This chapter evaluates policies and programmes aimed at promoting the mental health of New Zealand’s children and youth. The analysis looks at five questions in particular: How does New Zealand’s education system promote mental wellbeing and psychological resilience? In what ways do schools intervene when warning signs emerge? What mental health services may young people access through the health care and community system? How do schools and universities stem disengagement and attrition from the education system? What policies and programmes are in place to help vulnerable young people transition into further education or into employment? The analysis uses the OECD’s (2015) Council Recommendation on Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policy as the primary benchmark for best practices in this field.

Mental Health and Work: New Zealand

Chapter 3. Mental resilience and labour market transitions of youth in New Zealand

Abstract

Introduction

Policy aimed at investing in a mentally healthy workforce needs to include a focus on the young generation given that 50% of all mental health conditions start before the age of 14 (OECD, 2015[1]). The formative years are a critical time to stimulate self‑understanding, emotional maturity and psychological resilience. The ability of primary, secondary and tertiary education institutions to ensure mental wellbeing among their students factors strongly into countries’ capabilities around skills development and, ultimately, the fulfilment of economic potential. As the average time to first treatment of mental health conditions runs up to 12 years after onset, children and adolescents are unlikely to get into contact with mental health services unless the impact of the condition becomes serious. The education system has an important role in providing early support for those who show signs of mental health conditions at an early age.

Good educational attainment is essential for a successful transition into the labour market, but children and adolescents who experience mental ill-health are less likely to engage fully in school; less likely to achieve well in their qualifications; and consequently less likely to progress into a fulfilling career. School policies are needed that focus on supporting this group. Not only for young people with severe mental health conditions, for whom some policy is often in place, but especially so for the majority of young people with mild and moderate mental health problems who often are not eligible for specialised health, social and educational support.

Research has shown that youth in New Zealand often struggle with mental health issues. According to the Youth 2000 Study, surveying 10 000 secondary school pupils from across New Zealand , 16% of boys and 9% of girls reported clinically significant symptoms of depression; 8% and 29%, respectively, admitted deliberate self-harm in the past 12 months; 10% and 21% serious thoughts about suicide; and 2% and 6% suicide attempts (Clark et al., 2013[2]). The suicide rate for 15‑19 year old New Zealand ers in 2013 was 18 per 100 000 compared to 7.4 per 100 000 on average for all OECD countries (OECD, 2017[3]). This accounted for 35% of all deaths in this age group. Like many other social and health outcomes, suicide rates in New Zealand vary starkly by ethnic group: Māori males aged 15‑19 years are almost three times more likely to commit suicide than their peers of European ethnicity and Māori females even six times, with suicide rates generally being significantly higher among males than females (Ministry of Health, 2016[4]).

Research has also shown a strong link between child and youth mental health and poverty, concluding that a mental health strategy for children should sit alongside a comprehensive programme to alleviate poverty (Gibson et al., 2017[5]). This is an important aspect but going beyond the remit of this chapter. Increased resources in low-income can reduce anxiety, stress and depression, irrespective of age (Cooper and Stewart, 2015[6]).

The main challenges for youth and education policies

The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policy calls upon its member countries to: “seek to improve educational outcomes and transitions into further and higher education and the labour market of young people living with mental health conditions”, detailing key priorities for action policy makers should consider (OECD, 2015[7]).

Table 3.1 gives an assessment of New Zealand’s performance in each of these policy areas and provides corresponding policy recommendations. In summary:

Table 3.1. New Zealand’s performance regarding the OECD Council Recommendations around improving educational outcomes and labour market transitions for young people

|

OECD Council Recommendation |

New Zealand’s performance |

Suggested actions |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

A |

Monitor and improve the overall school climate to promote social‑emotional learning, mental health and wellbeing of all children and youth through whole-of-school-based interventions and the prevention of mental stress and bullying. |

Strong focus in schools on positive mental health and resilience and strong well-being commitment in the school curriculum. Strong focus on managing behaviour, e.g. through the Positive Behaviour for Learning (PB4L) initiative. B4 School Check to detect problems early. Additional learning support for vulnerable students through Ongoing Resourcing Scheme and Resource Teachers: Learning & Behaviour. |

Ensure every child can benefit from the available support by increasing take-up of PB4L School-Wide, and tailoring services and guidelines to vulnerable schools and groups of students. Increase the attention to mental health and bullying prevention in existing programmes. Use “B4 School Check” to identify emotional issues or barriers. |

|

B |

Improve awareness among education professionals and the families of students, of mental health conditions young people may experience and the ability to identify problems, while ensuring an adequate number of qualified professionals is available to all educational institutions. |

Wide range of mental health training packages and guidance materials for both schools and families; the reach and impact of this training however is unclear. Significant focus on school-based health services, including nurses and counsellors. Youth Mental Health Project introduced and expanded various assessment tools (e.g. HEADS screening tool) and initiatives, which are showing good outcomes. |

Stimulate the use of training and guidance materials and introduce mental health as mandatory element in the teacher curriculum. Expand funding for school-based health services (minimum service standards; on-site health teams; lower caseloads per counsellor; expansion to primary schools). Use change in funding formula to secure funding for health services. |

|

C |

Promote timely access to co‑ordinated, non-stigmatising support for children and youth with mental health conditions by better linking primary and mental health services and by an easily accessible non-clinical support structure, which provides comprehensive assistance. |

Youth Primary Mental Health Services (YPMHS) upscale primary care for early intervention, and reach out to Māori youth. Relatively high use of secondary mental health care among children and youth, but also long waiting times. Strong structure of Youth One Stop Shops (YOSS) with a focus on integrated services for youth aged 10‑25 years. |

Secure and expand YPMHS funding. Move to stepped-care service model with easy access and referral. Try out integration of primary and secondary youth health services. Secure YOSS funding and expand its counselling capacity. Better integrate YPMHS with YOSS. |

|

D |

Invest in the prevention of early school leaving at all ages and support for school-leavers living with mental health conditions, with a view to reconnect those students with the education system and labour market. |

Large inequality in education outcomes, high attrition from tertiary education, and poor outcomes for the NEET population. Effective support for potential school leavers through the Attendance Service. Various alternative learning pathways. |

Ensure that alternative pathways are providing high-quality support. Prioritise support for Māori youth. Better link programmes targeted to potential school leavers with other youth services, such as YOSS, Youthline and YPMHS. |

|

E |

Provide non-stigmatising support for the transition from school to higher education and work for students with mental health problems through well-integrated services. |

Range of initiatives under the Youth Guarantee to widen learning options and improve transition into employment. Youth Service (under Work and Income) targeted at NEETs and beneficiaries. |

Expand Youth Guarantee initiatives with good outcomes and secure the same outcomes for Māori youth. Strengthen Youth Service monitoring and evaluation and strengthen the link with education institutions. |

Source: Authors’ own assessment based on all of the evidence collected in this chapter.

