This chapter provides general information on the levels of public and business perceptions of corruption and public trust in Ecuador. It also provides a brief summary of the main actions envisaged by the Ecuadorian public sector to foster the joint responsibility of the private sector, civil society organisations and citizens in promoting public integrity. Finally, this chapter includes a brief analysis of the institutional challenges for public integrity in Ecuador.

Promoting Public Integrity across Ecuadorian Society

1. Main challenges and actions for whole-of-society integrity in Ecuador

Abstract

1.1. Understanding the main challenges and ongoing actions to cultivate a culture of public integrity across Ecuadorian society

Public integrity is not just a matter for the public sector: individuals, civil society organisations (CSOs) and businesses can harm or promote public integrity through their actions (OECD, 2020[1]). In fact, as active members of society, individuals, CSOs and businesses have a shared responsibility to promote public integrity, especially considering that these actors interact with public servants on a daily basis, play a key role in setting the public agenda and have the power to influence public decisions.

There are many actions by individuals, CSOs and companies that can harm public integrity. For example, when citizens evade taxes, use public services without paying and/or seek access to social benefits fraudulently, they are taking public resources unfairly and undermining interpersonal trust. In turn, when companies offer bribes in exchange for contracts with public entities and/or provide illegal funds to political parties and/or certain candidates, they threaten the legitimacy of the democratic system and contribute to undermining citizens' trust in public institutions. Also, when CSOs implement strategies to misinform and/or manipulate public opinion, they help to distort public decision making in favour of a powerful few.

Aware of this, the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity places particular emphasis on the importance of promoting a whole-of-society culture of public integrity, partnering with the private sector, CSOs and citizens, through the following actions:

"a) recognising in the public integrity system the role of the private sector, civil society and individuals in respecting public integrity values in their interactions with the public sector, in particular by encouraging the private sector, civil society and individuals to uphold those values as a shared responsibility;

b) engaging relevant stakeholders in the development, regular update and implementation of the public integrity system;

(c) raising awareness in society of the benefits of public integrity and reducing tolerance of violations of public integrity standards and carrying out, where appropriate, campaigns to promote civic education on public integrity, among individuals and particularly in schools;

d) engaging the private sector and civil society on the complementary benefits to public integrity that arise from upholding integrity in business and in non-profit activities, sharing and building on, lessons learned from good practices” (OECD, 2017[2]).

In Ecuador, corruption is one of the main concerns of citizens and businesses. In the case of citizens, 93% of Ecuadorians say that corruption is a “big problem” or a “very big problem” in the national government (Fundación Cuidadanía y Desarrollo and Transparency International, 2023[3]). In the case of the private sector, 49.4% of the companies surveyed in 2017 through the World Bank Enterprise Surveys identified corruption as a significant constraint in Ecuador; this value is higher than the regional average1 of 44.9% (The World Bank, 2017[4]).

In addition, the 2021 report of the Latinobarómetro Corporation complements this view by showing that 72% of Ecuadorians believe that the level of corruption in the country has increased in relation to the year immediately prior to the survey (Corporación Latinobarómetro, 2021[5]). This figure presents a significant increase compared to the same indicator in 2018, when 56% of Ecuadorians believed that the level of corruption in the country had increased compared to the year before the survey was conducted (Corporación Latinobarómetro, 2018[6]).

