Abstract

The slowdown of economic activity caused by the COVID-19 outbreak and related emergency measures implemented to tackle the health crisis have led to severe difficulties for companies to meet their financial obligations. Many of the fixed costs, such as rents and interest payments, remain due while the cash flow destined to meet these obligations has vanished. As a result, many otherwise sound companies are facing acute liquidity constraints that eventually might become solvency problems.1

A cascading approach of complementary measures to support viable businesses

In order to mitigate liquidity shortages and avoid unnecessary bankruptcies that may follow from the COVID-19 pandemic, national authorities can adopt a range of temporary measures. This policy note provides an overview of such measures that individually or in combination may be used to bridge the financing gap for the corporate sector and make sure that productive capacity is maintained to support the recovery. From a whole-of-government perspective, it is important to see these measures in the context of a cascading approach where governments and agencies can make successive or parallel use of different interacting tools.

First is the range of insolvency relief tools that exist in order to delay insolvency proceedings and gain valuable time to facilitate restructuring and corporate workouts.

Second and if additional support is needed, there is the possibility for state intervention that indirectly strengthens corporate cash flow. This can include help with the inflow of capital but also measures that help to decrease the outflow of capital, for example by a moratorium on certain tax payments. Such measures will further increase the means and the window of opportunity for the private sector to explore solutions, with respect to both debt and equity recapitalisation, keeping capital markets open.

Third, and if private solutions prove insufficient, there are various tools to provide direct state cash flow support. This can be both in the form of debt and equity. In the absence of ultimate market scrutiny, the presence of moral hazard and the risk of politicisation, the focus here should be to set terms that create strong incentives for both companies and governments to exit the temporary arrangements as recovery picks up.

As the different sets of tools in this framework may indeed interact, efficient interventions require that the incidence and effectiveness of the different elements of this cascading toolkit is well understood and kept in mind. The sequencing of the different types of interventions mentioned above may obviously vary depending on the specific circumstances. For example, while temporary insolvency relief might be important to avoid bankruptcies during the time when programmes for cash support are being developed, insolvency measures may also be useful at a later stage to promote the transfer of assets after the cash flow support programmes end.

Adjusting the insolvency framework

A temporary suspension of the obligation for companies to file for bankruptcy can be considered when the difficulties faced by the company are related to the COVID-19 outbreak.2 This can be complemented by a temporary moratorium that prevents a ‘rush to the exit’ behaviour and certain creditor actions against a company. The period of suspension and moratorium should be designed with a view to give the company management and creditors sufficient time to consider corporate workouts with respect to recapitalising, restructuring of debt or other alternatives.

Although the framework for director liabilities vary across countries, directors may typically be held accountable for incurring debt and making payments during a period when there is reasonable expectation that the company is insolvent or on the brink of insolvency. While such wrongful trading laws may be important during normal times to protect the interests of creditors, they may under current circumstances have the unintended effect to make directors overly risk averse and inhibit them to take actions towards a possible restructuring. A temporary relief of some of the director responsibilities, such as any personal liability for trading while insolvent, could be introduced to enable directors to take necessary actions to keep viable companies operational. For example, Germany has recently suspended the debtor`s duty to file for insolvency within three weeks after the directors realise that the company is expected or is already insolvent, effectively avoiding a great number of filings until the suspension expiries on the 30th of September. However, the relief should only be provided when the directors, acting on a fully informed basis and in good faith, consider that there is a prospect for the company to overcome liquidity constraints.

Some countries already have mechanisms that encourage debtors to reveal timely information about the company’s difficulties so that a consensual solution can be reached between the debtor and its creditors. The procedures and practical handling of such negotiations may have to be adapted to the capacity and availability of the judiciary and insolvency authorities during the COVID-19 outbreak.

