This chapter summarises the economic analysis conducted to assess the viability of the deigned Clean Public Transport Programme. It begins with a general overview of clean technologies and fuels in the transport sector, as well as a specific review of the energy market in Kyrgyzstan. It then describes the economic aspects of purchasing and running buses, and finally assesses potential sources of government financing available for the programme.

Promoting Clean Urban Public Transportation and Green Investment in Kyrgyzstan

3. Economic analysis of the Clean Public Transport Programme

Abstract

A market analysis was undertaken to determine the feasibility of the Clean Public Transport (CPT) Programme and its potential focus and scope.

Globally, the transport sector relies almost entirely on oil with about 94% of transport fuels being petroleum products. According to prognoses, these will dominate in road transport until at least 2050 (although the exact fuel mix might vary), even in the most stringent mitigation scenario (Sims and Schaeffer, 2014[1]).

There is often a time lag between when new technologies first appear in OECD countries and when they reach developing countries, which import mostly second-hand vehicles. It may take five years or longer lag for new technologies to reach second-hand vehicle markets in large quantities.

As part of the CPT Programme proposal, a detailed analysis was done of the key parameters, as well as the advantages and disadvantages of the various fuel options available for the programme, e.g. compressed natural gas (CNG)/liquefied natural gas (LNG), liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), diesel, and electricity to power trolleybuses. This chapter summarises the main findings, while Annex A to this report, especially Table A.3, contains the detailed analysis.

Apart from cleaner technologies and fuels, this chapter also discusses domestic production and import of buses, bus (trolleybus, minibus) fares for urban transport, and the co-financing available for investment projects.

3.1. Overview of clean technologies and fuels in the bus transport sector

This section provides an overview of the three cleaner fossil fuel options available in Kyrgyzstan:

compressed natural gas (CNG)

liquefied petroleum gas (LPG)

diesel fuel (Euro 5) combined with Euro 6/VI engines.

The section also describes electricity as a power carrier, especially if sourced from cleaner fossil fuels (natural gas) or renewable energy (wind, solar, hydro power).

3.1.1. Compressed natural gas (CNG)

CNG can be used in traditional petrol (internal combustion engine) automobiles that have been modified or in vehicles specially manufactured for CNG use. Although vehicles can use natural gas as either liquid (i.e. LNG) or gas (i.e. CNG), most vehicles use the gaseous form. Besides fossil gas (CNG and LNG), methane vehicles can also be fuelled with biomethane or power-to-methane – a concept that converts electrical energy into chemical energy using water and carbon dioxide (also called power-to-gas).

CNG combustion produces fewer undesirable gases than other fuels and is safer in the event of a spill, because natural gas is lighter than air and disperses quickly when released. CNG vehicles have been introduced in a wide variety of commercial applications, from light-duty (<3.5t) to medium-duty (<7.5t) and even heavy-duty (>7.5t) vehicles.

The energy efficiency of driving on CNG is typically similar to gasoline or diesel, but produces up to 25% less tailpipe emissions (CO2/km) because of differences in fuel carbon intensity. Lifecycle greenhouse gas (GHG) analysis suggests lower net reductions for natural gas fuel systems, however, in the range of 10-15%. This is because methane emissions are largely associated with leakage – i.e. unburnt methane leaking into the atmosphere – from the production of natural gas and the filling of CNG vehicles (in smaller amounts basically throughout the whole supply chain, ranging from 0.2% to 10% with a mean of 2.2% and median 1.6%) (T&E, 2018[2]).

In cars, the GHG savings range from -7% to +6% compared to diesel. In heavy duty vehicles (HDVs), such as buses, the range is -2% to +5% compared to best-in-class diesel trucks and depending on the fuel and engine technology. Therefore, CNG vehicles perform similarly to petrol vehicles and only slightly better than diesel ones (T&E, 2018[2]).

On the other hand, CNG vehicles require larger fuel tanks than conventional petrol-powered vehicles and the cost of fuel storage tanks is a major barrier to rapid and widespread adoption of CNG as a fuel. Denser storage can be achieved by liquefaction of natural gas (LNG), which is successfully being used for long-haul HDVs and ships. The indicative average distance between LNG refuelling points for HDVs is 400 km (T&E, 2018[2]).

