This chapter highlights the challenges New Zealand faces in the area of mental health and work. It offers an overview of the labour market outcomes of people with mental health conditions in New Zealand compared with other OECD countries, and looks at their economic well-being. The chapter also examines differences in outcomes by ethnicity and discusses the definition of mental health and the data sources used in this report.

Mental Health and Work: New Zealand

Chapter 1. Mental health and work challenges in New Zealand

Abstract

Mental health conditions present major challenges to the functioning of labour markets and social policies in OECD countries, directly affecting a range of policy areas including youth and education policy, health policy, workplace policy, and employment and welfare policy. Mental health is closely linked with well-being and quality of life and can affect education, employability and performance at work. Yet countries have so far failed to identify and address problems adequately. This is a reflection of the widespread discrimination attached to mental health even though society pays a high price.1

Defining and measuring mental health

This report considers as mental ill health any condition that has crossed a clinical threshold criterion, drawing on definitions used by psychiatric classification systems such as ICD‑10, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems.2 At any given point in time, some 20‑25% of the working-age population in the average OECD country has a mental health condition such defined (see Box 1.1), with lifetime prevalence that can be as high as 40‑50%.

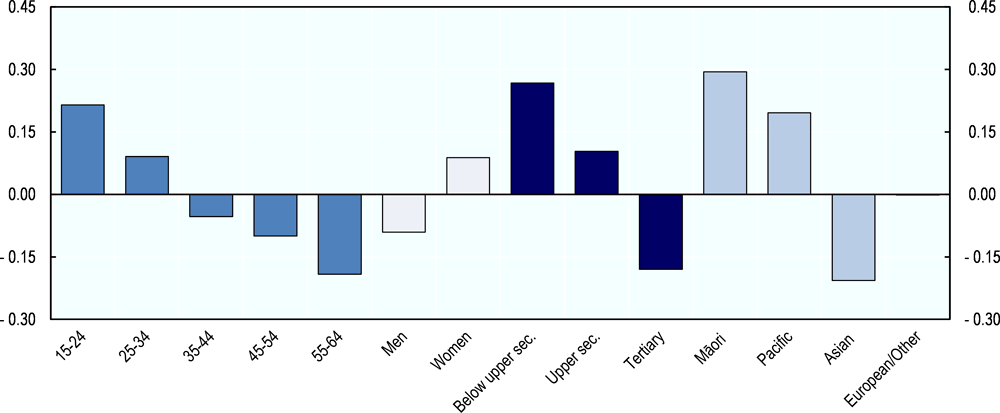

In New Zealand, the prevalence of mental health conditions varies considerable with the person’s socio-economic characteristics: like in all OECD countries, women and people with low levels of educational attainment are more likely to report mental health problems than their peers (Figure 1.1). The age gradient is also strong and in line with those in most other OECD countries where prevalence tends to be higher in younger age groups (OECD, 2012[1]). Ethnicity also has a considerable impact: Pacific Islander and especially Māori populations have a high prevalence of mental health conditions whereas prevalence is low in the Asian population; New Zealand Europeans have average rates. This suggests policy needs to have a special lens on ethnicity as well as on educational group. Young and low‑skilled Māori people seem especially vulnerable in this regard.

Understanding some key attributes of mental ill health is critical for devising good policies. These attributes include its onset at an early age; its varying degrees of severity; its persistent, often chronic nature; the high rates of recurrence; and the frequent co‑occurrence with physical or other mental illnesses, and substance use disorders. The more serious and enduring the illness, the greater the person’s degree of disability and the greater the impact on their capacity to work. Mental illness of any type can be severe, persistent and co‑morbid. Most mental health conditions fall into the category mild‑to‑moderate, especially a majority of mood and anxiety disorders, which can be enough to affect people’s performance in the workplace, their employment prospects and, more widely, their place in the labour market.

One important challenge policy makers must address or take into account is the high rate of non-awareness, non-disclosure, and non-identification of mental ill health, all of which spring from the stigma that attaches to it. Indeed, it is not always clear whether more and earlier identification always improves outcomes or, on the contrary, can contribute to labelling and discrimination, thereby risking worse outcomes. The inference is that reaching out to persons with mental health conditions is what matters: policies that detect but do not openly label mental illness will often work best, especially for young people as early diagnosing and labelling can promote life in a sick role.

