Abstract

Young people are among the most affected by the economic crisis as a result of the COVID‑19 pandemic. This brief provides cross-national information on young people’s concerns, perceived vulnerabilities and policy preferences. The results of the OECD Risks That Matter 2020 survey reveal that two in three 18‑to‑29‑year‑olds are worried about their household’s finances and overall social and economic well-being, and an equal share thinks the government should be doing more to support them. However, only one in four young people are willing to pay additional taxes to finance better provision of employment or income support.

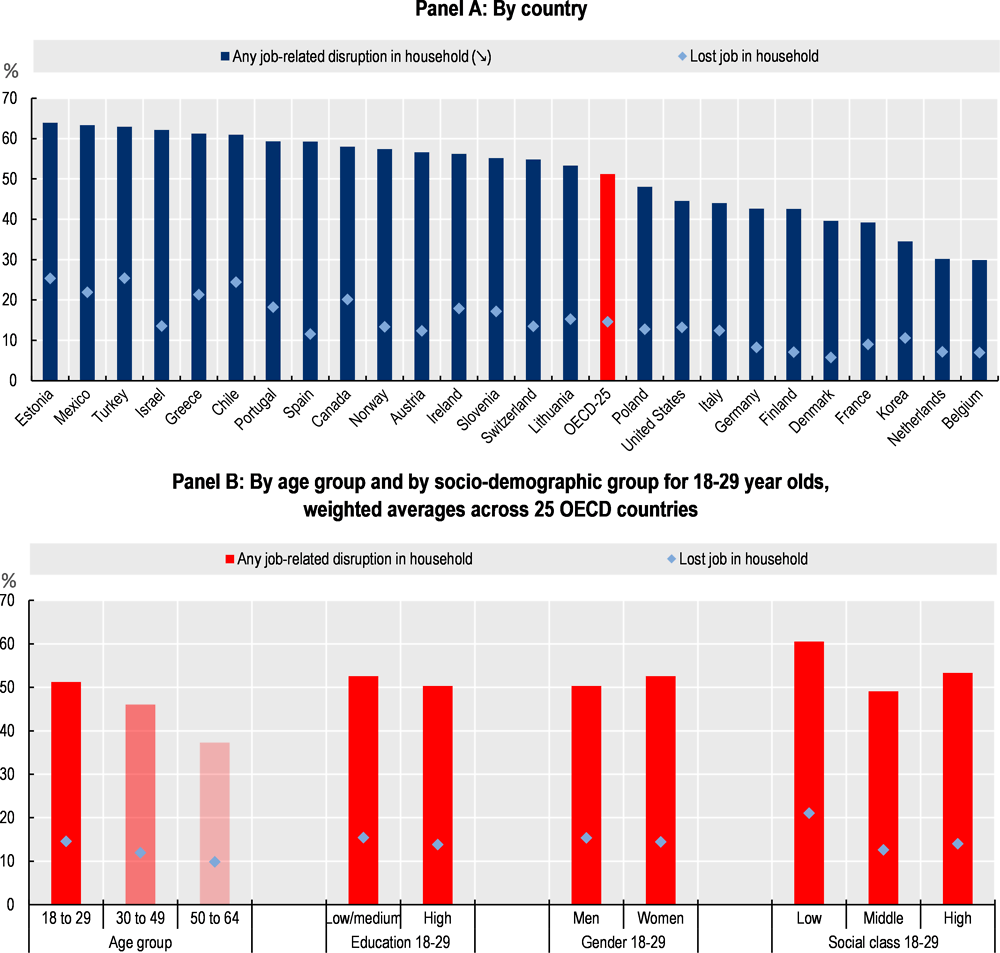

About half of young people’s households have suffered some form of job-related disruption. 51% of the 18‑29 year‑olds who responded to the OECD Risks That Matter 2020 survey say that either they or a household member have experienced job-related disruptions since the start of the COVID‑19 pandemic in the form of a job loss, the use of a job retention scheme, a reduction in working hours, and/or a pay cut. Other age groups report less disruptions in their households: 46% among 30‑49 year‑olds and 37% among 50‑64 year‑olds.

