This first chapter describes the main characteristics of English apprenticeship in comparison with those of other countries. In England, apprenticeships are much shorter than in many countries and many current apprentices are incumbent workers. England is also distinctive in the lack of emphasis on employer-provided training. This chapter describes the current reforms aiming to expand and improve the quality of apprenticeship. It then sets out an assessment of the direction of reform and the challenges that remain, and summarises the suggestions for policy advanced in depth in later chapters of the report.

Apprenticeship in England, United Kingdom

Chapter 1. Assessment and recommendations

Abstract

Introduction: Why apprenticeship matters

Apprenticeship is now experiencing a global revival

After a period of relative neglect in many countries, apprenticeship is now experiencing a revival, in the light of a wide range of evidence demonstrating its effectiveness as a means of transitioning young people into work, and serving the economy. The prevalence of apprenticeship is highly variable (see Figure 1.1). Few countries can match the energy and range of reforms currently being pursued in England, including an ongoing reform of the content of apprenticeship programmes and how they are assessed, a complete restructuring of funding through the introduction of the apprenticeship levy, a target of three million apprenticeship starts by 2020, and new targets for apprenticeships in the public sector. These reforms are designed to address multiple policy challenges, such as the need to encourage employers to invest more in skills, concern to develop more effective education and training pathways for young people who do not go to university, and a move to correct some serious quality weaknesses in apprenticeships as previously delivered.

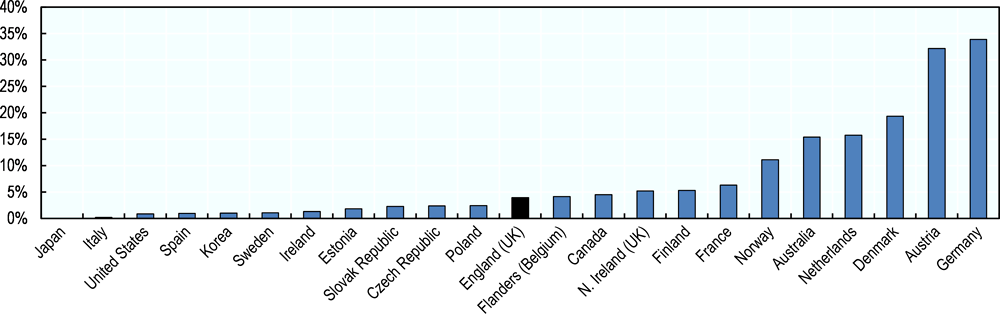

Figure 1.1. There are large differences in the use of apprenticeship across countries

Note: In England, there are no qualifications classified at ICED 4C level. The data are based on self-report and may therefore undercount apprentices in England given evidence that some of them are not aware that they are apprentices. In Japan, Italy, the United States, Spain, Sweden, Korea and Ireland the estimated share of current apprentices is not significantly different from zero. ISCED: International Standard Classification of Education, www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Documents/isced-2011-en.pdf.

Source: OECD (2016), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (Database 2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/publicdataandanalysis/.

This OECD study takes place in the context of these reforms

While there have been several recent reviews of apprenticeship policy in England, the aim of this report is to compare the English apprenticeship system with those of other leading apprenticeship countries, and make policy suggestions on that basis. The work involved study missions to England by the OECD team, and discussions with a wide variety of stakeholders, but also draws extensively on the OECD's range of data, knowledge and experience of the apprenticeship systems of other countries as well as in England.

Subsequent chapters of this report look at different aspects of apprenticeship

This first chapter aims to set the scene. It describes the main characteristics of English apprenticeship in comparison with those of other countries, and describes the current reforms in England. It then sets out an assessment of the direction of reform, and the challenges that remain, and summarises the suggestions for policy advanced in depth in later chapters of the report. Subsequent chapters examine different topics by introducing the challenge (Challenge), advancing policy suggestions (Policy pointer), providing arguments for the proposed policy solutions and discussing how these policy solutions could be implemented in the English context (Analysis). Chapter 2 assesses whether sufficient general education is included within youth apprenticeships and some potential incentives for individuals and employers to engage in youth apprenticeships. Chapter 3 looks at work‑based learning, an issue which is not salient in policy discussion in England, and at a connected risk that apprenticeship might be used as a source of cheap unskilled labour. Chapter 4 compares the apprenticeship levy with levies in other countries, and explores potential incentive effects. Chapter 5 addresses quality in the apprenticeship qualifications system, in terms of the number of apprenticeship qualifications and their articulation with other vocational qualifications, and the role of the market in assessments. Chapter 6 looks at equity, exploring how disadvantaged and under-performing students may be prepared for apprenticeship, and helped to succeed within apprenticeship programmes. Chapter 7 explores policy issues related to different types of apprenticeships in different sectors, including degree apprenticeships, targets in the public sector, and apprenticeships for smaller employers.

The characteristics of English apprenticeship

Apprenticeship numbers have increased dramatically in the last two decades

In England, about half a million apprenticeship starts take place every year, with men and women roughly equally represented. These figures represent dramatic increases from the late 1990s, when the equivalent figure was less than 100 000. Most of the growth has been in older apprentices, with starts for those over 25 more than quadrupling from just under 50 000 in 2009/10 to more than 200 000 in 2015/16. Starts for those under 19 have only increased by about 10% over the same period, to reach 131 000 in 2015/16. Starts for higher-level apprenticeships have increased faster than for Level 2 apprenticeships, but Level 2 apprenticeships still represented nearly 60% of the total in 2015/16 (House of Commons, 2016).

