Successful vocational education and training (VET) systems require strong employer involvement. This chapter explores how to make VET in Israel more attractive to employers. In Israel few employers are able to realise long-term benefits associated with recruitment of the most able apprentices, since many young apprentices enter the military service after the end of the programme. The chapter argues that a well-designed apprenticeship can be beneficial to employers even in the short term. To this end, Israel may support employers with providing high-quality training in workplaces. This includes measures such as helping employers with administrative tasks, training of apprentice instructors, and providing additional support to employers offering apprenticeships to disadvantaged youth. The chapter also discusses how to address some key skills shortages. Sectoral training levies initiated by social partners are one option.

Apprenticeship and Vocational Education and Training in Israel

Chapter 3. A closer look at the economics of training in Israel: Involving employers through youth apprenticeship and sectoral training levies

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Introduction: How to engage employers?

An active engagement of employers is a critical precondition for the reform of vocational programmes in Israel. While the involvement of all the stakeholders - public authorities, participants and employers - in the design and provision of work-based learning programmes is a key strength of these programmes, realising this strength is very demanding. Successful involvement of the different stakeholders requires the reconciliation of different interests. This chapter explores two key issues – first, how to design apprenticeships in Israel so as to take account of the economic factors which drive employer engagement, and, second, the arguments how to address some key skills shortages with sectoral training levies being an option.

Employer engagement: An economic perspective

This chapter offers an economic perspective on the costs and benefits of work-based learning

An economic perspective on the costs and benefits of work-based learning provides a framework for the analysis of employers’ behaviour, the conditions under which employers will want to provide work-based learning, and policy options that might further encourage its provision by employers. This analysis draws on findings from an evaluation of costs and benefits of apprenticeships carried out in Germany and Switzerland. This approach is then applied to Israel, taking full account of the different characteristics of Israel. It is applied to apprenticeships for young people under the responsibility of the Ministry of Labour, Welfare and Social Services (MLWSS) but also shorter work experience in school-based programmes (technological education) under the Ministry of Education and programmes for adults.

The economics of apprenticeship

Clearly, good apprenticeships, leading to good labour market outcomes for apprentices, require full employer involvement. Employers will normally provide apprenticeships when they believe that the benefits outweigh or are at least equal to the costs. The benefits emerge first, during the apprenticeship, through the productive contribution of apprentices, and second, after the end of the programme through recruitment of the most able apprentices, lower staff turnover and higher productivity. Employers can reap large benefits from this recruitment because labour markets are imperfect, and the full productive value of the graduate apprentice will therefore not be fully compensated in wages (e.g. Franz and Soskice, 1994).

Employers may be unaware of potential benefits

In countries where apprenticeship is less common, including Israel, employers may be more reluctant to invest in apprenticeships. While the costs of having apprentices are obvious, the benefits are less clear. Understanding those short and longer-term benefits and working out how best to realise them will take time. In Israel, an effective apprenticeship system should therefore not only lead to good benefits for employers, but also these benefits should be transparent to them.

Compulsory military service means that youth apprentices cannot usually be directly recruited as employees

In Israel, most young people serve in the army for 2-3 years after completing upper-secondary education. Employers providing training to these young people are therefore unable to recruit them immediately after the end of the apprenticeship programme, unless they are exempt from military service. While some apprenticeship graduates may eventually get back to the employer that provided their apprenticeship, many will change their careers or move to another employer. (Ben Rabi et al., forthcoming) argue that this factor discourages Israeli employers from engaging more fully in youth apprenticeship – it is just not that effective as a recruitment tool. So for Israeli employers to offer youth apprenticeship, they would normally have to see the return more immediately in terms of the work done by apprentices. An analysis of the costs and benefits of apprenticeship would help to estimate benefits accruing to employers in Israel in the current system. International experience shows that some apprenticeship systems can achieve this outcome through rapid training of apprentices, and by quickly using them in skilled roles, where the value of their contribution will be highest.

There is a risk apprentices are used solely as unskilled labour

All apprenticeship systems face the risk that apprentices might be exploited as unskilled labour. Using apprentices solely as unskilled labour requires little investment from employers but, if the apprentice wage is low, yields benefits associated with the productive unskilled work carried out by the apprentice. Simulations based on cost-benefit surveys show that Swiss employers could increase their net benefits by an average of EUR 22 000 per apprentice over the period of an apprenticeship if the apprentices performed only unskilled tasks while in the work place (Wolter and Ryan, 2011). Employers do not take advantage of this possibility in practice because apprenticeship regulations oblige employers to train – and this demonstrates the importance of such regulation. For example, in countries with strong apprenticeship systems (e.g. Switzerland and Norway) there is a curriculum defining skills apprentices should develop while in the work place (see for example curriculum for apprenticeship in electronics engineer in Switzerland (SEFRI, 2015).

Employers have to invest in training to be able to allocate apprentices to skilled tasks

Realising benefits from the skilled work of apprentices requires significant investment by the company (see Table 3.1). Apprentices need to be taught occupation-specific skills, which involves costs in terms of instruction time and equipment in addition to other costs.

