How vocational education and training (VET) systems can support Ukraine: Lessons from past crises

Russia’s large-scale aggression against Ukraine has led to the most important humanitarian crisis in the OECD area since World War II, affecting millions of people and a severe economic, social and educational shock of uncertain duration and magnitude. This policy brief discusses how VET systems in host countries can become more inclusive and supportive of Ukrainians displaced by Russia’s large-scale aggression, building on OECD work on VET for young refugees,1 an analysis of VET in Ukraine, and first policy responses to the current crisis. It is the result of a joint effort of the OECD Centre for Skills, the Directorate for Education and Skills, and the Directorate for Employment Labour and Social Affairs.

Ukraine has strong VET provision at upper secondary level, and young people have strong interests in occupations which are commonly entered through VET. This policy brief argues that providing VET in host countries can be key in valuing and further building the skills of refugees from Ukraine, to the benefit of the Ukrainians concerned, host country labour markets, and for the rebuilding of Ukraine.

The key findings and recommendations are:

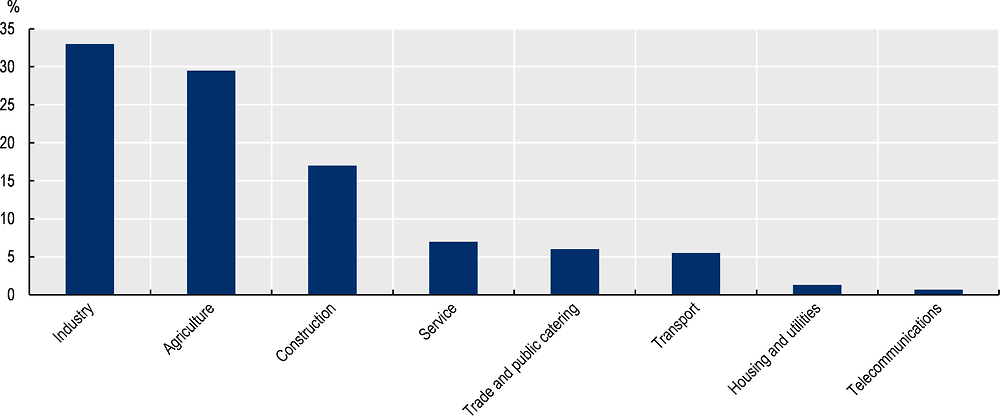

Ukraine’s educational attainment level is relatively high, and VET is an essential part of the educational system. In 2020, 44% of the active population had completed secondary education and a third of upper secondary students in Ukraine are in vocationally-oriented programmes. Industry has been the most popular sector for VET, followed by agriculture and construction. Prior to Russia’s invasion, Ukraine was in the process of strengthening its VET system, including through the introduction of dual apprenticeship-type programmes.

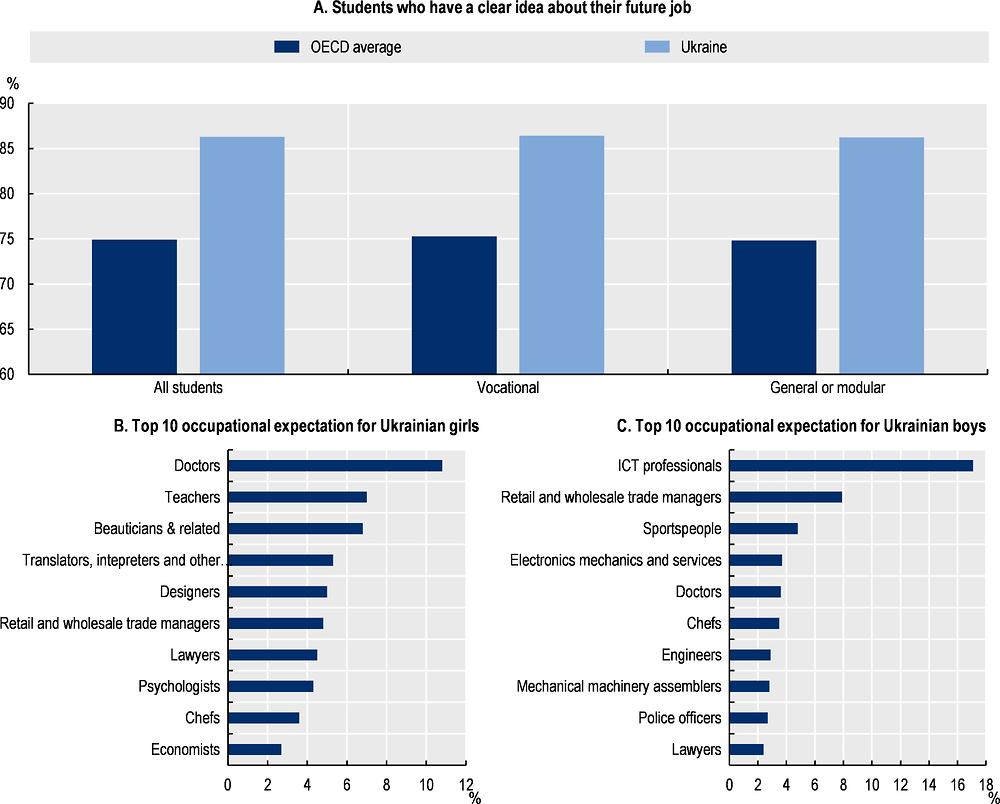

Compared the OECD average, Ukrainians are clearer at age 15 about their ambitions for working life, and occupations commonly entered through VET programmes are high on the list.

Occupations typically entered through VET are in high demand in host countries and will also be crucial for the reconstruction of Ukraine. VET is thus an investment with high expected returns, regardless of the duration of stay. The nature of VET as a “dual intent” measure should be considered in the policy responses by host OECD countries.

Several countries have taken specific measures to facilitate access to upper secondary or higher VET for Ukrainian refugees, including waivers of entry requirements. Countries were also quick to support Ukrainian teachers, including through waivers of specific language or diploma recognition requirements that would otherwise apply.

For refugee students, not only has education been interrupted, they are also facing personal, financial, language and social barriers at the same time. To overcome these and to fully take advantage of the benefits that VET can offer, host countries are advised to provide supportive measures that follow the journeys of young people as they get informed about VET systems, get ready to benefit from them, get into appropriate provision, and get on with their training to complete VET. These include: proactive career guidance, preparatory programmes for VET entry, flexible VET programmes with mentoring and targeted training assistance, recognition/validation of prior VET learning, and employer support and engagement. In addition, the host countries should also support Ukrainian VET teachers and strengthen teaching in a multicultural learning environment, while making effective use of digital technologies in VET.