3.1.2. Liquefied petroleum gas (LPG)

Also known as propane-butane, LPG is a flammable mixture of hydrocarbon gases used as a fuel in heating appliances, cooking equipment and vehicles. In some countries, LPG has been used since the 1940s as an alternative to petrol for spark ignition engines.

LPG has a lower energy density than either petrol or fuel-oil, so the equivalent fuel consumption is higher by about 10%. Many governments (not including Kyrgyzstan) impose less tax on LPG than on petrol or fuel-oil, which helps offset the greater consumption of LPG.

However, as mentioned in Chapter 2, CO2 emissions from LPG-powered engines are higher than from CNG-powered ones. Therefore, the results of the OPTIC (Optimising Public Transport Investment Costs) Model do not include LPG buses. However, as LPG is already being used in Kyrgyzstan (mainly by private users, including public transport operators), the OPTIC Model can be used to include LPG buses should policy makers decide to evaluate this option in the future. For this reason, buses powered by LPG are given medium priority (see Section 5.1.2).

LPG burns more cleanly than petrol or fuel-oil – causing less wear on engines – and is especially free of the particulates present in the latter.

3.1.3. Diesel with Euro 6/VI engines

Diesel engines are one of the most common combustion engine choices for buses and other commercial vehicles, globally. For the time being, buses that run on diesel and biodiesel – brought to the market mainly by blending with conventional diesel – constitute by far the largest part of the bus fleet. The vast majority of the minibus fleet in Kyrgyzstan is composed of light and medium-duty commercial vehicles (see Section 6.2).

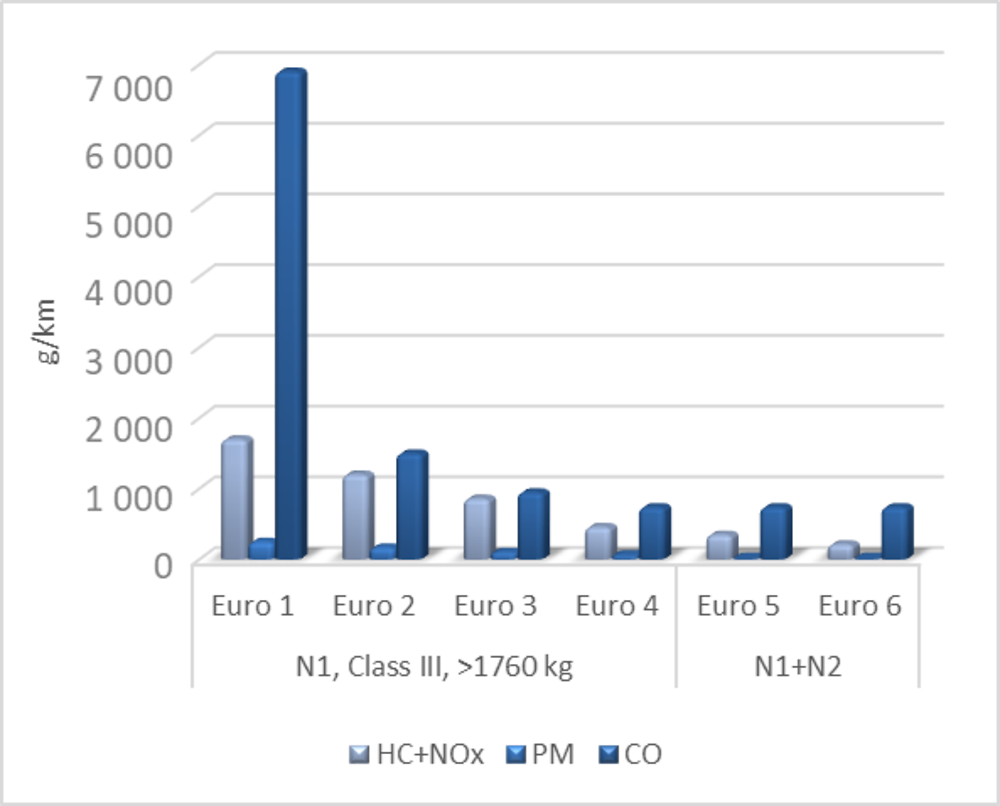

A standard diesel city bus emits fewer carbon emissions per passenger than cars, and lower emissions can be achieved by encouraging more passengers to shift to public transport (see Annex A). Since the 1990s, the Euro emission standards1 – which define the acceptable limits of nitrogen oxides (NOx), total hydrocarbons (THCs), non-methane hydrocarbons (NMHCs), carbon monoxide (CO) and particulate matter (PM) – have considerably reduced pollutant emissions of new vehicles sold in the European Union (EU) and the member states of the European Economic Area (EEA).