In England, unlike some other countries, relatively few apprentices are in the skilled trades and crafts

The popular image of an apprentice is often someone working in a skilled trade, and this accurately reflects some apprenticeship systems, for example in Ireland (Kis, 2010). But in England nearly three-quarters of apprentice starts in 2015/16 were in three sectors: business administration and law; health, public service and care; and retail and commercial (House of Commons, 2016). This is a recent phenomenon – in the mid-1990s, most of the apprenticeships were in more traditional trade fields such as construction and engineering (Lanning, 2011). Since then, growth in service sector apprenticeships, many of them for older incumbent workers, and often involving some recognition of prior learning and more limited amounts of actual training, have radically changed the picture. Some similar trends have been apparent in Australia (see Box 1.1). An important minority of apprenticeships continue to take a more traditional form. In the engineering and construction sectors apprenticeships often last three years, and are mostly for young people recruited as school leavers as a means of providing skills for the future.

Box 1.1. The changing face of Australian apprenticeships

Apprenticeships and traineeships play a major role in the Australian skills system, with around one-quarter of a million enrolments – although numbers have been falling in the last five years. ‘Traineeships’ are a form of apprenticeship, with a similar mix of work-based learning and off-the-job classroom programmes. Apprenticeships are identified in ‘trade’ areas, such as engineering, automotive, carpentry and the like and are typically three or four years of training, and traineeships in ‘non-trade’ areas, including community and personal service, retail and clerical roles, typically at lower qualification levels and involving often only one or two years of training. Since their introduction in the 1980s, the non-trade traineeships have grown rapidly. Thus, the non-trade sector grew from around one-quarter of the total enrolment (in apprenticeships and traineeships) in the mid-1990s to become the larger part of the enrolled population by 2012, although numbers in the non-trade areas have since fallen sharply. Both apprenticeships and traineeships are referred to below under the title of ‘apprenticeships’.

This sectoral shift has been linked to sharp growth in the proportion of adult apprentices (aged 25 and above). While in 1996 adult apprentices were a small minority, only representing 8% of trade apprenticeships (at a time when most apprenticeships were in the trades) by 2016 adult apprentices were nearly one-third of trade apprenticeships and nearly one-half of non-trade apprenticeships. These adult apprentices are much more likely to be incumbent workers rather than new recruits. Adult apprentices are also more likely to take advantage of opportunities to use the recognition of prior learning to realise an accelerated completion of their apprenticeships – so that around half of the adult apprentices reduced their apprenticeship period from 3-4 years to less than 2 years.

Source: NCVER (2017a), Data Slicer: Apprentices and Trainees December 2016, www.ncver.edu.au/data/data/all-data/data-slicer-apprentices-and-trainees-december-2016; NCVER (2017b),

Historical Time Series of Apprenticeships and Traineeships in Australia from 1963 to 2017, www.ncver.edu.au/data/data/all-data/historical-time-series-tables; Hargreaves, J., J. Stanwick and P. Skujins (2017), The Changing Nature of Apprenticeships: 1996–2016, National Centre for Vocational Education Research, Adelaide, Australia; Knight, B. and T. Karmel (2011), Apprenticeships and Traineeships in Australia, Institute for Public Policy Research, London, United Kingdom, www.ippr.org/files/images/media/files/publication/2011/10/rethinking-apprenticeships_3-2_Oct2011_8028.pdf.

English apprenticeships are much shorter than in many countries

As indicated in Table 1.1, despite a recent requirement that all apprenticeships should be at least one year in length, English apprenticeships are typically much shorter than in many other countries, with an average of less than 18 months, compared with 3-4 years in some other countries (Department for Education, 2016). English apprentices therefore commonly spend less time in total in education and training than those in many other countries. A 3- or 4-year apprenticeship in Denmark, Norway, Austria, Switzerland or Germany will involve a substantial amount of general education, provided off the job – this may be of the order of 400 hours – a point discussed more fully in Chapter 3. This contrasts with the English and maths requirements in an English apprenticeship, which are primarily remedial, and if they apply will involve only around 50 hours of study. Youth apprentices in England therefore receive much less academic preparation than those in the other countries mentioned.

Table 1.1. The duration of apprenticeship programmes and how apprentices spend their time

|

|

Duration of the programme including off-the-job period and work placement with the company |

Time allocation in apprenticeship programmes |

Workplace time spent in productive and non–productive tasks |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Austria |

3-4 years |

66% - work place 20% - off-the-job education and training 14% - leave and sick days |

83% of the time with the company is spent on productive work |

|

Denmark |

3.5-4 years (typically) |

Missing |

Missing |

|

England |

Min 12 months -average around 18 months |

At least 20% in off-the-job education and training, (sometimes in the workplace but outside productive work). |

|

|

Germany |

2-3.5 years |

56% - work place 29% - off-the-job education and training 14% - leave and sick days |

77% of the time with the company is spent on productive work |

|

Netherlands |

2-4 years |

||

|

Norway |

Mostly 4 years (Shorter programmes are available for disadvantaged students) |

(typically, first two years are spent in school and the last two with the company) |

1 year of training 1 year of productive work |

|

Sweden |

3 years |

Apprentices spend as much time in school as in a work place with the company |

Missing |

|

Switzerland |

3-4 years (2-year programmes are available for disadvantaged students) |

59% - work place 27% - off-the-job education and training 14% - leave and sick days |

83% of the time with the company is spent on productive work |

Source: Kuczera M. (2017), “Striking the right balance: Costs and benefits of apprenticeship”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 153, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/995fff01-en.

In England, around half of starting apprentices are incumbent workers

In England around half of apprentices are incumbent workers, a proportion that has been growing over time, with the other half recruited to be apprentices – not all of them starting their training immediately (DfE, 2016). This means that the function of apprenticeship in England is equally divided between skills development for the workforce and initial recruitment. This is closely tied to the age of the apprentices – with nearly 90% of those aged under 19 recruited as apprentices, but only just over 10% of those aged 25 and over. Service sector apprentices are much more likely to be incumbent workers – with more than 60% of starting apprentices being so in retail and health sectors. Conversely in the construction sector, the overwhelming majority – nearly 85% of starting apprentices – are recruited as apprentices (DfE, 2016).

