Abstract

This brief aims to support governments in designing gender-inclusive approaches to emergency management and recovery, building on OECD work and standards on gender equality in public life.1 Often due to pre-existing gender inequalities and socio-cultural norms, women have been disproportionately affected by the social and economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic. Building on information gathered from OECD members through an April 20202 survey and consultation with the Working Party on Gender Mainstreaming and Governance, the brief explores practices and challenges in accounting for gender-differentiated impacts and the economic inclusion of both men and women in government responses to the pandemic. It also looks at how countries can promote gender equality as part of the recovery process, including through the use of tools for planning, regulations, budgets and public procurement. Ultimately, this brief provides insights on creating conditions for emergency management and recovery that take into account the needs of both men and women.

1 This includes the 2015 Recommendation on Gender Equality in Public Life, the 2019 report Fast Forward to Gender Equality: Mainstreaming, Implementation and Leadership, and the forthcoming Gender-sensitive Framework for Sound Public Governance.

2 OECD survey “Mapping good practices and challenges faced by the Institutions in tackling the effects of COVID-19”, which was conducted at the start of the pandemic and includes a snapshot of early efforts as of April 2020

As well as targeted measures to tackle specific challenges faced by women (such as gender-based violence), governments need to consider how they integrate gender considerations into broader policy making and recovery strategies. Gender analysis helps inform COVID-19 pandemic-related policy-making by bringing to light potential impacts that mainstream responses1 can have on women and men, and on the economic recovery as a whole. It can also help identify and remove potential gender biases from policies, regulations and budgets. In addition, institutional co-ordination, information-sharing and consultation can help facilitate evidence-based decision making in relation to gender equality.

Ensuring relevant technical expertise on gender issues in emergency and recovery decision-making structures can help generate better policy outcomes. Furthermore, providing women with access to leadership opportunities in these structures and beyond may help ensure that decision-making processes are more inclusive of and responsive to the different experiences of women and men from diverse backgrounds.

Continued monitoring of the pandemic’s differentiated impacts on women and men will be crucial for determining whether additional measures are needed. This monitoring should include the extent of economic inclusion of both sexes, as well as gender equality implications more broadly. Moreover, where the speed of government responses did not allow for a thorough analysis of the different impacts on women and men, relevant measures (e.g. policy, planning, regulatory, budgetary and procurement) can be regularly monitored for their impact on gender equality and adjusted as required.

Collecting, analysing and using data, including sex- and/or gender-disaggregated data1, helps to ensure that both rapid responses and recovery are informed by the best available evidence. Countries could also identify and document gaps in sex- or gender-disaggregated data and information, to more accurately assess what investments are needed to ensure data infrastructure and governance allow for the regular collection, sharing and use of sex- or gender-disaggregated data. Furthermore, collecting sex- or gender-disaggregated data on corruption given its possible disproportionate adverse impact on women may deepen understanding of how corruption may be a concern in the economic response to the pandemic, and how it could affect women and men differently.

Building more gender-inclusive frameworks and plans now could help to ensure that, in future crises, different challenges faced by men and women are adequately addressed in a timely manner. Countries can take steps to mainstream gender-inclusive perspectives into the planning of recovery strategies, building on the practices described above. In addition, countries can review existing risk assessment frameworks and emergency management plans through applying a “gender lens” and update them to account for gender equality considerations.

Governments can further leverage government tools (e.g. regulations, budgeting and public procurement) to help ensure policy and structural adjustments benefit men and women equally as well as address gender inequality. Where appropriate, governments could expand the use of gender impact assessments in government processes, such as planning and budgeting.

Investing in good data governance and infrastructure could improve access to timely and disaggregated data, including sex- and/or gender-disaggregated data, as well as other identifying factors, and enable governments to tap into innovative sources of data to support more gender-inclusive policy responses.

Using sex- and/or gender-disaggregated data on corruption that was collected during the pandemic can help governments develop gender-inclusive public integrity frameworks that are more responsive to crisis-related corruption including during the recovery.

Mainstream responses refer to general actions that were taken in response to COVID-19 that were not specifically designed to target gender inequalities or women’s empowerment.

Introduction

Since the beginning of the pandemic, many countries have been taking steps to protect the lives of people, mitigate the resulting economic and societal shocks, and shape an inclusive recovery. In the immediate response to the health crisis, most countries introduced measures that restricted movement to limit the spread of COVID-19, such as physical distancing, home isolation, and school and workplace closures. In addition, some governments across the OECD have delivered large economic stimulus and relief packages to soften the economic impact of the pandemic on individuals and businesses. A range of measures have been introduced rapidly, such as direct fiscal support to individuals and households, the procurement of medical equipment and goods, and financing businesses and credit support (OECD, 2020[1]) (OECD, 2020[2]). Many measures have sought to help lower-income and vulnerable individuals who have been hit especially hard by the pandemic (OECD, 2020[3]). Experiences and outcomes, however, are not the same for everyone, and special attention should therefore be devoted to ensuring that government action and policies reduce rather than aggravate inequalities (OECD, 2020[4]).

As governments continue to manage the pandemic and lead the way out of it, they are presented with an opportunity to adopt people-centred and gender-inclusive approaches to recovery that are responsive to the needs of different groups. This brief aims to support governments in designing gender-inclusive approaches to emergency management and recovery, building on the OECD’s well-established work and standards on gender equality in public life.2 It highlights the importance of a dual approach that promotes women’s empowerment and mainstreams gender considerations in public policy by harnessing the tools of government, such as policy making, planning, regulations, budgets and public procurement. Effective policy making on gender equality requires commitment and action by all stakeholders through a whole-of-government approach; this brief is thus intended for policy makers across all bodies and levels of governments, regardless of their level of gender expertise.

The brief starts with an overview of the pandemic’s differential impacts on women and men, based on the understanding that these impacts are, in part, the result of pre-existing structural inequalities in societies and norms on gender. The brief will then highlight some of the measures that governments took at the onset of the pandemic as well as some of the challenges they have since faced in policy making, particularly with regard to using gender mainstreaming as a strategy for incorporating gender-inclusive considerations into emergency responses. The remainder of the brief will discuss different approaches that governments may consider in order to develop gender-inclusive emergency management and recovery plans. It will first present promising practices that countries have pursued to date, and then highlight more aspirational approaches that countries could consider going forward.

The content of this brief is primarily the result of consultative processes carried out with OECD member countries. The OECD Working Party on Gender Mainstreaming and Governance, which is composed of senior government officials who are responsible for or experts on gender equality issues, has contributed to the brief through a series of reviews, policy dialogue and comments during the drafting process. The brief is also informed by the results of the OECD survey “Mapping good practices and challenges faced by the Institutions in tackling the effects of COVID-19”, which was conducted at the start of the pandemic and includes a snapshot of early efforts as of April 2020.3 The survey was answered by 24 of the 37 OECD countries as well as Egypt and Tunisia.4 It explored the gender equality-related priorities and measures of countries, the immediate successes and challenges faced in mainstreaming gender-inclusive policies, and the tools used to incorporate gender-inclusive considerations into emergency responses. Finally, this brief, as well as the information gathered through above-mentioned efforts, are centred around priority areas previously identified in the OECD Recommendation on Gender Equality in Public Life, in the Public Governance Committee’s Strategy for Gender Mainstreaming and its Action Plan, and by the Working Party on Gender Mainstreaming and Governance.

The impact of COVID-19 is not the same for everyone

To date, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a different impact on men and women. Women have been disproportionately affected by the economic and social fallout from the pandemic, primarily because the pandemic has exacerbated pre-existing structural inequalities and gender norms (United Nations, 2020[5]) (Wenham, Smith and Morgan, 2020[6]). This section will highlight some of the ways in which women, in particular, have been disproportionately put at risk or affected by the pandemic.