The biggest improvement in absolute terms has been achieved in reducing CO emissions (a Euro 6 vehicle emits 6.2 grams per kilometre less than a Euro 1 vehicle), whereas in relative terms the biggest improvement has been in PM emissions (a reduction of 98%) (Figure 3.1; see also Table A.1 and Table A.2 in Annex A to the report).

Figure 3.1. The impact of Euro standards on air pollution from light commercial diesel vehicles

Note: N1: commercial vehicle not exceeding 3.5t (light-duty truck); N2 : commercial vehicle exceeding 3.5t but not 12t (truck).

Source: DieselNet (www.dieselnet.com).

On the other hand, a shift from Euro V to Euro VI for heavy-duty vehicles will require considerable investments by manufacturers and public transport agencies, and a major outlay by bus manufacturers. Similar to light-duty vehicles shown in Figure 3.1, the shift to Euro VI engines will also have a significant environmental cost in the form of emissions of particulates from engine exhaust (in particular, as compared to Euro I-IV categories).

Using biofuels, such as ethanol (for internal-combustion-engines) and biodiesel (for spark-ignition-engines) blends with conventional fuels (i.e. petrol and diesel) creates large a potential for further CO2e emission reductions due to their lower fuel carbon intensity (CO2/megajoule). However, the GHG impact assessment is rather complex.

However, as mentioned in Section 4.5.1, the support for diesel-fuelled vehicles requires strengthening regulatory measures to assure lower negative environmental impact of these vehicles.

3.1.4. Electricity

Due to current limits in battery capacity and in driving range (generally 100-200 kilometres for a small to medium-sized car), electric vehicles are at present best suited to urban and suburban driving. An urban bus can have a range of 200 kilometres per charge, but the full battery electrification of heavy-duty vehicles and long-haul bus and coach fleets is not likely to be a realistic option in the near future. On the other hand, trolleybuses are, at this point, a more viable electrically-powered alternative for reducing emissions. In addition, trolleybuses can be rendered “autonomous” over portions of their route by storing electricity.

3.2. Main economic variables of Kyrgyzstan’s public transport

3.2.1. Energy market in the Kyrgyz Republic

The main suppliers of petroleum products to the Kyrgyz Republic are Kazakhstan, followed by the Russian Federation. Table 3.1 and Table 3.2 present the consumption, export and losses of petroleum products and natural gas respectively in the Kyrgyz Republic.

As can be seen in Table 3.1, the consumption of petrol increased considerably in 2011-16 (by 57%), while the increase in diesel consumption was only moderate (8.2%). This increased consumption needs to be covered by imports as the country’s crude oil production is rather minimal (1-2 000 barrels per day over 1992-20192).

Table 3.1. Consumption, export and losses of petroleum products, 2011-16

(conventional fuel equivalent*)

|

Items |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Motor-car petrol |

950 |

1 423 |

1 307 |

1 020 |

1 104 |

1 445 |

|

Consumed |

878 |

1 298 |

1 201 |

577 |

938 |

1379 |

|

Exported |

15 |

7 |

23 |

37 |

47 |

10 |

|

Losses |

1 |

19 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Surplus, end of year |

56 |

99 |

82 |

405 |

118 |

55 |

|

Diesel fuel |

715 |

908 |

1041 |

943 |

716 |

744 |

|

Consumed |

645 |

788 |

993 |

728 |

629 |

698 |

|

Exported |

24 |

9 |

13 |

3 |

1 |

- |

|

Losses |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Surplus, end of year |

45 |

109 |

35 |

212 |

86 |

46 |

|

Fuel oil |

243 |

169 |

127 |

322 |

505 |

267 |

|

Consumed |

183 |

110 |

71 |

285 |

387 |

201 |

|

Exported |

12 |

3 |

3 |

- |

- |

1 |

|

Losses |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Surplus, end of year |

48 |

56 |

52 |

37 |

118 |

65 |

Note: *Conventional fuel equivalent: thermal unit of fuel used to compare different types of fuel. Combustion of 1 kg of solid (liquid) conditional fuel (or 1 m3 gaseous) is equal to 29.3 megajoules (7 000 kcal).

