Abstract

Regulation is one of the key tools for governments to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and look towards recovery. While the pandemic underscores the need for well-designed, evidence-based regulatory policies, the extraordinary pressures imposed by the pandemic often forced governments to shorten procedures and launch new forms of co-ordination to urgently pass regulatory measures. This can make regulatory policy making more challenging, but also provides opportunities to innovate. This policy brief analyses how Southeast Asian (SEA) countries approached these challenges and opportunities, as well as shares lessons learned and practices between the SEA and OECD communities. It draws upon discussions held in the ASEAN-OECD Good Regulatory Practices Network (GRPN), hosted by Viet Nam (2020) and Brunei Darussalam (2021) and co‑chaired by Malaysia and New Zealand. An ASEAN-wide survey administered by the OECD Secretariat underpins the findings.

Southeast Asian (SEA) countries have been promoting better regulation reforms for several decades, focusing on improving institutions, processes and tools of regulatory policy making. Reforms were mostly to reduce administrative burdens, while governments are increasingly implementing good regulatory practices (GRPs), including regulatory impact assessments (RIAs), stakeholder consultations and ex post reviews. Additional reforms are gaining steam, notably in creating regulatory oversight bodies, improving service delivery through one-stop shops and digital solutions.

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the need for well-designed, evidence-based, co‑ordinated and well-enforced regulatory policy to contain and mitigate the effects of the virus, minimise impacts on citizens and the economy, and support recovery efforts. Due to extraordinary time pressures to swiftly develop policies, OECD and SEA countries alike have shortened procedures and launched new forms of co-ordination to urgently pass crisis-related regulations.

The ASEAN-OECD Good Regulatory Practices Network (GRPN) has met regularly online in 2020-21 to share experiences to support peer learning. Examples shared have included introducing flexibilities around the use of GRPs, relaxed administrative rules, leveraging digital technologies, supporting economic recovery, and preparing government for future crises.

The OECD also surveyed key GRPN contact points to gain a deeper understanding of these initiatives. The following trends and avenues for further research were identified:

- 1.

While regulatory policy systems are complex and spread throughout government, pandemic decision making seemed to be centralised in the centre of government and line ministries/departments supported by ad hoc COVID-19 co-ordination structures. Further investigation should explore the effect on government decision making, which may have led to a preference for community-wide policies, such as for all forms of businesses, over targeted and sectoral approaches.

- 2.

The impact of the pandemic caused changes to existing regulatory requirements, often relaxing or applying them more flexibly, such as by reducing burdens and facilitating compliance. Countries also addressed specific regulatory issues needed to support pandemic responses, such as contact tracing, quarantine rules or restricting movement.

- 3.

Governments need to review regulatory changes to examine what worked and what did not. Special attention should be paid to learning how to apply these lessons to build flexibility and resiliency into the regulatory policy-making system. Data indicates only a moderate commitment to ex post reviews of regulation by SEA countries going forward, which may want to focus on fast-tracked regulations passed during the pandemic.

- 4.

Reviews could also explore ways to design “future proof” regulations to cope with crises, including what to activate when a crisis hits or de-activate once it has eased. Investing in deepening regulatory systems to include international regulatory co-operation, oversight and sectoral applications of better regulation principles (e.g. to trade and investment) are possible ways to support such outcomes.

- 5.

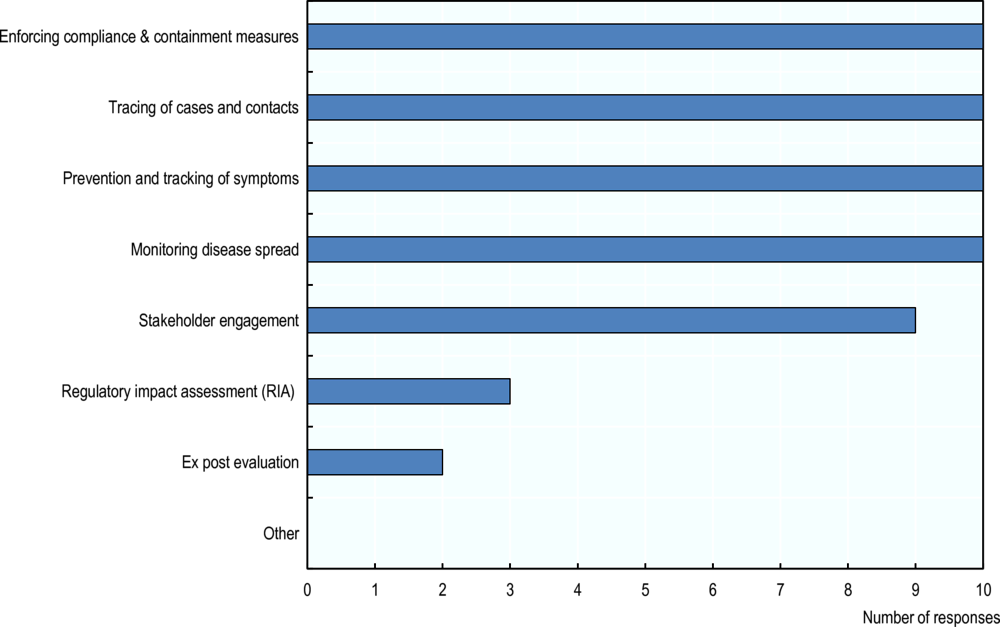

As in the OECD, many SEA countries clearly leveraged digital technologies to adapt quickly and maintain government functions; however, it is unclear what effect this has had on regulatory quality. While respondents did identify that technologies were used broadly to support stakeholder engagement, few respondents noted their use in RIAs or ex post reviews, clearly offering avenues to innovate GRPs.

- 1.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has created an unprecedented global health and economic crisis. The OECD (2021[1]) estimates that the pandemic caused world GDP to fall by 3.4% in 2020, with steep declines of as much as one-fifth of output in some advanced and emerging economies in the first half of 2020 (OECD, 2020[2]). Global trade also experienced a historic collapse, falling by an estimated 8.5% during in 2020 (OECD, 2021[3]). The human toll has been massive: as of early October 2021, the WHO (2021[4]) estimates that worldwide cases have exceeded 235 million, resulting in more than 4.8 million deaths. The Southeast Asian (SEA) region accounts for over 43 million cases and nearly 680 000 deaths, though the impact at the country level is heterogeneous with some countries impacted worse than others.

The speed at which the public health and resulting economic crises unfolded has placed immense pressures on governments to react quickly and effectively to protect citizens and businesses. As one of the key policy levers of government, regulation was at the centre of this effort – requiring regulatory decisions at nearly every stage and policy area. At the start of the pandemic, governments passed emergency legislation, implemented lockdowns and containment measures, adapted their governance structures, and enacted other regulatory changes to urgently respond to challenges imposed by the crisis. As subsequent waves of the pandemic have continued in 2021, a return of many of these measures have had lasting effects on the daily life of citizens as governments continue to try and change the behaviour of the public to control and rollback the spread of the virus while keeping their economies afloat (OECD, 2020[5]).

While regulation is central to the pandemic response, maintaining regulatory discipline has been challenging. The OECD (2012[6]) Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance sets out a robust, internationally-recognised normative framework for better regulation. It encourages policy makers to implement systemic reforms to deliver regulations that meet public policy objectives and have positive impacts via the use of ex ante and ex post analysis, stakeholder engagement, risk-based approaches, multi-level co-ordination and strong institutional support. However, due to the COVID-19 crisis, governments around the world have been under extraordinary time pressures to swiftly develop policy responses and have often shortened administrative procedures and adopted new forms of co-ordination to urgently pass a range of crisis-related regulations (OECD, 2020[7]).

To support countries in responding effectively to the crisis, the OECD brought together its committees and networks to share challenges and opportunities they have faced. In Southeast Asia (SEA)1, the ASEAN-OECD Good Regulatory Practices Network (GRPN)2 has met virtually five times to date during the pandemic, focusing on the changes to regulatory policy making associated with governments’ responses to the pandemic and how better regulation reforms can support recovery.

This policy brief3 is a result of these meetings and presents a summary of the regulatory policy making challenges and opportunities for reform facing SEA countries, gathered from the inputs from the GRPN and the survey responses from the majority of SEA countries4. The first section presents a background on better regulation in the OECD and SEA regions, as well as an analysis of how governments have responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. The second section presents the results of the survey of GRPN members, highlighting trends observed.

2. Better regulation in Southeast Asia: Before and after the pandemic

Developing and enforcing laws and regulations is one of the key levers for governments to achieve objectives, alongside tax and spending measures, to deliver better outcomes for citizens and businesses. Regulations have a wide variety of purposes, including to impose technical standards, manage risk and promote the proper functioning of the economy while protecting society. They create “rules of the game” for citizens and businesses to abide and promote the efficient functioning of markets, protect the rights and safety of citizens and the environment, and ensure the delivery of public goods and services. Good regulations create the conditions for economic and social growth, while poorly-designed and cumbersome regulations can stifle it by imposing regulatory burden, resulting in undue costs on businesses and citizens.

Given the vital importance of regulation to the work of governments, countries around the world have been developing approaches and frameworks for “better regulation” for several decades. These have been enshrined in the OECD (2012[6]) Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance.

When functioning properly, institutions, tools and processes of regulatory policy making, summarised as “regulatory governance”, helps support better regulatory decision making across government. As in OECD countries, SEA countries have also been focusing on adopting better regulation reforms for decades. This has been supported at the regional level by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which encourages reforms and produces guidance for its members, such as the ASEAN (2019[8]) Guidelines on Good Regulatory Practices. The ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint 2025 further recognises the importance of good regulatory practices, building upon previous regional declarations such as the Putrajaya Declaration and the Nay Pyi Taw Declaration in 2015 (OECD, 2018[9]). The ASEAN Work Plan on Good Regulatory Practice (2016-2025) also aims to embed GRPs in both national and regional level contexts (OECD, 2018[9]). Furthermore, the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) supports ASEAN with policy-oriented economic research, including in the area of regulation and governance (ERIA, n.d.[10]).

