Abstract

The COVID‑19 crisis has resulted in a significant increase in online learning by adults. Much of the training that had started as face-to-face in classroom environments has been pursued online. Furthermore, individuals are being encouraged to use the time freed up by short-time work schemes to take up new training. As such, the crisis provides a powerful test of the potential of learning online. It also highlights its key limitations, including the prerequisite of adequate digital skills, computer equipment and internet access to undertake training online, the difficulty of delivering traditional work-based learning online, and the struggle of teachers used to classroom instruction. This brief discusses the potential of online learning to increase adult learning opportunities and identifies some key issues that the crisis has highlighted. Addressing these issues could contribute to expanding online learning provision in the post-crisis period and to making it more inclusive.

Introduction and key messages

The ongoing COVID‑19 crisis has seen a substantial increase in online learning by adults (Box 1). Much of the training that was originally planned for the classroom is now being delivered online. Furthermore, individuals are being encouraged to use the time freed up by short-time work schemes to train online from home and acquire new skills deemed useful in the aftermath of the health emergency. Although it is too soon for a full assessment, early data and anecdotal evidence suggest a sizeable increase in online learning. In the Flemish Region of Belgium, the number of participants in online training provided by the Public Employment Service (VDAB) in the second half of March 2020 was four times as high as in the same period last year.1 Evidence from web searches also points to a surge in interest in training online. In Canada, France, Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States, searches for terms such as online learning, e-learning and Massive Online Open Courses (MOOCs) increased up to fourfold between end-March and early April 2020 as strict lockdown rules came into force in most OECD countries. They were still about twice as high as their long-term trend at the end of April 2020.

As such, the crisis provides a powerful test of the potential of online learning. It has also revealed its key limitations, including the prerequisite of adequate digital skills, computer equipment and internet connection to undertake training online, the difficulty of delivering traditional work-based learning online, and the struggle of teachers used to classroom instruction.

This brief discusses the potential of online learning to expand the opportunities for adult learning, and identifies some key issues that the crisis has highlighted. Addressing these issues could contribute to the expansion of online learning in the post-crisis period and to making online learning more inclusive.

Expanding adult training provision through online learning would have significant advantages. In particular, online learning could help reach a much bigger number of learners with a smaller investment in education infrastructure, making it a cost-effective solution in the context of rising unemployment due to the COVID‑19 crisis. However, for online learning to represent a valuable alternative to face-to-face instruction, it would needs to provide high-quality reskilling and upskilling opportunities that can translate into sustainable employment opportunities for job seekers and productivity gains for firms and the economy more broadly. Issues of inclusiveness would also need to be tackled to ensure that all adults can benefit from online learning, including adults with lower digital skills and limited access to computer and internet facilities, adults with less self-motivation and those requiring blue-collar training. Lessons learnt during the COVID‑19 crisis can help address the existing limitations to realise the full potential of online learning.

Developing basic digital skills will be instrumental to the mainstreaming of online learning. Users of online learning are primarily highly educated adults with strong digital skills. Before the COVID‑19 crisis, 23% of training participants with high digital problem solving skills participated in online learning every year, compared with just 14% of trainees with no computer skills. Several countries launched programmes to equip adults with basic digital skills prior to the crisis.

Motivating online learners is key to retention. Evidence from Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) shows completion rates as low as 10%. In addition to basic digital skills, online learning requires autonomy and self-motivation. In the context of the crisis, many apprenticeships and TVET providers have put emphasis on building and maintaining the motivation of online learners.

Broadening the range of online courses is crucial to make online learning more inclusive. Few courses are currently available online and they tend to focus on the skills needed in white-collar jobs. In France, it is estimated that, prior to the crisis, only about 10% of training courses were accessible online. While the crisis will have increased that share, training for crafts-related occupations and training involving a work-based component remains difficult to deliver online.

Strengthening the digital infrastructure is a fundamental context factor for online learning to be a viable option in the delivery of online learning to a broader group of adults. Unequal access to the Internet risks exacerbating existing inequalities in education and training. During the COVID‑19 crisis, several countries provided laptops with internet connections to disadvantaged students. Some are now considering funding internet access as a basic service that all citizens should have access to, including those living in rural regions or from poorer economic backgrounds.

Training teachers to deliver online courses effectively is important to raise the quality of online courses. Some countries are developing curricula to equip teachers and managers at training institutions with the skills needed to shift the training offer to online delivery.

Developing effective testing methods and certificates is important to ensure that online training, both formal and non-formal, is valued in the labour market. Tests, quizzes and assessments are becoming an important part of online training courses. They help consolidate learning and measure the effectiveness of the learning course. In the area of certification, an innovative solution is the adoption of digital badges: portable visual tokens containing information about the individual, the skills he/she has acquired and the badge issuer. There is a risk that the proliferation of certificates and credentials from online learning may dilute its value in the labour market and in granting access to further training. Some regulation and standardisation are needed to guarantee that skills learnt online are recognised and valued by companies and education institutions.