Table 3.1. Costs and benefits associate with skilled and unskilled work of apprentices

|

Apprentices contribute to unskilled work |

Apprentices contribute to skilled work |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Costs |

Apprentice wage and other associated costs such as social security, etc. |

Apprentice wage and other associated costs such as social security, etc. |

|

Administrative costs |

Administrative costs |

|

|

|

Training equipment |

|

|

|

Wages of instructors/trainers |

|

|

Benefits |

Apprentice carry out productive work not requiring any additional training while in the workplace |

Apprentice carry out productive work while in the workplace less time devoted to training |

Source: Kuczera M. (2017), “Striking the right balance. Costs and benefits of apprenticeship”, Education Working Papers, No. 153, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/995fff01-en.

The Swiss model of apprenticeship has some relevance for Israel

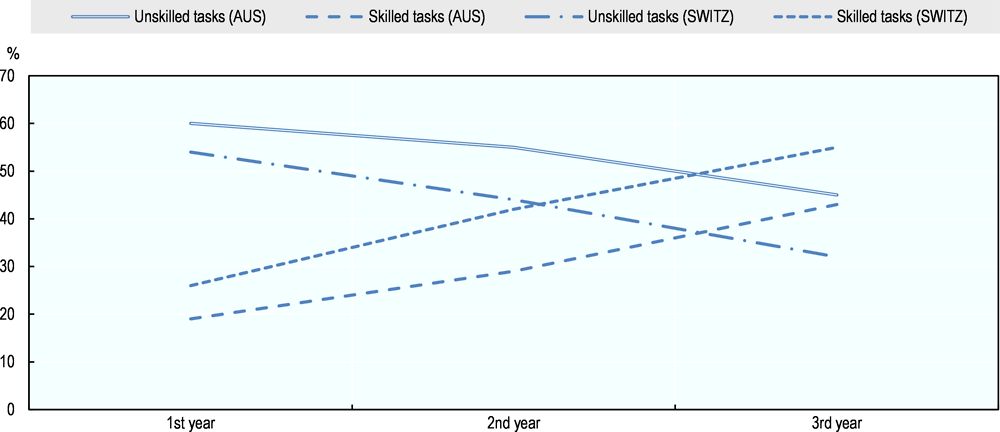

The Swiss model is most relevant to Israel, given national service for men in Switzerland, and other features of the Swiss labour market which make it less likely that graduate apprentices will continue with the employer that provided them with apprenticeship training. Evidence from Switzerland shows that employers who invest in apprenticeship training can recoup their investment if they rapidly train up and allocate apprentices to skilled tasks, since the skilled tasks yield the most value to the employer. As an illustration of this point, a recent study has shown that apprenticeship in Austria yields lower benefits to employers than in Switzerland. This is because of higher apprentice wages (relative to skilled worker wages) in Austria than in Switzerland, and to the fact that Austrian apprentices spend less time in productive tasks than their Swiss counterparts (see Figure 3.1). It shows that in Switzerland apprentices by their second year spend roughly equal amount of their work place time in skilled and unskilled tasks. In Austria, apprentices only reach the same point in their third year. Although Austrian apprentices are less rapidly fully productive, Austrian employers have incentives to provide apprenticeship because of government subsidies and longer-term recruitment benefits (Moretti et al., 2017).

Figure 3.1. Allocation of apprentices to skilled and unskilled work in Switzerland and Austria

Source: Adapted from Moretti, et al., (2017), “So similar and yet so different: A comparative analysis of a firm’s cost and benefits of apprenticeship training in Austria and Switzerland.”, IZA Discussion Paper, No. 11081, https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/izaizadps/dp11081.htm.

Policy option 3.1: Making apprenticeships attractive to employers

Apprenticeship yields benefits to employers through the productive work of apprentices and because it works as a recruitment tool. For youth apprenticeships, in Israel, many employers may not be able to realise long-term benefits associated with recruitment/retention of the most able apprentices, given that most of the young apprentices enter the IDF. But experience of other countries shows that apprenticeship, if carefully designed, can be beneficial to employers even in the short term, when apprentices are rapidly trained up so that they can be placed in skilled productive work. This implies that Israel should pursue a targeted approach designed to support youth apprenticeship. Two policy options are:

Expand youth apprenticeships on prestigious occupations, including in public administration, to attract able students to the programme, as discussed in Chapter 2. Support employers in the provision of high-quality apprenticeships by providing services such as mentoring, training for apprentice instructors, help with administrative tasks, and support to employers working with disadvantaged youth.

Israel may also want to expand apprenticeships targeting young people who have completed their military service. Employers are obliged by law to pay the minimum wage to apprentices aged 18 and above which increases the cost of apprenticeship provision in this age group. This may represent a serious barrier to apprenticeship expansion.

