Supporting refugee students from Ukraine in host countries

Given the unprecedented number and unique profile (50% of refugees are children) of Ukrainians fleeing their country in a short time following its invasion by Russia, host country schools are facing challenges to increase capacity and address the needs of the new refugee students.

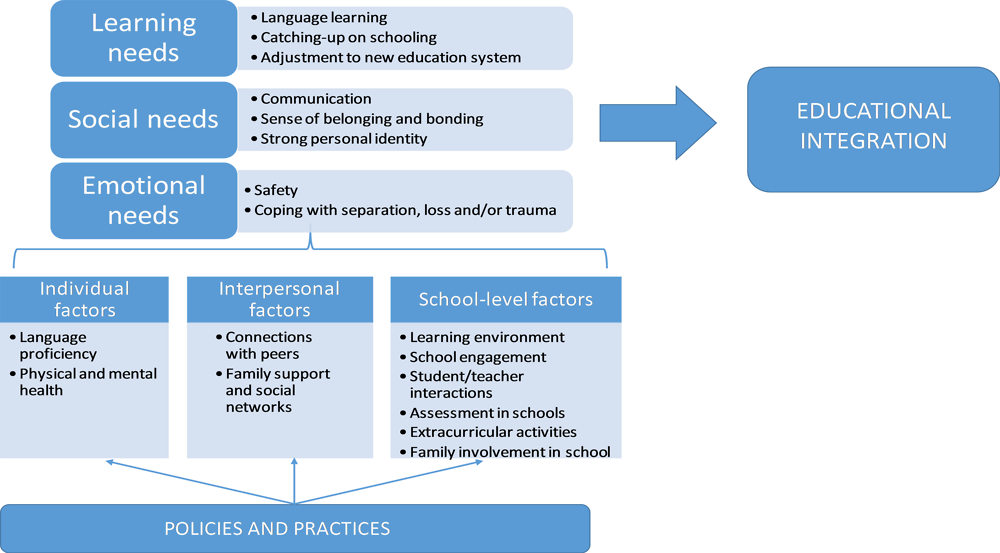

A holistic approach is needed to address the learning, social and emotional needs of Ukrainian students.

As refugee students may be in their host countries for moderate to long periods, education systems will need to develop capacity quickly in order to be able to integrate potentially large numbers of Ukrainian refugee students in schools. Coordinated exchanges with Ukrainian policy makers and the provision of opportunities for students to stay connected with Ukrainian curriculum, language and culture are also important as many refugees may wish to return to Ukraine in the future.

Background and key issues

Russia’s large-scale aggression against Ukraine has led to an estimated 5.3 million individual refugees from Ukraine recorded to date1 across Europe (UNHCR, 2022[1]). This is already becoming the fastest growing refugee crisis in Europe since World War II. Estimates indicate about half of those fleeing are children and youth. Many of those are unaccompanied or separated from their families. Refugees are mostly fleeing to neighbouring and other European countries such as Poland, the Slovak Republic, Moldova, Romania and Hungary, but also other European countries including Austria, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Germany, France, Italy, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom (UNHCR, 2022[1]). In response to the influx of refugee students from Ukraine in host countries, many education systems have started to implement a variety of inclusion policies and practices to support the learning, social and emotional needs of these students.

For children, returning to school can provide a sense of security and stability. It is also critically important for them to ensure that they have the career opportunities of their choice as they enter adulthood. Initially, though, it can also be bewildering as they navigate new spaces and languages while also processing loss. Teachers can be role models of compassion and kindness to encourage host country students to help them feel welcome. They could also learn the proper pronunciation of the students’ names and a simple “Hello; how are you?” in Ukrainian to help the students feel included. Schools can also pair them with local “buddies”, school students who can help them and introduce the new students to others. Informal educational experiences, such as opportunities to engage in arts and sports, can provide outlets for stress as well as providing students with opportunities to demonstrate skills and talent. Informal events also offer opportunities to practise new language skills in a lower pressure environment.

Moving beyond providing immediate support to refugees, policy makers have to deal with the challenges of promoting the integration of those who are likely to stay, including refugee children and youth. The first challenge for host countries is to ensure access to education for all refugee students. The second challenge is to develop educational policies and practices that respond to the needs of refugee students and promote their inclusion in schools and societies in the medium- to long-term (de Wal Pastoor, 2016[2]). Some of the countries bordering Ukraine are receiving the highest numbers of refugees (UNHCR, 2022[1]). These countries have less experience with integrating refugees than other OECD countries such as Canada, Germany, France, Italy and Turkey. They can look to these countries, as well as to international organisations, for strategies and practices to support the Ukrainian students.

What are the impacts for education systems?