Young people from lower social classes have been more heavily affected. One in five young people who say they belong to low or working classes report outright job losses, compared to only one in eight of those who say they belong to the middle class.

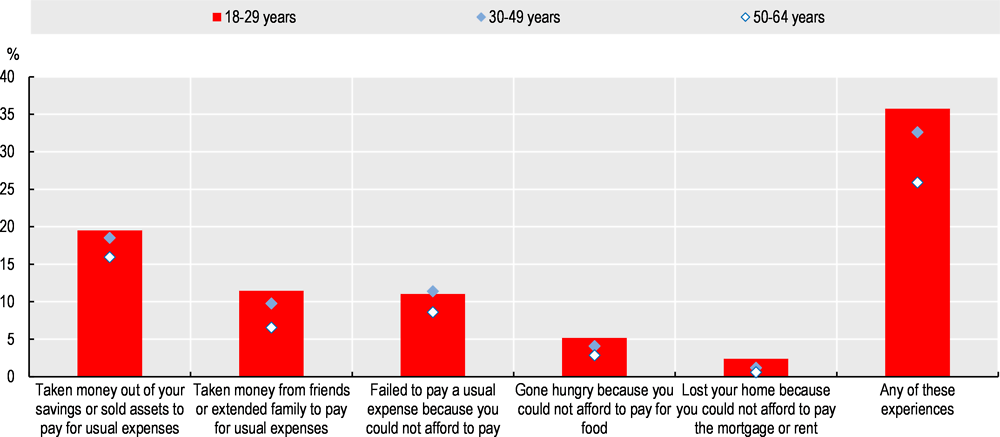

More than one in three young people report financial difficulties since the start of the pandemic. 20% of young people’s households took money out of their savings or sold assets to pay for a usual expense (like rent or utility bill). 11% took money from family or friends to pay for a usual expense and a similar share took on additional debt or used credit. 5% of young people across OECD countries went hungry because they could not afford to pay for food and 2.4% lost their home because they could not afford the mortgage or rent.

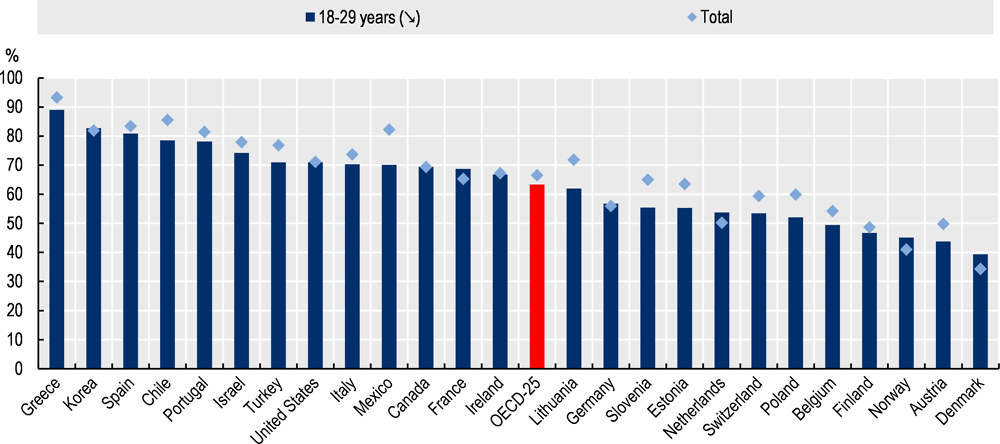

Even in countries where job loss rates and related financial difficulties were relatively low, young people are worried. 63% of young people in OECD countries are concerned about their household’s finances and overall social and economic well-being. While this share is slightly lower than for all age groups together (67%), it is still an alarming majority of young people.