Israel may review its wage setting in line with arrangements encountered in other countries to ensure apprenticeship is beneficial to employers. If this is implemented Israel may analyse the impact of lower wages on individual participation and if necessary, provide additional financial support to apprentices.

Policy arguments: The rationale for reform

Policy argument 1. The economics of youth apprenticeship suggest a twin-pronged approach to their development

Army service is a key determinant of the form of apprenticeship

First, given that most young people are required to serve in the army, youth apprenticeships will normally need to be designed so that apprentices rapidly provide net benefits to employers. This means that their wages need to be modest, while apprentices need to be made productive quickly. An evaluation of costs and benefits of apprenticeships would help to see whether any changes are necessary in the design of the Israeli apprenticeships to reach this objective. Second, for the social groups that are not required to serve in the army, employers providing apprenticeships can count on larger benefits including benefits associated with the productive work of apprentices during the programme but also benefits associated with the recruitment of the best apprenticeship graduates. This is not to suggest that youth apprenticeship should separate the social groups, which would have all kinds of adverse consequences, but it does suggest a realistic approach to the different requirements of the different sub-populations, recognising that the economic attractions of apprenticeship to employers will be variable.

Policy argument 2. The apprentice wage is the most important cost for employers

The wage is a key attraction of youth apprenticeships

In most countries apprentices receive a wage (see Table 3.3). This increases the attractiveness of the programme to young people, as no wage would be received in school-based education (Moretti et al., 2017). Young apprentices who receive a wage are treated like regular employees, they work and are paid for the work done. This can potentially increase their motivation to complete the programme and to carry out with diligence tasks in the work place.

In Israel the youth apprentice wage is relatively low

In Israel, youth apprentices receive around 35% of the skilled worker wage, with some companies paying apprentices more than the minimum required. While this is not very different from other countries, in absolute terms apprentices in Israel earn less than their counterparts in many other countries. This is partly because in Israel apprentices are paid only for their hours with employers while in most other countries the apprentice wage also covers time spent in school. Low apprenticeship wage may also reflect the fact that in Israel apprenticeship is for young people who dropped out from regular school programmes, and such provision is often challenging and thus more costly for employers. This is consistent with evidence from other countries, where the apprentice wage is often lower in programmes catering for disadvantaged youth (Kis, 2016).

Table 3.2. Minimum apprentice wages in youth apprenticeships

|

|

Do apprentices receive wages during the on-the-job period? |

Do apprentices receive wage during off-the-job period? |

What is the minimum wage the apprentice should receive? |

Who defines the minimum apprentice wage? |

Do employers pay social security contributions for an apprentice? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Austria |

Yes |

Yes |

On average 50% of the skilled worker wage |

Sectors at regional level |

Yes, but the state covers parts of the insurance costs |

|

Denmark |

Yes |

Yes |

30-70% of the skilled worker wage, depending on the year of the programme |

Sectors |

No |

|

Germany |

Yes |

Yes |

25-33% of the skilled worker wage, depending on the year of the programme |

Sectors at regional level |

Yes |

|

Israel |

Yes |

No |

For youth apprenticeship: 60% of the minimum wage or around 35% of the skilled worker wage1 |

The minimum apprentice wage is set by law |

Missing |

|

Norway |

Yes |

No : during the first two years provided fully in school Yes : in the last two years with an employer including one year of training |

30-80% of the skilled worker wage, depending on the year of the programme |

Sectors at national level |

Yes |

|

Sweden |

No |

No |

- |

- |

- |

|

Switzerland |

Yes |

Yes |

On average 20% of the skilled worker wage, depending on the year of the programme |

Individual company but employer/ professional associations provide recommendations. As a result apprentice wage varies by sector. |

Yes |

Note: Apprentice wages can vary largely across sectors and tend to increase over the duration of apprenticeship programme. The apprentice wage in Israel as a share of skilled worker wage was estimated assuming the minimum wage represents 60% of the skilled worker. According to the Income Survey 2011 the average monthly wage of a skilled worker was NIS 6 931, as compared to the minimum wage of NIS 4 100 (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2015).

Source: Kuczera, M. (2017), “Striking the right balance: Costs and benefits of apprenticeship”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 153, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/995fff01-en.

Apprentices of different ages have different wage expectations

The reservation wage (what the potential apprentice would be willing to work for) depends both on environmental factors such as labour market tightness, and individual characteristics such as ability and age. Younger people have lower reservation wages because their immediate needs are low if they still live with their parents, because they expect to recoup their investment in apprenticeship over their lifetime, and because the usual alternative is a school-based programme that offers no wage. By contrast, older apprentices often have families to support, and the alternative to apprenticeship is often a salaried job. In many countries the minimum apprenticeship wage does not depend on age, but for the reasons explained above employers often pay higher wages to older apprentices. In the Netherlands, where two-thirds of apprentices were in employment prior to starting an apprenticeship (most being young adults) three-quarters earn more than the national minimum wage (Christoffels, Cuppen, and Vrielink, 2016). In Switzerland, where the apprentice wage increases over the course of a programme, employers often pay adult apprentices the equivalent of the apprentice wage in the last year of training - about 72% of the median wage of an unqualified worker (Mühlemann, forthcoming).

