Recognition of Prior Learning for Ukrainian Refugee Students

A large percentage of refugees from Ukraine are highly qualified, leading to unique challenges and pressures on Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) policies and practices.

‘Equivalency issues with Ukrainian qualifications’ was the second most frequently reported barrier to the enrolment of Ukrainian students in higher education systems (after language), according to the OECD (2023[1]) survey on Ensuring continued learning for Ukrainian refugee students.

Countries across the OECD have taken a wide variety of exceptional measures, such as extending application deadlines and introducing fee waivers, regarding their RPL policies in order to ease the transition of Ukrainians into new educational institutions and labour markets.

For the large percentage of Ukrainian refugees who intend to return to Ukraine in the future, policies and co-operation between countries regarding the recognition of qualifications obtained in host countries will also need to be considered.

Background and key issues

Ensuring continued learning for Ukrainian refugees is an ongoing challenge which host countries around the world must continue to monitor and address. Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has caused the forced displacement of millions of Ukrainians across the world. As of June 2023, more than 6.3 million Ukrainian refugees have been recorded globally, with an estimated 4.9 million currently registered in OECD countries (OECD, 2023[2]; UNHCR, 2023[3]).The United Nations estimates that around 40% of these refugees are children and young people, who are now in need of protection, care and support across several different areas, including education. Although many Ukrainians intend to return to Ukraine in the medium-long term (UNHCR, 2023[4]), supporting their continued learning in the meantime is vital for their wellbeing and future prospects.

Many Ukrainian refugees hold tertiary education degrees or incomplete qualifications due to study disruptions. The latest data show that 76% of women and 71% of men who have fled Ukraine have completed higher education qualifications (BA/BSc and above), while 5.9% of the women and 8% of the men have incomplete higher education qualifications (Perelli-Harris et al., 2023[5]). A large number are also of secondary school age and may be intending to enlist in higher education programmes where possible.

Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) is an emerging challenge in response to the influx of Ukrainian refugees. With the prolongation of Russia’s war of aggression, and the influx of highly qualified Ukrainian refugees, RPL has emerged as a key challenge with regard to the inclusion of Ukrainians into education systems and labour markets. RPL refers to processes that help recognise and formalise an individual’s previous qualifications and skills in a new system. RPL allows migrants and refugees to have their skills, work experience and formal qualifications formally recognised and equalised in a new country, allowing them to continue their studies or career in their chosen field (Global Education Monitoring Report, 2018[6]). A survey by the European Network of Information Centres (ENIC) conducted in late 2022 and early 2023 found that the top five professions for which professional recognition is sought by Ukrainian refugees are medical doctors, teachers, economists, dentists and engineers (ENIC - NAIC, 2023[7]).

