Copyright: Shutterstock

Nick Malyshev, Guillermo Hernández, Ruben Maximiano, Leni Papa [OECD]

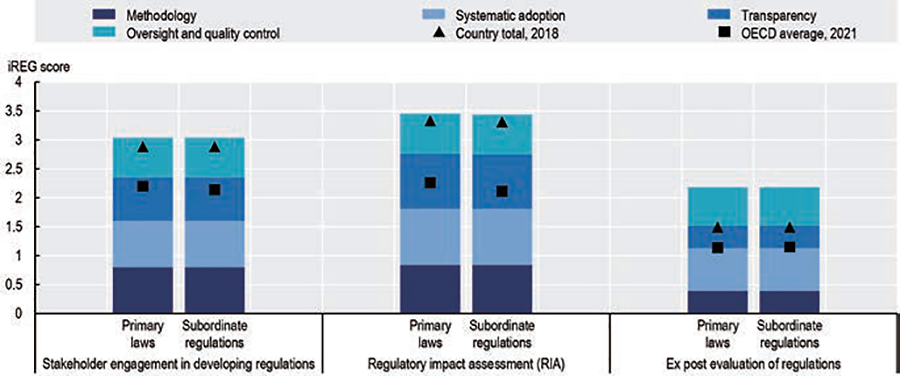

At the time of Korea’s accession to the OECD in 1996, regulatory reform was likely a novel idea. Korea was among the first countries to undergo a regulatory reform review in 2000. Recommendations from two subsequent reviews (2007 and 2017) have further guided the Korean government in consolidating and pursuing reform efforts. Successive governments have been highly active in implementing measures to promote regulatory reform and have made impressive progress to improve Korea’s regulatory quality system over the years. The 2021 OECD Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance (iREG) show that Korea has successfully established the institutions, processes and tools to support good regulatory practices over the last 25 years. While there is always room for improvement on the quality of these practices, Korea should rightly be proud of its trajectory on regulatory reform.

Note: The more regulatory practices as advocated in the OECD Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance a country has implemented, the higher its iREG score. The indicators on stakeholder engagement and RIA for primary laws only cover those initiated by the executive (4% of all primary laws in Korea).

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2017 and 2021, http://oe.cd/ireg.

Introduction

Korea had experienced unprecedented economic growth in the years leading up to joining the OECD. However, it had done so on a model of so-called authoritarian capitalism, in which enterprises were privately owned but managed jointly between the government and its owners. Korea faced major domestic regulatory challenges as it joined the OECD as well as the headwinds of ever-increasing globalisation.

These challenges required profound changes to the state. President Kim Dae-Jung prophetically stated in 1998, “Any reform undertaken in Korea must begin with the government.” Thus, less than two years after joining the OECD, a major programme was launched with the aim of changing the role of the state in Korean economy and society. The government adopted far-reaching plans for administrative reform that eliminated unnecessary rules, produced a smaller and more efficient administration, incorporated competitive principles in government, and created a “customer orientation” within the administration.

Korea has made impressive progress over the years in terms of introducing policies, institutions and tools to assure high quality regulation. The original impetus for reform was to strengthen the Korean economy through deregulation and to facilitate recovery from the economic crisis of the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997. That crisis provided the opportunity for the administration to undertake significant changes; steps were taken to reduce the number of regulations in place, and many new programmes and tools to promote regulatory quality were established.

Korea undertook further extensive reforms in the wake of the Financial Crises of 2007-08. While it maintained its commitment to the overall trajectory of regulatory reform, it introduced the Temporary Regulatory Relief (TRR) programme in May 2009. This programme suspended and delayed the application of 280 regulations for two years, until the economy had recovered from the crisis. The programme was successful in bolstering private sector investment and consumption and reducing the regulatory burden on small and medium enterprises.

Korea was also quick out of the blocks in its regulatory response in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. To boost testing capacity for the pandemic response, unlike many other countries, Korea removed regulatory barriers that limit the participation of public or private laboratories in providing testing services. Having learned from previous crises (MERS in particular), Korea enlarged its testing network to encompass all laboratories with appropriate capacity, as well as removing barriers that could limit the opening of “off-premises” locations (e.g., testing has involved innovative methods such as drive-through and walk-through testing facilities).