Women face higher risks of domestic violence during periods of confinement and social distancing, such as those experienced during the pandemic to limit the spread of COVID-19. During the pandemic, there have been reports of increased calls to helplines and visits to websites offering support and assistance. In France, reporting to the Government’s online gender-based violence platform, Arrêtons Les Violences, increased by more 40% during its first lockdown (17 March – 11 May 2020) and by 60% during its second lockdown (30 October – 15 December 2020) (Le Monde, 2021[7]), while in Colombia, calls to the national helpline went up by 150% during the lockdown period between 25 March and 25 June 2020, compared to the same period in 2019 (OECD, 2020[8]). Although it is difficult to pinpoint causality at the time, studies have also indicated increases in domestic violence. In Japan, a recent survey by the Cabinet Office found that domestic violence consultations increased by around 11% from April to November 2020, compared to the same period in 2019 (Nippon, 2021[9]). In the United States, a systematic review of 12 studies on domestic violence found that domestic violence incidents increased by 8.1% following the imposition of stay-at-home orders in 2020 (Piquero, A. et al., 2021[10]). In addition to increasing risks of violence, lockdown and movement restrictions, coupled with reduced availability of relevant private services (e.g. legal, lodging and accommodation, and health), have limited survivors/victims’ access to justice and social support systems. It is thus likely that survivors/victims have had to depend heavily on the assistance provided by public services such as the police and legal aid centres. These dynamics are worrisome, as domestic violence can lead to physical injuries, mental health problems, and other health complications, all of which can also affect the ability of survivors/victims to perform paid and unpaid work, among other things.

Women also face differential economic risks, in part because the short-term economic fallout from COVID-19 affects particular sectors that rely on physical interactions with customers, many of which are major employers of women, particularly for part-time work (OECD, 2020[11]). Women are also overrepresented in the hardest-hit sectors within the informal economy, making them vulnerable to job losses and lack of social security protection (ILO, 2020[12]) (OECD, 2020[4]).

Women-led businesses already faced several barriers prior to the pandemic, including in accessing public procurement opportunities. Such businesses are often small in size and, as such, may lack the resources or networks to acquire or manage large-sized contracts, meet the financial requirements, or handle the administrative burden of the procurement process (OECD, 2018[13]). For instance, a study by the International Trade Centre and Chatham House shows that women entrepreneurs supply only 1% of the public procurement market (Rimmer, 2017[14]).

These barriers, along with structural inequalities, such as restricted access to credit for women, the finance gap among women-led businesses, and their disproportionate representation in lower-margin sectors, make women extremely vulnerable to the economic impacts of COVID-19 (OECD, 2020[4]) (OECD, 2017[15]).

Even before the crisis, women across the OECD provided, on average, two hours more per day of unpaid care than men (OECD, 2020[16]). Albeit with variations across countries, early survey data suggests that women took on additional family care responsibilities during social distancing (Andrew et al., 2020[17]) (UN Women, 2020[18]). This further limits the equal participation of women in the economy. In the United Kingdom, for example, a survey found that the number of hours mothers dedicated to paid work in April 2020 was 22% lower than the number of hours recorded in the 2014/15 UK Time Use Survey (Andrew et al., 2020[17]).

A dual approach is needed to tackle the socio-economic impact of the pandemic on women and gender equality

In order to effectively address the pandemic’s socio-economic impacts on women and men from diverse backgrounds, it will be important for governments to pursue a dual approach: 1) proactive and targeted policy making to close identified gender gaps and level the playing field for men and women (i.e. targeted actions); and 2) ensuring that government action does not inadvertently reinforce existing gender stereotypes and inequalities (see Box 1) through mainstreaming gender-inclusive considerations, in line with the OECD Recommendation on Gender Equality in Public Life.

Because of the complexity of gender equality as a public policy issue, the OECD Gender Recommendations (2013 Recommendation on Gender Equality in Education, Employment and Entrepreneurship; and 2015 Recommendation on Gender Equality in Public Life) encourage adopting a dual approach to narrowing gender gaps.

Governments can take targeted policy actions to level the playing field for men and women. These actions are designed to address specific forms of gender-based discrimination and enable progress in affected areas. As put forward by the 2013 OECD Recommendation on Gender Equality in Education, Employment and Entrepreneurship, such targeted policies to close gender gaps can include enabling parents to balance their work hours and family responsibilities; making it easier for women to participate in private and public sector employment; encouraging and increasing the representation of women in decision-making positions; eliminating the discriminatory gender wage gap; and reducing the gender gap in entrepreneurship activity. Some examples of targeted actions in these areas include making the study of science, technology, engineering, mathematics (STEM), financial and entrepreneurship topics, as well as education, arts and the humanities, equally inclusive and attractive for both boys and girls. Other targeted actions may include designing benefit systems so that both parents have broadly similar financial incentives to work; encouraging working fathers to take available care leave (e.g. by reserving part of the parental leave entitlement for the exclusive and non-transferable use by fathers); and increasing awareness of financial sources and tools among women entrepreneurs. In the particular context of the COVID-19 pandemic, some targeted measures may include expanding the coverage and use of paid parental leave, including among men, and introducing temporary support for non-standard workers and individuals in the formal and informal economy who are not covered by or entitled to receive social protection. This could be in the form of employment subsidies, liquidity support, or incentives such as grants to women-owned businesses and entrepreneurs in women-dominated sectors. With production and demand collapsing, many small and medium-sized enterprises face massive challenges in paying wages as well as sick leave for those workers affected.

At the same time, given the cross-cutting and pervasive nature of structural gender inequalities, particular attention should be brought to the baseline of structural policies, laws and regulations, budgets, and procurement processes in order to remove deeply rooted gender norms and stereotypes. For example, promoting women’s business ownership requires a smart policy mix which, among others, takes into consideration the gender impacts of regulatory policies and frameworks, while removing potential barriers in access to public procurement and finance. These efforts must be coupled with an enabling social infrastructure (including but not limited to paid parental leave for mothers and fathers, and more accessible and affordable child/elderly care). Gender mainstreaming is a powerful strategy to guide this whole-of-government process of promoting gender equality. There is a growing recognition by political leaders of the importance of mainstreaming gender-inclusive policies as a precondition for making progress on gender equality, with many countries already having practices and tools in place. As documented in the OECD’s 2019 Fast Forward to Gender Equality report, at least 13 countries have whole-of-government frameworks in place for gender equality, primarily in the form of strategies and action plans, while at least five have legal requirements for gender mainstreaming. Furthermore, at least 17 countries assess and take into account the different impacts of policies on men and women1 to inform the development of new legislation or budgets. Similarly, at least 17 utilise some form of budgeting that considers the different needs of men and women (see Box 2).

The impact of mainstreaming gender-inclusive policies can be difficult to quantify, but past practice demonstrates that when governments commit to the process, it can have tangible outcomes that benefit women and men of different backgrounds. For example, Iceland uses “gender assessments’’ or “gender analysis’’, which showed that commodity taxes on personal care products were being applied unevenly, resulting in women paying more than men for equivalent products. This led to Iceland abolishing the tax in question in 2017. In Canada, an analysis of the different impacts of policies on men, women and “gender-diverse” people – through its tool called “Gender-based Analysis Plus” – by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) found that a regulatory requirement for sponsored spouses and partners of Canadian citizens and permanent residents to live with their sponsor for two years as a condition to maintain their permanent resident status made women more likely to remain in abusive relationships rather than to seek support and protection services out of fear of losing their permanent resident status. In response, the IRCC eliminated this permanent residency requirement in 2017.

