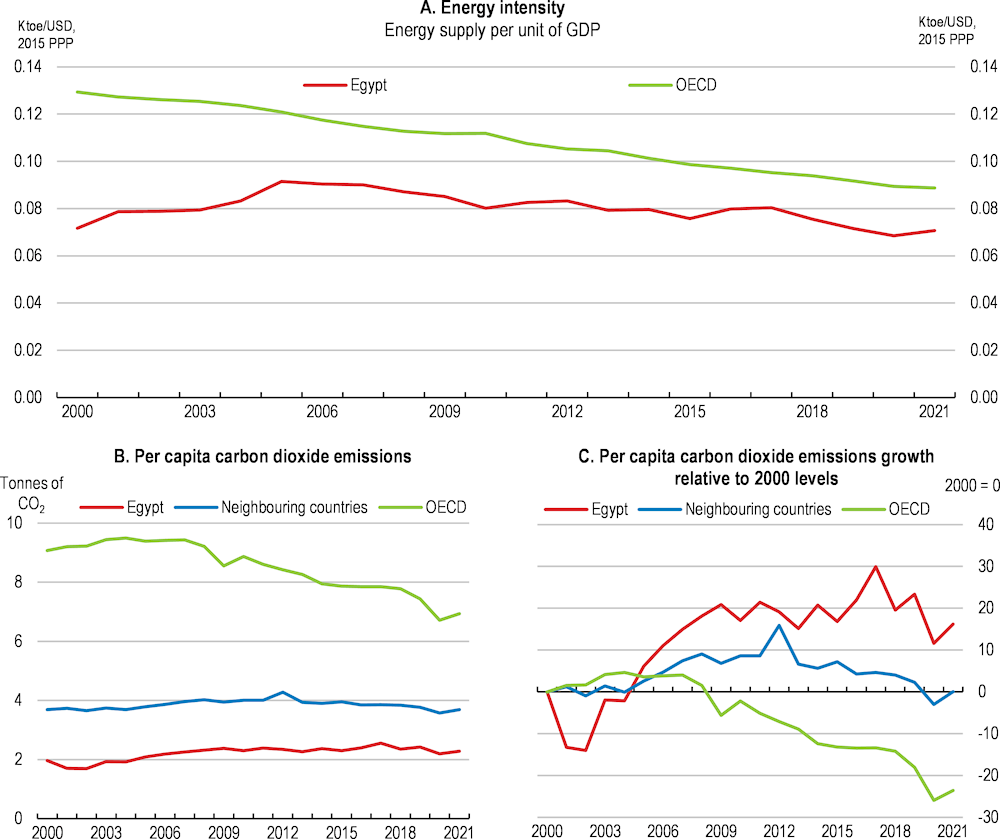

Growth has held up better in Egypt until recently than in neighbouring countries in the face of several major external shocks, and the government has started to implement structural reforms to address macroeconomic imbalances and improve longer-term growth prospects. Following the ongoing slowdown, growth is projected to pick up, provided inflation subsides, financing conditions normalise, and uncertainty dissipates, which requires prudent monetary policy and steadfast commitment to fiscal consolidation. Stepping up reform efforts would help improve investor confidence, alleviate external pressures and keep debt service costs in check. It would also bolster the economy’s resilience against future shocks. Egypt is particularly exposed to the consequences of climate change, highlighting the importance of green policies. Energy subsidies should be reduced and social benefits target the most vulnerable people. Public investment should focus on green infrastructure that promotes private sector investment.

OECD Economic Surveys: Egypt 2024

2. Key policy insights

Abstract

2.1. The Egyptian economy faces macroeconomic challenges

Growth has held up better in Egypt until recently than in neighbouring countries in the face of a series of major exogenous shocks, and reforms efforts have been stepped up in several areas. However, a large current account deficit and high public debt made Egypt particularly vulnerable to capital outflows, which indeed occurred in early 2022, in a context of rising commodity prices and tightening financial conditions in international financial markets. As balance of payment prospects worsened and the country faced acute foreign currency shortages, a USD 3 billion Extended Fund Facility Arrangement with the IMF was put in place in late 2022.

Egypt has expanded the scope of macroeconomic policy reforms under the IMF programme. Programme conditionality includes making the exchange rate flexible, conducting prudent monetary policy, improving the budget balance and implementing structural reforms (IMF, 2023a). Such reforms would reduce public debt and macroeconomic imbalances, alleviating financial stability risks and making the economy more resilient to future exogenous shocks. Reducing the fiscal gap would strengthen market confidence, which would reduce debt servicing costs, and create space to finance the much-needed expenditures to ensure people’s well-being, such as health and social protection.

2.1.1. Imbalances have built up over the past decade

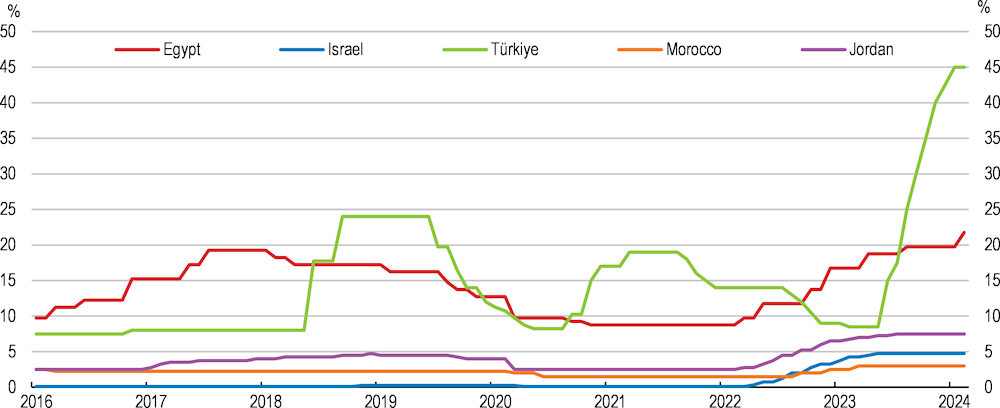

Export growth slowed down over the decade to FY 2021/22, reducing exports’ share in GDP (Figure 2.1). The share of total investment in GDP declined over the same period, to only 12.9% of GDP by FY 2022/23, which is low by international standards. This reflects a drop in the share of private investment in GDP to 4.3% by FY 2022/23. Public investment in contrast reached 8.6% of GDP, higher than in any OECD country. Consumption has outpaced GDP over the past decade, propelled by various government supports. As a result, public expenditure has expanded faster than GDP, aggravating the fiscal deficit.

Figure 2.1. Public investment has increased

The share of expenditure components in current-price GDP

Note: Data refer to fiscal years from July to June of the following year.

Source: Ministry of Planning and Economic Development.

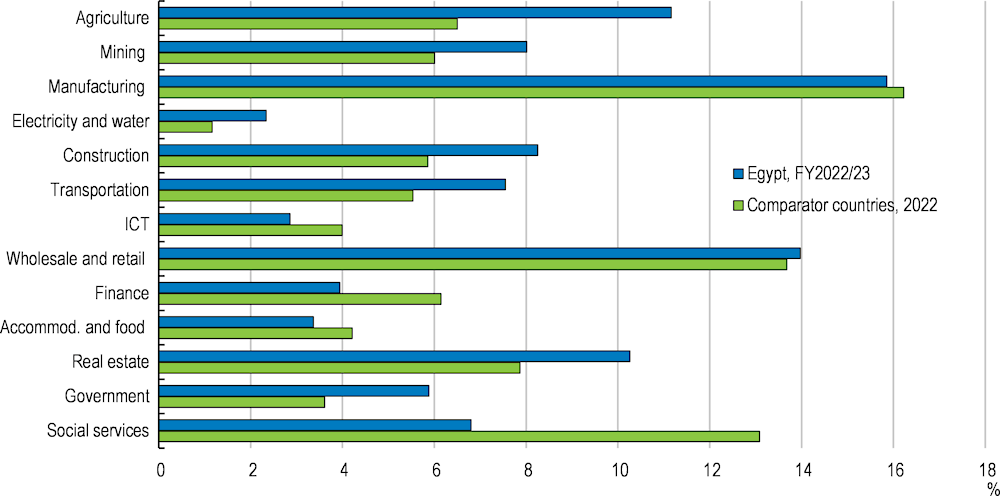

The industrial structure has also changed over the past decade but the development of high value-added industries remains limited (Figure 2.2). Manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, and agriculture remain the largest sectors. The share of the manufacturing sector in Egypt is slightly lower than in comparator countries on average. The share of construction has almost doubled over the past decade, consistent with the expansion of large-scale public investment projects. The services sector is relatively less developed, which is particularly the case for finance as well as information and communication technologies. Although the government sector stricto sensu is not that large, numerous public enterprises operate across industries and account for approximately one-third of total value added (Chapter 3).

Figure 2.2. The development of high value-added industries remains limited

Share of industries, as % of GDP

Note: Comparator countries refer to Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Greece, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, South Africa, Thailand, Tunisia, Türkiye and Viet Nam as defined in Box 1.3 in Chapter 1.

Source: Ministry of Planning and Economic Development.