In addition, a focus on better regulation can foster more trust in public institutions, and better democratic governance for all, by demonstrating how government decisions can improve outcomes for everyone. The erosion of trust in public institutions has been a recurring issue for many years (OECD, 2017[11]); (OECD, 2021[12]). OECD research on the determinants of trust in government suggest that perceptions of institutional performance strongly correlate with both trust in government and trust in others, and that perceived government integrity is the strongest determinant of trust in government (Murtin et al., 2018[13]). Better regulation plays a substantial role in building trust, including through providing clear, well-reasoned and evidence-based decisions (OECD, 2021[14]) and focusing on perceptions of fairness by conducting robust stakeholder consultations that invest in hearing and considering the views of citizens and businesses from the onset, treat them with dignity and respect, and ensure they received honest and helpful explanations (OECD, 2017[11]); (Lind and Arndt, 2016[15]). The role of regulatory policy in building trust is particularly important in the context of the pandemic. Resolving the health crisis and the ensuing economic and social predicament involves regulatory decisions at nearly every stage and in nearly every area (OECD, 2020[16]). The current situation makes the need for trusted, evidence-based, internationally co-ordinated and well-enforced regulation particularly acute (OECD, 2020[16]).

This section explores further what better regulation is aligned with OECD normative guidance and practical experience, as well as how SEA countries have adopted associated reforms. It then focuses on the impact of COVID-19 on regulatory policy making in OECD and SEA countries, based on conversations had during the sixth (2020[17]) and seventh (2021[18]) meetings of the ASEAN-OECD Good Regulatory Practices Network (GRPN). The themes and trends discussed in this section are supported by the results of a survey of SEA countries provided in the next section.

What is better regulation?

Better regulation incorporates different perspectives into frameworks to promote the design and delivery of more effective policy. It encourages whole-of-government regulatory strategies, encouraging all institutions involved in regulatory policy making – including better regulation units of the centre of governments,5 ministries/departments, independent regulators, oversight bodies, parliament, and the judiciary – to be aligned in their efforts. This ensures consistency and promotes efficiency in public administration.

One of the main set of tools for doing so are good regulatory practices (GRPs), also known as regulatory management tools, which support policy makers in their efforts to use evidence-based decision making through the policy cycle. These tools include regulatory impact assessments (RIAs), stakeholder engagement, and ex post evaluation. Regulatory delivery is supported through enforcement and inspections, which help to make sure regulations are fit-for-purpose and deliver what they are set to achieve (OECD, 2018[9]). Better regulation also encourages looking internationally to align approaches through international regulatory co-operation, and incorporates innovative approaches as they are developed.

The use of GRPs has been central to the better regulation agenda, often out of the realisation that countries need to control the “stock and flow” of regulations to ensure efficient functioning of markets and appropriate protection for citizens. Stock-management efforts, including administrative burden reduction programmes, are supported by tools like RIAs and stakeholder engagement to manage the speed and quality of new regulations to slowly re-shape the regulatory stock over time.

In recent decades, GRP provisions have increasingly been included in trade agreements to promote the effectiveness and efficiency of regulations. Recent major trade agreements have included dedicated chapters on good regulatory practices, including the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between Canada and the European Union; the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), replacing the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA); and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which involves several SEA governments (Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore and Viet Nam) (Kauffmann and Saffirio, 2021[19]). The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement also contains a chapter on standards, technical regulations and conformity assessment procedures and various sub-sections on regulation.

The OECD supports countries around the world to monitor and improve regulatory policy making, including through data collected on member countries’ use of regulatory policy and GRPs presented in the Regulatory Policy Outlooks (2015[20]); (2018[21]); (2021, forthcoming). Data shows, for example, that even though all OECD had a whole-of-government regulatory policy and entrusted a body with co-ordinating regulatory quality across government by the end of 2017, many countries still had incomplete “life-cycles” of regulations, particularly regarding the later stages of enforcing and reviewing them (OECD, 2018[21]). A lack of effective GRPs weakens regulatory capacity. This is especially true during times of crisis as governments are expected to be agile in decision-making while being inclusive of stakeholders, including citizens, civil society and businesses.

How SEA countries used better regulation before the COVID-19 pandemic

Administrative burden reduction has driven the pursuit of GRPs across SEA as governments seek lower compliance costs and simplified regulations (OECD, 2018[9]). Burden reduction can be accomplished through a variety of ways, including reviewing the stock of existing regulations to determine what should be repealed or amended and offering one-stop shops and e-services for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) to more easily access information and comply with regulations (OECD, 2018[9]). Additionally, governments can reduce administrative burdens by streamlining both the development of regulations and regulatory service delivery across government ministries and agencies to simplify compliance procedures and reduce costs for citizens, businesses, and the state (OECD, 2018[9]).

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, various countries in the SEA region had already introduced and adopted specific laws to support the use of GRPs including: Malaysia (National Policy on the Development and Implementation of Regulations, 2013), Cambodia (Government Decision No. 132, 2016); Indonesia (Law No. 12, 2011); Lao PDR (Law on Making Legislation, 2012); Thailand (Article 77 of the 2017 Constitution); and Viet Nam (Law on Promulgation of Legal Normative Documents, 2008). Indonesia also passed the Omnibus Law on Job Creation (UU 11/2020) in late 2020, which aims to promote job creation through, inter alia, administrative burden reduction and regulatory reforms.

SEA countries have also been investing resources in moving beyond administrative burden reduction and GRP reforms to more advanced regulatory approaches. This has been evident in forums such as the GRPN. In recent years, in response to both demand from GRPN members and examples from SEA countries, the network has covered issues beyond its initial focus on the three GRPs6 to a broader discussion on better regulation around the regulatory policy making cycle, in line with the OECD (2012[6]) Recommendation, and to important sectors for economic regulation in the region. This includes topics related to business registration, one-stop shops, governing in the age of digital technologies, international regulatory co-operation (IRC), SME development, and trade and investment promotion.

This interest has mirrored institutional reforms to regulatory systems at the country level in various SEA countries that are pushing forward various regulatory reforms related to GRPs and beyond. For example, Thailand reformed its Office of the Council of State (OCS) to serve as the regulatory oversight body for the Thai Administration in 2019, in response to the constitutional provision focusing on GRPs noted above. This reform granted powers to the OCS to both encourage the use of GRPs across government via training and capacity building, but also to scrutinise RIAs and consultations and providing their opinion to the Council of State to support decision making (OECD, 2020[22]). Similarly, the Philippines created the Anti Red Tape Authority (ARTA) in 2018, inside the Office of the President, as an oversight body responsible for improving the ease of doing business, service delivery and evaluating RIAs (OECD, 2020[23]). Since 2010, Viet Nam’s Administrative Procedures Control Agency (APCA) in the Office of the Government has been evaluating and simplifying administrative procedures through waves of reforms, beginning with Project 30 in 2007 (OECD, 2011[24]) and continuing with second and third waves throughout the 2010s (APCA, 2020[25]). In Indonesia, the Investment Co-ordinating Board (BKPM) made changes to its former Online Single Submission (OSS) system based on risk level in response to the Omnibus Law on job creation mentioned above (BKPM, 2021[26]). In Malaysia, Futurise was established under the purview of the Ministry of Finance to develop an innovation ecosystem inside the Malaysian government, including undertaking “national regulatory sandboxes” for digital technologies. Better regulation enables governments to respond more effectively to crises. The use of GRPs, even if abridged due to severe time and resource constraints, can strengthen quick government responses to the immediate crisis, while ultimately helping build more resilient risk management systems in the long-term.

The OECD has been analysing policy responses to the pandemic across its policy communities via the OECD COVID-19 Digital Hub.7 A central theme identified through the OECD Regulatory Policy Division’s analysis and webinars hosted through its committees and networks is the importance of regulatory decisions at nearly every stage of the COVID-19 crisis (OECD, 2020[16]).

As explained in OECD (OECD, 2020[27]) by the OECD Health Division, pandemic response requires a package of containment and mitigation policies to address individual and collective behaviour based on four pillars: 1) surveillance and detection; 2) clinical management of cases; 3) prevention of the spread in the community; and 4) maintaining essential services. These four pillars interact and support one another. Either directly or indirectly, regulatory decisions are at the heart of all four of these pillars. As stated in OECD (2020[16]), while such emergency regulations need to be adopted quickly, they still need to be based on trusted, evidence-based, internationally co-ordinated and well-enforced principles of better regulation.

In response to the extraordinary time pressure to swiftly develop such policies, evidence shows that countries are generally using shortened administrative procedures and new forms of co-ordinating structures to urgently pass crisis-related regulations (OECD, 2020[7]). This has included a variety of measures, such as introducing a range of flexibilities around the use of RIAs that either provide exemptions or allow for simplified forms of analysis for temporary measures, or relaxing administrative rules and regulatory enforcement, especially around the provision of essential goods. Governments have also removed legacy regulatory measures identified as preventing potentially life-saving services, testing or accessing personal protective equipment. While demonstrating the agility of government in response to the crisis, OECD (2020[7]) further notes the potential downsides of such approaches and recommends still placing importance on providing evidence-based rationale for emergency regulations. This should be supported with ex post reviews in the future, including sunset clauses and post-implementation reviews, to ensure that the effectiveness and efficiency of the measures is scrutinised and lessons learned.

While the above elements of better regulation focus on the design of regulatory policy, the delivery of regulation is equally important. As the crisis evolved, it became increasingly clear that global trade helped maintain a resilient and robust supply of essential and other goods (Van Assche, 2020[28]). Independent economic regulators are one type of agencies that were responsible for supporting the delivery of such products, focusing primarily on maintaining access to markets for essential services such as water, energy, telecommunications and transportation (OECD, 2020[29]). This included, for instance, ensuring the flow of goods by relaxing standards for transportation of goods, such as the “green lanes” system established in the European Union (European Commission, 2021[30]), or improving trade facilitation, such as through the Authorised Economic Operator programme in Malaysia (JKDM, 2021[31]). Some SEA countries also used reciprocal green lanes to facilitate travel between countries and regions, focused mainly on short-term essential business or official travel. This included Singapore, which instituted green lanes with several countries including Brunei Darussalam, People’s Republic of China, Germany, Indonesia, Malaysia, Japan and Korea (ICA, 2021[32]). Some of these have been suspend in accordance with the epidemiological situation. The crisis demonstrated the essential role of these measures, as they led and took part in a suite of short term emergency measures to ensure the operation of markets, continuity of service, mitigating the effects on the increasing number of vulnerable customers and maintaining the financial security of network operators. Phasing out these measures will be key to maintaining regulatory predictability and will require ex post reviews.