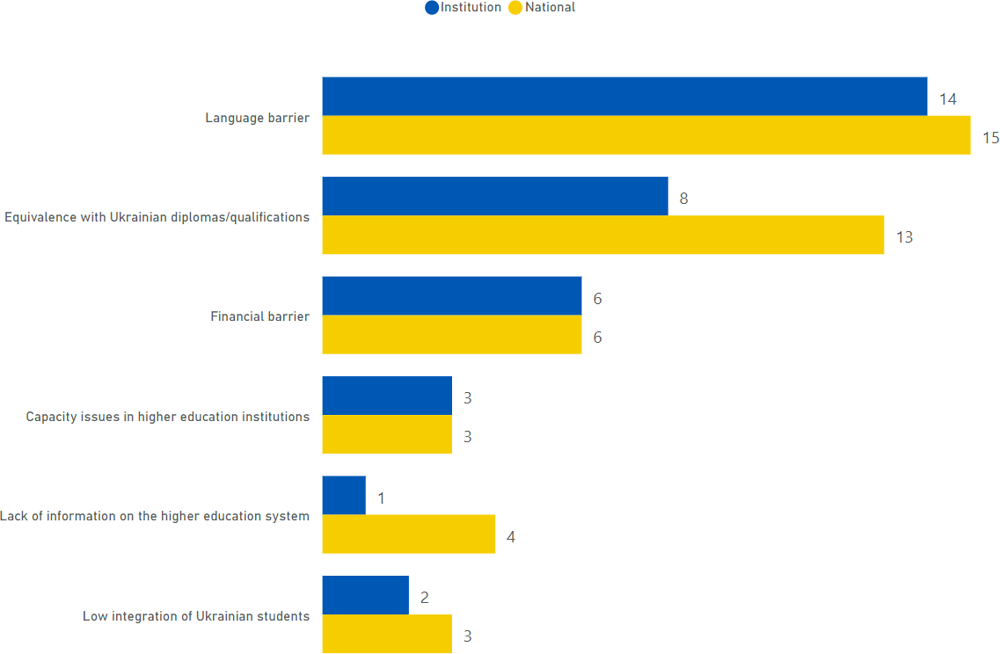

The OECD (2023[1]) survey on Ensuring continued learning for Ukrainian refugee students identified that one of the key barriers to enrolling in tertiary education is equivalency issues with Ukrainian qualifications, with 8 countries selecting it as a barrier at institutional level and 13 as a barrier at national level, This occurs despite Ukraine being a member of the Bologna process, which facilitates the process for European students to study in, and transition between, different universities across Europe through mechanisms such as the establishment of the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS), and the encouragement of degree structure harmonisation across participating countries.

The importance of reviewing RPL policies and practice

RPL can be a lengthy and complicated process for refugees. It is common for refugees, who have had to leave their homes in difficult and chaotic circumstances, to not have all the required supporting documents for RPL processes. This can be problematic, since many universities and higher education systems do not have adequate processes in place to manage such cases (Domvo, 2022[8]). Furthermore, even when individuals have their supporting documents, many institutions are not equipped to accept these, and so refugees must go through complex administrative processes to have their qualifications recognised, which sometimes come with financial costs. Research from 2018, prior to the arrival of Ukrainian refugees, identified RPL as one of the main barriers preventing refugees from entering universities in Europe (Marcu, 2018[9]). Regarding the recognition of formal credentials, the best-case scenario is that the candidate’s qualifications are accepted as equivalent to one in the host country. However, it is more likely that the recognition process identifies what the candidate is missing, and in turn leads to demands for supplementary education and/or examinations before a fully equivalent qualification can be awarded (Andersson, 2021[10]).

The 1997 Lisbon Recognition Convention stipulates that European countries’ policies and practices regarding RPL should be fair and quick, even when refugees are unable to provide supporting documents. However, research using data from 2018 found that most European countries have not fully implemented these recommendations so far (Domvo, 2022[8]). A recent report by the European Commission identified that 17 European countries have failed to make changes in line with the Lisbon Convention, despite it being a legal requirement (European Commission, 2022, p. 14[11])

Countries in the European Union (EU) have been asked to be more flexible in their RPL policies for Ukrainian refugees. Following Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine in February 2022, the EU requested that countries react in a “flexible” way and to reduce formalities regarding the recognition of Ukrainian qualifications to the minimum (European Commission, 2022[12]). This should entail, for example, accepting scanned copies of certificates or machine translations as opposed to human certified translations, making exceptions for certain missing documentation and waiving associated fees. In cases where additional exams need to be taken, host states are advised to consider speeding up the exam processes. A full guide for countries on the “fast-track” recognition of Ukrainian academic qualifications was published by the European Commission in 2022 (European Commission, 2022[13]).

Findings from the OECD (2023) survey on Ensuring continued learning for Ukrainian refugee students

The OECD launched a survey in February 2023 which collected data about the barriers and measures taken regarding the enrolment of Ukrainian refugees in national education systems. The OECD (2023[1]) survey on Ensuring continued learning for Ukrainian refugee students, asked countries at system level to report on the existing barriers to the enrolment of Ukrainian refugees in education, and the measures taken to support their continuation of education, across every level of education from early childhood to tertiary. In total, 28 countries responded, including countries outside of the EU: Israel, New Zealand and the United States.

