Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to affect agricultural markets over the next decade. OECD analysis highlights how slower economic growth could affect food security, farm livelihoods, greenhouse gas emissions, and trade. The size of these impacts depends, among other things, on the severity of the drop in global GDP. Based on two scenarios for economic growth recovery, this brief describes how the economic shock from the pandemic could reverberate through the agriculture sector over the next decade.

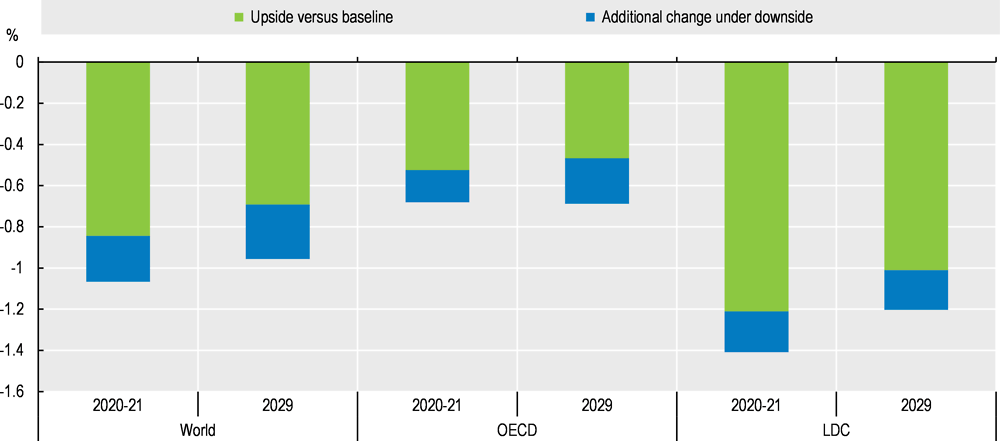

Falling incomes lead to a contraction in food consumption, and these impacts are larger in LDCs

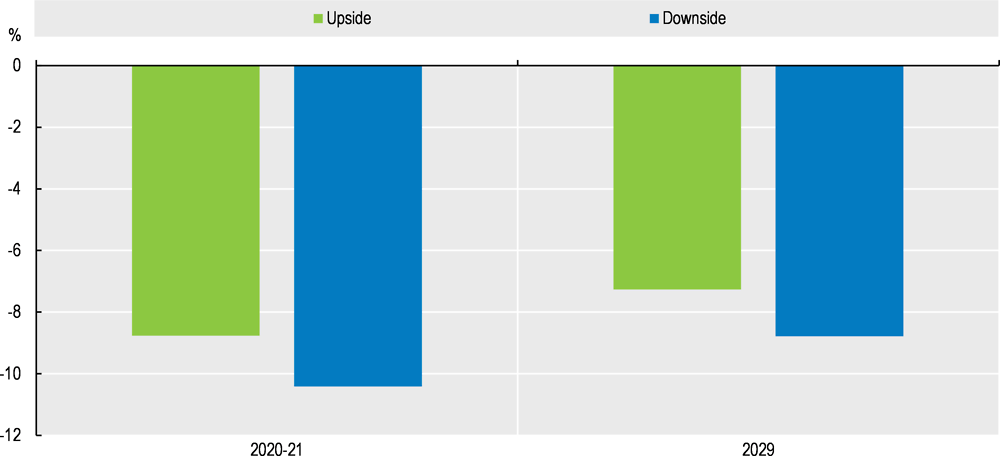

Our analysis shows that lower economic growth will reduce overall food consumption. Falling incomes lead to a decrease in calorie demand per capita. 1 2 Projections indicate that calorie demand per capita could fall by 1% globally, compared to baseline levels, in both 2020-2021 and 2029 (Figure 1). These impacts are exacerbated in least developed countries (LDCs) since these countries spend a larger share of their incomes on food. Although in absolute terms the reduction in calorie demand in LDCs is lower than in other countries, the projected percentage decline in gross calorie demand in LDCs is about two to three times higher than in OECD countries in 2020-21 and this effect is expected to be maintained over the medium term.

Source: OECD/FAO (2020), “OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-outl-data-en.