Establishing quality assurance mechanisms for online learning is essential to ensure that online courses provide value for money/time to participants. The COVID‑19 crisis will provide a valuable natural experiment on the employment and wage returns of online learning compared to face-to-face instruction. Results from this assessment would help identify the features of online learning provision that are most likely to lead to positive outcomes for participants, all else being equal. They would also shed light on whether these features differ from those identified for face-to-face instruction, justifying or not the need for an ad-hoc quality assurance system.

How online delivery can help broaden the reach of adult learning

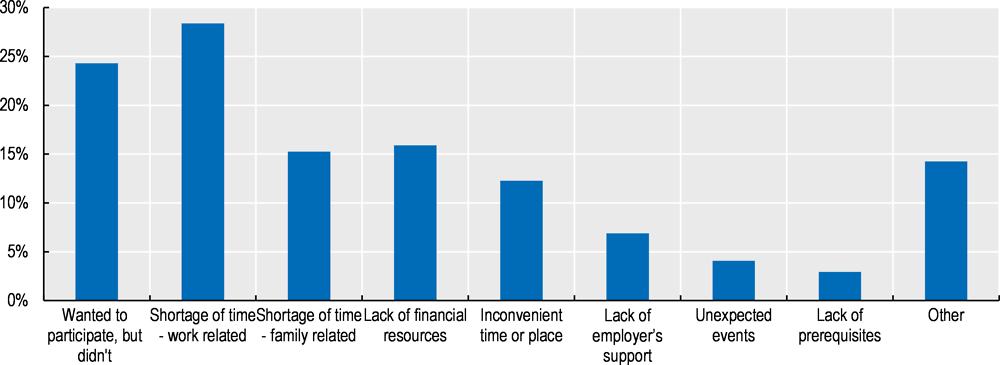

Participation in learning throughout each person’s working life is crucial to navigate changing labour markets in an increasingly digitalised economy. It helps maintain existing work-related skills and acquire new in-demand ones (OECD, 2019[1]). In particular, training will be important for the increased number of unemployed to gain skills that are likely to be in high demand in the post-COVID‑19 world. Yet, today, only about 40% of adults, on average in OECD countries, participate in formal and non-formal job-related2 training annually and they are disproportionately high-skilled. Among the low-skilled, the incidence of adult learning is just over 20% on average (OECD, 2019[2]). Lack of time, scheduling conflicts and distance constraints are among the key barriers reported by those who do not undertake any training, along with a lack of financial resources (Figure 1). About 28% of adults claim they do not participate in training because they lacked time due to work commitments and another 15% report a lack of time due to family responsibilities. An additional 16% mention a lack of financial resources and 12% state that training took place at an inconvenient time and place.

Note: Average of OECD countries participating in PIAAC. Figures refer to participation in formal and non-formal adult learning.

Source: OECD Secretariat calculations based on the Survey of Adult Skills, PIAAC (2012, 2015, 2017). The bar “Wanted to participate but didn’t” refers to the share of adults who responded that they did not take part in training over the previous 12 months but would have liked to”.

Online learning has the potential to address these barriers to training. It allows learners to choose a time, rhythm and place compatible with work and family responsibilities. The flexibility of online learning courses is particularly important for training that is meant to facilitate job transitions. Training to perform better in one’s current job is more often financed by employers and can more easily be carried out during working hours. In addition to providing more flexibility, online learning tends to be cheaper than equivalent face-to-face provision which would help overcome financial constraints. As shown in the context of the ongoing COVID‑19 crisis, online learning also has the potential to provide continuity when face-to-face training provision is not available. Although evidence on its effectiveness compared to face-to-face training is lacking at this stage, the COVID‑19 crisis will provide a valuable natural experiment to measure employment and wage returns.

#OnlineLearning has the potential to address time, scheduling and location barriers to #AdultLearning

Terms such as e-learning, online learning and distance learning are often used interchangeably in the media and policy discourse. However, there are important differences between them.

Online learning (often referred to as e-learning) refers to the use of digital materials to support learning. It does not necessarily take place at a distance. It can be used in physical classrooms to complement more traditional teaching methods, in which case it is called blended learning.

Distance learning refers to learning that is done away from a classroom or the workplace. Traditionally, this involved offline correspondence courses wherein the student corresponded with the school via post. Today, it involves mainly online education, with an instructor that gives lessons and assigns work digitally. Most statistical sources available (including those used in this brief) collect information on distance learning – as opposed to online learning – and potentially include individuals following a training course by correspondence, although this type of distance learning is rapidly being replace by digital methods.

In this brief, the term online learning is used mostly to refer to learning through digital resources that is carried out at a distance. This is particularly the case when discussing measures taken in the context of the COVID‑19 crisis during which most face-to-face training was interrupted to enforce physical distancing. However, some of the lessons put forward for further development of online learning also apply to blended online learning.