GIAs, sometimes also referred to as gender analysis, refers to the process of assessing and identifying the potential impacts that government decision-making can have on women and men. It can be helpful to identify and remove potential gender bias from the baseline of structural policies, regulations and budgets. As highlighted by the OECD Recommendation on Gender Equality in Public Life, they can be applied at all stages of the policy cycle, from the design of new policies to the evaluation of policies after implementation.

Source: 2013 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Education, Employment and Entrepreneurship, (OECD, 2017[19]) 2015 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Public Life, (OECD, 2016[20]) Fast Forward to Gender Equality: Mainstreaming, Implementation and Leadership, (OECD, 2019[21]) Empowering Women as Drivers of the COVID-19 Recovery (OECD, 2020[22])

As of April 2020, all countries that had responded to the OECD’s survey reported adopting targeted measures to address the immediate repercussions of the pandemic in the area of gender equality and women’s economic empowerment. An account of key targeted measures is provided in Annex A.

However, the OECD survey also showed that the ability of those governments to systematically mainstream policies that promote gender equality into emergency and exit responses was uneven at the earliest stages of the pandemic. Of the 26 countries responding to the survey, only 11 reported that they explicitly used assessments of the different impacts of policies on men and women to inform the design and/or delivery of policy responses and measures,5 both during the pandemic and in designing large stimulus packages and recovery measures (e.g. emergency contracting, tax proposals, individual and business support schemes, teleworking schemes, and measures to support the tourism industry). In part, this was due to the different approaches used by countries in applying gender impact assessments (GIAs) to policies, regulations and government programmes prior to the pandemic. Indeed as demonstrated in the 2019 OECD Fast Forward to Gender Equality report, the findings from a 2017 OECD survey of 17 countries showed that only about half of respondents reported implementing assessments of the different impacts of policies on men and women while developing new legislation or budgets.

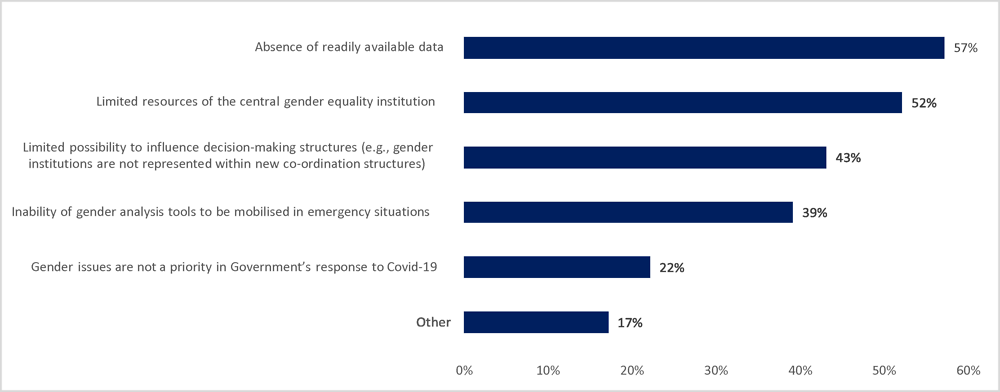

The speed of government reaction to the pandemic also meant that in many cases the standard procedures for developing policy and budget options were expedited or adjusted. In some instances, this may have affected the requirements for applying assessments of the different impacts of policies on men and women to policies, regulations or budgets, or for undertaking stakeholder consultations. Indeed, half of the respondent countries reported that the speed required and the absence of readily available sex-disaggregated data hampered the ability of decision makers to make informed policies that take into account the different impacts on men and women. Limited resources available to policy makers working on issues related to gender equality and women’s economic empowerment, and their limited representation in national crisis response teams, was also reported by nearly half of the responding countries as being a major challenge in effectively influencing the emergency decision-making structures. Furthermore, 22% of respondent countries reported difficulties with emphasising gender equality as a priority area in the overall governmental response to the pandemic (see Figure 1).

Source: (OECD, 2020[23]), Survey “Mapping good practices & challenges faced by the National Gender Equality Institutions in tackling the effects of COVID-19”, addressed to the OECD Working Party on Gender Mainstreaming and Governance under the aegis of the Public Governance Committee, April 2020

Accounting for gender equality in pandemic responses: promising practices by governments

Despite the challenges faced by countries in mainstreaming gender-inclusive policies, a number of countries have employed a range of practices to try to ensure that emergency management and recovery policies take into account the needs of men and women, recognising that the pandemic in many cases has exacerbated pre-existing inequalities. The section below highlights some of these promising practices, although further monitoring and evaluation of them will be essential for understanding what works in practice, and for whom, especially in the long term.

Informing policy making through gender analysis, information sharing and consultations

In a number of countries where well-established gender-mainstreaming systems6 were in place prior to the pandemic, governments used gender analysis to help inform decision making with gender equality considerations at the onset of the pandemic. In particular, 42% of countries responding to the OECD survey reported using assessments of the different impacts of policies on men and women to assess the responses to the pandemic. This was often facilitated by legal requirements, embedded existing procedures, an efficient system of sex-disaggregated data, or the results of assessments of the different impacts of policies on men and women conducted prior to the pandemic. For example, in Sweden, where GIAs have been made mandatory by a government decision, early observations by the Unit for Gender Equality at the Ministry of Employment showed that a majority of policy actions have included GIAs, although a more thorough analysis is needed to assess their quality.7 In Iceland, gender budgeting has been embedded as a tool in the budget process since 2015. The Government of Iceland used this tool to ensure key measures of a budget bill, which was adopted in response to the pandemic, were gender-inclusive. Furthermore, Iceland reported in response to the OECD survey that previous gender analysis of most public expenditure areas allowed the government to draw on this existing knowledge and facilitate the integration of gender-inclusive considerations into the budget. For more information on budgeting that takes into account the different needs of men and women in crisis responses, see Box 3.

In addition, some countries highlighted the role of institutional co-ordination and information-sharing mechanisms in addressing the impacts of the pandemic on women and men, including through mainstreaming gender-inclusive considerations into broader emergency and recovery measures. For example, in Canada, a new Taskforce on Equity-Seeking Communities and COVID-19 was launched to provide an interdepartmental forum for sharing information; aligning strategies, policies and initiatives; and engaging with representatives from equity-seeking communities.8 In Switzerland, the Federal Office for Gender Equality has been working with the national taskforce for COVID-19 to try to mainstream policies that promote gender-inclusive considerations in the Swiss Government’s response measures. In Italy, a women-specific taskforce, “Women for a New Renaissance”, was set up by the Minister of Family and Equal Opportunities to analyse, inform and propose policies to promote gender equality, particularly in the exit and recovery periods. In Mexico, the National Institute for Women (INMUJERES) ensured co-ordination and collaboration among Secretariats of the Federal Government and local governments to implement a gender-inclusive approach in addressing gender-based violence, unpaid care responsibilities, employment and income generation, and social protection measures for women.

There are also examples of governments consulting with external stakeholders to help account for the needs of women of diverse backgrounds. The United States, for example, has prioritised consultations with local organisations and implementing partners to improve inter-agency understanding of the different impacts of COVID-19 on men and women globally. To account for the speed at which decision making must be made, flexible structures such as expert advisory bodies on gender equality can help identify potential obstacles to gender equality and the potential gender impacts of emergency measures. Digital consultation platforms also provide another flexible and efficient avenue for convening and engaging with a broad range of stakeholders to source ideas and co-create solutions throughout the policy cycle. Furthermore, having well-developed mechanisms for consultation and co-ordination for decision making already in place can save time and effort. For example, to co-ordinate communication across its provinces and territories during the pandemic, Canada mobilised its Federal-Provincial-Territorial (FPT) Forum for the Status of Women.

