Abstract

This brief, prepared by the Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat, provides important contextual information on a region that was already grappling with conflict and a food and nutrition crisis prior to the Coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak. 17 million people are expected to be in food crisis situation or worse between now and the upcoming lean season if appropriate measures are not taken and armed violence is causing an unprecedented humanitarian emergency in the Sahel. With the spotlight now on Covid-19, pre-existing crises run the risk of being neglected.

In this context, this brief takes stock of some of the potential impacts of the pandemic and outlines a number of policy implications to help support government action. It highlights the importance of putting the informal economy and local actors and initiatives front and centre of response strategies, increasing synergy and co-ordination in the face of multiple crises, accelerating continental integration, as well as reaffirming the centrality of food systems.

Introduction

Spiralling conflict, pervasive poverty and acute food insecurity are all part of the West African landscape. Now, a global pandemic, together with an emerging economic crisis, will make a very bad situation even worse.

"Africa must prepare for the worst", the World Health Organisation (WHO) warned from the outset. Governments reacted quickly, announcing a series of measures to contain the virus, yet these measures have trade-offs, particularly for vulnerable populations. Regional organisations, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA), are mobilising efforts and have nominated the West African Health Organisation (WAHO) to lead the region’s response to the pandemic. Countries are nevertheless grappling with some serious practical challenges. How do people protect themselves if they have limited access to handwashing facilities? Or, if they live in highly dense urban agglomerations, with little possibility for social distancing? How do they manage if they are living in conflict-affected areas where health centres have been destroyed? Or if they are displaced, living in camps, with limited hygiene and sanitation facilities? What happens when confinement translates into a loss of income and livelihoods? And what happens to the most vulnerable who are struggling to survive existing food and security crises?

The hope of epidemiologists lies in the youth of the population; two-thirds of West Africans are under 25 years of age (UN, 2019) and the young appear less likely to die from infection. But even good news comes with a caveat: millions of vulnerable people are likely to have compromised immune systems due to chronic diseases, malnutrition, or other infectious diseases such as tuberculosis or malaria. At the time of publication, it is impossible to say whether the epidemic will spread on a large scale or if it will claim a large number of lives. Uncertainty is all the greater without widespread testing. Be that as it may, the consequences on West African economies and societies will be far-reaching and long-lasting.

This brief is organised as follows:

First, it provides a contextual overview of pre-existing crises and vulnerabilities.

Second, it outlines some of the key measures taken by governments to stem Covid-19.

Third, it assesses some of the impacts of the pandemic.

Finally, the brief provides a set of policy implications.

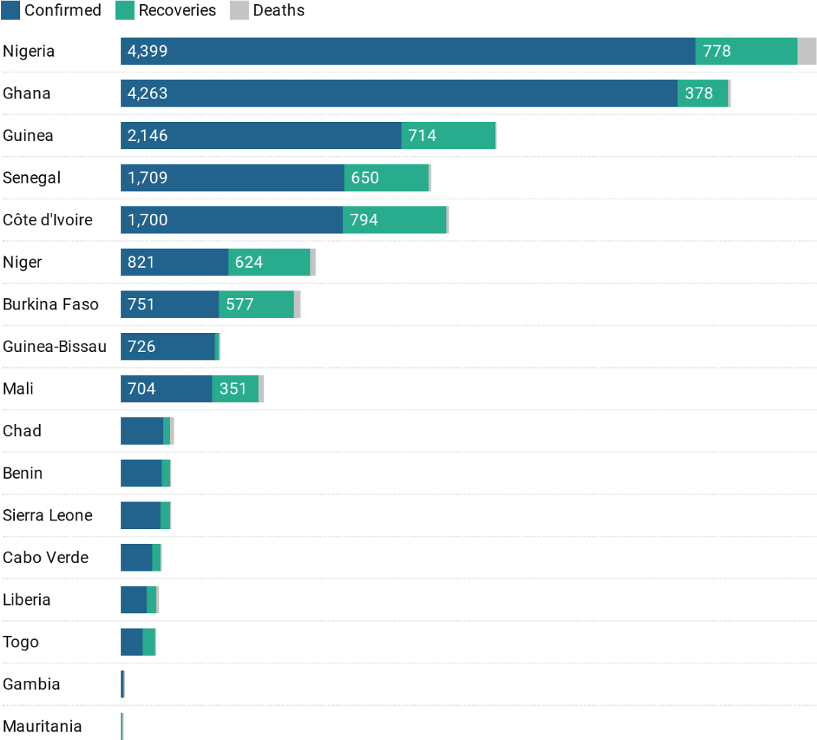

At the time of drafting, more than 18 000 cases and 400 deaths have been recorded in West Africa according to Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. In late February, the first case was recorded in Nigeria. Within one month, Covid-19 had spread to all 17 countries. The exact number of cases, however, is very uncertain, particularly given the low levels of testing. Death tolls are also unreliable as they may exclude people who did not die in a hospital, or who died before they could be tested.

Note: Data as at 10 May 2020. Daily updates are available at: www.oecd.org/swac/coronavirus-west-africa.

Source: Johns Hopkins University & Medicine 2020.