It is also important to acknowledge that, like face-to-face instruction, online and distance learning cover a very broad range of courses, ranging from university courses delivered online and shorter non-formal training focused on specific skills, to Massive Open Online Courses – to give only a few examples. The recommendations put forward in this brief apply to a varying extent to the different types of online learning courses. For instance, pre-requisites in terms of digital skills and infrastructure vary significantly across courses as do scheduling flexibility, certification and quality assurance.

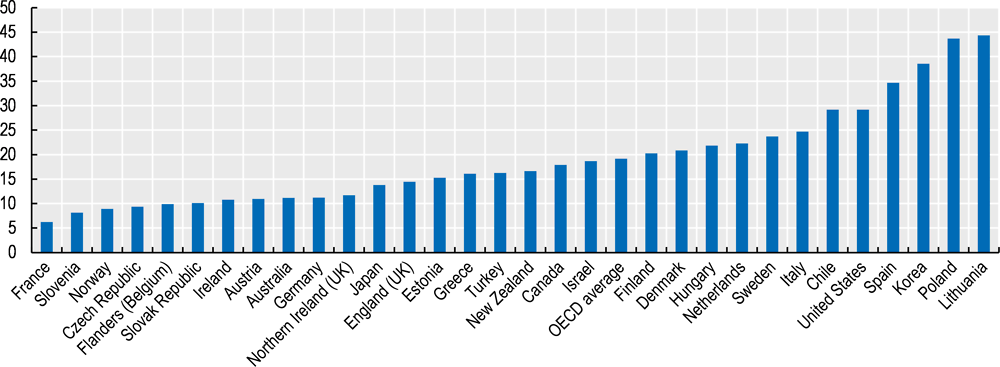

Despite its potential, however, data prior to the current crisis suggest that, in normal times, few adults take advantage of online learning as a means to train (OECD, 2019[3]). Only one in five participants in non-formal training took part in an online course. However, the share of participants training online varies significantly across countries, ranging from just 6% in France to over 40% in Lithuania and Poland (Figure 2).

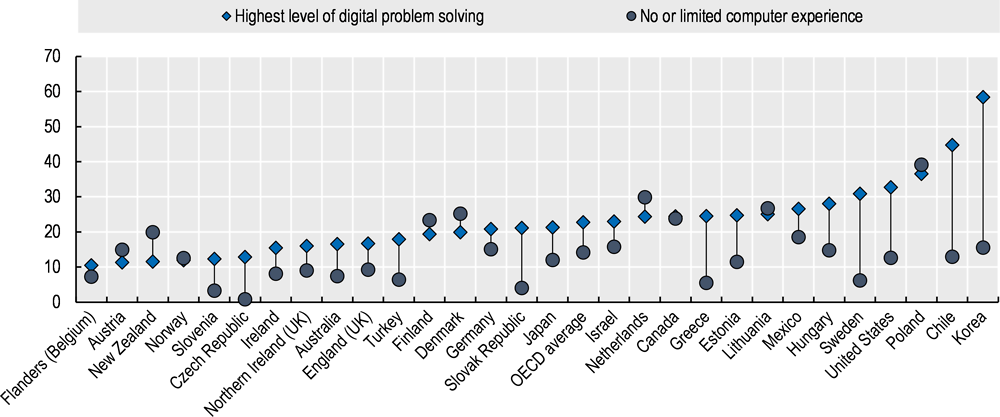

Inclusiveness is one of the key concern when it comes to online learning. While online courses could make access to training easier for disabled adults or for those living in rural communities, the pre-requisite of basic digital skills and devices, as well as a reliable internet infrastructure can limit access significantly. Data on distance learning from the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC)3 show that, in most countries, training participants with high digital problem solving skills are more likely to choose distance learning than adults with little ICT knowledge (Figure 3). In the OECD on average, 23% of training participants with high digital problem solving skills participated in online learning compared with only 14% of training participants with few ICT skills. There are exceptions and some countries have been able to successfully engage adults with limited digital skills in distance learning. In the Netherlands and New Zealand, the incidence of distance learning among adults with little ICT knowledge surpasses that for adults with high digital problem solving skills. In addition to more successful outreach campaigns, this could also reflect the lower ICT requirements of the online learning on offer or the use of offline correspondence courses.

To put these figures into perspective, on average across OECD countries, only 5% of adults score at the highest level of digital proficiency in PIAAC while about 15% of adults lack even the most basic computer skills (OECD, 2019[4]).

Information on whether training happened face-to-face or at a distance is only available for non-formal training. Distance learning includes correspondence courses, although the share of these courses is now minimal in most OECD countries. Data for Hungary, Mexico and the United States refer to 2017. Data for Data for Chile, Greece, Israel, Lithuania, New Zealand, Slovenia and Turkey refer to 2015. For all other countries, data refer to 2012.

Source: OECD Secretariat calculations based on the Survey of Adult Skills, PIAAC (2012, 2015, 2017).

