The microdata analysis in this paper is based on the Slovenian Financial Administration’s administrative income tax records, which follow the entire population of approximately 1.85 million taxpayers over the period 2015 to 2016. The microdata, provided by the Financial Administration, represent the most comprehensive source of information on incomes, taxes and social security contributions (SSCs) in Slovenia. For the purposes of the microdata analysis, small amounts of reported gross income are removed below EUR 500, which would otherwise skew the distributional data, which has virtually no effect on total income but reduces taxpayer observations to 1.5 million in each year.1

OECD Tax Policy Reviews: Slovenia 2018

Annex A. Methodology

Microdata

Comparison with survey data

Compared with survey data, tax record data have several advantages (Jenkins, 2011[1]). First, coverage of the full taxpayer population allows for specific sub-group analysis while retaining adequate sample size. Second, it is an offence to submit a false tax return so incomes are mostly free from measurement error such as misreported incomes. Third, as noted by Jenkins, tax records are often ‘used as a validation gold standard against which to assess measurement error in survey-based income data’. For example, it gives a scarce insight into income dynamics at the very top end, where the tax records are more representative.

There are also limitations to administrative data. For example, the data is confined to those who complete tax returns and does not cover those entirely reliant on untaxed benefits. For example, the total population also includes individuals which do not interact with the tax system including 300 000 persons under 15 years of age and around 80 000 unemployed. Unlike most survey data, tax record data have limited demographic data, such as educational attainment. It also does not include all benefit data such as direct transfers such as child benefit transfers. In addition, while the tax records are based on the gross incomes of taxpayers, survey data are typically based on an equivalisation of the disposable incomes of households, which reduces comparability.

Tax coverage of microdata

While microdata total personal income tax (PIT) and SSC for 2015 and 2016 are broadly similar to official tax revenues reported by the Ministry of Finance of Slovenia (2018), it is important to note that they do not match exactly for a number of reasons (Table A.1). For example, it is not possible to identify part-time employment in the microdata provided, and where the tax rules differ, it is not always possible to distinguish who is receiving certain income.

Table A.1. Tax revenue coverage of microdata

PIT and SSC (EUR millions)

|

2015 |

2016 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Financial administration microdata |

Ministry of Finance |

Financial administration microdata |

Ministry of Finance |

|

PIT |

1 785 |

1 986 |

1 899 |

2 079 |

|

Employee SSC |

3 072 |

2 893 |

3 190 |

3 020 |

|

Employer SSC |

2 590 |

2 125 |

2 685 |

2 233 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Ministry of Finance of Slovenia tax records microdata.

Total income by income category

In Slovenia, there are six categories of income: employment, business, agriculture, rental, capital (interest, dividends and capital gains) and other income. According to the microdata for 2016, Slovenia earns over EUR 21.2 billion in incomes, of which EUR 19.7 billion or over 90% is employment income (Table A.2). These are largely salaries (64% of total income) and pensions (21%). Income from business, agriculture, rental and capital comprise 2.7%, 0.5%, 1.8% and 1.4% of total income respectively.

Table A.2. Average and total incomes, by income type

Based on 1 498 185 taxpayers 2016

|

|

Mean (EUR) |

Total (EUR millions) |

% |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Gross |

14 196 |

21 268 |

100 |

|

of which: |

|||

|

Employment |

13 176 |

19 740 |

92.8 |

|

of which: |

|||

|

Salary |

9 098 |

13 631 |

64.1 |

|

Pension |

2 921 |

4 377 |

20.6 |

|

Other employment |

1 157 |

1 733 |

8.1 |

|

Business |

387 |

579 |

2.7 |

|

of which: |

|||

|

Actual cost regime |

277 |

415 |

2.0 |

|

Flat-rate regime |

110 |

164 |

0.8 |

|

Agricultural |

69 |

103 |

0.5 |

|

Rental property |

144 |

216 |

1.0 |

|

Other |

112 |

168 |

0.8 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Ministry of Finance of Slovenia tax records microdata.

Taxpayer classifications

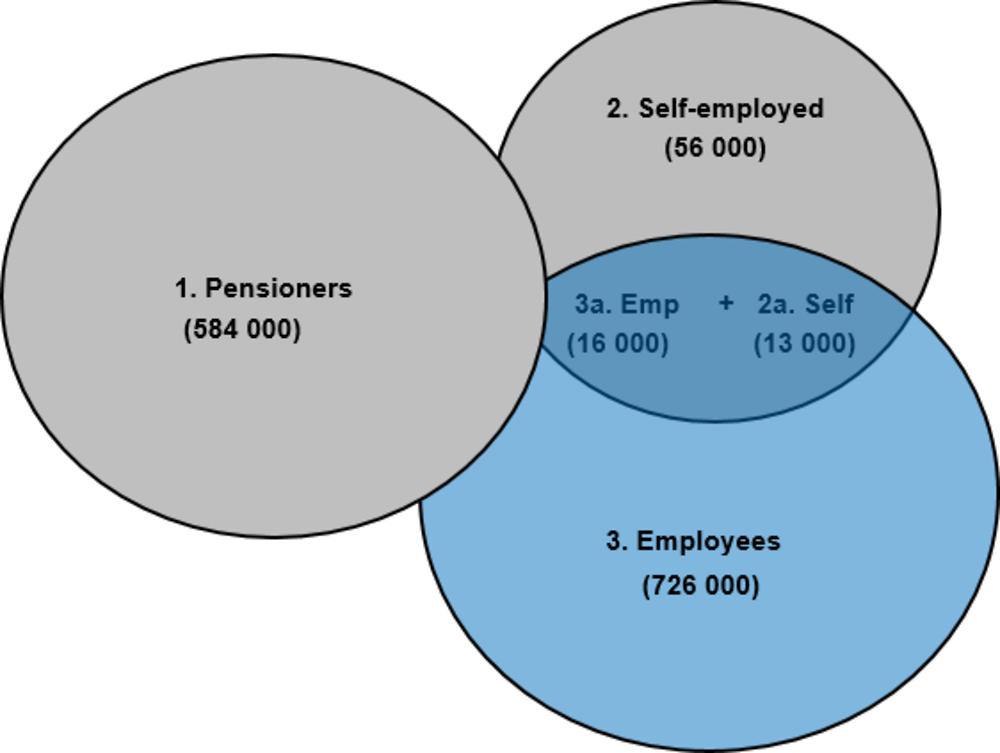

Taxpayers can derive income from multiple sources; sometimes at the same time. For the purposes of the microdata analysis, taxpayers are defined and classified into three mutually exclusive groups as follows: pensioners, self-employed and employees. A stylised illustration of the groups is shown in Figure A.1.

First, pensioners are defined as taxpayers with any pension income (even where they have additional employment or self-employment income).

Second, the self-employed are defined as taxpayers that have no pension income but have a self-employment income which is at least 15% of salary and self-employment income combined. The purpose of this definition is to capture those taxpayers with significant self-employment activity.

Third, employees are defined as taxpayers with a salary income and no pension income. Taxpayers that have predominately a salary income but also a small self-employment income (up to 15% of salary and self-employment income combined) are also classified as employees. In this way, when taxpayers have both employment and self-employed income, they are assigned to one group based on the extent of their self-employment income. By construction then, those defined as employees or the self-employed do not have any pension income.

Figure A.1. Stylised illustration of taxpayer groups, 2016

Note: Circle sizes are stylised and do not correspond to taxpayer numbers. Numbers rounded to nearest thousand for illustration.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Ministry of Finance of Slovenia tax records microdata.

For each category, a stricter definition can be applied to include only those taxpayers that exclusively derive their income from that category (i.e. 100% of their income). For simplicity, these are referred to as ‘full’ employees, self-employed and pensioners.2

The Table A.3 shows taxpayer numbers for the total and full groups in 2016. In 2016, there are approximately 742 000 employees, 584 000 pensioners and 69 000 self-employed. Together, the three groups represent a comprehensive picture of the taxpayer population – they account for over 93% of taxpayers and 98% of gross income. Taxpayers not included are, for example, those who exclusively derive income from capital, agriculture, rent or ‘other employment’ (all groups also have some mix of additional income from such sources).

