Norway’s high rate of vaccination has helped limit the impact of COVID-19 on the population and economy. GDP per capita remains among the highest in the OECD and output growth is expected to be solid over the next two years. Nevertheless the country faces challenges to sustain its strong socio-economic outcomes. This chapter looks at the increases in consumer-price inflation, Norway’s ever more expensive housing and the rising pressures on government budgets. It also examines how to strengthen labour force participation and productivity, as well as how to deliver on green transition.

OECD Economic Surveys: Norway 2022

1. Key Policy Insights

Abstract

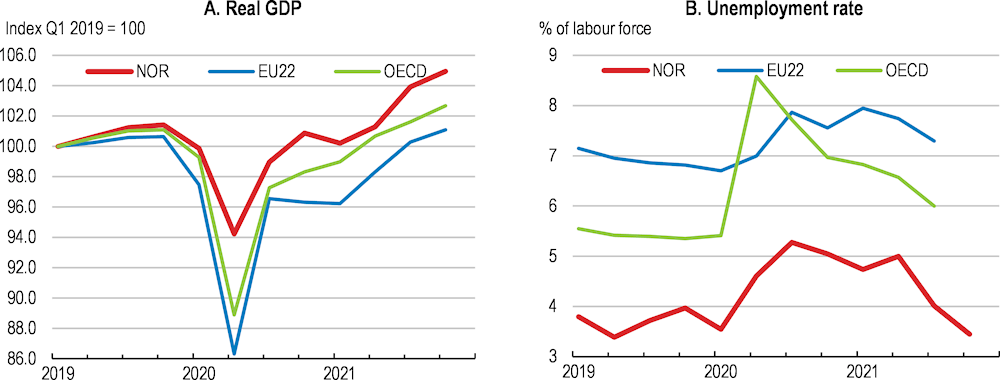

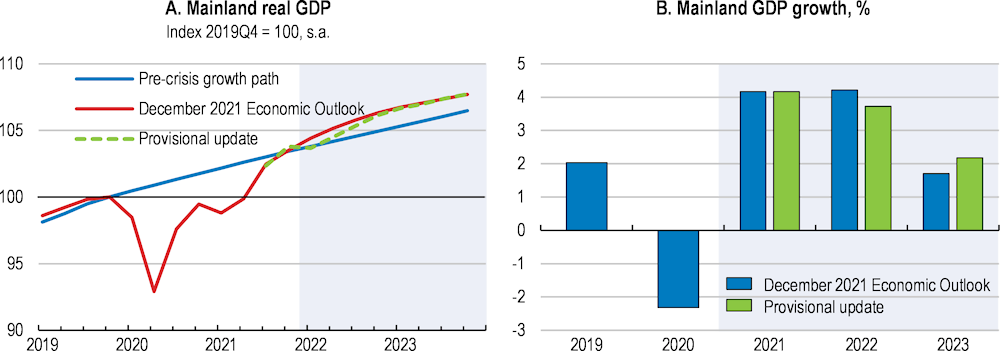

Norway has been more successful than many countries in limiting the spread and the health impact of COVID-19. Furthermore, the downturns in the economy during the pandemic have been comparatively mild (Figure 1.1). Substantial fiscal and monetary policy support has helped households and businesses through the crisis. As elsewhere, vaccination has been key to reopening of the economy. Following a short downturn due to the Omicron wave, the level of economic output will run slightly above trend over the next two years. Norway’s policymakers can now principally focus on ensuring macroeconomic stability in the wake of recovery and on addressing structural challenges.

Fiscal support during the pandemic has brought necessary relief to businesses and households and generated non-oil deficits considerably above the long-term guideline set by Norway’s fiscal rule (Figure 1.2). Phase out of most extraordinary measures was almost completed when the Omicron wave hit and renewed temporary measures were introduced. However, from spring 2022, fiscal spending is once again expected to return to more sustainable territory, below the guideline value in Norway’s fiscal rule. As in many other countries, headline consumer-price inflation has been pushed up significantly; in Norway, mainly due to large increases in electricity prices. Housing in Norwegian cities has become still more expensive with a new surge in prices during the pandemic (Figure 1.2). This has further raised risks to macro-financial stability from mortgage debt.

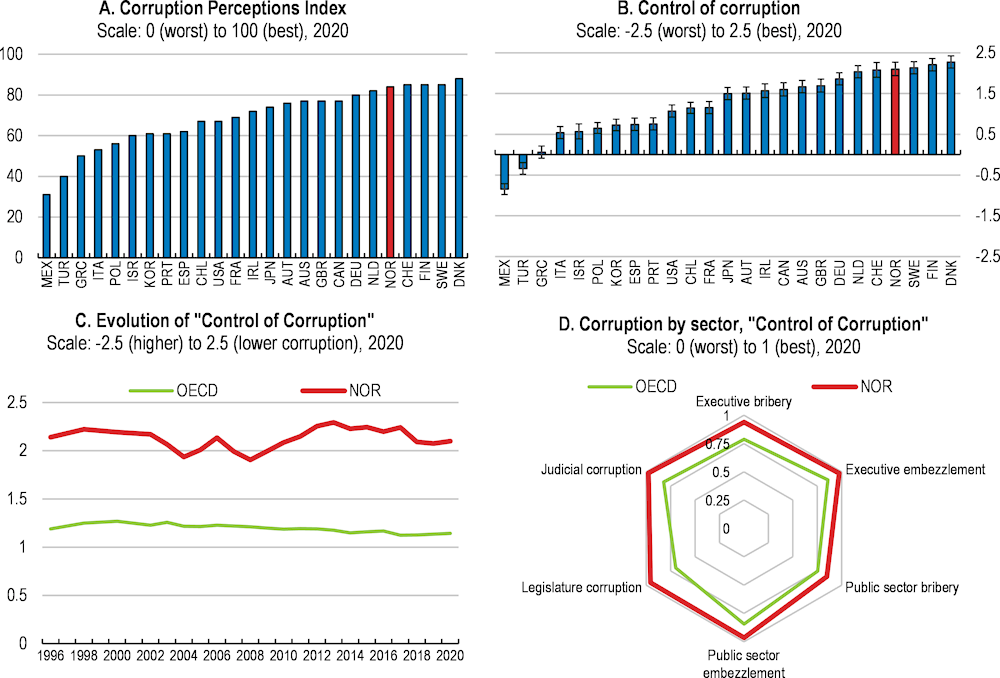

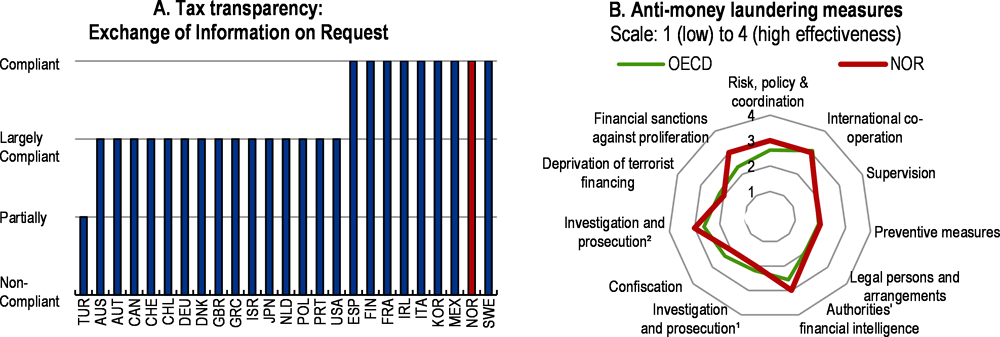

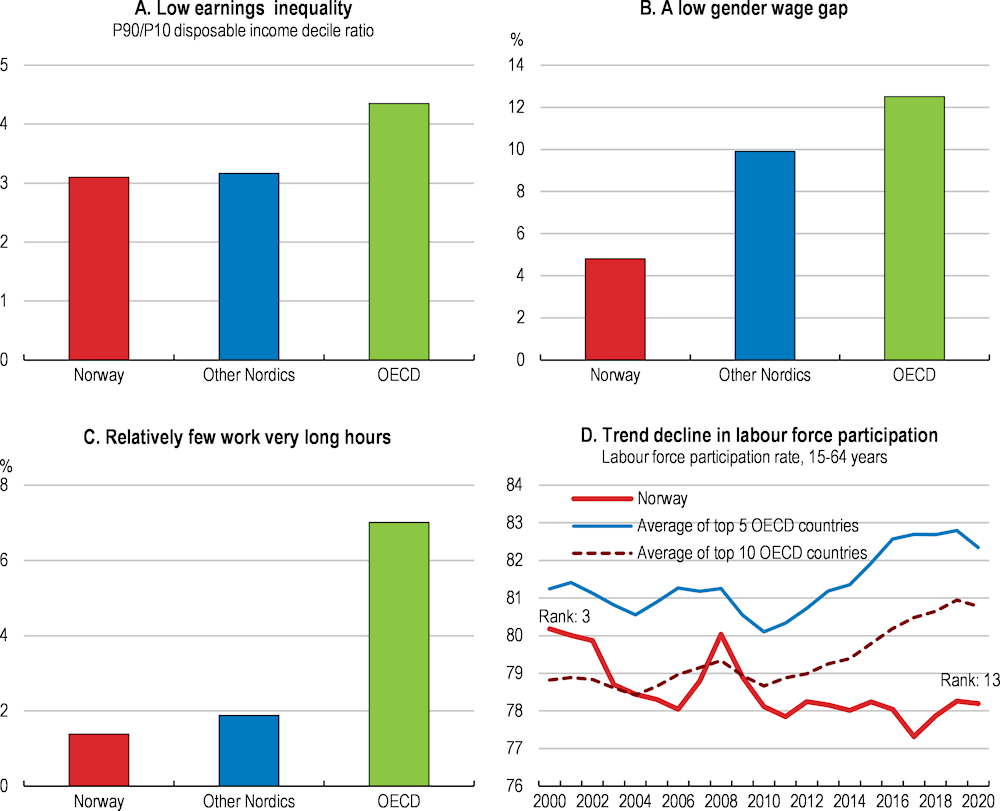

Norway continues to have good outcomes on many economic and social dimensions. GDP per capita remains among the highest in the OECD. Also, the country is broadly successful in its prioritisation of low inequality and the universal provision of core public services, including health and education. The gap between the highest and lowest incomes is among the smallest in the OECD area and rates of poverty are low. The gender wage gap is small. Norway generally scores well in subjective indicators of well being. Furthermore, survey data suggest Norway has among the highest levels of trust in the civil service and in government in comparison with other OECD countries.

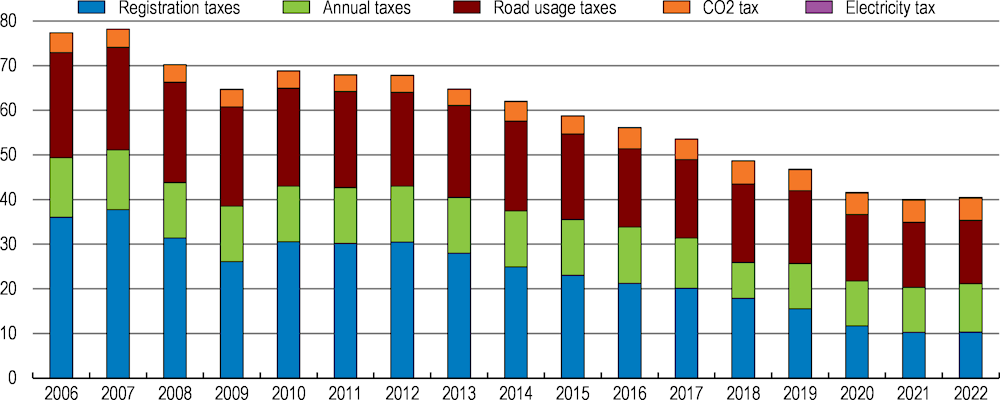

Figure 1.1. Norway’s pandemic output and employment losses have been comparatively small

However, there are challenges in ensuring Norway’s good outcomes are sustained amid post-pandemic economic adjustment, continued population aging and the greater urgency in tackling climate change. Labour force participation needs to increase to ensure the high levels of employment that are a key pillar of Norway’s socio-economic model. Twenty years ago, Norway’s labour force participation rate was around one percentage point below the average of the top-five OECD participation rates. In 2019 it was around four percentage points below (Figure 1.2). Trend productivity growth has been picking up but remains below the rapid growth of the early 2000s (Figure 1.2). Higher private-sector productivity growth is needed to help businesses remain competitive. Improved public-sector productivity can strengthen the quality and efficiency of public services. The house-price surge has made it harder for young and low-income households to save for a deposit, weakening homeownership accessibility. Many low-income households devote a substantial proportion of their income to rents. Meanwhile, economic activity needs to adjust to obtain faster decline in net greenhouse-gas emissions; Norway is committed to approximately halving net emissions from current levels by 2030 and to achieving very low gross emissions by 2050 (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Norway faces challenges in government budgeting, house prices, labour-force participation, productivity and greenhouse gas emissions

1. The 3% deficit path is the deficit implied by the 3% rule for wealth fund spending. This measure of the structural non-oil deficit includes the additional spending from discretionary measures to support the economy during the COVID-19 pandemic, but not the effect of automatic stabilisers.

2. Labour productivity for the OECD is measured as output per worker instead of per hour worked.

3. Projections under current implemented policies do not include reductions that are intended via participation in the EU-ETS. Norway’s emissions targets are in “gross” terms, meaning notably that the CO2 absorption from forestry is not included.

Source: Ministry of Finance, National Budget 2022; Calculations based on Real Estate Norway (Eiendom Norge) data; OECD (2022), Analytical house prices database; OECD (2021), Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database); OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook (database); and Climate Action Tracker, Country Assessments 2020 - http://climateactiontracker.org.

The main messages of this Survey are:

Sustained economic recovery from the pandemic is increasingly assured, despite setback due to the Omicron wave. Widespread vaccination in Norway has reduced the impact of COVID-19 on the economy. Withdrawal of monetary stimulus should continue. Reduction of fiscal stimulus should recommence as health conditions improve. Tax and public spending policies need to create room for new initiatives while remaining within the fiscal rule. A close watch on price and cost developments is needed given the sharp price increases in recent quarters.

