This section will examine the promotion of competition in the Dominican Republic by Pro‑Competencia, as well as its institutional co-operation with national sector regulators and competition authorities in other jurisdictions.

Peer Reviews of Competition Law and Policy: Dominican Republic

3. Competition advocacy and institutional co-operation

Abstract

3.1. Competition advocacy

A strong competition authority and a comprehensive competition law is not sufficient for allowing the economy and consumers to reap the benefits of a competitive environment. Indeed, in addition to effective competition enforcement, a competition culture must be established, not only among businesses, but also among courts, politicians, and government authorities, such as sector regulators. In other words, to work properly competition needs support from the policy environment and adequate framework conditions (OECD, 2013[1]).

Promoting competition is particularly relevant in developing countries, where competition law and policy are usually incipient and public policies and regulations are subject to major reviews. In this context, the role of competition authorities is of paramount importance to ensure that the review of regulations take into account competition principles.

Competition advocacy is a powerful tool to build competition culture. Pro-Competencia’s advocacy powers include promoting the adoption of regulations and state support measures that do not unduly restrict competition. In addition, Pro-Competencia can promote competition by raising awareness among other government entities, economic agents and the Dominican population about the importance of free competition.1

Pro-Competencia has multiple tools to implement its competition advocacy powers. For instance, it can conduct market studies; issue non-binding recommendation reports and non-binding reasoned opinions; prepare guidelines; and carry out training and outreach activities. As described in Section 1.4.1, the Competition Advocacy and Promotion Unit is in charge of preparing non-binding opinions and reports, organising outreach events and preparing guidelines, while the Economic and Market Studies Unit is responsible for carrying out market studies.

Although Pro-Competencia has adopted several advocacy initiatives between 2017 and 2022, a lack of competition culture is still perceived in the country including business.

3.1.1. Reports and opinions

Pro-Competencia can issue public non-binding recommendation reports in relation to:

a) Legal acts (laws, regulations, orders, standards, decisions and other legal instruments) that distort competition.2

b) State measures granting subsidies, aid or incentives to public and private companies that may create barriers to entry or confer unfair competitive advantages.3

c) Burdensome administrative procedures that hinder competition among companies and their right of establishment.4

Furthermore, Pro-Competencia can adopt public non-binding reasoned opinions in relation to acts adopted by sector regulators aimed at regulating markets or adopting infringement decisions in competition matters.5

Pro-Competencia’s advocacy actions may be triggered ex officio, by a complaint or by the obligation of the sector regulators to notify the competition authority of new regulations or sanctioning decisions. Pro-Competencia monitors on a regular basis the activities of the government and the Parliament. For example, Pro-Competencia has screened the development of new draft laws, regulations, administrative procedures and state support measures and examines their potential effects on competition by applying the Competition Assessment Checklist of the OECD Competition Assessment Toolkit (OECD, 2019[2]).

During the examination and assessment of a legal act, a state support measure or an administrative procedure, Pro-Competencia can request the necessary information to government entities. According to Article 13 of the Implementing Regulation, these entities are required to submit the information within 30 working days from the reception of the request. However, there are no sanctions in case of refusal to reply or in case of a late reply.

Recommendations of advocacy reports or opinions are non-binding. However, if the recipient authority of recommendations related to state support measures or legal acts decide not to follow them, it must indicate to Pro-Competencia in writing within 30 working days which recommendations it will not comply with and the reasons for not doing so.6 The same applies to opinions issued to sector regulators in relation to their competition enforcement actions,7, although this is not aways happening in practice. In addition, the sector regulators with competition enforcement powers do not always consult Pro‑Competencia, despite the requirement provided for in Article 20 of the Competition Act.

Since 2017, Pro-Competencia has issued 39 advocacy reports and opinions regarding different sectors (e.g. telecommunications, inland transport, food and beverages, health), as well as on other topics, such as public procurement and simplification of administrative procedures. The definition of priority areas and the follow-up of the implementation of these advocacy initiatives do not seem to be made in a consistent manner, which would benefit the overall advocacy efforts developed by Pro-Competencia.

3.1.2. Market studies

In Dominican Republic, market studies focus on the competition conditions of specific markets and propose measures to improve competition in those markets (while Pro-Competencia’s reports and opinions usually target more specific rules and regulations that may have anti-competitive effects).

Items “d” and f” of Article 33 of the Competition Act grants the Pro-Competencia’s Executive Directorate the power to carry out market studies to analyse the level and conditions of competition in the Dominican Republic. The Board of Directors decides together with the Executive Directorate which markets and sectors will be subject to a market study based on 10 criteria defined by the Economic and Market Studies Unit, including the classification of the market according to the Observatory of Market Conditions (see below), a preliminary evaluation of the market and the availability of information, the relevance of the selected market, the existence of barriers to entry and the impact on consumers. Market studies are developed by the Economic and Market Studies Unit.

Market studies must contain the characteristics of the markets, including the main variables determining the demand and supply, substitutes of the goods or services, main undertakings present in the supply chain and the conditions of competition, while preserving confidentiality issues and avoiding specific individualisation of market players and conducts. In addition, market studies should assess public policies and sector-specific regulation, identify barriers to entry and present the conclusions and recommendations. Market studies are made public except if Pro-Competencia has received a complaint or opened an investigation against an undertaking present in the market in question.8

Neither the Competition Act nor the implementing Regulation provide for a process and methodology to carry out market studies.9 Nearly all competition authorities in OECD jurisdictions conduct some kind of market study, ranging from short and informal assessments to lengthy and formal analysis involving multiple rounds of stakeholders’ input and empirical analysis. Most of them have defined a methodology and a process for carrying out market studies (OECD, 2018[3]). The OECD and the International Competition Network (ICN) have published a handbook and good practice guide on the collection and assessment of market research information (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1. The OECD-ICN Market Studies Good Practice Handbook

The OECD published a guide to market research for competition authorities in 2018. This guide should be read in conjunction with the Market Studies Good Practice Handbook prepared by the International Competition Network, which is based on the experience of the network's member authorities.

