“So, how much do you make?”

This is not a question that comes up often between colleagues over lunch, or even at after-work happy hour.

Discussing pay is implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) forbidden in many places. This has historically made it difficult for workers to know whether they are being fairly compensated for doing their job.

Pay transparency, therefore, has a simple allure: it lets workers know whether their pay measures up to that of their colleagues, and puts a concrete number on the pay gap between women and men. This gives workers and their representatives a tangible piece of evidence to advocate for fair pay and against discrimination.The text of the article can be entered here. Use several text components in order to separate paragraphs more clearly. If you need to add images, charts or to embed external contents, use the corresponding components.

This helps to explain the success of the new EU Pay Transparency Directive, which gives countries three years to comply with a range of measures including salary transparency in job advertisements, a prohibition on asking job candidates their salary history, and gender pay gap reporting rules for firms.

Even as governments and businesses debate the details of implementation, the basic concept is hard to oppose. On average across 27 countries, two-thirds of respondents to the OECD Risks that Matter Survey support increasing pay transparency to reduce wage gaps, foster diversity and fight discrimination.

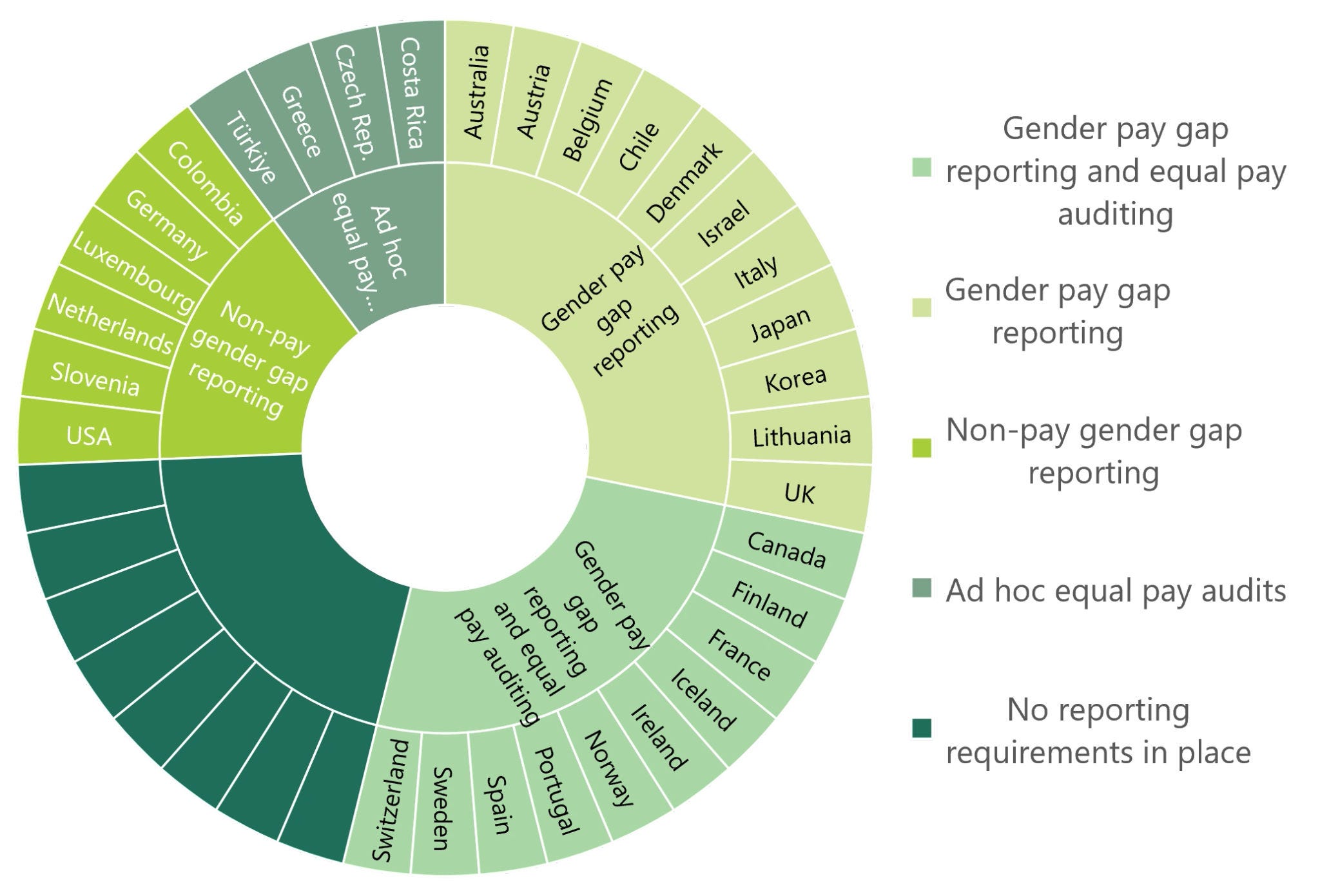

Today, 21 out of 38 OECD national governments (55%) require private sector employers to analyse their pay data and report gender-disaggregated pay information to stakeholders like workers, their representatives, the government and the public. Considerable progress has been made in implementing national-level pay transparency action rules outside the EU in recent years, including in Australia, Canada, Japan, Korea and the United Kingdom (as well as sub-nationally in countries like the United States). Overall, though, the bulk of pay transparency commitments have taken place in Europe. Progress will surely speed up in the next three years thanks to the new Directive.

55% of OECD governments now have national-level gender pay gap reporting requirements for private sector employers

The success of current and future pay transparency regimes critically depends on their design. Our recent study, Reporting Gender Pay Gaps in OECD Countries: Guidance for Pay Transparency Implementation, Monitoring and Reform, identifies promising practices and likely pitfalls from the diverse experiences of 21 national pay gap reporting systems.

Governments can simplify gender pay gap reporting and ease the employers’ burden by providing free and accessible wage gap calculating software.