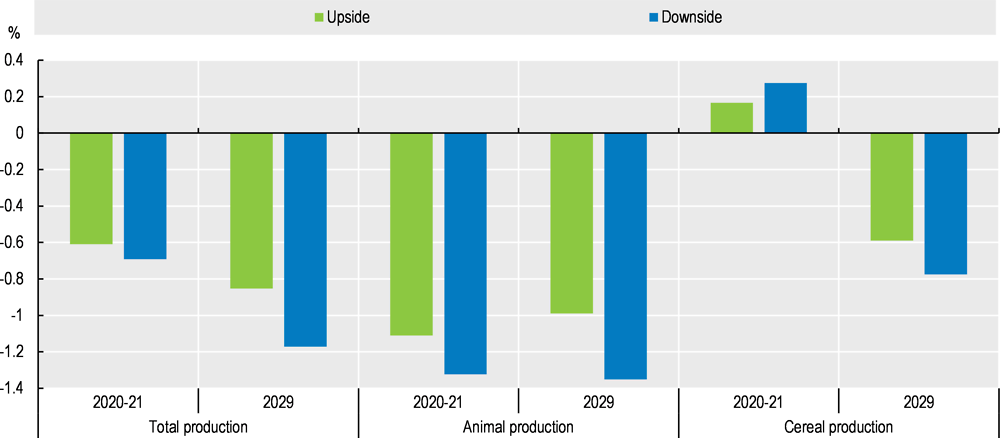

Decreased consumer demand puts downward pressure on agricultural prices and production

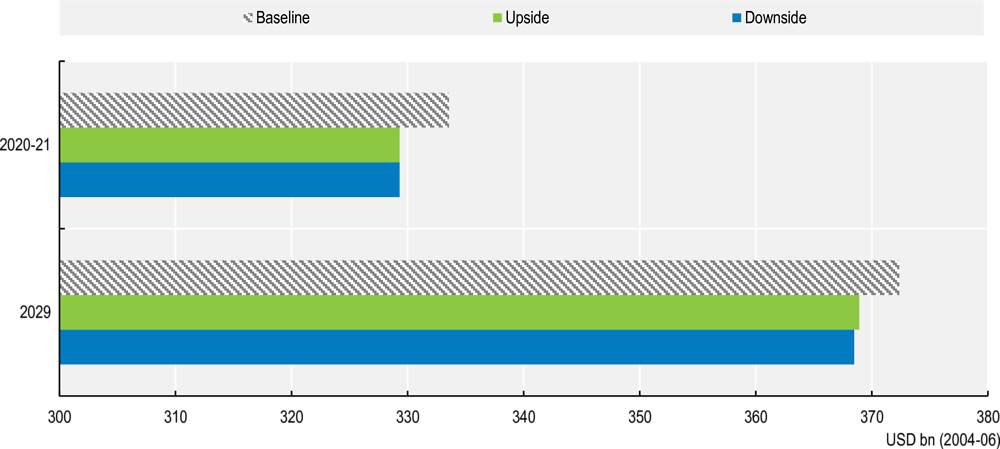

Lower consumer demand and subsequent price decreases lead to a reduction in agricultural production. Animal production is expected to decline more substantially than cereal production due to a relatively larger drop in demand for high-value products. In the short run, cereal production is projected to slightly increase in 2020-21 compared to the baseline, as lockdown measures trigger additional demand for staple foods (Figure 2).

Note: This figure shows changes in the value of production, as expressed in constant 2004-06 USD.

Source: OECD/FAO (2020), “OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-outl-data-en.

