This chapter provides an in-depth analysis of the methodology used to develop Nuevo León’s main long-term planning tool, the Strategic Plan 2015-2030 “Nuevo León Mañana”, as well as its consequent structure. OECD findings suggest that the joint effort by government and civil society to design the strategy has resulted in the widespread perception that it is an important initiative for the state. Yet, the methodology suffered from some technical shortcomings and did not leave enough space for prioritisation of long-term policy objectives. As a result, the structure of the document is not coherent, which makes it difficult to use as a planning tool.

Monitoring and Evaluating the Strategic Plan of Nuevo León 2015-2030

2. The Strategic Plan’s Methodology and Structure: Identifying Clear and Sound Policy Priorities for Nuevo León

Abstract

Introduction

The Strategic Plan reflects a high-level commitment to long-term policies in Nuevo León

The main planning instrument of Nuevo León’s council is the Strategic Plan for the state of Nuevo León 2015-2030 “Nuevo León Mañana” (SP). The Plan is widely perceived as an important initiative, especially as it is the first integrated long-term planning instrument designed jointly by government and civil society in a Mexican subnational government. The Strategic Plan also brings value as it offers the possibility to plan beyond the electoral cycle, which offers opportunities to bring greater stability to policy making.

The Strategic Plan was published in 2016, following almost a year of events, meetings, public consultations with citizens and experts from the council’s commissions (Council of Nuevo Leon, 2019[1]). These stakeholders worked with the state government to define key indicators for monitoring the plan and aligning the visions of each commission. Article 3 of the Strategic Planning Law states that in addition to contributing to the sustainable development of the state, the Plan aims to consolidate democracy, promote government integrity, accountability, efficiency and productivity.

The Plan’s development started with a comprehensive diagnosis of the economic, environmental and social conditions of the state of Nuevo León. The data was collected by a consulting firm through benchmarking exercises, interviews with experts, and different sources such as the different secretaries of the state government and the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). The diagnosis exercise aimed to be consensual, with an element of civic participation through the organisation of expert and public consultations.

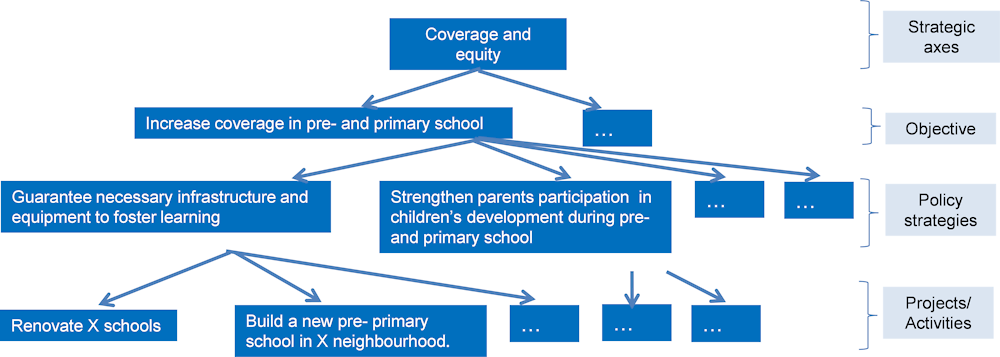

This analysis led the commissions to identify many “opportunity areas” for the state of Nuevo León. These opportunity areas were then prioritised according to their degree of feasibility and impact. The Strategic Plan is organised into 11 thematic areas (each one associated with a sub-commission or commission of the council) with 47 opportunity areas, divided into 101 strategic lines and accompanied by 45 projects (see Figure 2.1). Moreover, the Plan has 8 transversal central themes.

Figure 2.1. Pyramid of the main layers of the Strategic Plan

Note: This figure represents the main layers of the Plan and their hierarchical structure in general terms. However, it should be noted that certain sub-commissions have chosen to use a slightly different structure as is further explained in this chapter.

Source: Authors

Developing a robust planning methodology in Nuevo León

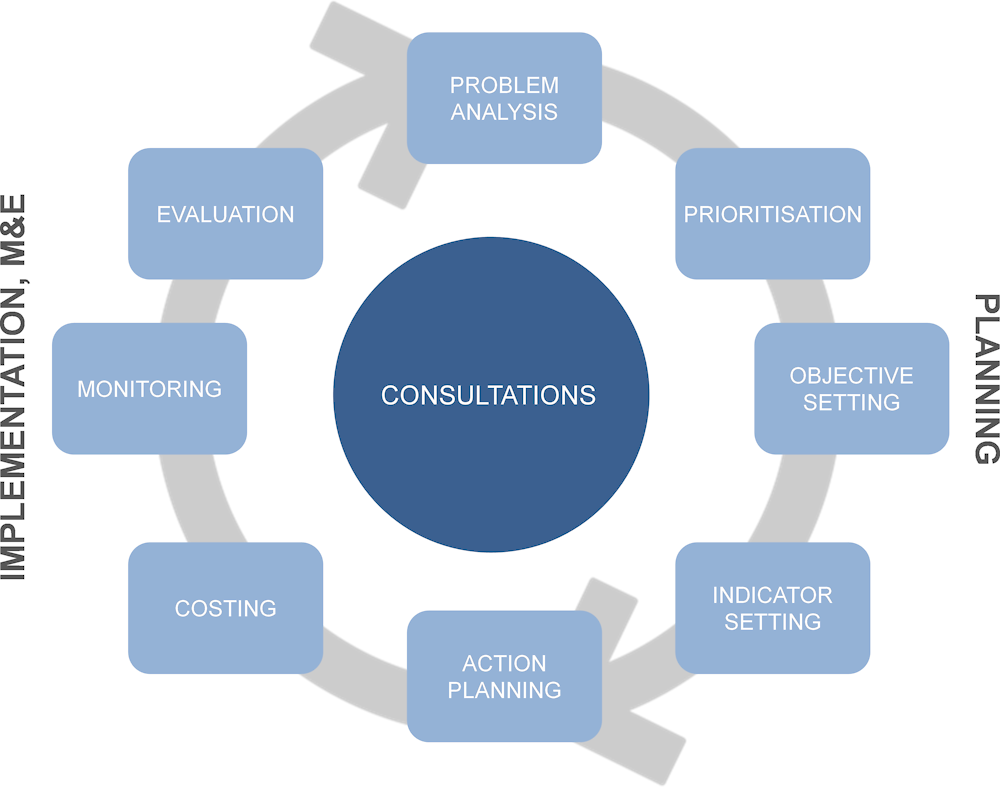

Strategy setting can be defined as a dynamic, complex, iterative and interactive process, by which a government identifies problems; defines and prioritises its objectives; plans activities to achieve those objectives; and sets a measurement framework to validate progress (OECD, 2018[2]). The strategy setting process can be divided into two main phases: the planning phase, and the implementation, monitoring and evaluation phase.

In line with the observed methodology in most OECD countries (see the strategy setting cycle in Figure 2.2), Nuevo León’s 2030 planning phase began by conducting a diagnosis of the current situation in five chosen thematic areas (problem analysis phase): Human and Social Development, Sustainable Development, Economic Development, Security and Justice, and Effective Government and Transparency. Subsequently, Nuevo León went through a prioritisation phase and defined several layers of objectives (opportunity areas, strategic lines and actions).

Figure 2.2. Strategy setting process

Note: The cycle approach is just one way of presenting the complex process of strategy development and implementation; however, the phases of the process are not necessarily consecutive. For instance, action planning can be done at the same time as objective setting.

Source: OECD (2018)

The problem analysis phase did not build on lessons learned from previous reforms

Problem analysis, which is the analysis of the current state of affairs (achievements, challenges and opportunities) based on lessons learned from previous reforms and development plans, is an essential step for strategic planning (OECD, 2018[2]). It provides lessons on why previous policies were successful or not, as well as the evidence base for prioritisation and objective setting (steps 2 and 3 of the strategy setting process).

In Nuevo León, the data for the diagnosis in each thematic area was collected by a consulting firm through benchmarking exercises, interviews with experts, and different sources such as the different secretaries of the state government and the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) (Council of Nuevo León, 2016[3]).The diagnosis aimed to be consensual, with an element of civic participation through the organisation of expert and public consultations (Council of Nuevo León, 2016[3]). Therefore, the diagnosis has been context-specific, shared by the major stakeholders and based on sound international and national sources – thus laying a credible evidence-base for the rest of the strategic planning.

Nevertheless, the diagnosis established for each commission/sub-commission (section on “Diagnóstico de la situación actual”) did not systematically include a thorough assessment of previous reform initiatives in Nuevo León. In order for strategic planning to be truly effective, it should draw lessons from previous reforms and evaluate why previous plans or reforms have succeeded (or failed).