Integrating gender-inclusive policies into emergency management plans

Almost all OECD countries have adopted national strategies to guide the risk and emergency management cycle (OECD, 2018[24]), and there are some promising examples of strategies taking into account gender equality considerations. For example, Japan applied a gender perspective in developing its disaster risk management strategies following the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011 (Government of Japan, n.d.[25]) (Gender & Disaster Pod, 2016[26]). In May 2020, the Basic Disaster Management Plan was revised to include a new clause that instructs local governments to encourage their disaster management and gender equality divisions co-operate, and to clarify the respective roles of the gender equality division and the gender equality centre during ordinary times and at each stage of disaster response. The Government of Japan also issued the “Guidelines for Disaster Planning, Response and Reconstruction from a Gender-equal Perspective” in May 2020, setting out the basic actions to be taken by local governments at each stage of disaster response.

Other national and regional governments have also been developing such frameworks. In British Columbia (Canada), the provincial government adopted an interim disaster recovery framework that promotes gender-inclusive recovery agendas, drawing on the Draft Principles that Guide the Province of British Columbia’s Relationship with Indigenous Peoples, as well as Gender-Based Analysis Plus (Government of British Columbia, 2019[27]). In Australia, the National Gender and Emergency Management Guidelines were developed as a federally funded project, in line with the growing interest in the link between gender equality and emergency management, to incorporate gender considerations into national guidelines (Gender & Disaster Pod, 2016[26]).

Moving forward, countries could consider reviewing existing risk assessment frameworks and emergency management cycles, taking into account the different impact on men and women from diverse backgrounds and subsequently update them to incorporate gender equality considerations, especially in light of lessons learned and experiences from the pandemic. This could help to ensure that women’s and men’s differential needs are addressed in a timely manner in the future, and that policy responses to pandemics and future crises are proactive rather than reactive.

Promoting inclusive decision making

Given the multi-dimensional impacts of the pandemic, most countries have set up central policy co-ordination structures to address emergency situations, primarily under the authority of the Prime Minister or the President9 (OECD, 2020[28]). Importantly, in a number of countries, these structures included officials responsible for issues related to gender equality and women’s empowerment. For example, the United Kingdom reported that having the most senior minister responsible for gender equality in two of the four main COVID-19 Cabinet Committees helped to ensure consistency across these issues.

The first wave of the pandemic also highlighted the pivotal role played by central gender equality institutions10, which are public bodies primarily responsible for supporting the government’s agenda to advance society-wide gender equality goals and women’s empowerment (OECD, 2019[21]). In countries where they exist, these institutions often helped push gender perspectives and the needs of women and girls to the forefront of decision making in the pandemic, including by leveraging stakeholder relations, policy analysis tools and internal expertise. In Spain, for example, the Instituto de la Mujer has published data and analysis on the potential impacts of the pandemic on women to help policy makers across various sectors account for gender equality in COVID-19 responses (Government of Spain, 2020[29]). In Egypt, the National Council for Women published a policy paper, “Egypt’s Rapid Response to Women’s Situation During COVID-19 Outbreak”, for the guidance of the Cabinet. In the United Kingdom, placing the Government Equalities Office in the Cabinet Office has facilitated the sharing of key equality-related information with central decision-making bodies, while also encouraging government departments to seek out the Office’s expertise. Yet, many countries reported the limited resources of gender equality institutions as among the biggest impediments to effectively taking into account the needs of men and women during the pandemic and in recovery measures.11

In addition, the pandemic has shown how a coherent, government-wide approach is needed to address gender gaps, which were exacerbated during the pandemic. For example, the Government of Iceland has reported that sharing responsibility for gender equality between the Prime Minister’s Office and the Ministry of Finance, an institutional arrangement that predates the pandemic, has helped ensure that gender equality is considered at two different levels of the decision-making process during the pandemic. In Switzerland, the government established a national task force on domestic violence consisting of various federal offices and regional government authorities. Led by the Federal Office for Gender Equality, this inter-agency task force has monitored and assessed the situation of domestic violence during the pandemic, and has subsequently guided and co-ordinated national and sub-national government decision making in this policy area.

Furthermore, the pandemic has demonstrated that women leaders can offer decisive and inclusive solutions to difficult problems countries are confronted with (Taub, 2020[30]) (Garikipat, 2020[31]). Several respondents to the OECD survey highlighted that women’s leadership at the ministerial level was pivotal in ensuring rapid recognition of women’s different needs during the pandemic. These findings echo the previous OECD work showing that women’s participation in decision-making can lead to more inclusive policies and service delivery (e.g. through drawing attention to issues such as gender-based violence, family-friendly policies and responsiveness to citizen needs) (OECD, 2015[32]). Yet, women appear to have been significantly underrepresented in decision-making structures set up to respond to the pandemic12 (CARE, 2020[33]). Such gender imbalances are also reflected across the government more broadly, particularly in ministerships and senior civil service positions that play key roles in the design and delivery of pandemic-related policies (OECD, 2019[34]) (OECD, 2019[21]).

Monitoring and evaluating pandemic responses from a gender perspective

A number of countries have recognised the importance of monitoring and evaluating the impacts of pandemic responses, including on women and girls. On the one hand, this includes monitoring and evaluating13 the impacts of an emergency situation on gender equality. During the pandemic, for example, the Norwegian Directorate for Children and Family Affairs was commissioned to map equality consequences of the pandemic on the basis of gender, as well as on other grounds for discrimination, and to report regularly on this. In Ireland, the Department of Justice and Equality has been working to incorporate gender and intersectional perspectives into research on the impact of the pandemic, particularly with regard to vulnerable groups such as the Roma population. In France, the Inter-Ministerial Mission for the Protection of Women Against Violence and the Fight Against Trafficking in Human Beings published a report assessing the impact of the pandemic on domestic violence and identifying measures that should be triggered in the event of a new lockdown (MIPROF, 2020[35]).

On the other hand, measures adopted through accelerated procedures in response to the pandemic may benefit from a review of their impact on gender equality. In Canada, for example, the government has used its Gender Results Framework to examine the impacts of COVID-19 on women and other groups. This has helped the government to map response measures to specific impacts of the pandemic as they are implemented and new data become available. The Swedish government has appointed a committee of inquiry to evaluate the measures taken by the government, administrative authorities and municipalities to limit both the spread and effects of COVID-19, and the committee will report on the measures’ consequences on gender equality. Actions such as these may help strengthen the premise for taking into account gender considerations in the design of forthcoming recovery policies.

Gender equality and women’s economic empowerment as part of the recovery

At the 2020 OECD Ministerial Council Meeting, Ministers recognised the importance of gender equality as part of a broad-based recovery, and committed to empowering women as key drivers of economic recovery by striving to remove the legal, regulatory and cultural barriers to their full economic participation (OECD, 2020[36]). There is a window of opportunity for countries to start strengthening and expanding the mainstreaming of policies that promote gender equality and women’s economic empowerment as part of their recovery efforts. This would help countries to be more effective and decisive in pursuing women’s economic empowerment and gender equality agendas. For example, this could be done by addressing gender gaps in occupational groups and sectors through fiscal recovery packages, or identifying underlying regulatory barriers to women’s entrepreneurship that may stem from deeply rooted gender stereotypes. By systematically shining light on gender gaps that the pandemic has exacerbated, gender mainstreaming can also help make the gender equality agenda more resilient to future shocks. Without more concerted efforts to account for gender equality in policy making, the recovery process may further deepen existing gender inequalities across societies.

This section will outline additional considerations for effective gender mainstreaming as a means to achieve gender equality. The approaches covered in this section are considered to be more aspirational and, in some cases, more experimental. Nevertheless, they mostly build upon existing practices from countries that were early adopters of them, in line with the 2015 OECD Recommendation on Gender Equality in Public Life. Going forward, however, it will be important to continue to test these approaches and increase the evidence on what works and what does not.