A challenging context

Health systems

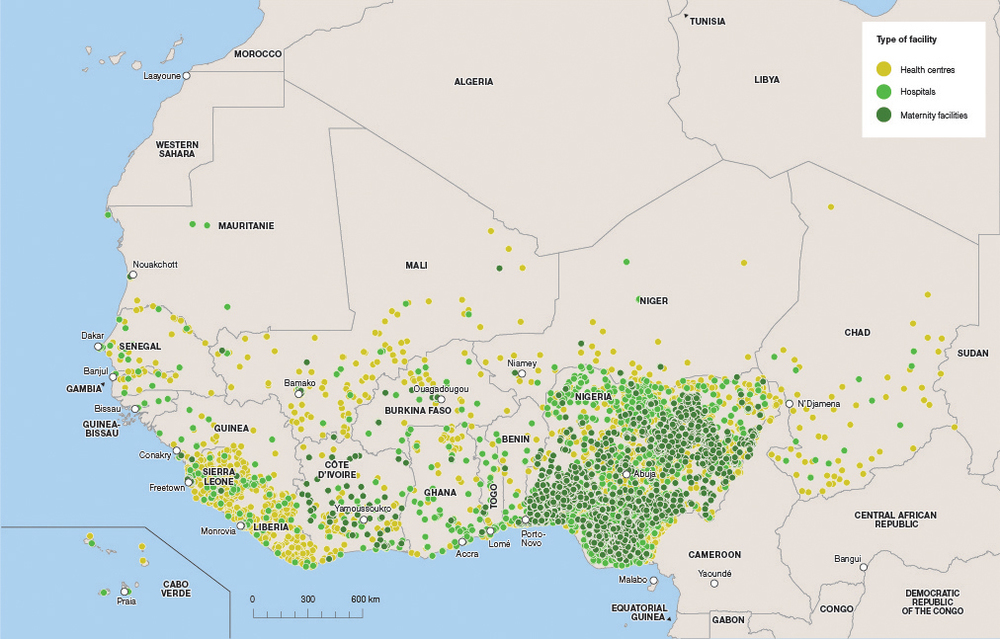

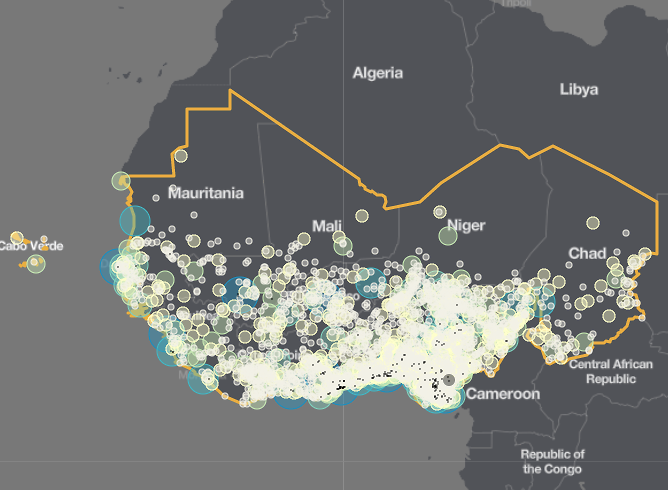

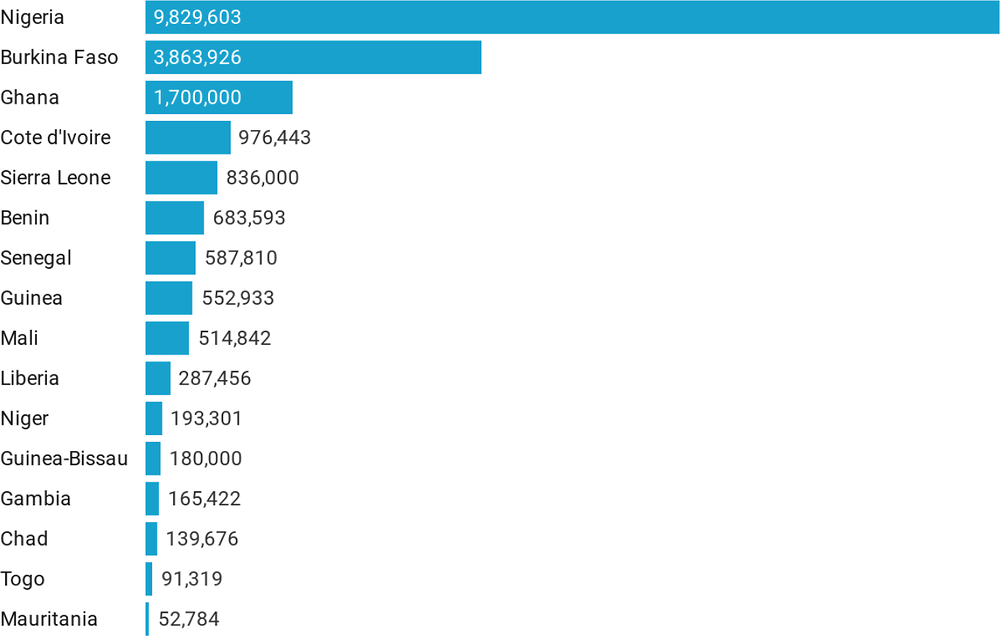

If prevention and containment measures fail, Covid-19 could swiftly overwhelm the fragile health systems across the region (Yabi, 2020), leaving little room for continuity of treatment for other diseases such as HIV, malaria and tuberculosis. In a recent report, Businesses and Health in Border Cities, the Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat highlights the lack of distribution of health infrastructure across countries (OECD/SWAC, 2019a). In 2017, around 46 000 health establishments, including hospitals, health centres, and maternity facilities were observed1, with 80% concentrated in Nigeria (Map 1). Around 70% of these establishments were modestly equipped health units serving local populations. Only hospitals, however, are likely to accommodate the most serious cases of Covid-19 and they are relatively few in number, particularly considering the populations of affected countries; in Burkina Faso, 35 hospitals serve a population of 19.8 million (UN, 2019).

Source: OECD/SWAC 2019a

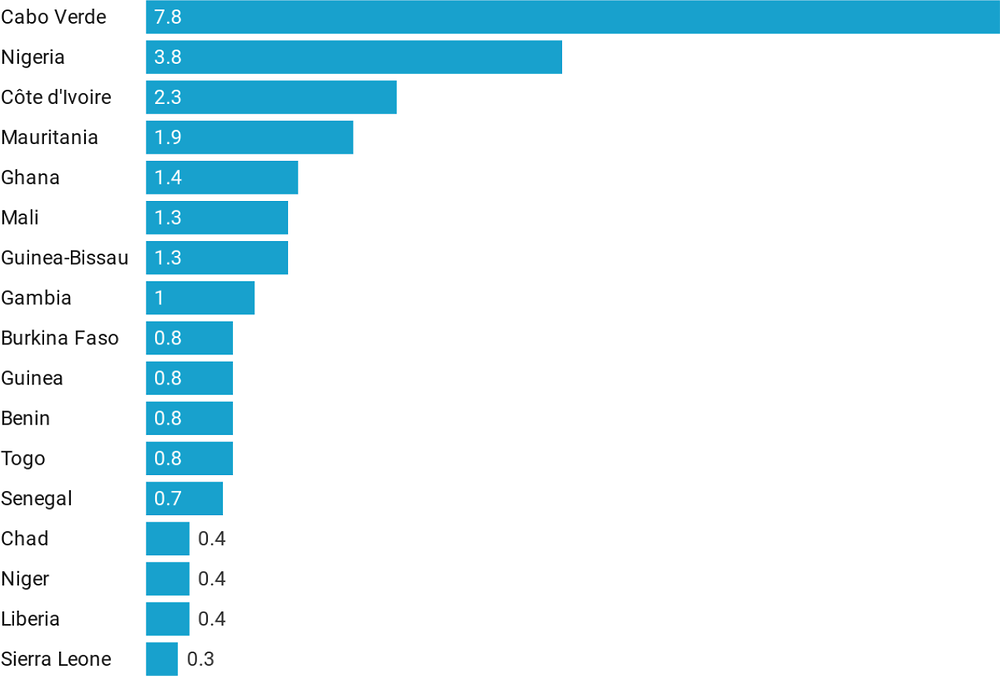

The lack of medical equipment to treat infected patients seeking emergency care is also glaring. In Burkina Faso, there is an estimated 11 ventilators for its population of almost 20 million people (IRC, 2020). The number of health professionals is also insufficient (Figure 2); there are 0.8 doctors for every 10 000 people (WHO, n.d.), compared to 35 across OECD countries (OECD, 2019). Availability of protective personal equipment (PPE) is another issue. In the preparedness assessments collated by WHO (2020), only 7 out of the 12 countries surveyed in the region (58%) had PPE available and accessible to health professionals. This is particularly concerning considering the effect of the Ebola outbreak, which killed over 8% of the health workforce in Liberia alone. As of 4 April 2020, over 100 doctors and nurses have died fighting Covid-19 across the world (WEF, 2020). If this scenario occurs in West Africa, there will not be much capacity left.

Note: Data is from the latest available year ranging from 2011-18.

Source: WHO n.d.