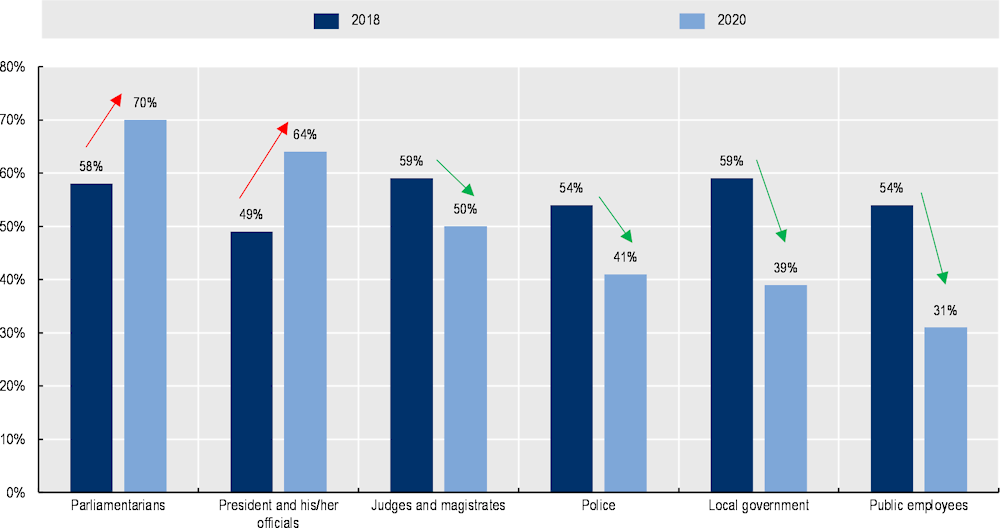

When differentiating between the main institutions of a democracy, the 2021 report by the Latinobarómetro Corporation reveals that Ecuadorians think that the main actors involved in acts of corruption are “parliamentarians”(70%), followed by the “president and his officials” (64%) and “judges and magistrates” (50%) (Figure 1.1). When this data is compared with the 2018 report by the same corporation, corruption perception levels for “parliamentarians” and the “president and his officials” increased significantly from 2018 to 2021, while corruption perception levels for all other actors decreased significantly over the same period (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Perception of corruption by institution in Ecuador

Beyond perceptions, Ecuadorians and businesses experience corruption in their daily lives. The following data gives an overview of experiences of corruption and lack of integrity in Ecuador:

15% of Ecuadorians indicate that they or a relative have known about an act of corruption, slightly lower than the regional average2 of 16% (Corporación Latinobarómetro, 2018[6]).

28% of Ecuadorians report having paid a bribe to access basic services - basic services refers to i) public hospitals, ii) public schools, iii) identification, iv) voter credentials or permits, v) police, and vi) utilities and courts - in the 12 months prior to when the survey was conducted; this value is equivalent to the regional average3 of 28.2% (Transparency International, 2017[7]). Public hospitals are the basic service with the highest bribe payments in Ecuador, with a percentage corresponding to 21-30% of users (Transparency International, 2017[7]).

62% of Ecuadorians who used at least one of the essential public services - essential public services refers to i) national police, ii) schools or colleges, iii) higher education centres, iv) hospitals, v) institutions providing basic services such as water, electricity and sanitation, and vi) government offices to obtain a document - used personal contacts or asked for favours to get what they needed (Fundación Cuidadanía y Desarrollo and Transparency International, 2023[3]).

15% of Ecuadorians say they have received an offer of a bribe or special favour to vote a certain way in a national, regional or local election in the last 5 years (Fundación Cuidadanía y Desarrollo and Transparency International, 2023[3]).

5.9% of companies report having received at least one request for bribe payment, lower than the regional average of 9.2%4 (The World Bank, 2017[4]).

In light of these challenges, the Government of Ecuador has been designing and implementing different actions to strengthen the culture of public integrity in the whole of Ecuadorian society.

First, in the first half of 2021, the Ecuadorian government presented the National Development Plan called “Plan for the Creation of Opportunities 2021-2025” (Plan de Creación de Oportunidades 2021-2025), which proposes a roadmap for Ecuador in the short and medium term. One of the objectives of the National Development Plan is 15 "To promote public ethics, transparency and the fight against corruption" for which it proposes to carry out “an integral and co-ordinated fight of the public sector, the private sector and civil society” (Government of Ecuador, 2021, p. 99[8]). Specifically, under policy 15.1 “Promote public integrity and the fight against corruption in effective inter-institutional co-ordination between all state functions and citizen participation” the National Development Plan also recognises the need to guarantee a comprehensive and co-ordinated fight in the public sector and to involve citizens in public action in order to generate social control that allows for the prevention, reporting and effective prosecution of corruption cases. However, this vision proves to be limited, as it presents lack of integrity as exclusive actions of public servants and centres the role of the citizenry on that of control. In that sense, it does not emphasise the principle of co-responsibility, or shared responsibility, suggested under principle 5 of the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity, which recognises that bad practices come not only from the public sector, but also from the side of citizens, CSOs and businesses, and thus the responsibilities of these actors should go beyond control.

