Germany joined the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) in 1960 and was last peer reviewed in 2015. This report assesses the progress made since then, highlights recent successes and challenges, and provides key recommendations for the future. Germany has partially implemented 79% of the recommendations made in 2015 and fully implemented 21%. This review contains the DAC’s main findings and recommendations and the Secretariat’s analytical report. It was prepared with reviewers from Belgium and the Netherlands, with Romania as an observer, for the DAC peer review meeting for Germany at the OECD on 19 May 2021. In conducting the review, the team consulted key institutions and partners in Germany during October and November 2020, in Rwanda in December 2020, and in Tunisia in January 2021.

Global efforts for sustainable development. Germany is strongly committed to sustainable development and climate change and aims to achieve fair and sustainable globalisation. Greater use of soft power would increase its global influence. Germany promotes global public goods, addresses global challenges, and contributes to global responsibility sharing, e.g. regarding health and safe, orderly and regular migration. The Sustainable Development Strategy has a strong vision but could be more ambitious. Germany has mechanisms supporting coherence between domestic policies and sustainable development objectives and is making progress in some shared policy areas, but could do more to limit spillover effects on developing countries. Close collaboration is needed among the autonomous federal ministries and federal states in Germany’s decentralised government system. Development co-operation and helping people in poor countries are important to German citizens. Further work is needed to translate positive attitudes into more public engagement and behaviour change.

Policy vision and framework. Development Policy 2030, issued in 2018, is centred on the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement on climate change. While development co-operation sits firmly within Germany’s political and strategic priorities backed by strong leadership and resources, there is no overall vision binding German development actors beyond the dedicated Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). The BMZ 2030 strategy operationalises Development Policy 2030, allowing for a long-term focus on global public goods as well as shorter-term political initiatives. Germany recently refocused its development co-operation towards Africa, reduced the number of its partner countries from 85 to 60 and concentrated thematic priorities in five core areas. This could offer a modern narrative emphasising Germany’s comparative advantage in development co-operation. Germany should continue to invest in a number of cross-cutting quality criteria including gender equality and reducing poverty and inequality. Its multilateral strategy strives to reaffirm the multilateral order and anchor political priorities including action for climate change. Germany could engage more with the broad range of stakeholders involved in its development co-operation.

