Abstract

In response to the challenges resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, governments are looking to their Export Credit Agencies (ECAs) to fill any financing gaps left by the private market and to mitigate the impact of the crisis by engaging in both short-term (ST) and medium- and long-term (MLT) trade finance. In the absence of comprehensive data on trade finance, this brief uses OECD surveys and other related indicators to attempt to identify emerging trends. These indicators suggest that ST trade finance is facing access problems (increased costs of ST financing for SMEs and higher rates of rejected applications) while MLT trade finance appears to be relatively resilient (decrease of 34% in volume and 15% in number of MLT export credit transaction). ECAs may therefore have a role to play in ST trade finance by acting on liquidity and increasing capacity. However for MLT trade finance, ECAs might have fewer levers for action, especially if the pandemic is affecting the demand side and reducing the pipeline of projects.

The Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has had a devastating effect on economies and societies worldwide: for 2020, the OECD estimated a reduction of global GDP by 3.4% (OECD, Mar 2021[1])and a contraction of global trade by 10.9% (OECD, Dec 2020[2]). In the face of such negative economic outlooks, governments are under pressure to mobilise tools and develop policies that will counter, or at least alleviate, the economic impact of the pandemic.

At the forefront of governments’ concerns is maintaining trade flows and consequently trade finance, which serves as the lifeblood of day‑to-day international trade by providing the fluidity and security needed to allow for the movement of goods and services (OECD, May 2020[3]). However, trade finance is known to be particularly vulnerable in times of economic crisis. In past crises (especially during the Great Recession of 2007-2009), the mobilisation of government export support programmes designed to fill the gaps in private market financing proved successful in countering the decrease in private market trade finance. With this in mind, governments are again looking to these programmes to help alleviate the trade disruptions created by COVID-19.

However, compared to the previous crises, the COVID-19 crisis is different insofar as it represents a single unforeseeable shock, and therefore, unlike most recessions, it is not a self-fulfilling prophecy phenomenon (John Hassler, Jul 2020[4]). This means that governments may not be able to solely rely on the knowledge gained from past crises to counter its negative effects: the type and size of the disruptions caused to the trade world, and more specifically to the trade financing world, are likely to be different than in the past. Every effort must therefore be made to identify the disruptions so that governments can successfully mobilise the different tools that they have at their disposal, including export support programmes.

What is happening in short-term trade financing? (“Pressures on access to short‑term trade finance”)

Short-term (ST) trade finance products which enable deferred payment over a period of less than one year (usually less than 180 days) are the most common form of trade finance and are especially vulnerable during periods of uncertainty leading to increased prices and reduced overall availability (OECD, May 2020[3]). Little data is publicly available for ST trade finance as the vast majority is provided by the private sector and comes in numerous forms (intra-firm financing, inter-firm financing, or more dedicated tools such as letters of credit, advance payment guarantees, performance bonds, and export credit insurance or guarantees).

