This introductory chapter discusses the governance concerns related to lobbying and influence practices and the current lobbying landscape in Chile. It also retraces the various steps that led to the adoption of a Lobbying Act in 2014, briefly discusses its key strengths and weaknesses, and introduces the main recommendations provided throughout the report to strengthen the existing foundation and set up a strong, effective, resilient and proportionate framework for lobbying that is consistent with the broader public integrity framework and that adequately addresses emerging risks related to the evolving lobbying and influence landscape.

The Regulation of Lobbying and Influence in Chile

1. Towards a modernised framework to ensure transparency and integrity in lobbying in Chile

Abstract

1.1. Introduction

Public policies are the main ‘product’ people receive, observe and evaluate from their governments. When designing and implementing these policies, governments need to acknowledge the existence of diverse interest groups and consider the costs and benefits for these groups. By sharing their expertise, legitimate needs and evidence about policy problems and how to address them, interest groups and their representatives can provide governments with valuable information on which to base their decisions. It is this variety of interests that allows policymakers to leverage knowledge and resources from beyond the public administration, learn about options and trade-offs, better understand citizens and stakeholders’ evolving needs and ultimately decide on the best course of action on any given policy issue (OECD, 2010[1]).

However, lobbying and influence activities, understood as all actions aimed at promoting the interests of various interest groups with reference to public decision-making and electoral processes, can have a profound impact on the outcome of public policies. Depending on how they are conducted, these activities can greatly advance or block progress on major global challenges (OECD, 2017[2]; OECD, 2021[3]). On the one hand, an inclusive policymaking process can lead to more informed and ultimately better policies and increase the legitimacy of public decisions. On the other hand, experience has shown that policymaking is not always inclusive and at times may only consider the interests of a few, usually those that are more financially and politically powerful. Experience also shows that lobbying and other practices to influence governments may be abused through the provision of biased or deceitful evidence or data, and the manipulation of public opinion (OECD, 2021[3]).

The consequences of this undue influence on the economy and society are widespread. When public decision makers pursue policies that further their private interests or the commercial or political interests of other groups, whether domestic or foreign, who attempt to influence them, there is a risk that decisions concerning essential public policies, such as health or consumer protection policies, have harmful impacts instead of promoting the economic and social well-being of individuals. In fact, studies increasingly show that situations of undue influence and inequity in influence power have led to the misallocation of public resources, reduced productivity, perpetuated social inequalities and sometimes led to deadly policy outcomes (OECD, 2017[2]; OECD, 2021[3]). Ultimately, public policies that are misinformed and respond only to the needs of a specific interest group can negatively affect trust in government institutions, possibly resulting in the dissatisfaction of the public as a whole towards public institutions and democratic processes.

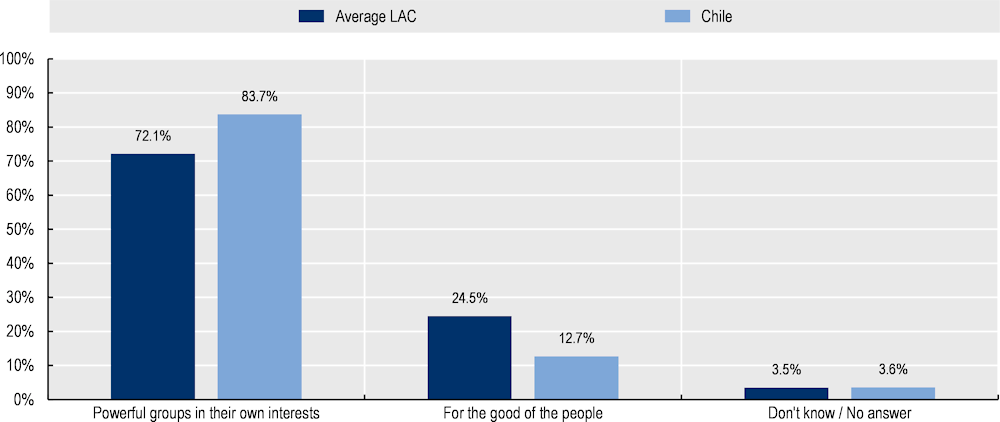

1.2. Addressing the governance concerns related to lobbying and influence practices in Chile

Chile is no stranger to the challenges described above. While the country’s democratic institutions have been stable and well-functioning since the first free presidential and parliamentary elections were held in 1989, perception indices show a persistent gap between the political class and the demands of the population (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2024[4]). According to the 2023 Latinobarómetro survey, 83.7% of respondents in Chile think that their country is governed for a few powerful groups in their own interest, while 12.7% believe Chile is governed for the good of all people (Figure 1.1). The score is more than 11 points above the average of all Latin American countries (72.1%) covered by the survey, indicating that citizens in Chile perceive that policies are unduly influenced by narrow interests, and/or that powerful groups exert too much influence on the outcomes of public decision-making processes.