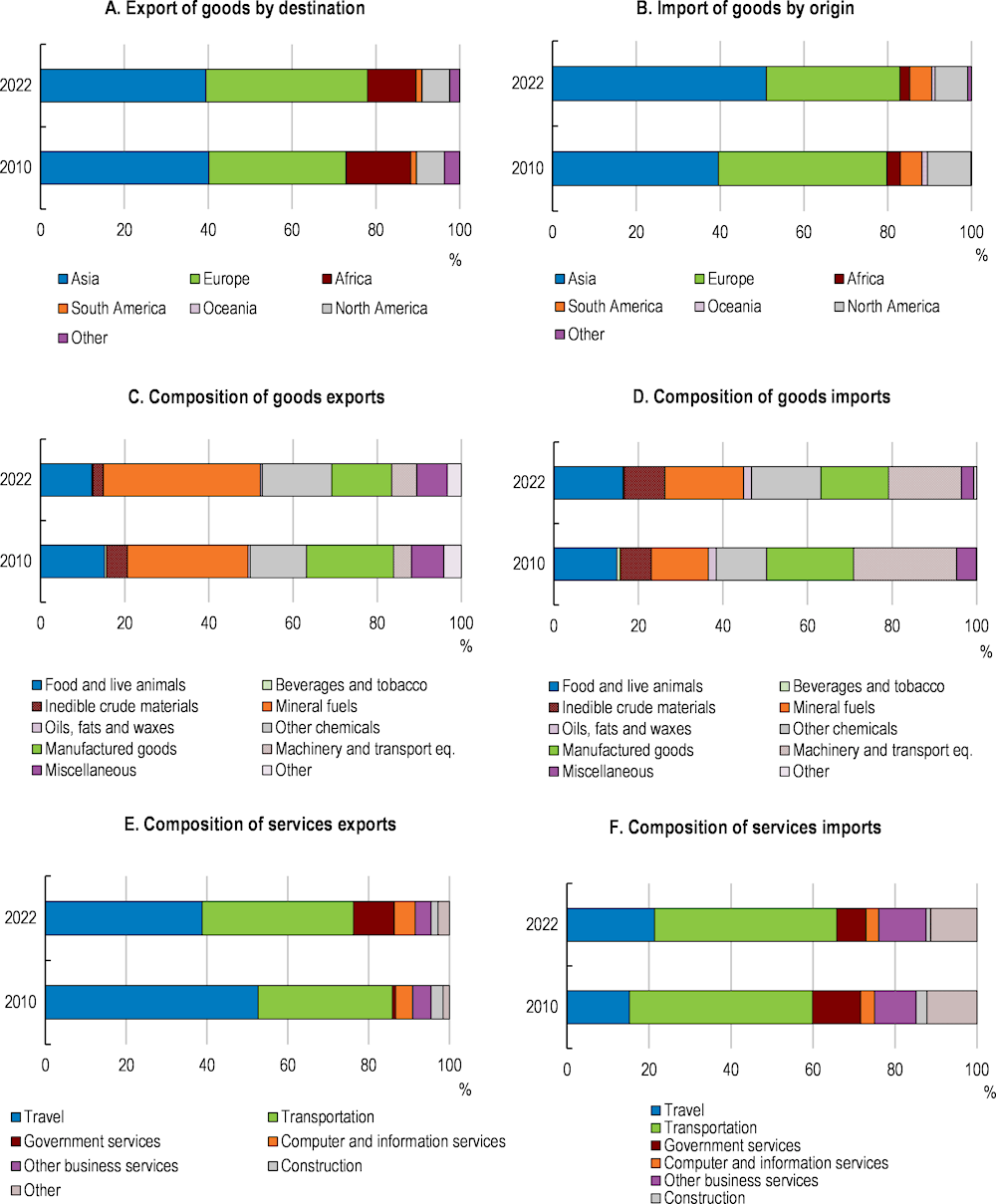

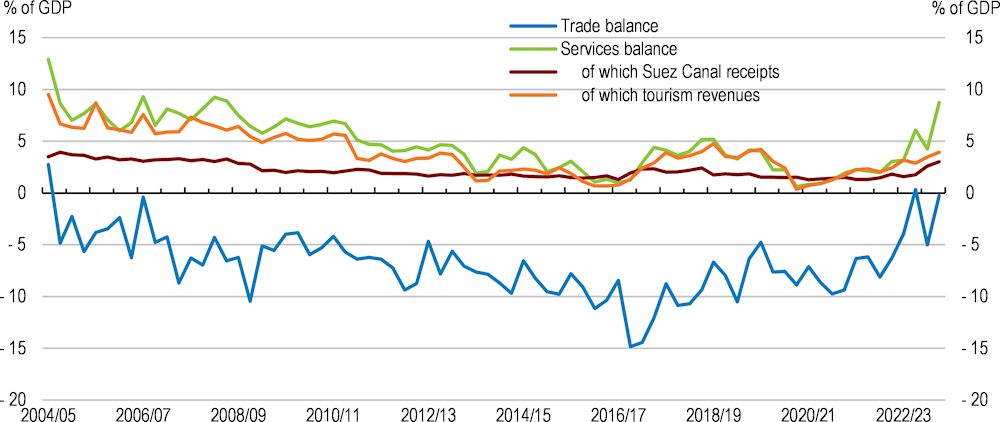

Until recently, Egypt has recorded a sizeable trade deficit (Figure 2.3), as it has long been spending more than its production capacity, relying heavily on imported products, including basic necessities such as food and energy. In terms of imports, food, mineral fuels, as well as machinery and transport account for a large share (Figure 2.4). Among exports, mineral fuels and tourism stand out, reflecting Egypt’s geographical and historical endowments. The improvement in the trade balance in FY 2022/23 is mostly due to a decline in non-petroleum imports (see below).

Figure 2.3. The trade deficit has been shrinking

Note: Data refer to fiscal years (from July to June of the following year).

Source: Central Bank of Egypt; Ministry of Planning and Economic Development and CEIC.

Despite the large size of its agricultural sector, Egypt imports far more food products than it exports, making it vulnerable to terms-of-trade shocks. Among imported food items, wheat is the most important, accounting for 16% of total food imports (Box 2.1). Egypt is the world’s largest importer of wheat, with Russia and Ukraine accounting for 85% of wheat imported by Egypt prior to the war (OECD, 2022a). Due to the spike in global food prices, the food trade balance deteriorated by USD 2.0 billion in 2022, with the value of wheat imports rising by USD 1.3 billion. Population growth will push up food demand even as the agricultural sector faces intensifying pressures from climate change (Abdalla et al., 2022).

Egypt is both a large importer and a large exporter of energy (Box 2.2). It imports oil, essentially from countries in the Middle East, such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. At the same time, it exports natural gas, mainly to Europe. Natural gas accounts for the bulk of electricity generation in the country. Energy production is affected by energy prices in international markets, as for instance Egypt increased exports of natural gas in 2022 when its price soared, while increasing the share of heavy fuel oil in electricity production. In FY2021/22, petroleum exports increased by 109% while petroleum imports increased by 57%, resulting in an improvement of the petroleum trade balance by USD 4.4 billion (0.9% of FY 2021/22 GDP). This more than offset the deterioration in the food trade balance. In FY2022/23, the petroleum trade surplus was substantially reduced, essentially due to a decline in petroleum exports.

Figure 2.4. The reliance on exports of raw materials is high

Box 2.1. Food production, trade and subsidies

Egypt’s agricultural sector is large (Figure 2.2). Its major products include rice, maize, wheat, cotton and sugarcane. Egypt is the world’s largest importer of wheat and imports large quantities of other key commodities, including major grains and cooking oil. Consumption of wheat increased by 64% in volume terms between 2000 and 2021 (Table 2.1). Production was up by 50% and imports by 98% over the same period (Table 2.1), thus the self-sufficiency ratio declined significantly. Egypt has imposed temporary export bans on several food products such as wheat, maize, lentils, flour, sugar, onions and cooking oils.

Table 2.1. Egypt relies heavily on wheat imports

|

|

1990 |

1995 |

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2015 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Tonnes, thousands |

||||||||

|

Production |

4268 |

5722 |

6564 |

8141 |

7177 |

9608 |

9102 |

9842 |

|

|

Exports |

0 |

0 |

13 |

0 |

62 |

253 |

466 |

20 |

|

|

Imports |

5864 |

6322 |

5701 |

7600 |

10140 |

12068 |

12146 |

11300 |

|

|

Consumption |

10132 |

11794 |

12902 |

14841 |

17455 |

20397 |

21482 |

21121 |

|

Source: OECD/FAO Agricultural Outlook 2023 database; Ministry of Agriculture and Land Reclamation.

The government actively intervenes in the agricultural sector, notably through procurement policies. Procurement prices for wheat are below global prices: the latter are projected to be USD 340 per tonne in FY 2023/24, but the procurement price is set at EGP 10 000 per tonne, or around USD 325 at the end-2023 market exchange rate.

The country faces acute food security challenges. 27% of the population were classified by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) as moderately or severely food insecure and 5.1% were undernourished in 2019-21. These pressures are exacerbated by a rapidly growing population and strong vulnerability to climate change. Sustainable management of irrigation and water resources is also an important concern, as agriculture accounts for over 80% of total water use, and less than 2% of agricultural production is rain-fed.

The government aims to develop the agricultural sector further, as stated in the National Structural Reform Programme. To do so, it collaborates with international bodies such as the FAO. The 2018-22 FAO Country Programming Framework for Egypt aimed to improve agricultural productivity, raise food security in strategic food commodities, and ensure sustainable use of natural agricultural resources.

Until recently, food subsidies for households consisted of two main systems. The first one was the bread subsidy, covering 71 million individuals and five loaves of round bread daily per person. The second one was the “ration card”, covering 64.4 million individuals (World Bank, 2022a), which provides a monthly voucher for subsidised food items, including rice, macaroni, tea, sugar, and cooking oil essentially. These subsidies were conditioned on eligibility criteria, such as household income (no more than EGP 1500 per month), employment status (e.g. seasonal workers), and household structure (e.g. widowed or divorced women, and pensioners). Recently the two systems were integrated into the new “ration card”, which still reaches almost the same number of households as in the previous systems. In the new system, only two children per household can be covered.

Food-producing businesses receive indirect support, in particular in the form of exceptions for the fuel price indexation mechanism (see Box 2.2).

Box 2.2. Energy production, trade and subsidies

Egypt has become a net importer of oil since the turn of the millennium. Production of crude oil and natural gas liquids has declined over the past decades (Table 2.2) and accounted for 0.7% of world production as of 2021. In contrast, Egypt has considerably increased natural gas production since the mid-2000s: by 2022, it represented 1.6% of world production.

Table 2.2. Egypt’s energy production mix has changed

A. Crude oil and natural gas liquids production

|

|

1990 |

1995 |

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2015 |

2020 |

2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Unit: kilotonnes |

||||||||

|

Production |

45499 |

46588 |

35539 |

32243 |

34676 |

34561 |

30789 |

29398 |

|

Exports |

19615 |

17133 |

9891 |

2055 |

9438 |

12399 |

0 |

0 |

|

Imports |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2504 |

3694 |

3238 |

2155 |

1507 |

B. Natural gas

|

|

1990 |

1995 |

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2015 |

2020 |

2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Unit: million cubic meters |

||||||||

|

Production |

8242 |

12594 |

17673 |

52189 |

56814 |

38302 |

61780 |

67000 |

|

Exports |

0 |

0 |

0 |

15480 |

12975 |

258 |

2141 |

9758 |

|

Imports |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6973 |

2150 |

6680 |

Source: IEA Key World Oil Statistics; IEA Natural Gas Statistics.

The government controls retail electricity and fuel prices and provides subsidies to the national energy producers, the Egyptian General Petroleum Corporation and the Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Corporation. The fuel products subject to subsidies include heavy oil (mazut), diesel, kerosene, butane gas, natural gas and gasoline (95, 92, 80 octane).

These subsidies compensate energy producers for the price controls (as costs for energy production exceed the controlled price), taking into account prices in international markets. Energy subsidies were estimated at 52% of total costs in electricity generation and 24% of total costs in refineries in the early 2010s (Griffin et al., 2016). The price-to-cost ratio has significantly risen since, reaching almost 100% before the recent surge in energy prices in international markets.

Electricity prices are determined according to consumption brackets: users face different prices depending on how much electricity they use. Fuel prices do not vary with consumption but differ between households and businesses. Since early 2022, against the backdrop of surging energy prices in international markets and currency depreciation, the price per litre has been raised in steps. By the end of 2023, they reached EGP 8.25, up from EGP 6.75 for diesel; EGP 10, up from EGP 7.25 for gasoline 80; EGP 11.5, up from EGP 8.5 for gasoline 92; EGP 12.5, up from EGP 9.5 for gasoline 95; and EGP 6 000, up from EGP 4 200 per ton for diesel for industries.

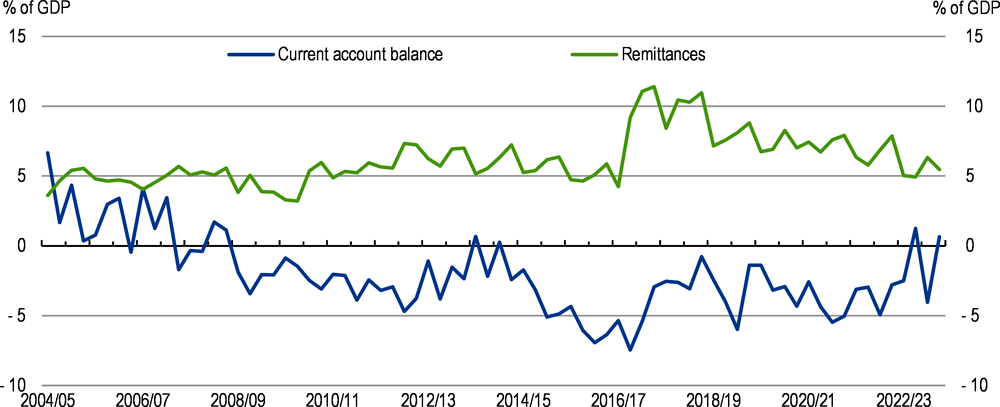

The current account remained in deficit over the 2010s (Figure 2.5) but recently improved, reflecting the aforementioned improvement of the trade balance. Remittances by Egyptian workers abroad amounted to USD 31.4 billion in FY 2021/22, almost fully offsetting the trade deficit. Only a few neighbouring countries record a larger contribution of remittances as a share of GDP, namely Jordan (around 10% of GDP) and Morocco (around 8% of GDP). Remittances shrank by almost a third in FY 2022/23 according to balance of payments statistics, partly reflecting decisions in Gulf Cooperation Countries to restrict jobs to nationals. Expectations of further exchange rate adjustments may have delayed remittances, or led them to be carried out via the parallel market.

Figure 2.5. Remittances support the current account balance

Note: Data refer to fiscal years (from July to June of the following year). Remittances data is based on ITRS incorporating results of a survey conducted by CAPMAS.

Source: Central Bank of Egypt; Ministry of Planning and Economic Development; and CEIC.