Korea has been a prime example of a country not letting a crisis go to waste within the regulatory realm. Successive governments have also been highly active in implementing measures to promote regulatory reform and have made impressive progress to improve Korea’s regulatory quality system over the years. However, there remains scope to consolidate the gains that have been made to date and to improve further in a dynamic policy field where the frontiers of the state-of-the-art are still being defined. In addition, many of these regulatory reforms are still relatively nascent and so have not yet become part of the administrative culture, particularly at the lower levels of the administration. The Korean government has made efforts to give guidance and training in regulatory management tools biannually, especially to sub-national officials accountable for promoting the progress on regulatory reform.

The sections below provide a more granular analysis of key elements of regulatory policy and governance in Korea: leadership and oversight of regulatory reform, regulatory impact assessment (RIA), transparency and predictability, and regulatory performance assessment.

Leadership and oversight of regulatory reform

Appropriate institutions and leadership thereof are central to a successful and on-going programme to ensure regulatory quality. Responsibility for the various aspects of regulatory policy and governance should be clearly allocated to institutions across the government administration, which should in turn be sufficiently resourced to fulfil their responsibilities. The appropriate institutional structure is also important in ensuring that the reform process is transparent and that those making the decisions are accountable for their actions.

Korea’s presidential system has made it easier to promote regulatory reform, which has been a crucial factor in sustaining progress against—at times—strong opposition. One of the great strengths of Korea’s regulatory reform agenda has been the prominent personal leadership role of the president in all administration since joining the OECD. Sustaining reform against domestic opposition will continue to rely on strong political leadership.

The Regulatory Reform Committee (RRC) is the most important body at the working level and provides regulatory oversight across the whole administration. The RRC’s general mandate is to develop and co-ordinate regulatory policy and to review and approve regulations. The RRC operates under the authority of the President with a secretariat function supporting it work through the Regulatory Reform Office (RRO), which is located in the Prime Minister’s Office.

The RRC has been a crucial element in the achievement of rapid regulatory reform and will continue to be essential to further progress. Over 3,500 proposals are received every year by the RRO from all central administrative regulations. Among the reviewed proposals, around 1,000 proposals (proposals that contain regulations) are transferred to the RRC. Performing a complete review for over 1,000 proposals may serve as a daunting task for the RRC, which handles an extremely high load of oversight relative to other OECD countries.

The RRC is divided into the Economic Sub-Committee and the Administrative and Social Sub-Committee, which separately review regulations according to their nature. Members of the RRC are from both the government and non-government sectors, and their participation in the committee is done on a part-time basis. The RRC meets twice a month to deliberate on significant regulations.

The RRC’s area of responsibility is to play the oversight of regulation prepared by government ministries. This is a prominent issue because under the Korean system of government, congress members themselves can introduce bills directly into the Parliament (National Assembly). The percentage of primary laws initiated by National Assembly has increased from 38.5% in 2000 to 75% in 2007, and to 90% and 86% in 2015 and 2016, respectively. At present, most of the bills initiated by parliament lack the needed regulatory quality scrutiny or review. While the National Assembly has the potential to improve the quality of legislation through public hearings and the review of bills, there is no entity within the chamber that systematically oversees legislative improvements.

There is a network of officials working on regulatory issues across central administrative agencies and through committees. At the national level, around 90 members from the RRO and the Public-Private Joint Regulation Advancement Initiative (PPJRAI) work to co-ordinate and manage regulatory policies. This network is important to ensure quality of regulation and embed a culture of good regulatory practice across the government.

