The Netherlands is a decentralised unitary state (OECD, 2017c). The subnational level comprises two tiers of government with general competencies: the provinces (provincies) and the municipalities (gemeenten). Each level of government has its own responsibilities, with the national government providing unity through legislation and supervision (OECD/UCLG, 2016). The municipality of Amsterdam is located in the province of North Holland. In the Dutch territorial governance system, the central and local levels of government are generally the strongest, with the provincial level in between, with relatively less power. For example, provincial budgets are only about one-tenth of the municipal budgets (OECD, 2017f). However, the provinces play a key role in vertical co-ordination, bringing together formal and informal stakeholders from the different levels of government.

Working Together for Local Integration of Migrants and Refugees in Amsterdam

Chapter 3. Block 1. Multi-level governance: Institutional and financial settings

Enhance effectiveness of migrant integration policy through vertical coordination and implementation at the relevant scale (Objective 1)

Division of competences across levels of government

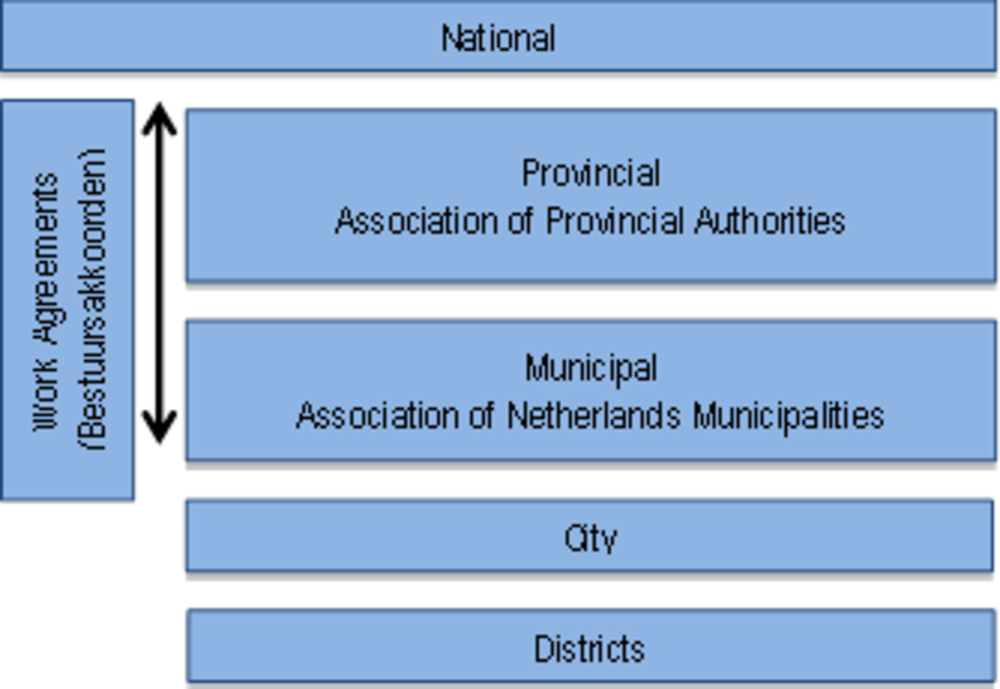

Figure 3.1. Levels of governance in the Netherlands

The Dutch system has evolved over recent years as a result of continuous decentralisation processes. The central government is generally responsible for tasks concerning the Dutch society as a whole. It also provides general guidelines for future development and operates directly at the local and regional levels through a large number of central government agencies, directly controlled and financed by the central government, such as the regional labour market offices, regional police services or regional healthcare services (OECD, 2014). The centrepiece of the co-operation between the subnational and central levels are several work agreements (bestuursakkoorden) on a wide variety of topics (Charbit and Romano, 2017[6]). Associations of local governments such as the Association of Netherlands Municipalities (Vereniging van Nederlandse Gemeenten, VNG1), the Association of Provincial Authorities (Inter-Provinciaal Overleg, IPO) and the Association of Regional Water Authorities (Unie van Waterschappen, UvW) (OECD, 2014; 2010) are involved in these agreements. In particular, the VNG takes part in every decision were municipalities are involved: housing, employment, health, civic integration, participation, etc. The VNG is the main negotiator with the government. These work agreements grant the provincial and municipal levels a relatively large degree of autonomy. While they lack legislative powers, these levels can make additional regulations within the framework of national regulations.

The municipal government is seen as the main provider of public services to the citizens. In particular, the municipal level is responsible for: the establishment and maintenance of primary and secondary education institutions as well as oversight of the implementation of the national education act, adult and vocational education programming and funding, elderly and child care, youth policy, health (general health services, healthcare for drug addicts, centres for homeless people), local social assistance (immigrant reception, employment and income services), local measures for participation and access to the labour market, urban planning, planning permission, participation in housing association decisions with regards to social housing and building on municipal land, municipal medical and administrative services, public order and safety, public transport, the environment, the harbour and many other services.