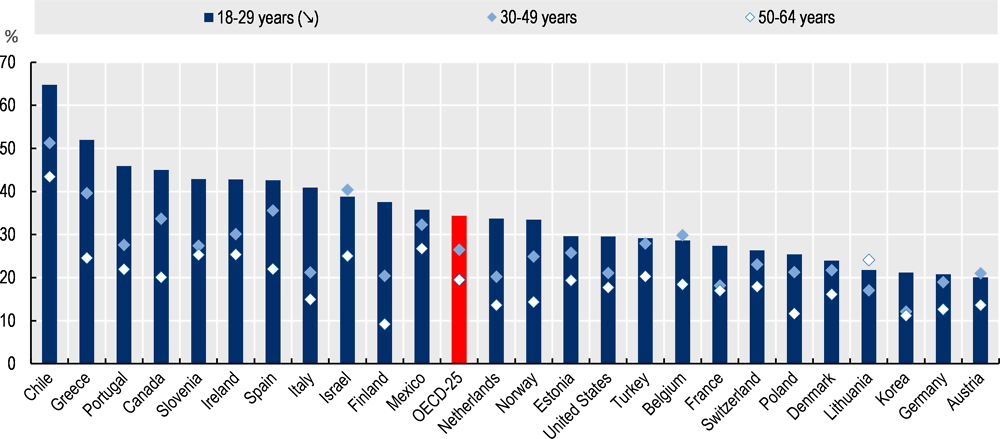

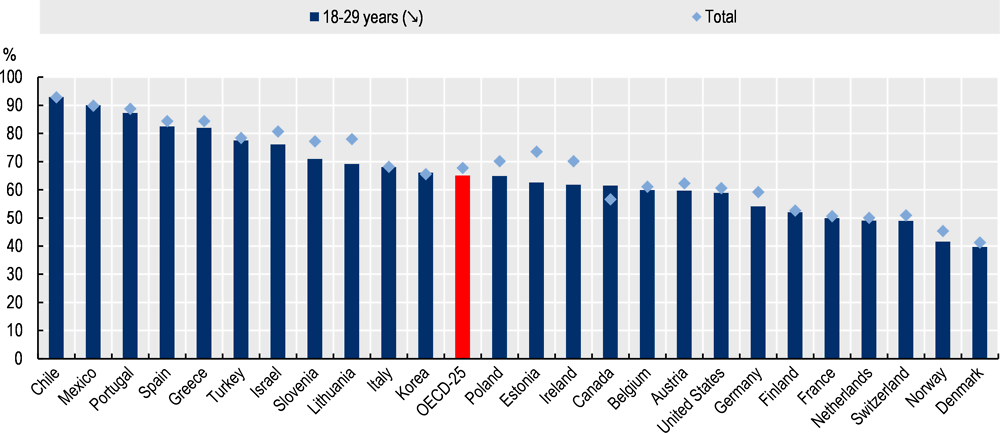

Despite considerable efforts by governments across OECD countries to mitigate the impact of the COVID‑19 crisis, two in three 18‑29 year‑olds think the government should be doing more to ensure their economic and social security and well-being. Although responses differ across countries, more than half of all young respondents believe that the government should be doing more in all but five OECD countries.

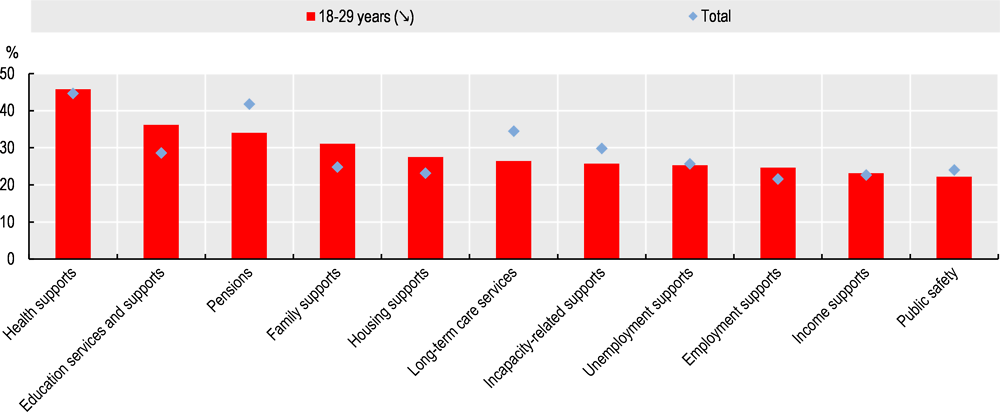

However, they are not necessarily willing to pay additional taxes to finance better provision of employment or income support. Only one in four young people would be willing to pay an additional 2% of their income in taxes and social contributions to benefit from employment or income support. Willingness to pay is higher for gaining better education (36%) and health support (46%).

