This chapter evaluates policies and programmes aimed at strengthening the employment focus of the mental health system. The analysis examines how New Zealand’s health system promotes wellbeing and supports mental health conditions when they arise, ensuring that appropriate and timely access to adequate services which recognise the benefits of meaningful work for people experiencing mental health conditions are available. It considers how the system provides training and support to health practitioners, particularly in primary care; and the tools and incentives available to address work and sickness issues. The analysis uses the 2015 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policy as the primary benchmark for informing best practice policies in this field.

Mental Health and Work: New Zealand

Chapter 2. Mental health care and the integration of employment support in New Zealand

Abstract

Introduction

Health systems can prevent a reduced capability to work and improve the labour market participation of people with mental health conditions through timely, adequate treatment and the provision of work-focused health care.

To help to achieve this it is essential that all health care providers understand that work has a positive effect on recovery from mental health conditions and they can enact their role in helping people with mental health conditions to stay at work, or return to work (OECD, 2015[1]). At the same time, work-related issues can contribute and exacerbate mental health issues. The links between mental health and work are therefore inextricable, and integrated mental health and employment support services are crucial. Policy action is necessary as it can help to build structures that integrate mental health and employment support services at a delivery and workforce level, and across specialist, primary and community care.

Primary care-based organisations have a particularly important role in improving the labour force participation of people with mental health conditions. Primary health care are frequently the gatekeepers to secondary and tertiary care where later access to care is less cost effective. This is particularly the case once the person has fallen out of the workforce. Building the capacity and capability of primary care-based services to respond effectively to people preferably while they are still working, but also quickly once they are not, is essential.

The main challenges and opportunities for mental health care and employment

The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policy calls upon its member countries to: “seek to improve their mental health care systems in order to promote mental well-being, prevent mental health conditions, and provide appropriate and timely treatment services which the benefits of meaningful work for people with mental health conditions”, detailing key priorities for action policy makers should consider. Table 2.1 gives an assessment of New Zealand’s performance against the OECD Council Recommendations, and suggested actions. In summary:

Despite the health reforms, New Zealand has a health system, which is strongly orientated to, and invested in, the provision of clinical services, with pharmacology the dominant model of treatment for mental health conditions. Where non-pharmacological treatments are available, access is inconsistent and inequitable.

National and regional health policy and funding levers need to be used to increase the capability and capacity of the primary care-based system and workforce to identify and support mental health conditions, to understand the interrelationship between mental health and work, and to support people to get and keep a job or manage a return to work.

The prevalence of mental health conditions is much greater than the system’s capacity to respond. There is a lack of investment and therefore capacity across primary‑based services implying that the demand on specialist services is increasing. Large numbers of people with mental health issues that could be supported earlier are not having their needs met. A shift of resources across general health into mental health services, coupled with a rebalance of the funding from specialist to primary‑based services, is required.

Table 2.1. New Zealand’s performance regarding the OECD Council Recommendations around improving improve the health systems response to mental health conditions

|

OECD Council Recommendation |

New Zealand’s performance |

Suggested actions |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

A |

Foster mental wellbeing and improve awareness and self-awareness of mental health conditions by encouraging activities that promote good mental health as well as help-seeking behaviour. |

Well-established set of universal and targeted programmes sustained over two decades. In 2017, the national campaign launched a focus on workplaces as part of Take the Load Off. |

Focus on the interrelationship between mental health and work, promote the role of the workplace, target groups currently underrepresented in help seeking. On-going evaluation needs to focus on i) how target populations are being reached and ii) behaviours of frontline practitioners. |

|

B |

Promote timely access to effective treatment of mental health conditions, in both community mental health and primary care settings and through co‑location of health professionals to facilitate the referral to specialist mental health care. |

Mental health system focuses on secondary and tertiary care. Costs to the patient for primary care remain a barrier to access. Opportunity to intervene early, for everyone, is being missed. Treatment is pharmacological; limited availability of therapies and employment support. |

Invest in prevention and early intervention; improve equity of access and availability of non-pharmacological treatments, integrated with employment support. Change primary care capitation payments to be based on, and follow, the patient. Invest in Māori- and Pacific-led approach to prevention and early intervention. Communication and collaboration between mental health and primary-based teams needs to be considerably strengthened. |

|

C |

Expand the competence of those working in the primary care sector to identify and treat mental health conditions through better mental health training, the incorporation of mental health specialists in primary care settings, and clear practices of referral to specialists. |

There is a high level of interest from those in primary-based services in mental health and work, and new models of care emerging. Primary care teams have some mental health training, but very limited training on the interrelationship between health and work, and limited time in GP consultations. |

Provide payment to primary care so there is time to spend on mental health as well as employment issues. Increase the time devoted in the primary care curriculum to mental health and on the link between mental health and work. Expand cultural diversity and strengthen cultural competency of health workforce. Increase the role of Mataora and Whānau Ora providers and the use of Māori and Pacific models of practice. |

|

D |

Encourage GPs and mental health specialists to address work and sickness absence issues, by use of evidence-based guidelines and by ensuring that health professionals have the necessary resources. |

A lack of precision in sickness certification practices. Very limited connection between primary care and workplaces. Limited guidance and training on health and work. |

Train primary care workforce to enhance knowledge about mental health and work and meaningful sickness certifications. Online clinical decision-making tools should include mental health and work pathways, with clear guidance on sickness certification and support to return to work. |

|

E |

Strengthen the employment focus of the mental health care system, by introducing employment outcomes in the health system’s quality and outcomes frameworks, and by fostering a better coordination with employment services. |

The health system is medically orientated only. Health policy and strategy reinforces this. Integrated employment support is well established in some services, but not nationally. Promising trials are in place integrating employment support into primary care services. |

Realign performance frameworks to support people with mental health conditions get/return to/stay at work. Employment outcomes should be part of quality and outcomes frameworks. Incentivise primary care-based services to integrate employment support services. Develop national guidance and training on supporting people return to work and managing sickness absence. |

Source: Authors’ own assessment based on all of the evidence collected in this chapter.

As a population group, Māori people experience the greatest burden due to mental health issues of any ethnic group in New Zealand. The issues of mental health and work are further compounded by other disadvantages including poorer skills and an unemployment level twice the national unemployment figure.

An integrated whole-of-government policy framework promoting the interrelationship between health care and the workplace is required. Leadership roles and responsibilities of the Ministries need to be clearly outlined, particularly across the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Social Development and ACC.

The inequitable divide between injury and illness has created a two-tier health system where integrated health services and vocational rehabilitation support is prioritised for injury through ACC, and not for illness. This is particularly significant for people with mental health conditions.

The employment focus of the health system needs strengthening. This should include employment guidance and access to employment support as a routine part of health services, and the inclusion of managing mental health and getting and keeping work as part of clinical guidance and on-line health pathways tools for the management of mental health conditions. Community organisations and Whānau Ora providers also have a key role in strengthening the employment focus of the mental health system.

Conducting a national mental health survey is a priority. This survey, unlike the 2006 survey, needs to gather data on labour force participation by severity of illness and diagnosis. There is also an urgent need for accurate data on number of people receiving primary mental health services; share of people transferred to secondary care; number of people receiving psychological therapies; waiting times for such therapies; employment status before/after treatment. This is urgently needed to inform policy making in this area and monitor the impact of changes over time.

New Zealand’s national awareness and discrimination programme should have an explicit priority to improve the labour force participation of people with mental health conditions, and targeted measures and evaluation in relation to this priority built into the programme.

A sustained programme addressing discrimination and promoting help‑seeking

The pervasiveness of mental health discrimination worldwide is surprising in view of the very high prevalence of mental health conditions. Discrimination makes it difficult for people who experience mental health conditions to achieve their educational and other aspirations in life, including to find, resume, and hold on to jobs (OECD, 2015[1]). Research into the effectiveness of interventions designed to address stigma and discrimination has found the strongest effects in shifting attitudes and behaviours comes where activities involve contact with someone with lived experience of mental health conditions (the power of contact) and from sustained commitment over time. Programmes that are transitory in nature have less long-term impact (Thornicroft et al., 2016[2]).

Established in 1996, New Zealand was one of the first countries in the world to set up a national programme to improve public attitudes and reduce discrimination. The anti-stigma programme “Like Minds, Like Mine” (LMLM) is underpinned by the social model of disability and the power of contact. It combines social marketing with community‑led education. Ongoing evaluation has it has been successful in shifting attitudes and reducing discriminatory behaviours (Cunningham, Peterson and Collings, 2017[3]).

LMLM started with a focus on famous people, which has now shifted to everyday people with a range of mental health conditions, and from awareness raising to modelling inclusive relationships. From the start, people with lived experience of mental health conditions have been involved in designing and delivering the programme. An evaluation of public attitudes since the programme’s inception found that attitudes towards people with mental health conditions in the target group of 15 to 44 year-olds had improved significantly, especially among Māori, Pacific and young people (Wyllie and Lauder, 2012[4]).

