This introductory chapter provides an overview of the economic, social and administrative context for public governance reform in Paraguay. It places the country’s reform efforts in the context of a history marked by a long dictatorship and a democratization process that only started in 1989. Through this contextualisation, the chapter aims to provide the basis for an understanding of the most pressing public governance challenges the country is facing. It finds that Paraguay’s strong macroeconomic performance, improving socio-economic indicators as well as the ambitious National Development Plan provide a major opportunity for reforms, but also flags that low levels of citizen trust and inequalities as well as a lack of inclusiveness remain key challenges that need to be addressed through a public governance reform agenda that is integrated into the development strategy to foster inclusive growth.

OECD Public Governance Reviews: Paraguay

Chapter 1. Setting the scene: Good governance for a more sustainable and inclusive Paraguay

Abstract

Introduction

Paraguay, a landlocked country with a population of just under 7 million people, is situated in the heart of South America and shares borders with Brazil, Argentina and Bolivia. One of the last South American countries to overcome dictatorship, it was in 1989 that Paraguay started a slow move towards democracy. Coups d’état, recurrent political and economic crises and widespread corruption have left strong marks on the country’s governance frameworks. Notwithstanding Paraguay’s difficult past, recent socio-economic achievements have been remarkable: the country has become one of the most dynamic economies of the continent with annual economic growth rates well above the OECD and Latin American averages. Thanks to a strong macroeconomic performance and to important structural reforms, many Paraguayans have overcome poverty and middle classes have started to emerge.

Nevertheless, the country remains highly unequal; poverty is far from eradicated and more needs to be done to create well-paying formal jobs for all Paraguayans. Paraguay’s National Development Plan (NDP) 2030, adopted in 2014, recognises these challenges and provides the country with a long-term strategic development vision. Addressing the country’s most pressing socio-economic challenges and achieving the NDP’s vision require an effective, efficient, strategic, open and transparent state. In recognising this, the Government of Paraguay asked the OECD to conduct a Public Governance Review; this Review thus provides practical advice and recommendations to the government of Paraguay to support its efforts in tackling key public governance barriers to inclusive and sustainable growth.

This introductory chapter provides an overview of the economic, social and demographic context for public governance reform in Paraguay. This chapter is divided into four parts:

Starting with the country’s independence from Spain in 1811, the first section analyses Paraguay’s recent history in order to provide the necessary background for an understanding of the challenges Paraguay’s public administration is facing;

The second section presents Paraguay as it stands today, including the country’s main socio-economic achievements and key challenges that need to be addressed;

Section three then discusses the NDP, the vision for Paraguay in 2030;

The last section discusses how public governance reform can be a tool for the country to achieve its ambitious vision and ultimately create a state that delivers high-quality public services and increasing living standards for all Paraguayans.

The past: a history marked by frequent changes of government

Paraguay has seen political instability and long periods of dictatorship for almost two centuries. The country’s history has left a deep mark on today’s democracy and influences the functioning of the public sector. This section introduces the key milestones of Paraguay recent history, starting with the country’s independence in 1811 and ending with the introduction and slow consolidation of democracy beginning in 1989. Through this historical contextualisation, the section aims to provide the basis for an understanding of the most pressing public governance challenges the country is facing nowadays.

1811-1954: Independence from Spain, wars and the definition of Paraguay’s territory

Paraguay became independent from Spain in May 1811. In the years following its independence, the country was governed by Jose Gaspar Rodriguez de Francia (from 1814 to 1840), Carlos Antonio Lopez (1841-1862), and Francisco Solano Lopez (1862-1870). It was during Solano Lopez’ Presidency that Paraguay engaged in its first major international conflict. The “War of the Triple Alliance” (1864-1870) was fought with Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay over disputed territories. The bloodiest war in the history of Latin America resulted in conditions that would block Paraguay’s industrialisation and social progress for decades (Marine Corps Intelligence Activity, n.d.): the country’s population was decimated, its national territory was considerably reduced and Paraguay had to pay enormous reparations to Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay (some of these reparations were subsequently pardoned). In the years following the war, Paraguay was characterised by considerable political instability: 21 governments succeeded each other over 30 years (Ibid.). Between 1904 and 1954, Paraguay had thirty-one presidents, most of whom were removed from office by force (Hanratty et al., 1990).

