prevention and access to health reaches all Australians. The government has made AUD 123 million available to support Indigenous businesses and communities in their response to COVID-19. In addition to providing grants, the government also provides specialist advice to help businesses address immediate problems. Furthermore, the government is supporting a variety of agencies to look at how local Indigenous workers can help address workforce shortages, particularly in regional and remote areas where the usual workforce is unavailable.

Improving digital infrastructures and digital accessibility in rural areas

Confinement measures, aimed at flattening the curve of infection rates through self-isolation and reduced mobility, have halted the delivery of some services, notably schooling. Workers and children across the OECD had to work or study remotely using digital means. However, their ability to do so has been varying, with pockets of workers and students unable to telework or participate in distance-learning due to a lack of digital infrastructure and digital services. The gap in digital infrastructure before the current crisis between rural regions and urban was substantial. While 85% of urban households had access to 30 Mbps of broadband, in rural regions only 56% of rural households had access.64

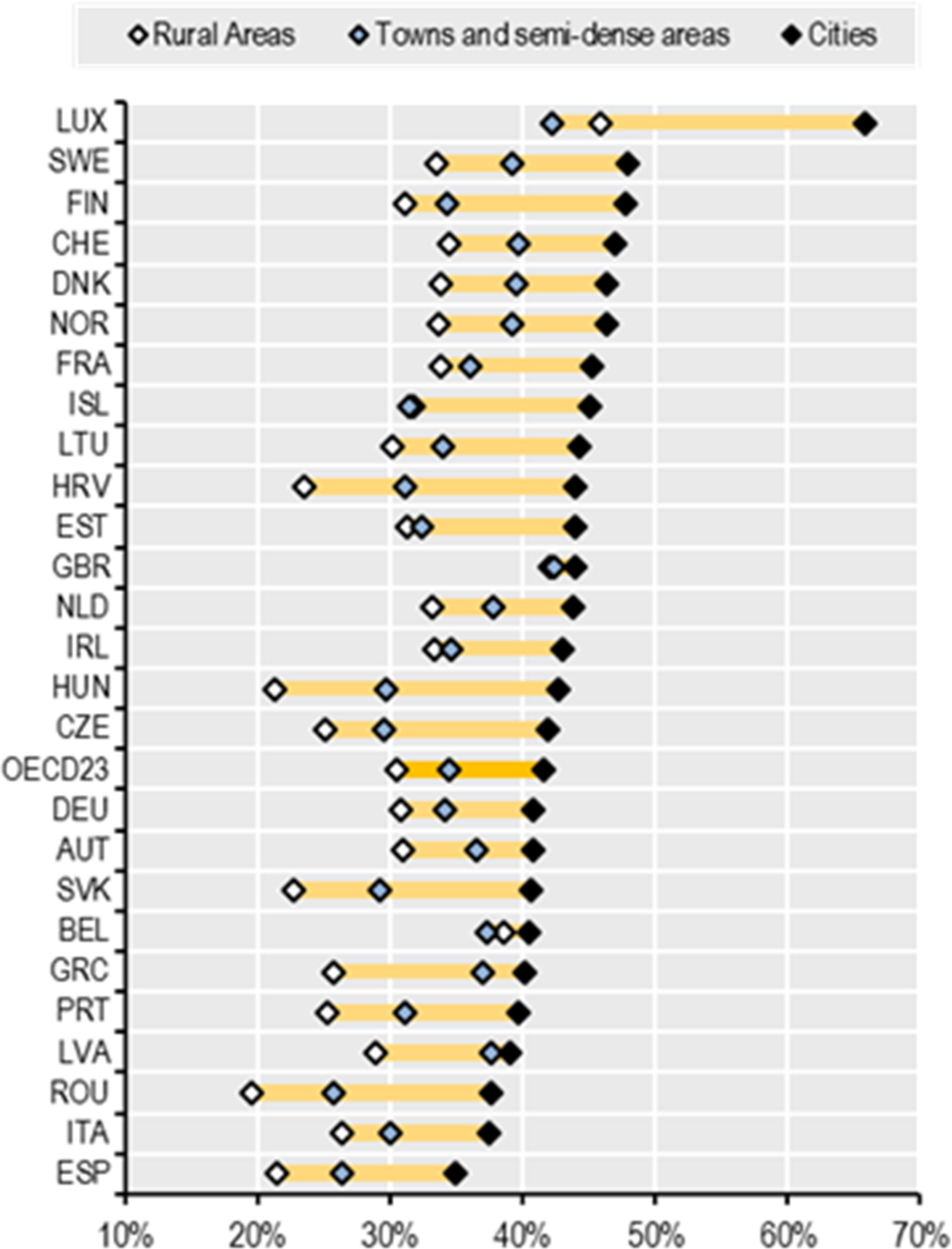

A forthcoming OECD policy note on remote working65, shows a consistent difference between cites and other less densely populated areas. Using the Degree of Urbanisation66 for European countries to distinguish locations along the urban-rural continuum (Figure 3), the ability to work remotely is higher in cities compared to towns and semi-dense areas, while it is the lowest in rural areas. More specifically, cities have 13 percentage points higher shares of jobs that are amenable to remote work compared to rural areas.