Data collected during 2010 and 2011 surveyed a representative sample of people who had recently used mental health services in New Zealand and measured their experience of discrimination using the Discrimination and Stigma Scale (DISC-12). Of the 1 135 participants, more than half reported improvements in discrimination over the past five years and 48% thought the LMLM programme had helped to reduce discrimination “moderately” or “a lot” (Thornicroft et al., 2014[5]).

Annual surveys of health and wellbeing, public attitudes and help-seeking behaviours continue to be conducted. Findings from these surveys are routinely analysed to provide information to help to target future public programmes. Of relevance are that:

People are much more likely to share their problems with their family or whānau (85%), than with an employer (20%) or with work colleagues (10%).

Young people feeling connected to their culture and experiencing a sense of belonging is an important protective factor to isolation and risk of mental distress.

Annual surveys have also monitored the responses of people with mental health conditions compared to people who have not had this experience. People with lived experience are less likely to agree that most people with mental illness go to a healthcare professional to get help and more likely to agree that medication could be effective (Kvalsvig, 2018[6]).

The latest LMLM campaign, started in July 2017, Take the Load Off, focuses on health and social services, workplaces, the media and communities. This campaign should have an explicit priority to improve the labour force participation of people with mental health conditions. It should focus on the interrelationship between mental health and work, promote the role of the workplace in recognising and responding to early signs and symptoms and target key actors, particularly providers of primary care highlighting their role in improving the labour force participation of people with mental health conditions. Future surveys should monitor the attitudes and behaviours of primary care providers, particularly general practitioners (GPs).

In 2006, the National Depression Initiative (NDI) was launched. The aim of the NDI is to support primary mental health service development and improve the implementation of guidelines for GPs on managing mental health conditions, particularly depression (Cunningham, Peterson and Collings, 2017[3]). The NDI focuses on education and help seeking and has a number of components. The website includes an online self-help tool, The Journal, with a separate youth-focused website, The Lowdown. These tools are supported by television, radio and online advertising, printed resources; and telephone triage and advice, and counselling services for people seeking help for themselves or others. It is important that the reach and effectiveness of these programmes is continually monitored, particularly in relation to target populations and key frontline actors.

In addition to these two national programmes, in recent years, targeted awareness programmes have been developed, including programmes for Māori, Pacific and Asian communities, as well as young people, people living in rural communities and farmers. The Mental Health Foundation hosts resources and information related to mental health and mental wellbeing, including guidelines for the media around the portrayal of people with mental health conditions.

A particularly innovative approach has been the newly developed Te Reo Hāpai – the language of enrichment. It is based on a project to research and create Māori words and terms related to mental health, addiction and disability, to help people experiencing mental health issues and their practitioners to describe and talk about these experiences. Te Reo Hāpai is part of a national movement to revitalise Te Reo Māori.

In response to the Canterbury earthquakes, a campaign called All Right? was launched to encourage people living in Canterbury to become more aware of their mental health and wellbeing, how to improve it and when and where to seek help. As part of the All Right campaign, regular surveys have been conducted to monitor the mental health of the local population, to inform targeted responses.

Farmstrong was launched in July 2015. It consists of targeted resources to farmers to promote wellbeing and prevent mental health and physical health problems. The resources, including online videos, have been co-developed with farming communities and health practitioners. The website seeks to encourage help seeking, and includes links to other websites and specialist mental health helplines. The aim is to make a positive difference to at least 1 000 farmers, and Farmstrong has developed a number of tracking systems in order to be able to evaluate its impact.

Since 2008, New Zealand has had a national mental health literacy programme, Mental Health 101 (MH101). The primary funding for MH101 is from the Ministry of Health, which targets delivery to specific populations, but any agency or organisation not meeting the Ministry of Health criteria, can also purchase MH101. MH101 is a one-day workshop designed originally to increase the confidence of frontline government and social service staff but is now tailored to anyone who will be in contact with people with mental health conditions or addiction (www.mh101.co.nz). Since its establishment, MH101 has worked with more than 16 500 people. Māori and Pacific people make up a third of MH101 students. Learner achievement for Māori and Pacific people, measured through pre‑, immediately post- and six-month post-training learners’ self-rated confidence in recognising and responding to mental ill-health, is comparable to non-Māori and non‑Pacific people (Malatest, 2017[7]). MH101 has been benchmarked with five comparable programmes overseas, which found that learner achievement and impact was at least as good as – and often better than – achieved by other programmes (NZQA, 2017[8]). MH101 is based on the power-of-contact theory, and facilitators include people with lived experience of mental health conditions.

A devolved, complex health care system focused on specialist services

In the early 2000s, New Zealand embarked on a series of significant reforms of the health system. A recent examination of the health system has reported, however, that these reforms have not been fully realised. The reforms created Primary Health Organisations (PHOs), to provide essential primary health services mostly through general practices. PHOs are funded by district health boards (DHBs) and operate under a universal, publicly funded capitation system, which subsidises primary care for all New Zealanders but does not usually meet all the cost for the patient. There are 32 PHOs across the country. Whilst there are innovations across the country, to deliver new models of care, these seem to be led by local leaders, rather than resulting from health policies (Downs, 2017[9]).

Box 2.1 on the New Zealand health system and Box 2.2 on New Zealand health policy provide more details on the recent developments.

Box 2.1. The New Zealand Health System

The Ministry of Health has overall responsibility for leading, managing and developing New Zealand’s health system. Central government set the overall strategic direction, set expectations for service delivery standards and provide funding. Yet New Zealand’s health care system is highly devolved in the sense that more than 75% its public health budget goes to 20 District Health Boards (DHBs), according to the Population-Based Funding Formula (PBFF). The PBFF is a technical tool, which seeks to distribute funding according to the needs of each DHB's population. The tool takes accounts of socio‑economic status, ethnicity, age and sex as well as services to rural communities and areas of high deprivation. In terms of mental health services, the funding is even more devolved with 95% of the public health spending on specialist mental health and addiction services allocated to DHBs (Allan, 2018[10]).

DHBs are therefore responsible for both planning and funding within health care in their region, directly providing health care services themselves and contracting services out to external providers. The Ministry of Health oversees the DHBs actions by reviewing their spending plans on an annual basis (as a formal requirement).

DHBs provide a range of mainly hospital-based services as well as contracting with local Primary Health Organisations (PHOs), iwi providers and NGOs.

Whilst having annual plans and spending plans signed off by the Ministry, the DHBs in New Zealand have autonomy in terms of setting their own funding and healthcare priorities, in relation to their local population. Under New Zealand’s devolved health care system, DHBs are empowered by a strong sense of local voice and local engagement in deciding how best to spend their money to meet the needs of their populations – including those in the remotest and least densely populated areas. This results in a great diversity within the systems as well as (especially for a small country) a complex administrative process.

Spending on mental health and addiction services makes up between 9‑10% of the total spending on health services. For example, total health expenditure in 2015/2016 was NZD 15.63 billion (New Zealand Treasury, 2018[11]) and spending on mental health and addiction services totalled NZD 1.43 billion (Allan, 2018[10]).

The predominant focus of the mental health care system in New Zealand is in secondary and tertiary care. There is a ring-fence in place to protect the spending of the District Health Boards (DHB) budget to provide specialist mental health and addiction services to the 3% of the population with the highest mental health and addiction needs. The DHBs also have a budget directed specifically at “Primary Mental Health Services” – worth NZD 26 million or 2% of the total mental health budget. This budget is for mental health services delivered in primary care settings for people who do not meet the threshold for specialist mental health and addiction services. These Primary Mental Health Services typically involve extended GP consultations and counselling sessions. A normal visit to discuss mental health needs with the GP, however, would be part of the general “first-level service” and thus subsumed in the spending on primary care.

Box 2.2. New Zealand Health Policy and Strategy

The New Zealand Health Strategy and its accompanying Roadmap of Actions (Ministry of Health, 2016[15]) state the need for a shift across the entire health system from treatment to prevention and overcoming inequities in the health system so it works for all New Zealanders. The strategy calls for a focus on the person and for services to be customer‑friendly, remove barriers to equity, and work better together.

In 2012, three strategic documents were published that set the direction for mental health and addiction services: (1) Rising to the Challenge; (2) Blueprint II; and (3) Towards the Next Wave (Ministry of Health, 2012[16]; Mental Health Commission, 2012[17]; Workforce Service Review Working Group, 2011[18]). These documents outlined the priorities for how the system should function, the priority areas for service development, and workforce configuration needed to meet current and future mental health and addiction needs. The reports focused on mental health outcomes as well as the underpinning social determinants of health. The service development plan 2012‑17, Rising to the Challenge, has now expired, without any follow-up plan published. Whilst all documents mention the importance of the labour force participation of people with mental health conditions, they are lacking detailed guidance on the system reforms and services delivery models needed to achieve this.

The current government has prioritised mental health and in particular, child and youth mental health alongside enhancing primary and community responses. The government has commissioned an inquiry into mental health and addiction services, which will report in October 2018. The Inquiry was established in response to widespread concerns about mental health and addiction services. It will examine what good work is already happening, and where system-level change is needed.