Source: National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (http://stat.kg).

As Table 3.2 shows, in contrast to petrol and diesel, the consumption of natural gas slightly decreased over 2011-16 (by 0.02%). Similarly to crude oil, Kyrgyzstan does not produce significant amounts of natural gas – less than 30 million cubic metres per year since 1996 (whereas in 1992 it was 100 million cubic metres).3 For fossil fuels production, see Section 6.1.3.

Table 3.2. Consumption, export and losses of natural gas, 2011-16

(conventional fuel equivalent*)

|

Natural gas |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total |

383 |

490 |

355 |

328 |

318 |

331 |

|

Consumed |

331 |

394 |

311 |

293 |

298 |

325 |

|

Exported |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Losses |

52 |

96 |

44 |

35 |

20 |

6 |

|

Remainder, end of year |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Note: * Conventional fuel equivalent: thermal unit of fuel used to compare different types of fuel. Combustion of 1 kg of solid (liquid) conditional fuel (or 1 m3 gaseous) is equal to 29.3 megajoules (7 000 kcal).

Source: National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (http://stat.kg).

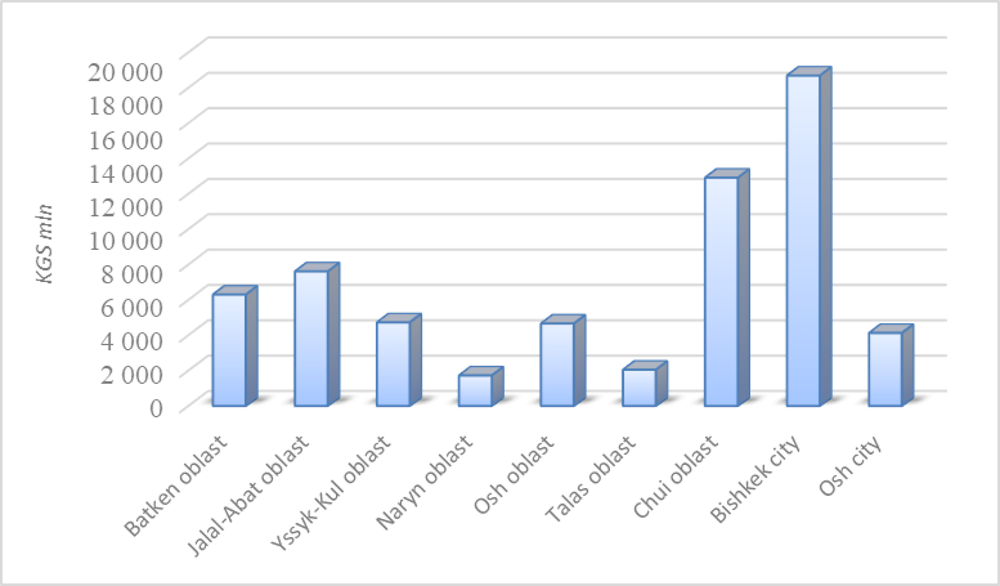

As can be seen in Figure 3.2, Bishkek city and the adjacent Chui oblast (region) were leaders in retail sales of automotive fuel in 2018. In fact, these two administrative units accounted for 50.3% of all sales in 2018.

Figure 3.2. Retail sales of automotive fuel, 2018* (by region)

Note: *Preliminary data.

Source: National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (http://stat.kg).