Box 1.1. Defining and measuring mental health conditions

A mental health condition is a condition meeting a set of clinical criteria that constitute a threshold. When it crosses that threshold, it becomes a clinical disorder diagnosed accordingly. Threshold criteria are drawn up by psychiatric classification systems like ICD-10, Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases, in use since the mid-1990s. (The 11th revision is scheduled for release in 2018.)

Administrative data generally include a classification code that denotes how a patient or benefit recipient has been diagnosed. Codes are based on ICD-10 and so attest that there is a mental disorder that can be identified. However, administrative data do not include detailed information on an individual’s social and economic status and cover only a fraction of all people with a mental health condition.

Survey data can provide a wealth of information on socio-economic variables, while usually including only subjective assessments of the mental health status of the people surveyed. Surveys can measure the existence of a mental health condition through an instrument consisting of a set of questions on feelings and moods such as irritability, sleeplessness, hopelessness, or worthlessness. For the purposes of this work, the OECD drew on consistent findings from epidemiological research to classify the 20% of the population with the highest values (measured by a mental health instrument in a country’s population survey) as having a mental disorder in a clinical sense. The top 5% of values denote “severe” conditions and the remaining 15% indicate “mild‑to‑moderate” or “common” conditions.

The term mental health condition is used throughout this report, to refer to people with mental illnesses, mental ill health, or mental disorders. This includes people who have had formal diagnosis, or people who through administrative surveys are in the top 20% on validated instruments to measure mental distress, as outlined above.

This methodology allows comparisons across different mental health instruments used in different surveys and countries. OECD (2012[1]) offers a description and explanation of this approach and its possible implications. Importantly, the aim in this report on New Zealand is to measure the social and labour market outcomes of persons with mental health conditions, not the prevalence of mental disorders as such. To that end, the report takes data from a number of surveys:

The New Zealand Health Survey for the year 2016/17 that uses the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) to identify the mental health status of the surveyed population. K10 uses a 10-item questionnaire on emotional states experienced in the previous 30 days. Each question has a response scale going from 1 to 5 (“1” meaning none of the time and “5” meaning all of the time). The final score which rates the respondents’ psychological distress ranges from 10 (no mental health condition) to 50 (very severe condition).

The General Social Survey 2008, 2010, 2012 and 2014 which measures the mental health status of the respondents with the mental health and vitality items from the Short Form General Health Survey, known as SF 12 scale, which was developed to measure the quality of life and health. The mental health and vitality questions are similar in nature to the questions used by K10 and use the same scale from 1 to 5.

Figure 1.1. The prevalence of mental health conditions in New Zealand varies with age, gender, level of education and ethnicity

Note: “Below upper secondary” refers to Levels 0‑2 in the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED), “Upper secondary” to ISCED 3‑4 and “Tertiary” to ISCED 5‑6.

Source: OECD calculations based on the New Zealand Health Survey, 2016/17.

Social and economic outcomes: Where New Zealand stands

Mental health exacts a high price on the economy

According to cost estimates prepared on a disease-by-disease basis, direct and indirect costs of mental health for society stand at between 3% and 4.5% of GDP across a range of selected OECD countries (Gustavsson et al., 2011[2]). Indirect costs such as the costs for reduced productivity at work account for 53% of the total, direct medical costs for 36% and direct non-medical costs for 11%.3

Comparable cost data for New Zealand are unavailable. However, a recent study on the economic cost of serious mental illness in Australia and New Zealand estimates a cost corresponding in value to around 3.5% of GDP for Australia and 5% of GDP for New Zealand (RANZCP, 2016[3]). This study looks at serious mental health conditions only but also includes the costs of comorbidities. Other estimates for Australia find a cost similar to 2.2% of GDP for all mental health conditions if including direct costs only (Medibank and Nous Group, 2013[4]); including the higher indirect costs would likely bring this figure to over 4% of GDP. Given that the cost of serious mental health conditions is higher in New Zealand than in Australia, it can be concluded that the total cost of mental health to the New Zealand society is in the order of around 4‑5% of GDP and thus at the top-end among OECD countries.