The term “refugee” is used in this brief to include persons who obtained some sort of international protection, including not only formal refugee status (as per the Geneva Convention) but also subsidiary and temporary protection (as in the case of most refugees from Ukraine).

1. The Ukrainian refugee crisis

The Ukrainian refugee crisis impacts education and training opportunities

The Russian war of aggression against Ukraine has led to the most important humanitarian crisis in the OECD area since World War II, affecting millions of people and sparking a severe economic shock of uncertain duration and magnitude (OECD, 2022[1]). Over 5 million persons fled from war in Ukraine between February and mid-June 2022 – 12% of its population – and more than 7 million people are estimated to have been internally displaced within Ukraine (UNHCR, 2022[2]).

As of 10 May 2022, over 1 700 educational institutions in Ukraine (10% of the total) had been damaged by shelling. Of the remainder, several are being used as shelters for internally displaced persons, and education activities are often only taking place by distance (MESU, 2022[3]). The Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (MESU) also reported that almost 100 (about 12%) upper secondary VET institution buildings have been destroyed or damaged (MESU, 2022[4]). According to the Kyiv School of Economics, losses from destroyed or damaged educational institutions have reached USD 1.3 billion. The loss of infrastructure that affects future opportunities for school-based or work-based vocational education and training (VET), such as industrial units, healthcare institutions and kindergartens, could amount to almost USD 13 billion (KSE, 2022[5]).

There is also a high number of learners and teachers who have fled abroad or been internally displaced. As a result, the country is unable to carry out a normal admission procedure for VET. According to estimates from the European Training Foundation (ETF), 58% of VET students, 54% of VET teachers and 60% of VET schools in the regions under attacks (as of 30 March 2022) had been directly affected by the war (EC, 2022[6]). However, VET provision has resumed since early May 2022, albeit only in remote mode in a number of oblasts (MESU, 2022[4]).

Immediate policy support for the education and training of Ukrainian refugees has been put in place

For the first time ever, the European Union (EU) activated the Temporary Protection Directive for those fleeing Ukraine. They now have the legal right to stay in an EU Member State for an initial period of 1 year, which can be extended up to 3 years, with access to education and training, employment, healthcare, housing and social welfare, albeit to vastly varying degrees (OECD, 2022[7]; EC, 2022[8]). Many European countries have set up programmes and adopted measures guiding education institutions on the inclusion of young refugees, building on experience from the 2015-16 humanitarian crisis (EC, 2022[8]). However, for most countries, especially for the OECD and EU countries bordering Ukraine, the magnitude of inflows of refugees is significantly larger than what education and training systems have previously experienced, in part because almost half of the refugees from Ukraine are children. This adds to the already intense pressure that the systems have been coping with due to the ongoing disruption to education caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (EC, 2022[8]). In addition, as the general mobilisation in Ukraine prevents most men aged 18 to 60 from leaving the country, about 4 in 5 adults are women (OECD, 2022[7]).

Several EU countries have taken specific measures to facilitate access to upper secondary or higher VET for Ukrainian refugees. Latvia, for instance, does not require Ukrainian minors to pass the otherwise necessary state examination prior to starting a VET programme. In Lithuania, Ukrainian students who followed a VET programme in their home country can continue their training at one of Lithuania’s VET institutes (reliefweb, 2022[9]). While Ukrainians do not have full access to integration offers in Sweden, they do have access to higher VET if they fulfil language requirements. Denmark extended eligibility for its Basic Integration Education programme (see section 4) to Ukrainians (OECD, 2022[7]). The majority of EU countries, as well as Australia and the United States, offer Ukrainians access to adult vocational training as part of job training through public employment services or adult education courses. In Canada, Ukrainians have access to vocational training through the expansion of the Settlement Programme (OECD, 2022[7]). Likewise, many EU countries, provide full access to active labour market policies and integration measures, including those that prepare for VET. For example, Germany is planning a new programme for apprenticeship-specific language training, which would be open to refugees from Ukraine.

At the international level, various efforts have also been made to facilitate access to VET. The members of ReferNet, a network of VET institutions created by the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop), compiled measures undertaken by the national governments and VET institutions to help integrate Ukrainian refugees in the host countries’ VET system (Cedefop, 2022[10]). The Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion of the European Commission compiled materials and good practices for the integration of refugees into VET systems, based on an online survey among policy makers, social partners, and VET providers (EC, 2022[11]). Existing partnerships and networks such as ongoing Erasmus+ KA1 projects (Key Action 1: Learning Mobility of Individuals) are also making VET systems more accessible to refugees from Ukraine (EC, 2022[6]).

EU countries were quick to support Ukrainian teachers, including through waivers of language or qualification requirements that would otherwise apply. For instance, in Romania, legislative changes made it possible for Ukrainian refugees having a specialised higher education diploma to become teachers. Moreover, all teachers in Romania are encouraged to teach in Ukrainian if they can and some schools now have classes taught in Ukrainian. In Latvia, Ukrainians without a teaching certification may teach refugee students younger than 18. Poland plans to create educational centres for Ukrainian students and facilitate the hiring process of Ukrainian citizens interested in becoming teacher assistants. The Czech Republic, in collaboration with the Ukrainian government, has opened classes for Ukrainian students and created a database for Ukrainian teachers and Czech volunteers. Germany and the Netherlands also have adopted policies to encourage the integration of Ukrainian teachers in VET (Cedefop, 2022[10]; reliefweb, 2022[9]; UNESCO, 2022[12]). Through the above‑mentioned Erasmus+ KA1 projects, Ukrainian teachers and trainers can teach and train in host countries, qualified staff can be sent to regions where refugees are accommodated, and institutions can invite teachers, trainers and other relevant experts, including Ukrainians, to join temporarily and draw on their expertise to support organisations hosting refugees. Online platforms and resources in Ukrainian, including professional development courses for teachers on the integration of newly arrived refugees, are expanding in the EU (EC, 2022[6]).

Moreover, guidance on how to assist Ukrainian refugees without appropriate documentation is available throughout the EU; for example, the “Erasmus+ Q-entry project” database provides information on school leaving qualifications, giving access to higher education in their national context in EU and non‑EU countries. This database, which includes information on Ukrainian qualifications, can be used to support recognition process for persons granted temporary protection. Comparison between the Ukrainian Qualifications Framework and the European Qualifications Framework (EQF) is underway. The EU Skills Profile Tool, an online tool to identify and document skills, is now available in Ukrainian.

