This chapter examines capacities for evidence-informed policy-making in the state of Nuevo Léon. It examines the role of the council in the policy advisory system in Nuevo León and suggests ways in which it may better contribute to shaping the state policy agenda on strategic issues. It offers concrete approaches to strengthening the supply of evidence in Nuevo León by suggesting the council encourage the adoption of knowledge brokering methods to promote the relevance, impact and use of advice in the state public administration, for instance for making use of evidence synthesis methods. Finally, the report concludes that enhancing Nuevo León’s capacity for an evidence informed approach will require expanding the skills and infrastructure to generate and use evidence.

Monitoring and Evaluating the Strategic Plan of Nuevo León 2015-2030

5. Promoting Evidence-Informed Policy-Making in Nuevo León

Abstract

Introduction

Evidence-informed policy-making can be defined as a process whereby multiple sources of information, including statistics, data and the best available research evidence and evaluations, are consulted before making a decision to plan, implement, and (where relevant) alter public policies and programmes (OECD, 2020[1]).

Increasing governments’ capacity for an evidence informed approach to policy-making is a critical part of fostering good public governance to achieve broad societal goals, such as promoting sustainable development or improving well-being. The goal of evidence-informed policy-making is to enable agile and responsive governments, which are well equipped to address complex and at times “wicked” policy challenges.

Despite the potential for policies to be based on evidence, an effective connection between the supply and the demand for evidence in the policy making process often remains elusive. Many governments lack the necessary infrastructure to build such effective connections. In practice, policymakers also tend to have limited skills and capacities (time, access, incentives) to generate and/or use scientific research and statistical data.

Moreover, in a context in which justifying the use of public resources with accurate evidence is becoming increasingly important, the way in which this evidence is gathered, applied and integrated into decision-making processes is a key element that can determine the nature and impact of a policy (Parkhurst, 2017[2]). The consultation of multiple sources of information and actors before the implementation of a public policy, programme or public service has become essential (OECD, 2020[1]). Indeed, the involvement of different stakeholders in policy-making processes helps to ensure that the relevance and context of emergent public policies is taken into consideration.

As a result, many OECD countries have set up policy advisory systems to support evidence informed policy making with the best possible evidence. The institutional set-up of these policy advisory bodies generally depends on the countries’ institutional history, administrative traditions and the basic set-up of their governmental system (OECD, 2017[3]). These bodies can be very diverse in terms of organisational structures, mandates or functions in the policy cycle (OECD, 2017[3]). They can take the form of advisory councils or strategic planning councils, with either sectoral or horizontal responsibility, bodies operating at arms’ length from the government but still within the public sphere at large, or organisations within government. In many ways, the functions of the Nuevo Léon council can be analysed within this framework of policy advisory bodies.

In this context, the report highlights good practices for enhancing capacities for evidence-informed policy-making. Firstly, it examines the role of the council in the policy advisory system in Nuevo León and suggests ways in which it may better contribute to shaping the state policy agenda on strategic issues. Second, the report looks at the supply side of evidence-informed policy-making, by suggesting that the council promote the adoption of knowledge brokering methods to promote the relevance, impact and use of advice in the state public administration. Finally, the report concludes that enhancing Nuevo Léon’s capacity for an evidence informed approach will require expanding the skills for understanding, obtaining, interrogating and assessing, using and applying evidence, as well as establishing the appropriate infrastructure to generate and use evidence that stands the test of time.

Setting up an advisory system that meets the needs of government

Many OECD countries have set up a system of actors and institutions aimed at providing credible advice to government and at facilitating the capacity to implement reforms. Due to the pace of technological, environmental and cultural developments, policy makers are continuously called to find new solutions to complex issues. One way in which governments have sought to increase their strategic capacities is by relying on networks of actors, within and outside of government, that provide evidence and policy advice – the so-called policy advisory systems.

Indeed, policy advisory systems, understood as “an interlocking set of advisory actors with a particular configuration that provides information, knowledge and recommendations for actions to policymakers” (Craft and Halligan, 2015[4]), do not base their advice to governments solely on objective facts and evidence, but also present new and alternative points of view (Hoppe, 1999[5]). In this sense, policy advisory systems combine the power dimension of politics and the knowledge dimension of policies (Hustedt, 2019[6]). Advisory systems contribute to wider evidence-informed policy-making approaches in that they provide tailored evidence to governments.

Most OECD countries have a policy advisory system of some sort, even if their specific institutional set-ups are generally the result of countries’ institutional history, administrative traditions and the basic set-up of their governmental system (OECD, 2017[3]). It is possible, however, to distinguish three broad types of systems:

‘Westminster countries’, which include Great Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, share a common administrative tradition. In the ‘Westminster model’, there are often chief scientific advisors operating within governments, accompanied by chief medical officers, chief statisticians or chief economists. Still, in many of these countries there is a practice of setting up “royal commissions”, as ad hoc advisory bodies on specific topics. More permanent advisory bodies exist, such as the Productivity Commission in Australia and its newly set up cousin in New Zealand, or the Australian Institute for Health and Welfare in Australia.

‘Nordic countries’ such as Sweden and Norway, where governance systems are characterised by the importance of agencies, rely on decentralised bodies. Sweden has a tradition of setting up “Commissions of Inquiry” to address significant issues. In Norway, the government has appointed the creation of external and temporary Norwegian Official Commissions, to examine major policy problems and provide recommendations. Their relevance is such that on average, around 30 commissions were appointed each year during 1967-2013 (Christensen and Serrano Velarde, 2019[7]).

‘Continental European countries’ such as Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany, and to a lesser extent France, are also setting up bodies that either reflect a variety of interests or tripartite arrangements with the government, the social partners (including trade unions and business representatives), and civil society. The role of these bodies is to help achieve consensus on major options for reform. Still, there are also significant “expert organisations”, such as the Central Plan Bureau, or the Social Cultural Plan Bureau/Netherlands Institute for Social Research, or bodies such as the German Council of Economic Experts that are driven by expertise and operate at arms’ length from government.