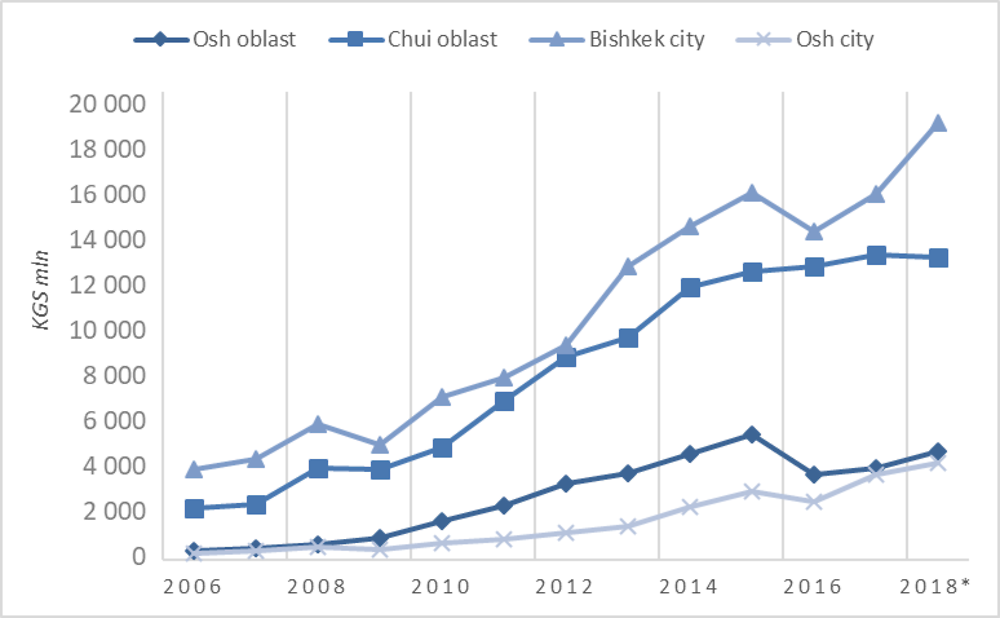

Figure 3.3 shows the growing gap in these sales between the capital and the adjacent Chui region, and between the other pilot city Osh and its region, since 2006 (though sales have been increasing in all four areas).

Figure 3.3. Retail sales of automotive fuel in pilot cities and neighbouring oblasts, 2006-18*

Note: *Preliminary data for 2018.

Source: National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (http://stat.kg).

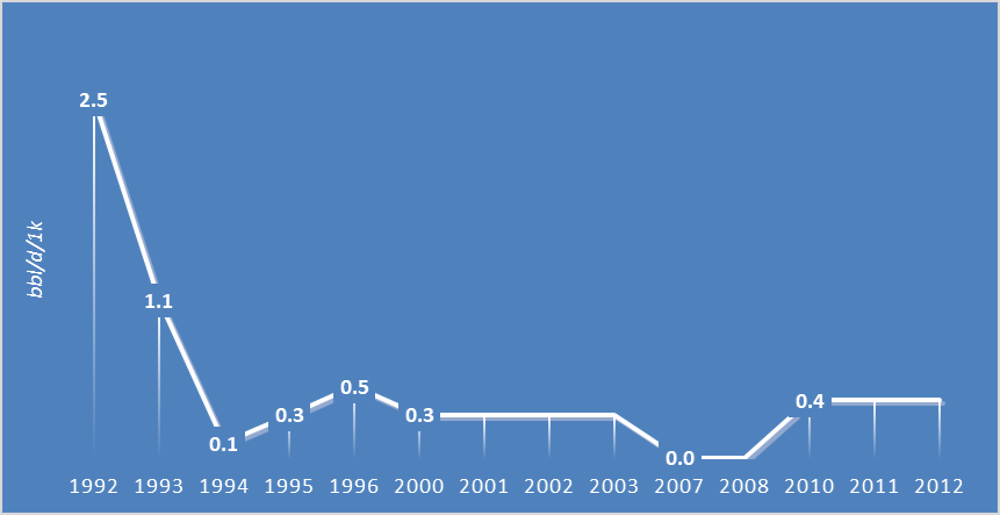

The national consumption of liquefied petroleum gas is far below 1 000 barrels per day, as seen in Figure 3.4. Consumption fell by 84% between 1992 and 2012.

Figure 3.4. Consumption of LPG in Kyrgyzstan, 1992-2012

3.2.2. Fuel prices

Table 3.3 presents the retail prices for various fuels in the Kyrgyz Republic.4 The State Agency for Regulation of the Fuel and Energy Complex (see Section 6.1.4) is responsible for granting energy production licences and setting energy tariffs.

Table 3.3. Retail prices for fuel in the Kyrgyz Republic, 2018*

|

Item |

KGS/litre |

USD/litre |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Petrol-92 |

44.12 |

0.64 |

|

|

Petrol-95 |

46.53 |

0.68 |

|

|

Diesel |

46.52 |

0.68 |

|

|

LPG |

25.50 |

0.37 |

Note: *As of December 2018. There are no data on CNG prices in transport.

