Disinformation and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine: Threats and governance responses

Introduction1

Systematic information manipulation and disinformation have been applied by the Russian government as an operational tool in its assault on Ukraine (Council of the European Union, 2022[1]). The spread of disinformation by the Russian government and aligned actors, as well as the actions taken in response by the Government of Ukraine, allied governments and international organisations, provide an important perspective and lessons on how to counteract false and misleading content.

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine is notable for the extent to which it is being waged and shared online. While social media have played a role in previous wars – for example, Russian soldiers were identified on the battlefield in the Donbas region during the 2014 invasion and videos from the war in Syria were shared on TikTok – Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has illustrated how social media is changing the way war can be chronicled, experienced and understood (The Economist, 2022[2]). This is largely due to the rapid rise in internet coverage and the use of social media; 75% of Ukrainians use the internet, and 89% of the population is covered by at least 3G mobile technology (International Telecommunication Union, 2021[3]). In comparison, when the Russian Federation (hereafter “Russia”) invaded Ukraine in 2014, just 4% of Ukrainian mobile subscribers had access to 3G networks or faster, and during the war in Syria in 2015, only 30% of the Syrian population was online (The Economist, 2022[2]). Thanks in part to this dynamic, the ongoing war in Ukraine has also clarified the extent of the disinformation threat. Although the use of disinformation as a weapon has always existed, the social media landscape has multiplied its reach and potential penetration.

The disinformation surrounding Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 marked an escalation in Russia’s longstanding information operations against Ukraine and open democracies. Matched by increased restrictions on political opposition in Russia, disinformation narratives progressed from propaganda and historical revisionism – for example, insisting that Crimea had “always been Russian” after Moscow’s annexation in 2014 (Coynash, 2021[4]; Chotiner, 2022[5]) – to false claims about neo-Nazi infiltration in Ukraine’s government and conspiracy theories about Ukraine/US bioweapons laboratories. These efforts represent a handful of the ways in which the Russian government and aligned actors use disinformation as a weapon and to distract, confuse and subvert opponents.

The spread of disinformation around Russia’s invasion of Ukraine reflects wider challenges related to the shift in how information is produced and distributed. Platform and algorithm designs can amplify the spread of disinformation by facilitating the creation of echo chambers and confirmation bias mechanisms that segregate the news and information people see and interact with online; information overload, confusion and cognitive biases play into these trends (for additional discussion of these factors, see (Matasick, Alfonsi and Bellantoni, 2020[6])). A particular challenge is that people tend to spread falsehoods “farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth”; this is particularly the case for false political news (Vosoughi, Roy and and Aral, 2018[7]). For example, one study found that tweets containing false information were 70% more likely to be retweeted than accurate tweets (Brown, 2020[8]). Another study found that false information on Facebook attracts six times more engagement than factual posts (Edelson, 2021[9]). In addition, feedback loops between the platforms and traditional media can serve to further amplify disinformation, magnifying the risk that disinformation can be used to deliberately influence public conversations, as well as confuse and discourage the public.

The flow of – and disruption caused by – Russian disinformation has significantly increased since Russia's invasion in February 2022. In turn, Ukraine’s response to the Russian disinformation threat has built upon progress made in strengthening the information and media environment since 2014 and in establishing mechanisms to respond directly to information threats. These include efforts to provide accurate information, ensure that media organisations can continue operations, and policy efforts to combat the threats posed by Russian state-linked media.

Internationally, governments rapidly recognised the disinformation threat in the context of Russia’s large-scale aggression against Ukraine. In response, they have highlighted narratives and tools used by the Russian government, sanctioned media and personalities, and supported media environments domestically, as well as in Russia and Ukraine. International organisations similarly executed fact checking and debunking programmes, as well as provided cross-organisational mechanisms for information sharing and technical support. That said, lessons from government responses to the threat posed by disinformation during the first few months of the war will not necessarily represent what should be done in peace time due to the complicated and urgent circumstances brought on by the war. As Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine continues, striking the balance between countering disinformation while at the same time facilitating press freedom and a whole-of-society approach to strengthening information ecosystems and democracy will need to be considered.

The information threat from the Russian Federation

Russia’s disinformation campaigns purposefully confuse and undermine information environments. Their efforts seek to cause confusion, complicate efforts to reach consensus, and build support for Russia’s goals, while undermining the legitimacy of Ukraine’s response. While such efforts can pose the greatest risk in fragile democracies dealing with complicated historical, societal and economic issues, such as Ukraine, undermining the information space to this end has destructive implications for all democracies. Understanding how the Russian government controls media environments at home and the way mis- and disinformation is spread abroad is vital to counteract the threats posed to democracy and freedom of expression.

Disinformation tactics

Disinformation is the false, inaccurate, or misleading information deliberately created, presented and disseminated, whereas “mis-information” is false or inaccurate information that is shared unknowingly and is not disseminated with the intention of deceiving the public (Wardle and Derakshan, 2017[10]; Lesher, Pawelec and Desai, 2022[11]). Russian action fits squarely with the definition of disinformation. The Russian disinformation narratives are often false, or obscure facts with half-truths and “whataboutisms” (efforts to respond to an issue by comparing it to a different issue that does not engage with the original one). Russian actors employ a diverse strategy to introduce, amplify, and spread false and distorted narratives across the world. Its efforts rely on a mix of fake and artificial accounts, anonymous websites and official state media sources to distribute and amplify content that advances its interests and undermines competing narratives (Cadier et al., 2022[12]).

Russian propaganda and disinformation activities are produced in large volumes and are distributed across a large number of channels, both via online and traditional media. The producers and disseminators of this content include paid internet “trolls”, or people who post inflammatory, insincere, or manipulative messages via online chat rooms, discussion forums, and comments sections on news and other websites (Paul and Matthews, 2016[13]). Strategies have also included more targeted approaches. For example, in 2020, Facebook identified a Russian military operation targeting Ukraine that had created fake Facebook profiles who posed as journalists and who attempted to spread disinformation in a way that appeared to be more credible (Facebook, 2021[14]).

Similar tactics have continued and expanded during the war, pointing to the ongoing evolution of disinformation approaches and constant need to adapt and respond. The UK Government, for example, found that TikTok influencers were being paid to amplify pro-Russian narratives. Disinformation activities also amplified authentic messages by social media users that were consistent with Russia’s viewpoint in an effort to increase the spread of such narratives, giving an artificial sense of support while evading platforms’ measures to combat disinformation (The Guardian, 2022[15]). Efforts to manipulate public opinion on social media took place on Twitter and Facebook, with extensive efforts also concentrated on Instagram, YouTube and TikTok. Evidence also exists of disinformation campaigns taking place in the comments sections of major media outlets (The Guardian, 2022[15]).

More overtly, the Russian government runs co-ordinated information (and disinformation) campaigns on its own social media accounts. For example, 75 Russian government Twitter accounts, with 7.3 million followers garnering 35.9 million retweets, 29.8 million likes and 4 million replies, tweeted 1 157 times between 25 February and 3 March 2022. Roughly 75% of the tweets covered Ukraine and many furthered disinformation narratives questioning Ukraine’s status as a sovereign state, drawing attention to alleged war crimes by other countries, and spreading conspiracy theories (Thompson and Graham, 2022[16]). Russian government accounts have also been linked to “typo squatting” (registering websites with deliberately misspelled names of similarly named websites) of popular news organisations containing false information. For example, Russian actors created a fake website of the Polish daily newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza, to spread disinformation about the atrocities reported in Bucha (Stefanicki, 2022[17]).

These tactics did not begin with the large-scale invasion of Ukraine. In 2017, for example, Facebook found evidence that the Internet Research Agency – a Russian-based organisation that has created and used false accounts to deceive and manipulate people (Stamos, 2018[18]) – had exposed 126 million of its users to political disinformation ahead of the 2016 US election (Dwoskin, 2021[19]). Facebook says it has uncovered disinformation campaigns in more than 50 countries since 2017, with the countries most frequently targeted by foreign disinformation operations in this period being the United States, Ukraine and Britain (Facebook, 2021[14]).

The impact of social media goes beyond its use as a direct source of information, given that feedback loops between social media, traditional media in OECD Member States, and Russian state-backed media can rapidly amplify information (and disinformation). Such a feedback loop was observed, for example, in the case of a conspiracy theory about Ukrainian biological facilities masked as a secret bioweapons programme. The theory was originally shared by Twitter accounts connected with conspiracy theories in the United States, amplified by “off-line” media outlets (in this case cable news), and subsequently shared by Russian state propaganda (Ling, 2022[20]).