In the 1930s Paraguay involved itself in another major international conflict: the “Chaco War" (1932-35) was fought between Paraguay and Bolivia over the Chaco territory, believed to be rich in oil. Paraguay won the war; the treaty of Peace, Friendship and Boundaries, signed in 1938, established new borders between the belligerents. The political aftermath of the war brought mutinies and rebellions from returning soldiers and officers; the Chaco War marked the end of Liberal governments in Paraguay. The following the years were once again characterised by political instability.

In 1939, the commander-in-chief during the Chaco War, José Félix Estigarribia, was elected president. Estigarribia launched one of the country’s first major state-reform agendas, including land reform, major public works, attempts to balance the budget and monetary and municipal reforms. In August 1940, a plebiscite endorsed a new Constitution, which remained in force until 1967. The Constitution expanded the power of the Executive branch to deal directly with social and economic problems while promising a “strong, but not despotic” president.

The Estigarribia Presidency ended in September 1940, when the President died in an airplane crash. Power was taken by Higinio Morínigo, an army officer, who cancelled most of Estigarribia’s reforms. In 1947, Morínigo was challenged by an uprising of Liberal, Febrerista and Socialist groups, resulting in a brief but bloody civil war. The civil war ended with the victory of Morínigo’s faction and the consolidation of his alliance with the Colorado Party (founded in 1887).

The 1950s and 1960s: The beginning of the Stroessner dictatorship

In 1954, General Alfredo Stroessner Mattiauda, a member of the Colorado Party, overthrew the sitting President, Federico Chaves. The Stroessner regime would remain in power until 1989 and leave a strong mark on Paraguay that can still be felt today (Nickson, 2011). Between 1954 and 1989, Paraguay was in effect a dictatorship. The state was under complete control of Stroessner’s Colorado party and the armed forces (Abente Brun, 2011).

The early years of Stroessner’s dictatorship saw relative political stability and economic growth. A Stabilization Plan with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was agreed in 1956. The plan aimed to reduce inflation, boost trade and strengthen the economy (Government of Paraguay, 2017). The Stroessner regime managed to attract significant amounts of foreign investment, which contributed to an average economic growth rate of 4.5% in the 1960 (and GDP per capita growth of 1.8% per year). However, the rural population benefited to a lesser extend from this relatively positive scenario and many young people migrated to Argentina (Nickson, 2011) or were exiled.

By the 1960s, the Stroessner regime had acquired total control over politics in Paraguay. Other political parties were either isolated or lent legitimacy to the political system by willingly participating in Stroessner’s “fake elections” (Hanratty et al., 1990). The most prominent figures of the internal opposition within the Colorado Party had gone into exile. The party became a political instrument loyal to Stroessner and the armed forces (Nickson, 2011).

The 1970s and 1980s: From the construction of the Itaipu dam to Paraguay’s recession during the Latin American “lost decade”

While Stroessner clearly represented continuity with Paraguay’s authoritarian past, the dictator also managed to drag the country out of its international isolation. In the 1970s, the Paraguayan economy achieved a significant boost, mainly due to the construction of the Itaipu dam over the Paraná River at its border with Brazil. Overall, in the period between 1970 and 1979 GDP grew at an average annual rate of 8.3%, and GDP per capita grew at a rate of 5.6% (Government of Paraguay, 2017).This economic performance delivered better opportunities to citizens, contributed to the growth of a middle class and reduced migration from rural areas to the urban centres (Ibid.).

The dynamism of the Paraguayan economy was suddenly interrupted in the 1980s. The international economic environment had deteriorated due to rising interest rates, falling commodity prices, and the appreciation of the US dollar (Government of Paraguay, 2017). In addition, the completion of the Itaipu dam led to a significant reduction in foreign exchange earnings. Thus, after growing uninterruptedly for two decades, the Paraguayan economy fell into recession in 1982 and 1983 (Government of Paraguay).

This deteriorating economic scenario motivated the government to accelerate public investment (Government of Paraguay, 2017). As a consequence, external public-sector debt increased from 18.3% of GDP to 51.4% in 1985. These negative economic factors accelerated an institutional breakdown, fuelled by an emerging internal opposition as well as the increasingly vocal condemnation by foreign governments of the Stroessner regime for its repression of political opposition and its reliance on electoral fraud (Hanratty et al., 1990).

