Abstract

The COVID‑19 pandemic is harming health, social and economic well-being worldwide, with women at the centre. First and foremost, women are leading the health response: women make up almost 70% of the health care workforce, exposing them to a greater risk of infection. At the same time, women are also shouldering much of the burden at home, given school and child care facility closures and longstanding gender inequalities in unpaid work. Women also face high risks of job and income loss, and face increased risks of violence, exploitation, abuse or harassment during times of crisis and quarantine.

Policy responses must be immediate, and they must account for women’s concerns. Governments should consider adopting emergency measures to help parents manage work and caring responsibilities, reinforcing and extending income support measures, expanding support for small businesses and the self-employed, and improving measure to help women victims of violence. Fundamentally, all policy responses to the crisis must embed a gender lens and account for women’s unique needs, responsibilities and perspectives

1. Introduction

The COVID‑19 pandemic is creating a profound shock worldwide, with different implications for men and women. Women are serving on the frontlines against COVID‑19, and the impact of the crisis on women is stark. Women face compounding burdens: they are over-represented working in health systems, continue to do the majority of unpaid care work in households, face high risks of economic insecurity (both today and tomorrow), and face increased risks of violence, exploitation, abuse or harassment during times of crisis and quarantine. The pandemic has had and will continue to have a major impact on the health and well-being of many vulnerable groups (OECD, 2020[1]). Women are among those most heavily affected.

From a medical perspective, early evidence suggests that COVID‑19 seems to hit men harder than women. Fatality rates for men who have contracted COVID‑19 are 60-80% higher than for women. However, as COVID‑19 spreads around the world, the impact of the pandemic on women is becoming increasingly severe.

Women are at the forefront of the battle against the pandemic as they make up almost 70% of the health care workforce, exposing them to greater risk of infection, while they are under-represented in leadership and decision making processes in the health care sector. Moreover, due to persistent gender inequalities across many dimensions, women’s jobs, businesses, incomes and wider living standards may be more exposed than men’s to the anticipated widespread economic fallout from the crisis. Among seniors, globally, there are more elderly women living alone on low incomes – putting them at higher risk of economic insecurity.

Around the world, women carry out far more care work than men – up to ten times as much according to the OECD Development Centre’s Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI). The travel restrictions, at-home quarantines, school and day-care centre closures, and the increased risks faced by elderly relatives can be expected to impose additional burdens on women, even when both women and their partners are confined and may be expected to continue working from home. Crucially, lockdown situations exacerbate risks of violence, exploitation, abuse or harassment against women, as has been seen from previous crises and from the early case of China during the COVID crisis. And despite all this, women’s voices are still not well represented in the media. This risks leaving their expertise unheard and their perspectives ignored in the policy response to the crisis.

This policy brief shines a light on some of the key challenges faced by women during the ongoing COVID‑19 pandemic, and proposes early steps that governments can take to mitigate negative consequences for women and for society at large. Many of these policies affect both women and men, but special attention needs to be devoted to reducing rather than exacerbating existing gender inequalities.

To limit current and future income insecurity, governments should consider extending access to unemployment benefits to disadvantaged groups; consider one-off payments to affected workers; financially help insecure workers and families stay in their homes; and ensure that small business owners have adequate financial support to survive the crisis. To help parents manage both work and caring responsibilities, governments should provide childcare options to working parents in essential services, like health care; offer direct financial support to workers who must take leave to care for children (or support employers who offer paid leave for this); and adapt telework and flexible work requirements to enable workers to combine paid and unpaid work. To help women victims of violence – who may face even more violence when trapped at home with their abusers – governments should ensure that service providers work together, share information, and think carefully about how to support victims when their means of communication may be closely monitored by the abuser with whom they live.

More fundamentally, all of these economic and social policy measures must be embedded in broader efforts to mainstream gender in governments’ responses to the crisis. In the short run, it means, wherever possible, applying a gender lens to emergency policy measures. In the longer run, it means governments having in place a well-functioning system of gender mainstreaming, relying on ready access to gender-disaggregated evidence in all sectors and capacities. Governments must ensure that all policy and structural adjustments aimed at recovery go through robust gender and intersectional analysis, so that differential effects on women and men can be assessed – and planned for.

This policy brief aims to provide support to governments and other relevant stakeholders in thinking about the important gendered implications of the pandemic and taking policy action.

2. Women, care responsibilities, and COVID‑19

2.1. Women’s caring responsibilities outside the home

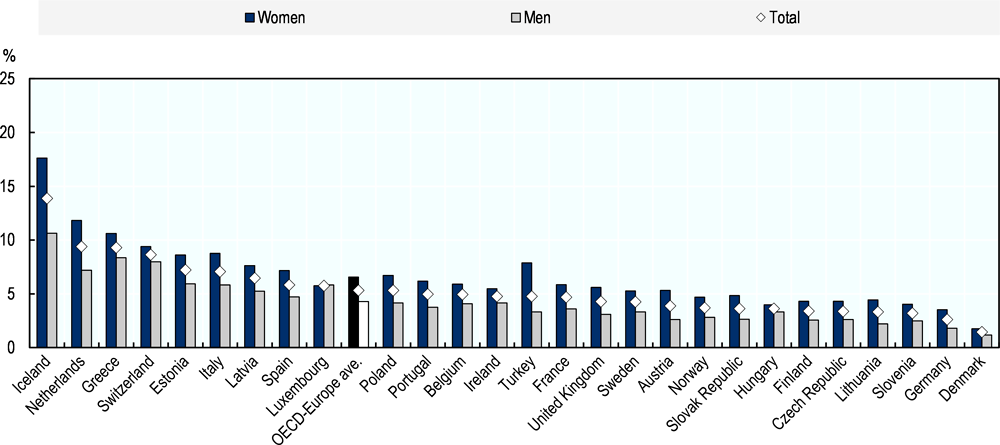

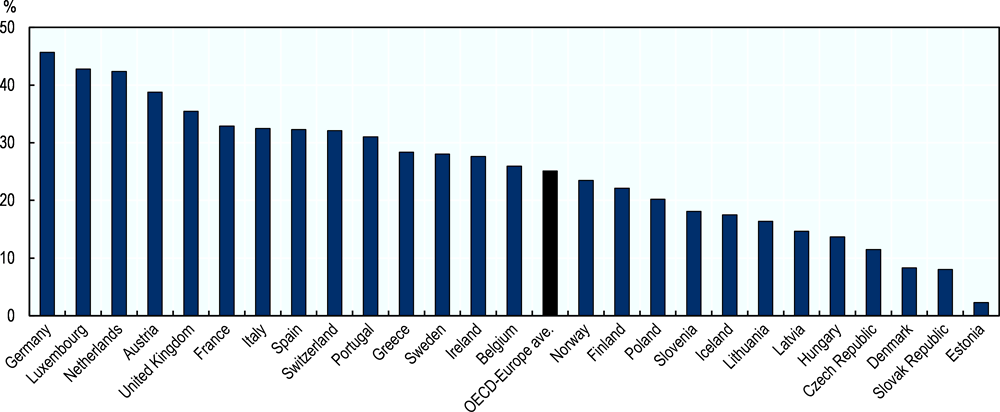

Women are playing a key role in the health care response to the COVID‑19 crisis. Women constitute an estimated two-thirds of the health workforce worldwide, and while globally they are under-represented among physicians, dentists and pharmacists, they make up around 85% of nurses and midwives in the 104 countries for which data are available (Boniol et al., 2019[2]). In OECD countries, almost half of doctors are now women (OECD, 2019[3]). Women also make up the overwhelming majority of the long-term care (LTC) workforce – just over 90%, on average across OECD countries (Figure 1). Despite the fact that the majority of the health care workforce is female, women still make up only a minority of senior or leadership positions in health (Downs et al., 2014[4]; Boniol et al., 2019[2]).

Note: The OECD average is the unweighted averages of the 29 OECD members shown in the chart. EU-Labour Force Survey data are based on ISCO 4 digit and NACE 2 digit classifications. Data for Greece, Italy and Portugal are based on ISCO 3 digit and NACE 2 digit classifications. Data for Greece must be interpreted with caution because of small samples.

Source: OECD (2020[5]), Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Care Workers for the Elderly, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/92c0ef68-en.

All health and social care workers are facing exceptional demands through the crisis, but the strain is likely to be particularly acute for women care workers. Confinement measures and school and childcare facility closures will increase the demand for unpaid work at home (see below), much of which traditionally falls on women. An additional complication is that many care workers are either choosing or are required to isolate when out of work, to minimise the possibility of passing the infection to family members. In these circumstances, it is likely to be difficult, if not impossible, for many women health and social care workers to fulfil both their professional responsibilities and their roles as unpaid workers at home.