Common disinformation themes

In the run up to Russia’s invasion on 24 February, disinformation messages broadly sought to demoralise Ukrainians, sow division between Ukraine and its allies and bolster public perception of Russia (Wahlstrom et al., 2022[21]). Claims included that the military build-up prior to the invasion was for training exercises only; messages focused on historical revisionism delegitimising Ukraine as a sovereign state (that Ukraine has no historical claim to independence and was created by Russia); claims about neo-Nazi infiltration in the Ukrainian government; claims of threats to Russian populations in Ukraine and about the Ukrainian government committing genocide in those parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts illegally controlled since 2014 by Russian-backed separatists; spreading “whataboutisms” that downplayed Russia’s large-scale invasion by drawing attention to alleged war crimes by other countries; etc. (Wahlstrom et al., 2022[21]) (Cadier et al., 2022[12]).

Since the war began, disinformation efforts have continued to focus on exploiting splits within Ukraine and between other governments. Analysis of Russian government and state-backed media during the war shows that current narratives revolve around several key themes. These include conspiracy theories about Ukrainian and US bioweapons research and so-called false flag operations, where Russia has claimed that acts they carried out were in fact committed by Ukraine with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility (Thompson and Graham, 2022[16]; Alliance for Securing Democracy, 2022[22]; Ilyushina, 2022[23]). The list of Ukraine-specific disinformation narratives is longed and constantly evolving (Box 1).

The following list compiles some of the most common myths and disinformation from more than 220 websites with a history of publishing false, pro-Russia propaganda and disinformation.

Classified documents showing Ukraine was preparing an offensive operation against the Donbas

The massacre of civilians in Bucha, Ukraine, during the first month of the war was staged

The United States is developing bioweapons designed to target ethnic Russians and has a network of bioweapons labs in Eastern Europe

Ukraine threatened Russia with invasion

US paratroopers have landed in Ukraine

Ukraine staged the attack on the hospital in Mariupol on 9 March 2022

European universities are expelling Russian students

Ukraine is training child soldiers

The war in Ukraine is a hoax

Russia was not using cluster munitions during its military operation in Ukraine

NATO has a military base in Odessa

Russia does not target civilian infrastructure in Ukraine

Modern Ukraine was entirely created by communist Russia

Crimea joined Russia legally

Ukrainian forces bombed a kindergarten in Lugansk on Feb. 17, 2022

The United States and the United Kingdom sent outdated and obsolete weapons to Ukraine

Nazism is rampant in Ukrainian politics and society, supported by Ukrainian authorities

Anti-Russian forces staged a coup to overthrow the pro-Russia Ukrainian government in 2014

Russian-speaking residents in Donbas have been subjected to genocide

Source: Cadier et al. (2022[12]), “Russia-Ukraine Disinformation Tracking Center”, News Guard, https://www.newsguardtech.com/special-reports/russian-disinformation-tracking-center/ (accessed on 17 April 2022).

Russia’s efforts to manipulate the information space, and even specific narratives, mirror those used to justify its military intervention in Georgia in 2008, the illegal occupation of Crimea and its intervention in the Donbas in 2014. For example, Russian claims to be protecting Russians and Russian-speakers overseas are not new. In 2014, Russia stated it invaded Donbas on the pretext that ethnic Russians were being threatened in Eastern Ukraine. Similarly, in 2008, the Russian government blamed Tbilisi for committing ethnic cleansing and illegally distributed Russian passports to “protect” Russians in South Ossetia, as it did in Donbas (Seskuria, 2022[24]).

Mechanisms used by Russia to restrict the information space

While the narratives and overarching goals used have remained largely consistent, the tools available for disseminating false and misleading content, and Russia’s ability to control its own information environment, have continued to evolve. The government’s control over its domestic media (including traditional media, such as television and print, and online media) and the information and news the public receives allows it to squeeze out independent and fact-based reporting, replacing them with official narratives across major channels. In such a closed system, lack of access to reliable polling data or reporting makes it difficult to know the extent of public support for the war within Russia or of the public’s trust in the messages they are receiving. While by early April roughly 15 400 Russians had been arrested for protesting against the war (McCarthy, 2022[25]), and opposition and independent media reports have received tens of millions of views online, in the absence of protected civic space that allows people to air their views, the true extent of public support for the war against Ukraine in Russia is unclear.

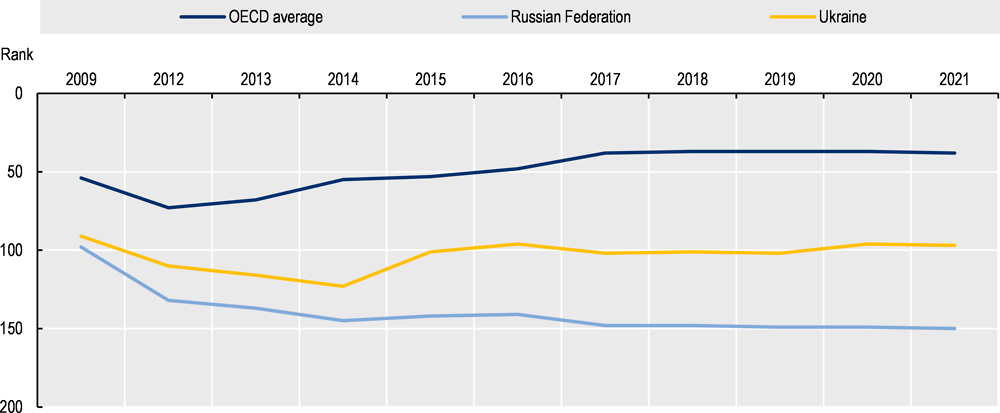

Reduced freedom of expression, limited opportunity for public debate and the state’s growing influence over the traditional and non-traditional (online content, social media) news and information landscape is reflected in Russia’s World Press Freedom Index (Reporters Without Borders, 2022[26]) ranking from Reporters Without Borders, having steadily decreased since 2010 (Figure 1). Furthermore, independent public service broadcasters do not exist in Russia, and independent media are effectively banned. Such restrictions also make it easier to control narratives abroad on Russia’s war in Ukraine by forcing foreign media based in Russia to self-censor their reporting in response to banned themes and words (Reporters without Borders, 2022[27]).

Source: (Reporters Without Borders, 2022[26]).

Roskomnadzor, the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media, enforces the state’s opposition to information to which it objects. Two days after the 2022 invasion, Roskomnadzor announced that media organisations could only publish information from official government media outlets on the war. The announcement also declared immediate investigations into 10 media outlets for the “dissemination of unreliable publicly significant information” (RFE/RL, 2022[28]) and ordered them to delete news and commentary that used terms such as “invasion” and “war” (outlets are instead required to use the term “special military operation”) ( (Izadi and Ellison, 2022[29]). The media outlets affected included the radio station Ekho Moskvy and TV Dozhd (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2022[30]), which were subsequently blocked from broadcasting on 1 March; until then they had “been the sole remaining major independent broadcasters in Russia in the radio and television market, respectively” (International Press Institute, 2022[31]). They were blocked for the “purposeful and systematic” publishing of news that contained “calls for extremist activity, violence and deliberately false information regarding the actions of Russian military personnel as part of a special operation to protect the contested separatist states of the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic” (International Press Institute, 2022[31]). Roskomnadzor is also in close contact with Russia’s security forces (Box 2).

Since September 2020, Roskomnadzor has been increasing its monitoring of online protest and anti-war sentiment using an automated monitoring system called the “Office of Operational Interaction”. The system monitors mass media and internet communications for content that could counter official positions, such as criticism of Russian state officials, sanctions pressure, religious/ethnic conflict, and “pro-Western” interpretations of WWII history. Roskomnadzor sends daily monitoring reports to regional and local branches of the Federal Security Service (FSB) and the Ministry of Internal Affairs, as well as regional governments and federal inspectors.

Source: Meduza (2022[32]), “The Hunt for ‘Antimilitarism’: Leaked Documents Indicate That Russia’s Federal Censor Has Been Monitoring the Internet for Peace Activism since at Least 2020”, https://meduza.io/en/feature/2022/04/13/the-hunt-for-antimilitarism (accessed on 14 April 2022).

News aggregators, which do not produce the content that they share, can also be affected by Russia’s control of the information space. For example, Roskomnadzor restricted access to Google News, accusing it of providing access to "false" information about Russia’s war against Ukraine, based on a decision taken at the request of the Russian General Prosecutor's Office (Reporters without Borders, 2022[27]). Roskomnadzor also threatened to fine Google over “illegal” YouTube videos containing information about Russia’s “special military operation” (Roth, 2022[33]).