The prioritisation process omitted factors such as sequencing and trade-off between opportunity areas

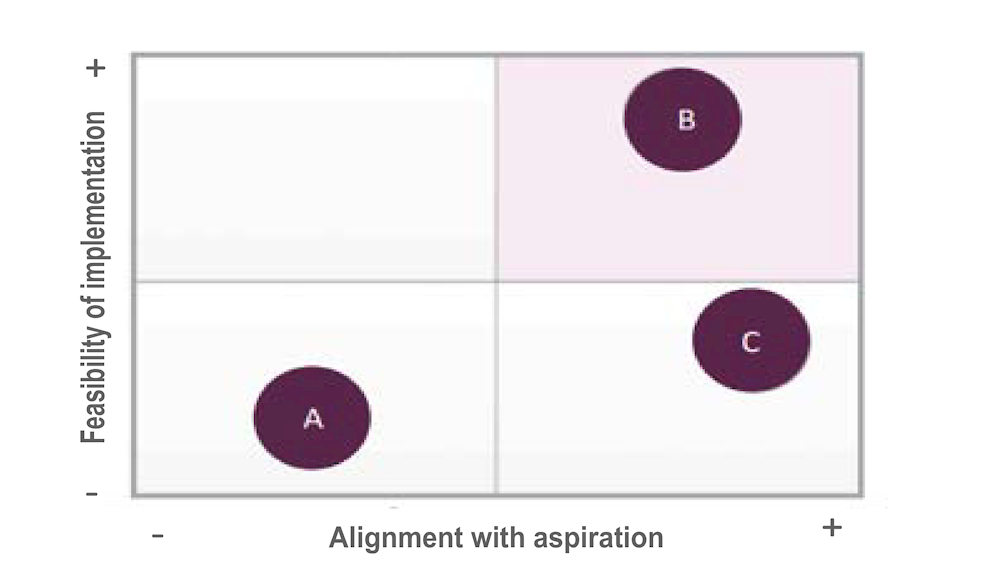

These diagnoses led the commissions to identify many opportunity areas for the state of Nuevo León. As Figure 2.3 shows, these opportunity areas were then prioritised according to their degree of feasibility and impact: In the end, 47 opportunity areas were retained.

Figure 2.3. Methodology for prioritising opportunity areas

Source: Adapted from Council of Nuevo León (2016[3]). Plan Estratégico para el Estado de Nuevo León 2015-2030 [Strategic Plan for the State of Nuevo León 2015-2030], http://www.nl.gob.mx/publicaciones/plan-estrategico-para-el-estado-de-nuevo-leon-2015-2030

This type of prioritisation is crucial to ensure that the designed plan is realistic and can be implemented (OECD, 2018[2]). In Nuevo León, the general perception from stakeholders is that the Strategic Plan accurately reflects the general priorities of the state from the point of view of civil society, suggesting that the prioritisation exercise led by the commissions and the consultancy firm was effective in identifying most important long-term issues for the state.

However, the methodology did not take into account how the different opportunity areas link to each other, and specifically how some opportunity areas may actually contribute to the achievement of others. Likewise, the methodology does not offer an analysis of potential trade-offs between opportunity areas.

For instance, the “Effective Government and Transparency” commission left aside opportunity areas such as “Access to information” or “Open and Transparent State” to favour much broader objectives such as “Accountability in Public Institutions”. Nevertheless, OECD experiences show that both access to information and open and transparent government, like integrity, can be key elements to achieving accountability in public institutions (OECD, 2017[4]).

Similarly, the “Effective Government and Transparency” axis mostly includes opportunity areas related to anti-corruption and control. Including further opportunity areas on the topic of good governance, state modernisation and public spending efficiency may be a way to support the implementation of the Plan. Most other states in Mexico have chosen to select opportunity areas or strategic lines related to these topics (see Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. Public governance objectives in the states of Jalisco and Guanajuato

The State Development Plan of Jalisco (“Plan Estatal de Desarrollo 2013-2033”) mentions that government transparency, accountability and modernisation are some of the state’s main objectives. Therefore, the Plan aims at strengthening public management, with particular focuses on topics such as anticorruption, open government, efficient resource allocation, civil service skillset, communication and planning. Opportunity areas include strengthening public access to information, involving civil society organisations and academia in policy-making, reinforcing the role of the monitoring and evaluation institutions, etc.

In the same vein, the State Development Plan of Guanajuato (“Guanajuato 2040”) has a strategic line for public governance, which seeks to improve the efficiency and efficacy of the public sector, open government and planning. The state’s main challenges for the coming years are to strengthen the monitoring and evaluation system in line with the municipalities, to increase citizen participation, to ensure public budgeting efficiency as well as to increase government transparency and accountability.

Source: Adapted from Gobierno de Jalisco (2013[5]), Plan Estatal de Desarollo Jalisco 2013-2033 [Jalisco State Development Plan 2013-2033], https://sepaf.jalisco.gob.mx/sites/sepaf.jalisco.gob.mx/files/ped-2013-2033_0.pdf. Gobierno de Guanajuato (2018[6]) , Plan Estatal de Desarollo Guanajuato 2040 [Guanajuato State Development Plan 2040], https://www.guanajuato.gob.mx/pdf/Gto2040_WEB.pdf

Objective setting did not rely on a clear logic model and some objectives are difficult to measure or to understand

Objective setting is the process by which policy-makers define the level of ambition of change compared to the current state of affairs, in relation to the selected problems to be addressed (OECD, 2018[2]). In the case of the Strategic Plan, the objective setting stage was key to breaking down the vision into aspirations; opportunity areas, strategic lines and initiatives, as well as projects (see also Figure 2.1 for a schematic representation of the Plan’s layers).

Objective setting for the Strategic Plan did not consistently rely on a clear logic model (or theory of change see Box 2.2) or even a shared methodology amongst commissions ensuring consistency between the level of objective (outcome or output objective for example) defined for opportunity areas throughout the Plan. It lacks an explicit or consistent framework to define how a downstream layer, for example a strategic line, can influence an upstream layer, for example, an opportunity area across the various commissions. As a result, the Plan does not demonstrate how the state government should and can mobilise its resources in order to reach the intended policy results – making buy-in for the Plan more difficult.

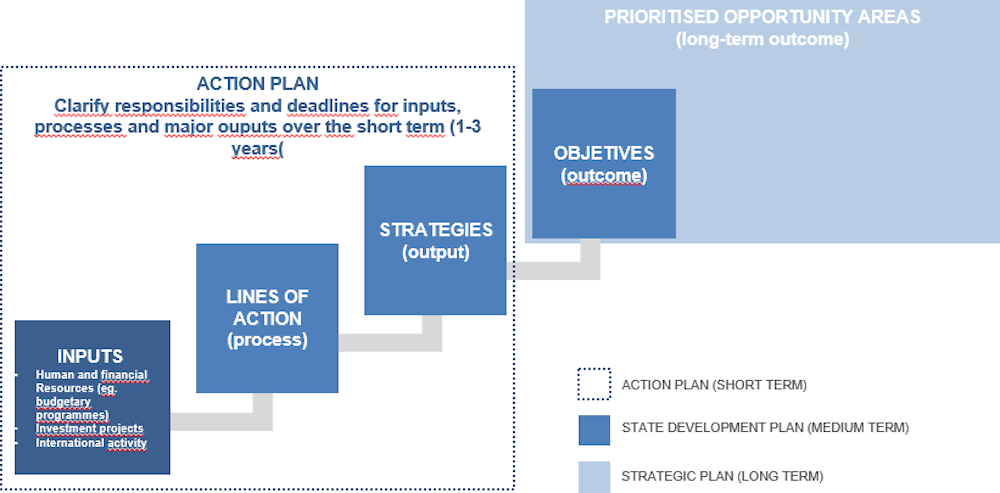

A more consistent framework would entail some coherent links for how inputs and processes can be geared towards outputs and achieving outcomes, along the policy value chain, as is demonstrated in Figure 2.4. Reliable data is also required to inform the setting of objectives, targets and eventually performance indicators.

Figure 2.4. Moving from objectives to impact

This lack of a consistent framework and reliable data affects the adaptability of the Plan in the face of changing political, economic and social circumstances. Indeed, having a clear understanding of the conditions for change would allow decision-makers to make corrections if the selected approach is not working or if anticipated risks materialise (see Box 2.2).

Box 2.2. Theory of change

Theory of change is a method to trace the way in which an intervention (understood as plan, programme, project, etc.) or set of interventions is going to lead to specific changes, drawing on a causal analysis based on available evidence. Developing a theory of change method helps identify effective solutions to the factors hindering the progress of the intervention and direct the decision maker on what approach to take, after analysing the resources in hand and the current and future context where the intervention is developed. Moreover, it also helps identify the underlying assumptions and risks that will be vital to understand and revisit throughout the process to ensure the approach will contribute to the desired change.