New Zealand’seducation system has a strong focus on positive mental health and well‑being and provides considerable resources for i) additional learning support for vulnerable pupils and ii) managing undesirable behaviour. Education outcomes, however, remain highly unequal suggesting that disadvantaged schools and groups of students are not able to benefit sufficiently from the approach taken and the resources provided.

New Zealand offers various mental health trainings to schools and families and is very aware of the need to provide school-based health services and to identify problems early on. In effect, however, not all schools have effective on-site health and mental health services in place, and the available number of health professionals is insufficient. Owing to schools’ autonomy, there are no minimum requirements, which all schools would have to follow. National policy should strengthen the availability and consistency of school‑based mental health training and services across the country. Resources need allocating according to need and a particular focus on Māori youth.

Use of specialised mental health care is high among New Zealand youth whereas primary mental health services are under-resourced despite recent efforts to up-scale primary care for prevention and early intervention. Youth One Stop shops are an exemplary service, which is easily accessible and provides all-inclusive supports; but resources are insufficient to satisfy the demand and the connection with other services is still insufficient.

New Zealand pays much attention to the prevention of early school leaving, through an effective Attendance Service, and provides a range of alternative learning pathways to help students back into school or complete education. Māori youth are highly over-represented in all these pathways, which, however, produce much poorer outcomes than regular schools, and would benefit from stronger links with other youth services.

New Zealand offers a number of initiatives under its Youth Guarantee that aim to improve the transition into further education and/or employment, predominantly by making the curriculum more relevant, including through vocationally focused and workplace-based learning opportunities. So far, however, these programmes have failed to help more Māori youth into employment. Many of them end up in the Youth Service, targeted at NEETs and people in receipt of youth payments but with limited evidence on its effectiveness.

Mental wellbeing in school

New Zealand’s education system has a strong commitment to nurturing mental wellbeing and enhancing the resilience of young people. It is ahead of some other OECD countries with concepts of wellbeing and positive mental health built into the curriculum and by having in place strong institutions for detecting and responding to potential signs of behavioural or psychological needs among learners. The evidence gathered suggests New Zealand has set up multiple promising initiatives in this area. The main challenge is to ensure every child and youth can benefit from the strength of the system, irrespective of social background, location and ethnicity, which in turn requires adequate tailoring to vulnerable schools and groups of students.

Wellbeing is in the curriculum but some schools struggle with implementation

Laws in New Zealand mandate schools to ensure pupils’ wellbeing. This includes a focus on students’ satisfaction with life at school, their engagement with learning and their social‑emotional behaviour. Student wellbeing is defined as a sustainable state, characterised by predominantly positive feelings and attitude, positive relationships at school, resilience, self-optimism and a high level of satisfaction with learning experiences (Education Review Office, 2013[8]). New Zealand’s Education Council maintains a strict professional code and key criteria for registered school teachers, formally committing them to promoting pupils’ wellbeing on five key fronts: physical, emotional, social, intellectual and spiritual. A set of National Administration Guidelines formally mandate schools’ management boards to maintain safe physical and emotional environments.

Above all, mental wellbeing, socio-emotional development and psychological resilience are mainstreamed nationally through New Zealand’s school curriculum. The primary and secondary curriculum adopts an explicit focus on five “key competencies” all pupils are expected to develop during their compulsory education: thinking; using language, symbols and texts; managing self; relating to others; and participating and contributing (Ministry of Education, 2017[9]). Tertiary education providers likewise adopt a parallel set of key competencies around thinking; using tools interactively; acting autonomously; and operating in social groups (Hipkins, 2006[10]).1 Nurturing these key competencies is both a means towards improving learning outcomes and a valuable end in itself (Ministry of Education, 2007[11]). Ultimately, the key competencies also ensure a clear focus is maintained within the education system on positive mental health and a clearer understanding of emotions and cognition.2

New Zealand’s coherent policies and practices in this area are borne out in the available data on school teachers’ and families’ perceptions around children’s wellbeing at school. In a national survey carried out in 2016 by the New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER), the large majority of the surveyed teachers felt their school effectively supported pupils’ wellbeing and sense of belonging (85%) and taught emotional skills assertively (86%). Surveyed family members felt equally positively that the school environment promoted wellbeing, a sense of belonging and psychological resilience, with only 2‑3% disagreeing on these points (Boyd, Bonne and Berg, 2017[12]).

In 2012, the Education Review Office (ERO) carried out an evaluation of wellbeing practices in primary and lower-secondary schools.3 ERO’s findings categorised the schools into five broad categories (Education Review Office, 2015[13]):

11% managed to promote an “extensive focus on student wellbeing” throughout all their activities

18% promoted wellbeing well within their own curriculum and response systems

48% promoted wellbeing only reasonably well, predominantly relying on a positive atmosphere and respectful relationships to achieve good outcomes

20% made rather limited use of wellbeing promotion techniques, focusing predominantly on managing bad behaviour

3% were “overwhelmed by wellbeing issues”, with few concrete activities manifesting in high staff turnover, low capacity for improvement, unclear values, weak trust and a deep-set dependence on outside support.