2. The state of the Ukrainian VET system

Understanding the Ukrainian VET system is crucial for facilitating the integration of students from Ukraine in their host country’s VET system and for supporting efforts to rebuild the country with a skilled workforce.

Ukraine has a substantial VET sector

Ukraine’s educational attainment level is high, and VET is an essential part of the educational system (UNICEF, 2020[13]). In 2020, 44% of the active population had completed secondary education and 54% had completed or were enrolled in tertiary education (ETF, 2021[14]). According to the OECD World Indicators of Skills for Employment, about a third of upper secondary students in Ukraine are in vocationally-oriented programmes. In 2019, 253 900 students were enrolled in upper secondary VET schools (62% young men and 38% young women) (ETF, 2021[14]). Upper secondary VET programmes include: Level 1 programmes (one year or less), which are mostly delivered as online and part‑time programmes and focus on on-the-job learning, and Level 2 VET programmes (1.5-3 years), which grant access to tertiary education. At the short-cycle tertiary level, Level 3 VET programmes (2-4 years) lead to a junior bachelor or specialist diploma, which may be recognised towards academic bachelor’s programmes. While industry has been the most popular sector for VET, many VET students were also found in agriculture and construction (Figure 1).

Prior to Russia’s invasion, Ukraine was in the process of strengthening its VET system. Efforts included several major reforms such as the 2020-27 National VET Action Plan to modernise the VET system and decentralise VET governance. Moreover, the National Council for VET Development was established in 2021 in addition to existing Regional VET Councils. Since 2015, dual programmes similar to the apprenticeships found in Germany or Switzerland – two countries with exceptionally strong VET systems – have been gradually implemented in VET institutions (ETF, 2021[14]).

Since the invasion, the Ukraine Ministry of Education and Science has been working to maintain and rebuild VET, by resuming VET programmes and by working on projects to update VET institutions with modern machinery and equipment that will contribute to the training of skilled workers to meet needs of the national economy both in wartime and in the post-war period of rebuilding (Box 1).

Source: Adapted from the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (2019[15]), VET, https://mon.gov.ua/eng/tag/profesiyno-tekhnichna-osvita

With martial law in place, Ukraine has shifted to emergency remote teaching, a temporary learning mode that schools had already adopted in the past because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, VET institutions are advised to carry out the theoretical part of their lessons online and to postpone the practical part until after the end of martial law (School Education Gateway, 2022[16]).

As of 7 May 2022, upper secondary VET provision had been resumed remotely in 18 oblasts and partly in 7 oblasts. Short-tertiary VET (professional pre-higher education) is provided remotely and in a blended format in all 24 oblasts. Work is ongoing on the temporary displacement of professional pre‑higher and higher education institutions: more than 70 institutions and their units have been relocated (MESU, 2022[4]).

The Ukrainian Ministry of Education and Sciences (MoES) prepared a list of project proposals addressed to its international partners, indicating key educational policy priorities to minimise learning gaps of Ukrainian students. The implementation of some of these projects started already prior to the war, but was halted as resources were transferred to the country’s Armed Forces. The proposals include career guidance, admission campaigns, updating the infrastructure in VET institutions, and creating an overarching digital education ecosystem to enable easier information exchange within the education sector. As of 2021, 364 education and practical centres (EPC) have been established in VET institutions and it was planned to establish 140 EPCs in VET institutions during 2022-23 (MESU, 2022[17]).

In addition to these proposals, the MoES has held meetings with international partners to discuss further support measures. It also regularly publishes urgent educational needs on its website. The ministry has also enabled VET provision through manuals or free short courses leading to partial qualifications, guidelines for VET teachers for online learning, and measures for the internal academic mobility of VET students during the war (MESU, 2022[18]).

Source: School Education Gateway (2022[16]), Online educational resources in Ukrainian: schooling in Ukraine under adverse conditions, https://www.schooleducationgateway.eu/en/pub/latest/news/online-ed-resources-ua.htm; Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (2022[17]), Urgent Needs of Ukraine’s Education and Science, https://mon.gov.ua/eng/ministerstvo/diyalnist/mizhnarodna-dilnist/pidtrimka-osviti-i-nauki-ukrayini-pid-chas-vijni/nevidkladni-potrebi-osviti-i-nauki-ukrayini; Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (2022[4]), Overview of the current state of education and science in Ukraine in terms of Russian aggression (as of May 01 – 07, 2022), https://www.etf.europa.eu/en/document-attachments/overview-current-state-may-7-2022; Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (2022[18]), Tips For Teachers Of Vocational Schools For The Effective Organization Of Online Learning, https://mon.gov.ua/ua/news/poradi-pedagogam-proftehiv-dlya-efektivnoyi-organizaciyi-onlajn-navchannya

Many young Ukrainians aspire to skilled trades

Compared with their peers in OECD countries, Ukrainians are much clearer at age 15 about their ambitions for working life (Figure 2). Data from PISA 2018 show that career uncertainty (the inability to name the type of job expected at age 30) is very low in Ukraine for both general and VET students. Asked about their career plans, many name occupations commonly entered through VET programmes. Excluding those who are uncertain about their career plans (14%), 15% of the students (24% of boys and 5% of girls) expect to work in occupations such as skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers; craft and related trades workers; and plant and machine operators and assemblers, respectively (which correspond to the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) Level 6, 7 and 8 respectively). This level of interest is comparable to the ambitions expressed by young people in Germany and Switzerland. Looking at ISCO 7 which include the skilled trades, 9% (12% of boys and 4% of girls) anticipate working in such professions. Interest from girls in such professions is among the highest in the PISA 2018. The top 10 occupational expectations include a number of occupations that can be entered through VET (OECD, 2019[19]), such as beauticians, chefs, electronics mechanics, and mechanical machinery assemblers.

Source: Based on OECD (2019[19]), PISA 2018 Results (Volume II): Where All Students Can Succeed, https://doi.org/10.1787/b5fd1b8f-en.