The OECD guide is structured around the main phases of market studies: the choice of market or sector, methodologies for conducting studies, including stakeholder participation, surveys, information collection and analysis, identification of market structures and their characteristics, and remedies and initiatives that could be launched as a result of such studies.

The International Competition Network Handbook provides additional detail and a wide range of useful guidance, including for:

Planning the information gathering process, including internal consultations, determining whether the authorities already have the necessary information or can obtain it from public sources, and considering the burden on stakeholders in responding to data requests.

Organising the research, taking into account financial constraints and considering alternatives if initial efforts prove unsuccessful. The handbook recognises that competition authorities may find it difficult to identify the most promising avenues of research at the outset of the study, and may therefore need to redirect their efforts.

Choosing methods of information gathering, noting that empirical evidence may carry more weight than more qualitative evidence. The manual highlights the advantages and disadvantages of certain collection methods, such as targeting specific groups and surveys.

Analysing the information, for example, whether it meets the needs of the authorities and confirms the original assumptions. Some authorities find it useful to publish initial findings and/or possible conclusions, as this helps them to validate their findings, bring out new information, and identify possible gaps in the analysis.

Ensuring the confidentiality of information through information handling procedures.

Source: Reproduced from OECD (OECD, 2022[4]), OECD Peer Reviews of Competition Law and Policy: Tunisia, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/oecd-peer-reviews-of-competition-law-and-policy-tunisia-2022.pdf.

Since 2016, Pro-Competencia has carried out 8 market studies in the following sectors and markets: (i) medicine Market (Pro-Competencia, 2016[5]); (ii) beer Market (Pro-Competencia, 2016[6]); (iii) insurance market (Pro-Competencia, 2016[7]); (iv) bread Market (Pro-Competencia, 2017[8]); (v) land transport market (Pro-Competencia, 2017[9]); (vi) management of pension funds market (Pro-Competencia, 2020[10]); (vii) public procurement and contracting processes (Pro-Competencia, 2021[11]); (viii) state support measures (Pro-Competencia, 2022[12]). At least one of them has led to a formal investigation and sanction of anti-competitive infringement by Pro-Competencia (i.e. the beer market study).

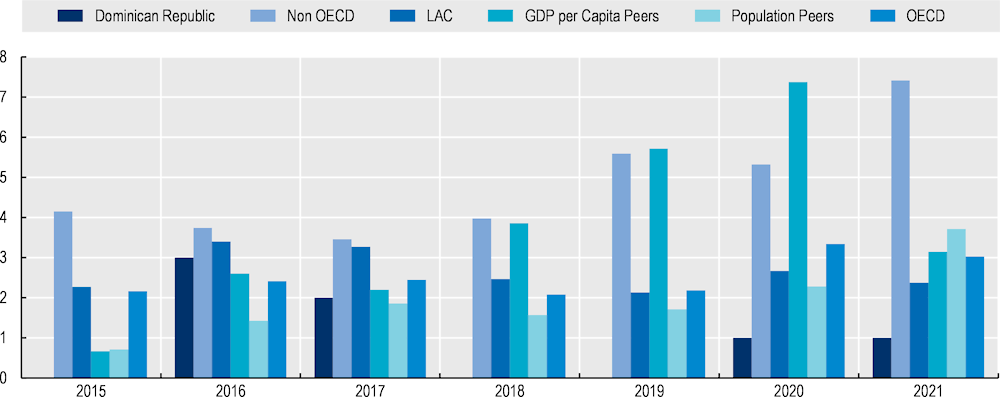

As shown in Figure 3.1 below, in 2016 the number of advocacy market studies undertaken by Pro‑competencia was above the OECD average and the average number of market studies in jurisdictions with a GDP per capita similar to the Dominican Republic. However, the number of market studies published by Pro-Competencia reduced between 2017 to 2021, being below the average in the OECD, Latin America and the Caribbean, non-OECD countries and GDP per capita peers.10 One reason for that may be the limited resources (both material and human) of Pro-Competencia and, thus, of the Economic and Market Studies Unit (see section 1.4.4).

Figure 3.1. Comparison of Number Advocacy Market Studies

Note: OECD (2023[13]) CompStats database. https://www.oecd.org/competition/oecd-competition-trends.htm.

Box 3.2 provides an example of a market study where, in the absence of a merger control system, Pro-Competencia used its advocacy powers to analyse the competition effects of a merger in the Dominican Republic.

Box 3.2. Market Study in the beer market of the Dominican Republic, 2016

In 2016, Pro-Competencia carried out a market study to analyse the potential effects on competition of the 2012 merger between CND and AmBev, the two major breweries in the country. The transaction involved the acquisition of 51% of CND’s shares by AmBev, creating a sole beverage company in the Caribbean region.

Pro-Competencia concluded that the transaction eliminated the maverick (AmBev), which since 2004 had increased the degree of competition in the Dominican beer market by lowering prices and offering a broader diversity of beer brands.

The market study also described the methodology required to define the relevant market in a competition analysis, applying the hypothetical monopolist test. Econometric methods were applied to quantify the price elasticity of demand for beer.

The market study concluded that there was a high degree of concentration in the beer market and that this had been exacerbated by the merger. It shows that, post-merger, beer prices increased, negatively affecting consumer welfare. In addition, it indicates that the horizontal integration has allowed the merged entity to increase its profit margins and its return on equity and total assets.

The market study also identified potential anti-competitive practices in the beer and the rum markets, such as exclusive dealing and tying. Part of these practices were investigated and sanctioned by Pro‑Competencia in 2019 (see Box 2.3).