Health care workers are facing considerable risks. One particular concern is that the ageing of the physician workforce – over one-third of all doctors in OECD countries are over 55 years of age (OECD, 2019[3]) – exacerbates the high risks that medical staff are already facing. The reports so far on the deaths of doctors (GPs or hospital physicians) due to COVID‑19 in France has tended to be doctors/professional either in their later years of service or those who have responded to a call to return. The health status of the predominantly female long-term care workforce also raises concerns. Given the elevated risks faced by the elderly and those with underlying conditions, long-term care workers have an exceptionally important role to play through the crisis. However, even before the crisis hit, the LTC workforce suffered disproportionately from health problems: on average, more than half (60%) of LTC workers suffer from physical risk factors, and 44% from mental health problems (OECD, 2020[5]). Given the high risks to LTC patients and the associated stress amplified by the crisis, the LTC workforce will be challenged to the full in carrying out their jobs.

Early evidence suggests that COVID‑19 does not affect men and women equally, with men generally at greater risk (Wenham, Smith and Morgan, 2020[6]). A study of clinical characteristics from China found that 58% of the patients were men (Guan et al., 2020[7]). Moreover, fatality rates among men who contract the virus are 65% higher than for the female peers (WHO, 2020[8]). Early explanations for the gender gap include:

Men carry a larger burden of non-communicable diseases (e.g. strokes, most heart diseases, most cancers, and diabetes), which are risk factors for mortality in patients infected by COVID‑19;

Men do worse than women on healthy lifestyles. Men show higher prevalence of risk factors such as smoking, etc.; and,

The immune systems of men and women work in a slightly different way, and women seem to have stronger immune responses even though reasons are not entirely clear and research in the area is relatively young.

While women’s fatality rates seem to be lower than men’s, it is possible that some groups of women may also be at high risk. In addition to the elderly and men and women with underlying health conditions, some authorities, including the United Kingdom, are advising pregnant women to take additional precautions to avoid infection (Public Health England, 2020[9]). This is a precautionary measure, based on more general evidence that, historically, pregnant women have been disproportionately affected by some respiratory illnesses (FIGO, 2020[10]; RCOG, 2020[11]). At the time of writing, health authorities are issuing guidance stating there is no evidence that pregnant women who get the new coronavirus are more at risk of serious complications than the general population (CDC, 2020[12]; FIGO, 2020[10]; WHO, 2020[13]).

2.2. Women’s caring responsibilities at home

Not only do women dominate employment in the care sector, they also provide most unpaid work at home. Across the OECD on average, at just over four hours per day, women systematically spend around 2 hours per day more on unpaid work than men (OECD Gender Data Portal). Gender gaps in unpaid work are largest in Japan and Korea (2.5 hours) and Turkey (4 hours per day), where traditional norms on gender roles prevail. However, even in Denmark, Norway and Sweden – countries that express strong and progressive attitudes towards gender equality – gender gaps in unpaid work still amount to about one hour per day. Gender gaps in unpaid work are often larger in developing and emerging economies (Section 3.4).

Much of women’s unpaid work time is spent on child care. Across OECD countries, women spend, on average, slightly over 35 minutes each day on childcare activities – more than double the amount of time spent on childcare activities by men (15 minutes) (OECD Time Use Database). But many women also provide care for adult relatives, especially parents, even when employed. Available data for European OECD countries show that employed women are 50% more likely than employed men to report that they regularly take care of ill, disabled or elderly adult relatives (Figure 2). These data ignore the efforts of those carers who are not in employment, and show considerable variation; reasons for this may be high part-time employment rates in some countries (e.g. the Netherlands and Switzerland), but also the size of public social service provision (e.g. considerable in Denmark).

COVID‑19 will amplify women’s unpaid work burdens. For example, the widespread closure of schools and childcare facilities will not only increase the amount of time that parents must spend on childcare and child supervision, but also force many to supervise or lead home schooling. Much of this additional burden is likely to fall on women. Similarly, any increases in time spent in the home due to confinement are likely to lead to increased routine housework, including cooking and cleaning. Fulfilling these demands will be difficult for many parents, especially for those that are required to continue working.

Note: Data refer to the share of the employed population who report taking care of ill or disabled or elderly adult relatives (15-year-olds and older), regularly. The relative may live in- or outside the household.

Source: Eurostat Database, based on the European Union Labour Force Survey ad-hoc module 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database.

On the positive side, one potential upshot of widespread school/facility closure and the shift to mass teleworking is that many men will be exposed to the double burden of paid and unpaid work often faced by women. At the very least, many men will witness first-hand the total amount of work their partners put in. But it is also likely that many men will themselves increase their unpaid work through the crisis, boosting their experience and confidence in this area. In cases where their partner is, for example, an essential service work, some men may take on the totality of unpaid work. This has the potential to help trigger a shift in gender norms around unpaid domestic and care work (Alon et al., 2020[14]). While the situations are not identical, evidence from studies on fathers taking parental leave suggests that sharp exposure to domestic and care work can have long-lasting effect on men’s engagement in unpaid work (OECD, 2019[15]).

3. Women, employment, income, and COVID‑19

The spread of COVID‑19 represents not just a public health crisis, but also an economic crisis. The global economy is in greater danger than at any time since the 2008 financial crisis. The spread of the virus has interrupted international supply chains, and is forcing workers to remain at home because they are quarantined, sick or subject to lockdowns. Companies from a variety of industries are finding themselves forced to interrupt and scale down operations. Substantial job losses will likely follow (ILO, 2020[16]).

Evidence from past economic and health crises suggests that shocks on the scale of the COVID‑19 pandemic often impact men and women differently (Rubery and Rafferty, 2013[17]). The 2008 financial crisis, for instance, was characterised by greater job losses in male-dominated sectors (notably construction and manufacturing) and an increase in hours worked by women, especially in the early years (Sahin, Song and Hobijn, 2012[18]; OECD, 2012[19]). During the recovery phase, men’s employment improved more quickly than women’s employment (Périvier, 2014[20]).

However, evidence from infectious disease-driven economic crises often point to sharper effects on women. For example, evidence from the West African Ebola outbreak in 2014-15 suggests that women suffered more through the crisis, in part because their roles as caregivers led to higher infections rates for women (Menéndez et al., 2015[21]; Nkangu, Olatunde and Yaya, 2017[22]), and in part because the types of jobs more often done by women (in this case, as workers in the retail trade, in hospitality and in tourism) were harder hit by the economic contraction (AFDB, 2015[23]). Inadequate public attention to the gendered effects of the Ebola crisis, as well as insufficient attention paid to public policies supporting women during these times, has spurred calls for a more focused look at gender disparities during such health crises (Davies and Bennett, 2016[24]).

3.1. Women employees and the risks to women’s jobs

This crisis is different in nature to previous ones, and given that the scale of the economic impact is still emerging, it is difficult to make firm predictions on whether and to what extent the crisis may disproportionately affect women’s jobs, business and incomes. Still, there are several valid concerns around the impact the crisis may have on women’s economic outcomes.

Despite the remarkable progress made by women over the past half-century or so, women’s position in the labour market remains very different from men’s. On average, employed women work shorter hours than employed men, earn less than employed men (EPIC), and enjoy less seniority than employed men (OECD, 2020[25]; OECD, 2020[26]; ILO, 2018[27]). Women’s labour market attachment tends to be weaker than men’s, especially around parenthood. Women’s job tenure is, on average, shorter than men’s. And men and women continue to work in different sectors of the economy, with women’s employment often concentrated in the public sector and in the care and education sectors (OECD, 2020[25]; ILO, 2018[27]).

In the context of the COVID‑19 crisis, the fear is that gender employment gaps like these leave women more vulnerable than men to job loss; that women’s lesser status in the labour market leaves them more exposed and easier to lay off. These fears are particularly acute in many developing countries and emerging economies, where large numbers of women workers continue to work in “informal employment” – jobs that are often unregistered and that generally lack basic social or legal protection and employment benefits (OECD/ILO, 2019[28]) (see Section 3.4).

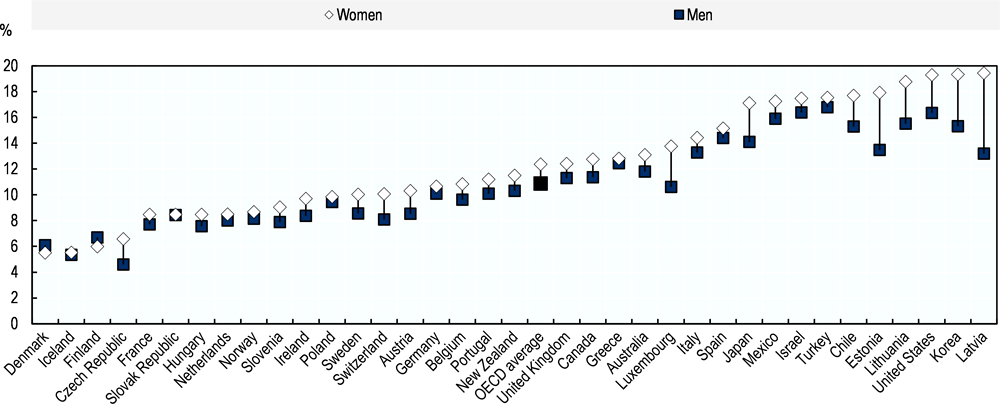

For women in OECD countries, evidence from the past few years – pre-crisis – provides some reassurance on women’s general job security. On average, women’s unemployment rates have remained close to men’s for much of the past decade (OECD, 2020[25]), and data from the OECD Job Quality database suggest gender gaps in unemployment risks are generally only small (Figure 3). Data on self‑perceived job security also suggest that gender gaps in the job security are only small. For example, results from the International Social Survey Programme 2015 show few substantial gender differences in the share of workers believing that their job is not secure, with men, if anything, being more fearful of job loss than women (ISSP, 2018[29]).

