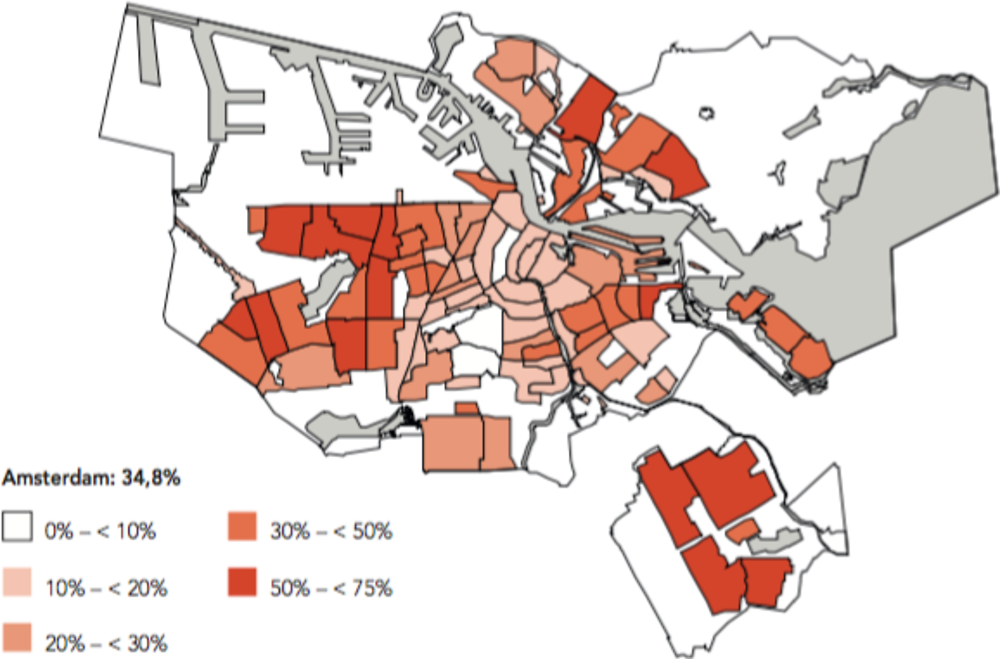

According to a social segregation index, which represents the percentage of low-income households that should move to achieve a completely equal distribution, the city has a moderate level of spatial segregation (Statistics Netherlands, 2014). Amsterdam scores lower on this index than all other major cities in the Netherlands. Further, according to a study comparing the situation in 2001 to that in 2011 for 13 European cities, Amsterdam is the city in which the social mixing of population groups has shown a slight increase (Tammaru et al., 2016; Hoekstra, 2014). The large social housing stock, which in 2015 stood at over 50% of the total housing stock, and its ubiquity and active policies for urban renewal have contributed to producing mixed and heterogeneous neighbourhoods. For instance, since the onset of the crisis, only a few middle-class families in Amsterdam have moved out of inexpensive social housing units, thus maintaining the level of diversity (Tammaru et al., 2016). Still, most social housing is concentrated on the outskirts of the city, with much fewer social housing in the centre and south district (OECD, 2017g). The peripheral districts show a high concentration of people originating from Suriname, Turkey and Morocco, leaving these non-western migrants spatially separated from their more affluent counterparts or native-born Amsterdammers (Cities for Local Integration Policy Network, 2010) There is a risk for “suburbanisation of poverty” (OECD, 2017g), as the inner city is less accessible and affordable and the share of social housing is diminishing. Moreover, as the price of houses within the A10 ring motorway, which delimits the city centre, rises there is a risk of polarisation, as only low-wage earners through social housing and high-wage earners who can pay high private market rent will be able to live there, leaving out middle-income earners (OECD, 2017g).

The accessibility to social housing for lower wage earners became a concern in the late 1990s when the government privatised the housing sector, which lead to rent increases and a decrease in the available social housing: the average registration time for social housing increased to 8.7 years in 2015, compared to 7.9 years in 2010 (Jaarboek Amsterdam, 2016). Under such circumstances, providing affordable housing for all groups and avoiding further segregation is a challenging task for the municipality.

Some segregation is evident between Dutch and migrant cohorts (Musterd and Van Gent, 2016). According to the municipality, many of today’s challenges result from an approach that perceived immigration as a temporary phenomenon requiring minimal policies and guidance. Housing problems first arose in the early 1980s when most of the housing for foreign employees was closed due to bad housing conditions. As a result, more migrants started to enter the social housing market, leading to concentrations of (especially people originating from Turkey and Morocco) migrants in the most deprived neighbourhoods. During this period, the city of Amsterdam became more aware of its status as a city of immigration and the related social implications in terms of segregation and discrimination this entailed. Initiatives started to foster integration, including new housing projects, mostly through individual rent subsidies based on income and household composition. These projects managed, to a certain extent, to improve living conditions, but mainly appeared insufficient because of the large influx of new migrants. A differentiation in housing prices within neighbourhoods was not achieved and today the high rental prices near amenities reflect this trend. As a consequence, a higher concentration of economically disadvantaged people, among them many ethnic minorities, lived together in less-developed neighbourhoods where rents remained lower.