Note: The number of jobs in each country or region that can be done remotely as the percentage of total jobs. Information on the degree of urbanisation is only available for 28 EU countries.

Source: Figure 1 in forthcoming OECD policy note on Capacity for remote working can affect lockdown costs differently across places.

Across the OECD, response measures during the COVID-19 crisis to close the digital gap, have aimed at improving current and future digital infrastructures in rural regions, their ecosystems as well as the accessibly of rural citizens to digital services. Better digital infrastructures in rural areas – essential to rural firms and better delivery of services – can also help provide accurate, useful and current information to citizens living in remote areas and deliver better government e-services to rural citizens, enhancing citizen participation.

Broadband and cloud services

Implementation of a Broadband Fund to support universal access to internet, enhance distance-learning and healthcare E-services

The Unites States’ Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act allocated an additional USD 100 million to the RUS Rural Connect Pilot Program (“ReConnect”). This programme provides funding to entities seeking to deploy broadband in rural areas. The CARES Act also appropriated USD 25 million for the USDA’s Distance Learning and Telemedicine Program. This programme helps rural communities by funding connectivity to combat the effects of remoteness and low population density.67

Poland has an investment plan of EUR 6.6 billion to reinforce public investment expenditure including a specific fund for the deployment of broadband networks. The fund consists of national resources, independent of EU support.68

Digital services to small and medium-sized enterprises

The government of Austria created “Digital Team Austria’’, a group of companies that will offer services including online meetings, digital collaboration, cyber security, and/or Internet access free of charge for at least three months.69

Strengthening Digital Infrastructure with Focus on 5G Strategy Industries

Korea has allocated KRW 684,788 million for wider 5G wireless network coverage, development of next generation smartphone models, and easing regulations to speed up innovation to foster the transition to new telecommunication systems. This programme is part of a package of measures that will generate an economic stimulus in a post-COVID-19 phase by relying heavily on AI and wireless telecommunication technology.70

Access to education

Quality educational platforms through dedicated educational timeslots on radio and TV

The strategy in Colombia of Aprende en Casa (Learn at Home) gives flexible pedagogical tools to the educational community (parents, students, counsellors, directors, etc.) to guarantee student education at home in response to COVID-19 confinement measures. Aprende en Casa includes four communication channels: television, radio, digital and physical and is broadcast three days a week.71

In Croatia, students in primary and secondary schools are taking classes taught by the public broadcasting service after classroom learning was halted by the outbreak of COVID-19. The Croatian language-learning programme has been broadcast daily since mid-March 2020 on Croatian Radio Television (HRT) and the classes are also available on YouTube immediately after the television broadcast.72

Ensuring online education infrastructure for nationwide schools

In Korea, the Ministry of Education has implemented an ambitious plan to improve the wireless internet infrastructure in some rural schools, and the programme will spend about WON 1.5 billion (USD 1.2 million). In this way, some of the obstacles inherent in the challenge of teaching at a distance are addressed. In addition, 332 000 smart devices have been provided to low-income households free of charge, and low-income families have subsidised internet connections. 73

The Ministry of Digitisation in Poland has launched the Internet for Education initiative, offering 2 000 Polish teachers free fibre-optic internet to provide quality lectures to their students. Govtech Polska and the Digital Poland Foundation also support the campaign. The offer includes free fibre-optic internet with a speed of up to 150Mbps for six months.74

In Slovakia, the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport launched a website to provide teachers, school management, parents and students with up-to-date information on education matters during school closures. This website also contains various publicly available educational resources created by the state as well as other civil society actors including teachers and NGOs.75

Governance

More efficient government and adoption of e-government platforms

The United Kingdom has implemented the COVID-19 helpline open to all businesses and self-employed individuals with financial difficulties and outstanding tax obligations reachable via web-chat or phone.76 The aim is to provide financial assistance, allowing businesses and self-employed individuals to pay off their debt in instalments over a period of time with the possibility of delaying the first payment by up to three months.