In Israel apprentice over 18 must receive at least the national minimum wage

In Israel, employers are obliged by law to pay at least the national minimum wage to apprentices over 18. But, unlike many other countries Israeli apprentices 18 and above do not receive the pay while in college. Overall, and even though the wage does not cover the classroom period, the provision of apprenticeship to adults in Israel is expensive to employers in comparison to other countries, and the apprentice salary accounts for a large share of this cost. This might represent a drag on the expansion of apprenticeships.

In many countries apprentice wages are often determined sectorally

Costs and benefits of apprenticeship provision differ largely across sectors (Kuczera, 2017). For this reason in many countries apprenticeship wages are negotiated at the sectoral level. In many other countries, regular worker and apprentice salaries are negotiated by individual sectors (see Table 3.2).

Table 3.3. How the minimum apprentice wage is determined

|

|

Level at which the minimum apprentice wage is determined |

|---|---|

|

Australia |

Sectors at national and regional level. In some cases it is up to individual companies |

|

Austria |

Sectors at regional level |

|

Denmark |

Sectors |

|

England (UK) |

National |

|

Germany |

Sectors at regional level |

|

Netherlands |

Sectors |

|

Norway |

Sectors at national level |

|

Scotland |

National |

|

Switzerland |

Unregulated but in practice sectoral/industry bodies provide recommendations on the wage level that are observed by individual employers |

Source: Adapted from Kuczera, M. (2017), “Striking the right balance: Costs and benefits of apprenticeship”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 153, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/995fff01-en.

Policy argument 3. Several additional measures support apprenticeship

Regulations ensure apprentices receive good quality training but increase immediate employer cost

As argued earlier, while the apprentice wage should remain low enough to make apprenticeship attractive to employers, regulation is necessary to avoid the risk that apprentices will be used just as cheap labour. Such regulation should ensure that apprentices have the opportunity to develop a wide range of skills with the employer, and that they receive instruction and carry out skilled productive work, in addition to unskilled work. Israel has in place detailed regulations regarding the work-based learning part, including its content, competences of mentors working with apprentices in companies, and external supervision (Ben Rabi et al., forthcoming). This is a strong point of the Israeli apprenticeship system. But (Ben Rabi et al., forthcoming) point out that some of the existing regulations are not respected by employers because of budgetary constraints. For example, mentors working with apprentices in companies do not receive much training because of the high cost of such a training to employers. Providing training for mentors is particularly challenging for small employers.

Government can support employers by making employers better at training

One way of promoting apprenticeship by governments is to assist employers with providing good quality training and meeting regulatory requirements. This includes measures helping employers with the training of mentors, administrative tasks, and support employers who offer apprenticeships to disadvantaged young people. The objective is to maintain effective regulation in a positive way, by helping employers to comply with regulation, often in their own interest. These measures might be particularly helpful to small companies as they often have limited training experience and cannot comply with all the requirements. (see Box 3.1 on how countries support training of apprentice supervisors in the work place).

Box 3.1. Country examples of training for apprentice supervisors in the workplace

Germany: Those who supervise apprentices (typically holders of an upper-secondary qualification) have to pass the trainer aptitude exam, while those with an advanced VET qualification (e.g. master craftsperson) already fulfil the requirements, since master craftsperson programmes include this element (BIBB, 2009a).

In the trainer aptitude exam (Ausbildereignungsprüfung), candidates demonstrate their ability to assess educational needs, plan and prepare training, assist in the recruitment of apprentices, deliver training and prepare the apprentice to complete their training (BIBB, 2009a). To prepare for the exam, candidates typically attend “Training for trainer” courses (Ausbildung für Ausbilder). These preparatory courses are provided by the chambers of commerce and normally last for 115 hours (BIBB, 2009b). Average costs are EUR 180 for the exam and up to EUR 420 for the preparatory course. Candidates may be supported by their employers and can seek financial support from the state through schemes such as the training credit (Bildungsprämie) (TA Bildungszentrum, 2015).

Norway: Optional training is offered to employees involved in supervising apprentices. Some counties provide the training themselves, others ask schools or training offices (which are owned by companies collectively) to ensure its provision. The courses are free to participants since counties provide the course, learning material, subsistence and travel expenses. However, the firm is responsible for the supervisor’s pay during the course. Typically, the duration of the training is two days (or four half days) per year. Often there is a time interval between each training session, so that supervisors may practice what they have learnt and prepare a report, which is then presented at the next session. National guidelines, developed in co-operation with VET teacher-training institutions, are available on the Internet and can be adapted to local needs. The form of training typically includes role-play and practice. Supervisors learn to cover the curriculum, complete evaluation procedures and administrative forms, prepare a training plan for apprentices, and follow through the plan.