This contrasts with some, but not all other apprenticeship systems

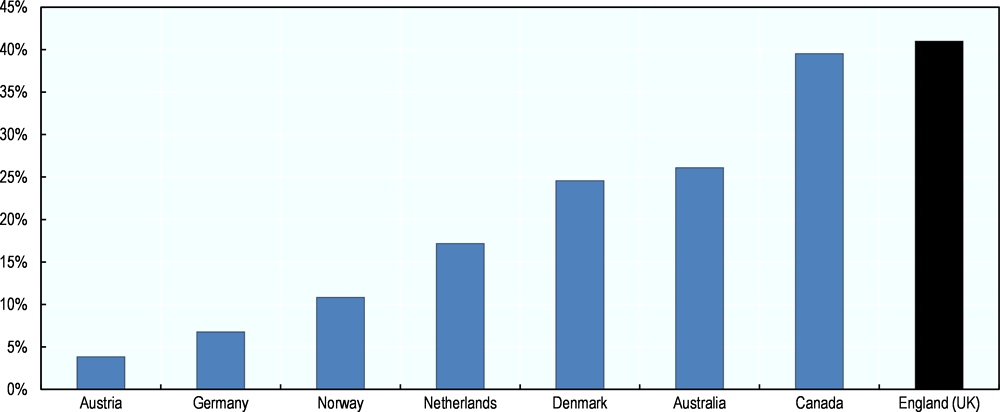

Different countries have very different age mixes in their apprenticeship systems. In Norway, for example, apprenticeship is primarily about transition from school to work and the apprentice population is dominated by young people in upper secondary education. But England’s position is not unique. In the United States and Canada, apprentices are typically in their late 20s (see Figure 1.2), while in Australia, older incumbent workers have become more common among apprenticeship and traineeship starters (see Box 1.1). In Germany in 2014 around 56% of apprentices were under 20, and a further 20% were between 21 and 23 years old, the older apprentices being a mix of those who complete the academic upper secondary Abitur before entering apprenticeship, and others who have often passed through pre-apprenticeship programmes. Conversely in Switzerland the vast majority of apprentices are young – three-quarters were under 20 in 2014/15 (Muehlemann, 2016). Apprentices in England have an ordinary employment contract, rather than the special apprenticeship contract which is found in most apprenticeships in continental Europe, as for example in Germany and Norway. In this respect England is similar to several other countries where apprentices are seen as regular employees (see ILO-World Bank, 2013).

Figure 1.2. Share of 25-year-olds and older among current apprentices (2012, 2014)

Source: Kuczera, M. (2017), “Striking the right balance: Costs and benefits of apprenticeship”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 153, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/995fff01-en; Data for England: BIS (2014), “Apprenticeships Evaluation: Learner Survey”, BIS Research Paper, No. 205, www.gov.uk/government/publications/apprenticeships-evaluation-learner-survey-2014.

The funding and governance is also distinctive

In many apprenticeship systems, little money changes hands other than apprentice wages. Resourcing instead depends on in-kind provision, according to the defined responsibilities of the different parties in the apprenticeship. So, in most apprenticeships in continental Europe, the apprentice works and studies, the employer trains the apprentice on the job, and the vocational school provides the off-the-job training and education. (Adult apprentices sometimes pay tuition fees.) Sometimes apprenticeship systems are supported by government subsidies for participant employers (see Chapter 4). Quality assurance is not linked to financial flows, but to the relative responsibilities of the different parties, so the training provided by the employer is quality assured even though it is not publicly funded.

In England, financial flows drive the apprenticeship system

In England flows of money in different markets drive much of the system. This is because the main regulated element of apprenticeship is off-the-job training, and this training is offered by multiple competing training providers, funded according to various rules, primarily from public money. Historically, awarding bodies competed to market the mini-qualifications that make up apprenticeship frameworks, and these were paid for by the training providers that competed to deliver apprenticeships, drawing down government funding when they did so. While the levy represents a significant reform, flows of money and the incentives they create will continue to drive the system. Quality assurance will continue to follow the flows of money, through approvals of training providers and assessment bodies according to set criteria, and in Ofsted inspections of funded bodies and their activities for which they receive funds. The extensive policy debates in England, which emerge from the driving force of funding, about funding rules and the incentives they create, therefore have limited resonances in continental Europe, but do find more parallels, for example, in Australia, where many private training providers compete to provide the classroom training of apprentices. See Box 1.2 for the definition of the off-the-job training in England.

Box 1.2. Off-the-job training in England

In England, off-the-job training is defined in the apprenticeship funding rules as learning which is undertaken outside of the normal day-to-day working environment and leads towards the achievement of an apprenticeship. This can include training that is delivered at the apprentice’s normal place of work but must not be delivered as part of their normal working duties.

The off-the-job training must be directly relevant to the apprenticeship framework or standard and could include the following:

The teaching of theory (for example: lectures, role playing, simulation exercises, online learning or manufacturer training).

Practical training: shadowing, mentoring, industry visits and attendance at competitions.

Learning support and time spent writing assessments/assignments.

Off-the-job training does not include:

English and maths (up to Level 2) which is funded separately.

Progress reviews or on-programme assessment needed for an apprenticeship framework or standard.

Training which takes place outside the apprentice’s paid working hours.

Source: Education and Skills Funding Agency (2017), Apprenticeship Funding and Performance-Management Rules For Training Providers, www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/646244/17_18_apprenticeships_funding_and_pm_rules_V4.pdf.