The survey found that ‘Equivalence with Ukrainian diplomas/qualifications’ was the second most frequently reported barrier for enrolling Ukrainians in tertiary education, after language (see Figure 1). This indicates that existing RPL procedures are not adequate for ensuring a timely re-uptake of tertiary education for Ukrainian refugees.

Note: 17 countries responded to this section of the survey. ‘Institution’ refers to barriers faced at individual institutional level, whereas ‘national’ refers to barriers faced across national level.

Source: OECD (2023[1]) survey on Ensuring continued learning for Ukrainian refugee students

Policy Responses

Host countries and international organisations have implemented diverse measures to secure ongoing education and learning opportunities for Ukrainian refugees. RPL measures have brought increased flexibility in accepting Ukrainian qualifications, improved co-ordination for recognising formal credentials, and provided administrative support, among other benefits.

The ENIC-NARIC network and centres are an important part of RPL procedures in European countries. European countries who answered the OECD (2023) survey reported working with ENIC-NARIC centres (European Network of Information Centres in the European Region - National Academic Recognition Information Centres in the European Union). ENIC-NARIC networks represent an ongoing collaboration between national centres on academic recognition of qualifications in a total of 55 countries, including Ukraine. It operates under the principles of the Lisbon Recognition Convention (1997), and works in collaboration with UNESCO, the Council of Europe and the European Commission. Their goal is to provide information to individuals, educational institutions, employers and governments on the recognition of diplomas and periods of study obtained abroad. In reaction to the war, ENIC-NARIC created a website with numerous resources dedicated to providing information about Ukrainian qualifications and their equivalents. The resources include links to agencies and databases directly from Ukraine, such as the Ukrainian Qualifications Database, which includes over 300 examples of Ukrainian higher education qualifications, and the Unified State Electronic Database on Education, which verifies credentials issued by institutions in Ukraine. It also includes relevant reports by the ENIC-NARIC networks, including UNESCO and the European Commission, and links to further international resources such as the European Students’ Union webpage on “Help for Ukraine” (ENIC - NAIC, 2023[7]).

A large increase in Ukrainian applications has been recorded by ENIC centres since 2022. The report, Recognition of Ukrainian qualifications in 2022-2023, combines data from two surveys conducted in the NARIC network (November 2022) and the ENIC-NARIC networks between February and March 2023 (ENIC - NAIC, 2023[7]). The data found that 35 centres reported seeing an influx of applications for Ukrainian qualification holders from the past year. Specifically, approximately 24 000 applications were made since February 2022. It is reported that the high volume of applications has lengthened application timelines even though the expertise on Ukrainian qualifications was already available. The top three challenges reported by countries in the recognition of Ukrainian qualifications were missing documents, language barrier and lack of information on the education institutions/provider. Among several actions they will take to combat this, they plan to enlist Slavic language region specialists in the ENIC-NARIC networks, who will help with information exchange and aim to deepen collaboration with experts within the networks (ENIC - NAIC, 2023[7]).

Policies and practices surrounding RPL have also been implemented at governmental and institutional level. A brief overview of situational updates in some EU countries are reported below.

In Belgium, the Wallonia-Brussels Federation reported that certain Ukrainian diplomas are recognised as temporarily equivalent to the Certificate of Higher Secondary Education (CESS) which allows entrance to tertiary education. Furthermore, holders of temporary protection status benefit from free procedural fees for any form of equivalence requested.

France reported in the OECD (2023[1]) survey that equivalence difficulties have been prominent in medical, health, architecture and related disciplines which lead to licenced professions. For other cases, Ukrainian students benefit from the Bologna process. A special process for foreign students with incomplete medical studies was established in 2019, where upon evaluation of their previous studies, students can enter the year in which they finished their medical studies.

Hungary has extended their university application processes to be held open for the whole academic year, in order to be more flexible in accommodating Ukrainian arrivals. A renewed equivalence agreement was also set up with the Ukrainian authorities.