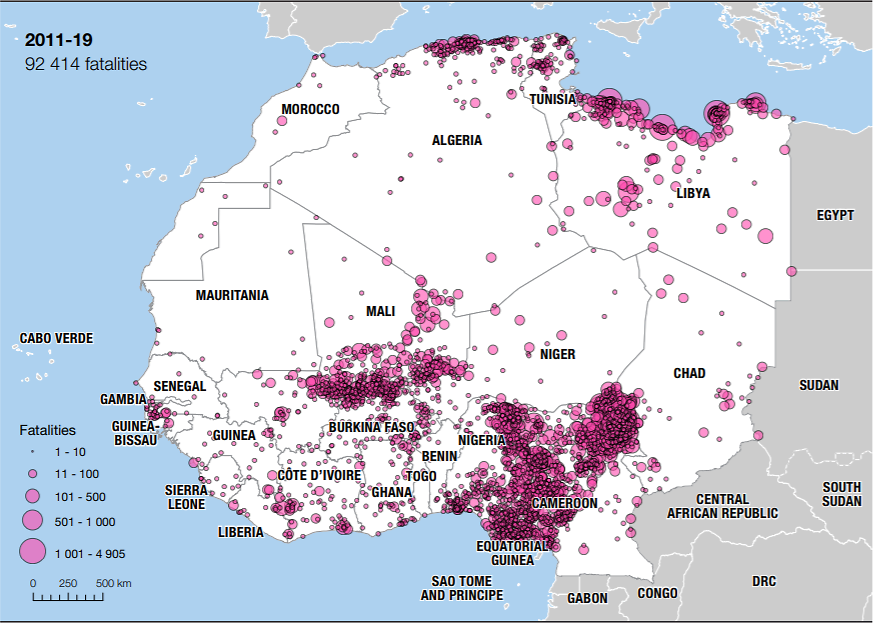

Conflict

Before Covid-19 hit, the Sahel was already facing a security crisis with the worst humanitarian needs in years. Since 2011, 20 900 acts of violence have killed more than 92 000 people in North and West Africa, with thousands more wounded (Map 2). The impact on the affected populations is dramatic, compounding food insecurity and malnutrition, and significantly increasing the number of internally displaced persons (IDPs). IDPs across Burkina Faso, Mali, and western Niger reached 1.1 million as of February 2020 (OCHA, 2020), a four-fold increase in one year. Such is the situation across the Lake Chad basin and in the Liptako-Gourma area. Armed groups are directly targeting schools, forcing health centres to close and depriving communities of critical services. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), more than 3 600 schools and 241 health centres are closed or non-operational due to insecurity in Burkina Faso, Mali, and in the regions of Tahoua and Tillaberi in western Niger. Some 7.5 million people (OCHA, 2020) in the affected regions are dependent on humanitarian assistance for survival. The conflict is in many cases a symptom of deeper issues — widespread poverty and inequality, poor governance and institutional capacity, a lack of public services and high unemployment, among others.

Source: OECD/SWAC 2020a.

These conflict-affected areas are home to extremely vulnerable populations, including internally displaced persons, refugees, migrants, marginalised groups, and people in hard-to-reach areas. Many live in camps and crowded environments that lack adequate sanitation facilities to prevent contamination from Covid-19. Many lack access to healthcare and basic social services, and many do not receive accessible information in order to understand how to protect themselves from infection. These conditions provide the perfect breeding ground for the virus, adding an additional layer of challenges to those that these populations are already facing.

Food and nutrition

The state of food and nutrition security was already alarming before the pandemic. In December 2019, 9.4 million people were estimated to require emergency food assistance according to the Food Crisis Prevention Network (RPCA, 2020a), with the primary cause being insecurity. At that time, global acute malnutrition rates already exceeded the emergency threshold (>15%) in several conflict-affected areas of Burkina Faso, Chad, and Mali. IDPs and host communities had seen their vulnerabilities increase in terms of food insecurity, water, hygiene, sanitation, and health. Similarly, humanitarian access was already experiencing difficulties due to armed groups undermining the provision of food assistance.

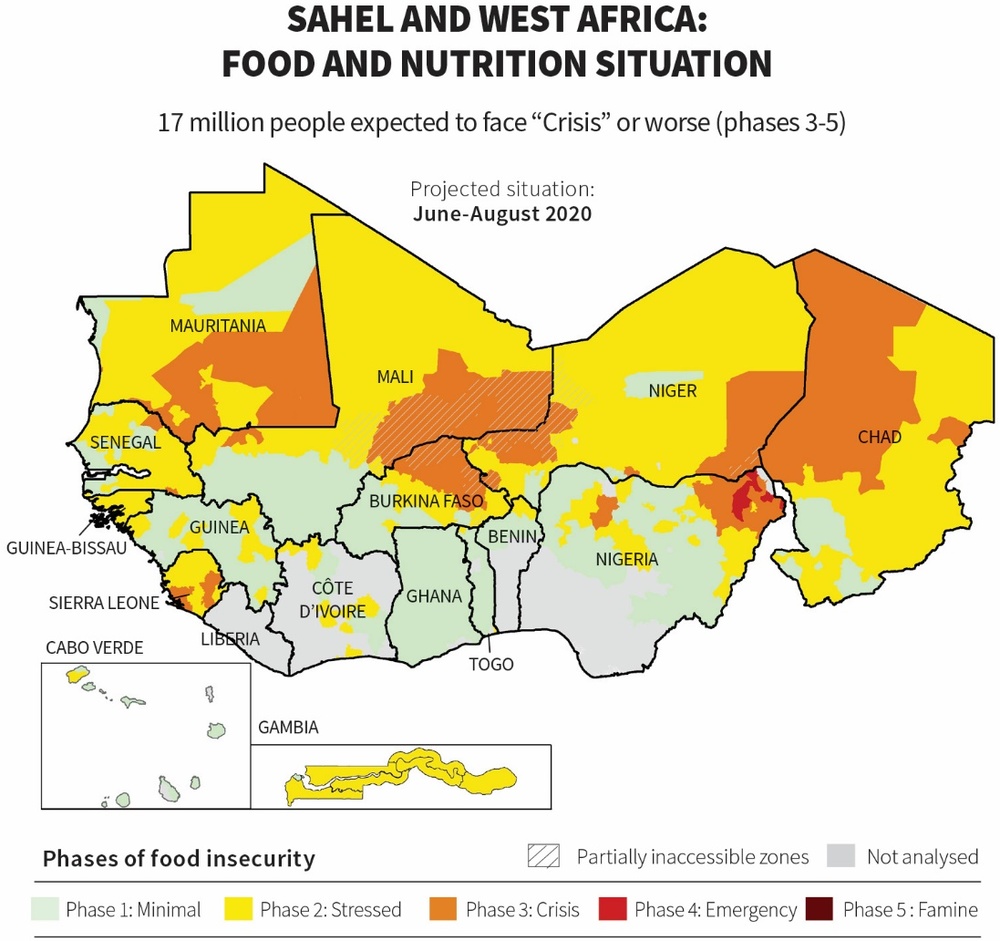

In April 2020, the RPCA declared the situation an unprecedented humanitarian crisis as 11.4 million people are currently in need of immediate food and nutrition assistance. If appropriate measures are not taken, 17 million people (RPCA, 2020b) (Map 3) will be facing a crisis situation or worse between now and the lean season. This is more than double the number of people usually affected, and the primary cause is insecurity. In addition to conflict, the risk of a desert locust outbreak is on the horizon. Locusts are currently ravaging East Africa, if they attack West Africa, it will make matters worse, threatening agri-food systems while armyworms are devastating crops.

Against this backdrop, Covid-19 further aggravates the on-going food and nutrition crisis. Over 50 million additional people (RPCA, 2020b) could fall into a food crisis due to the combined effects of insecurity and the consequences of sanitary measures, in particular confinement, market closures, barriers to trade, etc. At the same time, acute malnutrition persists affecting nearly 2.5 million children under 5 years of age. The virus may prove particularly dangerous for these food insecure and malnourished populations. With weakened immune systems, they have reduced ability to fight infections. The survival rate of patients suffering from Ebola, for example, was affected by their “preceding nutritional status” or the baseline nutritional health of people affected by the virus (WHO/UNICEF/WFP, 2014). Measures to stem Covid-19 further exacerbate these vulnerabilities in many ways, not least by undermining the efforts of humanitarian organisations in providing emergency food assistance.