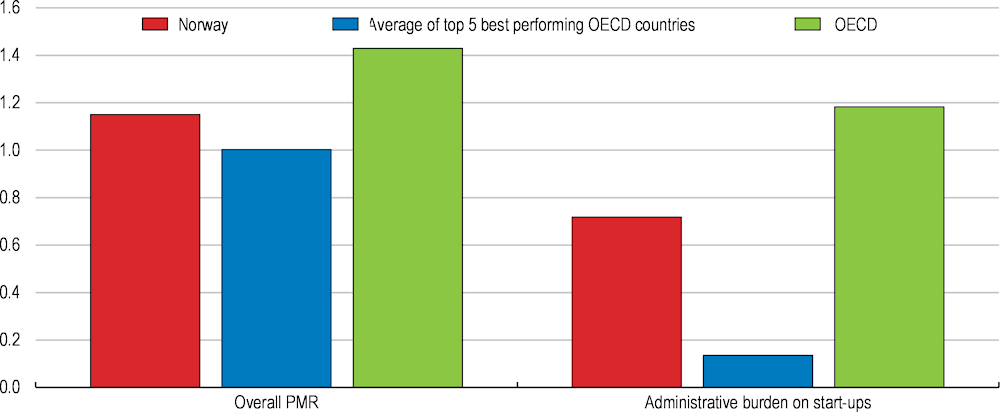

Structural policy should focus more fully on ensuring higher levels of productivity and employment, and on green transition. Insolvency processes for business require attention to help boost productivity growth. Further reduction in disincentives to remain in work, notably in sickness leave compensation and disability benefit, would help to boost employment. Climate change policy is sound on many fronts, however additional action is needed to ensure a large decline in emissions.

Improving housing affordability requires enabling the construction sector to respond faster to changes in demand and ensuring a good level of targeted support to vulnerable low-income households. Demand for home buying needs to be re-balanced through reducing tax biases favouring owner-occupied housing over investments in other assets.

Box 1.1. The new coalition government’s economic policies

A new coalition government is in office following the September 2021 election. It comprises the Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet, AP) and the Centre Party (Senterpartiet, Sp) whose origins lie in representing Norway’s rural communities and farmers. The Labour Party has 48 seats and the Centre Party 28, so the coalition has 76 seats, falling short of a majority (85 seats are required for a majority in the 169 seat parliament). The Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti, SV) (13 seats) is likely to play an important role supporting the government.

The new government is prioritising distributional, regional and climate policies. Themes of the government’s economic policy agenda include:

Increasing the tax burden born by high-income and wealthy households (i.e. more “progressivity” in the tax system), while keeping the overall tax burden on labour income constant. The wealth tax has been increased. The difference in income taxation between those with incomes below NOK 750 000 per year (roughly EUR 75 000) and those with income above this threshold has been widened. Furthermore, a temporary support scheme to compensate households for 80% of the electricity prices above a threshold of NOK 0.70 per kWh) and a cut in the electricity tax have been introduced in response to higher electricity prices.

Advancing green transition, including through increasing the price of carbon. Some offsetting policy adjustments have been introduced, including reduced taxation of vehicle use and ownership.

Encouraging full-time and permanent contracts over part-time and temporary work.

Greater support to households for childcare. For instance, the supplementary Budget for 2022 (published in November 2021) announced a reduction in the price ceiling for child care services, and this has been decided in the Parliament.

More support for rural communities. Government intentions include narrowing the gap between incomes in the agricultural sector and the rest of the economy and a pilot scheme of “rural growth agreements” for municipalities. The supplementary Budget for 2022 included proposals to increase support for agriculture, the fishing industry, and rural broadband.

Widespread vaccination has helped limit the impact of COVID-19

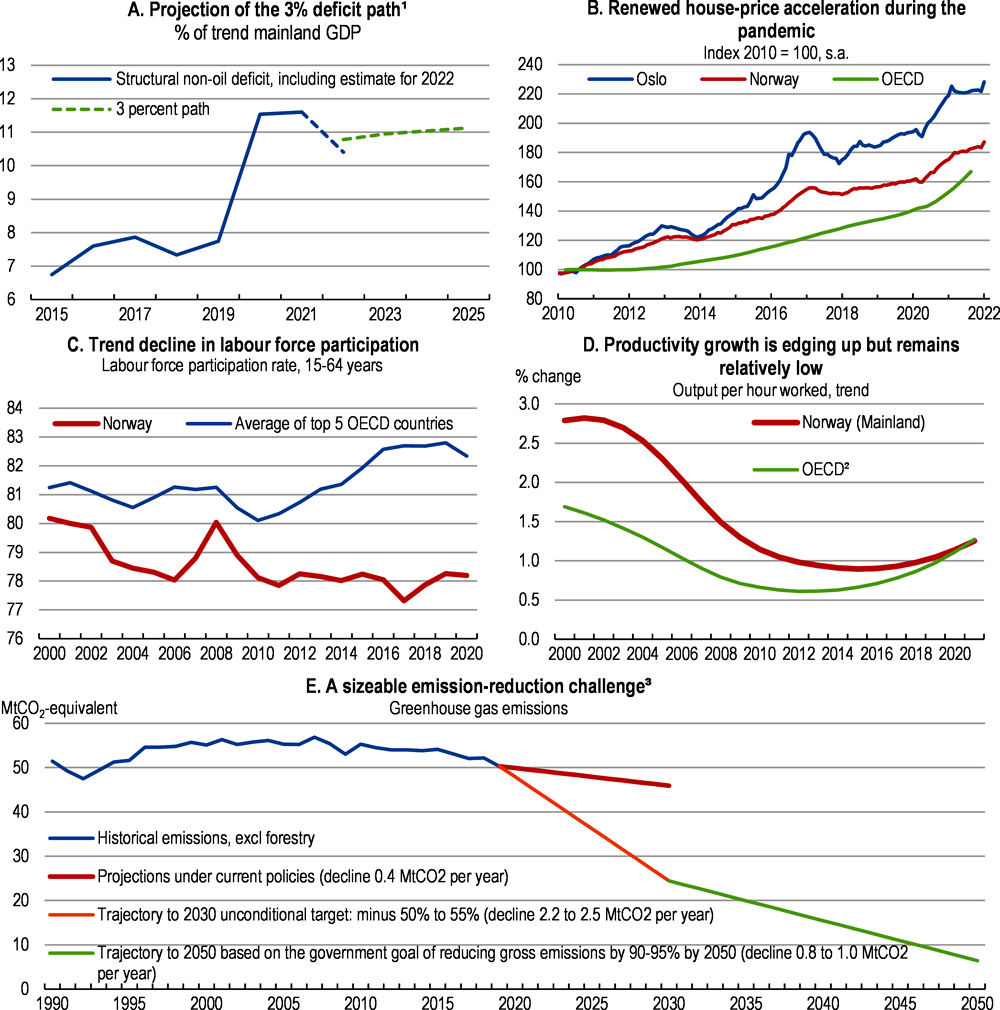

Though recent surges in infections brought new peaks in case numbers and fatalities, the cumulative case and fatality rates from COVID-19 have remained below the OECD average throughout the pandemic (Figure 1.3). Since the start of the pandemic Norway has experienced around 250 COVID-related deaths per million persons, compared with over 1 500 deaths per million in the OECD as a whole. A large proportion of the population has been vaccinated.

Early introduction of containment measures is thought to have contributed to Norway’s comparatively good outcomes. In particular, early implementation of international travel restrictions probably helped avoid the much higher number of cases seen in many other countries. Also, Norway’s comprehensive welfare support (bolstered by additional measures during the pandemic) reduced the risk of contagion -- for instance because individuals with symptoms were well supported financially if they did not work. The comprehensive public health care system has played a central role towards an effective response in treatment, testing and vaccination. Contextual factors that may have contributed towards relatively good outcomes include Norway’s low population density, a culture of following regulation and high trust in government. Furthermore, extensive broadband coverage has facilitated teleworking.

Risks to the economy from further COVID-19 outbreaks remain, as demonstrated by the emergence of the Omicron wave at the end of 2021. Countries with a substantial share of the population vaccinated, such as Norway, have been better able to withstand new waves of COVID-19 cases. Instances of serious illness are much lower, meaning less risk to individuals and less pressure on the health care system. The slow pace of vaccination in many developing countries, principally due to challenges in supply and distribution, raises global risks of new variants of COVID-19 emerging; travel to and from many countries remains restricted (Box 1.2).

Box 1.2. Norway’s engagement in accelerating global vaccination

Norway is engaged in international cooperation to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic and to improve the multinational architecture for future pandemic preparedness and response. Norway co-leads the Facilitation Council for the Access to COVID-19 Tools – Accelerator (ACT-A) together with South Africa and is engaged in the international dialogue on future health security cooperation including establishing a new global financing mechanism for better pandemic preparedness. Norway has so far granted around NOK 6.5 billion to combat COVID-19 under the ACT-A. In addition, Norway has donated 5 million vaccine doses for low and lower-middle income countries under the vaccine pillar of ACT-A, COVAX.

Sources: The Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator (who.int); Remarks by Jonas Gahr Støre, Prime Minister, Norway at the 8th ACT-Accelerator Facilitation Council (who.int).

Figure 1.3. Norway’s COVID-19 fatalities remain comparatively low, most of the population is vaccinated

1. The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker index is a composite measure based on nine response indicators including school closures, workplace closures, and travel bans, and is scaled from 0 (no restrictions) to 100 (highest category of restrictions). The unweighted OECD average covers all OECD countries where data are available for all components.

Source: Oxford University and Our World in Data.

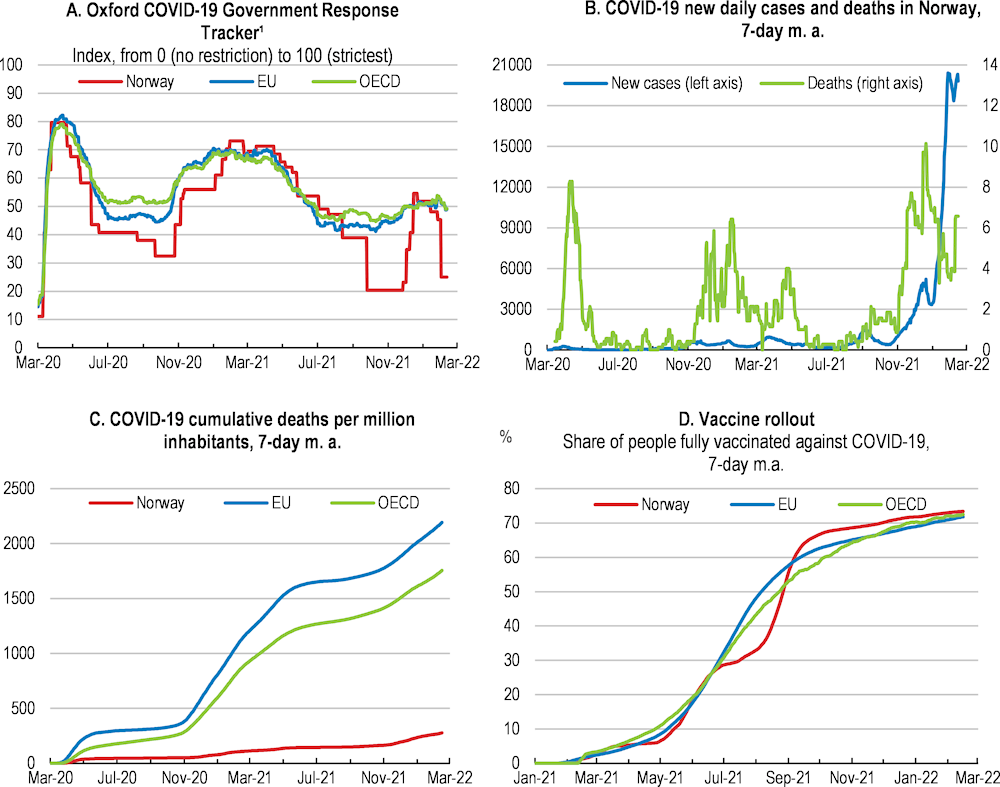

Several indicators are suggesting enduring shifts in work habits and changes in where people want to live in the wake of the pandemic. As elsewhere, the crisis has led to a realisation that for many occupations teleworking is more feasible than previously thought possible. A lasting shift in work habits looks likely, though the magnitude of it is uncertain. Norwegian mobile phone data show that in October 2021, when there were very few restrictions, presence at work places was around 10% below pre-pandemic levels (Figure 1.4). A permanent reduction in the frequency of travel to workplaces would suggest:

Shifts in the geography of housing demand. Norges Bank research using property register transactions has found evidence of reduced demand for large flats and greater demand for detached houses (Lindquist et al., 2021[1]). There has reportedly also been strong increase in the demand for leisure homes.

Less use of public transport systems. Mobile phone data indicate that use of public transport systems is still below pre-pandemic levels, despite the return of aggregate economic activity and employment to pre-pandemic trend (Figure 1.4).

Reduced demand for work spaces, particularly office space, as employers adjust to more employees teleworking (though this could be offset by need for increased space per worker if distancing rules are maintained).

Lower demand for goods and services provided in business districts, and greater demand in residential areas. For instance, shrinkage in services linked to eating, entertainment and exercise in or near work places would seem likely.

Figure 1.4. A similar downshift in use of workplaces and public transport as other countries

Percentage change in the number of visits recorded on mobile devices relative to early 2020, 7-day moving average

Note: This dataset from Google measures visitor numbers to specific categories of location (e.g. grocery stores; parks; train stations) every day and compares this change relative to baseline a day before the pandemic outbreak. Baseline days represent a normal value for that day of the week, given as median value over the five‑week period from January 3rd to February 6th 2020. Measuring it relative to a normal value for that day of the week is helpful because people obviously often have different routines on weekends versus weekdays. The data are not seasonally adjusted.

Source: Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports via Our World in data (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/visitors-transit-covid).