Using theory of change can be instrumental in a scenario where multiple interactions between many factors create complex challenges. It is the case for example, when governments embark on a structural reform of the executive in order to improve efficiency in the provision of public services. Although the design of the reform is well suited, elements such as political priorities, budgeting constraints and institutional culture come into play and the reform may not lead to the expected results. A theory of change can help a government systematically think through the many underlying and root causes of the challenges, and how they influence each other, when determining what should be addressed as a priority.

Additionally, a theory of change provides a framework for learning both within and between cycles of the intervention. By structuring the causes of the challenges, proposing a strategy to reach the expected results supported by concrete assumptions, and testing these assumptions against evidence, theory of change promotes a solid logic for achieving change. This allows the decision maker to make corrections if the selected approach is not working or if anticipated risks materialise.

Finally, theory of change promotes agreement among stakeholders by having a participatory approach on the planning process where their insights explicitly contribute to long-term impact.

Source: Adapted from United Nations Development Group – UNDG (2017[8]), Theory of Change: UNDAF Companion Guidance. https://undg.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/UNDG-UNDAF-Companion-Pieces-7-Theory-of-Change.pdf

The objectives should be formulated in simple language, avoid the use of abbreviations, professional jargon and long and complex sentences (OECD, 2018[2]), if they are to be clearly understood by stakeholders and the public. In order to ensure that objectives set out a realistic and clear pathway for policy reform, the suitability of objectives can be tested against the so-called SMART model, explained in detail in Box 2.3.

In the case of the Strategic Plan, opportunity areas do not consistently hold up to this framework. Opportunity areas such as “Promote the prevention of high frequency crime” do not appear to be concrete concerning the intentional impacts for society, as the concept to “Promote” is not necessarily linked with better outcomes. Another example are the areas of opportunity of the Effective Governance and Transparency Commission. Under their current format, opportunity areas such as “Vulnerable procedures, services and operations” or “Canales de detección” are neither measurable nor action-oriented. Moreover, the Human Development’s priority opportunity area “Prevent family and community violence” would benefit from being more specific and containing measurable goals.

Box 2.3. The SMART model

Objectives should be:

Specific: an objective must be concrete, describing the result to be achieved, and focused, contributing to the solution of the problem;

Measurable: an objective should be expressed numerically and quantitatively in relation to a specific benchmark, and should allow the progress of implementation to be tracked;

Action-oriented/ Attainable/ Achievable: an objective should motivate action, and it should state what is to be improved, increased, strengthened, etc., but it should also be reachable;

Realistic: an objective should be realistic in terms of time and available resources;

Time-bound: the achievement of the objective should be specified in terms of a time-period.

In many cases it is the associated indicators with their baselines and targets that make an objective measurable and time-bound. However, it is important to keep this model in mind in order to set simple, clear and easy-to-read objectives.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2018[2]), “Toolkit for the preparation, implementation, monitoring, reporting and evaluation of public administration reform and sector strategies: Guidance for SIGMA partners”, SIGMA Papers, No. 57, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Simplifying the Plan’s structure

This section takes a closer look at the internal structure of the Strategic Plan by looking at the major elements comprising the layers (i.e., vision, aspirations, prioritised opportunity areas, strategic lines and initiatives, strategic projects) of the strategy. During the first fact-finding mission, the vast majority of interviewed stakeholders described the Plan as too complex.

The Plan has been broken down into too many layers

Practice-based evidence suggests that the Strategic Plan has too many layers. The Strategic Plan has five main layers that break down the vision and aspirations (which are intentions more than objectives), into prioritised opportunity areas, strategic lines, strategic initiatives and strategic projects (see figure 3.3). International good practice recommends that each layer of a development plan should correspond to a level of the policy value chain (see Figure 2.5) (Máttar and Cuervo, 2017[9]). It also suggests that long term strategic planning should be focused on impacts and long-term outcome objectives (Schumann, 2016[7]) along the policy value chain. Figure 2.5 offers a schematic representation of the policy value chain.

Figure 2.5. Policy value chain

Source: Authors

In the case of Nuevo León, this would suggest that prioritised opportunity areas are meant to be long-term outcome/impact level objectives, while strategic lines, initiatives and projects should be respectively output, process and input level objectives. Nevertheless, the Strategic Plan of Nuevo León does not rest on a clear logical framework, as seen in section 3.1. Therefore, it is difficult to identify all opportunity areas to outcome level objectives, or strategic lines to output level objectives.

Fewer layers, and therefore greater clarity, would allow the Plan to be more readily understood and used by the public. This also enables greater adaptability in development planning as inputs and outputs may change depending on fiscal, economic, political and social circumstances, while policy impacts remain more stable in the longer-term. In that sense, the Strategic Plan would benefit from being refocused on the long-term impact/outcome levels, as is common practice in long-term strategic planning. As a result, the Strategic Plan should only retain one of its layers, specifically the priority opportunity areas, which would correspond to long-term outcome level objectives. Output-level objectives, process and inputs, should be reserved for the State Development Plan and, until the achievement of this alignment between both plans, to the action plan (see section 4.3 on the latter).

Opportunity areas have been insufficiently prioritised

The current Strategic Plan for Nuevo León contains prioritised opportunity areas and projects that go beyond the state’s financial capacities, which reduces its credibility and effectiveness as a tool for policy implementation. Good international practices suggest that there should only be a limited number of objectives in order to focus and mobilise resources for their achievement. Conversely, too many objectives will scatter scarce resources and lead to unfocused delivery of policies and reforms (OECD, 2018[2]).

Yet, the Strategic Plan is organised into 11 thematic areas (each one associated with a sub-commission or commission of the council) with 47 opportunity areas, divided into 101 strategic lines and accompanied by 45 projects. The Plan also has eight transversal central themes. A gap analysis shows that at least five opportunity areas of the Strategic Plan remain completely unlinked to objectives of the State Development Plan (see Annex 2.B), suggesting that these opportunity areas have not been costed in the budget of the state administration. This plethora of objectives can reduce the policy impact of the Plan.

As underlined by several key stakeholders during the first OECD fact-finding mission, greater prioritisation will be crucial in rendering the Plan more realistic in light of the state’s limited fiscal and budgetary margins of manoeuvre (Council of Nuevo León, 2017[10]). Prioritisation is necessary to ensuring that the strategy is realistic and can be implemented with the state’s existing resources. It will therefore be important that the plan be thoroughly examined by the Public Finance Commission to ensure credible pathways for implementation in the future, so that resources can be clearly identified.

The coherence between thematic areas can be improved

A closer look at the Plan shows that there are important disparities in the number of prioritised opportunity areas attributed to each commission. For instance, the Human Development Commission monitors 53% (28 of the 47) of the prioritised opportunity areas (for the sub-commissions on Education, Social Development, Health, Art and Culture, Sports, Citizenship, and Citizen’s participation), whilst the commission on Security and Justice is in charge of 9% (5 prioritised opportunity areas).

Because each commission is responsible for the monitoring and evaluation of the opportunity areas that fall under its thematic area, having important disparities in the number and type of prioritised opportunity areas monitored by each commission has made their work more difficult. In particular, the Human Development Commission monitors a large number of prioritised opportunity areas through its sub-commissions, potentially hindering greater internal coordination and homogeneity in the work of the commissions.

The number of layers varies between thematic areas, with some commissions, such as the economic development commission who chose to forgo the strategic lines (only retaining prioritised opportunity areas and strategic initiatives). Moreover, the prioritisation criteria of the opportunity areas might not be clear for all the commissions or sub-commissions. In fact, some commissions developed strategic lines and initiatives for opportunity areas that were not a priority according to the feasibility/impact matrix. This is the case for the sub-commission on Health with the opportunity areas “Acceso y atención inmediata en caso de infarto de miocardio” and “Detección temprana y atención inmediata de diabetes, hipertensión y depresión”. This scenario is also found in the sub-commission on Sport and the commission on Economic Development. This creates confusion about the exact number of priority opportunity areas in each commission and for the Plan over all, when the priority opportunity areas are meant to be the cornerstones of the Strategic Plan.

Given the importance of communicating objectives and priorities in order to ensure political support for the reform, the lack of standardisation between thematic areas may lead to diminished legibility within and outside the administration. The lack of clarity around the priority opportunity areas may also affect the buy-in for the Plan.

Planning coherence: aligning policy priorities and identifying pathways for their implementation

Despite the fact that Mexico is a federal country, policy and budgetary decisions remain highly centralised. Most policies are designed at the national level and are implemented at the state or local level (OECD, 2017[11]). Therefore, strategic planning at the state level needs to involve both horizontal (cross-government/inter-ministerial/inter-agency) and vertical (within government/a ministry/a sectoral policy issue) approaches to better allow the political and administrative levels to identify priority objectives, and allocate resources and decision-making authorities accordingly (OECD, 2012[12]).

Formal instruments for co-operation between the federal government and the state governments include the National Development Plan 2019-2024 NDP), which is intended to prioritise and promote policy alignment across levels of government. Each State Development Plan must be designed in accordance with the guidelines set out in the NDP. The NDP also includes inputs from the different federal departments and agencies as well as those of the state governments and civil society (OECD, 2017[11]).