Four out of ten young people feel that the government does not incorporate their views when designing or reforming public benefits and services. Across all age groups, 49% of the respondents disagree with the statement that the government incorporates the views of people like them when designing or reforming public benefits and services.

Looking beyond standard data sources

The economic crisis as a consequence of the COVID‑19 pandemic has hit young people hard. Youth unemployment rose sharply at the onset of the pandemic, with an impact twice as strong as for the total population, and it remains above pre‑crisis levels in almost all OECD countries. By the end of 2020, the OECD weighted average unemployment rate reached 11.5% for 15‑to‑29‑year‑olds, equal to 19.1 million unemployed young people. Unemployment rose considerably more among young women than among young men at the onset of the pandemic, but the gender gap has closed since. Among young people who managed to keep their employment contract, the number of hours worked has fallen – by 25% year-on-year in the second quarter of 2020 for 15‑24 year‑olds – and the return of hours to pre‑crisis levels has been much slower among young people than among the general working-age population (OECD, 2021[1]). In addition, many young people are challenged by physical-distancing measures, remote learning, a drop in income, complicated situations at home and/or mental health conditions. The crisis is not affecting young people equally, with the ones who were already facing tougher challenges shouldering a larger burden of the crisis.

The impact of the COVID‑19 crisis on young people’s labour market outcomes is analysed in detailed in the OECD Employment Outlook 2021 (OECD, 2021[1]). The OECD Policy Brief What have countries done to support young people in the COVID‑19 crisis? describes the range of measures that countries have put in place for young people in particular (OECD, 2021[2]). This brief complements both reports with findings from the OECD Risks That Matter 2020 Survey. This cross-national survey collects information on people’s concerns, perceived vulnerabilities and policy preferences, and was conducted in September and October 2020 based on a representative sample of 25 000 adults (aged 18‑64) in 25 OECD countries (see Box 1 for more details about the survey).

Young people’s households are heavily affected by COVID‑19 related job disruptions

About half of all young people who responded to OECD Risks That Matter 2020 survey said that either they or a household member have experienced job-related disruptions:1 15% of 18‑29 year‑olds reported outright job loss in their household since the start of the COVID‑19 pandemic, while 51% reported some form of job-related disruptions, including outright job loss but also other disruptions like reduced working hours, pay cut, and/or unpaid leave (Figure 1, Panel A). Young people in all OECD countries have been affected, but the impact varies significantly. In countries like Belgium and the Netherlands, only three out of ten young people reported job disruptions, whereas more than six out of ten young people reported job disruptions in Estonia, Mexico, Turkey, Israel, Greece and Chile.

The difference across countries reflects not only the economic impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic and the stringency of economic lock-downs, but also the use of job retention schemes. These schemes seek to preserve jobs at firms experiencing a temporary decline in business activity by reducing their labour costs and supporting the incomes of workers whose hours are cut back. Although job retention schemes have not been targeted specifically at young workers, they have been used more for young workers than for other age groups, reflecting the large share of young people working in hard-hit industries (in particular accommodation and food services and wholesale and retail trade). In Italy and Switzerland, more than 25% of young workers were on job retention schemes in the second quarter of 2020 (OECD, 2021[1]). In other countries, like Chile and Mexico, where the informal sector is large, many workers are not eligible for formal social protection measures.