Source: National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (http://stat.kg).

In Bishkek, the prices in Gazprom Neft stations were as follows in May 2018:5

Petrol-92: 43.50 KGS/l (USD 0.63)

Petrol-95: 46.50 KGS/l (USD 0.68)

Diesel, Euro 5: 45.50 KGS/l (USD 0.70)

LPG: 25.50 KGS/l (USD 0.37).

From January to December 2018, the price of fuel increased by about 11% and diesel by 24%. It is suggested that for planning purposes higher prices than the actual prices be assumed for LPG and CNG , as eventually prices will have to move towards world levels6 and excise and other taxes will be imposed in order to generate government revenues. Therefore, the following prices were used in the OPTIC Model (see Section 2.3.1):

Diesel, Euro 6: 48 KGS/l (USD 0.70)

Diesel, standard: 44.39 KGS/l (USD 0.65)

Electricity: 0.03 KGS/KWh (USD 0.0004)

LPG: 39.02 KGS/l (USD 0.57)7

CNG: 31.71 KGS/kg (USD 0.46).

The share of average per capita expenditure on natural gas – not only in the form of CNG but also for other (main) purposes, such as cooking and heating (apart from electricity generation) – reflects the actual cash expenditures of the population (Table 3.4). Here, we can see that the cities of Bishkek and Osh have the highest per capita expenditures on natural gas by a large margin, driving up the country’s average.

Table 3.4. Share of average per capita expenditure on natural gas in the Kyrgyz Republic, 2012-16

(%)

|

|

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kyrgyz Republic |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

|

Batken Region |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Jalal-Abad Region |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

|

Issyk kul Region |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Naryn Region |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Osh Region |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

|

Talas Region |

- |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Chui Region |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

|

Bishkek |

3.1 |

2.7 |

2.5 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

|

Osh (city) |

- |

1.9 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

Source: National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (http://stat.kg).

According to the Center for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Development, there is no legislation for biogas plants. Two demonstration plants, however, do exist in the country. They produce 10 million cubic metres of biogas per year from waste. As there is no organised waste collection system, further development of biogas plants is very difficult. At present, biogas is used for electricity production. A by-product of biogas production is a bio fertiliser which is rated as very good.8

3.2.3. Domestic bus prices and fares

Kyrgyzstan does not have a very well-developed domestic automobile or bus industry. Since 2011 the production of vehicles has represented only 0.4-0.7% of the total production of industrial goods, measured in KGS. The economic downturn of 2014-15 is visible in this sector as well (Table 3.5).

Table 3.5. Production of industrial goods in the Kyrgyz Republic, 2013-18

(KGS million)

|

Items |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total |

169 829 |

171 109 |

181 027 |

209 812 |

237 225 |

250 640 |

|

Manufacturing |

141 350 |

140 267 |

140 604 |

163 298 |

181 574 |

189 802 |

|

Production of machinery and equipment not included in other groups |

342 |

408 |

280 |

225 |

373 |

218 |

|

Production of vehicles |

1 018 |

747 |

608 |

906 |

1 190 |

950 |

|

Other production, repair and installation of machinery and equipment |

1 306 |

1 319 |

1 194 |

1 302 |

1 333 |

2 054 |

Source: National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (http://stat.kg).

According to the Trend news agency, manufacture of Isuzu buses and Ravon passenger cars in Kyrgyzstan will begin by the end of 2018. There is already a production area in the city of Osh which will begin with the large-scale assembly of Ravon brands. Bus production is planned in Bishkek. SamAvto’s products, whose partner is the Japanese company Isuzu, is planned to be launched there (Trend AZ, 2017[3]).

According to AzerNews, nine enterprises from Uzbekistan will open production in Kyrgyzstan. Uzavtosanoat, jointly with AvtoOndoozavod, will open two enterprises for assembling agricultural machinery and trailers. In addition, an Uzbek company together with DT Technik and Avtotsentr Estakada from Kyrgyzstan will open factories for assembling buses and servicing transport, respectively (Aliyeva, 2018[4]).

At present however, as domestic capacity is low, essentially all buses will have to be imported.