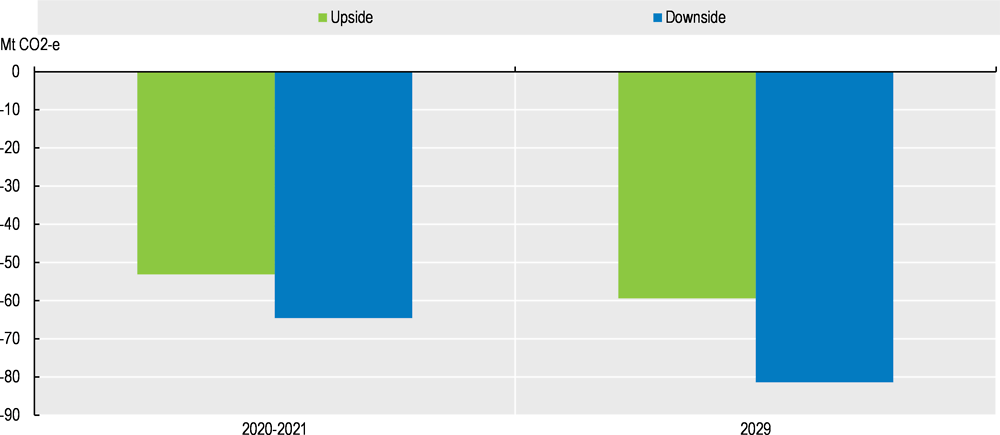

Changing agricultural production reduces the emission intensity of the sector

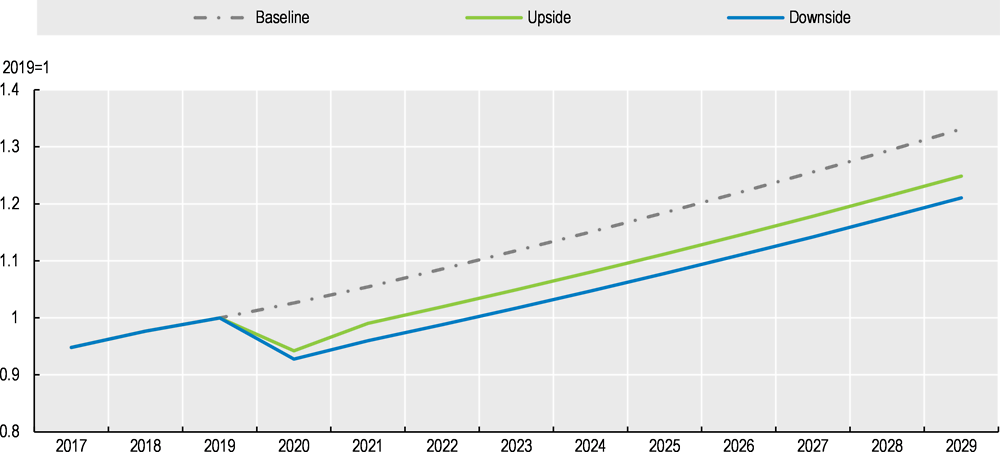

Due to this compositional change, whereby animal production is expected to decline more than cereal production, greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture are projected to fall at a higher rate than production, indicating a reduction in the emission intensity of the sector (Figure 3).

Source: OECD/FAO (2020), “OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-outl-data-en.

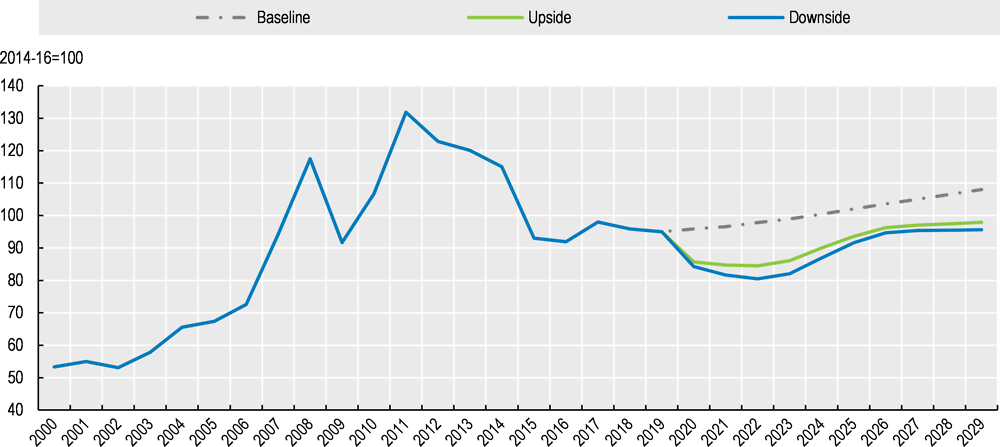

Agricultural prices gradually recover, after a fall in prices due to oversupply in the short run

As supply side reactions to lower demand will be delayed, agricultural prices are projected to fall in the short term due to oversupply of agricultural commodities. Starting from 2022, prices are expected to gradually recover but to remain below baseline levels until 2029 (Figure 4). These lower agricultural prices will put downward pressure on agricultural revenues. In 2020-21, agricultural revenues are projected to be 8.8% and 10.4% below baseline levels under the upside and downside scenarios, respectively (Figure 5). This average fall in prices only reflects the price impacts from decreasing incomes, and does not include price impacts of supply chain disruptions.