Thus, despite the strong focus on pupils’ wellbeing in the national curriculum, only 28% of all schools managed to perform satisfactorily and almost a quarter (23%) was unable to integrate wellbeing in their curriculum. Although ERO has developed more detailed guidelines for schools to improve their performance along the desired lines and to engage in effective self-evaluation (Education Review Office, 2016[14]), it would be important to profile the schools struggling with integrating wellbeing initiatives. For example, it would be relevant to know whether schools in more remote areas (potentially having more difficulty with attracting extra services focusing on wellbeing) or with more students with socio‑economic disadvantages who face a high risk of developing mental health and social problems belong to the 23% performing poorly. ERO could use such information to tailor guidelines to the challenges that schools performing poorly specifically face.

A focus on managing behaviour but limited attention on preventing bullying

Misbehaviour in school is a significant detriment to learning environments. Behaviours like bullying (including cyber-bullying) can also directly affect pupils’ mental wellbeing and feelings of belonging and security. The relative success or failure schools encounter in managing pupils’ behaviour can therefore have a significant impact on pupils’ overall wellbeing and learning outcomes.

The Ministry of Education undertakes a range of activities to help schools better manage behaviour. Since 2009, its efforts have converged under the Positive Behaviour for Learning (PB4L) initiative. The initiative’s flagship scheme is PB4L School-Wide – a structured framework to help schools understand and shape the ways in which their environments, rules and practices influence pupils’ behavioural choices.

New Zealand’s government formally evaluated PB4L School-Wide in 2015. The analysis found that schools using the framework issued fewer formal punishments (like school stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions or expulsions) to pupils; experienced less disruption in class; and reported increases in pupils’ concentration and engagement. However, programme uptake is still low, with only 780 schools – roughly one in three schools across New Zealand – currently applying PB4L School-Wide.

The Ministry of Education also provides a range of specific interventions for schools to draw upon in particularly challenging cases. Behaviour Services and Support, for example, provides a local pool of specialists who can work with school-aged children alongside their teachers and family members in cases of extreme behavioural difficulties. Schools may engage such specialists to work with pupils alongside their families, school staff and external specialists to tailor an individualised learning support plan.

Failing all of these interventions, schools are also empowered to issue formal disciplinary measures or, in the worst case, remove a pupil under particularly disruptive circumstances.4 The Ministry of Education closely monitors such outcomes and responds to requests for support. Administrative data show that the incidence of suspensions decreased by around 50% between 2000 and 2016, from an age-standardised rate of 7.4 suspensions per 1 000 pupils per year to just 3.6 (Ministry of Education, 2018[15]). The number of exclusions and expulsions has declined at a similar rate, suggesting that support measures available for schools and students in difficulties have been successful in keeping more students in class and in school. Stand-downs, the lowest degree of a formal disciplinary measure, declined from 24.4 to 20.6 per 1 000 pupils per year over the same period. All disciplinary measures affect Pasifika youth somewhat more often and Māori youth much more often than students from other ethnicities. However, the rate of decline was also largest among Māori youth, resulting in some convergence in outcomes and suggesting that available measures have started to reduce ethnic inequalities.5

Specific attention for mental health and for the prevention of bullying seems to be missing in these programmes and interventions. They are geared towards stimulating adequate classroom behaviour among pupils, but bullying is often more covert and conducted outside classrooms. This is worrisome given that the most recent data from the OECD’s PISA study reveal high levels of bullying in New Zealand’s schools. In 2015, 26% of pupils reported experiencing at least one of the six bullying behaviours a few times a month – the second‑highest share among all OECD countries and significantly above the OECD average of below 19% (OECD, 2017[16]).

There are a number of initiatives aimed at preventing bullying behaviour, but these are not sufficiently supported by a clear policy on bullying for schools coming from the Ministry of Education. For example, the Mental Health Foundation organises the annual Pink Shirt Day since 2009, delivering coordinated activities in schools and workplaces to end bullying and celebrate diversity. Other initiatives focusing on bullying prevention in schools are organised by KiVa New Zealand and Bullying-free NZ.

Potentially more promising could be the PB4L Restorative Practice initiative, which provides a framework to help schools foster positive relationships, based on values of fairness, dignity, mana and universal potential. This includes a focus on relational and problem-solving skills among pupils, which may affect bullying behaviour. However, uptake of PB4L Restorative Practice is even lower than PB4L School-Wide; currently only around 180 schools across New Zealand use the programme. A formal evaluation of PB4L Restorative Practice is underway. It would be advisable to also regularly measure (changes in) bullying behaviour among pupils.6

Additional learning support for vulnerable students

New Zealand has highly robust institutions in place for identifying developmental or behavioural difficulties early on and, in turn, providing additional learning support.

New Zealand’s Ministry of Health undertakes a mandatory B4 School Check (read as: before-school check) to examine the physical, behavioural, social and developmental condition of children aged four. Such checks are performed by nurses through local primary health organisations (PHOs) funded by the district health boards (DHBs). Screening for behavioural and psychological needs consists primarily of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the Parental Evaluation of Developmental Status tool. The B4 School Check which reaches some 80% of all New Zealand pre-schoolers provides a valuable benchmark for families and an early warning for potential learning difficulties or special educational needs. The psychological and emotional component of this tool could be expanded to ensure low-threshold psychological support can be delivered early on.

Primary and secondary schools are equipped to cater for a majority of difficulties children encounter around learning, communication and behaviour. Schools can access several types of funding for pupils with moderate or more severe learning or behavioural needs. Pupils with moderate learning or behavioural needs can gain support from local Resource Teachers: Learning and Behaviour (RTLB) services, funded by the Ministry of Education. In total, in the school year 2017/2018 almost 1 000 RTLB teachers were available serving approximately 15 350 students, meaning that every resource teacher on average had to support some 16 students, but with considerable regional variation.

Funding for children with more significant educational needs (1‑2% of all school pupils) is provided by the Ministry of Education via the Ongoing Resourcing Scheme (ORS) (Ministry of Education, 2017[9]). The ORS provides special financial support for pupils with significant learning difficulties to remain among peers within a mainstream education setting. ORS support can be used to engage special teaching staff to deliver one-to-one support in classrooms alongside specialist support for counselling, speech and language therapies and occupational therapy. There is also a choice for some children following an ORS assessment to attend one of currently 30 special schools although the government is aiming to close these schools (Ministry of Education, 2018[15]).