In countries where a pre-insolvency framework does not exist or where the judiciary does not have the capacity to deal efficiently with an unusually large number of complex re-structuring processes, an alternative solution could be to create a possibility for a company to request in court (or to an insolvency practitioner, where the practice is well-regulated) a temporary moratorium if the company can argue that it is solvent and will likely survive the current crisis. This moratorium would not necessarily need to be linked to a restructuring plan. Another possible avenue could be to recognise that new financing during a pre-determined period should be granted priority over unsecured creditors. While this possibility exists in pre-insolvency frameworks it should be used with cautious when exceptionally applied to other systems as existing creditors may not have had reason to expect that it will be applied. However, in current circumstances when the risk aversion of lenders is acute, it could as a stand-alone procedure contribute to a constructive workout.

For EU member states, the Directive on restructuring and insolvency adopted in mid-2019 includes important elements to facilitate the restructuring of corporate liabilities. The Directive includes two features that are particularly relevant in the current crisis period: (i) a mechanism where the restructuring plan might be forced on dissenting creditors within a class and across classes of creditors and (ii) protection for new financing that comes in as part of the restructuring plan.

Where they exist, pre-insolvency frameworks supervised by the courts, such as the US Chapter 11, often work well for large companies, since they involve complex negotiations and sophisticated legal solutions. However, SMEs with a limited number of creditors may instead prefer to engage in out-of-court workouts without the intervention of the judiciary or public authorities. For such procedures, standardised reorganisation plans set out by law may still be useful for facilitating the restructuring of SME debts. This could allow adherence to a standard reorganisation plan – which would include pre-determined hair-cuts and deferral of payments to banks, landlords and suppliers – based on a simplified analysis of the firms` financial reports covering the period leading up to the crisis (e.g. interest coverage ratio and debt-equity ratio). While those objective cut-offs might not perfectly reflect the complexities of business viability, they may provide a relatively easy-to-verify proxy of which businesses were viable before the beginning of the crisis and, therefore, which ones will likely be viable in the economic recovery phase.

Lastly, it is important to note that there are market solutions that do not demand direct participation of the courts and other public authorities or a specific regulatory framework. Some investors specialise in acquiring bonds issued by companies in financial distress from institutions that do not themselves have the capacity or incentives to go through a long and complex restructuring processes. The business of those investors is to buy a significant part of the existing debt, effectively reducing the number of creditors and facilitate a consensual solution. However, such market based solutions may be impeded if the original creditors have strong incentives to avoid an adequate recognition of their credit loss in their balance sheets.

Dealing fairly with creditors to uphold market confidence

Bondholders and creditors are key corporate stakeholders and the terms, amount and type of credit extended to firms will depend on the enforceability of their rights. While extraordinary measures with respect to insolvency proceedings and liquidity support are in place, corporate boards should be expected to continue taking due regard of and deal fairly with creditors and provide the market with material information concerning their evolving financial situation. Temporary measures related to the COVID-19 outbreak should to the extent possible provide efficient mechanisms for reconciling the interests of different classes of creditors with different legal rights.

It is important that companies evaluate how the crisis will impact their operations in terms of liquidity and their ability to meet upcoming debt maturities under different scenarios. To plan ahead and develop scenarios is important since adjustment in the terms of the debt structure may be complex and require board approval. In addition, implementation of those adjustments may take longer for debt securities and certain types of loans with multiple counterparts. This may create difficulties in reaching consensus and flexibility on contractual terms and limit the company’s access to additional capital, restructuring or even ordinary business activities.

Indirect state support that reduce immediate cash outflows

The COVID-19 pandemic and related measures implemented by governments to tackle the health crisis have led to acute liquidity problems for businesses resulting from the twin shocks to demand and supply. To ensure that sufficient liquidity is available for companies, ensure continuity of business activity and prevent immediate insolvencies, governments may need to engage to indirectly support financially distressed firms.

Indirect government support could particularly target companies operating in sectors that are hard-hit due to the requirements for physical distancing in their businesses and include the deferral of taxes and social security contributions. Some governments have also implemented additional tax related measures to further amplify the support such as lowering the existing tax rates, waiving late-payment penalties and postponing enforcement measures relating to tax payments. In order to decrease the fixed costs of companies, further measures may include consideration of a rent holiday for commercial real estates that are owned by central or local governments or state-owned enterprises. Suspending utility payments such as gas, water and electricity or any type of due debt relating to the use of utilities of companies may also create further space for companies while governments would be able to compensate concessionaires according to existing contractual and statutory rules.