Note: For more information, visit www.food-security.net.

Source: Cadre harmonisé analysis, regional concertation, Niamey, Niger, March 2020

© Food Crisis Prevention Network (RPCA), map produced by CILSS/AGRHYMET

Urbanisation

The biggest impact of Covid-19 may well be felt in densely populated urban areas, where the spread of the disease is fastest. The region’s population increased from 186 to 387 million between 1990 and 2017, a more than two-fold increase (World Bank, 2020). This growth has driven urbanisation, not only causing the size of large cities such as Abidjan, Accra, and Lagos to considerably extend, but also leading to the emergence of a constellation of secondary cities in previously rural areas (Map 4). About 45% of the West African population now lives in cities (OECD/SWAC, 2016). With 133 million city dwellers, West Africa constitutes the most important urban cluster in Africa (OECD/SWAC, 2020b). Alongside increasing urbanisation, food systems have been transforming. Supply chains are now geared towards meeting the food needs of cities. However, “feeding cities”, brings with it certain challenges, such as urban encroachment threatening agricultural land and effective waste management. Similarly, the quality of road infrastructure, markets, transportation, and other supply chain systems present major challenges for food security in cities. Restrictions related to Covid-19 could prevent cities and metropolitan areas from sourcing the food they need.

Source: OECD/SWAC 2018, Africapolis (database)

Measures

Collective preparedness

The African Union (AU) and its Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) are leading the continental response to Covid-19 with two overarching goals: i) preventing severe illness and death and ii) minimising social disruption and economic consequences (AUDA-NEPAD, 2020). They convened a meeting of African Health Ministers on 22 February (AU, 2020a), set up an African Taskforce for Coronavirus (AFCOR), developed a Joint Continental Strategy for the Covid-19 Outbreak (AU, 2020b) and established a Continental Anti-Covid-19 Fund (AU, 2020c) for African Union member states to provide an immediate initial contribution of USD 12.5 million. The African Union Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD) released a white paper, Covid-19 & Other Epidemics: Short & Medium Term Response (AUDA-NEPAD, 2020), emphasising the impact of the many “known unknowns” of the pandemic.

Regional organisations, ECOWAS (2020a) and UEMOA (2020), are providing support to member states through the development of regional strategic plans, a co-ordination platform, as well as a committee to monitor the evolution of the pandemic. The West African Health Organisation (WAHO, 2020), a specialised institution of ECOWAS, is leading the regional response in terms of co-ordination, collaboration and communication across the 15 member states of ECOWAS. The WAHO has drawn up a Regional Strategic Plan and with the financial support of ECOWAS and international partners; has purchased and dispatched test kits, PPE, and medicine; and is working to deploy personnel and epidemiological surveillance and data collection tools, strengthen the capacity of reference laboratories and train technical personnel (ECOWAS, 2020b).

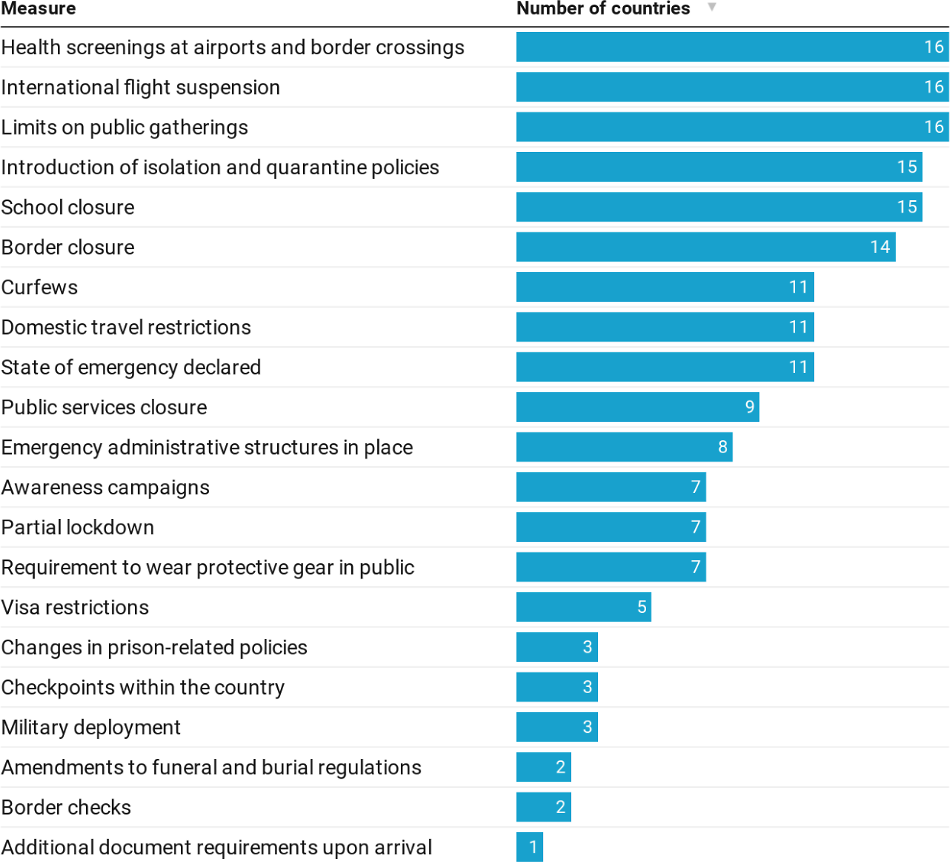

Containment measures

Governments have adopted sweeping measures to curb the spread of the virus including closing borders, imposing travel bans, prohibiting mass gatherings, shutting down schools, and closing markets (Figure 3). There is a logic to these measures: if the virus spreads too quickly it could have enormous consequences for the lives of millions of vulnerable people whose immune systems are already compromised.

Note: Data as at 23 April 2020. Selected measures, list non-exhaustive.

Source: ACAPS, 2020; OECD 2020a.