In addition to Roskomnadzor’s censorship, one of Russia’s most effective means of controlling narratives around the war has been via its law on spreading “fake news” about Russia’s armed forces, adopted by the State Duma on 4 March 2022. The law is ambiguous, allowing for wide application. For example, the law covers “public dissemination of deliberately false information about the use of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation”, without specifying what qualifies as false information. The law also provides legal means to apply fines of up to 500 000 roubles (EUR 6 200) or to imprison citizens for up to fifteen years for violations (TASS, 2022[34]; Bloomberg, 2022[35]).2

The Russian government has also taken direct actions against journalists and citizens. Soon after the outbreak of the war, journalists and citizens were arrested across the country for their reporting or public comments (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2022[36]). For example, in Sakhalin, a teacher was fined 30 000 roubles (roughly EUR 370) for telling students that she considered the invasion of Ukraine a mistake (Сибирь.Реалии, 2022[37]). An artist in St. Petersburg was arrested, pending trial on 31 May, for replacing price tags in a shop with information about Russia’s bombing of civilians (Meduza, 2022[38]).

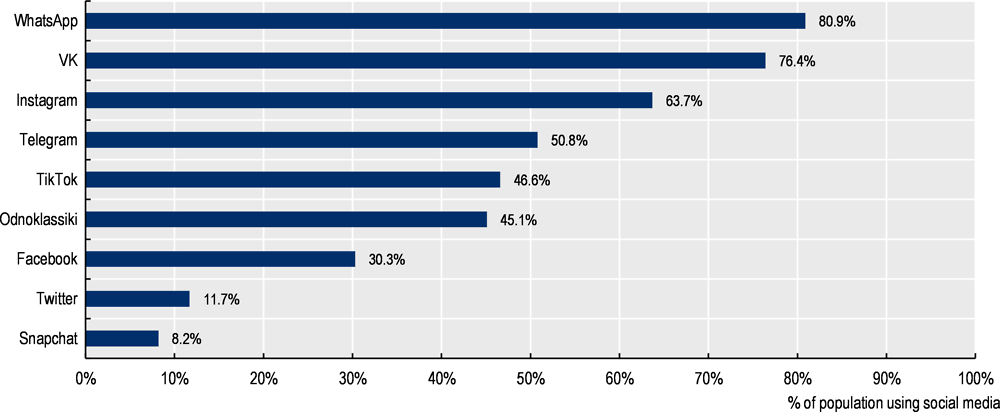

The government is simultaneously limiting access to social media platforms within Russia. Foreign-based companies are much harder to control than local equivalents (such as VKontakte or Odnoklassiki), which are popular among the population and where the means of applying pressure by the Russian state are more numerous (Figure 2). The Russian government took control of VKontakte in 2014, for example, after its founder refused to hand over information on anti-Kremlin protestors (Allyn, 2022[39]).

Source: (Statista, 2022[40]).

For its part, LinkedIn has been blocked in Russia since 2016, as the company has chosen not to meet regulatory requirements stipulating that personal information of Russian citizens must be stored on servers in Russia (BBC News, 2016[41]). Almost a month into Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, Russia’s general prosecutor declared Meta an extremist organisation, leading to the banning of Facebook and Instagram in Russia. This action followed the government’s restriction of Twitter earlier in March 2022 (Euronews, 2022[42]). Immediately prior to the ban, demand for VPNs, which encrypt data and obscure where a user is located, rose more than 2000% compared to the daily average the month prior, suggesting the continued demand for these platforms in Russia (Euronews, 2022[43]). TikTok, a globally popular video sharing platform, has also caused numerous problems for the Russian leadership, as users of the social media platform have revealed troop positions and equipment movements in the lead up to the war (Mamo, 2021[44]; Mackinnon, 2021[45]). Telegram, a messaging service created by the founder of VKontakte, has also become a means for sharing information among its users, as well as providing a platform for media outlets and journalists to continue their work uncensored. Offering both encrypted and unencrypted chat functionality, its popularity has continued to grow since Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine began, and it has become a source of both independent news and propaganda and disinformation (Allyn, 2022[39]). According to a poll conducted by the research firm Romir, between February and June 2022, the audience share of Telegram channels in Russia grew by 40% to almost 27% – a higher percentage than for any individual state TV channel (Радио Свобода, 2022[46]). Furthermore, a Levada Centre poll from July 2022 found that while television is still the main news source for 63% of the population, that share has been declining steadily; conversely, reliance on social media as a source of news has increased to 39% of respondents (Левада-Центр, 2022[47]).

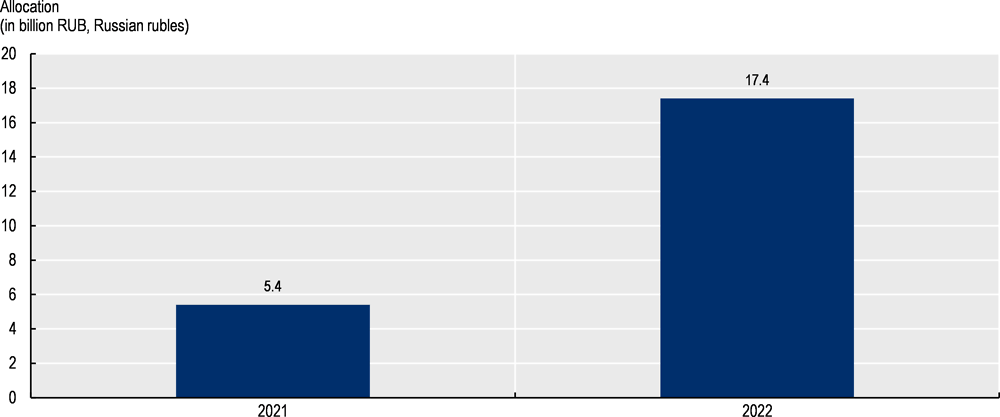

Russian state control and propaganda

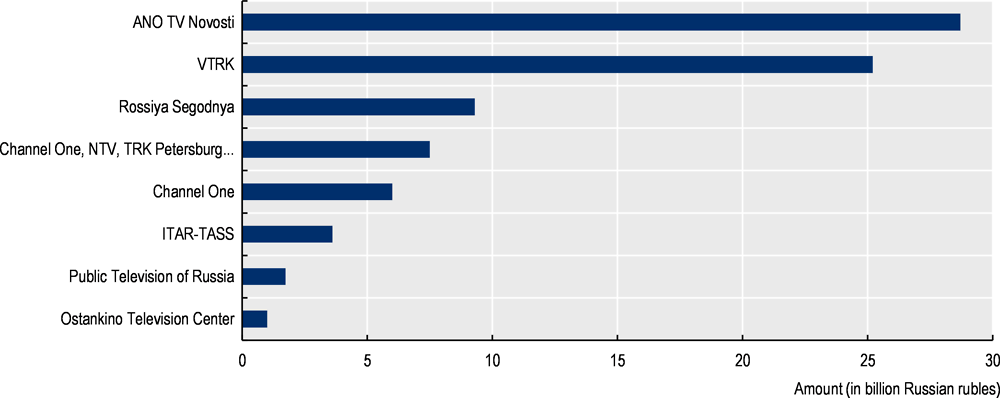

Beyond the overt efforts to censor specific content, the Russian legal environment is highly unwelcoming to the free press. Private and public media organisations are either owned or run by government-linked individuals and entities. Efforts to control the information space during the current war can also be seen via budgetary spending increases for state media in the run up. Government spending on “mass media” for the first quarter of 2022 was 322% higher than for the same period in 2021, reaching 17.4 billion roubles (roughly EUR 215 million) (Figure 3). Almost 70% of Russia’s spending on mass media in Q1 2022 was spent in March, immediately after the invasion (The Moscow Times, 2022[48]). The outlets that receive these funds, including RT and Rossiya Segodnya, which owns and operates Sputnik and RIA Novosti (Figure 4), are state-linked and state-owned outlets that “serve primarily as conduits for the Kremlin’s talking points”, according to the US State Department (US Department of State, 2022[49]) and can be more accurately thought of as tools of state propaganda (Cadier et al., 2022[12]).

Where audiences previously received information predominantly through Russian state-backed television, the rise of the internet and social media have allowed the Russian government to conduct information operations on a far broader scale at a fraction of the price (Paul and Matthews, 2016[13]). A steady uptake in internet usage (85% of Russians accessed the internet as of 2021 (International Telecommunication Union, 2021[3]) is one motivating factor. Another, however, is that an online presence has allowed them to reach audiences abroad easily and cheaply. Indeed, on some platforms, Russian state-backed media has likely made money from spreading propaganda. Prior to the war, estimates place the value of advertising revenues on YouTube from RT and other state-affiliated channels at USD 27 million between 2017 and 2018 (and up to USD 73 million between 2007 and 2019) (Omelas, 2019[50]).

Source: (The Moscow Times, 2022[51]).

As reflected in their budgetary allocations, Sputnik, RT and TASS are among the most influential government/state funded and operated media outlets for spreading disinformation at home and abroad (Statista, 2022[40]; Cadier et al., 2022[12]). RT in particular has seen rapid uptake. In 2013, it became the first news network to surpass 1 billion views on YouTube (Dwoskin, Merrill and De Vynck, 2022[52]). By March 2021, RT DE (the German branch) ranked sixth for most shared media outlet in a study of Telegram groups and channels, ahead of German news publications such as Der Spiegel. Sputnik (known in Germany as SNA), came eighth, while the Russian newspaper Pravda ranked 11th (Loucaides and Perrone, 2021[53]).