Governments can also target temporary policies to improve the conditions for bank lending to companies. In this respect, bank efforts to temporarily ease re-payments on credits could be encouraged by the government. Such support could extend to payment obligations to public sector-related credit schemes as well. In order to allow companies to continue financing themselves through banks, within the lending procedures, terminating borrowing fees and decreasing the procedural requirements related to borrowing could also be encouraged by governments.

Indirect government support measures may also include providing ‘technical’ support so that firm can rapidly adapt to the new business environment. This could include dedicated allowances for training, skills development programmes and business consultancy supports.

In order to provide companies with quick and efficient access to the available support measures, the administrative procedures for such programmes should be kept simple and transparent. The announcement and dissemination of information about programmes should be fostered and directed to companies by relevant bodies such as industry associations. Use of digital tools such as centralised registration systems where companies easily register for any type of support and where they can communicate with the relevant authorities will further ease the access for companies and increase the transparency of the procedures.

Keeping capital markets open

Corporate access to market-based finance will be of key importance on the road to recovery and resilience. Of particular importance is the ability of capital markets to strengthen corporate balance sheets with equity capital. Indeed, experiences from the 2008 financial crisis demonstrate that for already listed non-financial companies, raising equity capital through new stock offerings was a major source of capital. In 2009 alone, the capital raised through such secondary public offerings reached over USD 1 trillion worldwide and half of that money went to non-financial companies (OECD, 2019). In that same year, the amount of capital raised in the corporate bond markets reached USD 3.4 trillion and 51% of that money went to non-financial issuers (Celik, S. et al, 2020).

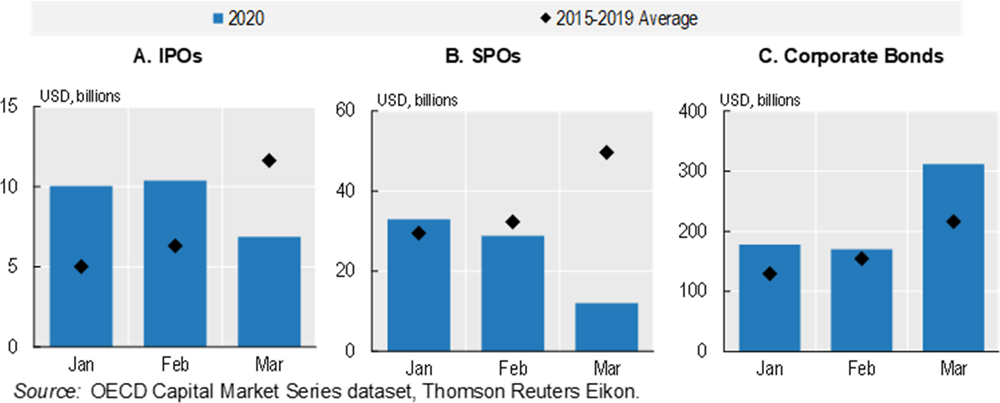

During the first months of 2020, listed non-financial corporations have also used primary markets to raise important amounts of capital. The total amount of equity capital raised by non-financial companies through initial public offerings (IPOs) was USD 27 billion during the first quarter of 2020 and the amount of capital raised in secondary public offerings (SPOs) was almost three times as much at USD 74 billion. However, mainly due to the substantial decreases across markets in March, both IPOs and SPOs have been considerably lower compared to the last 5-year averages (Figure 1, Panels A and B). At the country level, the most dramatic decline has been for the United States, where the total amount equity raised almost halved to USD 20 billion in Q1 2020 from USD 34 billion on average for the same period over the last five years.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, Thomson Reuters Eikon.