The current administration of Nuevo León devised a State Development Plan (SDP) upon entering into office, as required by Mexican legislation. To do so, the state created the 2016 Strategic Planning Law, which is the legal framework for planning in the state. According to article 16 of the Strategic Planning law, the SDP identifies medium-term priorities for state development, as well as guidance in results-based management and results-based budgeting. It also defines its strategic projects and priority programs, consistently with the Strategic Plan.

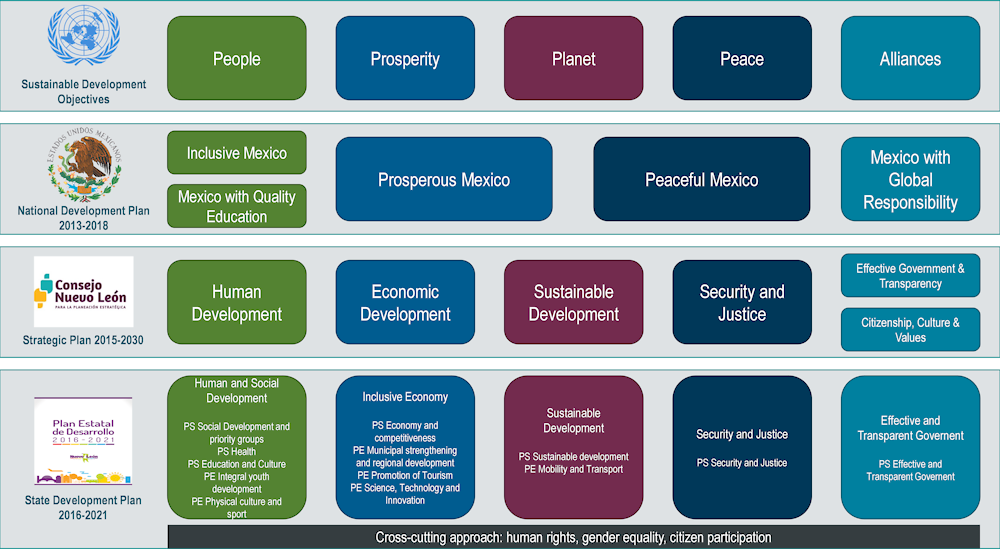

Other planning instruments include guidelines and calls for actions like the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations, adopted in 2015. Although the 2030 Agenda is not binding, countries are expected to take action, involving the regional and local levels of government, civil society and the business sector. Bearing in mind this commitment, the government of Mexico has aligned the five strategic axes of the National Development Plan 2013-2018 with the SDGs. States also have to promote such alignment, hence both the Strategic Plan and the State Development Plan of Nuevo León should contribute to achieving the 2030 Agenda.

A first look at the structure of the Strategic Plan of Nuevo León shows that it seeks to address the same major policy areas as the SDGs, the National Development Plan 2013-2018 and the State Development Plan 2016-2021 (see Figure 4.1), suggesting that the council’s intention was to ensure alignment, or at the very least coherence, between these instruments.

While there is some broad coherence at a higher level, the challenge is the lack of articulation from a methodological and practical perspective, in particular with the State Development Plan and the budget.

Figure 2.6. Thematic alignment between the SDGs, the National Development Plan, the Strategic Plan and the State Development Plan of Nuevo Léon.

Note: the council of Nuevo Léon created a finance commission post-2016, which is not shown in this figure.

Source: Adapted from state of Nuevo Léon (2018[13]), Guía Metodológica para la formulación del Plan Estatal de Desarrollo 2016-2021 [Methodological guide for the formulation of the State Development Plan 2016-2021]

There are some inconsistencies in aligning the methodological framework of the Strategic Plan with the SDGs

The council of Nuevo León was mandated to oversee the implementation of the SDGs (Nuevo León Council, 2017[14]). The fact that the timeline of the Strategic Plan (2015-2030) is aligned to that of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development shows the commitment of the council and the state of Nuevo León to pursue this international agenda of social inclusion, poverty reduction, gender equality, environmental sustainability and just and peaceful societies. In fact, 14 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals are reflected in their substance in one or several opportunity areas of the Plan (see Table 2.1 for an example of this alignment and Annex A for a more detailed analysis of the alignment between the SDGs and the SP).

Table 2.1. Alignment of the SDGs with the Strategic Plan (selected)

|

SDG Goals (Agenda 2030) |

Priority opportunity areas of the Strategic Plan (2015-2030) |

|

GOAL 1: No Poverty |

10. Eradicate extreme poverty with special emphasis on food security. |

|

11. Reduce urban poverty. |

|

|

GOAL 3: Good Health and Well-being . |

6. Education and early detection to prevent overweight, obesity and diabetes. |

|

7. Ensure coverage and effective access of the population for priority health conditions |

|

|

8. Guarantee quality through an independent health commission that monitors standardized indicators and a professionalized health management. |

|

|

9. Early detection and immediate attention for breast cancer and pelvic-uterine cancer. |

|

|

20. Foster physical activity in schools. |

|

|

GOAL 12: Responsible Consumption and Production |

N/A |

Note: The table does not aim to be exhaustive, see Annex A for a thorough analysis of the coherence between the SP and the SDP.

Source: Authors

However, the OECD has found that there is no clear methodological framework to link the Strategic Plan with the SDGs (OECD, 2018[2]). For instance, some SDGs are reflected in a single opportunity area, while others are reflected in several or none at all. This lack of systematic linkage, both in terms of substance (as three SDGs are not reflected in the Plan) and language (the opportunity areas do not use the same key words as the SDGs) will make monitoring the progress of the SDGs in Nuevo León, and how the Strategic Plan contributes to the process, difficult. Moreover, the lack of a clear methodological framework is somewhat reflected in the institutional arrangements, as the exact manner in which each commission is to oversee the implementation of the SDGs relevant for their theme of work is yet to be determined.

There is no clear methodological framework for articulating the elements of the Strategic Plan with the elements of the State Development Plan (SDP)

Strategic planning in the state of Nuevo León rests on a nested hierarchy across levels of government, as the Federal Planning Law of 5 January 1983 suggests that the state’s plans be aligned with the National Development Plan (2013-2018), while the state planning law dictates that the Strategic Plan (2015-2030) and the State Development Plan (2016-2021) be aligned to one another1

In spite of these legal provisions, there is no clear methodological framework to articulate the elements of the Strategic Plan with the elements of the State Development Plan (SDP), as can be seen in Table 2.2. While many of the opportunity areas of the Strategic Plan resonate with the objectives or lines of action of the Development Plan, their alignment is not systematic. Firstly, links between the two Plans do not follow a consistent pattern (for example, the substance and language of prioritised opportunity areas – SP – and objectives – SDP – being coherent). Instead, a detailed analysis of both Plans shows that opportunity areas sometimes find resonance in objectives, strategies or lines of actions indifferently. Conversely, five opportunity areas2 do not find any resonance in the State Development Plan.

Table 2.2. Examples of the current coherence between the Strategic Plan and State Development Plan

|

Opportunity areas of the Strategic Plan |

State Development Plan |

|---|---|

|

Human Development Commission |

Human and Social Development chapter |

|

Prioritised opportunity area 1. Increase coverage in early childhood and preschool education |

Objective 6. Achieve total coverage in education. |

|

Prioritised opportunity area 2. Increase coverage and graduation efficiency rate in upper secondary education |

Objective 6. Achieve total coverage in education. |

|

Prioritised opportunity area 3. Ensuring mastery of basic education skills |

Objective 7. Raise educational quality in the state. Objective 8. Achieve full satisfaction in school life. |

Note: The table does not aim to be exhaustive, see Annex B for a thorough analysis of the coherence between the SP and the SDP.

Source: Authors

Furthermore, the timeline given to opportunity areas and objectives may even be seen as contradictory in some cases. For instance, as it can be observed in Table 2.3, objective 6 of the Human and Social Development theme of the SDP requires the state of Nuevo León to achieve total coverage in education by 2021 (“Alcanzar la cobertura total en materia de educación”), while a prioritised opportunity area of the Strategic Plan only aims to increase coverage in elementary and pre-schools by 2030 (“Incrementar la cobertura en educación inicial y preescolar”).