First, digital investments in pay transparency pay off. Governments can simplify gender pay gap reporting and ease the employers’ burden by providing free and accessible wage gap calculating software, as is the case in France, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and several other countries. Quantitative research also suggests that these are the countries in which pay reporting has helped to narrow gender pay gaps. Another particularly novel approach is the use of pre-existing data enabling the government to calculate gender-disaggregated wage statistics on behalf of firms. Lithuania, for example, calculates gender pay gaps for employers using social security contribution data. Denmark calculates pay gaps using firm-specific data in the Structure of Earnings Survey and reports these gaps back to firms.

Second, when reviewing countries’ pay gap reporting rules, we were discouraged to see that very few governments have systematic compliance mechanisms in place to ensure that firms report. Sanctions against non-compliant firms are also generally weak. As countries explore regulatory strategies, the role of public “naming and shaming” – or perhaps “naming and praising” – should not be underestimated. Public disclosure of firms’ pay gaps has been cited as critical to ensuring high compliance with reporting rules in the United Kingdom.

Third, simply reporting a gender pay gap will do very little if no practical steps are taken to close it. Follow-up action matters. Equal pay auditing systems assess gender pay gaps in more detail, often look at human resources practices related to gender equality and recommend targeted action to try to address the inequalities found. The EU’s call for “joint pay assessments” should go a long way in ensuring that governments, firms, workers and their representatives have a shared stake in closing gaps that are found in gender pay gap reporting.

Too often the work of identifying, raising and rectifying pay inequality still rests on individual workers and their representatives.

Fourth, more evaluations are needed to understand what works. Only a handful of national programmes have been analysed quantitatively to assess the effects of the gender wage gap, even though pay gap reporting rules are ripe for rigorous, quasi-experimental evaluation. Regular evaluations of programme functioning, including compliance and awareness of rules, are also lacking across countries.

Finally – and importantly – governments must not forget the big (gender equality) picture. Pay transparency can only go so far in promoting gender equality. Too often the work of identifying, raising and rectifying pay inequality still rests on individual workers and their representatives. This implies enormous costs in time and energy. Pay transparency also often comes too late to solve the gender wage gap, as it cannot correct choices and constraints accumulated throughout a person’s life. Governments must embed gender pay gap reporting in broader policy efforts to end gender inequalities in workplaces, in society and at home.