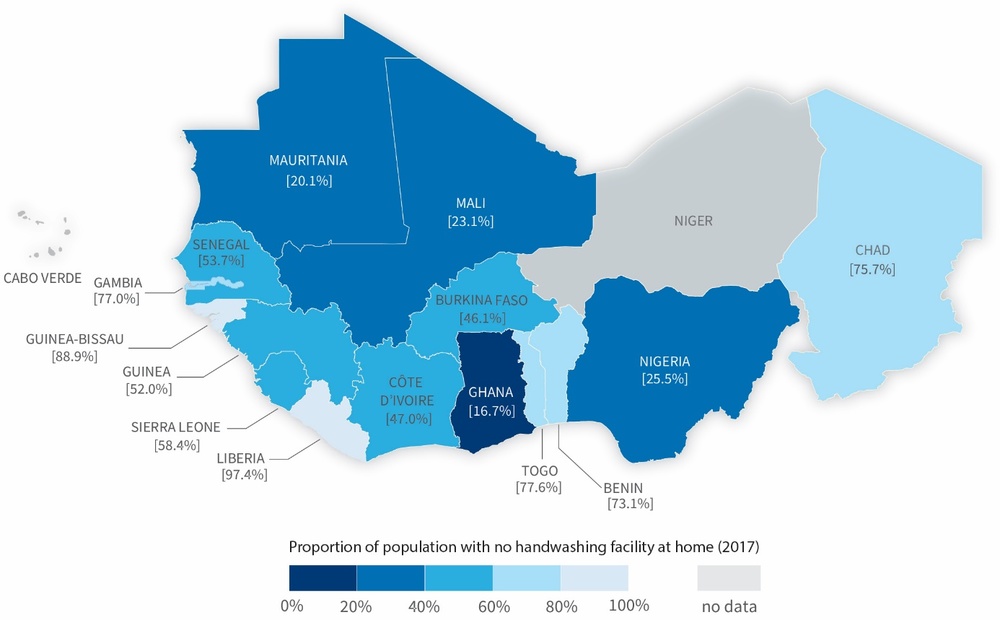

Collateral effects

A number of factors inherent to the region prevent effective implementation of certain measures on the same scale as in Europe. Basic measures such as handwashing are not effective when over one-third of West Africans have no handwashing facility at home (Map 5). Similarly, lockdowns and market closures are difficult in a region where preventing people from going to work could jeopardise their survival. Social distancing is also complex on a continent experiencing the fastest urban growth in the world, where two to three generations often live under the same roof, and where poor sanitary conditions generally prevail. Recognising these challenges, some countries, such as Niger, are raising awareness of preventive measures through communication campaigns in local languages. Others, such as Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia, have taken to the local production of masks in the absence of supplies in pharmacies.

Source: OECD/SWAC 2020c

Some countries have also put in place social safety net provisions, to mitigate the impact of those taken to prevent the spread of the virus. Examples include deferring electricity and water bills for the most vulnerable in Mali, setting up a money transfer programme to those who have seen their incomes diminish in Togo, financially supporting small businesses in Ghana, or suspending rental payments for markets in Burkina Faso. Other countries are now backpedalling on some strict measures initially taken to make them more country-specific, for instance by reducing curfews in Niger or lifting the lockdown in Ghana.

Africa’s financial institutions are also providing assertive responses. The African Development Bank has set up a USD 3 billion “Fight Covid-19” Social Bond (AfDB, 2020a), and a USD 10 billion Covid-19 Response Facility (AfDB, 2020b); the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO, 2020) is supporting credit institutions and companies to help face the outbreak; and the West African Development Bank (BOAD, 2020) has provided XOF 120 billion in concessional loans in the form of XOF 15 billion to each of its eight member states to finance urgent measures in order to deal with the health crisis.

Following the proposal made to the G20 to provide USD 150 billion emergency financing for the continent, African Finance Ministers (UNECA, 2020) co-ordinated a call for an immediate economic stimulus to the tune of USD 100 billion. This includes a waiver of all interest payments on public debt and sovereign bonds estimated at USD 44 billion for 2020, and its possible extension to provide immediate fiscal space and liquidity to governments during the crisis. Ministers also recommend that particular attention be placed on fragile states and vulnerable populations, especially women and children, and those living in informal urban settlements, as well as the need to support the private sector where millions of jobs are at risk (AU, 2020d). In this context, the AU appointed a group of Special Envoys (AU, 2020e), including Nigerian Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala and Ivoirian Tidjane Thiam, to mobilise international support for the continent in its efforts to address the associated economic challenges.

The International Monetary Fund has approved immediate debt relief (IMF, 2020) for 25 poor countries over the next six months. Eleven of those countries are in West Africa: Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Sierra Leone and Togo. Similarly, the Paris Club and the G20 Finance Ministers agreed on a time-bound suspension of debt service payments (G20, 2020) for the poorest countries, from which all 17 countries in the region will benefit.

Impacts

Covid-19 is putting significant strain on countries’ health-care systems, social fabric, and economies around the world. West Africa faces many of the same issues and more. Confinement threatens jobs and livelihoods, particularly in the informal sector, aggravating food and nutrition insecurity, further damaging economic performance and jeopardising the stability of the region. Humanitarian assistance to conflict zones and refugee camps is being disrupted (The New Humanitarian, 2020), highlighting the need for innovative modalities to avoid spreading the virus, as well as the need for humanitarian corridors, in order to reach vulnerable communities. Closure of food-for-work sites, difficulties in delivering fortified food for children, as well as the suspension of many development projects will all have wide-reaching consequences.

Local realities

The informal sector dominates West African economies (OECD/SWAC, 2013). The majority of households are unable to survive without some form of daily trade. A very small minority have bank savings, credit cards, or access to online businesses to allow them to stay indoors for extended periods. There is a persistent need to go out for food, water, or work. Jobs and livelihoods therefore come under threat as measures of confinement, social distancing, transport and trade restrictions, factory closures as well as market closures, force people to stay at home.

Source: Allen, T., P. Heinrigs and I. Heo, 2018

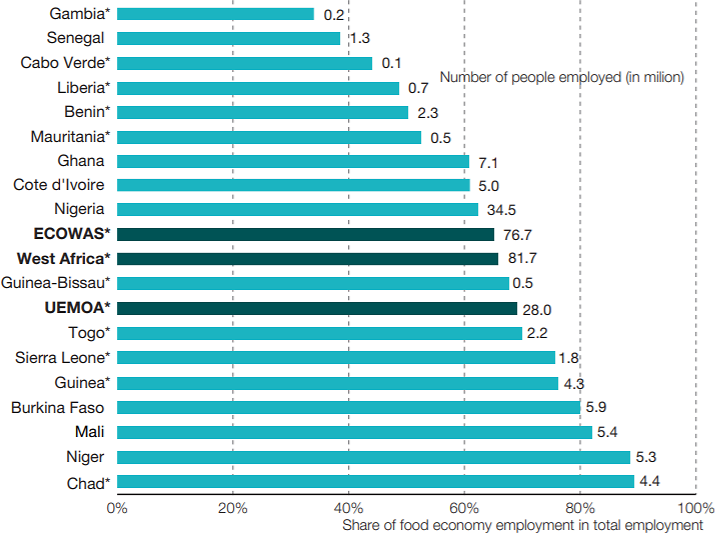

In the food sector alone — the largest economic sector in the region, representing 40% (Ghins and Zougbédé, 2020) of regional gross domestic product (GDP) in 2015 — more than 82 million jobs (Figure 4) will be directly affected by mobility restrictions. This sector comprises agriculture as well as the off-farm segments of food processing, food marketing, and food-away-from-home (including restaurants and street food). Micro, small and medium enterprises, small-scale agricultural producers, herders, traders and similar groups who cannot access their workplace, land, or markets due to mobility restrictions will see their livelihoods collapse as they will be unable to secure the income required to meet their basic needs, particularly in urban and peri-urban areas.

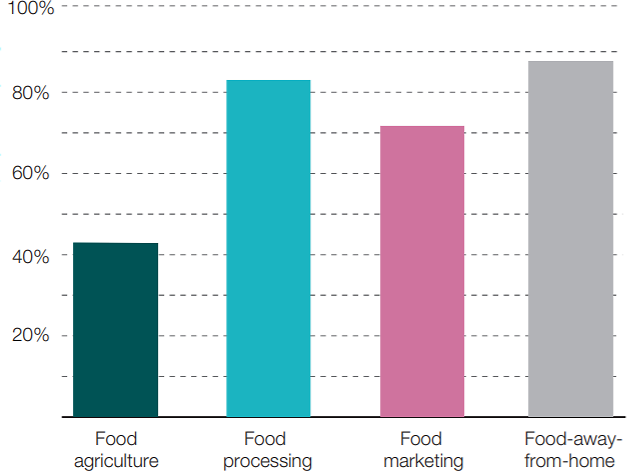

Women will be particularly affected; two-thirds of them work in the food sector, where they account for 51% of the labour force (Allen et. al, 2018). They play an important role at each stage along the food value chain, from production to distribution to nutrition (Figure 5). Yet they often hold the most precarious jobs, such as street vendors, and have no social protection. Moreover, according to WHO, women constitute 70% of the workforce in the health and social sector globally and are on the front lines of the response (WHO, 2019). At the local level, women frequently provide unpaid community-based health care services and manage illnesses within families; they are particularly exposed to potential contamination.