Note: Unemployment risk is measured as the monthly unemployment inflow probability times the expected average duration of unemployment spells (in months). Unemployment inflow probability: the ratio of unemployed persons who have been unemployed for less than one month over the number of employed persons one month before. Expected unemployment duration: the inverse of the unemployment outflow probability where the latter is defined as one minus the ratio of unemployed persons who been unemployed for one month or more over the number of unemployed persons one month before.

Source: OECD Job Quality Database, https://www.oecd.org/statistics/job-quality.htm.

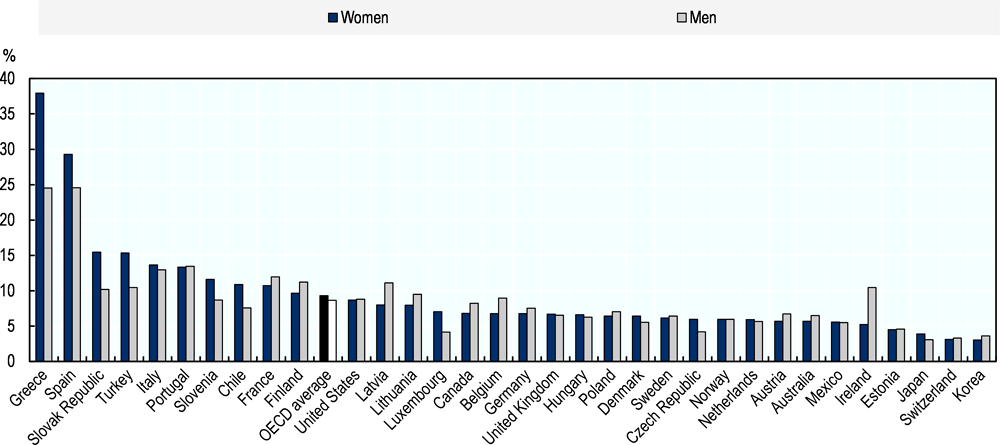

In the very short term, the economic fallout from COVID‑19 is likely to affect some sectors of the economy more than others, with women potentially over-exposed. Most immediately, industries that rely on travel and on physical interaction with customers will inevitably be hit hard. This includes air travel, tourism, retail activities, accommodation services (e.g. hotels), and food and beverage service activities (e.g. cafés, restaurants, and catering). Many of these industries are major employers of women: on average across OECD countries with comparable data, women make up roughly 47% of employment in the air transport industry, 53% in food and beverage services, and 60% in accommodation services (ILO, 2020[30]). In the retail sector, on average, 62% of workers are women, rising to 75% or more in Latvia, Lithuania and Poland (Figure 4).

Some industries further down the supply chain will also be hit hard, quickly. One example is the garment manufacturing industry, which is likely to face disruption from both the supply side (e.g. from confinement measures forcing factory closures) and the demand side (e.g. with the forced closure of retail stores leading to a fall in orders). Women are heavily over-represented in this industry – by some measures, as many of three-quarters of worldwide garment industry workers are women (OECD, 2020[31]). And, given the global distribution of garment supply chains, it is women in developing and emerging economies who will be hit hardest. For instance, in Bangladesh, where the garment industry accounts for more than 80% of annual exports, 85% of garment industry workers are women (Islam Ishty, 2020[32]; OECD, 2020[31]). At the time of writing, early reports suggest demand shocks linked to the COVID-19 crisis have led to the cancellation or suspension of garment exports worth approximately USD 2.67 billion from Bangladesh (FWF, 2020[33]).

The longer-term impact on employment and the distribution of job loss is, at this stage, much harder to predict; a lot depends on the severity and duration of containment measures and the depth and breadth of the economic contraction. As confinement measures expand and supply-chain disruption begins to bite, it is likely that the economic impact will widen across sectors and industries. Indeed, according to early reports, many countries are already seeing a drop in construction and manufacturing activity (ILO, 2020[16]). A broader economic contraction will likely involve job loss in both male- and female-dominated sectors of the economy.

For some women workers, the public sector may offer some protection, at least in the short term. Across the OECD, women make up a disproportionate share of public sector employees: on average, just over 60% of public sector workers are women, rising to roughly 70% in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden (OECD, 2019[34]). While demands on many of these workers will be heavy (see above), public sector jobs should at least offer relative security in the coming months, as governments seek to maintain demand and deal with the most acute health and social care aspects of the crisis.

Note: Data refer to women's share of employment in ISIC Rev 4. category 47 (Retail trade, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles)

Source: OECD calculations based on data from ILO ILOSTAT, https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/.

3.2. Self-employed women and the risks to women-led business

The self-employed and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are at the centre of the current crisis. While the scale of the economic challenge is still unfolding, it is likely that SMEs and the self-employed will be hit hard by supply-chain disruption in affected countries, and will be severely impacted by the longer term economic downturn. SMEs in service sectors such as retailing, tourism and transportation are already suffering the fallout from containment measures, from the collapse in demand, and from the resulting liquidity shortage. The lack of digital facilities and capabilities to allow their workers to do distant work can also place them at a disadvantage in the current context. More generally, many SMEs lack the resources to adapt.

While all SMEs and self-employed workers are likely to be affected by the crisis, differences in the types of businesses operated or business strategies followed mean that men and women entrepreneurs may be impacted differently. Approximately 5% of working-age women in OECD countries are owners of established businesses (i.e. a business more than 42 months old), while 3% are owners of new business (i.e. a business less than 42 months old) and another 5% are actively trying to start a business (OECD/European Union, 2019[35]).

Evidence from the 2008 financial crisis suggests that women-led businesses are not necessarily more vulnerable than men-led businesses. Three-year business survival rates from the 2009 cohort of business start-ups show that survival rates of women-owned businesses were approximately equal to those of men-owned businesses in many countries, including Italy, Finland, the Slovak Republic and Austria. A small gap in business survival rates was observed in Poland (57% vs. 63%), and there were wider gaps in France (63% vs. 70%) and Spain (49% vs. 58%) (OECD, 2012[19]). This resilience can be partially explained by the nature of women-operated businesses, which are more likely to focus on health services, educational services and other personal service sectors that are less susceptible to economic downturns. This is consistent with studies in Italy, for example, which found that women entrepreneurs tended to adopt more conservative business strategies relative to male entrepreneurs during the 2008-09 economic crisis (Buratti, Cesaroni and Sentuti, 2018[36]).

However, the impact of COVID‑19 appears to be having a more rapid impact on more businesses than the 2008-09 downturn as countries implement severe restrictions on commercial and personal activities. There is some evidence that women operate businesses with lower levels of capitalisation and are more reliant on self-financing (OECD/European Union, 2019[35]). This suggests that, despite a tendency to follow more risk averse business strategies, women-operated businesses may be at greater risk of closing during extended periods with substantially reduced, or no, revenue.

3.3. Women’s incomes and the increased risk of female poverty

Regardless of the gendered impact of job and business loss, women are likely to be more vulnerable than men to any crisis-driven loss of income. Across OECD countries, women’s incomes are, on average, lower than men’s (OECD, 2020[37]), and their poverty rates are higher (Figure 5). Women also often hold less wealth than men, for a variety of reasons (Sierminska, Frick and Grabka, 2010[38]; Schneebaum et al., 2018[39]). And because of their greater caring responsibilities (see above), it is often more difficult for women to find alternative employment and income streams (such as piecemeal work) following lay-off.

Note: Data are based on equivalised household disposable income, i.e. income after taxes and transfers adjusted for household size. The poverty threshold is set at 50% of median disposable income in each country. Data for New Zealand refer to 2014, for Iceland, Japan and Switzerland to 2015, for Denmark, Mexico, the Netherlands, Slovak Republic and Turkey to 2016, and for Australia and Israel to 2018. Source: OECD Income Distribution Database, oe.cd/idd.