Second, in November 2021, the Ecuadorian government presented the General Guidelines of the National Anti-Corruption Policy (Lineamientos Generales de la Política Nacional Anticorrupción), on the initiative of the Presidency of the Republic. These guidelines were developed to guide the construction of a national anti-corruption policy, with special emphasis on inter-institutional co-ordination and exchange, and the prevention of corruption through public integrity, transparency, participation and accountability. The General Guidelines of the National Anti-Corruption Policy highlight the relevance of involving citizens, CSOs, academia, the private sector and the media in the promotion of integrity and the fight against corruption, for example, through the active participation of these groups in the construction of a national anti-corruption strategy and as observers within the body in charge of co-ordinating its implementation (Presidency of Ecuador, 2021[9]).

Third, in July 2022, the Ecuadorian government presented the National Anti-Corruption Strategy (Estrategia Nacional Anticorrupción, ENA) in an event attended by authorities from all state functions and levels of government, as well as representatives from all levels of Ecuadorian society. The ENA was drafted based on the General Guidelines of the National Anti-Corruption Policy and inputs received through a public consultation process that took place between January and February 2022. This public consultation process for the General Guidelines of the National Anti-Corruption Policy consisted of workshops, interviews and surveys involving representatives from academia, production and labour unions, the media, CSOs, political organisations and the public sector (more information on this process is presented in Chapter 2).