Source: Allen, T., P. Heinrigs and I. Heo 2018

Food supply chains face major disruption, particularly in urban areas. Supply chains rely heavily on human capital, including small holder farmers, herders, seasonal workers, traders, middlemen, wholesalers, processors, and transporters, who work together to bring food from farm gates to consumer plates. Furthermore, border closures, travel bans, and restrictions on movement, can lead to difficulties in buying agricultural inputs, selling products, and accessing markets, leading to severe drops in food production and market disturbances. With 80% of food consumed transiting through markets, these effects are likely to be wide-reaching (AGRA, 2019).

Food prices have seen an upward trend since the beginning of the year, yet markets remain well supplied (RPCA, 2020b). However, price spikes are regularly observed where insecurity disrupts market activity (FEWS NET, 2019). With the upcoming lean season from June to August 2020, as well as persistent insecurity, there is widespread concern that Covid-19 could push prices up even further, reducing the purchasing power of many vulnerable households. With the uncertain outlook on international markets, the price of imported food is expected to be volatile during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Migration movements are a key feature of West African food systems. The availability of agricultural labour force will be disrupted if mobility restrictions are maintained over long periods of time. For instance, regions like the Niayes region in Senegal (horticulture) or northern Ghana rely on regular inflows of agricultural workers. Moreover, for pastoralists, the disruption of traditional transhumance patterns may lead to further conflict between farming and pastoralist communities, particularly in the Nigerian Middle Belt. A lack of agricultural labour and constraints to pastoral activities could provoke a drop in food production.

Food and nutrition security is directly impacted by all of the disruptions to the food economy outlined above. Higher unemployment and reduced purchasing power directly impact people’s access to food. Furthermore, Covid-19 risks overshadowing the existing food crisis facing the region. With the spotlight on stemming the spread of the virus, the lives of millions of food insecure people are at-risk. According to the RPCA (2020b), the combined effect of insecurity and Covid-19 could result in over 50 million additional people falling into a food crisis.

School closures bring additional challenges. Millions of school children will no longer avail of the school meal programmes on which they depend. For poor families, the value of a meal in school is equivalent to about 10% of their monthly income (WFP, 2020). For families with several children in school, that can mean substantial savings. According to the World Food Programme, over 20 million school children in West Africa are missing out on school meals due to Covid-19 related closures (Figure 6). These closures not only exacerbate food insecurity, they also interrupt learning and cause gaps in childcare, putting additional pressure on parents, especially women. The long-term impacts of disrupted schooling and access to nutrition at school for young children will be significant for poor families, limiting their human capital development and future earning potential.

Source: WFP 2020

Global context

The emerging global economic downturn confirmed by the OECD Interim Economic Outlook, is evolving rapidly. Global GDP growth is projected to slow from 2.9% in 2019 to 2.4% in 2020 (OECD, 2020b). Analysis suggests that Africa’s GDP will be hit hard, not least because the African economy is largely centred on trade with the rest of the world (UNCTAD, 2019). Moreover, the continent is largely dependent on exporting raw materials, whose prices have suffered considerably with the global crisis.

In this context, three key challenges lie ahead for West Africa. First, the disruption in global supply chains will rapidly impact economies across the region. A reduction of foreign direct investment is likely as partners redirect capital locally. Remittances may also decline as migrants see their incomes dwindle in host countries. Second, measures that governments are taking to contain the virus such as border closures, travel bans, and restrictions on movement will create significant disruption for people, businesses, and government agencies. As economic activities slow down, effects on unemployment, declining wages, and loss of income are likely to follow, significantly curtailing households’ purchasing power and consumption. Third, the collapse in oil prices will continue to affect exporting countries like Nigeria, with oil exports making up almost 90% of its total export earnings (OPEC, 2018). Similarly, low cotton prices could further decrease, affecting millions of households in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, and Togo that rely on this sector for their income. In Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and other coastal countries, the incomes of coffee, cocoa and cashew nut producers could also fall due to a decrease in global demand.

The implications of these challenges are far-reaching and likely to cause large-scale disruption. A slowdown in overall economic growth is already being felt on the continent, particularly in sectors such as tourism, which accounts for up to 40% of GDP in Cabo Verde and 20% in Gambia (UNCTAD, 2017). With many businesses under significant cost pressures, widespread job losses are likely. In the absence of significant fiscal stimulus packages, the combined impact of these challenges could significantly reduce Africa’s GDP growth in 2020. Some estimate that African economies could experience a loss of between USD 90 billion and USD 200 billion in 2020, depending on the rate of Covid-19 transmission (McKinsey, 2020). In the long-term, African economies will also feel the effects of compromised human capital due to school and university closures, which could disproportionately affect girls, many of whom may not return to school. The ensuing economic effects could be profoundly damaging, particularly for already vulnerable people, potentially jeopardising political and economic stability.

These profound economic effects also jeopardise advances towards the achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. A 1% lower growth in the global economy could translate to between 14 and 22 million more people living in extreme poverty (IFPRI, 2020)2. The UN Economic Commission for Africa has estimated that 48% fewer people will be lifted out of poverty on the continent due to Covid-19.

Policy Implications

Put the informal economy at the heart of public policies

This crisis highlights the social and economic importance of the informal economy, which supports and sustains the vast majority of the population and is a major driver of economic growth. Yet the informal space is not well recognised or valued, leaving the majority of its workers and families outside the realm of public policy. Extending social protection, improving fit-for-purpose infrastructure, raising productivity and wages, listening to the voice of informal economy actors through social dialogue, are just some of the ways to tackle vulnerability and promote the dynamism and creativity of this sector. A shift in mind-set is required, starting by recognising the informal sector as a continuously changing and diverse space, characterised by frequent transitions into and out of informality. Any measures to safeguard employment and livelihoods during and after Covid-19 must take into account the realities on the ground. In the case of West Africa, this reality is informality.

Seize the opportunity to fast-track continental integration

Africa’s economy will be hit hard, due in large part to its heavy dependence on global commodity markets. West Africa will not escape the fallout. The implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) provides an opportunity to achieve economic diversification through the creation of integrated regional value chains, as well as dismantling tariffs and non-tariff barriers.

Despite the fact that Covid-19 is currently disrupting the operationalisation of what could be the world’s largest free trade area, notably preventing the opening of its new secretariat to be based in Accra, Ghana, the AfCFTA is more relevant now than ever before. It has the potential to boost intra-African trade, promote stronger regional integration, and ultimately more resilient economies in the face of a global downturn. With the prospect of AfCFTA serving as an effective shock absorber (Mayaki, 2020) to the crisis, this pandemic could provide an opportunity to further accelerate integration across the continent.