Integrating gender equality into recovery strategies

As an important step towards a gender-inclusive recovery, some countries have started reflecting on gender equality issues in the planning phase of recovery strategies. In the United Kingdom, for example, different approaches have been taken in different regions, while also ensuring that statutory duties, which required all public authorities (not just the central government) to assess whether social distancing provisions were consistent with the Equality Act 201014, are upheld. The Government of Scotland has initiated equality impact assessments on the recovery measures proposed in Scotland’s “Route Map Through and Out of the Crisis” (Government Office for Science - UK, 2020[37]). As part of this assessment process, it has developed a strategic overview of the measures needed to exit from the lockdown, identifying key actions under each phase outlined in the Route Map, and identifying the potential impacts on different vulnerable groups along with mitigating actions to reduce negative impacts or reinforce positive ones. Similarly, the Welsh Government’s recovery framework, “Leading Wales Out of the Coronavirus Pandemic: A Framework for Recovery”, lays down criteria that must be met before easing restrictions (Welsh Government, 2020[38]). These evaluation criteria also include the impact on social and psychological well-being metrics, including based on sex. Overall, reflecting on the needs of and impacts on both men and women at the onset of recovery planning would be important to ensuring that no one is left behind during the recovery process. Therefore, as more countries plan for recovery, they could consider taking their own approaches to incorporating gender equality considerations into their strategies.

Using government tools to support gender equality outcomes

As previously discussed, gender norms and stereotypes can be embedded in the baseline of government policies. The same is true for government tools, such as regulations, budgets and public procurement. Therefore, if these tools are applied without consideration of the different impacts they may have on men and women, they may negatively affect gender equality during the recovery process. For example, if the pandemic’s impacts on women’s employment and businesses are not considered in designing and implementing regulations and budgets, financial aid and welfare benefits may not be sufficiently directed to women-dominated sectors and businesses, which, in turn, could worsen economic gender gaps. On the other hand, since budgets, regulations and procurement are critical instruments in the hands of governments to act and influence behaviours, they could become important tools for the advancement of gender equality in the recovery phase, particularly if they are used to target structural inequalities that the pandemic has exacerbated. When applied through a gender lens, for example, these tools can promote women’s economic empowerment by encouraging full participation in the labour market, addressing occupational discrimination, and supporting female entrepreneurship and access to finance.

Regulations, in particular, are a key instrument of governments for influencing behaviours and bringing about changes in society. As such, regulatory decisions will play a vital role in the immediate-, medium- and long-term responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has made the need for trusted, evidence-based, internationally co-ordinated and well-enforced regulation more pronounced (OECD, 2020[39]). As the pandemic may require countries to continue to adapt regulations or introduce new ones, there is an opportunity to strengthen the integration of a gender lens in the regulatory policy cycle. In part, this could be pursued through a gender analysis of regulatory impact assessments (RIAs) at the design and review stages (OECD, 2019[21]), which at least 30 OECD countries have reported doing, to some extent, prior to the pandemic (OECD, 2019[21]). In Canada, for example, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, the central regulatory oversight body, has required that regulatory submissions continue to apply the same RIA elements during the pandemic, including gender-based analysis. Moreover, countries could consider applying an intergenerational lens to assess the impact of laws on different age groups, especially young men and women and future generations.

Given the central role that budgets play in determining how resources are allocated to deliver policy outcomes, they are a powerful tool for supporting the implementation of cross-cutting priorities such as gender equality (OECD, 2020[40]). As such, gender budgeting, which 17 OECD countries practice to some extent (OECD, 2019[21]), could help facilitate informed decision making and mobilise public policy and resources towards transformative investments that help achieve gender equality goals and ensure that recovery efforts lead to a more equitable society (see Box 2).

The OECD defines gender budgeting as ‘’integrating a clear gender perspective within the overall context of the budgetary process, through the use of special processes and analytical tools, with a view to promoting gender- responsive policies”. While the OECD refers to gender budgeting under umbrella terminology, which jurisdictions have adapted to their contexts, what is shared is the deliberate intention of anchoring equality (gender and for other groups) into existing budgetary and policy-making frameworks. This can be done in addition to targeted investments in gender equality and diversity measures.

Some OECD countries implement gender budgeting through a range of approaches that build on existing elements of their budgeting systems. Tools employed in some OECD countries include:

Gender impact assessments: Analysis of the gender-differentiated impact of existing and/or new budget measures (both ex ante and ex post).

Gender dimension in performance setting: Identifying gender equality indicators and objectives as part of the performance budgeting framework.

Gender budget statement: A summary of how budget measures are intended to support gender equality priorities.

Gender budget tagging: Tracking how programmes and activities support gender equality objectives, helping to quantify financial flows.

Gender perspective in evaluation and performance audit: Identifying whether gender goals relating to different policies and programmes were achieved.

Gender perspective in spending review: Ensuring spending reprioritisation has a positive impact on gender equality goals.

The introduction of these tools is not an end in itself, and each country that uses them selects an approach tailored to their needs and systems of governance. Information gathered through their implementation may support analysis and more informed budget decisions, helping governments ensure the coherence of budget decisions with strategic priorities.

Source: (OECD, 2020[41]) Gender Budgeting Framework Highlights

In countries where there is a strong culture of gender impact assessment, gender budgeting might be used to acquire information on how policy measures contribute to gender equality goals, to be provided alongside proposals for fiscal recovery packages (OECD, 2020[40]). This presents an opportunity for countries to apply it to recovery-related economic stimulus packages and budgets. Alternatively, where a spending review is used to prioritise recovery measures, the central budget authority might have gender equality as an explicit criterion in the spending review process. Or, where performance frameworks drive the design of fiscal recovery measures, performance targets accompanying budget measures could be aligned with national objectives, including gender objectives. Box 3 describes gender budgeting in crisis response as adopted by Canada and Iceland.

Canada

In Canada, the Gender Budgeting Act requires the Government to prepare a Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) for every response measure. In line with this requirement, the Government published these assessments in its July 2020 Economic and Fiscal Snapshot. In addition, the Government used its Gender Results Framework to examine the impacts of COVID-19 on diverse groups, helping it to map response measures to specific impacts of the pandemic. For example, the Gender Results Framework includes a pillar on “poverty reduction, health and wellbeing”. Analysis found that in May 2020 women, youth and indigenous peoples were more likely to report poorer mental health. The Government included support for virtual care and mental health tools in its response measures.

Iceland

In Iceland, gender budgeting has been embedded in the budget process since 2015. The response to the pandemic was the first time an overall gender impact assessment was introduced as part of a budget bill. Gender impact assessments were undertaken in relation to key measures, including a wide-ranging investment programme. To undertake this analysis, line ministries were asked to estimate the number of jobs created and the gender ratio of these jobs in their project proposals. Where this information was incomplete, the Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs helped to estimate this information. The Government also made an effort to move beyond a discussion of the gender impact during the actual construction phase in order to understand how infrastructure would be used and the corresponding impact it has on gender equality. The Government found that this makes for better and more equitable decisions on the choice of infrastructure projects to be undertaken.

Source: Information provided by the Governments of Canada and Iceland at the occasion of the Virtual Workshop on Gender Budgeting and the COVID-19. 10 July 2020

Public procurement is another tool that governments could use to advance gender equality during the recovery phase of the pandemic. Public procurement accounts for approximately 12% of gross domestic product in OECD countries (OECD, 2019[34]), which gives governments some ability to ensure that women receive information and are able to compete for bids in a similar way to men. In particular, this could be achieved by levelling the playing field for women-owned or women-dominated businesses as part of recovery policies through reaching out to such businesses to inform them of procurement opportunities, and providing training to increase these businesses’ ability to compete. Prior to the pandemic, some countries had already started using procurement in a more strategic manner to advance gender equality outcomes. For example, Switzerland requires equality in the pay of men and women in all companies as a condition for awarding government contracts (OECD, 2019[21]). Depending on the actual systems and practices used by individual governments, these examples could offer lessons for countries who are interested in testing similar approaches to public procurement as part of the recovery process (OECD, 2020[42]). There is also scope for countries to carry out post-implementation reviews of emergency procurement contracts to understand their actual impacts on women’s economic empowerment and gender equality, and use the information generated for future planning, including for emergency preparedness.

