This chapter discusses the steps that Chile must take to ensure there is an oversight function on lobbying and influence activities with the capacity to enforce policies and regulations and monitor and promote their implementation. First, the chapter provides recommendations to assign clear responsibilities to an independent body with broader responsibilities for verifying information disclosed, investigating potential breaches and enforcing the Lobbying Act. The chapter also discusses ways to safeguard those that report violations of the policies and rules on lobbying and influence activities, and applying a gradual system of financial and non-financial sanctions for breaches of the Lobbying Act. Lastly, the chapter provides recommendations for the regular review of the lobbying framework in Chile, in order to best meet stakeholder expectations and developments in lobbying.

The Regulation of Lobbying and Influence in Chile

5. Establishing mechanisms for effective implementation, compliance and review of the lobbying framework in Chile

Abstract

5.1. Introduction

Transparency and integrity objectives cannot be achieved if disclosure and ethical requirements are not respected by the actors concerned and properly implemented by the relevant supervisory bodies (OECD, 2010[1]). To that end, oversight functions are an essential feature to ensure an effective lobbying regulation. The oversight function refers to an independent public institution or institutions, dedicated or with broader competencies, adequately resourced and empowered to investigate and enforce policies and regulations concerning lobbying and influence activities, and monitor and promote their implementation.

All countries with a mandatory register on lobbying activities – including Chile – have an institution or function responsible for monitoring compliance. While the responsibilities of such bodies vary widely among OECD member and partner countries, four broad functions exist: 1) enforcement; 2) monitoring; 3) promotion of the law; and 4) review of the law.

In Chile, various institutions make up the institutional framework on lobbying, from the day-to-day administration of the registers to conducting investigations and applying sanctions (Table 5.1). While it is not necessarily recommended to have a unique oversight body to conduct all the activities mentioned in the table below, the absence of a body representing the law in Chile – i.e., a body with competences to administer the registers for all passive subjects, centralise lobbying information into a single transparency portal, verify the accuracy and completeness of the registrations, and conduct investigations – has emerged as a major challenge.

Table 5.1. Institutional responsibilities for the implementation of the Lobbying Act in Chile

|

Day-to-day administration of the registers, guidance and training |

Transparency portal and data visualisation of lobbying information |

Monitoring and verification of lobbying disclosures |

Investigations of potential breaches and application of sanctions |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Transparency Council |

None |

|

Source: author’s contribution, based on the Lobbying Act

Similarly, the sanction regime detailed in Section III of the Lobbying Act currently lacks teeth on several fronts: the sanction regime is currently focused on passive subjects (public authorities and civil servants), with no designated authority that could apply sanctions to lobbyists in case of breaches to the law, and the sanctions applied do not have a deterrent effect as they mostly rely on administrative liability (Table 5.2). In addition, the Comptroller General of the Republic pointed out that some of the sanctions proposed for passive subjects are not applied. Information transmitted by the Comptroller General of the Republic to the Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency shows that between 2018 and 2022, only 22 summary proceedings have been filed for violation of the Lobbying Law, with only 10 completed as of December 2023, and no information available as to whether a sanction was applied (Presidential Advisory Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency of Chile, 2023[2]).

Table 5.2. Sanctions for public authorities and passive subjects in the Lobbying Act

|

Investigating and sanctioning authority |

Procedure |

Breaches and fines |

Name and shame |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Passive subjects referred to in Article 3, Article 4 §2, §4 and §7, the regional councillors and the executive secretary of the regional council referred to in Article 4 §1 [Article 15 & 16 of the Lobbying Act] |

Office of the Comptroller General of the Republic *In the event that the person liable for the penalty is the head of service or authority, the power to impose the penalty shall lie with the authority that appointed him/her |

The Office of the Comptroller General of the Republic must inform the official of a possible violation, who has 20 days respond. Sanctions are proposed by the Comptroller General but applied by the head of service in which the public official is employed. |

Failing to record information on time: fine of 10 to 30 monthly tax units. Inexcusable omission or knowingly disclosing inaccurate or false information: fine of 20 to 50 monthly tax units. |