The city of Amsterdam is further divided into seven geographical city districts. City districts were created in the 1980s and until 2014 had an elected committee (bestuurscommissie). They presently carry out the tasks delegated by the municipal council. City districts usually have five or six departments covering general affairs/governance (public services, logistics, personnel, post and communication services); finances; public space and the environment; well-being (social work, nurseries, elderly and youth, immigrants); education (primary schools) and sports; and labour and housing (markets, shops, building permits, land use). Districts are also responsible for garbage collection, green spaces and the provision of district-bounded welfare services, but they may also support and facilitate migrant integration programmes.

Allocation of competences for specific migration-related matters (excluding status holders)

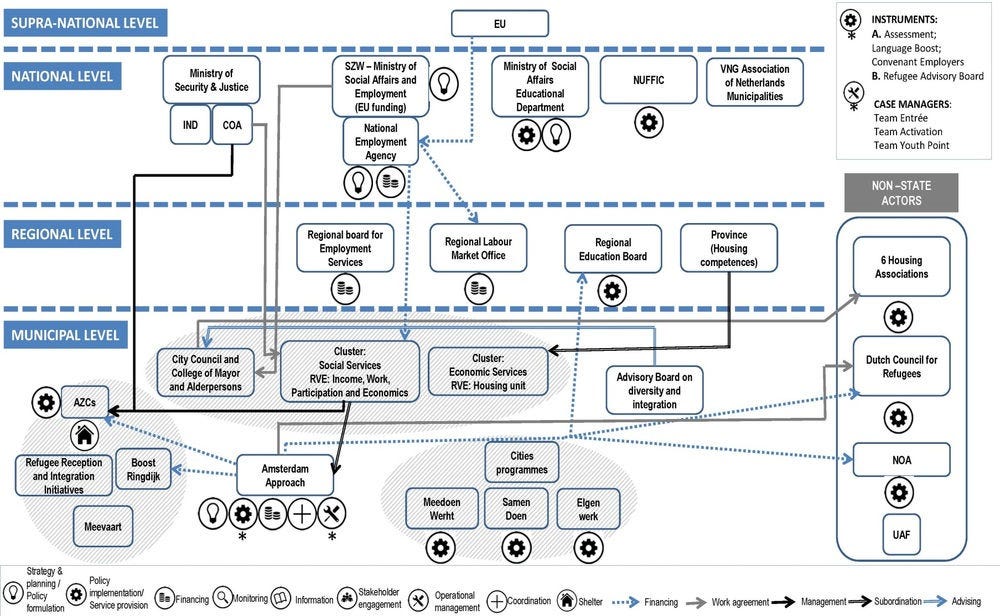

Figure 3.2. Institutional mapping of the multi-level governance of integration related policy sectors

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

With regards to migrant integration, Annex B summarises the division of tasks across the three levels of government for some key competences. It is worth highlighting that until a change in the law in 2013, one specific competence of the municipality in integration matters was to provide language courses (with components on healthcare, childcare and work integration) to migrants who have to pass the Civic integration exam. For this purpose, a specific municipal department had been set up (Education and Integration). Since 2013 this competence is now attached to the national Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment, which organises courses to pass the civic integration exam2 and provides third-country nationals with a loan of EUR 10 000 to cover the costs of language training along with an additional EUR 3503 to enrol for the exam. Since this change, the city of Amsterdam only offers language courses to people who do not fall under the Civic Integration Law.4

Integration-related national-local co-ordination mechanisms

The Dutch government has not adopted a national integration strategy, beside the organisation of the Civic Integration exam, and doesn’t monitor the progress of local authorities against it. National authorities do not dispose of legislative or fiscal means to regulate some of the competences related to migrant and refugee integration. Therefore, they use incentives and have developed alternative measures for co-ordination and dialogue. The central level influences integration results by applying incentives on key groups. For instance the Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment (SZW) offers wage-cost subsidies (i.e. offering a fiscal incentive to a company for hiring students as a trainee) to enterprises to make it profitable to employ certain categories of personnel, for instance migrants and refugees.

In terms of co-ordination mechanisms, there is a tradition in Dutch politics of consensus-based decision-making processes, in dialogue among policy levels, allowing the local level, as well as social partners to engage and voice their position. Recently this practice was applied to issues related to the increase in refugee and asylum seekers arrivals (see Box 3.1) making communication more fluid. As a result, contrary to the other case study cities, stakeholders in Amsterdam did not experience an information gap with the central level. An example of multi-level dialogue is the issue-based roundtables recently organised by the SZW bringing together national and local stakeholders. These dialogue mechanisms provide a space to discuss also migrant and integration-related topics and to adopt nation-wide measures. For instance, the issue of discrimination was addressed with trade unions and the chamber of commerce, as well as representatives from the VNG, launching a programme to raise employers’ awareness of discrimination and introducing anonymous job applications. Another thematic discussion addressed youth involvement to stimulate integration. This practice is in line with traditional Dutch political decision-making model, the so-called “polder model” of achieving deliberation through bargaining between government, trade unions and employers unions.

