Social policies for an inclusive recovery in Ukraine

Essential actions are needed before the onset of the winter to address the urgent needs of vulnerable individuals and groups and of small businesses affected by Russia’s large scale aggression. They include, but are not limited to, reconstructing critical assets to provide adequate housing and access to quality basic services for all.

Although supporting the path towards an inclusive recovery requires immediate actions, Ukraine needs comprehensive social and employment strategies to address the long-term needs of its most vulnerable citizens.

Significant medium-to-long term employment and social priorities that existed even before the invasion must also be addressed in the context of war and reconstruction. Ukraine was already experiencing challenges with youth who were not in employment, education or training (NEETs), sizable informal and under-declared employment, and internally displaced persons with weak connection to the public employment service.

Ukraine was also in the midst of a rapid demographic transition, with a declining working age population resulting from a low fertility rate and high migration outflows. Demographic prospects will depend to a significant extent on the ability of those who fled the country during the war – especially adults of childbearing age and children – to return.

The war is exacerbating pre‑existing disadvantages of children, women, and elderly people, as well as people with disabilities. Many individuals in these groups were already extremely vulnerable prior to the war.

Ukraine will also face the need to help its citizens address the traumatic experiences they have undergone and anxiety-related symptoms, so as to avoid turning them into serious long-term mental health conditions.

Background and key issues

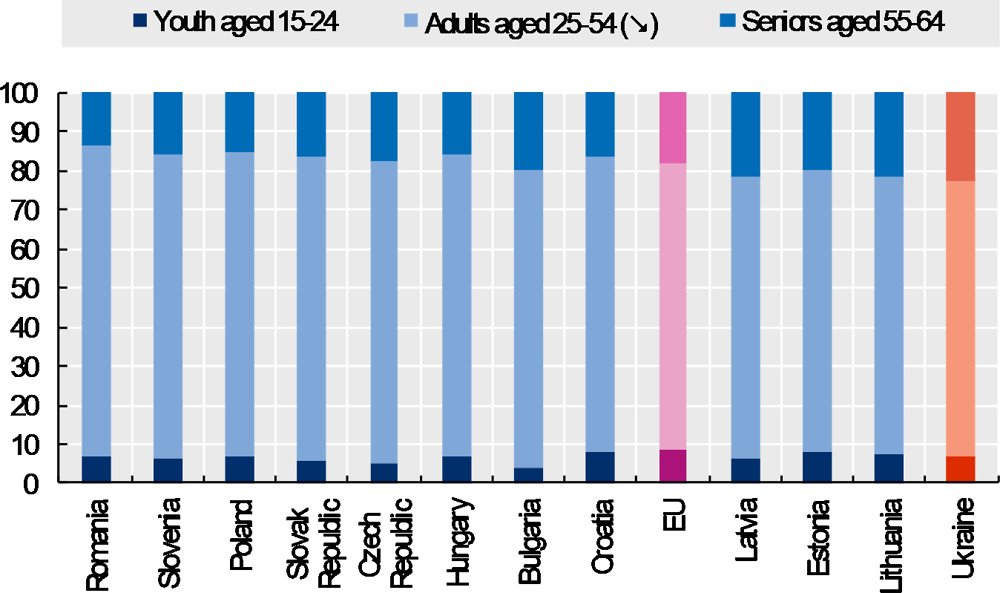

Before Russia’s war against Ukraine, the country was experiencing a rapid demographic transition. Some 25% of the population is aged 60 or above – the pension age in 2021 – resulting in an old-age (60+) to working-age (16‑59) ratio of over 40%, higher than in most OECD countries (Figure 1). This is paired with a low fertility rate and high outmigration for employment abroad. The pensioner dependency ratio was higher, at over 45%, due to early retirement as well as disability and survivor pensions. Around 80% of single elderly Ukrainians, mostly women, live below the official poverty line, with 90% of pensioners unable to pay for even basic medical needs despite having about five chronic diseases on average. Furthermore, the war is worsening the employment situation of women pushing them into the informal sector and exacerbating poverty risks. The International Organization for Migration estimates that 64% percent of the adult internally displaced population are female.

Source: Source: ILOSTAT for Ukraine based on the Labour Force Survey and Eurostat for the EU countries.