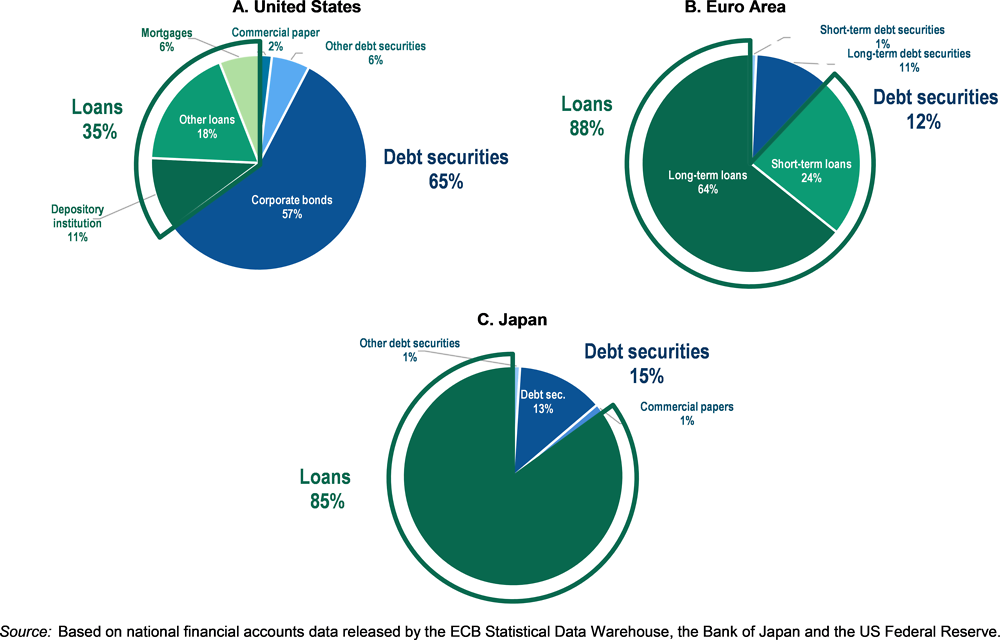

Debt securities markets, in particular long-term corporate bond markets, also represent a viable alternative for companies in search of capital. However already before the COVID-19 crisis, there were important differences in terms of the use of different types of debt financing. While companies from the US mostly use corporate bonds and other debt securities for financing, companies from Euro Area and Japan rely heavily on loans (Figure 2).

Source: Based on national financial accounts data released by the ECB Statistical Data Warehouse, the Bank of Japan and the US Federal Reserve.

During the first two months of 2020, issuance of corporate bonds by non-financial companies remained in line with the post‑financial crisis averages (Figure 1, Panel C). During March 2020, however, global issuance increased to USD 312 billion, compared to USD 216 billion on average in the past five years. The increase was mainly driven by US non‑financial companies, who issued an unprecedented monthly amount of USD 192 billion of corporate bonds. The issuance by Chinese companies also increased by 24% in March 2020 compared to the previous five‑year period average. However, only investment grade issuers were able to benefit from accessing financing from corporate bond markets and the total issuance of non-investment grade bonds almost vanished. On 9 April, the US Federal Reserve broaden the range of assets that are eligible for Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility to include ETFs whose primary investment objective is exposure to US high-yield corporate bonds. Following the announcement, US non‑financial high yield issuers were able to raise in April almost USD 32 billion.3 The ECB also announced late April that it will accept so-called “fallen angel” bonds that have recently lost their investment‑grade credit rating as collateral until September 2021.