The market study recommended measures similar to those adopted by other competition authorities in the context of merger control procedures, including the transfer of brands; divestiture of production plants or other assets; obligation for the merged entity to grant access to its distribution network during a period of time; or prohibition of tying practices.

Source: Pro-Competencia (Pro-Competencia, 2020[14]), Study of the Competition Conditions in the Beer Market of the Dominican Republic, https://procompetencia.gob.do/wpfd_file/estudios-de-condiciones-de-competencia-en-el-mercado-de-cervezas-de-la-republica-dominicana/.

Observatory of Market Conditions

Pro-Competencia, through the Economic and Market Studies Unit, has developed the Observatory of Market Conditions (Observatorio de condiciones de Mercado), a tool to screen market conditions in a broad range of markets of the Dominican economy (Pro-Competencia, 2022[15]). Thanks to this tool, Pro-Competencia can better identify markets that deserve a close monitoring and, eventually, a thorough market study.

The Observatory monitors the market conditions of different sectors of the economy on the basis of 6 criteria (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1. Criteria for the analysis of market conditions

|

Criteria |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

Criterion 1: Prices of the family market basket |

Products in the family market basket that have registered atypical inflation during the period in comparison to historical trends. |

|

Criterion 2: Economic growth |

Economic sectors that have a high impact on the growth of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the country. |

|

Criterion 3: Characteristics and dynamics of the market |

Market characteristics that facilitate anti-competitive behaviour, such as: high concentration and no information available on the functioning of markets generating uncertainty as to the existence of competitive pressure. |

|

Criterion 4: Essential intermediate inputs |

Economic activities that function as intermediate goods or services that are considered essential to be active in other markets. |

|

Criterion 5: Regulations of interest |

Regulatory provisions that could have an impact on conditions of competition in the markets. |

|

Criterion 6: Societal concerns |

Concerns or opinions that have been expressed by society regarding the conditions of market competition. |

Source: OECD based on Pro-Competencia (Pro-Competencia, 2022[15]), Observatorio de Condiciones de Mercado, https://procompetencia.gob.do/observatorio-de-condiciones-de-mercado/.

This screening allows Pro-Competencia to identify competition risks and define priority markets either because of their structure or the behaviour of economic agents therein. Markets are then classified by colours:

a) Red includes markets that meet two or more of the evaluated criteria. It also includes markets where Pro-Competencia has opened an investigation or is about to adopt a competition infringement decision.

b) Yellow includes markets that meet one of the evaluated criteria (except for criterion 3) that also appeared in the previous screening process.

c) Green includes markets that meet one of the evaluated criteria that did not appear in the previous screening process and/or criterion 3.

This classification allows Pro-Competencia to focus its resources on monitoring markets that are more prone to competition restrictions, namely markets that have been categorised as red or orange by the Observatory.

Twice a year, Pro-Competencia publishes a report with the results of the Observatory. The report of July-December 2022 identified the following red flag markets: bread, water bread, malt, flour biscuits, sweet biscuits, health insurance services, brewing of beer, malted and malt beverage, manufacture of iron and steel products (Pro-Competencia, 2022[15]).

3.1.3. Guidelines

Issuing competition law guidelines is a common practice worldwide, aiming to spell out in advance and in a transparent fashion the competition authority’s enforcement policy and approach as regards different provisions of its competition law, including both substantive and procedural aspects. Competition law guidelines usually seeks to explain the law in simpler language; indicate how a competition authority is intending to interpret the legislative provisions; refer to any relevant case law or prior decisions, which assist the competition authority with its interpretation; and provide case or hypothetical examples.

Guidelines are a powerful tool to create competition culture, particularly for developing jurisdictions where the competition culture is still emerging and where competition authorities are often young, inexperienced and faced with limited resources. Guidelines can help raise businesses and the public awareness with regard to competition law, which is likely to fosters competition compliance and competition law enforcement. Competition law guidelines may also contribute to increased legal certainty and transparency for businesses, the state, and the society. Additionally, although guidelines are not binding, they can provide guidance criteria and help establish a uniform approach in the application of competition law by the competition authority. Finally, they can help courts when analysing competition law cases, especially in jurisdictions where competition law is new.

So far, Pro-Competencia has adopted 4 public guidelines on substantive matters, while no guidelines on procedural issues have been developed. The substantive guidelines are:

a) Guide for the prevention and detection of collusion in public procurement: this document contains guidelines on how to prevent and detect collusive agreements in public procurement. It is a useful tool for public servants and entities involved in public procurement. It gives indications on how to design public procurement to prevent collusive practices and how to detect the most common collusive patterns (Pro-Competencia, 2020[10]).

b) Basic guide to free competition for business and trade associations: this guide explains the basic principles of competition enforcement in the Dominican Republic. It also provides examples of activities or initiatives of trade associations that could constitute anti-competitive conduct and gives indications on how trade associations can contribute to the prevention and fight against competition infringements (Pro-Competencia, 2020[14]).

c) General guidelines on competition compliance programs: this document explains the benefits and importance of having an effective competition compliance program in place. It also describes the minimum content that these programs should contain and gives a detailed explanation on how to conduct a competition risk assessment (Pro-Competencia, 2021[16]).

d) Basic guide to the Competition Act: this guide is aimed at providing an overview into the competition enforcement and advocacy powers of Pro-Competencia. It explains the prohibited practices, the enforcement procedures, the advocacy initiatives and the different tools available for individuals and companies willing to lodge a complaint or contact the competition authority for advocacy purposes (Pro-Competencia, 2020[14]).

In addition, at the time of writing, Pro-Competencia was updating a number of guidelines that it developed in 2015 and a frequent publication of these guidelines in Pro-Competencia’s website would benefit competition advocacy and overall awareness. The topics covered include:

a) The relevant market and determination of a dominant position.

b) Concerted practices and anti-competitive agreements.

c) Abuse of a dominant position.

d) Unfair competition.

e) Reviewing State legal acts.

f) Treatment of State support measures.

g) Studies and reports on competition conditions in the markets.

h) Criteria for setting penalties.

i) Guidelines on the Competition Act for the National Congress and Public Administration entities.