Source: (The Moscow Times, 2022[51]).

Russian propaganda is potentially exacerbating polarisation, even in the most mature democracies. Research conducted by IFOP (Institut D’études Opinion et Marketing en France et à L’international) shows that more than half of French people believe that at least one explanation about the cause of the war promoted by the Russian government is true, with those voting on the extreme right and extreme left being significantly more likely to believe Russian propaganda on the origins of the war (IFOP, 2022[54]). The potential impact – or at least acceptance – of Russian propaganda can be seen across Europe. For example, in April 2022, while 78% of European citizens agreed that Russian authorities are responsible first and foremost for the war in Ukraine, 17% of did not clearly hold Russia responsible. This number also varies widely across EU countries, with much higher numbers in Cyprus (51%), Bulgaria (46%), Greece (45%), Slovenia (39%), Slovak Republic (36%) and Hungary (34% ) (European Commission, 2022[55]).

The success of Russian outlets, in terms of interest and views, can also be seen outside of Europe. Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, RT en Español was the second most popular Spanish-language YouTube channel (by subscriber) with 5.95 million subscribers, fewer than Univision Noticias (with 6.92 million subscribers) though more than Noticias Telemundo with 5.8 million (Social Blade, 2022[56]). On Twitter, RT en Español was the third most shared site for Spanish-language information about the war as of early April, outperforming local news sources as well as international outlets like the BBC and CNN (Associated Press, 2022[57]). In the last two weeks of January 2022, Russian state-owned media outlets shared 1 600 Spanish language posts in a variety of formats (video, articles, etc.) that referenced Ukraine. Gathering nearly 173 200 engagements (likes, shares, and comments), these posts accounted for almost 40% of engagements by Spanish language users on the invasion of Ukraine (Detsch, 2022[58]).

Russian-backed media has also targeted the Middle East and Africa. Shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the post frequency of RT Arabic and Sputnik Arabic on Twitter increased 35% and 80%, respectively. Furthermore, the state-owned news agency TASS indicated its intention to expand its reach in the continent, by opening offices in Nigeria, Senegal and Ethiopia, among others (TASS, 2019[59]). The threat of the spread of disinformation across these channels is clear: of RT Arabic’s six most popular tweets in early March, three amplified false narratives from the Russian Foreign Ministry about secret biological weapons laboratories in Ukraine, and the third most popular tweet in late March was a video claiming that a Ukrainian military commander had ordered the massacre of civilians in Bucha (Janadze, 2022[60]).

Russia’s disinformation campaigns abroad are widespread and go beyond the Ukrainian context. For example, in Africa, Russian and Russian-affiliated actors have created messages disparaging democracy and spreading misleading and false information about political actors, as well as narratives seeking to stoke social tensions (Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2022[61]). In 2021 in Mali, for example, a co-ordinated campaign across social media platforms spread anti-French, anti-UN and pro-Russia messages. More recently in Nigeria, journalists’ accounts were hacked to spread false narratives about the war in Ukraine, posting 766 unauthorised messages across Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn (Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2022[61]). This ability of Russian disinformation to attract the attention of international audiences signifies the extent to which the government seeks to expand its global influence, sow confusion and undermine responses to its actions.

It should be noted that audience reach can be difficult to measure, particularly for RT and Sputnik, given that they operate as part of a complex network composed of numerous brands, websites, and social media accounts. That said, even if audience and engagement statistics are incorrect, this does not necessarily diminish the risk they pose in spreading Russia’s disinformation narratives. RT’s content can change the opinions of its viewers, even when they are aware that RT is funded by the Russian government (US Department of State, 2022[49]). Notably, RT had eleven million viewers in the United States in 2017, and 60% of all articles disseminated by its Twitter account focused on critical stories across three themes: coverage of America’s allies; US foreign policy; and US domestic conditions. A 2021 study found that exposure to RT stories increased American viewers’ preference for the United States to withdraw from its global leadership position; increased the perception that the United States is doing too much to solve global problems; and encouraged viewers to place more value on national interests over the interests of allies (Carter and Carter, 2021[62]).

Ukraine’s response

Ukraine has long been subject to disinformation from Russia, but the 2014 annexation of Crimea spurred a new level of intensity in the narratives and complexity. The flow of mis- and disinformation from Russian state-linked sources increased further in the immediate run-up to and during the war. Ukraine’s experience of managing Russian information attacks has informed its responses to the current context, though the government will need to continue to build resilience to Russian disinformation for the duration of the war, and to ensure that it remains able to withstand it in the future.

Context and reforms since 2014

Compared to Russia, Ukraine ranks much higher in the World Press Freedom index, and has seen improvement in its score since 2014 (Figure 1). Up to the invasion in February 2022, Ukraine’s democracy was strengthening: the media landscape was broadening; the country pursued efforts to curtail corruption and promote transparency, including through its membership in the Open Government Partnership; and reforms were undertaken to support media integrity, local democracy and elections (Fernandez Gibaja and Hudson, 2022[63]).

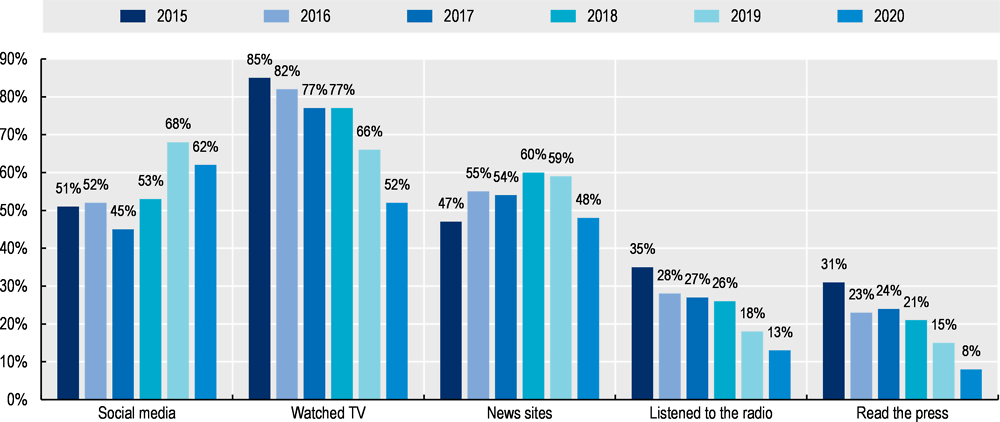

Traditionally dominated by television as a form of both entertainment and news, websites and social media have gained popularity as sources of information. Since 2015, the percentage of Ukrainians using television, radio and print media to receive news has steadily declined, while on average, social network usage and news websites have grown (Figure 5) (USAID and Internews, 2020[64]). Indeed, the start of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine saw a large increase in the use of social networks as a source of news. According to a study conducted in May 2022,3 the top sources of news in Ukraine were social media networks, used by 77% of Ukrainians, followed by television (67%) and the internet excluding social networks (61%). Particularly striking was the increase in the importance of social media as a source of news, which rose from 62% in 2020 to 77% by May 2022. The platforms that people use have also changed: since the start of the war, Telegram has become the leading source of information for Ukrainians, followed by YouTube, whereas Facebook has moved from first to third place (USAID and Internews, 2020[64]; Snopok and Romanyuk, 2022[65]).

Source: (USAID and Internews, 2020[64]).

The long-running USAID-Internews Media Consumption Survey has also noted, however, that media literacy remains a challenge, although the public is taking a greater interest in the source of its news and the representation of viewpoints. While 77% of respondents to the 2020 USAID-Internews Media Consumption Survey in Ukraine4 were broadly aware of disinformation (a slight increase from 2019), 58% of these did not consider it to be an urgent problem (USAID and Internews, 2020[64]).

Ukraine’s efforts to strengthen its media sector since 2014 has been an essential pillar of its resilience to mis- and disinformation during Russia’s current war against the country. The establishment of a public broadcaster, UA:PBC (Public Broadcasting Company of Ukraine, rebranded as Suspilne in 2019), in January 2017 was a key element of Ukraine’s efforts to meet European standards and practices. Alongside its legal registration, Suspilne focused on capacity strengthening and the adoption of strategic documents to solidify its independence. Due to the annexation of Crimea and ongoing aggression in the eastern part of the country, the broadcaster even devised plans to continue operations should Russia invade again. Indeed, independent media organisations in Ukraine have noted its high – and improving – quality (Institute of Mass Information, 2021[66]).