Switzerland: Apprentice supervisors are required to complete a targeted training programme, in addition to having a vocational qualification and at least two years of relevant work experience. Cantons are in charge of training, either by offering courses themselves or by delegating them to accredited training providers. They also subsidise these courses, which are offered in two formats leading to different qualifications (40 hour course costing Swiss Franc [SFR] 600 or 100 hour course costing SFR 2 300). The training courses cover information about the Swiss VET system, vocational pedagogy and how to handle potential problems that may arise with young people (e.g. drugs, alcohol).

Sources: ABB (n.d.), “Lehraufsicht”, Amt für Berufsbildung und Berufsberatung, Thurgau, Amt für Berufsbildung und Berufsberatung, www.abb.tg.ch/xml_63/internet/de/application/d10079/d9739/f9309.cfm (accessed 26 February 2016); SBFI (n.d.), “Berufsbildungsverantwortliche”, Staatssekretariat für Bildung, Forschung und Innovation, www.sbfi.admin.ch/berufsbildung/ (accessed 26 February 2016). BIBB (2009a), Ausbilder-Eignungsverordnung Vom 21 January 2009, Bundesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2009 Teil I Nr. 5, www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/ausbilder_eignungsverordnung.pdf; BIBB (2009b), “Empfehlungen des Hauptausschusses des Bundesinstituts für Berufsbildung zum Rahmenplan für die Ausbildung der Ausbilder und Ausbilderinnen”, www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/HA135.pdf; TA Bildungszentrum (2015), “Ausbildungseignungsprüfung IHK (AEVO)”, www.ta.de/ausbildereignungspruefung-ihk-aevo.html; Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (2009), personal communication (22 January 2009).

Policy argument 4. Short ‘taster’ work-based programmes are less burdensome but also lead to fewer benefits

Chapter 2 recommends mandatory work placements in technological programmes. Some short work placements – often weeks or months - aim to familiarise students with the work environment and an occupation rather than to teach a student a full range of skills required by an occupation. The costs involved in offering work placements are different from those in apprenticeships, with often a smaller administrative burden, no wage costs and fewer demands on the time of the firm’s employees. For employers the expected benefits are also different from apprenticeships. Students typically do not perform much productive work during their placements. Yet, employers providing shorter work placements may benefit from getting to know potential recruits, and they may want to interest potential future recruits in a given occupation or a firm. Participating firms may also benefit indirectly, through contact with local vocational schools, and communicating their skills needs to schools.

Policy option 3.2: Sharing cost of training among employers

Low productivity and skills shortages in several economic sectors are holding back Israel's economic growth. While employers would collectively benefit from more workforce training, it is not always in the individual interest of an employer to offer training. To overcome this barrier, and create the step change necessary to improve the supply of skills, Israel may wish to support the establishment of sectoral training levies initiated by social partners, which have been used successfully in some European countries.

Policy arguments: The rationale for reform

Policy argument 1. Financial incentives aim to increase the provision of training

Financial incentives are justified through the collective benefits of training

Financial incentives for companies to train, funded through general public expenditure, are justified when such training leads to positive 'externalities'. Externalities are created when work-based learning yields benefits to employers other than the employer who provided the apprenticeship (e.g. by improving the skills of potential recruits) and to the whole society (by increasing the overall level of human capital). These externalities mean that, in the absence of subsidy, employers would provide insufficient training. This is because although society collectively benefits from this training, the individual employers making the training decision only benefit in a more limited way. Sometimes, these externality benefits fall mainly to employers in the same economic sector, who benefit collectively from a better trained workforce. In this case, an alternative approach is to use training levies.

Financial incentives should be carefully evaluated

Given evidence that programmes with work-based learning represent a cost-effective way of developing workforce skills and transitioning young people smoothly from school to work, many governments support provision of work placements through a range of incentives. See Table 3.2 for a description of some country schemes. Overall, the evidence is that these incentives usually have a modest impact, taking into account deadweight loss (training that would be provided even without the subsidy) and displacement effects (replacing unsubsidised training with other forms of training that qualify for subsidy but are otherwise quite similar). These initiatives should therefore be carefully evaluated to avoid inefficiencies.

Table 3.4. Financial incentives to companies providing apprenticeships

|

|

Tax incentives* |

Subsidy |

Levy scheme |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Australia |

Tax incentives depend on the qualifications the programme leads to. |

Subsidy in specific cases e.g. person being trained has a disability. |

No |

|

Austria |

Tax incentives abolished in 2008 and replaced by targeted subsidies. |

From 2008 targeted subsidies, have been available per apprentice (the amount depends on the year of apprenticeship), for additional training, for training of instructors, for apprentices excelling on final assessment, for measures supporting apprentices with learning difficulties, and equal access for women to apprenticeships. |