3.1.4. Capacity building and outreach activities

Pro-Competencia has organised capacity-building workshops in co-operation with the United States Authority for International Development (USAID) and the Commercial Law Development Program (CLDP), providing training opportunities to officials from the competition authority and other government bodies. These workshops focused mainly on fighting bid rigging, and the General Direction for Public Procurement (Dirección General de Compras Públicas, DGCP) participated in most of them. These included:

a) Workshop on cartels for Pro-Competencia and DGCP staff, held during 26-28 April 2022 and 4 May 2022 by personnel from the US Department of Justice.

b) Workshop on cartel investigation techniques for Pro-Competencia and DGCP staff, held on 4 August 2022 by the staff of the CLDP and the US Department of Justice.

c) Workshops on Detecting and Deterring Collusion in Public Procurement for staff working in procurement units in different government authorities held on 10 and 11 august 2022 by personnel from the CLDP and the U.S. Department of Justice.

Pro-Competencia has also been actively participating in the OECD Regional Centre for Competition in Latin America,11 located in Lima, which has provided several capacity-building activities in the last years that benefited 15 civil servants from Dominican Republic in 2022, 6 in 2021 and 10 in 2020.

In addition, Pro-Competencia has developed outreach events on an ad hoc basis, without an underlying strategy. These events focus on promoting a culture of competition to general public, such as universities, micro, small and medium-sized companies, trade associations and journalists. Table 3.2 below summarises these outreach events held by Pro-Competencia during 2018-2022. For instance, 1 018 people participated in the 22 events organised in 2022.

Table 3.2. Pro-Competencia’s outreach initiatives 2018-2021

|

Year |

Total number of outreach events organised by Pro-Competencia |

|---|---|

|

2018 |

18 |

|

2019 |

10 |

|

2020 |

9 |

|

2021 |

18 |

|

2022 |

22 |

Source: Pro-Competencia.

Pro-Competencia is also very active in the media and social networks.12 For instance, it organises regular competition-awareness campaigns through these means, which included the campaigns “ABC competition: Sharing concepts to better understand Law 42-08”, “Values that Compete: Sharing civil values and those of our institution to encourage fair competition” and “Free competition benefits us all: Campaign to promote the benefits of competition in society".

In addition, Pro-Competencia is carrying out an essay contest for undergraduate students, aiming at promoting competition among universities (Pro-Competencia, 2023[17]). It has also recently launched an initiative called “Competition Dialogues”, providing a forum for discussion on competition law issues (ProCompetencia, 2023[18]), and will publish the first Dominican Yearbook on Free and Fair Competition in October 2023.

Communication can be an effective tool to build authorities’ reputation, helping to establish themselves as credible and trustworthy institutions, committed to achieving their objectives. Moreover, it educates businesses and consumers about competition law and its implications. Many businesses may not be aware of competition laws and may not fully understands their requirements. Similarly, consumers may not be able to identify anti-competitive practices. Through effective communication, authorities can help businesses and consumers understand the importance of competition and the risks of anti-competitive practices (OECD, 2023[19]).

A starting point to foster competition culture is to identify the level of awareness of competition law among business, private practitioners, public servants and citizens. This may enable the competition authority to better tailor advocacy messages and their target audience. For instance, in 2017 COFECE hired a consultancy firm to map how competition law and COFECE’s actions were perceived in Mexico (McKinsey&Company, 2017[20]). This helped COFECE to adapt the language used in advocacy materials to better convey its messages to non-specialised audiences and explain in simple terms what COFECE does and how it directly benefits Mexican consumers (Mexico, 2023[21]).

3.2. Domestic co-operation

Pro-Competencia has developed co-operation channels with a number of authorities and government entities in the Dominican Republic. At national level, inter-institutional co-operation is governed by: (i) Article 138 of the Dominican Constitution, which establishes the principle of co-ordination among the entities of the Public Administration; (ii) Paragraph 4 of Article 12 of the Organic Law of Public Administration,13 which provides for the principle of co-operation and coherent approach among the state entities; and (iii) Articles 13, 14, 20, 40 and 69 of the Competition Act.

Most of the co-operation efforts of Pro-Competencia at national level have focused on building a dialogue with sector regulators with competition enforcement powers, although there have also been some initiatives with other entities.

3.2.1. Co-ordination with sector regulators with competition enforcement powers

As previously mentioned, in the Dominican Republic, some sector regulators are given exclusive jurisdiction to enforce competition law in their respective sectors. In particular, this is the case is in the telecommunications sector, the electricity sector, the financial and banking sector, the inland transport sector, as well as for intellectual property.

In any case, co-operation between competition authorities and sector regulators are necessary to guarantee consistency between their actions, reduce duplication and ensure a more efficient and better use of public resources (OECD, 2022[22]). The Competition Act recognises the relevance of domestic co-operation and empowers Pro-Competencia and the sector regulators to adopt co-ordination initiatives. Article 69 of the Competition Act establishes that Pro-Competencia should meet with different regulators to jointly design the competition regime that would govern the different sectors and activities up to 2019. Nevertheless, this multi-lateral effort never occurred.

The creation of working groups bringing together the competition authority and a number of regulators have proven effective in other jurisdictions, improving communication and facilitating discussions between the authorities to reach a shared understanding and approach. For instance, the UK Competition Network illustrates how working groups can help enhance co-operation between the competition authority and regulators, as described in Box 3.3 (OECD, 2022[22]).