3. The importance of VET provision for Ukrainians

VET is essential for rebuilding

Typically, with VET interrupted during war years, the inflow of entrants into certain professional fields is insufficient to replace skills losses and meet the needs of reconstruction. Post-war, a range of countries that did not have a historic foundation of VET, established VET schools in response to skills shortages and the need for national reconstruction after the destruction of national infrastructure (Cedefop, 2004[20]). More generally, during conflicts, the supply of skills declines due to a sharp reduction of investment and disruptions in the operation of education and vocational training. Schools, universities and training centres are destroyed or closed, and many people flee abroad, thus interrupting the construction of a country’s human capital. Shortages of skills greatly hinder later reconstruction efforts, and tend to be particularly pronounced in areas where VET is strong. The immediate post-war situation requires redesigning or updating VET systems to better reflect post-conflict needs, especially those related to reconstruction, and to be more flexible in their ability to respond to market conditions as they evolve (ILO, 2003[21]).

VET boosts labour market integration in host countries

Across a wide range of countries, graduates from upper-secondary VET have better labour market outcomes compared to those from academic upper-secondary education or people without upper secondary qualifications, at least in the short term (OECD, 2020[22]). This holds for both native and foreign‑born youth (Figure 3). Work-based learning (WBL), such as apprenticeships, is a particularly effective solution. WBL, if designed well, help ensure that learners develop skills in demand, allowing them to contribute skilled, productive labour as quickly as possible so minimising the net costs of training incurred by employers (OECD, 2018[23]). WBL also allows non-native learners to practice and develop language skills in real-world settings and provides significant new opportunities for social interaction.

Notes: ISCED 3 refers to upper-secondary education, ISCED 1-2 to primary education and lower-secondary education.

Source: Jeon, S. (2019[24]), Unlocking the Potential of Migrants: Cross-country Analysis, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, https://doi.org/10.1787/045be9b0-en.

Investment in VET for refugees is beneficial regardless of their prospects for return

One key challenge for VET provision in the context of forced displacement from Ukraine is that the duration and intensity of the war is highly uncertain, and therefore so too is the duration of stay in the host country. This uncertainty is also mirrored in policy responses, most importantly in the provision of temporary protections but also in the reluctance by some host countries to invest in integration measures, such as language training or training with longer durations.

In many cases, occupations typically entered through VET are in high demand. If refugees choose to stay, then their VET skills will be beneficial to the host country. However, Ukraine wants refugees to return, as do many Ukrainian refugees themselves – in contrast to other refugees, such as those from Syria, where return has not yet occurred in significant numbers. Therefore, skills that refugees gained through VET are likely to help in the reconstruction of Ukraine.

Given these two possibilities, investing in VET for refugees – regardless of their prospects for return – is beneficial for both the host country and for Ukraine. This dual benefit of skills building through VET should be considered in the policy responses by host countries (see next section).

Needless to say, Ukraine will need to plan on the reintegration of returnees to its VET system. Policy approaches for consideration by the Ukrainian authorities include recognition and validation of VET (both prior to and after forced migration) and foreign VET qualifications that returnees may bring back with them alongside incentivising and putting in place supportive measures to facilitate entry into, completion of, VET programmes in the context of a wartime or post-war period and provision of socio-emotional support. Such issues demand consideration within Ukraine’s recovery and reconstruction plan, taking into account possible post-war challenges, including lack of adequate VET facilities as well as teaching and employer shortages, potential discrimination facing returnees, and competition for resources and support in light of changing war-related priorities (OECD, 2020[25]; Dadush, 2017[26]).

4. Making VET systems work for Ukrainian refugees

Previous OECD work advised governments to build inclusive and flexible VET systems to support and better integrate humanitarian migrants. The OECD reviews, Unlocking the Potential of Migrants – cross-country analysis (Jeon, 2019[24]) and Germany (Bergseng, Degler and Lüthi, 2019[27]) – provide policy insights into how VET systems can adapt to more successfully integrate migrants into the VET provision of their host countries, so as to achieve better outcomes for both migrants and for economies as a whole. The below summarises the key findings, as far as they are relevant for refugees from Ukraine.

Supporting the VET journey of the newly arrived

Previous experiences of integrating humanitarian migrants provide important insights for the integration of Ukrainian refugees, now and in the future. Refugees, as other migrants, face a number of predictable challenges in navigating VET systems which can be grouped into four areas. The four barriers can be summarised as getting informed, getting ready, getting into and getting on in VET.

Countries can support the engagement of young refugees by making relatively small adjustments to their VET systems. Ultimately, such actions serve to make VET systems more flexible and inclusive in ways that work not only for young migrants, but also for other disadvantaged and vulnerable groups. This means that countries may need to take different approaches to the systemic design and delivery of the VET system and consider long-term national strategies that involve effective and efficient co-ordination and peer‑learning mechanisms across relevant stakeholders, in particular social partners. Programmes that can last over the long term and be compatible and closely connected to existing programmes are more sustainable and efficient, and easier to evaluate, compared to operating short-term, temporary programmes.

1. Getting informed: Understanding VET opportunities

Given that young refugees have different ages and different levels of interest and experience of VET, it is important for host countries to engage with students in a personalised and co-ordinated way in order to assess their needs and capabilities and to better engage them in VET. This also implies a need for upfront assessment of prior learning and skills (Jeon, 2019[24]).

Young refugees are often unfamiliar with or have a poor opinion of VET, based on experience in origin countries where VET is not popular or common. Even in Ukraine, where VET has a stronger presence than in many other origin countries, the numbers of VET students and VET institutions have gradually declined over recent years due to the lower relative status of VET compared to higher education as well as the declining population (MESU, 2019[15]; WES, 2019[28]). Familiarisation of refugees with the VET system and subsequent career opportunities requires proactive provision of personalised career guidance and mentoring services, with basic information in Ukrainian, and mobilising existing information mechanisms (Jeon, 2019[24]).

Refugee students, as the case for many youth from Ukraine, can be expected to be suffering from post‑traumatic stress due to enforced displacement, family bereavement and separation and daily material stress (Spaas, 2022[29]). In such circumstances, counselling approaches that recognise the individual student and their story before beginning to explore the right educational and training options are likely to be more effective. Examples of policies and practice include:

Career guidance with language support: In Sweden, multi-lingual, online career guides help refugees assess their own interests, skills and qualifications against different occupations. The guides were developed together with employers’ organisations, and counsellors from public employment services can assist refugees in using the guides (Jeon, 2019[24]).

Career counselling: In Denmark, career counsellors use a five-step approach to recognise the individual stories of refugee students, using creative means to explore preferences, hopes and perceived barriers within career aspirations, co-constructing a plan of action (Petersen, 2022[30]).