Since 1989: A democracy in the making

On 3 February 1989, a coup d’état led by Stroessner's son in law, General Andrés Rodriguez, ended 34 years of authoritarian rule and Paraguay began a long (and sometimes arduous) process of transition to democracy. Shortly after the coup elections were held. The Colorado Party received the mandate to finish Stroessner’s Presidential term (until 1993) with the strongest opposition support awarded to the Liberal party with 20% of the votes. The elections also decided the composition of a new Constituent Assembly that was assigned the task of preparing a new democratic Constitution.

The end of the Stroessner regime marked the launch of significant structural changes to Paraguay’s economy and society. The country became a founding member of the Southern Cone Common Market group (MERCOSUR) in 1991. In the same year, Paraguay held free municipal elections. A new democratic Constitution drafted by the Constituent Assembly came into force in June 1992. Article 1 of the new Constitution established Paraguay as an independent and free republic and its government system as a “representative democracy”. It forbids presidential re-election and establishes a set of civic, political and social rights. According to Abente Brun (2011), the Constitution provides for a model with a weak Executive and a strong Parliament. The Constitution also launched a process of decentralisation of the public administration through the creation of governorates and the transfer of taxing authority to municipalities (Government of Paraguay, 2017).

On 9 May 1993, the nation held its first free democratic parliamentary and presidential elections in many decades. The Colorado Party won a simple majority of seats in Parliament, and its candidate, Juan Carlos Wasmosy, became President. However, the elections were preceded by internal power struggles within the Colorado Party between the reformist wing, headed by Wasmosy, and the traditional wing led by Luis María Argaña (OECD, 2018). The electoral process was contested and fraud was later acknowledged by the winning Wasmosy wing.

The 1998 elections once again saw power struggles within the Colorado Party. General Lino Oviedo, who had led a failed coup against President Wasmosy in 1996, was selected as the party’s candidate. However, shortly after winning the nomination he was imprisoned for the 1996 attempted coup. From jail, General Oviedo supported the candidacy of Raúl Cubas Grau as President and Luis María Argaña as vice-president. When Cubas Grau was elected President, he immediately commuted Oviedo’s sentence (Ibid.).

In 1999, Vice-President Argaña was murdered. Both President Cubas, who was facing impeachment from Congress, and General Oviedo, who was supposedly linked to the crime, fled Paraguay shortly thereafter (Cubas resigned before fleeing). Consequently, Luis González Macchi from the Colorado Party, then the president of the Congress, became President to complete the term. In the 1999 elections to replace the murdered Vice-President, Julio César Franco from the opposition Authentic Radical Liberal Party (Partido Liberal Radical Auténtico, PLRA) was elected, thereby creating tensions within the government. Congress tried to impeach Gonzalez Macchi in 2003, but the motion failed to secure sufficient votes.

The Colorado Party once again prevailed in the 2003 elections. President Nicanor Duarte Frutos’ term was relatively stable and was marked by strong economic growth. However, Duarte Frutos also launched efforts to reform the Constitution to allow for his re-election, resulting in widespread popular protest.

In 2008, in electing to the presidency Fernando Lugo, who represented a coalition of opposition parties, Paraguayans put an end to the Colorado Party’s hegemonic regime that had lasted 61 years (Ibid.). Lugo’s government made a first attempt to reform the Executive branch in co-operation with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). However, the project was never introduced into Congress and was later abandoned (Government of Paraguay, 2017). Lugo would remain in power until 2012 when he was impeached by Congress over his handling of a violent confrontation between farmers and the police.

In 2013, Horacio Cartes, a businessman from the Colorado Party, was elected President. Cartes’ government programme focused on reforming the public sector, while seeking private-sector financing to improve Paraguay’s infrastructure (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2017). Under President Cartes relations with Paraguay’s neighbours and with countries around the world have considerably improved. In addition to re-establishing closer relations with MERCOSUR, President Cartes has actively pursued global and regional re-integration (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2017).

The Cartes administration was the first in many years to make the issue of public governance reform a national priority. The government has followed through on some of governance reform projects that had been launched under previous governments, including reforms in the areas of public procurement, human resources management and open government. This administration’s governance-reform priorities also include working with the OECD and the European Union on this OECD Public Governance Review. Arguably its most important initiative in this area was the articulation of an integrated National Development Plan with a planning horizon to 2030 (see below).