Box 3.3. UK Competition Network

The UK Competition Network is a forum for co-operation between the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), the UK competition authority, and all sector regulators in the UK that have competition law powers within their sectors. The sector regulators that are members of the UK Competition Network are: the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), the Gas and Electricity Markets Authority (Ofgem), the Northern Ireland Authority for Utility Regulation (NIAUR), the Office of Communications (Ofcom), the Office of Rail and Road (ORR), the Payment Systems Regulator (PSR) and the Water Services Regulation Authority (Ofwat).

The UK Competition Network aims to facilitate co-operation and to consider more generally how best to promote competition and competitive outcomes for the benefit of consumers in the regulated sectors.

For example, the Network organises workshops on procedural or substantive issues; publishes information on cases in regulated sectors; and produces an annual report dealing with competition enforcement in regulated sectors and reporting on co-operation in the previous year, such as information sharing and case allocation.

Source: OECD (2022[22]), Interactions between competition authorities and sector regulators, https://www.oecd.org/competition/interactions-between-competition-authorities-and-sector-regulators.htm; UK Government (2017[23]), UK Competition Network, https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/uk-competition-network.

In addition to the multi-lateral fora, the Competition Act sets up a consultation and a referral mechanism between Pro-Competencia and the different regulators.14 The Competition Act requires that regulators request to Pro-Competencia an opinion regarding competition infringement decisions before its adoption. Regulators are also required to submit the draft of sector regulations to Pro-Competencia for an opinion if they involve competition law aspects. Likewise, if Pro-Competencia receives a complaint falling under the competition enforcement powers of another regulator, it must forward the complainant to the competent entity.

In order to formalise and regulate the consultation and referral procedures, Pro-Competencia and all regulators with competition enforcement powers (except for the financial and banking regulators) have signed the following bilateral co-operation agreements:15

Table 3.3. Co-operation agreements between Pro-Competencia and sector regulators with competition powers

|

Institution |

Date of signature |

|---|---|

|

National Office of Industrial Property (ONAPI) |

02 July 2014 |

|

National Energy Commission (CNE) |

01 February 2016 |

|

National Institute of Inland Transport (INTRANT) |

12 September 2017 |

|

Dominican Institute of Telecommunications (INDOTEL) |

06 July 2018 |

|

Superintendency of Electricity (SIE) |

14 August 2018 |

Source: OECD based on Pro-Competencia’s data.

At the time of writing, Pro-Competencia had referred a number of complaints to sector regulators, such as INTRANT, INDOTEL and SIE.16 All cases are still ongoing or have been dismissed.

Pro-Competencia has also adopted non-binding opinions in response to the public consultations of draft sector regulations, especially regarding the inland transport sector. However, Pro-Competencia had not been consulted by any sector regulator in relation to competition enforcement decisions, which may at least partially be explained by the limited competition enforcement activity of regulators.

Several stakeholders have expressed concerns over the few competition enforcement decisions adopted by sector regulators. For instance, the competition enforcement activity of INDOTEL in the last 25 years has been modest if compared to similar sector regulators with competition enforcement powers in the region. Between 2014 and 2018, for example, the Federal Institute of Telecommunications (Instituto Federal de Telecomunicaciones, IFT), the regulator and competition authority for the telecommunications and broadcasting sectors in Mexico has adopted four competition infringement decisions (OECD, 2020[24]). The Superintendency of Telecommunications (Superintendecia de Telecomunicaciones, SUTEL), the regulator and competition authority for the telecommunications sector in Costa Rica, opened 20 investigations against anti-competitive practices between 2014 and 2018. Since 2016, SUTEL has also carried out 14 market studies into competitive conditions in various telecommunications markets (OECD, 2020[25]).

Concerns about regulatory capture17 and how this could affect the competition enforcement activity of sector regulators has also been raised during the fact-finding mission. According to the OECD Multi-Dimensional Review of Dominican Republic, policy capture is presumably high in the Dominican Republic and one of the main barriers to inclusive and sustainable development (OECD, 2022[26]).

For many years, the perception that powerful groups dominate public policy making has been extremely high in the Dominican Republic, although there has been a significant decline more recently. In fact, the perception of concentration of power has been varying between 70% and 90% since 2008, above the LAC average. In 2020, however, there was a reduction in these numbers, as around 60% of Dominican believed the country was governed for and by powerful groups, which is below the LAC average (OECD, 2022[26]).

Sometimes, policy capture can take place through private sector influence from and within the institutional framework, not from outside (OECD, 2022[26]). For example, this can occur when there is presence of private sector representatives in governing bodies of public institutions. As described in Section 1.5.1, this is the case of INDOTEL, where representatives of the regulated agents (one representing the broadcasters and another representing the telecommunications providers) seat at the Board of Directors.

3.2.2. Co-ordination with Pro-Consumidor

The Competition Act defines unfair competition as any practice contrary to good faith and business ethics in economic activities that aims at illegitimately diverting consumer demand and can be sanctioned irrespective of whether the parties involved are competitors in the market.18 The non-exhaustive list of unfair competition practices include acts of undue comparison, acts of imitation, violation of business secrets, and acts of business defamation (e.g. thorough inexact or untrue information).19

Most complaints received by Pro-Competencia relate to unfair competition practices (around 50% of complaints since 2017), and internal estimations suggest that this topic covers around 80% of staff-time dedicated to investigations in Pro-Competencia. Since 2022, following a decision issued by the Board of Directors, Pro-Competencia has tried to limit the unfair competition cases to those that seriously disturb the public economic interest. Consequently, complaints affecting only private interests should be solved before civil or commercial courts.20

Indeed, Pro-Competencia’s efforts seem in line with other jurisdictions that also have competences over unfair competition practices, given that competition authorities should focus resources on investigations that can affect the public interest, particularly the structure of market (but not those that affect private interests only).