In order to increase the coherence between the long-term Strategic Plan and the medium-term State Development Plan, Nuevo León could consider aligning the two plans in one single point or layer. For instance, the SDP’s objectives could be explicitly aligned to the SP’s prioritised opportunity areas or even fully harmonised, when relevant, as can be seen for example in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3. Example of coherence between the Strategic Plan and the State Development Plan

|

Opportunity areas of the Strategic Plan |

State Development Plan |

|---|---|

|

Human Development Commission |

Human and Social Development chapter |

|

Increase total coverage in education (ex-prioritised opportunity areas 1 and 2) |

Objective 6. Achieve total coverage in education |

|

Strengthen the scope and coordination of the third sector (CSOs, foundations and governmental actions). |

Not relevant |

|

Raise educational quality in the state |

Raise educational quality in the state |

Source: Authors

This practice can be seen clearly in other Mexican states. In Guanajuato, for example, strategic planning involves both horizontal and vertical coordination mechanisms to align the timelines and objectives of all planning instruments, from the national level (with the National Development Plan and the Sustainable Development Goal), to the state level (with the State Development Plan and the State Government Program), as is explored in Box 2.4. In order to make this alignment possible, Nuevo León could consider adopting methodological guidelines for the preparation of the next State Development Plan for 2022-2027, that require a clear theory of change to align the SDP’s objectives and indicators, to that of the Strategic Plan. Until the renewal of the State Development Plan, however, Nuevo León could consider relying on action plans to establish this link, as further explained in the following section.

Box 2.4. Alignment between different state programmes in Guanajuato

In Guanajuato, the State Government Programme (“PG 2018-2024”) is an important strategic tool guiding the executive’s actions. This document also aims at aligning the state’s development strategy with other national and international planning instruments, such as the National Development Plan (NDP) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

For instance, all the 17 SDGs correspond to one or several objectives of the PG 2018-2024. In order to facilitate coordination with the federal government, the PG 2018-2024’s structure is also consistent with Mexico’s National Development Plan. Finally, the Program’s objectives are aligned with those in the State Development Plan “Guanajuato 2040” which is another major planning instrument aimed at promoting the long-term development of the state. The two planning instruments have similar strategic areas and objectives. For instance, one of the SDP’s long-term objectives is to fight poverty while the government programme has three related midterm objectives: improve poor families’ situations, increase food safety and strengthen social links.

Therefore, strategic planning in Guanajuato involves both horizontal and vertical coordination mechanisms by aligning the timelines and objectives of the different planning instruments. Such coherence can help the state executive to ensure that spending and implementation efforts are focused on well-defined policy objectives with greater impact.

Source: Adapted from Estado de Guanajuato (2019[15]), Programa de Gobierno 2018-2024 [State Government Program 2018-2024], https://guanajuato.gob.mx/PDGv23.pdf.

The Strategic Plan and the State Development Plan can be articulated with an action plan

Although breaking the Strategic Plan’s opportunity areas into strategic lines and initiatives suggests that the council has identified actions to implement their long-term goals, neither strategic lines nor initiatives are directly linked to the use of inputs (human, financial or material resources) with clear responsibility for their implementation. Moreover, there is no clear methodology for designing strategic projects, priority programmes or assessing their progress. As such, the Strategic Plan does not contain a clear action plan for its implementation as is consistent with long-term strategic planning.

International good practice recommends that an action plan be prepared together with the development of any strategy, in order to clarify and identify the inputs and processes that will be used for its implementation (OECD, 2018[2]). In fact, the Strategic Plan itself (chapter 5 “Implementation and monitoring”) suggests that, in order to be implemented, the Plan should be associated with a detailed action plan clarifying deliverables, deadlines, resources and lines of responsibility; an action plan is a means to achieve change.

The development of such an action plan, which is crucial to assessing the feasibility of a Plan, could potentially be the responsibility of the state public administration, as is usually the practice in OECD countries. As such, the action plan would be a list of activities and measures, linked to the use of inputs (human, financial or material resources), that will be mobilised to produce certain outputs (OECD, 2018[2]). This implies that the action plan does not need to propose new actions, but rather explain how, and by when, government activity and resources will achieve the output objectives of the State Development Plan and how they will ultimately contribute to the achievement of the Strategic Plan.

As such, the action plan would serve to detail the implementation pathways for the overlapping objectives/priority opportunities areas of the SDP and the SP. This would facilitate the monitoring of these pathways by the state public administration and their evaluation by the council. Therefore, it would be useful for the council to consider evaluating the implementation of the action plan, in order to collect evidence on how the government is endeavouring to mobilise resources in pursuit of the Strategic Plan’s objectives.

Furthermore, as an action plan can easily be updated, it would enhance the adaptability of the Strategic Plan to political and economic developments. This would therefore address another concern raised by several stakeholders, namely that the implementation of the Plan’s long-term goals has been impacted by short-term political circumstances (budgetary restrictions, changes in the political agenda).

Put differently, devising an action plan – in conjunction with the alignment of the Strategic Plan and the State Development Plan – would allow Nuevo León to ensure that its actions and priorities across the different analysis and time horizons are harmonious (see Table 2.4). In particular, the action plan, would enable short-term decision-making in Nuevo León (for e.g. executive actions) to reflect the priorities of its long and medium-term planning instruments.

Table 2.4. Analysis horizons: strategic and decision-making needs by planning timeframe

|

Analytical needs |

Characteristics |

Requirements |

Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Foresight (long term: > 10 years) |

Anticipation of, and preparation for, both foreseeable and disruptive/discontinuous trends, including future costs in today’s decisions |

Continuous scanning and consultation; pattern recognition; analysis of “weak signals”; future studies; consensual views |

Future reporting (e.g. on climate change); horizon scanning; long-term budget estimates; scenario planning |

|

Strategic planning (medium term: 3-10 years) |

Anticipation of, and preparation for, foreseeable trends; prioritisation; including future costs in today’s decisions; risk management |

Analysis of historical and trend data; comparable information and analysis across government; consultation on values and choices |

Government Programme; medium-term budget frameworks; workforce planning; spatial and capital investment planning; innovation strategies |

|

Decision making (short term: 1-2 years) |

Responsiveness; rapidity; accountability; ability to determine at what level decisions need to be taken |

Quick access to relevant information and analysis; capacity for reallocation; overview of stakeholder preferences |

Executive action; annual and mid-term budgets; crisis response |

Source: Adapted from (OECD, 2010[16]), Finland: Working Together to Sustain Success, OECD Public Governance Reviews,

OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264086081-en.

The articulation of the Strategic Plan and the State Development Plan with an action plan can support a coherent whole-of-government framework to manage strategic planning and development priorities in Nuevo León. In this regard, OECD country experiences are quite instructive. For example, as detailed in Box 2.5, Poland’s national development management framework is a good case study for eliminating redundancies and ensuring coherence between instruments across the different analysis horizons.

Box 2.5. Poland’s strategic whole-of-government development management framework

The Act on Development Policy (2006) was the first step in the evolution of Poland’s development management framework. This legislation not only established an institution to define and co-ordinate the country’s development policy, but also used a series of interconnected action plans to deliver sustained and balanced national development, as well as to ensure regional socio-economic cohesion.

This legislation – and the entire development management framework – was informed by a stocktaking exercise of Poland’s development strategies and programmes between 1989 and 2006. The government determined that over this period, the country’s Council of Ministers had adopted no less than 406 national strategies (with varying scopes and degrees of implementation), of which only 120 strategies remained relevant. Thus, in 2009, the country passed the Development Strategy Rearrangement Plan, which reduced and rearranged the number of binding strategies. All strategic initiatives developed since 2010 adhere to this new system.

Currently, Poland’s long-term development strategy and vision is detailed in “Poland 2030: The Third Wave of Modernity – A Long-Term National Development Strategy”. The implementation of this long-term vision is guided by its medium-term strategic framework (Medium-Term National Development Strategy 2020), which outlines nine integrated strategies and the corresponding actions and activities.

Poland’s experience in managing its development and strategic planning showcases how shifting from a limited sector-based approach to strategy-setting to an integrated approach can help harness synergies and optimise public policies.

Source: Source: Adapted from OECD (2016[17]), OECD Public Governance Reviews: Peru Integrated Governance for Inclusive Growth, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265172-en.

A clear need to link strategic planning with budgeting

In addition to the aforementioned planning instruments, the state budget is a vital consideration for identifying pathways for implementation, as well as ensuring policy coherence. First, since the implementation of a strategy relies on the proper calculation of the required resources, as well as appropriate budgeting and allocation of such resources, the strategic objectives should be well-reflected in annual and medium-term budgeting documents (Vági and Rimkute, 2018[18]). Second, as per OECD recommendations, budgeting processes ought to be governed by principles like performance-based budgeting. Integrating these principles with strategic planning instruments (and their initiatives) is crucial for the mainstreaming of these practices, and thus, ensuring policy coherence across government.

The 2015 OECD Recommendation on Budgetary Governance (see Box 2.6) indicates that budgets should be closely aligned with the medium-term strategic priorities of government. Structuring and organising budget allocations with medium-term considerations in mind ensures that the budget extends beyond the traditional annual cycle (OECD, 2018[19]). Thus, effective medium-term budgeting helps create clearer links between budgets, plans and policies, and is a vital part of reducing uncertainty for policy-making (OECD, 2018[19]). Notably, medium-term budgeting can promote the following:

greater assurance to policy planners about multi-year availability of resources

identification of appropriate medium-term goals against which resources should be aligned (OECD, 2018[19]).