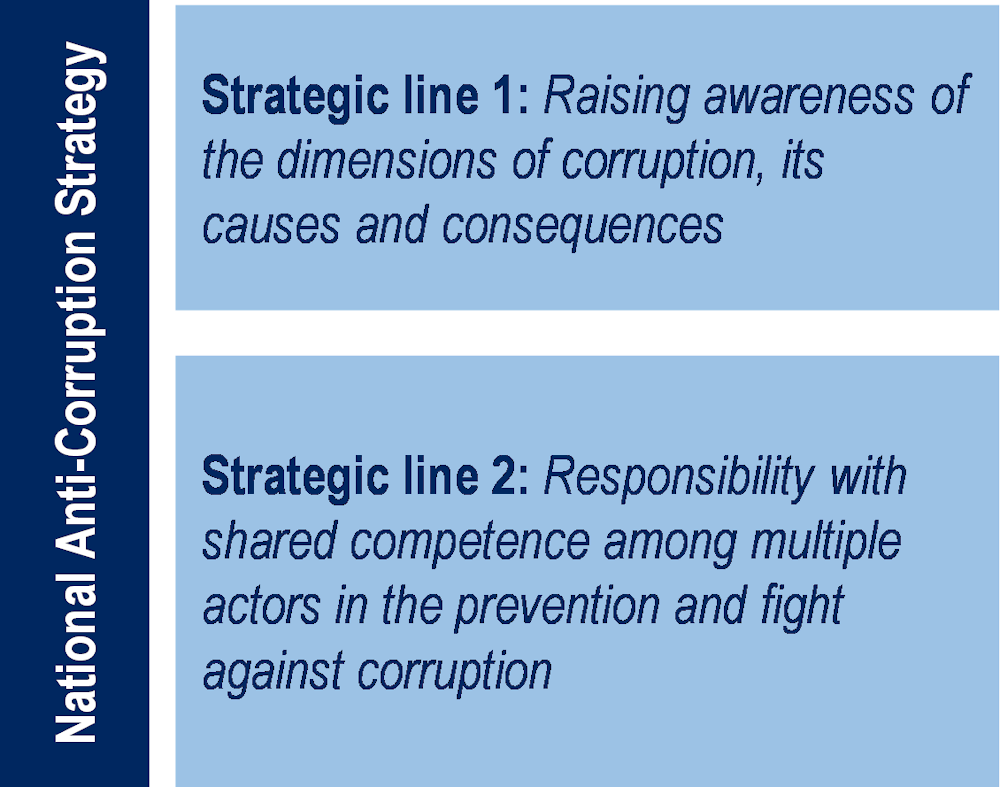

Furthermore, the ENA recognises the role of the private sector and civil society in the promotion of public integrity and the fight against corruption, by acknowledging that corruption-related crimes not only arise as a consequence of failures of integrity by public servants but also require “complicity that can come from the private and social spheres” (Presidency of Ecuador, 2022, p. 6[10]) and therefore “public and private co-responsibility to prevent and sanction corruption” is essential (Presidency of Ecuador, 2022, p. 7[10]). In this regard, two of the eight national strategic lines of the ENA focus directly on raising awareness of the role of the private sector and civil society in the promotion of public integrity and strengthening that role (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. ENA strategic lines related to the whole-of-society approach to public integrity

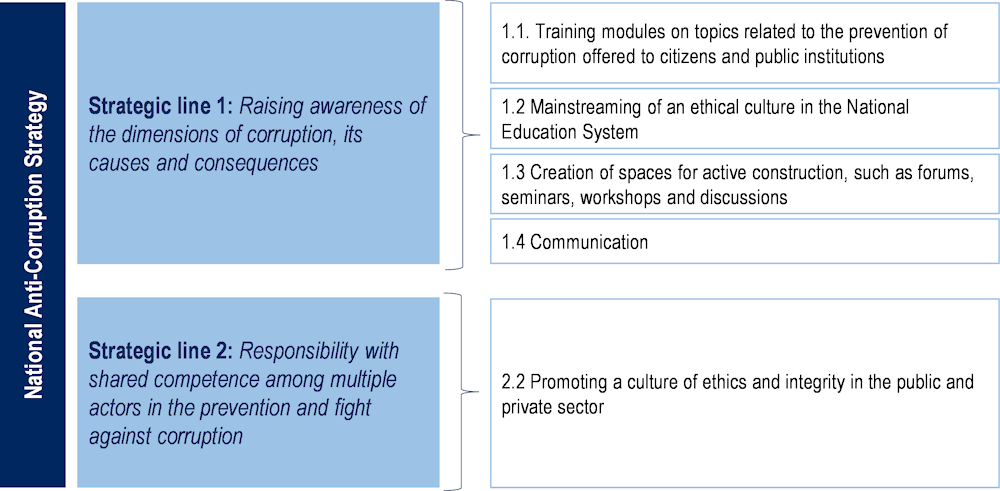

Additionally, in October 2022, the Secretariat for Anti-Corruption Public Policy (Secretaría de Política Pública Anticorrupción, SPPA) published the 2022-2025 ENA Action Plan, which includes the objectives, expected results and lines of action associated with each of the eight national strategic lines of the ENA. The action plan includes, among others, actions aimed at cultivating a culture of integrity in the whole-of-society. For example, in the case of national strategic lines 1 and 2, the action plan establishes concrete actions to be implemented by the SPPA, in co-ordination with relevant public and private sector entities, in order to promote public integrity in the whole of Ecuadorian society (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3. ENA action plan actions related to the whole-of-society approach to public integrity

Source: Prepared by the OECD based on the ENA action plan, (Secretariat for Anti-Corruption Public Policy, 2022[11]).

Although it was initially foreseen that this action plan would reflect the commitment of the Ecuadorian public sector to public integrity by gathering activities to be implemented jointly and co-ordinated by the different entities with responsibilities within the national integrity system, due to the political context and resource constraints, the SPPA decided to elaborate an action plan with specific actions to be co-ordinated with other relevant actors. This is in line with its functions and attributions in terms of co-ordination with the competent entities for the implementation of the ENA, as established in Executive Decree 412 of 2022. The SPPA reported that it continues to work on the participatory construction of an ENA action plan that incorporates the commitments of all sectors of Ecuadorian society.