He Korowai Oranga is the Māori Health Strategy (Ministry of Health, 2014[19]), which sets the overarching framework that guides the Government and the health and disability sector to achieve the best health outcomes for Māori people. It is web-based, so that it can be continually updated. It builds on the initial foundation of Whānau Ora (healthy families) to include Mauri Ora (healthy individuals) and Wai Ora (healthy environments). The He Korowai Oranga strategy argues that “the health system needs to demonstrate that it is achieving as much for its Māori population as it is for everyone else. DHBs have a responsibility to: reduce disparities between population groups, improve Māori health and ensure Māori are involved in both decision‑making and service delivery.”

’Ala Mo’ui is a four-year plan that provides an outcomes framework for delivering high‑quality health services to Pacific people. The long-term vision of ’Ala Mo’ui is: “Pacific ’āiga, kāiga, magafaoa, kōpū tangata, vuvale and fāmili (family) experience equitable health outcomes and lead independent lives”.

Primary care services as a whole, account for around 5% of the total health budget (NZD 920 million for 2017/2018) (Ministry of Health, 2017[12]). The share within that overall budget actually covering mental health-related visits is unknown. Recent research conducted by the OECD has identified that the average spending across OECD countries on primary care, as a proportion of the total public health spending, is around 12%.1 The proportion of the health budget invested in primary care in New Zealand seems very low, even more so in comparison with Australia’s 14% (OECD, 2015[13]), as does the proportion of the total health budget investment in mental health services.

Between 25% and 30% of the total funding for mental health and addiction services in New Zealand goes to NGOs. NGOs provide a range of mental health, addiction and wellbeing services, which includes specialised programmes for specific populations (Platform Trust & Te Pou, 2015[14]).

A range of allied health practitioners make up the primary care workforce in New Zealand including pharmacists, mid-wives, allied health workers, ambulance workers and community health workers. However, primary health care services are – predominantly – privately owned and privately operated general practices.

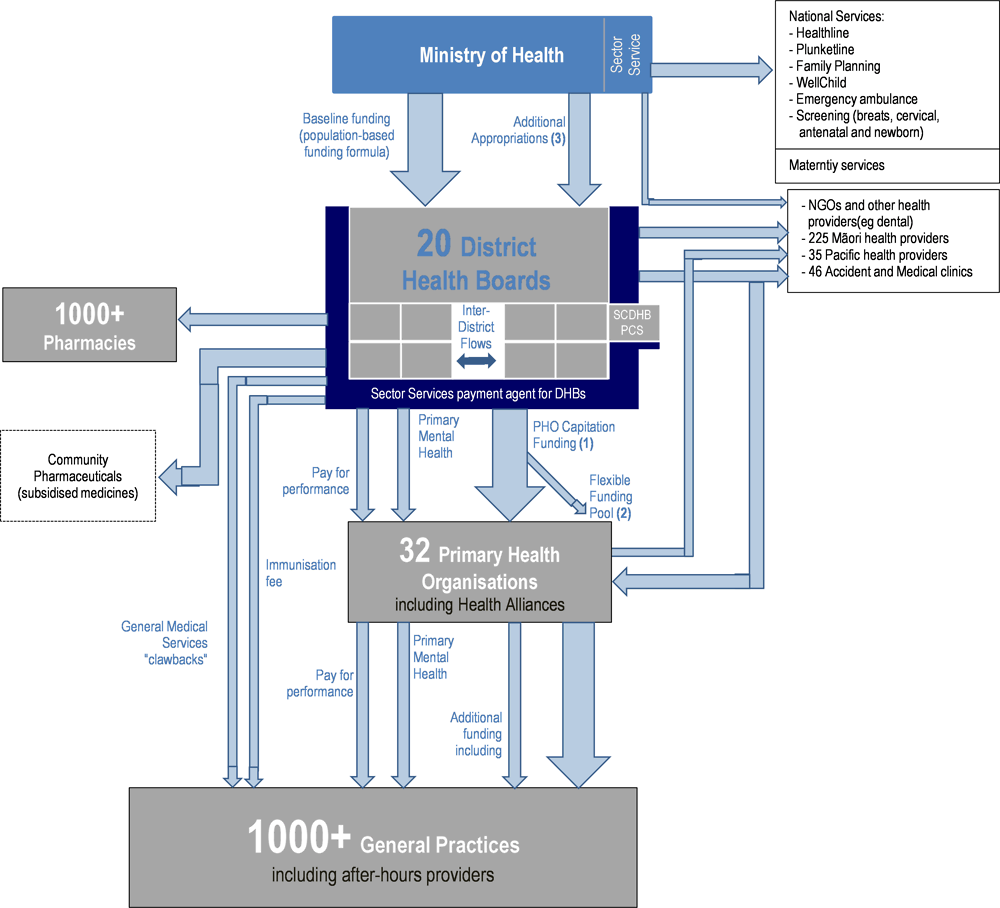

For the size of the population, New Zealand has a complex, seemingly fragmented primary and community health funding and contracting system. Whilst simplifying the system of funding and contracting is needed this should be accompanied by a shift in funding from physical health to mental health (to achieve mental health parity within the health budget proportionate to mental health need) and increasing the proportion of health investment in primary and community services, in line with other OECD countries. A further barrier that needs addressing to support health promotion and early intervention is to address the charge to the patient in primary care, but not for specialist services. Figure 2.1 shows the complexity of the funding and contracting arrangement. The Ministry of Health contracts with 20 DHBs. The DHBs then contract with several organisations in their regions, including PHOs, pharmacies, non-government organisations, Māori and Pacific providers. The 32 PHOs fund and contract with more than 1 000 general practices across the country.

Figure 2.1. Primary health care services funding

Source: Adapted from the Ministry of Health.

Early access to effective treatment is not the norm

Providing effective and timely access to mental health care is a challenge faced by all OECD countries, as under-treatment is a persistent problem, as well as targeting the right form and intensity of treatment for people with different needs. Thus, in many OECD countries, most people with mental health conditions do not find their way into the health care system and many experience an unmet need for treatment. Furthermore, people who do receive treatment often do so from non-specialists, mainly general practitioners. Very few are in the care of mental health professionals.

In New Zealand, the last comprehensive mental health survey, Te Rau Hinengaro, was conducted during 2003‑04 (Oakley Browne et al., 2006[20]). The survey used the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI 3.0) to: i) estimate the prevalence of mental health conditions and addiction in the general population, and ii) identify health service utilisation and unmet need. The total population 12-month prevalence rates for anxiety are 14.8% and for mood disorders 7.9%. These prevalence rates of mood and anxiety disorders are in line with other OECD countries, of between 20% and 25% (OECD, 2015[1]).

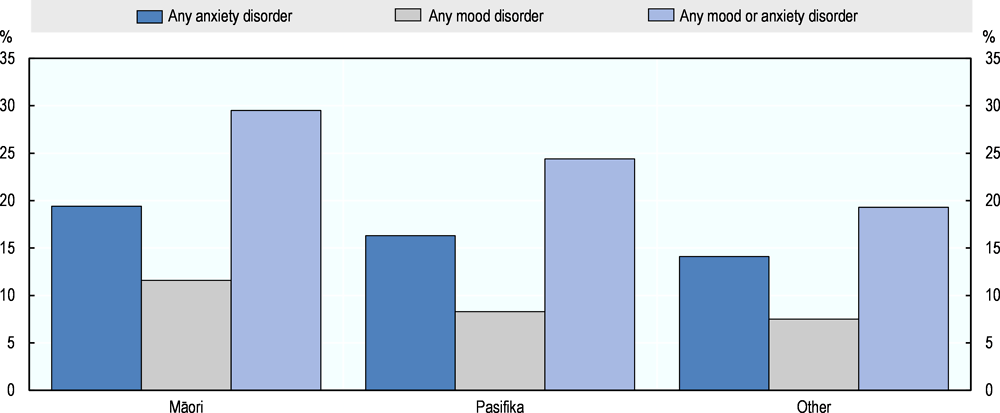

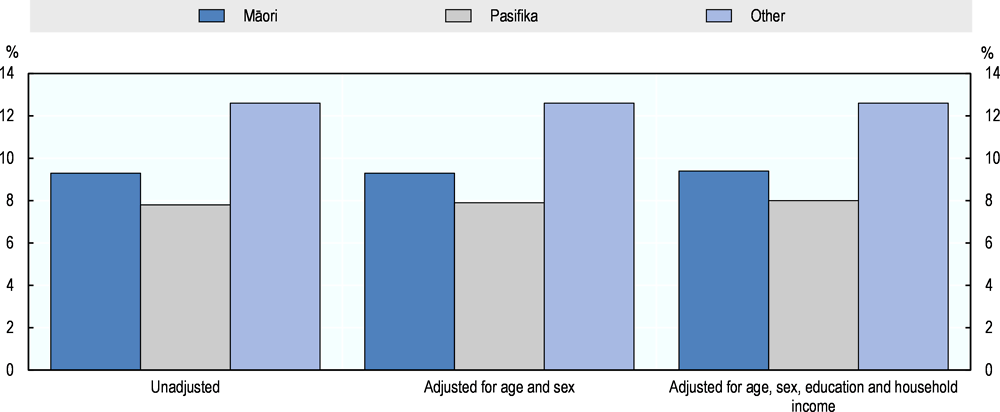

Identified mental health prevalence rates vary by ethnicity. Figure 2.2 shows the unadjusted 12-month prevalence rates of anxiety and mood disorders by three categories of ethnicity: Māori, Pacific and Other. After adjusting for age, sex, education and household income, the 12-prevalence rates for anxiety and mood disorders for Pacific people fall to 19%, just below 20% for “Other” ethnic group. Māori adjusted 12-month prevalence rates remain the highest at 24% (Oakley Browne et al., 2006[20]).