Note: Digital problem solving refers to problem solving in technology-rich environment as assessed in the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC). Proficiency in this domain is measured in four levels, ranging from Level 3 (“Highest level of digital problem solving” in the figure) to Below Level 1, along with a group of Individuals who did not take part because their ICT knowledge was too poor (“No or limited computer experience” in the figure). Information on whether training happened face-to-face or at a distance is only available for non-formal training. Distance learning includes correspondence courses, although the share of these courses is now minimal in most OECD countries. Data for the Hungary, Mexico and the United States refer to 2017. Data for Data for Chile, Greece, Israel, Lithuania, New Zealand, Slovenia and Turkey refer to 2015. For all other countries, data refer to 2012.

Source: OECD Secretariat calculations based on the Survey of Adult Skills, PIAAC (2012, 2015, 2017).

Moving training online during the COVID‑19 crisis

As the crisis unfolds, a significant share of ongoing training, originally provided face-to-face in a classroom is being adapted for online delivery. This includes formal training – e.g. training provided at universities or vocational colleges – as well as some publicly provided non-formal training – e.g. training for jobseekers.4

Formal classroom-based training has been maintained in most countries through online delivery. To contain the spread of the virus, schools, colleges and universities have been shut down in the vast majority of countries. With few exceptions, courses have been moved online to provide continuity. This shift affects all adults participating in formal training such as early school leavers returning to education to obtain school-leaving qualifications, those studying towards a university degree after a spell in the labour market, and those reskilling by attending college courses or through vocational training.

Vocational programmes characterised by work placements, have been negatively affected during the lockdown period. As work placements are no longer possible in most cases and hands-on training cannot easily be delivered online, most programmes have simply been interrupted. Spain and South Korea have extended training periods to allow for gaps during lockdown, while Austria, Germany, Ireland and Switzerland have allowed employers to furlough their trainees by extending the coverage of short-term work schemes (OECD, 2020[4]). However, some countries have introduced measures to preserve parts of work-based learning through online instruction:

In many countries with mixed programmes – including both off-the-job and on-the-job training – providers have been allowed to bring forward the off-the-job component and postpone work placement. The Australian Skills Quality Authority has recommended that training providers re-sequence their training to deliver theoretical training first on an online basis (https://www.asqa.gov.au/COVID-19). England has allowed shortening the work-based components where possible and replacing with longer off-the-job instructions, through online learning. Apprentices who have already undertaken a sufficient number of hours of training with an employer are allowed to complete their programme through online learning. Some countries, like Spain, have provided flexibility to providers to decide how to re-organise vocational programmes.

In Italy, Italymobility – an initiative of the Centro Studi “Cultura Sviluppo”, a leading not-for-profit organisation in the TVET sector – has developed virtual internships in response to the COVID‑19 lockdown (http://italymobility.com/). Virtual internships allow implementing real work experiences at a distance executing real tasks with a tutor and a concrete pedagogical support within a specific IT learning infrastructure. This solution covers primarily professions related to digital technologies – e.g. web designer, social media marketer, software developer – but also comprises a range of activities belonging to ‘traditional jobs’ – e.g. bookkeeper, interior designer, mechanical manufacture designer.

In the state of Santa Caterina (Brazil), apprenticeship training provided by SENAI – the National Service for Industrial Training, a network of not-for-profit secondary level professional schools established and maintained by the Brazilian Confederation of Industry – continued through the use of virtual reality. In some cases, work tools were shipped to the students’ address so they could practice during virtual sessions with trainers located in training labs, in full respect of social distancing rules.

In Switzerland, some apprenticeships have continued online but the move required amending of apprenticeship contracts, which explicitly excluded online provision for work-placements.

#workbasedlearning and #apprenticeships are hard to pursue through #onlinelearning

Public Employment Services (PES) have continued to provide jobseekers’ training through digital channels during the crisis. Most OECD PES suspended the provision of face-to-face training shortly after the introduction of confinement measures. Some countries have replaced this with online training solutions that were already available prior to the crisis (e.g. in Estonia, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, some regions of Italy, or the three regions of Belgium) with minimal investment (OECD, 2020[5]). Other countries have boosted the options of training available online. In Denmark, a law was changed to allow municipalities to offer new digital qualification courses and in France, over 150 new training courses have become available online on the “Emploi Store”. Sweden will use part of the extra funding allocated to the PES and other key players to strengthen online learning and Internet-based education.

In some cases, PES are collaborating with private training providers to retrain jobseekers for occupations in high demand during the crisis. The Estonian PES, in co-operation with the relevant stakeholders, has been able to quickly develop e-learning for care workers, who are in high demand during the crisis. In the United States, the Rapid Skilling programme aims to transition several displaced vocational and technical workers into currently in-demand occupations. The programme stems from a collaboration between 180skills – a provider of technical and employability training for the manufacturing and logistics sectors in North America – State governments, academic partners, and employers who are in urgent need of skilled workers. The industries served include Manufacturing, Logistics and Distribution, Retail, and Industrial Safety. The innovation consists in the use of competency-based online courses, curated into ultra-short-term programmes with the minimal amount of skills for initial employment. The programmes are particularly aimed at low-skilled, low-income adults and are delivered at a very low cost.