Refugee students are not a homogenous group, so developing individual education plans and flexible curricula in schools is important to enable teachers, school leaders and non-teaching staff to support them as individuals. Early initial assessment of language and other skills can also help for proposing the best educational trajectory. Countries such as Finland and Sweden tailor individualised learning plans to refugee students, based on their needs, previous education and current social/family situation. In Sweden, within two months of starting school, all new arrivals are assessed on their academic knowledge and language skills. Additionally, the assessments are offered in the students’ mother tongues in order to best assess previous knowledge without language barriers. The principal and/or head teacher determine the best educational trajectory. The decision is based on the student’s age and language skills, and results of the mapping of previous knowledge (Cerna, 2019[3]). In Finland, the model of integrating newly arrived students into mainstream education provides that, within the first year, an individual curriculum be designed for each student tailored to his/her needs and based on their previous school history, age and other factors affecting their school work [e.g. being an unaccompanied minor who is coming from a war zone]. The individual curriculum is created through collaboration with the teacher, the student and the family (Cerna, 2019[3]).

Providing support for learning the host country language is key to ensuring that students do not fall behind in learning subject content. In addition, research shows that retaining and developing their mother tongue is important for refugee students’ sense of belonging (Cerna, 2019[3]). In Romania, refugee students are able to enrol in one of the 55 schools offering instruction in Ukrainian. Teachers in standard Romanian schools are also being encouraged to provide instruction in Ukrainian when they are able to do so (UNESCO, 2022[4])). Refugee students can also access instruction in Belarusian in selected public schools in Lithuania, and some public schools in Estonia also provide instruction in Russian (UNESCO, 2022[4]). In Portugal, Ukrainian textbooks are made available to refugee students, and bilingual Ukrainian-Portuguese children’s books and textbooks have been produced to provide continuity of learning while developing familiarity with the Portuguese language (Mizzy, 2022[5]).The Portuguese Ministry of Education, together with Rádio e Televisão de Portugal, has also developed a televised distance learning programme that features 14 classes, each co-led by a Ukrainian teacher and a Portuguese teacher. In addition to Portuguese language instruction, the programme also teaches viewers about aspects of both Portuguese and Ukrainian cultures (N-TV Tem Vida, 2022[6]). Several European countries, such as Lithuania, Portugal and Spain, are offering “bridging” or transition classes where refugee students can learn the host country language and familiarise themselves with the local education system, as well as receiving psychological support (UNESCO, 2022[4]). In the United Kingdom and France, targeted language support is provided in some of the full immersion programmes established to introduce refugee students to the basics of the host country curriculum. This can take the form of short daily classes with a host country language teacher or support from a teaching assistant who speaks the student’s mother tongue or otherwise has experience teaching non-native speakers in standard classes (School Education Gateway, 2022[7]).

Education systems in host countries need to consider holistic approaches to supporting refugee students, as they are likely to need not only academic services but also social and emotional support and health services (see Figure 1). For example, Mobile Intercultural Teams (Mobile Interkulturelle Teams, MIT), a programme of the Ministry of Education in Austria, offer support to teachers and administration who work with immigrant and refugee children. In addition, there is often a psychologist qualified to help children who have experienced trauma or difficulty in their lives. This support varies and can include advice for teachers, individual casework with students, and workshops to improve classroom climate. The MITs interact with parents of immigrant and refugee students to integrate them into the school community and often serve as a language bridge between students, parents and the school (Cerna, 2019[3]). In the Netherlands, the non-governmental Pharos programme provides support to the social-emotional development of refugee children in secondary schools. The goal is to give attention to the difficulties refugee children face, strengthen peer support systems for refugee children by offering opportunities to share their histories and experiences with other children, foster teacher support for refugee children and strengthen coping ability and resilience among refugee children (Cerna, 2019[3]).

Source: Cerna, L. (2019[3]), “Refugee education: Integration models and practices in OECD countries”, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/a3251a00-en.

What is the outlook for refugee students from Ukraine?

European Union law requires that newcomer students be registered in host country schools within three months of moving. To date, there has been flexibility regarding enrolment in host country schools; however, by the fall 2022, all Ukrainian students still outside their home country will have to attend schools in the countries where they currently reside. Refugee situations are unpredictable, and many refugees may be in a host country for a moderate to long-term period. It is therefore crucial for education systems in host countries to develop capacity quickly to enrol a large number of Ukrainian students and plan for financial and human resources in order to integrate potentially large numbers of Ukrainian refugee students in schools from September 2022. In preparation, countries could offer summer camps for Ukrainian refugees to develop knowledge of the host country language, interact with local students in an informal setting and catch up/develop subject knowledge. For example, Estonia is organising summer camps for Estonian and Ukrainian children from 7 to 14 years old to interact with peers, learn the Estonian language, exchange about their culture and promote their well-being (Baltic Times, 2022[8]). The Association of Ukrainian Cities and the European Committee of the Regions have also launched a European-wide initiative to organise summer camps for Ukrainian children in European cities and villages. The summer camps will provide refugee children and youth (from six to 17 years of age) and accompanying caregivers with a space where they can spend time with their peers and feel safe, and will offer activities to improve mental and physical health, host country language classes, and psychological support (European Committee of the Regions, 2022[9]).