The economy continues to strengthen, but risks remain

Norway’s aggregate economic output is close to pre-pandemic trend, despite a temporary slowdown in activity from the Omicron wave. The OECD’s latest Economic Outlook (published December 2021) envisaged mainland output growth of 4.2% in 2022 and 1.7% in 2023. Due to the Omicron wave mainland output growth is expected to be weaker than previously forecast in 2022 but stronger in 2023; provisional estimates are for real mainland GDP growth of 3.7% in 2022 and 2.2% in 2023 (Table 1.3) (note, mainland output excludes oil and gas production and shipping). The level of real mainland GDP is still expected to run slightly above estimates of the pre-pandemic trend over the next two years (Figure 1.5). Household consumption will continue to contribute significantly, helped by the additional spending power from savings accumulated during the initial phases of the pandemic. Norges Bank lending surveys suggest the savings accumulated during lockdowns were not widely used to make additional mortgage payments, or towards down payments (Norges Bank, 2021[2]). So it would appear considerable savings are indeed available for further consumption.

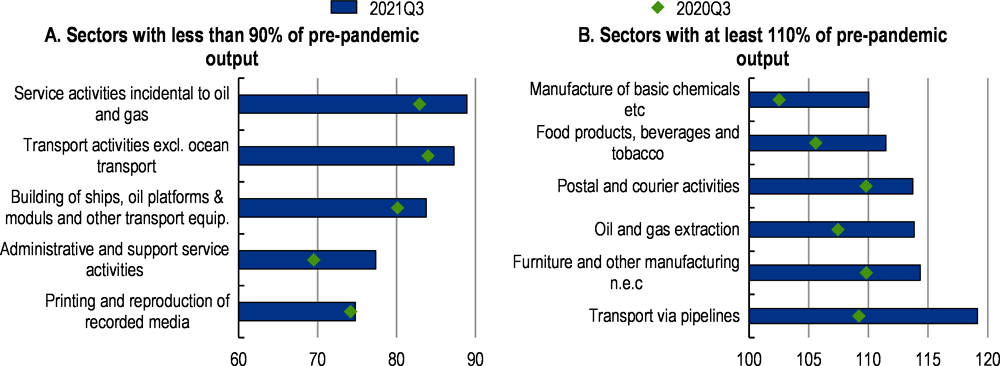

Some sectors have been severely affected by the pandemic (Figure 1.6). Some experienced very large drops in activity in the initial months of the pandemic. Notably activity in accommodation and food services dropped by around 50% in the second quarter of 2020. This and other hard-hit industries had since seen significant recovery, before renewed tightening of containment measures in mid-December 2021. Meanwhile some sectors have seen increased activity over the pandemic. Retail has broadly fared well, reflecting substitution in spending from services to goods. In terms of specific sectors, predictably, activity in home delivery services grew rapidly. Also output increase in furniture manufacture and the manufacture of wood products has been large. These developments may link to surges in spending on interior decoration and home office equipment when rates of teleworking were high.

Figure 1.5. Output is close to its pre-crisis trend

Note: Panel A: The pre-crisis growth path is based on the November 2019 OECD Economic Outlook projection, with linear extrapolation for 2022 and 2023 based on trend growth in 2021. The December 2021 Economic Outlook projection was finalised end-November 2021 and the provisional projection was made in February 2022.

Source: OECD (2019), OECD Economic Outlook 106 and OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook 110 (databases); and provisional updates.

Figure 1.6. Most sectors hit hard by the pandemic are recovering, though not all

Output volume relative to pre-pandemic output Q4 2019, in %

Note: Calculations are based on national accounts value added data at 2018-prices, seasonally adjusted.

Source: Calculations based on data from Statistics Norway.

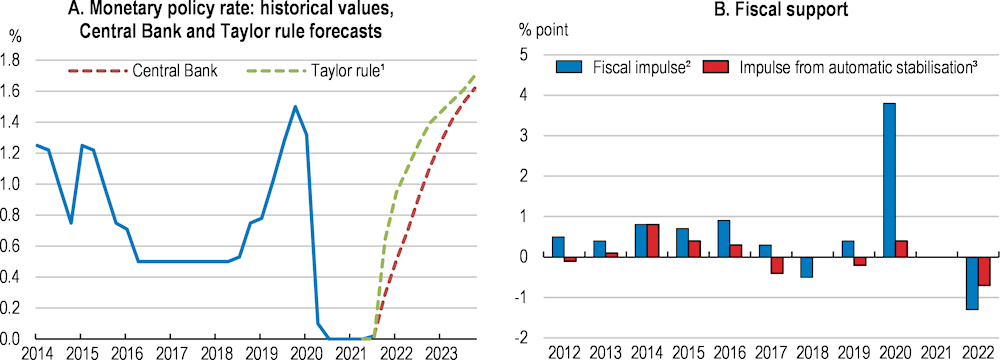

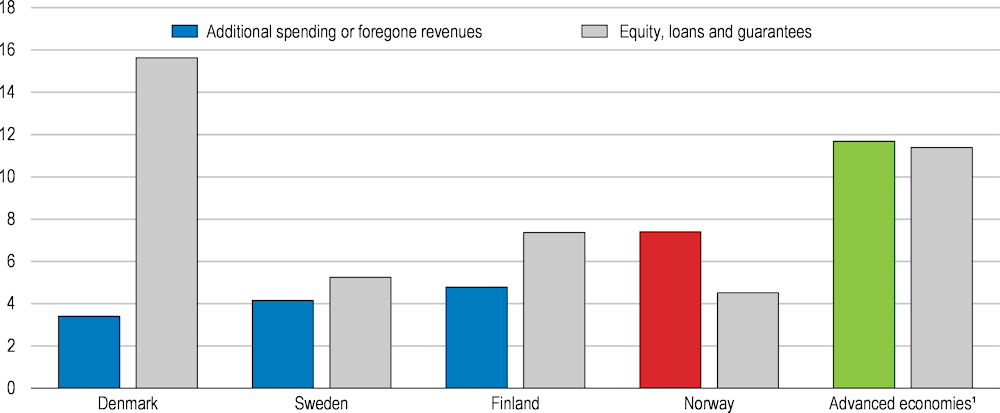

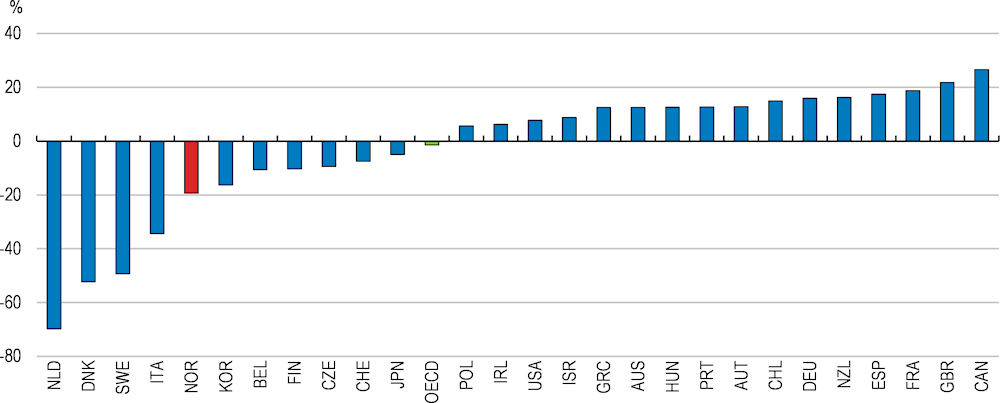

Given the prospect of total output running slightly above pre-pandemic trend when the economic impact of the Omicron wave has passed, macroeconomic stimulus should continue to be withdrawn (Figure 1.7). Prior to the recent surge in infections, fiscal revenues had grown and spending on government transfers had diminished as households and businesses returned to normal levels of economic activity. The government has been able to withdraw most of the temporary support programmes, though some support was reintroduced to combat the Omicron wave (Box 1.3). Norges Bank has begun raising its key policy rate, partly due to the rising price pressures. A first increase was made in September 2021, with a hike from zero to 0.25% and a second increase to 0.5% in December. The policy rate forecast indicates the rate will rise to 1.75% towards the end of 2024 (Norges Bank, 2021[2]). Thus far, the pace of stimulus withdrawal, both fiscal and monetary, appears appropriate. Norway’s fiscal support has mostly come through subsidies (as opposed to loans, guarantees and deferrals of tax liability), which reduces the risk of debt overhang and bankruptcies going forward, also making investment prospects brighter. According to IMF data, the total value of support has been relatively small in international comparison (Figure 1.8). Despite the improving economic outlook, the authorities must remain vigilant and responsive to any shift in circumstances, as proved necessary in mid-December 2021.

Figure 1.7. Normalisation of monetary and fiscal support is underway

1. Taylor-rule estimates are based on a backward-looking monetary-policy reaction function and OECD economic projections.

2. Annual change in the structural non-oil deficit. Estimated to be zero in 2021.

3. Automatic stabilisation data are calculations supplied by the Ministry of Finance. Estimated to be zero in 2021.

Source: Norges Bank; Statistics Norway and OECD calculations; and Ministry of Finance.

Figure 1.8. Norway’s package of fiscal support relied more on income support than on support through equity, loans and guarantees

Discretionary fiscal response to the COVID-19 crisis, % of GDP

Note: Estimates as of September 27th, 2021. Data include COVID-19 related measures since January 2020 and cover measures for implementation in 2020, 2021, and beyond.

1. According to the classification of economies in the IMF Database of fiscal policy responses to COVID-19, i.e. : Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Spain, United Kingdom, United States, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland.

Source: IMF (2021), Database of fiscal policy responses to COVID-19.

Box 1.3. Special measures to support households and businesses during the pandemic

With an already comprehensive welfare system, existing benefit schemes could be adapted to provide much of the additional support to households during the pandemic. For instance, unemployment benefit was made more widely available and more generous in length and pay out (Table 1.1). As shown in later sections on fiscal policy, outlays on extensions to schemes in 2020 were equivalent to around 0.5% of GDP (regular outlays on the schemes also increased substantially). Many other measures were extended or introduced. These targeted specific groups and circumstances, such as compensation for parents having to remain at home due to school closures (an extension of existing parental benefits). In addition, some of the support for businesses was, in effect, also support for households, such as the wage subsidy for employers to re-employ temporary lay-offs. Most additional support had been withdrawn by the end of 2021, however some was re-introduced following the emergence of the Omicron wave in December 2021. This recent support included a new temporary wage subsidy for businesses. Norway’s extra support to businesses has been wide-ranging. It has included subsidies, reductions in employer contributions, tax deferrals, loan assistance and targeted support for a wide range of specific sectors (Table 1.2). Most measures were planned to be withdrawn during the last part of 2021, including the most prominent scheme, a subsidy which covered a proportion of fixed business costs for companies facing losses as a result of the pandemic (businesses had to pass criteria demonstrating at least 30% loss of income). This scheme was prolonged for November-December 2021 and the first two months of 2022. The scheme was introduced rapidly, and was subsequently adjusted in light of experience to make it better targeted. For example, a deductible was removed during the first months. Furthermore, the scheme was scaled up and down according to the health situation. In the scheme’s latter stages the alterations notably included substantial reduction in support for medium turnover losses partly due to concern about adverse effects around the threshold of 30%. As the economic emergency diminished, there was concern that the scheme was holding back economic recovery with businesses calculating it better to remain closed and eligible for subsidies than reopening in an uncertain economic environment. This is, in part, why the subsidy was tightened in times of economic improvement. In light of the spread of the omicron variant, the scheme was made more generous for November-December 2021.

Table 1.1. Government support for households during the COVID-19 crisis, selected measures

|

Measure |

Selected detail |

|---|---|

|

Augmentation of unemployment benefit Introduced March 2020. |

Extended duration, increased compensation, wider coverage, three-day waiting time waived. Special rules for seasonal workers in agriculture and fishing industry, cab-drivers, apprentices. A new rule allowing those receiving unemployment benefit to engage in study introduced (permanent change). |

|

Augmentation of temporary lay-off scheme Augmentation introduced March 2020. |

Reduced employer payment to 2 days (from 15 days) in March 2020, then 10 days from September 2020. Normally a compensation rate of 62.4%, however increased to 80% for income up to around NOK 300 000 and gradually scaled down to 62.4% for income up to around NOK 600 000, which is the maximum income that is compensated. The duration of access to compensation has once again been extended. |

|

Extended right to sickness benefits |

Sickness benefits can be granted to patients infected by (suspected) COVID-19 infection. |

|

Extended period for Work Assessment allowance Due to terminate June 2022. |

The benefit period for persons receiving Work Assessment Allowance (AAP) has been extended. |

|

Labour migration measures Terminated September 2021. |

Compensation scheme for EEA-workers with a job in Norway who were blocked from entering Norway due to restrictions. |

|

Other support (selected). |

Compensation for parents (care benefits) remaining at home due to children in quarantine and closure of schools and kindergartens. Facilities for laid-off employees to remain on company pension schemes. Comparatively small-scale support for a wide range of groups and activities, including students and apprentices. |

Source: OECD

Table 1.2. Government support for businesses during the COVID-19 crisis, selected measures

|

Measure |

Selected detail |

|---|---|

|

Fixed-cost subsidy scheme Introduced March 2020 |

A subsidy covering a portion of the fixed cost for companies facing a turnover decrease related to COVID- 19. |

|

Labour-cost subsidy scheme. Introduced December 2021 |

The amount of wage-bill support depends on how much a firm’s sales income declines. Payouts are capped at a maximum of NOK 40 000 per employee and must not exceed 80% of former wage costs (thus remaining in line with EU competition rules). |

|

Labour-cost subsidy scheme Introduced July 2020, terminated 31 August 2021 |

Grants to cover labour costs for employers who take back laid-off workers. Pay-outs were up to NOK 15 000 per month per employee. |

|

Temporary cut in employer contribution in May and June 2020 |

A cut in the employers’ social insurance contributions by 4 percentage points for the equivalent of 2 months. |

|

Reduced pay-out obligations for temporary layoffs and sick leave Introduced March 2020 |

Reduction in the number of days that employers are obliged to pay salary to workers at temporary lay-offs (see Table 1.1). Reduced employer contribution period when sickness due to (suspected) COVID-19 infection. Employer contribution in case of covid-related sickness absences reduced from 16 days to 3 days in March 2020, increased in September 2021 to 10 days, and reduced again in December to 5 days. |

|

Credit and loan guarantee support Introduced March 2020, terminated October 2021. Reintroduced January 2022 |