Policy advisory bodies can be very diverse in terms of organisational structures, mandates or functions in the policy cycle (OECD, 2017[3]). Advisory bodies can take various forms, such as advisory councils, strategic planning councils (like the Nuevo Léon council), commissions of inquiry, foresight units, special advisors, think tanks and many other bodies, all of which provide knowledge and strategic advice to governments (Bressers, 2015[8]) (Blum and Schubert, 2013[9])

Despite this strong diversity, an OECD report (2017[3]) showed that policy advisory bodies share some common features. These include the duration of their mandate, position towards the government and thematic focus.

Duration of the mandate: While the duration of the mandate of permanent advisory bodies (such as councils and research institutes) is not predefined, ad hoc advisory bodies are set up to examine an issue for a specified period and are dissolved after one to two years, when their mission ends. Permanent advisory bodies can be either councils or research institutes, while ad hoc advisory bodies can take on diverse shapes, from cabinet committees to political strategists or community organisations.

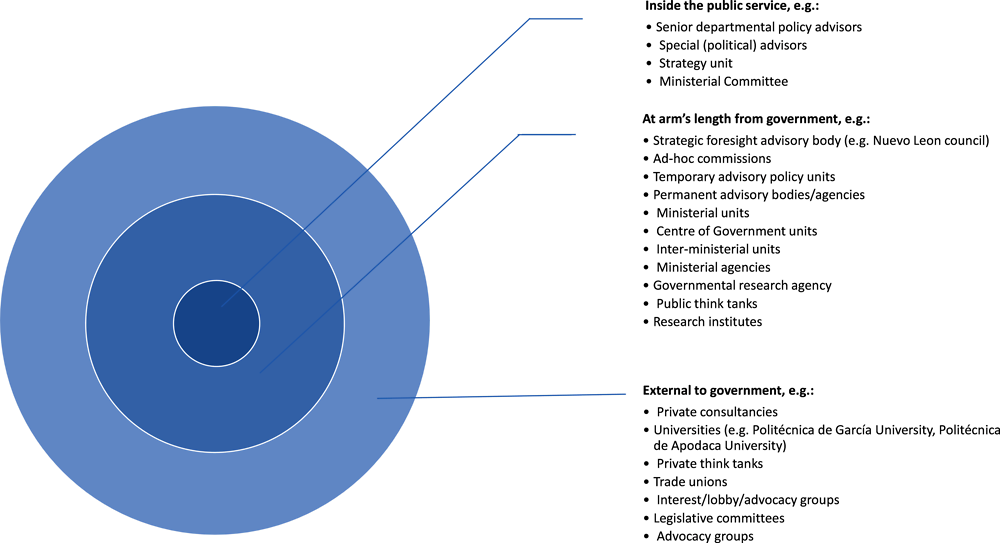

Position towards the government: Advisory bodies typically have three different degrees of legal and administrative autonomy relative to the government (see Figure 5.1).

They can be inside the government;

They can act at arm’s length from the government, which means that they are not entirely legally independent of the government but have some administrative or technical autonomy– such as the Nuevo Léon council;

They can act outside of the government, meaning that they have full legal autonomy in providing advice to government (OECD, 2017[3]).

Figure 5.1. Advisory bodies’ position towards government

Source: Adapted from (OECD, 2017[3]) Policy Advisory Systems: Supporting Good Governance and Sound Public Decision Making, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264283664-en, Van Twist, M.J.W. et al. (2015), “Strengthening (the institutional setting) of strategic advice”, OECD seminar “Towards a Public Governance Toolkit for Policymaking: ‘What Works and Why’”, 22 April 2015, Paris; Halligan, J. (1995), “Policy advice and the public sector”, in Peters, G. and D.T. Savoie (eds.), Governance in a Changing Environment, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, pp. 138– 172.

The thematic focus of advisory bodies is variable. Certain advisory bodies have a very broad thematic focus, such as the German Council of Economic Experts, which advises German policy makers on questions of economic policy. Others have a very specific policy area; this includes the Lithuanian Council for the Affairs of the Disabled, which organises and coordinates measures for social integration of people with disabilities. Specific advisory bodies generally have a high level of technical expertise (OECD, 2017[3]).

Nuevo León has created an advisory system mostly centred around the council

In OECD countries, governments have relied on an increasing amount of actors to provide policy advice. In particular, actors outside of the government influencing policy decision-making processes have increased and are seen as beneficial to the advisory system overall, as they make policy advice more democratic and responsive to public concerns. In the European Commission, for example, the Scientific Advice Mechanism (SAM) sought to organise the advisory system surrounding scientific advice. The mechanism stipulated the role and functions of each actor in the process, in order to standardise advice coming from a wide range of different bodies, such as the European and national academies and the wider scientific community (see Box 5.1).

However, a distinction has to be made depending on the size of the organisation or the country. Nuevo Leon is a state in a very large federation, but by its size is similar to many relatively small European countries, such as Denmark, Ireland or Norway. Any options for setting up an advisory system should be adapted to the size of its government apparatus, as it conditions the availability and diversity of expertise that is available. In Mexico, the capacity to rely on expert advice from bodies operating either at federal level, or with prime academic expertise, such as CIDE, also has to be taken into account. Finally, as further explored in chapter 1, the relatively small fiscal space in Mexican states can affect Nuevo León’s capacity to rely on expert advice.

Box 5.1. The Scientific Advice Mechanism of the European Union

The Scientific Advice Mechanism (SAM) supported the Commissioner for Research, Science and Innovation of the European Union with independent scientific advice for its policy-making activities.

The SAM was composed of: the Group of Chief Scientific Advisors, an expert group of the European Commission that provides independent scientific advice to the College of European Commissioners to inform their decision-making; the Science Advice for policy by European Academies (SAPEA), which brings together outstanding knowledge and expertise of fellows from over 100 academies and Learned Societies in over 40 countries across Europe; and the SAM Secretariat (within the Commission).

In order to ensure the policy relevance and uptake of the scientific evidence, the SAM worked closely with policy-makers at the highest-level. This allowed them to address the broader needs identified by the policy-makers (top-down) and to bring issues that were identified by the scientific world to the attention of the decision-takers (bottom-up). Specifically, the SAM produced evidence to support policy-making using the following steps:

1. Identification of a subject for scientific advice: The Commission consults the Group of Chief Scientific Advisors on a policy field and defines the timespan in which independent scientific advice is required.

2. Definition of the question: The Commissioner for Research, Science and Innovation formulates the request for advice, which defines the question to be addressed by the Group of Chief Scientific Advisors, following a consultation request originating in the Commission.