The OECD Risks That Matter survey is a cross-national survey examining people’s perceptions of the social and economic risks they face and how well they think their government addresses those risks (OECD, 2021[3]). The survey was conducted for the first time in two waves in 2018 (OECD, 2019[4]). The 2020 survey, conducted in September-October 2020, draws on a representative sample of over 25 000 people aged 18 to 64 years old in the 25 OECD countries that agreed to participate: Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Korea, Lithuania, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey and the United States. Respondents were asked about their social and economic concerns, how well they think the government responds to their needs and expectations, and what policies they would like to see in the future.

The aim of the survey is to understand better what citizens want and need from social policy. Standard data sources, such as administrative records and labour force surveys, provide traditional data on issues such as where and how much people work, how much they earn, their health status, whether or not they are in education, and even, in the case of time‑use surveys, how much they sleep and how they choose to spend their free time. These traditional surveys have proved invaluable for social policy research and have helped shape social programmes for decades. Yet, as highlighted in recent work (Stiglitz, Fitoussi and Durand, 2018[5]), these traditional data sources rarely illuminate people’s concerns, perceived vulnerabilities and preferences, especially with regard to government policy. Existing cross-national surveys in this area (such as certain rounds of the International Social Survey Programme or the European Commission’s Eurobarometer survey) are conducted infrequently and/or only in specific regions. The OECD Risks That Matter survey fills this gap – it complements existing data sources by providing comparable OECD-wide information on people’s opinions about social risks and social policies.

The survey questionnaire was developed in consultation with OECD member countries. The Risks That Matter survey principally covers 1) risk perceptions and the social and economic challenges facing respondents and their households; 2) satisfaction with social protection and government; and 3) desired policies, or preferences for social protection going forward. The 2020 survey questionnaire has added subsections on experiences during COVID‑19, the future of work, and inequality. Most questions are structured as fixed-response, taking the form of either binary-response or scale‑response. The questionnaire is conducted in national languages.

The survey is implemented online using samples recruited via the Internet and over the phone by Respondi Ltd. Respondents are paid a nominal sum (around EUR 1 or EUR 2 per survey). Sampling is conducted through quotas, with sex, age group, education level, income level, and employment status (in the last quarter of 2019) used as the sampling criteria. Survey weights are used to correct for any under- or over-representation based on these five criteria. The target and weighted sample is 1 000 respondents per country. While COVID‑19 infection was not used as a quota target, the OECD Secretariat’s analyses show a strong and statistically significant relationship cross-nationally between self-reported COVID‑19 infection rates in the Risks That Matter survey and epidemiological data from October 2020.

The Risks That Matter survey is overseen by the OECD Employment, Labour and Social Affairs Committee. Core financial support for the survey was provided by OECD member countries’ voluntary contributions and the OECD Secretariat. Researchers at the University of Lausanne and the University of Konstanz also contributed to support subsections of the 2020 survey.

Note: Respondents were asked whether, at any time since the start of the COVID‑19 pandemic, they (or any member of their household) had experienced one or more of a range of specific employment-related events. The options were: lost job, lost self-employed job, or lost own business; laid off temporarily or place on a job retention scheme; had working hours reduced or place on a part-time job retention scheme; had pay reduced by employer or lost income form self-employed job or own business; took leave from work (paid or unpaid); resigned from job. Respondents could select all the options that applied; percentages present the share of respondents who selected at least one. The classification by social class is based on self-reporting. Respondents were asked to which social class they saw themselves and their household belonging to. Respondents could choose as a response option: “lower class”, “working class”, “middle class”, “upper-middle class”, “upper class” or “I would rather not answer”.

Source: OECD Secretariat estimates based on the OECD Risks That Matter 2020 survey, http://oe.cd/RTM.

Other age groups reported lower rates of job disruption. 30‑to‑49‑year‑olds reported outright job loss in their households in 12% of the cases and any job-related disruption in 46% of the cases, while the shares among 50‑64 year‑olds were 10% and 37% respectively (Figure 1, Panel B). Differences across age groups are particularly large when looking at reduced working hours: 17% of young people said that they or one of their household members had working hours reduced or were put on a part-time job retention scheme during COVID‑19, compared to just 14% of 30‑49 year‑olds and only 9% of 50‑64 year‑olds, with a statistically significant gap between the youngest and oldest groups in 15 of the 25 country samples.