Source: OECD/FAO (2020), “OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-outl-data-en.

Note: Agricultural revenue is calculated as the sum over all products of production quantities times producer price plus the subsidy payments.

Source: OECD/FAO (2020), “OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-outl-data-en.

Agricultural exports slow down as a result of the pandemic

Global agricultural exports in 2020-21 are projected to drop over 1% in volume terms compared to the baseline due to the decline in demand and will only partially recover over the medium term (Figure 6).

Source: OECD/FAO (2020), “OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-outl-data-en.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has imposed a shock on agricultural markets and its effects will most likely reverberate throughout the coming decade. The macroeconomic impacts of the pandemic, such as the fall in household income, are leading to a decline in gross calorie demand, especially in LDCs. Further efforts will be needed to help end hunger and malnutrition by the end of the decade as the pandemic puts additional people at risk.

The agricultural sector will gradually respond to lower consumer demand, leading to a reduction in agricultural output. Livestock production is expected to decline more substantially than cereal production due to a larger drop in demand for high-value products. As the supply side reaction to this lower demand will lag, agricultural prices will fall, at least in the short run, putting additional pressure on farm revenues

Annex A. Scenario description and discussion of results

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global health crisis that is having devastating impacts on the world economy – both directly and through public-health measures to contain the spread of the disease. These impacts are also transmitted throughout the entire food system, simultaneously affecting consumer demand, disrupting agro-food trade and downstream food processing, and reducing seasonal labour and intermediary input availability (OECD, 2020[1]). In order to understand these potential impacts the analysis uses the Aglink-Cosimo simulation model, a comprehensive partial equilibrium model for global agriculture which underlies the baseline projections of the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2020-2029 (OECD/FAO, 2020[2]).3 This Annex describes the assumptions of the analysis. In addition, the Annex provides an in-depth discussion of the results and provides more information behind the graphs presented.

Description of the COVID-19 scenarios

This analysis considers two possible pathways for the evolution of the global economy:

An upside scenario: Successful vaccination campaigns, efficient government policies and better co-operation between countries are assumed to boost economic recovery.

A downside scenario: Delays to vaccination deployment and difficulties controlling new virus outbreaks are assumed to weaken economic recovery.

Taken together these pathways capture a range of plausible impacts within the context of an evolving pandemic with uncertain duration and strength. These uncertainties depend on the spread of the virus, as well as on policy developments implemented to contain the pandemic.

The two economic pathways used in this scenario analysis are based on the OECD Economic Outlook, published in June 2020. The analysis supplements the OECD macroeconomic projections with projection data from the World Economic Outlook of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), published in April 2020 (IMF, 2020[4]). More details about the macroeconomic assumptions underlying the analysis are provided in the sections below.

Macroeconomic assumptions

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, all countries are projected to experience a deep recession in 2020 followed by a slow and gradual recovery starting from 2021 (OECD, 2020[3]). Figure A A.1 shows the projected evolution of global GDP under the baseline, the upside and downside scenarios. Under the upside scenario, global GDP is projected to drop by 5.75% in 2020 compared to the 2019 level, and to be 8% below the pre-crisis projections for 20204 (i.e. the baseline). Following a gradual resumption of economic activity in the second half of 2020, the global economy is expected to grow by 5% in 2021, but to remain 6% below the baseline level. In the downside scenario, a larger drop in global GDP is projected, -7% in 2020 from the 2019 level, keeping global GDP 9.6% below the baseline projection. In 2021, the recovery will be less pronounced, with global GDP projected to rise by 3.5%, but to remain 9% below the baseline. In both scenarios, global GDP is not expected to return to baseline levels by 2029.