Korea has several research centres and institutes that provide a general research capacity to support central government agencies in their rule making activities. These agencies work in close collaboration with the central government reform agencies. As an example, the Korea Development Institute (KDI) is an important “think tank” founded in 1971 by government to undertake research, analysis and provide advice on a wide range of economic policy issues. The work of the KDI covers long- and short-term economic policy and development issues related to domestic Korean economic matters as well as international trade and development issues. The OECD has collaborated with the KDI on a regular basis and recently developed a series of case studies to document the regulatory challenges brought by innovation and the variety of existing and potential regulatory approaches that can help to address those challenges.

As part of a joint project, the OECD and the Korean Development Institute (KDI) have developed a series of case studies to document the regulatory challenges brought by innovation and the variety of existing as well as potential regulatory approaches that can help to address those challenges. These case studies are an example of mutually enriching efforts to develop a robust body of evidence on regulatory policy reform and combine the knowledge and experience of both Korea and the OECD to shed light on a variety of complementary insights. They cover the following areas: data-driven business models, digital innovation in finance, smart contracts relying on distributed ledger technologies, digital technologies for smart logistics and the sharing economy.

The different case studies illustrate difficulties for regulatory action to keep pace with the rapid pace of innovation and technological development. They also point to the blurring of traditional markets’ boundaries, which challenges the definition of regulators’ mandate, remits, and results in a number of enforcement challenges. Finally, they highlight the mismatch between the fragmentation of regulatory frameworks across jurisdictions and the strong transboundary effects of many innovations.

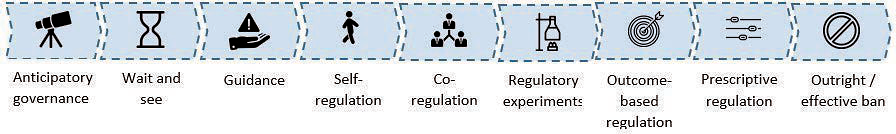

From the case studies, it also emerges that governments in the face of these challenges have implemented a variety of regulatory approaches (Below figure.) These notably include outright bans on the development and adoption of certain innovation; adopting a wait-and-see approach to discover which of the initially perceived risks end up materializing; the piloting of regulatory experiments such as the adoption of fixed-term regulatory exemptions for innovation that uphold overarching regulatory objectives such as consumer protection. Issuing guidance to help innovators understand how the regulatory framework applies to specific innovation and reduce the potential regulatory uncertainty regarding compliance with existing requirements is also an important option at hand.

Understanding regulatory effects: the use of Regulatory Impact Analysis

Effective tools and procedures are essential to ensure well-functioning and transparent regulatory processes. Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) is a crucial tool for ensuring that efficient and effective regulatory options are chosen. The value of the tool is reflected in the fact that most OECD countries have introduced a RIA system and Korea is no exception.

The Basic Act on Administrative Regulations that came into effect from 1 June 1998 established the Korean Regulatory Impact Analysis system. The government requires that a RIA be conducted for all types of legislation, including presidential decrees and ordinances. The RIA system is a multi-layered process of revision and improvement, which is carried out by the head of a central administrative agency, partially reviewed by concerned agencies such as Small and Medium Business Administration, Fair Trade Commission and Korea Agency for Technology and Standards (KATS), and previewed and verified by the two regulatory research centres at the Korea Development Institute (KDI) and the Korea Institute of Public Administration (KIPA). All drafted RIA statements are made public during the advance notice period of proposed legislation (over 40 days for legislative notice and 20 days.) These are subsequently reviewed by the internal regulatory reform committee of the concerned central administrative agency, and then fully reviewed by the RRC for significant regulations.

The e‑Regulatory Impact Analysis (e-RIA) was introduced in July 2015 to ease the process and improve the quality of the RIA system. This allows RIA statements to be drafted and processed online. The system compares regulatory costs and benefits associated with each alternative through an automatic data accumulation function. The system also helps enhance the quantification of the cost-benefit analysis.

For RIA, Korea requires analyses to be proportionate to the significance of the regulation and calls for alternative regulatory options to be assessed for all subordinate regulations. This allows for more systematic assessment and implementation. In 2020, Korea enhanced the RIA for SMEs by introducing the impact reporting system and revising a related guideline.