Some groups of young people fared worse than others. Especially young people from low social classes report a strong impact of the COVID‑19 crisis: 61% say their household experienced some form of job-related disruption and 21% experienced outright job losses (Figure 1, Panel B). The respective shares for young people from the middle class are 49% and 13%. Low/medium-educated young people and young women overall also report slightly higher shares of job disruptions than their high-educated and male counter parts, though the differences are minimal.

Young people report financial difficulties

As a result of the job-related disruptions, young people and their households have trouble paying their bills. More than one in three young people (36%) report that their household had financial difficulties since the start of the pandemic (Figure 2). This share is higher among 18‑29 year‑old respondents than among 30‑49 year‑olds (33%) and 50‑64 year‑olds (26%), and the difference between the youngest and oldest age groups is statistically significant in 16 out of 25 OECD countries. By gender there is no real difference among young people.

Note: Respondents were asked whether, at any time since the start of the COVID‑19pandemic, they (or their household) had experienced one or more of a range of specific finance‑related events: failed to pay a usual expense (e.g. rent, mortgage, utility bill or credit card bill), took money out of savings or sold assets to pay for usual expense, took money from family or friends to pay for a usual expense, took on additional debt or used credit to pay for usual expenses, asked a charity or non-profit organisation for assistance because they could not afford to pay, went hungry because they could not afford to pay for food, lost their home because they could not afford the mortgage or rent, or declared bankruptcy or asked a credit provider for help. Respondents could select all the options that applied; percentages present the share of respondents who selected at least one.

Source: OECD Secretariat estimates based on the OECD Risks That Matter 2020 survey, http://oe.cd/RTM.

About one in five young people’s households took money out of their savings or sold assets to pay for a usual expense, like rent, mortgage, utility bill or credit card bill. One in ten took money from family or friends to pay for a usual expense and a similar share took on additional debt or used credit. About 5% of young people across OECD countries went hungry because they could not afford to pay for food and 2.4% lost their home because they could not afford the mortgage or rent. For each of these indicators, young people report higher shares for their households than the other two age groups (with the exception of ‘failing to pay a usual expense’ where 30‑49 year‑olds report a similar share as 18‑29 year‑olds).

Considerable differences exist across OECD countries, reflecting to a large extent the impact of job-related disruptions and the social protection measures in place. Financial difficulties among young people’s households were least frequently reported in Austria, France, Germany and the Netherlands (less than 20%) and most often in Chile, Mexico, Slovenia and Turkey (more than 50%).

The COVID‑19 crisis weighs on young people’s minds

Even in countries where job loss rates and related financial difficulties were relatively low, young people worry about financial security. Nearly two in three young people (63%) on average across OECD countries are concerned about their household’s finances and overall social and economic well-being (Figure 3). While this share is slightly lower than for all age groups together (67%), it is still a sizeable share. Young people are particularly concerned about their ability to pay the bills and losing their job, both in the short term and beyond the next decade, with higher shares of young people reporting such worries than the total population for both risks. Despite the ongoing pandemic and related economic crisis, there are more young people who worry about the longer term risks than there are young people who worry about risks in the coming two years. For instance, 53% of young people report that they are concerned about not being able to find/maintain adequate housing in the next year or two, whereas 61% report that they are concerned about not being able to find/maintain adequate housing beyond the next ten years. Not being financially secure in old age seems to particularly weigh on young people’s minds, with 70% of all 18‑29 year‑olds reporting in the Risks That Matter survey that they are somewhat concerned or very concerned about this issue.

Young women (66%) are on average more concerned about their household finance and well-being than young men (60%). There is also strong variation across countries, with the share of those who worry about financial health ranging from 39% in Denmark to 89% in Greece. In most OECD countries (18 out of 25), young people are less concerned about their household finances and well-being than the total population. Not surprisingly, three‑quarters of households who lost jobs during the COVID‑19 pandemic are concerned about financial security (OECD, 2021[6]).