Figure 2.2. The prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders differs across ethnic groups

Source: Oakley-Browne, M., Wells, J.E. and Scott, K.M., 2006. Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey: Summary. Ministry of Health.

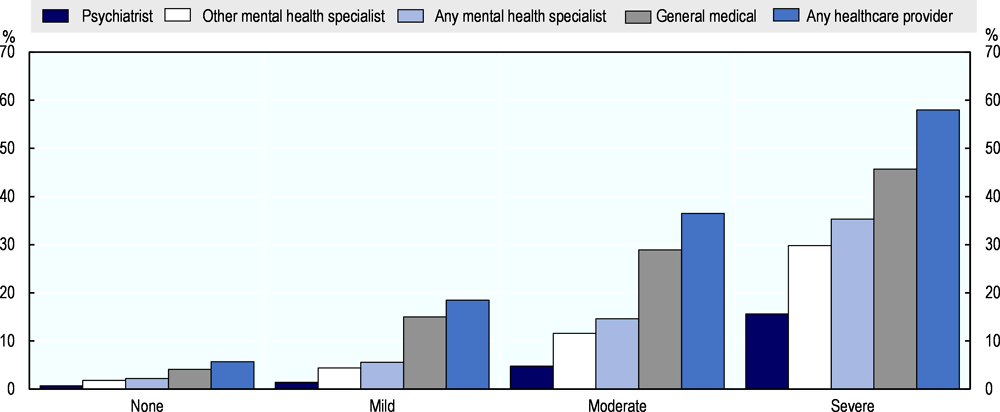

Te Rau Hinengaro found that of the people who met the threshold for a serious mental health condition, only 58% had a mental health visit within the last 12 months.2 Amongst people meeting the threshold for a moderate mental health condition, 36.5% had a mental health visit, and for people meeting the threshold for mild mental health conditions, this was 18.5%. Mental health visits include visits across specialist and general health services, with people with more severe mental health conditions having a higher use of both specialist and general health services (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3. Mental health visits vary by severity of mental health condition

Source: Oakley-Browne, M., Wells, J.E. and Scott, K.M., 2006. Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey: Summary. Ministry of Health.

Within these access rates, mental health visits were much lower for Māori and Pacific people. This difference cannot be explained purely by socio‑economic status, or severity of illness, but was also related to ethnicity itself (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4. Visits to health services for mental health reasons also vary across ethnic groups

Source: Oakley-Browne, M., Wells, J.E. and Scott, K.M., 2006. Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey: Summary. Ministry of Health.

A major challenge in supporting prevention and early intervention through primary care is that there is frequently a cost to the patient. This is in contrast to accessing specialist mental health services that are free for the patient. In 2017, the average fee for an adult (over 18 years), was NZD 34.79; compared to NZD 15.59 to attend what are known as Very Low Cost Access practices. Primary care is free to children below the age of 13. The current government announced in the 2018 budget that primary care visits would be free up to age 14 and is piloting funded counselling support for 18 to 25-year olds.

Whilst access rates to health services in relation to the population prevalence of mental health conditions are low, the actual numbers of people accessing specialist mental health services have increased from 2.3% of the population a decade ago, to 3.6% of the population in the last year. An increase from 143 000 people in 2011, to 174 000 people in 2017 (Ministry of Health, 2017[21]).

Funding for these specialist services has not grown at the same rate, and the effectiveness of the 3% ring-fenced budget for protecting DHB spending in specialist mental health and addictions services has also been questioned (Allan, 2018[10]).

Māori people have higher prevalence rates of mental health conditions than non-Māori people, they experience higher levels of unmet need, and when they do receive treatment, it is more likely to be through specialist acute services. For example, 6.1% of Māori people accessed mental health services in 2016, compared with 3.1% of non-Māori people. Māori people comprise 16% of the New Zealand population, yet account for 26% of mental health service users accessing specialist mental health and addiction services (Ministry of Health, 2017[21]). This raises the issue of needing different strategies to support Māori people experiencing mental health conditions. The opportunity to intervene early is a particularly missed opportunity for Māori people. Pacific people, people with disabilities and refugees also experience inequitable outcomes.

Culture and health are inter-twined. Health providers therefore need to be culturally as well as clinically competent (Pitama et al., 2007[22]). This is likely to include the use of cultural inputs within clinical practice: for example, the participation of whānau, the use of Te Reo Māori and a Māori workforce. Māori models of health and well-being are particularly important to understand and to build into practice to improve equity of health outcomes (Durie, 1997[23]) (see Box 2.3 for more details).

Data is available which shows waiting times for accessing specialist mental health and addiction services, suggesting that “78% of new clients saw mental health services within three weeks of referral, and 94% within eight weeks” (Ministry of Health, 2017[21]). The Peoples Mental Health Report collected more than 400 stories from people with experience of mental health conditions. A key theme emerging from the analysis was that people had difficultly accessing appropriate and timely mental health services, and for many they could not get assistance until “their health had deteriorated to a point of crisis” (Elliot, 2016[24]).

There are also a group of New Zealanders who experience moderate mental health needs, “who are not easily managed in primary care but do not meet the threshold for specialist care” (Ministry of Health, 2017[21]). This gap is confirmed by data on the take up of Primary Mental Health Services. In addition to the 3.5% of the adult population accessing specialist mental health and addiction services, in the year ending June 2016, Primary Mental Health Services saw 3.1% of the adult population. Together this figure is well below the 23% 12-month prevalence estimate of people experiencing mild‑to‑moderate mental health conditions (Allan, 2018[10]; Oakley Browne et al., 2006[20]).

Box 2.3. Māori and Pacific models of mental health and well-being

Māori health perspectives

One model for understanding Hauora Māori, which is now embedded in health policy, is Te Whare Tapa Whā, which was developed by Professor Sir Mason Durie (Durie, 1984[25]), to provide a Māori perspective on health. With strong foundations and four equal sides, the symbol of the wharenui (house) represents the four dimensions of Māori wellbeing: Taha tinana (physical health); Taha wairua (spiritual health); Taha Whānau (family health), and Taha hinengaro (mental health). All four dimensions are needed for good health and wellbeing. Te Whare Tapa Whā has become the conceptual framework to support practitioners across the health sector, including the mental health sector, to improve their engagement with Māori people.

Pacific health perspectives

Most Pacific people have a holistic view of health and wellbeing, which means all the aspects of life, physical, spiritual and mental wellbeing, should be in balance. In addition, the health of people with whom Pacific people have significant relationships is also very important. This includes family and spiritual deities. When disease and illness arise, they are interpreted as being related to a breach in a family relationship. Pacific people are therefore less likely to be trustful of unknown service providers and more likely to try to manage health issues within families, rather than accessing help.

Whānau Ora

Whānau Ora is an approach to delivering social services, particularly for Māori and Pacific families, launched in 2010. It is based on the Māori concept of wellbeing, aimed to have the various needs of a whānau met holistically. The aim is to empower whānau to determine their own goals and the means to achieve them, with the help of navigators and building on the strength of whānau. Whānau Ora is family-centred rather than service-centred. The focus is on integrated care and overcoming obstacles that impact on whānau wellbeing and development (Productivity Commission, 2015[26]). The aim of Whānau Ora is to have a strong focus on early intervention.

In 2013, the government devolved some of the planning and funding of social services to Whānau Ora commissioning agencies, these are non-government agencies. This is commissioning by Māori for Māori. NZD 50 million has been allocated over four years (Productivity Commission, 2015[26]). One of these commissioning agencies, Te Pou Matakana, has developed a social calculator tool to help identify the benefits of the Whānau Ora initiative compared to multiple government interventions.

In 2015 the OAG conducted an evaluation of Whānau Ora based on the first four years (OAG, 2015). The OAG reported that Whānau Ora is an innovation and represents new thinking in service delivery. More families are now better off as a result. “The government spending to achieve this has been small, but the importance for the whānau is significant”. The report highlights that delays in funding meant that some funds for whānau and providers did not reach them, and nearly a third of the total NZD 137.6 million was spent on administration (including research and evaluation). The report also calls for stronger support for Whānau Ora from other government agencies, particularly the MOH and the MSD.