England is also distinctive in the lack of emphasis on employer-provided training

Linked to the way in which flows of money drive the system, the focus of policy is funding, and the training which is funded. This is the off-the-job training offered by a registered training provider (recognising that some of the off-the-job training can be provided in the workplace, according to the definition of off-the-job training in England). As discussed in Chapter 3, England is unusual, both relative to other countries, and relative to the historical tradition of apprenticeship, in imposing very few training obligations on employers that take apprentices. This leaves the traditional heart of apprenticeship – training provided in the workplace by an employer – in a marginal position, as it is not subject to regulatory standards. While employers commonly (although certainly not invariably) do train their apprentices, formally and informally, much of this takes place outside the regulated structure of the apprenticeship system.

Policy development: Current and recent reforms

The expansion and improvement of apprenticeship is a major policy target

During recent years, apprenticeship in England has been undergoing extensive reform. Four main pillars of reform can be identified – more substantive and better-quality apprenticeship following the Richard review with the requirement of 20% of the programme duration spent on off-the-job training; reform in the vocational qualification system following the Sainsbury review; growth in apprentice numbers through numerical targets; and funding reform through the introduction of the apprenticeship levy- and non-levy-paying employers funding 10% of the apprenticeship cost (with the exception of SMEs and apprenticeships provided to 16-18 year-olds).

The Richard review recommended both more substantive and better-quality programmes

Prior to the Richard review, apprenticeship programmes had sometimes been completed in weeks or months, and sometimes involved little or no training, with apprenticeship often being used to certify existing skills; nearly half of all apprenticeships occupied less than one year. All apprenticeship programmes now require at least one year, and 20% of working time must be devoted to training. Apprenticeship ‘frameworks’ which build up apprenticeships as an à la carte package of mini-qualifications are gradually being replaced by apprenticeship standards which are intended to be more demanding. Each apprenticeship ‘standard’ sets out the package of skills, knowledge and behaviours required for a target occupation, and that standard is accompanied by an ‘assessment plan’. Standards and assessment plans are developed by groups of (at least 10) employers and are subject to approval by the newly established Institute for Apprenticeships (IfA). This process has many similarities to that adopted by other apprenticeship countries (see Box 1.3). The number of apprentices pursuing standards has been rising. In 2016/17 there were 23 700 starts on new standards as compared to 3 800 the year before (DfE, 2017b). Employers may choose training providers and end-point assessors from a set of bodies approved for these purposes.

A simplified principle of one apprenticeship standard for each occupation has been introduced

In the past, England maintained thousands of vocational qualifications, including those which were built up into apprentice qualifications in apprentice frameworks. Given recommendations in Richard (2012), the Sainsbury review and in a previous OECD review (Musset and Field, 2013), there will be a new approach, based on the principle that there should be one apprenticeship standard for each occupation. Although this represents a radical change in England, it brings England into line with most other major apprenticeship countries, and is very much to be welcomed. Funding bands for training providers vary by level and subject area with higher bands for apprenticeships with higher-cost training, including apprenticeships in STEM. The new Institute for Apprenticeship will have oversight not only of the apprenticeship standards but also the new vocational qualifications, with an emphasis on the quality and coherence of the vocational system, subdivided into 15 pathways.

Numerical targets have been set

An overall target of 3 million apprenticeship starts by 2020 has been set, backed by a new expectation that a minimum of 2.3% of the workforce of larger (250+ employees) public-sector employers should be apprentices (BIS, 2016a) – it is noted that there are no targets for individual employers. The aim is to treble the number of apprenticeships in food, farming and agri-tech, increase the proportion of apprenticeship uptake by black and minority ethnic communities by 20% by 2020, and roll out many more degree apprenticeships (BIS, 2016b).

An apprenticeship levy has been introduced

From 2017, employers will pay 0.5% of their payroll over GBP 3M (thus excluding small employers). Levy funds will be made available to levy-paying and non-levy-paying employers to fund apprenticeship training and the associated end-point assessments (see SFA, 2017). When the apprenticeship levy was announced it was framed in terms of training away from the workplace (e.g. Budget statement, 2015: “This approach will reverse the long-term trend of employer underinvestment in training, which has seen the number of employees who attend a training course away from the workplace fall from 141 000 in 1995 to 18 000 in 2014”, HM Treasury, 2015, pp.60). However, the levy has been implemented more broadly and it can be used to fund any training by an apprentice as long as that apprentice is not working (off-the-job training). The levy is discussed in detail in Chapter 4.

Box 1.3. How vocational education training (VET) programmes are created in Switzerland and Norway

In Switzerland VET programmes are developed by the private sector, i.e. employers and professional organisations. When a professional organisation wishes to introduce a VET programme for a new occupation, it works closely with the other main partners (i.e. the Confederation - federal government, and the cantons). The occupational field and the labour market demand in that occupation need to be confirmed.

The VET programme is launched based on the job profile, the overview of all professional competences and the level of difficulty of the given occupation. The federal State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) examines the proposed draft ‘ordinance’ (legally establishing the programme) and training plan for quality control purposes. Following any necessary adjustments, SERI organises a consultation session with cantonal agencies, federal agencies and other interested parties which may lead to further adjustments in the VET ordinance and training plan before it is approved and launched. The committee responsible for the given occupation will then meet at least every five years to re-examine the VET programme and update it in the light of developments in the industry sector.

Norway has just reformed the process of defining the content of apprenticeship programmes drawing on the positive results of a two-year pilot study.

The reform has reinforced the role of professional councils involving employers and employees representatives (social partners). In the past social partners advised on the content of training provided in the third year of apprenticeship programmes by employers. Now they have a decisive role on the training provided by employers. The government has to take into account social partners’ propositions unless the propositions are against the law or involve an important increase in public spending. Social partners maintain their advisory role regarding the content of the first two years of apprenticeships that are provided in school.

Source: Adapted from (SERI) (2016), Vocational and Professional Education and Training in Switzerland, Facts and Figures 2016, www.eda.admin.ch/content/dam/countries/countries-content/canada/en/Vocational-and-professional-education-and-training-switzerland_E.pdf; Utdanningsdirektoratet (2017), Retningslinjer for samarbeid – SRY, faglige råd og Udir, https://fagligerad.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/retningslinjer-samarbeid-for-sry-fagligerad-udir.pdf.