Table A.3. Number of taxpayers, by group 2016

|

Total taxpayers (A) |

‘Full’ taxpayers (B) |

(A) / (B) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Employees |

741 670 |

725 655 |

98% |

|

2. Self-employed |

69 000 |

56 234 |

81% |

|

3. Pensioners |

583 530 |

537 182 |

92% |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Ministry of Finance of Slovenia tax records microdata.

Methodology of the costing of the main recommendations

This report produces various simulations to estimate the potential impacts of tax rate changes and base broadenings in Slovenia. The analysis is based on all 741 670 employees for 2016 in the microdata (with the exception of the allowances simulation which includes all taxpayers).

The analysis begins by simulating reductions in the employee SSC rate. It then extends this analysis by simulating PIT rate increases across the first four brackets and a reduction in the top PIT rate - for both a cut in employee SSCs and not. Next, the PIT implications of a base broadening measure are provided where tax allowances are reduced from 5% to 25%. In addition, an estimate of the SSC loss from capping employee SSCs is calculated.

The broad approach taken has been to reduce the reported employee SSC on the tax records and to substitute this into an estimate of taxable income – income from employment less employee SSC less allowances. Conceptually, both reduced employee SSCs or allowances will increase taxable income for all employees and will push some employees into higher PIT rate brackets. Consequently, the 2018 PIT schedule is reapplied retrospectively to the 2016 tax record data and new PIT brackets and PIT are estimated for each employee. Given this framework, PIT rate increases can be readily applied to newly estimated levels of taxable income. Similarly, reduced levels of allowances reported on the tax records can be readily substituted into the taxable income estimate. An evaluation of these estimated variables confirm that they provide reasonable estimators – estimated taxable income and estimated PIT are within EUR 1 000 and EUR 500 of actual reported amounts respectively for 90% of employees.

To simulate the impact of reduced employee SSC rates on overall SSC and PIT revenues, three methodological steps are undertaken as follows.

First, the employee SSC amount on the tax records is assumed to be 22.1% of employment income for all employees. This assumption allows for applying a range of reduced employee SSC rates which are associated with reduced SSC amounts for each employee.

Second, a new taxable income variable is defined and estimated as income from employment less employee SSCs and less allowances. Given these re-estimated variables, it is possible to simulate new levels of taxable income for each employee by substituting the reduced SSC employee amounts into estimated taxable income. Conceptually, reduced employee SSCs increase taxable income and push some employees into higher PIT rate bracket.

Consequently, given new levels of taxable income, PIT must also be re-estimated for each employee using the PIT rate schedule. To do this, the latest 2018 schedule is applied retrospectively to the 2016 tax record data. An evaluation of these estimated variables confirm that they provide reasonable estimators – estimated taxable income and estimated PIT are within EUR 1 000 and EUR 500 of actual reported amounts respectively for 90% of employees. The estimated PIT, with employee SSC set at the current 22.1%, is used as the comparison counterfactual for the simulated reforms.

Finally, two caveats are important. First, the analysis assumes no behavioural change and linearity. Second, while the microdata PIT and SSCs are broadly similar to total tax revenues reported by the Ministry of Finance of Slovenia, they do differ for various methodological reasons.

References

[1] Jenkins S. (2011), “Changing Fortunes: Income Mobility and Poverty Dynamics in Britain”, Oxford University Press, Oxford. 2011.

Notes

← 1. Since no such cut-off threshold is used for other variables, the average of these variables may appear relatively lower than gross income.

← 2. For the self-employed this would include only those taxpayers with 100% self-employment income (and no pension or employment income), for employees only those taxpayers with 100% salary income (and no business or pension income) and for pensioners only those with 100% pension income (and no employment or self-employment income). These groups are loosely referred to as pure pensioners, pure self-employed and pure employees.