3. Evidence gathering: The Group of Chief Scientific Advisors appoints a lead member and sets up a coordination group, who ask the Commission (the SAM Secretariat) to allocate responsibility for the evidence gathering to SAPEA.

4. Drafting the advice: Lead member/coordination group drafts the advice of the Group of Chief Scientific Advisors. The SAM Secretariat assists the preparation and editing of the advice.

5. Adopting and communicating the advice: The Chair of the Group of Chief Scientific Advisors sends the advice to the Commissioner for Research, Science and Innovation who will transmit it to the other members of the commission, including the President.

Source : Adapted from European Commission (2019[10]).

In the state of Nuevo León, the council really stands out as the main actor of the advisory system available at the state level. The council serves as a multi-stakeholder platform (civil, academia, private sector, and government) to promote the economic, social and political development of the state through strategic planning, and monitoring and evaluation of the Strategic and State Plan. In that sense, it acts as an advisory body because the council has the mandate to collect data needed for future analyses, and to address both middle and long-term issues (article 9 of the Strategic Planning Law). Moreover, its thematic focus is broad, giving it large visibility as an advisory body of the government. Besides the council, a number of other actors are also collecting evidence and advice in the state, including some very active non-governmental organisations that are often focused on specific issues, as well as world-class experts whose advice is available through the academic institutions of the state (e.g. Technological Institute of Monterrey - Instituto Tecnológico de Monterrey and the Autonomous University of Nuevo León - Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León).

With regard to the bodies that compose the executive of Nuevo León, there are other actors that could be considered as advisory bodies, since they support the executive in the exercise of its functions by supplying information and/or advice. For instance, the Organic Law of Public Administration from the State of Nuevo Leon (Ley orgánica de la administración pública para el estado de Nuevo León) considers the creation of citizen participation bodies (consejos de participación ciudadana) in its articles 41 through 46 (see Box 5.2). These councils serve to contribute legitimacy in agenda shaping, since they consult stakeholders in different sectors (academia, private, social, and trade union) about a particular topic; and disseminate priority programmes (Secretary of the State, 2009[11]). Nonetheless, the thematic focus of these bodies is rather limited to a specific policy issue. For instance, the State Youth Institute (Instituto Estatal de la Juventud) has a citizen council that monitors and promotes policies and actions focused on youth (State of Nuevo Leon, 2019[12]).

Box 5.2. Citizen participation councils in Nuevo Léon

Citizen participation councils are consultative and multidisciplinary bodies (with representatives from the social, private and academic sectors) that analyse, review, recommend and evaluate instruments and actions that fall under the responsibility of the executive. Article 41 of the Organic Law of Public Administration from the State of Nuevo León stipulates that the executive can constitute these councils to provide advice (“consult and propose”) on matters of public interest or for strategic planning purposes.

Other than the state governor, who acts as honorary president, the councils are composed of a president (representing civil society), an executive secretary (often times a senior civil servant of the secretariat that works on these issues), a technical secretary and advisers. Each member has a vote in the council’s sessions (article 45).

Citizen Participation Councils exist in the following areas (article 46):

Justice;

Public security;

Education;

Health;

Economic Development;

Social development;

Jobs; and

Sustainable development.

Source: Source: Adapted from the State of Nuevo Leon (Secretary of the State, 2009[11]), Organic Law of Public Administration from the State of Nuevo Leon, [Ley orgánica de la administración pública para el estado de Nuevo León)

As a result, it appears that the state public administration may have at its disposal a wide range of advice to draw from. In the future, the council could support the state public administration in mapping think thanks, research institutes, etc., working on policy advice to determine technical gaps in the advisory system and to increase representativeness in the evidence supply.

Currently, the functions of the council are blurred across a range of functions

According to the OECD Survey on Policy Advisory Systems (2017[3]), advisory bodies have a wide range of functions in the policy-making process, such as (OECD, 2017[3]):

Shaping the agenda: advisory bodies can seek to draw attention to certain topics and help them gain importance in the political agenda. During this phase, public research institutions and planning/assessment advisory bodies have a particularly strong role, while ‘foresight advisory bodies’ and public think tanks are the ones with the least significant role.

In the policy development phase, advisory bodies point to new policy options, create evidence, and help create legitimacy for choosing particular policy options. During this phase, ad hoc advisory bodies and public research institutions have a particularly strong role.

In the implementation phase, all bodies tend to be relatively active with the exception of public think tanks, foresight bodies and planning/assessment advisory bodies. Public research institutions and ministerial advisors have a particularly strong role during this phase.

In the evaluation phase, ad hoc advisory bodies, as well as permanent advisory bodies with a secretariat and public research institutions have a relatively important role. Planning/assessment advisory bodies play a specific role too, as they have the explicit task to ‘assess’ governments’ policies. On the contrary, the role of foresight advisory bodies, public think tanks and permanent advisory bodies without a secretariat is more limited.

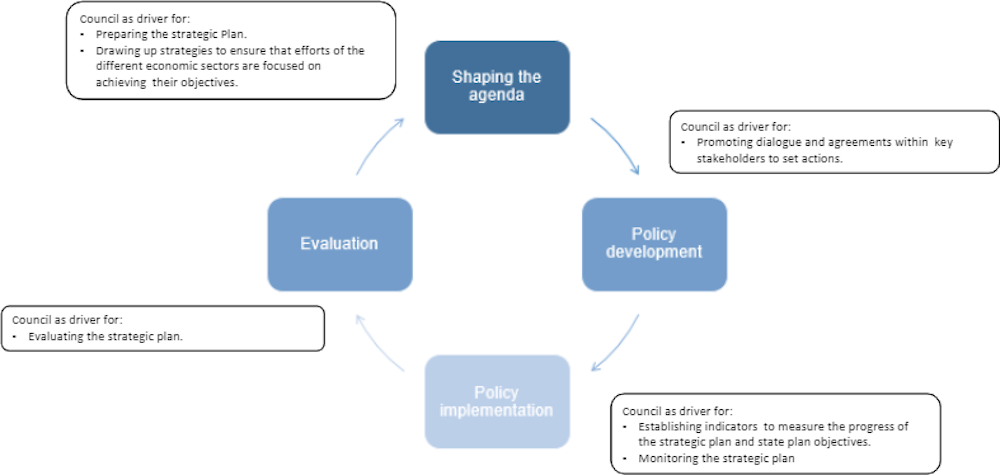

In Nuevo León, the council plays a role in each of the stages of the policy cycle described above. Figure 5.2 presents in more detail such roles.