Another key actor in regulatory delivery are enforcement and inspection agencies, who are responsible for maintaining the quality and access to key production and delivery elements such as food or essential goods such as personal protective equipment (OECD, 2020[5]).They were also key players in fostering compliance with mitigation measures through targeted, proportionate enforcement and transparent communication with businesses who had to maintain operation during the crisis. This required removing disproportionate or non-risk based administrative barriers to achieve sustained compliance (for more information, see OECD (2018[33]) work on enforcement and inspections).

Finally, regulatory innovations were needed to support agile responses. Domestically, governments quickly leveraged digital technologies to monitor the spread of the disease, track and trace individuals, provide opportunities for self-assessment, and support monitoring and containment measures, including quarantines (Amaral, Vranic and Lal Das, 2020[34]). Governments also turned to behavioural science to support efforts to encourage rapid and wide spread behaviour change, key to any regulatory measure but a challenging task considering difficult barriers and biases embedded within behaviour change (OECD, 2020[35])8. Internationally, the pandemic highlighted the need for collective action across policy fronts; however, evidence shows that many countries’ initial regulatory policy responses to the pandemic were not sufficiently co-ordinated internationally, resulting in ineffective policy interventions, delays (and even shortages) in access to essential goods and administrative efficiency losses (OECD, 2020[36]). Moving forward, tackling regulatory challenges across borders in the short- and long-term will be essential. ASEAN Member States are working closely to protect the free flow of essential goods – particularly medical and food supplies – and to keep critical infrastructure and trading routes open, guarding against future shocks under the Hanoi Plan of Action on Strengthening ASEAN Co-operation and Supply Chain Connectivity in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic (ASEAN, 2020[37]).

SEA countries face similar regulatory challenges

SEA countries are facing many of the same regulatory challenges as the OECD governments noted above. Travel restrictions are constraining the tourism and hospitality industries, regional supply chains are being disrupted, trade and investment flows have declined, and stringent social confinement measures have decreased consumption, creating ripple effects felt across both MSMEs and large businesses (OECD, 2020[38]); (ADB, 2020[39]). In response to the crisis, nearly all SEA economies have eased their monetary policies and instigated various fiscal stimulus mechanisms such as salary subsidies, rent support, tax cuts, loan moratoriums, temporary cash transfers, etc. (OECD, 2020[38]).

Evidence from the Asian Development Bank’s COVID-19 Policy Database shows that economies have remained active in supporting incomes, liquidity, and credit measures (ADB, 2020[40]). Central banks continue to play a significant role, not just in promoting liquidity and credit creation, but also in supporting fiscal measures. International assistance has increased significantly, and may continue to rise in the near future. As of June 2020, international assistance to the ADB’s Developing Members in the form of grants and loans increased twelvefold to USD 16 billion (ADB, 2020[40]).

Governments have also continued to pursue good regulatory practices while striking the balance between short- and long-term regulatory policy responses as well as between centralising decision-making and exercising regulatory flexibility (OECD, 2020[17]). Administrative burden reduction remained integral to promoting resilience and stimulating economic recovery during the pandemic. For example, Viet Nam shifted over 1 000 in-person services online in their National Public Service Portal and reformed administrative procedures to support economic growth, even when social distancing (APCA, 2020[25]). Similarly, the Philippines Anti-Red Tape Authority quickly streamlined a number of procedures, reducing the number of permits, documents required and time necessary to complete them (APCA, 2020[25]).

The pandemic has also created opportunities for regulatory innovation and transitioning towards higher digital government maturity in SEA countries, much as in OECD countries noted above. This was especially geared towards digitalising regulatory delivery services, while also using digital technologies to facilitate implementation of regulatory processes while further protecting public health by reducing person-to-person physical contact (OECD, 2020[17]). Digital technologies, some implemented prior to the pandemic outbreak, also helped cushion some of the impacts of pandemic lockdowns (ESCAP, ADB and UNDP, 2021[41]). The November 2020 ASEAN Summit saw the updating of the ASEAN Accelerated Inclusive Digital Transformation strategy, including the digitalisation of trade processes for 152 essential goods, and the launch of the Go Digital ASEAN initiative to provide digital tools and skills to small enterprises and youth, and several country-level programmes adopted to both mitigate impact and contribute to recovery (ESCAP, ADB and UNDP, 2021[41]). The Go Digital ASEAN initiative was approved by the ASEAN Co-ordinating Committee on Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (ACCMSME) during its eighth meeting in November 2019, with the goal of expanding opportunity across ASEAN countries, by equipping underserved communities with critical ICT skills to leverage the digital economy, and raise awareness of this opportunity among senior ASEAN officials and ministers (ASEAN, 2020[42]). The target beneficiaries are micro and small businesses and underemployed youth, including farmers, home-based handicrafts producers, farming co-operatives, eco-tourism enterprises, small-scale hotels and restaurants, small shops and other traditional modes of employment and income-generation (ASEAN, 2020[42]).

However, while digitalisation bears a lot of potential benefits, inclusive recovery also requires policy makers to engage in helping those less able to benefit from these new tools. This accelerated shift towards digitalisation and the adoption of new technologies require MSMEs to be equipped with the ability and capacity to learn new skills continuously and to collaborate with a broad range of stakeholders. Many ASEAN MSMEs still struggle to adopt and use digital technologies and tools, compared with larger companies with more resources to invest in training, reskilling, and upskilling (ERIA, 2021[43]), which mirrors difficulties faced by MSMEs in OECD countries (OECD, 2021[44]). Moreover, large digital divides within and between countries have meant that not everyone has access to, and can benefit from, accelerated digitalisation. This situation may reinforce risks of an uneven recovery, and requires that rebuilding strategies consider inclusive implementation of digital strategies to ensure no one is left behind (ESCAP, ADB and UNDP, 2021[41]). Moreover, digital skills are also important for public sector officials who need to make sure of these technologies, as well as for consumers who need to access digital platforms, such as e-commerce, during times of physical distancing and confinement.

SEA and global recovery will require a focus on better regulation

Prior to the pandemic, the ASEAN region was one of the fastest growing in the world. While the OECD had forecasted the region to achieve 5.7% GDP growth annually in the 2020-2024 period (OECD, 2019[45]), the pandemic resulted in an estimated fall in GDP by 3.4% in 2020 (OECD, 2021[46]) – the region’s first contraction since the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis (ADB, 2020[47]). However, this varies greatly among countries depending on factors such as the length and severity of restrictions and lockdowns, differing initial conditions and economic structures, and government capacity to support households and businesses (OECD, 2021[46]). Viet Nam was projected to post the strongest growth rate in 2020 (+2.6%), while the Philippines was projected to experience the sharpest GDP contraction in 2020 (-9.0%) and Cambodia would similarly experience the weakest growth rate (-2.9%) amongst CLM countries (Cambodia, Lao PDR and Myanmar) (OECD, 2021[46])..

While the OECD expects global GDP to rebound with a 5.7% growth rate in 2021 (OECD, 2021[1]), regions and countries will diverge in their recovery tracks. Given their role in global trade of manufacturing goods, particularly electronics, SEA countries are likely to play an important role in the global economic recovery with an estimated 2021 GDP of 5.1% for the region (OECD, 2021[46]).

As previously discussed, regulations play a key role in promoting economic activity while safeguarding individuals, workers and the environment. Better regulation is often assumed to be synonymous with de-regulation, but it is not: regulation is vital. Without it, markets cannot work and the most vulnerable cannot be protected; but countries need regulation that works, both in times of calm and in times of crisis.

It is for these reasons that the ASEAN-OECD Good Regulatory Practices Network (GRPN) focused on better regulation during its sixth (2020[17]) and seventh (2021[18]) meetings, and developed a survey of its members to provide data to underpin key messages from better regulation practices, initiatives and reforms. A central take-away from these meetings is that implementation of regulatory reforms, including GRPs, can strengthen regulatory frameworks across SEA, which in turn supports both the regional and global recovery. GRPs are useful policy tools in a crisis as they ensure that regulations are effectively designed and implemented to deliver the policy goal that they are set to achieve, as was seen above. This section will end with a brief summary from the various discussions, according to the structure of the GRPN meetings.

Reducing burdens to support better regulatory outcomes

Even if GRPs are abridged due to time and resource constraints, they can strengthen government responses to the immediate crisis while helping build more resilient risk management systems in the long-term. As discussed in the sixth meeting of the GRPN (2020[17]), some governments prioritised quick regulatory response delivery, including streamlining regulations for medical equipment and investment. This can be achieved by using fast-track procedures and leveraging existing regulatory flexibility.

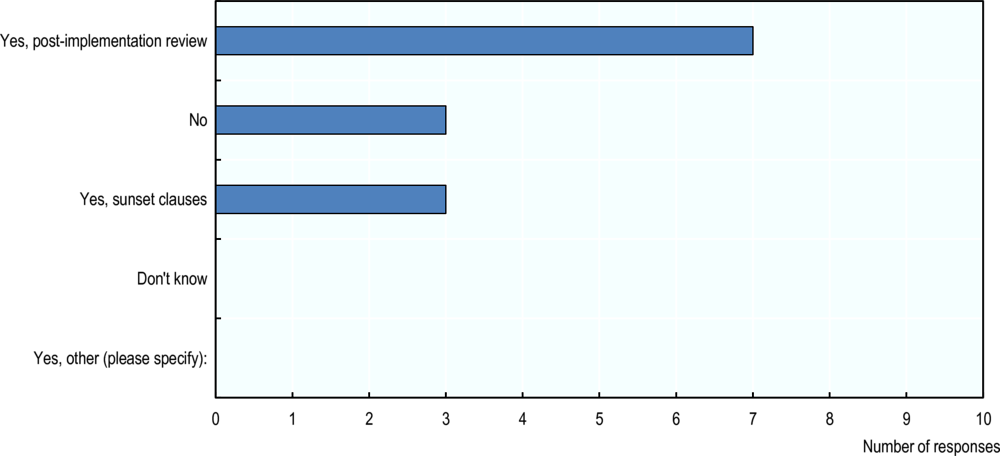

Furthermore, countries can still support evidence-based decision making by ensuring that regulations are properly evaluated using ex post reviews and sunset clauses to automatically expire COVID-19-related measures. Some governments also rely on informal stakeholder consultations and expert advisory groups to facilitate agile regulatory design and delivery, although special attention should be paid to inclusiveness to ensure that the concerns and inputs of all affected by regulatory changes are considered as much as possible.