Transparency and predictability

Transparency is a key element of an efficient and effective regulatory process. A transparent process provides a form of quality check on new regulations. In addition, transparency ensures that those affected by the regulation understand why it is being introduced—it therefore reinforces the legitimacy and fairness of the regulatory process. Korea has taken concrete steps to improve transparency and consultation with affected groups.

Stakeholder engagement is a vital administrative process (and mind-set) to help improve transparency in the regulatory procedure. While Korea has a long tradition of public consultation, there is the need for greater emphasis on representation and ease of access. Efforts have been made to increase transparency and public access in the regulatory process through the various government portals, notably the Regulatory Information Portal, i-Ombudsman, and the online Regulatory Reform Sinmungo, with the latter also open to foreign nationals to provide feedbacks and suggestions.

The Regulatory Reform Sinmungo is an innovative and efficient tool to receive feedback on regulations and regulatory administration. Any petition on regulatory inconveniences or burdens can be submitted through this platform. Once a petition is filed through the system, the responsible official at the relevant central administrative agency accepts or declines the petition within 14 days. If the rejected petitions were deemed reasonable by the RRO, the responsible agency would need to justify the grounds for refusal within 3 months’ time.

The Regulatory Information Portal serves as a channel where people can participate in the regulatory reform process. The government launched the Regulatory Information Portal in 2014 to serve as a platform for public engagement in the process of regulatory reform. Upon receiving suggestions from the public or businesses, the agency responsible is strongly encouraged to reflect their opinions in the regulatory proposals. At the same time, if stakeholder engagement is reckoned insufficient, notably in the RIA process, the responsible agency is requested to revise the statement. Aside from serving as a communication platform, the Regulatory Information Portal also provides and advertises information on regulations, including successful cases on regulatory reform.

Government-wide efforts have been made to encourage public engagement in the regulatory reform process. In addition to the Regulatory Information Portal, the government, led by the RRC, has pursued several methods to increase participation in the regulatory reform processes.

The Korean government actively promotes recent regulatory reform achievements through official communication channels and in major public spaces employing public-friendly media (including infographic, card news, webtoons, among other).

During past years, Korea figured among the OECD countries with the highest share of population exposed to excessive PM2.5 (atmospheric particulate matter that have a diameter of less than 2.5 micrometres) concentrations and PM2.5 concentration level in Seoul is about two times higher than the WHO’s guidelines or the levels of other major cities in developed countries. A number of countermeasures have recently been introduced to address such challenges, many of them relying on regulatory policy tools.

Key recommendations for Korea to improve its air quality regulatory frameworks and ensure implementation of regulations include:

Building provincial and local governments’ capacity to carry out their statutory environmental responsibilities and tasks delegated to them by the central government; provide the necessary financial resources to ensure effective enforcement of national environmental regulations; strengthen the system of environmental performance indicators for all levels of government. Clearer and transparent rules for appointing and dismissal of the heads of environmental inspections could strengthen the independence of inspections and therefore decrease potential risks of manipulating inspections towards political goals of the local leadership.

Reinforcing ex ante assessment of environmental policies and regulations through wider application of quantitative cost-benefit analysis and expand ex post evaluation of their implementation. It is necessary to adopt regulations based on their necessity supported by evidence, rather than on simple accounting and offsetting of costs. A methodology for evaluating costs on environment should be included in the official RIA guidance.

Improving public participation in environmental decision making by introducing mechanisms for public involvement in the development of environmental permitting decisions, and by opening the environmental impact assessment process to input from the general public (beyond local residents) and NGOs. Better information on both goals of government policies and regulations but also on the regulation-making process and possibilities for stakeholders to participate in this process might lead to an increased trust in government and better perception of the quality of the regulatory framework among stakeholders.

Increasing the efficiency of compliance monitoring through better targeting of inspections based on the level of environmental risk of individual facilities; strengthen administrative enforcement tools and build the capacity of public prosecutors and the courts in applying penalties for criminal offences.