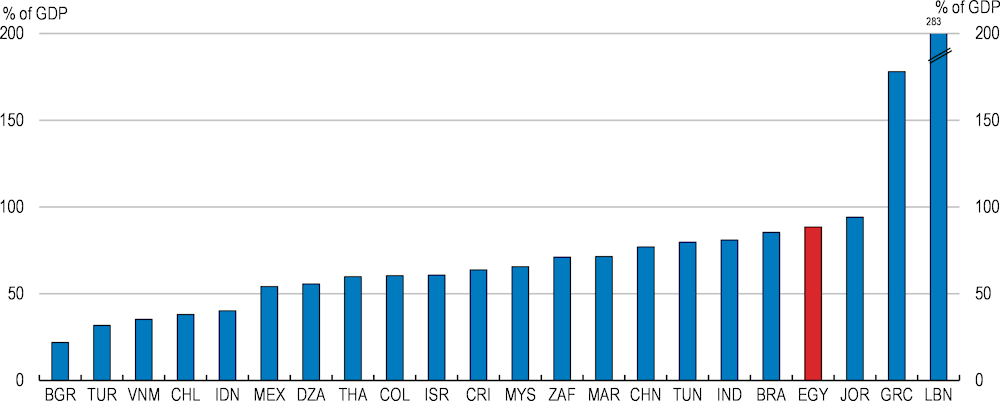

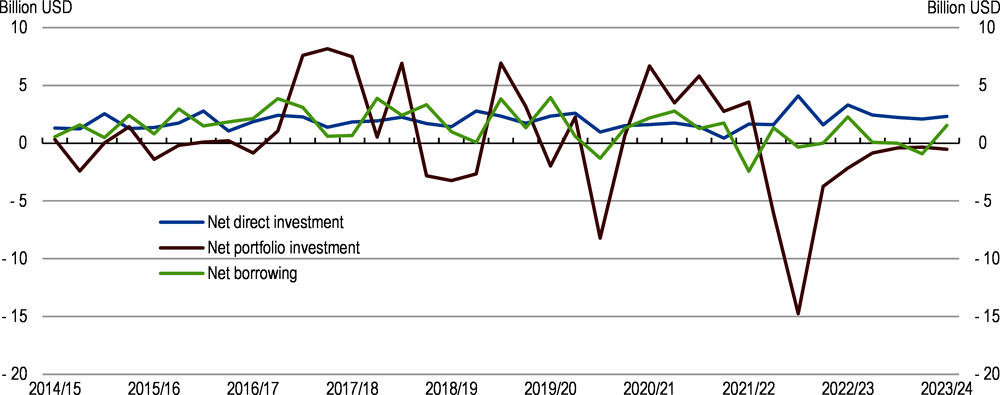

Capital inflows to Egypt have been significant but volatile over the past decade (Figure 2.6). In the five years prior to the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, portfolio investment and borrowing from abroad averaged USD 1.4 billion and 2.0 billion, respectively, per quarter, mostly on account of the government sector. Capital from abroad has contributed to financing the accumulation of public debt (Figure 2.7). More recently, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows have regained momentum as they stood at USD 2.3 billion on average per quarter over the year up to September 2023. At the same time, portfolio outflows diminished to USD 0.5 billion on average per quarter over the same period.

Figure 2.6. Capital inflows have been volatile

Note: Data refer to fiscal years (from July to June of the following year).

Source: Central Bank of Egypt.

Figure 2.7. Public debt is high

General government gross debt, 2022 or latest value

2.1.2. Major external shocks exacerbated existing imbalances and fuelled inflation

The COVID-19 pandemic caused considerable damage in Egypt. The authorities reacted swiftly. They sealed the border and imposed social distancing measures for three months starting in March 2020, including the closure of public places such as restaurants and bars as well as public transportation at night. Some sectors were severely affected, notably accommodation (Table 2.3). Tourism revenue plummeted from USD 9.9 billion in FY2019/20 to 4.9 billion in FY 2020/21, before rebounding strongly (see below).

Nonetheless, Egypt weathered the COVID-19 crisis relatively well owing to a relatively short period of containment and various government support measures, which amounted to EGP 100 billion (1.5% of FY 2019/20 GDP). Private consumption held up well, unlike in OECD countries, where it dropped substantially. Both investment and exports contracted somewhat upon the outbreak of the pandemic, but rebounded relatively quickly, recovering to pre-crisis levels within a few quarters.

Table 2.3. The impact of the recent shocks varied across sectors

2-quarter per cent change in volume terms

|

Agriculture |

Mining |

Manufacturing |

Electricity |

Water |

Construction |

Transportation |

Communication |

Information |

Suez Canal |

Wholesale and retail |

Finance |

Insurance |

Accommodation and food |

Real estate |

Government |

Social services |

Total GDP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

COVID-19 shock: Q3-Q4 FY2019/20 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

-15.8 |

22.5 |

-12.9 |

11.5 |

-10.5 |

7.4 |

-3.9 |

0.4 |

-1.9 |

7.4 |

-19.5 |

-11.3 |

12.5 |

-41.8 |

6.9 |

4.4 |

4.5 |

-5.1 |

|

Russia/Ukraine war shock: Q3-Q4 FY 2021/22 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

-18.0 |

24.2 |

-8.1 |

12.1 |

-11.0 |

1.0 |

-5.9 |

-1.6 |

-3.7 |

22.7 |

-21.3 |

-11.8 |

12.0 |

1.0 |

4.4 |

5.2 |

3.7 |

-4.4 |

Note: The rate of change refers to the sum of value added for the two consecutive quarters during which each shock occurred compared with the sum of value added during the two preceding quarters.

Source: Ministry of Planning and Economic Development; OECD calculation.

Upon the outbreak of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, energy and food prices, which had already increased before the war, soared in international markets. Egypt was hit particularly hard due to its reliance on imported foodstuffs, including wheat. Russia and Ukraine together accounted for 30% of global wheat exports (OECD, 2022a). Supply disruptions occurred as a result, which contributed to fuel domestic food inflation (CSIS, 2023). The tourism sector was affected again, as Russians and Ukrainians had accounted for around one-third of tourist arrivals in Egypt prior to the war. The wholesale and retail trade sector was the most affected by the war (Table 2.3). Private consumption, which did not contract even during the COVID-19 crisis, declined immediately following the onset of the war owing to high food prices.

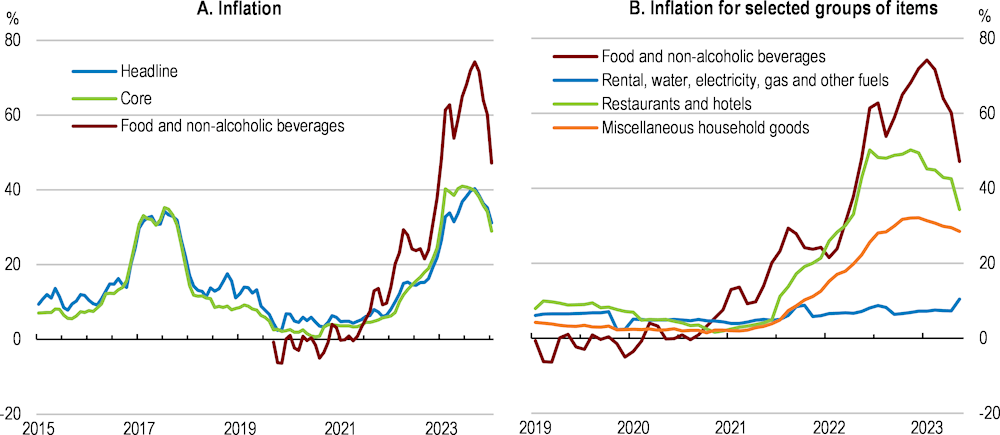

Massive capital outflows amounting to around USD 20 billion (4.7% of GDP) occurred upon the outbreak of the war. This took place within the context of substantial risks of capital flight from emerging market economies in general, as international financial market conditions tightened following policy interest hikes in advanced economies (OECD, 2022b). Egypt was particularly vulnerable to such capital outflows, given its macroeconomic imbalances, reflected in high public debt financed by capital abroad, and its direct trade exposure to Russia and Ukraine. GDP growth slowed down in 2022, while cost-push inflation soared (Figure 2.8). Food price inflation was driven by high prices in international markets. In contrast, retail energy prices were kept in check by price controls (Box 2.2). The rise in food prices was aggravated by supply-chain issues, such as those related to shipping and transport capacity and raw material hoarding due to uncertainty. As food accounts for a large share of the consumption basket, especially for poor households, the burden has been disproportionately borne by the poor.

Figure 2.8. Inflation has surged to record highs

12-month rate of change

Note: Nationwide inflation rate (rate of change in the index over a year earlier). FY 2018/19 base year for consumer price weights.

Source: Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics; Central Bank of Egypt.

Inflation has been broad-based since early 2022. Headline urban consumer price inflation and the associated core measure stood at 29.8% and 29.0%, respectively, in January 2024. Food prices in international markets have receded since mid-2022, but they have strongly increased domestically, against the backdrop of successive devaluations of the currency (see below). According to the central bank, the impact of exchange rate movements on domestic inflation is instantaneous and peaks after three months. The surge in imported food prices has boosted the price of other products, including processed food products, which contributed to both headline and core inflation. The central bank estimates that core food items accounted for approximately ¾ of the increase in headline and core inflation on average during the first three months of 2023. After peaking at around 40%, inflation has slowed recently due to favourable base effects on a year-on-year basis. However, it has recently picked up on a month-on-month basis, driven by price hikes in the services and utilities sectors and also likely reflecting cost pressures arising from transactions in the parallel market, which has witnessed considerable depreciation (see Figure 2.15, further down).

Private consumption has been sustained by fiscal support. Three fiscal packages were introduced in 2022, amounting to 2.7% of FY 2021/22 GDP in total (Box 2.3), which have buttressed household disposable income. Two further packages were introduced in 2023, totalling around 2.2% of FY2022/23 GDP. The support measures took various forms ranging from an increase in public sector wages and pensions to an expansion of cash-transfer programmes targeted to the poor (Box 2.3). In the meantime, the share of consumer spending devoted to essentials likely rose, with car sales, for instance, down by 65% in October 2023 on a year earlier. To provide further impetus, the minimum wage in the private sector was increased from EGP 3 000 to 3 500, and the minimum pension from EGP 1 105 to 1 300 in January 2024. Furthermore, the government announced a substantial increase in the public sector minimum wage and various social benefits in February 2024 (Box 2.3). There are no reliable timely data on retail sales, which makes it difficult to assess recent developments in private consumption.

Box 2.3. Fiscal packages introduced since March 2022

The government has announced several fiscal packages since March 2022 to protect those vulnerable to rising costs of living. The increase in the income tax exemption featuring in the 2022 and April 2023 fiscal packages was finally adopted in mid-2023 in separate legislation.

April 2022 package: EGP 130 billion (1.7% of FY 2021/22 GDP)

Increase in public sector wages; increase in pensions by 13%; extension of the Takaful and Karama cash-transfer programmes to an additional 450 000 families; increase in the income tax exemption threshold from EGP 24 000 to 30 000.

September 2022 package: EGP 12 billion (0.2% of FY 2021/22 GDP)

Extension of the Takaful and Karama programmes to an additional one million families; one-off allowance for six months for low-wage workers in the public sector and low-pension earners.

November 2022 package: EGP 67 billion (0.9% of FY 2021/22 GDP)

Increase in the minimum wage in the public sector to EGP 3 000 from 2 700; one-off allowance of EGP 300 per month for workers in the public sector and pensioners; support for certain families eligible for the ration card (tranches of EGP 100/200/300) until June 2023; increase in the income tax exemption threshold from EGP 24 000 to 30 000; maintaining the electricity prices unchanged (price control mechanism, see Box 2.2) until June 2023.

April 2023 package: EGP 165 billion (2.1% of FY 2021/22 GDP)

Increase in the minimum wage in the public sector to EGP 3 500 from 3 000; increase in pensions by 15%; increase in the amount of cash-transfer programmes by 25% from April 2023; increase in the income tax exemption threshold from EGP 24 000 to 36 000.

October 2023 package: EGP 60 billion (0.6% of FY 2022/23 GDP)

Increase in the public sector minimum wage to EGP 4 000 from 3 500; further income support for low-paid pensioners; increase in the income tax exemption threshold from EGP 36 000 to 45 000.

February 2024 package: EGP 180 billion (1.3% of FY 2023/24 GDP)

Increase in the public sector minimum wage to EGP 6 000 from 4 000; broad-based increase in public sector wages by EGP 1 000 - 1 200; increase in pensions by 15%; increase in the amount of the Takaful and Karama benefits by 15%; increase in the income tax exemption threshold from EGP 45 000 to EGP 60 000.

