Abstract

The unfolding COVID‑19 crisis is challenging people, households and firms in unprecedented ways. Containing the pandemic and protecting people is the top priority. But disrupted supply chains, containment measures that are limiting economic and social interactions and falling demand put people’s jobs and livelihoods at risk. An immediate employment and social-policy response is needed. Reducing workers’ exposure to COVID‑19 in the workplace and ensuring access to income support for sick and quarantined workers are essential. Working parents need help with unforeseen care needs as schools are closing and elderly relatives are particularly vulnerable. Short-time work schemes can help protect jobs and provide relief to struggling companies, as evidenced during the last financial and economic crisis. Workers who lose their jobs and incomes, including those in non-standard forms of employment, need income support. As companies are suffering from a sharp drop in demand, rapid financial support through grants or credits can help them bridge liquidity gaps. Many affected countries introduced or announced bold measures over the last days and weeks, often with a focus on supporting the most vulnerable who are bearing a disproportionate share of the burden. This note, and the accompanying policy table, contributes to evidence-sharing on the role and effectiveness of various policy tools.

The outbreak of the COVID‑19 virus poses an unprecedented, major challenge to economies and societies. The global economy faces its biggest danger since the financial crisis. Containing the epidemic and protecting people is the top priority. Reinforcing health systems and medical research to ensure that appropriate care can be provided to all those infected by the virus comes first; but governments also need to find fast and effective solutions to deal with the economic and social impact on workers and companies of both the disease itself and the effects of the containment measures taken to limit the spread of the virus.

This crisis is of a different nature than previous ones, and it requires a different mix and timing of policy responses. The spread of the COVID‑19 virus interrupted international supply chains, notably with China, and is forcing workers to remain at home because they are quarantined, sick or subject to lockdowns. Such a “supply shock” is very difficult to address with standard monetary and fiscal policy tools. As companies are finding themselves forced to interrupt and scale down operations, they lose the capacity to continue paying their employees’ wages. This threatens households’ incomes and, combined with growing uncertainty, reduces household consumption – a “demand shock” that will put further pressure on companies and their employees as well as on independent workers. In addition to fighting the public-health emergency, governments therefore have to move swiftly to provide employers and independent workers with liquidity and strengthen income support for workers and their families.

This note is a first attempt at setting out the employment and social-policy tools at governments’ disposal to counter the economic and social impact of the COVID‑19 crisis. Many of these measures are already being taken by countries around world; others will follow as the situation evolves over the coming days and weeks. This brief is therefore accompanied by an overview table of countries’ policy responses, available online, which will be continuously updated.

Reducing workers’ exposure to the COVID‑19 virus in the workplace

Many countries are taking measures to limit physical interaction. The first focus was on interpersonal interactions in the workplace and the daily commute, given that workplaces and public transport often gather large numbers of people and thereby increase their risk of contracting and spreading the COVID‑19 virus.

Relaxing existing regulations or introducing new options for teleworking.

Providing financial and non-financial assistance to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to help them quickly develop teleworking capacity and effective teleworking routines.

Encouraging employers’ organisations to inform their members of the benefits of telework and to offer assistance.

Collaborating with technology companies to provide SMEs and the self-employed with free and rapid access to communication and sharing tools.

Providing, or encouraging unions and employers to negotiate guidelines to reduce workers’ exposure in those workplaces where telework is not possible.

Besides calls to strictly follow sanitary guidelines, governments and employers have been encouraging prolonged “teleworking” which, with the right IT equipment, is possible in many workplaces. Indeed, teleworking has become increasingly common over the past decade or so. While some employers have been hesitant to promote it, it is now in their direct interest to reduce their employees’ exposure to the virus to limit sickness-related absences and maintain operations. Where a minimum staff presence at the workplace is required, “rotating” teleworking can be used. Employers can also reorganise work routines to limit interpersonal contact, e.g. by reducing office sharing and cancelling larger meetings. Some activities, however, will always require workers to be physically present, such as in the care, transport and retail industries, the energy sector and emergency services.

Regulations permitting teleworking exist in many OECD countries, both in law and collective bargaining; sometimes these are quite restrictive and may require an ex ante agreement by social partners. Such requirements can be eased. Italy for example simplified the procedure for teleworking: for the next six months, companies and employees can arrange teleworking without a prior agreement with unions, without a written agreement and at the employee’s place of choice. To ensure the health and safety of workers who cannot work from home, social partners have signed a binding agreement on the procedures to reduce workers’ exposure to the COVID‑19 virus in the workplace.