State guarantees for enterprises, initially for firms with less than 250 employees, later extended to all enterprises (in total up to NOK 50 billion). Reinstatement of the Government Bond Fund that purchases company bonds (in total up to NOK 50 billion). |

|

Other tax measures |

Temporary reduction in the low VAT rate from 12 to 6%. Measures to help lossmaking companies that i) enabled lossmaking companies to re-allocate their loss in 2020 towards previous taxed surplus in 2019 and 2018, and ii) enabled the owners of lossmaking companies to postpone payments of wealth tax. - temporary tax concessions for the oil and gas sector (see main text). |

|

Sectoral support Some measures remain in place Due to terminate June 2022 |

Various support for air travel sector including: a special aviation-sector guarantee, temporary suspension of the tax on air passengers, aviation charges. A range of supports for innovative and research-oriented businesses, including: grants for young growth companies, innovation loans, interest-payment support, grants for private innovation groups, business-oriented research support, capital for funding and matching investments, increased basic support for research institutes. Support for a wide range of other sectors, including culture, sport and voluntary sectors; the brewery industry; fuel industry; horse racing and reindeer herding. |

|

Other measures |

Lighter share-price rules in the event of a change of control in listed companies, with a view to facilitating acquisition and restructuring. Strengthened support for skills upgrade and in-house training for companies through increased grants to the counties. |

Source: OECD

One concern for the outlook is that the business sector may be weaker than appears in the data. Businesses and employment have been supported by various programmes, and thus the true state of economic recovery may be less robust than it appears. Activity in some sectors, though much recovered, remains below pre-pandemic levels and the increase in electricity costs will be weighing on many businesses. Furthermore, indicators on the health of the business sector have not always worked well in the wake of the pandemic downturn. For instance, bankruptcy filings temporarily stopped being a guide to the extent of business failure, inter alia due to less bankruptcy filings from the tax authorities during the pandemic and the introduction of a temporary scheme for tax deferrals (Figure 1.9). Further business failures may emerge, particularly in sectors hard hit by the crisis. Some evidence suggests risk of this materialising into a serious threat to economic recovery looks to be small. Norges Bank research finds that collecting deferred VAT will hardly trigger a wave of bankruptcies (Norges Bank, 2021[2]). Also, under a temporary scheme businesses are able to pay deferred tax debt bills in monthly instalments. Nevertheless, the risk of a destabilising wave of weak business performance, including bankruptcies, should not be discounted completely.

Table 1.3. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

|

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Current prices (NOK billion) |

Percentage change, volume (2018 prices) |

||||

|

Total GDP at market prices (A) |

3554 |

0.7 |

-0.7 |

3.9 |

4.5 |

2.7 |

|

Mainland GDP¹ at market prices (B) |

2935 |

2.0 |

-2.3 |

4.2 |

3.7 |

2.2 |

|

Mainland GDP¹ at market prices (Economic Outlook, December 2021) |

2.0 |

-2.3 |

4.2 |

4.2 |

1.7 |

|

|

Petroleum-production contribution to GDP volume growth (A minus B) |

-1.3 |

1.6 |

-0.2 |

0.8 |

0.5 |

|

|

Potential GDP (based on mainland GDP) |

. . |

1.5 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

|

Output gap (% of potential mainland GDP) |

. . |

0.3 |

-3.4 |

-0.5 |

1.9 |

2.8 |

|

Total GDP volume components |

||||||

|

Private consumption |

1,527 |

1.1 |

-6.6 |

5.0 |

6.6 |

3.1 |

|

Government consumption |

826 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

3.9 |

2.3 |

1.2 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

850 |

9.5 |

-5.6 |

-0.3 |

3.7 |

3.0 |

|

Housing |

194 |

-1.1 |

-4.0 |

2.6 |

0.5 |

1.8 |

|

Business2,3 |

463 |

14.8 |

-8.0 |

-0.3 |

4.3 |

3.8 |

|

Government |

194 |

7.5 |

-1.1 |

-3.1 |

5.3 |

2.0 |

|

Final domestic demand |

3,203 |

3.4 |

-4.2 |

3.2 |

4.6 |

2.6 |

|

Stockbuilding4,5 |

147 |

-1.1 |

-0.4 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

3,350 |

2.1 |

-4.5 |

3.0 |

4.6 |

2.4 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

1349 |

1.1 |

-1.2 |

4.8 |

7.2 |

3.0 |

|

of which crude oil and natural gas |

569 |

-0.1 |

4.4 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Imports of goods and services |

1,146 |

5.1 |

-11.9 |

2.0 |

8.4 |

2.7 |

|

Net exports4 |

204 |

-1.2 |

3.7 |

0.9 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

||||||

|

Labour-market and households |

||||||

|

Employment6 |

. . |

1.1 |

-0.6 |

1.5 |

2.0 |

0.9 |

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force) |

. . |

3.7 |

4.6 |

4.3 |

3.5 |

3.2 |

|

Household saving ratio, net (% of disposable income) |

. . |

7.6 |

14.5 |

13.5 |

9.1 |

8.1 |

|

Deflators, prices |

||||||

|

GDP deflator |

. . |

-0.5 |

-3.6 |

16.9 |

5.9 |

1.3 |

|

Consumer price index |

. . |

2.2 |

1.3 |

3.5 |

2.5 |

1.5 |

|

Consumer price index (Economic Outlook, December 2021) |

. . |

2.2 |

1.3 |

3.4 |

2.0 |

1.4 |

|

Core consumer price index7 |

. . |

2.6 |

3.1 |

1.4 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

|

Trade and current account balances |

||||||

|

Trade balance (% of GDP) |

. . |

1.5 |

-0.8 |

12.5 |

12.9 |

12.9 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

. . |

2.9 |

0.7 |

14.6 |

14.5 |

14.5 |

|

Money market rates and bond yields |

||||||

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

. . |

1.6 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

1.4 |

2.0 |

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

. . |

1.5 |

0.8 |

1.5 |

2.2 |

2.6 |

|

General-government fiscal indicators (OECD) |

||||||

|

General government fiscal balance8 (mainland, % of mainland GDP) |

. . |

-0.2 |

-5.3 |

-5.1 |

-3.2 |

-2.3 |

|

General government net debt (% of GDP) |

. . |

-331.2 |

-370.1 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Central-government fiscal indicators (Ministry of Finance)9 |

||||||

|

-7.7 |

-11.5 |

-11.6 |

-10.4 |

.. |

||

|

Government Pension Fund Global (% of mainland GDP)12 |

-268.7 |

-331.5 |

-337.1 |

.. |

.. |

|

|

Structural non-oil balance11 (as a % GPFG) |

-2.9 |

-3.6 |

-3.5 |

-2.9 |

.. |

|

Note, unless otherwise stated, these projection numbers are from a provisional economic forecast by OECD Secretariat completed in February 2022.

1. GDP excluding oil, gas and shipping.

2. Also includes shipping sector.

3. Following the approach taken by the Norwegian authorities, oil-sector investment is included in mainland GDP as most of the investment activity takes place on the mainland.

4. Contributions to changes in real GDP, actual amount in the first column.

5. Including statistical discrepancy.

6. Employment growth includes an adjustment to take account of a break in the data between 2020 and 2021.

7. Consumer price index excluding food and energy.

8. Year-on-year changes in this balance roughly equate to year-on-year changes in the Central-government structural non-oil balance.

9. Figures published in the government’s latest budget proposals.

10. The central-government non-oil balances notably exclude offshore-sector tax revenues and income from the Government Pension Fund Global. These balances are percentage of trend mainland GDP.

11. The “Structural Non-oil Balance” is the focus of government budgeting. “Structural” refers to adjustment for the business cycle made by the Ministry of Finance.

12. At the beginning of the year.

Source: OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook 110 (database); Statistics Norway; and Ministry of Finance.

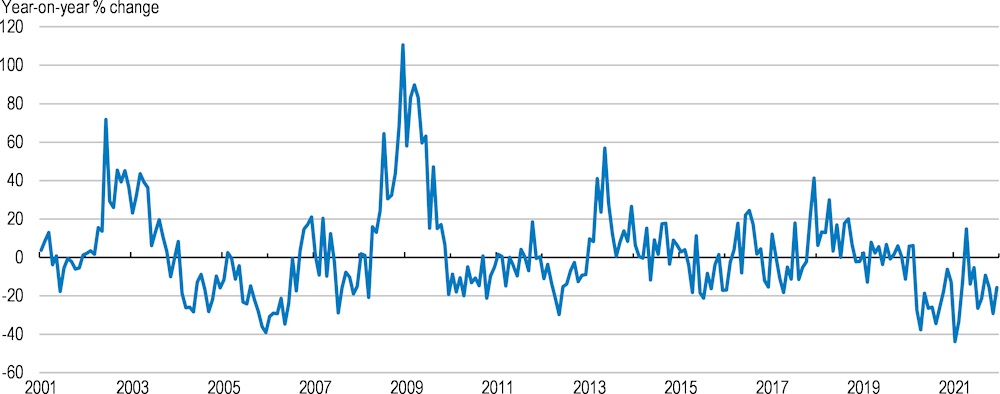

Figure 1.9. Bankruptcies have so far been lower during the pandemic

New bankruptcy proceeding started, s.a.

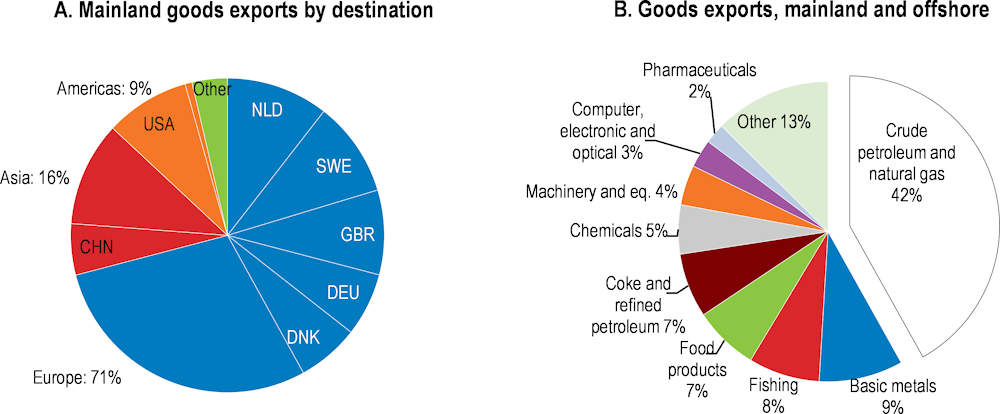

Uncertainty about the future global price of oil, and more broadly the future of the petroleum sector, is a perennial source of upside and downside risk for activity and incomes relating to the industry. Dramatic fall in the oil price in the initial months of the pandemic contributed to a decline in investment activity in the sector. With intensifying global awareness of climate change, it is possible that Norway’s transition away from oil and gas activities may be faster than previously expected, while the current high gas prices may point in the other direction. As discussed in previous Surveys, it is the speed of the transition from petroleum to other activity that will determine whether there are critical macroeconomic consequences for the Norwegian economy. If labour and capital resources can be reallocated away from the oil and gas sector and related industries at a speed that avoids substantial increase in unemployment or stranded assets, then the transition will be comparatively benign. Already, the Norwegian economy is less oil dependent than only a few years ago and has proven its strong ability to adjust. Oil companies have gone through a cost-cutting process, lifting profitability even at low prices. Employment in petroleum related activity has fallen by a third. Gas is becoming an increasingly large part of Norwegian petroleum-sector production. Furthermore, natural gas has a key role in the global energy transition. It enables increased and faster phasing out of coal for some European countries. Natural gas with carbon capture and storage might also be an important source for hydrogen production. The current energy crisis in Europe and geopolitical risks also illustrate the importance of stable and reliable gas deliveries to the European market.

Table 1.4. Events that could lead to major changes in the outlook

|

Possible extreme shocks to the Norwegian economy |

Possible outcome |

Policy response options |

|---|---|---|

|

Emergence of another strain of COVID-19, beyond the Omicron variant, that is highly virulent and deadly. |

Current vaccines could prove ineffective against new strains, with potential for even larger increases in numbers of hospitalisations, cases of serious illness and fatalities. |

Continued identification of virulent new strains and prompt action to prevent their spread, including through vaccination. Re-imposition of social distancing measures. |

|

Spiralling wage and price inflation. |

Macroeconomic instability from large price and exchange-rate movements, relative price distortions leading to misallocated resources, losses for households whose incomes do not keep pace with inflation. |

Managed control and reduction of inflation through monetary policy. Support for low-income households hard hit by inflation |

|

Large house-price correction and household debt deleveraging. |

Large house-price falls (a “hard landing”) could lead to falling household consumption, losses for businesses, reduced value on commercial property and rising non-performing loans. |

Monetary and fiscal support, targeted support to those most affected by the housing downturn. Support to the financial sector, as appropriate. |

|

Large (and sustained) upward or downward oil-price shift. |

Low price scenario (e.g. because of breakthrough in substitute technologies, or significantly lower world demand). Decline of petroleum-related activities. Large job losses and falls in income and output, particularly in certain regions. High-price scenario. Increased wealth and incomes but a deepening of the challenges in managing oil wealth.* *Oil-price fluctuation (in either direction) generally prompts an automatic fiscal response and countervailing exchange-rate movement due to the wealth fund and fiscal rule. |

For low price scenario. Monetary and fiscal support. Targeted support for most affected regions and sectors. Intensified efforts to improve the environment for non-oil business. |

Financial stability: costs, prices and wages on watch, household debt still high

Recent energy-price increases are most likely temporary, but more persistent wider price pressure is a risk