Limited information is available about the extent to which these additional funds and forms of support also reach youth with mental health conditions. Youths with more internalising problems (e.g. anxiety and depressed mood) as opposed to more visible problems (such as disruptive or aggressive behaviour), are especially likely to miss out on additional learning support. Monitoring the share of pupils accessing these schemes by cause and type of problem could provide valuable insight.

Mental health awareness and abilities to intervene early

Improving mental health literacy within school communities and children’s homes is a critical lever for positive impacts further down the line. Schools in many OECD countries may fail to recognise or act upon early warning signs of mental distress (OECD, 2015[1]). Specialist staff may be unavailable while ordinary teachers often face time constraints in their day-to-day work or lack the necessary knowledge to deal with such issues. Family members and others may likewise be ill prepared to identify and act upon early signs of mental health issues among youth. Stigma towards mental health conditions often further exacerbates the problems and limits the solutions among schools, homes and communities that fail to address it concertedly.

Awareness-raising and training initiatives need broader implementation

New Zealand has a variety of awareness-raising and training initiatives to improve knowledge around mental health issues affecting children and youth. Some focus more on teachers and school leaders while others target parents, carers and whanau.

Schools in New Zealand may address a range of common issues around mental health via the guidance protocols provided by the Ministry of Education and bodies like ERO, NZCER and others. These tend to be evidence-based and draw on practices developed in other countries.

Available teacher training packages and guidance materials that can contribute to improving the situation of youth with mental health conditions include the following:

Understanding Behaviour, Responding Safely is a training workshop organised directly by the Ministry of Education to teach school staff specific behavioural management techniques. The training focuses on prevention and de-escalation techniques with a proven effect. It is delivered to schools’ entire staff alongside ongoing support from local Ministry of Education offices.

Wellbeing@School is a website supported by the Ministry of Education that allows teachers and school principals to review their own performance around pupils’ wellbeing and inclusion. The site hosts a periodic self-assessment tool for individuals and school communities, designed by NZCER. Some 1 200 schools are currently registered to access the site’s materials.

Pause, Breathe, Smile is a training programme organised by the Mental Health Foundation for teachers to deliver mindfulness meditation techniques to children in school. The programme’s courses for teachers have currently reached around 200 schools throughout New Zealand . Participation in the programme leads to statistically significant and potentially lasting improvements in children’s calmness, attention-keeping, self-awareness, conflict resolution and relationship skills alongside improvements around teachers’ wellbeing and job satisfaction (Bernay et al., 2016[17]; Devcich et al., 2017[18]).

Help for the Tough Times provides advice and guidance for school teachers and principals addressing pupils’ mental wellbeing. It is part of the Health Promotion Agency’s broader Lowdown youth mental health campaign. Lowdown seeks to help young people talk about and overcome common life issues such as study stress, sexual identity, isolation, bullying and romantic and peer relationships. The campaign combines social media, digital advertising and street posters with an online forum, self-help materials and useful links.

Beyond supports targeted to classrooms, there are several materials designed in parallel to address children’s wellbeing at home and in their local communities. Supports targeted towards parents, guardians and whānau include the following:

MH101 is a one-day training programme funded by the Ministry of Health to help educate the general population to understand and respond to mental distress or mental health conditions in others. In 2012, modules of MH101 were specifically adapted for meeting young people’s needs under the government’s Youth Mental Health Project. MH101 is routinely rolled out to staff working in New Zealand’s Attendance Service, the Work and Income Youth Service, school-based social services and related occupations.

Guidelines for supporting young people with stress, anxiety and depression is a publication developed in 2015 to help equip families, friends and whānau with the knowledge and skills to support a young person going through mild or moderate mental distress (Ministry of Social Development, 2015[19]).

The Mental Health Foundation provides a parallel web-, phone- or text-based support and counselling line called Common Ground to help guide parents, whānau and friends in supporting a young person experiencing mental distress.

Despite such a strong and diverse set of instruments in place, there remains some concern that they are failing to reach a wide-enough audience. An NZCER survey from 2016 revealed unmet needs for training and support around mental health, in particular, with only 20% of teachers indicating they could access training around detecting the signs of mental distress and only 34% of principals reporting that their schools were offering such training. Furthermore, 38% of school principals cited an unmet need for external expertise around mental health and 29% of teachers thought the support within their schools was inadequate (Boyd, Bonne and Berg, 2017[12]).

The inadequate implementation of available instruments in schools may be explained by a lack of regulation. New Zealand’s devolved education system offers considerable liberty and flexibility around the training and ongoing development incumbent teachers may receive. This implies that while some school administrators may focus their resources on mental health related training, others will invest in other areas. Information is lacking on how many schools are implementing programmes to improve mental health awareness among teachers. Additional measures are necessary to ensure improved mental health literacy of educational professionals nation-wide. For example, including considerable mental health training in the national teacher curriculum would be a way to realise this.

School-based health services need to be extended and monitored

Schools may provide school-based health services. Such primary care services could involve an on-site primary care nurse, a visiting public health nurse, or a DHB nurse. Earlier models included an affiliated social worker, and this model is continued in some schools. Government-funded school‑based health services are available in public secondary schools in the bottom three socio-economic deciles7 (in the current financial year this is expanded to include decile 4 schools) as well as Teen Parent Units and Special Schools.8 Within school-based health services, there are some concerns about nurse capacity given a ratio of around 750 students per nurse.

School-based counsellors can be part of the broader school-based health services. They may deliver direct talking therapies alongside specialised screening tools. Those tools used under certain circumstances include the Patient Health Questionnaire for picking up on general depression; the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions for suicide prevention; and the CRAFFT Screening Tool and the Substances and Choices Scale for potentially harmful behaviours related to substance use (Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand, 2015[20]). However, according to the New Zealand Association of Counsellors (NZAC), the current counsellors-to-students ratio in secondary schools is inadequate with one counsellor being responsible for up to 1 000 students while a more meaningful ratio would be closer to 1:400. Furthermore, school counsellors mostly work in secondary schools, while better continuity of care would be ensured when they also became employed in primary and intermediate schools.