Governments are also providing different types of support to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to help them quickly develop teleworking capacities through financial assistance to purchase equipment and by supporting the development of suitable teleworking policies. In Japan, for instance, firms can now receive a subsidy of 50% (up to JPY 1 million) towards the cost of installing telework facilities. The Italian Ministry of Innovation has set up a website that provides an overview of the various available web-based tools that permit remote work and remote education (https://solidarietadigitale.agid.gov.it/). Some large tech companies, including Amazon Web Services, Cisco, Dropbox and Google, provide temporary free-of-charge access to some of their communication and sharing tools to companies and workers.

In some countries, and for some groups, poor housing conditions may make it difficult for people to self-isolate and can make effective teleworking impossible. In the face of an infectious disease like COVID‑19, overcrowding can be particularly problematic as it prevents physical distancing and facilitates the spread of the disease when a household member gets sick. More than a quarter of all households in Latvia, Mexico, Poland and the Slovak Republic live in overcrowded conditions. Also, up to a quarter of households in ten OECD countries do not have a personal computer; in Turkey and Mexico, fewer than half of households have access to a computer at home.

Providing income replacement to sick workers and their families

Paid sick leave is a crucial tool for addressing the economic impact of the COVID‑19 crisis for workers and their families. It can provide some income continuity for workers who are unable to work because they have been diagnosed with COVID‑19 or have to self-isolate. By ensuring that sick workers can afford to remain at home until they are no longer contagious, paid sick leave also helps to slow the transmission of the virus.

Extending paid sick leave coverage to non-standard workers, including the self-employed.

Extending the duration of paid sick leave or waiving waiting periods and aligning them with quarantine and medical recommendations.

Adapting reporting requirements to access paid sick leave, e.g. by waiving the need for medical certification.

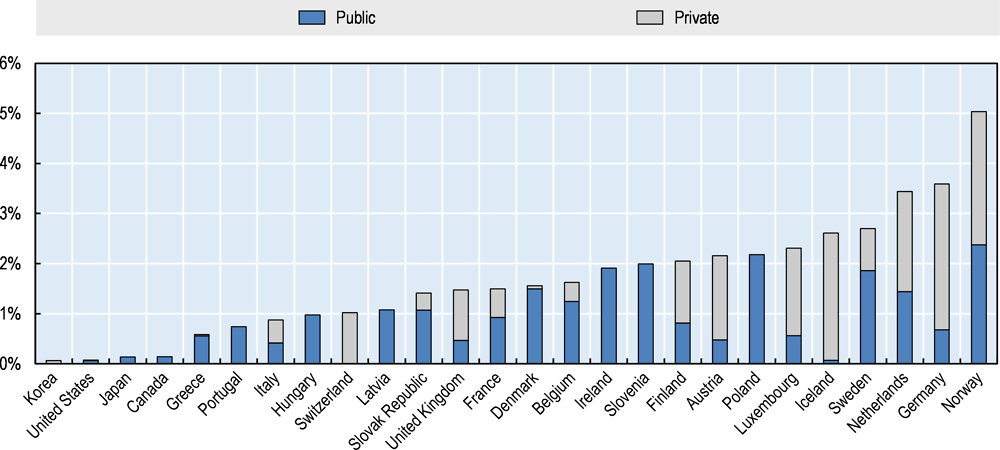

Most OECD countries provide workers with financial compensation during sick leave. Often, the initial period is covered by the employer, in the form of continued wage payment for a period of 5-15 days in most OECD countries, but up to several weeks or months, e.g. in Austria, Germany or Italy and even 2 years in the Netherlands. In addition, almost all OECD countries provide publicly paid income support for sick workers that can extend far beyond employers’ liabilities, for up to one year in many OECD countries and even longer than this in some. The level of compensation during sick leave is high in many countries, typically replacing around 50-80% of the last wage, and even up to 100% in countries like the Netherlands and Norway. In countries with the most generous systems, total spending on paid sick leave, including employer payments and public sickness benefit, sums to 3% of total employee compensation or more (see Figure 1).

Note: Data on private spending are likely of lesser quality than information on budgetary allocations. This holds in particular for data on non-mandatory employer-provided sick pay (as stipulated in individual employment contracts and/or in enterprise or other collective labour agreements). Voluntary employer-provided sick pay is not subject to reporting requirements and estimates of their magnitude may not be available on a comprehensive basis. As a result, estimates presented here understate the true extent of privately provided sick pay and by extension total spending on sick pay in countries where workers largely have to rely on such employer-provided benefits, as for example in Canada and the United States.

Source: Calculations based on the OECD Social Expenditure Database, http://oe.cd/socx.

However, in some countries, sick-leave compensation only covers a small fraction of the previous wage and / or is shorter than the recommended period of self-isolation for people with COVID‑19 symptoms. For instance, Korea and the United States have no generally applicable statutory obligations for employers to continue wage payments in case of illness and also do not provide for statutory public sickness benefits (OECD, 2018[1]). Comprehensive spending data on employer-provided sick pay is not available for the United States, but a quarter of U.S. workers do not have access to paid sick leave at all (rising to one half for low-wage workers), and two thirds of workers who do accrue less than 10 days of paid sick leave per year (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019[2]). With the “Families First CoronaVirus Response Act”, the United States introduced two weeks of paid sick leave for workers impacted by the COVID‑19 virus, which will initially be paid by employers but be fully reimbursed by the federal government.