Figure 5.2. The policy cycle and the role of the Council of Nuevo León

According to the Strategic Planning Law, the council is responsible, inter alia, for the elaboration of the Plan, for defining strategies to include society in the efforts for its implementation, for defining criteria for the elaboration of indicators (article 9), as well as for monitoring and evaluating the Plan’s results (article 19). As such, the council serves as a multi-stakeholder forum for policy development through strategic planning, for monitoring policy implementation, and for evaluation.

Furthermore, the council offers a space to bring together the government, the private sector, academia and the civil society to discuss new initiatives that were not explicitly set out in the strategic plan. This is the case of the “Hambre Cero” initiative (see Box 1.5 in chapter 1), an inter-institutional effort derived from the 2030 strategic plan to eradicate extreme food poverty and food waste in the state. In these functions, the council is contributing to shaping the policy agenda.

Moreover, the council plays a major role in monitoring the Strategic Plan (See chapter 3). In addition, as discussed in chapter 1, the council has also been involved in policy implementation, for instance by developing new initiatives, such as “Hambre Cero Nuevo León”, to implement the plan. Finally, the council has a clear mandate to evaluate priority programme in the Strategic and State Plan (article 19, Strategic plan law).

Nevertheless, exercising these different roles along the policy cycle has weakened the impact of the council’s advice. The fact that the council is playing a role in each phase of the policy cycle has created political tensions with the state public administration and resulted in the council losing its strategic focus on the planning function– a function which is also intrinsically linked to foresight and evaluation. These tensions can also be explained by the incompatibility of these functions: while effective monitoring requires strong political influence and commitment (for instance, to identify implementation barriers and to tangle them), evaluations benefit from independence and technical legitimacy.

Defining and separating the respective roles of the council and the public administration will help to boost the efficiency of strategic planning. As recommended in chapter 1, the council should strengthen its role in shaping the policy agenda and strategic planning to move away from monitoring and implementing policies.

Nuevo León council should focus on providing evidence and evaluation, as well as shaping the policy agenda upstream

As a relatively autonomous body that benefits from representing the views of a wide range of stakeholders, and as a body operating at arm’s length from government, the council is best placed to provide credible evidence and evaluation, and in doing so, to contribute to shaping the policy agenda. Indeed, evidence does not only relate to statistical data but encompasses all research that seeks to understand why some policies or strategies work and why others do not (policy evaluation). Along with evaluation, it can therefore support decisions about policy choices based on facts and inform the policy agenda.

Although there is no strict definition of what effective advice is, OECD research suggests that it can be broken down into two dimensions: ‘relevance’ and ‘impact’ (OECD, 2017[3]). This section mainly explores the first of these factors.

Firstly, relevant advice is multifactorial, meaning that it depends on a multitude of interdependent factors, including the following (Cash et al., 2003[13]):

Timeliness of advisory knowledge for policy-makers

Representativeness, which denotes whether knowledge is produced in an unbiased way by considering all relevant interests

Credibility, which refers to whether the production of knowledge follows established standards of evidence (whether it is scientifically robust)

Timeliness of advice

In the Strategic Planning Law the council defines to what extent its advice is made public. However, this formal advice is published annually (even though there are regular debates in the commissions) and therefore is disconnected from the decision-making processes. The council is currently bound by law to produce a yearly report on the results of the Strategic Plan. This could restrict its role in public debates of interest and decrease the influence of its advice in the decision making process.

Instead, the council could anticipate a calendar with the timing of its publications. For instance, the French council France Stratégie sets up an annual research schedule, which gives direction to its research and focuses the generation of knowledge on very specific issues throughout the year (see Box 5.3).

Box 5.3. Increasing the timeliness of an advice: the case of France Stratégie

At the government’s request, or on its own initiative, France Stratégie carries out studies and evaluations of public policies, in order to fulfil the task it was assigned when it was established by the Prime Minister in 2013, namely “fostering dialogue and shared analysis and scenarios”.

In 2019, France Stratégie adopted a research plan focused on six main themes: achieving sustainable development, adapting the productivity system to new challenges, reinforcing public policy efficiency, decreasing structural unemployment, anticipating the future organisation of work, and moving towards diversified and harmonious development in local territories. This annual research plan is also inscribed in a ten-year research agenda for 2017-2027, which sets up projects for the next decade.

Source: (France Stratégie, 2018[14])

Similarly, to this practice, and in line with the recommendations in chapter 4, the council could elaborate a research or evaluation plan, to identify the timing of its reports throughout the year and to anticipate how these would coincide with public debates and events. In order to do so, it could seek input from the state public administration, to identify key areas of interest. This plan would therefore clearly distinguish between the evaluations mandated by the government and the evaluations done on the initiative of the council. As explored in chapter 4, this distinction may require different follow-up mechanisms to ensure the discussion of the evaluations’ recommendations.

Representativeness in decision-making

The private sector is strongly represented in the council, which also reflects the ambitions of the council at its inception. The council is composed of 16 members and a technical secretary. Membership includes six citizen councillors, three heads of universities (two are private and one is public), six government members, one member from the federal government, and the executive president, who is chosen from the citizen councillors. Thus, more than half of the members are from the private sector or economic/social organisations. Although commissions may invite representatives of federal agencies and municipal authorities to participate in their work (article 11), they only have voice in the council (article 7 from the Strategic Planning Law regulation).

As discussed in chapter 1, there is a significant perception among stakeholders that the council’s representativeness remains unbalanced across sectors of civil society. In particular, citizens appear to have limited voice/influence, even if NGOs participate in some of the councils’ commissions. Additionally, there are demands to expand the advisory role of universities to better leverage the council’s technical capacities and skills. Lessons learned show that in order to provide credible and tailored advice, the composition of a committee, board, or commission needs to ensure that membership is neutral; provides high quality expertise; and, depending on the nature of the issues discussed, represents the age, gender, geographic, and cultural diversity of the community (Government of Canada, 2011[15]; Quad Cities Community Foundation, 2018[16]). In this regard, the council could consider giving a vote and more representativeness to other institutions working with minorities, vulnerable communities and municipalities to balance powers across different types of actors in order to level the play field. Such public deliberations could increase government trust, and strengthen government integrity and accountability. For instance, the Youth Institute (DJI) from Germany regulates the composition of its members to ensure that they come from various horizons and cover different perspectives (see further details in Box 5.4). In Nuevo León, this could require updating the guidelines of the Strategic Planning Law.