The policy debate

A sequence of policy reports over 2016 and 2017 have examined current reforms

A first study by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) (Pullen and Clifton, 2016) pointed to the reliance of the economy on low skills as a factor that would not simply be overcome through stronger apprenticeships. Pullen and Dromey (2016) looked at the challenges faced by 16-18 year-olds, and argued that lower level (Level 2) apprenticeships for this age group are weak, since they are too job-specific, often only one year long and do not include sufficient general education. They argue for their replacement by a distinct pre-apprenticeship programme, to include more general education, such as English and maths, with one pre-apprenticeship programme for each of the 15 Sainsbury pathways. In a study for the Institute of Fiscal Studies, Amin-Smith et al., (2017) argue that there is a risk that the target of three million apprentices may be at the expense of quality, and are particularly critical of the public-sector target which they see as arbitrary. A parliamentary select committee report (House of Commons, 2017) argues for more emphasis on outcome measures alongside the target of three million starts and that levy funding should prioritise industry sectors and parts of the country where skills development is most needed. All the reports express concern that the levy may lead to mere rebadging of existing training arrangements to become fundable under the levy. Both Amin-Smith et al., (2017) and the select committee also express concern about a one-size-fits-all approach to the public sector. In a new report on skills in England the OECD (2017) argue, in respect of apprenticeship, that more rigorous standards are needed for the type and quality of on-the-job training, and that more emphasis should be given to helping employers see the business case for apprenticeship.

Assessment: Strengths

Current reforms represent a serious attempt to develop a high-quality apprenticeship system

The apprenticeship reforms in England have many strengths. They champion the historically neglected institution of apprenticeship, address head-on some of its previous weaknesses by requiring or encouraging more substantive, demanding and higher-level programmes and provide an enabling funding framework. Alongside wider reforms in the qualifications system, they replace a dysfunctional proliferation of competing and overlapping qualifications, with a single apprenticeship standard developed with employers for each occupation. They are backed by high-quality analysis, and increasingly rich data sources. Collectively this involves a concerted and serious attempt to develop a high-quality apprenticeship system in England. More specifically:

Apprenticeship is being championed

Policy in England displays an unequivocal commitment to supporting apprenticeship, through reform of the content of apprenticeships following the Richard review, and of the funding system through the levy. Together, these place apprenticeship in a deservedly central place in the education and training system, recognising its proven strengths as a model of vocational learning.

Apprenticeships are more substantive and organised according to new standards

Recent reforms, following the 2012 Richard review, have made a good start in recovering from a position in which most apprenticeships were low level and insubstantive. Apprenticeships now have a minimum length of one year, although average lengths are still half or less of those of other leading apprenticeship countries. The new standards are developed by employers and are consistent with the approach of many other strong apprenticeship countries.

A more transparent apprenticeship qualifications system is in place

Vocational qualifications, including apprenticeship programmes as frameworks, had become exceptionally diverse and fragmented, with large numbers of qualifications of limited labour market value. Following recommendations of the Richard, Sainsbury and OECD reviews, a strong principle is in place, in line with international best practice, in which there will be one apprentice standard per occupation. The remaining challenge, complementing this principle, is that of developing a clear logical relationship between apprenticeship and other vocational qualifications. This relationship should be addressed more readily through the joint responsibility for new T-levels and apprentice standards under the same regulatory roof in the Institute for Apprenticeships.

The levy may encourage apprenticeship

If levy-paying employers use rather than lose the funds that have accumulated in their digital levy accounts, they would seek ways of increasing the number or level of their apprenticeships. This may involve a substitution of apprenticeships for other ways of acquiring and developing workforce skills. The substitution of existing training by apprenticeships will be positive if robust quality assurance ensures that those apprenticeships are of high quality.

Traineeships are promising

The new traineeships appear to have positive outcomes. Although they are still small in scale relative the large pre-apprenticeship systems of some other countries, they provide a strong foundation for growth and development.

Data and evaluation are strong

As the reforms go forward, England will be powerfully assisted by increasingly good data on the outcomes of apprenticeship, and very good quality analysis of policy from diverse points of view.

But significant challenges remain

Despite these strengths, international comparison suggests that there is still a long way to go to establish an apprenticeship system in England to match those of the strongest countries. A large proportion of apprenticeships in England still involve low-level skills, acquired in a period of little more than a year, with a limited component of general education, and with most of the training taking place off the job. Work-based learning is under-developed. One in five apprentices is paid below the legal minimum wage, and there is limited support for those at risk of dropping out. In all these areas, improvements are needed. Many challenges are also emerging in realising the full implementation of the principles implicit in current reforms. International comparison suggests a number of ways in which reforms might be adapted to achieve higher quality and better outcomes for the English apprenticeship system. These are set out below in summary, and explained in depth in the remaining chapters of this report.

Assessment: Challenges and policy pointers

Promoting and strengthening youth apprenticeships (Chapter 2)

While England faces major challenges in transitioning young people from school to work, youth apprenticeship currently makes a limited contribution to this task, as most recent growth has been in adult apprentices. Young people in England perform less well on basic skills than their peers in many other OECD countries. Young apprentices in England, because they are treated as employees rather than students, do not receive the social benefits available to young apprentices in some other European countries. Compared to other countries, apprenticeship for young people also includes a relatively limited component of general education, including not just literacy and numeracy but wider topics that contribute to citizenship as well as further study.

Policy pointer 2.1: Promoting youth apprenticeships

In the light of a significant challenge of transitioning young people with poor school attainment into good quality jobs, the government should seek an expansion of quality youth apprenticeships, as in other countries, where such apprenticeships play a major role. Options include:

Evaluate the impact of the existing wage setting on provision of apprenticeship by employers in different sectors, and on the uptake of apprenticeships by individuals across different age groups.