These high levels of unmet need in primary care and increasing demand for specialist mental health services are likely to be the result of the rationing of Primary Mental Health Services. These services are also targeted to specific populations – Māori and Pacific people, and Community Service Care holders (Allan, 2018[10]).

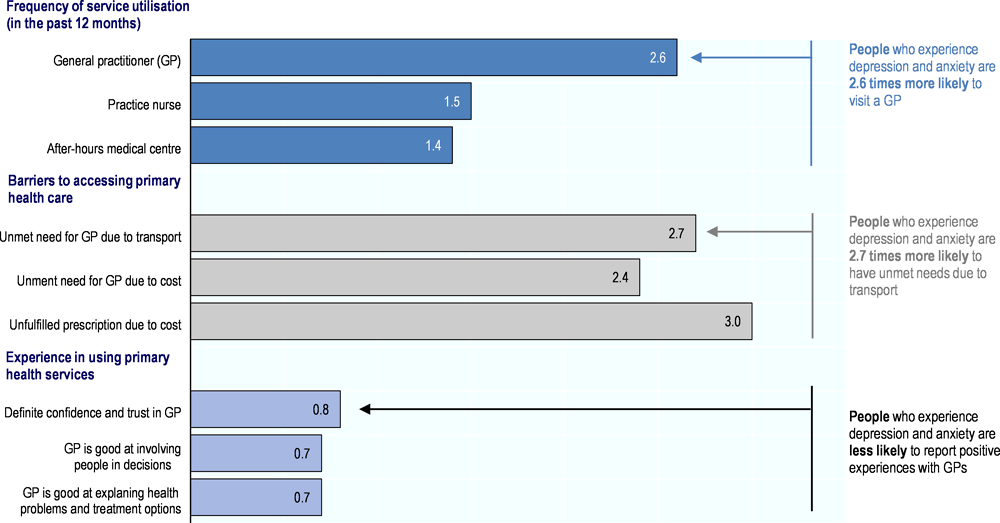

A recent analysis of the New Zealand Health Survey found that people diagnosed with anxiety and mood disorders were two to three times more likely to have an unmet need for primary care, despite higher GP utilisation, compared to people without a diagnosis. This unmet need was particularly due to cost and transport. The analysis which adjusted results for age, gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic status also found that people diagnosed with anxiety and mood disorders were less likely to report positive experiences with general practitioners (Lockett et al., 2018[27]) (Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. People with diagnosed anxiety and mood disorders are more likely to have an unmet need for primary care

Source: Te Pou (2018). Understanding health inequities using NZ data infographic. Available at: www.tepou.co.nz/resources/understanding-health-inequities-using-nz-data-infographic/871 Auckland: Te Pou o te Whakaaro Nui.

In the past few years, several reports have been written about the need to transform New Zealand’s response to mental health issues (Elliot, 2016[24]; Platform Trust & Te Pou, 2015[14]; Potter et al., 2017[28]). These reports call for new thinking and new organisation, building a holistic, people-centred resource and services; moving away from a focus only on treatment; and that treatment where it is provided should be recovery‑focused, non‑stigmatising, community-based and flexible. Reports also identified a special need to focus on Māori resilience and vulnerability and a special opportunity to learn and use the insights from mātauranga Māori more widely.

Interventions are often coming too late or may never come. The prevalence of mental health issues is far higher than the current capacity of service provision, and this therefore needs to be substantially increased (Potter et al., 2017[28]).

Prevention and early intervention can also occur in a number of settings outside of primary care, for example in public health and community settings. At a community level Māori providers of health and social services like Whānau Ora providers (for more details, see Box 2.3) could be a setting for early intervention. Staff could be trained and equipped with skills to use screening tools (e.g. Kessler for mental health, ASSIST for alcohol and drug use) to identify problems at an earlier stage and use brief interventions which could help to mitigate or lessen the problem.

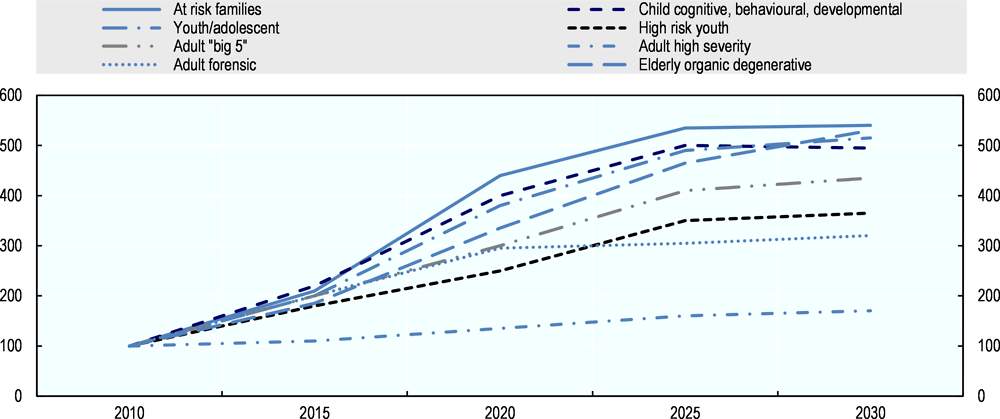

Towards the Next Wave (Mental Health and Addiction Service Workforce Review Working Group, 2011) predicted a significant rise in demand for services over the next 20 years (baseline year 2010) (Figure 2.6). On Track, the road map of actions to support providers, particularly non-government mental health and addiction service providers, to respond to this challenge, highlights that the most significant shift in services is needed in the areas of self-help and primary care (Platform Trust & Te Pou, 2015[14]).

Figure 2.6. The demand for mental health services is predicted to rise

In the organisation of services to respond to mental health issues, co-morbidities must also be taken into account. For example, 70% of people with a substance use disorder have a co-existing mental health issue (Ministry of Health, 2018[29]), and the prevalence of physical health issues is higher across all mental health diagnoses (Te Pou, 2014[30]; Lockett et al., 2018[27]; Oakley Browne et al., 2006[20]).

Co-morbidities are a significant issue for Māori people. Substance use disorders and physical health conditions are much more prevalent in Māori than in other ethnic groups. For example, the 12-month prevalence of substance use disorders, after controlling for age, sex, educational qualifications and household income, is 6% for Māori people, compared to 3.2% for Pacific, and 3% for other ethnic groups (Oakley Browne et al., 2006[20]).

Whilst this OECD report has sourced some data to assist with understanding mental health need and service access, there is an urgent need for comprehensive mental health data in New Zealand. This issue of both lack and quality of data has been identified by the Chief Science Advisors, specifically around mental health (Potter et al., 2017[28]), as well as across the health system more generally (OAG, 2013[31]).

Conducting a national mental health survey is a priority. This survey, unlike the 2006 survey, needs to gather data on labour force participation by severity of illness and diagnosis, and have a greater focus on understanding the experiences of groups of the population more at risk of mental health issues, and for whom current services are not being effective, or coming too late. There is also an urgent need for accurate data on the number of people receiving primary mental health services, the share of them transferred to secondary care, the number of people receiving psychological therapies, waiting times for such therapies, and employment status before/after treatment; to inform policy making in this area and monitor the impact of changes over time.

The New Zealand population has prevalence rates for mental health conditions similar to other OECD countries, but prevalence is higher amongst Māori and Pacific people. Many people with mental health conditions are not accessing any health services for their mental health needs, and for Māori and Pacific people, when they do access health services it is more likely to be specialist services. There is therefore a large unmet demand for mental health services, across primary, community and specialist services. Building the capacity of primary and community services for promotion and early intervention is essential to reduce the increasing demand for specialist services.

Pharmacology is still the main treatment offered for mental health conditions

In recent years, there has been an increasing emphasis on encouraging the use of non‑pharmacological interventions, particularly talking therapies and computer-delivered treatments (e-therapies) (Elliot, 2016[24]; Ministry of Health, 2012[16]; Potter et al., 2017[28]). Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand3 (bpacnz) guidance on the role of medicines in the management of depression in primary care states that non-pharmacological interventions are the mainstay of treatment for patients with depression, these include “cognitive behavioural therapy, relaxation techniques, social support, maintaining cultural or spiritual connections, regular exercise, healthy diet, sleep hygiene and addressing alcohol or drug intake”. The guidance recommends that: “medicines be reserved for patients with depression that is moderate to severe, or for those people who have not responded to non-pharmacological interventions” (bpac, 2017[32]).