In the majority of cases, Ukrainian citizens in Lithuania can pursue education and employment without the need for official validation of their educational background or credentials. However, there are situations where formal recognition becomes essential to access particular job opportunities or further studies, such as medicine. If an individual has already completed certain semesters and wishes to continue their education, the acknowledgement of their academic periods will be managed by the university or college they opt for. Ukrainian citizens have the flexibility to have this done at any higher education institution. For architects and civil engineers looking for employment, a more flexible applications process has been adopted, which minimalises formalities and accelerates the process to one month.

In Luxembourg, Ukrainians who have completed at least one year of study at a Ukrainian university can have their study year recognised as equivalent and can apply to a study programme at the University of Luxembourg. Ukrainian students can demonstrate their language skills via interview rather than needing a certificate, and there is flexibility regarding the type of certificates required to prove language skills. Ukrainians can also submit their study diplomas and transcripts without certified translations. To facilitate the process further, the university has a student officer who can answer questions and provide support to students. For those who have completed secondary studies in Ukraine, they can follow an English‑language programme to obtain a University Studies Access Diploma (Diplôme d'accès aux études universitaires) which gives them access to higher education in Luxembourg.

In Spain, a separate accreditation process is applied to Ukrainian diplomas which is done in collaboration between the Ukrainian embassy and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Spanish government also provides instructions on how to certify previous Ukrainian diplomas and qualifications on the website of the Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migration, both in Spanish and in Ukrainian. Furthermore, applicants under temporary protection status benefit from accelerated processing times for equivalence requests.

In alignment with the Lisbon Convention, the Council of Higher Education in Republic of Türkiye accepts and assesses Ukrainian qualifications even in the case of missing documents. Assessment of Ukrainian qualifications is also being done at national level using alternative tools if it is not possible to validate the qualification through the Ukrainian authorities. For those without an original certificate, the equivalence process will still proceed if the copy of documents is presented with an official approval from the Ukraine Embassy. Ukrainian students are also eligible for a placement test when required, in accordance with the Equivalency Regulation. This approach ensures that Ukrainian students have a fair chance to pursue their education in Türkiye despite potential obstacles in validating their qualifications.

Supporting RPL for vocational education and training (VET)