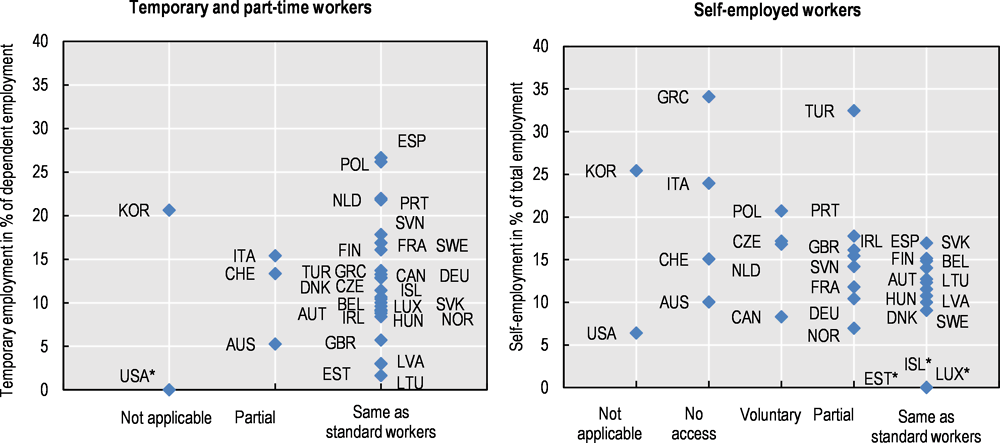

In many countries, access to paid sick leave is limited for non-standard workers. Heavy reliance on voluntary employer provisions can mean lower coverage in part-time jobs and for employees on short-time contracts. These gaps are a concern particularly when health risks are elevated for these groups, e.g., because of greater exposure to infection risks in the service sector. In Australia for example, self-employed and casual workers are not entitled to sick pay. But gaps affect public provisions as well, especially for self-employed workers (see Figure 2). In the Netherlands, they do not have to be insured against temporary income loss caused by illness; they can opt for private insurance but only a minority do so. They can, however, receive an income supplement, up to the level of regular social assistance or a zero-interest loan. In Italy, self-employed workers do not have any statutory sickness insurance, although some may be covered by occupational schemes. For temporary workers, maximum sickness benefit durations are typically shorter than for those on permanent contracts because the benefit duration is often limited by the end date of the temporary contract. For temporary workers in Italy, the benefit duration also depends on days worked in the past year (which is not the case for permanent employees).

In some countries, sickness benefit coverage is mandatory for self-employed workers with incomes above a certain minimum (for others, coverage may be voluntary). But maximum entitlement periods may be shorter and waiting periods much longer for self-employed than for dependent employees, e.g. 10 days in Portugal (3 days for employees), and 7 days in France (3 days for employees).

Governments have been adopting a series of measures to replace incomes for sick workers during the COVID‑19 crisis. Portugal waived the waiting period for self-employed workers on sickness benefit. The United Kingdom announced that it will abolish the three-day waiting period for employer-provided statutory pay as well as the one-week waiting period for an allowance is payable to low earners and the self-employed. In Austria, people who may have COVID‑19 are not required to send a sickness certificate because Austrian policy is very strict on not going to a doctor or hospital to avoid spreading the virus. Also, for workers on sick leave with COVID‑19, employers get their continued wage payments reimbursed after ten days of absence while they have to continue wage payments for up to 12 weeks for normal sick leave. In Germany, according to existing legislation aimed at curbing the spread of infectious diseases, the self-employed can claim an income replacement benefit at a level of their declared earnings in the previous tax year.

The private sector too has been taking action. Some companies are providing their employees with paid sick leave to allow those who feel ill to stay home.

Note: Gaps between standard dependent employees (full-time open-ended contract) and self-employed / temporary and part-time workers. Sickness benefits refers to income replacement (not access to health-care). “Partial” access can arise if a) eligibility conditions, benefit amounts or receipt durations are less advantageous for non-standard workers; b) insurance-based and non-contributory benefits co-exist and individuals can access only the latter; or c) non-standard workers can choose to declare a lower contribution base while standard workers pay contributions on full earnings (possibly subject to a ceiling). “No access”: compulsory for standard workers but non-standard workers are excluded. Not applicable: no compulsory sickness benefit schemes in the US and Korea. No information on part-time and temporary workers for Japan. * Data on self-employment incidence is missing/incomplete for Estonia, Iceland and Luxembourg and refers to 2015 for the Slovak Republic and to 2014 for Latvia. Data on the incidence of temporary employment is missing for the US.