Further, a new National Action Programme to combat discrimination was announced in January 2016 and is being implemented across all levels of government and encompasses an increased focus on the prevention and awareness of discrimination as well as greater institutional capability to deal with cases of discrimination (OECD, 2017a).

Another example of national/local co-ordination mechanisms related to migration policy is the regional health co-ordinator that has been established by the national Ministry of Health with competences for each working area of the community health services (see Objective 11 for more information).

Box 3.1. The Refugee Work and Integration Task Force (RWITF)

At the national level, a Refugee Work and Integration Task Force (RWITF) was established to co-ordinate work among the key actors involved in the reception and integration of asylum seekers. This umbrella organisation brings its stakeholders together regularly. The most directly involved national ministries and actors are: Social Affairs and Employment; Security and Justice; Education, Culture and Science; the Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers (COA); and the Institute for Employee Benefit Schemes (Uitvoeringsinstituut Werknemersverzekeringen, UWV). The municipalities are represented through the Association of Netherlands Municipalities (Vereniging van Nederlandse Gemeenten, VNG) and the G4 composed of the bigger Dutch cities of Amsterdam, Utrecht, Rotterdam and The Hague, as well as the Social and Economic Council. In addition, social partners and key non-governmental organisations are involved, for example the Dutch Council for Refugees (Vluchtelingenwerk), the University Assistance Fund (Stichting voor Vluchtelingen-Studenten, UAF), Dutch refugee organisations and Divosa (association of executives in the social domain). A website* provides information about legislation, policy, support options and best practices for employers, educational institutions and social organisations (Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment, 2016). This constitutes an example of unique vertical co-ordination that also serves as a platform for engaging non-state actors and produces critical information for all actors involved in the response to refugee reception and integration.

Interaction with neighbouring communes to reach effective scale in social infrastructure and service delivery to migrants and refugees

As mentioned above, the VNG is the municipalities’ main negotiator with the central government when it comes to aligning national objectives for migrant integration with local ones (concerning housing, employment, health, civic integration, etc.). Co‑ordination between different cities, including the city of Amsterdam, and other municipalities is clearly institutionalised through the VNG. Amsterdam is closely tied to the VNG, and the Alderperson, who is responsible for the portfolio’s work, participation, income of Amsterdam, is currently a member of the VNG board, and is chairing the VNG Commission of Work and Income. This allows for high-level representation in the VNG and also links the two institutions through one person.

The city of Amsterdam co-ordinates with municipalities and provinces across its functional urban area through the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area (Metropoolregio Amsterdam, MRA). Established in December 2007, this informal partnership makes agreements in the fields of traffic and transport, economy, urbanisation, landscape and sustainability; it has a revolving presidency among its member municipalities and provinces. Three committees drive its work: 1) planning; 2) accessibility/transportation; and 3) the economy. Some of its tasks include: jointly agree and co-ordinate on housing issues; transform offices into temporary spaces for living and working through such measures as flexible zoning; transform and/or restructure the obsolete greenhouse area at Greenport Aalsmeer into new spaces for living and/or working (OECD, 2017g).

In addition, Amsterdam is member of a union composed by three other major Dutch cities, the so-called: G4 (composed by the city of Amsterdam, The Hague, Rotterdam and Utrecht). The G4 was established in the 1990s and since 2003 is also represented in Brussels, where it monitors EU policy and legislative developments. Based on the initiative of the G4, a Large Cities Policy (GSB) was established in the Netherlands allowing cities to determine for themselves how results shall be achieved in different areas. Between 2005 and 2009, “improving integration and citizenship” was one of the main topics of the GSB, which includes 31 large and medium-sized cities (European Urban Knowledge Network, 2012). Over the course of this period, 38 more medium-sized municipalities formed a similar network, referred to as the G32. Together the G32 and the G4 form the G41. The goal of this network is to represent the common interests of the cities to other levels of government and to exchange knowledge, including on migration and integration policies when relevant.

In May 2016, the 35 municipalities, including Amsterdam, which make up the Labour Market Regions, applied for a European Social Fund (ESF) of EUR 116 million targeting refugee integration. The programme aims at helping status holders find jobs and learn the language. Through this co-operation, additional finances were made available to municipal authorities (Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment, 2016). The municipalities of this region co-operate and have regular meetings involving representatives of the private sector to mobilise the largest employers of the region’s 35 municipalities.