Beyond the Executive Function, there are efforts by other functions to cultivate a culture of public integrity in Ecuadorian society. For example, the Transparency and Social Control Function (Función de Transparencia y Control Social) – which includes the Comptroller General’s Office (Contraloría General del Estado), the Ombudsman’s Office (Defensoría del Pueblo), the Council for Citizen Participation and Social Control (Consejo de Participación Ciudadana y Control Social), and the superintendencies of Banks (Bancos), Companies, Securities and Insurance (Compañías, Valores y Seguros), Control of Market Power (Control del Poder de Mercado), Popular Solidarity Economy (Economía Popular Solidaria), and Spatial Planning, Land Use and Land Management (Ordenamiento Territorial, Uso y Gestión del Suelo) – developed the National Public Integrity and Anti-Corruption Plan for 2019-2023 (Plan Nacional de Integridad Pública y Lucha Contra la Corrupción 2019-2023, PNIPLCC). This Plan identifies the main causes of corruption and proposes actions to mitigate these causes, within the framework of 3 strategic objectives that are directly related to the purpose of fostering a culture of public integrity in the whole-of-society, namely:

“1. Promote integrity in public and private management of public resources

2. Strengthen citizen action in its various forms of organisation to have an impact on public affairs.

3. Strengthen public and private inter-institutional co-ordination and co-operation mechanisms that co-ordinate initiatives and actions for the prevention and fight against corruption” (Transparency and Social Control Function, 2019, p. 66[12]).

However, despite its purpose of contributing to the promotion of a culture of integrity in the whole-of-society, the PNIPLCC lacks a sense of ownership by relevant actors in other branches of government, which has hindered its implementation and limited its impact (OECD, 2021[13]). In addition, no periodic monitoring and/or evaluation reports on the implementation of the PNIPLCC were found, making it difficult for citizens and other relevant actors to know the progress made and to join efforts in favour of public integrity. In this regard, and considering that the Transparency and Social Control Function will soon begin the process of designing the National Public Integrity and Anti-Corruption Plan for the next period, it is necessary to ensure co-ordination, in the planning and implementation stages of the new Plan’s actions, with the relevant public entities of other State functions, such as the SPPA, the Ministry of Education (Ministerio de Educación), the National Public Procurement Service (Servicio Nacional de Contratación Pública), among others, as well as with other actors in Ecuadorian society.

This report assesses current Ecuadorian public sector initiatives aimed at citizens, CSOs and the private sector to cultivate a culture of integrity in the whole-of-society and to foster co-responsibility in the promotion of public integrity. Based on the analysis of the current situation, this report provides specific recommendations tailored to the Ecuadorian context to inform future actions to strengthen the public integrity approach in the whole-of-society.

1.2. Strengthening institutions for public integrity in Ecuador

1.2.1. The Ecuadorian government could strengthen the focus and organisation of the Anti-Corruption Public Policy Secretariat to reinforce its stability as the main institution with responsibilities for public integrity in the Executive Function

Since 2007, Ecuador has made several attempts to create a Secretariat within the Presidency of the Republic with responsibility for integrity and anti-corruption issues within the Executive Function. This includes the (first) National Anti-Corruption Secretariat in 2007, the National Secretariat for Management Transparency in 2008, the Secretariat General for Public Administration in 2013 – whose responsibilities were then delegated to other secretariats in 2017, the (second) Anti-Corruption Secretariat in 2019 – abolished in 2020 without any formal handover of its managerial and co-ordinating roles to any other institution, and finally the current SPPA, created in 2022.

These repeated institutional changes of the main institution with responsibilities for public integrity in the Ecuadorian Executive Function have led to a lack of continuity in the efforts to promote public integrity in Ecuador and to consolidate a national public integrity system. International good practice shows that integrity policies, especially preventive measures, require consistency and continuity over a longer period of time in order to develop and show their impact (OECD, 2017[14]). International experiences also show that constant institutional changes resulting from short-term political fluctuations as well as arbitrary changes in the ownership of integrity bodies can undermine the continuity and coherence of policies over time, in particular those aimed at incrementally but sustainably building institutional capacities for integrity (OECD, 2017[14]).

In addition, considering that several of the SPPA’s functions and powers are aimed at effective co-ordination between institutions with responsibility for public integrity both within the Executive Function and between State Functions, it is essential to ensure its continuity with a view to strengthening good working relations and the bonds of trust with these public entities, which are necessary for the effective fulfilment of its functions and powers to promote public integrity.