The present: strong macroeconomic performance and improving socio-economic indicators but low levels of trust and of government capacity

The past has left deep marks on Paraguay’s democracy and the functioning of the country’s public administration. Despite its difficult history, Paraguay has made great socio-economic progress in recent years and today stands out as one of the most dynamic economies in the region. Macroeconomic performance has been strong, contributing to an increase in the standards of living of many Paraguayans.

While recognising these important achievements, this section highlights that more needs to be done to foster more inclusive growth and to strengthen citizens’ trust in the institutions of the state.

Macroeconomic performance has been strong

Paraguay’s economy is in a relatively healthy situation. Public debt is low, inflation is under control and the fiscal balance is stable (European Union, 2017). Partly thanks to continued high demand for its agricultural commodities (Paraguay is one of the world’s most important producers and exporters of soybean, corn, wheat and beef), the country has not suffered from the financial crisis as strongly as some of its neighbours. Overall, Paraguay has experienced relative robust economic growth (averaging at 5% per year) over the past decade (Government of Paraguay, 2017). However, as highlighted in the OECD Multi-Dimensional Country Review of Paraguay (OECD, 2018), growth has been volatile, mainly because of the importance of agriculture in the economy and the concentration of exports in primary agricultural products and their derivatives.

A remarkable reduction of extreme poverty and increased human development

Positive macroeconomic developments and structural economic reforms have had a real and positive impact on increasing people’s income and purchasing power and on reducing poverty. Paraguay’s poverty rate fell from 45% in 2007 to 27% in 2015 (according to national data), with extreme poverty falling from 14% to 5.4% over the same period (DGEEC, 2017). According to the OECD (2018), the fall in poverty rates has been largely driven by growth in incomes across the population rather than by increased redistribution. Macroeconomic stabilisation has also contributed to containing poverty by limiting food price inflation (Ibid.).

Development indices also show significant progress. Between 1990 and 2015, Paraguay’s Human Development Index (HDI) value increased from 0.580 to 0.693, an increase of 19.5% (UNDP, 2016). In particular, remarkable progress has been made in some of the HDI’s sub-components. For instance, between 1990 and 2015, Paraguay’s life expectancy at birth increased by 5.0 years, mean years of schooling increased by 2.3 years and expected years of schooling increased by 3.7 years (Ibid.).

Inequality has been reduced but enhancing inclusiveness is one of the country’s key challenges

Inequality has been reduced, but remains high. Paraguay’s Gini Index fell from 0.55 in 2000 to 0.48 in 2016 (Government of Paraguay, 2017). Notwithstanding this progress, income inequality and in particular inequalities between urban and rural areas remain among the highest in Latin America. Access to social insurance, water and sanitation is significantly worse in rural areas (OECD, 2018).

As pointed out by the OECD (2018), enhancing the inclusiveness of its development path is one of the key challenges Paraguay is facing. However, the OECD (2018) also explains that “the capacity of the state to affect inequality in living standards is constrained by its limited capacity to deliver quality public services to all, in particular across territories, and the low impact of the fiscal taxation and transfer system on poverty and inequality”, pointing to the need for comprehensive public governance reform.

Low government capacity and lack of trust in institutions put pressure on the country

In 2015, government expenditures in Paraguay were at 25% of GDP compared to 34% in LAC countries and 45% in OECD countries (OECD, 2018). At 9.8%, the share of public employment as a share of total employment is relatively low when compared to LAC (12%) and OECD (21%) averages. While in recent years both of these shares increased, government capacity remains fairly limited, challenging its ability to respond rapidly and consistently to rising citizens’ expectations and demands (OECD, 2018).

As outlined in the 2018 Multi-Dimensional Country Review, “as Paraguay speeds up the pace of its economic and social development, the size and expectations of the middle class are expected to increase and consequently the number and complexity of tasks requiring government intervention” (OECD, 2018). Only 28% of the Paraguayan population reported trusting their government in 2016, three percentage points lower than in 2006. According to the data from the Latinobarometro (2015) less than one quarter of Paraguayan citizens is satisfied with how democracy works in their country and less than half the population considers that democracy is preferable to any other form of government (Ibid.). Moreover, 37% of the population consider that in some circumstances an authoritarian government is preferable to a constitutional one, an illustration of how deep the marks of the country’s history are still felt, and of how much further governance-reform efforts need to go to restore the public’s trust in the institutions of democratic government to serve citizens in a way that meaningfully meets their needs.