Strengthening data availability and infrastructure to capture the needs and conditions of diverse groups of men and women

As discussed above, where countries were able to mainstream gender considerations into their emergency and recovery responses, they often relied heavily on existing data and analysis. As such, the ability of governments to implement policies that promote gender equality, in many cases, is dependent on the availability of sex- or gender-disaggregated statistics. In view of this, countries, in the short term, may identify and document sex- or gender-disaggregated data and information gaps that the pandemic has exposed, preparing the ground to undertake more accurate assessments on the investments needed to ensure sufficient data availability across the sectors. Governments may also begin to consider whether there are ways to leverage existing partnerships and relationships with external stakeholders to identify new and innovative sources for data collection in the future, especially in responding to future crises.

In addition, the pandemic has highlighted the need to strengthen multi-level government and cross-government co-ordination, as part of data infrastructure and governance, in the collection and sharing of relevant and cross-sectoral timely data (OECD, 2019[43]). Lack of co-ordination was reported as one of the biggest challenges by leading government agencies in the use of data as part of crisis response.15 In the medium term, governments could aim to further prioritise and strengthen the capacity of statistical agencies, gender equality institutions, sectoral ministries and other government agencies to collect, share and use sex- or gender-disaggregated data (OECD, 2019[21]), especially data on the pandemic across all policy areas.

While the potential of big data and open data in the areas of health and public information has been explored, they still have an untapped potential to expose gaps and provide insights on systemic societal issues such as gender equality. For example, in Sweden, where sex-disaggregated data is commonly used, analysis of sex-disaggregated data on transport patterns helped shape a more, gender-inclusive snow-clearing policy (OECD, 2019[44]). The OECD Open, Useful and Re-usable data (OURdata) Index: 2019 calls upon member countries to invest in good data governance, architecture and infrastructure in order to collect and release more sex- and/or gender-disaggregated data in open data formats. This ensures that the quality of data throughout the entire data value cycle is gender-inclusive. Countries may also develop new ways of collecting, storing and analysing data, to enhance their capacity to generate gender-inclusive policy responses. However, there are also several challenges related to data governance that need to be addressed before the full potential of open data and big data can be harnessed, including biases in data collection and analysis, privacy concerns, data timelines, accessibility, granularity, and interoperability and legacy challenges associated with data management systems and technologies (OECD, 2019[45]) (OECD, 2019[43]). Furthermore, the digital gender divide can affect the generation of big data that can be used to promote gender equality.

Enabling data systems to collect multi-level disaggregated data that accounts for the intersecting identity factors of women and girls may also strengthen sound decision-making with regards to crisis responses and recovery planning. These intersecting factors may include, among others, age, race, disability, ethnicity, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, educational background and geographical location. As demonstrated during the pandemic, intersecting identity factors may create additional barriers for women and girls in accessing public services, and these barriers are aggravated in emergency situations. For example, older women – given their higher life expectancy and greater likelihood of experiencing health problems – often make up the majority of residents in long- term care facilities (OECD, 2017[15]), which are at high risk of being affected by the virus. Some countries across the OECD are starting to systematically apply a gender lens to decision making that can capture intersecting identity factors. For example, the United Kingdom works to make data standardly available by sex, ethnicity and disability. The United Kingdom Office of National Statistics offered some recent analysis regarding the mortality rates from COVID-19, which disaggregated data by specific ethnicities and by sex (Booth and Barr, 2020[46]). Similarly, the Government of Canada has committed to collecting and publishing data from an intersectional identify lens in order to account for the diversity of its population in policy analysis and planning. As part of this commitment, Statistics Canada has developed the Gender, Diversity and Inclusion Hub. The Hub tracks, in part, the Government’s progress on the Gender Results Framework indicators, many of which are available by intersecting identity factors. The Hub has also a section focused specially on COVID-19 where relevant data on gender and other identify factors can be found (Statistics Canada, 2020[47]). In this regard, having sex- and age-disaggregated data may be useful in order to track inequalities and inform decision-making on the impact of the pandemic across different generations of women and men (see Box 4).

Efforts have been made to modernise how the Government of Canada collects, uses and displays sex and gender information. These modernisation efforts include introducing a new gender identifier (“X”) across federal programmes and services and, in 2018, the Government of Canada introduced the Policy Direction to Modernise the Government of Canada’s Sex and Gender Information Practices. In addition, in 2018/2019, the Government allocated CAD 6.7 million in funding over five years, with CAD 600,000 thereafter, to create the Centre for Gender, Diversity and Inclusion Statistics (CGDIS). The goal of the CGDIS is to support evidence-based policy and programme development by monitoring and reporting on gender, diversity and inclusion. The CGDIS launched the Gender, Diversity and Inclusion Statistics Hub, which focuses on disaggregated data by gender and other identities to support evidence-based policy development and decision making. The Hub is a centralised platform to provide support to departments as they prepare advice for ministers and develop evidence-based policy. To monitor progress on the Government of Canada’s Gender Results Framework, the CGDIS released 29 indicator tables, disaggregated by gender and other identities. These indicators are used to inform Canadians about Canada’s progress in achieving gender equality. The CGDIS has undertaken work to support the collection of disaggregated data for the LGBTQ2 population. For example, a new gender standard was developed. This gender standard was included on the 2019 Census Test and is currently being used in many social surveys. It allows Statistics Canada to better report on Canada’s gender-diverse population and ensures that Statistics Canada’s data reflect the realities of the Canadian population. The CGDIS is also developing a new standard for disaggregating data based on sexual orientation. Gender-disaggregated data is deemed important for policy makers to be able to assess the situation and develop appropriate, evidence-based responses and policies. Gender data and statistics are essential for assessing how effectively the country is achieving equitable outcomes for all genders. Not only do they help the Government track progress, but they also identify gaps – telling the Government where more work and focus are needed.

Source: Information provided by Women and Gender Equality Canada

Making integrity systems more gender inclusive

Evidence from past recessions points to a higher rate of integrity violations such as occupational fraud, embezzlement and bribery in the aftermath of economic downturns (OECD, 2020[48]). Some populations may be at higher risk from such violations, as well as from more indirect impacts of corruption, and women may experience corruption differently than men (Sierra and Boehm, 2015[49]). While much more evidence is needed to understand the full impact of corruption on gender equality, in the current pandemic, corruption may affect women’s access to basic goods and services, and the design and distribution of subsidies and benefits (Transparency International, 2020[50]).

Corruption and bribery in the design, delivery and implementation of economic stimulus packages, subsidies, social welfare services, official development assistance and export credits may also exacerbate existing social inequalities and barriers faced by women from diverse backgrounds as well as intersecting challenges. However, few countries appear to be considering the potential differential impact on women and men in their public integrity systems. Given the potential for greater deployment of some of these tools as part of the economic recovery from COVID-19, more work is needed to understand the relationships between these policy measures, corruption, and women’s empowerment.

References

[17] Andrew, A. et al. (2020), How are mothers and fathers balancing work and family under lockdown?, Institute for Fiscal Studies, https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14860?mc_cid=f84c1a0f2b&mc_eid=%5bUNIQID%5d.

[46] Booth, R. and C. Barr (2020), Black people four times more likely to die from Covid-19, ONS finds, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/07/black-people-four-times-more-likely-todie-from-covid-19-ons-finds.