Single parents, many of whom are women, are likely to be in a particularly vulnerable position. Reliance on a single income means that jobs loss can be critical for single parent families, especially where public income support is weak or slow to react. Evidence from the 2008 financial crisis suggests that, in many countries, children in single-parent families were hit much harder by the recession than children in two‑parent families, not only in terms of income and poverty, but also in terms of access to essential material goods and activities such as adequate nutrition and an adequately warm home (Chzhen, 2014[40]).

Gender inequality also persists in the living situation of seniors and the elderly. Almost one in eight people over 50 years of age say they do not have a person or relative to turn to in time of need (OECD, 2020[41]). In addition, the elderly living alone - especially those with mobility issues - need assistance in getting food, medicine and other essential supplies. Women are likely to be over-represented in this group – among 80‑year olds and over, women are twice as likely as men to live alone (OECD, 2017[42]) – and they face the greatest challenges in getting adequate support without being exposed to infection.

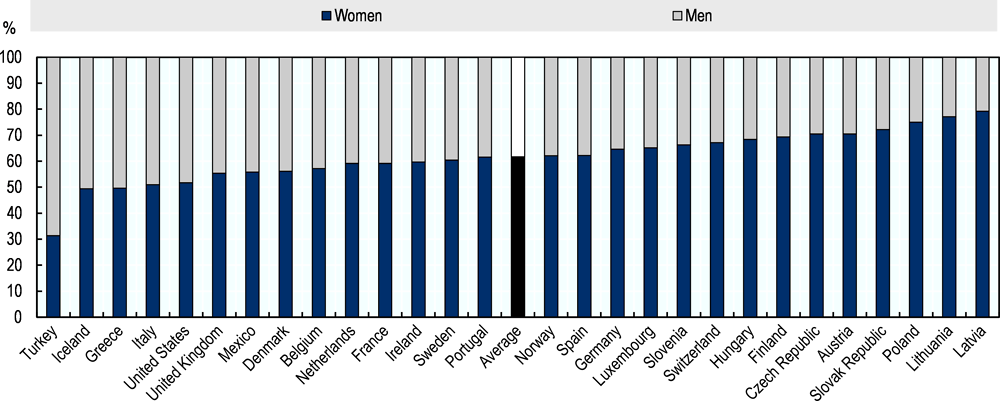

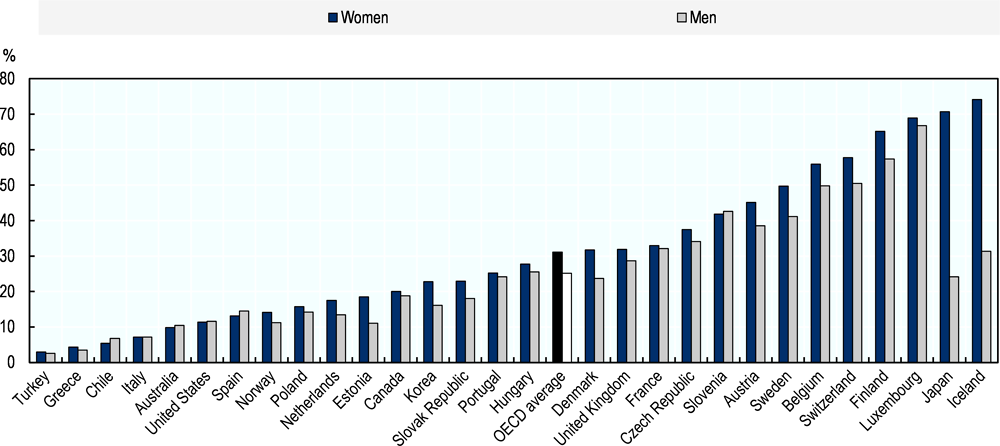

Across almost all OECD countries, older women are also more likely to be poor than older men. In 2016, on average across the OECD, 15.7% of elderly women were in relative income poverty, compared to 10.3% of elderly men (OECD, 2019[43]). This is because, on top of often having worked in lower-paying jobs, older women are more likely to have worked part-time and are more likely to have taken time out of employment for care reasons. As a result, women more often face difficulties in meeting pension contribution requirements, and more often receive only minimum pension payments. The gender pension gap is wide: across European OECD countries, pension payments to women aged 65 and over are 25% lower, on average, than for men. In Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, the gap is over 40% (Figure 6).

Note: The gender pension gap is calculated for persons aged 65 and older using the following formula: 1 – women’s average pension / men’s average pension. It includes persons who obtain old-age benefit (public or private), survival pension or disability benefit. Data for Iceland refer to 2014.

Source: OECD (2019[43]), Pensions at a Glance 2019: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b6d3dcfc-en.

3.4. COVID-19 and women in developing countries

Women’s anticipated vulnerability through the COVID crisis will likely be exacerbated in developing countries.

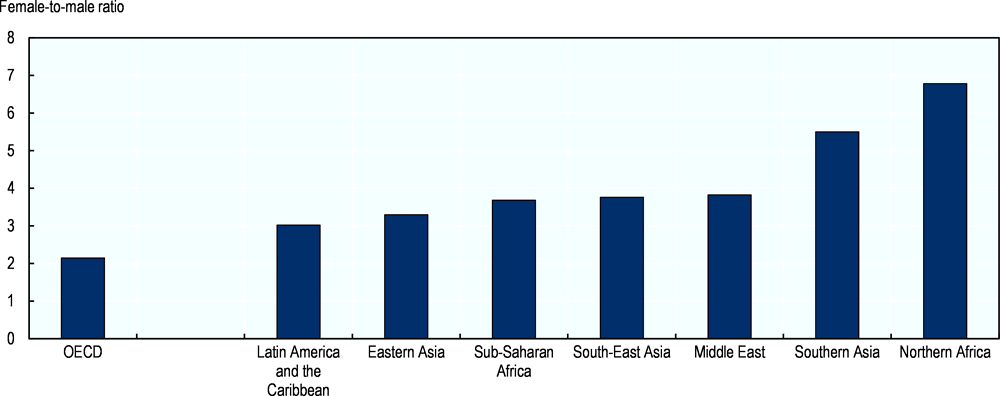

Most immediately, women in developing countries are more likely than many others to be exposed to health risks, particularly where health care infrastructures are inadequate or underdeveloped. Much of this risk stems from women’s disproportionate care responsibilities, as health care workers and as unpaid workers within the home. As discussed above, women not only constitute the majority of health care workers worldwide, but also do most unpaid care work, with the gender gap especially large in developing countries: the female-to-male ratio of unpaid work ranges from three times more in Latin America and the Caribbean to almost seven times more in Northern Africa (Figure 7). In environments with limited health care infrastructure, these care roles, which include caring for the sick and elderly, greatly inflate the chances of infection. Evidence from the West African Ebola outbreak in 2014-15, for instance, suggests that women’s care responsibilities were a major contributor to the disproportionate rate of female infection (Menéndez et al., 2015[21]; Davies and Bennett, 2016[24]; Nkangu, Olatunde and Yaya, 2017[22]).

Beyond infection, the crisis may also have further indirect effects on women’s health in developing countries, particularly for pregnant women. Evidence from past infectious disease crises shows that, when overwhelmed, health systems frequently fail to properly deliver maternal health services, including delivery and pre-natal care (Brolin-Ribacke et al., 2016[44]; Sochas, Channon and Nam, 2017[45]; Wenham, Smith and Morgan, 2020[6]). Confinement measures as well as the risk and fear of contracting the infection in health care facilities may also limit the chances of women attending maternal health services and increase the likelihood of women giving birth unattended (Brolin-Ribacke et al., 2016[44]).

Source: OECD Development Centre (2019[46]), Gender, Institutions and Development Database, https://oe.cd/ds/GIDDB2019.

In addition to health risks, women in developing countries may be more vulnerable than other groups to job and income loss. Compared to women in OECD countries and men everywhere, women in developing countries are more likely to have tenuous ties to labour markets and little access to important social protections like unemployment insurance and contributory health systems (OECD/ILO, 2019[28]). Women in developing countries also hold less wealth than men (Doss et al., 2014[47]), and, among certain age groups, are much more likely to be exposed to extreme poverty than men (Munoz Boudet et al., 2018[48]). Extreme poverty risks are often especially high for girls, young women, and women of parenting age, around age 20‑34 (OECD, 2018[49]).

A major driver of women’s insecurity in developing countries is their likelihood of being informally employed in low-paid jobs. Globally, men are more likely to work in informal employment than women, but in many of the world’s poorest countries it is working women who are most likely to be found in informal employment. This includes most sub-Saharan African, Southern Asian and Latin American countries (OECD/ILO, 2019[28]). Moreover, when women do work informally, they are much more likely than men to find themselves in low-quality informal jobs, especially indigenous women in rural areas (ECLAC, 2019[50]). Indeed, there is a “hierarchy of poverty” among different types of informal workers (OECD/ILO, 2019[28]). Employers and wage workers tend to fare better in job quality and pay, while own‑account, domestic, and family workers usually fare worse. Women tend to work in the second group. In Mexico, for example – an upper middle-income country – 99% of the country’s (largely female) domestic workers are not enrolled in social security (OECD, 2017[51]). These workers are particularly vulnerable as they are not covered by employment-based social protection and labour laws and fall through the cracks of basic occupational safety and health standards. Moreover, many informal activities, especially in urban areas, operate in the streets and may be jeopardised during periods of confinement.