Other public training centres serving adults from disadvantaged groups – notably the low-skilled, the inactive or those with an immigrant background – varied in their ability to continue their training online. Basic skills training, such as language, basic literacy and numeracy training, was more often maintained than hands-on job-related training. In Italy, the Provincial Adult Education Centres (CPIA), which typically provide basic skills training to disadvantaged adults, continued to function through video conferences. Similarly, the Het Begint met Taal Foundation in the Netherlands – a national platform supporting 170 organisations that offer language coaching (https://www.hetbegintmettaal.nl/) – moved their training offer online. In England, the West Midlands Combined Authority that is responsible for the region’s GBP 126 million adult education budget, has turned classroom training modules, including those focusing on employability, functional maths and English, online. On the other hand, training was less often maintained at training institutions focused on practical job-related training. For instance, the Centres for Socio Professional Integration (CISP) in the Walloon Region of Belgium that provide hands-on training to prepare low-skilled adults for jobs in sectors such as hospitality, catering and construction, interrupted training provision.

School-based formal education has been moved to online delivery;

Work-based learning and apprenticeships have been negatively affected by lockdown; in most cases, only off-the job components have been pursued;

The most efficient Public Employment Services have been quick to transition jobseekers’ training online; some re-focused training on occupations in high demand due to COVID‑19;

Public support for online training provision has been crucial for many training providers and end users, spanning from sharing platforms to free resources to digital-skills support for teachers and learners;

Governments, public employment services, and social partners have campaigned for online training take up during lockdown

Government support was crucial to maintain training through online provision

Support from government to guarantee training continuity through online learning was provided in several countries and took various forms.

Government support through shared resources is crucial for training providers to move their offer to #onlinelearning

Some countries have created platforms for training providers to share existing resources and facilitate online provision; others have exploited existing ones:

South Korea has encouraged the use of its virtual training platform – Smart Training Education Platform (STEP – https://step.or.kr/). The platform enables learning providers to upload their course content, in addition to 300 existing courses already available. This is being supported further by subsidies and quality assurance mechanisms.

In France, the Minister of Labour, which is also in charge of vocational training, has developed a platform to make resources available to professionals in the sector to facilitate continuity in education (https://travail-emploi.gouv.fr/formation-professionnelle/coronavirus/formation-a-distance/). Several partners of the Ministry of Labour have volunteered to share educational training content free of charge. Among the available content, there are the MOOCs by AFPA – a training provider focused on the food professions (cooking, pastry making, etc.) – and access to CNED (National Centre for Distance Learning) materials for core subjects in the technological fields. In order to support trainers in distance education and training, the Ministry has also published a list of technical solutions, including web conferencing tools, collaborative tools, server links and clouds and other tools necessary to allow training actors to ensure continuity in education.

In Germany, the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports in the Federal State of Baden-Württemberg is offering selected providers to benefit from their digital learning platform (Digitaler Weiterbildungscampus – https://www.digitaler-weiterbildungscampus.de/) to help move learning online. The platform is operated by the private company and provides a central infrastructure for co-operative, adaptive and skill-oriented teaching and learning. It is not specific to one institution, i.e. content can be shared across institutions. The Ministry co-funds 50‑70% of the costs of using the platform for providers. Eligible for the funding are learning providers that are part of the Alliance for Lifelong Learning and other recognised providers of general or vocational continuing education in Baden-Württemberg

Several countries have provided free or subsidised online training for the lockdown period:

On the same platform for online learning resources mentioned above, France is providing online VET courses free of charge for a period of three months, including the core curriculum of vocational schools and main training courses for professional qualifications; similar initiatives have been set up in Ireland, Belgium, Spain, Croatia and Romania, among others.

Sweden, through Crisis package for jobs and transition, has put forward plans to increase funding and additional support to online learning providers in higher VET.

Many countries are providing support for teachers and trainers through online training, workshops and seminars (UNESCO, 2020[6]; WorldBank, 2020[7]). These aim to upgrade the ICT skills of teachers and trainers and to assist with the preparation of online learning materials. The support measures also aim to assist with the preparation and delivery of online sessions as well as with the use of online platforms.

Several countries have set up online portals to provide support for teachers. In Denmark, the Ministry of Education has set up a portal to support teachers with digital resources for online teaching and learning (https://emu.dk/). In Chile, the Ministry of Education provides management and technical support to teachers on the use of online platforms and the development of online materials, on teaching methods, on evaluation and on how to gather feedback from students through surveys (https://www.aptus.org/). In Ireland, the Professional Development Service for Teachers provides access to a collection of resources for teachers in order to provide continuity to students during the COVID‑19 crisis.