Seek policy coherence in addressing the multi-dimensional needs of, and opportunities for, migrants at the local level. (Objective 2)

City vision and approach to integration

As elaborated in part one of this case study, large gaps can be observed with regards to educational and labour indictors comparing Amsterdam’s native-background and migrant-background populations. Further, recent surveys show that 28% of the non-western residents in Amsterdam feel discriminated against (Geemente Amsterdam, 2016a) and only about half of the population (49%) agrees that foreigners who live in their city are well integrated (EUROSTAT, 2016b). This data indicates the need for an even higher level of engagement from the city’s leadership to further improve integration outcomes and the perception of different groups.

While there is no migrant integration strategy as such, the city has formulated in its policy documents a definition of integration as “mutual acceptance by both the host society and immigrants, as well as active participation by the immigrants” (Gemeente Amsterdam, 2003) which includes a socio-cultural focus compared to policies in other cities or at the national level that are more focused on socio-economic aspects of integration (Scholten, 2012). The city’s approach values the contribution that migrant bring to the society by, as a municipal administrator said during OECD fieldwork, “building an urban network around migrant and refugees”.

Box 3.2. Evolutions of integration concepts and regulations at national and local level

Great changes occurred regarding the vision and policy of integration, which has occupied a central place in Amsterdam’s social and political life since the 1970s. It can be said, that local and national integration policies largely followed the same trajectory regarding changes made in integration policy (Scholten, 2012). When the country received the first large waves of immigrants, who were predominantly from Morocco and Turkey, in the 1960s and 1970s, they were called “guest workers”, under the assumption that they would eventually return to their home countries. Multiculturalism as each ethnic minority maintaining their identity and culture of origin was then the main approach at national and local level (Bruquetas-Callejo et al., 2007). In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the city of Amsterdam pushed further the national view of multiculturalism and adopted a pluralist minorities policy: minorities should integrate while maintaining their cultural identity. However, once it appeared that the nature of the migrants’ stay was not temporary, their disadvantaged socio-economic position increasingly became a topic of concern. Municipalities were the first to get involved in providing housing, education, healthcare and welfare for migrants, pressuring the national authorities to recognise and finance these measures. In parallel since the 1980, local and national level slowly shifted away from the vision of a multicultural society, towards more proactive approach to learning the language and integrating. The 1994 integration policy for ethnic minorities (Contourennota Integratiebeleid Etnische Minderheden) emphasised the need for migrants to learn Dutch and Dutch culture.

In addition to self-responsibility, the narrative of integration policies moved towards a need-based “generic” approach in the attempt to achieve universal access to services for all individuals. Integration is about targeting individual’s situation of vulnerability and talent (Bruquetas-Callejo et al., 2007) rather than groups, through policies that are “generic where possible, and specifically where necessary” (Wittebrood and Andriessen, 2014: 5). In this sense, in 2003 a note was published in Amsterdam aiming at reducing the specific character of integration policy and mainstreaming it into general policies. Thus, policy is not determined for pre-defined groups, but if it appears that certain characteristics (e.g. age, origin, level of education, sexual preference) are strongly correlated to specific problems, policy can be tailored towards these aspects. As an example, specific compulsory integration courses are offered to migrants. In 2005 the city issued a memorandum called “We the people of Amsterdam”, emphasising the link between integration, participation and interethnic contact and also pursuing harder measures regarding crime and radicalisation (Scholten, 2012).

More recently in 2007, the Dutch government introduced a compulsory civic integration exam for third-country nationals (Wet Inburgering Nieuwkomers), emphasising the voluntary aspect of integration. Newcomers have to pass a language and culture test within three years of receiving their legal residence permit in order to be naturalised. Once the exam is passed, and within five years of receiving their residence permit, they can be naturalised. A new provision was added in October 2017: the participation declaration adhering to Dutch norms and values, illustrating the perception of integration as a necessary step on the side of the migrant who needs to show his/her willingness to adhere to national rights and obligations.

The current policy vision is implemented through: 1) a close monitoring of socio-economic results of all groups in the city in order to identify potential obstacles to equal services and opportunities ( see “Monitoring integration outcomes” in Chapter 5); and 2) the development of transversal thematic strategies and policies. These initiatives address certain factors that could have an impact on the outcomes of specific groups including migrants. These thematic strategies are implemented across the municipal departments and in collaboration with civil society. Examples of thematic strategies that the city developed to raise awareness around cultural diversity and to act upon factors undermining integration are: Amsterdam Human Rights Agenda – aiming at creating a just living environment for all through knowledge of the rights-; the “Sharing History” programme -to teach residents about the history of their city and inhabitants-; the city Policy Framework Anti-discrimination (2015-19) and the Implementation Pink Agenda (LGBTQI empowerment), such as racism, discrimination, radicalisation, etc.