Migrant women represent one particularly vulnerable group. Worldwide, many migrant women work as domestic workers or as informal care workers (ILO, 2016[52]). These women are facing an increasingly precarious work situation, but will also have concerns about their families left behind in their home countries. Lockdown in their countries of employment may also deprive them of income that is crucial to support their families at home. In a similar vein, women and families that depend on remittances from male partners or other relatives abroad are also vulnerable, as confinement measures and job losses in countries of employment will likely reduce the flow of remittances sent home.

More generally, any wider poverty and hardship caused by the COVID-19 crisis may increase the risks of harmful social practices against women and girls in developing countries. All of the concerns outlined above are rooted in, and exacerbated by, deeply embedded discriminatory social norms and practices; indeed, as illustrated by the OECD Development Centre’s SIGI, discriminatory social institutions are particularly strong in many of the world’s poorer countries and communities (OECD, 2019[53]). These discriminatory institutions will likely limit women’s abilities to react and respond to the crisis. As just one example, in the MENA region, there is a strong expectation that, in times of job loss, available job opportunities should go first to men (OECD, 2017[54]). But evidence also suggests a link between poverty and the prevalence of harmful gendered social practices, including child marriage, early school leaving among girls, and property grabbing from widows (OECD, 2018[55]).

4. Women, confinement, and gender-based violence

By most measures, violence against women already represents a global health epidemic. Worldwide, more than one in three women have experienced physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non‑partner sexual violence in their lifetime (oe.cd/vaw2020). This crisis is likely to only worsen as a result of COVID‑19.

Evidence from past crises and natural disasters suggests that confinement measures often lead to increased or first-time violence against women and children. For example, evidence from the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014‑15 shows that women and girls experienced higher rates of sexual violence and abuse during the outbreak than in the preceding years (UNDP, 2015[56]). The cancellation of social events (e.g. football matches) and the closure of social spaces, combined with the closure of schools and the strict enforcement of quarantine measures, often accelerate frustrations, triggering a surge in cases of rape and violence not limited to the household. Furthermore, studies on the consequences of the Ebola crisis in Sierra Leone show that a significant share of girls who had lost relatives to the virus were forced into transactional sex to cover their basic daily needs, including food (Risso-Gill and Finnegan, 2015[57]).

Indeed, early reports from social service providers in China and some OECD countries have shown an increase in domestic violence (DV) against women during the pandemic, as many women and children are trapped at home with their abusers (Du, 2020[58]; Le Monde, 2020[59]). The restrictions put on individuals’ movements prevent survivors of violence from seeking refuge elsewhere, giving abusers enormous control over women and girls during mandatory lockdowns. Women that suffer from intimate partner violence face high barriers when attempting to leave the household to protect themselves or even calling the emergency hotlines in the presence of their abusers, while women and children who are already in shelters or temporary housing are finding it difficult to move on given the risks of infection and lack of places to which to relocate.

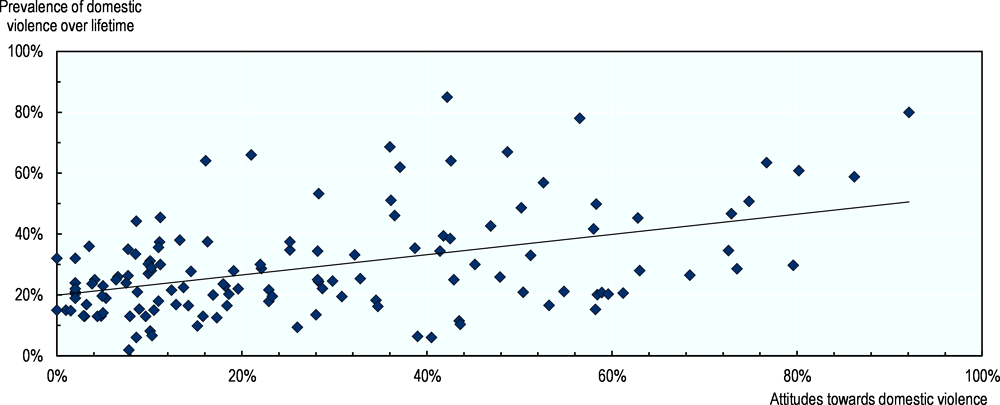

As the social consequences of the outbreak and related confinements start to develop, social norms and patriarchal masculinities may also drive up domestic violence. Evidence from the OECD SIGI 2019 shows that the prevalence of domestic violence is closely intertwined with the social acceptance of domestic violence (Figure 8). Before the COVID‑19 outbreak there were already 27% of women aged 15 to 49 globally who justified the use of domestic violence (OECD, 2019[53]).1 The social consequences of COVID‑19 – e.g. inability to go outside the household, loss of social interactions, all-day presence of children following school closures, tensions inherent to forced cohabitation – are likely to constitute an additional reason for some to justify violence. Domestic violence, often committed by men, is deeply rooted in patriarchal masculinities that lead to power and control of men over women. As the crisis and the uncertainty at the individual and household levels unfold, perpetrators of violence might want to reassert their control and express their frustrations caused by the lockdown through increased episodes of violence.

Note: “Attitudes towards domestic violence” is defined by the percentage of women aged 15-49 years who consider a husband to be justified in hitting or beating his wife for at least one of the specified reasons: if his wife burns the food, argues with him, goes out without telling him, neglects the children or refuses sexual relations. The lifetime prevalence of domestic violence is the percentage of women who suffered from intimate-partner physical and/or sexual violence during their lifetime. Data are available for 134 countries. R² is 0.2113.

Source: OECD Development Centre (2019[46]), Gender, Institutions and Development Database, https://oe.cd/ds/GIDDB2019.

The potential downstream consequences of COVID‑19 – including higher unemployment (for women and men), lost wages, and job insecurity – are particularly dangerous for women in abusive relationships, as economic control is a key tool of abusers. Financial insecurity may force victims to remain with their abusers. It is therefore crucial that governments prioritise intimate partner violence in all parts of their public policy responses to the COVID‑19 pandemic (Section 5.4).

The rapidly-increasing reliance on digital technology during confinement also has implications for gender-based violence, too. Digital tools represent one way for women to escape violence, but also give abusers the possibility to increase their control. On the one hand, women may be able to find help online and to share information that may help them access support services. At the same time, however, forced confinement may make aggressors better able to control their victims and to alienate them from the external world, by controlling their digital tools, such as mobile phones and computers.

An overarching theme across all countries is the often limited ability of survivors to access the justice system (often due to financial concerns). Women are particularly prone to experiencing multiple and compound obstacles in accessing justice. Many economic, structural, institutional, and cultural factors can hinder access. These include cost-related barriers (e.g. direct costs of services), structure-related barriers (e.g. overly technical language in legal documents), social barriers (e.g. judicial stereotypes and bias) and specific barriers faced by at-risk groups (e.g. persons with disabilities, migrant women who cannot easily advocate for themselves). These are likely to be further pronounced during conditions like mobility restrictions and lockdowns created by COVID-19. The crisis may also potentially strain the provision of key government services for survivors, including shelters, medical services, child protection, police and legal aid mechanisms.

5. Policy challenges and policy options

5.1. Support for women, workers and families with caring responsibilities

The large-scale closure of childcare facilities and schools now implemented in an increasing number of OECD countries is likely to cause considerable difficulty for many working parents, and for working mothers in particular, given gender disparities in care responsibilities (see Section 2.2). As has been well-documented (OECD, 2012[19]; OECD, 2017[60]), many women were already working “double shifts” prior to the crisis; the closure of schools and childcare facilities is only compounding the difficulties many women face in balancing work and family. Moreover, a further complication is that grandparents, who are often relied on as informal care providers, are particularly vulnerable and are required to minimise close contact with others, notably with children. Without family networks to rely on, many working parents will have few options other than caring for their children at home.

Offering public childcare options to working parents in essential services, such as health care, public utilities and emergency services.

Providing alternative public care arrangements.

Offering direct financial support to workers who need to take leave.

Giving financial subsidies to employers who provide workers with paid leave.

Promoting flexible working arrangements that account for workers’ family responsibilities.