Leveraging digital tools for more agile regulatory policy making

The sixth meeting of the GRPN also explored how digital technologies can support governments in maintaining service delivery and stimulating the economy while protecting public health by reducing person-to-person physical contact (OECD, 2020[17]). Countries harnessed digital tools and data to strengthen good regulatory practices and improve regulatory design, including broadening stakeholder engagement to consult with interests groups that have been traditionally less engaged, such as MSMEs. They also helped improve regulatory delivery by easing burdens and compliance costs for businesses and citizens while increasing the efficiency and transparency of regulators, as well as enabled e-inspections, e-accreditation, and e-procurement systems without compromising regulatory quality. Evidenced-based, data-driven decision making can enhance regulatory responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Digital applications such as real-time websites and mobile phone applications also helped facilitate clear communication and guidance regarding public health measures.

Nonetheless, discussions highlighted that policy makers must be even more attuned to personal freedoms such as privacy as well as data protection and cybersecurity as governments increasingly rely on digital technologies to collect, process and share data, including personal data, to slow the spread of the virus – themes further emphasised in OECD (2020[48]); (2020[49]). Even prior to the pandemic, emerging technologies posed a number of challenges to governments such as pacing problems, liability attribution, and trans-boundary issues. Digital technologies have forced governments to take new approaches to regulatory policy making, including adopting foresight analysis and horizon-scanning; utilising soft law; and leveraging digital tools, such as single access online portals and digital applications. Furthermore, the integration of IT systems across relevant government agencies and the co-ordination of their regulatory service deliveries are crucial for maximising the benefits of digitalisation.

Regulatory reforms to support recovery and prepare for future crises

The seventh meeting of the GRPN continued the themes explored above, exploring how better regulation can support critical vectors of the economic recovery. SEA countries have performed comparatively well to date in containing and mitigating the spread of the pandemic. This has resulted in smaller shocks to their GDPs compared to many Western nations, and has enabled them to look forward towards recovery earlier. While there are clearly challenges to better regulatory policy making embedded in the changes that occurred due to COVID-19, such as the lack of robust ex ante analysis to ensure decisions are made on the best evidence possible, there were also a number of opportunities to “lock in the gains” for improved policy making going forward.

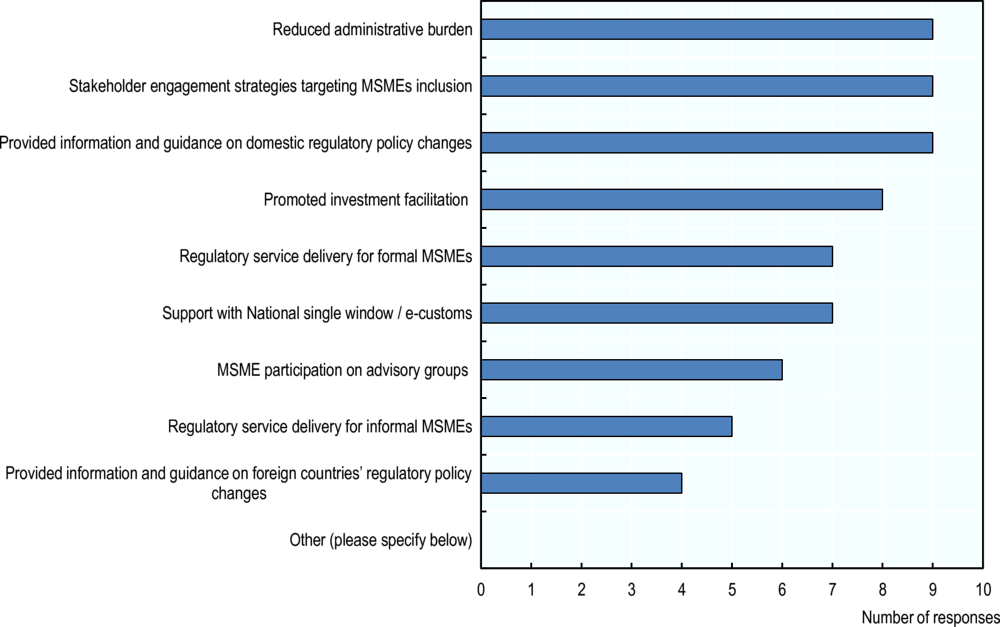

Discussions highlighted that now, more than ever, better regulation reforms are needed (OECD, 2021[18]). As economies recover, governments will need to focus on reforms that make investment, trade, and business facilitation easier, especially for MSMEs that make up 70-98% of all businesses across most SEA economies (OECD, 2018[21]). This will require a focus on the better regulation fundamentals, including inter-agency co-ordination to align central requirements with the practical experience of technical ministries, departments and agencies and their clients and stakeholders. Furthermore, reducing administrative burdens – both for businesses and citizens, but also within government – can benefit recovery efforts from a whole-of-society perspective, especially with the aid of digital technologies and one-stop shops (OECD, 2020[50]). This includes taking an “omni-channel” approach, which advocates for consolidating all government websites into a single domain where the design and architecture of services supports access through any channel, from any device, at any point in a new or existing service journey (OECD, 2020[51]). Regulatory innovation, including risk-based approaches and sandboxes, can also provide the necessary flexibility for an agile recovery.

Preparing for the future, it is well noted that the SEA community has a strong basis for better regulatory management. This is supported by sound regional-level efforts led by the ASEAN Secretariat, including ASEAN Guidelines on Good Regulatory Practices (2019[8]) from before the pandemic and a priority on better regulation that cuts across the ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework (2020[52]) and Implementation Plan (2020[53]). ERIA has also supported SEA economies with analysis on regulatory management systems (ERIA, 2020[54]).

Keeping a commitment to better regulation reforms will be essential in promoting agility and resilience, including developing ways to improve international regulatory co-operation (IRC) to ensure SEA countries are working together now and in the future to discuss, design, implement and enforce effective regulation (OECD, 2020[17]); (ERIA, 2020[55]); (ERIA, 2020[56]). Effective IRC allows countries to support quick, internationally-aligned responses to cross-border crises and support recovery by lowering regulatory barriers to trade and investment. Ex post reviews will be more important than ever, not only to ensure COVID-era policies are properly evaluated but to support broad, system-wide efforts to identify and reduce burdens and modernise regulatory stocks to be more risk-based.

To support these wide-reaching regulatory policy priorities, the OECD worked with GRPN members to conduct a survey of regulatory practices during the crisis to identify trends and support reform efforts. The final section of this paper will present an overview of those results and key findings, with the full results and methoodolgy presented in the Annex.

3. Analysis of key findings to support better regulation for COVID-19 responses in SEA countries

Governments are still facing untold pressures in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. As seen above, national governments around the world, including ASEAN Member States, have passed emergency legislation and enacted non-legislative regulatory changes to urgently respond to daunting public health and economic challenges. Especially in the early days of the pandemic, governments were doing so without precedent or comparative examples (to the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic) to enable quick and accurate decision making. This is where international forums, like the ASEAN-OECD Good Regulatory Practices Network (GRPN), played important roles in creating a space for dialogue and mutual learning.

A stronger demand from the network and other policy communities, such as the OECD Regulatory Policy Committee (RPC), has emerged for more evidence of regulatory practices around the world to inform public action. The above sections highlighted findings from OECD COVID-19 Policy Papers, produced in collaboration with the OECD RPC and Network of Economic Regulators, and discussions from the GRPN. While these highlight trends and practices from a qualitative perspective, it is important to dive deeper with data to better contextualise these challenges and opportunities.

The GRPN thus launched a survey of members in September 2020 to gain data points to help build a fuller picture of how governments used regulatory policy making to respond to the crisis. A full explanation of the methodology can be found in the Annex.

This section presents a discussion of the key findings, based on the results of the survey found in the Annex. As these are an overview based on a single survey, further investigation is still needed to determine their full effects on the quality of regulatory decision making.

Key finding 1: With pandemic decision making more centralised in the centre of government, line ministries/departments seemed to play an important role in regulatory policy making alongside ad hoc COVID-19 co-ordination committees.

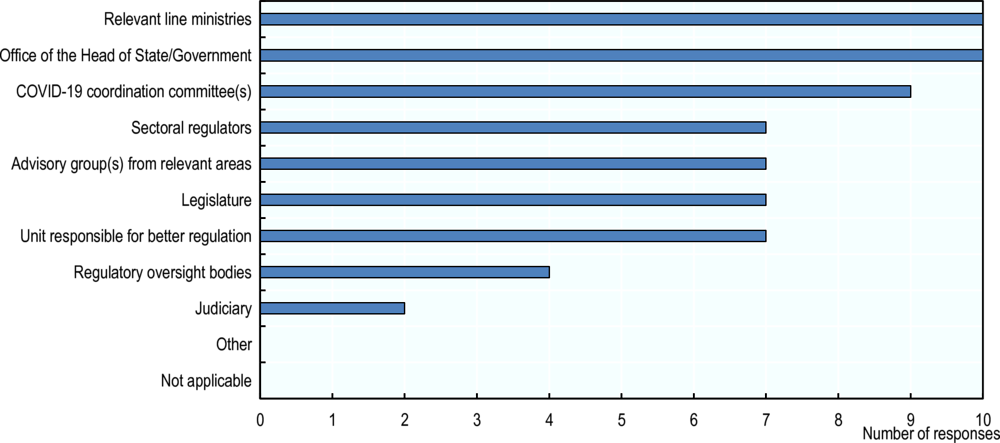

All ten responses noted that the Office of the Head of State and/or Government and relevant line ministries were equally involved in regulatory policy making during the crisis. Seven identified the use of sectoral regulators and better regulation units, and only four identified the use of regulatory oversight bodies. Without further evidence, it is unclear what this means in terms of the quality of regulatory decision from a whole-of-government perspective that usually incorporates a wide variety of actors in regulatory policy making.