Explore whether the threshold effect induced by a sharp wage increases when an apprentice turns 19 or completes the first year of apprenticeship may prevent employers from providing longer apprenticeships.

Ensure that where youth apprentice wages are low, they are balanced by extensive benefits to the young apprentice in terms of the quality of the learning opportunities with the employer to avoid exploitation of youth apprentices as unskilled labour (as also argued in Chapter 3).

In recognition of their status as a learner (as well as a worker), apprentices aged 16-19 (and their families) should be eligible for social benefits sufficiently attractive to allow youth apprenticeship to compete fairly, and without any bias in connection with social background, with other educational programmes for 16-19 year-olds.

In line with other targets for apprenticeship, set up a target for an expansion of youth apprenticeships.

Policy pointer 2.2: Giving attention to wider education in youth apprenticeship

The broader education of young apprentices, including numeracy, literacy and digital skills, is extremely important. While more young people have weak numeracy and literacy skills in England than in many other countries, young apprentices receive less general education than their apprentice counterparts in many other countries. New requirements for the study of maths and English among apprentices are to be welcomed, but they do not go far enough. They do not address the needs for higher-level literacy and numeracy skills, and wider education, so as to support higher-level apprenticeships and pathways to further study.

In the long run, all apprenticeships should provide more general education, including for apprentices that already have Level 2 English and maths qualifications. More demanding requirements may be necessary for youth apprenticeships, for example through a pre-apprenticeship programme linked to a technical qualification, with general education as a precursor to a full apprenticeship. This would be consistent with the government's broader strategy for post-16 education.

Developing work-based learning (Chapter 3)

Historically, the defining feature of apprenticeship has been a contractual relationship between an apprentice who works and an employer who trains in return. In England, the responsibility of the employer to deliver training on the job has been largely eclipsed by a focus on training delivered usually by a third-party training provider. This is unfortunate, as the key advantage of apprenticeship over other forms of training is on-the-job training, delivered by experienced workplace practitioners. Nearly one in five apprentices are paid below the legal minimum, and even if apprentices receive the apprentice minimum wage there is a risk that they may be exploited as unskilled labour.

Policy pointer 3.1: Developing training on the job

As an integrated combination of external education and training and work-based learning is the most effective way of preparing apprentices for working life, employers should be encouraged to take more responsibility for work-based learning.

This can be achieved by introducing regulations and standards for work-based learning, and by investing in the training capacity of employers.

This may involve:

Clarifying and strengthening, within the apprenticeship standards, what is expected of employers (as opposed to what is expected of training providers) in terms of work-based development that goes beyond the funded off-the-job training element. Work-based training should not only be fundable in principle, but encouraged or mandated systematically in all apprenticeships.

Developing training for employer based supervisors of apprentices as part of a broader process of upgrading and professionalising work-based learning.

Enhancing collaboration between training providers and employers, with training providers not only providing guidance to students in the workplace, but also providing guidance to workplace supervisors of apprentices over how practices at work can assist learning, and how productive work, linked to structured feedback on performance, can blend work and learning.

Ensuring that apprenticeship is not used to exploit apprentices as unskilled labour through active enforcement of standards on employers.

Enforcing rigorously the existing minimum wage requirements for apprentices.

Funding and the levy (Chapter 4)

While the introduction of the apprenticeship levy may encourage larger levy-paying employers to restructure and expand their training and skills development around apprenticeships, there is a risk that this might sometimes involve substitutions that meet levy requirements, but make more limited contributions to skills development. Some key parts of effective apprenticeship systems, are not funded through the levy, but do need to be supported in one way or another.

Policy pointer 4.1: Giving priority to quality

The introduction of the levy may have incentive effects on levy-paying employers, who will seek to increase apprentice numbers to spend their levy pots. Often this will involve restructuring other training and replacing other means of recruiting skilled workers. To ensure that the levy incentives work constructively, the strongest possible quality assurance measures will be needed so that apprenticeship training is of high quality, so that the restructuring involved adds value.

Policy pointer 4.2: Funding for an effective apprenticeship system

Under current rules, the apprenticeship levy provides funding for apprentice training and assessments delivered by registered training providers and assessment bodies, but not to other bodies or for other purposes. Quality assurance in the system primarily follows the funding, and therefore looks at these activities and bodies. However, an effective apprenticeship system involves a wide range of broader functions, including the development of the apprentice in the workplace by the employer (in parallel to any off-the-job training), the broader education of young apprentices, preparation for apprenticeship through traineeship and other pre-apprenticeship schemes, support and advice for apprentices and training employers seeking to get the best out of the apprenticeship system. While it may not be appropriate to fund all these activities through the levy, they do need to be supported, funded where necessary and their quality assured.

Quality in apprentice qualifications and assessment (Chapter 5)

While some strong principles are now in place, implementing an effective apprentice qualification system poses significant challenges. Apprenticeship qualifications need to be sufficiently broad, and few in number, to allow apprentice graduates to change employers and develop their careers, and to sustain the resource demand of continued updating. They will also need to be clearly articulated with associated T-levels, so that apprentices can see how to manage their programmes of study to realise the competences required for their target careers. The proposed competitive market in the provision of end-point assessments is an obstacle to consistency in standards. There is, as yet, no clear arrangement to allow informally acquired skills to be certified through the end-point assessments associated with apprenticeships, without going through an apprenticeship programme.

Policy pointer 5.1: Delivering a coherent apprenticeship qualifications system

A credible and robust system of apprentice qualifications needs to be coherent with the wider system of vocational qualifications and manageable in number. International experience offers some guidance:

Apprentice standards represent the requirements for the target occupation, and should therefore be closely articulated with any related technical qualification. One option would be to require all graduates of associated technical qualifications to take the apprenticeship exam to certify their occupational competence. A second option would be to establish a technical qualification as a preparatory programme for a linked apprenticeship.