For the years 2020 and 2021, the evolution of global GDP under the upside and downside scenarios is based on country-level estimates from the OECD Economic Outlook (June 2020). For the countries for which estimates were not available in the OECD Economic Outlook5, projections from the World Economic Outlook of the IMF (April 2020) were used. To simulate the downside scenario, an additional 10% shock was added to the IMF projections. For the remaining years of the projection period, the baseline growth rates were applied to the revised 2021 values.6 The OECD and the IMF recently revised their macroeconomic projections.7 These most recent projections are in line with the upside scenario used in this analysis, while the downside scenario provides insights about a more pessimistic economic pathway.

Note: Assumptions for GDP in 2020 and 2021 under the upside and downside scenarios based on OECD Economic Outlook (OECD, 2020), extended for projection period using baseline growth rates.

Source: OECD/FAO (2020), “OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-outl-data-en.

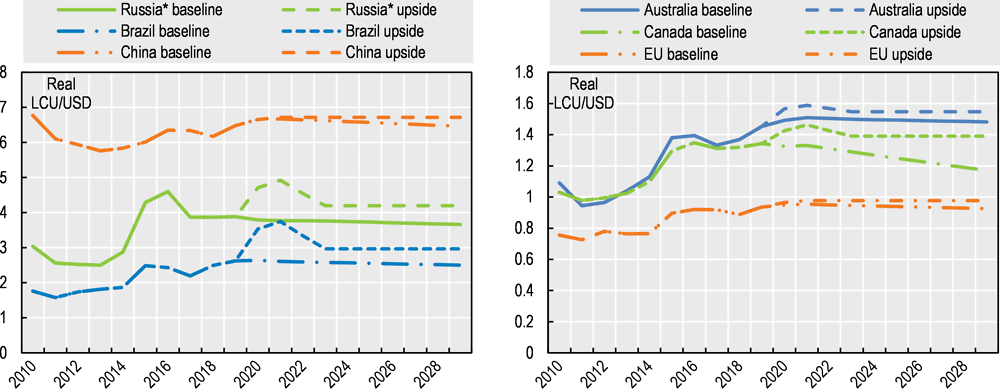

The COVID-19 pandemic also affected exchange rates. The US dollar continued to appreciate against almost all currencies, while the currencies of commodity exporters (e.g. Brazilian real), experienced significant depreciations. The devaluation of these commodity currencies reflects, to a certain degree, the sharp decline in commodity prices, notably those of petroleum, metals and energy and to a lesser extent those of agricultural products.

Under both scenarios, the exchange rates for the year 2020 are assumed to equal their current values (i.e. June 2020) and to remain stable in nominal terms over the projection period. However, for countries that experienced a devaluation above 5% in 2020 (i.e. Brazil and the Russian Federation ‒ hereafter “Russia”), additional adjustments were made to bring the exchange rate closer to the baseline values in the following years of the projection period, following the assumption that their currencies will bounce back. Figure A A.2 illustrates real exchange rate assumptions for selected countries under the baseline and the upside scenario. The exchange rate assumptions for the downside scenario are very similar to the ones of the upside scenario.

Note: * For Russia, the real exchange rate is expressed as RUB/(10*USD)). LCU stands for local currency.

Source: OECD/FAO (2020), “OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-outl-data-en.

In early 2020, oil prices collapsed due to the slump in demand and the lack of agreement between Saudi Arabia and Russia on supply cuts. Under the upside scenario, the crude oil price is projected to average at around USD 40/barrel in 2020 and 2021, down from USD 64/barrel in 2019. Thereafter, the oil price is expected to gradually recover, and is assumed to match the baseline value from 2025 onwards. Under the downside scenario, the drop in the crude oil price is projected to be even larger, with the oil price averaging at USD 36/barrel in 2020 and USD 30/barrel in 2021.8 The oil price is also projected to recover after 2022 and reach the baseline value in 2025.

Other assumptions9

As a result of the pandemic, substantial increases in final consumer prices have been witnessed, despite the fact that prices of bulk commodities remained low.10 In this scenario, this effect is incorporated by assuming a 2% increase in the producer-consumer price margin in 2020 and 2021 compared to the baseline, under both the upside and double hit scenarios. From 2022 onwards, the food system is assumed to adapt to the new situation and hence the margin returns to baseline levels.