This may indicate a number of possible scenarios. One may be that highly centralised, crisis-oriented decision making during the pandemic prioritised advice from units who are already traditionally close to decision makers, compared to those further away or performing scrutiny functions that could potentially slow down decision making. This may have weakened some of these agencies or units. Alternatively, by way of their independence and mandates, many agencies may have continued to make regulatory decisions without necessarily co-ordinating with the central units. There is also a continuum of possibilities between these two options, or may have been addressed through ad hoc co-ordination committees, which may have enabled decision makers to access this regulatory advice in different ways, depending on the construction of these committees.

Appropriate post-pandemic review of government performance may want to investigate this further, including what affects, if any, this had on policy making and how those lessons could be learned in preparation for the next crisis. For instance, it is possible that policy decisions were potentially skewed towards broader, more community-wide decisions (i.e. to all types of businesses) compared to targeted or sectoral policies aimed at a subset of the community (i.e. MSMEs). Depending on the results of reviews, focus should also be on returning any mandates, roles and procedures of these agencies following the pandemic.

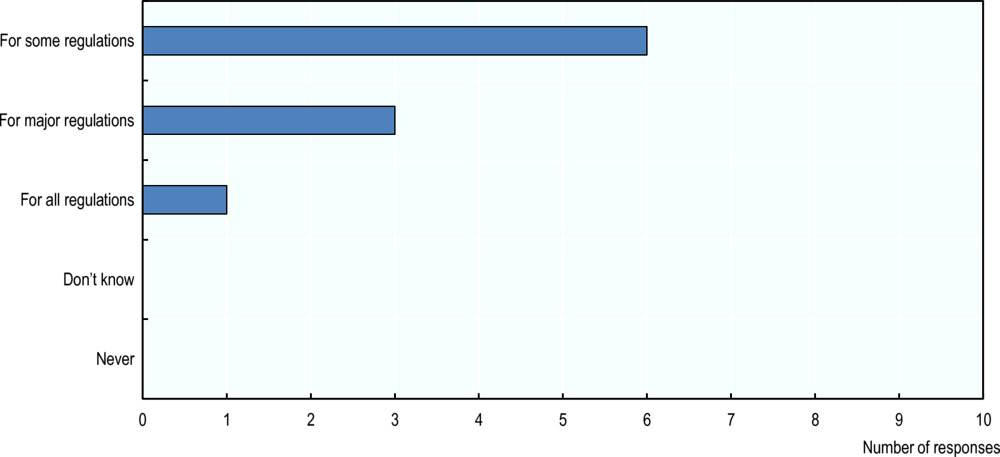

Key finding 2: Pandemic-induced changes to regulatory management systems seem to focus on reducing process-oriented burdens, often with a focus on relaxing or applying more flexibility in conducting evidence-based analysis.

In the context of a fast moving crisis, a focus on burden reduction can help speed up government decision making, and facilitate compliance amongst businesses and citizens as they adjust quickly to a new operating environment, especially to support MSMEs (see a range of examples from Viet Nam and Indonesia in the Annex, Box 1 and Box 2 respectively). For instance, responses highlighted how requirements to conduct regulatory impact assessments (RIAs) or stakeholder engagements were relaxed, suspended or sometimes bypassed altogether in a majority of countries, which was a trend noted in many OECD countries as well.

Evidence from GRPN discussions indicates that ex ante evidence and analysis is still collected, but with a focus on qualitative reasoning. Countries are also using innovative avenues to access evidence, such as expert advisory groups or virtual consultations. For example, in Malaysia, the #MyMudah Programme allowed companies and businesses to highlight regulatory issues through the Unified Public Consultation (UPC) Portal, as well as to take part in dialogues organised by the government (see Annex, Box 4).

Responses seem to indicate less of a focus on regulatory delivery and/or sectoral issues, such as MSMEs or enterprise promotion. However, this could also reflect the position of the respondents, who are generally located in better regulation units focused on burden reduction and improving regulatory management systems, and would have more sensitivity to these changes over sectoral changes. A few new regulatory requirements may have also been needed to deal with particular features of the pandemic, such as contact tracing or quarantine rules, which again will require further investigation to ensure this is not a bias of the respondents.

Key finding 3: Ex post review will clearly play a significant role as countries emerge from the pandemic, especially to lock in the gains from what worked and evaluate decisions made to ensure they remain fit for purpose.

Seven of ten respondents noted their government plans to use ex post reviews, such as sunset clauses or post-implementation reviews, to evaluate regulatory decisions made during the pandemic. While this indicates strong intent, the key for governments will be to ensure these reviews happen in practice and not follow pre-pandemic trends across the world of “setting and forgetting” regulation. It will be key to gain insights from these reviews as to how flexibility can be built into the regulatory policy making system on an ongoing basis, and make sure to address any changes necessary as governments switch from pandemic to post-pandemic operation.

Key finding 4: Post-pandemic reform efforts could also focus on exploring ways to “future proof” regulation to cope with crises, including what to activate when a crisis hits or de-active once it has eased.

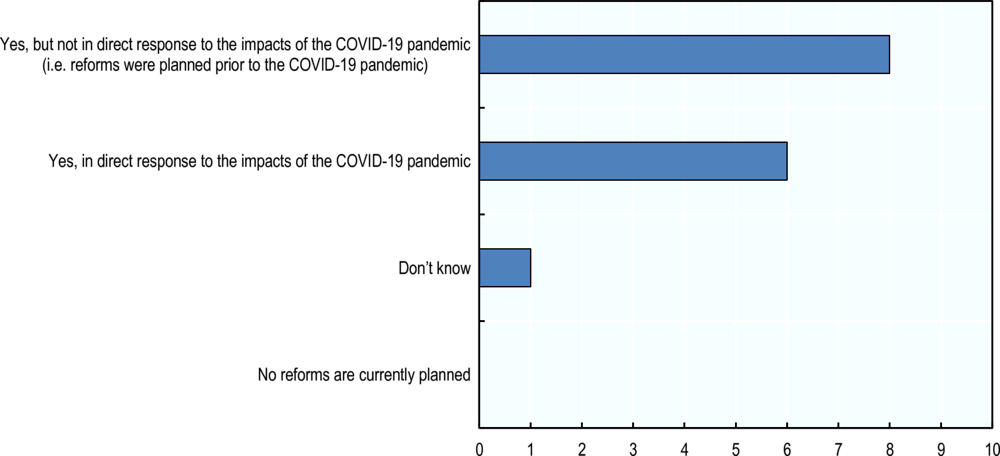

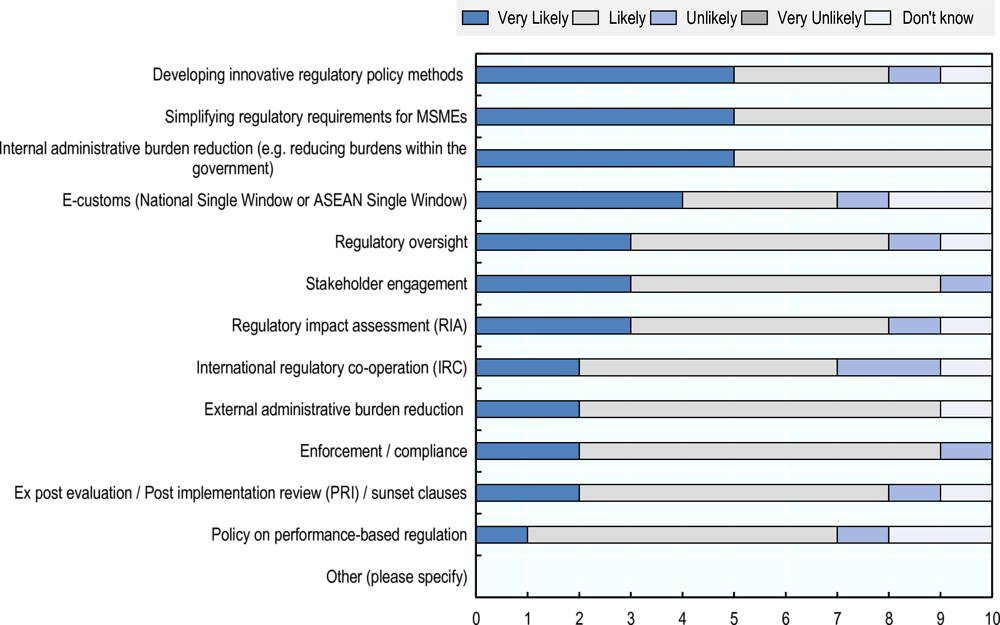

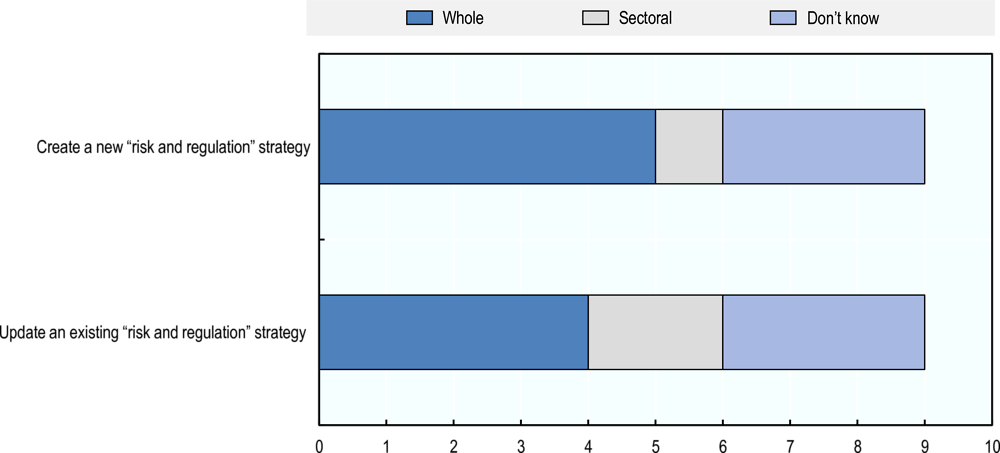

Nine out of ten respondents noted that their governments would pursue regulatory management reforms in the next three years, with slightly more respondents stating that these reforms were planned prior to the pandemic versus in direct response to the pandemic itself. These reforms appear to be mostly focused on administrative burden reduction and RIA, which have been popular reforms in the region for some time and perhaps reflecting an inertia towards these types of reforms. Recent such regulatory reforms from before the pandemic in Thailand and the Philippines can be found in the Annex (see Box 3).