A levy fund in the construction sector covering all regions and a levy fund in the electro-metallic industry of one province (Vorarlberg), both negotiated by employers and trade unions. |

|

Belgium – Flanders |

Payroll tax deduction. |

Direct subsidy depending on the number of apprentices and programme duration. |

No |

|

Germany |

No |

No |

In the construction sector. Negotiated by employers and trade unions. |

|

Netherlands |

Tax exemptions (abolished in 2014). |

From 2014, subsidy to employers up to EUR 2 700 per apprentice per year (depending on the duration of the apprenticeship). |

No |

|

Norway |

No |

Direct subsidy depending on the number of training places, equity role (e.g. to encourage enterprises to take up disadvantaged trainees), and sector. |

No |

|

Switzerland |

No |

No |

All companies within certain economic sectors can decide to contribute to a corresponding vocational fund (to develop training, organise courses and qualifications procedures, promote specific occupations). |

Note: Tax incentives reduce either the tax base or the tax due. They include: (a) tax allowances (deducted from the gross income to arrive at the taxable income); (b) tax exemptions (some income is exempted from the tax base); (c) tax credits (sums deducted from the tax due); (d) tax relief (some classes of taxpayers or activities benefit from lower rates); (e) tax deferrals (postponement of tax payments).

Source: Adapted from Kuczera, M. (2017), “Striking the right balance: Costs and benefits of apprenticeship”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 153, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/995fff01-en.

Policy argument 2. Sometimes employers share the cost of training

Employers have particular incentives to share the cost of training through levy schemes when the cost of apprenticeship training is high, the labour market is tight and it is difficult to find skilled employees on the external market, and when employers face a high risk that their fully trained employees will be poached by other employers. All these factors can now be identified in Israel.

Across countries training levies have diverse characteristics

Training levies involve a levy on a percentage of employer turnover or payroll, according to certain rules, which is then used to fund training. For example, in Denmark and France, all employers share the cost of apprenticeships through a training levy. In Austria, Germany and Switzerland, levies are collected by sectors. In the new national system in the United Kingdom, only larger employers contribute. The cost sharing among employers may be initiated by the government [e.g. France, England (United Kingdom)] or by employers themselves (e.g. Austria, Germany and Switzerland). See Box 3.2 for a description of the Swiss scheme. Employers tend to be more sceptical of levy schemes initiated by the government, often perceived by employers as a tax, and where companies have little control over how the money is used and spent (Müller and Behringer, 2012).

Box 3.2. Sectoral training levies in Switzerland

Professional organisations can request the Federal Council to set up a mandatory sectoral fund with all companies in the sector paying solidarity contributions for provision of vocational education and training (e.g. development of regulations, promotion of VET among young people, organisation of professional assessments, development of pedagogical and teaching materials). The contribution depends on the company payroll. In 2008 there were 13 such funds with 16% of Swiss companies participating (SEFRI, 2009). Currently, nearly 30 funds are in place (SEFRI, 2017). Companies contributing to these funds reported that role of the fund was to increase solidarity in sharing the cost of vocational education in the specific sector/industry. Participating companies more or less agreed that the funds fulfilled well their statutory obligations. An evaluation of the funds showed that setting up of these mandatory funds is easier in sectors/industries that are well organised, that the administrative cost of contributing to the fund incurred by the company should be as low as possible and that the use of funds should be transparent (SEFRI, 2009). A robust evaluation of the impact of the funds on apprenticeship provision and its outcomes has not been performed yet.

Source: SEFRI (2009), “Évaluation des fonds en faveur de la formation professionnelle.” www.sbfi.admin.ch/sbfi/fr/home/bildung/berufsbildungssteuerung-und--politik/berufsbildungsfinanzierung/fonds-en-faveur-de-la-formation-professionnelle-selon-art--60-lf/evaluation-des-fonds-en-faveur-de-la-formation-professionnelle.html.

SEFRI (2017), “Fonds en faveur de la formation professionnelle entrés en vigueur selon l’art. 60 LFPr”, www.sbfi.admin.ch/sbfi/fr/home/bildung/berufsbildungssteuerung-und--politik/berufsbildungsfinanzierung/fonds-en-faveur-de-la-formation-professionnelle-selon-art--60-lf/fonds-en-faveur-de-la-formation-professionnelle-entres-en-vigueu.html.

Employer commitment to sectoral levies can be high

Sectoral levies are driven by employers in industrial sectors where employers see collective advantages from pooling training efforts. They can foster a close relationship between training and employer-defined skills needs in the sector. However, such levies tend to be concentrated in sectors where employers are well organised and have a strong commitment to training (such as construction and engineering), so the capacity of sectoral arrangements to address skills weaknesses in other areas – for example retail and other service industries, is weaker. Sectoral funding may also neglect common core skills which are transferable across industries, and may be ill-adapted to regional needs (Ziderman, 2003; CEDEFOP, 2008).

How the cost of levy is distributed

Levies imply an extra cost for companies that may be absorbed by employers, passed on to customers through higher prices, or shifted on to workers and apprentices through lower wages. If there are many skilled workers willing to work for the company, even at a lower wage, the employer can shift the cost to the workers. If, however, companies struggle to find qualified labour, they may not be able to lower salaries.