Figure 1.1. Citizens in Chile perceive that a few powerful groups govern their country

Respondents were asked the following question: “Generally speaking, would you say that your country is governed for a few powerful groups in their own interest? Or is it governed for the good of all?”

Note: This survey has been conducted in 17 countries in the LAC region (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, México, Panamá, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela).

Source: Latinobarómetro (2023), https://www.latinobarometro.org/latOnline.jsp.

In addition, when asked in 2020 who they think has most power in Chile, 46.2.1% of respondents put big companies first, while 12.2% put political parties and 11.6% the Government first (Corporación Latinobarómetro, 2021[5]). In another survey from 2022, only 38% of Chilean citizens responded that they trusted the media (compared to 47% in 2017) and a vast majority (83%) believed that the media were not independent from undue business or commercial influence (Reuters Institute for the study of journalism, 2022[6]).

This data is consistent with the views shared by various stakeholders in Chile interviewed for this report, who confirmed that the word “lobby” has a negative connotation and is often associated with opaque activities or even corruption, influence peddling and the capture of public policies, regulations and administrative decisions. This perception of an opaque relationship between the public and private sectors in Chile was further highlighted by the massive protests taking place throughout the country in 2019 and a highly polarised presidential election in 2021 (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2024[4]).

While the agreement between political parties to launch a new constitutional process – Agreement for Social Peace and the New Constitution (Acuerdo por la Paz Social y la Nueva Constitución) – led to a plebiscite in the October 2020 referendum (80% of Chileans voted in favour of replacing the old Constitution), and the establishment of a Constituent Convention to draft a new constitution, which began its work in July 2021, voters overwhelmingly rejected the new draft (62% voted against) in September 2022. In December 2022, Chilean lawmakers announced an agreement on the process to begin drafting a new Constitution, which was prepared by a body of 50 constitutional advisors elected by direct vote, based on a preliminary draft prepared by a commission of 24 experts. The proposed text was again rejected by a majority of voters (56%) on 17 December 2023, marking the end of a four-year process to replace the existing Constitution.

At the same time, this series of events has also shown the breadth and diversity of Chile’s lobbying and influence landscape, and in particular the wide variety of interest groups active on a broad range of societal issues, including community organisations, student and indigenous organisations as well as professional associations. In particular, the sector has grown both quantitively and qualitatively in recent years. More than 339 000 not-for-profit organisations are registered in the Registry of Non-Profit Legal Entities kept by the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights as of July 2023 (Presidential Advisory Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency of Chile, 2023[7]), and it is estimated that a total of 214 000 of these organisations were active in Chile in 2020 (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2024[4]). While the country has had a limited tradition of public participation in the past (OECD, 2017[8]), between 2015 and 2020 alone the number of not-for-profit organisations increased from 234 000 to 319 000 (+27%). Between 2005 and 2018, social organisations grew at a higher rate than companies and the national population (Presidential Advisory Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency of Chile, 2023[7]). In addition, the capacity of social movements and civil society organisations to engage on specific problems and influence decision-making processes has also increased, and smaller organisations are increasingly able to counterbalance more powerful and well-established interest groups. Traditions of civil society participation and community organisations are also relatively strong in rural areas (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2024[4]).

This increased level of informal political activism and interest representation has also been made possible by the substantial progress made by Chile in recent years to strengthen equity, transparency and integrity in public decision making. For example, the Statute on access to public information (Ley No. 20.285 sobre Transparencia de la Función Pública y Acceso a la Información de los Órganos de la Administración Pública), which was approved by Congress in 2008 and implemented in 2009, has significantly improved access to information and is effectively enforced by the Transparency Council (Consejo para la Transparencia, CPLT). In addition, regulations on citizen participation in public policy, campaign finance, conflict-of-interest, asset and interest declarations have been introduced and progressively strengthened over the past years.

Most importantly, Law No. 20.730 regulating lobbying and the representation of private interests before authorities and civil servants (Ley No. 20.730 que regula el lobby y las gestiones que representen intereses particulares ante la autoridades y funcionarios – hereafter “the Lobbying Act”), was introduced in 2014 following eleven years of parliamentary debate and proceedings. The Act constituted a significant advance in strengthening the transparency and integrity of decision-making processes in Chile, including at the local level. Article 1 of the Act states that the objective of the law is to “regulate publicity in lobbying and other activities that represent private interests, with the aim of strengthening transparency and probity in relations with bodies of the State”. It imposes a duty on public authorities and public officials to record and publicise meetings and hearings requested through an online registration portal by lobbyists and managers of private interests seeking to influence a public decision, as well as travel undertaken in the exercise of their functions, and gifts they receive as part of protocol or that are authorised as a manifestation of courtesy and good manners in the exercise of public duties. Thus, the Act not only enshrines the legitimacy of lobbying in the legal framework but also implements fundamental rights such as the right to information (about who is attempting to influence government), freedom of expression and the right to petition government. Between November 2014 and October 2023, a total of 673 000 hearings, 690 439 travels and 54 821 donations were published on the InfoLobby transparency portal (Presidential Advisory Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency of Chile, 2023[9]).