Alongside UA:PBC’s formalisation and professionalisation, other major reforms of Ukraine’s media environment include privatising state-owned print media, notably via the 2015 Law No. 917-VIII on Reforming State and Communal Print Media, which required state-owned printed media to be privatised by the end of 2018. A number of other relevant reforms and changes came about following the 2014 Euromaidan demonstrations, which broadly sought to bring Ukraine closer to the European Union, including reduced legal pressure on the media and political influence of state-owned outlets, as well as improvements to the law on access to information, increased autonomy of the broadcasting regulator, and legislation introducing mandatory disclosure of media ownership and final beneficiaries (Freedom House, 2015[67]) (Freedom House, 2016[68]). The success of these reforms was reflected in the jump in the country’s World Press Freedom Index Rank from 2014 to 2016. Ukraine’s score remained relatively stable until 2022, when it dropped slightly due to the challenges and threats to journalists due to the war (Reporters Without Borders, 2022[69]).5

Reforms have been supported by foreign donors, notably Germany and Sweden, as well as the United States through the National Endowment for Democracy’s (NED) Center for International Media Assistance (Chevrenko, Benequista and Dvorovyi, 2022[70]). Between 2010 and 2019, almost USD 150 million was given to support the development of Ukraine’s media sector (Chevrenko, Benequista and Dvorovyi, 2022[70]). From 2014, NED alone distributed roughly USD 22 million toward projects focused on promoting independent information and democratic debate, as well as increasing the capacity of regional and local media (National Endowment for Democracy, 2022[71]; Council of Europe Office in Ukraine, 2022[72]). In addition, in 2021, the Council of Europe funded a project with Suspilne to “enhance the role of media, its freedom and safety, and the public broadcaster as an instrument for consensus building in the Ukrainian society” (Council of Europe Office in Ukraine, 2022[72]).

However, Ukraine’s media environment also suffered from several challenges prior to Russia’s invasion. Funding in Ukraine’s media space, as elsewhere, is a major issue. While UA:PBC can theoretically compete with privately owned media for licences (it is also free), competing on quality is much harder, especially as it received only 60% of its legislated entitlement in 2020 and 82% in 2021 (Huss and Kuedel, 2021[73]).

Ukraine’s media landscape hosts a large number of outlets and information sources, although many of these are beholden to their owners and their political connections, leading to the landscape being described as having the “appearance of pluralism” (Korbut, 2021[74]). Ukrainian media remains significantly influenced by the financial support and political agendas of oligarchs who may promote their personal economic and political interests at the expense of the public interest (Freedom House, 2022[75]). Even prior to the war, analysis conducted by the Council of Europe’s media freedom project in Ukraine noted that solidifying reforms, promoting fair and impartial media coverage of elections, and upholding freedom of expression and ethical standards for journalists are key priorities (Council of Europe Office in Ukraine, 2022[72]).

Finally, since 2014, Ukraine has developed a rich civil society landscape supporting the media sector. For example, civil society organisations (CSOs) focus on responding to mis- and disinformation, conduct monitoring and debunking activities, as well as producing research and indices, such as the Freedom of Speech Barometer developed by the Institute of Mass Information, the Ukrainian partner of Reporters without Borders.6 Civil society moved fast to combat the Russian information threat, a testament to experience gathered since 2014. As Russia’s war against Ukraine continues, maintaining the country’s reform momentum since 2014 and strengthening the enabling environment in which CSOs, journalists and watchdog organisations operate will become ever more vital for Ukraine’s media environment.

Targeted responses to Russian disinformation

Russia’s war against Ukraine has rapidly magnified the urgent challenges of responding to the threats posed by the spread of disinformation while maintaining an independent media sector capable of informing the public under challenging and dangerous conditions. As noted previously, however, the disinformation threat in Ukraine is not new, and the government had taken specific steps to counteract it even before the war.

In May 2021, the country established the Centre on Countering Disinformation (CCD). The CCD is a body of the National Security and Defense Council (NSDC), and provides monitoring and analysis of information threats to Ukraine’s national security (Matyushenko, 2021[76]). Since Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine began in February 2022, it has conducted fact-checking and debunking activities on Telegram and Twitter.7 The Center provides the Ukrainian government with an official, expert means of countering Russia’s disinformation campaigns. To-date, most of its communications have focused on presenting examples of manipulated or false content, updates on military developments, and posts that aim to help build media and information literacy by explaining how information and psychological operations are developed.

Social media has also become a platform for the government to collect information from and spread information directly to citizens, and even lobby for international support. While using social media is not a new activity for leaders and governments, the urgency and challenges presented by Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine demonstrate the utility of platforms in the context of war for collecting and spreading information to vast audiences in short periods of time. For example, Ukraine’s Ministry of Digital Transformation developed a chatbot on Telegram that allows citizens to send videos and locations of Russian forces, which Ukraine’s army can use to supplement other sources of intelligence (The Economist, 2022[2]).

Regarding sharing information with the public, the President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky, has almost 1.4 million subscribers on Telegram8 where he shares personal videos, sometimes shot seemingly spontaneously on a smartphone, directly to the Ukrainian population. His videos include daily updates on the war, motivational speeches, pictures of Russian destruction, and appeals to the international community. Many of his videos and posts are translated into English. His Twitter account9 often shares updates on his conversations with other leaders and calls for assistance.

Another member of the Ukrainian government who has taken to social media is the Minister of Digital Transformation Mykhailo Fedorov. He has used his social media presence to engage with Ukrainian expat networks and pressure companies and organisations for aid. For example, his tweet to Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, requesting satellite internet systems has resulted in up to 5 000 devices being delivered (with funding from USAID, Poland and France) to Ukraine to replace internet infrastructure destroyed by Russia (Bachman, 2022[77]). Musk replied to Fedorov’s Tweet, with the Minister also confirming delivery of the satellites on Twitter. This application of direct pressure is a departure from how political leaders, ministers and other public officials traditionally communicate, by appealing directly to publics and their governments, as well as by allowing Ukrainian citizens to engage directly in public diplomacy (Zakrzewski and De Vync, 2022[78]). These efforts to communicate directly and to provide a stream of morale boosting content in times of war have shown the benefit of highly accessible communication styles. Combined with open appeals for assistance and online diplomacy, the impression of a functioning government has largely continued during a time of enormous upheaval.

The media and information space in Ukraine in response to Russia’s aggression

Although online communication tools have facilitated the dissemination of information, engagement and reporting, the war has also increased the dangers journalists face. Physical safety equipment, such as bullet proof vests and helmets, are vital as Russia has demonstrated its willingness to target media. Since the start of the invasion, at least 12 journalists covering the war in Ukraine have been killed (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2022[79]), and the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression noted that journalists have been “targeted, tortured, kidnapped, attacked and killed, or refused safe passage from cities and regions under siege” (UN, 2022[80]). Journalists have faced enormous challenges since the start of Russia’s war against Ukraine and have had to adapt quickly to the new reality. The need to contend with new costs, such as providing protective equipment and relocating operations, has also added to news organisations’ financial pressures (Chevrenko, Benequista and Dvorovyi, 2022[70]).

Nonetheless, media organisations have found themselves rapidly adapting to the situation. UA:PBC relocated from Kyiv to Lviv and continues to broadcast national news. While this involved moving 120 newsroom workers and their families, the majority of the broadcaster’s 23 regional offices were still reporting from the ground almost a month into the war. In the days immediately following the invasion, more than 100 000 people subscribed to the broadcaster, who upon the request of the government, began transmitting news and information as notifications on Telegram and Viber, another social messaging platform (Pahlke, Senftleben and Bodine, 2022[81]).

The Government of Ukraine has also intervened directly in the private media space. The three largest private media organisations (StarLightMedia, 1+1 Media, and Inter Media Group) joined public broadcasters UA:First and Ukrainian Radio to provide unified round-the-clock coverage under the ‘United News’ project. After the heads of the broadcasters met amongst themselves at the start of the war, President Zelensky signed a decree on 18 March requiring all national TV channels to broadcast through one platform, for which funding would be provided from the government. While effective for providing access to information and important for controlling narratives around the war in the face of Russian disinformation campaigns, this approach raises questions over direct state intervention in the media environment once the war is over. Moving forward, it will be extremely important to decouple these organisations from the current level of oversight and control by the state to ensure their independence, and to avoid backsliding on gains made in the media environment since 2014.

Practically, each channel produces a segment of news for a slot of the 24-hour news cycle, which is then broadcast by the other channels. In this case, coverage could continue should one provider lose its ability to broadcast. Some regional providers have also joined the initiative, and all fees have been waived to make access to news free (Dyczok, 2022[82]). Similarly, difficulties with accessing television and print media led to the development of the application RadioPlayer.ua, which provides free access to United News output in Ukrainian, English and Russian, also available through the state’s e-services application DIIA. Ukrainian mobile operators do not charge or deduct from allowances for connecting to it. Removing financial barriers to information in this manner is essential to help ensure citizens can access news in extremely challenging circumstances.