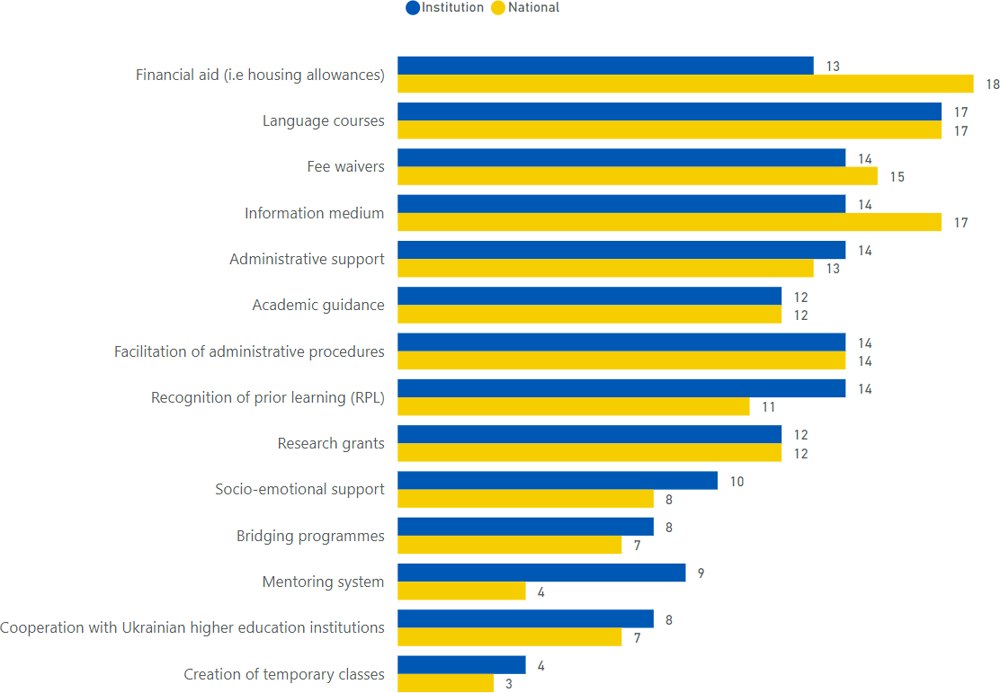

Vocational Education and Training (VET) is an important educational sector in Ukraine. In 2020, a third of upper secondary students in Ukraine were enrolled in vocational programmes (OECD, 2022[14]). In addition to wanting to continue their interrupted studies, some Ukrainian refugees may want to enrol in VET programmes in their host countries since a more practical-orientated training can minimise language barriers which they might be facing (OECD, 2022[14]). However, Ukrainian students may face barriers to access VET programmes in their host societies. In particular, the recognition of skills and prior qualifications can be a challenge. RPL was a highly reported response taken by countries in the OECD (2023[1]) survey (see Figure 2).

Note: 22 countries responded to this section of the survey. ‘Institutional’ refers to measures taken at institutional level, such as private educational institutions, whereas ‘national’ refers to measures taken across national level.

Source: OECD (2023[1]) Survey on Ensuring continued learning for Ukrainian refugee students

Measures to upscale RPL in the VET sector varied between countries. In England, for example, the UK European Network Information Centre (ENIC) researched how courses, levels and years of study in Ukraine compare to those in the UK’s education system. They also created a service where Ukrainians can apply for a ‘Statement of Comparability’ proving their level of education without having to take additional exams. In Lithuania, policies regarding admissions to VET institutions have been adjusted to ensure that Ukrainian VET students can continue their education and training in the same or similar programmes. Estonia has implemented policies for Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) at both national and institutional level. These include the Estonian Academic Recognition Information Centre for national‑level recognition and an institutional RPL system called VÕTA, which evaluates individuals' past studies and work experience.