Pursuing regional co-operation to tackle transboundary air pollution but also continue focusing on local sources of emissions. Both local and transboundary emission sources play a significant role and must be tackled at the same time. Knowledge of air pollution sources (domestic vs. transboundary) and of the impact of each upon health among citizens should be improved (Box 1).

Source: Trnka, D. (2020), "Policies, regulatory framework and enforcement for air quality management: The case of Korea", OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 158, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8f92651b-en.

Regulatory performance assessment

Regulations are introduced to deal with particular problems, but over time because of economic, social or technological change, the problems may change, or new instruments may become available which may better address them. However, old regulations or administrative formalities may remain in force (though perhaps not always enforced) and so most OECD countries have accumulated significant stocks of regulations and procedures, which may no longer be relevant. There is therefore a need to continuously review and look for ways of simplifying the stock of regulation.

The Cost-in, Cost-out, and the Regulatory Sunset Clause are the core instruments used to evaluate existing regulations. When introducing or reinforcing regulations, each central administrative agency is mandated to draft a plan of regulatory ex post evaluation as part of the RIA statement. The ex-post evaluation is intended to measure the actual impact of each regulation and check if the introduced regulation is fit for purpose.

Initially launched as a pilot project in 2014, the Korean “Cost-in, Cost-out” (CICO) system formally entered into full force in July 2016 by ordinance of the Prime Minister. CICO is a mechanism to restrict the increase of the costs of newly introduced or reinforced regulations by abolishing or relaxing regulations that carry equal or greater costs. 27 central administrative agencies have adopted CICO for regulations that generate direct costs for profit-seeking activities of any individual or business. Since CICO requires the responsible agency to conduct a cost-benefit analysis for outgoing regulations that are bound to offset the costs of newly introduced regulations, there is a built-in mechanism to reassess the validity, rationality, and appropriateness of the existing regulations. As another policy tool to conduct ex post evaluation, central administrative agencies are mandated to include a sunset clause in all regulations unless there are particular reasons not to comply with the sunset requirement. Sunset clauses can take the form of “review and sunset” or “outright sunset” with the explicitly stated timeframe that is usually three years and shall not exceed a maximum of five years. Such requirements induce central administrative agencies to conduct a retrospective or ex post evaluation of existing regulations, and actively revise, improve, or repeal those that do not serve the originally intended purpose. At present, there is no existing system (externally or internally) in Korea that publishes a calendar of the regulations to be reviewed.

The Korean government also makes some use of sunsetting as a mechanism to keep regulations up to date. The legal basis for sunsetting is provided in Article 8 of the BAAR which deals with the continuation of regulation. This article states that regulations that do not have “a clear reason to remain in effect” should not remain in force for longer than what is necessary to achieve their objective and in principle, this period should not exceed five years. Several variations of the sunset clause have been applied since its introduction in 1998. The overall aim of the sunset clause is to review periodically regulations in order to determine whether it will be retained or abolished. The Korean government has used sunsetting sparingly. Effective use of sunsetting requires that it be evaluated to ensure that it is achieving its objectives. Such an evaluation is undertaken by the RRC prior to extending the sunsetting period.

A number of surveys have been conducted to measure customer satisfaction in relation to regulatory reforms. Despite the government’s strong commitment to regulatory reform, there are concerns that the public may perceive that reforms have only a low level of improvement in their daily lives. To address this discrepancy between government efforts and public satisfaction, the RRC has been conducting annual customer satisfaction surveys on regulatory reform as part of the government performance evaluation of regulatory reform. The survey is conducted on the perception of the public, stakeholders, experts and government officials on regulatory reform efforts of the government, in terms of regulatory contents, process, performance, and impacts on daily lives.

Recent regulatory reform to facilitate new industries and technologies

As part of a prompt response to changes in regulatory environment, including the emergence and on-going development of the 4th Industrial Revolution, the Korean government has been developing and adapting innovative regulatory systems to facilitate the activities of new industries and technologies.

Since January 2019, the Korean government has been operating the Regulatory Sandbox program (Box 2) to allow for various experiments of potentially innovative technologies that were stalled under previous regulatory frameworks. Under safety conditions guaranteed through either special substantiation or interim authorisations, numerous innovative products and services have been experimented with and successfully market-launched to ultimately enhance the consumers’ well-being and convenience.