Considering the above, it is essential to ensure that there is a stable institution within the Ecuadorian Executive Function that is focused on promoting a strategic and sustainable response to corruption through public integrity. In Ecuador, this objective is addressed with the creation of the SPPA in 2022, in the sense that Executive Decree 412 of 2022 grants it specific functions and attributions to strengthen public integrity and prevent corruption within the Executive Function and in co-ordination with other State Functions, levels of government and key actors of society. However, to mitigate the continuity, coherence and co-ordination risks mentioned above and to provide a stronger institutional basis to effectively promote public integrity in Ecuadorian society, the Ecuadorian government could consider strengthening the focus and organisation of the main institution with responsibilities for public integrity in the executive function: the SPPA.

To this end, international good practice has demonstrated the importance of addressing and strengthening the following elements (OECD, 2017[14]; OECD, 2019[15]):

Maintain a separation between the functions of preventing corruption and detecting and sanctioning corruption cases, in order not to undermine the credibility and effectiveness of the preventive and advisory function of the main institution with responsibility for public integrity in the Executive Function, in the case of Ecuador, the SPPA. International good practices show the importance of clearly differentiating between the preventive function, focused on promoting a culture of public integrity, and the function of detecting and sanctioning cases of corruption. There are several reasons why this separation is advisable. First, this separation strengthens the credibility of the unit responsible for public integrity and facilitates the establishment of trust with a view to strengthening its advisory role. Second, experience has shown that units with this dual role devote a large part of their efforts and resources to receiving complaints, while not enough resources are devoted to prevention and promotion of a culture of integrity (OECD, 2019[15]). Third, attributing actions in the field of detection and sanctioning such as receiving complaints and collecting information on alleged acts of corruption to the unit responsible for integrity could generate false expectations or perceptions, as without the full investigative and sanctioning powers people may get the false impression that this unit is not efficient (OECD, 2019[15]) or it is politicised. Regarding the third argument, paragraph 16 of Executive Decree 412 of 2022 states that the SPPA is responsible for “gathering information on alleged irregularities or acts of corruption…” which could create confusion regarding the scope of the SP’A's responsibilities, in particular, its role in investigating and sanctioning alleged irregularities or acts of corruption that it detects. Moreover, while this paragraph states that the information collected by the SPPA should be brought “to the attention of the competent judicial and/or administrative authorities”, without proper communication, this could create false expectations regarding the role of the SPPA or raise suspicions of politicisation by collecting and/or transferring information on certain cases and not others.

Strengthen and make more visible the preventive and integrity policy advisory work of the main institution with responsibility for public integrity in the Executive Function, in the case of Ecuador, the SPPA. This, considering that the name of the SPPA could lead to confusion between the proactive approach of promoting a culture of public integrity (prevention) in line with the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity (2017[2]) and a more traditional approach of detection and sanctioning individual corruption cases.

Establish and enforce explicit legal or regulatory requirements that allow for the selection of suitable profiles to lead the main institution with responsibility for public integrity in the Executive Function, in the case of Ecuador, the SPPA. This includes profiles that include integrity criteria, as well as clear and transparent appointment, removal and evaluation procedures.

Guarantee a certain degree of administrative, organisational and financial autonomy that allows for autonomous decision making by the main institution with responsibilities for public integrity in the Executive Function, in the case of Ecuador, the SPPA. For example, a certain degree of administrative autonomy could be guaranteed to the SPPA concerning the definition of its communication strategy, so that the General Secretariat of Communication of the Presidency of the Republic (Secretaría General de Comunicación de la Presidencia de la República, SEGCOM) would not have the function of reviewing and endorsing the SP’A's actions in this area, but only of providing technical support.

The Ecuadorian government could consider strengthening the approach and organisation of the SPPA based on a short- and medium-term strategy that addresses the different elements mentioned above.