The names of the person or persons sanctioned shall be published on the websites of the respective body or service for a period of one month from the date on which the decision establishing the sanction becomes final. |

|

Mayors, councillors, directors of municipal works and municipal secretaries (Article 4 §1) [Article 17 of the Lobbying Act] |

Office of the Comptroller General of the Republic |

The Office of the Comptroller General of the Republic must inform the official of a possible violation, who has 20 days respond. Sanctions are proposed by the Comptroller General but applied by the head of service in which the public official is employed. |

Failing to record information on time: fine of 10 to 30 monthly tax units. Inexcusable omission or knowingly disclosing inaccurate or false information: fine of 20 to 50 monthly tax units. |

Once the sanction applied has been enforced, the competent body shall notify the municipal council at its next session. Likewise, this sanction shall be included in the public account referred to in Article 67 of Law No. 18.695 and shall be included in the extract of the same, which must be disseminated to the community. |

|

Comptroller General of the Republic (Article 4 §2) [Article 15 & 16 of the Lobbying Act] |

Parliamentary Ethics and Transparency Committee of the Chamber of Deputies |

The Chamber of Deputies is responsible for verifying due compliance with the provisions of the Act. |

Failing to record information on time: fine of 10 to 30 monthly tax units. Inexcusable omission or knowingly disclosing inaccurate or false information: fine of 20 to 50 monthly tax units. |

The names of the person or persons sanctioned shall be published on the websites of the respective body or service for a period of one month from the date on which the decision establishing the sanction becomes final. |

|

National Congress (passive subjects referred to in Article 4 §5) [Article 19 of the Lobbying Act] |

Parliamentary Ethics and Transparency Committees |

The procedure may be initiated ex officio by the Committees or on the basis of a complaint by any interested party. The passive subject has the right to reply within 20 days. |

Failing to record information on time: fine of 10 to 30 monthly tax units deducted directly from their remuneration or allowance. Inexcusable omission or knowingly disclosing inaccurate or false information: a fine of 20 to 50 monthly tax units. |

The names of the sanctioned person or persons shall be published on the website of the respective Chamber for a period of one month after the decision establishing the sanction has become final. |

|

Central Bank (passive subjects referred to in Article 4 §3) [Article 20 of the Lobbying Act] |

Council of the Central Bank |

The Bank's minister of faith shall bring the respective background information to the attention of the Board, so that the relevant proceedings may be initiated, and the affected party shall be notified of this circumstance, who shall have the right to reply within 10 working days. |

Failing to record information on time: fine of 10 to 30 monthly tax units. Inexcusable omission or knowingly disclosing inaccurate or false information: sanctions in accordance with the constitutional organic law of the Central Bank. |

The names of the sanctioned person or persons shall be published on the Central Bank's website for a period of one month after the decision establishing the sanction has become final. |

|

Public Prosecutor's Office (passive subjects referred to in Article 4 §6) [Article 21 of the Lobbying Act] |

National Public Prosecutor *If the person who fails to comply with or commits the offences referred to above is the National Public Prosecutor, the provisions of Article 59 of Law No. 19.640 shall apply. |

The procedure may be initiated ex officio by the appropriate hierarchical superior or upon complaint by any interested party. The passive subject has a right to reply within 20 days. |

Failing to record information on time: fine of 10 to 30 monthly tax units. Inexcusable omission or knowingly disclosing inaccurate or false information: a fine of 20 to 50 monthly tax units. |

The names of the sanctioned person or persons shall be published on the websites of the respective Public Prosecutor's Office for a period of one month after the decision establishing the sanction has become final. |

|

Director of the Administrative Corporation of the Judiciary (Article 4 §8) [Article 22 of the Lobbying Act] |

Superior Council |

The procedure may be initiated ex officio by the High Council or upon complaint by any interested party. The affected party shall be notified of this circumstance, who shall have the right to reply within 20 days. |

Failing to record information on time: Fine of 10 to 30 monthly tax units. Inexcusable omission or knowingly disclosing inaccurate or false information: Fine of 20 to 50 monthly tax units. |

/ |

Source: author’s contribution, based on the Lobbying Act

To further strengthen the oversight and enforcement of the Lobbying Act in Chile, this chapter provides recommendations on the following three core themes:

Assigning clearer responsibilities for implementation and enforcement.