Source: Australia: Whiteford and Heron (2018[3]), European countries: adapted from Spasova et al. (2017[4]), Canada, Japan, Korea: Information provided by country delegations to the OECD, USA: SSA and ISSA (2018[5]). Share of self-employment in total employment, temporary workers in percent of employees: OECD (2018), “Labour Force Statistics: Summary tables” and OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database).

Providing income replacement to quarantined workers who cannot work from home

In order to contain the spread of the COVID‑19 virus, most OECD countries introduced quarantine requirements for workers returning from high-risk countries or who have been in close contact with people who show symptoms or have been diagnosed. An increasing number of OECD countries are on lockdown. While some workers may be able to continue working while being in self-isolation at home, many cannot.

Adapting regulations to ensure that quarantined workers have access to paid sick leave.

Reimbursing employers if they provide paid sick leave to quarantined workers.

Ensuring that non-standard workers in quarantine receive support.

The legal situation of workers in mandated quarantine who cannot work from home differs across countries. In some countries, quarantined workers are covered by sick pay. In Austria and Germany, for instance, existing legislation treats quarantined workers who cannot work from home as on sick leave, i.e. they continue to receive their salary (for 4-12 weeks in Austria, for 6 weeks in Germany). In the Netherlands, quarantined workers generally continue to receive their usual pay from their employer, though this may depend on the reason for the quarantine (following professional travel or holidays) and the type of employment contract. The United Kingdom announced making statutory sick pay available to all workers who are advised to self-isolate because of the COVID‑19 virus even if they have not displayed symptoms. In some countries such as Belgium, France and Netherlands, quarantined workers who cannot work from home may be covered by short-time work schemes that are made available in the case of force majeure.

In light of the potentially high costs to employers and large public-health benefits, countries have been supporting employers in shouldering the cost of the absence of workers: in Germany, employers can claim continued wage payments back from regional authorities. The situation in Austria is similar. The United Kingdom announced that companies with fewer than 250 employees will be able to claim refunds for statutory sick pay paid to staff off work because of COVID‑19 for a period of up to 14 days. In Portugal, quarantined workers will receive sickness benefits paid by social security at a level equivalent to their wages.

The self-employed face much greater income insecurity if they have to quarantine, except in countries with specific provisions for such cases. In Germany, income replacement for the self-employed extends beyond those who are sick to those with a justified reason for quarantine.

Helping workers deal with unforeseen care needs

The large-scale closure of childcare facilities and schools now implemented in an increasing number of OECD countries can cause considerable difficulties for working parents who have to (arrange) care during the working day. A further complication is that grandparents, who are often relied on as informal care providers, are particularly vulnerable and are required to minimise close contact with others, notably with children.

Offering public childcare options to working parents in essential services, such as health care, public utilities and emergency services.

Publicly providing alternative care arrangements.

Offering direct financial support to workers who need to take leave.

Giving financial subsidies to employers who provide workers with paid leave.

Adapting telework requirements to workers’ caring responsibilities in terms of working hours and work load.

Teleworking full office hours can be very difficult if not impossible in practice, notably for families with young children, couples where only one partner can telework and single parents. In particular lower-skilled, lower-paid occupations are less likely to be able to work from home (OECD, 2016[6]), but may also not be able to afford buying in external care solutions (e.g. private childminders), where these are available.

Working parents may be able to request leave from work. In the short term, they might be able to use statutory annual leave, although this often remains at the discretion of the employer. In the United Kingdom, for example, workers must provide their employers with notice before they take leave, and employers can restrict and/or refuse to give leave at certain times. In the United States, at the national level, workers have no statutory entitlement to paid annual leave at all.

Parents’ rights to take additional time off in the case of e.g. school/facility closure are often unclear. Almost all OECD countries provide employees with an entitlement to leave in order to care for ill or injured children or other dependents (OECD, 2020[7]). In some countries, parents have a right to a leave in case of unforeseen closures (e.g. Poland and the Slovak Republic) or other “unforeseen emergencies” (e.g. Australia and the United Kingdom), which would likely include sudden school closure. Others (e.g. Austria, Germany) have recently clarified that existing emergency leave entitlements will apply in cases of school or childcare facility closure. However, these rights sometimes extend only as far as unpaid leave, with the decision to continue payment of salaries typically left to the employer. Many parents may be unable to afford taking unpaid leave for any length of time. Moreover, in some countries (e.g. Austria, Germany and the Slovak Republic), these leaves (or the right to payment during leave) are time-limited, while in others, it is unclear how long these rights would continue to apply.