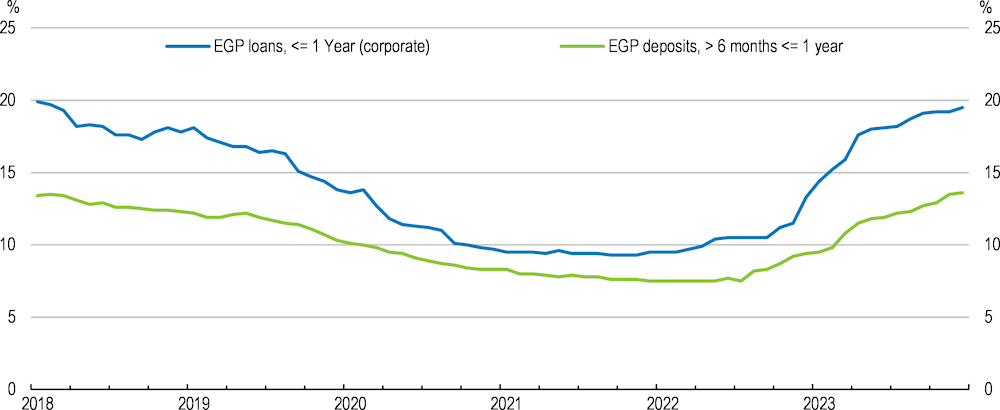

Since mid-2022, financing conditions have tightened (Figure 2.9), foreign currency shortages have become more binding and business sentiment has soured. Against this backdrop, investment declined sharply. Foreign currency shortages are reflected in low foreign exchange reserves, even though they increased over the past 17 months to around 10% of GDP, and negative net foreign assets held by Egyptian banks (Figure 2.10). Banks ration foreign currency, which has contributed to backlogs at ports (as importers cannot meet their obligations to pay in foreign currency). Currency shortages are notably affecting the provision of electricity, as they hamper imports of natural gas and heavy fuel oil, leading to reduced operations in some power plants since the summer of 2023 with frequent blackouts. The divestment programme (Chapter 3), disbursement of the next tranches of the IMF Extended Fund Facility arrangement and financial support provided by Gulf Cooperation Countries would help alleviate them.

Figure 2.9. Financing conditions for businesses have deteriorated

Note: Weighted average rates for a sample of banks whose deposits represent around 80% of total deposits in the banking system and calculated on a monthly basis.

Source: Central Bank of Egypt.

The authorities introduced additional import measures in 2022 against the backdrop of worsened balance of payment prospects and the shortage of foreign currency. These included full advance payments in foreign currency, in lieu of a down-payment, as well as changes in the required documentation. Most of these measures were removed at the end of the year, but they exacerbated import backlogs. The latter have weighed down exports, due to their import content.

Figure 2.10. Both foreign exchange reserves and foreign assets of banks are low

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook - October 2023 database; Ministry of Planning and Economic Development; Central Bank of Egypt.

Overall, GDP growth has slowed in FY 2022/23 to 3.8% (Table 2.4). According to the OECD projections, GDP growth is set to pick up in due course (Table 2.4). Inflation is likely to remain high for some time, continuing to exert a drag on household consumption. Consumption will recover, however, insofar as inflation declines, despite the gradual withdrawal of fiscal support. In contrast, the recovery of business investment is set to be subdued as funding conditions will ease only gradually. The OECD projections assume that public investment will moderate only somewhat, while the government announced its intention to curtail large-scale projects (see below).

The current account deficit narrowed to USD 4.7 billion in FY 2022/23 from USD 16.6 billion a year earlier, helped by a shrinking trade deficit (Table 2.4). The decline in food prices in international markets likely contributed to reduce the trade deficit. Overall, non-petroleum imports declined by USD 16.4 billion, partly due to the aforementioned temporary import measures. Tourism and Suez Canal revenues increased by 26.8% to USD 1.8 billion and by 25.2% to USD 2.9 billion, respectively, contributing to the improvement in the overall trade balance.

Table 2.4. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

|

|

FY2020/21 |

FY21/22 |

FY22/23 |

FY23/24 |

FY24/25 |

FY25/26 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Current prices (EGP billion) |

|||||

|

GDP at market prices |

6663.1 |

6.6 |

3.8 |

3.2 |

4.4 |

5.1 |

|

Private consumption |

5730.6 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

3.0 |

4.2 |

4.7 |

|

Government consumption |

503.6 |

- 17.3 |

- 2.8 |

6.5 |

6.2 |

6.5 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

882.5 |

33.5 |

- 24.1 |

-1.4 |

1.5 |

3.2 |

|

Total domestic demand |

7245.1 |

5.4 |

- 0.7 |

2.7 |

4.6 |

4.9 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

703.7 |

51.7 |

31.4 |

5.4 |

6.5 |

7.1 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

1285.7 |

25.2 |

1.1 |

2.9 |

4.1 |

4.5 |

|

Net exports |

-582.0 |

0.6 |

4.5 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

|

Memorandum items |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GDP deflator |

_ |

10.4 |

24.8 |

29.6 |

14.2 |

7.3 |

|

Consumer price index |

_ |

9.7 |

25.1 |

32.0 |

15.9 |

7.5 |

|

Core inflation index |

_ |

7.9 |

29.3 |

30.7 |

16.8 |

7.9 |

|

Budget sector financial balance (% of GDP) |

_ |

- 6.1 |

- 6.0 |

- 7.8 |

- 7.0 |

- 6.5 |

|

Central government gross debt (% of GDP) |

_ |

87.2 |

95.7 |

92.0 |

86.9 |

80.7 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

_ |

- 3.5 |

- 1.2 |

- 0.8 |

- 0.8 |

- 0.7 |

Note: Data refer to fiscal years from July to June of the following year. “Consumer price index” refers to the nationwide inflation rate. The Budget sector comprises central administrative units, local administrative units and public service authorities. The numbers for FY2023/24 onwards are OECD projections, based on the technical assumption of an unchanged official exchange rate but taking also into account the gap between the official and the parallel rate.

Source: Update of the OECD Economic Outlook November 2023, Ministry of Planning and Economic Development; Ministry of Finance; Central Bank of Egypt.

The current account deficit is projected to stabilise around ¾ per cent of GDP over the next two years. Easing import backlogs would support exports given the high import intensity of exports. Suez Canal receipts were down 47% in January 2024 over a year earlier following attacks on cargo ships and the ensuing diversion of traffic, but are expected to recover on the assumption that security will improve (Box 2.4). Tourism receipts have been affected by the geopolitical tensions in the region over the past months but are also expected to recover.

Box 2.4. The role of the Suez Canal in the Egyptian economy

Suez Canal traffic

Opened in 1869, the Suez Canal is a major trade route between Europe, Asia and Africa and plays a key role in global supply chains, as illustrated in 2021 when a huge container ship got stuck in the canal, causing a massive maritime traffic jam. It represents 11 to 13% of global maritime trade in volume terms according to the International Transportation Forum. The Suez Canal recorded an annual traffic of over 25 900 vessels and 1.5 billion tonnes of cargo in FY2022/23 according to the authorities, a volume of cargo around five times greater than that going through the Panama Canal. Suez Canal traffic accounted for 1.5% of GDP and generated 5% of total government revenue in FY 2021/22. The revenue from Suez Canal traffic reached USD 9.4 billion in FY 2022/23, a record high.

The Suez Canal is managed, operated and maintained by the Suez Canal Authority, established in 1956. Its capacity has recently been doubled, to allow around 100 vessels to go through on average per day. Container ships and oil tankers account for 28% and 27% of the traffic, respectively, followed by bulk carriers (23%), general cargo ships (8%), car carriers (5%) and liquefied natural gas (LNG) tankers (4%) according to the Suez Canal Authority.

The Suez Canal Authority levies a toll on through traffic, which depends on the type of vessel and tonnage. The toll is denominated in special drawing rights and should be paid in one of 10 designated foreign currencies.

The Suez Canal Economic Zone

In addition to the expansion of the Suez Canal, the Egyptian government set up a 455 km2 Suez Canal Economic Zone straddling six maritime ports in 2015, to serve as an international logistics hub as well as a platform for industry, leveraging the strategic location of the Suez Canal to develop export-oriented industries.

The General Authority for the Suez Canal Economic Zone (SCZone Authority) supervises the activities in the economic zone. It is an autonomous institution with regulatory powers in the areas of operation, staffing, budget and funding, partnerships with developers and business facilitation services. The SCZone Authority has worked with the OECD since 2017 to develop a legal framework to attract investments based on international standards and best practices, aiming at the implementation of policy reforms in investment regulations, tax incentives, infrastructure governance and financing mechanisms.

Source: Suez Canal Authority, Navigation Statistics; information provided by the Egyptian authorities.

The risks surrounding the projections are skewed to the downside and partly overlap (Table 2.5). First, inflation may turn out to be more persistent than foreseen, due to the lagged effects of inflation on wages and the recent minimum wage hikes. A terms-of-trade shock reflecting higher international food and energy prices would worsen the current account deficit and fuel inflation. Capital outflows would generate further currency depreciation pressure. Further inflation would cause a significant strain on the budget with an increasingly limited scope to compensate for rising living costs. Indeed, significantly worsened prospects for the public finances would further harm international investor confidence, which in turn could discourage capital inflows. This would further tighten financing conditions due to heightened uncertainty. Finally, Egypt is exposed to the risk of droughts or high temperatures, not least given the importance of the agricultural sector.

Table 2.5. Events that could lead to major changes to the outlook

|

Shock |

Possible impact |

|---|---|

|

Further escalation of geopolitical tensions in neighboring countries. |

Tourism and Suez Canal receipts may be further affected, with negative effects on the budget and the current account. Refugee inflows would strain social services and imply fiscal costs. Rising defense expenditure would also weigh on the budget. |

|

Abrupt rise in food and energy prices in international markets. |

Inflation would rise, aggravating the cost-of-living crisis. Food and energy subsidies would significantly increase, straining the budget. |

|

Significant tightening in international financial markets. |

Government bond yields would rise abruptly and financing conditions would further deteriorate. |

|

Natural disasters such as droughts. |

Agricultural production would be substantially damaged. Food prices would abruptly rise, reducing consumption significantly, aggravating food security and undernutrition. |

2.2. Macroeconomic stability needs to be restored

The prospective recovery is fragile. While continuing targeted fiscal support to the most vulnerable in the face of high living costs, the government should contain overall expenditure by extending its commitment to reduce the pace of the implementation of public investment projects, to help bring inflation under control and safeguard financial stability. The overall budget balance is expected to improve under the IMF programme, which would help buttress investor confidence, reducing high debt servicing costs, which amount to 43% of government revenue. While Egypt needs to reduce its reliance on foreign capital in the long run, restoring international investor confidence and capital inflows will help to ensure financial stability in the short run.