Strengthening the sanctions regime.

Enabling an effective review of the lobbying framework.

5.2. Assigning clear responsibilities for implementation and enforcement

5.2.1. An independent body could be entrusted with broader responsibilities for verifying information disclosed, investigating potential breaches and enforcing the Act

To strengthen the oversight and enforcement of the Act, it is crucial that the Lobbying Act further clarifies responsibilities for compliance and enforcement activities. In particular, and to align with OECD standards in this area, oversight functions should ensure impartial enforcement. At the OECD level, all countries with a transparency register on lobbying activities have one or several institutions responsible for monitoring compliance, including Chile (Table 5.3). Some countries have chosen to entrust implementation, monitoring and enforcement to a single dedicated institution (the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying in Canada, the Office of the Registrar of Consultant Lobbyists in the United Kingdom). It is also not uncommon to assign the oversight body responsible for integrity standards in the public sector with responsibilities for lobbying (e.g., the High Authority for Transparency in Public Life in France, the Chief Official Ethics Commission in Lithuania). While the institutional set-up varies greatly among OECD countries, most of these bodies or functions monitor compliance with disclosure obligations and whether the information submitted is accurate, presented in a timely fashion and complete (OECD, 2021[3]).

Table 5.3. Oversight function for lobbying activities in selected OECD countries

|

Authority |

Main missions and enforcement powers |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Australia |

Attorney-General’s Department |

|

|

Canada |

Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying |

|

|

France |

High Authority for Transparency in Public Life (HATVP) |

|

|

Germany |

President of the Bundestag |

|

|

Iceland |

Prime Minister’s Office |

|

|

Ireland |

Standards in Public Office Commission |

|

|

Lithuania |

Chief Official Ethics Commission |

|

|

Slovenia |

Commission for the Prevention of Corruption |

|

|

United Kingdom |

Office of the Registrar of Consultant Lobbyists |

|

|

United States |

Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives |

|

|

Secretary of the Senate |

||

|

Government Accountability Office |

|

|

|

United States Attorney for the District of Columbia |

|

|

|

EU |

Transparency Register Joint Secretariat |

|

Fuente: Encuesta OCDE 2020 sobre lobby e investigación adicional de la Secretaría de la OCDE

In Chile, previous reform proposals included assigning responsibilities for supervising the requirements for active subjects, and applying relevant sanctions to active subjects, to the Council for Transparency or the Financial Market Commission. However, this would further complexify the existing system. Faced with this dilemma, two solutions could be envisioned:

Entrust broad responsibilities for the implementation of the Lobbying Act to the Transparency Council. Several stakeholders consulted for this report mentioned that the Transparency Council would be the best placed institution, although this would require a modification of the Transparency Law and a constitutional reform to extend its scope of competence over autonomous bodies and the National Congress.

Amend the legal framework to institutionalise the Presidential Advisory Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency, with a sufficient level of independence and the necessary powers to implement the Lobbying Act over all the public authorities covered in Articles 3 and 4. These powers would include verifying information disclosed by public officials (“public agenda registers”) and active subjects (“register of lobbyists”), conducting investigations when necessary, requesting active subjects to update information in case of non-compliance, proposing or imposing financial (fines) and administrative sanctions (suspension or removal from the register) and, if necessary, referring the most serious cases to the judiciary for civil and criminal prosecution, and providing advice and training for active and passive subjects.

Regarding the latter, and as stated above, it is not uncommon to assign the oversight body responsible for integrity standards with responsibilities such as implementing and enforcing lobbying regulations. For example, in Ireland, the Standards in Public Office Commission oversees the administration of legislation in four distinct areas, including the Ethics in Public Office Act, which sets out standards for elected and appointed public officials, and the Regulation of Lobbying Act, which regulates lobbying for elected and appointed public officials, as well as officials in the civil service. In particular, the Commission manages the register of lobbying, ensures compliance with the Act, provides guidance and assistance, and investigates and prosecutes offences under the Act (OECD, 2021[3]).