Some countries have begun implementing emergency measures to help working parents in cases of closure of schools or childcare centres. In several countries where childcare facilities and schools have been closed (e.g. Austria, France, Germany and the Netherlands), some facilities remain open, with a skeleton staff, to look after children of essential service workers, notably in health and social care and teaching. In France, for example, childcare facilities for such families can host up to 10 children, and childminders working out of their homes may exceptionally receive up to 6 rather than 3 children. In the Netherlands, the list of essential occupations also includes public transport, food production, transport and distribution, transportation of fuels, waste management, the media, police and the armed forces and essential public authorities.

Countries are also offering financial support to help with the costs of alternative care arrangements. In Italy affected working parents with children below 12 have the possibility to take 15 days of leave, paid at 50% of the salary or unpaid for parents with children above 12. Alternatively they can have a voucher of EUR 600 (EUR 1 000 for medical workers) for alternative care arrangements. This possibility is open to both employees and the self-employed. France has stated that parents impacted by school closure and/or self-isolation will be entitled to paid sick leave if no alternative care or work (e.g. teleworking) arrangements can be found. Portugal announced that parents with children below the age of 12 who cannot work from home and whose children are affected by school closures receive a benefit of two-thirds of their monthly baseline salary, paid in equal shares through employers and social security. Self-employed workers can claim one-third of their standard take-home pay.

A further measure is financial support to employers who provide workers with paid leave. In Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has announced a subsidy to firms that establish their own paid-leave systems for workers affected by school closures. Employers will be compensated for the continued payment of salaries while workers are on leave up to a limit of JPY 8 330 per person per day.

Workers with elderly dependents may face an equally pressing need for time off. Several OECD countries provide workers with a statutory right to leave to care for parents or adult relatives with a serious or critical illness (e.g. Austria, Germany, Korea, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom), often unpaid. However, these rights would likely apply in cases where relatives develop serious symptoms, but it is not clear whether they extend to elderly relatives with (initially) mild symptoms or those self-isolating. Moreover, even where a statutory right applies, workers are often required to provide notice before taking leave which may not be practical where a relative requires urgent care.

Securing workers’ jobs and the economic viability of firms

In light of the enormous challenge that firms across all sectors are facing in dealing with a combined supply and demand shock, immediate measures are needed to secure jobs and incomes and grant firms flexibility to quickly recruit staff replacements, where necessary.

An important lesson learned from the 2008 global financial crisis is the positive role that short-time work (STW) schemes can play in mitigating the economic and social costs of major economic crises (OECD, 2010[8]; 2014[9]; 2018[10]). STW schemes seek to preserve jobs at firms that experience a temporary drop in demand. They provide public income support to workers whose working hours have been reduced or who have been temporarily laid off while firms maintain their contract with an employee during the period of STW or the suspension of work. This permits employers to hold on to workers’ talent and experience and enables them to quickly ramp up production once economic conditions recover.

Introducing, extending and temporarily relaxing participation and conditionality requirements in short-time work schemes.

Simplifying procedures and provide easy access to online information for employers.

Promoting the uptake of online training to invest in the skills of employees during the downturn.

Facilitating rapid recruitment of staff to replace sick workers in core functions.

Most OECD countries operate STW schemes. Institutional differences relate, amongst others, to the conditions for participation (e.g. economic justification, social-partner agreement, unemployment benefit eligibility), the conditions for their use (e.g. recovery plan, training, job search) and the way the costs of STW are shared between governments, firms and workers. The challenge for policy makers is to strike the right balance between ensuring adequate take‑up and maintaining cost‑effectiveness, i.e. limit the extent to which jobs that would have been preserved anyway or are unviable even in the long-term are unduly subsidised.

The main priority in the current context is to promote rapid take-up of STW. This requires clear and easily accessible online information on how to use STW schemes, as well temporarily relaxing participation and conditionality requirements.

A number of countries have taken recent steps to expand STW and facilitate access. Germany simplified access to Kurzarbeit. Firms can now request support if 10% of their workforce are affected by cuts in working hours, compared to one third before. In addition to compensating 60% of the difference in monthly net earnings due to reduced hours, the labour agency will now also cover 100% of social insurance contributions for the lost work hours. This is an increase compared to the financial crisis, when only 50% of social insurance contributions were subsidised and employers had to cover the other half. Germany also extended the Kurzarbeit to cover temporary/agency work hence pre-empting greater labour market segmentation.

Italy has extended short-time work (Cassa Integrazione Guadagni) to all sectors and companies for up to 9 weeks. Japan expanded the coverage and eased the requirement of its short-time work scheme, the Employment Adjustment Subsidy (EAS). Previously, one of the conditions for EAS was a 10% reduction of production for more than three months; now this period has been reduced to only one month. In addition, in regions in “state of emergency” (currently only in Hokkaido) this requirement is regarded as satisfied regardless of firms’ production or sales, the subsidy rate is increased, and non-standard workers are also covered.