In addition, Ukraine should address rising disability prevalence and child poverty. There were 2.7 million people with disabilities in Ukraine, or 6% of the population, prior to the war – most likely a lower estimate that included only people with more severe disabilities and excluded many with mental disabilities. Since Ukraine ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2009), inclusion and accessibility have been on the policy agenda. Child poverty was also a big issue with one‑third of families with children experiencing material deprivation. Ukraine has one of the highest number of children in institutionalised care in Europe. Likewise, institutional care for children with disabilities is more common than in most OECD countries, with only a minority attending mainstream schools.

As such, it will be critical for Ukraine to prevent traumatic experiences from the war and anxiety‑related symptoms from turning into serious long-term mental health conditions. The terrible and traumatic effects of the war that is now under way add to the scars of the long-standing conflict in Eastern Ukraine and the COVID‑19 crisis. In 2016, 32% of internally displaced persons in Ukraine experienced post-traumatic stress disorder and 22% experienced depression according to the results of a nation-wide survey conducted by Roberts and fellow researchers (Roberts et al., 2019). OECD work documented the population-wide increase in the prevalence of mental health issues across all countries during the COVID‑19 crisis, particularly among individuals facing job loss or financial insecurity and young people.

An unemployment rate of around 9% in 2021 masked challenges with youth who were not in employment, education or training (NEETs), sizable informal and under-declared work, and internally displaced persons with little connection to the public employment service (PES). Employment indicators for the young, women and those in rural areas had worsened in recent years. Skills mismatches were pervasive, particularly for young workers. Before the war, the Ukrainian State Employment Service (SES), a large agency with 500 offices and 9 000 staff, was reducing administrative tasks and increasing job-counselling resources to focus on those needing more support or facing multiple barriers.

The small and medium enterprise (SME) sector accounted for 63% of business employment prior to the war and nearly 50% of private‑sector value added. Despite the territorial losses experienced over the past eight years and difficulties in attracting foreign investment inflows, the recent past showed a welcome expansion of ICT and efforts to modernise agriculture, helped by considerable logistics and infrastructure investment. Strengthening the diversification of production will be critical to recovery, which will require well-matched skills development.

Ukraine had started implementing an ambitious e‑government agenda, prior to the war. The reform of the SES included new e‑services to enable jobseekers and employers to create online accounts to facilitate jobseekers’ interactions with both the SES and employers, and web-based platforms for career guidance and development. Regarding social services, the Ministry of Social Policy presented a “Strategy for digital transformation of the social sphere” in 2020. The goal was to create a unified information system of providers and recipients of social services and benefits.

What are the impacts?

The war has already inflicted devastating economic and social losses to Ukraine. An estimated 4.8 million jobs have been lost, some 30% of pre‑war employment. Further military escalation could lead the number of job losses to increase to some 7 million. Of the 5.2 million refugees forcibly displaced by the war and now outside Ukraine, around 1.2 million were estimated to have been working previously. Two-thirds of these have tertiary education and half were employed in high-skilled occupations. Extensive infrastructure damages, disruptions of supply chains, and interruptions to Black Sea shipping have forced Ukrainian businesses to cease activities or relocate away from war zones. Up to half of businesses in Ukraine have ceased operations. In May 2022, the SES and the Ministry of Economy signed an agreement on co‑operation with the five largest employment websites to create a single vacancy database. This initiative aims to support a rapid resumption of employment, as soon as economic activity resumes.

In some regions and towns, the full or partial destruction of schools, hospitals and specialised centres for children, the elderly and people with disabilities, have undermined the capacity to reach out to the most vulnerable groups. The war’s first 100 days led to the displacement of 3 million children internally, and over 2.2 million to refugee‑hosting countries, amounting to almost two‑thirds of the country’s children. Displaced children are extremely vulnerable to being separated from their families, exploited and trafficked. It is important to keep children as close to home as possible. The current ability to educate those remaining is severely affected. The decline in the number of social workers and their reduced mobility is particularly damaging for the elderly who make up two‑thirds of individuals who have remained in the war zone or in occupied territories. People with disabilities face additional challenges. Being less mobile or independent, many have difficulties accessing safe shelters, with access to food, water and sanitation also threatened. Local NGOs have reported that many people with disabilities have been unable to flee, within or outside Ukraine.

Business disruptions and job losses have led to a drastic decrease in social contributions. Only 36% of those in a working age (15 to 64 years) were actually paying contributions in 2021. Yet, the war has further exacerbated the pressure on social funds. Pensions still need to be paid and the number of people needing social support increased drastically. Rising inflation rates will compound poverty risks amongst pensioners.