5.2.2. The Lobbying Act could further clarify the types of verification activities conducted and the investigative powers entrusted to the oversight entity(ies)

In Chile, there are no verification mechanisms established in the legal framework. This means that the accuracy and completeness of the information disclosed is not verified. The Lobbying Act could therefore clarify the types of verification activities conducted and the investigative powers entrusted to the chosen oversight entity(ies). Verification activities include for example verifying compliance with disclosure obligations (i.e., existence of declarations, delays, unregistered lobbyists), as well as verifying the accuracy and completeness of the information declared in the declarations. Investigative processes and tools include:

random review of registrations and information disclosed or review of all registrations and information disclosed

verification of public complaints and reports of misconducts

inspections (off-side and/or on-site controls may be performed)

inquiries (requests for further information)

hearings with other stakeholders.

In Canada for example, the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying can verify the information contained in any return or other document submitted to the Commissioner under the Act, and conduct an investigation if he or she has reason to believe, including on the basis of information received from a member of the Senate or the House of Commons, that an investigation is necessary to ensure compliance with the Lobbyists’ Code of Conduct or the Lobbying Act. This allows the Commissioner to conduct targeted verifications in sectors considered to be at higher risk or during particular periods. The Commissioner can ask present and former designed public officials to confirm the accuracy and completeness of lobbying disclosures by lobbyists, summon and enforce the attendance of persons before the Commissioner, and compel them to give oral or written evidence on oath, as well as compel persons to produce any document or other things that the Commissioner considers relevant for the investigation. The Irish Standards in Public Office Commission, on the other hand, reviews all registrations to make sure that all who are required to register have done so and that they have registered correctly (OECD, 2021[3]).

5.2.3. The government of Chile could introduce an anonymous reporting mechanism for those who suspect violations of the Lobbying Act, and consider including in the appropriate legislation violations of the Lobbying Act in the scope of wrongdoings whose disclosure benefits from whistle-blower protection

The lack of oversight in the current system has a negative impact on the willingness to comply with the law. Stakeholders interviewed for this report highlighted that the only effective way to uncover “shadow lobbying” would be a system of rules and procedures for reporting suspected violations of the policies and rules on lobbying activities, and ensuring the protection in law and practice against all types of retaliation as a result of reporting in good faith and on reasonable grounds.

In Chile, rules on the protection of whistleblowers were first introduced in Law 18.334 on the Administrative Statute (consolidated with the adoption on 16 March, 2005 of a Decree with force of law issued by the Ministry of Finance – DFL 29), Law 18.575 or General Law of Bases (Ley General de Bases) and Law 18.883 on the Administrative Statute for Municipal Officials, which were modified with the adoption in 2007 of Law No. 20.205 on the protection of civil servants who report irregularities and breaches to the principle of probity. Under this law, all civil servants are required to report crimes, simple offences or irregularities, and whistleblowers granted the right to be defended. While the framework provided by this Law was a step forward, its implementation was however limited. The recent Law No. 21.592, adopted in August 2023, establishes a statute of protection in favour of complainants of acts against administrative probity. This law also establishes incentives and effective protections for civil servants who report irregularities; in particular, Article 3 of the Law establishes a Complaints Channels administered by the Office of the Comptroller General enabling the report of “facts constituting disciplinary infractions or administrative misconduct, including, among others, facts constituting corruption, or that affect, or may affect, public assets or resources, in which personnel of the State Administration or an agency of the State Administration may participate”. However, the Law does not clearly specify whether violations of the Lobbying Act are included the scope of wrongdoings whose disclosure benefits from whistle-blower protection.