Other countries have partnered with private providers or are providing access to existing teaching resources free of charge. In Canada, the Ontario Schoolboard has partnered with Apple to provide videos, apps and books to help teachers build engaging lessons for students at home. Free one‑to-one virtual coaching by professional learning specialists is also available.

In some cases, certified teaching courses are made available online. In Mexico, the government is dedicated to supporting teacher training under the digital education and training programme (http://formacionycapacitaciondigitales.televisioneducativa.gob.mx/). This translates to supporting teachers with ‘digital education and training’ using MOOCs, online courses and online conferences. Certification is provided to teachers who successfully complete these courses.

Some programmes for digital skills assistance were introduced to support users of online resources. France launched a website to help adults who are struggling with digital tools in their daily life or for work (https://solidarite-numerique.fr/).

Campaigns for online training take up during lockdown

In some cases, incentives to take up training during short-time working schemes5 have also been introduced.

Beyond maintaining pre-existing training, some governments also encouraged adults to undertake new training during the lockdown, especially for workers on short-time work schemes, through online learning.

In France, the government has extended financial support for training, previously available for the unemployed only, to workers on short-time work schemes. Under the extension, employers are reimbursed 100% of the cost of training, applicable to all online training courses, except for compulsory training – e.g. health and safety – up to EUR 1 500 (Fiche Ministère du Travail du 20 Avril 2020).

Governments, PES and social partners have encouraged adults to retrain and #keeplearning while they #stayathome

PES are also supporting online training provision during the crisis by disseminating the information on online training on their websites, YouTube and Twitter accounts (OECD, 2020[5]). In several countries, PES have also played a role to accompany and support private training providers with the use of online tools for training provision.

In the United Kingdom, Unionlearn – an initiative by the Trade Union Confederation to support skills development at work – has launched their new Learning@home Campaign (https://www.unionlearn.org.uk/learning-home). The campaign is designed to support adults who are currently working or furloughed at home due to COVID‑19. The campaign provides access to online training, learning resources, and tips on how best to undertake learning at home.

Looking ahead: key lessons from the crisis

The initiatives above underscore the potential of online learning to become a more permanent feature of adult learning systems. However, they also highlight some important limitations that will need to be addressed to broaden access to online learning opportunities and enable more adults, particularly the unemployed and the low-skilled, to participate in training:

Developing basic digital skills will be instrumental to the mainstreaming of online learning. Users of online learning are primarily highly educated adults with strong digital skills. Several countries launched programmes to equip adults with basic digital skills prior to the crisis. In the United Kingdom, the Digital Skills Partnership brings together government and national and local employers and charities in an effort to address digital skills gaps in a more collaborative way. As of 2020, low-skilled adults in the United Kingdom have access to fully funded digital skills programmes, in addition to the already existing maths and English programmes. In Hungary, improving the digital skills of disadvantaged adults is part of the new national development plan (https://www.palyazat.gov.hu/). The goal is to provide digital skills training opportunities to 260 000 low-skilled adults from disadvantaged regions.

Motivating online learners is key to retention. Evidence from MOOCs shows completion rates as low as 10% (Rivard, 2013[9]; Murray, 2019[10]) In addition to basic digital skills, online learning requires autonomy and self-motivation. In the context of the crisis, many apprenticeships and VET providers have put emphasis on building and maintaining motivation of online learners. Amazing Apprenticeships – the communication branch of Apprenticeships UK – provides several motivation webinars on its website. Digital badges are important to increase motivation (Credly, Knight and Manning, 2013[11]) as are options for interaction with other students and the teacher are also important to increase motivation. The Spanish Aula Mentor programme allows for this digital interaction.

Broadening the range of online courses is crucial to make online learning more inclusive. Few courses are currently available online and they tend to focus on the skills needed in white-collar jobs. In France, it is estimated that, prior to the crisis, only about 10% of training courses were accessible online. While the crisis will have increased that share, training for crafts-related occupations and training involving a work-based component remains difficult to deliver online. To overcome these limitation, training providers are turning to Artificial Intelligence (AI). AI can help develop simulations and virtual reality experiences that allow for a “learning by doing” experience (Minocha, Tudor and Tilling, 2017[12]; Hwa Choi, Dailey-Hebert and Simmons Estes, 2016[13]). In the United States, Morgan State University is using virtual reality to deliver its nursing programme building on its work on the use of extended reality in teaching and learning (Pomerantz, 2019[14])

Training teachers to deliver online courses effectively is important to raise the quality of online courses. Teachers used to face-to-face delivery may be ill equipped to provide training online. This is particularly evident in the context of the COVID‑19 crisis, when untrained teachers have been forced to deliver their courses online and faced difficulties such as limited digital literacy and limited training in online teaching methods. To support teachers, many training providers in the United Kingdom are building modules to increase teachers’ confidence, retention and motivation into their online learning strategies. In Korea, the Ministry of Employment and Labour is planning to develop and operate a curriculum to equip teachers and managers at training institutions with the skills needed to shift the training offer to online delivery.