1.2.2. Ecuador could strengthen the institutional co-ordination body in charge of overseeing the implementation of the ENA to ensure strategic co-operation among the five state functions and levels of government, with the contribution of civil society, academia and the private sector

In Ecuador, public integrity responsibilities are assigned to different institutions that belong to the five Functions of the State - namely the Executive, Legislative, Judicial, Electoral, and Transparency and Social Control functions. For example, within the Executive Function, the SPPA leads the fight against corruption in the Executive and co-ordinates integrity and anticorruption actions with other State Functions, while the Ministry of Labour (Ministerio de Trabajo), the Ministry of Education and the Financial and Economic Analysis Unit (Unidad de Análisis Financiero y Económico, UAFE) have complementary competencies that are key to the public integrity system. Within the Judicial Function, the Prosecutor General Office (Fiscalía General del Estado) has a leading role as the institution responsible for conducting preliminary investigations and criminal prosecution of corruption-related offences (OECD, 2021[13]), and within the Transparency and Social Control Function, the Council for Citizen Participation and Social Control is responsible for facilitating citizens’ participation for transparency.

Until mid-2022, despite the existence of a multiplicity of institutions with integrity responsibilities, Ecuador lacked institutional arrangements, both formal and informal, on public integrity that could bring together the relevant bodies of all functions and different levels of government in a complete and integrated manner (OECD, 2021[13]). Indeed, although there were some integrity co-operation mechanisms in place with regards to enforcement, for example, the Inter-institutional Co-operation Agreement to strengthen the fight against corruption and asset recovery signed in 2019 between the Judiciary Council (Consejo de la Judicatura), the then existing Anti-Corruption Secretariat, the Comptroller General's Office, the Attorney General's Office (Procuraduría General del Estado), the Prosecutor General's Office, and the UAFE, and within state’s functions , for example, the Co-ordination Committee of the Transparency and Social Control Function composed of the head of each of the entities that make up this function (OECD, 2021[13]), these mechanisms did not cover all relevant instances of the Ecuadorian integrity system.

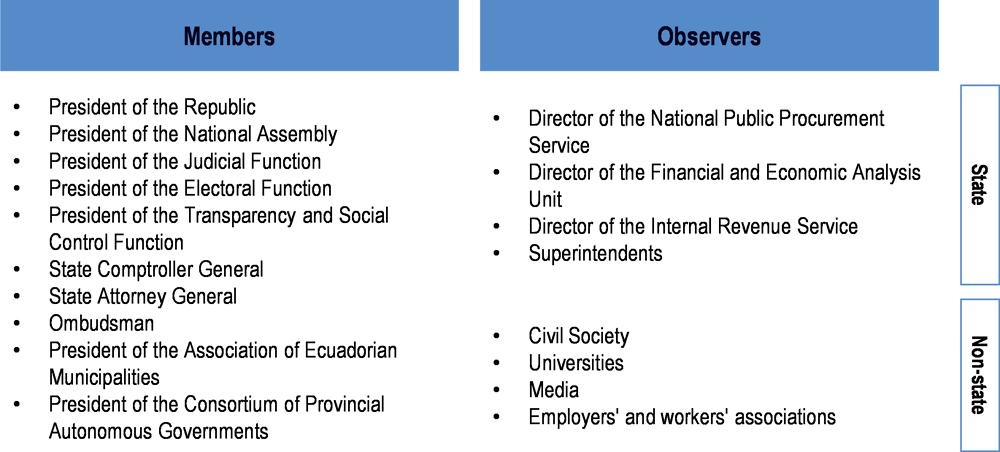

Considering this and in order to remedy the lack of institutional arrangements on public integrity that would guarantee dialogue and co-ordination among all relevant bodies (OECD, 2021[13]), the Ecuadorian government provided for the creation of an inter-institutional co-ordination body for the prevention of corruption within the framework of the ENA. This, in line with international good practices and the recommendations of the OECD Report on Public Integrity in Ecuador: Towards a National Integrity System (2021[13]). This co-ordinating body brings together representatives of all relevant public sector institutions from all five state functions (some as members and others as observers) as well as representatives of sub-national governments. It also seeks to foster a dialogue with civil society, academia, the media and the private sector by convening them as non-governmental observers (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4. Inter-institutional co-ordination body for the prevention of corruption

The responsibilities of the inter-institutional co-ordination body for the prevention of corruption include the articulation and co-ordination of public entities with responsibilities on public integrity belonging to the five state functions and the formulation of policies in the area of integrity and the fight against corruption. Both the composition and the responsibilities of the inter-institutional co-ordination body for the prevention of corruption are appropriate for the Ecuadorian context and are in line with international good practices.