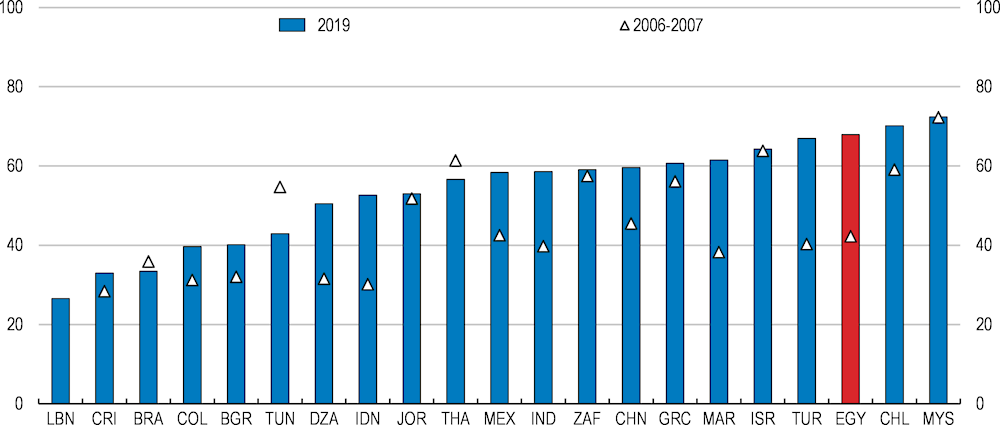

2.2.1. Financial instability risks are high

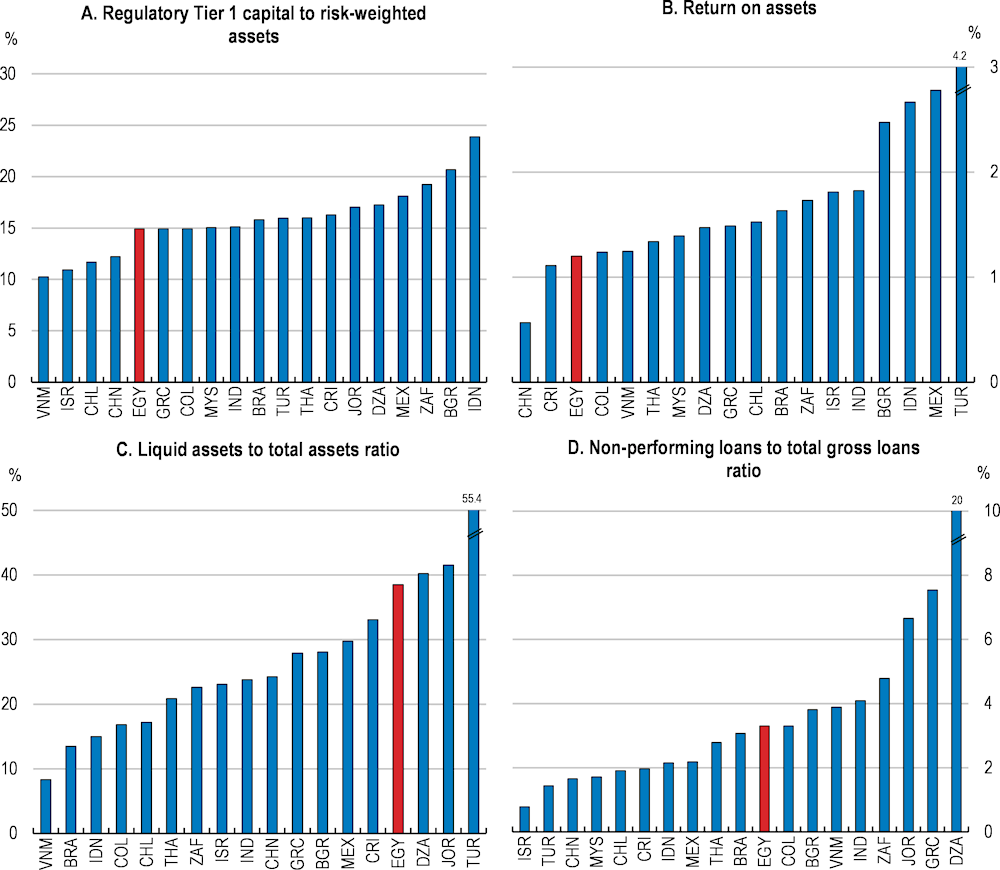

Bank assets as a ratio to GDP stood at 100.3% in 2021, according to World Bank data, which is relatively high by emerging market standards. The banking sector appears to be sound (Figure 2.11), and the Central Bank of Egypt monitors banks’ capital adequacy ratio and liquidity ratio. Lending to the private sector is low (Chapter 3), while domestic banks are heavily exposed to domestic sovereign debt (Figure 2.12), possibly reflecting a preference for safer and more liquid public assets (Bouis, 2019). However, sovereign risk is not fully taken into account in the capital adequacy ratio, as zero weight is assigned to government securities.

Figure 2.11. The banking system seems sound against the background of low risk taking

Q3 2023 or latest available figures

The sovereign-bank nexus can be a source of financial instability (OECD, 2023a). The transmission of risks between the sovereign and banking sectors is significant both directly and indirectly through the non-financial corporate sector. An increase in sovereign risks can adversely affect banks’ balance sheets and lending appetite, especially in countries with higher fiscal vulnerabilities, and constrain funding for the non-financial corporate sector, reducing its capital expenditure (IMF, 2022a). Significant repricing of Egyptian sovereign debt could occur, affecting the quality of bank assets. In that case, investor confidence towards the government could be further harmed insofar as investors expect the government to rescue troubled banks, which can in turn deteriorate the worth of the government’s securities held by banks.

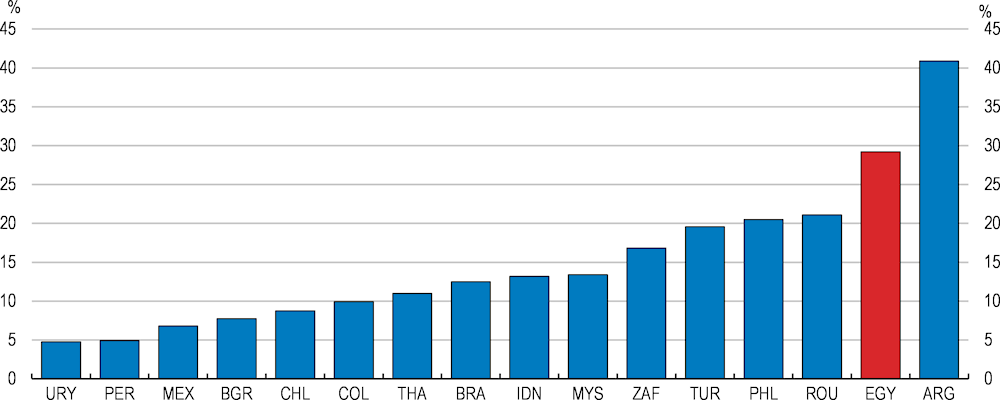

Figure 2.12. Banks’ exposure to sovereign debt is high in Egypt

Share of outstanding sovereign debt held by domestic banks in total bank claims, %, 2023 Q2 or latest

Note: Total claims are defined as the sum of claims of domestic depository corporations on domestic borrowers and non-resident borrowers. Data for Peru are for 2022 Q1.

Source: IMF, Sovereign Debt Investor Base dataset; IMF, International Financial Statistics; and OECD calculations.

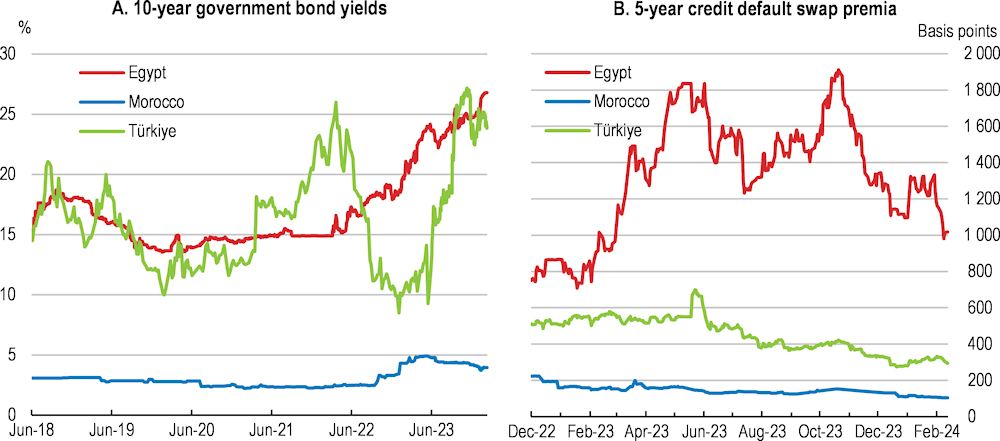

Given high public debt, Egypt is particularly vulnerable to abrupt changes in investor confidence. Global financial market conditions tightened against the backdrop of a rapid rise in policy interest rates and banking sector vulnerabilities in the first half of 2023 (OECD, 2023a). This increased vulnerabilities in emerging market economies, adding to debt servicing costs and capital outflows and reducing credit availability for borrowers relying on foreign lenders (OECD, 2023a). In this context, investor confidence in Egypt has suffered, and although global financial market conditions have improved since then, financing conditions in Egypt remain tight overall (Figure 2.13).

The cost of international market funding has risen since early 2022. Since then, the government has sought to diversify its debt portfolio and instruments further. For instance, Egypt issued Samurai bonds denominated in Japanese yen, in March 2022 and again in early November 2023, both times for around USD 500 million. In October 2023, it issued its first Panda bond in China with a size of CNY 3.5 billion (around USD 480 million), a tenor of three years and a 3.5% coupon, fully guaranteed by two international financial institutions. The Egyptian government also placed so-called sukuk (Islamic bonds) with a 10.9% coupon in the international market in February 2023 (Box 2.5). Nonetheless, the government continues to face difficulties in funding as investors require higher yields than the government is ready to offer.

The government faces large financing needs, estimated at close to 35% of GDP in FY 2023/24 – of which around 28% of GDP for principal repayment and rollovers and 7% of GDP for the budget deficit. While the primary balance is projected to be in surplus, the government is expected to spend 9% of GDP on interest payments. For FY 2024/25, financing needs are estimated to decline slightly to just under 28% of GDP, but interest payments would still top 9% of GDP. The average maturity has increased in recent years, to 3.4 years by mid-2022. The government intends to increase the average maturity further to five years by the end of FY 2026/27 by diversifying debt instruments to reduce pressures arising from debt rollover.

Figure 2.13. Egyptian sovereign bonds yields have risen

Box 2.5. Islamic finance in Egypt

Egypt issued its first sovereign sukuk (Islamic bond), worth USD 1.5 billion (EGP 46 billion) in February 2023, amidst investor interest in sukuk in the international bond market. Türkiye for example launched its second sovereign sukuk in October 2022, for USD 2.5 billion. Islamic finance instruments, that typically involve various forms of leasing, generated around 5% of the total volume of banking sector financing in Egypt in 2022, according to the Egyptian Islamic Finance Association, and 6% of all deposits in March 2023. Islamic financing in Egypt remains small by international standards, with a share in total banking assets of 4% in 2021, as against 6% in Türkiye, 30% in Jordan, 32% in Malaysia or 77% in Saudi Arabia.

14 banks are authorised by the CBE to offer Islamic products, three of which are fully Islamic banks: Faisal Islamic Bank of Egypt, Al Baraka Bank of Egypt, and Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank - Egypt. Although Islamic banking services have been authorised since 1963, their uptake remained limited until the 2018 revisions to the Capital Markets Law (which included provisions on corporate sukuk) which led to more interest and expansion. There are now 254 Egyptian Islamic bank branches, representing 5% of the total number of branches in the domestic banking market, and servicing roughly 3 million customers. Since 2018, six corporate sukuks have been issued, totalling EGP 12.8 billion.

Source: Egyptian Islamic Finance Association (2023), bi-annual report; IFSI (2022), Islamic Financial Services Industry Stability Report.

2.2.2. Monetary policy has been tightened

The Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) is responsible for monetary policy, exchange rate policy as well as banking sector supervision under Law 194/2020. Article 6 of this law stipulates that the CBE should seek to protect the integrity of the banking and monetary system and to stabilise prices within the framework of the state’s public economic policy. The CBE, however, operates in a broader institutional policy framework that includes the Coordinating Council of the Central Bank’s Monetary Policy and the Government’s Fiscal Policy headed by the Prime Minister, as well as the National Council of Payments chaired by the President of Egypt.

The CBE aims to bring headline inflation down within its target of 7% (± 2 percentage points) by end-2024 and 5% (± 2 percentage points) by end-2026. It seeks to achieve the near-term inflation target and price stability over the medium term while minimising economic volatility. Egypt’s monetary policy framework is in the process of moving towards a flexible inflation targeting regime (IMF, 2022b), akin to the ones in Costa Rica and Romania. The CBE is currently developing a tool to gauge inflation expectations. The CBE assesses the transmission of monetary policy to various interest rates at different maturities, such as interbank rates, banking sector deposit and lending rates, and government bond yields. According to the CBE, monetary policy affects economic activity with a lag of one to two years. Transmission to the economy is likely less potent than in most OECD countries given the large share of the informal sector.