1.3. The Lobbying Act in Chile: a leading system among OECD countries that needs to be strengthened to adequately address lobbying-related risks

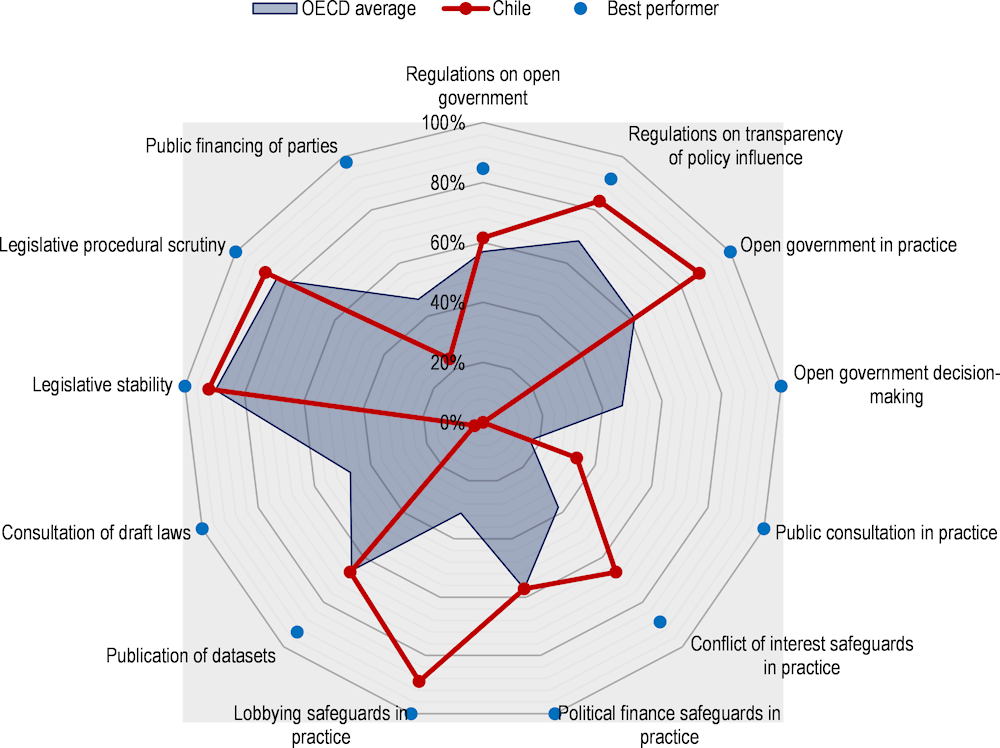

As a result, the Chilean framework on lobbying aligns well with the principles enshrined in the OECD Recommendation on Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying and Influence (OECD, 2010[1]) (hereafter, “the OECD Recommendation on Lobbying and Influence”), adopted in 2010 and amended in 2024. The OECD Public Integrity Indicator for Principle 13 of the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity also shows that Chile performs better than the OECD average in the sub-indicators on “Regulations on transparency of policy influence” and “Lobbying safeguards in practice” (Figure 1.2). In particular, the indicators show a strong regulatory framework for transparency in lobbying and political finance, compared to other OECD countries. Chile has especially strong lobbying safeguards in practice and is close behind the OECD top performer, fulfilling 8 out of 9 criteria relating to lobbying transparency and enforcement. For example, Chile is one of few countries to publish aggregated lobbying data.

Figure 1.2. The OECD Public Integrity Indicator for Accountability of Public Policymaking in Chile

Notes: The OECD Public Integrity Indicators measure, amongst others, the quality of frameworks for accountability of public policymaking (Principle 13 of the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity). The criteria for each indicator were established by the OECD Working Party on Public Integrity and Anti-Corruption (WP-PIAC).

Source: OECD Public Integrity Indicators, https://oecd-public-integrity-indicators.org/

However, challenges remain in terms of clarifying lobbying definitions and the scope of the law, adapting the framework to the evolving lobbying landscape, in particular with the advent of digital technologies and social media, as well as setting up effective mechanisms for compliance and enforcement. There are also a number of other improvements that could be made to the lobbying registration system and transparency portals. Lastly, the indicators show that Chile currently lacks cooling-off periods for lobbyists who seek to transition into the public sector (Chilean Transparency Council, 2019[10]).