Travel restrictions, border closures, and additional regulations and documentation requirements have formed an important part of the policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and these measures have significantly affected international trade. As long as these restrictions remain in place, they are likely to lead to a substantial increase in trade costs (WTO, 2020[5]). In this scenario, this effect is accounted for by assuming that trade costs increase by 2% of the export value in 2020 and 2021 compared to the baseline, and by 1% for the remainder of the projection period.

Detailed description of results

Impact on calorie demand

The lower incomes following the COVID-19 outbreak are expected to reduce gross calorie demand despite lower agricultural prices (see below). Under the upside scenario gross calorie demand per capita is projected to be 0.85% below baseline level in 2020-21 and 0.7% below baseline level in 2029.11 Gross calorie demand is projected to drop by an additional 0.3 percentage points throughout the projection period under the downside scenario.

Moreover, the impact on gross calorie demand is expected to be significantly stronger in least developed countries (LDCs) than in OECD countries. Under the two COVID scenarios, the projected percentage decline in gross calorie demand in LDCs is about two times higher than in OECD countries in 2020-21 and this effect is expected to be maintained over the medium term. The relatively larger drop in calorie demand in LDCs compared to OECD countries reflects the fact that households in LDCs spend a higher share of their income on food. Therefore, a drop in household income due to the economic downturn has a larger effect on food consumption in LDCs than in OECD countries.

While the average impact on calorie demand appears low, the impacts within countries are likely to be substantially larger, especially in those characterised by important income inequalities. Since the poorest segments of the population are expected to be at higher risk, it will be crucial that additional efforts are made to reach global food security by 2030, as targeted by the Sustainable Development Goals. Declining incomes will also make nutritious food (e.g. fruits and vegetables, dairy) less affordable, especially for the poor, suggesting a deterioration in the quality of diets (Schmidhuber, Pound and Qiao, 2020[6]).

Impact on agricultural production

The drop in demand for agricultural commodities and subsequent decline in prices will lead to a reduction in agricultural production. The impact on overall production is expected to be relatively small in the short term as it takes time for agricultural producers to respond to lower consumer demand. In the medium term, larger declines in total agricultural output are expected. By 2029, total production is projected to be 0.9% and 1.2% below baseline levels under the upside and downside scenarios, respectively. The production reaction is more pronounced in the downside scenario, as demand will be more affected if economic recovery is slower. Overall, the average impact on the production of commodities covered by the Outlook is expected to be limited.12 However, the supply of other agricultural products (e.g. fruits and vegetables) has been affected to a greater degree.

Moreover, as consumer demand is expected to fall more substantially for high-value livestock products than for staple foods, the decline in animal production is expected to be stronger compared to cereal production. Cereal production is even projected to slightly increase in 2020-21 compared to the baseline, as lockdown measures trigger additional demand for staple foods. In the following years, cereal production will fall to match lower demand, and in particular lower feed demand due to a decline in animal production. Animal production is projected to fall by 1.1% and 1.3% in 2020-21 under the upside and the downside scenarios, respectively. In the following years, animal production is projected to drop even further, albeit at a lower rate.

Impact on greenhouse gas emissions (GHG)

The decline in agricultural production under the COVID-19 scenarios is expected to lead to a reduction in direct GHG emissions from agriculture. In 2020-21, these emissions are projected to fall by 53 Mt CO2-e and 65 Mt CO2-e below the baseline levels in the upside and downside scenarios, respectively. Since agricultural output under these two scenarios is projected to keep declining over the medium term, a larger drop in GHG emissions is expected in 2029 compared to the baseline. In 2029, GHG emissions are projected to fall by 60 Mt-CO2-e and 81 Mt-CO2-e under the upside and downside scenarios, respectively.

In percentage terms, agricultural emissions are projected to drop more substantially than total production both in the short and medium terms. This projected decline in emission intensity of the sector is underpinned by the larger fall in demand for livestock products, which are more emission intensive than crop products. This compositional change (i.e. reduction in the share of animal production in total production) can therefore explain the larger drop in GHG emissions compared to agricultural production.