The challenges imposed by the COVID‑19 crisis on young people are having an adverse effect on their mental health. Data from Belgium, France and the United States show that the prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression is around 30% to 80% higher among young people than the general population as of March 2021, with increased levels of loneliness as a particular concern for young people (OECD, 2021[7]). While circumstances differ from individual to individual, the deterioration of young people’s mental health can be attributed to a combination of weakening of protective factors – access to exercise, education, routine, social connection and employment – and an increase in risk factors of mental ill-health – financial insecurity, unemployment and fear. Disruptions to education have been a prominent factor, including for older students, whose studies have been more likely to remain online. Beyond contributing to maintain connections, educational institutions also act as a point of access to mental health services, and their closure has increased the risk of mental health issues remaining unidentified or untreated. The difficult labour market conditions facing young people is also placing additional pressures on the school-to-work transition and increasing the risk of unemployment, a significant risk factor for poor mental health.

Note: Respondents were asked how concerned they were about their household’s finances and overall social and economic well-being in the near future, defined as the next year or two. The response options were “not at all concerned”, “not so concerned”, “somewhat concerned” and “very concerned”. Respondents could also choose “can’t choose” as a response option.

Source: OECD Secretariat estimates based on the OECD Risks That Matter 2020 survey, http://oe.cd/RTM.

The Risks That Matter survey asked participants about the impact of the crisis on their mental health and that of their household. Besides the impact on one’s own mental health, the answer also reveals, to some extent, a higher level of awareness among young people of the mental health issues experienced by other household members, and potentially, a lower level of stigma associated with mental health among this age group. Although the phrasing of the question complicates its interpretation, it is interesting to see that young people are more likely to report worsened mental health for themselves and their households than 30‑49 year‑olds in 22 out of the 25 OECD countries (Figure 4). Women are more likely to report worsened mental health than men in all age groups, with the shares among 18‑29 year‑old women and men being 36% and 26% respectively. The gender difference is equally large for other age groups.

Young people would like to see more government action

OECD governments have been, to a varying degree, supporting young people to mitigate the impact of the COVID‑19 crisis. As described in the OECD Policy Brief, What have countries done to support young people in the COVID‑19 crisis?, government responses span across many policy areas, ranging from labour market measures to support young people in finding and keeping jobs; to income support and housing measures to prevent social exclusion; and mental health initiatives to address worsening mental health conditions. (OECD, 2021[2]). Despite these efforts, two in three 18‑29 year‑old participants in the OECD Risks That Matter 2020 survey think the government should be doing more or much more to ensure their economic and social security and well-being (Figure 5). Positive response rates range from 40% in Denmark (where social protection is well developed) to 93% in Chile. Even so, in all but five OECD countries, more than half of all young respondents believe that the government should be doing more.

Note: Respondents were asked “Has the COVID‑19 pandemic and associated crisis affected your physical or mental health, or the physical or mental health of any member of your household, in any of the following ways?” Respondents were asked to select all that apply from the following answer choices: You (or at least one member of your household) have/has contracted the virus; Your (or at least one member of your household’s) physical health has been affected by the pandemic and crisis in another way; Your (or at least one member of your household’s) mental health and well-being has been affected by the pandemic and crisis; No, none of the above; I would rather not answer. With regards to mental health, respondents were advised that “the ways in which your (or your household’s) mental health might have been affected include increased anxiety, depression, loneliness, or any other mental health complications caused by the pandemic and crisis.”

Source: OECD Secretariat estimates based on the OECD Risks That Matter 2020 survey, http://oe.cd/RTM.

Note: Respondents were asked whether they thought the government should be doing less, more, or the same as they are currently doing to ensure their economic and social security. Possible response options were “much less”, “less”, “about the same as now”, “more” and “much more”.

Source: OECD Secretariat estimates based on the OECD Risks That Matter 2020 survey, http://oe.cd/RTM.