Box 5.4. Ensuring qualified board membership : the example of the Youth Institute in Germany

The Youth Institute in Germany (Deutsches JugendInstitut, DJI) is a social science research institute specialised in children and young peoples’ life situations. It describes itself as ‘an interface between science, politics and professional practice’, with members coming from the fields of politics, sciences and from youth and family welfare institutions. In order to ensure that its members come from various horizons, the DJI has clear guidance for the composition of its members, for each of its three bodies:

The General Assembly comprises members appointed by the highest federal youth welfare authorities, by family associations and by selected professional organisations;

The Board of Trustees consists of representatives of federal ministries, one representative of each of the DJI home state and the higher regional youth welfare services; 5 members elected by the General Assembly, and one staff representative.

The Scientific Advisory Council consists of 19 experts from both Germany and abroad, with the composition reflecting the scientific disciplines and topic areas in which the DJI is engaged.

Source : Adapted from Youth Institute official website (Institute, 2020[17]), https://www.dji.de/en/about-us.html (accessed 03 February 2020)

Distribution of competencies and skills among members

According to article 7 of the Strategic Planning Law, the citizen councillors are chosen because of their economic and social knowledge of the state and public reputation. However, the law does not establish competence requirements for the council’s members. While there is no strict requirement, and it is also important that commissions represent a range of relevant interests, it would also be important to ensure that a share of the members be appointed with regard to their expertise in each thematic area, to increase the authority of the council’s advice. For example, the Independent Technical Council for the Evaluation of Public Policies of Jalisco (“Evalúa Jalisco”) stipulates in its statutes that members must have technical expertise in monitoring and evaluation. In addition, this council is composed, amongst other actors, of experts coming from state universities (6), an international research institute (1) and the national council for policy evaluation (CONEVAL, 1 member). All these members have a vote and voice on the board.

Moreover, in order to enhance the credibility of its advice, the council may benefit from improving its decision-making processes. According to article 6 of the Strategic Planning Law regulations, the agreements of the council are adopted by consensus. While making decisions by consensus may ensure greater uptake of the evidence, the lack of clarification of the decision-making process has resulted in several decisions being adopted without being informed by clear evidence (evaluations, systematic reviews, etc.). In this regard, Nuevo León could further define the council’s decision-making process to ensure that any advice produced is based on:

Evidence collected and presented by the council on the topic under discussion, which should include disclosing the underlying methodology of the evidence, its assumptions and limitations.

Clear procedures for decision-making, including requirements to quorum. This should include ensuring the presence of representatives of the state public administration when a decision is taken. In Australia, for instance, the National Data Advisory Council has set clear rules regarding its internal decision-making processes (see Box 5.5).

Box 5.5. The National Data Advisory Council of Australia

The National Data Advisory Council (NDAC) of Australia provides advice to the National Data Commissioner on data use, trust, transparency and technical best practice. It comprises nine members from the Australian government, business and industry, civil society groups and academia.

The Council provides information on the appointment, the role and the position of its members as well as the frequency and goals of its meetings in its ‘Terms of Reference’. In particular, the document outlines how the position of a member affects his role in the council. While the statistician, the chief scientist and the information and privacy commissioner have to ensure that government data is effectively and safely managed, non-government members should use their individual skills and understanding of the data ecosystem to provide advice to the National Data Commissioner.

The documents also contains practical and administrative information related to meetings attendance, such as the reimbursement of attendance costs to non-government members or the availability of teleconference facilities.

Finally, the Council outlines not only the frequency of its meetings (between two to four times a year), but also the quorum for council meetings (at least six members), and meeting summaries are published on the council website, which ensures council accountability and transparency towards the public.

Source: Adapted from the Office of the National Data Commissioner of the Australian Government, Official Website, (Government, 2019[18]), https://www.datacommissioner.gov.au/about/advisory-council (accessed 03/02/2020)

The council could also consider reinforcing the transparency of the decision-making process by publishing the minutes of meetings. According to article 8 of the Strategic Planning Law regulations, minutes shall be taken for both ordinary and extraordinary meetings. These minutes must be sent to all counsellors, but are not made publicly available. Publishing the minutes is a common practice among different councils in Mexico such as the Independent Technical Council for the Evaluation of Public Policies of Jalisco and the Research and Evaluation Council of Social Policy of the State of México (CIEPS). The council could consider publicising the minutes of its ordinary meeting by default. Meetings of extraordinary meetings may be made public only at the discretion of the council, as some sensitive issues (for example, issues of national security) may be discussed.

Developing innovative knowledge brokering methods to promote the use of evidence

The council could consider innovative knowledge brokerage approaches, to generate knowledge, translate it, and facilitate evidence adoption.

Advisory bodies can act either as knowledge brokers or as knowledge producers. While knowledge producers (which include the academia, statistical agencies and research institutes) provide core scientific, economic and social data and knowledge, knowledge brokers serve as intermediaries between the knowledge producers and the proximate decision-makers (knowledge users) by increasing the availability of robust evidence and by pooling and sorting out the information that is produced by a variety of sources.

The Nuevo León Council in its multi-stakeholder nature brings together actors from different sectors - academia, private sector and government. The council has created a platform for these actors to participate in the advice process. This should be the role of the secretariat to ensure that this knowledge brokerage function is being promoted through participatory and innovative processes. Under this approach, the council could consider adopting knowledge broker functions. Taken as a whole, knowledge broker organisations tend to fulfil three functions:

Generating knowledge: They ensure that there is enough relevant evidence available for decision-makers to answer pre-defined questions by synthesising the available evidence and by identifying knowledge gaps. If knowledge gaps are identified, knowledge brokers can fill them by commissioning research.

Translation of knowledge: When the required evidence is available, they translate knowledge gathered in a language that is understandable for decision-makers.