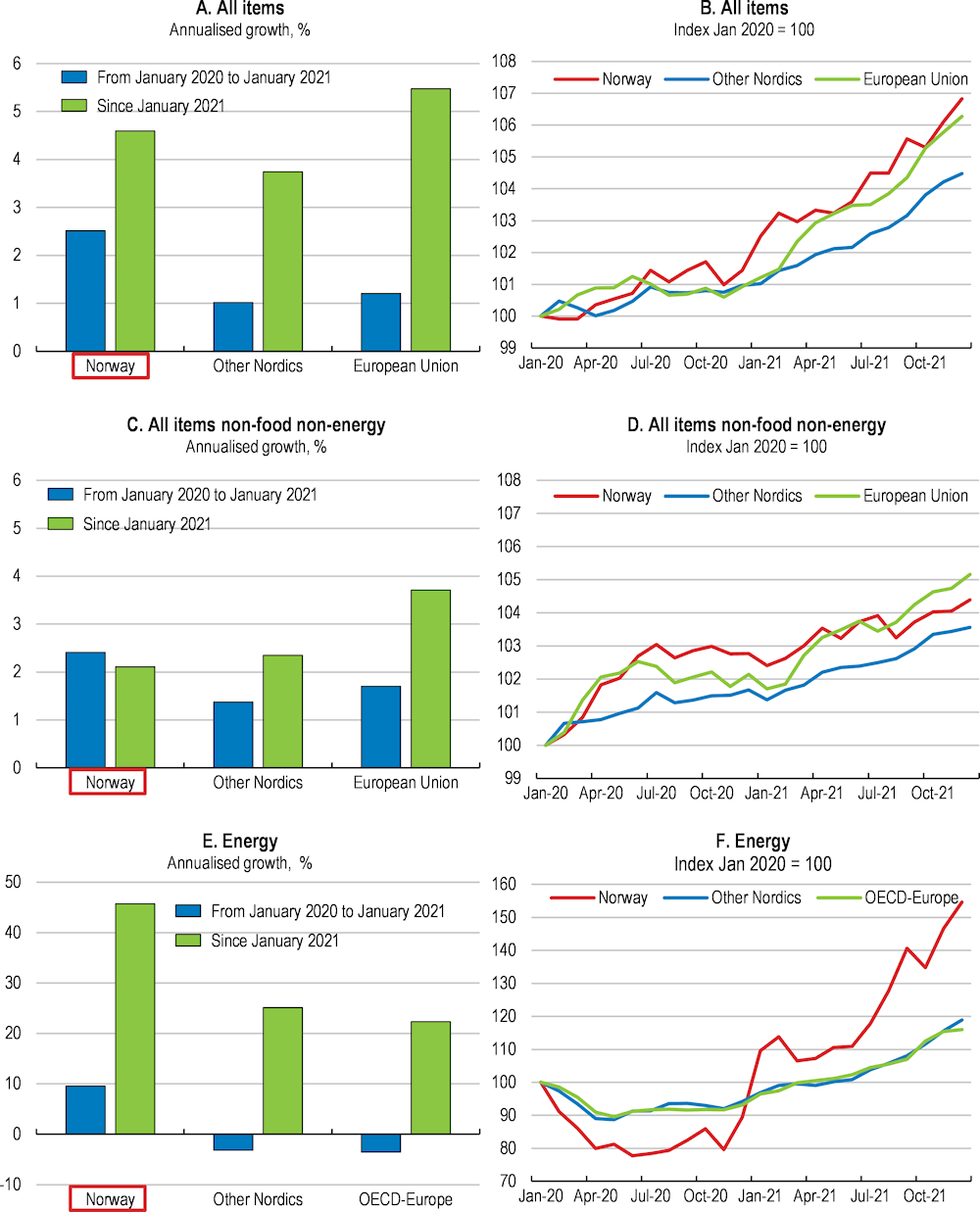

In recent quarters, headline consumer price inflation has been strongly driven by large electricity price increases. Norway is connected to the European electricity grid but, as is typical in electricity markets, limitations in transmission capacity mean that, to an extent, electricity prices have a different level and dynamic from neighbouring markets (similarly, there are price differences across regions within Norway). Norway experienced particularly sharp electricity-price rises in late 2020 and in the autumn of 2021 (Figure 1.10., Panel E). Economic recovery, plus cold weather, boosted demand for electricity. Supply was, inter alia, affected by below-average wind and dry weather in southern Norway, the latter affecting hydropower generation. Growing global demand for liquefied natural gas (LNG) and consequent growth in natural gas prices in Europe have also played a role (Norges Bank, 2021[2]). As Norwegian households typically have variable-price electricity supply contracts, there is strong transmission from wholesale prices into retail energy bills. There is support to help with paying bills via social welfare; low-income households may receive a higher municipal social assistance payment where electricity costs are included in the municipality's means testing for benefits. Concern for the impact of recent electricity-price increases has prompted temporary compensation by central government (Box 1.4). In addition, a cut in the tax on electricity has also been introduced. Both the temporary compensation and the tax cut benefit all households, including higher-income households that can likely cope with high electricity prices. These policies are therefore an inefficient way to address concerns for energy affordability, which are primarily a concern for low-income households.

Figure 1.10. Norway’s headline consumer price inflation has been pushed up by large energy-price increases

Note: OECD-Europe includes OECD countries that are also European countries. Geographic definition of Europe including Turkey.

Source: OECD (2021), Main Economic Indicators (database); and OECD calculations.

Box 1.4. Norway’s temporary electricity-bill compensation scheme for households

Concern for the impact of high electricity prices on the cost of living prompted the government to introduce a temporary compensation scheme. For the month of December 2021 the scheme refunded 55% of the cost of electricity above a price of 0.70 NOK per kWh. For the period January to March 2022 the refund rate has been increased to 80%. The refund is capped at 5 000 kWh per household. It is made automatically on a household’s electricity bill and the power supply companies are compensated by the government. The government aims at introducing a similar scheme for the agricultural sector.

Similar to elsewhere, there are concerns about the effects on consumer prices of global supply bottlenecks in computer chips, lumber and shipping (notably reflected in high container prices). Some impact is apparent in consumer prices . For instance, maintenance and repair of dwellings showed sharp growth in mid-2021, reflecting a short-lived but substantial increase in lumber prices. However, so far the impact on overall prices in Norway of international supply-chain disruption has been small.

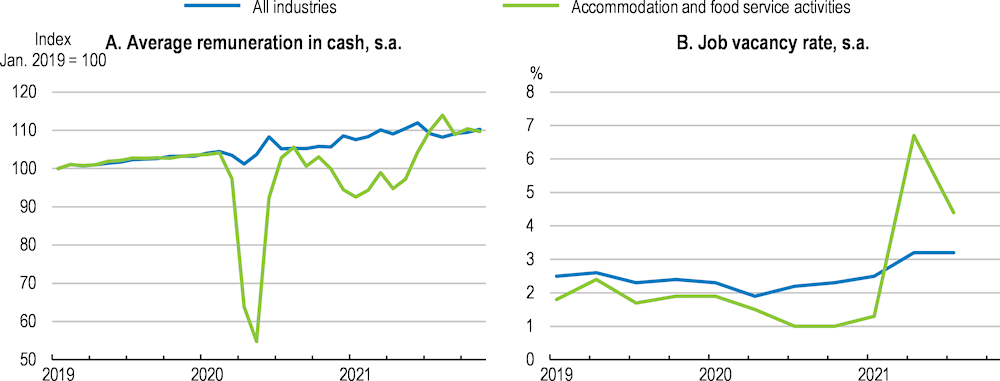

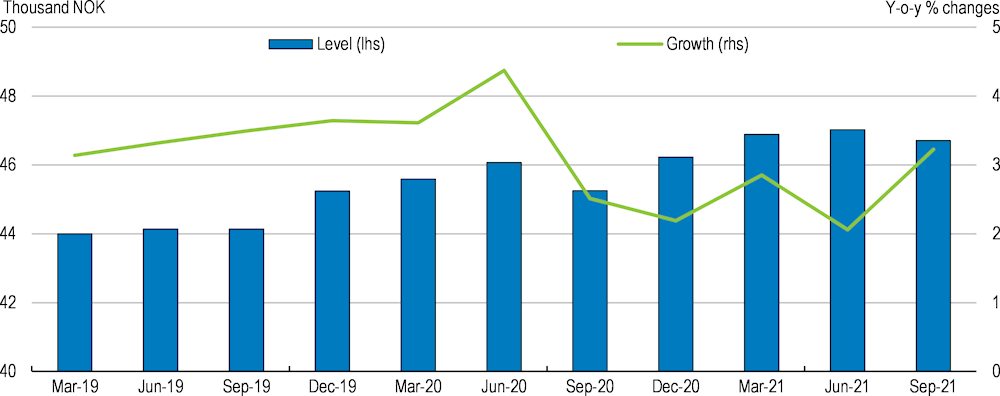

Meanwhile, however, a close watch on wage pressures is required. The pressures are growing with rising labour demand, relatively small inflows of foreign workers during the pandemic and the increase in consumer price inflation. A key question is whether the pressures start to fuel a generalised wage-price spiral. Certainly, labour market developments in some industries have been dramatic. At least prior to the Omicron wave, the vacancy rate in the accommodation and food services sector was high and with it, growth in average employee remuneration (Figure 1.11) (there is some concern that support for furloughed workers may be contributing to labour shortages in the sector, (Norges Bank, 2021[2])). Furthermore, recent quarterly wage data have indicated that more general wage growth may be underway, though more data points are needed to confirm this (Figure 1.12). Norway’s centralised wage-setting process limits the risk of wage-push inflation as it ensures macroeconomic considerations are typically given considerable weight in employee wage demands (the trade-exposed manufacturing sector is always the first sector that negotiates, providing a benchmark wage increase to other sectors). This said, when profits in the export sector are large, which has been the case in recent quarters due to higher oil and gas prices, then the guideline wage also increases.

It seems most likely that the recent pressures on consumer-price inflation will not spark a generalised surge in wage and price inflation. Norway’s headline consumer-price inflation has largely been pushed up by energy price hikes that have origins in temporary events, such as weather-related influences on hydroelectricity supply. A downward correction in energy prices, and headline inflation, seems likely. Core inflation remains moderate.

Nevertheless, an outbreak of generalised price and wage inflation cannot be ruled out. Despite the anchoring provided by Norway’s centralised wage bargaining system, wage inflation could see substantial increase. The tightening labour market has put employees in a strong position to ask for higher wages in response to rising living costs. Wage hikes would feed back into business costs, and likely output prices.

Figure 1.11. Remuneration and vacancies increased markedly in hospitality in 2021

Note: Panel A: Payment in cash includes all payments in cash from the employer including basic monthly earnings, fixed and variable allowances, bonuses, overtime pay and other payments in cash. Panel B: The job vacancy rate measures the proportion of total posts that are vacant.

Source: Statistics Norway.

Figure 1.12. Quarterly data indicate a more general increase in wage growth may be underway

Average nominal basic wage

Note: The basic wage index excludes supplementary components of earnings, such as overtime and bonuses. The wage index is for all industries and therefore changes in the index may reflect compositional changes in employment alongside changes in individual employees’ wages.

Source: Statistics Norway.

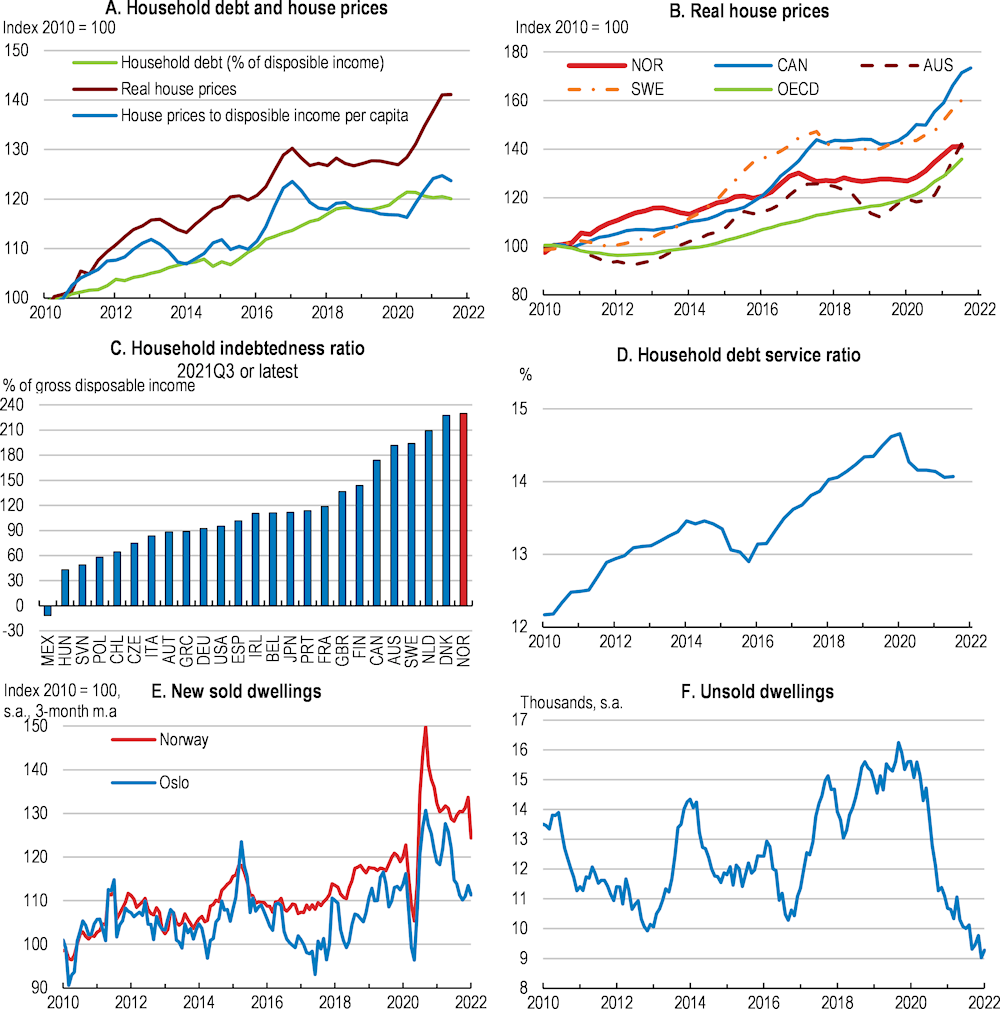

House prices and related debt remain a potential source of financial instability

Steep rises in house prices over the pandemic have added to past surges in the cost of home purchase. Canada, Sweden and Australia are among the OECD countries that have found themselves in a similar position (Figure 1.13). Expansionary monetary policy has been a contributory factor. Studies suggest that in Norway a 1 percentage-point reduction in the interest rate will lead (over time) to a pre-tax increase in house prices of between 4% and 11% (Norges Bank, 2021[2]). Higher savings arising from reduced consumption opportunities during lockdowns, and the prospect of more time working from home are also likely to have fuelled demand for housing, including renovation and upgrade. Lift-off in rate normalisation is likely to temper price growth. This may have already been playing a role in the recent softening of price growth seen in some areas, including Oslo. An estimate of the “fundamental” house price index by Norway’s Housing Lab research unit suggests the country’s house prices were overvalued by around 13% as of the second quarter of 2021, before Norges Bank begun raising its policy interest rate (the approach factors in household income, interest rates, and housing stock per capita).