Impact on agricultural prices

As discussed above, the economic slowdown and surge in unemployment caused by the COVID-19 pandemic are projected to weaken global demand for agricultural commodities. Supply-side reactions to this lower demand will be delayed as production decisions (e.g. sowing of crops) were made prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This will lead to a relative oversupply of agricultural commodities—at least in the short term—causing agricultural prices to decline. In response, stocks of agricultural commodities are expected to increase, causing commodity prices to fall further until normal levels of consumer demand resume.

Scenario results also illustrate the expected evolution of the FAO Food Price Index (FPI), a weighted average of world prices for cereals, vegetable oils, sugar, dairy and meat, under the baseline, the upside and the downside scenarios for the period 2000-29.13 While this index gives a good overview of the general evolution of agricultural prices, the impact on prices will vary across specific commodities.

Under the COVID-19 scenarios, agricultural commodity prices are projected to drop by more than 10% below baseline level in 2020-21. This projected decline is more pronounced than that witnessed during the first half of 2020 partly because the model assumes that the effect is evenly distributed across the year and not monthly or staged by countries. Since the macro-economic impact on food demand is expected to be delayed, the largest impact on prices will be witnessed in 2022. After 2022, commodity prices are projected to gradually recover but they are not expected to return to baseline levels. Price recovery will not be complete since global GDP is also projected not to completely recover over the medium term. As explained above, a relatively lower global GDP and hence reduced level of consumer income translates into a subdued demand for agricultural commodities, but is assumed not to affect agricultural supply directly, which puts downward pressure on prices.14 Relatively larger drops in prices are expected under the downside scenario, with the FAO FPI projected to be 4% lower than under the upside scenario in 2022, and 2% lower in 2029.

Impact on farm revenues

The decline in agricultural prices resulting from the pandemic is expected to put downward pressure on farm revenues. In 2020-21, agricultural revenues are projected to be 8.8% and 10.4% below baseline levels under the upside and downside scenarios, respectively. This negative impact on revenues is expected to be maintained over the medium term, with agricultural revenues in 2029 projected to be 7.3% and 8.8% below the baseline in these scenarios. Lower prices and consequently declining agricultural revenues could spur increased protectionist policies and higher government support that can then further reduce international prices.

Impact on agricultural exports

The COVID-19 outbreak seriously disrupted agricultural trade (OECD, 2020[7]). Lockdowns and limits on the mobility of people reduced the movement of goods domestically and internationally. Lockdowns also reduced the availability of labour at ports to unload ships and conduct a variety of trade processes, such as physical inspections, testing and certifications. At the same time, many countries changed protocols determining access to ports, leading to disruptions from port closures and requirements for additional documentation and quarantine measures. In addition, some countries introduced temporary export restrictions, which reduced international trade even further. At the time of writing, lockdowns and movement restrictions have been lifted in several countries, but are assumed to be (re-)introduced in countries where the virus has started the (re-)emerge.

As a result of these disruptions and the decline in demand, global agricultural exports in 2020-21 are projected to drop by over 1% in USD value terms under both scenarios compared to the baseline. These global averages mask differences between countries, some of which will experience stronger decreases in agricultural exports than others. From 2022 onwards, agricultural trade is expected to pick up again and grow at similar rates as before the COVID-19 outbreak, but like the GDP recovery path, agricultural trade is not expected to completely return to baseline levels. By 2029, world agricultural exports under the upside and downside scenarios are projected to be around USD 3 billion and USD 4 billion (in constant 2004-06 terms) below baseline levels, respectively.

References

[4] IMF (2020), WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, April 2020: THE GREAT LOCKDOWN, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/04/14/World-Economic-Outlook-April-2020-The-Great-Lockdown-49306.

[13] IMF (2020), WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A Long and Difficult Ascent, http://www.imfbookstore.org.

[7] OECD (2020), “COVID-19 AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE: ISSUES AND ACTIONS”, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=128_128542-3ijg8kfswh&title=COVID-19-and-international-trade-issues-and-actions (accessed on 31 July 2020).

[1] OECD (2020), “Food Supply Chains and COVID-19: Impacts and Policy Lessons”, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/food-supply-chains-and-covid-19-impacts-and-policy-lessons-71b57aea/ (accessed on 31 July 2020).

[3] OECD (2020), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2020 Issue 1, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/0d1d1e2e-en.