Policy argument 3. In Israel employers may need to invest more in training to address skills shortages

There may be insufficient training on-the-job

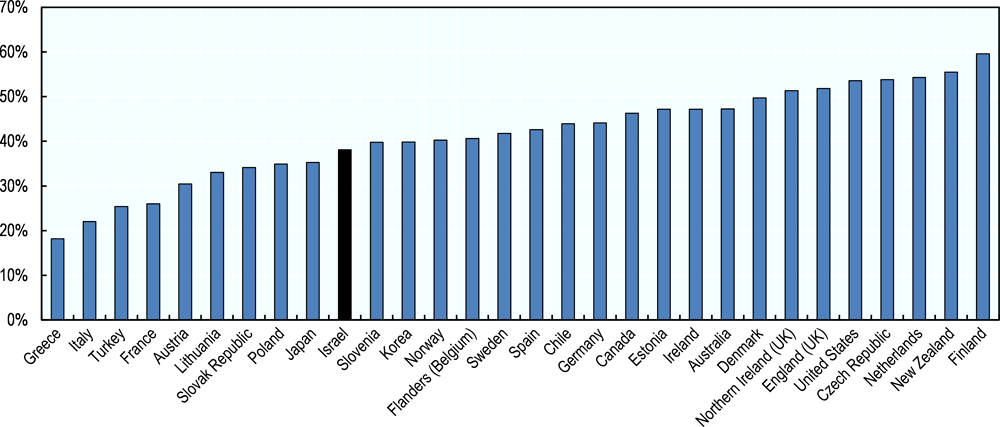

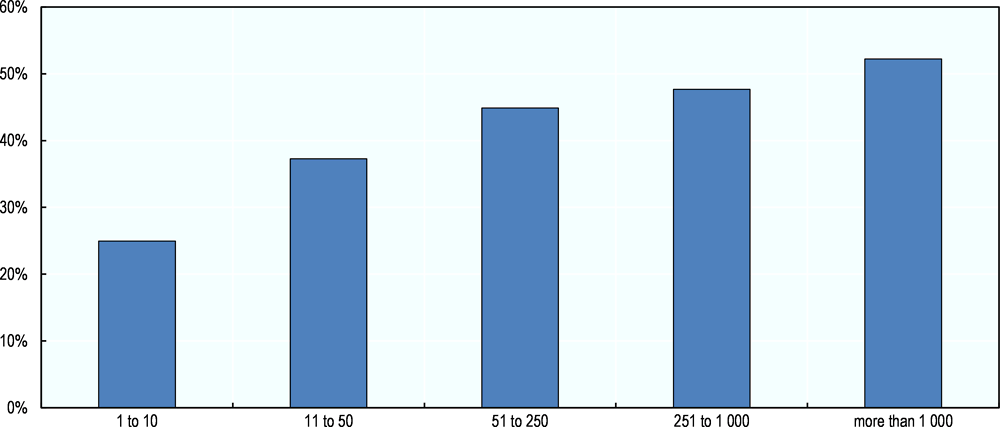

There is some evidence that in Israel there is insufficient on-the-job training. Just over one-third of 16-65 year-olds report that they have received some on-the-job training, compared with around half their counterparts in many OECD countries (see Figure 3.2). In the smaller firms, relatively few workers report that they receive on-the-job training (see Figure 3.3). One limitation of these data is that they do not record training intensity, i.e. how much on-the-job training is received by those who do receive it.

Figure 3.2. On-the-job training

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (Database 2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/site/piaac/publicdataandanalysis.htm.

Figure 3.3. Provision of training in Israel, by company size

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (Database 2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/site/piaac/publicdataandanalysis.htm.

Sectoral training levies might help to tackle skills shortages

In Israel, several factors, including severe skills gaps in some sectors, barriers to transition from school to skilled employment for some groups, poor productivity growth, and a high risk of poaching of fully trained young apprenticeship graduates provide an argument for a distribution of training costs among employers in the same sector. International evidence and experience suggest that training levies may represent an attractive means of addressing this challenge, given that they can support training both for students and the existing workforce. A sectoral approach with employers and trade unions initiating the creation of the fund may work best.

Sectoral training levies might be piloted in economic sectors with serious skills shortages

In Israel, it would make sense to pilot training levies in sectors where the majority of employers favour measures to improve skills supply. The principle is to back the voluntary commitment of a majority of employers to legislation that then mandates the levy on all the employers in the sector (possibly with exemptions for smaller employers). Having established the training fund through this measure, rules for expenditure of this fund can then be established. It might be used to support the training of the existing workforce, including apprentices. For example, in Denmark, the proceeds of the training levy are used to provide wages to apprentices during their time spent on off-the-job training. There is extensive European experience in these types of sectoral levy (CEDEFOP, 2008).