Teleworking could provide a partial solution for some working parents, but teleworking full office hours can be very difficult if not impossible in practice, notably for families with young children, couples where only one partner can telework, and single parents. Moreover, not all workers have the option of telework. In general, workers in lower-skilled, lower-paid occupations in particular are less likely to be able to work from home (OECD, 2016[61]). In the specific context of COVID‑19, many workers in essential services like public utilities and emergency services may also not be able to opt for teleworking options. And there are also concerns around the impact that mass teleworking might have on women’s productivity. Women, on average, have less access, less exposure and less experience with digital technologies than men (OECD, 2019[62]), potentially putting them at a disadvantage when working remotely. Especially when coupled with their greater care responsibilities, women workers are likely to find it particularly difficult to work at full capacity through any period of sustained telework.

Many working parents may need to request leave from work. In the short term, they might be able to use statutory annual leave, although this often remains at the discretion of the employer. In the United Kingdom, for example, workers must provide their employers with notice before they take leave, and employers can restrict and/or refuse to give leave at certain times. In the United States, at the national level, workers have no statutory entitlement to paid annual leave at all.

Parents’ additional rights to take time off in the case of e.g. school/facility closure are often unclear. Almost all OECD countries provide employees with an entitlement to leave in order to care for ill or injured children or other dependents (OECD, 2020[26]). In some countries, parents have a right to leave in case of unforeseen closures (e.g. Poland and the Slovak Republic) or other “unforeseen emergencies” (e.g. Australia and the United Kingdom), which would likely include sudden school closure. Others (e.g. Austria, Germany) have recently clarified that existing emergency leave entitlements will apply in cases of school or childcare facility closure. However, these rights sometimes extend only as far as unpaid leave, with the decision to continue payment of salaries typically left to the employer. Many parents may be unable to afford taking unpaid leave for any length of time. Moreover, in some countries (e.g. Austria, Germany and the Slovak Republic), these leaves (or the right to payment during leave) are time-limited, while in others, it is unclear how long these rights would continue to apply.

Some countries have begun implementing emergency measures to help working parents in cases of closure of schools or childcare centres. In several countries where childcare facilities and schools have been closed (e.g. Austria, France, Germany and the Netherlands), some facilities remain open, with a skeleton staff, to look after children of essential service workers, notably in health and social care and teaching. In France, for example, childcare facilities for such families can host up to 10 children, and childminders working out of their homes may exceptionally receive up to 6 rather than 3 children. In the Netherlands, the list of essential occupations also includes public transport, food production, transport and distribution, transportation of fuels, waste management, the media, police and the armed forces and essential public authorities.

Countries are also offering financial support to help with the costs of alternative care arrangements. In Italy affected working parents with children below 12 have the possibility to take 15 days of leave, paid at 50% of the salary or unpaid for parents with children above 12. Alternatively they can have a voucher of EUR 600 (EUR 1 000 for medical workers) for alternative care arrangements. This possibility is open to both employees and the self-employed. France has stated that parents impacted by school closure and/or self-isolation will be entitled to paid sick leave if no alternative care or work (e.g. teleworking) arrangements can be found. Portugal announced that parents with children below the age of 12 who cannot work from home and whose children are affected by school closures receive a benefit of two-thirds of their monthly baseline salary, paid in equal shares through employers and social security. Self-employed workers can claim one-third of their standard take-home pay.

A further measure is financial support to employers who provide workers with paid leave. In Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has announced a subsidy to firms that establish their own paid-leave systems for workers affected by school closures. Employers will be compensated for the continued payment of salaries while workers are on leave up to a limit of JPY 8 330 per person per day.

In the public sector, some countries are also expanding flexible working options to help parents juggle work and care. Ireland, for example, has introduced a host of flexible working opportunities for public sector employees, including teleworking, flexible shifts, staggered shifts, longer opening hours and weekend working. An innovative practice involves requiring employees to work in different roles or organisations on a temporary basis to effectively facilitate the flexible work options while allowing delivery of critical services.

5.2. Support for women, workers and families facing job loss

While the COVID‑19 crisis will endanger the jobs and livelihoods of many sections of society, women’s lower average incomes, lower average wealth, greater caring responsibilities and potential over-exposure to job loss means they are more likely than others to find themselves in vulnerable positions (Section 3). Rising economic insecurity is likely to have a particularly damaging effect on women, especially single mothers, as seen through the last recession in 2008. In this regard, policies that help maintain standards of living in cases of income loss are likely to be especially important for women.

Extending access to unemployment benefit to non-standard workers.

Providing easier access to benefits targeted at low-income families, in particular single parents, who are predominantly female.

Considering one-off payments to affected workers.

Reviewing the content and/or timing of reforms restricting access to unemployment benefits that are already scheduled.

Helping economically insecure workers stay in their homes by suspending evictions and deferring mortgage and utility payments.

Unemployment benefits and related income supports are crucial for cushioning income losses. However, not all job losers have access to such support, which is especially problematic if health insurance is tied to employment or benefit receipt. Recent OECD analysis (2019[63]) shows that, prior to recent and forthcoming emergency reforms, access to income support varies substantially both between countries and within countries, with workers in non-standard forms of employment often significantly less well protected than workers in standard forms of employment.

Existing evidence for OECD countries suggests that working women are not generally any less well-covered by income support measures than working men. Indeed, 2015 data from the OECD Job Quality database suggests that, if anything, working women are often covered slightly better by unemployment insurance than men (Figure 9). However, this does not account for “hidden workers” in the informal economy, which is particularly common among workers in developing and emerging economies. These workers often enjoy little or no job-related social protection, and are particularly vulnerable to job loss.

Note: Effective unemployment insurance is defined as the coverage rate of unemployment insurance (UI) times its average net replacement rate among UI recipients plus the coverage rate of unemployment assistance (UA) times its net average replacement rate among UA recipients. The average replacement rates for recipients of UI and UA take account of family benefits, social assistance and housing benefits.

Source: OECD Job Quality Database, https://www.oecd.org/statistics/job-quality.htm.

Even before the COVID‑19 crisis, many countries were exploring how to shore up access to out-of-work benefits in the context of changing working arrangements, including for the self-employed. But it is likely that additional temporary emergency measures will be needed to provide urgent and easy-to-access income support during the COVID‑19 crisis. Several countries have already announced initiatives, which are sometimes modelled on the initial responses to the global financial crisis in 2008/09 (OECD, 2014[64]): for more information on policies to support workers and business through the crisis, please see (OECD, 2020[65]).

One focus has been on easing access to benefits targeted to low-income families (OECD, 2020[65]). The United Kingdom has announced that self-employed workers with low earnings will have more ready access to the main means-tested programme (Universal Credit), and a new hardship fund for local authorities is to support vulnerable people in their area.

Another option is to make one-off payments to workers in urgent need (OECD, 2020[65]). In France, for example, during the global financial crisis, a temporary lump sum payment of EUR 500 was paid directly by the public employment service to workers who lost their jobs but were not eligible to unemployment insurance. Australia has announced that 6.5 million lower-income Australians with benefit entitlements will receive a one-time lump-sum payment of AUD 750. In Italy, some self-employed workers will receive a lump-sum payment for the month of March of EUR 600. In Morocco, employees who lost their job as a result of the crisis will receive a monthly allowance of MAD 2 000 (USD 199) until June 2020.

Governments may also want to review the content or timing of reforms that are already scheduled (OECD, 2020[65]). In France, for instance, the 2019-20 reform of the unemployment insurance tightens minimum contribution eligibility conditions, from 4 to 6 months of work over a 24-month period, and limits replacement rates for workers on fixed-term contracts. Since those workers are not only most at risk of losing their jobs but also less likely to benefit from other forms of protection, such as STW schemes, the reform has been partly postponed for several months. In the United States, access to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, previously “food stamps”) was due to be tightened in April.

Countries are also implementing responses to ensure that households can remain in their homes if they struggle to cover rent, mortgage or utility payments due to a job or wage loss (OECD, 2020[65]). Several (Italy, Spain, the Slovak Republic and the United Kingdom) have introduced temporary deferments of mortgage payments; others temporarily suspended foreclosures (United States) or evictions (France, Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States, and some Canadian regions and municipalities). Through a change in legislation, Greece is temporarily allowing tenants whose employment contract has been suspended because of the COVID‑19 crisis to pay only 60% of their monthly rent on their main residence in March and April. Japan is allowing households affected by COVID‑19 to postpone payments on utility bills if needed. Some countries have introduced measures to support the homeless, who are especially vulnerable to the spread of COVID‑19 and lack the ability to effectively “shelter in place”: France, for instance, has requisitioned hotel rooms to be used by the homeless during the lockdown. In Tunisia, the COVID‑19 emergency plan includes TND 150 million (USD 58 million) in direct cash transfers to highly vulnerable groups, including low-income households, disabled and homeless people.