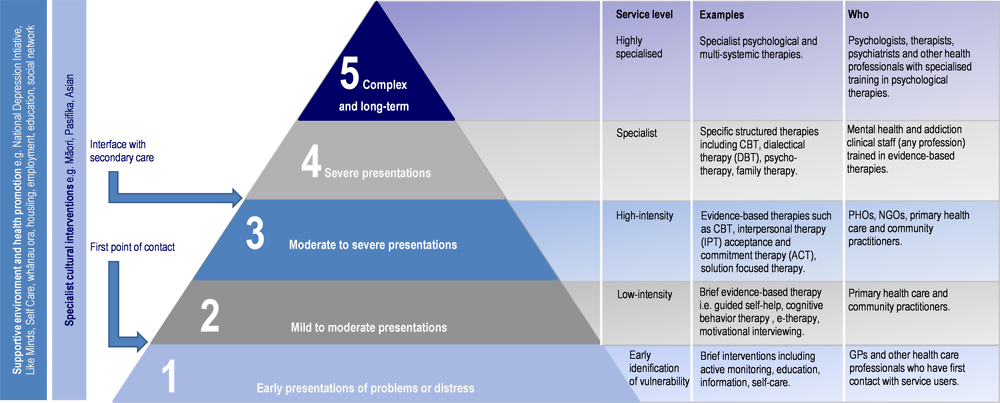

In 2015 the Let's get talking toolkit was launched to support primary care and secondary mental health and addiction services to deliver effective talking therapies, as part of a stepped care approach to treatment to ensure the right support and therapy is offered to the person at the right time (Te Pou, 2012[33]) (Figure 2.7). Another example are the recent PHARMAC seminars aimed at getting general practitioners to encourage patients to take up talking therapies, to get physically and socially active and monitor how this goes, before they prescribe.4

Figure 2.7. A model for the provision of stepped care

Source: Te Pou (2018), A stepped care approach to talking therapies. Available at www.tepou.co.nz/uploads/files/resource-assets/lets-get-talking-introduction-factsheet.pdf Auckland: Te Pou o te Whakaaro Nui.

However, delivery models and availability of psychological therapies nationally is inconsistent across the country, and across secondary and primary care, and a national‑driven strategy for the direction, consistency and equity of access of psychological therapies has been recommended. Experiences of national strategies overseas, most notably the UK's Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies Programme and Australia's Better Access to Allied Psychological Services component of the Better Outcomes in Mental Health Care programme show uptake increased and there were significant clinical outcomes for those who participated (Bassilios et al., 2013[34]).

Cost-benefit modelling by the University of Auckland, to explore the economic case for increasing access to psychological therapies in New Zealand primary care found that for every dollar spent in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, society could expect to receive NZD 15.19 in increased output and cost savings. In secondary services, where the duration of therapy would be longer and therefore costlier, the return was NZD 4.47 for every dollar spent (Te Pou, 2012[33]).

E-therapies, based on cognitive behavioural techniques are increasingly being made available in New Zealand, with online programmes such as The Journal (part of the National Depression Initiative), SPARX (aimed at young people), and Aunty Dee. The Journal collects routine data from users before, midway and after the sessions, based on responses to questions using PHQ-9. Data indicates that depression scores reduce for users who complete more than half the sessions, although findings from this routinely collected data should be interpreted with caution (KPMG, 2013[35]). A multi-centred randomised controlled trial of SPARX found that it was as effective as standard care for youths aged between 12 and 19 years seeking help for depression and equally effective across ethnic groups, gender and age. Better outcomes were found when people completed at least half the modules (Merry et al., 2012[36]). The authors recommended that SPARX could address some of the unmet demand for mental health treatment.

Whilst the initiation of these e-therapies is encouraging, there is concern that they are not as clearly linked to primary and community care as they could be, or targeted at sub-group populations, especially if compared to similar e-therapies in Australia (KPMG, 2013[35]). Further evaluation of the uptake, impact and effectiveness of these e‑therapies, and others that are developed and made available, is needed.

In 2015, the government amalgamated all health helpline telephone services under the new National Telehealth Service operating 24 hours day, 365 days a year. In June 2017, the “Need to talk?” service was launched as part of the National Telehealth Service specifically to provide a single number for mental health advice and support. The National Telehealth Service is linked to the National Depression Initiative.

At the same time as there have been initiatives to increase the availability of non‑pharmacological interventions, New Zealand prescribing data for anti-depressants shows a steady rise over the past 25 years, with scripts per 1 000 population more than tripling from 102/1 000 in 1993, to 376/1 000 in 2016.

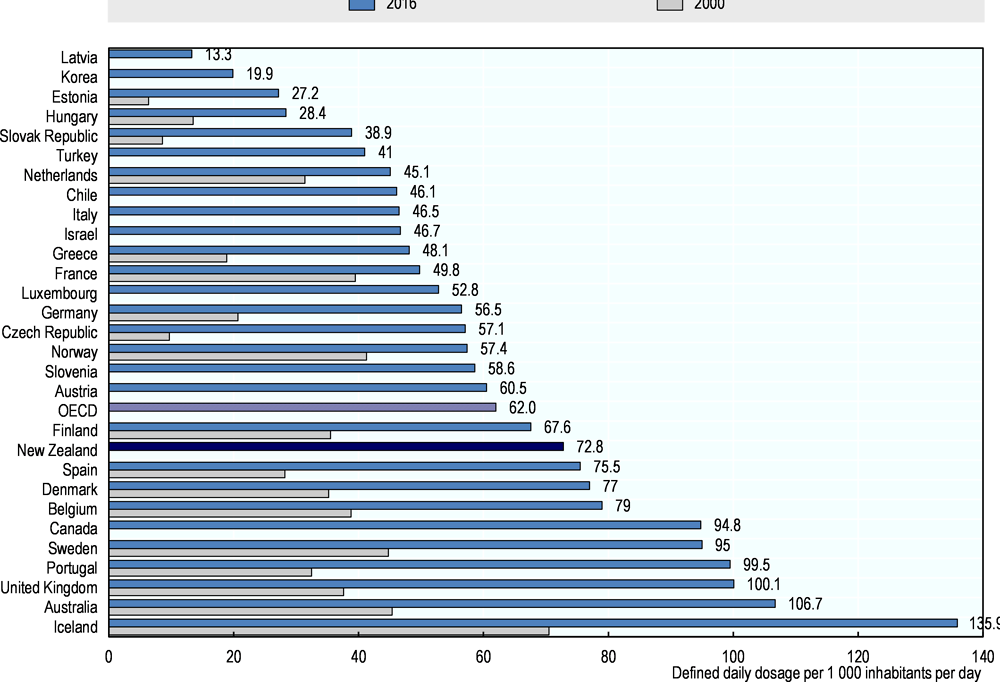

Data using the unit of measurement “Defined daily dosage (DDD) per 1 000 inhabitants (per day)”, enables comparison across countries. Figure 2.8 shows that consumption of anti-depressants in New Zealand is above average compared to other OECD countries, but still much lower than say, for example, Australia.

Figure 2.8. Consumption of anti-depressants in New Zealand is above the OECD average

Note: OECD is the unweighted average of the 29 countries in the chart.

a. Early data are 2001 for the Netherlands. Latest data are 2009 for France, 2014 for New Zealand and 2015 for Denmark and Greece.

Source: OECD Dataset: Pharmaceutical Market, http://stats.oecd.org//Index.aspx?QueryId=30135.

An important mechanism for increasing access to psychological therapies would be to remove the cap on spending for these therapies with the Primary Mental Health Services budget. The budget for spending on psychotropic medications does not appear to be capped in the same way. Currently people who can afford to pay, can access psychological therapies, but for those who cannot, they will depend on funded therapy, which is significantly limited. It is also important that there is increased access to e-therapies, but effectiveness of the therapies and their reach and effectiveness to groups at greater risk of mental health conditions needs monitoring.

Increasing access to talking therapies is an important cross-government priority not only in health policy, but in all policy areas covered in this report, namely education, workplaces and employment services too.

Strengthen the primary care workforce’s response to mental health needs

In most countries, GPs are the gatekeepers of mental health care. Patients, however, do not always directly present their complaints as mental health conditions, and therefore these conditions remain unidentified. GPs are not only gatekeepers of mental health care, but also the main providers of treatment for those with mild-to-moderate conditions. It is therefore essential that primary care teams, including GPs can recognise and respond to patients with mental health conditions.

As outlined earlier in the chapter, there are high levels of unmet need for primary care services, and there remain huge inequities of access especially for Māori and Pacific populations. Capitation payments based on, and which follow, the patient, as opposed to the primary care practice, to more accurately reimburse providers for patients with higher and more complex needs, have been recommended (Downs, 2017[9]). This is particularly important given the private business models operated within primary care.

Where people do access primary care services, it is estimated half have mental health conditions even if the condition may not be the reason for the visit (MaGPIe Research Group, 2003[37]). Most of these people will only see primary care teams for their mental health care (Lockett et al., 2018[27]).

The GP training curriculum developed and run by the RNZCGPs contains a training module on mental health. The aims of this module are to train GPs to diagnose, manage and treat mental health conditions, help patients to develop coping mechanisms and to demonstrate safe and competent prescribing. The training also aims to build GPs competency to participate in shared diagnosis and management of patients whose mental health conditions need specialist care input.