More recently the city created entry points for specific migrant groups who seek opportunities to become active citizens, get engaged in the city, understand and share its values. While breaking the generic approach, these measures embrace a voluntary vision of integration, where individuals are enabled to build their own diverse urban network. The city identified some groups, who are left out of the national Civic integration policy, who felt their language skills were not sufficient to fully integrate into Dutch society and cultural life. Thus the municipality extended language and cultural courses to EU migrants, over 65 and migrants who already passed the civic exam. Comparably, the “Local Welcome Policies for EU Mobile Citizens” is a one-stop-shop for EU migrants who want to better integrate and participate in the city life. The city’s practices targeting EU citizens are shared with other European cities and resulted in a “Welcome Europe toolkit: Local welcoming policies for EU citizens”.5

Lately municipal policies included group-targeted measures to respond to the increase in refugees and asylum seekers arrivals. The “Amsterdam Approach Status-holders”, that will be explained in detail in “The Amsterdam Approach Status-holders: Time applied to refugee integration” in Chapter 4, is in line with the idea of building a network around newcomers and tailor educational or employment opportunities to the person’s capacities and aspirations. Whether this policy is to be understood as another flection from traditional generic approach or whether, based on the results of the current experience, the municipality will lean towards more group-specific measures is something to be decided when designing the next local policies based on the results of the ongoing evaluation.

Communication with citizens

The city affirms its cultural and ethnical diversity and pursues active policies to increase it by attracting international students and high-skilled migrants. However it doesn’t produce communication campaign around integration issues, probably because it would be hardly relevant to communicate about such a vast and diversified group that represents 51% of the population. Nevertheless several efforts have been put in place since 2015 to communicate the city’s response for receiving and integrating refugees and to measure the opinion of the public by conducting quarterly surveys on the perception to the measures displayed to welcome refugees.

In particular the city communicated around the decision to give priority access for refugees to social housing (see Objective 10). Only 14% of the respondents to a survey conducted by the city (see “Intensify the assessment of integration results for migrants and host communities and their use for evidence-based policies (Objective 8)” in Chapter 5) is in favour of this regulation, while 86% of the respondents support the housing of refugees in vacant office spaces, buildings or churches (Gemeente Amsterdam, 2016b). To avoid tensions with host communities over this decision, the municipality set up four locations for dialogue to explain clearly the rule of the distribution of housing.

Horizontal co-ordination infrastructure at the city level

In the city, powers are divided between the deliberative council (gemeenteraad, also referred to as the municipal or City Council) elected by popular vote, and the executive body called the College of Mayor and Alderpersons (college van burgemeester en wethouders) appointed by the City Council, except for the Mayor. Following the 2014 City Council elections, a governing majority was formed between the social liberal party D66, the conservative-liberal party VVD and the socialist party SP. This is the first coalition without the social-democratic labour party PvdA since the Second World War. At time of writing the city had nine alderpersons, all with a different portfolio and responsibility for a district. For instance: aldersperson for “Employment, income and community participation”, for “Education, youth, diversity, integration and the City district of East”, etc. Under the city council and College of Mayor and Alderpersons, four main clusters make up the city’s administration: economic services, community services, administrative services and social services (see Figure 3.2). These clusters include multiple departments (RVEs) that fit within the specific domain but have their own expertise. Departments can work together on certain policies, within and between clusters.

While the next section discusses the governance of the refugee reception and integration programmes in more details, here we focus on the interactions of the different departments involved in delivering services relevant for integration issues. There is no stand-alone unit dealing with migrant integration. In the past there were some units, such as the Education and Citizenship (Educate en Inburgering) Unit or the Diversity Unit (Unit Diversiteit), which were directly in charge of providing citizenship and language courses for immigrants and of the implementation of the policies towards immigrant associations, as well as the Platform Amsterdam Together (PAS), which ran a programme “We Amsterdammers” from 2005 to 2010. The organigram changed as a consequence of the 2013 reform which centralised the competence for providing language and cultural courses to migrants from the municipal to the national government.

Portfolios often do not overlap between political and administrative levels. For instance, an alderperson in charge of employment, income and community participation is responsible for issues that cut across the social services as well as the economic services of the city’s administration. At the same time these same departments could also partially be under the political responsibility of other Alderperson in charge for instance of youth. Thus a transversal issue, such as integration, not only falls within the responsibility of different departments but also of different decision makers. To what extent this plays in favour of more coherent integration policies depends on many factors. For instance, this could translate in a lack of strong leadership, as responsibility is shared across different alderpersons. On the other hand, a common political will shared by several high-level decision makers can make integration the priority in the work of all departments.

An example of a horizontal mechanism for sharing responsibilities across city departments for policies related to migration issues is the anti-discrimination policy. Several administrative portfolios are concerned by this cross-cutting issue: public order and safety, education, work and economy, and municipal personnel management. Beyond the city’s administration, other partners are involved in the implementation of this strategy, including the Amsterdam Discrimination Complaints Office, the Amsterdam police unit, the Public Prosecution Service, civil society organisations and city districts (Gemeente Amsterdam, n.d.). The anti-discrimination policy was approved by the city council and is executed across all the responsible departments who co-ordinate with each other through regular meetings.