Since many refugees might return to Ukraine in the future, host countries will need to develop compatible systems and flexible pathways in education. This will require continued co-ordinated exchanges with Ukrainian policy makers and innovative approaches to make the education systems of the host country and Ukraine compatible. This will require providing opportunities to learn Ukrainian language, history and culture, but also other subjects in the Ukrainian curriculum through afternoon or Saturday classes or online learning without overwhelming individual students. Estonia, Finland, Poland and Romania have all made educational material in Ukrainian available online. For example, the New Ukrainian School Hub developed by Finland, Ukraine and the European Union EdTech sector brings together curriculum-based support resources, educational resources and Ukrainian e-learning tools and platforms, which are all available in English and Ukrainian (SchoolEducationGateway, 2022[12]). Flexible recognition of student qualifications at all levels of education will also be necessary. Education ministries should work with accrediting agencies to establish fair and consistent processes for evaluating the credentials of refugees and determining further training needs. For example, the European Qualification Passport for Refugees combines an assessment of documentation and a structured interview. The Guidelines on Fast-Track Recognition of Ukrainian Academic Qualifications published by the European Commission to provide concrete support to higher education institutions in evaluating Ukrainian qualifications (Lanterno et al., 2022[13]). In Portugal, Ukrainian refugees can apply for registration and enrolment in a higher education institution for a course that is similar to the one they were studying in Ukraine. Where the applicant does not have documentary evidence of their qualifications, the higher education institution may use the European Qualifications Passport for Refugees process (UNESCO, 2022[14]).

Social and emotional needs of refugee students might be long lasting. Host countries will therefore also need to provide more counselling opportunities in schools or online (in Ukrainian or with an interpreter). The social and emotional support needed may differ among different profiles of Ukrainian refugee students and the experiences they have since Russia’s invasion. This can impact on the type of counselling required and the support needed to facilitate social interactions with students from host countries and with other Ukrainian students. Additional resources have been invested into multi-agency support centres at the municipal level in order to address high demand for counsellors and psychologists (European Commission: European Education Area, 2022[15]). In Portugal, support is provided in schools and the reception centres for new arrivals by multi-disciplinary teams made up of specialised teachers, psychologists, social workers, and interpreters (UNESCO, 2022[16]). Counselling and/or other forms of psychological support are also provided as part of the “bridging”, “reception” or “adaptation” classes being offered in several European countries, such as Belgium, Denmark, France, Lithuania, Slovakia and Spain (UNESCO, 2022[4]). In addition, host countries and schools should offer extracurricular activities and greater opportunities for refugee students to engage in social interactions both within the Ukrainian community and with the host community. These support measures will be important for developing a sense of belonging to the community, and work in parallel with the academic measures being offered by host countries. Various municipal and non-governmental organisations in the German city of Leipzig are also offering a range of free sports and leisure activities for Ukrainian refugee children and youth (Leipzig Helps Ukraine, n.d.[17]), as is the city of Tallinn in Estonia (Tallin, n.d.[18]). The Council of Europe has developed a series of guides to support those providing language support to Ukrainian refugee children, one of which is focused on developing activities (Council of Europe, 2022[19]).

Refugee students are particularly vulnerable and have different learning, social and emotional needs. Education systems in host countries should adopt a holistic approach in meeting the full range of needs of refugee students from Ukraine.

Due to considerable uncertainty regarding the length of stay of refugee students from Ukraine in host countries, education systems will need to be flexible in meeting the needs of refugee students and providing opportunities to develop skills needed to prepare them for career paths after their return to Ukraine.

Preparing for the new school year in August/ September 2022 will be crucial for education systems in host countries, since relatively high numbers of Ukrainian refugee students may need to be integrated. Host countries will need to plan ahead in order to accommodate all refugee students in schools. This may create considerable challenges on systems in terms of the capacity, human and financial resources needed.

Refugee situations do not disappear quickly, so host countries also need to prepare populations of host countries for long-term support by educating them and reinforcing schools and social services. In addition, refugees from longer standing wars and crises, such as those from Syria, Afghanistan, Venezuela and several African countries, remain in countries now supporting recent Ukrainian refugees. They, too, need continued support.