In 2012, the government launched the Youth Mental Health Project, primarily targeting the age group 12‑19 and including a range of school-based programmes aimed at closing existing service gaps. This project followed the landmark report “Improving the Transition” which focused on ways to improve mental health outcomes for young people transitioning into adulthood (Gluckman, 2011[21]).

The Youth Mental Health Project launched and financed 26 individual initiatives across the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Social Development and Te Puni Kōkiri (Ministry of Māori Development).9 Most initiatives are still ongoing.

One of the most lasting of the 26 initiatives delivered has been the roll-out of the HEADS Assessment addressing young people’s experiences and feelings around their home environment (H), education and employment, eating and exercise (E), activities and peers (A), drugs and alcohol, depression and suicide (D), and sexual health, safety and personal strengths (S). HEADS assessment is a confidential, loosely structured interview tapping into each of the topic areas; it provides a valuable screening tool for mental distress and potential vulnerabilities around psychological and emotional health. These interviews are also seen to play a useful role in opening young people up to talking about their feelings and address concerns that may come up in the future. However, nation-wide implementation is challenging. An evaluation of school-based health services in 2012 with a random sample of 90 secondary schools across New Zealand found that only one in five schools routinely perform HEADS assessments (Denny S. et al., 2014[22]). With the recent extension to decile 3 and the ongoing extension to decile 4 schools, such assessments or wellness checks will soon be performed in about 40% of all (secondary) schools.

Several of the other 26 initiatives, aimed at creating more supportive schools for pupils’ mental wellbeing, have also had a first impact. First, this includes the national rollout of the PB4L School-Wide initiative, mentioned earlier. Second, a cognitive behavioural therapy programme, the My FRIENDS Youth Resilience Programme, was piloted over a two-year period among approximately 14 000 Year-9 students in 26 schools. Third, the Youth Workers in Low-Decile Secondary School (YWiSS) initiative was piloted in 20 schools with a specific focus on youth with mental health issues. Both pilots showed improved self‑management among students (e.g. managing own feelings and thinking about the feelings of others) and the YWiSS pilot showed better school results (Superu, 2016[23]; Macdonald et al., 2015[24]).

Another potentially relevant programme is the Social Workers in Schools (SWiS) service, introduced in 1999 but expanded significantly in 2012‑13, with additional funding provided through the Youth Mental Health Project. Initially only available in some primary and intermediate schools, SWiS is now available in all around 700 decile 1‑3 schools (up from around 300 schools previously); schools with a large share of Māori and Pacific students. The aim of SWiS is to foster school engagement and protect vulnerable children through the provision of group-based programmes as well as individual casework with children and their families and whanau. A 2018 evaluation of the programme found SWiS is acceptable to service users and successfully engages families and whanau. It also identified positive effects for service users in terms of a reduction in school stand-downs and suspensions and police apprehensions but no overall statistically significant effects, which is due to the small size and low intensity of the programme, with a caseload of 400‑700 students per social worker (Wilson et al., 2018[25]).10

Comprehensive school-based health and social services affect mental health outcomes, but are not yet common practice in New Zealand. The study mentioned above showed that of the 90 surveyed schools, 12% provided only the minimum requirement of first-aid health services, 56% worked with visiting health professionals and only the remaining 32% provided more comprehensive health services in the form of a health professional (mostly a school nurse) on site (20%) or a collaborative health team on site (12%). Furthermore, in schools with a visiting health professional, 0.8 hour of support per week per 100 students was reported on average, while schools with an on-site health professional or health team reported on average, respectively, 4.2 and 4.8 hours of support per week per 100 students. The study also evaluated how school-based health services affect young people’s mental health. Pupils in schools with comprehensive health services (i.e. health professionals on site) were significantly less prone to depression; faced a lower risk of suicide; paid less visits to doctors; and (to some extent) reported safer sexual activity. Overall, the results suggest that pupils benefit from high quality school health services consisting of on-site health professionals who are trained in youth health and have sufficient time to work with their pupils (Denny S. et al., 2014[22]).

The implementation of comprehensive school-based mental health teams in Canterbury after the major earthquake has also been positively received although a formal evaluation on improved mental health outcomes has not yet been performed. The school‑based mental health teams deliver interventions such as identifying students with mental health issues and supporting referrals to wider services; assisting schools to understand student behaviour by providing or facilitating workshops; and consulting with parents, teachers and pastoral care teams. These teams have been implemented in 102 primary and secondary schools in the Canterbury region (Superu, 2016[23]).11

Schools across New Zealand would benefit from such school-based mental health teams. It would be advisable to explore how a system comparable to the Canterbury one could be translated to a national policy for all schools or at least low-decile schools with a more vulnerable student population. The government’s plans to change the decile-based school funding system to a new approach based on students’ “risk of not achieving” may provide a good opportunity to include mental health as a new indicator, thereby allowing more funding to implement adequate mental health services for schools with a larger share of pupils with mental health conditions.

The high degree of autonomy for schools in New Zealand provides an opportunity to deliver those services most needed for a school’s student population, but monitoring is needed to ensure important issues such as mental health are addressed in all schools. A national or regional monitoring system of school-based (mental) health services is lacking and knowledge is thus limited on the number of schools contracting school nurses, social workers, counsellors and youth mental health professionals and on hours of support that is available per school and per student. Minimum health service standards could be set to ensure all schools are apt to the mental health challenge they are facing.

Adequate low-threshold mental health support for children and young people

Countries commonly struggle to ensure that adequate support and treatment for mental health problems reach young people in a timely way (OECD, 2015[1]). Many such problems may go unreported or undetected over extended periods. Even young people with diagnosed mental health problems can encounter low treatment rates, for example due to long waiting times or high thresholds for entering health services. Misinformation and stigma, in turn, may contribute to making things worse.