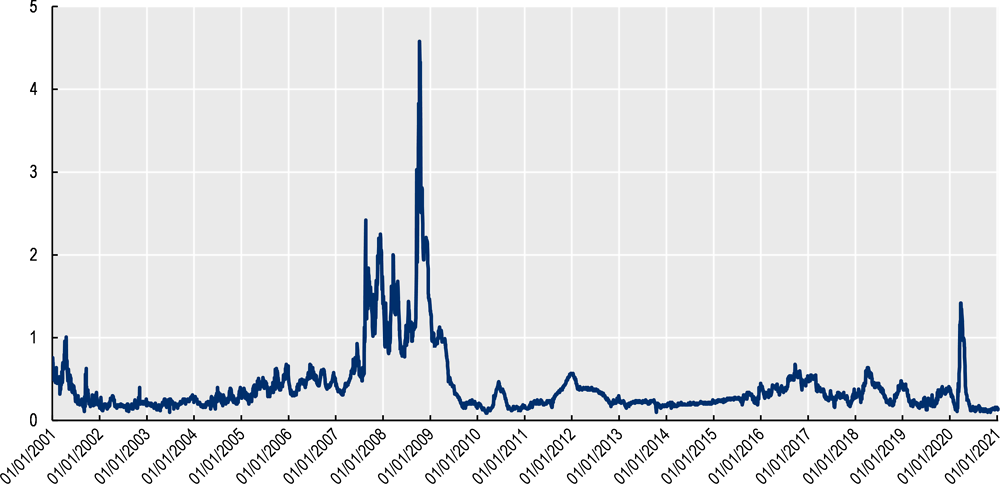

In past crises, and more notably during the 2007-2009 Great Recession, ST trade finance declined sharply due to pressures on private institutions’ liquidity, leading to elevated costs of trade finance. However, commercial banks’ liquidity does not appear to be a problem in the wake of COVID-19. Indeed, “after ten years of tightening regulation, capital buffers are higher and the banking system are generally seen as safer” (Richard Baldwin, 2020[5]). In fact, the level of the TED spread (difference between the interest rates on interbank loans and ST U.S. government debt), which is usually a broad liquidity indicator of ST trade finance, has been on average very low. Although the TED spread initially rose up to 1.46% (its highest level since the 2007-2009 crisis) at the beginning of the pandemic, it quickly dropped to its pre-pandemic levels and has remained low ever since (Figure 1) This would suggests that, contrary to what was observed during the 2007-2009 Great Recession, the cost of ST trade liquidity has not increased and financing opportunities should be available to exporters.

Calculations based on the Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TEDRATE.

Nonetheless, exporters are facing difficulties accessing ST financing in the private market. In the United States, the Wall Street Journal (Julie Steinberg, Sep 2020[6]) reported a 60% increase in rejected applications for trade credit insurance. In addition, the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) reports a retrenchment of banks from financial sectors deemed “high risk” as well as increases in the price of ST financing for SMEs (ICC, Nov 2020[7]). On the other hand, government-supported Export Credit Agencies (ECAs) are seeing an increase in the demand for their short‑term products. According to an OECD survey1, 43% of ECAs have reported an increase in their business levels, mostly in connection with short‑term products. The Export-Import Bank of the United States (US EXIM), one of the largest providers of ST government export support,2 reported a 112% increase in working capital guarantees and a 12% increase in ST export credit insurance during the 2020 fiscal year (Exim Bank, Jan 2021[8]).The German ECA (Euler Hermes) reported that it had seen a sharp increase (by more than a third) in the number of applications for export credit guarantees for the first half of 2020 (Euler Hermes, 2020[9]). These trends suggest that even though commercial lenders may have adequate liquidity to provide financing to exporters, their risk appetite may have diminished resulting in limited availability of trade finance for exporters and a shift towards governments acting through their ECAs.

ECAs relying on liquidity support and increased capacity to mitigate ST financing disruptions

The underlying reasons for the disruption of ST trade finance are different than those of past crises; however, the result is the same: exporters are facing barriers in accessing ST financing. Since ECAs expected a significant shortfall in the private market supply for ST financing based on their experience in the last crisis, they have been acting quickly to fill the gap by mobilising their export support programmes.

First, in order to mitigate the ST liquidity problems faced by exporters and their supply chains, ECAs have been boosting their working capital support programmes. These programmes, which take the form of an insurance or guarantee to financial institutions on behalf of exporters, provide exporters with liquidity to finance the costs incurred by the exporter to produce goods for export. According to an OECD survey1, 64% of ECAs indicated that they took measures aimed at increasing working capital support. These measures included increasing the capacity or expanding the coverage of existing working capital programmes and creating new working capital facilities.