Several proposals for legal and regulatory reforms of the lobbying framework have been brought forward by various stakeholders, including lobbyists, think tanks, civil society organisations, researchers and academics, parliamentarians, as well as government bodies such as the Transparency Council, and the Presidential Advisory Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency (Comisión Asesora Presidencial para la Integridad Pública y Transparencia de Chile – hereafter “the Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency”) under the Ministry General Secretariat of the Presidency (Ministerio Secretaría General de la Presidencia – SEGPRES) (Chilean Transparency Council, 2019[10]; Palomino Díaz, 2022[11]). Recognising the challenges with the implementation of the current lobbying framework, the Commission for Integrity and Transparency has proposed several changes to the legal framework and identified the modernisation of the Lobbying Act as one of the priority areas of the National Public Integrity Strategy (Estrategia Nacional de Integridad Pública – ENIP) (Presidential Advisory Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency of Chile, 2023[9]).

Most recently, the scandal involving the foundation “Democracia Viva”, which led to the launch of an investigation into influence peddling, fraud against the Treasury and embezzlement of public funds, has further shown the need to strengthen transparency on the lobbying and influence activities of those who influence public decisions, including civil society organisations, and to strengthen rules of transparency and integrity for those of them who engage in political activities. The special Ministerial Advisory Commission for the regulation of the relationship between private non-profit institutions and the State (Comisión Asesora Ministerial para la regulación de la relación entre las instituciones privadas sin fines de lucro y el Estado), which was set up by the Government of Chile in 2023 in response to the scandal, recommended in its conclusions a reform of the lobbying framework as well as increased transparency on the sources of funding of not-for-profit organisations (Presidential Advisory Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency of Chile, 2023[7]).

Therefore, to maximise the benefits of inputs into policymaking, while safeguarding public decision-making processes from risks of undue influence, Chile could reform its lobbying framework along the following priorities:

Strengthening the legal framework for transparency in lobbying (Chapter 2).

Enabling effective transparency on lobbying through efficient disclosure and online transparency portals (Chapter 3).

Strengthening the integrity framework adapted to the risks of lobbying and influence activities for both public officials and lobbyists (Chapter 4).

Establishing mechanisms for effective implementation, compliance and review of the lobbying framework (Chapter 5).

Recommendations in this report have a specific focus on the Lobbying Act. While the broader framework for transparency and integrity in decision-making is outside the scope of this report, selected reforms of other bodies of laws and regulations – such as rules related to political finance – that could be amended to strengthen the overall lobbying and influence framework in Chile, are also included in the analysis. Lastly, recommendations also take into account the evolving lobbying and influence landscape, with particularly new and more diverse mechanisms and channels of influence, such as through social media (OECD, 2021[3]).

References

[4] Bertelsmann Stiftung (2024), BTI 2024 Country Report — Chile, https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-report/CHL.

[10] Chilean Transparency Council (2019), Perfeccionamientos a la Ley de Lobby, https://www.consejotransparencia.cl/wp-content/uploads/estudios/2019/05/Perfeccionamientos-a-la-Ley-del-Lobby-CPLT.pdf.

[5] Corporación Latinobarómetro (2021), Latinobarómetro 2020, https://www.latinobarometro.org/.

[3] OECD (2021), Lobbying in the 21st Century: Transparency, Integrity and Access, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c6d8eff8-en.

[8] OECD (2017), Chile Scan Report on the Citizen Participation in the Constitutional Process, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/public-governance-review-chile-2017.pdf.

[2] OECD (2017), Preventing Policy Capture: Integrity in Public Decision Making, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264065239-en.

[1] OECD (2010), “Recommendation of the Council on Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying and Influence”, OECD Legal Instruments, OECD/LEGAL/0379, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0379.

[11] Palomino Díaz, Á. (2022), “Reforma a la Ley Nº 20.730. Propuestas para une nueva regulación del lobby en Chile”, Revista Chilena de la Administración del Estado, Vol. 8, https://doi.org/10.57211/revista.v8i8.141.

[7] Presidential Advisory Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency of Chile (2023), Comisión Asesora Ministerial para la regulación de la relación entre las instituciones privadas sin fines de lucro y el Estado. Informe, https://www.integridadytransparencia.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Informe-Comision-Asesora.pdf.

[9] Presidential Advisory Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency of Chile (2023), National Public Integrity Strategy, https://www.integridadytransparencia.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Estrategia-Nacional-de-Integridad-Publica-2.pdf.

[6] Reuters Institute for the study of journalism (2022), “Chile Report 2022”, Reuters Institute for the study of journalism, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2022/chile.