Multi-level governance of the reception and integration mechanisms for asylum seekers and refugees

Asylum seekers and refugee regulation

In the Netherlands, an agency of the Ministry of Justice called the Immigration and Naturalisation Service (Immigratie en Naturalisatiedienst, IND) assesses asylum applications and grants international protection status (i.e. subsidiary protection or refugee status) to humanitarian migrants on the basis of the Aliens Act (Vreemdelingenwet). In 2015, around 70% of all applications were approved (Gemeente Amsterdam, 2016b), compared with 51% in the EU28.

Several policy changes were made at the national level in 2014 with regards to asylum legislation. This was often directly related to the implementation of the Common European Asylum System and aimed at introducing more efficient admission procedures, including accelerated processing, earlier submission of claims at the initial registration process, and more favourable conditions for the family reunification of those who were granted refugee status. New guidelines were also implemented to improve the position of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people in the asylum procedure (OECD, 2017a).

In general, the central government is responsible for the initial reception and related procedures, while local authorities focus on the long-term integration of refugees: competences over housing, education and health have been officially allocated to municipalities through the Increased Asylum Influx Administrative Agreement (2015) and supplementary agreements in 2016.

The Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers (Centraal Orgaan Asielopvang) COA6 is responsible for asylum seekers while they are waiting for recognition of their status. However, in late 2015, the government devolved the responsibility for the provision of emergency shelters to the local authorities in the Netherlands in order to cope with the large influx of asylum seekers. Generally, asylum seekers stay in these emergency shelters for 6-12 months while waiting for a place in a regular asylum seeker centre (Asielzoekerscentrum, AZC). In 2014 and 2015, the COA increased the capacity of existing reception centres and opened 20 new (emergency/temporary) ones with a total capacity of nearly 10 000 beds (OECD, 2016h).

The COA distributes asylum seekers across the AZCs based on availability. Currently, asylum seekers are accommodated in the AZCs located throughout 90 locations in the Netherlands. Forthcoming OECD analysis on the presence of asylum seekers at the municipal level across OECD countries confirms that in the Netherlands asylum seekers are concentrated in towns and suburbs rather than in rural areas (OECD, forthcoming). The COA is in charge of managing the AZCs and decides where they will be established, but cities can apply for a centre, like Amsterdam did.

Amsterdam opened an AZC in August 2016 located in a former prison in the eastern part of the city that provides shelter for 1 000 people. Furthermore, two new centres were planned to open in the western part of the city in 2017 and 2019 to shelter about 500 people each. However, due to a lower7 demand for shelter, one of these centres will most likely function as a bridging solution.

The centres provide asylum seekers with essential necessities such as food, clothing and medical care, defined by the “Regulation Care Asylum Seekers”. There is no available estimation of the cost of hosting an asylum seeker in these centres. However, depending on the phase in the asylum-seeking procedure, an asylum seeker receives around EUR 58 per week for food and clothes. In certain cases, expenses are paid for kitchen utilities, public transport, education and particular healthcare needs. These measures are paid for by the central government. Sometimes it is also possible to earn some extra income by performing small jobs. However, asylum seekers are supposed to receive a deduction of their allocation in proportion to their income, up to 60% of the allocation.

Once a person is given a permit of stay based on international protection law, he/she is assigned to a municipality and leaves the AZC. The COA is again responsible for redistributing refugees across municipalities. If the Immigration and Naturalisation Service needs more time to decide on the request for asylum, asylum seekers begin the extended asylum procedure and stay at the asylum seekers’ centre until the procedure is completed. If the asylum seeker has been refused a residence permit he/she may stay at the asylum seekers’ centre for maximum four weeks. They can use this time to prepare for their departure from the Netherlands (Source: COA).

Criteria for dispersal are largely based on population size, that comes down to about 12 refugees per 10 000 inhabitants in 2016 (Geemente Amsterdam, 2016b). Every six months the central government decides how many permit holders each municipality must house. The COA selects a municipality based on a negotiation with the Association of Cities, and tries to match the skills/work experience of recognised refugees with labour market needs across the regions. To do this the COA has piloted a screening process (addressing issues such as: years of schooling, type of education, practised profession, etc.) that should be implemented across the country in 2017. Although the municipality is not officially involved in this process, there is a consultation for the actual allocation to dwellings in the city involving the COA, housing corporations and refugee mentors. The city of Amsterdam tries to influence the COA’s decision by advocating that recognised status holders who spent time in the local AZC stay in the city.

Once recognised as a status holder, but still waiting at the AZC to be housed by the municipality, refugees receive a basic integration package funded by the COA, which includes 121 hours of Dutch classes and cultural background lessons, as well as coaching sessions. The respective municipality may also offer early integration opportunities such as studying, work or volunteer opportunities (for the case of Amsterdam see “The Amsterdam Approach Status-holders: Time applied to refugee integration” in Chapter 4).