Mental health problems impede full labour market participation

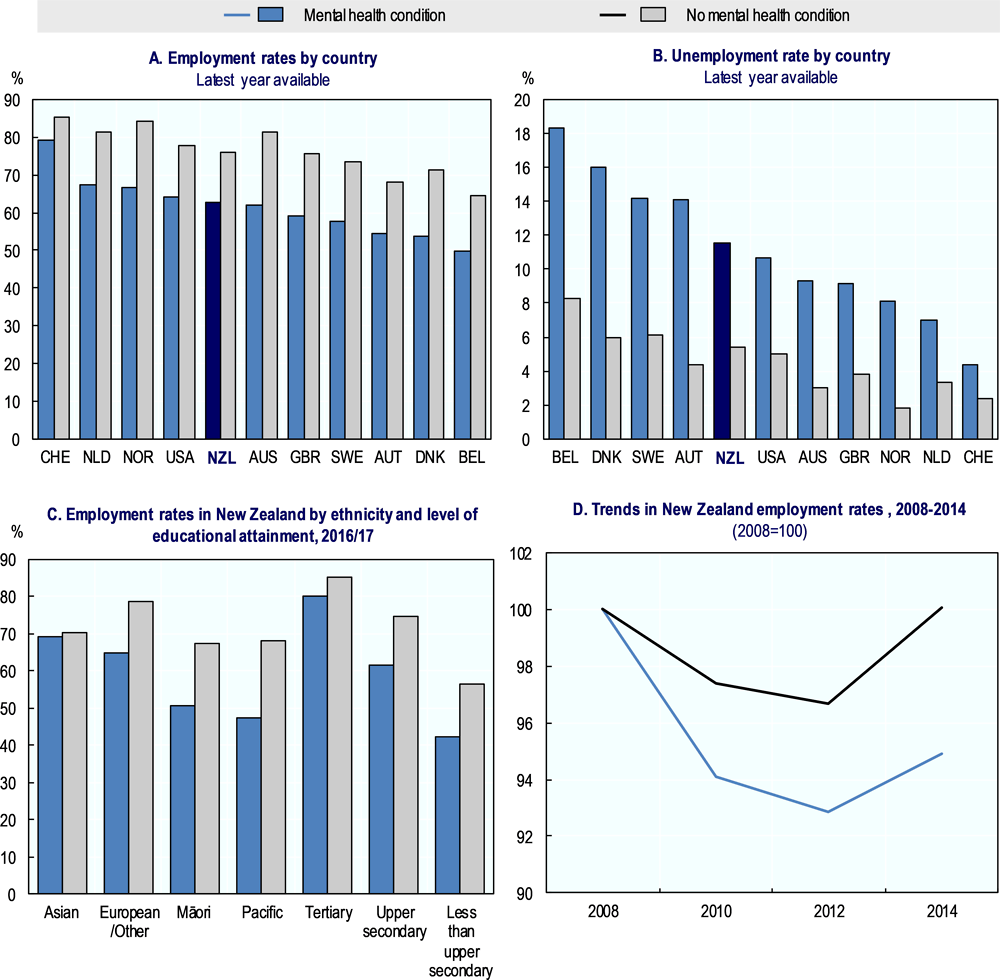

The majority of persons with a mental health condition have a job but mental health strongly affects rates of employment and unemployment in all OECD countries. In New Zealand, the mental health employment gap is 13 percentage points; this is in the mid-range of OECD countries. The employment rate of persons with mental health conditions is 63% compared to 76% for those without conditions (Figure 1.2, Panel A).

Figure 1.2. Mental health conditions strongly affect employment and unemployment and improvements in New Zealand since 2008 were minimal

Source: Panel A and B: OECD calculations based on national health surveys. Australia: National Health Survey 2011/12; Austria: Health Interview Survey 2006/07; Belgium: Health Interview Survey 2008; Denmark: National Health Interview Survey 2010; Netherlands: POLS Health Survey 2007/09; New Zealand: Health Survey 2016/2017; Norway: Level of Living and Health Survey 2008; Sweden: Survey on Living Conditions 2009/10; Switzerland: Health Survey 2012; United Kingdom: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2007; United States: National Health Interview Survey 2008. Panel C: New Zealand Health Survey 2016/2017; and Panel D: General Social Survey, 2008, 2010, 2012 and 2014.

People with a mental health condition face unemployment rates twice as high as those for their peers without mental health conditions, both in New Zealand (5% versus 12%) and in other OECD countries (Figure 1.2, Panel B). Persons with a severe mental health condition even face a fourfold unemployment risk.