Career education and guidance: In Germany, refugees from Ukraine have access to the full range of career guidance provisions, which are in general well developed (Bergseng, Degler and Lüthi, 2019[27]). These include (amongst others): career guidance focusing on vocational counselling as an integral part of the curriculum in compulsory school as well as within transitional programmes, often including company visits, internships or vocational workshops; Vocational Orientation Programme which help students to explore their interests and familiarise themselves with different occupational fields; Youth Migration Services to support young people aged 12 to 27, which have recently launched a dedicated function to support young Ukrainians; career guidance for refugees from Ukraine provided by the Federal Employment Agency with its local Public Employment Services, offering counselling regarding apprenticeships and the labour market, tailored occupational information based on individual potential assessment including support up to the first year of apprenticeship.

2. Getting ready: Preparing for VET, including apprenticeships

Even if upper-secondary VET becomes a goal for young migrants, they often face a number of barriers. Effective preparatory programmes can enable smooth progression into mainstream upper secondary VET by combining language, vocational and academic learning, engaging social partners, emphasising work‑based learning (WBL) and providing career guidance. Targeted pre-vocational or pre-apprenticeship programmes that include WBL play particularly important roles, allowing students to build social networks and familiarity with the host-country education system and the labour market (Jeon, 2019[24]).

In countries where upper secondary VET provision is primarily delivered through apprenticeships, preparatory programmes can provide potential apprentice employers with greater confidence that migrant youth will contribute productively through the whole duration of their apprenticeship, so balancing out the costs to the employer of taking on the apprentice. While financial incentives to employers can influence these important cost-benefit calculations, studies of such programmes show that they often have limited impacts. (Bergseng, Degler and Lüthi, 2019[27]).

Pre-VET programmes: Pre-VET programmes can make VET more accessible for migrant youth.

Denmark’s Basic Integration Education (Integrationsgrunduddannelsen, IGU) aims to enable smooth labour market transitions with language training and work-based components. This two-year programme is offered for newly-arrived refugees aged 18-40 with a focus on adults with work experience. It offers financial incentives for both participants and their employers. IGU offers are equivalent to regular basic VET programmes, i.e. wage rates and labour rights. Being highly flexible, IGU can be linked with other programmes and there is also possibility for already-employed people to start IGU with their current employer to get appropriate qualifications (Jeon, 2019[24]). The Danish government has extended eligibility for the IGU programme to Ukrainians (OECD, 2022[7]).

Finland’s pre-vocational programme for migrants (VALMA) aims to help newly arrived learners to move on to programmes leading to upper-secondary vocational qualifications. It lasts between 6 and 12 months and provides migrants with information and guidance on different occupations and vocational studies. When migrants later apply for an upper-secondary vocational programme through a joint application system, they can receive extra points for completed preparatory education (Jeon, 2019[24]).

Switzerland offers Integration Apprenticeships, designed to facilitate enrolment in apprenticeship programmes. It combines on-the-job training or traineeships with the goal of acquiring basic competences in an occupational field and language (Jeon, 2019[24]). The Federal Council collaborates for this programme with the cantons, professional organisations and VET institutes. Around two thirds of participants continued into a regular VET programme upon completion of their pre-apprenticeship. Initiated in 2016 as a pilot to help the transition of young refugees and temporarily admitted persons with work experience or training, into VET and the labour market, it was recently renewed until 2024 (Aerne and Bonoli, 2021[31]).

Language, learning and socio-emotional support: Swedish for Immigrants (SFI) and Swedish as a Second Language (SVA) programmes help migrants acquire Swedish language competences. SFI is combined with vocational adult education, including apprenticeships, in different occupations. In some municipalities, the SFI offer is tailored to particular professions. Introductory Programmes are also available after the end of lower secondary provision. They include language programmes and are designed to prepare any students facing additional barriers to enter upper-secondary VET programmes as well as the labour market (Jeon, 2019[24]).

3. Getting in: Enabling easier access for young migrants and refugees to VET

Refugees often face barriers to entering VET. Specific challenges include relatively weak language and other skills, lack of relevant social networks, lack of knowledge about labour market functioning, as well as possible discrimination in the apprenticeship market. In addition to providing preparatory programmes that can address such common barriers (as described above), countries have responded to the challenges by offering flexible VET provision, such as modular, shorter or longer programmes – which address the cost‑benefit concerns that tend to drive employer thinking. Governments can also reassure schools and employers by allowing legal flexibility for refugee students and apprentices to enter into and complete upper-secondary VET as well as giving them permission to work for a period after completing an apprenticeship. In response to the 2015 inflow of asylum seekers, Germany introduced what is known as the 3+2 rule whereby asylum seekers are guaranteed that they will not be deported during the duration of their training and employment up to two years later, even if their asylum claim is ultimately rejected. Some countries are also promoting intermediary bodies to build contacts between young migrants and employers. Such efforts can challenge discriminatory assumptions while enabling migrants to build social capital and better understanding of employer expectations.

Changing the duration of apprenticeships: In Switzerland, a traditional upper-secondary apprenticeship lasts about three years. To increase access for all students with ‘weaker’ profiles, including refugees and migrants, the country introduced a 2+2 model. Students apply initially for a two-year apprenticeship that is less demanding. Many go on to a second two-year apprenticeship programme, so completing their upper-secondary qualification over a longer time period (Jeon, 2019[24]). Taking a similar approach, the German region of Bavaria has piloted 1+3 VET model, which allows one additional year for intensive language training in addition to the usual three-year apprenticeship. In Austria, integrative apprenticeships (IBA) are upper secondary VET programmes that support youth at risk of poor outcomes or dropout, both during work placements and at school. Participants can take an additional year or two to complete their apprenticeship, or may choose to obtain a partial qualification. Firms participating in this programme receive higher subsidies than other firms, and public resources cover additional training needed by apprentices and trainers in the firm (Bergseng, Degler and Lüthi, 2019[27]).

Introducing flexibility into vocational training: In 2017, Sweden introduced Vocational Packages, a vocational education programme intended to facilitate transition to the labour market, as part of an introductory programme at upper secondary school or as full-time study on an integrated vocational programme in municipal adult education or special needs municipal adult education. Available across a range of occupational areas, these are short courses focused on specific vocational skills leading to qualifications that are recognised in the labour market (Kuczera and Jeon, 2019[32]). These are also available for migrants.

Engaging employers: In Switzerland, training networks, consisting of companies that collaborate to offer training placements, can increase the supply of training placements and give apprentices access to diverse learning environments across multiple firms. Such initiatives are particularly useful when individual firms are highly specialised and cannot offer the full range of skills required to be trained in an occupation as part of VET. As training networks rotate or share apprentices across companies, provision of VET through these networks can address potential discrimination against apprentices and increase the work-based learning opportunities for refugees. This approach also enhances the engagement of small firms in training activities by taking care of administrative processes, including the legal aspects of training and hiring refugees.