A stepped-care approach to mental health for youth can help in developing timely, low‑threshold and adequate services. These types of models recommend that the first mild‑to‑moderate signs of mental ill health are intervened upon by easily accessible support structures and primary care services. More specialised services are added when the severity of need and impact increases. This health services model is increasingly used internationally and has shown to be cost-effective (Ho et al., 2016[26]).

Mental health services for youth need alignment with a stepped-care model

The Youth Primary Mental Health Service (YPMHS), one of the 26 initiatives of the Youth Mental Health Project, has been directed at up-scaling primary care services for young people aged 12‑19 with mild-to-moderate mental health conditions. It builds upon the existing Primary Mental Health Services (PMHS) that are embedded in primary care, but rarely delivered to youth. YPMHS was started in 2012 and the implementation and results have been evaluated up until 2015 (Malatest International, 2016[27]).

Under YPMHS, NZD 1.3 million were allocated to the District Health Boards (DHBs) over four years (2012/13 to 2015/16) in order to: (1) expand the age range of primary mental health services; (2) adapt existing services for youth; (3) expand existing NGO or community-based initiatives; and (4) develop new initiatives to meet local needs. YPMHS have been able to reach 3 000 to 4 200 youth each quarter, including more females than males (around 60‑65% of the recipients were female) and a high share of Māori youth (almost one-third of the clients, compared to 21% of Māori youth in the total youth population). The most frequently used interventions were individual counselling (brief intervention) and packages of care with three to six counselling sessions.

YPMHS funding has been used to develop youth-friendly primary mental health services, but it is unclear whether services are easily accessible for youth and if young people receive the right services. General practices are the main access point for youth primary mental health care. However, the New Zealand Health Survey 2014/15 showed that not all young people go to a general practice: unmet need reaches a level of 22%. To increase access, YPMHS funding may need a stronger focus on entry points outside general practice, such as NGO or community-based initiatives who deliver multiple youth-specific services. In terms of actual services, it is essential that providers under YPMHS are equipped to provide first support to youth with mental health issues and can refer them easily to additional services if needed. The YPMHS evaluation showed that of the 317 surveyed providers (primarily GPs and practice nurses in primary care), as many as 20% were only a little confident in identifying and helping a young person with mental health conditions (Malatest International, 2016[27]). Some 30‑50% were only a little or not at all confident in providing certain common interventions such as talking therapies or motivational interviewing. While four in five providers indicated they could refer clients to other services, one in two mentioned a lack of suitable services as a major barrier to providing good care for youth with mental health problems. Accessing specific services showed to be particularly difficult for Māori and Pacific youth, according to more than 70% of the providers. Among the main recommendations from the YPMHS evaluation are to invest in: (1) reducing access barriers for help-seeking youth; (2) increasing the capacity of youth‑specific services; and (3) developing the youth workforce.

A well-functioning stepped-care model would include easy referral, when needed, from primary to specialised mental health care. This is not always the case. Almost two in three YPMHS providers indicated that secondary mental health services were not at all or somewhat difficult to access. Around 60% experienced waiting times for such referrals to specialists as a major or substantial barrier to providing care to young people with mental health conditions. Young people aged 0‑19 face longer waiting times for mental health and addiction services than adults, with fewer than 70% receiving a first appointment within three weeks of their referral, below the government’s target of 80% (Office of the Health and Disability Commissioner, 2018[28]). YPMHS evaluation thus recommended increasing investments in the development of efficient and cohesive youth mental health services including the co-location of primary and specialist youth services.