Since its initial announcement in 2017, the Korean Regulatory Sandbox programme was specially designed to cover four comprehensively categorised sectors, including information and communication technology (ICT) convergence, industrial convergence, innovative finance, and regional innovation. The programme was later expanded to the Smart City and Research and Development (R&D) Innovation Cluster sectors to guarantee enhanced social safety and to further foster development of innovative technologies in a wider range of sectors. While each ministry, or authority, leads the related regulatory sandbox (for instance, the Financial Services Commission oversees the Innovate Finance sector and the Ministry of Science and ICT is in charge of the ICT Convergence), the Office of Government Policy Coordination oversees the cooperation among ministries and manages the overall mechanism.

Regulatory sandboxes allows firms to pre-launch innovative products and services in the market under certain conditions, namely, limited period, location, and scale. Participating firms are exempted from regulations which they would have otherwise abided by if not for the regulatory sandbox. Based on the data collected during the process, relevant regulations are amended and rationally improved. On top of the Special Substantiation, Interim Authorization, and Active Administration, safeguards for consumers work conjunctly to serve the purpose of the regulatory sandbox. As of August 2021, 105 cases of regulatory sandbox were approved in 2021, 209 in 2020, and 195 in 2019. Sector-wise, 153 cases related to Innovate Finance, 144 to Industrial Convergence, 111 to ICT Convergence, 71 to Regional Innovation, and 30 to Smart City. In terms of the support mechanism, 411 cases benefited from Special Substantiation, 65 from Interim Authorization, and 33 from Active Administration.

Source: Regulatory Reform Committee (2021), Regulatory Sandbox website, https://www.better.go.kr/sandbox/index.jsp (assessed 17 August 2021).

The Korean government made a fundamental regulatory paradigm shift to properly respond to the rapidly changing regulatory environment. Under the previous “positive” regulatory system, new and emerging innovative products and services had to comply with regulations that were not always compatible with the emerging technology. A transition into the so-called “allow first, regulate later” system was suggested in order to promptly bring emerging technologies into the market and revise relevant laws ex post, when necessary. Following the official announcement of its transition to the Comprehensive Negative Regulatory System in September 2017, the Korean government has actively conducted review and adjustment of existing regulations, initially focusing on the central government ordinances. The campaign has quickly expanded to amendment of other regulations at other levels, including the municipal.

The Preemptive Regulatory Innovation Roadmap is another instrument set up by the Korean government to proactively search for and remove existing regulatory hurdles that may hinder innovation, by foreseeing upcoming developments in emerging technologies. Whereas the previous regulatory reform programs had taken a bottom-up approach, in which the government rather passively reviewed the reform agenda proposed by private sector, the pre-emptive regulatory innovation system will undertake a top-down approach requiring ministries to proactively discover and handle potentially regulatory issues that may arise in emerging markets. The Preemptive Regulatory Innovation Roadmap has been prepared in six areas, including autonomous vehicles, drones, hydrogen and electric vehicles, virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR), robots, and artificial intelligence (AI).

Competition policy

The Korea Fair Trade Commission (hereinafter “KFTC”) joined the OECD Competition Policy Committee as an observer in 1993 and participated in the Competition Week meeting for the first time in December of the same year. Since then, the KFTC has participated in the meetings every year to share Korea’s experience with competition policies and law enforcement and also to share and discuss views on competition issues. The KFTC has contributed to establishing and spreading best practices in the field of competition policy through the OECD Competition Committee meetings and made efforts to enact and revise OECD recommendations so that not only member countries but also non-member countries can refer to it when enforcing competition laws.

Since joining the OECD, Korea has actively shared its experience and opinions on laws, systems and cases related to competition with other member countries. As a result, Korea has not only advanced its competition law and system, but also taken the lead in discussing international competition issues and promoting its experience of implementing competition laws to developing countries.