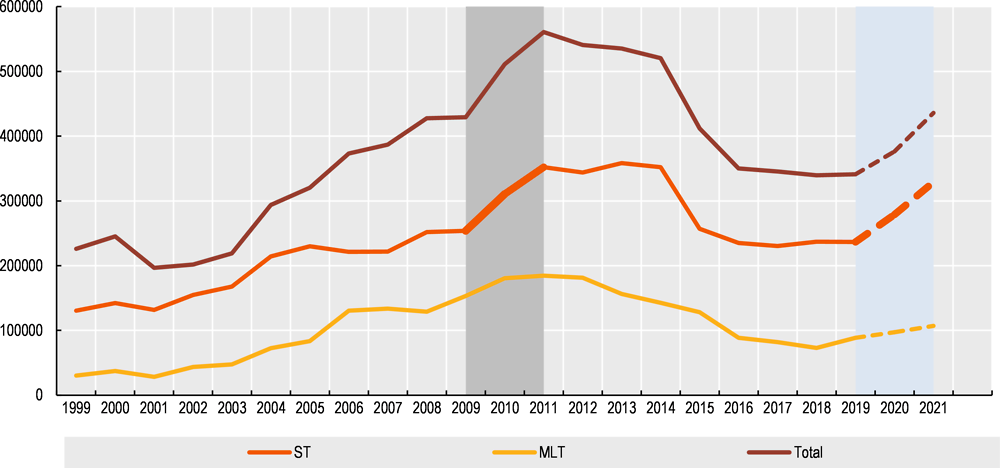

In addition, ECAs have endeavoured to fill the gap left by the private market in ST trade finance by increasing the availability of government ST support programmes, such as export credit insurance or guarantees3. To that end, many ECAs have increased the capacity of existing programmes, created new facilities and extended their limits of cover to include new risks. For example, the European Commission decided to make ST export credit insurance more widely available by temporarily removing all countries from the list of “marketable risk” countries, which are normally ineligible for public support, until the end of 20214. Increasing capacity was particularly effective for the recovery in the aftermath of the 2007‑2009 Great Recession (new risks covered in ST increased by 22% in 2010 and 13% in 2011 ‒ see Figure 2) and is likely to be crucial during the current COVID‑19 crisis, as the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) anticipates that USD 1.9-5.0 trillion capacity in trade credit market will be required to enable a rapid recovery.

The projection in 2020 and 2021 is based on the average growth rates observed in 2010 and 2011 to show what the effects would be if ECAs’ reactions have a similar impact on activity.

Calculations based on the OECD 2019 Cash flow Report, http://www.oecd.org/trade/topics/export-credits/statistics/.

ECAs are also counting on simplified procedures and expedited processes to facilitate the provision of trade financing support to ensure that the gaps in private market financing are filled expeditiously. According to both OECD1 and Berne Union (Berne Union, 2020[10]) surveys, most ECAs have developed fast‑track policy approval processes, deployed contactless application processes, provided deadline extensions to policy holders, and extended time for notification and claims filling.

However, ECAs do not have free range with regards to how they develop or amend their export support programmes, especially those targeting short‑term transactions. Indeed, such programmes are bound by the World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (ASCM), according to which export support programmes dependent on export performance (i.e. tied to national goods being exported) and for which the cost of the support is lower than that which is offered by the commercial market are regarded as prohibited subsidies. Therefore, in order to avoid the possibility of a WTO dispute, governments must keep these considerations in mind when amending or creating new programmes, even if they are reacting to a crisis.

Finally, regardless of constraints related to the supply of trade finance, it is also likely that the pandemic has produced a shock on demand as well as production, thereby reducing exports and leading to disruptions in the supply chain. In this scenario, ensuring that a sufficient amount of ST financing is available through export support programmes will not be sufficient to maintain trade flows. Availability of finance does not create demand.

What is happening in MLT export financing? (“Relative resilience”)

Medium- and long-term (MLT) export financing is primarily used for the financing of capital equipment either alone or as part of large projects (e.g. infrastructure, manufacturing, oil and gas, etc.) which require longer repayment periods. This type of support consists primarily of buyer credits that allow foreign buyers to access MLT financing to purchase exporters’ products and services. The public sector, including ECAs and multilateral organisations, is much more present in MLT financing than in ST financing, notably through the provision of export credits compliant with the Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits (the Arrangement5). Although the capacity of private market MLT financing has been growing (Berne Union, 2021[11]), private market financing options remain limited in part due to the financial regulatory framework applied to private institutions, such as Basel and Solvency risk assessment standards, which de facto limits market capacity, and also because these complex transactions are deemed riskier in terms of size, structure and location by the private sector.