Facilitating evidence adoption: They build an organisational culture for effective adoption of evidence. They are involved in capacity building activities close to the public service providers and they build networks between knowledge producers and knowledge users. Additionally, they build and maintain informal relations with their stakeholders.

Therefore, as a knowledge broker, an advisory body can provide critical, independent and reliable evidence in a timely and attractive manner, link knowledge sources and users, increase awareness of transferring evidence into practice. It can build capability, and create networks for evidence use (Bressers, 2015[8]). In particular, the council could adopt a knowledge broker role with the capacity of generating knowledge, translating it, and facilitating evidence adoption.

Assessing the effectiveness of the existing evidence and identifying knowledge gaps can be an effective way to support policy-making

A number of policy advisory bodies in the position of knowledge broker use evidence synthesis methods to understand what is already known in a certain subject, and raise awareness of missing evidence for policymaking decisions (OECD, 2020[1]). They are particularly useful as they also help in drawing lessons from knowledge and evidence that is produced in other countries in such a way that it can be mobilised in the national context. These methods can come in a variety of forms, depending on the scope and content of the research, such as the following:

Systematic reviews comprise a methodical literature review of published research to answer a specific question using rigorous procedures to locate, evaluate, and integrate the findings of relevant research (The Campbell Collaboration, 2019[19]). They are critical to identifying what is not known from previous research (Gough D. Oliver S. Thomas J., 2013[20]). On the other hand, there are specific methods such as meta-analysis, which uses statistical methods to compare the effects across different interventions.

Reviews of reviews refer to the study of systematic reviews. It may achieve a broader scope but provide a limited analysis (Saran A. White H., 2018[21]).

Evidence maps evaluate the quality of systematic reviews in a particular field in order to identify reliable evidence and gaps in scientific knowledge (Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services, 2020[22]);

Evidence gap maps identify methods or practices for which no systematic review has been published (Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services, 2020[22]);

The council could consider adopting systematic research processes as part of the commission’s activities to base its advice on the best available research evidence and evaluations. This could ensure that policy design in Nuevo León can rely upon the best global evidence, and provide policy-makers with an understanding of what challenges have been experienced elsewhere; and what good practices could be implemented. Of course, the synthesis needs to look for comparative evidence that can be adapted to Nuevo León, from countries with a similar context and institutional set up. This reflects a global tendency across other OECD countries, particularly in Europe as this approach was initially championed by the UK “What Works” centres and has now been adopted by other countries such as France or Sweden.

The council could translate evidence into clear language to promote its use

Barriers in the use of evidence are not limited to access to accurate technical information. Evidence needs to be translated into understandable language and respond to knowledge users’ needs (Meyer, 2010[23]). A knowledge broker should look for ways to communicate the evidence in an attractive manner that is targeted towards the intended audience. The most common approach to evidence translation is to publish online reports or papers for a broad audience. In Nuevo León, apart from publishing the monitoring of the Strategic Plan, the Knowledge Network of the Council (Red de Conocimiento) has published three annual publications with the second one including ten public policy proposals focused on the priorities of the Plan and the third one including nine public policy proposals with brief summaries for each (Nuevo Leon, 2017[24]). However, most of these reports are long and require time and expertise from the reader to understand the findings that are presented. A simple first step would be to systematically produce executive summaries, with clear limits (e.g a maximum of 1000 words is the practice at the OECD).

Another way of translating evidence is to present data and evidence in a visually attractive and impactful manner through infographics. Chapter 4 provides some recommendations on how to communicate and disseminate evaluation results in a more attractive way. The Early Intervention Foundation from the UK conducts systematic reviews of past trials and evaluations to determine a programme’s effectiveness. In order to present the findings in a form that is easy to grasp for a lay audience, it has created a searchable online database called EIF Guidebook that provides visual cues with which to assess each evaluation (see further information in Box 5.6). Two main criteria are used for this visual assessment: the cost-effectiveness of the intervention and the robustness of the evidence.

The council, through its Knowledge Network, could consider using data visualisation tools to translate the evidence gathered through evidence synthesis methodologies to a wider audience.

Box 5.6. Early Intervention Foundation’s technical support for the use of evidence in policy design and implementation

The EIF Guidebook aims to serve as a starting point for practitioners and policy-makers to find out more about effective early interventions, what good practices look like and how they could be captured in a local context.

The guidebook provides information regarding:

The overall strength of evidence regarding a programme. In fact, the EIF Evidence rating assesses the impact of programmes according to four criteria:

Level 4: There is evidence of a long-term positive impact of the programme through multiple rigorous evaluations.

Level 3: There is evidence of a short-term positive impact of the programme from at least one rigorous evaluation

Level 2: There is preliminary evidence that the programme improves child outcomes, but an assumption of causality

NE/’No effects’: Indicates where a rigorous programme evaluation (level 3) has found no evidence of improving one child outcomes or providing significant benefits to other participants

NL2/’Not Level 2’: Programmes that EIF has assessed and which do not meet the criteria for a level 2 rating.

Cost rating: the guidebook compares the cost of a particular programme to similar ones;

Child outcomes: the guidebook details the specific outcomes found in the studies.

Key characteristics of each programme: the guidebook includes information such as the background against which is was produced, its targeted age group, whether a delivery model was used, whether it was a universal or targeted programme, or information about its theory of change.

Source: Early intervention Foundation (2017[25]),Official website https://guidebook.eif.org.uk/ (accessed 02/10/2020)

Strengthening the networks of knowledge producers and the skills of knowledge users and producers is key to facilitating evidence adoption

Adoption of evidence might also be facilitated by building networks between knowledge producers and users. Knowledge brokers are in the right place in the system to initiate opportunities for meetings that in other circumstances would not happen. The establishment of strong links between researchers and decision makers makes the incursion of evidence to the policy cycle more constant and might lead to an increase in joint projects.

While the Knowledge Network of the Nuevo León Council’s (Red de Conocimiento) seeks to promote the generation of evidence, it does not appear to have a clear role in bridging the gap between policy-makers and academia. This is a role that the council could play. As an example, the Research and Evaluation Council of Social Policy of the State of México (Consejo de Investigación y Evaluación de la Política Social) (2019[26]) stipulates in its functions that: “it creates permanent links with academic institutions, national, and international organisations, to encourage the exchange of ideas and projects aimed at social development”. The council could strengthen the role of the Knowledge Network by defining its principles, vision, and role in the decision making process of the council, and by highlighting the network as a space/opportunity for decision makers and researchers to cooperate. The experience of France Stratégie in fostering networking and in disseminating knowledge can be of interest for Nuevo León (See Box 5.7).