Municipalities are required by law to provide housing (Housing Allocation Act [Huisvestinsgwet]) for those refugees allocated to them (see “Secure access to adequate housing (Objective 10)” in Chapter 6), and are also responsible for refugees’ trajectory to settle in their city, including early measures related to the integration process in the sectors of education and access to the labour market. In Amsterdam the process of identifying and contracting a dwelling should take 2.5 days from the moment the refugee is assigned to the city. This delay has increased due to the increased demand in 2014.

Table 3.1. Which level of government exerts a role in refugee integration policies and to which extent is this role exercised in an autonomous way?

|

Function |

City level |

Intermediary level (province, state…) |

Regional level |

National level |

Supranational or international level –including the EU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Policy setting |

B |

A |

|||

|

Budget |

B |

A |

D |

||

|

Staff and other delivery processes |

A |

||||

|

Output (migrant integration policy delivery standards) |

A |

||||

|

Monitoring and evaluation of migrant integration policies |

A |

B |

Note: A: dominant role; B: important role; C: medium role; D: small role; E: blank/no role.

Source: Responses to the OECD questionnaire by the city of Amsterdam, 2017.

Table 3.2. Are the following policies competences of local governments? Please tick the correct box for each

|

Policies |

Local competency |

Shared with other levels of government |

Not a local competency |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of refugees hosted by the city |

X |

||

|

Status of refugees hosted by the city |

X |

||

|

Housing for refugees |

X |

||

|

Education for refugees |

X |

||

|

Work authorisations for refugees |

X |

||

|

Health services for refugees |

X |

Source: Responses to the OECD questionnaire by the city of Amsterdam, 2017.

Division of labour across city departments for reception and integration of status holders

Since 2015 the governance of the reception and integration of recognised status holders assigned to the city of Amsterdam is structured around the “Amsterdam Approach Statusholders” designed and implemented by the Unit of Work, Participation and Income (PWI) within the Social Services Department of the municipality. The concept and services delivered through the Amsterdam Approach Status holders will be explained in detail in “The Amsterdam Approach Status-holders: Time applied to refugee integration” in Chapter 4; this section focuses on the governance mechanisms for managing this approach.

The Amsterdam Approach Statusholders was officially approved by the City council in the course of 2016, identifying the areas of concern, policy priorities, and tangible measures regarding refugee integration. This approach pays special attention to vulnerable migrant groups such as children, unaccompanied minors, and people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or inter-sex (LGBTQI).

Since the increase of refugee inflows, a political decision was made to assign the response to the Work, Participation and Income PWI, which established partnerships within and beyond Amsterdam city services. Traditionally this unit had refugee integration amongst its competences but this represented only a small part of their business. In the wake of the inflows it was given a supplementary budget and mandate to set up a new approach. All relevant city services work together in a chain that has been defined as the Programme Organisation Amsterdam Approach Status-holders Initially a taskforce was established to coordinate all necessary activities across city departments, whereby every department took responsibility within the scope of their core business. Currently, the Amsterdam Approach Status-holders is predominantly executed and coordinated by a team of civil servants from the key departments (i.e., Work, Participation and Income and Economics), while the departments of Housing, Health and Education also have dedicated staff to support (see Figure 3.2). Lately the municipality has decided to set up a Refugee Department. The Amsterdam Approach Status-holders is largely implemented directly by the municipality, department WPI (70 case managers have been directly hired for this purpose; see “Build capacity and diversity in civil service, with a view to ensure access to mainstream services for migrants and newcomers (Objective 6)” in Chapter 5) in collaboration with different national and subnational partners: the COA, the Community Health Service (Gemeentelijke Gezondheidsdienst, GGD), housing associations, social welfare services, employers, as well as civil society initiatives who have a key role (Gemeente Amsterdam, 2015[7]). All these entities hold regular meetings with the aim of sharing information rather than join decision making.

After being assisted through tailored programme to integrate a work or education path during three years, if still in need, status holders are introduced to universal services offered by the municipality for youth or care programs specialised on multiple problems. There is a close collaboration between these universal services and the municipal teams in charge of the Amsterdam Approach Status-holders to ensure the beneficiaries are referred and receive follow up from the right general services.

Funding and costs

Funding was secured for 2016-17. The total budget for the Amsterdam Approach Status-holders (EUR 31.2-35.3 million) is covered by a municipal fund for innovative pathways to work and participation (EUR 10 million), with additional national funding following the increased influx of asylum seekers (EUR 17.2-21.3 million), and European co-financing from the ESF (EUR 4 million) that is managed by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment. The ESF and Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF) funds covered 10-15% of the total cost of Amsterdam’s integration measures. Specifically, Amsterdam recently applied for the AMIF, and for Employment and Social Innovation (EaSI) funding.