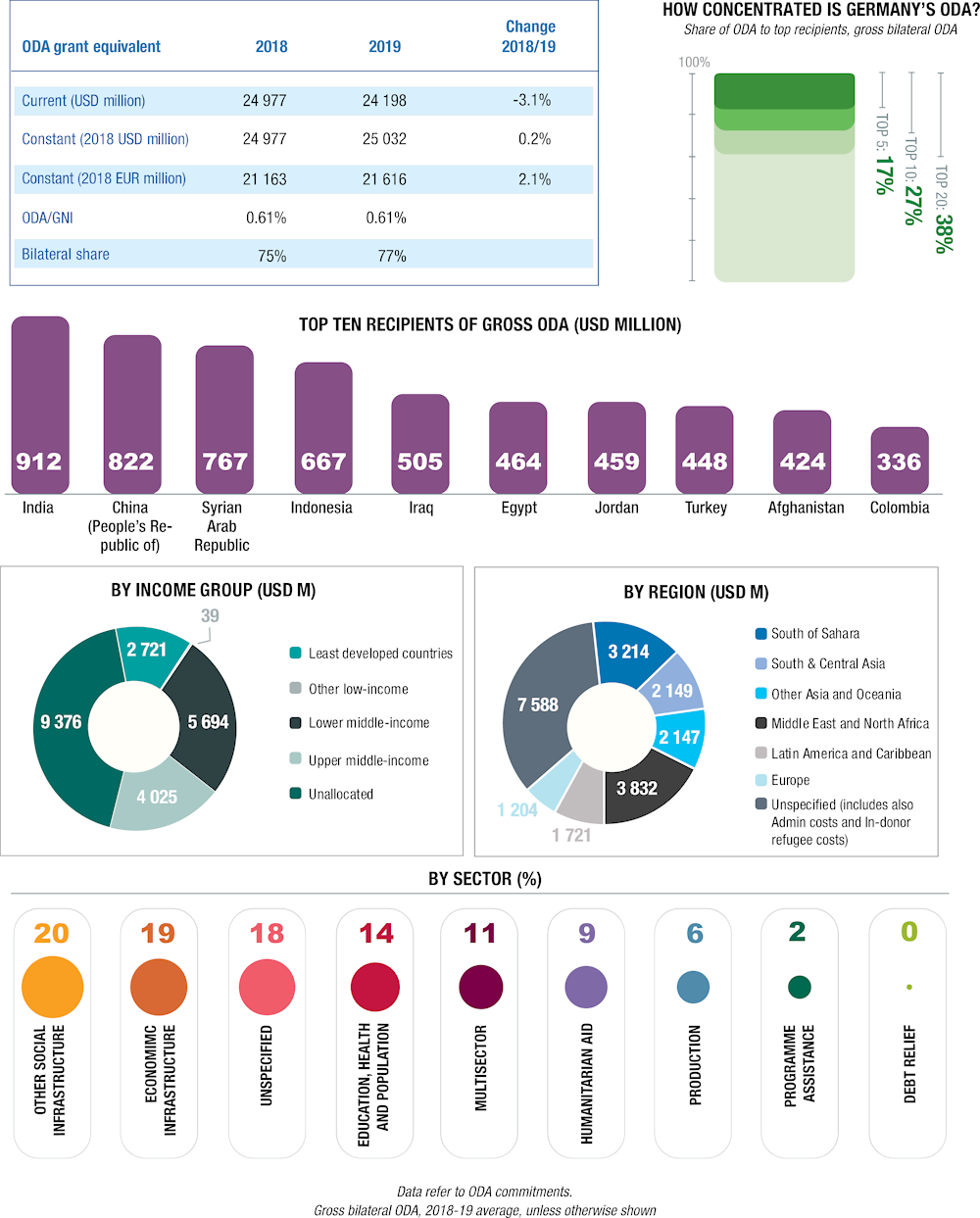

Financing for development. In 2020, Germany provided official development assistance (ODA) in the amount of USD 28.4 billion (according to preliminary data), representing 0.73% of gross national income (GNI), one of only six DAC countries to meet or exceed the ODA as a percentage of GNI target of 0.7%. The second largest DAC provider country since 2016, Germany has yet to provide 0.15% of GNI as ODA to least developed countries. Loans represent 23% of gross bilateral ODA, and almost all loans are disbursed to middle-income countries. Technical co-operation, implemented almost exclusively through Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, constitutes 16% of bilateral grants. The Middle East and North Africa as a region has received the biggest increase in ODA since 2010, although Germany’s ODA is now mostly concentrated in Africa. Budget support provided as policy-based loans has also increased. A strong multilateralist, Germany also promotes joint action for climate change and the root causes of displacement. It supports financing beyond ODA through KfW Development Bank (KfW) and its subsidiary, German Investment and Development Company (DEG), and has been instrumental in establishing an architecture to support partner countries to mobilise domestic resources.

Structure and systems. While having a dedicated ministry raises the profile and resources for development co-operation, ensuring a whole-of-government approach is challenging in Germany’s decentralised system. Ministerial autonomy and the non-hierarchical relationship between autonomous ministries lead to a practice of non-interference requiring co-operation and co-ordination. The respective roles and division of labour between BMZ and the four implementing organisations are clear, complementary and understood in partner countries. BMZ is aiming at reducing bureaucracy and making political steering more effective through the joint procedural reform and integrated planning and allocation system. Germany’s comprehensive and solid risk management system assesses, monitors and mitigates risks. Highly skilled staff manage and deliver German development co-operation, although it remains highly centralised. Increasing the number and capacity of BMZ staff seconded to Embassies, enhancing their contribution to decisions and enabling them to engage flexibly in development co-operation at country level would enable Germany to be more effective and efficient. National staff ensure a sound understanding of local contexts and constant dialogue. Greater use of international languages for non-official documents would strengthen the contribution of national staff and facilitate their skills improvement.

Delivery and partnerships. Germany has strong partnerships including with multilateral institutions, state and municipal actors, civil society organisations (CSOs), research and evaluation institutes, and an interested private sector. It could make better use of this diverse range of partners; step up funding to CSOs, including Southern CSOs; and reduce bureaucratic hurdles. Dedicated mechanisms and instruments enhance predictability and flexibility for private sector involvement, but funding periods and bureaucracy remain challenging. Germany is a strong supporter of multilateralism and European Union joint programming and a champion of triangular co-operation. It could do more to encourage multi‑stakeholder partnerships. While Germany champions development effectiveness, BMZ will need to safeguard partner country ownership when implementing its BMZ 2030 reform, which offers an opportunity to rethink the form and content of its country strategies. Support to partner countries is predictable and forward planning is strong. Germany has a broad range of instruments at its disposal to respond flexibly to partners’ demands, and its reform financing is contingent upon showing results to which they agree.

Results, evaluation and learning. Germany’s development co-operation aligns with partner country priorities, but it does not articulate overall objectives in ways that can be measured and assessed. While project outcomes are linked to portfolio impacts, work is required to improve results-based management and embed a results culture within German development co-operation. An enhanced integrated data management system and broader set of indicators would help. Results information is used for accountability and communication but not for strategic direction and management. Germany has strong and respected evaluation capability and contributes to evaluation internationally. The German Institute for Development Evaluation focuses on strategic evaluations and GIZ and KfW on evaluating projects and portfolios. Germany might consider how best to allocate resources for evaluation across the German system. Evaluation functions are independent. GIZ and KfW could improve their approach by building institutional evaluation capacity including through participatory approaches in partner countries. Networks exist for knowledge sharing and learning across the German system but knowledge management is challenging. Results information, evaluation findings and lessons learned need to be more systematically disseminated.

Fragility, crises and humanitarian aid. Germany has a clear vision and set of policies to support peace efforts. Yet, its increased ODA is not primarily invested in fragile contexts. Germany champions policy discussions to increase coherence in crisis contexts. BMZ, GIZ and KfW have strengthened the modalities of their engagement in high-risk contexts and the Federal Foreign Office’s humanitarian assistance is needs-based and grounded in humanitarian principles. BMZ and the Federal Foreign Office have significantly strengthened their co-ordination, notably on joint analysis. Refining further the intersection between humanitarian assistance and conflict-sensitive development co-operation would enhance complementarity. In addition, clarifying that a nexus approach to programming is relevant beyond the ten countries in BMZ’s partner country list could strengthen Germany‘s programming in all fragile contexts. Germany has firmed up partnerships with multilateral actors, but stronger support to grassroots civil society could also ensure more targeted impact and granularity of context analysis in peace and crisis prevention settings.