Further support for Ukrainian students

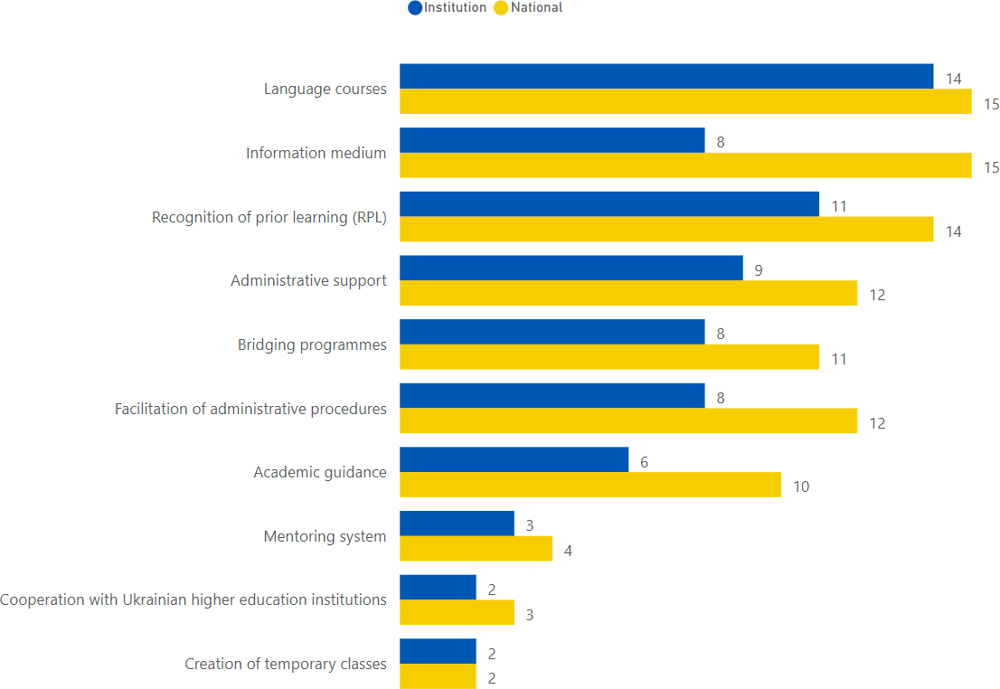

RPL is not the only barrier Ukrainian refugees are facing in accessing education. As visible in Figure 1, countries and systems are also concerned with barriers such as language, lack of information on how to enrol, financial barriers and capacity issues in higher education institutions. The OECD (2023[1]) survey asked countries to report what measures they were taking to tackle these barriers. The results can be found in Figure 3 below. Recognition of prior learning was frequently reported at institutional level and less at national level, most likely due to the high autonomy tertiary education facilities have over their admissions procedures.

Financial support, including scholarships, fee waivers and housing and transport subsidies, were common measures reported by countries. For example, in the Wallonia-Brussels Federation, EUR 2 345 000 was allocated to strengthen the provision of French as a foreign language courses for the academic year 2022-23. In Denmark, Ukrainian refugees are exempt from paying tuition fees on full time higher education courses. They can also apply for the Danish State Educational Grant and Loan Scheme for monthly financial aid. In November 2022, the Spanish Ministry of Universities granted EUR 2.6 million to universities for measures to support Ukrainian students. In Estonia, Ukrainian students are exempted of application fees, and additional funds were allocated to higher education institutions to offer fee waivers. In England, the government provided GBP 4 million of additional funding to support Ukrainian students who face financial difficulty because of the war, and they are also eligible to access the UK government student finance schemes. In Romania, Lithuania and Slovenia, Ukrainian students also benefit from scholarships and free tuition fees. In the United States, several universities, such as the University of Chicago, are providing full tuition scholarships to students affected by the war in Ukraine as well as additional support programming.

Note: 25 countries responded to this section of the survey. Intuition refers to policies undertaken by independent institutions such as private universities. 27 OECD countries responded to this (OECD, UNHCR, 2018[15])question.

Source: OECD (2023[1]) survey on Ensuring continued learning for Ukrainian refugee students

Countries have also supported Ukrainian researchers and professors whose careers have been disrupted. The Latvia-Ukraine bilateral programme offers funding of up to EUR 20 000 per year for joint research projects of up to two years. There are also research fellowships available for Ukrainian researchers who are not employed by scientific institutions. In Finland, higher education institutions and research institutes have arranged fixed-term researcher positions for Ukrainian researchers and research‑related work. In addition, the Finnish National Agency for Education’s scholarship programme, EDUFI Fellowship for doctoral researchers from Ukraine, provides doctoral researchers who have fled Ukraine the opportunity to continue their academic work in Finland and supports the reconstruction of higher education in Ukraine. In Canada, the Science for Ukraine programme offers fellowships, placements and other opportunities for Ukrainian graduate students and researchers (Science for Ukraine, 2023[16]).

Employers also play a vital role in facilitating the successful inclusion of refugees into the workforce. Employers are encouraged to look beyond the recognition of formal qualifications and look at alternative ways of assessing skills, such as requesting character references and testimonials from sources such as social workers and mentors, and assessing skills through demonstrations (OECD, UNHCR, 2018[15]). Employer associations can also contribute to this effort by encouraging the provision of short-term paid internships, and by promoting knowledge sharing among employers regarding tools for skills verification (OECD, UNHCR, 2018[15]). A notable example from Germany showcases innovative practices in assessing informal skills among recent refugee arrivals. The German public employment service has developed computer-based skills identification tests known as "MYSKILLS" to evaluate refugees' informal skills (German Federal Employment Agency, 2023[17]). These tests use videos demonstrating standard job tasks, requiring candidates to identify errors or sequence tasks correctly. Developed in collaboration with employers' associations to ensure alignment with job requirements, these assessments have been expanded to encompass various professions and languages, contributing to a more effective integration of refugees into the German workforce. Such initiatives serve as promising models for other countries seeking to create pathways for refugees to demonstrate their skills and access meaningful employment opportunities.