Respondents also identified important recovery-oriented reforms, including improving regulatory oversight and supporting trade through reforms like e-customs. International regulatory co-operation approaches (IRC) may thus provide SEA countries with an interesting opportunity to further strengthen regulatory frameworks for trade and investment, as it supports governments’ efforts to reduce domestic burdens for trading and investing and improve evidence-based policy making. A slight majority of respondents did note that they looked to foreign jurisdictions or international organisations to inform domestic policy responses to the pandemic, which is a way that IRC can be used more systematically.

Key finding 5: As in OECD countries, SEA countries clearly leveraged digital technologies to adapt quickly and ensure governments continue to perform their functions; however, it is unclear what effect this has had on regulatory quality.

Respondents identified the broad use of digital meeting, social media and webinar platforms, which points towards facilitating government operation and communications by providing transparent, timely and effective information to citizens and businesses to support effective stakeholder engagement. Most often digital technologies were used in containment and mitigation efforts to help track, trace and monitor disease spread. For example, Singapore used the TraceTogether (TT) programme to complement and automate manual contact tracing efforts via a mobile application (TT App) and a physical device (TT Token), as well as the SafeEntry system for public venues (see Annex, Box 8).

However, few respondents noted their use in RIAs or ex post reviews. This may offer clear avenues to innovate with regulatory management tools. Some countries have been exploring innovative applications of digital technologies to support outcomes, including promoting more meaningful two-way consultations and improve regulatory delivery that may provide some ideas for the broader SEA community. Though, careful attention will need to be paid to ensuring inclusiveness to avoid exacerbating issues with the digital divide.

4. Conclusions

Based on the discussions during the sixth and seventh ASEAN-OECD Good Regulatory Practices Network (GRPN) meetings and the survey of GRPN key contact points, it is clear that SEA countries’ efforts to combat the COVID-19 pandemic were underpinned by their enduring commitment to regulatory reforms. The majority of SEA countries had been committed to better regulation reforms for several decades prior to the pandemic, putting their governments in a position to leverage this knowledge and experience to improve their countries’ pandemic response. Moreover, networks such as the GRPN offered effective platforms for exchanging ideas and fostering mutual learning to support efforts to update, amend and create new regulatory responses as the pandemic evolved.

Consistent with the experience in many OECD countries, SEA countries quickly enacted administrative burden reduction and process simplification reforms at the start of the pandemic to enable a more agile, inclusive and wide-ranging government response to the pandemic. Coupled with strong centralised decision making, regulation was one of the key levers for SEA countries as they sought policy solutions to the challenges imposed by the pandemic. Digital technologies were also widely used to adapt quickly to the new socially-distanced environment, especially for facilitating stakeholder engagement, and remain an opportunity going forward for improving regulatory quality.

However, while this policy brief presents a snapshot of the GRPN discussions and survey results, it certainly does not paint the full picture. Given that most respondents are located inside better regulation units, either in the centre of government or economy-oriented ministries, discussions and responses clearly highlight the role of simplification and good regulatory practices but focus less on how these tools are being used concretely at the sectoral level. For example, more detail is needed from the perspectives of regulatory ministries, delivery agencies and independent regulators, which may shed more light on how regulatory policies affected important sectoral issues for SEA economies, including for SME development, trade facilitation and investment promotion. More detail is also needed to understand the role that regulatory oversight played in ensuring regulatory quality during the pandemic.

As we move from the immediate crisis response into the recovery phase, these results should encourage SEA countries to engage in systemic reviews of their regulatory policy making system and stock of regulations to ensure they are both fit for purpose and ready for the next crisis. On the former, given the speed at which the pandemic evolved, governments should reflect on how their entire system of regulatory policy making functioned during the pandemic and learn from this experience to both enact any immediate necessary reforms in the short term and prepare for crises in the longer term. On the latter, regulatory decisions made during the pandemic should be subjected to post-implementation reviews to ensure the decisions remain fit for purpose and, if not, removed from the stock of regulation. This would also provide another opportunity for the government to engage in system-wide learning opportunities.

Moreover, forums like the GRPN are well placed to play a central role in supporting governments in this reflection and reform process. This includes providing a platform to share experiences to support mutual learning, as well as access peer support from fellow SEA and OECD countries. The GRPN could also collect these discussions and findings, documenting them to support broader learning opportunities that can benefit ASEAN regional co-operation and sustainable development goals.

Annex A. Survey results – Regulatory policy making reforms to support better outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic

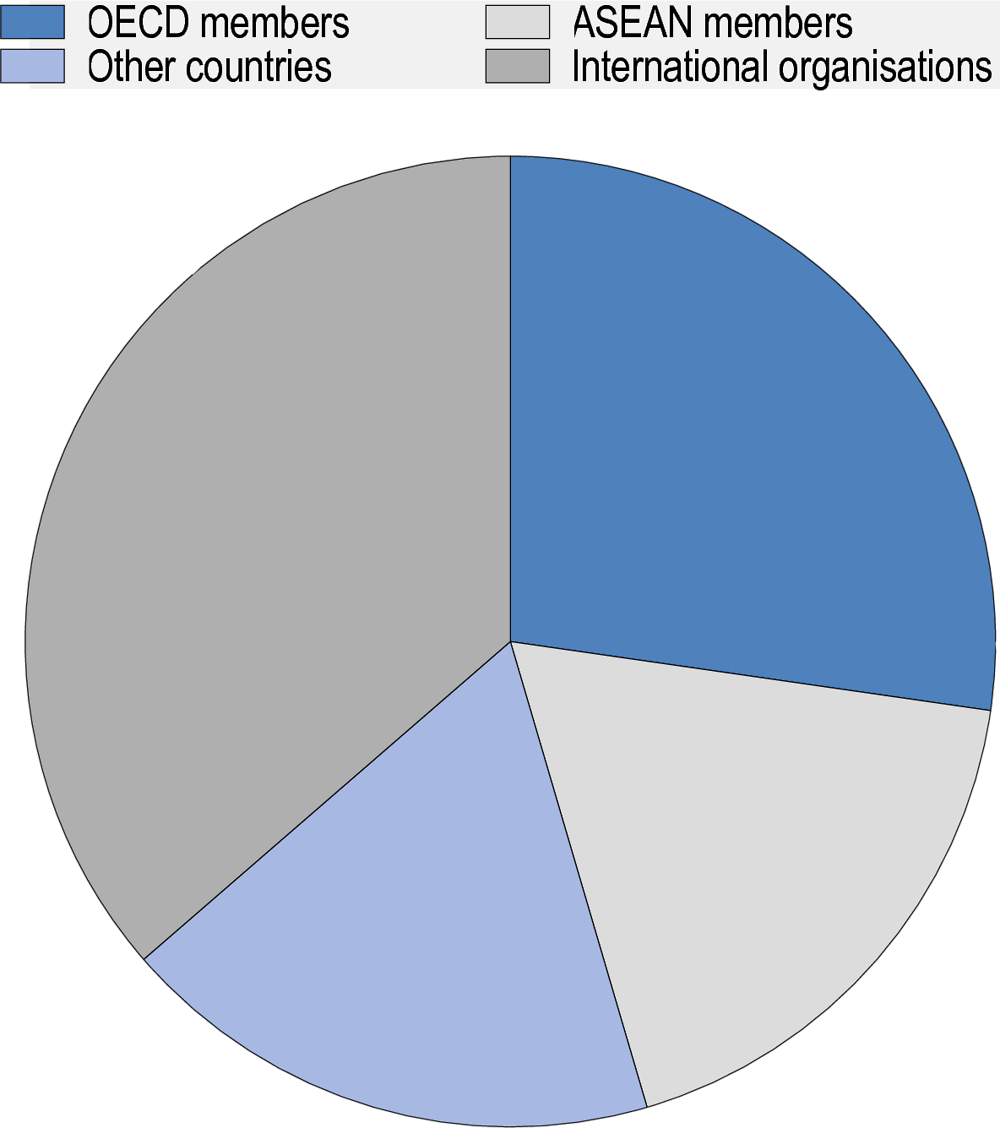

Methodology

The survey was developed by the OECD Regulatory Policy Division, in consultation with the GRPN co-chairs, Malaysia and New Zealand, as well as the host of the sixth GRPN, the Government of Viet Nam. It consisted of a series of questions according to three broad themes, which mirrored the session themes of the sixth GRPN (OECD, 2020[17]): GRPs and burden reduction, digital technologies, and lesson learned going forward. The purpose of the survey was to add evidence and data to the discussions in the GRPN meetings and to inform the network’s programme of work. Given the complexity of regulatory issues, the survey was not intended to provide definitive answers to support conclusions about better regulation during the COVID-19 pandemic in the SEA region.

The questions were informed by the OECD regulatory policy COVID-19 Policy Papers, cited above. Elements of the survey questionnaire also parallel the OECD’s Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance (iREG) 2020 survey to enhance direct comparisons between OECD and ASEAN Member States and better inform future analysis. iREG data is presented in the OECD Regulatory Policy Outlooks (2015[20]); (2018[21]); (OECD, 2021 – forthcoming).