Korea also relaxed the requirements for its employment retention subsidy programme. It also raised for six months the level of the wage subsidy that companies can claim if they keep their employees on paid-leave or leave-of-absence programmes, from half to two thirds of the wage paid for large companies, and from two thirds to three quarters of the wage paid for SMEs. Portugal announced a “temporary lay-off scheme”, permitting companies in economic difficulties to retain their staff, with employees continuing to receive two thirds of their pay, 70% of which will be covered through social security. The Danish Government agreed with the social partners to cover 75% of workers’ salaries in companies hit by the crisis up to a maximum threshold if the companies continue to pay the remaining 25% rather than to lay off workers. Employees contribute by taking five days of mandatory annual leave. France unified and simplified its STW schemes and expanded them to all workers, with a replacement rate of 84% of the gross wage (100% if the workers participate in training or are paid at the minimum wage) fully covered through the general budget, instead of targeting the schemes to workers around the minimum wage. In some countries, such as Belgium, France, and the Netherlands, existing short-term work schemes can be extended to apply in the case of a force majeure, covering people placed in quarantine or companies affected by an epidemic.

During the period of stoppage, companies could promote the uptake of online training to invest in the skills of employees. France, for instance, is encouraging firms to use a special training subsidy, the FNE Formation, instead of traditional STW. FNE Formation had originally been developed for companies undergoing structural changes that needed to re- skill or upskill their workforce.

France and Italy have also introduced limitations to economic dismissals to force companies to use the expanded STW schemes instead of laying off workers. Such measures can reassure workers in a period of already strong anxiety, limit opportunistic behaviours of few employers who may use the crisis as an excuse to dismiss “difficult” workers and avoid the social stigma of being fired. However, they may also lead to a few company bankruptcies if access to STW schemes for firms turns out to be incomplete, impractical or too costly. Moreover, if limitations to economic dismissals are not rapidly lifted once the epidemic is over, they may inhibit restructuring processes and slow down the recovery. Some workers may get locked in unviable companies instead of being taken care of by public employment services that could offer re-training and other support.

The rapidly rising count of workers who are sick, quarantined or absent from work to care for their children also risks undermining the functioning of essential economic sectors, notably in health and long-term care and transportation. Measures may therefore be needed to facilitate the rapid recruitment of temporary staff that can take over core functions, e.g. tailored exemptions to regulations that limit hiring of workers on temporary contracts and/or targeted incentives for workers that take up these jobs despite the health crisis.

Providing income support for those losing their job or their self-employment income

The COVID‑19 crisis puts jobs and livelihoods at risk in the short to medium term, both because of disrupted supply chains and falling demand. In addition, workers who do not have access to adequate leave in case of sickness or caring responsibilities may have to cut down their activities or even leave their jobs entirely. Further, rising economic insecurity may undermine some households’ capacity to pay their rent, make monthly mortgage payments, or cover the cost of utilities. During a period where many governments are asking people to “shelter at home”, support measures to ensure that households can remain in their dwelling are especially important.

Extending access to unemployment benefit to non-standard workers.

Providing easier access to benefits targeted at low-income families.

Considering one-off payments to affected workers.

Reviewing the content and/or timing of reforms restricting access to unemployment benefits that are already scheduled.

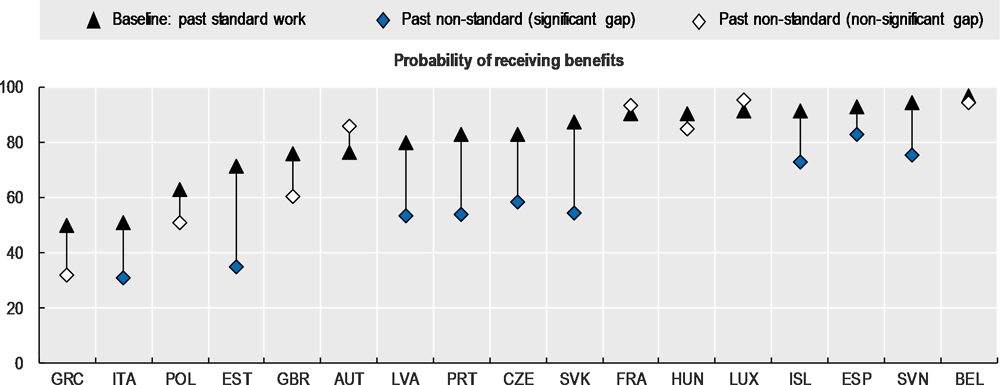

Helping economically insecure workers stay in their homes by suspending evictions and deferring mortgage and utility payments.