Providing and reinforcing income support for workers facing job loss is more difficult in developing and emerging economies, in part because of the frequency of informal employment. In the short run, one option is to extend social assistance to all households that may experience a drop in income. Thailand, for example, has introduced a monthly allowance worth THB 500 (USD 150), available for at least three months from April to June 2020, for workers not covered by social insurance as long as they register with one of three state‑owned banks or online. Another option is to provide means-tested cash and/or in-kind transfers to vulnerable groups but not specifically tied to job loss. India, for instance, has introduced a stimulus package that includes cash transfers and the provision of essential goods (e.g. rice and cooking gas) for various vulnerable groups, including poor households, the elderly, and people with disabilities. Notably, the package includes measures specific to women, such as the expansion of collateral-free loans and the introduction of monthly cash transfer worth INR 500 (USD 6.6), targeted specifically at low-income women. In South Africa, a safety net is being developed to support persons in the informal sector, where most businesses will suffer as a result of this shutdown. Morocco also unveiled a set of measures to support workers in the informal sector facing income loss due to the confinement measures in place to contain the spread of the virus. As part of this effort, a livelihood assistance aid will be provided to households, for an amount ranging from MAD 800 (USD 80) for households of up to two members to MAD 1 200 (USD 120) for households of more than four members.

5.3. Support for entrepreneurs and small-business owners

Public policy actions to support the self-employed and entrepreneurs during the initial stages of the COVID‑19 pandemic are focussed on providing financial support to increase the chances of business survival. Surveys among SMEs in several OECD countries confirm that more than 50% of SMEs have already lost significant revenue and risk being out of business in less than three months (OECD, 2020[66]). In this context, a specific challenge that many women face is balancing work with increased responsibilities in the household, including childcare due to school closures. The consequence of the COVID‑19 pandemic could be a significant number of business exits and a substantial loss of jobs since about one-quarter of self-employed women and one-third of self-employed men have employees (OECD/European Union, 2019[35]).

Actively inform firms about how to reduce working hours, provide relief for workers, and manage redundancy payments related to temporary lay-offs and sickness Set up dedicated financial facilities to help small businesses address the short-term consequences of the outbreak – including e.g. temporary tax relief, dedicated loan programmes and direct financial support Ensure that the self-employed can access emergency financial measures, especially those who do not qualify for employment insurance.

Introduce mediation measures concerning procurement and payment delays.

Consider more forward-looking support measures to strengthen business resilience, e.g. training or mentoring programmes to help SMEs assess and manage the financial impact of the crisis, go digital or find new markets.

Ensure an inclusive public-private dialogue so that women business owners can voice their concerns and priorities when public policy reforms are being envisaged.

Governments have been taking action to support the self-employed, although none of the actions to date have focussed specifically on women entrepreneurs. Countries are using different mechanisms to provide financial support. The most common forms of support are a reduction, deferral or cancellation of social contributions for the self-employed (e.g. Belgium, Israel, Portugal), providing access to emergency capital or unemployment benefits (e.g. Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Korea, the Netherlands, Spain, South Africa, United Kingdom). Less common approaches include a moratorium on tax for SMEs and the self-employed (e.g. Italy, Spain, South Africa, Chile, Peru and Argentina) and a temporary suspension of mortgage payment (on principal residence) for the self-employed reporting quarterly loss income greater than 30%, as for example in Italy. For more information on government actions to support SMEs and the self-employed during the COVID‑19 pandemic, please see (OECD, 2020[66]).

5.4. Support for victims of gender-based violence and access to justice

Public policies can help women who are trapped at home with their abusers. The recent high-level OECD conference (oe.cd/vaw2020) on intimate partner violence (IPV) illustrated several policy measures that are especially important now to prevent and address an increase in IPV. These include:

Integrating service delivery across various spheres, including mental and physical health, housing, income support, and access to legal and justice resources, and involving multiple stakeholders – the public sector, the non-profit sector, and employers. This is especially important now as resources are constrained and organisations are moving towards more electronic communication – which presents its own challenges when women are trapped at home with abusers and face domestic obstacles to reporting.

Recommitting to collect better data, and regularly, as countries (even under normal circumstances) face serious challenges in gathering administrative and survey data to assess the incidence of violence. It is particularly important to collect and share during times of crisis so that governments and communities can learn from each other.

Adopting a “whole-of-government” approach to end IPV, so that all public agencies are engaged in this issue in a closely co-ordinated manner. For example, through an adequately resourced national strategy with clearly outlined roles and responsibilities, assessment indicators, and a risk-based approach towards emergency responses in times of crises.

Addressing the bottlenecks in justice pathways that continue to block survivors’ access to justice.

Pushing back on the social acceptance of such violence.

The disruption of health care, support, and police services aggravates the issue, isolating survivors of violence from much-needed resources. The rapid and deadly spread of the pandemic requires countries to divert all their health care capacities into the fight against COVID‑19. Health care systems are overburdened and shift into a “war mind-set”, discontinuing other services considered as “non-essential”. Life-saving care and support to gender-based violence survivors (i.e. clinical management of rape, mental health support, psychosocial support, including hotlines) might be cut off in the process.

To address the specific and intersecting issues of confinement, gender-based violence, and disease transmission, many countries, including Chile, Colombia, Italy, Spain, and the United States, are putting in place special policies aimed at better supporting VAW victims during the COVID‑19 pandemic. For instance, the authorities in Bogotá, Colombia are guaranteeing that victims and survivors of domestic violence will have full access to cash transfers and service supports during the COVID‑19 crisis. Chile’s Ministry of Women and Gender Equality has announced both preventive and containment measures such as continued operations centres for women and shelters, campaigns to encourage reporting of VAW, and online prevention courses. Italy has released public funds to combat VAW, including funds specifically dedicated to COVID‑19 issues, and is promoting an awareness campaign to reach victims. In some parts of Spain, pharmacists are being trained to identify a code word (“mascarilla 19”) as a request for help; upon hearing the phrase, emergency resources are activated and the affected women and minors are supposed to be transferred to public housing resources. Some US states are extending temporary protection from abuse orders and putting measures in place to prevent the spread of COVID‑19 transmission in battered women’s shelters. In New York City and Spain, the government has recognised shelter homes as “essential services” to allow continuation of service, while Canada has announced funding support for shelter homes and assistance centres to facilitate management of the increased demand for their services. In certain cases, family justice centres and assistance centres are adopting hotlines and online communication mechanisms to continue provision of services.

Ensuring that service delivery for victims is integrated across relevant spheres – such as health, social services, education, employment, and justice – and that victims needs and safety are considered when moving towards more electronically-based modes of communication during the COVID‑19 crisis.

Adopting a “whole-of-government” and risk-based approach to end IPV, so that all public agencies are engaged in this issue in a closely co-ordinated manner, and ensuring that timely access to justice remains intact or is strengthened during this period.

Pushing back on social acceptance of domestic violence, in part by drawing attention to how this issue affects women in confinement.

To ensure access to justice while cutting down on operations, courts in Canada have opted for varied approaches (Fasken Institute, 2020[67]). These include online hearings to reduce the number of attendees, identifying a list of “urgent matters” which can continue to be brought to court and, in some cases, hearings over telephone or videoconferencing. In New York City, family courts will be operating remotely through email filings and video or telephone hearings for the most necessary cases.

Around the world, many non-profit organisations are changing services in response to COVID‑19. As one example, the European Family Justice Centre Alliance (ECFJA) – which works to build cross-sectoral co‑operation between professionals working on violence against women and children – has issued a set of guidelines on how professionals might need to adjust practice in light of the crisis (ECFJA, 2020[68]). Some service providers are also adjusting by moving towards the electronic delivery of services, for instance counselling – although this does not eliminate the issue of women being afraid to report, as many abusers control women’s computer and phone usage. Indeed, as some organisations in France now suggest, reporting rates may be repressed as women find it difficult to report while their abuser is home. It is also critical to ensure that frontline services such as hospitals and police do not overlook signs of IPV when overwhelmed by the outbreak, and that public authorities guarantee the operational continuity of support services to victims of intimate-partner violence such domestic violence hotlines, shelters, and associated services.

In a similar vein, organisations providing aid to address the impact of the COVID crisis on women should refer to DAC Recommendation on Ending Sexual Exploitation, Abuse, and Harassment (SEAH) in Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Assistance (OECD, 2019[69]), as it recommends concrete ways to designing mechanisms around a victims/survivors centred-approach, including necessary services and support mechanisms.

5.5. Gender impact assessments, gender budgeting and mainstreaming gender in (emergency) policy responses

The COVID‑19 pandemic has prompted immediate fiscal policy responses by governments to support spending needs in the health sector and mitigate economic effects. In addition to ensuring economic stabilisation and adequate support for men and women, where possible a gender lens should be incorporated in the design and implementation of emergency policy responses. To do so, governments benefit from having in place a well-functioning system of gender budgeting and gender impact assessments, ready access to quality sex-disaggregated data and gender indicators in all sectors, and skills and expertise on how to provide a swift response. However, this is often not the case in many countries, and in its absence, emergency responses to the COVID‑19 outbreak can inadvertently exacerbate existing systemic gender inequalities.