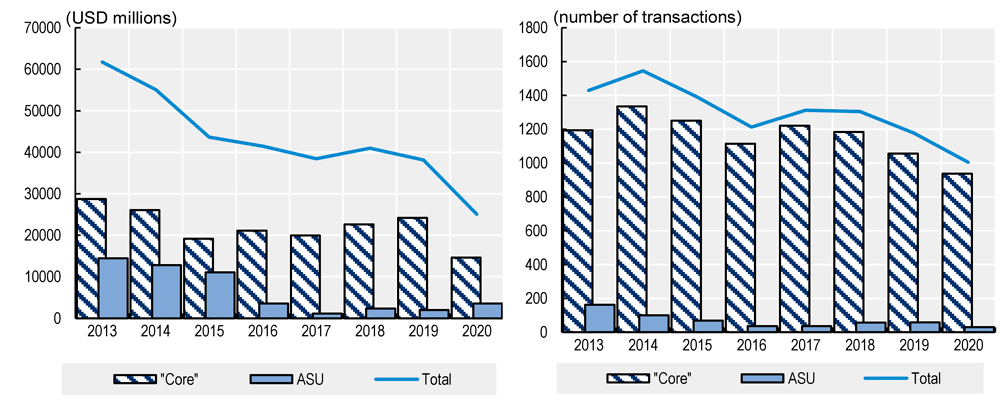

Although there is no comprehensive data on MLT export financing, there is data on export credits provided by OECD countries according to the terms and conditions of the Arrangement which can provide an interesting insight with respect to the emerging trends in MLT export financing. However, the data on export credits provided in 2020 is currently incomplete due to lags in reporting, which on average extend to three months. In order to have a sense of the emerging trends as a result of the pandemic despite this lag, it is necessary to adjust the data6. When looking at this adjusted data it appears that both the volume of export credits and the number of transactions have decreased in 2020, with -34% in volume and -15% in number of transactions (Figure 3). This is in line with the numbers reported by the Berne Union [17% decrease in the amount of new MLT commitments for the first half of 2020 (Berne Union, 2020[12])].

The recent business reports published by some of the major ECAs seems to support the observations made from the aggregate data. Indeed, for the first half of 2020, the German ECA (Euler Hermes) reported a decline in the volume of cover due to the lower number of big-ticket projects, especially in the transportation sector which has been hit particularly hard by the pandemic (cruise ships, aircraft) (Euler Hermes, 2020[9]). The Canadian ECA (EDC) has seen its financing and investment activity decrease by 16%, primarily due to a 30% decrease in direct lending as a result of decreases in the oil, gas and mining sector during the first three quarters of 2020 (EDC, 2020[13]).

“Core business” refers to official export credits supported according to the rules found in the body of the Arrangement or one of the following annexes: (1) nuclear power plants, (2) renewable energy, climate change mitigation and adaption, and water projects, (3) rail infrastructure, (4) coal fired electricity generation projects or, (5) project finance transactions. "ASU" business refers to aircraft supported under the terms and conditions of the Aircraft Sector Understanding.

Calculations based on the OECD data on officially supported export credits, http://www.oecd.org/trade/topics/export-credits/statistics/.

According to Figure 3, the amount of officially supported export credits for aircraft transactions has decreased in 2020 and so has the number of transactions supported. However, the decrease observed is mild compared with how severely the aircraft sector has been hit by the crisis. This can be explained by the fact that the support for aircraft was already very low over the past four years. The low volume of support for aircraft between 2016 and mid-2019 is largely due to the unusual constraint on the Export-Import Bank of the United States (“US-EXIM”), one of the major export credit providers for aircraft, from July 2015 until May 2019.1 In addition, the decision made by France, Germany, and the United Kingdom in 2016 to suspend temporarily their support for Airbus transactions, also contributed to the sharp decline of aircraft supported over the last few years.

US-EXIM’s charter expired without being reauthorised on 30 June 2015, this prevented US-EXIM from providing any official export credits until 4 December 2015 (when its charter was reauthorised). However, even then, due to the absence of the necessary Board quorum, US-EXIM could not support transactions with a credit value over USD 10 million until 19 May 2019, when the quorum was re-established (following the confirmation by the Senate of three members on US-EXIM’s board).

However, based on the severity of the crisis triggered by COVID-19, a much stronger inflection of the curves might have been expected: a sharp decrease as a result of the shock in the supply and demand curves, followed by an important increase as exporters shift from private finance to government backed support in reaction to the contraction of private finance opportunities. Therefore, based on preliminary trends, the impact of the crisis on MLT export finance would appear relatively limited. In fact, EDC reported an increase in both project finance (1.1%) and loan guarantees (64%) through the third quarter of 2020 and US-EXIM also reported an increase in its authorisation for MLT guarantees.