The following unit prices of imported vehicles should be assumed in the design of the CPT Programme:

new trolleybus: KGS 10.5 million (USD 152 000)

new battery-powered trolleybus (with “autonomous” capability), reference price (imported): KGS 20 million (EUR 255 000; USD 291 000)

new CNG bus: KGS 10 million (USD 145 000)

new LPG bus: KGS 9.09 million (USD 132 000)

new diesel Euro VI bus: KGS 8.7 million (USD 126 000)

standard diesel bus (reference price): KGS 2.08 million (USD 31 000).

The programme will not include minibuses – either new or used (minibuses are foreseen to be replaced by regular buses).

Fares on urban public transport in Bishkek are determined by the Bishkek Mayor’s Office and the City Council. They are fixed as a flat rate and usually paid in cash.

The resolution issued by Bishkek city hall in 26 April 2012 established the following tariffs for passenger transport:

trolleybus – KGS 8 (USD 0.12)

bus – KGS 8 (USD 0.12)

minibus – KGS 10 (USD 0.15)

minibus after 21:00 – KGS 12 (USD 0.17)

taxi from 06:00 to 21:00 o'clock – KGS 10 (USD 0.15)

taxi from 21:00 to 24:00 o'clock – KGS 12 (USD 0.17)

routes (express): from 12 to 17 KGS (USD 0.17-0.25)

special prices exist for retirees, e.g. KGS 5 (USD 0.07) with minibus till 17:00.

In Osh, the following tariffs are applied:

trolleybus – KGS 6 (USD 0.09)

bus – KGS 8 (USD 0.12)

minibus – KGS 10 (USD 0.15)

privileged persons (school students, retirees, disabled people, etc.) – KGS 1 (USD 0.01).

The fare on buses and trolleybuses is paid at the end of the journey as the passenger leaves the vehicle. While passengers do generally follow this procedure, the lack of any fixed system of sale and control of tickets can lead to collection losses. The Bishkek Trolleybus Management employs a very limited number of conductors to collect fares and control tickets.

On minibuses, the fare collected is shared between the driver and his company. The share should guarantee a minimum income for the company. Currently, however, drivers’ incomes are very low – less than USD 80 per month. Keeping at least 10% of the cash received from passengers would allow the driver to at least double his income. This issue can only be resolved by introducing regulated ticket sales.

There are no serious technical obstacles to introducing an electronic fare system. While electronic equipment can be installed in vehicles, the sale system needs to take into account the fact that credit and debit cards are not widely used in Kyrgyzstan, especially among the social groups that use public transport.

3.3. Sources and types of financing for investment projects

Financing investment projects must take into account the economic reality of the country. Indeed, the source of revenues for budgets of cities and municipalities in the Kyrgyz Republic are primarily taxes (income and VAT).

According to the Ministry of Finance, when the tax system changed in recent years, these revenues were negatively affected. A new distribution of taxes is now being considered as an option to compensate cities for their revenue loss. In this restricted budget context, government capacities do not appear sufficient to undertake large-scale investment in transportation rolling stock. Such projects can only be financed with the support of international financial institutions, donors, public money and private investment.

In the past international financing institutions and donors have played key roles in the modernisation of the public transport fleet. State budget financing, either directly through the budget or from special funds, has not been used.

Kyrgyzstan has received substantial support from multilateral and bilateral development agencies. According to a private sector assessment conducted by the Asian Development Bank (ADB, 2013[13]), the major development projects promoting business development in the country are supported by the following donors:

ADB: Asian Development Bank

EBRD: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

GIZ: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit

IFC: International Finance Corporation

IMF: International Monetary Fund

USAID: United States Agency for International Development.

The Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) Program directs 77% of its investments into the transport sector (as of end of 2017).9

In particular, the EBRD has been involved in financing the purchase of new vehicles for urban public transport in Bishkek and Osh. The ADB has also expressed interest in providing loan financing for urban public transport investments, based on an existing credit line established with the government.

Other types of financing that should be considered are:

Local banks: local banks can provide loans as part of the financing mix. Moreover, these banks could manage the project cycle as implementation units (see Section 4.2).

Loan guarantees – the Ministry of Finance can provide loan guarantees to private and municipally-owned public transport enterprises (PTOs) and municipalities can provide loan guarantees to private PTOs.

Interest rate subsidies – public money can be used to cover the difference between the interest rate a commercial bank would need to charge in order to be involved in a given project and the interest rate the borrower has the capacity to pay.