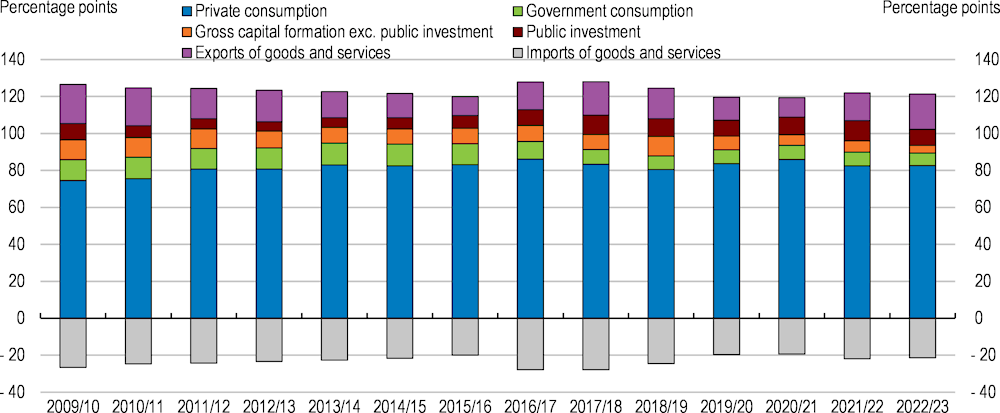

Faced with surging inflation (Figure 2.8), the CBE has raised the policy interest rate by 1 300 basis points since early 2022, to 21.75%, one of the highest levels across the region (Figure 2.14). It also raised banks’ required reserve ratio from 14% to 18% in September 2022. The effects of monetary policy tightening on inflation have been limited by subsidised lending. The CBE has committed to refrain from extending, renewing or introducing any new subsidised lending schemes, with the outstanding lending transferred to the government to be wound down (IMF, 2023a). However, a new subsidised lending scheme managed by the Ministry of Finance was launched in January 2023. This scheme aims to support the agriculture and manufacturing sectors at a rate that currently stands at 11%, which is below market interest rates (Figure 2.9). This lending scheme will run for five years with a total balance of EGP 150 billion, of which EGP 140 billion is for working capital and the rest for capital goods financing, with a ceiling for each company of EGP 75 million to maximise the number of beneficiaries.

The effectiveness of monetary policy can be enhanced by improving the policy framework. Across emerging market economies, central bank independence and transparency are among the most important factors to strengthen the monetary policy transmission mechanism, along with the adoption of an inflation targeting regime (Brandao-Marques et al., 2020). In Mexico, where the role of the interest rate channel is weak due to relatively limited financial inclusion, monetary policy has gained traction as inflation expectations were stabilised by strengthening the independence and transparency of the central bank, which boosted confidence that it is committed to price stability (Banco de Mexico, 2016). In this respect, it was important to clearly announce its inflation target in the medium term, release monetary policy statements that provide sufficient information about monetary policy decision-making, and publish quarterly reports including the central bank’s forecasts. Costa Rica has reformed its monetary policy framework along similar lines (OECD, 2018a).

Figure 2.14. The policy interest rate has been raised substantially

The CBE faces difficult policy trade-offs as the economy has slowed but inflation remains high and second-round effects may turn out to be stronger than expected. A renewed surge in commodity prices in international markets would strongly affect inflation in Egypt. The continuing war in Ukraine might lead to renewed pressures on the prices of wheat, corn, edible oils, and fertilisers. When it hiked policy interest rates in February 2024, the CBE noted that inflation had not moderated as it had expected, implying that underlying inflationary pressure persists. The policy rate may need to be lifted further if inflation expectations rise, which would also help to strengthen the confidence in the central bank. Further rate hikes, however, may affect financial stability given the high level of public debt. Although the bulk thereof carries a fixed rate, its average maturity is relatively short (see above), implying that higher interest rates would quickly entail an increasing burden. Moreover, weak monetary transmission means that larger policy interest rate hikes are needed, all else equal, to achieve the objective of price stability.

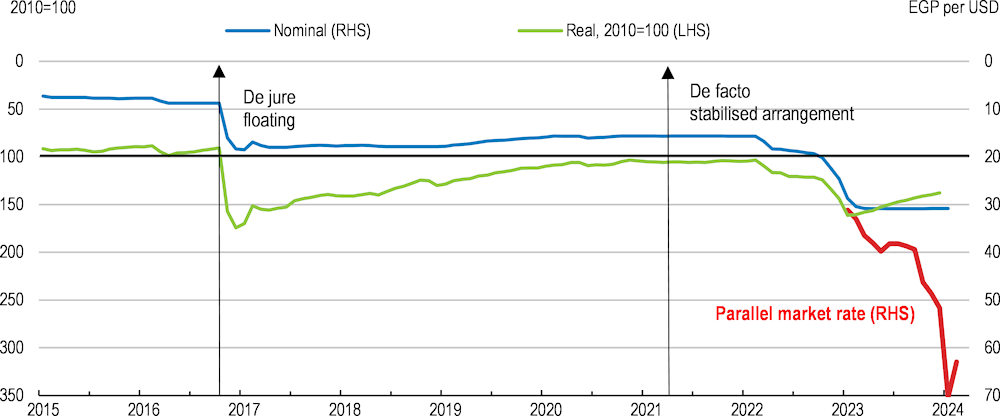

2.2.3. The Egyptian pound lost half of its value against the dollar in the year to March 2023

The CBE has long operated a managed exchange rate regime, which has led to overvaluation (IMF, 2021), thereby allowing for imports of commodities priced in US dollars at lower cost but impeding export growth. In November 2016, under a previous IMF programme, the CBE adopted a de jure floating exchange rate regime. The CBE intervened directly in the foreign exchange market following the shocks imparted by COVID-19 and the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, consistent with its mandate to preserve financial stability. The de facto exchange rate regime has been reclassified as a stabilised arrangement by the IMF (Figure 2.15), which can be described as exchange rate steering without a specific exchange rate path or target.

In 2022, the CBE began to loosen this managed exchange rate regime with a view to moving towards a market-determined exchange rate system. The currency has been devalued in steps, loosing around half of its value against the US dollar since early 2022 (Figure 2.15). Thereafter, it has barely moved, even as pressures have mounted, implying significant real appreciation. In October 2023, the CBE announced restrictions on credit card payments both at home and abroad as well as on the use of debit cards to withdraw foreign currency. Demand for foreign currency that is not met by the banks is partly directed to the parallel market where the rate has increasingly diverged considerably from the official rate (Figure 2.15). Facing a similar situation, Türkiye introduced measures from 2018, including a foreign exchange-protected deposit scheme, which compensated savers for potential exchange rate losses (OECD, 2023b). The authorities also actively intervened in the foreign exchange market (World Bank, 2022b). The Turkish lira lost 86% of its value against the US dollar between early 2018 and mid-2023, illustrating that propping up the currency against market forces is costly and unsustainable (OECD, 2023b; IMF, 2023b).

The Egyptian authorities should reduce control over the exchange rate gradually, subject to interventions to keep volatility in check. Restoring investor confidence by reducing macroeconomic imbalances and extending structural reform efforts will help durably support the exchange rate. Relaxing restrictions on the official exchange rate is likely to lead it to depreciate and move closer to the rate in the parallel market but can also be expected to lead to the latter’s appreciation. This may impart some near-term inflationary impulse, as seen in late 2022 following the successive devaluations, and call for raising the policy rate further, as the Central Bank of Türkiye has recently had to do in a similar context. High inflation is particularly painful for the most vulnerable, underscoring the importance of continuing to strengthen the social safety net by targeting fiscal support more (see below).

Following the presidential election in December 2023, plans were floated to introduce a new strategy to increase foreign exchange inflows. This strategy includes specific targets to be achieved by 2030 in terms of exports, tourism revenues, remittances, FDI, and Suez Canal revenues. The strategy also advocates moving towards a flexible exchange rate regime, thereby closing the gap between the official exchange rate and the parallel market rate while reducing inflation to single-digit levels by the end of 2025.

Figure 2.15. The official exchange rate shifted substantially in 2022

Note: Real exchange rate calculated based on consumer price indices. Latest data point for the parallel market rate is 11 February 2024.

Source: Central Bank of Egypt; IMF, International Financial Statistics database; parallelrate.org; and OECD calculation.

2.2.4. Fiscal space is limited

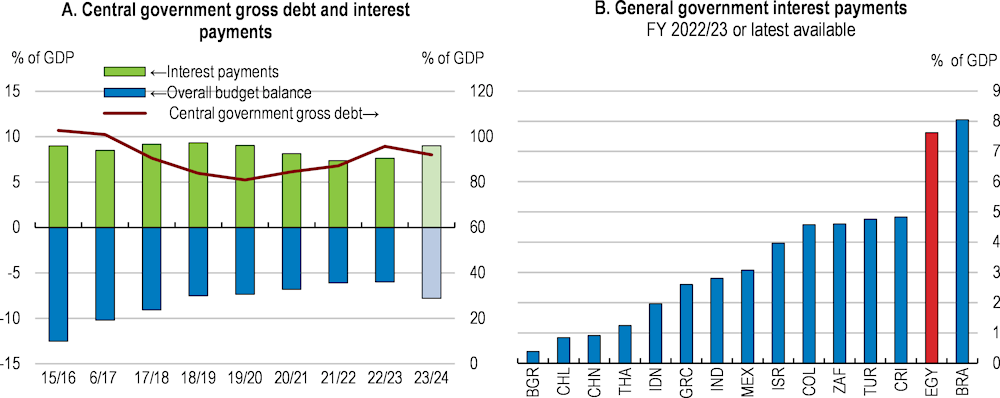

Given the immediate need to protect the most vulnerable people against the cost-of-living crisis, the government has to further step up its efforts to strengthen revenue collection and rationalise expenditure. The budget deficit stood at 6% of GDP in FY2022/23, virtually unchanged from the previous fiscal year, despite higher-than-foreseen spending on food and energy subsidies and a series of fiscal packages (Box 2.3). The budget has exhibited a primary surplus in recent years but interest payments take a large toll, at 7.6% of GDP in FY2022/23, and push up public debt (Figure 2.16). The initial Budget for the ongoing fiscal year (FY 2023/24) featured higher interest payments, a primary surplus of 2.5% of GDP and a headline deficit of 7% of GDP.

Figure 2.16. Interest payments weigh on the budget balance

Note: For Egypt, the data for FY 2022/23 refer to the latest estimate in Budget FY 2023/24. OECD projections for FY 2023/24.

Source: Ministry of Finance, Monthly Finance Report, December 2023 and Budget FY 2023/24; Ministry of Planning and Economic Development; and IMF, Government Finance Statistics.

As global food and energy prices have declined from 2022 peaks, and minimum wages have now been increased to take account of past inflation, fiscal support should become more targeted on the most vulnerable (OECD, 2023a). Budget FY 2023/24 is broadly in line with this approach. The government aims to reduce broad-based energy subsidies by aligning domestic energy prices with those in international markets (Box 2.2) to EGP 119 billion (1% of GDP), and to withdraw them altogether in 2025. It also plans to limit food subsidies to EGP 128 billion (1.1% of GDP), which could be further reduced by strengthening the targeted approach so that they reach only those most in need (Box 2.1). At the same time, it is set to raise spending on social safety programmes to EGP 31 billion (0.3% of GDP), and announced an increase in the Takaful and Karama benefits in February 2024 (Box 2.3). The government has continued to increase the tax exemption threshold for low- and middle-income households from EGP 24 000 at the beginning of the FY 2023/24 to 60 000 as per the February 2024 fiscal package.

To help combat inflation, total fiscal expenditure needs to be restrained. The government is committed to containing public investment, postponing the implementation of new projects that have not started and require US dollar financing, and shifting some projects outside of the budget perimeter to the private sector. Also, the government intends to postpone any projects that are not deemed of “extreme necessity”, though the definition of the latter is not clear. The total amount of the deferred projects is estimated at EGP 247 billion in Budget FY 2023/24. More recently, the government decided to cut back public investment by 15%, with a Prime Ministerial decree cancelling any new investment projects until the end of June 2024 except for essential ones such as those in the health sector, to save around EGP 150 to 200 billion. The government has also announced an economic and social development plan with investments amounting to EGP 1.65 trillion, of which EGP 1.05 trillion borne by the government and EGP 600 billion by the private sector in FY 2023/24. It is not clear how much of it is incorporated in Budget FY 2023/24. The envisaged expenditure should be subjected to a thorough review and scaled back if found inefficient (see below).

The government has underlined that it aims to safeguard spending in key social areas such as health and education. In the initial FY 2023/24 budget, EGP 397 billion was allocated to public health services, a 30.4% increase from FY 2022/23, and EGP 591.9 billion to education, a 24.3% increase.

2.3. Restoring public finance sustainability

To keep public debt on a sustainable path, considerable efforts are needed to improve the budget balance and debt management. The government is undertaking a series of reforms to increase tax collection and strengthen public financial management. Following up on the plans to contain public investment, long-term spending and infrastructure needs should be properly evaluated and determined, while concentrating resources on priority areas such as social benefits targeted to the most vulnerable, health and education (Table 2.6). Egypt faces large fiscal challenges but lacks a comprehensive and credible consolidation strategy.