The vision: An ambitious National Development Plan for 2030

The National Development Plan (NDP) “Building the Paraguay of 2030” (Construyendo el Paraguay del 2030), adopted by presidential Decree No. 2794 in 2014, aims to address the country’s key challenges and articulates the government’s strategic long-term development vision for the country. The NDP seeks to guide and co-ordinate actions of the Executive branch with the different levels of government, civil society, the private sector and, eventually, the Legislative and Judicial branches.

The NDP projects an ambitious agenda to create a “democratic, supportive state, subsidiary, transparent and geared towards the provision of equal opportunities” (Government of Paraguay, 2014). The Plan was developed following a wide consultation process that included the central government as well as subnational authorities, civil society organisations and other relevant stakeholders. The NDP’s objectives are supposed to be reached through “a broad alliance between an open government, socially responsible private companies, and an active civil society”.

The implementation of the plan is led by the Technical Planning Secretariat (Secretaría Técnica de Planificación, STP) in the Presidency of the Republic. The STP is assisted by a national committee of citizens from the private sector, academia, and civil society, the Equipo Nacional de Estrategia País (ENEP) which monitors the implementation of the NDP (see Chapter 6 on Open Government).

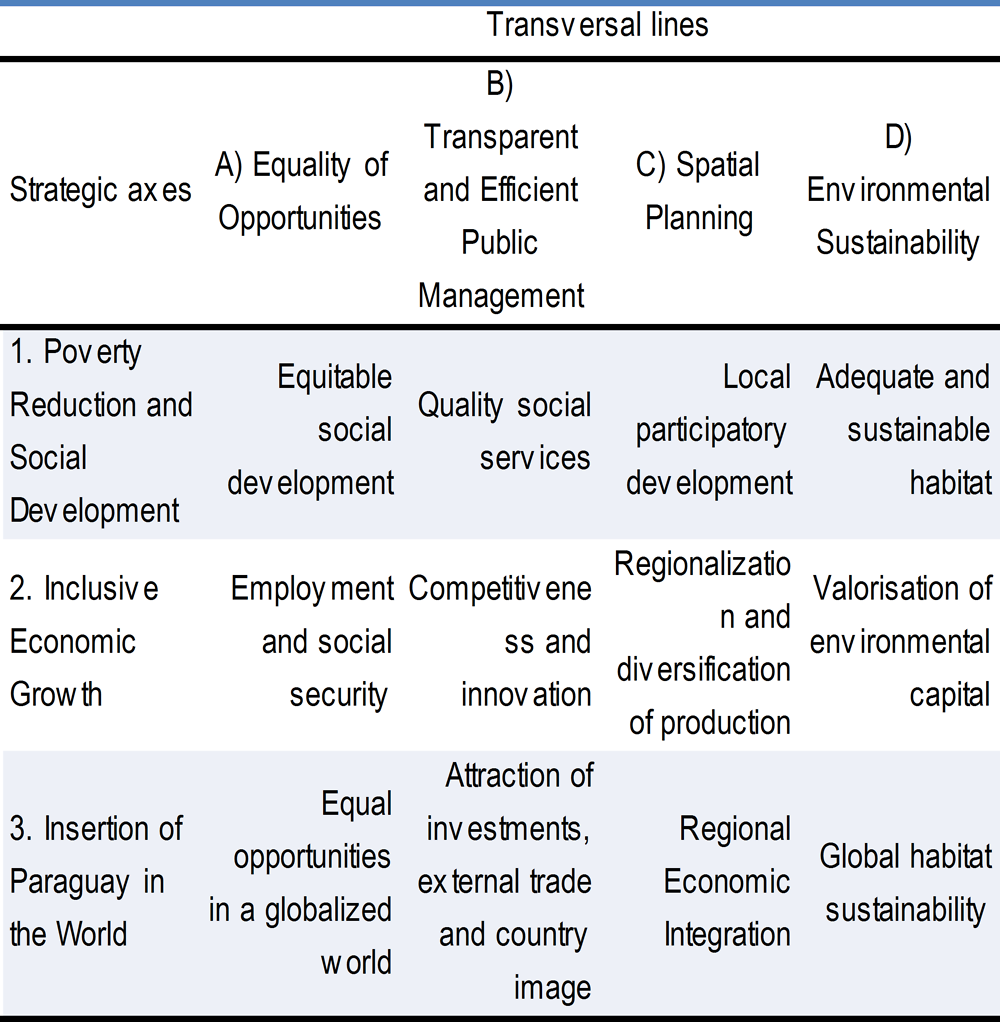

The NDP is structured around three strategic axes:

Reduction of Poverty and Social Development;

Inclusive Economic Growth; and

Insertion of Paraguay in the World.