Box 3.4. Role of competition authorities on unfair competition practices

In Colombia, a private party injured by unfair-competition practices may file a suit in the general or specialised commercial law courts, seeking injunctive relief and damages. The Superintendence of Industry and Commerce (Superintendencia de Industria y Comercio, SIC), in charge of enforcing competition law in Colombia, will only examine unfair competition claims when they harm the public interest.

In Ecuador, the Competition Authority (Superintendencia de Competencia Económica, SCE) only deals with unfair competition cases if the infringer has market power. Unfair acts that affect only individual interests are heard by civil courts, in accordance with Article 26 of Organic Law of Regulation and Control of Market Power.

In Spain, the Competition Authority (Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia, CNMC) only investigates acts of unfair competition that affect the public interest when seriously disturbing the competitive structure or functioning of the market. Unfair-competition cases dealing with private interests are prosecuted and sanctioned by commercial judges.

Source: OECD-IDB (2021[27]), OECD-IDB Peer Reviews of Competition Law and Policy Ecuador, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/ecuador-oecd-idb-peer-reviews-of-competition-law-and-policy-2021.pdf; OECD (2016[28]), Colombia: Assessment of Competition Law and Policy, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/Colombia-assessment-competition-report-2016.pdf; Article 3 of the Spanish Competition Defence Law.

Unfair competition practices are not usually covered by competition law, being more often associated to consumer protection policies and better placed in this front. This may also explain why the line distinguishing the jurisdiction of the National Institute for the Protection of Consumer Rights (Instituto Nacional de Protección de los Derechos del Consumidor, Pro-Consumidor), the entity in charge of consumer protection in the Dominican Republic, and Pro-Competencia is unclear and sometimes overlap. There are no formal rules to avoid inconsistent decisions and divergent views between Pro-Consumidor and Pro-Competencia, but co-ordination efforts seem to be in place as seen by the signature of a co‑operation agreement on 9 May 2017, although developments are still pending, including co-ordinated strategies, as provided for in the agreement.

3.2.3. Co-operation with other entities

As mentioned above, co-operation initiatives between the competition authority and regulators with competition powers have been more developed in the Dominican Republic, but Pro-Competencia has also been engaging with other key state entities. In this context, ten bilateral co-operation agreements were signed between Pro-Competencia and the following institutions:

Table 3.4. Bilateral co-operation agreements

|

Institution |

Date of signature |

|---|---|

|

General Directorate of Customs (Dirección General de Aduanas, DGA) |

01 February 2017 |

|

Civil Aviation Board (Junta de Aviación Civil, JAC) |

23 March 2018 |

|

Superintendency of the Stock Market (Superintendencia de Mercado de Valores, SIMV) |

20 June 2018 |

|

Dominican Port Authority (Autoridad Portuaria Dominicana, APORDOM) |

28 June 2018 |

|

Superintendence of Pensions (Superintendencia de Pensiones, SIPEN) |

27 July 2018 |

|

General Directorate of Public Procurement (Dirección General de Compras Públicas, DGCP) |

09 December 2020 |

|

Constitutional Court (Tribunal Constitucional, TC) |

05 March 2022 |

|

National Institute of Civil Aviation (Instituto Nacional de Aviación Civil, IDAC) |

10 March 2022 |

|

National Copyright Office (Oficina Nacional de Derechos de Autor, ONDA) |

25 January 2023 |

Source: OECD based on Pro-Competencia’s data.

However, the existence of an agreement does not ensure that co-operation will occur in practice. In fact, the level of co-operation depends to a great extent on the interest and willingness of the entities to develop concrete collaborative initiatives.

A good example of co-operation is the inter-institutional agreement signed between Pro‑Competencia and the DGCP, the public procurement governing body in the Dominican Republic, to co-ordinate enforcement actions and exchange information. This agreement has set up a framework to (i) develop working groups composed of technical staff from both institutions to identify the respective roles in the prevention, detection, investigation and sanctioning of bid rigging, as well as to (ii) grant Pro‑Competencia access to the Integrated Consultation System of the DGCP, allowing a faster and more direct screening of suppliers and procurement patterns. In particular, the DGCP’s platform allows Pro‑Competencia to obtain information regarding public procurement processes since 2017, including suppliers and the bidding procedures in which they have participated, which may be useful to detect and sanction bid rigging in public procurement in the Dominican Republic.

3.3. International co-operation

The Competition Act states that Pro-Competencia, through the Board of Directors, may sign international co-operation agreements with foreign competition authorities, as well as promote international co-operation in order to perform its activities more effectively.21

At the time of writing, Pro-Competencia had signed international agreements on competition issues with the following competition authorities:

Table 3.5. International co-operation agreements

|

Competition authority/Jurisdiction |

Date of signature |

|---|---|

|

National Commission for the Defense of Competition (Comisión Nacional de Defensa de la Competencia, CNDC), Argentina |

3 February 2023 |

|

Commission for Defence and Promotion of Competition (Comisión para la Defensa y Protección del Consumidor, CDPC), Honduras |

September 2019 |

|

Federal Economic Competition Commission (Comisión Federal de Competencia Económica, COFECE), Mexico |

April 2016 |

|

Authority for the Protection of Consumers and Defense of Competition (Autoridad de Protección al Consumidor y Defensa de la Competencia, ACODECO) of Panama |

October 2015 |

|

Market Power Control Superintendence (Superintendencia de Control de Poder de Mercado, SCPM), Ecuador |

November 2014 |

|

National Competition Commission (Comisión Nacional de Competencia, CNC), Spain |

September 2012* |

Note: * At the time of writing, this agreement was being renegotiated with the Spanish National Commission on Markets and Competition (Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia, CNMC).

Source: OECD based on Pro-Competencia’s data.

These are first-generation co-operation agreements, focusing on the sharing of experiences and knowledge and on capacity-building activities. Thanks to these agreements, Pro-Competencia staff has participated in diverse exchange programmes, trainings, study visits, and internships in other countries. The agreements do not provide for deeper co-operation activities, such as sharing of confidential information, investigative assistance and joint enforcement actions with other competition authorities.