3.4. Conclusions for the CPT Programme

Kyrgyzstan has essentially no domestic production of natural gas, automobiles or buses. Given that the majority of buses – except for new trolleybuses purchased under the EBRD projects – are old and diesel-powered, a support programme aimed at the replacement of ageing public transport fleet is justified.

New models of diesel, CNG or LPG-powered buses offer savings in operating costs (due to lower maintenance costs and cheaper fuel) over old, diesel-powered models. Since Bishkek and Osh already have trolleybuses, these models should continue to be used. Unit prices for CNG, LPG, and electricity are very low compared to world levels; this will have the effect of lowering the calculated public support for the CPT investment programme. Using CNG and LPG to power public transport buses will decrease operating costs, given the lower costs of these fuels compared to diesel. Improved diesel fuels, however, such as Euro V and VI, can also be viable alternatives where CNG and LPG are not available. The Kyrgyz Republic needs to introduce European standards for diesel fuels.

CNG buses are more expensive to buy and may require additional infrastructure in some cities. However, it is also important to point out that diesel buses need special equipment to ensure that emission reductions be met. This equipment increases operating costs, leading some operators to dismantle the equipment. This practice should be discouraged and avoided. For more detailed information, Table A.3 of Annex A to this report compares the key parameters, as well as the advantages and disadvantages of CNG, LPG, and diesel fuel to power buses.

Given that the purchase cost of CNG and LPG-powered buses is higher than new model diesel-powered buses, the programme should provide enough assistance to allow the project to become profitable. This is defined as the point at which the net present value (NPV) of the investment is equal to zero from the point of view of the investing entity (see Annex B). This approach provides an opportunity for direct assistance to the service provider (for example, in the form of a grant) together with a loan, for example from the EBRD or a local bank or banks.

Bibliography

[5] ADB (2013), Private Sector Assessment, Update, Kyrgyz Republic, Asian Development Bank, Manila, http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/linked-documents/cps-kgz-2013-2017-oth-04.pdf.

[4] Aliyeva, K. (2018), “Uzbekistan to open nine enterprises in Kyrgyzstan”, AzerNews, 11 January, http://www.azernews.az/region/125337.html (accessed on 30 August 2019).

[1] Sims, R. and R. Schaeffer (2014), “Transport”, Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York, pp. 599-670, http://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ipcc_wg3_ar5_chapter8.pdf.

[2] T&E (2018), CNG and LNG for vehicles and ships – the facts, European Federation for Transport and Environment, Brussels, http://www.transportenvironment.org/sites/te/files/publications/2018_10_TE_CNG_and_LNG_for_vehicles_and_ships_the_facts_EN.pdf.

[3] Trend AZ (2017), “Production of UzAvtoprom cars in Kyrgyzstan will begin till the end of 2018”, Trend News Agency, 25 December, https://en.trend.az/casia/2840029.html.

Notes

← 1. See EU emission standards for passenger cars and light-duty trucks at: www.dieselnet.com/standards/eu/ld.php.

← 2. For Kyrgyzstan’s crude oil production and consumption, see: https://tradingeconomics.com/kyrgyzstan/crude-oil-production; or www.indexmundi.com/energy/?country=kg.

← 3. For Kyrgyzstan’s natural gas production, see: https://knoema.de/atlas/Kirgisistan/topics/Energie/Gas/Erdgasgewinnung.

← 4. State Agency for Regulation of the Fuel and Energy Complex under the Government of the Kyrgyz Republic (www.regulatortek.kg). For general information about the State Agency in English, see: https://erranet.org/member/kyrgyz-republic.

← 5. See Gazprom Neft information on LPG at: www.gazprom-neft.kg/article/gaz.

← 6. For average world price of petrol, diesel and LPG fuels as well as electricity, see: www.globalpetrolprices.com. For natural gas prices for transport (CNG and LNG), see: http://cngeurope.com.

← 7. See current LPG prices at: www.globalpetrolprices.com/lpg_prices/#hl130. The price at the end of 2018 was about USD 0.37. For planning purposes, however, a significantly higher price was used due to the fact that LPG prices are significantly below world prices at present.

← 8. Personal communication with the Center for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Development (www.creeed.net).

← 9. See CAREC Program’s project portfolio at: www.carecprogram.org/?page_id=13630.