To ensure the transferability of skills, the IfA needs to ensure that each proposed standard represents a wide occupational field and therefore reject proposals that do not do so, aiming to keep the eventual total number of standards well under one thousand.

In the context of upskilling adult learners, a more effective framework for recognising prior learning needs to be developed within the frame of apprenticeship standards and levy funding. This will need to support the top-up training and assessments for those who are able to pass the end-point assessment, but have not pursued regular apprenticeships.

Policy pointer 5.2: Ensuring reliable end-point assessments

Few, if any, other countries seek to achieve consistency in assessment standards through multiple bodies conducting the assessment, and consistency in standards will be impossible to achieve with current plans for multiple assessment bodies for individual standards. Given the key role of consistent assessment standards in the credibility and reputation of apprentice qualifications these plans should be reviewed.

Equity and inclusion (Chapter 6)

New apprenticeship standards are, rightly, intended to be more demanding than previous apprenticeship qualifications. But this shift of the apprenticeship offer upmarket raises a challenge over how the system will serve the many low-skilled school leavers, who will need careful preparation and support if they are to succeed in this more demanding environment. One major challenge lies in whether labour market demand will also move upmarket to absorb the better skilled apprentice graduates. Traineeships are promising, but still relatively modest in number. Dropout from apprenticeship is already a challenge, and other things being equal, dropout rates might rise with more demanding standards and end-point assessments.

Policy pointer 6.1: Developing pre-apprenticeships and special apprenticeship schemes

A key element in the success of a reformed apprenticeship system will be its capacity to include and engage those from disadvantaged backgrounds, and those who leave school with few skills. Building on the experience of traineeships, further explore, in the light of evidence and experience, pre-apprenticeship and alternative apprenticeship programmes that effectively prepare young people to undertake a full apprenticeship, equip them with basic and employability skills, and grant them workplace experience and career advice.

Policy pointer 6.2: Supporting apprentices to successful completion

Consider establishing an apprenticeship support service. Through that service, offer targeted support to assist through to completion apprentices in need, or at risk. Such measures may include additional training in basic skills, mentoring and coaching, and other work-based measures.

Special types of apprenticeship (Chapter 7)

Different economic sectors and different types of apprenticeship present special challenges. Degree apprenticeships are likely to grow rapidly as they allow those involved to escape student loans. This will only be a positive development if it restructures university degrees into quality apprenticeships, rather than just a part-time degree plus a job. Small employers play a big role in apprenticeship provision, and may need special support to sustain further growth in their role. There are questions over the rationale for expecting large public-sector employers to invest in workforce skills (as well as taking more youth apprentices), given that the public-sector workforce is already relatively skilled.

Policy pointer 7.1: Securing a constructive use of degree apprenticeships

The expansion of degree apprenticeships should be a means of ensuring that the benefits of integrated on and off-the-job training are realised in these programmes rather than a means of restructuring full-time degrees as part-time merely to attract levy funds. To this end, ensure that all degree apprenticeships involve a clear commitment from employers to provide a substantial element of on-the-job training, closely aligned with the programme of studies pursued in a university. This proposal draws on the expectations for on-the-job training discussed in Chapter 3, and policy pointer 3.1.

Policy pointer 7.2: Supporting small and medium-sized employers

Small employers already make extensive use of apprenticeship in England. To support further growth and enhance quality, facilitate support services for smaller employers, advising them on how to make most effective use of apprenticeship, and supporting local networks of co-operation between employers with apprentices.

Policy pointer 7.3: Underpinning the public-sector target with wider policy goals

The public-sector workforce has better skills, on average, than the private sector. Any targets for the public sector might therefore be limited to the use of apprenticeship as a recruitment tool, in particular for youth apprenticeship.

Timescales and priorities for policy development and reform

The pace of reform is demanding

All the stakeholders in the English apprenticeship system are grappling with extensive change and reform on a scale unmatched by the experience of other countries. While supporting the overall direction of reform, this report makes suggestions for additional elements which need to be addressed to support high-quality apprenticeships. Clearly, implementing these suggestions could place additional burdens on the policy-making apparatus at a time when it is already under great pressure.

Reforms need to be prioritised, but some are urgent

This point is recognised. Some of the suggestions in this report, for example for stronger support services for smaller employers (see Chapter 7), are not necessarily immediate priorities. But some others are urgent, simply because of the pace of change. Chapter 3 points out the serious problem of apprentices being paid, unlawfully, less than the minimum wage, and the risk that apprentices, even if paid the minimum wage, might be exploited to perform unskilled work. If these problems are not tackled urgently they will stigmatise the whole apprentice brand. Chapter 5 of this report expresses concern about a potential rapid proliferation of over-numerous apprenticeship standards. If such proliferation takes place then it will be extremely difficult to prune back established standards to a more appropriate form and number. Chapter 7 sees degree apprenticeships as an opportunity, but also points to the risk that they could involve a pointless reshuffling of existing degrees into part-time degrees juxtaposed with a job, merely to attract levy funding. Here again, prevention will be much easier than cure. So overall, some triage of policy suggestions in this report according to urgency (as well as importance) will be necessary. Overall, this may raise questions about the pace of change. There will be a need for careful evaluation and monitoring of the reforms as they develop, and England has the data and analytic capacity to do this well. It will also be necessary to learn lessons from this emerging evidence, and change course when necessary.

Quality in apprenticeship is more important that quantitative targets

In sum therefore, the goal of quality in apprenticeships is paramount, and this will require substantial investment on several fronts, as set out in this report. Many of the quality requirements cannot be postponed. This goal of quality must also be a very clear priority, relative to quantitative targets, including the high-profile target of three million apprenticeship starts.