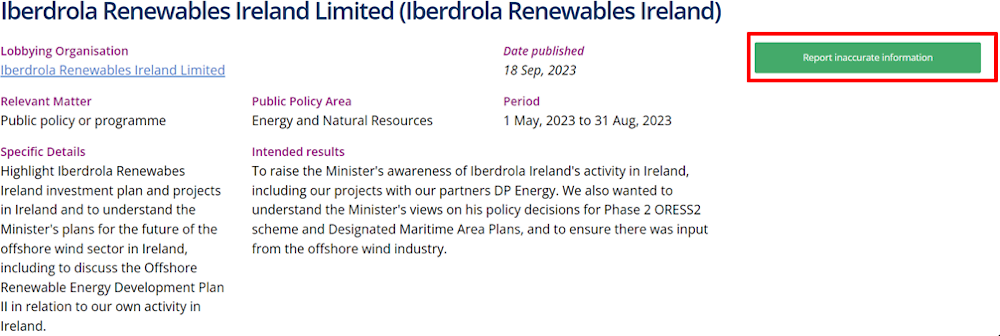

Another option would be to allow anonymous complaints to be made directly into the registry by any person. This solution exists, for example, in Ireland: each page containing information on the lobbying activities of an active subject contains the possibility to click directly in the register on a “report inaccurate information” button that allows false information to be reported (Figure 5.1). In doing so, individuals who witness or are aware of violations of the lobbying and influence-related rules and standards, could feel free to come forward to the relevant authorities to disclose the wrongdoing.

Figure 5.1. Reporting inaccurate information in the Irish Lobbying Registry

5.3. Strengthening the sanctions regime

5.3.1. The Lobbying Act could include a gradual system of financial and non-financial sanctions for active subjects, applied at the entity level

Sanctions should be an inherent part of the enforcement and compliance setup and should first serve as a deterrent and second as a last resort solution in case of a breach of the lobbying regulation. Article 8 §1 of the Lobbying Act specifies that anyone who, when requesting a meeting or hearing, inexcusably omits the information that is necessary for disclosing meetings or hearings, or knowingly provides inaccurate or false information on such matters, shall be punished with a fine of between ten and fifty monthly tax units, without prejudice to any other penalties that may apply. However, the Act does not specify which authority is responsible for investigating such matters or applying fines.

As a first step, and if active subjects face disclosure requirements in a Register of Lobbyists, the Lobbying Act will need to strengthen the types of breaches from active subjects that could lead to sanctions. Sanctions for lobbyists usually cover the following types of breaches:

not registering and/or conducting activities without registering

not disclosing the information required or disclosing inaccurate or misleading information

failing to update the information or file activity reports on time

failing to answer questions (or providing inaccurate information in response to these questions) or not co-operating during an investigation by the oversight authority

breaching integrity standards / lobbying codes of conduct.

Sanctions should be objective, proportionate, timely and dissuasive. The practice from OECD countries has also shown that a graduated system of administrative sanctions appears to be preferable, such as warnings or reprimands, fines, debarment and temporary or permanent suspension from the Register and prohibition to exercise lobbying activities. A few countries have criminal provisions leading to imprisonment, such as Canada, France, Ireland, Peru, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Most importantly, sanctions for lobbyists could be applied at the entity level instead of individual lobbyists. This introduces the clear responsibility of entities towards the people they employ and their managers. It can also encourage entities to adopt internal compliance rules, thereby raising the degree of professionalism with which lobbying activities should be carried out.

5.3.2. The Lobbying Act could include provisions that enable the oversight entity(ies) to send formal notices and apply administrative fines to incentivise compliance

OECD practice shows that regular communication with lobbyists and public officials on potential breaches appears to encourage compliance without the need to resort to enforcement, and helps to create a common understanding of expected disclosure requirements. These notifications can include for example formal notices sent to potential un-registered lobbyists, requests for modifications of information declared in case of minor breaches, or formal notices sent to a lobbyist or a public official to advise of a potential breach (Box 5.1).

Box 5.1. Formal notices to encourage compliance in France

When the High Authority for transparency in public life finds, on its own initiative or following a public complaint, a breach of reporting or ethical rules, it sends the interest representative concerned a formal notice, which it may make public, to comply with the obligations to which he or she is subject, after giving him or her the opportunity to present observations.

After a formal notice, and during the following three years, any further breach of reporting or ethical obligations is punishable by one year's imprisonment and a fine of EUR 15 000.