In addition to supporting efforts to increased access to news, Ukraine has also limited access to Russian state-linked media in an effort to reduce its influence. Ukrainian media, whether public broadcasters or privately owned networks, have historically been in direct competition with Russian language media. In fact, 2020 saw the percentage of Ukrainians using Russian media increase to 17% from 13% in 2019 (USAID and Internews, 2020[64]). On 16 January 2022, one month before the Russian attack, a law came into force requiring all national print media to be published in Ukrainian, the country’s official language. The aim was to push back against the use of the Russian language (and influence) in the public sphere (RFE/RL, 2022[83]). The law stipulated that a least 90% of airtime on national TV should be in Ukrainian and that local channels were allowed no more than 20% of non-Ukrainian language content (Yesmukhanova, 2020[84]).

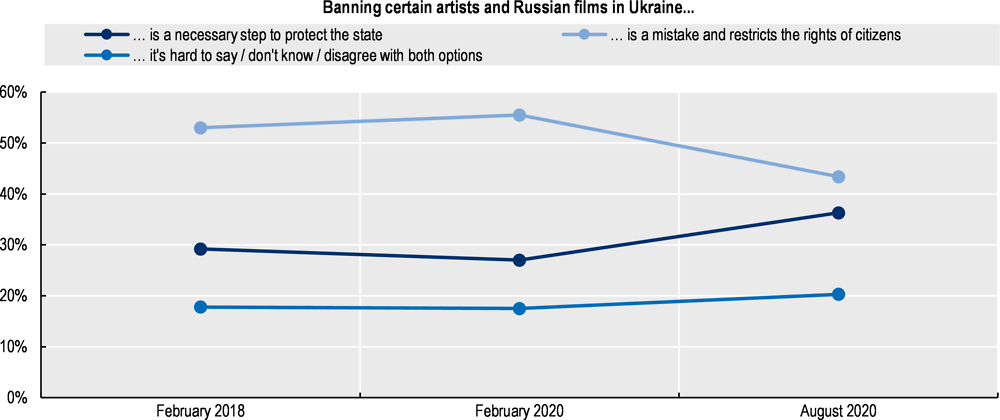

The law reflects wider public opinion on the cultural influence of Russia, with growing support for banning certain artists and Russian films in Ukraine after the 2019 elections (Figure 6) (Razumkov Centre, 2020[85]). The law was met with international criticism, on the basis that it threatened the cohesion of an already fragile society (Huba, 2022[86]) and eroded the rights of minorities (Denber, 2022[87]). Such restrictions to freedom of expression point to the complexity of content-specific regulations and the inherent risks to civic space and democratic norms that they pose, even if done with the stated goal of responding to foreign information threats. Continued monitoring of the human rights landscape and the impact of such restrictions, protecting freedom of expression and association, and facilitating access to information will be crucial for the future of Ukraine’s democracy both during the war and afterward.

Source: (Razumkov Centre, 2020[88]).

In addition, Ukraine’s NSDC sanctioned three TV channels linked to the MP Viktor Medvedchuk; NewsOne, 112 Ukraine, and ZIK. Viktor Medvedchuk is the godfather of Vladimir Putin’s daughter and was placed under house arrest in May 2021 facing accusations of treason and attempting to steal state resources in Crimea; in September 2022, he was released to Russia as part of a large prisoner exchange between the two sides. These TV channels had spread misinformation and Russian government-aligned messages about COVID-19 vaccines, statements that Ukraine was under external governance (particularly due to Ukraine’s relationship with the International Monetary Fund), and that the Ukrainian leadership was a “dictatorship” (linking to narratives around violations of the rights of ethnic Russians and the Russian-speaking population). To avoid the sanctions on these networks, Medvedchuk merged his TV channels into one, named First Independent (Pershyi Nezalezhnyi). The NSDC almost immediately blocked it from satellite broadcasting. The blocking of First Independent forced the channel to move to YouTube, where coverage continued to spread pro-Russian narratives (Bidochko, 2022[89]).

Although effective in removing Russian-state linked media, the ability of the NSDC to move so rapidly against media organisations raises questions over whether Ukraine’s media regulations are suitable and the appropriateness of such oversight being enforced by it. The precedent set by the government to make provider and content-based decisions will need to be carefully monitored and evaluated as the country seeks to rebuild from the war and expand upon its media reforms to improve the information ecosystems needed to underpin democracy.

International response

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine helps illustrate the range and extent of efforts certain actors can take to spread false and misleading content, and highlights the need for rapid and continued evolution in ways to counteract these threats. Governments and international organisation have largely been tackling the ‘firehose’ (Paul and Matthews, 2016[13]) of Russian disinformation by supporting fact-checking efforts and disseminating accurate information, increasing financial and material support for high-quality news production, and exploring regulatory responses.

Government efforts to counteract false and misleading content

Governments have sought to directly refute false and misleading content and to spread accurate content as part of an effort to counter and reduce the success of Russian disinformation. Prior to the invasion, the US and UK governments pre-emptively shared intelligence about Russia’s anticipated military activities exposed planned “false flag” attacks intended to stoke anti-Ukraine feeling (Bose, 2022[90]). The United States noted in November 2021 that it was aware of invasion plans, and in early 2022, the United States and the United Kingdom shared intelligence with allies and the public warning of an imminent attack.

While these strategic communication efforts did not prevent Russia from invading Ukraine, publicising intelligence made it more difficult for the government to disguise its intent or confuse the public discourse via disinformation campaigns, and likely supported the rapid and relatively unified response (Carvin, 2022[91]). This pro-active communication is a clear illustration of “pre-bunking,” an approach that aims to inoculate the public to potential mis- and disinformation. At its core, pre-bunking is about warning people of the possibility of being exposed to manipulative information, with the idea that such activities will reduce susceptibility to mis- and disinformation (Roozenbeek and van derLinden, 2021[92]).

In the United Kingdom, the Government Information Cell was created by the government shortly before the invasion to support the public communication function in debunking and countering Russian disinformation campaigns. It operates across various government ministries, producing strategic communication content to share online and advising up to 30 NATO and EU allies (Malnick, 2022[93]). The United Kingdom also relies on the Counter Disinformation Unit, part of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, to engage directly with social media platforms to flag what it has identified as false and dangerous content published on the platforms. Takedown decisions ultimately rest with the platforms (Dickson, 2022[94]).

Shortly after the invasion, Canada pledged USD 3 million to counter disinformation around Russia’s ongoing war of aggression against Ukraine (Prime Minister of Canada, 2022[95]). The US Congress’ emergency spending package also includes USD 120 million to counter Russian disinformation and propaganda (Pallaro and Parlapiano, 2022[96]). Similarly, the United States’ Global Engagement Center has been tracking and countering disinformation narratives since long before Russia’s invasion. In addition to debunking Russian government-linked narratives, the Global Engagement Center is providing detailed analytical and explanatory content on Russia’s efforts (US Department of State, 2022[97]). It also shares information with other government agencies, as well as those of its allies (Bose, 2022[90]).

Leveraging and limiting traditional and social media

Beyond strategic communication measures to respond to specific content, governments are pursuing efforts to leverage the broader opportunities for disseminating information via media and social media outlets. For example, governments have funded third parties and journalists, such as the BBC and independent journalists in Ukraine and Russia, to help ensure and expand the continued delivery of impartial news to help citizens avoid Russian restrictions on local and social media (GOV.UK, 2022[98]). The UK government allocated emergency funding to boost the BBC World Service’s ability to deliver “independent, impartial and accurate news to people in Ukraine and Russia in the face of increased propaganda from the Russian state” (GOV.UK, 2022[98]). These funds are allocated to offset the increased costs due to the war (such as relocation of staff), an issue faced by all broadcasters in the region. Similarly, the US Congress approved an emergency support package for Ukraine worth USD 13.6 billion that include USD 25 million for independent media and combatting disinformation (Pallaro and Parlapiano, 2022[99]), provided to the United States. Agency for Global Media, the organisation that oversees Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (Long, Seitz and Merchant, 2022[100]).

Governments have also sought to develop more constructive engagement through social media platforms, either by engaging with content creators, or by providing guidance to platforms. The US Government has, for example, briefed TikTok, YouTube and Twitter creators on Russia’s war in Ukraine in a similar manner to how it briefs journalists (Lorenz, 2022[101]). It also highlighted which Russian media organisations were spreading disinformation, but did not force platforms to ban them (although most did) (Bose, 2022[90]). Australia and the United Kingdom, on the other hand, followed suit with the European Union and explicitly asked social networks to block Russian state-linked services and content providers (Hurst and Butler, 2022[102]; Ryan and Seal, 2022[103]). On 22 March, the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, called for platforms to “diligently apply” their policies on content that is against the law and their terms of service, highlighting that many accounts are directly linked to the Russian government (Murphy and Espinoza, 2022[104]).