4. Getting on: Supporting the completion of VET

Refugee students tend to be less successful in completing upper-secondary VET than their native peers. Higher dropout rates are linked to lack of knowledge about the functioning of the labour market and the VET system, weaker language and other skills, difficulty in securing training placements for work-based learning, and inadequate connections between schools and workplaces, in addition to emotional and psychological stress. Personalised support through the use of mentors and coaches as well as other support mechanisms to increase connections between schools and workplaces during VET can enhance the outcomes of migrant students and all students at risk of dropout (Jeon, 2019[24]). The majority of OECD countries have specific support measures in this respect (OECD, 2021[33]). Some particularly relevant examples are the following:

Training assistance: In Germany, the public employment service offers Assisted Apprenticeship and Training Assistance to support all learners (including migrants) at risk of dropout during apprenticeship programmes. Assistance includes remedial education and support with homework and exams, which helps to overcome learning difficulties. Socio-pedagogical assistance (including mentoring) is also available. Also, the German Federal Ministry of Education initiated Prevention of Training Dropouts, where voluntary experts (e.g. retired professionals) counsel apprentices who are experiencing difficulties and are considering terminating their training. Germany also offer grants for apprentices who are struggling financially (Bergseng, Degler and Lüthi, 2019[27]).

Targeted and personalised training: In Switzerland, apprentices in two-year initial VET programmes (EBA) are entitled to publically-funded individual coaching and remedial courses, mostly to tackle weak language skills, learning difficulties or psychological problems. Most coaches are former teachers, learning therapists or social workers, and receive targeted training in preparation for their job (Jeon, 2019[24]).

Employer support: In Germany, apprenticeship employers must belong to a Chamber of Commerce or Crafts and many Chambers help employers in dealing with unexpected challenges encountered among refugee apprentices. Legal and practical training is available, as are employer networks to facilitate peer learning (Bergseng, Degler and Lüthi, 2019[27]).

Supporting Ukrainian VET teachers in their host country

Data from a variety of sources suggest that a significant share of the refugees from Ukraine were previously employed in the education system. While both the exact share and the proportion of VET teachers among them are unknown, they are likely to account for a non-negligible number. Dedicated ad-hoc teacher training for Ukrainian teachers and fast-track assessment and recognition, along with the waiver of language requirements, could enable them to quickly pursue their profession in the host country.

Requirements for the recruitment of VET teachers vary across countries – with some countries imposing stricter requirements than others. For example, in those countries where VET teachers are civil servants or permanent employees (e.g. Austria, Germany, Japan and Korea), VET teachers have to pass one or more teaching qualification exam, for which they have to complete initial teacher education and training (including practical training in some cases). By contrast, in some countries, VET teachers can start teaching without a teaching qualification, but they are required or encouraged to obtain the relevant qualification while working. They are hired based on an occupational qualification or their prior work experience. For example, in Denmark, VET teachers can achieve the required teaching qualification while teaching. The same is true in some states in the United States. In England (United Kingdom), while there are no legal qualification requirements for teaching in VET. In practice, providers often expect VET teachers – who frequently come from industry – to have, or be working towards, a pedagogical diploma. In a number of countries, there are also language requirements to be met (OECD, 2021[34]).

Such entry requirements, as well as language barriers more generally, may impede refugee teachers from working in the host country. Refugees often do not have appropriate documents to prove their skills and qualifications. Even when there is a possibility to retrain, it is often a lengthy and costly process and not always easy to combine with family obligations. Therefore, recognition of prior learning for qualified migrant workers or those with relevant teaching experience can facilitate their entry into VET teaching (UNESCO, 2018[35]). For instance, Sweden established a fast-track scheme during the 2015-16 humanitarian crisis to enable migrants who have relevant teaching experience to begin teaching quickly while meeting pedagogic standards. This is done through an initial assessment of the skills and qualifications earned in their home country which are topped up with the specific host country skills or other skills needed to become a teacher (OECD, 2021[34]; OECD, 2016[36]). The University of Potsdam in Germany offers a Refugee Teachers Programme, which includes German language lessons, teacher training, and classroom practice (Universität Potsdam, 2022[37]). As mentioned in section 1, a number of countries have waived language and other requirements to allow teachers from Ukraine to pursue their profession in the host country.

Creating learning environments where Ukrainian teachers can teach Ukrainian refugee students can be helpful, especially in a situation where return and reintegration is desired. There is also some research that suggests benefits for migrant students to being able to use and develop both their mother tongue and the national language of their host country. Mother tongue tuition can improve students’ cognitive development and second language literacy as well as their self-esteem and understanding of cultural identity (UNESCO-IIEP, 2022[38]; Cerna, 2019[39]). Indeed, mother-tongue education has special relevance in the current context, given teacher shortages in host countries, lack of host-country language skills by refugees from Ukraine, and the intention of a temporary stay with the hope of return and reintegration for many.

As mentioned above, measures have been put in place in several European countries or through international networks to support the hiring and training VET teachers. However, further effort is needed to train and recruit Ukrainian teachers in VET for a smoother transition during and after the war. Even before the invasion, Ukraine had a shortage of VET teachers: in 2019, more than 3 000 positions for VET teaching staff were unfilled, including VET trainers (masters of vocational training) (ETF, 2021[14]).

The Ukrainian refugee crisis also highlights the desirability of all teacher training programmes to address challenges encountered in effectively supporting increasingly heterogeneous student populations. PISA data shows that the percentage of 15-year-old students with migrant parents grew from 10% to 13% between 2009 and 2018, on average across OECD countries. Initial teacher training programmes can include provision aimed at preparing teachers to work in multi-cultural and multi-lingual settings, so optimising the effectiveness of preparatory and VET programmes. On average across the six OECD countries/regions with available data (see Figure 4), teaching in a multicultural learning environment (45% of VET teachers) and cross-cultural communication (37%) are one of the most pressing training needs for VET teachers (OECD, 2021[34]). Indeed, training needs in these areas are perceived higher by VET teachers than by general education teachers.

Note: VET teachers are those who reported in OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) that they were teaching practical and vocational skills in the survey year in upper secondary programmes (ISCED 3), regardless of the type of school where they teach. The bars represent the unweighted average of the six countries/regions. Data for the individual countries refer to VET teachers only. The data include Alberta (Canada), Denmark, Portugal, Slovenia, Sweden and Turkey.