Box 2.6. Principle 2 of the OECD Recommendation on Budgetary Governance

Closely align budgets with the medium-term strategic priorities of government, through:

Developing a stronger medium-term dimension in the budgeting process, beyond the traditional annual cycle

Organising and structuring the budget allocations in a way that corresponds readily with national objectives

Recognising the potential usefulness of a medium-term expenditure framework (MTEF) in setting a basis for the annual budget, in an effective manner which:

has real force in setting boundaries for the main categories of expenditure for each year of the medium-term horizon

is fully aligned with the top-down budgetary constraints agreed by government

is grounded upon realistic forecasts for baseline expenditure (i.e. using existing policies), including a clear outline of key assumptions used

shows the correspondence with expenditure objectives and deliverables from national strategic plans

includes sufficient institutional incentives and flexibility to ensure that expenditure boundaries are respected

Nurturing a close working relationship between the Central Budget Authority (CBA) and the other institutions at the centre of government (e.g. prime minister’s office, cabinet office or planning ministry), given the inter-dependencies between the budget process and the achievement of government-wide policies

Considering how to devise and implement regular processes for reviewing existing expenditure policies, including tax expenditures, in a manner that facilitates the alignment of budgetary expectations with government-wide developments.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2015[20]), Principles of Budgetary Governance.

In Nuevo León, public expenditure is governed by the Expenditures Law for the State of Nuevo León (Ley de Egresos del Estado de Nuevo León). This legal document aims to regulate the allocation, execution, control and evaluation of public spending on an annual basis (OECD, 2018[21]). The 2020 Expenditures Law was signed into effect on December 20, 2019. Furthermore, the Law for the Financial Management of the State of Nuevo León (Ley de Administración Financiera para el Estado de Nuevo León) regulates financial management and financial planning of state and parastatal entities in Nuevo León (OECD, 2018[21]).

The link between government expenditure and strategic planning in Nuevo León is governed by article 3.XIV of the Strategic Planning Law, which dictates that strategic planning shall be based on, among other factors, the link with the expenditure budget so that government expenditure is related to the fulfilment of the Strategic Plan and the State Plan. To do so, article 28 of the regulations of the Strategic Planning Law declares that annual public expenditure should be linked to strategic planning using a programmatic budgetary structure. This necessitates the inclusion of classification categories that explicitly link the instruments of the strategic planning process (understood to be both the Strategic Plan and the State Development Plan as per article 15 of the regulations of the Strategic Planning Law) with public resources.

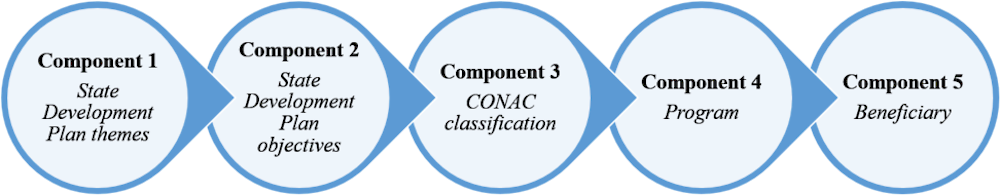

In practice, budgetary programmes follow a classification framework that specifies their relationship to the State Development Plan; this framework does not map each budget programme to a component of the Strategic Plan (see Figure 2.7). Whilst it is often challenging for long-term plans to contain precise budgetary envelopes as they focus on the end of the policy-value chain (OECD, 2018[2]), and while it is not necessarily wrong that in a specific year a long-term objective is not explicitly financed, the conceptual framework linking objectives to the budgetary programmes should be clearer.

Furthermore, article 25 of the regulations of the Strategic Planning Law states that entities of the state public administration must prepare annual operational programmes. These programmes serve as the basis of the preliminary draft of the annual budget for each entity. They contain the activities to be carried out during the year by the state public administration to achieve the objectives of the State Development Plan, as well as sectoral, special programmes (Article 21 of the regulations of the Strategic Planning Law). It is clear, however, that these operational programmes are not currently mapped to the objectives of the Strategic Plan.

Figure 2.7. Classification code components of budgetary programmes

Note: CONAC stands for Consejo Nacional de Armonization Contable

Source: OECD questionnaire I (2019[22]).

Performance budgeting is in its very early stages in Nuevo León

Performance budgeting is defined as “the systematic use of performance information to inform budget decisions, either as a direct input to budget allocation decisions or as contextual information to inform budget planning, and to instil greater transparency and accountability throughout the budget process, by providing information to legislators and the public on the purposes of spending and the results achieved” (OECD, 2018[23]). This concept is ingrained in the 2015 Recommendation on Budgetary Governance (Principle 8, see Box 2.7), which states that countries should “ensure that performance, evaluation and value for money are integral to the budget process.”

Box 2.7. Principle 8 of the OECD Recommendation on Budgetary Governance

helping the parliament and citizens to understand not just what is being spent, but what is being bought on behalf of citizens – i.e. what public services are actually being delivered, to what quality standards and with what levels of efficiency;

routinely presenting performance information in a way which informs, and provides useful context for, the financial allocations in the budget report; noting that such information should clarify, and not obscure or impede, accountability and oversight;

sing performance information, therefore, which is (i) limited to a small number of relevant indicators for each policy programme or area; (ii) clear and easily understood; (iii) allows for tracking of results against targets and for comparison with international and other benchmarks (iv) makes clear the link with government-wide strategic objectives;

evaluating and reviewing expenditure programmes (including associated staffing resources as well as tax expenditures) in a manner that is objective, routine and regular, to inform resource allocation and re-prioritisation both within line ministries and across government as a whole;

ensuring the availability of high-quality (i.e. relevant, consistent, comprehensive and comparable) performance and evaluation information to facilitate an evidence-based review;

conducting routine and open ex ante evaluations of all substantive new policy proposals to assess coherence with national priorities, clarity of objectives, and anticipated costs and benefits;

taking stock, periodically, of overall expenditure (including tax expenditure) and reassessing its alignment with fiscal objectives and national priorities, taking into account the evaluation results; noting that for such a comprehensive review to be effective, it must be responsive to the practical needs of government as a whole (see also recommendation 2 above).

Source: Adapted from the OECD (2015[20]), OECD Recommendation on Budgetary Governance, http://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/principles-budgetary-governance.htm.

In Mexico, performance-based budgeting was introduced in 2006, through the Fiscal Responsibility Law, which outlined the gradual implementation of a performance-based budgeting system (Presupuesto basado en Resultados, PbR), aimed at defining, for each budgetary programme, clear objectives to be achieved. In 2007, this system was also complemented by a system of monitoring and evaluation of the social impact of programmes (Sistema de Evalución del Desempeño, SED). The federal performance-based budgeting system was also extended to the state level in 2008. See Box 2.8 for more information on the performance-based budgeting system in Mexico.

In Nuevo León, performance-based budgeting is reflected in several normative instruments. Specifically, the executive branch of the state of Nuevo León issued the General Guidelines for the Consolidation of Results-Based Budget and the Performance Evaluation System in 2017. The intent of these guidelines is to institutionalise a results-based budgeting system with tools such as performance indicators linked to budgetary programmes, logical framework methodology to organise objectives in a causal way, etc.

The concept of performance-based budgeting is reflected in the strategic planning instruments of Nuevo León, notably the State Development Plan. To that end, article 16 of the Strategic Planning Law defines the State Development Plan as not only a medium-term planning instrument, but also a source of guidance on results-based management and results-based budgeting. The State Development Plan is also cited in the General Guidelines for the Consolidation of Results-Based Budget and the Performance Evaluation System. In fact, the preamble of the guidelines recalls theme 2 of the State Development Plan, Effective and Efficient Government, which notes the need to implement innovative mechanisms to ensure that services are provided with high quality standards, in the shortest time and with the least amount of resources possible.

Box 2.8. Result-based budgeting in Mexico

Result-based budgeting (RBB) attempts to link allocations to the achievement of specific results, such as outputs and outcomes of government services. In Mexico, the 2007 fiscal reform helped the government transition from an input-driven budget model to a result-based budget model. The law also stressed the need to develop a Performance Evaluation System (SED), defined as a set of methodological elements that allow an objective evaluation of programs performance. The main coordinating actors of this RBB system include the CONEVAL and the Secretary of Finance and Public Credit (SHCP).

Several elements contribute to the implementation of a RBB process in Mexico. Firstly, budget programmes are linked to the achievement of the National Development Plan and the sectoral plans objectives. This is to ensure that public spending identifies the contribution to national priorities. The structure of the Plan and Results-based Budget policies have also facilitated the identification of the strategies that drive the achievement of the SDGs, both at the level of sectoral and budgetary programs (OECD, 2018[56]).