References

ABB (n.d.), “Lehraufsicht”, Amt für Berufsbildung und Berufsberatung, Thurgau, Amt für Berufsbildung und Berufsberatung, www.abb.tg.ch/xml_63/internet/de/application/d10079/d9739/f9309.cfm (accessed 26 February 2016).

Ben Rabi, D. et al. (forthcoming), Apprenticeship and Work-Based Learning in Israel. Background Report for Israel Project: Aiming High – Review of Apprenticeship.

BIBB (2009a), Ausbilder-Eignungsverordnung Vom 21 January 2009, Bundesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2009 Teil I Nr. 5, www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/ausbilder_eignungsverordnung.pdf.

BIBB (2009b), “Empfehlungen des Hauptausschusses des Bundesinstituts für Berufsbildung zum Rahmenplan für die Ausbildung der Ausbilder und Ausbilderinnen”, www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/HA135.pdf.

Christoffels, I., J. Cuppen and S. Vrielink (2016), Verzameling notities over de daling van de bbl en praktijkleren - Rapport - Rijksoverheid.nl, Rapport, ECBO, MOOZ, www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2016/10/18/verzameling-notities-over-de-daling-van-de-bbl-en-praktijkleren.

CEDEFOP (2008), “Sectoral training funds in Europe”, European Center for the Development of Vocational Training Panorama Series, No.156, Luxembourg.

Central Bureau of Statistics (2015), “Tables from Publication ‘Income Survey 2011. Gross Income per Employee, by Occupation (1994 Classification) and Sex, Table 20” www.cbs.gov.il/reader/cw_usr_view_SHTML?ID=570.

Franz, W. and D. Soskice (1994), “The German apprenticeship system”, Discussion Paper, No. 11 Center for International Labor Economics, University of Konstanz, www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/92436/1/720918545.pdf.

Kis, V. (2016), "Work-based learning for youth at risk: Getting employers on board", OECD Education Working Papers, No. 150, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5e122a91-en.

Kuczera, M. (2017), "Incentives for apprenticeship", OECD Education Working Papers, No. 152, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/55bb556d-en.

Moretti, L., et al. (2017), “So similar and yet so different: A comparative analysis of a firm’s cost and benefits of apprenticeship training in Austria and Switzerland”, IZA Discussion Paper, No. 11081, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/izaizadps/dp11081.htm.

Mühlemann S. (forthcoming), “Apprenticeships training for adults: theoretical considerations and empirical evidence for selected OECD members”.

Mühlemann, S. (2016), "The Cost and Benefits of Work-based Learning", OECD Education Working Papers, No. 143, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlpl4s6g0zv-en.

Müller, N. and F. Behringer (2012), “Subsidies and levies as policy instruments to encourage employer-provided training”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 80, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k97b083v1vb-en.

OECD (2018), OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (Database 2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/site/piaac/publicdataandanalysis.htm.

Ryan, P., et al. (2013), “Apprentice pay in Britain, Germany and Switzerland: Institutions, market forces and market power”, European Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol.19/3, pp. 201-20, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680113494155.

SBFI (n.d.), “Berufsbildungsverantwortliche”, Staatssekretariat für Bildung, Forschung und Innovation, www.sbfi.admin.ch/berufsbildung/ (accessed 26 February 2016).

SEFRI (2015), « Plan de formation relatif à l'ordonnance du SEFRI sur la formation professionnelle initiale de, Electronicienne CFC / Electronicien CFC » , Version 2.0 du 9 novembre 2015, numéro de la profession 46505, www.swissmechanic.ch/documents/ET_Plan_de_formation_V20_151216.pdf.

SEFRI (2009), “Évaluation des fonds en faveur de la formation professionnelle”, www.sbfi.admin.ch/sbfi/fr/home/bildung/berufsbildungssteuerung-und--politik/berufsbildungsfinanzierung/fonds-en-faveur-de-la-formation-professionnelle-selon-art--60-lf/evaluation-des-fonds-en-faveur-de-la-formation-professionnelle.html (accessed 25 July 2017).

SEFRI (2017), “Fonds en faveur de la formation professionnelle entrés en vigueur selon l’art. 60 LFPr”, www.sbfi.admin.ch/sbfi/fr/home/bildung/berufsbildungssteuerung-und--politik/berufsbildungsfinanzierung/fonds-en-faveur-de-la-formation-professionnelle-selon-art--60-lf/fonds-en-faveur-de-la-formation-professionnelle-entres-en-vigueu.html.

TA Bildungszentrum (2015), “Ausbildungseignungsprüfung IHK (AEVO)”, www.ta.de/ausbildereignungspruefung-ihk-aevo.html.

Wolter, S. and P. Ryan (2011), Apprenticeship Handbook of Economics of Education, Ed. by R. Hanushek, S. Machin, L. Woessmann, Vol. 3, Elsevier, North-Holland.

Ziderman, A. (2003), “Financing vocational training to meet policy objectives: Sub-Saharan Africa”, African Region Human Development Working Paper Series, The World Bank, Washington, DC.