[12] OECD (2020), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2020 Issue 2: Preliminary version, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/39a88ab1-en.

[11] OECD (2020), Shocks, risks and global value chains: insights from the OECD METRO model, https://issuu.com/oecd.publishing/docs/metro-gvc-final (accessed on 29 September 2020).

[9] OECD (2018), Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work: The OECD Jobs Strategy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264308817-en.

[10] OECD (2014), “The crisis and its aftermath: A stress test for societies and for social policies”, in Society at a Glance 2014: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/soc_glance-2014-5-en.

[8] OECD (2010), OECD Employment Outlook 2010: Moving beyond the Jobs Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2010-en.

[2] OECD/FAO (2020), OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2020-2029, OECD Publishing, Paris/Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1112c23b-en.

[6] Schmidhuber, J., J. Pound and B. Qiao (2020), COVID-19: Channels of transmission to food and agriculture, FAO, http://dx.doi.org/10.4060/ca8430en.

[5] WTO (2020), TRADE COSTS IN THE TIME OF GLOBAL PANDEMIC, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/trade_costs_report_e.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2020).

Contact

Hubertus Gay (✉ hubertus.gay@oecd.org)

Notes

This document uses the Aglink-Cosimo simulation model, a comprehensive partial equilibrium model for global agriculture which underlies the baseline projections of the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2020-2029. Details of the scenario are found in the annex to this brief.

In this document, gross calorie demand is calculated using the calorie availability estimate. Calorie availability in Aglink-Cosimo follows the concepts used in the Food Balance Sheets of FAOSTAT and refers to the quantities of food available for human consumption at the retail level by the country’s resident population. It also includes any loss or waste that appears at the retail or consumer level, which explains why availability is higher than actual consumption.

A detailed documentation on the Aglink-Cosimo model is available at http://www.agri-outlook.org/about/.

Since Aglink-Cosimo is an annual model, the shock on global GDP has been introduced as of 1 January 2020, while in reality the impact of COVID-19 proliferated later in the year. This assumption can explain why the simulation results in this brief for the year 2020 are slightly stronger than what has been witnessed so far.

The OECD Economic Outlook provides macroeconomic estimates for OECD countries and selected non-member economies (i.e. Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, India, Indonesia, and South Africa). For other countries, macroeconomic projections come from the IMF.

The assumptions for inflation under the baseline and the two scenarios are the same as for GDP growth.

The OECD Economic Outlook, published in December 2020, projects that after a 4.2% decline in 2020, global GDP will rise by 4.25% in 2021, and by a further 3.75% in 2022. To capture uncertainties around the deployment of a vaccine and the effect it would have, two additional scenarios are considered: an ‘’upside’’ and a ‘’downside’’ scenario. (OECD, 2020[12]). Note that the assumptions behind the upside and downside scenarios in this brief differ from the ones in the December 2020 edition of the OECD Economic Outlook. The IMF World Economic Outlook, published in October 2020, projects a 4.4% drop in global GDP in 2020 followed by a 5.4% recovery in 2021 (IMF, 2020[13]).

According to the US Energy Information Administration, the crude oil price averaged at USD 40.9/barrel between January and September 2020.

The scenarios make no assumptions about direct supply impacts of COVID-19 (e.g. labour force impacts). For recent OECD work incorporating labour productivity impacts and demand reductions and shifts, refer to (OECD, 2020[11]).

For example, the US Bureau of Labour Statistics reports that the consumer price index for food rose by 4.1% between August 2019 and August 2020 while the producer price index increased by only 0.17%.

In this brief, values for the period 2020-2021 refer to averages for the two-year period 2020-2021.

The OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook covers 25 agricultural commodities in the following product categories: cereals, oilseeds and oilseed products, sugar, meat, dairy and dairy products, fish, biofuels and cotton.

The FAO FPI captures the development of nominal prices for five agricultural commodity groups (cereals, vegetable oils, sugar, dairy and meat), weighted with the average export shares of these groups in 2014-2016. Since this commodity price index covers the same commodities as the Agricultural Outlook, it is possible to project the future evolution of the FPI as a summary measure of the evolution of nominal agricultural commodity prices.

This scenario assumes that the pandemic has no impact on agricultural productivity.