In Greece, the government has published a website where many bureaucratic procedures can be completed online that were previously only possible in person. The platform offers access to 14 ministries, 32 bodies and organisations, and three independent authorities for a total of 507 services organised into 11 categories.77

Horizontal knowledge sharing within country governments

In Canada, a catalogue of open source digital solutions are part of the COVID-19 national government response, with free training and support offered to other levels of government in Canada to reuse.78

The Institute of Health Policies of the Slovak Republic (IHPSR) provides inputs for policymakers and responders handling the COVID-19 crisis. Their epidemiological research reports are updated and available online under open license.79

Citizens engagement in the decision-making

In April 2020, the French parliament launched a platform to collect citizens’ opinion on the post-COVID-19 world. Questions focused on health, work, consumption, solidarity, education, democracy, local initiatives, Europe in the world, the evaluation of common goods, financing and distribution of resources.80

Latvia held a virtual hackathon ''HackForce''.81 The organisers were volunteers from the start-up community and the goal was to find answers to the challenges posed by the coronavirus crisis by deploying volunteer resources at the community level. At the hackathon, with the assistance of mentors, participants generated ideas with a focus on four areas: (i) medicine and health; (ii) solutions to the coronavirus crisis (social distance, information flow, volunteering and other assistance); (iii ) education; and (iv) projects to support the economy and businesses.

In Spain, an initiative called “Hackaton Rural”, presented at an online event, brought together various stakeholders who shared their initiatives to address the economic consequences of COVID-19 in rural regions, contributing ideas seeking to find solutions in rural Spain.82

Contact

Enrique GARCILAZO (✉ JoseEnrique.GARCILAZO@oecd.org)

Andres SANABRIA (✉ Andres.SANABRIA@oecd.org)

Lisanne RADERSCHALL (✉ Lisanne.RADERSCHALL@oecd.org)

Fernando RIAZA FERNANDEZ (✉ Fernando.RIAZAFERNANDEZ@oecd.org)

Ana MORENO MONROY (✉ Ana.MORENOMONROY@oecd.org)

Gareth HITCHINGS (✉ Gareth.HITCHINGS@oecd.org)

Michelle MARSHALIAN (✉ Michelle.MARSHALIAN@oecd.org)

Notes

Baker, Scott R., et al. How does household spending respond to an epidemic? Consumption during the 2020 covid-19 pandemic. No. w26949. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020, https://www.nber.org/papers/w26949.pdf

Indigenous peoples are defined by the United Nations as those who inhabited a country prior to colonisation, and who self-identify as such due to descent from these peoples, and belonging to social, cultural or political institutions that govern them. They have unique assets and knowledge that address global challenges such as environmental sustainability and that contribute to stronger regional and national economies.

https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/s0614-obesity-rates.html. Additional research on obesity trends between urban and rural areas available in: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1171-x

Research note developed by Mark Zandi, Chief economist of Moody’s, https://www.economy.com/economicview/analysis/378644/COVID19-A-Fiscal-Stimulus-Plan.

Muro, M., Maxim, R. and J. Whiton “The places a COVID-19 recession will likely hit hardest” March 17, 2020. Brookings Institute, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2020/03/17/the-places-a-covid-19-recession-will-likely-hit-hardest/

Goldberg, Pinelopi (2020). “Policy in the time of coronavirus.” in Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes, eds Richard Baldwin and Beatrice Weder di Mauro. VOX, https://voxeu.org/content/mitigating-covid-economic-crisis-act-fast-and-do-whatever-it-takes

OECD (2020), Tourism Policy Responses, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=124_124984-7uf8nm95se&title=Covid-19_Tourism_Policy_Responses

Australia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Denmark (Greenland), Finland, France (New Caledonia), Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, United States.

https://joinup.ec.europa.eu/collection/digital-response-covid-19/open-source-solutionshttps://joinup.ec.europa.eu/collection/digital-response-covid-19/open-source-solutions

https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/news-events/news/spanish-rural-community-takes-action-against-covid-19_en

https://andrija.ai

https://ca.thrive.health/

https://www.thecourier.co.uk/fp/lifestyle/food-drink/1251142/food-firms-team-up-to-feed-communities/

https://vermontbiz.com/news/2020/april/16/usda-implements-immediate-measures-help-rural-communities

OECD (2020), SMEs Policy Responses, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=119_119680-di6h3qgi4x&title=Covid-19_SME_Policy_Responses

https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=119_119680-di6h3qgi4x&title=Covid-19_SME_Policy_Responses

http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/coronavirus-covid-19-sme-policy-responses-04440101/

More information on policy responses to tourism is available in OECD (2020), Tourism Policy Responses https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=124_124984-7uf8nm95se&title=Covid-19_Tourism_Policy_Responses

OECD (2019), Going Digital: Shaping Policies, Improving Lives, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264312012-en.

Forthcoming OECD Policy note on Capacity for remote working can affect shutdowns’ costs differently across places.

The Degree of Urbanisation is a methodology to classify cities, urban and rural areas for international comparative purposes. The method proposes three types of areas reflecting the urban-rural continuum instead of the traditional urban–rural dichotomy.

www.usp.gv.at

https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/hm-revenue-customs/contact/coronavirus-covid-19-helpline

https://lejourdapres.parlement-ouvert.fr/