Since 1999, the KFTC has dispatched staff to the OECD Secretariat to directly contribute to the activities of the OECD Competition Division. Since 2001, several high-ranking KFTC officials have been elected to the Bureau of the OECD Competition Committee, and they actively participated in setting and operating the agendas of the Competition Committee and working parties.

Through such active participation, the KFTC has contributed to the enactment and revision of more than 10 recommendations in the OECD Competition Committee. The results of these discussions have also been reflected in domestic legislation and policies. Specifically, Korea accepted OECD recommendations and enacted the Cartel Reorganization Act in 1999 to regulate hard-core cartels. Also, Korea raised the upper limit of penalty surcharge from 5% to 10% of related sales (2004)1 and referred to the OECD for the introduction of essential facilities doctrine in the Enforcement Decree of Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act (hereinafter “MRTFA”). And in line with the OECD Guidelines for Corporate Governance (1999), standards for corporate governance and the holding company system were introduced in 1999.

In addition, the KFTC has prepared specific standards to effectively prevent government regulations that limit competition unnecessarily – based on the OECD’s Competition Assessment Toolkit in 2007, the KFTC prepared the “Competition Assessment Manual”.

Consultation with the KFTC is required when enacting or revising government legislation and administrative rules that restrict competition. As a result, the number of KFTC consultations on government regulations continued to increase from 430 in 2004 to 1,097 in 2009, 1,912 in 2014 and 2,649 in 2020. In addition, the KFTC has been making steady efforts to improve the anti-competitive regulations existing in local government laws since 2007. Moreover, the Office for Government Policy Coordination revised the "Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement Guidelines" in 2009 to enable the KFTC to perform competition assessment of new and strengthened regulations of ministries with its experience and expertise. As a result, competition assessment has become one of the essential legislative procedures.

Furthermore, the OECD has a dedicated Regional Centre on Competition (RCCs) (OECD-Korea Policy Centre, Competition Programme) which is a joint venture between the Korean government (via KFTC) and the OECD. The Competition Programme of the OECD-Korea Policy Centre has operated since 2004. Its objective is to improve enforcement capabilities of competition agencies in the Asia-Pacific Region. It also facilitates information sharing and networking between agencies in the region. It does this through workshops and seminars and also undertakes research. The KFTC participates actively as do many competition authorities from the OECD, sending experts speakers. To date more than 2500 participants from 26 economies (competition officials, regulators and members of the judiciary) from Asia-Pacific have benefited from the programme.

The activity of the OECD-KPC Competition Programme has been critical to the development of competition law and policies in the region in line with international best practices, It provides an important platform that supports the improvement of the business environment thought out the Asia-Pacific region.

Online platforms have created and reshaped markets across various sectors. The power of these platforms in some markets stem partially from the strong network effects that they generate and their significant economies of scale and scope, leading to tipping and to winner-takes-most dynamics and to high concentration levels. Online platforms also have the ability to collect and exploit data which may act as a barrier to entry in some markets. These characteristics have attracted the attention of competition enforcers and policymakers around the world.

Examples are the European Union with the Digital Markets Act (DMA) proposal and the advice of the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA Advice) on a new pro-competitive regime for digital markets. These proposals of ex-ante regulatory frameworks are based on competition principles and aim to encourage competition, limit the exploitation of market power and open up markets for new entry. They would apply to gatekeepers in the DMA or firms determined to have strategic market status (SMS) under the CMA Advice.

Considering that the increasing reliance on online platform operators has resulted in their superior bargaining position and has raised anti-competitive concerns, the Korea Fair Trade Commission (KFTC) proposed the enactment of the “Act on Fair Intermediate Transactions on Online Platform” (Online Platform Bill) in September 2021. The Bill targets platform operators or firms that intermediate transactions between online stores and their consumers in Korea and generate commission fees or have intermediate transaction amounts in excess of KRW 10 billion and KRW 100 billion, respectively, in a year.