Looking towards the future

Most Ukrainian refugees intend to return to Ukraine. The 3rd round of the Regional Intentions Survey by the UN Refugee Agency found that only a small number of displaced Ukrainians abroad have no intention of returning to Ukraine one day, 65% intend to return when the situation allows, and 12% within the next 3 months (as of June 2023). The factors influencing return to Ukraine include security (n = 94%) and access to basic services (n = 91%), in addition to labour market concerns, lack of child education in Ukraine, and lack of resources to return (UNHCR, 2023[4]).

France, Lithuania and Spain reported that “concerns about the future recognition of diplomas upon return to Ukraine” was a barrier stopping Ukrainian refugees from registering in VET programmes in the OECD (2023) survey. Similarly, looking at the enrolment of Ukrainian school children into national education systems, ‘intention to return to Ukraine’ was the second most reported barrier to enrolment after language, suggesting that many Ukrainian families intend to return to Ukraine in the short-medium term and do not want to register in formal education systems. Co-operation between the Ukrainian authorities and host countries will be needed to ensure a smooth transition for those returning to Ukraine with qualifications and other learning experiences from abroad in the future. In Denmark, the Ministry of Children and Education has already been working with the Ukrainian authorities to ensure that the education Ukrainians receive will be recognised by the Ukrainian education system. Beyond formal qualifications, considering mechanisms to recognise experiences and skills gained in host countries will also be important.

As the duration of stay for Ukrainian refugees in receiving countries extends, questions regarding their inclusion into education systems and labour markets become increasingly relevant. Supporting and recognising Ukrainians’ prior learning is one of many ways to ensure the continuation of their studies in their host society. This will have a range of positive effects for Ukrainians, host societies and Ukraine in the future. Displaying flexibility with RPL procedures for Ukrainian refugees will help and support them in a period of extreme difficulty to continue learning and to expand their future opportunities.

Measures which increase the flexibility of RPL procedures, such as accelerated processing times, accepting applications with missing documents and financial aid, are vital for allowing Ukrainians to continue their education and career paths smoothly.

Assessing refugees’ skills beyond their academic qualifications, such as through demonstration or through computer-based assessments, may help reduce the barriers certain refugees face in accessing the labour market.

Recognition of Prior Learning policies are one of many essential support measures for ensuring the enrolment of Ukrainian refugees in education systems. Alongside RPL, addressing barriers such as language, financial and lack of information are equally crucial for ensuring access to education and continued learning for Ukrainian refugees.

References

[10] Andersson, P. (2021), “Recognition of Prior Learning for Highly Skilled Refugees’ Labour Market Integration”, International Migration, Vol. 59/4, pp. 13-25, https://doi.org/10.1111/IMIG.12781.

[8] Domvo, W. (2022), “The challenges surrounding recognition of prior learning for refugees in European universities”, Australian and New Zealand Journal of European Studies, Vol. 14/1, https://doi.org/10.30722/anzjes.vol14.iss1.15855.

[7] ENIC - NAIC (2023), “Recognition of Ukrainian qualifications in 2022-2023”, https://www.enic-naric.net/page-ukraine-2022 (accessed on 26 June 2023).

[23] European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (2022), “Making VET inclusive for Ukrainian refugee students”, Blog Articles, https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/blog-articles/making-vet-inclusive-ukrainian-refugee-students (accessed on 2 June 2023).

[13] European Commission (2022), Guidelines on fast-track recognition of Ukrainian Academic Qualifications, https://education.ec.europa.eu/document/guidelines-on-fast-track-recognition-of-ukrainian-academic-qualifications.