References

[8] Baltic Times (2022), State supports organization of integration camps for young people from Estonia, Ukraine, https://www.baltictimes.com/state_supports_organization_of_integration_camps_for_young_people_from_estonia__ukraine/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

[3] Cerna, L. (2019), “Refugee education: Integration models and practices in OECD countries”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 203, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/a3251a00-en.

[17] Council of Europe (2022), Language Support for Children arriving from Ukraine: Planning language support activities in the community, https://rm.coe.int/i-planning-language-support-activities-in-the-community/1680a6b0ef (accessed on 21 June 2022).

[2] de Wal Pastoor, L. (2016), “Rethinking Refugee Education: Principles, Policies and Practice from a European Perspective”, in Annual Review of Comparative and International Education 2016, International Perspectives on Education and Society, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, https://doi.org/10.1108/s1479-367920160000030009.

[13] European Commission: European Education Area (2022), Teachers for refugee students - EU Education Solidarity Group for Ukraine reports first outputs on measures for schools, https://education.ec.europa.eu/it/node/2047 (accessed on 21 June 2022).

[9] European Committee of the Regions (2022), Ukraine and EU local leaders join forces to offer summer camps for thousands of children, https://cor.europa.eu/en/news/Pages/ukraine-summer-camps.aspx (accessed on 21 June 2022).

[11] Lanterno, L. et al. (2022), Guidelines on Fast-Track Recognition of Ukrainian Academic Qualifications, European Commission, Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, ENIC Ukraine, CIMEA, http://https://education.ec.europa.eu/document/guidelines-on-fast-track-recognition-of-ukrainian-academic-qualifications.

[15] Leipzig Helps Ukraine (n.d.), Kids & Family, https://leipzig-helps-ukraine.de/category/kids-family/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

[5] Mizzy, S. (2022), Ukrainian children in Portugal receive children’s and school books, https://europe-cities.com/2022/04/01/ukrainian-children-in-portugal-receive-childrens-and-school-books/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

[6] N-TV Tem Vida (2022), RTP launches “Home Study” for Ukrainian citizens, https://www.n-tv.pt/acontece/rtp-lanca-estudo-em-casa-para-cidadaos-ucranianos/796239/.

[19] OECD (2018), Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work: The OECD Jobs Strategy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264308817-en.

[20] OECD (2014), “The crisis and its aftermath: A stress test for societies and for social policies”, in Society at a Glance 2014: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/soc_glance-2014-5-en.

[18] OECD (2010), OECD Employment Outlook 2010: Moving beyond the Jobs Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2010-en.

[7] School Education Gateway (2022), Including Ukrainian refugees in secondary school classrooms: what if the pupils just don’t speak the language?, https://www.schooleducationgateway.eu/en/pub/viewpoints/experts/including-ukrainian-refugees.htm (accessed on 21 June 2022).

[10] SchoolEducationGateway (2022), Online educational resources in Ukrainian: schooling in Ukraine under adverse conditions, https://www.schooleducationgateway.eu/en/pub/latest/news/online-ed-resources-ua.htm.

[16] Tallin (n.d.), Cultural and leisure activities in Tallinn, https://www.tallinn.ee/eng/ukraine/Cultural-and-leisure-activities-in-Tallinn (accessed on 21 June 2022).

[4] UNESCO (2022), Mapping host countries’ education responses to the influx of Ukrainian students, https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/mapping-host-countries-education-responses-influx-ukrainian-students (accessed on 21 June 2022).

[12] UNESCO (2022), Portugak’s education responses to the influx of Ukrainian students, https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/portugals-education-responses-influx-ukrainian-students (accessed on 21 June 2022).

[14] UNESCO (2022), Portugal’s education responses to the influx of Ukrainian students, https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/portugals-education-responses-influx-ukrainian-students (accessed on 21 June 2022).

[1] UNHCR (2022), Ukraine refugee situation, https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine (accessed on 21 June 2022).

Related content

Podcast (2022), “For Ukrainian refugees, school is urgent”, OECD, https://doi.org/10.1787/c676fbc9-en

Koehler, C., N. Palaiologou and O. Brussino (2022), “Holistic refugee and newcomer education in Europe: Mapping, upscaling and institutionalising promising practices from Germany, Greece and the Netherlands”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 264, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9ea58c54-en.

McBrien, J. (2022), “Social and emotional learning (SEL) of newcomer and refugee students: Beliefs, practices and implications for policies across OECD countries”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 266, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/a4a0f635-en.https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/a4a0f635-en.

Contact

Lucie CERNA (✉ lucie.cerna@oecd.org)

Jody MCBRIEN (✉ jlmcbrie@usf.edu)

Note

Countries vary in their approach to labelling Ukrainians who have fled their country due to the current war. For example, policy makers from Ukraine prefer to use “temporarily displaced people”, as they hope and expect that Ukrainians will return to their homeland once peace is established.