Figure 1.13. House prices and debt are elevated

Source: Norges Bank; OECD Economic Outlook database; OECD dashboard of household statistics; and Refinitiv Datastream database.

The recent house-price increases, and further mortgage borrowing linked to this, add to risks of a correction with impacts on the wider economy. The most important channel would be through household consumption. House-price correction would directly damp consumption through negative wealth effects, precautionary saving responses and reduced expenditures related to the purchase and sale of housing (such as spending on renovation and interior decoration (OECD, 2019[3]). Weakening household consumption could, inter alia, feed through to the business sector, prompting business-loan losses for banks and an increase in mortgage borrowers encountering financial difficulty.

Furthermore, high household debt also makes Norway more vulnerable in the event of downturns, whether stemming from house-price correction or otherwise. Capitalisation requirements and safeguards in mortgage lending appear sufficient to avoid a direct risk to banks via mortgage default (see below). However, high household debt-servicing commitments imply large cutback in consumption in the event of a downturn in incomes. As most mortgages are variable-rate, changes in the interest rate directly impact a majority of mortgage holders. The substantial increase in the household saving ratio over the pandemic suggests many households currently have a buffer to handle any additional debt-servicing requirements. However, it is expected this will be eroded due to pent up demand boosting consumption of goods and services.

In addition, high household debt raises risks related to bank wholesale funding. Norwegian banks rely quite heavily on wholesale funding, much of it comprising covered bonds that are collateralised against mortgages. These bonds provide cheap and stable funding. However, there is substantial cross holding of these bonds within the Norwegian financial sector; over half the value of covered bonds is held by banks and mortgage institutions. This interconnectedness increases risks. For instance, a liquidity problem could balloon if banks simultaneously sell off covered bond holdings.

Macro-financial risk from Norwegian banks’ large holdings of commercial real estate has also grown in the wake of the pandemic. About half of banks’ exposures to the Norwegian corporate sector are in this segment. Norges Bank’s latest assessment (Norges Bank, 2021[2]) envisages a pick-up in commercial real estate rents in the near term as the economy recovers further. Further ahead, however, there is possible downside risk once businesses fully adjust to operating with more employees teleworking and consequently reduced needs for office space. As suggested in previous Surveys, additional data collection that gives a better picture of market developments would be helpful. In a welcome development on this front Norges Bank has recently switched to a new provider of statistics of prime office space that will provide data on a broader set of office premises (Norges Bank, 2021[4]).

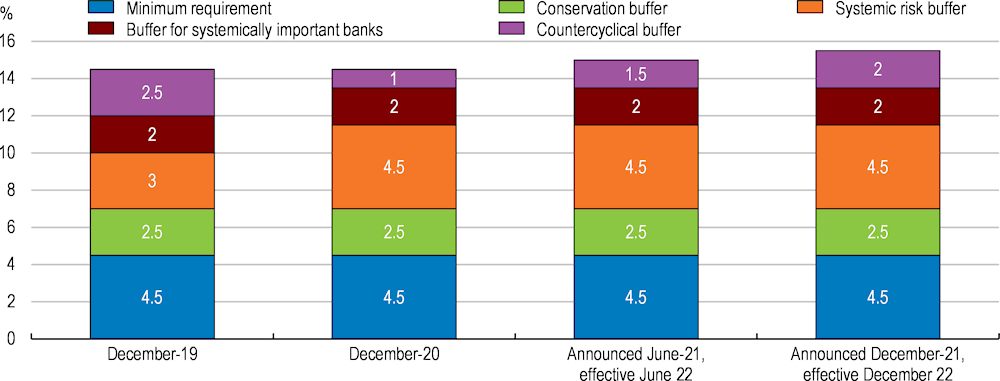

Given these post-pandemic risks and normalisation of economic activity, macro prudential instruments are, sensibly, being maintained. Increases in Norway’s countercyclical buffer (part of bank capitalisation requirements) were announced in June 2021 (as part of the emergency economic response in early 2020, the buffer had been cut from 2.5% to 1%, Figure 1.14). Norges Bank has announced an intention to lift the countercyclical buffer requirement back to the pre-pandemic level from July 2023. Regulations on mortgage and consumer loans were renewed without alteration in January 2021. These include caps on loan-to-value ratios and on the ratio of debt to income (Box 1.5). Evidence from new loans prior to the pandemic showed that both these regulations were indeed limiting lending activity (see the 2019 Survey). During the pandemic they will have helped limit the growth in housing and mortgage demand prompted by the sharp reduction in the policy rate.

Box 1.5. Norway’s macroprudential measures on mortgages and consumer loans

Rules imposed by financial authorities on mortgage-lending and consumer loans are a core channel through which financial-market policy aims to ensure prudent lending to households. Bank capital requirements and the monitoring of financial institutions (for instance via the scrutiny of balance sheets or detailed lending data) are the two other main channels. Norway’s macroprudential rules on mortgage lending and consumer loans principally comprise caps on the value of a loan in relation to the value of the property being purchased (loan-to-value ratio) and a limit on a household’s total debt in relation to its income (debt-to-income limit) (Table 1.5). Lenders are also required to check that the borrower can cope with an increase in the interest rate (stress test). Interestingly, Norway’s macroprudential rules include some geographic variation; some mortgage rules are tougher for purchases in Oslo than in other parts of the country. Also, there are “flexibility quotas” that provide financial institutions scope to provide some loans that exceed the limits set.

Table 1.5. Details of Norway’s macroprudential rules on mortgages and consumer loans

|

Mortgages |

Consumer loans |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Maximum loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, installment loans |

85% standard, 60% for secondary dwellings in Oslo |

- |

|

Maximum loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, home equity credit lines |

60% |

- |

|

Mandatory principal payments |

Loans with LTV ratio above 60% |

All loans |

|

Maximum debt-to-income limit |

5 times the level of income |

Same as for mortgages |

|

Stress test of debt-servicing ability in the event of an interest rate increase |

5 percentage-point interest-rate hike |

Same as for mortgages |

|

Flexibility quota. Banks are allowed a certain percentage of lending volume each quarter to exceed regulation requirements. |

10% standard, 8% in Oslo |

5% |

Source: Lending Regulation, press release posted 25 October 2021, Ministry of Finance.

Figure 1.14. Bank capital buffers are being expanded now the crisis is receding

Ratio of Common Equity Tier 1 (CET) requirements to risk-weighted assets, Norwegian Banks

Note. Norges Bank has signalled an increase in the countercyclical buffer for July 2023.

Source: Norges Bank (2021), Norway’s Financial System and Norges Bank press releases.

Assessment of price inflation facing households, and analysis of monetary stance and financial stability, would be helped if the housing components of Norway’s consumer-price index more strongly reflected housing market developments. Together with a measure of market rents, Statistics Norway, like many other national statistical agencies, includes in the CPI an estimate of the implied cost of housing for owner-occupiers. To do this they assume that so-called “imputed rents” to owner-occupied dwellings evolve in line with market rents. This type of “rental equivalence” approach is appropriate in countries where rental markets are large, and representative of the broader housing market. This is not the case in Norway: the rental market is relatively small compared with that for owner-occupied dwellings, and caters to a different segment of the population. Consequently, the price dynamics for rental and owner-occupied properties can differ. Furthermore, it is in principle harder to infer growth in imputed rents from observed growth in market rents. Alternative methods, notably approaches based on tracking the user cost of housing, can be more appropriate in such settings. In Canada, a price index for owned accommodation is constructed by estimating movements in costs related to mortgage interest, repairs and maintenance, depreciation and taxes. This can help ensure the impact of housing price movements is reflected in growth in the CPI. In light of such approaches, and initiatives elsewhere, for instance by the European Central Bank (ECB, 2021[5]) consideration should be given to a measure for owner-occupied housing costs that more fully reflects housing market developments.

Table 1.6. Past recommendations on macroeconomic and financial stability

|

Recommendations |

Action taken since the previous Survey (December 2019) |

|---|---|

|

Should house-price growth remain uncomfortably high, consider additional macro prudential measures. |

Response to the pandemic dominated policymaking. Policy rate cuts made as part of this response contributed to a surge in house-price growth. Other measures to increase liquidity included a lowering of banks’ regulated counter-cyclical capital buffer. In addition, the “speed limits” in the mortgage regulation were softened. As of late 2021, most measures had been terminated or were in the process of being restored to normal settings. Macro prudential regulation on mortgage borrowing was renewed without alteration in January 2021. |

|

Facilitate more responsive housing supply. In particular, lighten rules on release of land for development. |

No major reform. |

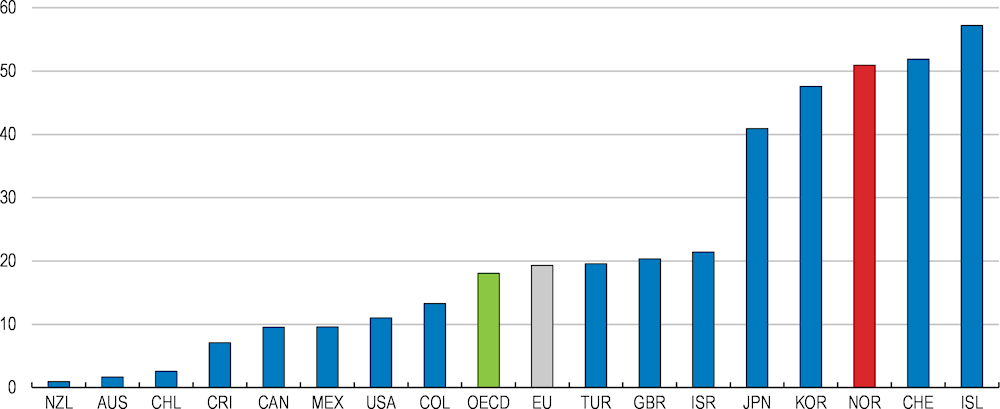

Fiscal policy: keeping on track with the fiscal rule

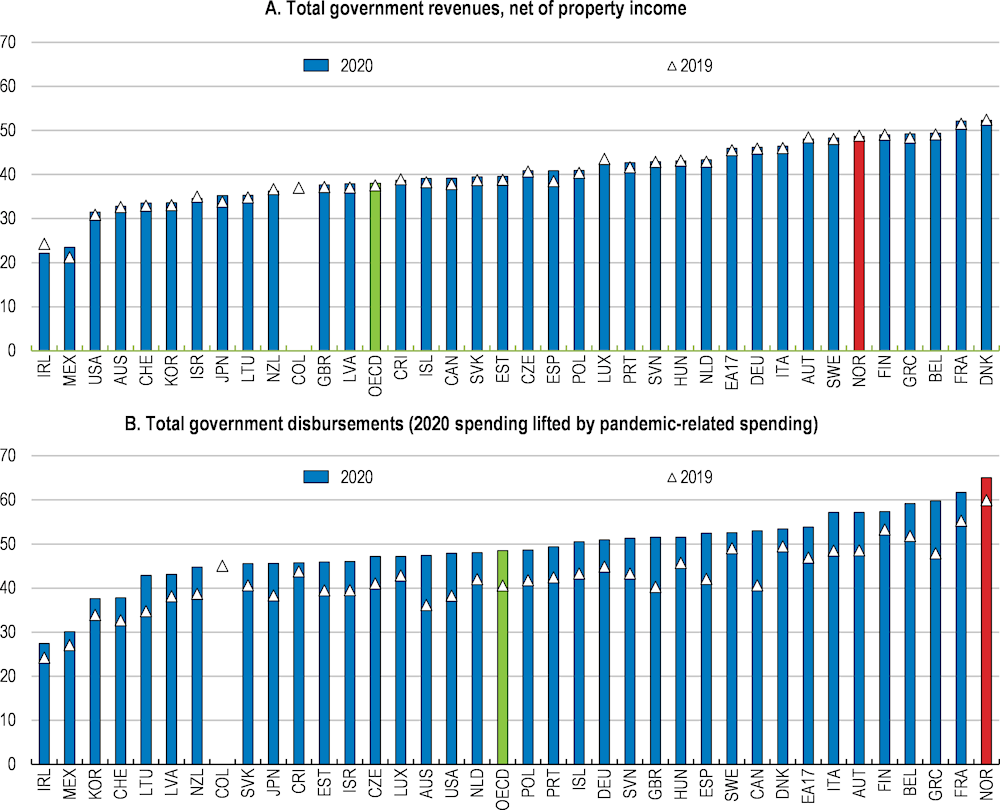

Like other Nordic countries, Norway’s public spending is comparatively high, reflecting a commitment to comprehensive public provision of services and welfare support integral to its socio-economic model. In any given year, Norway’s government outlays as a share of mainland GDP are often the highest in the OECD area (Figure 1.15). (Needless to say, the differences in public spending between Norway and other countries do not necessarily wholly reflect differences in provision. For instance, pension provisions in some other countries are centred on mandating saving into pension accounts that does not feature in public spending). Norway’s large outlays are partly funded by petroleum wealth through a fiscal system that allows it to run substantial mainland-economy budget deficits for the benefit of current and future generations (Box 1.6). Nevertheless, the tax revenues required are large and mainland Norway’s ratio of general government revenue to GDP is also among the highest in the OECD.

Figure 1.15. Norway’s socio-economic model involves high government spending and taxation

% of GDP

Note: Norway total general government mainland receipts minus mainland property income received, as % of mainland GDP; and total general government disbursements as % of mainland GDP.