Data for New Zealand further show that ethnicity and education also matter for labour market outcomes. People with low level of educational attainment and those who identify themselves as Māori or Pacific Islanders not only face poor mental health conditions more often than other population groups but also a larger employment disadvantage when they have a mental health condition. Their rates of employment are especially low (48‑50% for people from disadvantaged ethnic groups; 42% for those with less than upper secondary education) and the gap with the employment rate with their peers in good mental health is large (Figure 1.2, Panel C).

Finally, people with mental health conditions have not been able to benefit from the economic recovery in the past decade as much as other people did. Overall, New Zealand has weathered the global economic downturn in 2008/09 better than most OECD countries but also in New Zealand, labour market conditions have deteriorated at least temporarily. The rate of employment fell by three percentage points from 2008 to 2010 and unemployment doubled in the same period (OECD, 2017[5]). Figure 1.2 (Panel D) shows that for persons without a mental health condition the rate of employment reached its pre‑crisis level in 2014. Persons with a mental health condition saw a much sharper drop in employment after 2008 and a much slower recovery in recent years. For unemployment, the New Zealand story is similar: persons with a mental health condition suffered more from the global downturn. The fast increase in the duration of unemployment for this group of the population has yet to be reversed.

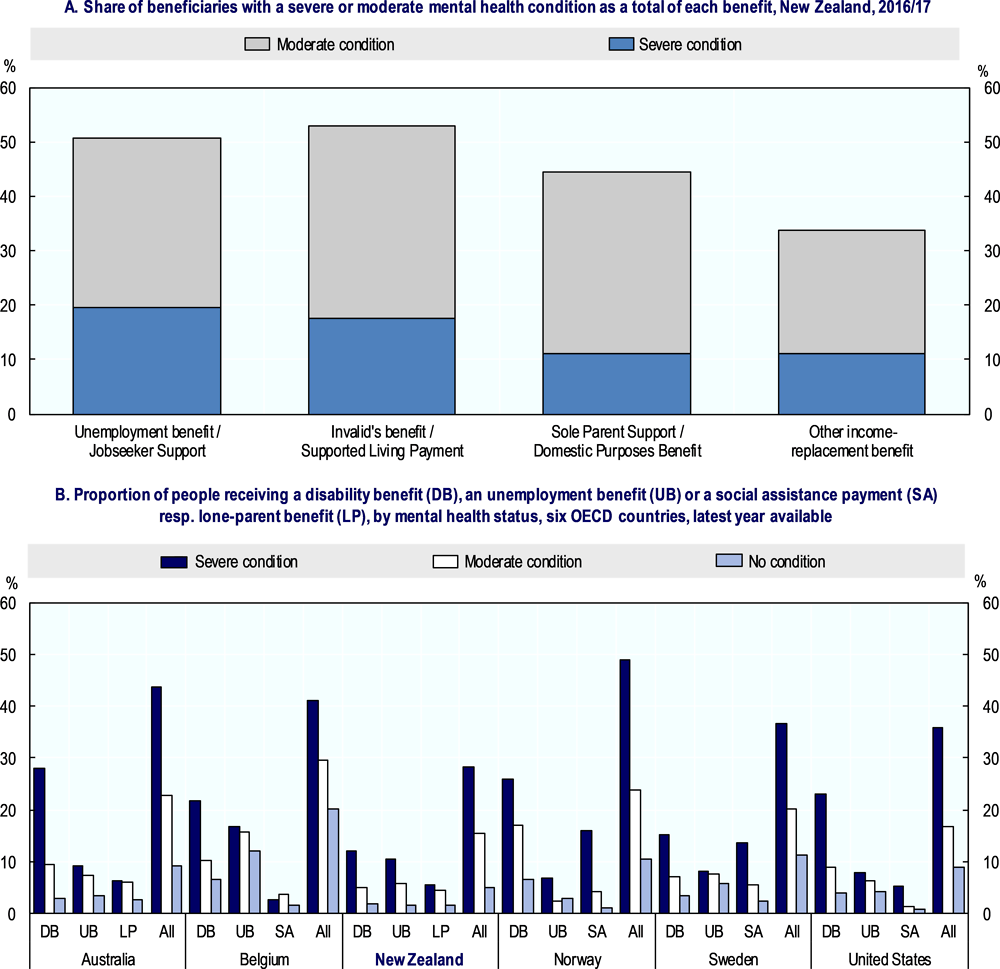

The benefit system faces and poses a number of challenges

What is happening to New Zealanders with mental health conditions who are not employed and how do they earn their living? Population survey data shed some light on these questions. As in other OECD countries (OECD, 2015[6]), the share of persons with a mental health condition among those who receive a social benefit is very high. Over 50% of New Zealanders who receive Supported Living Payment (formerly Invalid’s Benefit) have a mental health condition (Figure 1.3, Panel A). This is maybe not that surprising but among recipients of Jobseeker Support (formerly Unemployment Benefit and Sickness Benefit) and Sole Parent Support (formerly Domestic Purposes Benefit) the corresponding proportions are also 50% and 45%, respectively. Moreover, considerable shares of those people report to have severe mental health conditions, irrespective of the type of benefit they receive. This is a big challenge for the benefit system not sufficiently addressed and an indication that maybe many people with mental health conditions if not working end up on benefit, at least temporarily.

Figure 1.3 (Panel B), however, also shows that the share of this group who receive any social benefit is much lower in New Zealand than in other OECD countries; to a significant degree, this is explained by the strict means-testing of benefit entitlements in New Zealand which is uncommon in other countries, except Australia. Among those with a severe mental health condition, 28% receive a social benefit in New Zealand – compared to 36% in the United States, more than 40% in most other OECD countries and even 50% in Norway. For those with a common mental health condition, the share is 15% in New Zealand, 17% in the United States and 20‑30% in the other countries for which comparable data are available. Adding employment rates and estimated beneficiary rates together suggests that, roughly speaking, one in four New Zealanders with a severe mental health condition are without income from either work or social benefits. The corresponding shares for people with a common mental health condition or no mental health condition are around 20%. In Australia, for comparison, only around one in ten people fall into this no work-no benefit category.

Figure 1.3. The prevalence of mental health problems is high on all benefits but the share of people receiving a benefit is lower in New Zealand than in other OECD countries

Note: Other income support payments include: Regular payments from ACC or a private work accident insurer; NZ Superannuation or veterans pension; other superannuation or pensions; student allowance; other government benefits or government income support payments; war pensions; or paid parental leave.

Source: New Zealand Health Survey 2016/17; Australia: National Health Survey 2011/12; Belgium: Health Interview Survey 2008; Norway: Level of Living and Health Survey 2008; Sweden: Living Conditions Survey 2009/10 and the United States: National Health Interview Survey 2008.

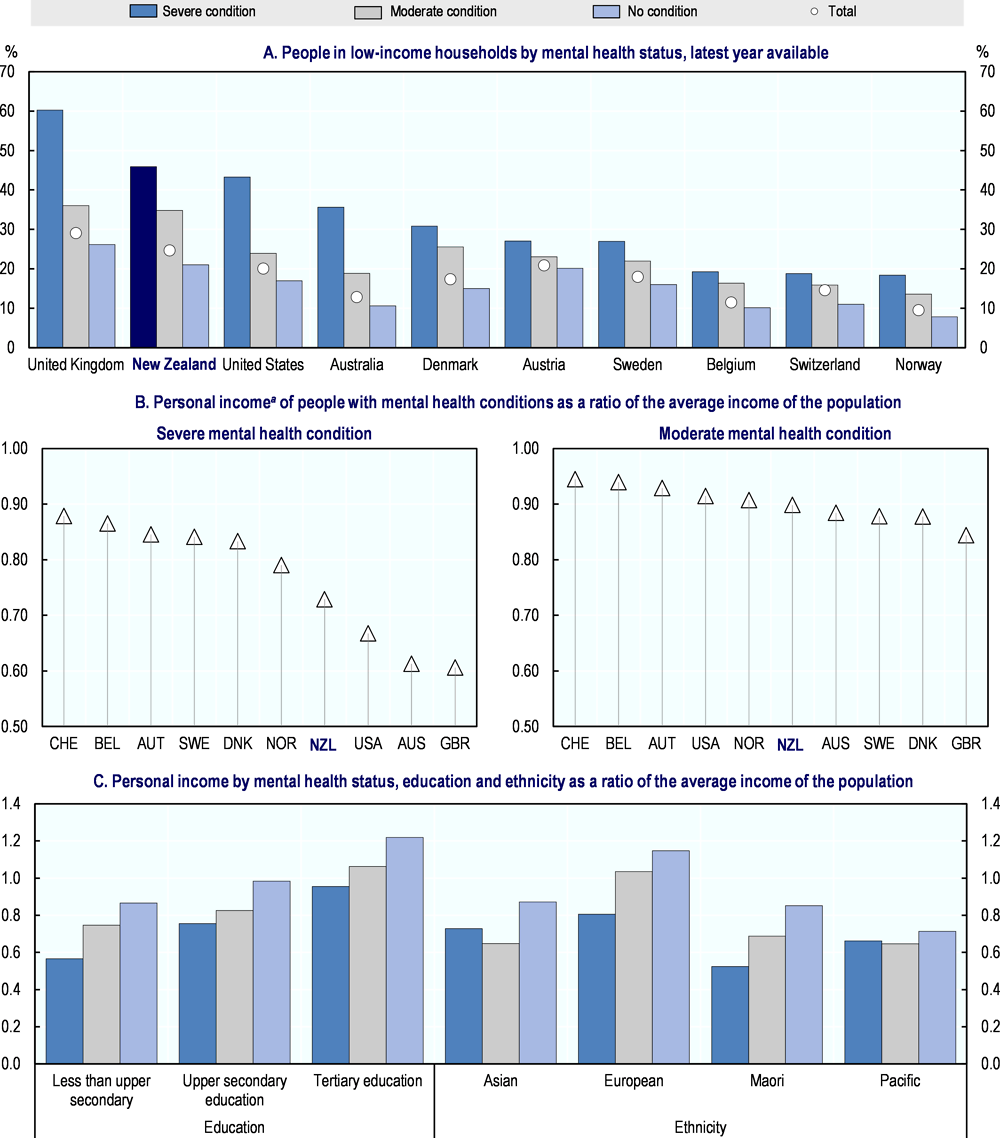

Mental health conditions strongly affect people’s economic well-being

Not having one’s own income and not being entitled to social benefits implies that a person depends on the income of others, or on own and others’ wealth. Income of other household members lifts the income of those in the no work-no benefit group, but it does so to an inadequate extent. As a result, people with a mental health condition face a much higher risk of poverty than the general population. In New Zealand, 45% of the population with severe mental health conditions live in a low-income household, compared to 35% of those with mild-to-moderate mental health conditions and 20% of those without any condition. These rates are higher than in other OECD countries except the United Kingdom: in New Zealand, poverty risks are generally very high and on top, the poverty gap by mental health status is particularly large (Figure 1.4, Panel A). Personal income of New Zealanders with a severe condition is less than 75% of the income of their peers without such condition – a share that is considerably lower than in European OECD countries with a more generous benefit system (Figure 1.4, Panel B).

Data for New Zealand also show that personal incomes vary by level of education and ethnicity. Mental ill health deteriorates the income of all educational groups but the gap is smaller for those with higher levels of education (Figure 1.4, Panel C). Differences by ethnicity suggest that for Pacific Islanders, expected differences are outbalanced by household income and household composition. This is not the case for those identified as New Zealand European or Māori; the latter have the largest mental health income gap.

Conclusion

This analysis of national data identifies a number of significant challenges that New Zealand is facing around better labour market inclusion of persons with mental health conditions; these are:

Mental ill health exacts a high price on the New Zealand economy – probably in the order of around 4‑5% of GDP every year – as it does in all OECD countries.

The prevalence of mental health conditions in New Zealand tends to be higher for women than for men, and higher for young people than for those of working-age. It is highest for those with low education and for Māori and Pacific Islanders.

People with poor mental health face lower rates of employment and higher rates of unemployment than those without mental health problems. The employment and unemployment gap is especially large for those with a severe condition.

As a consequence, roughly half of all those who receive a social benefit have an identifiable mental health condition. However, partly because of means testing of all benefits, the share of persons with mental health conditions who receive a social benefit is lower in New Zealand than in is in other OECD countries.

As a consequence of the significant employment and income gap, the poverty risk is very high in New Zealand for all people more generally and especially for those with mental health conditions.

Multiple disadvantages often come together: the Māori population has the highest mental health prevalence while at the same time facing the largest income and employment disparities.

Figure 1.4. The risk of poverty is high among New Zealander’s with mental health conditions

Note: Per-person net income adjusted for household size. For Australia, Denmark and the United Kingdom data refer to gross income. Net-income based data from the 2006 Health Survey for England (HSE) confirm the high poverty risk, even higher than in the United States. The low-income threshold for determining the risk of poverty is 60% of median income.