However, since its proposed establishment in July 2022 (the body was actually set up in October 2022), the inter-institutional co-ordination body for the prevention of corruption has only met on two occasions - in October and November 2022 - convened by the Presidency of the Republic. At the first meeting, the integrity and anti-corruption initiatives of the different members were presented in order to design an inter-institutional roadmap and propose joint objectives. At the second meeting, five Public Integrity Roundtables were established, namely: (1) culture and education, (2) strengthening public service and meritocracy, (3) regulatory reforms, (4) quality of public spending, and (5) statistics and technology It was also agreed that the SPPA will act as Technical Secretariat of the co-ordinating body, in order to follow up on the commitments generated in the five Public Integrity Roundtables.

Although the co-ordinating body has not been restored due to political reasons and no new meetings have been scheduled or held during the first five months of 2023, the dialogue held in the first two meetings has served to push forward the initiatives reported by several of its public and private members - for example, co-operation between the Executive and Judicial functions to improve the transfer of information and generate adequate anonymous reporting protocols, demonstrating the relevance of this type of dialogue and co-ordination on integrity issues. In addition, while the co-ordinating body is restored, the SPPA has played a key role as co-ordinator and articulator, holding bilateral meetings with the different institutional actors that make it up and supporting the implementation of concrete actions discussed in the framework of the first meetings - for example, capacity building to strengthen public service and the implementation of institutional corruption risk management mechanisms.

However, despite the SPPA's efforts to encourage co-ordination and dialogue in the current context, the temporary suspension of the inter-institutional co-ordination body for the prevention of corruption has raised concerns among its members and observers, particularly with regard to its continuity and true capacity to promote articulation and co-ordination amongst the different public entities with responsibilities in the area of public integrity.

In addition, interviews during the fact-finding mission evidenced that, despite recent efforts by the Ecuadorian government to strengthen the foundations of the national integrity system, there are still institutional weaknesses that could undermine the effectiveness of any measures to be implemented in the area of public integrity. Indeed, there is still a lack of clarity on the scope of many of the integrity responsibilities of Ecuador's public entities and how they should articulate and communicate with each other in order to carry out their functions efficiently. In this regard, a task that remains pending is the institutionalisation of the National Public Integrity and Anti-Corruption System, in co-ordination between the SPPA, the Ministry of Labour, the Secretariat of Public Administration and Cabinet (Secretaría de Administración Pública y Gabinete), and other relevant public entities, also involving civil society, the private sector and the academia, in order to generate commitments from all sectors and levels of the Ecuadorian society (OECD, 2021[13]).

Moreover, repeated institutional changes aggravate this situation and often result in the loss of relevant information and difficulties in managing institutional knowledge. For example, the constant changes in the authority responsible for public integrity in the Executive Function resulted in a lack of continuity in the efforts to cultivate public integrity and fight corruption in previous years, and although there is now an entity with clear responsibilities for public integrity and anti-corruption - the SPPA - its focus and organisation need to be strengthened so that it does not suffer the same fate as its predecessors. Also, following recent changes in the structure of the Presidency of the Republic, it is unclear who the institutional actors responsible for several of the actions set out in Executive Decree No 4 of 2021 are – such an Executive Decree contains the standards of ethical governmental behaviour for all public officials of the Executive Function, including the function of supervising and enforcing its compliance.

For all the above, although there is currently an entity within the Executive Function with the power to co-ordinate co-operation between the institutions of the Executive Function and other state functions aimed at promoting public integrity, Ecuador could strengthen the inter-institutional co-ordination body for the prevention of corruption to ensure strategic co-operation between the five state functions and all levels of government, with the contribution of civil society, academia and the private sector. This is in line with the recommendations of the OECD Report Public Integrity in Ecuador: Towards a National Integrity System (2021[13]).

Notes

← 1. The regional average for Enterprise Surveys data includes data from Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay.

← 2. The regional average for information on an act of corruption includes information from Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela.

← 3. The regional average on having paid a bribe to access basic services includes information from Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Jamaica, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay and Venezuela.

← 4. The regional average for companies reporting having received at least one bribe payment request includes information from Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay.