The chapter describes the food security policy instruments used in India, with a focus on the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS). Scenarios developed for the purposes of this report examine what would happen over the medium term if the TPDS remains in place compared to a situation where the public grain distribution is gradually and partially replaced by cash transfers. The analysis shows that significant benefits could accrue, across many dimensions of policy performance. As India’s TPDS is also used to support producer incomes, special attention is given to what reforms are needed to ensure producer incomes do not suffer as a result of policy moves to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of the TPDS.

Agricultural Policies in India

Chapter 4. Making India food secure while ensuring farmer income security in an inclusive and sustainable manner

Abstract

4.1. Introduction

India is the world’s second most populous nation, home to 18% of the world’s population in 2015 (World Bank, 2017a). As a developing country, it also contains a significant proportion of the world’s poor and undernourished. The FAO estimates that in India alone 191 million people were undernourished in 2014-16 – representing 24% of the total number of undernourished people worldwide. For this reason, addressing food security represents an enormous challenge for the Indian Government.

Food security is a multidimensional problem requiring policy interventions across a range of different areas. According to the FAO definition agreed at the 1996 World Food Summit and expanded upon at the 2001 Summit, food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life. This definition suggest that people will only be food secure when sufficient food is available, they have access to it, and it is well utilised. The fourth requirement is that those three dimensions are stable over time.

In response to the food insecurity challenge that India faces, the Indian Government has in place a number of programmes and policies that seek to ameliorate the problem. Some of these programmes are vast and supported by a large governmental infrastructure that purchases food grains, mainly wheat and rice, from producers and subsequently supplies it at low cost to vulnerable households and individuals (Chapter 3). It is unquestioned that in implementing these programmes there have been successes and the Indian Government has been able to make inroads into addressing the issues of food security faced by a large number of its population. However, as with all government programmes, questions remain whether more could be done, or given tight and scarce fiscal resources, whether what is being done can be delivered in a more efficient and effective manner. In this light, some of the current programmes used have not been without criticism. Various studies have argued that changes could be made to improve the effectiveness of the programmes in achieving government’s legitimate objective of addressing food insecurity, and at the same time, there are options which would help to reduce the costs of food security related interventions. With the high cost of current programmes and the unaddressed large size of the problem, exploring such ‘win-win’ outcomes is worthwhile.

This chapter takes a look at the major agriculture-based food security programme used in India – that of the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) – and explores its impacts on agricultural production, markets and food security. It also explores the effects of possible reforms and alternatives to test whether there are other approaches or adjustments that may help the Indian Government to improve its efforts to address food security while providing a framework for the market to also play its role through both improving consumer access to food and enhancing producer incomes.

The rest of the chapter is structured as follows. In section 4.2 a brief overview of India’s current food security situation is provided. Section 4.3 details the current major agriculture-based food security programmes. Their effectiveness is discussed in section 4.4. Alternative policies are then assessed in section 4.5 in terms of their impacts on markets and food security as measured by rates of undernourishment. Alternatives to address issues of producer incomes are discussed in section 4.6.

4.2. Overview of food security in India

India’s share of the world’s undernourished population exceeds its share of the world’s population indicating that it houses a disproportionate number of the world’s poor. Since the early 1990s, the number of undernourished people in India has remained relatively stable – with only a reduction of 15 million in the number of undernourished between 1990-92 and 2014-16 (Figure 4.1). This relatively small change in the number of undernourished is due to strong population growth among the poor, with more significant changes seen in the proportion of the population who are undernourished – falling from around 24% in 1990-92 to 15% in 2014-16 (FAO, 2017).

Figure 4.1. Undernourishment in India

Source: FAO (2017).

Changes in the proportion of the population who are undernourished also point to a large share of households who are at risk of undernourishment. For example, between 2002-04 and 2008‑10 undernourishment rates increased significantly, offsetting past gains. This impact was partly driven by stronger food price rises over the period. Since then, levels of food insecurity have fallen again but the pace at which this is occurring in recent years is slower than that seen in the early 1990s.

Other indicators show mixed trends in food security. Rates of stunting (being short for a child’s age relative to population and demographic benchmarks) in children under 5 years of age point to a lack of food, nutrition or utilisation of food to a significant enough degree that it limits a child’s growth. Thus it shows the cumulative impact of food insecurity that may occur over time but which may not be fully captured in annual statistics of undernourishment. Rates of wasting (low weight for height) on the other hand, generally depict more acute episodes of food insecurity. Underweight estimates combine information about growth retardation and weight for height and thus point to the combined effect of both. While data for India is not frequent, and latest available estimates relate to 2006 (around the time of the spike seen in undernourishment figures), the indicators point to contradictory changes in food security. Rates of both stunting and underweight in children under 5 years of age fell between 1992 and 2006 by around 10 and 7 percentage points respectively (Figure 4.2). Rates of wasting, however, remained stable. These trends point to some general improvements for the population, but suggest that there remains a core disadvantaged group who are vulnerable to food insecurity and this has persisted over the period.

Figure 4.2. Wasting, stunting and underweight children in India

Source: FAO (2017).

There are also broader issues of malnutrition. India has both significant number of people that are undernourished (as shown above) and a significant number who are overweight and obese. Further, micronutrient deficiencies are high with, for example, 53% of women aged 15-49 and 22.7% of men aged 15-49 being anaemic in 2015-16 (International Institute for Population Sciences, 2017).

Exploring consumption patterns in the 2011-12 National Household Expenditure survey provides another lens to examine undernourishment. Due to the differences in the accounting of food availability (based on stated purchases as opposed to computed from national level food balance sheets as done by the FAO), the proportion of population that appears to be undernourished can differ significantly from the FAO estimates. There are numerous reasons for this – ranging from underreporting of food purchases to the significant difficulties associated with working out the calorie content of purchased foods and meals taken outside the home. As such, it is more useful to explore the distribution of undernourishment and its properties to gain a picture or how many households sit close to any undernourishment threshold. Given the issues in calculating undernourishment levels, two thresholds are explored – one which balances the numbers of undernourished in the survey approximately to the numbers calculated by the FAO, and one that accounts for household member characteristics and where they live.1

The distribution of calorie intake derived from the survey shows that a significant proportion of individuals have calorie consumption levels that are close to the thresholds. For example, approximately 16% of the population is situated between the two thresholds (Figure 4.3). The results suggest that at any given level of undernourishment, there are a significant amount of people who are at risk of undernourishment in India. This high number of people who lie close to the undernourishment thresholds, however, do not only pose risks for India but also offers it opportunities. Most notable, the risks relate to events that may push large numbers or people into undernourishment – such events have been seen in the past. In contrast, for policy makers opportunities exist in significantly reducing the number of undernourished people in India. The large share of the population close to the threshold suggests that the impact from improvements in food security policy performance is likely to have large payoffs in terms of improving food security.

Figure 4.3. The distribution of per person calorie intake in India

Source: OECD estimates based on NSS68.

4.3. Policy responses to food security

India's policies to increase food security emphasise the availability and access dimensions of food security. For availability, policies seek to guarantee adequate supply by incentivising production using multiple types of producer support (detailed in Chapter 3). Access to food is mostly addressed by offering food grains at affordable prices to the population. This section focuses on India's recently implemented National Food Security Act (NFSA), which aims to provide subsidised food grains to approximately two thirds of India's population. It also discusses the domestic and trade policies that have been employed in an attempt to guarantee the stability of supply and keep non-subsidised domestic food prices at low levels.

Evolution of the PDS – The National Food Security Act (2013)

India's food security policy has historically been centred on the physical distribution of subsidised grains. The principles of India's Public Distribution System (PDS) were introduced following the 1943 Bengal famine and the scheme has evolved considerably since (Government of India, 2017a).

At its inception, the PDS was designed as a general entitlement scheme for all consumers without a specific target. During those initial years, the PDS delivered food grains only to urban food-scarce areas. In 1992, the scheme was revamped to improve access of food grains to people in hilly, remote and inaccessible regions, where many of India's poor lived. This Revamped PDS scheme (RPDS) was then replaced by the Targeted PDS (TPDS) in 1997. Whereas the RPDS focused on all people in poor areas, the TPDS targeted the poor in all areas (Government of India, 2017a).

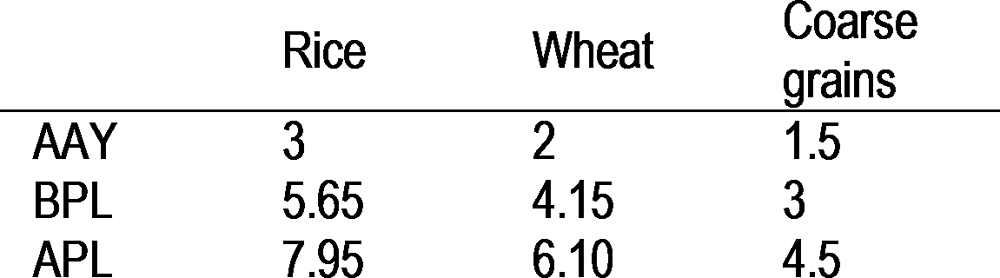

Under the TPDS, beneficiaries were divided into two categories: households below the poverty line (BPL) and households above the poverty line (APL). BPL households could buy rationed quantities of food and fuel (kerosene) at subsidised prices. APL households could also benefit from the scheme, but at higher prices. In 2000, the Government of India launched the Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) scheme, which was targeted at the poorest of the BPL families. Households in the AAY category could buy food (mainly wheat and rice) at highly subsidised prices.

In September 2013, the Parliament enacted the National Food Security Act (NFSA). The NFSA combines and expands various existing policies that are based on subsidised food distribution, namely the TPDS, the Wheat-Based Nutrition Programme and the Mid-Day Meal scheme. It also includes an existing conditional cash transfer scheme, which transfers a fixed cash amount per pregnancy to pregnant and lactating women, the Indira Gandhi Matritva Sahyog Yojana (Government of India, 2013).

The TPDS forms the largest component of the NFSA. Table 4.1 lists the major changes that were made to the TPDS under the NFSA. The NFSA extends the previous TPDS by covering a larger share of the population, lowering the issue prices and making the right to food a legal entitlement. Certain states and UTs implemented the NFSA faster than others, but by November 2016, all 36 Indian states and UTs had implemented the NFSA provisions (Government of India, 2016).

Under the NFSA, 75% of the rural population and 50% of the urban population are entitled to subsidised grains. Unlike under the previous TPDS, the coverage under the NFSA has been delinked from poverty estimates and the state-wise coverage has been determined by the Planning Commission (now NITI Aayog) on the basis of National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) data for 2011-12 on consumption expenditure. Accordingly, the categorisations of beneficiaries changed under the NFSA, which distinguishes between priority households and the AAY. The AAY households are the same as under the previous TPDS, while the priority households include all BPL households as well as some APL households. AAY households are entitled to 35 kg of grains per household per month. People belonging to the priority category are entitled to 5 kg of grains per person per month. Both groups can buy the food grains at the same issue prices, which were fixed at INR 3, INR 2 and INR 1 per kg, for rice, wheat and coarse grains, respectively. The issue price was fixed for 3 years from the start date of the Act, i.e. September 2013. However, the prices were never revised after three years and continue to be at the same levels even in September 2017. The Act prescribes that changes to the issue price should be made by the Central Government so that the issue price does not exceed the minimum support price.

In addition to the TPDS, food grains are also distributed under the Other Welfare Schemes (OWS). There are seven OWS in total, of which the Wheat-Based Nutrition Programme and the Mid-Day Meal scheme have been brought under the ambit of the NFSA (Government of India, 2013). The TPDS and OWS are operated under the joint responsibilities of the central and state governments. Figure 4.4 illustrates the process of procurement, offtake and distribution of food grains under the TPDS and OWS.

Table 4.1. Major changes made to the TPDS under the NFSA

|

Provision |

Previous TPDS (1997-2013)1 |

TPDS under NFSA (2013-current) |

|---|---|---|

|

Right to food |

Administrative order, no legal backing |

Legal right to food |

|

Categories of beneficiaries |

AAY, BPL, APL |

AAY and Priority |

|

Entitlements per categories |

AAY and BPL: 35 kg/household/month APL: 15-35 kg/household/month |

AAY: 35 kg/household/month Priority: 5 kg/person/month |

|

Prices of food grains (INR/kg) |

|

|

|

Coverage |

AAY: 25 million families BPL: 40.2 million families APL: 115 million families Total: 180.2 million families (or 180*5=901 million people) |

Up to 75% of rural population and 50% of urban population Total: 165.7 million households (or 813.5 million people) |

|

Identification of beneficiaries |

Centre: Releases state-wise estimates of population to be covered Creates criteria for identification Linked to poverty States: Identify eligible households |

Centre: Releases state-wise estimates of population to be covered Delinked with poverty States: Create criteria for identification Identify eligible households |

1 Numbers refer to most recent values. For example, the AAY scheme was created in 2000 and expanded in size over time.

Source: Adapted from Balani (2013).

Figure 4.4. Schematic representation of food grain procurement, offtake and distribution under the TPDS and OWS

There are two types of procurement systems: centralised and decentralised procurement. Under the centralised procurement system, the central government, through the Food Corporation of India (FCI), procures food grains (mostly wheat and rice) from farmers at the Minimum Support Price (MSP). The grains are physically procured by state agencies and they hold it on behalf of FCI until the time FCI needs them for moving from surplus to deficient states. In some other states, grains are procured under the decentralised procurement system. In this case, State Governments of India or its agencies procure, store and distribute the food grains. Any stocks in excess of those required for the state’s TPDS are handed over to the FCI (FCI, 2017). Decentralised procurement has been encouraged by the government in recent years as it targets non‑traditional states to procure the grains from local farmers, which enhances efficiency and reduces transit losses and costs (Government of India, 2015a).

The MSP is announced before planting starts and is set by the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs, mostly following the recommendations of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP). It takes into consideration several factors, including the cost of production and domestic and international price trends (Government of India, 2017b). The procurement system is open-ended since the government guarantees that it will buy all food grains offered by the farmers at the MSP, provided the grains meet certain quality specifications. In some years some states declare a bonus to be paid over and above the MSP for wheat and paddy.

The procured food grains are stored in storage facilities spread throughout the country. A distinction in accounting is made between operational stocks and food security stocks (FCI, 2017). Operational stocks are used for the distribution of grains through the TPDS and OWS. Food security stocks are kept to meet shortfalls in procurement and to smoothen any inter or intra year supply fluctuations.

The central government, through the FCI, issues the food grains for the TPDS and OWS to the state governments at the Central Issue Price (CIP), which is much lower than the price at which the centre procures the grains, the MSP. States are responsible for transporting the food grains to the beneficiaries. In the case of the TPDS, the grains are transported from the storage facilities to the fair price shops, where grains are then distributed at CIP or below. In case of the different OWS (Table 4.2), the method of distribution varies. Grains for Annapurna scheme are sold through the fair price shops, while all other OWS are managed by the respective departments of State governments. For example, under the Mid-Day Meal Scheme, a state department designated officer or a contractor appointed by them will offtake grains from the FCI or the state storage facilities and directly distribute it to the designated officials for distribution to the beneficiaries.

In certain states, consumers can buy TPDS grains at prices that are below the CIP as the states give further subsidy from state budgets. Indeed, states are allowed to extend the TPDS system as desired. The four most common ways in which the TPDS has been extended are: i) lowering the CIP price or even distributing the grains for free, ii) increasing the coverage, iii) increasing the entitlements, and iv) distributing other commodities in addition to the TPDS commodities (Saini and Gulati, 2015).

The FCI, on directions of the Government, occasionally releases food grains from its stocks in the domestic market under the Open Market Sales Scheme (OMSS) or exports them through state trading enterprises (STE) or through private exporters. Under the OMSS, the grains are sold at pre-determined prices, called the Minimum Issue Price. These types of sales in domestic market occur especially during the lean season and are meant to stabilise market prices.

Table 4.2. Overview of Other Welfare Schemes (OWS)

|

Name of Scheme |

Issue price |

Beneficiaries |

Scale of allotment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Mid-Day Meal Scheme |

Free of cost to States |

Students of Class I-VIII of Government and Government aided schools, Education Guarantee Scheme/Alternative and innovative Education Centres |

I-V Class: 100 gr/child/school/day VI-VIII Class: 150 gr/child/school/day |

|

Wheat-Based Nutrition Programme |

Wheat: INR 200/QtlRice: INR 300/Qtl |

Children below 6 years of age and expectant/lactating women |

Not given |

|

Annapurna |

Wheat: INR 415/QtlRice: INR 565/Qtl |

Senior citizens of 65 years of age or above who are not getting pension under the National Old Age Pension Scheme |

10 kg/month |

|

Welfare Institutions Scheme |

Wheat: INR 415/QtlRice: INR 565/Qtl |

Charitable Institutions such as beggar homes, nariniketans and other similar welfare institutions not covered under TPDS or under any other Welfare Schemes |

5 kg/cap/month |

|

SC/ST/OBC Hostels |

Wheat: INR 415/QtlRice: INR 565/Qtl |

Residents of the hostels having 2/3rd students belonging to SC/ST/OBC |

15 kg/resident/month |

|

Rajiv Gandhi Programme for Empowerment of Adolescent Girls-“SABLA” |

Wheat: INR 415/QtlRice: INR 565/Qtl |

Adolescent girls of 11-18 years |

6 kg/month |

|

Defence/Para-Military Forces |

At economic cost |

Food grains are allocated to Battalions State-wise |

-- |

|

Additional Allocations |

At MSP/CIP/Economic Cost of FCI/Open Sale rate |

Victims of natural calamities, additional requirement for festivals etc. |

Not fixed |

Note: Qtl stands for quintal (=100 kg).

Source: FCI (2017).

Domestic and trade policies to enhance food security

To achieve its national food security goals, India supplements its grain distribution programmes with domestic and trade policies. These domestic policies are mostly aimed at guaranteeing a large and stable supply of food crops by providing support to farmers. The most prominent types of producer support are price support and input subsidies. Chapter 3 provides a detailed description of all types of producer support and of the trade policies.

The government uses the MSP to increase agricultural production and productivity by offering a stable and remunerative price environment (Government of India, 2017c). Occasionally, the central government or states announce a bonus payable over and above the MSP to incentivise cultivation of certain commodities during specific periods. Even though MSPs are announced for 24 commodities2, procurement occurs mainly for rice and wheat and only from a limited set of states (Saini and Gulati, 2017).

The MSP for paddy rice and wheat increased significantly during the period 2007‑12 (Figure 4.5). During this period, India implemented the National Food Security Mission (NFSM), which was an intensive programme to increase the production of food grains by 20 million tonnes (comprising an additional 10 million tonnes of rice, 8 million tonnes of wheat and 2 million tonnes of pulses) in five years. Besides raising the MSP for paddy rice and wheat by almost 40% between 2007-08 and 2009-10, this programme also provided farmers with input subsidies and better technology (seeds). The NFSM is continued during the 12th five year plan (2012-17), with a stronger target for pulses (additional 4 million tonnes by 2017) and the inclusion of coarse grains (additional 3 million tonnes by 2017) on top of the additional 10 and 8 million tonnes of rice and wheat, respectively (Government of India, 2017d).

Figure 4.5. Minimum Support Price of paddy and wheat, marketing years 1990-91 until 2016-17

Source: Government of India (2017b)

Under NFSM, production of food grains increased by 42 million tonnes between 2007 and 2012, which was more than twice the target. As a result, India increased its rice exports and is now one of the largest rice exporters in the world. In addition, the strong production increases also led to an accumulation of large public stocks, which gave the government the confidence to introduce the NFSA in 2013 (Saini and Gulati, 2016b).

India's public stockholding policies are closely tied to its national food security objectives. Public stocks are built in order to make food grains available at reasonable prices, maintain buffer stocks as a measure of food security, and intervene in markets for price stabilisation (FCI, 2017). Stocking norms are set for each quarter and are specified for operational stocks (stocks for distribution under TPDS and OWS) and food security stocks (to meet shortfall in procurement)3. Unlike most countries, information related to publicly held stocks in India (stock levels, procurement targets, procurement levels, offtake, distribution volumes, MSP, distribution prices, costs, etc.) is publicly available.

Table 4.3. Buffer norms of food grains (million tonnes)

|

Operational stock |

Strategic reserve |

Grand total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

As on |

Rice |

Wheat |

Total |

Rice |

Wheat |

|

|

1st April |

11.58 |

4.46 |

16.04 |

3 |

2 |

21.04 |

|

1st July |

11.54 |

24.58 |

36.12 |

2 |

3 |

41.12 |

|

1st October |

8.25 |

17.52 |

25.77 |

3 |

2 |

30.77 |

|

1st January |

5.61 |

10.8 |

16.41 |

3 |

2 |

21.41 |

Note: The last revision of the buffer norms was done in July 2013.

Source: FCI (2017).

Figure 4.6. Evolution of publicly held stocks of wheat and rice in India, 2000-16

Source: RBI (2016).

Besides its involvement in domestic markets through farmer support policies, public stockholding policies and food grain distribution, the government also implemented other domestic policies to protect the interests of consumers and producers. The Essential Commodities Act, 1955 (ECA) aims to shield consumers from spikes in the prices of essential commodities by giving the central government powers to control the production, supply and distribution of these commodities. One of the implications of this Act is that States can impose limits on private stockholding, which has led to a marginalisation of private stocks (Kozicka et al., 2015). The Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) Model Act of 2003 seeks to ensure that farmers are not exploited by private traders to sell their produce at farm gate for very low prices by requiring farmers to sell their produce via auction at APMC mandi (wholesale markets) (discussed in more detail below).

India's agricultural trade policies are described in detail in Chapter 3. Export restrictions have been frequently used to support national food security objectives as they are implemented in order to keep domestic prices low and protected from international price shocks. The most notable export restrictive policies were the export bans of rice from October 2007 until September 2011 and of wheat between February 2007 and September 2011 (Saini and Gulati, 2017). The authors, however, show that these bans were only able to temporarily protect domestic prices from international price inflation and that domestic food prices tend to converge with world prices over the long run (Gulati and Saini, 2015).

4.4. Assessment of current food security policy instruments

As described in the previous section, India's main food security policy instrument is the NFSA. The assessment of current food security policy instruments hence focuses on analysing the effectiveness of the NFSA, and the TPDS in particular, in achieving its goal of improving the food security situation of the Indian population. In addition to examining the coverage and targeting of the NFSA, this section also reviews the efficiency of the programme and its impacts on markets.

Coverage and targeting of the NFSA

In recent years, availability of food has been less of a concern in India because of its strong growth in agricultural production and past productivity improvements. Economic access to food, on the other hand, is more problematic, especially in the context of making sure that food insecure people can afford to buy enough food in the open market to supplement what they receive from the TPDS in order to have a healthy and nutritious diet. In this context, issues have arisen over both coverage of the scheme and its targeting.

Coverage: population and products

The large coverage of the NFSA, which aims to reach 67% of the population, implies that exclusion errors in the TPDS are reduced. The low CIP prices, which have not been increased since 2013 and are in some states even lowered or set at zero (e.g. Tamil Nadu has free distribution), also contribute to making food grains more affordable to a larger group of people.

However, the redefinition of beneficiaries under the NFSA leads to lower entitlements for certain people compared to the old TPDS. Under the TPDS, BPL families were entitled to 35 kg of food grains per household per month, and under the NFSA, they receive 5 kg per capita, which means that a family of 5 members receives 25 kg per month under the NFSA compared to 35 kg under the old TPDS (Table 4.1). Even though the BPL individuals who are included as priority under NFSA benefit from lower CIPs, they are worse-off because of the lower entitlements (Mishra, 2013; Saini and Gulati, 2015). The other groups of beneficiaries, i.e. AAY and the included APL, are either as well off or better off under the NFSA. Because of the continuity of the entitlements, coverage and CIPs, the group of AAY beneficiaries remains unaffected under NFSA. For the eligible people in the APL group, they are better off under NFSA because of the lower CIPs.

Another issue raised by Saini and Gulati (2015) is that the number of beneficiaries under the NFSA 2013 is estimated using the 2011 Census data. The provisions in the Act fix these numbers up until the next Census data are released (Census enumeration is a decadal exercise). With a fixed number of beneficiaries, the distribution commitment of grains gets fixed as well. As a result, states where the population increased since 2011 will have either lower entitlements per person, or will cover a lower proportion of the population or both. Even though a large share of the population can purchase food grains at low prices under the NFSA, they still need to buy additional food grains in the open market in order to meet their daily requirements (NSSO, 2014). Figure 4.7 shows that in 2011-12, per capita consumption of rice was 6 kg per month in rural areas, of which more than 70% was obtained from other sources than the PDS. This share reached 90% for urban wheat consumption. These shares might have changed since the introduction of the NFSA, but even in the absence of more recent consumption data it is clear that part of rice and wheat consumption is purchased from other sources than the PDS. However, prices of rice and wheat have been rising steadily (Figure 4.8) in the open market and the benefit of receiving cheaper grains through the NFSA is hence partially offset by the higher prices that are paid in the open markets.

Figure 4.7. Per capita monthly consumption of rice and wheat from PDS and other sources in 2011-12, rural and urban India

Note: Excludes rice and wheat products.

Source: NSSO (2014).

Another critique of the TPDS is its focus on distributing rice and wheat, which ignores the changing food preferences of the Indian population and the importance of micro‑nutrients in people's diets. During the last decades, Indian diets have become more diversified with relatively more high value food products such as milk, egg, meat, fruits and vegetables. This trend towards diversification and higher consumption of more nutritious food items translates into higher expenditures on protein-rich and high-value food products. However, access to these food items and the possibility of higher quality diets is limited due to high food inflation rates (Figure 4.8) (Narayanan, 2015).

Figure 4.8. Monthly food, rice and wheat price inflation, April 2005-January 2017

Note: Price inflation is measured with the wholesale price index (WPI).

Source: RBI (2017).

Targeting: against income and need

The effectiveness of the TPDS in terms of targeting to poorer and undernourished households is an important element in understanding the effectiveness of the programme in reaching intended recipients. To explore these issues of targeting, consumption patterns from the 68th round of the NSS Household Expenditure Survey from 2011-12 were analysed. This survey has the advantage of separating TPDS and market consumption. However, as the survey took place in 2011-12 it is dated and so does not include the effects of the changes to the TPDS that were brought about by the NFSA. The effects of these changes to the TPDS on its targeting compared with 2011-12 are difficult to assess. On one hand, the greater entitlements and lower prices for some disadvantaged groups may have led to better targeting, but on the other hand, extending it to a larger share of the population is likely to mean that consumption by relatively better off and non-food insecure households has likely increased, leading to worse targeting. Despite these difficulties, due to the similarities in the schemes the information from the 2011-12 survey should still provide relevant insights into targeting. Information in the survey is used to assess the incidence of consumption from the TPDS across the household expenditure groups4 and undernourishment levels.

The results from the household survey suggest that while both TPDS programmes favour poorer households, there is significant consumption of rice and wheat from the TPDS by relatively better off households. For example, while households in the bottom two income deciles (those with average total household expenditures less than INR 3181 in 2011-12) receive close to 31% of all TPDS rice reported as consumed (in quantity terms), those in the top four deciles (including and above the 7th decile) consume 25% of total TPDS rice reported as consumed – the numbers for wheat are approximately the same. Equating this to implicit subsidy amounts (based on the average price of TPDS rice and wheat observed), around INR 4 269 million in 2011-12 (USD 85 million based on exchange rates at that time) per month went to households in the top four expenditure deciles in 2011-12. In terms of shares of total rice and wheat intake across income thresholds, consumption data reveals that households in lower income deciles are far more reliant on the TPDS as the source of their staples. For example, those households in the lowest deciles got around 45% of the rice they consumed from the TPDS and 38% of their wheat (Figure 4.9). These numbers, however, also suggest that a significant share of rice and wheat consumption is sourced from the open market or from their own production (home production accounts for 13% of rice consumption for the bottom two deciles and 16% of wheat consumption).

Figure 4.9. Consumption of TPDS rice and wheat across household expenditure deciles, 2011‑12

Source: OECD estimates.

Expenditure deciles provide one way to explore targeting. However, as the TPDS is seeking to ameliorate food insecurity, it is also worth exploring whether the rice and wheat is provided to food insecure individuals and households and disproportionally so. Using the two thresholds shown in Figure 4.3 – both absolute set at 1 600 kcal per day, and that based on characteristics of household members – a distribution of undernourishment can be calculated. For the household characteristics based threshold (varying by sex, age and location), undernourishment is present in the first 3 deciles with a significant number close to the threshold present in the 4th decile. For the absolute threshold (set at 1 600 kcal per person per day), undernourishment exists in the first two deciles, with a number at risk in the third decile.

Targeting of the TPDS on a food insecurity basis in 2011-12 was much less effective (Figure 4.10). Those in households who had the greatest depth of undernourishment only consumed around 32% of their total rice and around 20% of their wheat from the TPDS. The rest was sourced from the open market or home production. While the most undernourished and those at risk of undernourishment consume more of their rice and wheat from the TPDS, a significant share of rice and wheat by households who are not food insecure is sourced from the TPDS. For example, using the higher threshold of daily calorie needs, households in the top 2 deciles of calorie consumption – that is, they consume the highest levels above the threshold – consume around 22% of their total rice and 12% of their total wheat from the TPDS. These households had average per person calorie consumption around 1 000 kcal above the undernourishment thresholds.

Figure 4.10. Consumption of TPDS rice and wheat across depth of undernourishment deciles, 2011-12

Note: Household characteristic threshold represents that calculated based on the age and sex of household members. The Absolute threshold represents 1 600 kcal per day per person.

Source: OECD estimates.

Market impacts and inefficiencies of the NFSA

In addition to its design limitations which cannot guarantee access to high quality diets, the functioning of the NFSA programme creates market distortions that undermine the programme's food security objectives. The principal cause of these market distortions are the large procurement requirements of the programme. To fulfil its commitment to 67% of the population, around 61.4 million tonnes of food grains need to be procured under the NFSA (Saini and Gulati, 2015). This translates into around 30% of domestic production during the last 7 years (Figure 4.11). These percentages increase during times of domestic shortfalls given that the NFSA needs to maintain its procurement requirements. As a result, less food grain will be available for the domestic market which puts upwards pressure on prices.

The system of PDS/NFSA is also criticised for skewing production in favour of wheat and rice and away from other crops which might offer farmers higher and more stable farm incomes (Banerjee, 2011). These other crops could be high value crops or crops that are better suited to the agro-climatic conditions in the cultivation area. Rice is a water‑intensive crop and some of the main procurement states, such as Punjab and Haryana, are facing rapid groundwater depletion. Balani (2013) shows that rice cultivation in north-west India led to a decrease in the water table by 33 cm per year during 2002-08 (Box 2.7 in Chapter 2). This environmental stress leads to higher production costs and hence increases the cost of implementing NFSA.

In addition, the large government involvement in the rice and wheat markets discourages the private sector from participating in trading activities. This is especially the case in states that contribute heavily to the NFSA (Saini and Kozicka, 2014). The private sector is also crowded out from stockholding activities because of the large public stocks and limits to private stockholding5 under the ECA. As the private sector withdraws from trading and stockholding, the role of the government increases, which in turn adds pressure on the budget.

Finally, the fiscal costs of running the NFSA are very high and these costs are compounded by its various malfunctions (Kozicka et al., 2015; Saini and Kozicka, 2014). The food subsidy bill, which is the difference between the economic cost (sum of MSP, other procurement incidentals, and distribution costs) and the price at which food grains are issued to beneficiaries under the TPDS (i.e. the CIP), has increased six-fold over the last decade (Table 4.4). It is estimated that the food subsidy bill will be INR 1 453.4 billion in 2017-18, which is around 7% of the total central government’s Union Budget.

Figure 4.11. Procurement of rice and wheat as a percentage of production, 2000-15

Source: FCI (2017) for procurement data, RBI (2017) for production data.

Table 4.4. Food subsidy bill, 2007-18

|

Year |

INR billion |

% increase previous year |

% of total budget |

|

2007-08 |

313.28 |

30% |

4.4% |

|

2008-09 |

437.51 |

40% |

4.9% |

|

2009-10 |

584.43 |

34% |

7.8% |

|

2010-11 |

638.44 |

9% |

5.3% |

|

2011-12 |

728.22 |

14% |

5.6% |

|

2012-13 |

850.00 |

17% |

6.0% |

|

2013-14 |

920.00 |

8% |

5.9% |

|

2014-15 |

1176.71 |

28% |

7.1% |

|

2015-16 |

1394.19 |

18% |

7.8% |

|

2016-17 |

1351.73 |

-3% |

6.7% |

|

2017-18 |

1453.39 |

8% |

6.8% |

Note: Figures for 2016-17 are revised estimates; and for 2017-18 are budget estimates.

Source: PRS (2017).

The ballooning of the food subsidy bill is a result of the huge procurement volumes, the increased economic cost of buying food grains, and the stagnant CIP. Figure 4.12 illustrates how the gap between the economic cost of rice and wheat and their respective CIP's has been widening over time. Whereas the economic cost of rice has increased from INR 12.9 per kg in 2001-02 to INR 29.2 per kg in 2014-15 (an increase of 151%) and for wheat from INR 10.3/kg to INR 22.5/kg (or 134%) over the same period, the CIP's for the AAY have remained constant since 2002 and in fact have even reduced for BPL/priority beneficiaries (Table 4.1).

Figure 4.12. Economic cost of rice and wheat and CIP’s for the AAY, 2002-15

Note: The economic cost is calculated by the government as the sum of MSP, other procurement incidentals, and distribution costs.

Source: Government of India (2015b).

Apart from these direct fiscal costs there are also additional costs, which arise from leakages (illegal diversion of subsidised food grains from PDS to the open market) and wastage due to poor storage and transport facilities (Shreedhar et al., 2012). Even though there is no consensus on the exact numbers of the leakage, the scale is undoubtedly high as the lowest estimates for 2011-12 report leakage of 34.6% (Himanshu and Sen, 2013). The exact scale of storage losses is also unclear; a recent study estimates that the loss in storage is about 0.5% (Nanda et al., 2012).

4.5. Medium term market and food security impacts of implementing direct cash transfers

The above review shows that the NFSA is criticised because it is ineffective, inefficient and unsustainably expensive. In 2015, the High Level Committee on Restructuring of FCI (HLC) constituted by GOI, recommended to deeply restructure the system and among other reforms, to gradually replace the physical distribution of grains with cash transfers (Government of India, 2015b). Making the shift from the TPDS to direct benefit transfers (DBT) is possible under the NFSA because the Act itself allows for delivering cash instead of in-kind food delivery in case of non-supply6 and also promotes the introduction of direct cash transfers7.

This section explores the impacts of replacing the physical grain distribution under the traditional PDS with direct benefit transfers or DBT. DBT refers to the process of transferring an unconditional cash transfer amount, estimated using a pre-defined formula based on the monthly NFSA entitlement, into the Aadhaar-linked8 bank account of identified beneficiaries. This transfer is in lieu of NFSA’s physical grain entitlement and is made into the bank account of the female head of the family. There are certain pre‑requisites to the DBT: an updated list of beneficiaries with continuous efforts to remove exclusion and inclusion errors, a digital payment platform managed by the government, and a financial infrastructure that is inclusive of all its citizens.

This section first discusses the main advantages and disadvantages of the DBT and highlights some of its challenges. The second part of the section examines how partially and gradually replacing the PDS with DBT would influence India's markets and food security situation over the next ten years.

Comparing grain distribution with direct cash transfers

Cash transfers have several advantages over the PDS (Table 4.5). First, cash transfers have lower transaction and administrative costs and are easier to implement since they do not require huge amounts of food grains to be procured, stored, transported and distributed. They also offer beneficiaries expanded choices. Beneficiaries may use the cash to buy other food items, which might lead to more balanced or high quality diets – and in doing so better address food and nutrition security compared with the current focus on rice and wheat. Or they could spend it on health or education, or use it to relieve financial constraints – which have the potential to improve the utilisation and stability elements of food security. In addition, by replacing physical grain handling with a centrally controlled system of targeted cash transfers, the problems of high grain wastages, pilferages and leakages in the PDS can be addressed efficiently. Furthermore, the introduction of Aadhaar (Box 3.1 in Chapter 3) has the potential to reduce inclusion errors, with early studies showing that the mapping of digitised ration card data with Aadhaar numbers facilitates identifying and eliminating bogus ration cards (Saini et al., 2017).

However, beneficiaries risk being exposed to food price increases and volatility if the cash transfers are not adequately adjusted for inflation or if they are responsive to sudden dramatic price movements. In that case, beneficiaries could be worse off as they cannot buy the same amount of food as they receive under the TPDS. Additionally, the need to ensure availability of enough grains in the open market cannot be overemphasised. Beneficiaries with a high reliance on PDS grains (e.g. those located in remote areas or net-consumption states) may be subjected to exploitation by traders and retailers unless the government encourages participation from the private sector to ensure adequate amounts of grain in the market. Cash transfer programmes also require that people have access to banks or post offices and know how to use these services, which is a challenge especially in rural parts of the country (Box 4.1). Furthermore, when people receive cash instead of food from the fair price shops, they have to make at least two trips (one to the bank and one to the market) instead of one (to the fair price shop). There are also some problems with the TPDS which cannot be solved by switching to DBT. Most notably, exclusion errors are equally prone in both systems.

Box 4.1. How India's financial system could challenge the implementation of DBT

India's financial system is characterised by three main problems: low banking density, high financial illiteracy, and low financial inclusiveness. The banking density in a specific state can be calculated as the sum of the number of post offices, bank branches, ATMs and business correspondents in that state divided by the state’s population as per Census 20111. Based on this formula, India has on average 48 branches for every 100 000 people. The Union Territories of Chandigarh and Puducherry have banking densities of 128 and 72, respectively, which is one of the reasons why these two Union Territories were short‑listed for the pilot studies. States like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh have banking densities of 30, 34 and 37, respectively.

But even in states with relatively higher banking densities, there is still the problem of high levels of financial illiteracy which leads to widespread inconvenience in accessing and using banking services. This encourages the proliferation of middlemen who in return for a fee offer to withdraw money on behalf of the poor and illiterate beneficiaries, thereby reducing the delivered subsidy and making the transfer inadequate to support consumption.

In 2011, only 35% of Indian adults had a bank account (World Bank, 2017b). To address these low levels of financial inclusiveness, the government launched an initiative in August 2014 to “bank the unbanked”, which encouraged every adult to open a bank account. Between 15 October 2014 and 18 October 2017, the number of bank accounts increased from 44 to 305 million (PMJDY, 2017). While it is unclear how many of these accounts were for first-time account holders and how large and frequent the transactions were on these accounts, there is notable progress towards providing universal financial access to bank accounts.

However, mainstreaming the country’s poor and illiterate living in remote areas is a long haul and this makes the structure and depth of financial infrastructure one of the pillars which will determine the success of country’s drive towards DBT.

1. 1. Since the population has been growing at a higher rate than the number of banking facilities, these estimates of banking density are an overestimation.

Table 4.5. Main advantages and disadvantages of cash transfers compared to PDS

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|---|---|

|

|

Since 2015, three Union Territories of Chandigarh, Puducherry and Dadra and Nagar Haveli have introduced the Act in DBT mode as a pilot project. The experiences with DBT in the pilot studies show that the cash transfer system still faces several challenges. In the surveys that evaluate these pilots, some beneficiaries report that they did not receive the subsidy, received the subsidy with a delay or received an amount of subsidy that was not sufficient to buy the same amount of grains as they did under the PDS. There were also some practical issues with the banking system such as overcrowding of the branches and cash withdrawal problems. The reported problems in the pilot studies are serious issues which jeopardise people's food security situation. Before the DBT is rolled out in more states, it is imperative that these and other reported problems9 are addressed.

Over the medium term, the HLC recommends a gradual and partial replacement of the PDS by cash transfers. In particular, the HLC proposes that DBT are started in large cities with more than 1 million inhabitants; then extended to grain surplus states and finally the deficit states are given the option between cash or physical grain distribution (Government of India, 2015b). The last point, which refers to partially preserving the TPDS, has preference-based, access and political justifications. Results from a survey by Khera (2011) show that most respondents who live in states where the TPDS does not function well preferred cash transfers over the TPDS, while the opposite was true for respondents who lived in states where the TPDS did work well. In areas where people do not have access to markets to buy grains or to banks, distributing grain is more appropriate than providing cash. Finally, there are also socio-political forces dominant in certain areas that discourage the switch away from grains (Narayanan, 2015).

Medium term market and food security impacts of implementing direct cash transfers

Replacing physical grain distributions by direct cash transfers not only influences consumption and production patterns in the short run, but also affects markets in the longer run. The medium term impacts of gradually and partially replacing the TPDS with DBT are examined using the Aglink-Cosimo Model. This partial equilibrium model provides projections for the production, consumption, stocks, trade, and prices of 25 agricultural products in many individual countries (including India) and for regional aggregates. The model is employed to examine what would happen over the period 2017‑25 if the NFSA remains in place (baseline scenario) compared to a situation where the TPDS is gradually and partially replaced by DBT (DBT scenario).

One of the limitations of the model is that data are aggregated at the country level. When examining indicators related to food security, it is interesting to disaggregate the consumption trends by different population groups, organised by location and vulnerability status. While the model is not capable of disaggregating the data at the state‑level, it is possible to construct different demand groups, based on the NFSA obligations.

Demand groups

Four demand groups are constructed: urban low income, urban high income, rural low income and rural high income. The low income groups correspond to the population that is eligible for the TPDS and hence cover 75% of the rural population and 50% of the urban population. The demand groups are created using expenditure data (as a proxy for income) of the 68th round of the NSS (2011-12). The rural low income group is composed of the bottom 75% of the rural expenditure distribution and the urban low income group consists of the bottom 50% of the urban expenditure distribution. The remaining 25% of the rural population and 50% of the urban population form the non-poor (high income) groups.

Under the NFSA, entitlements vary between the priority households and the AAY households (see section 4.3). The AAY households are entitled to 35 kg food grains per month per household, while the priority households are entitled to 5 kg of food grains per person. In the model, the shares of AAY households in the rural and urban populations are assumed to stay constant, following the estimates from the NSS survey. This implies that the rest of the households in the low income groups are allocated to the priority group. Table 4.6 illustrates the share of the priority and AAY households in the total rural and urban population.

Table 4.6. Share of AAY and priority cardholder shares in the total rural and urban population and in rural and urban lower income groups

|

|

AAY |

Priority |

|---|---|---|

|

Share in rural population |

4.66% |

70.34% |

|

Share in urban population |

2.22% |

47.78% |

|

Share in rural low income population |

6.21% |

93.79% |

|

Share in urban low income population |

4.44% |

95.56% |

|

Consumption (kg/cap/month) |

7 |

5 |

Note: The average AAY household size was estimated to be 5 people.

Source: Own calculations based on the NSS, 68th round.

The baseline scenario and DBT scenario

Under the baseline scenario the TPDS food grains continue to be distributed during the period 2017-25 to 75% of the rural population and 50% of the urban population at the subsidised prices of INR 3 per kg for rice and INR 2 per kg for wheat in nominal terms. Even though India's TPDS also provides for distribution of coarse grains, the model simulations only consider wheat and rice since these are the main components of NFSA. The baseline scenario hence implies that India keeps procuring substantial amounts of rice and wheat from farmers at the MSP and maintains its large public stocks. The MSP is assumed to be constant in real terms and to stay marginally below the trend of the market prices10. It also assumes that current policies remain in place, such as the prohibition to hold private stocks, and that no new policies are implemented that could influence consumption, production, trade or prices.

The DBT scenario examines what would happen to markets (and to consumption in particular) if the physical grain distribution is gradually and partially replaced by DBT. The cash transfer is modelled to be introduced gradually over the course of five years (from 2017 until 2021) to account for the fact that not all states are equally ready to implement cash transfers (Saini et al., 2017). To incorporate a partial replacement, the DBT scenario assumes that 30% of the original TPDS is maintained in the rural areas beyond 2021.

Figure 4.13 illustrates how much rice and wheat from the TPDS were consumed by each of the demand groups from 2000 until 2016. The figure also demonstrates how this consumption is modelled under the DBT scenario from 2017 onwards. From 2000 until the introduction of the NFSA in 2013, the groups of beneficiaries were different than under the NFSA: this explains why there is non-zero consumption in all groups during that period. With the introduction of the NFSA in 2013, the high income groups were no longer eligible which has been assumed to have led to a decrease in consumption of subsidised grains by these two groups. In effect, it is assumed that the NFSA has been able to achieve its better targeting and the subsidised grain consumption in the high income groups drops to zero in 2016 with full implementation of the NFSA in all states and UTs. In contrast, consumption for low income groups increases with the NFSA, peaking in 2016.

From 2017 onwards, the TPDS in the low income groups is gradually replaced by DBT, which is modelled to be fully implemented by 2021 in the urban areas while in the rural areas 30% of the 2016 TPDS is assumed to remain to represent the need to maintain physical delivery of food to areas where the DBT system would not work either because of lack of market supply or the inability for participants to access the necessary financial services to receive the payment. The public stock level from 2021 onwards is hence assumed to remain constant at 7.5 million tonnes of rice and 3.9 million tonnes of wheat. Most of this public stock would serve the reduced version of the TPDS/NFSA, while 3 million tonnes would be earmarked as emergency stock.

Figure 4.13. Consumption of TPDS rice and wheat by the four demand groups

Source: OECD simulation results.

The monthly cash transfer in the DBT scenario is based on the formula that was applied in the pilot studies in the Union Territories of Chandigarh and Puducherry, where the food subsidy was calculated as 1.25*MSP-CIP. However, under the DBT scenario the cash transfer is slightly higher than the one used in the pilot studies because the MSP is multiplied by a factor 1.5 instead of 1.25. The 1.5 factor was selected following Saini et al. (2017) who report that the current cash transfer in the pilot studies did not allow beneficiaries to buy the same quantities and qualities of rice and wheat in the open market as they could obtain from the TPDS.

Only people in the rural and urban low income groups will receive cash transfers. The total cash transfer for each of these two low income demand groups, denoted by i, is calculated as:

where TPDSri,i refers to the total TPDS consumption of rice by low income group i under the baseline, and TPDSwt,i refers to the total TPDS consumption of wheat by low income group i under the baseline.

The DBT scenario also implements changes to the producer side, since the introduction of the DBT implies that the government no longer needs to buy and store large quantities of rice and wheat. Under the DBT scenario, it is assumed that regulatory reforms are introduced which close the gap between the international and domestic prices over the next 10 years. These regulatory reforms would be aimed at improving the functioning of markets and include reforms related to trade policies (e.g. reduce or eliminate the use of quantitative export restrictions), allowing private stockholding and improving infrastructure (roads and communication). In addition, there are no longer any procurement targets under the DBT scenario, but since 30% of the TPDS remains available in rural areas, the government continues to keep public stock. Farmers will still be able to sell their rice and wheat to the government at the MSP.

Consumer side impacts

Given that the objective of the NFSA is to ensure food security in India, the analysis focuses on the impacts on the consumers. In particular, several consumption‑related indicators are compared between the baseline and the DBT scenario: the evolution of total caloric intake (supply), the composition of diets, total per capita expenditures on food and the consumer prices of rice and wheat.

Food consumption in this analysis refers to food availability, which is calculated based on FAO's Food Balance Sheets. Figure 4.14 compares the evolution of total caloric intake (supply) for the 4 demand groups for the baseline and the DBT scenarios. The figure illustrates that the high income groups consume more calories per capita than the low income groups and that within the income groups, people in the rural areas on average consume more calories than people in the urban areas. Under the DBT scenario, people in the high income groups are projected to consume slightly fewer calories than under the baseline. One of the reasons behind this evolution might be their increased consumption of fruits and vegetables, which have a lower caloric content than other food items. Even though the caloric intake in the high income groups is projected to be slightly lower in the DBT scenario, it is still much higher than the intake in the low income groups.

People who were entitled to TPDS/NFSA food grains, that is, the low income groups, would be at least as well off in terms of per capita calorie consumption when they receive cash transfers instead of physical grain. The per capita calorie consumption in the rural low income group is projected to be higher under the DBT scenario than under the baseline. In the urban low income group, which is the group with the lowest calorie consumption, the average increase in calorie intake under the DBT scenario is less pronounced than in the rural low income group.

One of the main critiques of the NFSA is that it skews consumption towards rice and wheat. If the TPDS beneficiaries receive cash instead of physical food grains, they can choose which items to buy, which could lead to a more diverse and nutritious diet.

The simulations demonstrate that the composition of diets is projected to be more varied when consumers receive cash than when they can buy rice and wheat at subsidised prices (Figure 4.15). In 2025, per capita rice and wheat consumption will increase under both scenarios, but the increase is much more pronounced under the baseline. Compared to the urban low income group, the rural low income group will experience a smaller drop in wheat and rice consumption in the DBT scenario. This is explained by the fact that the DBT scenario assumes that 30% of the TPDS is still available to the rural low income group. In the DBT scenario, the relatively lower consumption growth in wheat and rice is compensated by a consumption increase of all other food items. For example, in the rural low income group under the baseline, per capita meat and dairy consumption in calorie terms is projected to increase by 14% and 23%, respectively, between 2016 and 2025. Under the DBT scenario, consumption growth in these food groups is projected to be around 10 percentage points higher, namely 23% and 33%, respectively.

Figure 4.14. Daily calorie intake (supply) per capita in four demand groups under baseline and DBT scenario

Note: Calorie intake is calculated based on total food availability, as reported in FAO’s Food Balance Sheets.

Source: OECD simulation results.

Figure 4.15. Calorie decomposition under baseline and DBT scenario, in rural and urban low income groups

Note: The category “other” contains all food commodities that are represented in FAO’s Food Balance Sheets.

Source: OECD simulation results.

The introduction of cash transfers combined with better functioning markets under the DBT scenario lead to relatively higher consumer prices for rice and wheat than under the baseline (Figure 4.16). As illustrated above, the consumption of rice and wheat will be relatively lower under the DBT scenario. On the producer side, farmers experience a lower demand from consumers but also from the government, which procures much less rice and wheat under the DBT scenario. In addition, the reforms implemented under the DBT scenario improve the working of markets, where the market price will rise above MSP. The MSP thus would no longer determine production decisions and farmers have more freedom in their choice of which crops to grow.

Figure 4.16. Consumer prices in real terms

Source: OECD simulation results.

The higher consumer prices for wheat and rice under the DBT scenario would not negatively affect the overall food security situation in the country. First, consumers receive cash which allows them to buy cheaper or higher quality food than wheat or rice. This is illustrated in Figure 4.17, which shows that the flexibility in consumption decisions in fact reduces total food expenditures for the low income groups, once the cash transfer is accounted for. Because they receive the cash transfer, the people in the low income groups have to use less of their own financial resources to buy food. This in turn means that more money is available to spend on other items, including higher quality food, but also education and health care. Second, the TPDS is not completely abolished under the DBT scenario and consumers who prefer to buy (or have less opportunity to buy food from the market) rice and wheat at subsidised prices are still able to do so. Finally, the higher consumer prices for rice and wheat coupled with better functioning markets imply that farmers who produce a marketable surplus receive higher prices for these commodities.

Figure 4.17. Per capita spending on food from own financial resources (net of cash transfer)

Note: Food expenditures are only represented for the food commodities included in Aglink-Cosimo (cereals, meat, oilseeds, sugar, dairy and fish). For the low income groups, the cash transfer is subtracted from the food expenditure to obtain the per capita spending on food from own financial resources.

Source: OECD simulation results.

Partially replacing the TPDS by DBT will result in much lower overall costs of procurement, stock carry over and distribution for the government (Figure 4.18). The cash transfer programme will of course require a substantial amount of government funds, which will depend on the way in which the government implements the DBT. If the cash transfer is calculated based on the formula used in the DBT scenario, then the total fiscal costs for the government are projected to amount to INR 1 778 billion by 2025, which is well below the INR 2 039 billion cost of the TPDS under the baseline. These amounts are purely budgetary based and do not incorporate all potential costs and savings that result from switching to DBT. In particular, they do not incorporate the costs of reforms, which could lower the savings in the short term but could create second round savings over the medium term when the effects of these reforms start to pay off. They also do not account for the fact that leakages will be substantially decreased under the DBT, which would increase the savings considerably.

The above estimated funds that are saved by partially switching to DBT can then be invested in other programmes that improve the food security situation in the country, such as investments in irrigation and market infrastructure, market reform and R&D to enhance agricultural productivity and mitigate the impacts of climate change. Reinvesting these savings into the agriculture sector will not only boost the sector’s growth rate but will also support the government’s drive to increase farmers' incomes and improve their profitability.

Figure 4.18. Composition of the cost of the food subsidy programme under baseline and DBT scenario

Note: Negative distribution costs occur when the revenues of selling rice and wheat are higher than the costs.

Source: OECD simulation results.

The move to DBT and accompanied investments in the market also brings with it other impacts for producers. Not only do open market prices increase, but there is also an increase in exports, meaning that producers, if equipped to participate better in markets, are likely to be able to take advantage of India’s relative comparative advantage in both crops and find alternative markets to compensate for the lower quantities sold on the domestic market (to the government).

Policy performance in the face of risk

The food security situation in India can be influenced by a myriad of factors, including temporary shortfalls in production due to bad weather, macroeconomic conditions, energy prices and policy interventions (Box 4.2). When designing a food security policy, it is crucial to examine how these types of shocks could affect the performance of the policy.

The performance of the current policies (baseline) and the DBT scenario is examined under the combination of two different types of risks: a period of high international prices combined with a domestic yield shock. The high international price period is modelled to start in 2017 and last for the entire projection period that is until 2025. This high price period is implemented by assuming that the GDP in the world excluding India will grow by an additional 1% each year. In addition, the shock scenario also introduces a drop in domestic rice and wheat yields. This low yield shock is modelled as a short-term event, in which both wheat and rice yields are 10% lower during the years 2022 and 2023.

Box 4.2. Risks to food security in India

For households in India, external events can pose significant risks to food security. As noted there is a significant number of households that sit close to the undernourishment threshold (however defined). Events that cause movement in prices without commensurate increases in income can therefore push large numbers into food insecurity. Food insecurity risks in India can be divided into two broad categories; risks due to natural phenomena and risks due to market and other economic situations. Natural phenomena that cause food insecurity include droughts, floods, cyclones and earthquakes, which could affect both the availability and the access to crops in the country. The macroeconomic risks include international and domestic economic crises as well as spikes in food prices in the international market.

Droughts represent the most significant natural event that affects production in India (Chapter 2). One of the reasons for this is that about 56% of India’s gross cropped area is rain-fed and depends on the monsoon rains in the four months of June to September which together account for about 76% to 80% of annual precipitation of the country. Any event that disrupts monsoons, affects the country’s agricultural production broadly. Key staple crops are particularly vulnerable, with the amount of rice area drought prone, for example, estimated to be around 13.6 million ha out of a total 22.3 million ha (Pandey and Bhandari, 2009). The most severe droughts in the past have affected more than 60% of the area of the entire country (De, Dube and Rao, 2005). Overall, the frequency of droughts in India is estimated to be between 1 in every 4 and 1 in every 5 years (Pandey and Bhandari, 2009; Tyalagadi, Gadgil and Krishnakumar, 2015; Saini and Gulati, 2014; Mall et al., 2006).

While the use of irrigation for staple crops is significant and has decreased the exposure of many farmers, droughts still have a substantial impact on the production of crops and the income of farmers. For example, a study on three states of eastern India, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Orissa, shows that the estimated loss of crops during drought years is 36% of the average value of production in the area (Pandey and Bhandari, 2009). The same study shows that when the loss by droughts is averaged over a span of drought and non‑drought years, the estimate of the annual loss is USD 162 million or 7% of the average of outputs in eastern India. The household-level data analysis from the study indicates a substantial loss of 40% to 80% of the total agricultural income, as well as 13 million additional people who fall back into poverty in drought years. Going forward, as much of India’s water resources are under pressure and are subject to decreased availability with climate change, the severity of future events is likely to increase.

Beyond natural events, international price movement can also negatively impact food security – particularly if they are sudden. Recent history shows the potential for sudden and often policy exacerbated price movements on international markets such as those seen in 2007/08 and 2010/11. While the reasons varied, the price rises can pose a significant risk to food security if the incomes of households do not increase to cover the rising cost of food.

A temporary decrease in the domestic supply of wheat and rice due to lower yields is projected to lead to temporary reductions in per capita food consumption under both the baseline and the DBT scenario (Figure 4.19). However, the outcomes under DBT are better than with food distribution alone as the average per capita calorie intake in the low income groups is projected to remain higher under the DBT scenario compared to the baseline. Under the DBT scenario, the functioning of domestic markets mean they are better able to deal with this temporary supply shortfall and as such they are more responsive to consumer needs (including in the supply of substitute products) than what is possible with the release of rice and wheat from public stocks under the baseline.

Figure 4.19. Daily calorie intake (supply) per capita in four demand groups during high international price period combined with domestic yield drops for wheat and rice, for baseline and DBT scenario

Note: Calorie intake is calculated based on total food availability.

Source: OECD simulation results.

The improved role of markets under the DBT scenario becomes evident when examining how domestic prices relate to the international price. Figure 4.20 illustrates for rice the ratio of domestic prices over international prices under the baseline and the DBT scenario, without and with shocks. In the absence of high international prices and a domestic yield shock (without shocks), the ratio under the DBT scenario is close to 1, while the ratio under the baseline is below 1. This illustrates that prices are modelled to be better integrated under the DBT scenario. If international prices are higher during the projection period and India experiences a yield shock (with shocks), then the price ratio will surge during the years of lower yields.

Figure 4.20. Domestic price of rice as a share of the international price under baseline and DBT scenario, without and with shocks

Source: OECD simulation results.

This surge will be much more pronounced under the baseline than under the DBT scenario because of two factors. First, domestic prices will increase less under the DBT scenario given that India will significantly reduce its exports when it is faced with low domestic supply (Figure 4.21). Second, international prices will rise more under the DBT scenario than under the baseline. Since India is the largest rice exporter in the world, the fall in yield and therefore supply (both in aggregate and because Indian consumers have more resources available to consume the higher priced rice domestically) means that this event has a significant impact on international prices. When India reduces its exports, this will negatively affect the international availability of rice and hence lead to an increase in international prices. In the case of wheat, the international impacts are more subdued given that India is not a large exporter.

While the baseline shows less of an impact on international prices, there is a possibility that they may be influenced significantly if India repeats its past use of export restrictions. It is not unlikely that India might reinstate an export ban, particularly when faced with high international prices. Unless there are regulatory reforms that explicitly prohibit the use of quantitative export restrictions, as is the case under the DBT scenario, it is possible that exports are banned or restricted using policy measures. In this case, the impacts on the international markets could be significant and would not be driven by market developments, but instead determined by policies.

Figure 4.21. Rice exports during period of high international prices (2017-25) combined with low yield in India (2022-23), for baseline and DBT scenario

Source: OECD simulation results.

Key messages

Simulations using the Aglink-Cosimo model examine what would happen over the period 2017‑25 if the NFSA remains in place (baseline) compared to a situation where the TPDS is gradually and partially replaced by DBT and regulatory reforms are introduced (DBT scenario). The key findings are as follows:

People entitled to TPDS food grains are at least as well off in terms of per capita calorie consumption (availability) when they receive cash transfers instead of physical grain.

The composition of diets is projected to be more varied when consumers receive cash than when they can buy rice and wheat at subsidised prices. Increased consumption of fruits and vegetables, milk, dairy products and pulses makes diets more balanced and meals more nutritive. This way the missing absorption element of food security from the current system of TPDS/NFSA is addressed effectively.

The introduction of cash transfers combined with better functioning markets under the DBT scenario leads to relatively higher consumer prices for rice and wheat than under the baseline. These higher consumer prices under the DBT scenario would not negatively affect the overall food security situation in the country because i) consumers can use the cash transfer to buy cheaper or higher quality food than wheat or rice, ii) some consumers with limited access to markets or where cash transfers are not feasible can still rely on a reduced TPDS and iii) farmers with marketable surpluses will receive higher prices and hence more revenues.