Developing effective testing methods and certificates is important to ensure that online training, both formal and non-formal, is valued in the labour market. Tests, quizzes and assessments are becoming an important part of online training courses. They help consolidate learning and measure the effectiveness of the learning course. Several initiatives already exist. In France, the PIX platform (https://pix.fr/) allows users to take tests in 16 digital skills domains and share their skills profile directly with employers. It is also possible to obtain certifications of the digital skills (through tests at PIX centres). An innovative solution is the adoption of digital badges: portable visual tokens containing information about the individual, the badge issuer (education or training provider), criteria for obtaining the badge, and supporting documents when available. In the formal sector, many countries are reflecting on how assessments of training provided online could be undertaken. During the COVID‑19 crisis, most countries have cancelled exams and are planning to evaluate students only based on course work conducted prior to lockdown, hence prior to the deployment of online provision. Countries that maintained evaluations, planned to hold them face-to-face. The discussion of how the evaluation could take place online remains open.

Establishing quality assurance mechanisms for online learning is essential to ensure that online courses provide value for money/time to participants. It remains an open question whether online courses require an ad-hoc quality assurance system. Those who support tailored quality criteria, have proposed a plethora of quality assurance methods for online learning but few programmes exist on the ground and none adopted at the national level (Butcher, 2013[15]; Esfijani, 2018[16]). In the United States, the (privately owned) Quality Matters Programme has established national benchmarks for online courses and has become a “nationally recognised, faculty-centred, peer process designed to certify the quality of online courses and online components”. In Europe, the European Association of Distance Teaching Universities (EADTU) has created OpenupEd, one of the largest MOOC providers for higher education. The OpenupEd partners have identified eight features to which supported courses need to adhere: Learner-centred, Openness to learners, Digital openness, Independent learning, Media-supported interaction, Recognition options, Quality focus, Spectrum of diversity. In 2014, the EADTU created a quality label for MOOCs tailored to both e-learning and open education (Rosewell, 2014[17]). More generally, the COVID‑19 crisis will provide a valuable natural experiment on the employment and wage returns of online learning compared to face-to-face instruction. Results from this assessment would help identify the features of online learning provision that are most likely to lead to positive outcomes for participants, all else being equal. They would also shed light on whether these features differ from those identified for face-to-face instruction, justifying or not the need for an ad-hoc quality assurance system.

Strengthening the digital infrastructure is a fundamental context factor for online learning to be a viable option in the delivery of online learning. Unequal access to the Internet risks exacerbating existing inequalities in education and training. During the COVID‑19 crisis, several countries considered starting to fund Internet access as a basic service to ensure access for all citizens, including those living in rural regions or from poorer economic backgrounds. In Ontario, school children and families in need were given free iPads and Internet access. Support for teachers to adapt their courses to online environments in an equitable way is also crucial, e.g. not relying too heavily on real-time online learning so as not to disadvantage students whose internet infrastructure is of a poor quality, who use a shared device at home, or who have other family members who need the Internet bandwidth for other things (Lederman, 2020[18]).

Develop basic digital skills to support lower skilled adults in accessing online learning;

Motivate online learners to improve retention and completion rates;

Develop effective testing methods and certificates to ensure that online learning is valued in the labour market;

Broaden the range of online courses to include more blue-collar occupations;

Train online teachers to raise the quality of online courses;

Establish quality assurance mechanisms for online learning to ensure that online courses provide value for money/time to participants.

Strengthen the digital infrastructure and use teaching methods that minimise infrastructure needs.

Working with OECD

The OECD Skills team is currently engaged in a number of projects focused on various aspects of adult learning, including inclusiveness, responsiveness, quality assurance, certification and career guidance. To accompany this work, it has developed: the Priorities for Adult Learning dashboard, an interactive tool which allows countries to benchmark their adult learning systems against each other and the OECD average; and the Skills for Jobs Database to measure skills imbalances in over 40 countries and regions, in the OECD and beyond. The team is also about to embark on a major project analysing the potential of using AI in training provision. As discussed in this brief, AI has the potential to broaden participation in online learning by adapting the content and testing methods to the user. It also has the potential to broaden online learning beyond traditionally white-collar job. Country reviews on specific national priorities and challenges in adult learning and skills assessment and anticipation systems have already been conducted in 12 countries and offer tailored policy analysis and recommendations.

References

[15] Butcher, N. (2013), A Guide to Quality in Online Learning, Academic Partnerships.

[11] Credly, J., E. Knight and S. Manning (2013), The Potential and Value of Using Digital Badges for Adult Learners Final Report.

[16] Esfijani, A. (2018), “Measuring Quality in Online Education: A Meta-synthesis”, American Journal of Distance Education, Vol. 32/1, pp. 57-73, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2018.1417658.

[19] EUROSTAT (2016), Classification of learning activities (CLA) MANUAL 2016 edition, http://dx.doi.org/10.2785/874604.