It extends across four transversal, cross-cutting themes:

Equality of Opportunities;

Transparent and Efficient Public Management;

Territorial Planning and Development; and

Environmental Sustainability.

Taken together, the axes and strategic lines result in 12 general strategies which all have a monitoring framework as well as respective sector-specific objectives that are linked to budget proposals. According to article 177 of the 1992 Constitution all public institutions are obliged to comply with the NDP and it is indicative for private sector actors.

Figure 1.1. The strategic framework of Paraguay’s National Development Plan

Source: Government of Paraguay (2014), Plan Nacional de Desarrollo Paraguay 2030, www.stp.gov.py/pnd/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/pnd2030.pdf

As for public governance, the NDP highlights the need for better co-ordination of functional tasks to overcome existing institutional fragmentation, better use of resources with lower levels of corruption and better information being made available to the public about the administration’s activities as key elements to guarantee a “supportive and open state, which guarantees rights without discrimination and tolerance for corruption” (Government of Paraguay, 2014).

Public governance reform as a means to an end: addressing socio-economic challenges and achieving the country’s long-term strategic vision

Addressing the socio-economic and political-administrative challenges discussed above and achieving the ambitious vision outlined in the National Development Plan 2030 require a state that is capable of steering the country’s development and making it more inclusive. Strong institutions are of key importance for sustaining inclusive development over time (OECD, 2018). Hence, sound public governance and reforms to achieve it should be seen as a means to an end: implementing the country’s long-term strategic vision of a more inclusive and sustainable Paraguay for all Paraguayans.

OECD work on Public Governance for inclusive growth

The OECD Public Governance Review of Peru (OECD, 2016) elaborates on the connection between good public governance and inclusive growth. OECD research (see for instance OECD, 2015) shows that public governance plays an essential role in achieving sustainable economic growth and narrowing inequality in all its dimensions. Government capacity and quality of government have strong effects on almost all standard measures of well-being, and on social trust and political legitimacy. Governance failures lead to increasing inequalities (OECD, 2015) while good governance can contribute to a more equal society (OECD, 2016).

There is today a broad evidence-based consensus that good governance is key to pursuing a number of important policy outcomes at the national and subnational levels, including but not limited to social cohesion through service design and delivery that meaningfully improve results for the citizens who use them, public expenditure efficiency or the fight against corruption. Coase (1960) argues that a good institutional and legal framework under the rule of law, such as strong property rights, reduce transaction costs and consequently support economic development. Similarly, North (1991) contends that institutions that strengthen contract enforcement are necessary to economic development. More recently, Rodrik, Subramanian and Trebbi (2004) empirically found that the quality of institutions is more important for growth than geography or trade. Other scholars (e.g. Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012) argue that institutions, including an efficient public sector and absence of corruption, are the fundamental drivers of economic growth (OECD, 2015).

Inclusive institutions ensure that markets are functional and open to competition, and allow for broad citizen participation, pluralism, and an effective system of checks and balances, leading to better access to services and opportunity. Cross-country evidence shows that inclusive governance can improve development outcomes, such as better literacy and health, or lower infant mortality (e.g. Halperin, Siegle and Weinstein, 2010; Evans and Ferguson, 2013). Rajkumar and Swaroop (2002) also find that, for example, corruption disproportionately denies the poor access to education and health services.

Effective and efficient public governance is an essential lever for high-impact public spending, which in turn enhances the potential of economic policies to improve inclusive-growth outcomes. For example, stakeholder engagement and consultation can help identify needs and preferences, better targeting government programmes and increasing efficiency. Public governance also affects the quality and efficiency of public investment. In this respect, strengthening inclusive institutions has great potential to enhance citizen participation, provide better public services, reduce transaction costs, and – ultimately – reduce inequalities while promoting economic growth.