Table 2.6. Illustrative impact of fiscal policy recommendations

|

Recommendation |

Estimated impact on fiscal balance (% of GDP) |

|---|---|

|

Reduction in public investment to early-2010s levels |

+3.1 |

|

Reduction in energy subsidies |

+0.7 |

|

Reduction in food subsidies |

+0.7 |

|

Expansion of the targeted cash-transfer programmes (Takaful and Karama) |

-0.4 |

|

Increase in health spending to the MENA average |

-1.5 |

|

Increase in education spending to the MENA average |

-1.8 |

|

Steepening progressivity in personal income tax - Increasing the tax exemption threshold - Reducing the threshold at which the highest rate applies |

-0.2 +0.1 |

|

Resulting change in primary revenue |

-0.1 |

|

Resulting change in primary expenditure |

+0.9 |

|

Resulting change in primary balance |

+0.8 |

2.3.1. Debt sustainability is at risk

Central government debt is estimated to have reached 95.7% of GDP at the end of FY 2022/23. The share of external debt has also increased to 40.3% of GDP by Q4 FY 2022/23, up from 32.6% at the end of FY2020/21. Moreover, the share of short-term external debt has increased to 17.1% of GDP in Q4 FY 2022/23 from 9.9% at the end of FY2020/21, reflecting difficult funding conditions. The share of central government debt denominated in foreign currency reached 25.9% at the end of 2022. The burden of liabilities denominated in foreign currency is raised by currency depreciation. A high share of short-term debt raises refinancing risks amidst a worsening sovereign credit outlook.

Under the 2022 agreement with the IMF, general government debt was to be reduced to 78% of GDP by the end of the IMF programme, in FY 2026/27. This corresponded to the objectives in the 2020 Medium-Term Debt Strategy, which aimed at reducing central government debt to 80% of GDP by 2024 (extended to the end of FY2025/26 due to the COVID-19 crisis). Under the Medium-Term Debt Strategy, the government sought to ensure timely funding for the government’s financing needs, meet requirements and payment obligations at low cost, develop the domestic debt market, and smooth the redemption profile by extending the debt maturity profile and increasing the share of tradable debt.

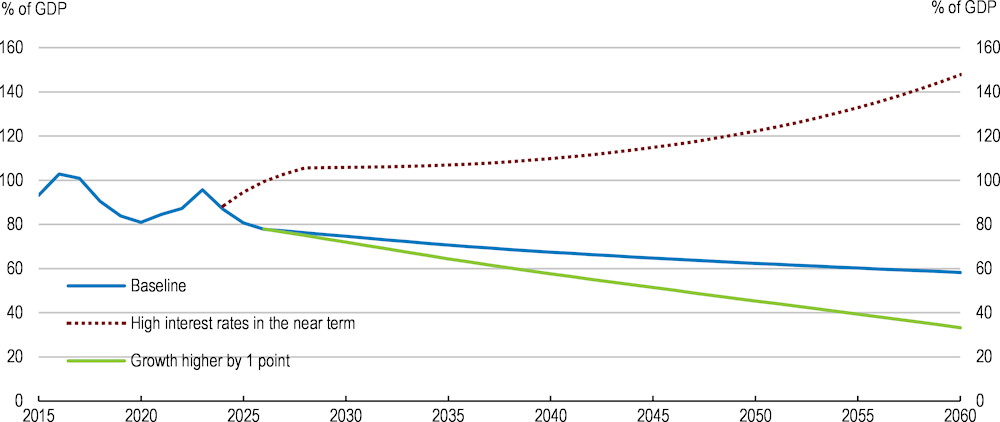

OECD simulations suggest that the debt path may be sustainable but is surrounded by large risks (Figure 2.17). They assume that the government will maintain a primary surplus of 1.6% of GDP, taking account of historical data and rising old-age related spending pressures. Even on the arguably optimistic assumption of a sustained sizeable primary surplus, the reduction of the debt ratio would be slow due to high interest rate payments. Importantly, the baseline also assumes that interest payments will normalise relatively quickly from their currently very high level, which requires investor confidence to be restored. If instead interest rates were to remain at their recent level for some time, debt would be much higher (Figure 2.17).

Figure 2.17. Debt sustainability is particularly sensitive to interest rates

Central government debt, as a percentage of GDP

Note: The baseline scenario assumes a primary surplus of 1.6% of GDP; real GDP grows at its potential growth rate; the interest rate is set at its estimated neutral level plus a term premium of 0.5 percentage point and fiscal risk premium of 2 basis points per percentage point of gross government debt/GDP ratio in excess of 75%. The "high interest rates" scenario assumes that the interest rate remains at the current level for three more years before it goes back to the level calculated according to the above-mentioned method. The “higher growth” scenario assumes that GDP growth remains higher by 1 percentage point after the projection horizon in the OECD Economic Outlook November 2023.

Source: Update of the OECD Economic Outlook November 2023; OECD calculation.

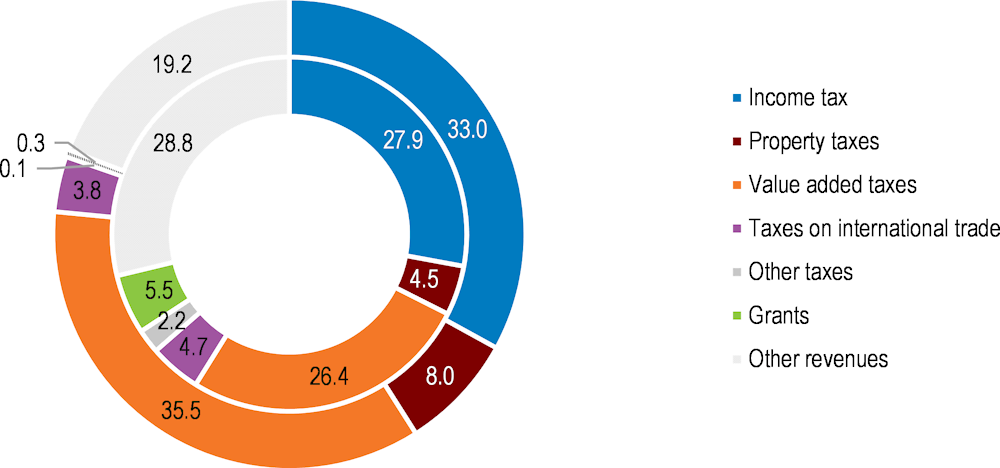

2.3.2. Tax collection should be enhanced

Central government revenue as a share of GDP is low in Egypt and the ratio fell from 19.0% in FY 2014/15 to 17.0% in FY 2021/22. The decline was largely due to non-tax revenue (Figure 2.18), which was mostly driven by property income, in particular, dividends from the Egyptian General Petroleum Corporation, the CBE and the Suez Canal. The overall low revenue-to-GDP ratio can be explained by a narrow tax base because of tax exemptions, low tax compliance and high informality (Chapter 4).

The authorities are implementing the Medium-Term Revenue Strategy (MTRS) to increase tax revenue by broadening the tax base and enhancing tax collection. The MTRS is a wide-ranging policy agenda, comprising tax policy, legislative and administrative reforms to help finance the government’s objectives with a specific medium-term revenue target. The government aims to raise the tax-to-GDP ratio by at least 2 percentage points over the medium term. It intends to increase this ratio by at least 0.5 percentage points already in FY2023/24 notwithstanding difficult macroeconomic conditions. In the process, the authorities will seek to raise the progressivity of the tax system, which is comparatively weak (Monsour and Zolt, 2023; Chapter 4).

Figure 2.18. Non-tax revenue has declined over the past decade

Revenue components in % of total revenue, central government FY2014/15 (inner circle) and FY 2022/23 (outer circle)

The authorities are seeking to improve tax administration, notably through automation and digitalisation. First, they introduced the unified tax procedures law in 2020, which is based on a unified tax registration number covering all types of taxes. The government introduced an electronic invoicing system in 2020, for the Egyptian Tax Authority to better monitor commercial transactions between firms including those that are not tax-registered through real-time digital invoice data, which can help reduce tax avoidance. In addition, imposing electronic payments to government agencies expands the base of taxpayers that the government monitors, which should help to reduce informal activities. The authorities aim to set up a comprehensive database (“Data Warehouse”), including both past and new data, which would help to expand the tax base and improve tax compliance. To further encourage tax compliance and business formalisation, the authorities should consider introducing presumptive tax regimes – also known as simplified tax regimes (Mas-Montserrat et al., 2023). These regimes reduce compliance costs for micro and small businesses and levy tax on a presumed tax base that intends to approximate taxable income by indirect means. The single tax payment can be a substitute for the personal (or corporate) income tax for unincorporated (or incorporated) businesses and potentially for a wider range of taxes (Chapter 4).

The collection of personal income tax has been weak, reflecting low tax coverage and poor compliance (World Bank, 2022a). The government is undertaking a reform in the personal income tax system in Budget FY 2023/24. This steepens the tax schedule by raising the highest tax rate from 25% to 27.5%. The highest tax rate applies to annual income exceeding EGP 1 200 000 (around USD 38 700, or 13.3 times estimated average wage earnings in FY 2023/24). The government initially considered reducing the threshold of the highest tax bracket to EGP 800 000, but this was not enacted. As the highest bracket remains particularly high, also in comparison with neighbouring countries, the government may consider lowering it to steepen progressivity as part of its commitments under the IMF programme (IMF, 2023a). The government plans to introduce other measures, including limiting tax deductions on interest. In the medium term, the government intends to enact a new income tax law to address existing loopholes, streamline taxes on various income categories, including capital income, capital gains and professional income, and eliminate tax exemptions by the end of the IMF programme in 2026. In the meantime, the government should continue to improve its data capacity and analysis and strengthen tax administration to get ready for tax reform.

The corporate income tax system provides multiple forms of exemptions, with an unknown amount of forgone revenues (World Bank, 2022a). The amendments to the Special Economic Zone law in 2015 and the 2017 Investment Law made some improvements, such as restricting tax holidays to firms in some special economic zones. However, preferential tax treatment remains too generous overall (Chapter 3). The government intends to reduce and streamline remaining corporate tax expenditures. It has been planning to publish an annual tax expenditure report with information on the tax revenue foregone of business tax expenditures, including tax exemptions and holidays covering firms in special economic zones and all state-owned enterprises. The government intends to update this report annually and include it in budget documentation. The government was expected to publish the first such report in April 2023, but it has not been issued yet.

Among OECD countries, Canada undertakes a tax expenditure review each year. It provides a description of each measure and of its objectives, cost estimates and projections, legal references, and historical information. As a result of such a review, the Canadian government has for instance introduced restrictions to reduce misuse of the small business tax regime by high-income households (OECD, 2018b). The OECD is currently conducting a study to improve the design of tax incentives in the corporate income tax system in Egypt (OECD, 2024a forthcoming).

The efficiency of the value-added tax (VAT) system is diminished by multiple rates and exemptions, while tax compliance has deteriorated (World Bank, 2022a). The government intends to simplify the VAT system by subjecting all goods and services other than basic foodstuffs to the standard VAT rate (IMF, 2023a). Given the challenges associated with such a measure, the government should begin by examining the feasibility of reducing the number of VAT exemptions, drawing on international good practices in applying exemptions.

The VAT system faces new challenges owing to the rise in e-commerce. Imports resulting from online sales are often either not taxed or under-taxed because of fraudulent non-declaration or undervaluation to avoid tax and duties. This widens the VAT revenue gap and creates unfair competitive conditions for domestic businesses. To address similar challenges relating to imports of services, Egypt has recently introduced a new regime, effective from June 2023, for collecting VAT on digital services and products, and other remote services, that non-resident businesses supply to consumers in Egypt. The OECD has provided comprehensive support throughout the development and implementation of this reform, which aligns with OECD international VAT standards and guidance and will have a positive impact on VAT revenues.