To improve the management of mental health issues in primary care, the RNZCGPs should review the proportion of the curriculum devoted to mental health to ensure this is commensurate with need. It should also develop a system for monitoring GP competency around mental health treatment and management. Given the significant inequities of access and treatment for Māori people, it is crucial that Māori models of mental health and wellbeing inform current and future GP training.

A New Zealand study, which examined the experience of general practitioners in relation to identifying and managing mental health conditions in primary care, identified that the assertion that GPs “miss” many psychological disorders is too simplistic (Dowell et al., 2009[38]). The study found that diagnosis of mental health conditions was related to previous consultation rates, with GPs non-recognition of mental health problems largely occurring among patients with little recent contact with the GP (MaGPIe Research Group, 2003[37]). The authors argue therefore that strategies that improve the continuity of care and target new or infrequent attenders to primary care may be more effective at supporting primary care identification than training and education alone.

A programme to build the competencies of primary care nurses in mental health and addiction has been available since 2012. The credentialing framework was developed by the New Zealand College of Mental Health Nurses (Te Ao Māramantanga). The framework provides primary care nurses with consistency of knowledge and skills to people experiencing mental health and addiction issues within primary care. Qualitative feedback from nurses who completed the programme was positive, with nurses reporting that it fills an important gap in their skills, knowledge and confidence.

Primary care organisations are also responding to the need to strengthen the mental health competencies and capacity of primary care. In 2016, Network 4, a collaboration of the four largest PHOs in New Zealand published Closing the Loop, to articulate a future vision for primary care-based mental health services. This called for better access, early intervention and developing a capable workforce.

There is also evidence in different regions of PHOs implementing new models of care to enhance primary mental health. For example, Kia Kaha based on the Stanford health coaching model aims to empower people with long-term conditions, including mental health conditions in the management of their condition. Peer health coaches as well as clinicians are employed. A two-year pilot in five general practice teams in Auckland is building on Kia Kaha. Health coaches and health improvement practitioners are part of the primary care team, as well as support workers from non‑government organisations. Mental health nurses, health psychologists, clinical psychologists and GPs have been trained on the behavioural health consultancy model from the United States. Practice improvements include formal connections with specialist mental health and addiction teams and improved access to talking therapies. Initial service evaluation shows 60% of patients presenting for mental health support are being seen on the same day. A formal evaluation is underway.

On the East coast of New Zealand’s North Island, an innovative partnership between the DHB, PHOs and local iwi has launched Te Kuwatawata to improve access to specialist mental health and addiction services, particularly for Māori people through a community focused, culturally informed single point of access. New premises in the community have been sourced, moving away from one‑to-one clinician based meetings and taking a group approach to providing services.

Te Hikuwai (Resources for wellbeing) has recently been launched as a resource to support primary care practitioners in the early identification and treatment of mental health and addiction problems in adults. It is part of the Let’s get talking toolkit and based on the evidence that brief interventions can improve people’s wellbeing by preventing mild issues from becoming worse. Te Hikuwai has 20 topics related to mental health and addiction problems, wellbeing prescriptions and self-help resources for patients to take away. It is aimed at supporting primary care practitioners to deliver levels 1 and 2 of a stepped care approach. Uptake of the resource is being encouraged across all PHOs, following a trial in Northland primary care services in 2016. Since then, four further regions have adopted it.

Other OECD countries have been developing ways to increase the mental health specialist advice available in primary care. In Australia, the Mental Health Nurses Incentive programme funded GPs to hire mental health nurses (OECD, 2015[13]). This was found to not just improve mental health symptoms, but equally so participation in employment. Similarly, the Netherlands brought additional clinical expertise into general practices through mental health nurses, psychologists and social workers, and corresponding financial incentives for GPs to involve these professionals (OECD, 2014[39]).

Given that prevalence and access rates vary across ethnic groups, culturally‑informed and culturally-led initiatives are needed. Whilst for many people presenting with mental health symptoms, the GP is likely to be an important first contact, for others the GP will not be. It is therefore important to understand and engage with other people and organisations who will be a first contact point. For example, Le Va, the Pacific workforce and information centre for mental health and addiction, has been reaching out to sports leaders and sports coaches, along with church leaders. This is because they recognise that for many Pacific people these groups will be the first contact when signs of distress are showing.

The primary care funding structure needs to work for primary care to provide mental health care, especially for those people with significant needs that, however, do not meet the threshold for specialist services. The funding structure also needs to include time for primary care to have conversations with patients about taking up work, or returning to employment.

The health workforce also needs to reflect the diversity of the people who contact mental health services across primary and secondary services. Data on the ethnicity of staff working in specialist mental health and addiction services shows that Māori staff significantly underrepresent mental health and addiction service users: 9% of staff identify as Māori, whereas Māori people comprise 23% of service users (Te Pou, 2017[40]). The under-representation of Māori and Pacific people in the health workforce is an important issue that needs addressing, as does the cultural competency of the primary care workforce. Evidence shows that access to services improves for indigenous communities when the workforce reflects the local community. Workforce diversity and cultural competency is therefore particularly important for mental health services due to the high prevalence of mental health issues among Māori and Pacific communities (Ministry of Health, 2018[29]).

The communication between primary care and specialist mental health services has been an area that has also been highlighted repeatedly as needing improvement. National guidance and the emerging models of care both need to ensure this communication issue is addressed, and formal mechanisms established.

Address sickness absence issues through primary care

There is a vast body of evidence showing that people with mental ill-health are one of the highest risk groups for long-term sickness absence (OECD, 2015[1]). “GPs need to be knowledgeable about the impact of work on mental health, and vice versa, given that they are generally responsible for certifying sickness and that most people with mental health conditions are treated by their GP”. A common misconception among GPs, and health care providers in general, is that people with mental ill-health need to be cured before they can return to work. However, long absences from work increase the risk of permanent work disability (Koning, 2004[41]). Timely return to work is therefore paramount.

New Zealand primary care teams need to be knowledgeable about the impact of work on mental health and vice-versa given that most people with mental health conditions who seek treatment will see only their GP or practice nurse. Whilst New Zealand does not collect national data on sickness absence, overseas data shows that people with mental health conditions are more likely to be taking sick leave and that the average absence is longer (OECD, 2015[1]). In New Zealand GPs are the main health professional certifying sickness absence and incapacity to work.

The GP curriculum developed and run by the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners contains a training module on health and work, introduced in 2012. The competencies included in the health and work module include being able to:

communicate and negotiate with patients on creating rehabilitation and return‑to‑work plans;

develop an awareness of, and show the ability to complete, certification documents to communicate opinion accurately;

take an accurate occupational history;

assess fitness to work;

understand the principles of rehabilitation relating to physical, psychological, social, recreational and cultural needs;

develop and maintain up-to-date knowledge of the impact of joblessness on health;

recognise the impact of long-term health conditions on work capacity and the role of interventions for minimising disability;

understand the biopsychosocial model of illness and disease and its relevance in assessing fitness for work;

identify ways of supporting Māori in their workplace and back into work, reducing inequities that will have an impact on health outcomes.

Whilst it is encouraging to see this curriculum development, stronger links could be made between the RNZCGP’s mental health module and the health and work module. The interrelationship of mental health and work appears to be absent from the mental health module, and mental health appears to be absent from the health and work module. It is also important that the health and work module is a compulsory element of training and that RNZCGP finds ways to provide comparable upskilling to GPs who qualified prior to the health and work module being initiated.

Web-based information portals for health practitioners, designed for use at point of care, primarily for general practitioners are used in many parts of the country, these include Health Pathways and Map of Medicine. Whilst the depression and anxiety pathways mention return to work, information is limited. Similarly, the pathways on work assessment and rehabilitation contain limited, if any, information about mental health. Specific information and guidance on return to work and managing sickness absence / return to work consultations in primary care should be developed and included.

Training and continuing professional development for GPs and other primary care practitioners is also developed and delivered by PHOs, and through some Universities, such as the Goodfellow Unit within the University of Auckland. These offer important platforms from which to provide training to the primary care workforce to enhance knowledge about work, return to work, the link between mental health and work, and preparing meaningful medical certifications.

There is an absence of any national guidelines or training on return to work practices and managing sickness absence. For example online decision support tools, such as Health Pathways, where the treatment pathways for depression and anxiety refer to return to work, could be considerably strengthened to include recommended guidance for health practitioners to manage sickness absence and mental health and work conversations. In Sweden, for example the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare developed and published illness-specific guidelines for about 100 major illnesses, including many mental health conditions, which included anticipated return to work outcomes, and average sickness absence time periods. An evaluation found that 76% of GPs were using the guidelines and that duration of sickness absence was reduced. Similarly, the Netherlands also developed national guidelines to help GPs discuss sickness absence and plan and support return to work, or commencement of work. These guidelines included information on other agencies to involve (OECD, 2015[1]).

Collaborative work between the Canterbury Chamber of Commerce, employers and Pegasus Health PHO aims to strengthen the links between primary care and local employers, and support better management of employee sickness absence.