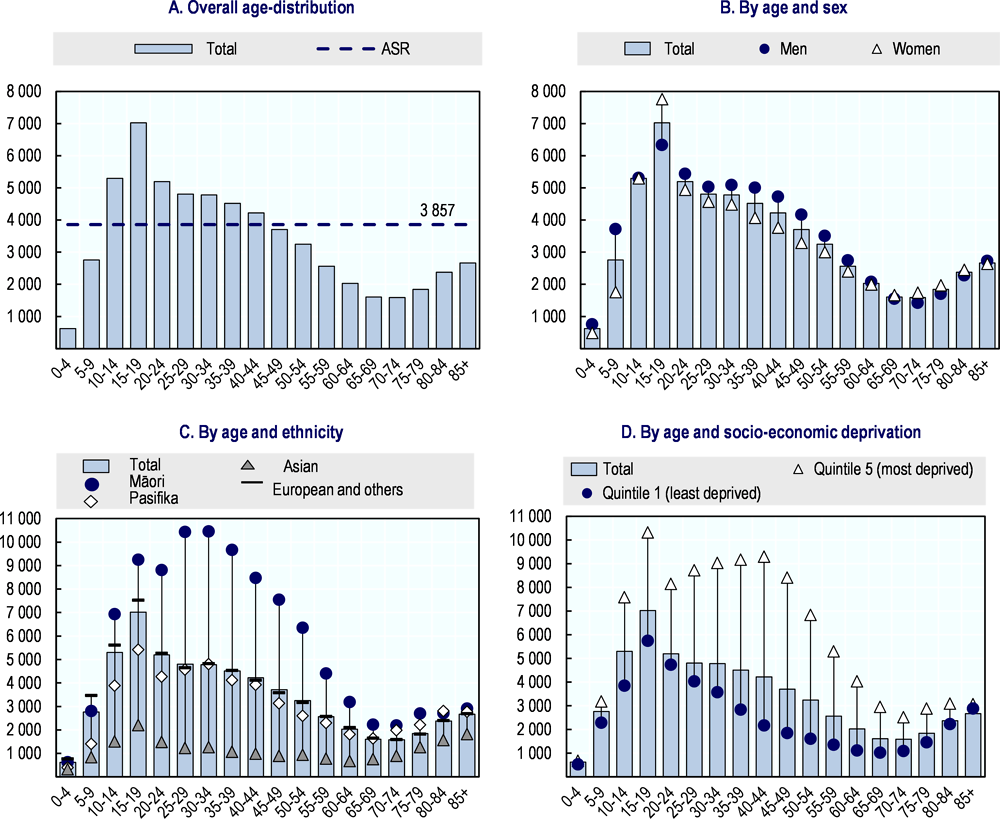

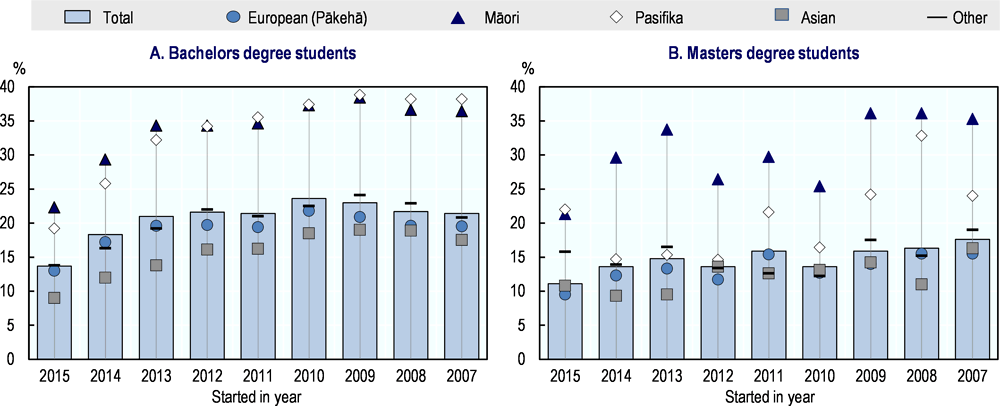

Although referral to youth specialised mental health services is not without issues, these specialised services more frequently see young people than adults. According to data from the Programme for the Integration of Mental Health Data (PRIMHD), 7% of young people aged 15‑19 accessed mental health and addictions services in New Zealand during the 12 months to July 2017. This was a higher rate than for any other age-bracket, with 10‑14 year-olds and 20‑24 year-olds following with over 5% (Figure 3.1, Panel A). Support was accessed by females and males at similar rates in every age group, except 5‑9 year-olds where boys far outnumbered girls (Panel B). The Māori population accessed support at much higher rates than any other ethnic group (Panel C). Socio-economic deprivation also plays an important role in access to mental health and addiction services. Based on a composite index of socio-economic deprivation, those living in the worst-off areas accessed services at significantly higher rates than those in other locations (Panel D).

Today’s rates of access to mental health and addiction services among children and youth are a big improvement on the situation from a decade ago. The Mental Health Commission (1998[29]) established national targets for access to public mental health and addiction services under its “Blueprint for mental health services in New Zealand ”, which continues to be referenced today. Alongside an overall target of 3% of the population each year, on aggregate, the Blueprint introduced age-disaggregated targets for child and adolescent services to reach 3% of the population aged 0‑19 in every six-month period, including: 1.0% among children aged 0‑9; 3.9% among adolescents aged 10‑14; 5.5% among young people aged 15‑19; and 6.0% among the Māori community aged 0‑19. Official reports for the year to July 2017 confirm that the current system well exceeds these targets and that the growth in access from children and adolescents exceeds that of the adult population (Office of the Health and Disability Commissioner, 2018[28]).

The rise in access rates to specialised mental health care for young people partly follows the continual increase in funding for child and adolescent mental health and addiction services. However, it may also partly reflect difficulties for some groups of the population, especially young Māori and other disadvantaged groups, in accessing primary care. Primary and specialised care are organised very differently in New Zealand (see Chapter 2); while the latter is free of charge, use of primary care comes with considerable co-payment for the users although children under age 13 (and soon age 14) are free. This could be an incentive to seek care from the specialised sector when in fact the primary care sector could have been the most suitable provider of care, or at least a good first point of call. However, the extent to which such financing constraints may stimulate an under-use of primary care and an over-use of specialised care is unknown.

Figure 3.1. Young people have the highest access to mental health and addiction services of any age group in New Zealand

Note: “Clients seen” include users of mental health and addiction services, including remote services (e.g. telephone contact with a clinician). “ASR” indicates the age-standardised rate for the population as a whole. Socio-economic deprivation is for small geographic areas, using variables from the 2006 Census of Populations and Dwellings (full methodology is available from www.health.govt.nz; search for “NZDep2006 Index of Deprivation”). The sum of clients seen across all deprivation quintiles is greater than the total number of clients, as some clients were recorded in more than one quintile during this period.

Source: Programme for the Integration of Mental Health Data (PRIMHD).

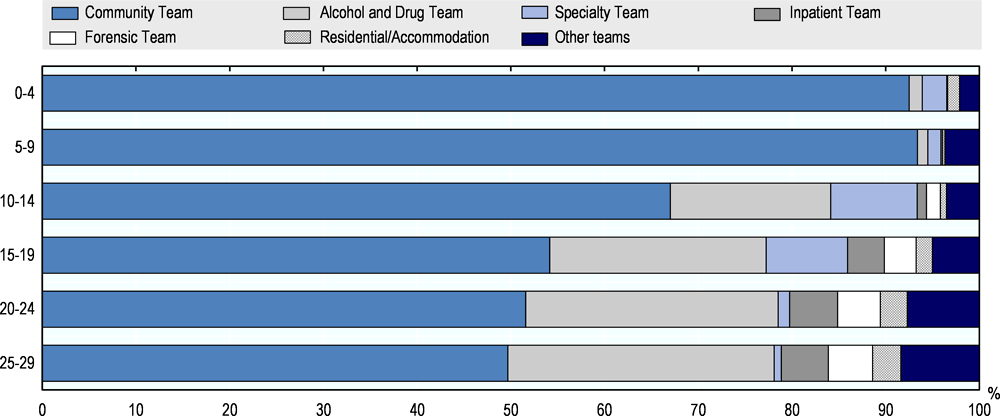

Within the specialised sector, community teams (consisting of various mental health professionals) accounted for virtually all mental health care delivered to children during the 12 months to July 2015, including around 93% of the contacts made with 0‑4 and 5‑9 year-olds (Figure 3.2). Other specialised teams are used more and more frequently among older age groups. Alcohol and drug teams, for example, accounted for 17% of contacts made with 10‑14-year-olds, rising to 28% among 25‑29 year olds.