References

Amin-Smith, N., J. Cribb and L. Sibieta (2017), Reforms to Apprenticeship Funding in England Institute for Fiscal Studies, Institute for Fiscal Studies, London, United Kingdom, www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/budgets/gb2017/gb2017ch8.pdf.

BIS (Department of Business, Innovation and Skills) (2016a), Consultation on Apprenticeship Targets for Public Sector bodies, BIS, Sheffield, United Kingdom, www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/494493/bis-16-24-apprenticeship-targets-for-public-sector-bodies.pdf.

BIS (2016b), BIS Single Departmental Plan: 2015‑2020, BIS, Sheffield, United Kingdom, www.gov.uk/government/publications/bis-single-departmental-plan-2015-to-2020/bis-single-departmental-plan-2015-to-2020.

BIS (2014), “Apprenticeships evaluation: Learner survey”, BIS Research Paper, No. 205, BIS, London, United Kingdom, www.gov.uk/government/publications/apprenticeships-evaluation-learner-survey-2014.

DfE (Department for Education) (2017), Apprenticeship Funding: How it Works, www.gov.uk/government/publications/apprenticeship-levy-how-it-will-work/apprenticeship-levy-how-it-will-work.

DfE (2017), Further Education and Skills in England. October 2017, DfE, London, United Kingdom, www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/650515/SFR53_2017_FINAL.pdf.

DfE (2016), Apprenticeships Evaluation 2015 – Learners, A report by IFF Research with the Institute for Employment Research at the University of Warwick, DfE, London, United Kingdom, www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/562485/Apprenticeships_evaluation_2015_-_Learners.pdf.

European Commission (2013), Background Paper Mutual Learning Programme. Learning Exchange on ‘Apprenticeship Schemes’ Vienna, Austria ‑ 7 November 2013, http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=1073&eventsId=941&furtherEvents=yes&preview=cHJldkVtcGxQb3J0YWwhMjAxMjAyMTVwcmV2aWV3.

Hargreaves, J., J. Stanwick and P. Skujins (2017), The Changing Nature of Apprenticeships: 1996–2016, National Centre for Vocational Education Research, Adelaide, Australia.

HM Treasury (2015), Summer Budget 2015, www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/443232/50325_Summer_Budget_15_Web_Accessible.pdf.

House of Commons (2017), Apprenticeships. Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and Education, Committees Sub Committee on Education, Skills and the Economy, www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmese/206/206.pdf.

House of Commons (2016), Compendium of Apprentice Statistics. Briefing Paper 06113, http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN06113#fullreport

HRDF (2016), Malaysia Human Resources Development Fund (HRDF) website, www.hrdf.com.my/ (accessed 8 February 2018).

ILO-World Bank (2013), Towards a Model Apprenticeship Framework: A Comparative Analysis of National Apprenticeship Systems, International Labour Organization, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, Geneva, Switzerland, www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/---sro-new_delhi/documents/publication/wcms_234728.pdf.

Kis, V. (2010), A Learning for Jobs Review of Ireland 2010, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264113848-en.

Knight, B. and T. Karmel (2011), Apprenticeships and Traineeships in Australia, Institute for Public Policy Research, London, United Kingdom, www.ippr.org/files/images/media/files/publication/2011/10/rethinking-apprenticeships_3-2_Oct2011_8028.pdf.

Kuczera, M. (2017), “Striking the right balance: Costs and benefits of apprenticeship”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 153, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/995fff01-en.

Lanning, T. (2011), Why Rethink Apprenticeships? In Rethinking Apprenticeships, Institute for Public Policy Research, London, United Kingdom.

Musset, P. and S. Field (2013), A Skills beyond School Review of England, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264203594-en.

NCVER (2017a), Data Slicer: Apprentices and Trainees December 2016, NCVER, Adelaide, Australia, www.ncver.edu.au/data/data/all-data/data-slicer-apprentices-and-trainees-december-2016.

NCVER (2017b), Historical Time Series of Apprenticeships and Traineeships in Australia from 1963 to 2017, NCVER, Adelaide, Australia, www.ncver.edu.au/data/data/all-data/historical-time-series-tables.

NCVER (2011), Overview of the Australian Apprenticeship and Traineeship System, www.australianapprenticeships.gov.au/sites/ausapps/files/publication-documents/ncverreport1.pdf.

OECD (2017), Getting Skills Right, OECD publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264280489-en.

OECD (2016), Building Skills for All: A Review of England, www.oecd.org/unitedkingdom/building-skills-for-all-review-of-england.pdf.

Pullen, C. and J. Clifton (2016), England's Apprenticeships: Assessing the New System, IPPR, www.ippr.org/files/publications/pdf/Englands_apprenticeships_Aug%202016.pdf?noredirect=1.

Pullen, C. and J. Dromey (2016), Earning and Learning: Making the Apprenticeship System Work for 16‑18 Year Olds, IPPR, www.ippr.org/files/publications/pdf/earning‑and‑learning_Nov2016.pdf?noredirect=1.

Richard, D. (2012), The Richard Review of Apprenticeships, School for Startups, London, United Kingdom, www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/34708/richard-review-full.pdf.

Secretariat for Education and Innovation (SERI) Swiss Confederation (2016), Vocational and Professional Education and Training in Switzerland, Facts and Figures 2016, www.eda.admin.ch/content/dam/countries/countries-content/canada/en/Vocational-and-professional-education-and-training-switzerland_E.pdf.

Skills Funding Agency (SFA) (2017), “Apprenticeship Funding: Rules for Employers May 2017 to March 2018. Version 1.” www.gov.uk/government/publications/apprenticeship-funding-and-performance-management-rules-2017-to-2018.

Wolf, A. (2015), Fixing a Broken Training System: The Case for an Apprenticeship Levy, Social Market Foundation, www.smf.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Social-Market-Foundation-Publication-Alison-Wolf-Fixing-A-Broken-Training-System-The-Case-For-An-Apprenticeship-Levy.pdf.