Finally, Pro-Competencia has been participating in international fora, such as the OECD Global Forum on Competition (GFC), which meets annually.22 Pro-Competencia is also a member of the International Competition Network (ICN). At the regional level, Pro-Competencia has also actively participated in the IDB/OECD Latin American and Caribbean Competition Forum (LACCF)23 and the workshops of the OECD Regional Centre for Competition in Latin America in Lima.

Main findings

The main findings on competition advocacy and institutional co-operation of competition law and policy in the Dominican Republic include:

Lack of overall competition culture in the Dominican Republic.

Insufficient levels of co-operation between Pro-Competencia and sector regulators in the application of competition law, in addition to concerns on possible conflicting interests and lack of competition expertise within certain regulatory entities with the powers to enforce competition law.

Pro-Competencia’s opinions on advocacy initiatives are non-binding. Although authorities need to justify if they decide not to follow Pro-Competencia’s recommendations, this does not aways happen in practice. In addition, the sector regulators with competition enforcement powers do not always consult Pro-Competencia despite the legal requirement.

The number of market studies conducted by Pro-Competencia is below the average for international and regional standards.

References

[33] Dominican Republic (2022), Subsidies, Competition and Trade - Contribution from the Dominican Republic,, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2022)55/en/pdf.

[29] IDB (2021), Dominican Republic, IDB Group Country Strategy 2021-2024.

[20] McKinsey&Company (2017), Estudio y análisis de la percepción sobre temas de competencia económica y la labor de la COFECE - Informe de Resultados - 2017, https://www.cofece.mx/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Estudio-labor-COFECE-17.pdf.

[21] Mexico (2023), Assessing and Communicating the Benefits of Competition Interventions – Note by Mexico, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WP2/WD(2023)9/en/pdf.

[19] OECD (2023), Competition and Innovation: A Theoretical Perspective, OECD Competition Policy Roundtable Background Note, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/competition-and-innovation-a-theoretical-perspective-2023.pdf.

[13] OECD (2023), OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index: Policy trends up to 2023, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/trade/topics/services-trade/.

[22] OECD (2022), Interactions between competition authorities and sector regulators: OECD Competition Policy Roundtable Background Note, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/competition/interactions-between-competition-authorities-and-sector-regulators.htm.

[26] OECD (2022), Multi-dimensional Review of the Dominican Republic: Towards Greater Well-being for All, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/23087358.

[4] OECD (2022), “OECD Peer Reviews of Competition Law and Policy: Tunisia”, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/oecd-peer-reviews-of-competition- (accessed on 22 August 2022).

[25] OECD (2020), Costa Rica: Assessment of Competition Law and Policy 2020, OECD Publishing,, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/costa-rica-assessment-of-competition-law-and-policy2020.pdf.

[24] OECD (2020), OECD Telecommunication and Broadcasting Review of Brazil 2020, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/30ab8568-en.

[2] OECD (2019), Executive Summary of the Roundtable on Competition issues in labour markets, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/M(2019)1/ANN2/FINAL/en/pdf.

[3] OECD (2018), Suspensory Effects of Merger Notifications and Gun Jumping, OECD Competition Policy Roundtable Background Note, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/suspensory-effects-of-merger-notifications-and-gun-jumping-2018.pdf.

[31] OECD (2017), Sustaining Iceland’s fisheries through tradeable quotas, OECD Environment Policy Paper No. 9.

[28] OECD (2016), Local Nexus and Jurisdictional thresholds in merger control, OECD Competition Policy Roundtable Background Note, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WP3(2016)4/REV1/en/pdf.

[1] OECD (2013), Competition Issues in Television and Broadcasting, OECD Competition Policy Roundtable Background Note, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/competition-television-broadcasting.htm.

[27] OECD-IDB (2021), OECD-IDB Peer Reviews of Competition Law and Policy Ecuador, OECD Publishing,, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/ecuador-oecd-idb-peer-reviews-of-competition-law-and-policy-2021.pdf.

[18] ProCompetencia (2023), ProCompetencia realiza el primer de varios encuentros de “Diálogos de Competencia”, https://procompetencia.gob.do/procompetencia-realiza-el-primer-de-varios-encuentros-de-dialogo-de-competencia/.

[17] Pro-Competencia (2023), Escribiendo por la competencia, https://procompetencia.gob.do/escribiendo-por-la-competencia/.

[12] Pro-Competencia (2022), El Impacto de Ayudas Estatales desde la Perspective de la Competencia: El caso de la ley 18-01 de Desarrikki Fronterizo, https://procompetencia.gob.do/wpfd_file/estudio-sobre-el-impacto-de-las-ayudas-estatales/.

[30] Pro-Competencia (2022), El Impacto de Ayudas Estatales desde la Perspective de la Competencia: El caso de la ley 18-01 de Desarrikki Fronterizo, https://procompetencia.gob.do/wpfd_file/estudio-sobre-el-impacto-de-las-ayudas-estatales.

[15] Pro-Competencia (2022), Observatorio de Condiciones de Mercado,, https://procompetencia.gob.do/observatorio-de-condiciones-de-mercado/.

[11] Pro-Competencia (2021), Estudio de condiciones de competencia en los procesos de compras y contrataciones públicas en la República Dominicana, https://procompetencia.gob.do/wpfd_file/estudio-de-condiciones-de-competencia-en-los-procesos-de-compras-y-contr.

[16] Pro-Competencia (2021), Plan de Cumplimiento, https://procompetencia.gob.do/?s=plan+de+cumplimiento.

[10] Pro-Competencia (2020), Estudio de Condiciones de Competencia en el Mercado de las Administradoras de Fondos de Pensiones (AFP) en la República Dominicana en el sistema de capitalización individual, https://procompetencia.gob.do/wpfd_file/estudio-de-condi.