Reaffirm the importance of food systems at all levels

Disruptions triggered by Covid-19 highlight the fragility of food systems at local, national, and regional levels. They also underline the critical need for enhanced regional co-ordination to ensure the smooth functioning of food supply chains directly affecting food and nutrition security. Major efforts are being made in this regard. When ECOWAS Ministers in charge of food and agriculture gathered to discuss the impact of Covid-19 on food and nutrition security (ECOWAS, 2020c), they decided to set up a high-level multidisciplinary regional task force piloted by ECOWAS together with UEMOA and CILSS, to co-ordinate and monitor a regional action plan. They also called for a range of measures including securing the current agro-pastoral campaign, through free movement of agricultural inputs and products and notably across borders; putting in place social protection measures, particularly for vulnerable communities; and mobilising regional food reserves. They also underscored the need to maintain funding allocated to agriculture, despite budgetary pressures from security and health sectors. These recommendations informed the Extraordinary Summit of ECOWAS Heads of State and Government (ECOWAS, 2020d) on the impact of Covid-19. This type of co-ordinated regional response, which reaffirms the vital role that food systems have to play in responding to crises, is critical at this time and for the future.

Looking beyond the current health crisis, a fresh look at evolving food systems and emerging dynamics such as rapid urbanisation is needed to achieve better food and nutrition security outcomes. Concepts like “foodsheds”, which are self-reliant locally or regionally-based food systems, and “city-region food systems” focused on strengthening rural-urban linkages, can help map the structure of food systems, and in turn, inform policy making. While Covid-19 raises tremendous challenges for policy makers, it may also act as a catalyst for raising awareness around the need for a territorial approach to more resilient food systems and sustainable development strategies more broadly.

Promote local initiatives in response strategies

Covid-19 serves as a reminder that health is a global public good, requiring everyone to act together (Africa Renewal, 2020) towards universal recovery (Gurría and Steiner, 2020). West Africa has a role to play in the global response; supporting the development of vaccines and treatments through the contributions of its scientific community, experienced in infectious diseases, and also through its rich biodiversity essential to pharmaceutical production. Furthermore, smart, innovative, and local initiatives are springing up, showcasing just how powerful grassroots movements can be, especially when supported by local authorities. Examples include universities producing hand sanitisers, civil society actors distributing kits for handwashing and leading communication campaigns on preventive measures in local dialects, tailors making masks, as well as the private sector repurposing manufacturing processes to produce PPE or ventilators. Similar to the Ebola outbreak in 2014-16, the Covid-19 pandemic shows that there is no other option but to rely on local actors and promote local initiatives during crisis management.

Prevent competition between crises through increased synergy and co-ordination

With the spotlight now on Covid-19, efforts to counter pre-existing crises run the risk of being ignored. Most funds announced to fight the pandemic do not represent additional resources, but are budget reallocations from other sectors. Ironically, emergency funding may result in reduced resources originally allocated to achieve other developmental goals. In addition to potentially sweeping away long-term gains, neglecting certain sectors could be more harmful than the health crisis itself.

On 31 March 2020, West African Ministers of Agriculture sounded the alarm around the risk of the food crisis falling off the international co-operation’s radar. Similarly, the G5 Sahel Foreign Affairs Ministers called for increased vigilance (G5 Sahel, 2020) regarding the spread of terrorism at a time when governments are focused on combating Covid-19. Against this backdrop, strengthening the peace, humanitarian and development nexus to support the most vulnerable will prove instrumental, especially in the context of multiple and interconnected crises, such as in the Sahel (RPCA, 2019). While local resilience is critical in confronting cross-border terrorism, hunger, drought, pest infestations, and diseases; increased synergy and co-ordinated multilateral action will prove equally important as resources become scarce.

References

ACAPS (2020), #COVID 19 government measures dataset, www.acaps.org/projects/covid19/data.

AfDB (2020a), "African Development Bank launches record breaking $3 billion “Fight COVID-19” Social Bond", African Development Bank, 27 March, https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/african-development-bank-launches-record-breaking-3-billion-fight-covid-19-social-bond-34982.

AfDB (2020b), "African Development Bank Group unveils $10 billion Response Facility to curb COVID-19", 8 April, https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/african-development-bank-group-unveils-10-billion-response-facility-curb-covid-19-35174.

Africa Renewal (2020), "UN SG launches plan to address the potentially devastating socio-economic impact of Covid-19", United Nations, 31 March, https://www.un.org/africarenewal/news/coronavirus/united-nations-secretary-general-launches-plan-address-potentially-devastating-socio-economic.

AGRA (2019), Africa Agriculture Report, The Hidden Middle: A Quiet Revolution in the Private Sector Driving Agricultural Transformation, Issue 7, Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, Nairobi, Kenya.

AU (2020a), "African Union mobilizes continent-wide response to Covid-19 outbreak", African Union, 24 February, https://africacdc.org/news/african-union-mobilizes-continent-wide-response-to-covid-19-outbreak.

AU (2020b), "Africa Joint Continental Strategy for Covid-19 Outbreak", African Union, https://au.int/documents/20200320/africa-joint-continental-strategy-covid-19-outbreak.

AU (2020c), “Communiqué of the Bureau of the Assembly of the African Union Heads of State and Government Teleconference on COVID-19”, African Union, 26 March, 2020, https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20200326/communique-bureau-assembly-african-union-heads-state-and-government.

AU (2020d), Impact of the Coronavirus (Covid 19) on the African Economy, African Union, https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/38326-doc-covid-19_impact_on_african_economy.pdf.

AU (2020e), “African Union Chair President Cyril Ramaphosa Appoints Special Envoys to Mobilise International Economic Support for Continental Fight Against COVID-19”, African Union, 12 April, https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20200412/african-union-chair-president-cyril-ramaphosa-appoints-special-envoys.

AUDA-NEPAD (2020),"COVID-19 & Other Epidemics: Short & Medium Term Response", white paper, https://nepad.org/publication/auda-nepad-response-covid-19-other-epidemics.

BCEAO (2020), « Communiqué de la Banque Centrale des États de l'Afrique de l'Ouest », Central Bank of West African States, https://www.bceao.int/fr/communique-presse/communique-de-la-banque-centrale-des-etats-de-lafrique-de-louest-bceao.

BOAD (2020), Covid-19: In support to emergency measures, BOAD grants XOF120 billion to the WAEMU member", West African Development Bank, 25 March, https://www.boad.org/en/covid-19-in-support-to-emergency-measures-boad-grants-xof120-billion-to-the-waemu-member-countries-and-freezes-debt-repayment-involving-xof76-6-billion.

ECOWAS (2020a), "ECOWAS Statement on Support to Member States against Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)", Economic Community of West African States, 21 March, https://www.ecowas.int/ecowas-provides-support-to-member-states-in-the-fight-against-the-spread-of-coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-pandemic.

ECOWAS (2020b), "ECOWAS communiqué no.2 of 6 April 2020 on the fight against the coronavirus disease", Economic Community of West African States, 6 April, www.ecowas.int/ecowas-communique-n-02-of-6-april-2020-on-the-fight-against-the-coronavirus-disease.

ECOWAS (2020c), "Relevé de synthèse des conclusions et recommandations : Consultation régionale des Ministres en charge de l’agriculture et de l’alimentation de la CEDEAO, de la Mauritanie et du Tchad, sur les impacts du COVID-19 et des nuisibles des cultures sur la sécurité alimentaire et nutritionnelle en Afrique de l’Ouest", Economic Community of West African States, 31 March, www.food-security.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/ECOWAS-VC-31-03-2020-Min-Agric-FR.pdf.