The Online Platform Bill seeks to improve transparency and fairness in the transactions between platforms operators and online stores by imposing certain obligations on the former to: (1) include mandatory provisions in the contract between the platform operator and online store, including statements on whether (a) the online store can access information generated by its consumers, and the means and conditions for accessing such information; (b) the platform will treat the products of the online store differently from other products; (c) the platform’s intermediary services is conditioned on the online store’s use of other services or products; and (2) requiring platform operators to notify online stores 15 days prior to any change in the terms of the contract, or any limitation, suspension, or cancellation of the platform’s services.

The Bill also specifies the practices of platform operators that may be considered as an abuse of superior bargaining position under Article 23(1)(4) of the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act (MRFTA). These include forcing online stores to purchase products or services, setting or modifying trading conditions to the disadvantage of online stores, and interfering with the business activities of online stores.

Differently from the DMA or the CMA Advice, the obligations under the Online Platform Bill apply even to firms without a substantial or entrenched market power, or those which do not possess a superior bargaining position under the (MRFTA).

The Online Platform Bill will require approval by the Korean National Assembly.

Source: Korea Fair Trade Commission, “Pre-announcement of legislation of Act on Fair Intermediate Transactions on Online Platforms”

Conclusion

Korea has made remarkable progress in establishing the institutions, processes and tools to support good regulatory practices since it joined the OECD in 1996. This is borne out by OECD data and results on the ground.

There is high-level commitment to leadership and oversight of regulatory reform through the ministerial meetings on regulatory reform focus on reducing regulatory burdens and creating a more business-friendly environment. The culture of the administration needs to maintain regulatory reform as a priority for the incoming administrations by ensuring the continuity of policies and tools that have worked.

RIA is a cornerstone of good regulatory practice in Korea. First introduced in 1998 and brought into the digital realm in 2015, RIA statements are drafted and processed through an online platform, which automatically compares regulatory costs and benefits. Research institutions with some degree of autonomy from government also provide independent analysis on specific issues.

The National Assembly should consider the creation of a permanent legislative regulatory quality mechanism to scrutinise its own legislative actions as well as asking the executive branch to submit all relevant materials such as RIA statements and CICO analyses to the National Assembly so that the expected impacts of primary legislation are taken into consideration when reviewing or drafting bill.

Initiatives to increase the transparency of and public access to the regulatory process include the creation of government portals such as i-Ombudsman and the online Regulatory Reform Sinmungo are welcomed. The government needs to ensure that central administrative agencies much more actively engage relevant stakeholders and local administration early in the process of rule-making and support capacity within the public administration to engage with stakeholders.

Korea made impressive reforms to review and reduce its stock of regulations after joining the OECD and in the immediate wake of the 1997 financial crisis, reducing its stock of regulations by 50%. More importantly, these efforts were likely to have facilitated a shift in thinking among Korean government officials away from command and control regulation and contributed to the momentum for regulatory reform that took hold over the next two decades. That said, the administration need to make greater efforts to introduce ex post evaluation for existing regulations in a strategic manner, and discuss and publish planned evaluations. Likewise, it needs to integrate quality control systems into regulatory reduction initiatives using clear and systematic criteria to guarantee that regulations are meeting the intended objectives in the perception of both the regulated entities and those who implement and enforce regulations.

As final thought, emerging and digital technologies are raising profound regulatory challenges for governments. A key aspect in this regard is the regulation of online platform. Policy makers and regulators alike need maintain a balance between fostering innovation, protecting consumers, and addressing the potential unintended consequences of disruption. As government rebuild afresh from the pandemic, Korea should ensure that innovation is not held back by regulations and regulatory practices designed for the past. Korea should strive to ensure its regulations keep up with the global scale and high speed of innovation to guarantee their populations worldwide benefit from innovation without paying a high price on their human, social, or economic rights. In the face of these challenges, Korea needs to consider a more agile and internationally coordinated approach to the regulatory governance of innovation; one that supports renewed economic growth, inclusive development and resilience to future shocks.

Note

The upper limit of penalty surcharge will be raised again to 20% of related sales according to the MRFTA, which was revised in December 2020 and will be enacted in 2021.