Source: OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook (database).

Norway’s fiscal system worked well during the pandemic

Norway’s wealth-fund system (Box 1.6) has proved effective over the pandemic. Channelling public revenues from resource extraction into a wealth fund avoids the fiscal problems that can arise when such revenues feed directly into government balances; for instance when oil prices drop suddenly, as happened in the early phase of the pandemic. Indeed, the wealth-fund system operates counter cyclically; an oil-price drop generally triggers currency depreciation that usefully bolsters the value of the wealth fund (which invests in foreign assets) and consequently also the value of the guideline deficit. In addition, flexibility in the fiscal rule allows the deficit to run above the guideline in a given year (Box 1.6), providing scope for fiscal stimulus during a crisis.

Spending on special measures to help households and businesses is estimated to be equivalent to 4.1% of GDP in 2020 and 3% in 2021 (Table 1.7). Measures supporting companies accounted for 45% of the outlays, the largest item being a scheme supporting hard-hit businesses to cover fixed costs. Other pandemic support measures included extra support for households, typically through extensions to existing transfers and extra support to public services (notably health care).

Table 1.7. Estimated spending on special measures to support households and businesses during the pandemic

Total spending in each budget year, NOK billion

|

Group/sector supported by the measures |

2020 |

2021 |

Total |

% of Total spending |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Businesses |

69 |

31 |

100 |

44.2 |

|

Households |

19 |

20 |

39 |

17.4 |

|

Sectors of critical importance |

41 |

36 |

77 |

34.2 |

|

Culture, sports and volunteering |

6 |

4 |

10 |

4.1 |

|

Total |

135 |

91 |

226 |

100 |

|

Total, % annual mainland GDP |

4.1% |

2.8% |

Note: The amounts for 2020 are adjusted to 2021 prices.

Source: Ministry of Finance, Proposition to Parliament 51S, January 2022.

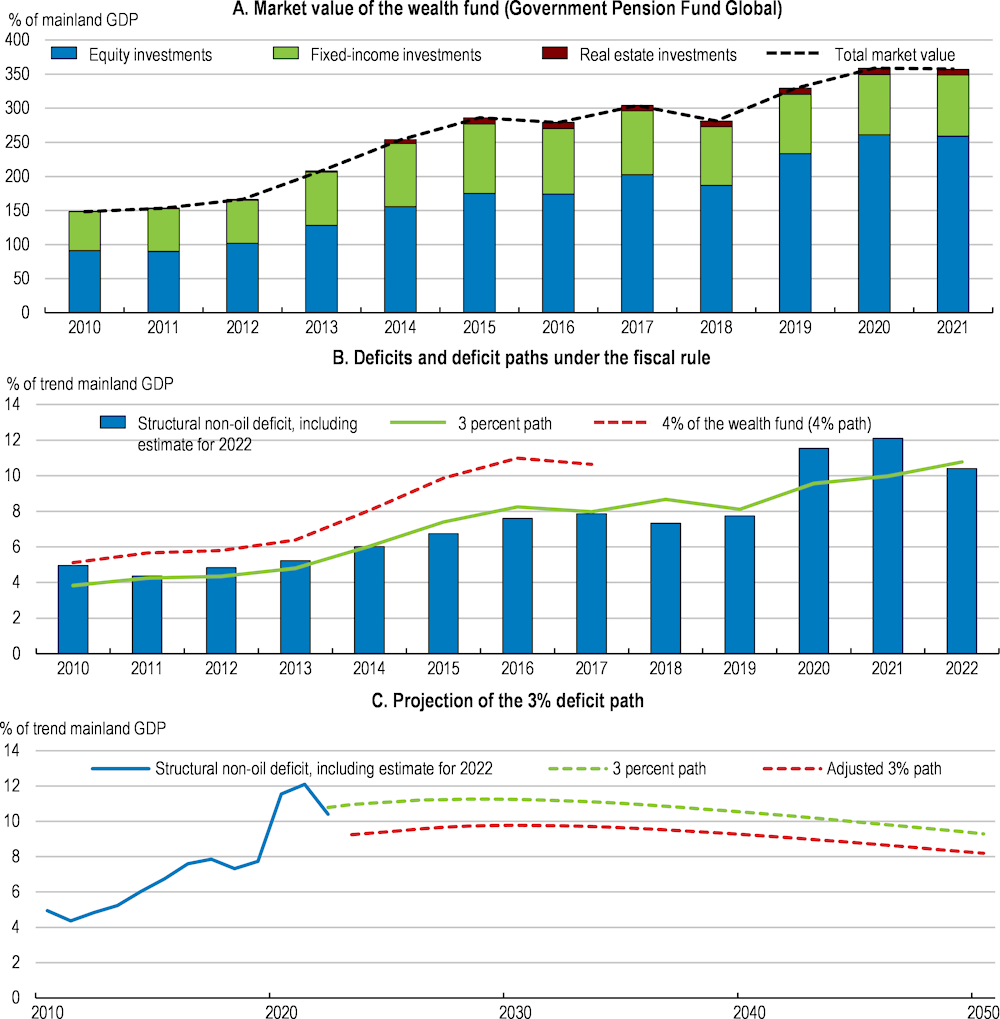

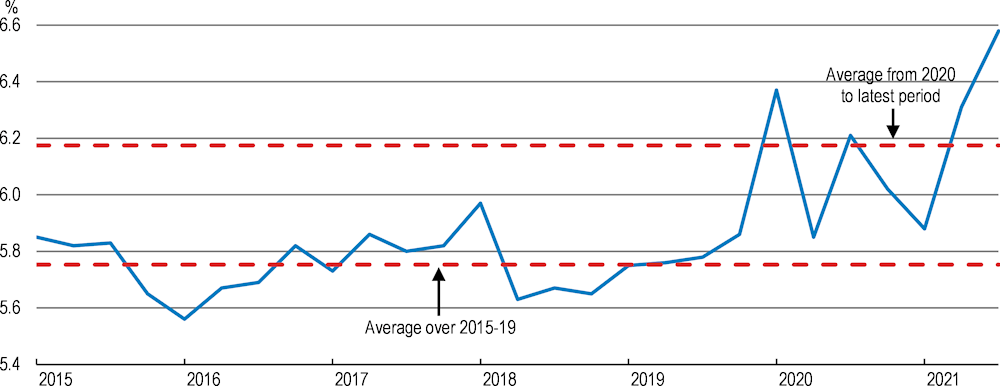

National Budget planning for 2022 has been appropriately prudent. The central government’s core mainland deficit measure (the “structural non-oil deficit”) is estimated to turn out at 11.6% of trend mainland GDP in 2021, well above the guideline deficit in the fiscal rule. With economic recovery well advanced, and significantly reduced need for pandemic financial support for households and businesses, the fiscal deficit should decline substantially. The National Budget for 2022, published in autumn 2021 budgeted for a deficit of 9.5% of mainland GDP, which is below the “3% path” guideline value (Figure 1.16, Panel C). With inclusion of the subsequent temporary support during the Omicron wave and for compensating high electriciy prices, the deficit is estimated to turn out at 10.4% of mainland GDP. This budgeting strategy reflects concern that downside risks on the returns to the wealth fund have increased. Indeed, the long-term perspective used in budget planning for 2022 includes downward adjustment in the guideline deficit (technically, the equivalent of NOK 1 000 billion at 2021 prices has been deducted from the value of the fund before calculation of the 3% guideline deficit values). (This adjusted 3% path is shown alongside the standard 3% path in Panel C of Figure 1.16).

Box 1.6. Norway’s fiscal system

Norway has used revenues from offshore petroleum production to accumulate a wealth fund (the Government Pension Fund Global, GPFG). Inflows to the fund comprise: i) net cash flow from the petroleum sector (i.e. revenue from the state’s direct financial interest plus tax revenues); ii) net financial transactions related to the petroleum sector; and, iii) returns on the fund’s assets. Under the fiscal framework, withdrawal from the fund covers Norway’s entire non-oil budget deficit. The fund, which has a value equivalent to around 3.5 times annual GDP, is invested entirely in foreign assets, which helps offset the currency appreciation arising from petroleum exports.

The Government Pension Fund Global is operationally managed by Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM), an arm of the central bank. The guidelines for the management are set by the Ministry of Finance and imply an index-near management strategy, with 70% equities and 30% bonds, and the possibility for the manager to invest in unlisted real estate and infrastructure for renewable energy within certain limits. NBIM as the operational manager has also put in place policies on investment and ownership strategies, including criteria on executive pay, board diversity, and sustainability reporting. In addition the Ministry of Finance has set ethical criteria for observation or exclusion of companies relating to certain products or companies’ conduct. In addition upstream oil and gas companies are excluded from the Fund due to considerations of oil price risk for the Norwegian economy. The Fund’s work on climate related risk has come under further scrutiny. In August 2021 an expert group established by the Ministry of Finance underscored need to further develop the climate risk strategy in the Fund’s investments, including that the fund should base its ownership work on an overall, long-term goal of net-zero emissions from the companies invested in (Ministry of Finance, 2021[6]). In September 2021 another expert group was established, in this instance to consider more broadly how the investment strategy of the Fund should be affected by geopolitical risks.

The fiscal rule states that the cyclically adjusted non-oil deficit (the “structural non-oil deficit”) should, over time, follow the expected real return on the Fund. The rule implies an intergenerationally fair use of oil wealth because spending the real returns implies leaving the real value of the Fund intact for future generations. Business cycle considerations are given significant emphasis which can lead the actual takeout rate to deviate from the 3% path both from one year to the next and over several years.

Since 2017 government budgeting has been based on a 3% expected real return to the fund. The expected return was previously estimated at 4%. The reduction was prompted by concerns of declining global rates of return. The rule alteration was also timely given the cyclical situation. Under the “4% rule” and with rapid growth in the wealth fund (Figure 1.16), the guideline deficits had risen substantially. In the decade 2007-2016, the structural non-oil deficit increased by 0.5 percentage points of GDP each year on average (Figure 1.16).

In sum, the rule enables Norway to sustainably run a large non-oil deficit, currently in the order of 10% of GDP (Figure 1.16). In effect, the oil wealth means that households and business benefit from lighter taxation and more public spending on services and investment than would otherwise be the case. If Norway’s fiscal rule is closely adhered to, all future generations stand to benefit. Governments in most other countries can, at best, only afford to run modest fiscal deficits during normal economic times, typically less than two percent of GDP. Some countries have to aim for balanced budgets to contain public-debt burdens and to build fiscal space to respond to negative shocks.

Figure 1.16. The structural non-oil deficit will have to trend downwards over the long term

Note: “3% deficit path” shows 3% of projected wealth-fund value as a percentage of trend mainland GDP. The “adjusted 3% path” shown in Panel C was incorporated in the long-term perspectives used to guide the 2022 Budget. It includes a downward adjustment to reflect assessment of elevated risk to returns to the wealth fund looking forward.

Source: Norges Bank Investment Management (MBIM); and Ministry of Finance, National Budget 2022.

Diminishing fiscal space ahead

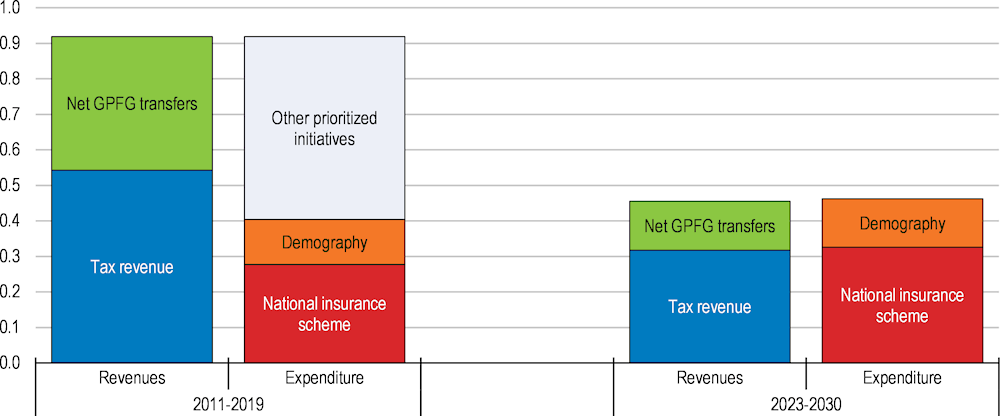

The prudent government budgeting for 2022 sets an appropriate precedent as fiscal space is set to shrink in the coming years compared with conditions prior to the pandemic. Between 2011 and 2019, governments spent around 0.5% of GDP extra each year on additional initiatives (Figure 1.17). Growth in mainland tax revenues and the wealth fund provided headroom to cover structural growth in spending on transfers from demographic changes and demands on national insurance, with room to spare for additional initiatives. Ministry of Finance projections suggest that the fiscal space created by tax and wealth-fund transfers (in line with the fiscal rule) will approximately halve in the coming years. This reduced space will only just cover estimates of structural growth in spending, which is mainly due to outgoings relating to population aging. This implies no room for additional initiatives unless funded from measures that make efficiency gains in public spending or generate more revenues.

Figure 1.17. Scope for new spending will diminish in the coming years

Average annual increase in revenue or spending, % of 2021 mainland GDP

Note: "Demography" is an estimate of the increasing health care costs due to population ageing. "National Insurance Scheme" mainly reflects increasing costs in pensions and disability benefits. The NOK values in the calculations are re-based to 2021 and therefore 2021 mainland GDP is the denominator.

Source: Ministry of Finance and OECD calculations.