Unemployment benefits and related income support are crucial for cushioning income losses. But not all job losers have access to such support, which is especially problematic if health insurance is tied to employment or benefit receipt. Recent OECD analysis (OECD, 2019[11]) shows that, prior to recent and forthcoming policy reforms, income support for “standard” workers (those with past continuous full-time work) was relatively accessible in France, Luxembourg, Iceland, Spain, Slovenia and Belgium, with 90% or more receiving at least some support following a job loss. Support was less accessible in Estonia, United Kingdom, Austria, Latvia, Portugal, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic, but the likelihood of receiving support was still above 70% in these countries. In Poland, Greece and Italy, even standard workers had a significant risk of not receiving any support following a job loss (Figure 3).

Workers in non-standard forms of employment are, on average, significantly less well protected that workers in standard forms of employment against the risk of job or income loss. In some countries, such as the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Portugal and the Slovak Republic, workers engaged in independent work, short-duration or part-time employment are 40-50% less likely to receive any form of income support during an out-of-work spell than standard employees. Even where non-standard workers receive support, they often receive much lower benefits than standard employees, for example in Greece, Italy, Slovenia and Spain.

Note: Predicted benefit receipt during an entire year comparing: i) an able-bodied working-age adult who is out of work, had uninterrupted full-time dependent employment with median earnings in the preceding two years, and lives in a two-adult low-income household without children (“baseline: past-standard work”, triangle-shaped markers); and ii) an otherwise similar individual whose past work history is “non-standard”: mostly in part-time work, mostly self-employed, or interrupted work patterns during the two years preceding the reference year (“past non-standard”, light and dark diamond-shaped markers). Additional results for different categories of non-standard work are available for some countries.

Statistical significance refers to the gaps between baseline and comparator cases (90% confidence interval). Full-time students and retirees are excluded from the sample. Details on data and model specification are summarized in Box 7.3 and presented in further detail in Fernández, Immervoll and Pacifico (forthcoming[12]). The data source, the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) covers additional countries but they are excluded here because effective sample sizes were small (e.g. Ireland, Lithuania), because the required micro-data were entirely unavailable (Germany), because key employment-status variables are recorded only for one individual per household (Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands and Sweden), or because of partial or partly conflicting information on income or benefit receipt (Norway).

Source: OECD (2019[11]), OECD Employment Outlook 2019: The Future of Work, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9ee00155-en.

Already before the COVID‑19 crisis, many countries were exploring how to shore up access to out-of-work benefits in the context of changing working arrangements. For instance, Austria, Canada, France and Spain have extended entitlement to unemployment benefits to independent workers. Denmark has also strengthened the portability of earned entitlements across different jobs and forms of employment. Italy has facilitated access to means-tested safety-net benefits.

Additional temporary emergency measures may be needed to provide urgent and easy-to-access income support during the COVID‑19 crisis. Several countries have announced initiatives, which are sometimes modelled on the initial responses to the global financial crisis in 2008/09 (OECD, 2014[9]).

One focus has been on easing access to benefits targeted to low-income families. The United Kingdom has announced that self-employed workers with low earnings will have more ready access to the main means-tested programme (Universal Credit), and a new hardship fund for local authorities is to support vulnerable people in their area.

Another option is to make one-off payments to workers in urgent need. In France, for example, during the global financial crisis, a temporary lump sum payment of EUR 500 was paid directly by the public employment service to workers who lost their jobs but were not eligible to unemployment insurance. Australia has announced that 6.5 million lower-income Australians with benefit entitlements will receive a one-time lump-sum payment of AUD 750. In Italy, some self-employed workers will receive a lump-sum payment for the month of March of EUR 600.

Governments may also want to review the content or timing of reforms that are already scheduled. In France, for instance, the 2019-20 reform of the unemployment insurance tightens minimum contribution eligibility conditions, from 4 to 6 months of work over a 24-month period, and limits replacement rates for workers on fixed-term contracts. Since those workers are not only most at risk of losing their jobs but also less likely to benefit from other forms of protection, such as STW schemes, the reform has been partly postponed for several months. In the United States, access to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, previously “food stamps”) was due to be tightened in April.

Public employment services may need to adapt procedures for claiming benefits, the delivery and composition of active labour market policies and the application of activation criteria. Benefit applications by phone, email or online should quickly become the norm during the current health emergency. Remote benefit claims are already possible in most countries, but several of them still require applications to be made in person.1 Germany cancelled all personal interview appointments for jobseekers; the Estonian and Belgian public employment services now offer online job search counselling and job mediation. Likewise, the provision of employment measures has to be halted, especially if these take place in groups (such as training or job clubs), in favour of online courses and virtual group counselling.