The trends going forward? (“Pressures on cash flow, reduced pipeline”)

As the crisis triggered by the pandemic continues, it is expected that the pressure on buyers (e.g. the demand side of the equation) will increase, especially for larger transactions (such as infrastructure projects) which had appeared relatively resilient so far. Indeed, with COVID-19, some infrastructure assets (hospitals, ports) have seen their operations redirected to support governments’ response to the crisis. In addition, the crisis has led buyers’ revenues to plummet, especially in certain sectors which have been hit particularly severely by the crisis (such as the transportation and tourism sectors). This is expected to weigh on exporters’ long-term cash flows, as they struggle to maintain business volumes.

At this stage of the crisis, these pressures on the buyers do not seem to have led to an increase in claims and default situations. According to an OECD survey,1 75% of ECAs surveyed did not report an increase in claims. This is also supported by the Berne Union data, according to which ST and MLT claims reported by ECAs over the first half of 2020 have remained relatively constant compared to 2019 (Berne Union, 2020[12]). However, there has been an increase in the request for payment deferrals. Indeed, the Swedish ECA (EKN) noted in their interim report for 2020 an increasing number of applications for payment deferment both in SME working capital financing and payments from the international customers of large corporates (EKN, 2020[14]). ECAs have acted on these pressures by introducing waivers in premium and fees for restructurings and facilitating the deferral of payments when possible. Governments have also attempted to provide co-ordinated actions to alleviate the pressure on buyers’ liquidity, with for example the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), which consists of a temporary moratorium of payments by sovereign borrowers between 1 May 2020 and 30 June 2021 (including medium/long term export credits) for the poorest countries who request it.

ECAs have at their disposal a few other tools that they can mobilise should the need for further payment flexibilities in MLT transactions arise. Indeed, the Arrangement, which regulates official MLT export credits provided by OECD ECAs, has some imbedded flexibilities that can be used by ECAs. For instance, the Arrangement has a clause which allows for the use of more liberal terms and conditions in order to “preserve a credit”, e.g. to minimise losses should a claim or a non-payment occur in an existing transaction. In addition, the repayment rules of the Arrangement can, under certain circumstances, allow for new transactions to defer the first repayment of the principal up to one year. However, these levers might not be sufficient in providing the flexibilities required should the crisis continue. For instance, due to shortfalls in revenues and cost increases for infrastructure projects, relevant companies might need more flexibility concerning the repayment schedules (e.g. grace period), repayment tenors, or the down payment rules which would require amending the Arrangement. Indeed, Business at OECD (BIAC), an international business network, appealed for temporary flexibility of the down payment requirements for projects in emerging and developing markets in July 2020 (Business at OECD, EBF and ICC, Jul 2020[15]). The OECD, as the main forum to maintain, develop and monitor export credit disciplines, could facilitate these discussions and help governments reach a consensus should the need arise.

However, there is only so much that ECAs can do to their export support programmes to mitigate the pressures faced by buyers and avoid contract renegotiations and debt restructurings which become more likely as the crisis continues (World Bank Group, Jul 2020[16]). In fact, acting on export support programmes may have very little to no impact in the near term if the pressures triggered by the pandemic on buyers’ revenues and investors’ risk appetite lead to the cancellation of prospective projects due to project viability. According to the Global Investment Trends Monitor, Global Foreign Direct Investment in 2020 fell by 42% and is likely to remain very weak in 2021, which is evidence that the funding demand of projects will be lower in the coming years and therefore that the pipeline of projects will be slower. If this is the case, governments will need to turn to different types of tools to stimulate demand in order to avoid a slowdown of trade and a further deterioration of the economy.

Conclusion

Macroeconomic indicators show that the pandemic has severely impacted the global economy and, more specifically, international trade. However, information remains limited on the level and on the type of the disruptions that have emerged, as comprehensive data on trade finance does not exist. Nonetheless, information from surveys and other related indicators allow for some emerging trends in trade finance to be identified. ST trade finance appears to be the most affected by the crisis, in part due to pressures on the access to trade finance opportunities caused by the diminished risk appetite of the private market. Governments acting through their ECAs can attempt to alleviate these barriers by providing liquidity to exporters (for example via working capital programmes, as has already been done by 64% of ECA according to an ECA survey1) and increasing the availability of export support programmes. In contrast, MLT financing appears to have been more resilient to the current crisis. The number of MLT export credit transactions are expected to decrease by 34% in volume and 15% in number in 2020, which indicates a drop in large projects but not in standard medium term business. However, this apparent resilience may not last should the pandemic continue and weigh further on cash flows of MLT projects. In order to avoid these future impacts, ECAs may need to achieve further flexibility in their MLT export support programmes by amending their terms and conditions, either through available flexibilities in the Arrangement or by revising it. The OECD can assist governments in this work. Governments may also need to look to other tools in order to fight the pressures on the demand side which are likely to affect MLT trade as much, if not more, than the supply/financing side should the crisis persist.