Russia’s war against Ukraine has led to a number of requests for action from governments, though as private companies, social media platforms broadly enforce terms and conditions as they like, within legal limits. Within the first few days of the war, Meta uncovered a network of pages, accounts and groups across Facebook and Instagram running websites that published Russian false news narratives (Gleicher and Agranovich, 2022[105]). YouTube banned RT and Sputnik’s channels across Europe on 1 March (Google Europe, 2022[106]), and has taken down more than 70 000 videos and 9 000 channels related to the war in Ukraine for violating content guidelines (Milmo, 2022[107]). Two days after the invasion, Twitter began labelling accounts affiliated with Russian state media (Fischer, 2022[108]). TikTok followed six days later (De Vynck, Zakrzewski and Dwoskin, 2022[109]). Reddit and Telegram (after a request from the European Union) went a step further, completely banning state-supported Russian media from their platforms; Twitter has also made similar efforts by stopping from amplifying state-run accounts (EU DisinfoLab, 2022[110]).

Many of the actions by social media platforms have been taken without a government request, and many platforms took action in ways that contradict previous policies. For example, in March, Facebook allowed users in Ukraine to publish posts calling for violence against “Russian invaders,” which reversed the company’s hate speech policy, which generally bars users from publishing violent posts (Bidar, 2022[111]). The lack of a clear framework for making decisions, or more transparent efforts to bring together external experts to provide context and advice, suggests platforms have not clearly articulated the basis on which they have made their decisions or how that might apply in other settings. Such an approach risks the perception of inconsistent decision making and potentially accusations of hypocrisy (Oremus, 2022[112]). As importantly, it has taken a war for social media companies to respond effectively to the threats posed by Russian disinformation, which largely pre-existed the war.

While these efforts taken by governments and the companies can limit the spread of Russian disinformation on their platforms, such actions can also have unintended effects. Banning types of content from one platform can simply push it to others with less stringent moderation policies that serve as echo chambers for extreme content. For example, RT moved to Rumble, a platform popular in some settings in the United States (Dang, 2022[113]). The trade-offs facing social media companies regarding maintaining access to information while limiting the spread of information that can distort public debate is magnified in the context of war, and identifying mechanisms for collaboration across governments and the platforms will need to continue to be explored.

Finally, governments have also focused on sanctioning and blocking media outlets. These efforts must be considered within the context of ongoing and longer-term efforts that respond to the opportunities and challenges posed by the rapidly evolving digital and social media landscape. A straightforward, though potentially problematic, means of countering Russian disinformation on the war in Ukraine has been blocking or sanctioning media outlets that spread it. The European Union has applied sanctions on RT (including RT English, RT UK, RT Germany, RT France and RT Spanish) and Sputnik. This only applies within the European Union and that the Russian government responded in kind, banning Deutsche Welle and other international media outlets (Interfax News, 2022[114]). In support of the EU sanctions, some governments, such as the United Kingdom, suspended the broadcasting rights or banned Sputnik and Russia Today from operating in an attempt to limit the spread of Russian disinformation (Lawson, Deka and Funanakoshi, 2022[115]; Kajosevic, 2022[116]). The European Union also directly sanctioned Russian individuals in the media in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This includes key personalities, such as Tigran Keosayan, host of NTV’s propagandist TV show “International Sawmill with Tigran Keosayan”; Olga Skabeyeva, journalist at Rossiya-1; Roman Babayan, journalist and host of NTV’s “Own Truth” show; Yevgeniy Prilepin, journalist and co-chairman of A Just Russia – Patriots – For Truth party; and Anton Krasovsky, host of “The Antonyms” talk show on RT. The sanctions include travel bans and asset freezes, as well as limitations to making funds available to the listed individuals (Gotev, 2022[117]).

The bans went ahead despite concerns raised over retaliation (Wintour, Rankin and Connolly, 2022[118]), which occurred when Russia directly blocked the BBC, Deutsche Welle and Voice of America (Reuters, 2022[119]). This response highlights the need to weigh the potential benefits of slowing the spread of disinformation via such bans with the clear risks they pose. Specifically, the corresponding blockages of outlets in Russia makes it increasingly difficult to share accurate information with Russian citizens about the war, already a major challenge. Banning Russian media also opens the door to accusations over freedom of expression.

International organisations

International organisations and cross-border initiatives have also undertaken numerous efforts to tackle Russian disinformation. These include relying on pre-existing structures, predominantly set up in the aftermath of Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, and mechanisms for enforcing regulation that have received increased funding and renewed interest in their activities since the war began in February 2022.

In parallel with individual country efforts, international organisations have undertaken fact-checking and debunking activities to counter Russian disinformation. For example, NATO maintains its own institutional collection of debunked Russian narratives about its role during Russia’s escalation in the build-up to the invasion (NATO, 2022[120]). Similarly, in January 2015 the European External Action Service’s (EEAS) East StratCom Task Force established the EUvsDisinfo after the annexation of Crimea. Its mandate is to forecast, address, and respond to Russia’s ongoing disinformation campaigns affecting the European Union, its Member States, and countries in the region (EU vs Disinformation, 2022[121]). Since February 2022, it has tracked more than 237 disinformation cases relating to Ukraine, and more than 5 500 disinformation total cases about Ukraine since its establishment in 2015 (out of more than 13 000 total examples of pro-Kremlin disinformation) (EU vs Disinformation, 2022[122]).

The European Union has also sought to provide platforms for information sharing. For example, the Rapid Alert System (RAS) on Disinformation allows the European Union’s EEAS to exchange alerts about disinformation campaigns, as well as analysis, trends and reports with other EU institutions, member states, and international partners, including the G7 and NATO (NATO, 2022[120]). The RAS aims to raise public awareness of disinformation and enable better co-ordination of responses. The initiative has faced criticism, however, that a lack of trust among member states has caused low levels of information sharing and engagement (Pamment, 2020[123]). In addition, the European Union provided funding for the European Digital Media Observatory in an effort to connect researchers, fact-checkers, media literacy experts and media organisations. This independent observatory facilitates closer co-ordination for fact-checking organisations, the scientific community, media literacy practitioners, journalists and policy makers via technological platforms, training and co-ordination of independent fact-checking and research activities (EDMO, 2022[124]).

The G7 group of nations has established a comparable structure via the G7 Rapid Response Mechanism. Established by Canada in 2018 to better anticipate, understand and fight dis- and misinformation (Government of Canada, 2019[125]), Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced in March 2022 that the Rapid Response Mechanism would receive USD 13.4 million over five years to deepen co-ordination between G7 countries in responding to threats to democracy (Prime Minister of Canada, 2022[95]). This came a year after the British government proposed strengthening the mechanism specifically in light of Russian “lies and propaganda or fake news” (RFE/RL, 2021[126]).

Additionally, NATO’s Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence provides a broad overview to disinformation threats to NATO member states and allies. It conducts research and shares good practices related to strategic communication topics. The Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence also hosts an annual conference; in May 2022, the focus of the event was on, among other things, countering global disinformation and what Russia’s war against Ukraine means for NATO (NATO StratCom, 2022[127]). These discussions are key for ensuring democracies can remain at the forefront of the disinformation threat across countries and allies.

International organisations have also contributed technical expertise to counter Russian disinformation. Prior to Russia’s large-scale invasion, during the period of escalation when the Russian Security Council recognised the independence of Luhansk and Donetsk regions, the European Union announced that it would deploy its Cyber Rapid Response Team to help Ukraine fight further Russian cyber-attacks (Ringhof and José, 2022[128]). Experts from various European countries are helping detect, recognise and mitigate cyber threats, which includes providing critical infrastructure and technical equipment (Cerulus, 2022[129]). NATO also recognised the threat posed by the spread of disinformation and announced its intent to increase information sharing about Russian cyber-attacks (Cerulus, 2022[130]). At the same time, private companies have helped mitigate the spread of false and misleading content, and have reinforced cyber security through providing avenues to report specific content as well as engage with Ukrainian, US, NATO and EU officials to advise them of potential threats.10 Such co-ordination is vital to stopping disinformation, which is enabled by cyberattacks that encompass automated information networks, targeting news websites, government portals and communication/internet infrastructure.

Technical assistance on these matters has been shared between the European Union and its partners through the aforementioned G7 Rapid Response Mechanism. This cross-border sharing allows institutions to reach external partners who suffer from Russian disinformation and its spread. As well as Ukraine, partners include countries where media freedom and threats to democracy more generally originate from Russia. Moldova, for example, received co-ordinated assistance from EU member states and “like-minded partners” to bolster their cyber resilience and help counter disinformation (European Commission, 2022[131]).