Property taxation is comparatively less harmful to growth and is a progressive source of revenue (Arnold et al., 2011). In Egypt there are two types of property taxation: transfer tax on sales of built real estate or land, assessed on the total disposable value of the property; and real estate tax, which is a recurrent tax levied annually on all constructed real estate units, covering land and building. The real estate tax rate is 10% of the rental value of real estate units. The rental value is determined by the Ministry of Finance, taking account of such factors as location, nature of buildings, and the economic situation of the district. It is updated every five years, which is rather infrequent during times of high inflation. The calculation of the rental value differs for residential and non-residential units. There are deductions to account for expenses incurred by the taxpayer, including maintenance costs. There are also exemptions for real estate used for production and services activities. With a view to increasing property taxation in the medium term, the government plans to streamline various exemptions and to revise its valuation model for property tax assessments before the end of the IMF programme in 2026, which is essential to ensure the effectiveness of property taxation. To enhance the efficiency of property taxation, the government plans to compile data in an electronic register using geo-coded identifiers. By making full use of digitalisation, the government can expand the tax base and facilitate compliance, for example, by identifying undisclosed properties that could be subject to property taxation.

The authorities seek to improve tax transparency, also in cooperation with the OECD and the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information (EOI) for Tax Purposes Egypt is a member of. The December 2022 amendment to the Unified Tax Procedures Law allows the disclosure of financial account information for EOI purposes with tax authorities of foreign jurisdictions with which an agreement is in place. This progress was made in the context of the implementation of the EOI on request standard, requiring the availability, access and exchange of banking information. Egypt’s peer review under this standard began in December 2022 and is still ongoing.

Furthermore, Egypt is a member of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS). Egypt will benefit from the two-pillar solution to address the tax challenges arising from the digitalisation of the economy. First, it will reallocate taxing rights over 25% of the residual profit of the largest and most profitable multi-national enterprises (MNEs) in the world. These taxing rights will be re-allocated to the jurisdictions where the customers and users of those MNEs are located. Second, it establishes a global minimum tax on the largest MNEs in the world (also known as the GloBE Rules). This will place a floor on corporate tax competition, which will ensure an MNE is subject to tax in each jurisdiction at a 15% effective minimum rate regardless of where it operates, thereby ensuring a level playing field. A further component will be the subject-to-tax rule (STTR), which will protect the right of developing countries to tax certain intra-group payments such as interest or royalties where these are subject to a nominal corporate income tax that is below the 9% minimum rate. To benefit from the minimum rate and the STTR, Egypt needs to continue to engage with the process and transpose the GloBE Rules into its domestic law. The OECD is assisting the Egyptian authorities on international tax issues through capacity building, implementation of the BEPS package, support for the implementation of the two-pillar solution, and audit support. The GloBE Rules will also affect the use of tax incentives in the corporate income tax system (see above).

2.3.3. Prioritising and rationalising spending

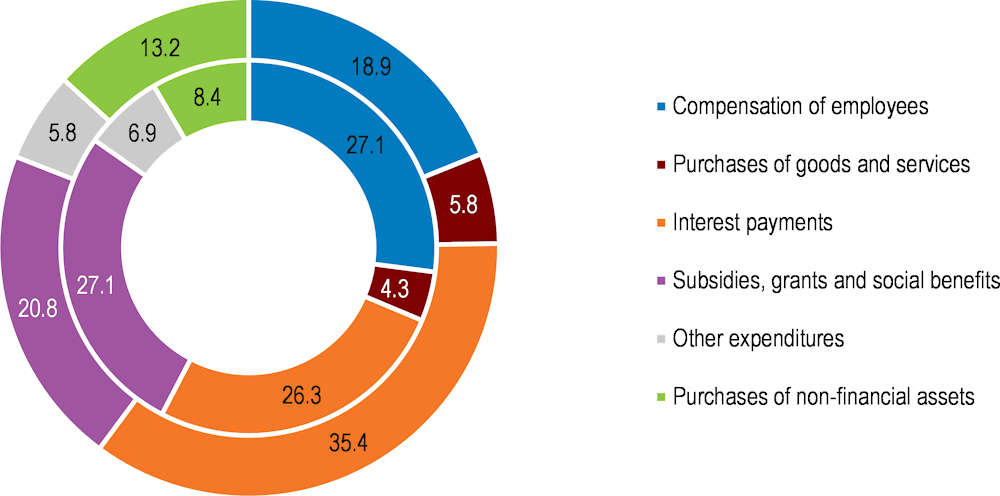

Central government expenditure as a share of GDP declined over the past years from 30.0% in FY 2014/15 to 23.1% in FY 2021/22. At the same time, the composition of spending has substantially changed (Figure 2.19), driven, among others, by a substantial increase in the share of interest payments and public investment.

Over the past decade, significant fiscal reforms have been undertaken, notably the reduction in energy subsidies and in the public sector wage bill. Energy subsidies, which accounted for 10.1% of total expenditure in FY 2014/15, have been reduced to 5.8% in FY 2022/23 (Table 2.7). This contrasts with food subsidies, which have remained basically constant as a share of total expenditure at around 5.5%. The share of compensation of employees has also declined significantly over the same period, from 27.1% to 18.9%, largely resulting from the cap on the number of public sector employees in place since the early 2010s. The government is extending its efforts to reduce administration costs. Under the Administration Reform Plan (see below), it is strengthening strategic planning coordination, restructuring the national authorities and reforming recruitment.

Figure 2.19. The spending mix has significantly changed

Spending components in % of total expenditure, central government FY2014/15 (inner circle) and FY 2022/23 (outer circle)

Table 2.7. The spending mix has changed over the past decade

Subcomponents of the category “subsidies, grants, and social benefits”, in % of total expenditure

|

|

FY 2016/17 |

FY 2017/18 |

FY 2018/19 |

FY 2019/20 |

FY 2020/21 |

FY 2021/22 |

FY 2022/23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Subsidies, grants, and social benefits |

26.8 |

26.5 |

21.0 |

16.0 |

16.7 |

18.8 |

20.8 |

|

of which: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Food |

4.6 |

6.5 |

6.4 |

5.6 |

5.3 |

5.3 |

5.6 |

|

Energy |

11.1 |

9.7 |

6.2 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

3.3 |

5.8 |

|

Contributions to pension funds |

4.4 |

4.2 |

3.5 |

3.8 |

6.3 |

6.6 |

5.8 |

|

Social solidarity pension (including Takaful and Karama) |

0.7 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

|

Housing of low-income groups |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

Source: Ministry of Finance; OECD calculation.

The government intends to reform energy subsidies, extending its previous efforts. These subsidies had been reduced to 0.3% of GDP by FY 2020/21, but rose again to 1.2% of GDP in FY 2022/23 due to the jump in energy prices in international markets (see above). The government aims to fully reflect global price movements in domestic energy prices (Box 2.2). This will help solidify the progress made thus far, while protecting the budget and contributing to achieving the government’s environmental objectives. The government intends to increase transparency in pricing decisions and payment arrears for the Egyptian General Petroleum Corporation, the energy producer.

In parallel, the government plans to extend social benefits targeted to vulnerable people. While energy subsidies have decreased, social benefit programmes targeted to those most in need have been strengthened. To wit, the introduction and expansion of the Takaful and Karama programmes, which replaced similar but less well targeted benefits (Chapter 4). By changing the spending mix, these programmes should be financed further and developed to reach all eligible households, which would cost 0.4% of GDP (World Bank, 2022a). The government has expanded the coverage of the social registry to 11.4 million households by the end of 2023. Out of these, 4.7 million receive cash transfers. The social registry should continue to be expanded, which will help identify those who are eligible for these programmes. The government intends to introduce targeted approaches also in several other social protection schemes. In this respect, food subsidy programmes, which currently reach the vast majority of the population (Box 2.1), can be made more targeted to poor people. Middle-class households, meanwhile, will benefit from the increase in the threshold for the personal income tax exemption.

Fiscal pressures related to old-age spending are expected to increase. The old age dependency ratio (in terms of those aged 65 years or above as a ratio to the working age population) will rise from 8.8% in 2020 to 10.2% in 2030 and 14.8% in 2050. Law 148/2019 on Social Insurance improved the sustainability of the pension system. Following this reform, public expenditure on pensions is projected to decline from 4% of GDP currently to around 3% in the mid-2030s and to remain at this level thereafter (World Bank, 2022a). This reflects both the extension of the retirement age (from 60 years old, by one year every two years from 2032, to 65 by 2040) and a reduction in the replacement rate. The latter is projected to decline gradually but substantially from approximately 70% currently to 30% over the five decades to the 2070s. This decline is due to the change in reference wages (whole career wages instead of wages during the final two years) and indexation only to inflation. The expected low pension adequacy may require the government to revisit its pension calculation method. The social insurance scheme ensures minimum pensions (“social insurance pensions”), currently at EGP 1 300 per month, for those whose contribution falls short of guaranteeing sufficient pensions under certain eligibility conditions. The need for such minimum guarantees may increase due to increasing periods of unemployment or inactivity among workers (Chapter 4).

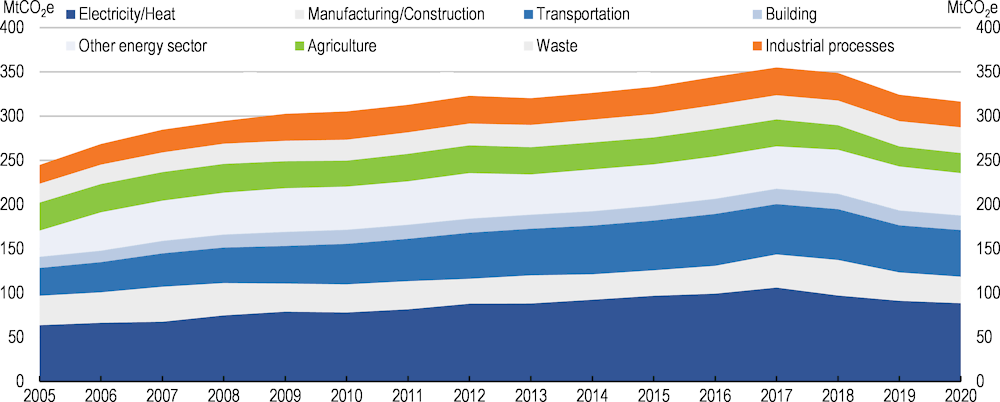

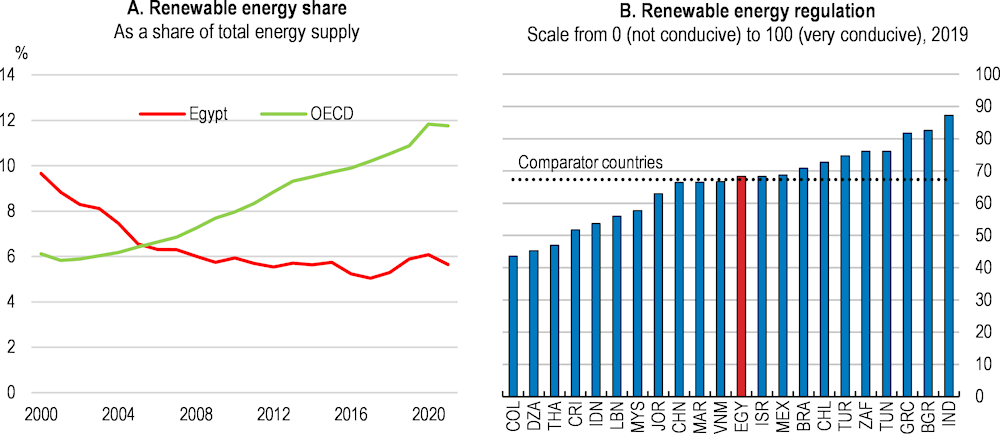

Public spending on health is currently low, at 6% of total government expenditure over the five years to FY2021/22, but is expected to rise as the population expands and ages. Life expectancy in Egypt was 70 years in 2021, against an average of 76 years for neighbouring countries (as defined in Box 1.3). The public share in total health spending is low, at approximately 27%, well below the average of the MENA countries (World Bank, 2022a). This is reflected in low health insurance coverage and a high co-payment rate (the share of medical costs covered by patients themselves) of 60% (World Bank, 2022a). The government has been implementing the Universal Health Insurance System (UHIS), introduced by Law 2/2018. The UHIS covers individuals outside the social insurance system and provides exemptions for insurance premiums. Under this law, universal health coverage will be completed within 15 years by gradually increasing the number of regions where it applies. It takes a gradual approach as its rollout entails considerable investment in public healthcare facilities. The implementation of the UHIS can be accelerated by prioritising public investment in healthcare facilities.