Ensure access to, and effective use of, financial resources that are adapted to local responsibilities for migrant integration (Objective 3)

In the Netherlands subnational governments’ investment represents 50% of public investment (OECD, 2014a). The Netherlands scores well below the OECD average in terms of the share of subnational government tax revenues of total public tax revenue (OECD/UCLG, 2016).

For 2017, the city of Amsterdam has an estimated budget of EUR 5.7 billion. Subnational governments (especially municipalities) have a substantial budget composed of several streams. The volume of the funding stream from the central government to a municipality depends on the number of inhabitants with social needs, the number of houses, whether or not the municipality is a regional service hub, and its physical size. In 2017, Amsterdam received EUR 1.9 billion as a general grant. In principle, the central government has the power to intervene in the governance and functioning of subnational governments through the system of subnational government financing but in practice it seldom does (OECD, 2014). The city can allocate national grants as it wishes, with the exception of additional earmarked funding (EUR 660 million were provided to Amsterdam in 2017 for earmarked funding) that is meant for specific policy fields such as primary education or urban regeneration. About 45% of the city of Amsterdam’s budget comes from central government funding. In addition, EUR 650 million is withdrawn from financial reserves, and about EUR 1.4 billion is generated from other sources in 2017.

In addition, municipalities have several own-source revenues, such as local taxes and administrative fees and charges (in Amsterdam this represented EUR 1.06 billion in 2017, or on average 16% of municipal income). The remaining funds stem from various other sources, such as European subsidies and municipal property (VNG, 2014). European funds are generally managed through the Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment (the provincial level is not involved).

As a result of the Participation Law (Participatiewet) adopted in 2015, municipalities now receive bundled funding (BUIG) for multiple social welfare regulations. Municipalities have discretion in the execution of these arrangements. Surpluses can be allocated elsewhere, while shortages have to be supplemented by the municipality itself. This mechanism provided an incentive for Amsterdam to help people become self-reliant as soon as possible, exceeding the target of lifting 4 200 persons out of the social benefit scheme and managing to help 6 000 persons in 2015.

Also in 2015, three laws changed8 related to care, youth and work, leaving the municipality with more responsibility and approximately 25% less money than before when the state owned the process. This process was called 3d (3 decentralisation). Municipalities are in charge of the execution of these laws and have to find creative solutions to maintain more or less the same level of service, which includes key social services addressing migrants as well as other vulnerable groups. Yet, municipal officers estimate that the level of many services, especially those for the elderly and younger people, has decreased.

On the spending side, the City Council can spend local taxes as it wishes and has relative autonomy on the allocation of central funds. In 2017, most funding will go to mobility and urban space (EUR 1.2 billion); employment, income and community participation (EUR 1 billion); and city development and housing (EUR 0.8 billion). Furthermore, approximately EUR 544 million will be spent on education, youth and diversity. Moreover, in both 2017 and 2018 an additional EUR 2 million per year (0.03% of the total city budget) will be allocated specifically to refugee integration support (Gemeente Amsterdam, 2016a).

Key observations: Block 1

Historically Amsterdam considered integration to be one of the city’s top priorities. The 2013 Law on Participation reallocated some of the city’s competences to the national level. The city reacted by increasing the provision of services to those migrants not targeted by the national package.

Flexible national-local co-ordination mechanisms such as roundtables and financial incentives allow the higher level of government to advise and co-ordinate with the local level while still granting a great degree of local independence. A good example is the autonomy in designing refugee reception mechanisms as well as welfare and labour integration measures.

The Association of Netherlands Municipalities (VNG) represents a unique structure for channelling municipal interests to the national level and ensuring two-way information flows. This has proven essential in managing the inflow of refugees effectively.

There is no overall integration strategy as such: the city’s approach is to privilege generic policies and promote equal access for migrants and refugees to public services and participation however adopting specific responses to groups when needs require. There is no integration unit in the municipality; co-ordination is ensured through informal interactions and a clear division of roles between departments in charge of related policies

Notes

← 1. Composed of 338 Dutch municipalities, the association supports the decentralisation process and facilitates decentralised co-operation.

← 2. The current test has four language skills components (speaking, listening, reading and writing), one component about Dutch society, and one about the Dutch labour market (the latter introduced in 2015).

← 3. If the test is passed the loan does not have to be reimbursed.

← 4. EU nationals, people who already passed their integration test and people above the age of 65.

← 6. As an administrative body, the COA falls under the political responsibility of the Ministry of Security and Justice.

← 7. Only 17 000 out of the 50 000 expected refugees after the EU-Tukey agreement in 2016.

← 8. The effect of the Participation Act superseded several social laws in January 2015. For instance, in the care sector the general law on exceptional medical expenses (Algemene Wet Bijzondere Ziektekosten) became the Social Support Act (Wet maatschappelijke ondersteuning), a new law was established for youth care and in the labour sector. Also the Work and Social Assistance Act (Wet Werk en Bijstand) benefits became part of the Participation Law (Source: www.cbs.nl/en-gb/about-us/contact/infoservice).