Box 5.7. Fostering dialogue between diverse stakeholders : the example of France Stratégie

To carry out its research, France Stratégie draws on a team of multidisciplinary experts and analysts, but it also works with other external actors in order to ‘co-produce’ knowledge. On its ‘Climate and Territories’ theme, it has set up a consultation with various local governments on issues such as the economy’s metropolisation and local inequalities in order to draw on local innovations and initiatives. It also works on key themes of the French economy, such as promoting productivity, or looking at the long-term impact of fiscal and structural economic policy measures, in terms of taxation or the labour market.

In addition, France Stratégie frequently organises debates with various economic and political actors. In particular, it hosts the ‘Rencontre Europe et International’, a monthly meeting around European issues that brings together various personalities with diverse background (experts, policy-makers, researchers, civil servants). Since 2012, France Stratégie also hosts the platform ‘Responsabilité sociétale des entreprises’, which is a multi-party forum for dialogue on societal responsibility for business that brings together more than 50 member organisations.

Finally, France Stratégie targets a wider public, and specifically young people, through various public debates and conferences, such as the conference on the apprenticeship reform in 2018. In 2019, it also worked on the “great debate”, to foster broader dialogue and to take input from citizens into account.

Source: (France Stratégie, 2018[14])

Developing capacities in the state public administration to support evidence-informed policy-making in Nuevo León

The council can contribute to developing skills for evidence use in the state public administration

Both research and practice indicate that despite the extensive production, communication and dissemination of evidence, its use by decision makers remains limited, and the commitment of top management to evaluation activities remains low (Olejniczak, Raimondo and Kupiec, 2016[27]). Indeed, despite the potential for policies to be based on evidence, an effective connection between the supply and the demand for evidence in the policy making process often remains elusive. Many governments lack the necessary infrastructure to build such effective connections (OECD, 2020[1]), whether at the individual, interpersonal, organisational and environmental level (Newman, Fisher and Shaxson, 2012[28]). Firstly, policy makers may face challenges related to their lack of competence in analysing and interpreting evidence (Results for America, 2017[29]), meaning they do not have the appropriate skills, knowledge, experience or abilities to use evaluation results (Stevahn et al., 2005[30]) (American Evaluation Association, 2018[31]) (Newman, Fisher and Shaxson, 2012[28]). Increasing the uptake of evaluation evidence by policymakers can therefore be achieved through the development of their competences.

Country practices reveal a wide range of approaches aimed at developing competences for use of evidence. Mechanisms aimed at increasing the demand for evidence include practices such as training aimed at senior civil servants or policy professionals and mentoring initiatives (OECD, 2020[1]). The work by the OECD on Building Capacity for Evidence Informed Policy Making (OECD, 2020[1]) suggests that training for senior civil service leadership is aimed at increasing managers’ understanding of evidence-informed policy making and policy evaluation, enabling them to become champions for evidence use. Intensive skills training programmes aimed at policy makers may be more focused on interrogating and assessing evidence and on using and applying it in policy making.

As a producer of evidence related to the Strategic Plan, the council could organise more capacity building initiatives to develop skills within the state public administration. Training for senior civil servants increases managers’ understanding of evaluation and their ability to interrogate and assess evidence, as well as using it in policy-making. The council has already conducted such trainings and could continue to do so by leveraging its connection to academia, in particular schools of government, so they organise training programmes for civil service leadership. Such trainings can take the form of workshops, masterclasses and seminars. These would not only reinforce skills for the uptake of evidence but also increase the motivation and incentives for decision-makers in the state public administration to use evidence. Significant progress in terms of evidence uptake has been observed in Mexico City for instance, where initiatives that inform policymakers about the objectives and value of evaluations have been undertaken. Moreover, the council has been an intermediary of projects coordinated with the federation for training officials at the state level, such as a training for officials organised in 2018 on the methodology of obtaining federal funding via cost-benefit analysis, among other tools. This experience in training for government officials may facilitate the council’s organisation for trainings specifically focused on the uptake of evaluation evidence by policy makers.

Evidence-informed policy-making will require the establishment of institutions and systems in the state public administration

Nevertheless, it is primarily institutions, organisational structures and systems that enable the effective use of evidence: Without addressing these, initiatives for evidence-informed policy-making in Nuevo Léon are unlikely to succeed. Building capacity for evidence use requires systemic and institutional approaches that include strengthening organisational tools, resources and processes, investing in basic infrastructure, including data management systems and knowledge brokers, and establishing strategic units to champion an evidence-based approach. Mandates, legislation and regulation are also important tools for facilitating the use of evidence (OECD, 2020[1]). Finally, the long-term institutionalisation of EIPM can be assisted by the machinery of government, such as a strategy unit or another entity at the centre of government with a clear responsibility and mandate over EIPM.

Recommendations

Strengthen the leadership role of the council as part of Nuevo León’s policy advisory system, with a broader whole-of-government perspective. This may also require:

Identifying gaps in the advisory system

Ensuring representativeness of different disciplines as well as representing the sociodemographic and economic diversity of the community

Facilitating a networked approach with other knowledge providers

Enhance Nuevo León’s council functions on evaluation and evidence provision. The council should be equipped to act as a strategic knowledge broker, operating at arm’s length from the government while keeping a symbiotic relationship with the state administration to:

Provide credible evidence at the highest levels, and in doing so, contribute to shaping the policy agenda.

Increase the efficiency of the policy advisory system in Nuevo León. Bodies that are closer to the government and therefore more closely linked to the administrative mandate would be in a better position to contribute to policy implementation and monitoring, while the council could focus solely on evidence and evaluation and strategic planning to shape the reform agenda and chart a way forward for the state in the future.

Clarify the roles of advisors and policy-makers. This may alleviate political tensions with the state public administration, which is in charge of implementation. This would enable the council to focus on its main role of long-term planning and policy advice.