The survey was developed during the spring of 2020, tested amongst the GRPN co-chairs and host in summer 2020, and distributed to all 10 SEA countries in September 2020. GRPN main contact points were used to distribute the survey. Responses were received from all 10 ASEAN countries, most of which coming between October 2020 and January 2021, with two countries arriving in May 2021. This response rate gives they survey a representative sample of SEA nations. However, since the time period for receiving answers was quite wide, there may be some inter-country differences in answers that are a result of answering the survey at different points in time.

The results are presented as aggregated data (anonymised by country) with the exception of cases highlighted in boxes, which were cleared bilaterally with the country through a fact checking process before final publication. The decision to present data in aggregate was to:

Allow respondents more latitude to answer questions without needing to engage in extensive internal collaboration within their government, which is normally associated with benchmarked data collection;

Limit the time period between OECD receiving the data and publishing results; and,

Out of recognition that the survey is meant to provide an indicative sense of trends in the SEA region, and not as an authoritative set of evidence upon which concrete conclusions can be drawn.

This approach allowed the survey to be implemented, answered, analysed and released quickly to help support governments respond to COVID-19 while the pandemic is still present, and as early in the recovery period as possible. Moreover, since information to fact check answers are not always available publicly and, when they are, it may require specific language skills to access, the responses were not checked further via searches for such data. Respondents were asked to submit supporting information where possible, but this was not made mandatory to minimise the burden on respondents and support a quick turnaround to aid governments respond to the pandemic in the moment.

Limitations

Given the survey’s construction, several limitations need to be noted as readers analyse the data. First, this survey is a snapshot from a period of time when the pandemic was still moving quickly and many governments were in the tail end of the first wave, while others were received during second or third waves. This may create differences in how governments view regulatory reforms vis-à-vis the pandemic, as such experiences going through multiple waves may have allowed some governments to further iterate their regulatory systems in response. As a result, while macro trends are still likely to be valid, individual country examples may be somewhat different than when collected. Any further data collections will need to build upon this work and discover what has changed, and why.

Second, the nuance of country-level differences is not apparent in the results or analysis. For example, administrative, political, and societal culture can often have an impact on the way governments approach various decision making processes. This further limits the ability to draw conclusions based on this data, aside from general trends in relation to OECD normative guidance.

Finally, the results reflect individual respondents who work on better regulation in the centre of government who may not have perspective over all aspects, including sectoral applications, of better regulation reforms and regulatory policy making practices in their government. It is possible that at the technical ministry, department, or agency level, practices are different and the survey does not capture these nuances.

Taken together, these limitations encourage readers to approach the results as they are intended: data points that help to bring depth to the discussions held in the GRPN meetings. The OECD encourages further research to explore the various findings to illuminate trends and explanations that are more quantitatively robust.

Results part 1: Whole-of-government regulatory response to the COVID-19 pandemic

OECD normative guidance on better regulation starts with a recognition that countries need commitment from the highest political level to an explicit whole-of-government policy for regulatory quality (OECD, 2012[6]). OECD and accession countries continue to invest in this approach, with the vast majority of them adopting an explicit policy promoting government-wide regulatory reform or regulatory quality and established dedicated bodies to support the implementation of regulatory policy (OECD, 2018[21]). Evidence similarly shows that SEA countries, by and large, recognise the importance of better regulation reforms and are increasingly investing in various reform efforts (OECD, 2018[9]).

In presenting the results of the survey, this first section looks further at these strategic points to pinpoint how and where regulatory decisions are being made and what sort of priorities are being considered by decision makers.

Decision making

Responses from the survey demonstrate the strong role played by the executive branch in SEA countries in responding to the pandemic (see Figure 1). This reflects various realities. First, it is the role of the executive branch, through its units at the centre of government, ministries, departments, and agencies, to govern the country on a day-to-day basis. Second, many countries separate primary law making and subordinate regulations between the legislature and executive, respectively. Finally, when speaking of better regulation, many of the discussions focus on the tools and processes for developing regulations – i.e. use of regulatory management tools – which is an internal governance issue set by the executive for its own use.

Note: Title reflects question asked to the respondents. Data reflects the responses from the ten SEA nations who responded this survey via the GRPN main contact point, and does not include data from OECD countries.

Source: Data from the 2020 Surveys on ASEAN Member States’ Regulatory Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic, implemented by the OECD Secretariat.

Some interesting sub-trends emerged. First, and most logically, all survey respondents replied that relevant line ministries and the office of the head of state/government were involved in pandemic-related decision-making process to adopt, amend or suspend regulations. The results show that while crisis decision making is often highly centralised, the model of co-ordination by the centre of government and ministerial involvement and advice through ministries/departments continued during the pandemic. As noted in the OECD (2021[57]) Government at a Glance, this trend is similar to OECD countries where, among the 26 countries for which data were available, 20 (77%) of centres of government were having to provide support to more co-ordination instances during the pandemic, and more stakeholders participated in co-ordination meetings called by the centres of government (19 out of 26, 73%). One possible side effect of this may be an over reliance on community-wide policy decisions, such as a single policy for all forms of businesses, rather than targeted or sectoral policies geared towards specific subsets of the community, such as MSMEs. Post-pandemic reviews of government policy making during the crisis will need to examine this in more detail to determine if this did happen in practice and, in preparation for the next crisis, how more targeted solutions can also be encouraged during times of crisis.

Second, this model of regulation was strengthened with the agile creation of ad hoc support bodies, which require further study to understand their full role but likely supported improved co-ordination and provided extra advice to the executive branch. Nine out of ten survey respondents replied that COVID-19 committees were involved in the decision-making process to adopt, amend or suspend regulations in response to the pandemic. The effective role of these committees in the actual decision-making process may be a good example of agile governance, pending further review. Moreover, depending on the composition, involving COVID-19 committees in the regulatory decision-making process may have diversified the views involved compared to a solely centrally-run pandemic response.

Third, and contrary to the last point, regulatory bodies further away from the centre of government seemed to be less involved from the perspective of the respondents. This may have had the effect of making decision making less robust, unless their roles were preserved in other ways such as on the ad hoc committees or using their independence to maintain their functions. Seven out of ten respondents reported the involvement of sector regulators in government’s response to the pandemic. OECD (2020[29]) and (2020[5]) note the important role for sector regulators and regulatory delivery agencies in COVID-19 responses. Sector regulators play a large role to ensure that markets function and quality essential services are provided during times of crisis. Regulatory delivery focuses on driving compliance with regulations through enforcement and inspections, which can have direct impacts on access to important pandemic supplies, such as personal protective equipment, while safeguarding everyone against unsafe products. The data collected does not specify how regulatory delivery agencies and systems operate in ASEAN, especially in the context of the pandemic, and would need to be further studied to discover concrete interpretations to these results.

These responses may be interpreted a few different ways. First, it may again represent the perspective of the respondents who are generally located in better regulation units inside government and may not have full visibility over the actions taken by more independent agencies. Second, sector regulators and delivery agencies are often independent from the executive (to varying degrees in different countries), thus being able to make decisions without involving the executive and vice versa (OECD, 2016[58]). In this case, they would be responding to the crisis in tandem with centralised efforts, as discussed in OECD (2020[29]); (2020[5]), but may not be consulted on a day-to-day basis and thus perceived to be less involved. Third, it could be that their involvement is captured in ad hoc co-ordination structures, used by nearly all countries according to respondents and may include agencies in these co-ordination structures. Fourth, centralised decisions may override the decisions issued by more independent agencies, which may seem justifiable in a crisis setting but should be evaluated against the purpose behind systems of independent regulators that are intended to protect markets from undue influence (OECD, 2017[59]) and to safeguard and enforce strong, fair and quality regulations. Finally, it could just represent a fact that independent sector regulation is less common in the SEA region, and thus would not be a relevant issue for many. The OECD does not have robust data on sector regulation in the SEA region to determine if this would be the case. It is impossible from this data to determine what explanation, or combination thereof, is correct. In fact, this would be the basis of a dedicated study on its own. Post-pandemic reviews of government regulatory policy making performance may want to explore this finding a further to draw appropriate conclusions.

Fourth, better regulation units and regulatory oversight bodies seemed to be less involved in decision-making processes in SEA countries with seven and four respondents, respectively, reporting their involvement. This is likely a result of the bypassing or simplification of internal processes noted above, as such units are often responsible for the quality and supervision of processes and outcomes rather than having technical expertise in a given policy area. While this is understandable to a degree given pressures on governments during the crisis, there may be a missed opportunity for governments to fast-track regulations but still have quality decision making processes. Better regulation units and oversight bodies have deep understanding of GRPs and better regulation, such that they will also likely have the knowledge of what can be bypassed or simplified and what cannot. Moreover, they can likely provide rapid advice to decision makers on the quality of proposals. These results suggest countries would benefit from evaluating and establishing plans for the involvement of such units in preparation for future crises.