Last but not least, governance matters for well-being (OECD, 2015). People are more satisfied with their lives in countries that have more transparent and accountable governance. Actual changes in governance quality (understood as the way in which policies and services are designed and delivered) lead to significant changes in quality of life. Changes in average life evaluations in 157 countries over the period 2005-12 can be explained just as much by changes in governance quality as by changes in GDP, even though some of the well-being benefits of better governance are delivered through increases in economic efficiency and hence GDP per capita. The well-being payoff of improved governance in that period can be compared to a 40% increase in per capita incomes (OECD, 2015).

Addressing public governance bottlenecks for the creation of a more sustainable and inclusive Paraguay

The government of Paraguay clearly recognises that its public administration needs to be reformed in order to achieve the country’s strategic development goals. It is to the credit of the current administration that it has engaged in a comprehensive review exercise with the OECD. In the Background Report (Government of Paraguay, 2017) that was submitted to the OECD in preparation for this Public Governance Review, the government indicated that its request for a thorough OECD Review was based on the following considerations:

Paraguay wishes to develop a consensual whole-of-government vision for the country’s public sector which is shared by all ministries, secretariats, public companies and decentralised agencies.

So far, no comprehensive public administration reform programme with a holistic approach has been pursued in Paraguay. In the past, reforms have been implemented according to emerging needs and/or in the light of international commitments assumed by the government. Often reforms were limited to the creation of bodies and agencies that could only address specific issues.

An important number of institutions (Secretariats, etc.) have been created since 1989 (actually most of the current institutions were created in the period between 1989 and 1993 and most of the groundwork legislation derived from the new constitution was approved within the 1989-1992 parliamentary period) most of which, until today, are relatively weak and cannot effectively exercise the role that the Constitution gives them (see chapter 2). The government wishes to strengthen these institutions so that they can fulfil their mandates more effectively.

Coordination of public policies between the branches of the state, within the Executive Branch, and with sub-national governments needs to be improved. The government finds it necessary to find agile, efficient and politically viable mechanisms for public policy co-ordination.

Paraguay has been characterised throughout its history as highly centralised, both politically and administratively, a characteristic that was intensified during the 34 years of Alfredo Stroessner's dictatorship.

There is resistance by some institutions and political actors to move from client list human resources management towards a modern, merit-based, transparent recruitment system for public servants. The government wishes to implement such a system throughout the whole public administration and at all levels of government.

Creating a stronger and more resilient institutional framework at all the levels of the State in order for institutions responsible for implementing laws and regulations, as well as for implementing development policies, is a priority of the government. It wishes to prevent policy capture and make sure that institutions are not “overrun” or captured by stakeholders that have political and economic interests.

Paraguay further aims to create an administration that is focused on peoples’ needs. The government acknowledged that in many sectors public servants still believe that they are the owners of public resources.

Taking into account these considerations, this OECD Public Governance Review aims to provide a roadmap for public governance reform in order for the government of Paraguay to achieve its strategic objectives. The PGR identifies key aspects in different areas of public governance that the government of Paraguay has deemed important to achieve its vision and that need to be addressed in order to create a public administration that can deliver on inclusive growth for all.

Chapter 2 discusses ways to enhance whole-of-government co-ordination efforts led by Paraguay’s centre of government in order for the CoG to articulate integrated multi-dimensional policy responses to the increasing levels of complexity of the challenges the country and its people are facing.

Chapter 3 discusses the need for a better connection between the budgeting process and different policy agendas, including the National Development Plan 2030, in order for the country to adopt and implement reforms for inclusive growth that are fully funded.

Chapter 4 highlights the need for a greater focus on a coherent, strategic approach to regional development and better multi-level governance to ensure that policies are tailored to the circumstances and conditions in different regions of Paraguay and can actually meet citizens’ needs properly across territories characterised by acute regional disparities.

Chapter 5 discusses Paraguay’s need to move towards more modern human resources management practices in order for the public service to be able to address the specificities of the country’s development challenges.

Chapter 6 focuses on the need for a more open, transparent, accountable and participatory government in order to ensure that policies adequately reflect the population’s needs.

Taken together, the five technical chapters of this OECD Public Governance Review provide a coherent, holistic picture of the governance reform needs of the Paraguayan public sector. This integrated narrative is presented in the Assessment and Recommendations section at the front of this Review.