Moreover, the federal government has an online Budget Transparency Portal which presents performance information in a way that can easily be interpreted by users. It also provides several open datasets that can be used by analysts and researchers. This contributes to greater transparency in the execution of public programmes.

However, the articulation of performance results and actual budgeting remains an area of improvement. Indeed, performance information is mostly used as a tool for performance management and accountability, rather than as a tool for resource allocation. The 2019 OECD report on Budgeting and Public Expenditures highlights that “not having a formal mechanism to consider evaluation findings in the resource allocation process is a key limitation for using evaluation evidence in the budget process” (OECD, 2019[57]).

Source: Adapted from OECD (2018[23]), OECD Best practices for performance budgeting, https://one.oecd.org/document/GOV/PGC/SBO(2018)7/en/pdf ; OECD (2019[24]), Budgeting and Public Expenditures in OECD countries 2019 https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/budgeting-and-public-expenditures-in-oecd-countries-2018_9789264307957-en ; Government of Mexico, www.transparenciapresupuestaria.gob.mx/.

Furthermore, the Strategic Planning Law also alludes to a performance budgeting approach in the evaluation of the State Development Plan and the Strategic Plan. In particular, the Law mandates that an annual report be sent to the state congress that assesses the relationship between public expenditure and the impact on economic and social development indicators pertaining to the objectives of both the State Development and the Strategic Plan (Article 26).

However, in practice, implementing performance-based budgeting to produce evidence on how the state’s funds contribute to achieving policy goals set out in the Strategic Plan (as well as the State Development Plan) is currently infeasible. In addition to the absence of classification codes connecting budgetary programmes with the objectives of the Strategic Plan, the performance indicators used in the General Guidelines for the Consolidation of Results-Based Budget and the Performance Evaluation System are not necessarily the same as the indicators identified in the State Development Plan and the Strategic Plan. In fact, the latest 2020 comparative data on Mexican states shows that Nuevo León went from being below to above the national average in the implementation of a performance-based budgeting system3

The implementation of the Strategic Plan is also constrained by historic fiscal limitations of subnational governments

Linking the budget to strategic planning may also be hindered by the limited budgetary autonomy of subnational governments (SNG). According to OECD literature, this limited autonomy can be explained by three main factors. Firstly, subnational governments have a smaller revenue base and a high reliance on transfers from central governments; this is compounded by the fact that SNGs have less autonomy in changing tax rates or tax bases. Secondly, a substantial share of SNG expenditure is mandatory under federal regulations. Finally, SNGs are constrained by more stringent fiscal rules; they have less flexibility in using debt to adjust their budgets. As such, any decrease in their revenue base is followed by a decrease in expenditure (OECD, 2015[25]).

Whilst it is often challenging for long-term plans to contain precise budgetary envelopes as they focus on the end of the policy-value chain (Máttar and Cuervo, 2017[9]), and while it is not necessarily wrong that in a specific year a long-term objective is not explicitly financed, the conceptual framework linking objectives to the budgetary programmes should be clearer. In the case of the Strategic Plan, prioritised opportunity areas / strategic objectives can be clearly linked to the budget through the State Development Plan), when relevant.

Recommendations

This assessment of the Strategic Plan methodology has led to the following recommendations, which are offered for consideration by the government authorities and the council, who are invited to:

Simplify the Strategic Plan in order to recentre it around impact and outcome level objectives.

Remove strategic lines, initiatives and strategic projects from the Plan. In order to simplify the plan and recentre it around impact/outcome level objectives, keep only priority opportunity areas, their targets (including medium-term milestones when relevant, and systematic long-term targets) and indicators. For each thematic area, these elements should follow the diagnosis and prioritisation exercises set out by each commission.

Conversely, consider including some of the elements previously mentioned in the Strategic Plan (strategic lines, initiatives and projects) in the action plan, if relevant (see section 4.3 for further discussion on the action plan).

Review prioritised opportunity areas so that they consistently correspond to long-term outcome/impact level objectives. Consider also using the SMART model in undertaking this exercise.

Strengthen the problem analysis/diagnosis phase: integrate in each commission’s diagnosis phase the conclusions of a systematic review of the evaluation of previous plans and/or key policies in the relevant thematic, and consider a more strategic use of reliable data for objective/target setting.

Reduce the number of priority opportunity areas in the Plan: This would help ensure greater harmonisation of the number and nature of prioritised opportunity areas assigned to each commission of the council and attribute a range of priority opportunity areas to each commission (e.g. no more than three), if the government and the council consider splitting the Human Development Commission (HDC) into three commissions. To this end, Nuevo León can consider:

Complementing the existing prioritisation methodology (impact and feasibility) with an analysis and comparison of the opportunity areas under a logic model and/or theory of change, in order to explore existing sequencing and trade-off among them. This idea will be further explored in the following section on the structure of the Plan (section 3.2). This prioritisation process should also be based on the revised diagnosis, as well as the results of the latest citizen consultation process. This prioritisation exercise could also be developed with the support of the Finance Commission of the council, the Executive Office of the Governor, and possibly the Investments Unit of the Government to ensure credible pathways for implementation in the future, so that resources can be clearly identified.

Prioritising only the opportunity areas that can be measured by an indicator (see section 5).

Identifying other priority opportunity areas on the topic of good and effective governance in order to improve the performance of the council and the public administration.

Clearly communicate, in the Plan itself, the reasons behind the selection of the priority opportunity areas in order to ensure support within and outside the administration. This could include relabelling the “Priority Opportunity Areas” as “Strategic Objectives”.

Clarify the priority opportunity areas under each commission, for instance by including, at the end of the Plan, a table summarising the priority opportunity areas monitored by each commission.

The following four recommendations are put forward to increase the coherence of planning, aligning, policy priorities and identifying pathways for their implementation

Clarify and communicate the coherence between the Strategic Plan and the SDGs. Possibly consider communicating, near the vision statement, that the goal of the Plan is to translate the forward-looking vision of the Sustainable Development Goals into the specific circumstances of the state of Nuevo León. It would be possible to clarify the ways in which the Strategic Plan contributes to the SDGs by:

including a table demonstrating the alignment of the Plan’s opportunity areas with the SDGs targets

ensuring that the prioritised opportunity areas refer to SDGs at least once, as recommended by the Presidency.4

Clarify the responsibilities of the commissions in regard to overseeing the implementation of the SDGs. The council could consider systematically including a section on how the opportunity areas have contributed to the achievement of the SDGs at a local level, in the evaluation reports for each thematic area.

Clarify the ways in which the State Development Plan contributes to pursuing the goals of the longer term Strategic Plan. There is a possibility for greater alignment, or even harmonisation, of some of the opportunity areas (Strategic Plan) with the objectives (State Development Plan). In this scenario, the State Development Plan would focus on medium-term outcome level objectives and below (objectives), while the Strategic Plan is focused on longer-term outcome level objectives (prioritised opportunity areas).

The manual for the elaboration of the SDP should contain a methodology to relate the medium term objectives of the SDP with the long-term objectives of the Strategic Plan. Nuevo León could consider using a theory of change to make this link explicit.

This would benefit from rephrasing both priority opportunity areas and objectives to fit a SMART framework.

For each linked/ harmonised prioritised opportunity area and objective, it would be good to set a long-term (2030) target and a medium term (2021) target (or milestone). Figure 2.8 highlights how the objectives and indicators of the Strategic Plan and the State Development Plan could be linked. In the end, Nuevo León would follow the example of many other Latin American and Caribbean countries, as of the 20 long-term plans present in the region, more than half were articulated through medium-term plans, as shown by CEPAL (Máttar and Cuervo, 2017[9]).

Figure 2.8. Proposed alignment between the Strategic Plan and the State Development Plan

Source: Authors based on government of Nuevo León input

Until a new State Development Plan can be developed, create an action plan for each opportunity area of the Strategic Plan, taking into consideration the objectives, strategies and lines of action of the State Development Plan.

The state of Nuevo León could therefore consider developing an action plan at the same time as it revises its Strategic Plan, in order to assess the feasibility of prioritised opportunity areas in light of existing and foreseen resources and available tools. The action plan should be cohesive with the Strategic Plan (which focuses on long-term outcomes), as well as the State Development Plan (which focuses on medium-term outcomes and outputs).

The action plan could serve to clarify how the government’s existing budgetary programmes and investment projects, as well as institutional activity, will contribute to the achievement of the State Development Plan and the Strategic Plan’s objectives (when relevant) by setting clear deadlines and deliverables. The action plan should therefore not propose new instruments, resources or institutions but rather focus the existing instruments around the objectives of the State Development Plan (SDP) and the opportunity areas of the Strategic Plan (SP). The action plan would benefit from being short term (1 to 3 years).