Foster inclusiveness and expertise in the council’s decision-making process, providing relevant advice. This requires the council to consider a multitude of interdependent factors to reinforce the effectiveness of the advice, such as timeliness, representativeness, and credibility to:

Make a calendar with the dates for publications.

Ensure that commissioners are able to provide a neutral view, have a sufficient credible level of expertise, and that they represent the sociodemographic and economic diversity of the community.

Provide professional qualifications and training to the members of the council.

This may require updating the Strategic Planning Law’s guidelines or the Council’s guidelines.

Implement knowledge brokering methods in the council, to promote the impact and use of evidence. The council should consider adopting knowledge brokering methods such as generating, adopting and translating evidence to:

Ensure that there is enough relevant evidence available to decision-makers in Nuevo León to answer pre-defined questions by synthesising the available evidence and by indicating knowledge gaps.

Provide critical, independent and reliable evidence in a timely and attractive manner, for instance with data visualisation tools to translate the results of evidence synthesis exercises for a wider audience.

Build networks between knowledge producers and knowledge users.

Strengthen capacities for evidence-informed policy-making in Nuevo León by:

Strengthening the council’s permanent capacity-building activities to develop new skills among knowledge users and producers, particularly in the state public administration.

Developing systemic and institutional approaches for evidence-informed policy making in the state public administration, for instance through establishing strategic units to champion an evidence-based approach in the centre of government.

References

[31] American Evaluation Association (2018), Guiding Principles.

[9] Blum, S. and K. Schubert (2013), Policy analysis in Germany., Policy Press.

[8] Bressers, D. (2015), Strengthening (the institutional setting of) strategic advice: (Re)designing advisory systems to improve policy performance. Research on the practices and experiences from OECD Countries.

[13] Cash, D. et al. (2003), “Knowledge systems for sustainable development”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Vol. 100/14, pp. 8086-8091, http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1231332100.

[7] Christensen, J. and K. Serrano Velarde (2019), “The role of advisory bodies in the emergence of cross-cutting policy issues: comparing innovation policy in Norway and Germany”, European Politics and Society, Vol. 20/1, pp. 49-65, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2018.1515864.

[26] Consejo de Investigación y Evaluación de la Política Social (2019), Atribuciones, http://cieps.edomex.gob.mx/atribuciones (accessed on 21 November 2019).

[4] Craft, J. and J. Halligan (2015), Looking back and thinking ahead: 30 years of policy advisory system scholarship.

[25] Early Intervention Foundation (2017), Getting your programme assessed | EIF Guidebook, http://dx.doi.org/12345.

[10] European Commission (2019), “Scientific Advice to European Policy in a Complex World”, http://dx.doi.org/10.2777/68120.

[14] France Stratégie (2018), France stratégie, plaquette 2018.

[20] Gough D. Oliver S. Thomas J. (2013), Learning from research: systematic reviews for informing policy decisions.

[15] Government of Canada (2011), Health Canada Policy on External Advisory Bodies, https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/public-engagement/resource-centre/policy-external-advisory-bodies-health-canada-2011.html#a2.3 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

[18] Government, O. (2019), , https://www.datacommissioner.gov.au/about/advisory-council.

[5] Hoppe, R. (1999), “Policy analysis, science and politics: From ’speaking truth to power’ to ’making sense together’”, Science and Public Policy, Vol. 26/3, pp. 201-210, http://dx.doi.org/10.3152/147154399781782482.

[6] Hustedt, T. (2019), “Studying policy advisory systems: beyond the Westminster-bias?”, Policy Studies, Vol. 40/3-4, pp. 260-269, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2018.1557627.

[17] Institute, Y. (2020), , https://www.dji.de/en/about-us.html.

[23] Meyer, M. (2010), “The Rise of the Knowledge Broker”, Vol. 32/1, pp. 118-127, https://hal-mines-paristech.archives-ouvertes.fr/file/index/docid/493794/filename/Rise_of_Broker.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2019).

[28] Newman, K., C. Fisher and L. Shaxson (2012), “Stimulating Demand for Research Evidence: What Role for Capacity-building?”, IDS Bulletin, Vol. 43/5, pp. 17-24, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2012.00358.x.

[24] Nuevo Leon (2017), Annual Government report 2017-2018, http://www.nl.gob.mx/sites/default/files/3er_informe_2015-2021_documento_narrativo.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2019).

[1] OECD (2020), Improving Governance with Policy Evaluation: Lessons From Country Experiences, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/89b1577d-en.

[3] OECD (2017), “Policy Advisory Systems - Supporting Good Governance and Sound Public Decision Making”, https://www.oecd.org/governance/policy-advisory-systems-9789264283664-en.htm (accessed on 21 October 2019).

[27] Olejniczak, K., E. Raimondo and T. Kupiec (2016), “Evaluation units as knowledge brokers: Testing and calibrating an innovative framework”, Evaluation, Vol. 22/2, pp. 168-189, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1356389016638752.

[2] Parkhurst, J. (2017), The politics of evidence : from evidence-based policy to the good governance of evidence, Routledge, London, http://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/3298900/ (accessed on 23 November 2018).

[16] Quad Cities Community Foundation (2018), Advisory Board: Best Practices and Responsibilities, https://www.qccommunityfoundation.org/advisoryboardbestpracticesandresponsibilities (accessed on 5 November 2019).

[29] Results for America (2017), 100+ Government Mechanisms to Advance the Use of Data and Evidence in Policymaking: A Landscape Review.

[21] Saran A. White H. (2018), Evidence and gap maps: a comparison of different approaches.

[11] Secretary of the State (2009), Organic Law of Public Administration from the State of Nuevo Leonn, http://sgi.nl.gob.mx/Transparencia_2015/Archivos/AC_0001_0002_0167618-0000001.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2020).

[12] State of Nuevo Leon (2019), Instituto Estatal de la Juventud: Facultades y atribuciones, http://www.nl.gob.mx/dependencias/juventud/75391/responsabilidades (accessed on 8 April 2020).

[30] Stevahn, L. et al. (2005), “Establishing Essential Competencies for Program Evaluators”, ARTICLE American Journal of Evaluation, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1098214004273180.

[22] Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (2020), Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services Official Website, https://www.sbu.se/sv/ (accessed on 3 February 2020).

[19] The Campbell Collaboration (2019), Campbell systematic reviews: Policies and Guidelines.