Source: National health surveys. Australia: National Health Survey 2011‑12; Austria: Health Interview Survey 2006‑07; Belgium: Health Interview Survey 2008; Denmark: National Health Interview Survey 2005; New Zealand: General Social Survey, 2014; Norway: Level of Living and Health Survey 2008; Sweden: Living Conditions Survey 2009‑10; Switzerland: Health Survey 2012; United Kingdom: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2007; United States: National Health Interview Survey 2008.

Box 1.2. The Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC)

The Accident Compensation Corporation is a Crown entity administering the country's universal no-fault accidental injury scheme. ACC’s support provides financial compensation and supports the rehabilitation of citizens, residents, and temporary visitors who suffer a personal injury within the country.

ACC purchases mental health and vocational rehabilitation services for people who have a mental injury (ACC does not provide support for mental illness in the same way, as it does not cover physical illness). ACC distinguishes between three key different types of mental injury it covers. First, work-related mental injuries where a discrete causative event at work results in a clinically significant cognitive, behavioural or psychological dysfunction. Second, mental injury arising from physical injury, for example, in cases where a claimant suffers a physical injury during a car crash and subsequently develops a post traumatic stress disorder. Third, mental injury arising from being a victim of certain acts dealt with in the Crimes Act 1961 (mainly sexual abuse). The proportion of the population served under this definition has grown by around 700 claimants a year due to increased ease of access to services.

The original Woodhouse Report on which the scheme, introduced in 1971, is based intended that ACC gradually expand to include disabilities of various sorts as well as illnesses (including mental health conditions) over time. While there continues to be some discussion of possible scheme expansion, the current focus of policy work is on modernising the current scheme and better supporting claimants in their access to entitlements under the current Act.

References

[8] Durie, M. (2002), “Universal provision, indigeneity and the Treaty of Waitangi”, Victoria University Wellington Law Review, Vol. 33, https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/vuwlr33§ion=31 (accessed on 12 October 2018).

[2] Gustavsson, A. et al. (2011), “Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010.”, European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Vol. 21/10, pp. 718-79, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.08.008.

[7] Mane, J. (2009), “Kaupapa Māori: A community approach”, MAI Review, Vol. 3/1, http://review.mai.ac.nz (accessed on 12 October 2018).

[4] Medibank and Nous Group (2013), The Case for Mental Health Reform in Australia: A Review of Expenditure and System Design, Medibank Private Limited and Nous Group, https://www.medibank.com.au/client/documents/pdfs/the_case_for_mental_health_reform_in_australia.pdf (accessed on 05 June 2018).

[5] OECD (2017), Back to Work: New Zealand: Improving the Re-employment Prospects of Displaced Workers, Back to Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264264434-en.

[6] OECD (2015), Fit Mind, Fit Job: From Evidence to Practice in Mental Health and Work, Mental Health and Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264228283-en.

[1] OECD (2012), Sick on the Job?: Myths and Realities about Mental Health and Work, Mental Health and Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264124523-en.

[3] RANZCP (2016), The economic cost of serious mental illness and comorbidities in Australia and New Zealand, Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, Melbourne, https://www.ranzcp.org/Files/Publications/RANZCP-Serious-Mental-Illness.aspx (accessed on 05 June 2018).

Notes

← 1. This report does not include in mental disorders intellectual disabilities such as learning disabilities, and problems that develop later in life through brain injury or neurodegenerative diseases like dementia. Organic mental illnesses are also outside the scope. Addiction and substance use disorders are not directly addressed either in this report although many of these disorders are covered indirectly, due to considerable co-occurrence with other mental health conditions, especially anxiety and depression disorders. Many of the policy issues and conclusions equally apply for people with addiction. However, there are also specific challenges around staying in work and returning to work, which are different for people with addiction; these challenges have not been covered in this project and would require distinct policy recommendations and changes.

← 2. The prime concern of the report is the mutual interplay between work and poor mental health. It uses a number of interchangeable terms that are general in scope to denote poor mental health: “mental ill health”, “mental health problem” or “mental health condition” and sometimes “mental disorder” or “mental illness”. It specifies, where necessary, whether a condition is severe or mild-to-moderate.

← 3. Indirect costs in this study refer to productivity losses and the costs of social benefits. Direct medical costs include goods and services related to the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of a disorder. Direct non-medical costs are all other goods and services pertaining to a mental disorder, e.g. social services.