[33] CARE (2020), Where are the women? The Conspicuous Absence of Women in COVID-19 Response, CARE International, https://insights.careinternational.org.uk/publications/whywe-need-women-in-covid-19-response-teams-and-plans.

[31] Garikipat, S. (2020), Leading the Fight Against the Pandemic: Does Gender ‘Really’ Matter?, http://www.reading.ac.uk/web/files/economics/emdp202013.pdf.

[26] Gender & Disaster Pod (2016), National Gender and Emergency Management Guidelines, https://www.genderanddisaster.com.au/info-hub/national-gem-guidelines/.

[27] Government of British Columbia (2019), Interim Provincial Disaster Recovery Framework, https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/public-safety-and-emergency-services/emergency-preparednessresponse-recovery/local-government/provincial_disaster_recovery_framework.pdf.

[54] Government of France (2020), Orange pleinement mobilisé aux côtés de l’Etat pour garantir une continuité du service d’écoute aux victimes et auteurs de violences conjugales et intrafamiliales, https://www.egalite-femmes-hommes.gouv.fr/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CP-Orange-pleinement-mobilise-aux-cotes-de-lEtat-pour-garantir-une-continuite-du-service-decoute-aux-victimes-et-auteurs-de-violences-conjugales-et-intrafamiliales-060420.pdf.

[56] Government of Japan (2012), Disaster Prevention and Reconstruction from a Gender, https://www.gender.go.jp/english_contents/about_danjo/whitepaper/pdf/ewp2012.pdf.

[25] Government of Japan (n.d.), Promotion of Gender Equality in Disaster Prevention Field, http://www.gender.go.jp/english_contents/pr_act/pub/pamphlet/women-andmen13/pdf/supplement8.pdf ( (accessed on 29 July 2020).

[29] Government of Spain (2020), The gender approach: key in Covid-19 response, https://www.inmujer.gob.es/diseno/novedades/PlantillaCovid-19/EN_IMPACTO_DE_GENERO_DEL_COVID-19_03_EN.pdf.

[37] Government Office for Science - UK (2020), Coronavirus (COVID-19): scientific evidence supporting the, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/coronavirus-covid-19-scientificevidence-supporting-the-uk-government-response.

[12] ILO (2020), ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work, ILO, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_7431.

[7] Le Monde (2021), Violences conjugales : les signalements pendant le deuxième confinement ont augmenté de 60%, https://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2021/01/09/violences-conjugales-les-signalements-pendant-le-deuxieme-confinement-ont-augmente-de-60_6065754_3224.html .

[35] MIPROF (2020), Les Violences Conjugales pendant le Confinement: Evaluation, Suivi Iet Propositions, Government of France, https://www.egalite-femmes-hommes.gouv.fr/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Rapport-Les-violencesconjugales-pendant-le-confinement-EMB-23.07.2020.pdf.

[9] Nippon (2021), Japan Sees Record Increase in Domestic Violence Consultations in 2020, https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-data/h00913/ .

[36] OECD (2020), 2020 Ministerial Council Statement: A Strong Resilient, Inclusive and Sustainable, OECD Publisher, http://www.oecd.org/mcm/C-MIN-2020-7-FINAL.en.pdf.

[28] OECD (2020), Building resilience to the Covid-19 pandemic: the role of centres of government, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/building-resilience-to-the-covid-19-pandemic-the-role-of-centres-of-government-883d2961/.

[40] OECD (2020), Designing and Implementing Gender Budgeting, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/designing-and-implementing-gender-budgeting-a-path-toaction.pdf.

[22] OECD (2020), Empowering Women as Drivers of the COVID-19 Recovery, OECD Publishing, https://one.oecd.org/document/GOV/PGC/GMG(2020)3/FINAL/en/pdf.

[41] OECD (2020), Gender Budgeting Framework Highlights, https://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/GenderBudgeting-Highlights.pdf.

[8] OECD (2020), Gender Equality in Colombia: Access to Justice and Politics at the Local Level, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/b956ef57-en.

[23] OECD (2020), Mapping good practices and challenges faced by the National Gender Equality Institutions, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/women-at-the-core-of-the-fight-against-covid-19-crisis-553a8269/.

[16] OECD (2020), OECD Gender Data Portal, OECD Publishing, http://www.oecd.org/gender/data (accessed on 13 May 2020).

[11] OECD (2020), OECD Short-Term Labour Market Statistics Database, http://dotstat.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=STLABOUR (accessed on 28 September 2020).

[48] OECD (2020), Public Integrity for an effective COVID-19 response and recovery, OECD Publishing, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/public-integrity-for-an-effective-covid-19-response-and-recovery-a5c35d8c/.

[39] OECD (2020), Regulatory quality and Covid-19: Managing the risks and supporting the recovery, OECD Publisher, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/regulatory-quality-and-covid-19-managing-the-risks-and-supporting-the-recovery-3f752e60/#section-d1e90.

[42] OECD (2020), Stocktaking report on immediate public procurement and infrastructure responses to COVID-19, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/stocktaking-report-on-immediate-public-procurement-and-infrastructure-responses-to-covid-19-248d0646/.

[3] OECD (2020), Supporting livelihoods during the COVID-19 crisis: Closing the gaps in safety nets, OECD Publishing, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/supporting-livelihoods-during-the-covid-19-crisisclosing-the-gaps-in-safety-nets-17cbb92d/.

[1] OECD (2020), Supporting people and companies to deal with the COVID-19 virus: Options for an, OECD Publishing, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policyresponses/supporting-people-and-companies-to-deal-with-the-covid-19-virus-options-for-animmediate-employment-and-social-policy-response-d33dffe6/.

[2] OECD (2020), Tax and fiscal policy in response to the Coronavirus crisis: Strengthening confidence and, OECD Publishing, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/tax-and-fiscal-policy-in-response-to-thecoronavirus-crisis-strengthening-confidence-and-resilience-60f640a8/#section-d1e450.

[4] OECD (2020), Women at the core of the fight against COVID-19 crisis, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/women-at-the-core-of-the-fight-against-covid-19-.

[45] OECD (2019), 5th OECD Expert Group Meeting on Open Government Data: Summary Record, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/governance/digital-government/5th-oecd-expert-group-meeting-onopen-government-data-summary.pdf.

[21] OECD (2019), Fast Forward to Gender Equality: Mainstreaming, Implementation and Leadership, OECD, OECD Publisher, https://doi.org/10.1787/g2g9faa5-en.

[34] OECD (2019), Government at a Glance 2019, OECD Publishing, http://, https://doi.org/10.1787/8ccf5c38-en.

[44] OECD (2019), OECD Open, Useful and Re-usable data (OURdata) Index: 2019, OECD Publishing, http://www.oecd.org/gov/digital-government/ourdata-index-policy-paper-2020.pdf.

[43] OECD (2019), The Path to Becoming a Data-Driven Public Sector, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/059814a7-en.

[24] OECD (2018), Assessing Global Progress in the Governance of Critical Risks, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264309272-e.

[52] OECD (2018), Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work: The OECD Jobs Strategy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264308817-en.

[13] OECD (2018), SMEs in Public Procurement: Practices and Strategies for Shared Benefits, OECD Public, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307476-en.

[19] OECD (2017), 2013 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Education, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264279391-en.

[15] OECD (2017), The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264281318-en.

[20] OECD (2016), 2015 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Public Life, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252820-en.

[32] OECD (2015), Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Public Life, OECD Publishing.

[53] OECD (2014), “The crisis and its aftermath: A stress test for societies and for social policies”, in Society at a Glance 2014: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/soc_glance-2014-5-en.

[51] OECD (2010), OECD Employment Outlook 2010: Moving beyond the Jobs Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2010-en.