Administrative monetary penalties also help to promote compliance and resolve cases of late submission or failure to register. Since the entry into force of the Lobbying Act in Ireland, the Standards in Public Office Commission has focused on encouraging compliance with the legislation through interactions with lobbyists to resolve any cases of non-compliance, including the issuance of fines for late reporting, before proceeding with further sanctions. The Commission concluded that increased communication and outreach to lobbyists early in the process reduced the number of cases involved in legal proceedings (Box 5.2). The majority of lobbyists comply with their obligations when contacted by the investigation unit.

Box 5.2. Financial penalties imposed by the Standards in Public Office Commission in Ireland

Part 4 of the Irish Regulation of Lobbying Act 2015 on enforcement provisions gives the Standards in Public Office Commission the authority to conduct investigations into possible contraventions to the Act, prosecute offences and issue fixed payment notices (FPN) of EUR 200 for late filing of lobbying returns.

The Commission reviews all registrations to ensure that all persons who are required to register have done so and that they have registered correctly. The Commission can also request, by providing notice to a given registrant, further or corrected information when it considers that an application is incomplete, inaccurate or misleading.

The Commission established a separate Complaints and Investigations Unit to manage investigations and prosecutions, and put in place procedures for investigating non-compliance in relation to unreported lobbying by both registered and non-registered persons, as well as non-compliance related to non-returns and late returns of lobbying activity:

Unregistered lobbying activity is monitored via open-source intelligence such as media articles, from the Register itself, or from complaints or other information received by the Commission;

Late returns by registered persons are monitored on the basis of information extracted from the lobbying register relating to the number of late returns and non-returns after each return deadline. The online register is designed to ensure that fixed payment notices are automatically issued to any person submitting a late return on lobbying activities. If the payment is not paid by the specified date, the Commission prosecutes the offence of submitting a late return.

As observed in Commission annual reports, in most cases, compliance was achieved after receipt of the notice. In 2017, there were neither convictions nor investigations concluded, as this was the first year in which enforcement provisions were in effect. In 2018, 26 investigations were launched to gather evidence in relation to possible unreported or unregistered lobbying activity, of which 13 were discontinued (in part due to the person subsequently coming into compliance with the Act).

The Commission noted that the FPNs issued in respect of the three relevant periods of 2018 (270) were significantly lower than in 2017 (619), signalling a marked improvement in compliance with the deadlines.

Source: (OECD, 2021[3]).

5.4. Enabling an effective review of the lobbying framework

5.4.1. The Lobbying Act could include a periodic review mechanism to address new developments in lobbying

The regular review of established lobbying rules and guidelines, and how they are implemented and enforced, helps to strengthen the overall framework on lobbying and to improve compliance. This helps to identify strengths, but also gaps and implementation failures that need to be addressed to meet evolving public expectations for transparency in decision-making processes and to ensure that regulation takes into account the multiple ways in which interests can influence policymaking processes. From this perspective, it is important that any law or regulation on lobbying includes a mechanism for periodic review.

As such, the regular review of the Lobbying Act could be embedded in the legal framework and entrusted to the Ministry in charge of the Act – in this case SEGPRES. The example of Ireland is provided in Box 5.3.

Box 5.3. Review of the Lobbying Act in Ireland

Section 2 of the Lobbying Act provides for regular reviews of the operations of the Act. The first review of the Act took place in 2016. The report takes into account inputs received by key stakeholders, including persons carrying out lobbying activities and the bodies representing them. No recommendations were made by the government for amendments of the Lobbying Act. Subsequent reviews must take place every three years.

The first report found a high level of compliance with legislative requirements. Lobbyists highlighted the need for further education, guidance and assistance, which led the Standards in Public Office Commission to review its communication activities and guidance to lobbyists.

In its submission to the first review of the operation of the Act, the Commission recommended that any breaches of the cooling-off statutory provisions should be an offence under the Act. It also pointed to the lack of power to enforce the Act’s post-employment provisions or to impose sanctions for persons who fail to comply with these provisions.

The Code of Conduct for persons carrying out lobbying activities, which came into effect on 1 January 2019, is also reviewed every three years.