[12] European Commission (2022), Recommendation (EU) 2022/554 on the recognition of qualifications for people fleeing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, https://www.europeansources.info/record/recommendation-eu-2022-554-on-the-recognition-of-qualifications-for-people-fleeing-russias-invasion-of-ukraine/#:~:text=Summary%3A,the%20war%20to%20regulated%20professions.

[11] European Commission (2022), “Supporting refugee learners from Ukraine in higher education in Europe”, Publications Office of the EU.

[17] German Federal Employment Agency (2023), For people coming from other countries, https://www.arbeitsagentur.de/institutionen (accessed on 15/09/2023).

[6] Global Education Monitoring Report (2018), “What a waste: ensure migrants and refugees’ qualifications and prior learning are recognized”, UNESCO, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366312 (accessed on 2 June 2023).

[22] Klatt, G. and M. Milana (2021), “Governing education policy: the European Union and Australia”, Australian and New Zealand Journal of European Studies, Vol. 12/1, https://doi.org/10.30722/anzjes.vol12.iss1.15076.

[9] Marcu, S. (2018), “Refugee Students in Spain: The Role of Universities as Sustainable Actors in Institutional Integration”, Sustainability, Vol. 10/6, p. 2082, https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062082.

[1] OECD (2023), Ensuring Continued Learning for Ukrainian Refugee Students, https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiOTViNDUzNDEtOTlmOS00ZmMyLTgxNDMtYzg4Mjk0ZGVmZDEwIiwidCI6ImFjNDFjN2Q0LTFmNjEtNDYwZC1iMGY0LWZjOTI1YTJiNDcxYyIsImMiOjh9&pageName=ReportSection30b8f2ad2be1e97906bc (accessed on 29 July).

[2] OECD (2023), “What are the integration challenges of Ukrainian refugee women?”, OECD Policy Responses on the Impacts of the War in Ukraine, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bb17dc64-en.

[21] OECD (2023), What we know about the skills and early labour market outcomes of refugees from Ukraine.

[14] OECD (2022), How vocational education and training (VET) systems can support Ukraine, OECD.

[19] OECD (2018), Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work: The OECD Jobs Strategy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264308817-en.

[20] OECD (2014), “The crisis and its aftermath: A stress test for societies and for social policies”, in Society at a Glance 2014: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/soc_glance-2014-5-en.

[18] OECD (2010), OECD Employment Outlook 2010: Moving beyond the Jobs Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2010-en.

[15] OECD, UNHCR (2018), Engaging with employers in the hiring of refugees, https://www.oecd.org/els/mig/UNHCR-OECD-Engaging-with-employers-in-the-hiring-of-refugees.pdf (accessed on 15/09/2023).

[5] Perelli-Harris, B. et al. (2023), MRS No. 74 - Demographic and household composition of refugee and internally displaced Ukraine populations: Findings from an online survey, http://www.iom.int (accessed on 26 June 2023).

[16] Science for Ukraine (2023), #ScienceForUkraine, https://scienceforukraine.eu/.

[4] UNHCR (2023), Intentions and Perspectives of Refugees from Ukraine, https://data.unhcr.org/en/dataviz/304.

[3] UNHCR (2023), Ukraine Refugee Situation, Operational Data Portal - Situations, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine (accessed on 9 June 2023).

Explore further

OECD (2022), “Supporting the social and emotional well-being of refugee students from Ukraine in host countries”, OECD Policy Responses on the Impacts of the War in Ukraine, https://doi.org/10.1787/af1ff0b0-en

OECD (2022), “The Ukrainian Refugee Crisis: Support for teachers in host countries”, OECD Policy Responses on the Impacts of the War in Ukraine, https://doi.org/10.1787/546ed0a7-en

OECD (2022), “Supporting refugee students from Ukraine in host countries”, OECD Policy Responses on the Impacts of the War in Ukraine, https://doi.org/10.1787/b02bcaa7-en

OECD (2023), “How to strengthen support for Ukrainian refugees in schools and universities”, webinar, 14 June 2023, https://www.facebook.com/OECDEduSkills/videos/582627040722824/