Integrating gender impact assessment processes and tools in emergency management. This integration requires a well-functioning system of gender mainstreaming, ready access to gender-disaggregated evidence in all sectors, and technical skills.

Gender budgeting can help ensure that a gender perspective is applied to measures included in the fiscal stimulus package, and allow governments to understand the collective impact of the package on gender equality objectives.

Ensuring that all policy and structural adjustments to support sustainable recovery go through robust gender and intersectional analysis.

Stepping up measures to increase the role and numbers of women and women’s agencies in decision-making processes, including around prevention and response to COVID‑19.

Canada and Spain are countries with a long-standing tradition of using gender impact assessments, and they quickly mobilised contingency measures for gender equality. Canada, with its formalised gender mainstreaming strategy, “Gender Based Analysis Plus”, offered assistance up to CAD 50 million to women’s shelters and assistance centres to help boost their capacity to assist or prevent cases of domestic violence in response to the COVID‑19 crisis (PM.GC.CA, 2020[70]). Spain’s Ministry of Equality launched the “Contingency Plan against Gender Violence” which included recognition of all assistance services, including legal aid, for victims of violence against women as essential services (La Moncloa, 2020[71]).

Gender budgeting also facilitates the application of a gender perspective to measures included in fiscal stimulus packages similar to how a gender perspective can be applied to spending review exercises. For example, in designing the fiscal response to the current crisis, the Icelandic Government is asking line ministries to describe how potential investments might benefit women and men differently. This allows the Government to take this information into account in the decision making process and better-understand the collective impact of the overall package on gender equality objectives.

Beyond emergency policy responses, all policy and structural adjustments to support sustainable recovery should go through robust gender and intersectional analysis. The potentially disproportionate social and economic impact of the COVID‑19 crisis on women strongly suggests a need to close the implementation gap in gender policies and strengthen the whole-of-government response to gender inequalities.

Well-functioning and resourced central gender equality institutions, coupled with inclusive public leadership, continue to be key pillars of recovery that benefit men and women alike. It is fundamental to increase the role and numbers of women in decision-making processes around prevention and response to COVID‑19 in all countries, and most notably in development and humanitarian settings.

Development aid is likely to make an essential contribution in the fight against COVID‑19 and especially in conflict-affected contexts and also when it comes to programmes on gender equality. OECD statistics show that USD 49.3 billion of bilateral aid on average per year focussed on gender equality and women’s empowerment in 2017-18 (OECD, 2017[72]). This corresponds to 42% of bilateral aid and is higher than ever before. Out of this, USD 4.9 billion was dedicated to gender equality as the principal objective of the programme, corresponding to 4% of bilateral aid. Almost half of bilateral aid in the area of health does not focus on gender equality and women’s empowerment. Sub-sectors in this area with a particularly low focus on gender equality are: infectious disease control, basic health infrastructure, medical research, medical education and training, and sexually transmitted disease (STD) control and HIV/AIDS. There will be an urgent need to consider ways to course correct. Of particular relevance today is the fact that, in 2017, only 25% of aid in the sub-sector of infectious disease control addressed gender equality (OECD, 2020[73]).

Development partners should, as quickly as possible and at the outset of their response efforts, ensure to engage with women’s rights organisations and fund local women’s groups and movements who are working to support women and respond to the crisis. These groups will have an in-depth understanding of the local context, and constraints and opportunities for women and their health. At this stage of the fight against COVID‑19, the OECD GENDERNET is sharing emerging strategies and practices. As a minimum requirement and first step, all external financing needs to “do no harm” to gender equality and women’s empowerment (OECD, 2020[74]).

The spread of COVID‑19 has increased public awareness of the consequences of a lack of resilience and preparedness to deal with a shock. As the OECD highlights in its New Approach to Economic Challenges (NAEC), massive disruptions can and will happen, and it is essential that core systems have the capacity for recovery and the ability to improve the system in order to bouncing forward. For example, climate change and the drivers of biodiversity loss, such as deforestation and wildlife trade, may increase the risk of further pandemics, such as vector-borne or water-borne infections. As women and vulnerable groups are often affected most by such environmental degradation – in particular in developing countries where they are often in charge of providing water, food and fuel for families using surrounding environmental goods – it is important that countries integrate a gender and inclusiveness perspective in their environmental action.

5.6. Implications for women and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The COVID‑19 pandemic poses a severe threat to the achievement of gender-related SDGs. It jeopardises some of the improvements observed since 2015 in several aspects of gender equality and women’s empowerment. The crisis’ economic and social consequences will exacerbate existing inequalities and discrimination against women and girls, especially against the most marginalised and those in extreme poverty. The development of the outbreak might also put a hold to some gender-transformative policies and reforms by diverting resources away from past and current needs of women, whereas the crisis will actually increase and expand them.

Building a strong political commitment to applying a gender perspective to policy responses, allowing arbitration of economic, social and environmental priorities across critical areas strained by the crisis.

Ensuring that basic health care services, in particular related to reproductive and sexual health (including pre- and post-natal health care), are maintained despite the additional pressure imposed on domestic health care capacities by the spread of COVID‑19.

Providing immediate cash transfers and food aid, to mitigate the economic impact of COVID‑19 and to prevent the most vulnerable – primarily women and children – from falling into poverty.

Guaranteeing access to basic services and supporting measures for the most marginalised groups of women, including rural women, female indigenous minorities and refugees.

Ensuring that data collected on the impact of the crisis are systematically sex-disaggregated to measure the effects of the outbreak on SDGs through a gender lens.

Establishing a Gender Observatory and using Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development data and methodologies to map and monitor the gender impact of the crisis and share and identify good policy practices.

It will be challenging to achieve all gender-related SDGs by 2030. All SDGs with gender-related targets and indicators will be affected by the COVID‑19 crisis:

As the economic consequences of the outbreak – e.g. layoffs, income loss, job insecurity – might disproportionately affect women, an increase in women’s poverty levels around the globe is highly likely (“SDG 1 – No Poverty”, “SDG 8 – Decent work and employment growth” and “SDG 10 – Reduced Inequality”).

As evidenced during the Ebola crisis in West Africa in 2014‑15, resources for reproductive and sexual health that are diverted to the emergency response may contribute to a rise in maternal mortality, especially in regions with weak health care capacities (“SDG 3 – Good Health and Well-Being”) (Wenham, Smith and Morgan, 2020[6]). In Sierra Leone, for instance, post-crisis impact studies uncovered that, even under the most conservative scenario, the decrease in utilisation of life-saving health services translated into 3 600 additional maternal, neonatal and stillbirth deaths in the year 2014‑15 (Sochas, Channon and Nam, 2017[45]).

The Ebola crisis also revealed a significant increase in adolescent pregnancies following the closure of schools during the outbreak, which in turn translated into school dropouts for adolescent mothers during the post-crisis period (“SDG 4 – Quality Education”) (Bandiera et al., 2019[75]). Any increase in unpaid and domestic care work falling on women’s and girls’ shoulders – in particular caring for the sick – will also affect girls’ educational prospects.

In countries where social norms imply a preference for boys over girls, the pandemic might magnify these preferences across a wide array of domains. For instance, restricted food resources might lead households where discriminatory social norms are widespread to favour boys over girls, directly affecting “SDG 2 – Zero Hunger”. Similarly, in a context of limited resources, preference might be given to boys over girls in terms of education and health (SDGs 3 and 4).

The pandemic is likely to have severe consequences on the specific achievement of SDG 5. Before the crisis, it was estimated that 2.1 billion girls and women were living in countries that will not achieve gender equality targets by 2030 (Equal Measures 2030, 2020[76]). If the pace of progress slows, both developed and developing countries will require more time to reach gender equality targets. The following SDG targets from SDG 5 will likely be most affected:

SDG 5.1, on legal frameworks: Increasing political commitment had led to new legislation to enhance gender equality and abolish discriminatory laws before the COVID‑19 outbreak, both in OECD and partner countries (OECD, 2019[53]; OECD, 2017[54]). However, in many countries, the health crisis will at best slow progress on new legislation and the implementation of existing legislation, with complete shutdowns possible as the crisis escalates.

SDG 5.2, on violence against women: As discussed above, evidence from previous crises suggests that the COVID‑19 pandemic will likely drive an increase in the prevalence of domestic violence, for several reasons (see Section 4).

SDG 5.3, on harmful practice: Prior the crisis, evidence was pointing to a decline in the practice of child marriage in both South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. However, child-, early- and forced marriage often stem from extreme poverty, and it is possible that any crisis-induced increases in poverty might drive regrowth in these practices in developing countries. Additionally, in low-income countries, the health crisis is likely to have a severe impact government budgets, damaging the resources available for legislative and prosecution activities. Prosecution of perpetrators of female genital mutilation, for instance, might become even more uneven than it was before.