Source: (OECD, 2021[3]).

5.4.2. To improve compliance and the perception of lobbying among citizens, the government of Chile could further promote stakeholder participation in the discussion, implementation and subsequent revisions of lobbying-related regulations and standards of conduct

OECD practice shows that involving relevant stakeholders in the revision process of lobbying-related rules and guidelines is key to create ownership and ensure a common understanding of the requirements and expected behaviours for both lobbyists and public officials. As such, the Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency is encouraged to continue involving stakeholders and citizens not only throughout the revision process of the current Lobbying Act, but also in its implementation and subsequent revisions (including, for example, the drafting and revision of codes of conducts or guidelines). Following the examples of Ireland and Canada, this could include regular consultations on the content of regulations (Box 5.4).

Box 5.4. Consultations on the drafting and revision processes of lobbying regulations in Ireland and Canada

Supporting a cultural shift towards the regulation of lobbying in Ireland through public consultation

In Ireland, the Standards in Public Office Commission established an advisory group of stakeholders in both the public and private sectors to help ensure effective planning and implementation of the Regulation of Lobbying Act. This forum has served to inform communications, information products and the development of the online registry itself.

Consultation on future changes to the Lobbyists’ Code of Conduct in Canada

In Canada, the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying launched a series of consultations in 2021 and 2022 to collect views on improving and clarifying the standards of conduct for lobbyists to update the Lobbyists’ Code of Conduct.

An initial consultation was held in late 2020 to obtain the views and perspectives of stakeholders in relation to the existing Lobbyists’ Code of Conduct. A second consultation (Dec. 15, 2021 to Feb. 18, 2022) aimed to collect views on a preliminary draft of the revised Code. A final and third consultation on changes to the Code was conducted in May- June 2022. The new Code was published in the Canada Gazette and came into force on July 1, 2023.

Proposals for action

In order to strengthen established mechanisms for effective implementation, compliance and review of the lobbying framework in Chile, and to be as consistent as possible with OECD standards and international best practices in this area, the OECD recommends that the Government of Chile considers the following proposals.

Assign clear responsibilities for implementation and enforcement

Entrust an independent body with broader responsibilities for verifying information disclosed, investigating potential breaches and enforcing the Act. This independent body could be the Council of Transparency or an institutionalised Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency, with a sufficient level of independence and the necessary powers to implement the Act over all the public authorities covered in Articles 3 and 4.

Include in the Lobbying Act provisions specifying the monitoring and verification activities entrusted to the oversight entity(ies), as well as its (their) investigative powers.

Introduce an anonymous reporting mechanism for those who suspect violations of the Lobbying Act.

Strengthen the sanctions regime

Establish a gradual system of financial and non-financial sanctions (including administrative and criminal sanctions) for active subjects, applied at the entity level, such as warnings or reprimands, fines, debarment and temporary or permanent suspension from the Register and prohibition to exercise lobbying activities.

Amend the Lobbying Act to enable the oversight entity(ies) to send formal notices and apply administrative fines to both public officials and lobbyists to incentivise compliance.

Enable an effective review of the lobbying framework

Include in the Lobbying Act a periodic review mechanism to address new developments in lobbying.

Promote stakeholder participation in the discussion, implementation and subsequent revisions of lobbying-related regulations and standards of conduct.

References

[3] OECD (2021), Lobbying in the 21st Century: Transparency, Integrity and Access, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c6d8eff8-en.

[1] OECD (2010), “Recommendation of the Council on Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying and Influence”, OECD Legal Instruments, OECD/LEGAL/0379, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0379.

[4] Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying (2023), Lobbyists’ Code of Conduct published in the Canada Gazette, takes effect July 1, 2023, https://lobbycanada.gc.ca/en/news/Lobbyists-Code-of-Conduct-published-in-the-Canada-Gazette-takes-effect-July-1-2023.

[2] Presidential Advisory Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency of Chile (2023), National Public Integrity Strategy, https://www.integridadytransparencia.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Estrategia-Nacional-de-Integridad-Publica-2.pdf.