The Chapter findings are derived from the responses provided by the Government to a detailed OECD survey which collectively form the PGR’s Background Report, the results of two Peer-driven OECD fact-finding missions to Paraguay in July and September 2017 (including visits to various municipalities in the North and East of the country – see chapter 4), further desk research by the OECD team, and a “sounding-board” mission in February 2018 at the end of the Review process during which the draft advice was discussed with all key stakeholders involved in this Review and finalised accordingly.

The Chapters include tailor-made policy recommendations the implementation of which could contribute to Paraguay achieving its reform objectives while at the same time bringing the country closer to OECD standards. Whenever relevant, the chapters make reference to existing good practices from OECD member and partner countries, several of which having been provided by the Country Peers who contributed to this Review.

References

Abente Brun, D. (2011), “Después de la Dictadura”, Historia del Paraguay, ed.Ignacio Telesca (After the Dictatorship, History of Paraguay), editorial Taurus. pp 375-390, Asunción.

Acemoglu, D. and J. Robinson (2012), Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power,Prosperity and Poverty, Crown, New York.

Coase, R.H. (1960), “The problem of social cost”, Journal of Law and Economics,Vol. III, October, pp. 1-44, www.econ.ucsb.edu/~tedb/Courses/UCSBpf/readings/coase.pdf.

DGEEC (2017) “DGEEC presentó nueva serie de pobreza y pobreza extrema” [DGEEC presents new series for poverty and extreme poverty], website of the Dirección General de Estadística, Encuesta y Censos, Paraguay, available at www.dgeec.gov.py/news/DGEEC-PRESENTO-NUEVA-SERIE-DE-POBREZA-Y-POBREZA-EXTREMA.php.

European Union (2017), Paraguay, https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/countries/paraguay_en

Evans, W. and C. Ferguson (2013), “Governance, institutions, growth and poverty reduction: A literature review”, UK Department for International Development (DFID), London, http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/pdf/outputs/misc_gov/61221-DFID-LRGovernanceGrowthInstitutionsPovertyReduction-LiteratureReview.pdf.

Government of Paraguay (2017), Background Report prepared for the OECD Public Governance Review of Paraguay (internal document).

Government of Paraguay (2014), Plan Nacional de Desarrollo Paraguay 2030, www.stp.gov.py/pnd/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/pnd2030.pdf

Halperin, M., J. Siegle and M. Weinstein (2010), The Democracy Advantage: How Democracies Promote Prosperity and Peace, Revised Edition, Routledge, Abingdon, United Kingdom

Hanratty et al. (1990), Paraguay: a country study, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gdc/cntrystd.py

Latinobarometro (2015), “Datos 2015”, Banco de Datos (dataset), www.latinobarometro.org.

Marine Corps Intelligence Activity (n.d.), Paraguay Country Handbook https://info.publicintelligence.net/MCIA-ParaguayHandbook.pdf

North, D.C. (1991), “Institutions”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 5/1, Winter, pp. 97-112, www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.5.1.97.

Nickson, A. (2011), “El Regimen de Stroessner (1954-1989)” (The Stroessner regime (1954-1989), History of Paraguay), Historial del Paraguay, editorial Taurus

OECD (2018), OECD Development Pathways: Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay, OECD Publishing Paris, forthcoming. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/23087358

OECD (2017), Government at a Glance Latin America and the Caribbean 2017 – Country Fact Sheet Paraguay, www.oecd.org/gov/lac-paraguay.pdf

OECD (2016), OECD Public Governance Reviews: Peru: Integrated Governance for Inclusive Growth, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264265172-en

OECD (2015b), “Policy shaping and policy making: The governance of inclusive growth”, GOV/PGC(2015)20, OECD, Paris.

Rajkumar, S.A. and V. Swaroop (2002), “Public spending and outcomes: Does governance matter?”, Policy Research Working Papers, No. 2 840, World Bank, Washington, DC, http://dx.doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-2840.

Rodrik, D., A. Subramanian and F. Trebbi (2004), “Institutions rule: The primacy of institutions over geography and integration in economic development”, Journal of Economic Growth, Vol. 9/2, pp. 131-165, http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:JOEG.0000031 425.72248.85.

UNDP (2016), Human Development Report 2016, Human Development for Everyone -Briefing note for countries on the 2016 Human Development Report - Paraguay http://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/PRY.pdf