[20] Fialho, P., G. Quintini and M. Vandeweyer (2019), “Returns to different forms of job related training: Factoring in informal learning”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 231, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b21807e9-en.

[13] Hwa Choi, D., A. Dailey-Hebert and J. Simmons Estes (2016), Emerging Tools and Applications of Virtual Reality in Education, IGI Global.

[18] Lederman, D. (2020), How the shift to remote learning might affect students, instructors and colleges, https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2020/03/25/how-shift-remote-learning-might-affect-students-instructors-and (accessed on 25 April 2020).

[12] Minocha, S., A. Tudor and S. Tilling (2017), Affordances of Mobile Virtual Reality and their Role in Learning and Teaching Conference or Workshop Item Affordances of Mobile Virtual Reality and their Role in Learning and Teaching, The Open University, http://oro.open.ac.uk/id/eprint/49441 (accessed on 29 April 2020).

[10] Murray, S. (2019), Moocs struggle to lift rock-bottom completion rates | Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/60e90be2-1a77-11e9-b191-175523b59d1d (accessed on 25 April 2020).

[6] OECD (2020), “Public Employment Services in the frontline for employees, jobseekers and employers”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/public-employment-services-in-the-frontline-for-employees-jobseekers-and-employers-c986ff92/.

[5] OECD (2020), “VET in a time of crisis: Building foundations for resilient vocational education and training systems”, VET in a time of crisis: Building foundations for resilient vocational education and training systems, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/vet-in-a-time-of-crisis-building-foundations-for-resilient-vocational-education-and-training-systems-efff194c/.

[3] OECD (2019), Dashboard on priorities for adult learning - OECD, http://www.oecd.org/employment/skills-and-work/adult-learning/dashboard.htm (accessed on 16 April 2020).

[1] OECD (2019), Getting Skills Right: Future-Ready Adult Learning Systems, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264311756-en.

[2] OECD (2019), OECD Employment Outlook 2019: The Future of Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9ee00155-en.

[4] OECD (2019), Skills Matter: Additional Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1f029d8f-en.

[14] Pomerantz, J. (2019), XR for Teaching and Learning, https://www.educause.edu/hp-xr-2. (accessed on 29 April 2020).

[9] Rivard, R. (2013), Researchers explore who is taking MOOCs and why so many drop out, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/03/08/researchers-explore-who-taking-moocs-and-why-so-many-drop-out (accessed on 25 April 2020).

[17] Rosewell, J. (2014), OpenupEd label, quality benchmarks for MOOCs, http://e-xcellencelabel.eadtu.eu/. (accessed on 29 April 2020).

[7] UNESCO (2020), “National learning platforms and tools”, https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/nationalresponses (accessed on 28 April 2020).

[8] WorldBank (2020), “How countries are using edtech (including online learning, radio, television, texting) to support access to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic”, Brief, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/edutech/brief/how-countries-are-using-edtech-to-support-remote-learning-during-the-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 28 April 2020).

Contact

Stefano SCARPETTA (✉ stefano.scarpetta@oecd.org)

Glenda QUINTINI (✉ glenda.quintini@oecd.org).

Notes

In the period 14 to 30 March 2020, 18 663 requests for participation in free online training programmes were received, compared to 5 145 in the same period last year (https://www.hildecrevits.be/nieuws/aantal-aanvragen-online-opleidingen-vdab-piekt/).

Formal training generally takes place at an institution that is part of the country’s regular education system and provides a qualification upon successful completion. Non-formal training is usually organised by employers, private training providers or professional organisations (EUROSTAT, 2016[19]). Among workers, informal learning – learning by doing or learning from colleagues and supervisors – accounts for a large share of learning activities, involving about 70% of workers in any given year, compared to 40% of workers who participate in non-formal training and 8% who undertake formal training (Fialho, Quintini and Vandeweyer, 2019[20]). Only formal and non-formal training are susceptible to be provided online. Informal learning by definition is not provided as part of a course. In addition, it is not clear how informal learning would have been disrupted by the lockdown and this assessment goes beyond the scope of this brief.

The data extracted from the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) refers to participation in non-formal distance learning, hence could include correspondence courses. As these courses have become rare, the statistics presented are a good, albeit not perfect, proxy for the incidence of online learning among participants in non-formal training. See also the definitions presented in Box 1.

Although figures are not available, it is very likely that non-formal training that was being provided or planned by employers would have been interrupted and rescheduled, particularly if it was being provided in-house or by small training providers without sufficient capacity to convert it into online instruction. It is less clear how informal learning, a crucial form of learning for workers, would have been affected by the lockdown. In jobs where teleworking is possible, learning by doing and possibly learning from colleagues and supervisors is likely to.have continued. By definition, this is not the case for workers on short-time work schemes or those made redundant.

Short-time work compensation schemes provide additional funds so that employees can reduce their hours of work without a proportional reduction in their take-home pay. The employees earn less than they do when in full-time employment, but more than they would receive in unemployment benefits.