An additional international collaborative effort against Russian disinformation includes the Hybrid Centre of Excellence in Helsinki, Finland. The Centre is “an autonomous, network-based international organisation countering hybrid threats.” As such, it works to support European security and Ukraine, and although Ukraine is not an active participant, the Centre has sought to strengthen its partnership with Kyiv since the start of the war, supporting Ukrainian counter disinformation exercises and conducting analysis on its effects. The Centre has long researched and analysed Russian information threats, tactics and narratives, and plans to extend its programming with Ukraine (Hybrid CoE, 2022[132]).

The path forward

Responses to disinformation related to Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine broadly overlap with the three policy areas around which the OECD has clustered governance responses to the threat of mis- and disinformation. First, governments have focused on debunking and using the public communication function to fill information voids. They have also helped track threats and actors, shared information, and engaged with online platforms and civil society partners. Moving forward, supporting pre-bunking and debunking efforts to counter mis- and disinformation narratives, identifying ways to work transparently with social media and technology platforms and exploring how the public communication function can distribute timely information that is responsive to emerging narratives and reaches all segments of society will all be critical to help counteract the threat posed by disinformation, both related to the war in Ukraine and more broadly.

Second, the war has reiterated the potential benefits of policies that increase transparency of online platforms. Such measures include exploring the development of policy frameworks that facilitate the sharing of and access to relevant data of social media platforms, increasing transparency in spending on political advertisements online (see (Lesher, Pawelec and Desai, 2022[11])) for additional discussion of this point) and increasing transparency and understanding of algorithms and content moderation activities. Along these lines – though focused instead on combatting terrorist and violent extremist content (TVEC) online – the OECD has developed the Voluntary Transparency Reporting Framework (VTRF).11 This tool provides a common standard for TVEC transparency reporting for online content-sharing services to provide information about their TVEC-related policies and actions. Its application and the analysis derived from the reports collected can help establish an evidence base for better policies to promote transparency reporting around mis- and disinformation.

Social media platforms continue to grow in importance as means for people to share and engage with news and ideas. Information posted on social media platforms is also an increasingly important source of publicly available information – such as satellite images, videos and pictures – that is being analysed and even used as evidence of war crimes (referred to as open source intelligence, or OSINT) (OHCHR and Human Rights Center at UC Berkeley, School of Law, 2022[133]). Platforms also, however, serve as space for actors to spread false and misleading content and to influence mainstream media coverage. More fully understanding how information is shared, the sources of disinformation and what interventions are most successful – all within the bounds of ensuring user privacy and freedom of expression – are relevant for responding to disinformation related to the war in Ukraine and beyond. Regulatory proposals, such as the DSA in the European Union and Australia’s legislation related to the Australian Communications and Media Authority, which provide governments with greater ability to collect information on certain content and on steps taken to address mis- and disinformation from social media platforms, point to the ongoing significance of this area of work.

Finally, policy responses that strengthen the environment in which information is created and shared have proven to be relevant in the context of the war in Ukraine. Ukraine’s reforms since 2014 helped lay the ground for a more resilient media and information ecosystem. Efforts by the international community since the war started have included providing financial support to Ukrainian journalists and media organisations. Promoting and maintaining a diverse and independent media sector will help ensure the free flow of information; in the context of Ukraine, this will mean supporting independent civil society and media organisations whose operations have been destroyed, as well as continuing to advocate for free speech and the promotion of democratic values. Efforts may also include finding ways to ensure that accurate information reaches the Russian population, via support for both independent Russian language media and strategic communications initiatives. More broadly, supporting independent, quality, fact-based journalism, including independent public-service broadcasting, and encouraging media literacy campaigns to develop trust in the media and understanding of what constitutes good information will continue to play important roles.

Democracies will need to continue to identify ways to prevent the spread of – and respond to – specific disinformation threats related to Russia’s aggression. The war in Ukraine also highlights, however, the need to identify more systematic efforts to strengthen media and information ecosystems in Ukraine and democracies more widely. The fight against disinformation is, ultimately, the fight for transparency, truth and informed participation in public life, and the actions taken and lessons learned in Ukraine should continue to inform the larger efforts to reinforce democracy.

References

[61] Africa Center for Strategic Studies (2022), “Mapping Disinformation in Africa”, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/mapping-disinformation-in-africa/ (accessed on 8 May 2022).

[22] Alliance for Securing Democracy (2022), War in Ukraine: Dashboard, https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/war-in-ukraine/ (accessed on 16 April 2022).

[39] Allyn, B. (2022), “Telegram Is the App of Choice in the War in Ukraine despite Experts’ Privacy Concerns”, NPR, https://www.npr.org/2022/03/14/1086483703/telegram-ukraine-war-russia (accessed on 1 June 2022).

[57] Associated Press (2022), Russia disinformation on Ukraine spreads on Spanish-speaking social media, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/russia-disinformation-ukraine-spreading-spanish-speaking-media-rcna22843.

[77] Bachman, J. (2022), “U.S. Sends 5,000 SpaceX Starlink Internet Terminals to Ukraine”, Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-04-06/u-s-sends-5-000-spacex-starlink-internet-terminals-to-ukraine (accessed on 28 April 2022).

[40] BBC News (2016), “LinkedIn Blocked by Russian Authorities”, https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-38014501 (accessed on 26 April 2022).

[111] Bidar, M. (2022), Facebook allows posts calling for violence against “Russian invaders”, CBS News, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/facebook-allows-posts-violence-against-russian-invaders/.

[89] Bidochko, L. (2022), “Focus Ukraine: Fighting a Hybrid War with Hybrid Means: Zelensky Sanctions Pro-Russia Media and Parties”, Wilson Center, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/fighting-hybrid-war-hybrid-means-zelensky-sanctions-pro-russia-media-and-parties (accessed on 16 April 2022).

[35] Bloomberg (2022), “Russia Criminalizes Sanctions Calls, “Fake News” on Military”, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-04/russia-to-punish-sanctions-appeals-and-fake-news-on-military (accessed on 15 April 2022).

[90] Bose, N. (2022), “Analysis: How the Biden White House is fighting Russian disinformation”, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/world/how-biden-white-house-is-fighting-russian-disinformation-2022-03-04/ (accessed on 1 June 2022).

[8] Brown, S. (2020), MIT Sloan Research About Social Media, Misinformation, and Elections, MIT, https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/mit-sloan-research-about-social-media-misinformation-and-elections.

[12] Cadier, A. et al. (2022), “Russia-Ukraine Disinformation Tracking Center”, News Guard, https://www.newsguardtech.com/special-reports/russian-disinformation-tracking-center/ (accessed on 17 April 2022).

[62] Carter, E. and B. Carter (2021), “Questioning More: RT, Outward-Facing Propaganda, and the Post-West World Order”, Security Studies, Vol. 30/1, pp. 49-78, https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2021.1885730.

[91] Carvin, S. (2022), Deterrence, Disruption and Declassification: Intelligence in the Ukraine Conflict, https://www.cigionline.org/articles/deterrence-disruption-and-declassification-intelligence-in-the-ukraine-conflict/.

[129] Cerulus, L. (2022), “EU to Mobilize Cylber Team to Help Ukraine Fight Russian Cyberattacks”, Politico, https://www.politico.eu/article/ukraine-russia-eu-cyber-attack-security-help/ (accessed on 15 May 2022).

[130] Cerulus, L. (2022), “NATO Steps up Intelligence-Sharing “in Preparation” for Russian Cyberattacks”, Politico, https://www.politico.eu/article/nato-steps-up-intelligence-sharing-in-preparation-of-russian-cyberattacks/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

[70] Chevrenko, A., N. Benequista and M. Dvorovyi (2022), “Ukrainian Journalists Are Winning the “Information War” Russia Is Waging Against Ukraine, But They Need Help”, Just Security, https://www.justsecurity.org/81002/ukrainian-journalists-are-winning-the-information-war-russia-is-waging-against-ukraine-but-they-need-help/ (accessed on 1 June 2022).

[5] Chotiner, I. (2022), “Vladimir Putin’s Revisionist History of Russia and Ukraine”, The New Yorker, https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/vladimir-putins-revisionist-history-of-russia-and-ukraine (accessed on 1 June 2022).

[36] Committee to Protect Journalists (2022), “Across Russia, Journalists Detained, Threatened over Coverage of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine”, https://cpj.org/2022/02/across-russia-journalists-detained-threatened-over-coverage-of-russias-invasion-of-ukraine/ (accessed on 25 April 2022).

[30] Committee to Protect Journalists (2022), “Russia blocks Ekho Moskvy and Dozhd TV, restricts social media access”, https://cpj.org/2022/03/russia-blocks-echo-of-moscow-and-dozhd-tv-restricts-social-media-access/ (accessed on 2 June 2022).

[79] Committee to Protect Journalists (2022), Russia-Ukraine War, https://cpj.org/invasion-of-ukraine/.