Preliminary evidence points to dramatic mental health impacts. Reported feelings of depression and nervousness reached two‑thirds of the population in March 2022, up 20 percentage points from January. The WHO has also reported that the most common request to health care professionals is “how to deal with sleeplessness, anxiety, grief and psychological pain”. In such situations, psychological support and psychotherapeutic treatment become lifesaving. Information about massacres of civilians, like Bucha, will lead to population-wide trauma. Community mental health systems are likely to be overwhelmed, even more where those who could provide psychological care are also affected and structures previously in place have disappeared.

What is the outlook?

As progress is made to address immediate challenges, it is essential to support employment to reduce the economic and social costs of the war and enable a faster recovery in the future. The immediate phase must involve the reconstruction of critical assets, services and infrastructure that provide access for all to basic services; support for livelihoods, or social protection to affected populations; and security measures to de‑mine and remove unexploded military explosives. This phase should take place before the onset of winter and will largely rely on receiving adequate international grant financing, including Official Development Assistance from OECD members. Resources permitting, the ongoing relocation programme, which aims to protect existing industrial capacities by moving business to safe regions, should also continue in the initial phase. Going forward, employment incentives that bolster firms’ ability to re‑connect people with jobs should be considered – for example, targeted subsidies that help viable firms re‑absorb labour in the face of short-term financing difficulties. Providing monetary incentives to private firms to create jobs will be a key policy tool and can be financed with reconstruction funds. Targeted state‑subsidised insurance programmes to protect businesses against the risk of war destructions could also mitigate uncertainty and encourage private investment, including from abroad. As conditions improve and allow, private insurers will gradually gain ground. Twinning programs between foreign and local businesses can support employment creation and the transfer of technologies, as well as to facilitate the return of Ukrainians from abroad and leverage their skills. Simplifying and digitising business registration procedures accompanied by entrepreneurial training and easier access to credit could facilitate enterprise creation. The social economy (for example, associations, co‑operatives and social enterprises) could be leveraged to create jobs and promote welfare as they did in many countries during COVID‑19.

Large structural changes to the economy will occur, as the industrial mix and labour skills required adjust to support rebuilding. Rapidly re‑initialising the support of SES job counselling and job matching services, particularly in construction and ancillary industries, will be vital. Adaptable Vocational Education and Training (VET) and broader training programmes will equip individuals with the skills needed to manage the re‑construction. It will be important to integrate employment services effectively with health, housing and other social services to manage the complex array of needs of jobseekers, in particular the most vulnerable ones. In the meantime, programmes to maintain, recognise and upgrade refugees’ skills in the destination countries will be important to ensure people are given the support they need to help Ukraine re‑build on their return. Responses to previous crises have shown that VET systems can be inclusive of refugee learners without sacrificing the quality of provision.

Efforts should be deployed to secure quality services for the groups most exposed to the long‑term consequences of the war. Developing community-based services for children will be an important step to offer alternatives to institutionalised care. Intercountry adoption may be part of the response for orphaned children, but reforms of the adoption system are urgent to bring Ukraine in line with the Hague Convention and to prevent the sale and abduction of children. Disability-inclusive humanitarian measures are necessary to ensure access to basic services, to facilitate evacuations, and to help those injured in the conflict with prosthetics and rehabilitation. In the medium term, increasing participation in society and labour markets of people with disabilities must be a priority to reduce poverty, through mainstreaming measures designed together with the involvement of the disability community and responding to people’s diverse needs. In addition, gender mainstreaming in all areas of national policy is a requirement. Making sure that women’s talents, professional and entrepreneurial skills are fully used in the recovery will ensure an inclusive and more robust economic, social and political development. Ukraine joined the Equal Pay International Coalition (EPIC) in December 2020, whose principles will provide relevant guidance in supporting the social recovery.

When the economy recovers, contributions to a compulsory earnings-related pension scheme would improve pension prospects. As age 60 is low for retirement in international comparison, retirement ages will need to be gradually increased to enable higher pensions, with increases being linked to changes in life expectancy. In the near term, it is vital to guarantee that the minimum pension be paid and received. The minimum pension, around 22% of average earnings in 2020, will need to be increased given inflationary pressures and be at least equivalent to the minimum subsistence level (28% of average earnings). Community and care facilities for the elderly, including geriatric services, will need to be rebuilt and upgraded. In addition, domestic care services for the elderly will have to be expanded. Increased medical checks and greater uptake of preventive medicines will help to reduce long-term medical costs. Financial support through food vouchers and first-necessity baskets could be provided for those below the poverty line. Third-age universities can act as focal points providing, among others, courses on mental well-being.