[14] Pro-Competencia (2020), Estudios de Condiciones de Competencia en el Mercado de cervezas de la República Dominicana, https://procompetencia.gob.do/wpfd_file/estudios-de-condiciones-de-competencia-en-el-mercado-de-cervezas-de-la-republica-dominicana.

[32] Pro-Competencia (2017), Decision n. 038-2017, https://procompetencia.gob.do/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/de-038-17-que-declara-la-incompetencia-de-atribucion-td-altice.pdf.

[8] Pro-Competencia (2017), Estudios de Condiciones de Competencia en el Mercado del Pan de Agua y Sobao, https://procompetencia.gob.do/wpfd_file/estudios-de-condiciones-de-competencia-en-el-mercado-del-pan-de-agua-y-sobao.

[9] Pro-Competencia (2017), Estudios de Condiciones de Competencia en el Mercado Transporte de la República Dominicana, https://procompetencia.gob.do/wpfd_file/estudios-de-condiciones-de-competencia-en-el-mercado-transporte-de-la-republica-dominicana/.

[6] Pro-Competencia (2016), Estudios de Condiciones de Competencia en el Mercado de cervezas de la República Dominicana, https://procompetencia.gob.do/wpfd_file/estudios-de-condiciones-de-competencia-en-el-mercado-de-cervezas-de-la-republica-dominicana.

[5] Pro-Competencia (2016), Estudios de Condiciones de Competencia en el Mercado de Medicamentos, https://procompetencia.gob.do/wpfd_file/estudios-de-condiciones-de-competencia-en-el-mercado-de-medicamentos.

[7] Pro-Competencia (2016), Estudios de Condiciones de Competencia en el Mercado de Seguros, https://procompetencia.gob.do/wpfd_file/estudios-de-condiciones-de-competencia-en-el-mercado-de-seguros.

[23] UK Government (2017), UK Competition Network, https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/uk-competition-network.

Notes

← 1. Articles 13, 14, 15, 20 and 31, item “n” of the Competition Act.

← 2. Article 14 of the Competition Act and Article 12 of the Implementing Regulation.

← 3. Article 15 of the Competition Act and Article 12 of the Implementing Regulation.

← 4. Article 13 of the Competition Act and Article 11 of the Implementing Regulation.

← 5. Article 20 and item “m” of Article 31 of the Competition Act.

← 6. Article 13, item 2 of the Implementing Regulation.

← 7. Article 16, item 7 of the Implementing Regulation.

← 8. Paragraph 1 of Article 15 of the Implementing Regulation.

← 9. At the time of writing, the Economic and Market Studies Unit was developing a guidance on market studies, in line with international best practices.

← 10. Nevertheless, at the time of writing, Pro-Competencia was finalising a number of market studies, including in the vehicle market and the role of digital platforms, as well as in the following sectors: water bottles, cement, napkins, construction rod, vitamins, lubricants, sugar, garlic, oxygen and diapers.

← 11. The OECD Regional Centre for Competition in Latin America was created in November 2019 as a joint venture between the Peruvian Competition Authority (INDECOPI) and the OECD. The Centre aims to expand the OECD's work on competition in Latin America through capacity-building and specific training to competition officials from the region. For more information, see https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/oecd-regional-centre-for-competition-in-latin-america.htm.

← 12. See, for instance, https://www.instagram.com/pcompetenciard and https://www.youtube.com/@procompetenciard.

← 13. Ley Orgánica de la Administración Publica No. 247-12, https://mt.gob.do/transparencia/images/docs/marco_legal_de_transparencia/leyes/2018/Ley-247-12-Organica-Administracion-Publica2c-de-fecha-9-de-agosto-de-2012.pdf.

← 14. Article 20 of the Competition Act.

← 15. However, it should be noted that Pro-Competencia and the Superintendency of Banks have been strengthening their relationship, in order to foster competition in the financial and banking sector (IDB, 2021[29]).

← 16. For instance, on 5 December 2017, Pro-Competencia forwarded to INTRANT a complaint received from the Union of Drivers and Employees of Minibuses (Sindicato de Choferes y Empleados de Microbuses, SICHOEM), for alleged anti-competitive practices (Pro-Competencia, 2017[9]). On 26 October 2017, Pro-Competencia adopted a decision stating that it did not have the powers to investigate a complaint from TRILOGY DOMINICANA, S.A. against ALTICE HISPANIOLA, S.A. and TRICOM, S.A. for alleged unfair competition practices in the market for the provision of telecommunications services, and the case was forwarded to INDOTEL (Pro-Competencia, 2017[32]). On 21 September 2022, Pro-Competencia forwarded to SIE a complaint received from the Dominican Alliance against Corruption (Alianza Dominicana Contra la Corrupción, ADOCCO) regarding the alleged participation of an electricity company (Norther Electricity Distribution Company, EDENORTE) in a bid-rigging scheme (Pro-Competencia, 2022[15]).

← 17. Policy capture is “the process of consistently or repeatedly directing public policy decisions away from the public interest towards the interests of a specific interest group or person” (OECD, 2017[31]).

← 18. Article 10 of the Competition Act.

← 19. Article 11 of the Competition Act.

← 20. Decision No. 009-2022 from 15 November 2022 (Pro-Competencia, 2022[30]). This Decision has been contested by different stakeholders. The main argument is that Pro-Competencia is required by law to investigate all complaints that it receives (Article 36 of the Competition Act) and would not be empowered to adopt decisions limiting its enforcement obligations.

← 21. Items “s” and “t” of Article 31 of the Competition Act.

← 22. For instance, in 2022 Pro-Competencia has submitted a written contribution to the Roundtable on Subsidies, Competition and Trade (Dominican Republic, 2022[33]).

← 23. In 2012, Pro-Competencia hosted the 10th meeting of the LAACF.