References

[11] Berne Union (2021), About Export Credit Insurance, https://www.berneunion.org/Stub/Display/17.

[10] Berne Union (2020), Export Credit Insurance, Industry response to Covid-19, https://www.berneunion.org/Articles/Details/506/Robust-response-to-the-COVID-19-pandemic-from-the-export-credit-insurance-industr.

[12] Berne Union (2020), Yearbook 2020, https://www.berneunion.org/Publications.

[15] Business at OECD, EBF and ICC (Jul 2020), Joint Business Position: Export Credits and Covid-19, https://biac.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/FINAL-Joint-business-position-on-Covid-19-and-Export-Credits-1.pdf.

[13] EDC (2020), Growing Canadian Trade Responsibly - Quarterly Financial Report, https://www.edc.ca/content/dam/edc/en/corporate/corporate-reports/quarterly-reports/quarterly-report-q3-2020.pdf.

[14] EKN (2020), Interim report : January- August 2020, https://www.ekn.se/globalassets/dokument/rapporter/delarsrapporter/en/interim-report-january-august-2020.pdf/.

[9] Euler Hermes (2020), Export Credit Guarantees - Interim Report 2020, https://www.agaportal.de/_Resources/Persistent/f1ac3248303281c85ae7a2c8d80065bd48e387f0/e_hjb_2020.pdf.

[8] Exim Bank (Jan 2021), 2020 Exim Bank Annual Report, https://www.exim.gov/news/reports/annual-reports.

[7] ICC (Nov 2020), Priming Trade finance to safeguard SMEs and Power a resilient recovery from Covid-19, https://iccwbo.org/content/uploads/sites/3/2020/11/memo-g20-recommendations-smes.pdf.

[4] John Hassler, P. (Jul 2020), Economic policy under the pandemic: A European perspective, https://voxeu.org/article/economic-policy-under-pandemic-european-perspective.

[6] Julie Steinberg, J. (Sep 2020), “Insurance Freeze Snarls U.S. Supply Chains”, Wall Street Journal, https://www.wsj.com/articles/insurance-freeze-snarls-u-s-supply-chains-11600772974.

[1] OECD (Mar 2021), “Economic Outlook, Interim Report”, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/oecd-economic-outlook/volume-2020/issue-2_34bfd999-en;jsessionid=ei_e04qTbcgZAUCKODeFu_aF.ip-10-240-5-119.

[2] OECD (Dec 2020), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2020 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/16097408.

[3] OECD (May 2020), Trade Finance in times of Crisis - responses from Export Credits Agencies, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/trade-finance-in-times-of-crisis-responses-from-export-credit-agencies-946a21db/#biblio-d1e581.

[5] Richard Baldwin, E. (2020), Economics in the times of Covid-19, CEPR Press, https://innowin.ir/api/media/BQACAgQAAx0CPPk4JwACHxZeusXcwX.pdf#page=66.

[16] World Bank Group (Jul 2020), Infrastructure financing in times of COVID-19: A driver of recovery1, http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/424911600887428587/Infrastructure-financing-in-times-of-COVID-19-A-driver-of-recovery.pdf.

Notes

OECD countries have been responding to this survey on an ongoing basis. The results presented in this brief reflects the responses provided as of 22 February 2021.

Other than Asian ECAs where the private market is relatively smaller.

Export credit insurance/guarantees cover an exporter’s foreign accounts receivable against commercial (i.e. non‑payment) and political (e.g. expropriation, political violence, sovereign debt default, war) risks.

The Arrangement is a gentleman’s agreement which places limitations on the financing terms and conditions to be applied when providing official export credit support with a repayment period of two years or more.

The most recent database reflects submissions provided up until 31 December 2020, in order to make an accurate comparison with previous years, the data pool of past years has been restricted to export credits reported up until the end of December for each year.