Ukraine can draw from experiences across the OECD to address the psychological impact of war and prevent long-term consequences on population mental health. First, it is important that people receive mental health care since large unmet needs could have high long-term costs for society. This requires an immediate response capable of considering the pervasive nature of traumas and promote community resilience (e.g. through neighbourhood discussions groups and peer support) and better access to emergency support. Second, it is important to recognise the wide range of stakeholders from different sectors that must be involved in identifying and responding to mental health needs. This can include youth workers, teachers, community leaders, social workers, employment counsellors, general practitioners, and pharmacists. Third, interventions must address social, health, employment and other needs at the same time as providing access to mental health services.

Ukraine can learn from international best practices in the digitalisation of employment and social services, building on pre‑war progress. Investments in digital employment services will offer efficiencies in terms of scale and speed, as services are not geographically limited and can reach more people quickly, including those abroad. In addition, while there will be resource constraints after the war, the creation of online self-service channels will help to mitigate this challenge. Further investing in tools to facilitate the rapid matching of jobseekers with sectors requiring workers, including to assist reconstruction efforts, will also prove vital in the recovery phase. Furthermore, it will be important for the SES to engage with its partners in social and health services to ensure that holistic and integrated supports are provided to those in need.

The reconstruction of critical assets will be vital for Ukraine in the short-term, e.g. adequate housing and access to quality basic services; support for livelihoods and social protection for those directly affected by the war; and implementation of security measures, including de‑mining and removing unexploded military explosives. Supporting existing employment will reduce the immediate economic and social costs of the war and enable faster employment recovery in the future. Depending on the war, this phase should take place before the onset of winter – and will largely rely on receiving adequate international grant financing, including Official Development Assistance from OECD members.

Going forward, providing monetary incentives to private firms to create jobs will be a key policy tool and can be financed with reconstruction funds. Job counselling and matching will have to be rapidly re‑initialised and adaptable training programmes implemented to support re‑building in the face of changes to required labour skills and towards an increasingly diversified industrial mix. Integrating employment services with health, housing and other social services will help managing the complex needs of the most vulnerable. To this end, Ukraine can learn from international best practices in the digitalisation of employment and social services. Maintaining, recognising and upgrading refugees’ skills in destination countries will ensure people are given the support they need to help Ukraine re‑build on their return.

Efforts will be needed to protect the groups most exposed to the long-term consequences of the war – children, the elderly, women and people with disabilities. Adding to pre‑existing challenges, the infrastructure supporting these groups has been severely damaged or completely destroyed in some regions and towns and will need to be rebuilt. When peace returns and the economy recovers, making contributions to a compulsory earnings-related pension scheme would improve pension prospects. Retirement ages will need to be gradually increased to enable higher pensions, with increases being linked to changes in life expectancy.

Ukraine will have to address the psychological impact of the war. In addition to immediate, adapted responses capable of considering the pervasive nature of traumas, it is important to recognise the wide range of stakeholders from different sectors that must be involved in preventing and responding to mental health needs. This can include youth workers, teachers, community leaders, social workers, employment counsellors, general practitioners, and pharmacists. Interventions must also address social, health, employment and other needs at the same time as providing access to mental health services.

Further reading

Becker, T. et al. (2022), A Blueprint for the Reconstruction of Ukraine, https://cepr.org/sites/default/files/news/BlueprintReconstructionUkraine.pdf.

Borodchuk, N. and L. Cherenk (2021), Child poverty and disparities in Ukraine, UNICEF in Ukraine and Ptoukha Institute for Demography and Social Studies of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv.

Cabinet of Ministers (2020), Supporting Small and Medium Businesses, www.kmu.gov.ua/en/reformi/ekonomichne-zrostannya/supporting-small-and-medium-businesses.

Global Protection Cluster (2022), Protection of persons with disabilities in Ukraine.

Hunjadi, M. (2021), Ukraine: Digitalization of the social sphere, Eastern European Social Policy Network, http://Eastern European Social Policy Network.