ECOWAS (2020d), "Final communiqué: Extraordinary session of the ECOWAS authority of heads of state and government", Economic Community of West African States, 23 April, https://www.ecowas.int/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/uk2020-04-23-Communique%CC%81_Extraordinary_Summit_Coronavirus_V2-1.pdf.

FEWS NET (2019), Regional Supply and Market Outlook, West Africa, December, https://fews.net/sites/default/files/documents/reports/West%20Africa%20Regional%20Supply%20and%20Markets%20Outlook_Dec2019final.pdf.

G5 Sahel (2020), "Communiqué du Conseil des Ministres des Affaires étrangères du G5 Sahel", https://www.g5sahel.org/images/Docs/Communique_final_V_3.pdf.

G20 (2020), "Communiqué G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Meeting", 15 April, https://g20.org/en/media/Documents/G20_FMCBG_Communiqu%C3%A9_EN%20(2).pdf.

Ghins, L. and K. Zougbédé (2020), “The food economy can create more jobs for West African youth”, OECD Development Matters, 23 August, https://oecd-development-matters.org/2019/08/23/the-food-economy-can-create-more-jobs-for-west-african-youth.

Gurría, A. and A. Steiner (2020), "Six actions à mener pour éviter la plus grave crise de développement du siècle", Jeune Afrique, 7 April, https://www.jeuneafrique.com/922439/economie/tribune-six-actions-a-mener-pour-eviter-la-plus-grave-crise-de-developpement-du-siecle.

IFPRI (2020), "How much will global poverty increase because of Covid-19?", International Food Policy Research Institute, 20 March, https://www.ifpri.org/blog/how-much-will-global-poverty-increase-because-covid-19.

IMF (2020), “IMF Executive Board Approves Immediate Debt Relief for 25 Countries”, International Monetary Fund, 13 April, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/04/13/pr20151-imf-executive-board-approves-immediate-debt-relief-for-25-countries.

IRC (2020), “5 crisis zones threatened by a coronavirus ‘double emergency’”, International Rescue Committee, 9 April, https://www.rescue.org/article/5-crisis-zones-threatened-coronavirus-double-emergency.

Johns Hopkins University & Medicine (2020), Coronavirus Resource Centre. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

Mayaki, I. (2020), "How Africa’s Economies Can Hedge Against COVID-19", Project Syndicate, 27 March, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/africa-trade-integration-hedge-against-covid19-by-ibrahim-assane-mayaki-2020-03.

McKinsey (2020), “Tackling Covid-19 in Africa”, April, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/middle-east-and-africa/tackling-covid-19-in-africa.

Moriconi-Ebrard, F., D. Harre and P. Heinrigs (2016), Urbanisation Dynamics in West Africa 1950–2010: Africapolis I, 2015 Update, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252233-en.

OCHA (2020), "Burkina Faso, Mali & Western Niger: Humanitarian snapshot", United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/20200217_bfa_mli_ner_humanitarian_snapshot_en.pdf.

OECD (2020a), Covid-19 Country policy tracker, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/#country-tracker.

OECD (2020b), OECD Economic Outlook: Interim Report March 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7969896b-en.

OECD (2019), Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4dd50c09-en.

OECD/SWAC (2020a), The Geography of Conflict in North and West Africa, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/02181039-en.

OECD/SWAC (2020b), Africa's Urbanisation Dynamics 2020: Africapolis, Mapping a New Urban Geography, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b6bccb81-en.

OECD/SWAC (2020c), "More than one-third of West Africans have no handwashing facility at home", OECD Publishing, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=127_127156-p9kq2uxm1d&title=More-than-one-third-of-West-Africans-have-no-handwashing-facility-at-home.

OECD/SWAC (2019a), "Businesses and Health in Border Cities", West African Papers, No. 22, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6721f08d-en.

OECD/SWAC (2018), Africapolis (database), www.africapolis.org (accessed 16 April 2020).

OECD/SWAC (2013), Settlement, Market and Food Security, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264187443-en.

OPEC (2018), "Nigeria facts and figures", Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/167.htm (accessed 5 April 2020).

RPCA (2020a), Food and Nutrition Crisis 2020, Food Crisis Prevention Network, www.food-security.net/en/topic/food-and-nutrition-crisis-2020.

RPCA (2020b), "Restricted meeting of the RPCA: Summary of conclusions", Food Crisis Prevention Network, 2 April, www.food-security.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/RPCA2020_summary-of-conclusions_EN.pdf.

RPCA (2019), RPCA Policy Brief, Food Crisis Prevention Network, April, www.food-security.net/en/document/rpca-policy-brief-2019.

The New Humanitarian (2020), “Coronavirus and aid: What we’re watching, 23-29 April” https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2020/04/09/coronavirus-humanitarian-aid-response.

UEMOA (2020), "Lutte contre la pandémie du coronavirus (COVID 19) : la Commission de l’UEMOA prend d’importantes dispositions ", West African Economic and Monetary Union, www.uemoa.int/fr/lutte-contre-la-pandemie-du-coronavirus-covid-19-la-commission-de-l-uemoa-prend-d-importantes.

UN (2019), UN World Population Prospects 2019, United Nations, https://population.un.org/wpp.

UNCTAD (2019), Economic Development in Africa Report 2019: Made in Africa – Rules of Origin for Enhanced Intra-African Trade, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/aldcafrica2019_en.pdf.

UNCTAD (2017), "Key statistics of EDAR 2017 "Tourism for transformative and inclusive growth", United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, https://unctad.org/en/Pages/ALDC/Africa/Edar2017KeyStatistics.aspx.

UNECA (2020), "African Finance Ministers call for coordinated COVID-19 response to mitigate adverse impact on economies and society", United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 23 March, https://www.uneca.org/stories/african-finance-ministers-call-coordinated-covid-19-response-mitigate-adverse-impact.

WAHO (2020), “WAHO Providing Financial and Material Support to ECOWAS Member States to fight Covid-19”, West African Health Organisation, https://www.wahooas.org/web-ooas/sites/default/files/actualites/2208/press-release-covid-19-waho-1-april-2020.pdf.

WEF (2020), "Africa cannot afford to lose doctors to COVID-19", World Economic Forum, 9 April, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/africa-cannot-lose-doctors-covid-19.

WFP (2020), “Global Monitoring of School Meals during Covid-19 School Closures, World Food Programme”, https://cdn.wfp.org/2020/school-feeding-map/index.html.

WHO (2020), "African Region COVID-19 Readiness Status", World Health Organisation, www.afro.who.int/fr/node/12206 (accessed 31 March 2020).

WHO (2019), “Gender equity in the health force: Analysis of 104 countries”, Health Workforce Working Paper 1, World Health Organisation, Geneva.

WHO (n.d.), Global Health Observatory, World Health Organisation, http://www9.who.int/gho/en.

WHO/UNICEF/WFP (2014), Interim guideline: Nutritional care of children and adults with Ebola virus disease in treatment centres, World Health Organisation, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/137425/9789241508056_eng.pdf.

World Bank (2020), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed April 2020).

Yabi, G. (2020), "Avec ou sans, pendant et après le Covid-19, priorité aux réformes des systèmes de santé et d’éducation en Afrique de l’Ouest", OECD Development Matters, 6 April, https://oecd-development-matters.org/2020/04/06/avec-ou-sans-pendant-et-apres-le-covid-19-priorite-aux-reformes-des-systemes-de-sante-et-deducation-en-afrique-de-louest.

Contact

Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat: SWAC.Contact@oecd.org