[10] Piquero, A. et al. (2021), Domestic Violence During COVID-19: Evidence from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Council on Criminal Justice, https://cdn.ymaws.com/counciloncj.org/resource/resmgr/covid_commission/Domestic_Violence_During_COV.pdf .

[55] Respect (2020), Respect’s Response to the Home Affairs Calll for Evidence COVID-19 Preparedness, https://hubble-liveassets.s3.amazonaws.com/respect/redactor2_assets/files/136/Home_Affairs_Call_for_Evidence_Covid.

[14] Rimmer, S. (2017), Gender-smart Procurement Policies for Driving Change, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/Gendersmart%20Procurement%20-%2020.12.2017.pdf.

[49] Sierra, E. and F. Boehm (2015), “The gendered impact of corruption: Who suffers more- men or women?”, U4 Brief, Vol. 9.

[47] Statistics Canada (2020), Disaggregated data for diverse population groups, https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/topics-start/gender_diversity_and_inclusion.

[30] Taub, A. (2020), Why Are Women-Led Nations Doing Better With Covid-19?, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/15/world/coronavirus-women-leaders.html.

[50] Transparency International (2020), COVID-19 makes women more vulnerable to corruption, https://www.transparency.org/en/news/covid-19-makes-women-more-vulnerable-to-corruption.

[18] UN Women (2020), Ipsos survey confirms that COVID-19 is intensifying women’s workload at home, https://data.unwomen.org/features/ipsos-survey-confirms-covid-19-intensifying-womens-workload-home.

[5] United Nations (2020), Policy Brief: The Impact of Covid-19 on Women, https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/04/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women#view.

[38] Welsh Government (2020), Leading Wales out of the coronavirus pandemic-A framework for recovery, https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2020-04/leading-wales-out-of-the-coronaviruspandemic.pdf.

[6] Wenham, C., J. Smith and R. Morgan (2020), COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak, Lancet Publishing Group, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2.

Annex 1.A. Key country measures to uphold gender equality during the COVID-19 pandemic

As reported during the proceedings of the extraordinary meeting of OECD Working Party on Gender Mainstreaming and Governance and in response to the OECD survey “Mapping good practices and challenges faced by the National Gender Equality Institutions in tackling the effects of COVID-19,” in April 2020.

Policies for addressing gender-based violence

Country responses to gender-based violence (GBV) range from introducing new policy and legal mechanisms to tackle the increasing cases and facilitate access to assistance and shelters for survivors/victims, to boosting the capacity of agencies and organisations working with survivors/victims and other women facing the threat of violence.

Policy and legal mechanisms and tools

A measure taken by several countries (e.g. Mexico, Norway and Spain) is declaring agencies and organisations that provide assistance to survivors/victims of violence as essential services to ensure continued access to aid despite restrictions on movements. Examples of countries that have introduced new institutional or policy mechanisms to tackle GBV in the face of the pandemic include Chile and Spain (with contingency plans to respond to domestic violence), Lithuania (with an inter-institutional plan on the prevention of domestic violence), and Switzerland (with a national taskforce on domestic violence representing federal offices headed by the Federal Office for Gender Equality). In Sweden, the Minister for Gender Equality has had meetings with organisations and authorities that work on this issue to monitor the situation. Australia also announced an AUD 150-million domestic violence package to provide critical emergency response services.

Access to helplines

While a number of countries have introduced helplines for women facing violence (e.g. Chile, Egypt, France, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovak Republic, Spain and Tunisia), due to the nature of emergency responses, confinement with the perpetrator discourages the use of these helplines. Many countries are finding innovative means to provide women access to help. These include alternative helplines that have been set-up through WhatsApp and other social media (e.g. France, Slovak Republic, Spain and Turkey), SMS services (e.g. France and Turkey), and email services (e.g. Denmark, Greece and Japan). An innovative practice, as seen in Chile, France, and some regions and localities of Spain, is the use of the code word “Facemask 19” in pharmacies, which then identify the women seeking assistance. Italy has also engaged pharmacies to identify and assist women facing violence. In Lithuania, Slovenia and Tunisia, psychological support is also being provided through helplines. In Turkey, survivors/victims of violence calling the 183 Social Support Hotline can reach the relevant support personnel by pressing the “0” button, without waiting in the queue.

France, Slovenia, the United Kingdom and the United States and have reported increasing capacities of these helplines through funding and resources.

Another measure employed in some countries (e.g. Austria, Finland, France and Slovenia) involves awareness, outreach and helplines targeted to men prone to violence to encourage them to seek psychological and behavioural help.

Awareness campaigns

A number of countries, including Austria, Czech Republic, Greece, Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, are conducting awareness campaigns through different media, including websites, online platforms and local-level enterprises like pharmacies and public transport networks, to encourage women to seek out help, while also targeting bystanders to increase reporting and prevention efforts. Another important component of these awareness campaigns is the provision of up-to-date information on assistance services and authorities to be contacted by women facing violence.

Agencies and organisations working with women

Several countries highlighted the legal and justice component of the increase in domestic violence, emphasising guidance, training and capacity building of the police and legal aid teams. Efforts to this extent have been taken in Czech Republic, Finland, Greece, Ireland, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway and Slovenia, including sensitivity-training and guidelines to the police to prioritise cases of domestic violence. Many countries (e.g. Austria, Czech Republic, Greece, Lithuania and Norway) have reported reinforced police mobilisation and institutional cooperation with other relevant services to facilitate access to justice.

Countries, including Canada, Denmark, Italy, Slovak Republic, Turkey and the United States, are monitoring the availability of resources and capacity of shelters and assistance centres. In Norway, employees working at shelter services for women facing violence have been provided access to childcare services facilitated for essential workers. To boost the capacity of assistance centres, shelters and organisations working on domestic violence issues, countries like Canada, Denmark, France, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Sweden and Turkey have earmarked monetary support.

Other measures

Along with the aforementioned measures, countries continue to use innovative policies and measures to alleviate the impact of emergency responses on women facing violence. Lithuania and Tunisia are planning to allow accommodations reserved for isolation and quarantining to be used as shelters for survivors/victims. Turkey has provided additional and temporary accommodation solutions (e.g. guest houses, dormitories and hotels) in order to minimize the risk of transmission in the women’s shelters. France has developed a guidance platform aiming at offering additional and temporary accommodation solutions (e.g. hotels and shelters) to abusers in April 2020, to enable the eviction of violent partner’s eviction as per the rule. Korea, recognising the increase in digital sex crimes, has undertaken proactive efforts to tackle this (e.g. protection of children and youth and deleting of pictures). To encourage identification of families and personnel facing violence at home, Chile and the Netherlands are engaging with private sector networks and professionals (e.g. human resources) who are likely to come in contact with families experiencing violence to detect signs of GBV, while Spain has produced guidelines for action aimed at survivors/victims of GBV, particularly with regards to domestic violence, trafficking and sexual exploitation.

Financial measures targeted at women

To the extent that women’s businesses are more vulnerable to the pandemic than men’s, financial measures and subsidies announced by certain countries are likely to be particularly valuable for self-employed women. For example, Spain announced a special subsidy for registered domestic workers to compensate for their inability to work during confinement. Canada has announced several schemes to support small entrepreneurs (e.g. interest-free loans and better access to financing), while Mexico has increased the loan payback time for small entrepreneurs. Italy has also increased funding for small- and medium-sized enterprises owned by women

Czech Republic, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania and the United Kingdom have also ensured schemes to support self-employed people16.

Other measures include expansion of criteria for eligibility or expedition of process for the proposed financial measures and subsidies, as seen in Australia, Czech Republic, Mexico and Turkey. Furthermore, Spain approved a Minimum Living Income whose eligibility criteria includes certain requirement exemptions for women who are survivors/victims of GBV.