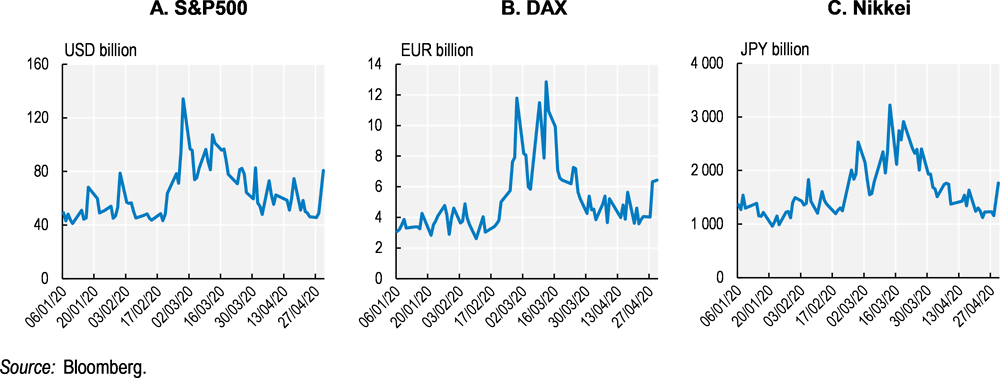

Secondary markets for equity and bonds play two main functions: liquidity and price discovery. Both functions become crucial in crisis times to allow investors to react to new information, reallocate their investments and be able to liquidate their holdings. More importantly, the price discovery function helps companies aiming to raise more capital on primary markets by providing a reference price for their securities. Volume traded in major stock markets over the recent months indicated that the activity in secondary stock markets continued to be strong during the initial crisis period (Figure 3). However, markets become one‑sided during the crisis-periods, meaning that all markets participants want either to sell or buy, resulting in increased price volatility. At the same time, short-selling activities may add additional downward pressure to stock prices as it allows investors to profit if stock prices drop. Several European markets limited short-selling on their stock markets. Despite the higher volatility observed in stock and bond markets around the world during the pandemic, keeping secondary markets open will be essential in order to ensure a consistent flow of information that will facilitate a healthy price formation process and provide savers with adequate access to their holdings.

Source: Bloomberg.

Given the important role capital markets could play in the recovery period, authorities may already consider short- and long-term measures to facilitate corporate access to market‑based finance. This can include easing administrative procedures, speeding up processes and creating a temporary possibility for “low doc” public offerings that will facilitate for companies to raise funds in the capital market. In addition, requirements could be eased further for instruments exclusively offered to qualified investors. As a result of the increased uncertainty in the current context, investors tend to look for shelter in high-quality securities leaving riskier but potentially innovative companies barred from raising new capital. Authorities may consider adapting specific frameworks to facilitate for companies with higher risk profiles to access market-based financing.

Today’s capital markets are global. On the road to recovery, it will be important that countries work together to ensure a smooth integration of capital markets, which will provide individual companies with access to a larger pool of capital and investors with extended investment opportunities. The G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance provides a global reference for this process through an alignment of standards and practices in areas such as transparency, the functioning of stock markets and the duties of corporate boards.

Direct state cash flow support

Given the uncertainty about the future economic conditions, the severe liquidity problem faced by the corporate sector and the limited ability of capital markets to be of immediate help for all companies, governments can also support the business sector through direct cash flow support. Considering the urgency, governments, agencies and state-owned financial institutions should act timely and provide flexibility with respect to the conditions and procedures for applications. Importantly, the design of direct financial support schemes for businesses should include mechanisms to incentivise all parties to wind down the schemes when economic conditions improve.

While large sums of money will be made available to overcome the corporate liquidity crisis, resources are still limited and need to be allocated among competing claims. For maximum efficiency, it is therefore essential that economic support or temporary regulatory lenience is extended to companies whose difficulties have verifiable links to the COVID-19 outbreak and a viable business plan after the pandemic is overcome. In this regard, it is important to note that what is viable in a sector in one country may not be viable in the same sector in another country, depending on the risk appetite of the debt and equity markets for those sectors. Moreover, support may not necessarily exclude companies with historical negative cash flows, such as start-ups that markets before the crisis assigned a positive net present value.

Direct cash flow support could be provided in many forms to ailing firms and the instruments governments decide to use will ultimately depend on the size of the company and their cash flows needs. To support companies with their short-term liquidity needs, governments may consider speeding up public sector payments to businesses including payments for contractors and refunds of excess input VAT. Some governments have also provided financial aid and/or subsidies to companies to help them keep employees on the payroll.

Within the corporate sector some corporations will be in need of greater amounts of cash and it will take longer for them to recover from this crisis. In these cases, governments can provide capital in the form of loans, guarantees, grants or equity capital injections. In particular, these types of support schemes should include terms that incentivise companies to request help only if needed and that the aid is used to maintain viable economic activity and jobs. Some governments have applied special conditions for accessing support schemes, such as a verifiable drop in revenues compared to the pre-pandemic period. Direct financial support to companies in the form of grants and direct lump sum subsidies could also help companies overcome the drop in revenue due to economic slowdown. While the general schemes for direct lump sum subsidies are mainly targeted at SMEs and/or self‑employed, the amount granted and the required conditions vary significantly among countries.