Source: OECD (2021[34]), Teachers and Leaders in Vocational Education and Training, dx.doi.org/10.1787/59d4fbb1-en.

Making effective use of digital technologies in VET

There is a strong need to harness digital technologies and pedagogies in response to the challenges raised by Russia’s large-scale aggression against Ukraine. As noted, physical infrastructure has been severely damaged and both VET teachers and students have been widely dispersed by the war. For Ukrainian refugees, online learning provides an important means of maintaining education and training and may potentially supplement in-person provision enabled by host countries.

For VET students, digital technologies can potentially provide many benefits. They can increase (i) access to career guidance and educational content (e.g. through videos that can be watched on multiple occasions), (ii) enable interactions with employers, and (iii) through virtual, augmented or mixed reality systems, allow students to practice technical skills. For refugees with a high likelihood of returning to their home country, as currently the Ukrainian refugees, portable skills certificates – such as through blockchain technology and micro-credentials – can also be enabled through digital technologies.

Such online learning can offer provision that is more accessible, safer, more time- and cost-effective, and more appealing ways of learning and assessing practice-oriented skills. Technological innovation in digital learning has been accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, during lock-downs students in many countries struggled to engage with digital learning provision in part through challenges in accessing provision due to skills limitations and lack of access to appropriate devices and learning environments.

Prior to the invasion, Ukraine was putting efforts into increasing digital education. In 2019, a survey revealed that the level of digital skills of Ukrainians was comparatively low: 53% of the population (aged 18-70) had low digital skills or no such skills at all (ETF, 2021[14]). In the response to the need for stronger digital skills, the Ministry of Digital Transformation (DT) was established in 2019, and DT Officers were appointed in 2020 at the Ministry of Education and Science (MoES) to drive the digital transformation in education. In 2021, the Directorate of Digital Transformation in Education was established within the MoES. Around this time, over 90 projects were launched, including EU initiatives such as the SELFIE – a free, customisable tool to help schools to enhance capacity to use digital technologies in learning. Moreover, the ILO, in collaboration with the MoES, developed e-learning solutions for VET institutes focusing on the hospitality, mechanical, electrical, and garment sectors. Some of these solutions include a national e-learning platform to make digital learning materials more accessible, e-courses for instructors on e-learning, teacher training, or interactive training modules for students (ILO, 2022[40]).

Digital tools can also enable students from Ukraine to maintain links with the education system in their origin country. Indeed, this is commonly the case for primary and secondary general education, where students continue to receive education in Ukrainian, often by the same teachers as they had prior to the invasion, in spite of displacement.

While online or hybrid learning has been less common in VET in general or compared to academic programmes because of its practice-oriented nature, many countries have already introduced, piloted or used digital technology in VET (Education Scotland, 2021[41]; Briggs, López and Anderson, 2021[42]). For example, the Flemish Employment and Vocational Training Service helps residents of Flanders find jobs and take vocational training, by using machine learning (Amazon Web Services, 2021[43]). A virtual reality training programme for 300 future electro-technicians was recently introduced in five vocational schools in North Macedonia (ILO, 2022[44]). In addition, countries rapidly increased the delivery of career guidance programmes through digital technologies during the pandemic, including online career talks by guest speakers, virtual job fairs and work placements. These technologies and the lessons learnt could support Ukraine refugees. Several universities offer free online courses and scholarships for Ukrainians to continue their degree programmes, including those internally displaced by the war. For example, the University of the People in the United States offers associate and bachelor’s degree programmes in business administration, computer science, and health science for Ukrainian students (UOP, 2022[45]).

5. Conclusion

VET systems, in both Ukraine and host countries, have an important role to play in helping to support Ukrainians who were forced to flee their homes following Russia’s unprovoked aggression. By its very nature, VET is well placed to support not only labour market integration in host countries, but also the further building of skills which will be required in the reconstruction of Ukraine. Given these strengths, VET should be an integral part of host-country’s reception policies for those forcedly displaced from Ukraine.

However, for VET systems to harness this potential, a number of barriers need to be addressed. Beyond host-country specific skills, these relate to information about VET, preparation for VET, removing barriers for access – including lack of networks, discrimination, and certainty regarding length of stay – and tackling the issue of drop-out. Ultimately, in responding to these challenges, VET systems in host countries will become more inclusive – to the benefits not only of Ukrainians and other migrants, but also for disadvantaged groups at large. Finally, considering the prospect of return, Ukraine will need to sustainably reintegrate returnees, including VET students and graduates, through incentivising apprenticeships, recognising and validating diverse education, training and employment paths that returnees have pursued in host countries. If refugees are well integrated in VET systems in their (temporary) host countries, the experiences of returnees will contribute to strengthening VET in Ukraine during reconstruction and beyond.

Further reading

[31] Aerne, A. and G. Bonoli (2021), “Integration through vocational training. Promoting refugees’ access to apprenticeships in a collective skill formation system”, Journal of Vocational Education & Training, pp. 1-20, https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2021.1894219.

[43] Amazon Web Services (2021), AWS Partner Story: VDAB & Radix.ai, https://aws.amazon.com/partners/success/vdab-radix-ai/.

[27] Bergseng, B., E. Degler and S. Lüthi (2019), Unlocking the Potential of Migrants in Germany, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/82ccc2a3-en.

[42] Briggs, A., D. López and T. Anderson (2021), Online Career and Technical Education Programs during the Pandemic and After: A Summary of College Survey Findings, Urban Institute, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104193/online-career-and-technical-education-programs-during-the-pandemic-and-after_1.pdf.

[10] Cedefop (2022), What Europe is Doing for Ukraine Refugees, https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news/what-europe-doing-ukraine-refugees.

[20] Cedefop (2004), Towards a History of Vocational Education and Training (VET) in Europe in a Comparative Perspective, https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/5153_1_en.pdf.

[39] Cerna, L. (2019), “Refugee education: Integration models and practices in OECD countries”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 203, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a3251a00-en.

[26] Dadush, U. (2017), The Economic Effects of Refugee Return and Policy Implications, https://www.bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/RefugeeReturnOCPPC-1.pdf.

[6] EC (2022), Joint ACVT/DGVT webinar on the integration of Ukrainian refugees, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=25478&langId=en.

[8] EC (2022), Policy guidance on supporting inclusion of Ukrainian refugees in education, European Commission, https://www.schooleducationgateway.eu/downloads/files/news/Policy_guidance_Ukraine_schools.pdf.