Each commission’s action plans should be devised by the executive in coordination with the council’s technical bodies, the Finance Commission and the body in charge of coordinating the implementation of the Plan within the executive (for instance the Executive Office of the Governor). These three bodies (the council’s technical staff, the government and the Finance Commission) should play a strategic role in providing guidance to the commissions for the elaboration of the action plans. The council and the government could agree, for instance, on a common structure or format for these Actions Plans, and each commission could engage in a constructive dialogue with the Secretariats to flesh out the action plan for each priority opportunity area. This could include identifying a main interlocutor within the administration responsible for preparing the monitoring reports for each priority opportunity area.

Government reporting on the implementation Action Plan should contribute to producing evidence for the commissions’ monitoring and evaluation exercises. In fact, given the nature of the action plan, this reporting should produce input, process and output evidence that could contribute to better monitoring the achievement of the outcome objectives set out in the Strategic Plan. As such, each commission of the council would monitor the action plan for its thematic area.

Create greater alignment between the Strategic Plan and the state budget, through ensuring coherence with the State Development Plan (See Table 2.5). This could be addressed by including a methodology to relate the medium term objectives of the SDP with the long-term objectives of the Strategic Plan, in the manual for the elaboration of the SDP. Nuevo León could also consider using a theory of change to make this link explicit.

Table 2.5. Example of alignment between priority opportunity areas (SP)/Objectives (SDP) and budgetary programmes

|

Priority opportunity area/ Objective |

Strategy (State Development Plan) |

Budgetary programme |

|---|---|---|

|

Incrementar la cobertura en educación inicial y preescolar. |

Mejorar la infraestructura, el equipamiento y la conectividad en las escuelas |

207. Infraestructura física para el sector educativo. |

Source: Authors based on the document “Matriz Alineación PED ODS”

References

[1] Council of Nuevo Leon (2019), Nuevo León Council | About us?, https://www.conl.mx/quienes_somos.

[10] Council of Nuevo León (2017), Análisis y replanteamiento de los ingresos, gastos y deuda del Estado de Nuevo León, Centro de investigación económica y presupuestaria.

[3] Council of Nuevo León (2016), “Strategic Plan for the State of Nuevo León 2015-2030”.

[15] Estado de Guanajuato (2019), Programa de Gobierno 2018-2024.

[6] Gobierno de Guanajuato (2018), “Plan Estatal de Desarollo Guanajuato 2040”.

[5] Gobierno de Jalisco (2013), Plan Estatal de Desarollo Jalisco 2013-2033.

[9] Máttar, J. and L. Cuervo (2017), Planificación para el desarrollo en América Latina y el Caribe: Enfoques, experiencias y perspectivas, http://www.cepal.org/es/suscripciones.

[14] Nuevo León Council (2017), “Creación de la Comisión Especial para la Puesta en Marcha de la Agenda 2030 del Desarrollo Sostenible en Estado Nuevo León”.

[24] OECD (2019), Budgeting and Public Expenditures in OECD Countries 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264307957-en.

[23] OECD (2018), OECD Best Practices for Performance Budgeting.

[21] OECD (2018), OECD Integrity Review of Nuevo León, Mexico: Sustaining Integrity Reforms, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264284463-en.

[19] OECD (2018), OECD Public Governance Reviews : Paraguay - Pursuing national development through integrated public governance.

[2] OECD (2018), Toolkit for the preparation, implementation, monitoring, reporting and evaluation of public administration reform and sector strategies: guidance for SIGMA partners, http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions. (accessed on 18 June 2019).

[11] OECD (2017), OECD Territorial Reviews: Morelos, Mexico, OECD Territorial Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267817-en.

[4] OECD (2017), Recommendation of the Council on Open Government, http://acts.oecd.orgRECOMMENDATIONPUBLICGOVERNANCE (accessed on 26 February 2020).

[17] OECD (2016), OECD Public Governance Reviews: Peru: Integrated Governance for Inclusive Growth, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264265172-en.

[20] OECD (2015), Principles of Budgetary Governance, https://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/principles-budgetary-governance.htm (accessed on 20 March 2020).

[25] OECD (2015), The State of Public Finances 2015 : Strategies for Budgetary Consolidation and Reform in OECD Countries., OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264244290-en.pdf?expires=1584971581&id=id&accname=ocid84004878&checksum=AC017CED2D74912E7F3BC30A30BB89F1.

[12] OECD (2012), Slovenia: Towards a Strategic and Efficient State.

[16] OECD (2010), Finland: Working Together to Sustain Success, OECD Publishing, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264086081-en.

[22] OECD questionnaire I (2019), OECD questionnaire “Towards a sound monitoring and evaluation system for the strategic plan of the state of Nuevo León 2015-2030”, sent to the Council and the state government of Nuevo León.

[7] Schumann, A. (2016), Using Outcome Indicators to Improve Policies: Methods, Design Strategies and Implementation, OECD Regional Development Working Papers,.

[13] State of Nuevo León (2018), Guía metodológica para la formulación del Plan Estatal de Desarrollo 2016 – 2021, http://www.nl.gob.mx/publicaciones/guia-metodologica-para-la-formulacion-del-plan-estatal-de-desarrollo-2016-2021 (accessed on 20 March 2020).

[8] UNDSG (2017), Theory of Change: UNDAF Companion Guidance, https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/UNDG-UNDAF-Companion-Pieces-7-Theory-of-Change.pdf.

[18] Vági, P. and E. Rimkute (2018), “Toolkit for the preparation, implementation, monitoring, reporting and evaluation of public administration reform and sector strategies GUIDANCE FOR SIGMA PARTNERS”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/37e212e6-en.

Annex 2.A. Alignment between the Sustainable Development Goals and the Strategic Plan

Annex Table 2.A.1. Alignment between the SDGs and the Strategic Plan’s priority opportunity areas

|

SDG Goals (Agenda 2030) |

Priority opportunity areas of the Strategic Plan (2015-2030) |

|---|---|

|

10. Eradicate extreme poverty with special emphasis on food security. (also on Goal 2) 11. Reduce urban poverty. (also on Goal 10) |

|

|

10. Eradicate extreme poverty with special emphasis on food security. (also on Goal 1) |

|

|

6. Education and early detection to prevent overweight, obesity and diabetes. 7. Ensure coverage and effective access of the population for priority health conditions. 8. Guarantee quality through an independent health commission that monitors standardized indicators and a professionalized health management. 9. Early detection and immediate attention for breast cancer and pelvic-uterine cancer. 20. Foster physical activity in schools. |

|

|

1. Increase coverage in early childhood and preschool education 2. Increase coverage and graduate efficiency rates in upper secondary education 3. Ensure mastery of basic education skills. 5. Implement programs for the professional development of teachers and administrators. 18. Incorporate quality artistic training in public basic education 19. Create programmes for reading, writing and artistic skills. |

|

|

12. Prevention of family and community violence. 13. Achieve women's labour and social equality. 24. Promote the gender perspective in government programmes, in educational programmes and in the labour market. |

|

|

32. Ensure water supply that guarantees the economic and social development of the state. |

|

|

33. Promote energy security and transition to low-carbon fuels |

|

|

4. Ensure the employability of youth. 36. Align the skills demanded by the productive sectors with those offered by educational institutions. 37. Promote employment formalization 38. Review the institutional framework to facilitate business creation and operation. |

|

|

34. Strengthen the integration of productive chains. 35. Promote the competitiveness and integration of MSMEs. |

|

|

11. Reduce urban poverty (also on Goal 1) |

|

|

17. Strengthen community and neighbourhood culture to generate social cohesion and citizen coexistence. 21. Increase public spaces for social physical activities. 30. Foster urban densification in the metropolitan area of Monterrey. 31. Increase the use of public transport and non-motorized means. (also on Goal 13) |

|

|

N/A |

|

|

29. Improve air quality 31. Increase the use of public transport and non-motorized means. (also on Goal 11) |

|

|

N/A |

|

|

N/A |

|

|

39. Strengthen technology and intelligence systems. 40. Promote the prevention of high frequency and high impact crimes. 41. Improve technical training and equipment of the police force 42. Reduce the time for judicialised and non-judicialised cases 43 Ensure control in prisons |

|

|

14. Strengthen the scope and coordination of the third sector (CSO, foundations and governmental actions). 26. Promote citizen empowerment 27. Strengthen state programmes for citizen participation programmes 28. Strengthen citizen participation programmes at the municipal level |

Source: Authors based on the Strategic Plan 2016-2021 and the Sustainable Development Goals 2030

Annex 2.B. Linkages between the State Development Plan and the Strategic Plan’s opportunity areas

Annex Table 2.B.1. Alignment between the Strategic Plan’s priority opportunity areas and the State Development plan

|

Opportunity areas of the strategic plan |

State development plan |

|---|---|

|

1 Increase coverage in early childhood and preschool education |

Human and Social Development Objective 6. Achieve total coverage in education. |

|

2 Increase coverage and terminal efficiency in upper secondary education |

Human and Social Development Objective 6. Achieve total coverage in education. |

|

3 Ensuring mastery of basic education skills |