As many companies suffer from limited access to credit during a crisis period, governments may also consider the possibility to extend loans to ailing firms. Unlike bailout loans for smaller companies that could be offered at lower than market rates or even interest free, lending to larger companies could be done at rates closer to commercial rates. Such loans could still be an important relief if the company does not have access to other sources of financing. Governments may also consider introducing or extending guarantee measures to incentivise banks to provide credit to companies facing liquidity shortage. Under such a scheme, the state guarantees partial or full repayment of the loans in the case of default and thus enhances lender’s willingness and ability to extend credit. Some countries have introduced loan guarantee schemes specifically designed for SMEs.

For all of the temporary liquidity support measures, authorities should plan exit strategies. These should rely on strong incentives to keep company interests aligned with the state’s withdrawal. Support actions will be more credible when they are consistent with explicitly stated long-term goals, a clear strategy and a time-line for withdrawal.

Debt-for-equity swaps

Recently, some companies have reached an agreement with their investors on debt-for-equity swaps, which reduce the leverage ratio and also in some cases make the company eligible for government-backed loan guarantees. Since a typical debt-for-equity swap will dilute the holdings of the existing shareholders, its completion also requires an agreement from the company’s shareholders. Adjusting the legal framework to facilitate swap transactions for financially distressed firms could help protect the debtholders’ rights and at the same time strengthen the companies’ balance sheet with equity capital.

A key challenge in completing a debt-for-equity swap could be the difficulty in reaching a fair price of swaps acceptable to both shareholders and creditors. This is especially true when information asymmetries are high and/or negotiations involve numerous parties. Determining a fair price could be particularly difficult when the concerned company is privately held, lacking market evaluation. In such cases, a repurchase agreement can be structured, giving the option to investors to sell back their shares to the company at a given date. However, when dealing with companies affected by COVID-19 crisis, the period should be sufficiently long to allow a resolution of the liquidity constraints.

Special issues may announce themselves when creditors in a debt-for-equity swap end up with substantial ownership in a regulated industry. One option to address such concerns could be to establish a special purpose vehicle owned by a consortium of creditors to manage the ownership stake and oversee the divestment process. Another issue arises when the debt-equity swap concerns state loans or guarantees extended earlier as crisis support measures, in which case the swap turns the company into a state-owned (or state invested) enterprise.

When temporary state ownership is unavoidable

If no private investors can or will act to turn around an insolvent company, the state may choose to step in. An assessment should be made as to whether it is a case of ‘technical insolvency’ that can be overcome if the company continues operating as a going concern. In this case, the government may choose to inject equity assistance for instance in the form of convertible bonds, which typically can be converted into common stock at the bondholder’s discretion. While providing time for an orderly rescue, this may also ensure that the risk and potential rewards are shared between the state and the incumbent shareholders. The state may also consider joint capital injections with professional investors such as private equity firms or sovereign wealth funds. The expertise of experienced enterprise owners can be complementary, but care must be taken to ensure that the incentives of the public and private investors remain broadly aligned throughout the process.

In cases of unresolvable insolvency, governments may in some cases conclude that companies are too systematically important or too ‘strategic’ to either fail or fall into foreign ownership. Nationalisation may then be the only option. In this case, even if the government’s goal is to reprivatise as soon as possible, experience shows that temporary state ownership can be of some duration. It is therefore important that the state conduct its role as an active and informed owner according to the OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises. This will help ensure the efficiency and transparency of the enterprise and eventually pave the way for a smooth and value preserving divestment.

Conditionality of government support

Including commitments to internationally-recognised responsible business conduct standards, such as the OECD’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and related recommendations, can help ensure that benefits of fiscal support measures are shared equitably within society, and that large as well as smaller businesses receiving fiscal support from governments are appropriately managing environmental, social and governance risks related to their operations and supply chains.