[11] EC (2022), Preliminary results: Survey on integration of Ukrainian refugees in Vocational Education and Training (VET), https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=89&newsId=10223&furtherNews=yes.

[41] Education Scotland (2021), Remote learning in Scotland’s Colleges, https://education.gov.scot/media/ddkng0mn/scotlands-colleges-main-report.pdf.

[14] ETF (2021), Ukraine - Education, training and employment developments, https://www.etf.europa.eu/en.

[48] García, O. (2009), Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective, Wiley-Blackwell, http://ISBN: 978-1-405-11994-8.

[44] ILO (2022), “Virtual” is now a TVET training reality in North Macedonia, https://www.ilo.org/budapest/whats-new/WCMS_840380/lang--en/index.htm.

[40] ILO (2022), Strengthening digital TVET in Ukraine, https://www.ilo.org/skills/Whatsnew/WCMS_836777/lang--en/index.htm.

[21] ILO (2003), Jobs after war: A critical challenge in the peace and reconstruction puzzle, https://www.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/2003/103B09_340_engl.pdf.

[24] Jeon, S. (2019), Unlocking the Potential of Migrants: Cross-country Analysis, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/045be9b0-en.

[5] KSE (2022), Damanges to Ukraine’s infrastructure. May 10, https://kse.ua/russia-will-pay/.

[32] Kuczera, M. and S. Jeon (2019), Vocational Education and Training in Sweden, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/g2g9fac5-en.

[4] MESU (2022), Overview of the current state of education and science in Ukraine in terms of Russian aggression (as of May 01 – 07, 2022), Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, https://www.etf.europa.eu/en/document-attachments/overview-current-state-may-7-2022.

[3] MESU (2022), saveschools, Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, http://saveschools.in.ua/.

[18] MESU (2022), Tips for teachers of vocational schools for the effective organization of online learning, Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, https://mon.gov.ua/ua/news/poradi-pedagogam-proftehiv-dlya-efektivnoyi-organizaciyi-onlajn-navchannya.

[17] MESU (2022), Urgent needs of ukraine’s education and science, Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, https://mon.gov.ua/eng/ministerstvo/diyalnist/mizhnarodna-dilnist/pidtrimka-osviti-i-nauki-ukrayini-pid-chas-vijni/nevidkladni-potrebi-osviti-i-nauki-ukrayini.

[15] MESU (2019), Vocational Education and Training, Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, https://mon.gov.ua/eng/tag/profesiyno-tekhnichna-osvita.

[1] OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report March 2022: Economic and Social Impacts and Policy Implications of the War in Ukraine, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4181d61b-en.

[7] OECD (2022), Rights and Support for Ukrainian Refugees in Receiving Countries, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/09beb886-en.

[33] OECD (2021), Young People with Migrant Parents, Making Integration Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6e773bfe-en.

[34] OECD (2021), Teachers and Leaders in Vocational Education and Training, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/59d4fbb1-en.

[22] OECD (2020), “Smooth transitions but in a changing market: The prospects of vocational education and training graduates”, in OECD Employment Outlook 2020: Worker Security and the COVID-19 Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/7393e48f-en.

[25] OECD (2020), Sustainable Reintegration of Returning Migrants: A Better Homecoming, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5fee55b3-en.

[19] OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Results (Volume II): Where All Students Can Succeed, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b5fd1b8f-en.

[23] OECD (2018), Seven Questions about Apprenticeships: Answers from International Experience, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264306486-en.

[36] OECD (2016), Working Together: Skills and Labour Market Integration of Immigrants and their Children in Sweden, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264257382-en.

[30] Petersen, I. (2022), “Existential career guidance for groups of young refugees”, International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-022-09535-1.

[9] reliefweb (2022), Mapping host countries’ education responses to the influx of Ukrainian students, https://reliefweb.int/report/ukraine/mapping-host-countries-education-responses-influx-ukrainian-students.

[16] School Education Gateway (2022), Online educational resources in Ukrainian: schooling in Ukraine under adverse conditions, https://www.schooleducationgateway.eu/en/pub/latest/news/online-ed-resources-ua.htm.

[29] Spaas, C. (2022), “Mental Health of Refugee and Non-refugee Migrant Young People in European Secondary Education: The Role of Family Separation, Daily Material Stress and Perceived Discrimination in Resettlement”, Vol. 51, pp. 848-870, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01515-y.

[12] UNESCO (2022), Ukraine: UNESCO mobilizes support for learning continuity, https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/ukraine-unesco-mobilizes-support-learning-continuity.

[35] UNESCO (2018), Teaching amidst conflict and displacement: persistent challenges and promising practices for refugee, internally displaced and national teachers, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000266080.

[38] UNESCO-IIEP (2022), Language of instruction, https://policytoolbox.iiep.unesco.org/policy-option/language-of-instruction/.

[2] UNHCR (2022), Ukraine Refugee Situation, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine.

[13] UNICEF (2020), Ukraine - VET institutions, https://www.unicef.org/ukraine/media/5746/file/UNICEF_vocational2.pdf.

[37] Universität Potsdam (2022), Refugees Welcome - Angebote für Geflüchtete, https://www.uni-potsdam.de/de/international/incoming/refugees-welcome.

[47] University of the People (2022), University of the People Opening All Its Courses to Ukrainian Students for Free, https://www.uopeople.edu/about/worldwide-recognition/press-releases/university-of-the-people-opening-all-its-courses-to-ukrainian-students-for-free.

[45] UOP (2022), University of the People Opening All Its Courses to Ukrainian Students for Free, https://www.uopeople.edu/about/worldwide-recognition/press-releases/university-of-the-people-opening-all-its-courses-to-ukrainian-students-for-free.

[28] WES (2019), Education in Ukraine, https://wenr.wes.org/2019/06/education-in-ukraine.

[46] Wool, H. and L. Pearlman (1947), Recent Occupational Trends: Wartime and Postwar Trends Compared: An Appraisal of the Permanence of Recent Movements, Monthly Labor Review 65, no. 2 (1947): 139–47, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41831304.

Contact

Shinyoung JEON (✉ Shinyoung.Jeon@oecd.org), VET and Adult Learning, OECD Centre for Skills

Thomas LIEBIG (✉ Thomas.Liebig@oecd.org), International Migration Division, OECD Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs

Anthony MANN (✉ Anthony.Mann@oecd.org), Student Aspiration and Experience, OECD Directorate for Education and Skills