ILO (2022), Inclusive labour markets for job creation in Ukraine, www.ilo.org/budapest/what-we-do/projects/WCMS_617840/lang-en/index.htm.

ILO (2022), The impact of the Ukraine crisis on the world of work: Initial assessments, www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_844625/lang-en/index.htm.

ILO (2022), Turning around a super tanker−reforming the public employment services in Ukraine, www.ilo.org/budapest/whats-new/WCMS_836255/lang-en/index.htm.

KSE Institute (2022), Damages to Ukraine’s infrastructure, 8 June, https://kse.ua/russia-will-pay/.

Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (2022), Overview of the current state of education and science in Ukraine in terms of russian aggression (as of 06-11 June 2022), Ministry of Education and Science, Kyiv.

OECD (forthcoming), How VET systems can support Ukraine: Drawing lessons from VET systems’ responses to past crises, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2022), Rights and Support for Ukrainian Refugees in Receiving Countries, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/09beb886-en.

OECD (2022), The COVID‑19 Crisis in Ukraine, www.oecd.org/eurasia/competitiveness-programme/eastern-partners/COVID-19-CRISIS-IN-UKRAINE.pdf.

OECD (2022), “Harnessing digitalisation in Public Employment Services to connect people with jobs”, Policy Brief on Activation Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.oecd.org/els/emp/Harnessing_digitalisation_in_Public_Employment_Services_to_connect_people_with_jobs.pdf.

OECD (2021), Pensions at a Glance 2021: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ca401ebd-en.

OECD (2021), “Active labour market policies and COVID‑19: (Re‑)connecting people with jobs”, in OECD Employment Outlook 2021: Navigating the COVID‑19 Crisis and Recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0b6ad4a0-en.

OECD (2021), A New Benchmark for Mental Health Systems: Tackling the Social and Economic Costs of Mental Ill-Health, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4ed890f6‑en.

OECD (2021), Fitter Minds, Fitter Jobs: From Awareness to Change in Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policies, Mental Health and Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a0815d0f-en.

OECD et al. (2020), SME Policy Index: Eastern Partner Countries 2020: Assessing the Implementation of the Small Business Act for Europe, SME Policy Index, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Union, Brussels, https://doi.org/10.1787/8b45614b-en.

OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Results (Volume II): Where All Students Can Succeed, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b5fd1b8f-en.

OECD (forthcoming), Disability, Work and Inclusion: Rigorous Mainstreaming throughout all Policies and Practices, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Opening Doors for Europe’s Children (2019), 2018 Country Fact Sheet Ukraine, www.coe.int/t/commissioner/source/NAP/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

Roberts, B. et al. (2019), “Mental health care utilisation among internally displaced persons in Ukraine: results from a nation-wide survey”, Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, Vol. 28/1, pp. 100‑111, https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796017000385.

Smusz-Kulesa, M. (2020), Needs assessment report with respect to policy and legal framework revision in the area of rights of people with disabilities in Ukraine, https://rm.coe.int/final-report-eng‑1‑/16809f31b5 (accessed on 16 June 2022).

UNDP (2022), The Development Impact of the War in Ukraine: Initial Projections, www.undp.org/publications/development-impact-war-ukraine-initial-projections.

UNDP (2022), Ukraine launches new e‑service for internally displaced persons, www.undp.org/ukraine/press-releases/ukraine-launches-new-e-service-internally-displaced-persons

UNICEF (2022), “One hundred days of war in Ukraine have left 5.2 million children in need of humanitarian assistance”, UNICEF Press Release, www.unicef.org/press-releases/one‑hundred-days-war-ukraine-have-left-52-million-children-need-humanitarian.

WHO (2022), One hundred days of war has put Ukraine’s health system under severe pressure, www.who.int/news/item/03-06-2022-one‑hundred-days-of-war-has-put-ukraicne-s-health-system-under-severe-pressure.

Related content

OECD Pension Policy Notes and Reviews www.oecd.org/pensions/policy-notes-and-reviews.htm

OECD Jobs Strategy www.oecd.org/employment/jobs-strategy

OECD Gender Initiative www.oecd.org/gender

OECD activities on children www.oecd.org/els/family/child-well-being/

OECD activities on youth www.oecd.org/employment/youth/

OECD activities on mental health www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/mental-health.htm

OECD activities on skills and work www.oecd.org/employment/skills-and-work

OECD activities on social policies and data www.oecd.org/els/soc