Some governments have included specific conditions in their support programmes prohibiting or incentivising against laying off workers, for example schemes where the government provide income support when company maintains employees at reduced hours; requiring commitments to invest in worker skills and training, as well as requiring investments in disaster preparedness and supply chain security. Some governments have also asked companies that benefit from the state support programmes, such as deferral of social security contributions and guaranteed loans, not to distribute dividends or perform share buybacks for a certain period of time.

If the state becomes a significant owner as a result of corporate rescue programmes, it is particularly important that the state is mindful of broader policy priorities in the area of responsible business conduct. State could use its shareholding position to encourage environmental, social and governance standards in line with its international policy commitments.

Minimising risks of long-term market distortions

When designing indirect or direct state support measures, such as tax deferrals, subsidies and bank guarantees, governments should uphold sound market competition and ensure a level playing field between the companies that receive support and competitor that do not. This could be achieved by setting objective criteria and clear rules for state support that are applicable to all businesses in an industry.

Support that is directed to a specific company in an industry may prove more problematic from the competition perspective. To minimise such concerns it should be on a temporary basis and narrowly tailored to solve particular issues that are identified and declared. In particular, equity injections into individual companies should be considered if the company is insolvent as a direct result of the COVID-19 crisis; and it is too important to fail, for instance because its failure would trigger a disruption to the supply of essential goods and services. When state support results in ownership of the company by the state, the state needs to observe best practices of ‘competitive neutrality’ to ensure that no enterprise has undue advantages, or disadvantages, as a consequence of its ownership.

Governments should pay special attention to the potential risks associated with the provision of support and subsidies to sectors that are currently grappling with significant excess capacity, and which may see excess capacity increase in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. steel and shipbuilding). In particular, subsidies and other support measures by governments should not be used for purposes of increasing capacity or linked to production output and should not lead to long-term barriers that would hinder the exit of inefficient firms from excess capacity sectors when the economy eventually recovers.

References

Adalet McGowan, M. and D. Andrews (2018), "Design of insolvency regimes across countries", OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1504, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d44dc56f-en.

Çelik, S., G. Demirtaş and M. Isaksson (2020), “Corporate Bond Market Trends, Emerging Risks and Monetary Policy”, OECD Capital Market Series, Paris, www.oecd.org/corporate/Corporate-Bond-Market-Trends-Emerging-Risks-and-Monetary-Policy.htm

OECD (2020a), Competition policy responses to COVID-19, www.oecd.org/daf/competition/competition-policy-responses-to-covid-19.htm

OECD (2020b), Corporate sector vulnerabilities during the Covid-19 outbreak, www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/corporate-sector-vulnerabilities-during-the-covid-19-outbreak-a6e670ea

OECD (2020c), COVID-19 and responsible business conduct www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-and-responsible-business-conduct-02150b06/

OECD (2020d), Equity injections and unforeseen state ownership of enterprises during the COVID-19 crisis, www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/equity-injections-and-unforeseen-state-ownership-of-enterprises-during-the-covid-19-crisis-3bdb26f0/

OECD (2020e), Global financial markets policy responses to COVID-19, www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/global-financial-markets-policy-responses-to-covid-19-2d98c7e0/

OECD (2020f), Coronavirus (COVID-19): SME policy responses, www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/coronavirus-covid-19-sme-policy-responses-04440101/

OECD (2019), Equity Market Review of Asia 2019, OECD Capital Market Series, Paris, www.oecd.org/corporate/oecd-equity-market-review-asia.htm

OECD (2015a), “G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance”, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.oecd.org/corporate/principles-corporate-governance/

OECD (2015b), “Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises”, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.oecd.org/corporate/soes/

Contact

Mats ISAKSSON (✉ mats.isaksson@oecd.org)

Notes

See OECD (2020b) for more details on the risk of liquidity shortages for the corporate sector.

See more details on policies affecting the way failing firms can exit markets or be restructured in Adalet McGowen, M. and D. Andrews (2018).

OECD preliminary calculations based on Thomson Reuters Eikon.