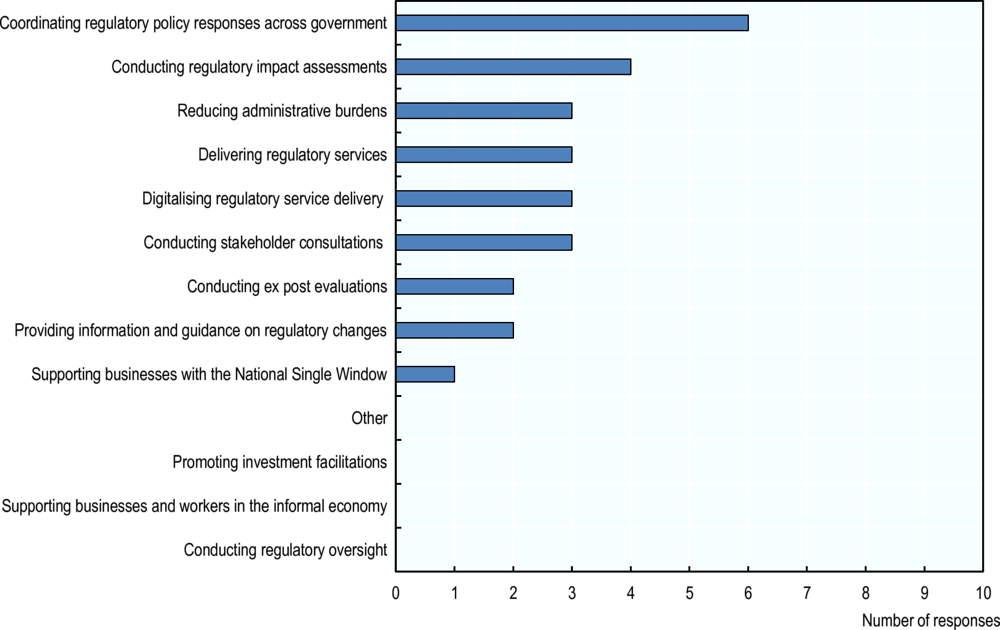

Priorities for regulatory policy making

When asked about what regulatory management issues were of most concern, respondents identified co-ordinating regulatory policy responses across government as the most important (see Figure 2). This is consistent with the above findings on centralised decision making, as in times of crisis and with large administrations, inter-agency co-ordination to inform decision making is vital for operational efficiency, transparency, and the coherence of the regulatory response. The centre of government has a key role to play to articulate governments’ decision-making, including on regulations, co-ordinate line Ministries and agencies, and create and integrate ad hoc structures like the COVID-19 Committee into the whole-of-government process (OECD, 2020[60]). The strong focus on co-ordinating regulatory policy in this survey is conducive to promoting a whole-of-government perspective and improving consistent regulatory delivery.

Note: Title reflects question asked to the respondents. Data reflects the responses from the ten SEA nations who responded this survey via the GRPN main contact point, and does not include data from OECD countries.

Source: Data from the 2020 Surveys on ASEAN Member States’ Regulatory Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic, implemented by the OECD Secretariat.

Conducting regulatory impact assessments was the second most important regulatory management issue with four responses. This may demonstrate a continued commitment to some form of ex ante analysis, even if truncated. Reducing administrative burden, delivering regulatory services, and digitalising regulatory service delivery were collectively in third place, alongside stakeholder engagement. These three may be grouped together as they may be related to governments realising that fast response required more agile processes and procedures, especially allowing businesses and citizens to access government services quickly and efficiently remotely. Stakeholder consultations can also support such efforts, helping governments identify measures to simplify and gaining feedback on possible solutions being developed under tight timelines. Conducting ex post evaluations was also important but to a slightly lesser extent – consistent as well with the analysis presented in the second part of this section. These results seem to place added weight on the analysis that SEA countries have mainly focused on the traditional better regulation approaches during the pandemic, which were a focus of most SEA countries’ reform efforts before the crisis (discussed in Section 2).

No respondents chose to include promoting investment facilitation or supporting businesses and workers in the informal economy, while only one respondent included supporting businesses with the National Single Window. This is likely, again, a result of respondents not being in a position to have a broad picture of all activities happening across their government. It also may reflect the fact that these mechanisms were not considered high priority in the response to the pandemic, pointing to a disconnect between the centre of government’s wider focus and the need for co-ordinated approaches with technical areas that are left with line Ministries and agencies, such as investment promotion agencies. Post-pandemic reviews may want to investigate this linkage further.

Regulatory oversight was also not considered as central to regulatory management issues facing SEA countries, with no respondents choosing this option. This highlights previous points regarding potentially missed opportunities to include scrutiny into decision making as a method for improving regulatory decisions.

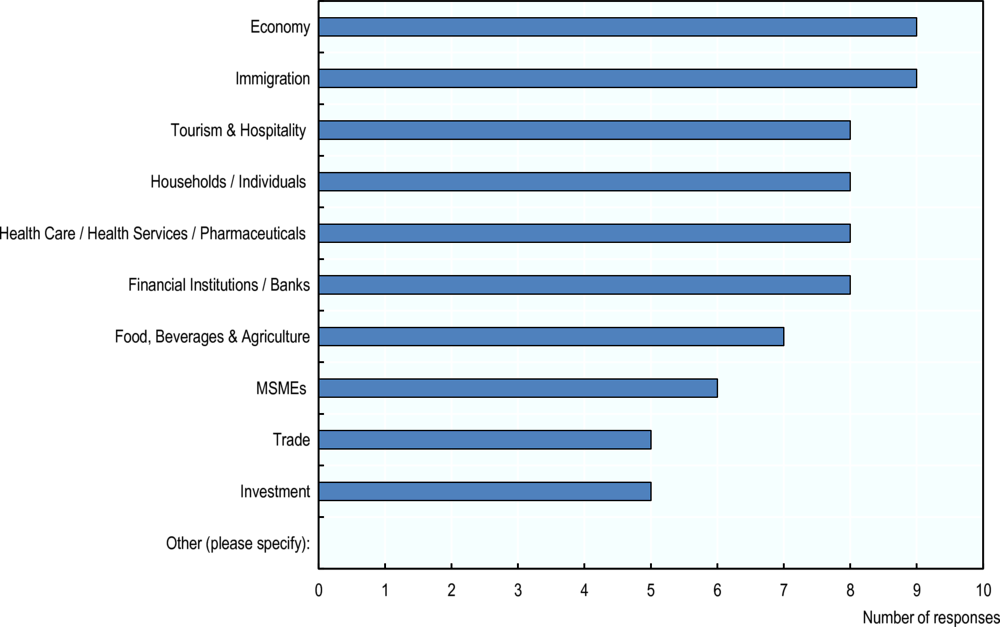

Regulatory impacts on sectors in SEA countries

The COVID-19 pandemic has touched nearly every part of our societies. In response, governments have had to develop policy responses across the board (see Figure 3). Economy and immigration experienced the most regulatory changes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic according to the survey, with nine out of ten countries reporting that significant regulatory changes were made in these sectors. These results reflect the impact that COVID-19 has had on travel and on the economy. However, regulations affecting individuals, health care, food, and financial institutions were all important targets for government to make regulatory decisions to help ease the burden of the pandemic.

Note: Title reflects question asked to the respondents. Data reflects the responses from the ten SEA nations who responded this survey via the GRPN main contact point, and does not include data from OECD countries. The survey also did not differentiate between domestic and international forums, thus there may be overlap within categories, such as policy areas related to pharmaceuticals, food, MSMEs, etc. with responses like trade.

Source: Data from the 2020 Surveys on ASEAN Member States’ Regulatory Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic, implemented by the OECD Secretariat.

This data reflects findings from the GRPN and other OECD webinars on better regulation to support COVID-19 response, which also highlighted the multi-front battle facing governments around the world. On the one hand, many governments focused on enacting emergency powers to centralise decision-making – especially in the early days of the pandemic. For example, Thailand centralised decision making through the Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration (CCSA) under the auspice of the Prime Minister after issuing the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situation B.E. 2548 (2005). Over time, Thailand’s regulatory focus shifted from public health toward economic recovery as the country managed to maintain relatively low numbers of COVID-19 cases. Other governments in the OECD, such as the Netherlands, have benefited from existing regulatory flexibility and limited the number of new regulations adopted by first evaluating if existing legislation can address COVID-19 related challenges (OECD, 2020[7]).

On the other hand, governments in SEA also prioritised quick regulatory response to ensure the delivery of essential goods and services. This includes the streamlining of regulations concerning the manufacturing, importing, and exporting of medical equipment and other essential goods and services. Viet Nam issued tax exemptions for medical equipment and sped up registration of in-vitro diagnostic bio-products for COVID-19 testing, allowing for quick circulation of the tests which are approved by the WHO for use in Europe (OECD, 2020[17]); (ASEAN and OECD, 2020[61]). Viet Nam also supported the testing, evaluation, and circulation licensing for “Vsmart” respirators, the first of which was domestically manufactured only three months after announcing that production would commence. Myanmar similarly aimed to simplify and reduce administrative procedures while expediting approval processes for essential goods and services. Myanmar first focused on the health crisis for two months before launching a new working committee titled “COVID-19 Economic Relief Plan” (CERP). CERP’s mandate is to improve the country’s macroeconomic situation as well as ease the COVID-19 impacts on targeted sectors such as investment, trade, and banking. CERP has taken on a number of COVID-19 related regulatory policy roles, such as expediting regulatory and investment approval processes, simplifying regulations for medical products and infrastructure projects, waiving Food and Drug Administration (FDA) import requirements for products already FDA approved in other countries, and extending online applications. Thailand’s CCSA also supported the facilitation of the import and export of essential goods, particularly during the initial stage of the pandemic within the country.

Many SEA and OECD countries also temporarily cut and deferred fees and taxes to ease economic and regulatory burdens on businesses and households. Viet Nam has reduced electricity prices, cut taxes and extended payment due dates, and worked with commercial banks to temporarily suspend debt, provide credit interest reduction, and exempt and reduce fees such as the interbank transaction fees for small amounts and credit informal subscription fees (OECD, 2020[17]); (ASEAN and OECD, 2020[61]). Myanmar has also reduced some compliance costs and fees for businesses by as much as 30-75 %, allowed tax deferrals for enterprises, and exempted lease fee charges for affected businesses. Thailand implemented a cash handout policy including the “No one left behind scheme” to support most businesses forced to close with direct monthly credits to their bank accounts for a period of three months. Singapore supported its hard-hit tourism sector by waiving licence fees for hotels, travel agents and tour guides as well as by paying the cleaning charges for hotels that provided accommodation for confirmed and suspected cases of COVID-19 infections (ASEAN and OECD, 2020[61]). OECD countries have also implemented similar policies (OECD, 2021[62]). Chile, for example, granted more credits and the extension of state guarantees for loans to the private sector, along with tax relief, early income tax refund and postponement of income tax. Australia agreed to a nationally consistent approach to hardship support across the essential services for households and small businesses, and Germany extended the suspension of the obligation to file for insolvency as part of a broader package of reforms intended to support businesses.