Four in ten young survey participants believe that they could not easily access public benefits if they needed them. The most cited reasons are ineligibility for public benefits (60%), difficult application process (57%), and unfair treatment (46%). Across the OECD, four out of ten young people (40%) who participated in the survey also feel that the government does not incorporate the views of people like them when designing or reforming public benefits and services – while only 24% of the young respondents thinks the opposite. The perspective is slightly more positive among young people than across all age groups, where 49% feel the government does not incorporate the views of people like them. Respondents whose household suffered a job loss are slightly more likely than other respondents to say that they do not feel they would have access to good-quality and affordable public services in every area surveyed: family support, education, employment support, housing, health, incapacity-related needs, long-term care for the elderly, and public safety (OECD, 2021[6]).

However, despite their call for more government support, young people are not necessarily willing to pay additional taxes. Only one in four of the survey respondents aged 18‑29 would be willing to pay an additional 2% of their income in taxes and social contributions to benefit from employment or income support (Figure 6). Willingness to pay is higher for better provision of and access to education services and supports (36%) and health supports (46%). Not surprisingly, young people put more weight on education, family and housing support than the total population, and less on pensions and long-term care services.

Note: Respondents were asked how willing they would be to pay an additional 2% of your income in taxes/social contributions to benefit from better provision of and access to a list of 11 supports. Respondents could also choose “none” or “don’t know” as a response option.

Source: OECD Secretariat estimates based on the OECD Risks That Matter 2020 survey, http://oe.cd/RTM.

References

[1] OECD (2021), OECD Employment Outlook 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/doi.org/10.1787/5a700c4b-en.

[6] OECD (2021), Risks that matter 2020: The long reach of COVID-19, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/44932654-en.

[3] OECD (2021), Risks That Matter: Main Findings from the 2020 OECD Risks That Matter Survey, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://oe.cd/RTM.

[7] OECD (2021), Supporting young people’s mental health through the COVID-19 crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/84e143e5-en.

[2] OECD (2021), What have countries done to support young people in the COVID-19 crisis?, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac9f056c-en.

[11] OECD (2019), Investing in Youth: Korea, Investing in Youth, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4bf4a6d2-en.

[4] OECD (2019), Risks that Matter: Main Findings from the 2018 OECD Risks that Matter Survey, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/Risks-That-Matter-2018-Main-Findings.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2021).

[9] OECD (2018), Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work: The OECD Jobs Strategy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264308817-en.

[10] OECD (2014), “The crisis and its aftermath: A stress test for societies and for social policies”, in Society at a Glance 2014: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/soc_glance-2014-5-en.

[8] OECD (2010), OECD Employment Outlook 2010: Moving beyond the Jobs Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2010-en.

[5] Stiglitz, J., J. Fitoussi and M. Durand (2018), Beyond GDP: Measuring What Counts for Economic and Social Performance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264307292-en.

Acknowledgements

This brief was written by Veerle Miranda with statistical expertise from Maxime Ladaique. The underlying data of the OECD Risks That Matter 2020 survey were kindly provided by Valerie Frey, who has been leading this initiative. The brief was prepared in the OECD Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, under the senior leadership of Stefano Scarpetta (Director), Mark Pearson (Deputy Director) and Monika Queisser (Head of Social Policy).

Contact

Stefano SCARPETTA (✉ stefano.scarpetta@oecd.org)

Monika QUEISSER (✉ monika.queisser@oecd.org)

Veerle MIRANDA (✉ veerle.miranda@oecd.org)

Notes / Conventional signs

In figures, OECD refers to unweighted averages of OECD countries for which data are available.

(➘) in the legend relates to the variable for which countries are ranked from left to right in decreasing order.

All figures and data presented in this brief are accessible in Ms-Excel via http://oe.cd/RTM, as are the questionnaires that were used for the survey.

Note

For the sake of brevity in questionnaire design, the question about job loss in the household does not enable us to identify who in the household lost their job – the young person, a parent, or someone else. The phrasing of the question somewhat complicates interpretation, as we cannot see who is driving the results for households with young people. However, given that households pool resources, and that throughout the OECD households with young people often have higher poverty rates than households without young people (OECD, 2019[11]), there are important substantive implications of this increased insecurity experienced by younger respondents.