Increase the employment focus of the health system: scale up promising pilots

Clinical treatment alone does not produce good work outcomes for people with mental health conditions. Research has consistently identified that the provision of health care treatment, such as psychological therapy, in itself does not affect work outcomes (Waddell, Burton and Kendall, 2008[42]). What has a proven effect is coordinating employment support with mental health treatment (Lagerveld et al., 2012[43]; Drake and Bond, 2017[44]). For people on sick leave, ensuring health treatments are work‑focused is particularly important. Therapy should focus on job-related issues and incorporate job issues early on: the workplace should become one of the foci for improving a person’s mental outlook, while employees are encouraged to develop a return-to-work plan. This approach has been found to be more effective than standard cognitive behavioural therapy at supporting a return to work (Cullen et al., 2018[45]). Furthermore, people with mental health conditions who are in work have better outcomes with respect to treatment take-up, duration, and costs than those who are unemployed or inactive (OECD, 2015[1]).

Whilst the New Zealand Health Strategy (Ministry of Health, 2016[15]), and the most recent mental health service development plan, Rising to the Challenge (Ministry of Health, 2012[16]) give some recognition to the importance of employment in health care, there is no mention of return to employment as an important outcome and performance measure for health services. There is also an absence of any detail on who is responsible for providing employment support services or how this should be delivered. As a result, the purchasing and provision of employment support is left to the decision of local funders and service providers (Lockett, Waghorn and Kydd, 2018[46]). Consequently, there is a lack of national consistency in supporting people with mental health conditions into employment. There is also a lack of clarity of the roles and responsibilities of the health workforce in relation to supporting people to find work, return to work, and stay in work.

The lack of focus on employment in the health system is further highlighted in the Ministry of Health's 2017 Briefing to the Incoming Minister. Whilst in this briefing the relationship of employment to health is acknowledged, it is described as a determinant of health “which is outside the health system” (Ministry of Health, 2017[12]). There is also no recognition of the two-way relationship between mental health and work, particularly the impact of a mental health condition on subsequent labour force participation.

Regional health strategies are showing more activity around employment than national policy. Two DHBs have worked together with local non-government organisations to develop Everyone’s Business, a mental health and employment strategy for the region. The strategy outlines how the region will move to improving the labour force participation of people with mental health conditions, and commitment to implementing the strategy is outlined in the DHBs annual delivery plans. Likewise, the importance of employment for sustained health and wellbeing is recognised in the DHBs five-year strategic plan (Waitemata, 2016[47]). Employment is one of the top three areas for strategic and ground level partnerships. They also propose to measure employment as a marker of improvements in access to mental health treatment.

Employment services integrated with mental health and addiction services aligning with the principles of the Individual Placement and Support evidence‑based practices are being delivered in seven DHB regions, and about to commence in two more (Drake and Bond, 2017[44]; Lockett, Waghorn and Kydd, 2018[46]). However, even where IPS is available, access is limited to only some community mental health centres, and not yet linked into specialist mental health services, such as the Māori and Pacific mental health teams and the early intervention in psychosis teams. In other regions, one full-time employment specialist serves the equivalent of three community mental health teams, which produces a diluted service that cannot coordinate effectively employment support with clinical care (Lockett et al., 2018b). IPS services up until recently have been funded through health dollars with two newly established IPS services funded by MSD in 2017 (see Chapter 5).

Like in other countries, IPS programmes in New Zealand have been found to be effective (Porteous and Waghorn, 2007[48]; Browne et al., 2009[49]; Waghorn, Stephenson and Browne, 2011[50]) and to benefit from an integration of services between non‑government employment organisations and public mental health and addiction services through the provision of implementation support and technical assistance. Implementation support can include training clinicians on how to have work conversations and to include vocational aspirations as a routine part of assessment and treatment planning. In a recent pilot, the provision of implementation support more than doubled the referrals to employment services, improved fidelity to IPS, increased the reach of the employment services, and strengthened employment outcomes (Te Pou, 2017[51]).

New Zealand also led the development of the Employment and Mental Health Option Grid, an evidence-based decision-making tool to help all health practitioners to have work‑focused health conversations. However, the uptake and utility of the grid has not been evaluated yet (Reed and Kalaga, 2018[52]).

There have also been a number of pilots to increase the employment focus of primary care but pilots are short-term and small scale. Those working directly in primary care teams are showing promising results (see Chapter 5).

In 2016, RANZCP issued updated clinical guidance on the management of psychosis and schizophrenia. The importance of increasing access to employment services through the inclusion of employment specialists in mental health teams is a key recommendation (Galletly et al., 2016[53]). In contrast, the BPACNZ management of depression guidance does not mention employment at all. The most recent RANZCP guidance on the management of mood disorders has one mention of employment and housing in the management of major depressive disorder (Malhi et al., 2015), but does not include any of the evidence on the efficacy of employment support integrated in mental health services.

Anecdotal accounts of primary care’s understanding and utilisation of the links between health and employment services in relation to injury are prevalent through their experience of working with ACC. ACC provides a range of supports to primary care including treatment and vocational rehabilitation services for patients with ACC claims, as well as online and telephone advice for health practitioners. One ACC vocational rehabilitation service includes Stay at Work which take a team-based approach working with the person, their whānau, the GP and other health practitioners, the employer, and a rehabilitation provider. This approach should be extended to people with mental health conditions and the understanding of the interrelationship between health and work that it has no doubt stimulated in primary care, can then be utilised for mental health as well as injury.

New Zealand needs to build a comprehensive programme of national access to integrated psychological therapies and employment support. This could offer different approaches, for example e-therapy with employment support. Programme design and delivery needs to be led by the communities to which they are targeted.

Conclusion

In 1999, the Mental Health Commission published a discussion paper on issues and opportunities in employment and mental health, in order to improve the employment responses for people who experience mental health conditions and addiction (Mental Health Commission, 1999[54]). This paper called for an “integrated public policy response” across mental health, labour market and income support policies and highlighted the lack of information on the “needs, numbers and trends” of people with mental health conditions seeking employment and the lacking “coordination between mental health and employment services”. It also concluded that “there appears to be no overarching policy framework and responsibilities are split between a number of Government agencies”.

Nineteen years on, the situation appears not to have changed enough. Much of the lack of change is likely to be explained by the complexity and fragmentation of the health system, coupled with an underinvestment in mental health services and primary care services over many years. However, work is underway to strengthen the models of care in primary care to respond more effectively to people presenting with mental health conditions, and to increase access to psychological therapy and employment support.

New Zealand’s sustained national awareness and anti-discrimination programmes, which are now focusing on health care settings and workplaces, offer a good platform from which to strengthen the employment focus of mental health care.

Whilst mental health care remains strongly focused on specialist services and reliant on pharmacological treatments this will severely limit the system’s ability to support job retention, increase return-to-work rates, and improve labour force participation more generally for people with mental health conditions.

Greater access to psychological treatments, including e-therapies is developed. The scale up of these programmes provides a good opportunity to integrate them with employment support services and to strengthen the links between mental health care and work.

Primary and community health practitioners are innovating new models of care, and culturally informed programmes and support services. As these are grown, and the mental health capacity of primary care strengthened, this is the ideal time to build in training and guidelines around mental health and work, particularly around managing sickness absence and supporting return to or take up, of work.

The presence of ACC has developed and strengthened the employment focus of the health insurance system for injury, but it has also created a two-tier health system where access to treatment and vocational rehabilitation is prioritised for injury and not for illness.

References

[10] Allan, K. (2018), New Zealand’s mental health and addiction services – The monitoring and advocacy report of the Mental Health Commissioner, Office of the Health and Disability Commissioner, Wellington, https://www.hdc.org.nz/media/4688/mental-health-commissioners-monitoring-and-advocacy-report-2018.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2018).

[34] Bassilios, B. et al. (2013), Evaluating the Access to Allied Psychological Services (ATAPS) component of the Better Outcomes in Mental Health Care (BOiMHC) program: Ten year consolidated ATAPS evaluation report, Centre for Mental Health, The University of Melbourne, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275518921_Evaluating_the_Access_to_Allied_Psychological_Services_ATAPS_component_of_the_Better_Outcomes_in_Mental_Health_Care_BOiMHC_program_Ten_year_consolidated_ATAPS_evaluation_report (accessed on 28 October 2018).

[32] bpac (2017), The role of medicines in the management of depression in primary care, bpac better medicine, Dunedin, http://www.bpac.org.nz (accessed on 28 October 2018).

[49] Browne, D. et al. (2009), “Developing high performing employment services for people with mental illness”, International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, Vol. 16/9, pp. 502-511, http://dx.doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2009.16.9.43769.

[45] Cullen, K. et al. (2018), “Effectiveness of Workplace Interventions in Return-to-Work for Musculoskeletal, Pain-Related and Mental Health Conditions: An Update of the Evidence and Messages for Practitioners”, Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, Vol. 28/1, pp. 1-15, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10926-016-9690-x.