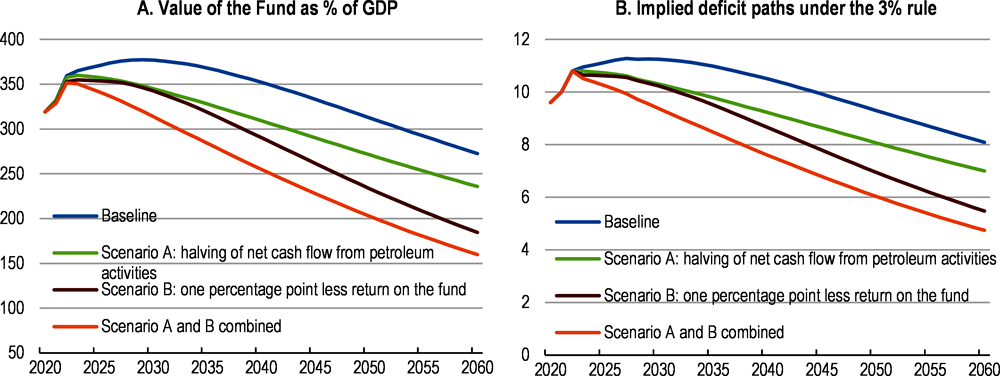

Furthermore, there will be even less fiscal space if cash flow from petroleum activities or returns to the fund are weaker than expected. As reflected in the downward adjustment in the guideline deficit, with attention to climate change gathering momentum globally, the risk of a faster-than-expected decline in cash flow from petroleum activities over the medium and long term has increased.Figure 1.18 illustrates that a halving of the cash flow from the petroleum fund could mean a steady decline in the deficit from 2030 onwards. Cash flow from the petroleum fund could, for instance, decline in the event of an accelerated wind down of petroleum production. If this was combined with a reduction in the return to the fund then declines in the implicit deficit would begin almost immediately. A trend decline in the return to the fund could, for instance, occur in the event of a global weakening in stock market valuations.

Figure 1.18. Fiscal sustainability: illustrative scenarios

Note: The baseline scenario is from Ministry of Finance estimates. The same nominal GDP growth is assumed in all scenarios. The basic 3% guideline is shown in the calculation, not the variant applied in the 2022 Budget that made an adjustment for financial risk.

Source: Calculations based on Ministry of Finance data.

Continued firm commitment to and conservative interpretation of the fiscal rule will be important as the trade-offs sharpen between revenues and spending in the years ahead. Public understanding and commitment to the fiscal rule have proved encouragingly robust in the past, albeit in a period where the value of the fund has trended strongly upwards. Maintaining strong commitment in the coming years underscores the importance of:

Ensuring the non-oil deficit declines in line with the diminishing need for economic support as the economy recovers, as envisaged in the 2022 National Budget.

Continuing to base fiscal planning on prudent projections of the Fund’s value, including through use of haircut adjustment to account for risks, as exemplified in the 2022 National Budget and the Long Term Perspective report. Planning on the basis of conservative estimates of inflows to the fund (see Box 1.6) reduces the risk of policies that add multi-year spending commitments which could prove unaffordable if the Fund’s value turns out lower than projected. Prudent estimates also strengthen capacity of the fiscal system to handle shocks to fiscal balances, such as that experienced during the pandemic.

Continued good communication with the press and the public on the principle of the fiscal rule, how it works and the benefits for current and future generations.

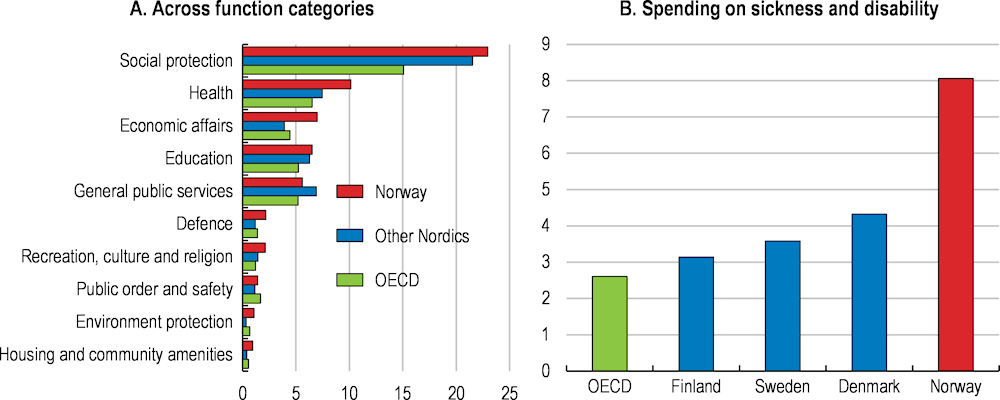

Making public services more efficient and ensuring wise public investment choices

With reduced fiscal room, government spending must become more efficient. Past Surveys have highlighted several areas where Norway’s comparatively high public spending could be made more effective. Public spending on social protection (this includes, for instance, support for low-income households, old-age pensions, disability support), and to an extent health care, distinguishes Norway, and the other Nordics, from most other OECD countries (Figure 1.19). For instance, in 2019 Nordic social protection spending was equivalent to over 20% of GDP, compared with an OECD average of 15%. Ensuring the substantial social protection spending achieves goals efficiently is therefore particularly important. In Norway, sick-leave compensation and disability support are widely recognised as in need of reform (discussed further below). In addition, Norway’s comparatively high spending on the category of Economic Affairs (Figure 1.19) in part reflects slow progress in unwinding support for the agricultural sector (discussed further below). Past Surveys have also found weak spots in Norway’s selection processes for large scale infrastructure projects.

Efforts to identify scope to improve specific areas of public spending should continue, including through the ongoing process of spending reviews. Recent years have seen reviews in a number of areas (Box 1.7). Such reviews need to ensure, inter alia, that opportunities for efficiency gains and quality improvements in government services via digitalisation are fully exploited. Norway scores well on indicators of the uptake of government digital services. However, there is almost certainly scope for further development of services.

Box 1.7. Public spending reviews in Norway

Given Norway’s extensive publicly funded services, ensuring good quality, and value for money is particularly important. It matters for remaining on target with budgets and for building headroom for new policy initiatives. It also helps towards trust in government and strengthens acceptability of the relatively high tax burdens required to fund public spending.

One way to ensure quality and value for money in public services is through spending reviews. These are frequently used in Norway and in recent years have covered:

Costs and price mechanisms of medicines under the National Insurance Scheme.

Management of the Police.

Efficiency and effectiveness of the Foreign Service (ongoing).

Policy instruments to promote Norwegian businesses abroad.

Identity system management.

Norwegian Public Roads Administration.

Climate Support Schemes.

Structure and administration of Municipal transfer systems.

Organisation and efficiency of government construction and property management.

Business support and financial means system.

Housing solutions and health and care services for the elderly (ongoing).

Budgeting processes should continue to incentivise improvements in the quality and cost efficiency of public services. In recent years central government budgeting has featured “efficiency dividends”, small annual reductions to baseline budget allocations to ministries and agencies (Box 1.8). Such a mechanism, or similar, should continue to feature in budget processes, and could be extended to regional and municipal budgeting. In a similar vein, past Surveys have suggested the introduction of medium-term expenditure frameworks (MTEFs). The authorities have previously given this proposal detailed consideration but judge it to be it unsuitable in the Norwegian context. A commonly expressed concern is that in Norway multi-year spending paths for ministries and agencies may in practice act as floors, rather than ceilings, on expenditure. However, as the challenges in containing existing spending and funding new spending mount, the potential advantages of a medium-term expenditure framework may increase. Given the prospect of more limited fiscal space in the coming years, policymakers should remain open to augmenting the fiscal system with medium-term benchmarks for items of discretionary and non-discretionary spending.

Figure 1.19. Public spending on social protection is particularly high in Norway and the other Nordic countries

General government spending, 2019, % of GDP

Note: The spending levels do not necessarily reflect overall levels of service, inter alia, due to variation across countries in the degree of private‑sector provision particularly in health care and education. Differences across countries in the use of tax (as opposed to spending) instruments and differences in how transfers are taxed are also considerations.

Source: OECD (2021), National Accounts (database).

Box 1.8. Norway’s budget “efficiency dividends”

Norway’s central government budget process includes “efficiency dividends”. These are small reductions to the baseline budget allocations (usually a 0.5% reduction from the baseline) to ministries and agencies. The proceeds of the reductions are pooled to fund new policy reforms or high priority tax or spending measures. The concept is that the allocation reductions prompt public-sector management to exploit headroom for efficiency gains, while also providing fiscal space for new spending measures.

According to the new government’s political platform, the efficiency dividends will be replaced by targeted processes and efficiency goals. In principle this can be a better way of achieving efficiency gains in government spending compared with uniform across-the-board cuts or efficiency devices like the dividends. However, properly identifying where the greatest scope for efficiency gains lies across Ministries and other spending bodies and operationalising this in budgets can be challenging both technically and politically.

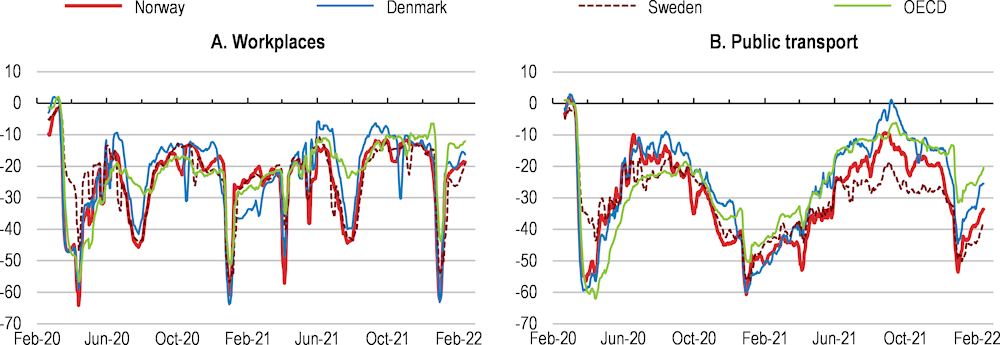

Recent years have seen progress in tax reform

Pre-pandemic, one focus of tax policy was on lowering the tax burden, particularly that for businesses. Notably, the rate of “ordinary tax”, which applies to most forms of income – including corporate income – was reduced in a series of steps from 28% to 22% between 2013 and 2019. This has made Norwegian business taxation compare more favourably with that of other countries.

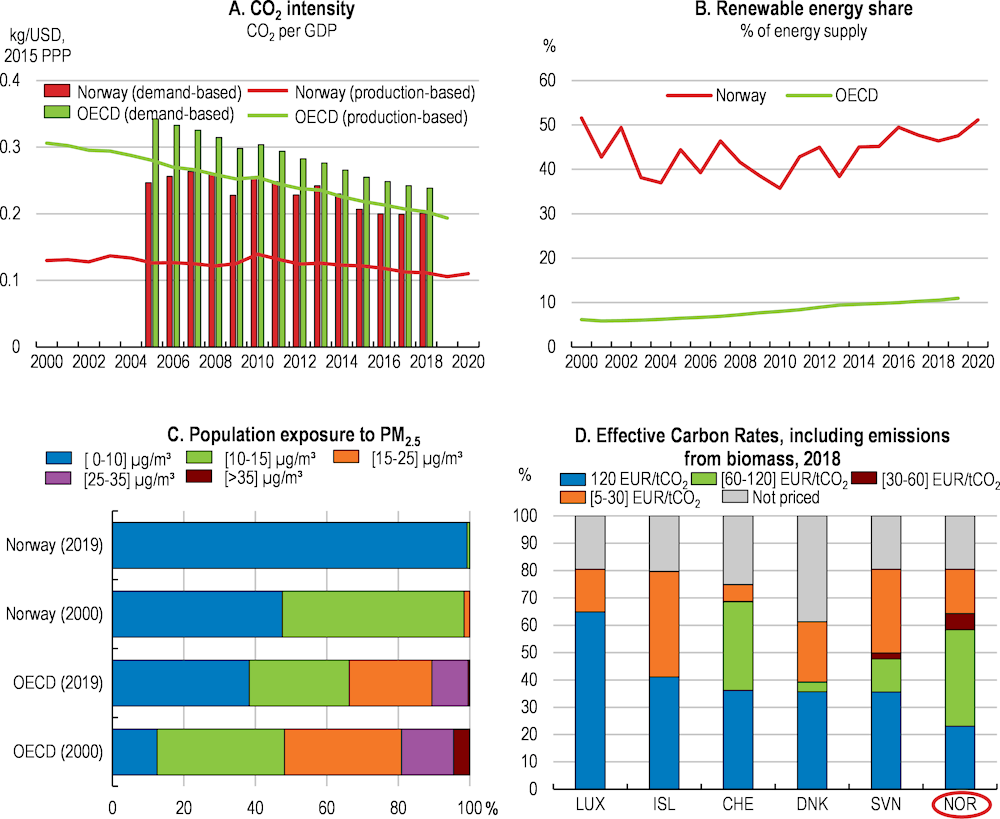

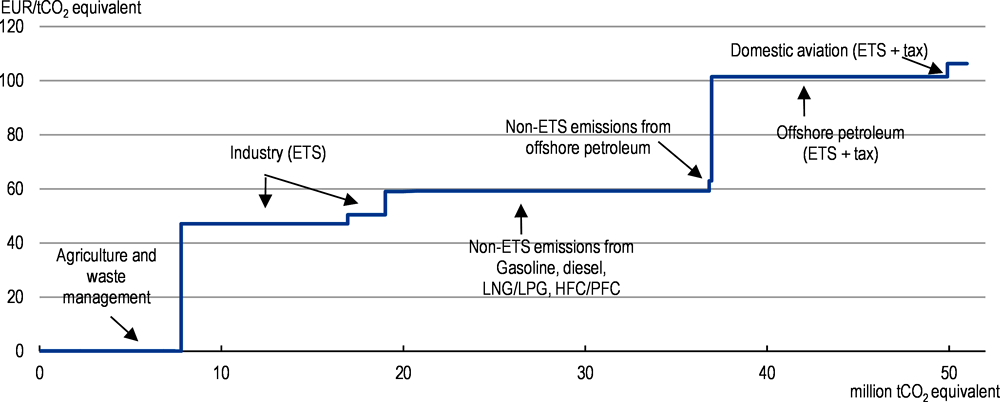

Policy in recent years has improved the consistency of tax rates and broadened tax bases. Some concessionary rates of VAT have been raised, thus narrowing differences in rates across goods and services. In addition, a financial activity tax has been introduced that aims to compensate for the absence of VAT on financial services (as in other countries, establishing value added from financial services for taxation purposes is challenging). In addition, Norway is making progress in tackling base erosion and profit shifting in corporate taxation. Further advances on these fronts would be welcome. Establishment of a committee on taxation with a broad remit in June 2021 provides opportunity to do so.