The report provides empirical evidence about the misuse of container ships in international trade in counterfeits. It also suggests the main routes of trade with containers polluted with illicit trade. Finally, the report also outlines the economic landscape for containerized maritime transport and investigates policy gaps that enable its misuse by criminals in illicit trade.

Misuse of Containerized Maritime Shipping in the Global Trade of Counterfeits

Abstract

Executive Summary

Trade in counterfeit goods represents a longstanding, and growing, worldwide socio-economic risk that threatens effective public governance, efficient business and the well-being of consumers. At the same time, it is becoming a major source of income for organised criminal groups. It also damages economic growth by undermining both business’s revenue and their incentive to innovate.

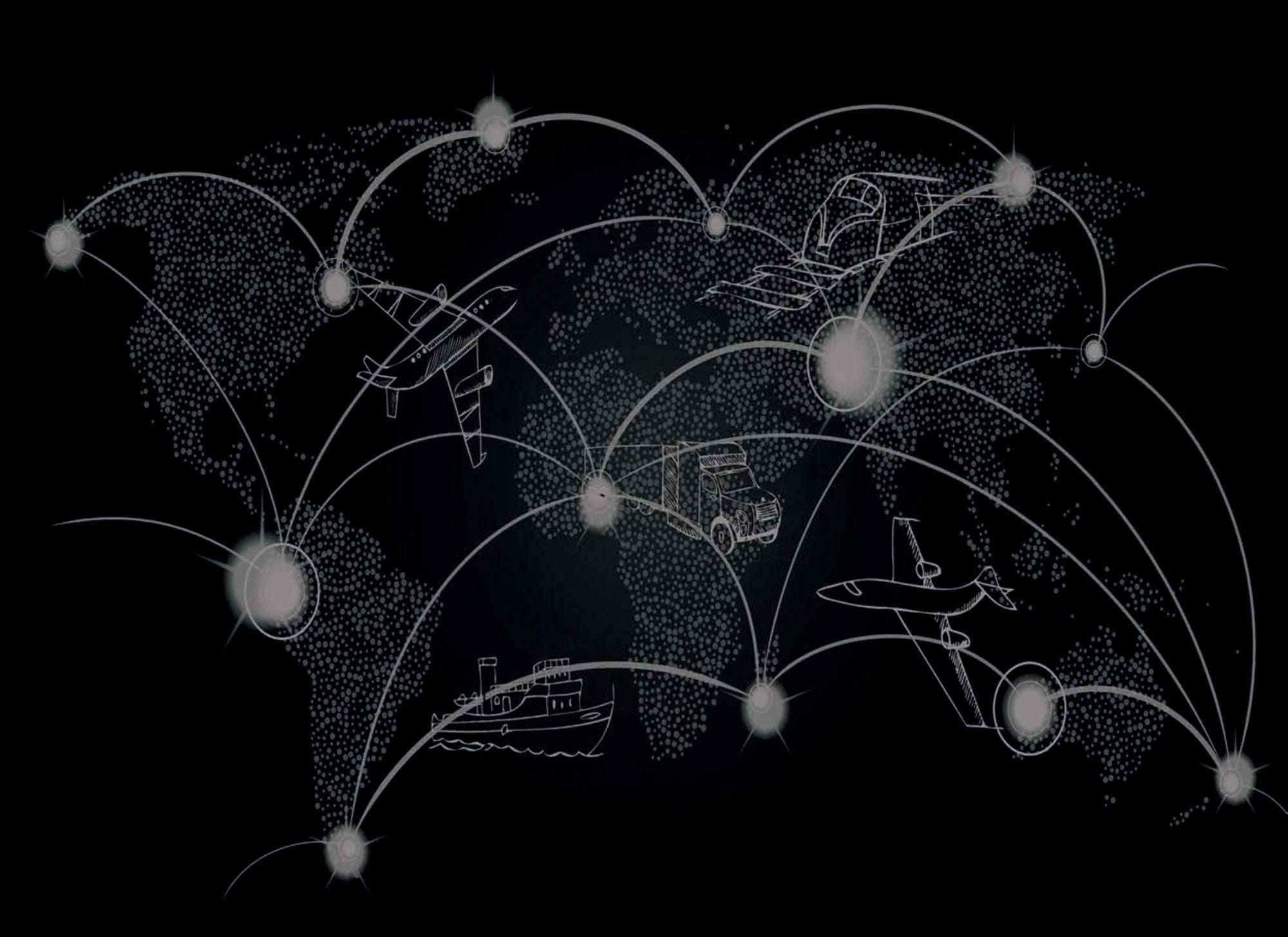

Counterfeit and pirated products tend to be shipped by virtually every means of transport. In terms of number of seizures, trafficking of fakes via small parcels is growing and becoming a significant problem in terms of enforcement; however, in terms of value, counterfeits transported by container ship clearly dominate.

Over the past decades, containers have become the universal means to aggregate goods into standardised, uniform cargo. The introduction of containers was a revolutionary change for transport that offered new logistical possibilities, boosted efficiency and greatly reduced the overall cost of international trade. At the same time, smugglers found it appealing, given the ease and low risk of stowing not only counterfeit products, but also narcotics and other types of contraband, and even undocumented migrants in the containers.

Available data confirm the high intensity of misuse of containerised maritime transport by counterfeiters. The analysis in this report uses two sorts of data. The first is information on trade in counterfeit goods, which is based on customs data regarding seizures of counterfeit goods obtained from the World Customs Organization, the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union and from the US Customs and Border Protection Agency (CBP). The second includes data on trade with container ships from the OECD International Transport Forum (ITF) database, Eurostat Comext, and indices on containerised maritime transport developed by UNCTAD (United Nations Conference of Trade and Development).

A review of the data showed that, while the highest number of customs seizures of counterfeit and pirated products were from postal parcels, sea transport accounted for the most seized value. In 2016, containerships carried 56% of the total value of seized counterfeits.

The highest number of counterfeit shipments originated in South East Asia, including China and Hong Kong (China), India, Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore; while Mexico, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates also remain among the top provenance economies for counterfeit and pirated goods traded worldwide during the considered period.

Additional analysis carried out for the European Union showed that over half of containers transported in 2016 by ships from economies known to be major sources of counterfeits entered the EU through Germany, the Netherlands and United Kingdom. There are also some EU countries, such as Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece and Romania, with relatively low volumes of containers trade in general, but with a high level of imports from counterfeiting-intense economies.

Ongoing and planned infrastructure developments in the EU could significantly change the patterns of imports of fake goods through containers. The Chinese Belt and Road Initiative is of particular relevance in this context, as it could result in a substantial growth of fakes entering the European Union in container ships through ports in the Mediterranean region.

To combat illicit trade, a number of risk-assessment and targeting methods have been adapted for containerised shipping, in particular to target illicit trade in narcotics and hazardous and prohibited goods. However, it appears that the illicit trade in counterfeits has not been a high priority for customs, as shipments of counterfeits are commonly perceived as “commercial trade infractions” rather than criminal activity. Consequently, existing enforcement efforts may not be adequately tailored to respond to this risk.

Some efforts have been made by the industry to enhance co-ordination to counter the threat of illicit trade in maritime transport. A good example is the “declaration of intent”, in which well-known brand owners, vessel operators and freight forwarders worked together to develop voluntary guidelines to raise awareness of the importance of gathering sufficient information on the parties using their shipping services. It appears that there is considerable scope for improvement in this regard.