Countries are also implementing responses to ensure that households can remain in their dwelling if they struggle to cover rent, mortgage or utility payments due to a job or wage loss. Several (Italy, Spain, the Slovak Republic and the United Kingdom) have introduced temporary deferments of mortgage payments; others temporarily suspended foreclosures (United States) or evictions (France, Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States, and some Canadian regions and municipalities). Through a change in legislation, Greece is temporarily allowing tenants whose employment contract has been suspended because of the COVID‑19 crisis to pay only 60% of their monthly rent on their main residence in March and April. Japan is allowing households affected by COVID‑19 to postpone payments on utility bills if needed. Some countries have introduced measures to support the homeless, who are especially vulnerable to the spread of COVID‑19 and lack the ability to effectively “shelter in place”: France, for instance, has requisitioned hotel rooms to be used by the homeless during the lockdown.

Providing financial support to firms affected by a drop in demand

Besides means of quickly adjusting staff numbers, many firms will require financial support. This applies in particular to small businesses and the self-employed, including shops, restaurants and the cultural sector.

Deferring tax and social contribution payments.

Setting up financial facilities to temporarily support companies’ liquidity.

Several countries have taken rapid steps to help firms to cut costs or to provide them with liquidity by permitting a deferral of tax and social contribution payments. Australia, for instance, announced a package to reduce the financial burden to SMEs including changes in depreciation rules and the possibility for businesses hit hard by the downturn to defer tax obligations. Denmark announced to provide a credit facility of DKK 125 billion (5% of GDP), allowing firms to postpone VAT and tax payments. The United Kingdom will abolish taxes on small retail or hospitality business properties for a year. Germany has made it easier to grant tax deferrals, to adapt tax prepayments and has waived enforcement measures and late-payment penalties until the end of the year if the debtor of a pending tax payment is directly affected by the COVID‑19 crisis.

Many countries have also been responding by offering public grants and emergency credits. Australia will provide temporary liquidity support to small and medium businesses with employees affected by the COVID‑19 crisis of up to AUD 25 000, which is predicted to benefit around 690 000 businesses. The United Kingdom announced an emergency business loan scheme that provides lenders with an 80% government guarantee for loans made to SME and that covers SMEs’ interest payments and fees for up to 12 months. The UK Government also announced GBP 3 000 cash grants to all small businesses, which amounts to a total pay-out of GBP 2 billion. Italy and Germany will expand existing liquidity assistance programmes to make it easier for companies to access cheap loans.

A number of countries have also announced refunding firms for the costs of sick pay to staff who are off work because of COVID‑19, see above.

Providing financial support to firms also requires the mobilisation of the financial sector and the support of central banks, measures that are beyond the scope of this brief. Other specific measures for SMEs can be found in the note by the OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities (CFE) [available online].

References

[2] Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019), Paid Leave Benefits, https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2019/benefits_leave.htm.

[12] Fernández, R., H. Immervoll and D. Pacifico (forthcoming), “Beyond repair? Anatomy of income support for standard and non-standard workers in OECD countries”, OECD Employment, Social and Migration Working Papers, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[13] Immervoll, H. and C. Knotz (2018), “How demanding are activation requirements for jobseekers”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 215, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/2bdfecca-en.

[7] OECD (2020), OECD Family Database, http://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm.

[11] OECD (2019), OECD Employment Outlook 2019: The Future of Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9ee00155-en.

[10] OECD (2018), Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work: The OECD Jobs Strategy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264308817-en.

[1] OECD (2018), Towards Better Social and Employment Security in Korea, Connecting People with Jobs, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264288256-en.

[6] OECD (2016), Be Flexible! Background brief on how workplace flexibility can help European employees to balance work and family, http://www.oecd.org/els/family/Be-Flexible-Backgrounder-Workplace-Flexibility.pdf.

[9] OECD (2014), “The crisis and its aftermath: A stress test for societies and for social policies”, in Society at a Glance 2014: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/soc_glance-2014-5-en.

[8] OECD (2010), OECD Employment Outlook 2010: Moving beyond the Jobs Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2010-en.

[4] Spasova, S. et al. (2017), Access to social protection for people working on non-standard contracts and as self-employed in Europe, European Commission, Brussels, http://dx.doi.org/10.2767/700791.

[5] SSA and ISSA (2018), Social Security Programs throughout the World: The Americas, 2017, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/progdesc/ssptw/2016-2017/americas/ssptw17americas.pdf.

[3] Whiteford, P. and A. Heron (2018), “Australia: Providing social protection to non-standard workers with tax financing”, in The Future of Social Protection: What Works for Non-standard Workers?, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264306943-5-en.

Overview table

A table with countries’ policy responses is available at the following link: http://oe.cd/covid19tablesocial.

Contact

Stefano SCARPETTA (✉ stefano.scarpetta@oecd.org)

Monika QUEISSER (✉ monika.queisser@oecd.org)

Andrea GARNERO (✉ andrea.garnero@oecd.org)

Sebastian KÖNIGS (✉ sebastian.koenigs@oecd.org)

Note

See Table 3 in Immervoll and Knotz (2018[13]).