Figure 3.2. Community teams in New Zealand are the main provider of specialised mental health services for children

Note: Data represent total contacts per team and may exceed the total number of individual clients within the system due to some double counting (i.e. where a client has had contact with more than one type of team). A small number of teams have been miscoded to inpatient team type, slightly overestimating the inpatient team share. The Ministry of Health is working with the relevant teams to correct this. “Others” include needs assessment and service coordination teams, eating disorder teams, co-existing problems teams, intellectual disability dual-diagnosis teams, specialist psychotherapy teams and early intervention teams.

Source: Programme for the Integration of Mental Health Data (PRIMHD).

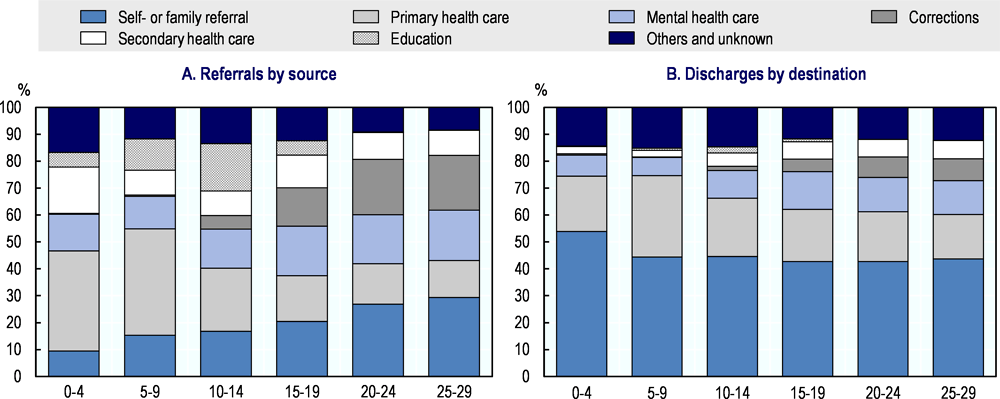

In line with a stepped model of care, young people would ideally not only access primary (mental) health services before accessing specialised care but also be referred back to primary care after specialised treatment has finished. This enables a low-threshold and low‑cost follow-up of young people ensuring a quick response to recurring problems and good monitoring of treatment compliance. Data on discharge pathways by specialised youth mental health services seem to indicate that this is not common practice in New Zealand, however. More than 50% of child clients, aged 0‑9, were discharged without any further referral. This was likewise the case for more than 40% of adolescents and young adults (Figure 3.3), likely being another proof of a certain disconnection in New Zealand between privately run primary care practices and publicly-funded secondary care units.

Figure 3.3. Most children and adolescents in New Zealand are referred to mental health and addiction services by their GPs or their family and most are discharged back home

Note: A client can have more than one referral open at one time and might, therefore, be counted against more than one referral source. New referrals are defined as those made within the year to 30 June 2015. The groupings shown are aggregates of multiple categories within the original data:

‒ Self- or family referral includes referrals made by clients themselves, by their relatives or by Māori or Pasifika community groups.

‒ Primary health care referrals and discharges include those made from or to a general practitioner, private practitioner, paediatrics service or a needs assessment and co-ordination service.

‒ Mental health care referrals and discharges include those made from or to an adult community mental health service; a child, adolescent, family or whānau mental health service; a psychiatric inpatient or outpatient service; or a mental health residential service.

‒ Corrections referrals and discharges include those made by or into the justice system, the police or alcohol and drug rehabilitation services.

‒ Secondary health care includes referrals and discharges made from or to (non-psychiatric) hospitals, accident and emergency services, public health services and community support services.

‒ Education referrals and discharges include those made from or to education providers, vocational services and mental health community skills enhancement programmes.

‒ Others and unknown includes referrals and discharges made from or into the social welfare system, services not already listed plus unknown sources or destinations.

Source: Programme for the Integration of Mental Health Data (PRIMHD).

Community services provide a good opportunity for better-integrated support

There are various social and community services available in New Zealand for young people experiencing mental health problems. Perhaps the foremost institutions offering support and guidance in this space are the Youth One Stop Shops (YOSS).

YOSS is a community-based facility offering access to health (including mental health) and other services using a holistic model of care. YOSS provide targeted services to, and are responsive to the needs of, young people aged 10 to 25 years. The aim is to provide coordinated health, education, employment and social services, at little or no cost to the client. The services are strengths-based and provided in an atmosphere of trust, safety and confidentiality. The first YOSS was set-up in 1994; currently 11 such services are funded as part of the YOSS network across New Zealand and the number is still increasing.12 The Ministry of Health is a primary funder of these services. Additional funding is provided through a multitude of other sources such as private donors, city councils and the Ministries of Social and Youth Development.

In 2009, an evaluation of YOSS took place on request of the Ministry of Health. It consisted of a survey among 12 YOSS managers (there were 14 YOSS in 2009), 252 clients and 101 stakeholders (e.g., the Ministry, DHBs, PHOs, and other service providers) and of meetings and focus groups with approximately 50 managers and staff, 60 clients and 60 stakeholders. The evaluation focused, among other topics, on the types of services provided, the composition of the client group, reach-out to Māori communities, the effectiveness in improving access to health care, and links between YOSS and other services (Communio, 2009[30]). General health/primary care, sexual and reproductive health and family planning were the most commonly provided services (provided by 11 out of the 12 YOSS), followed by mental health services (provided by 10 YOSS). Mental health services included assessment, counselling, treatment, advocacy and support for young people with a range of mental health conditions. Eight of the 12 YOSS specifically employed a counsellor for 0.5 to 2.0 FTEs (doctors, nurses and youth workers were most commonly employed). However, it was generally reported that demand for counselling and other mental health services was clearly exceeding capacity. The eligible population per YOSS ranged from 7 000 to 54 000, and in total all YOSSs together provided services to around 28 000 to 34 000 young people. Youth aged 15‑19 years most frequently visited a YOSS (52.5%), followed by the 20‑24 year-olds (30%). The majority of young people (64%) were New Zealand European followed by Māori (30%).

Effectiveness in terms of improved accessibility was assessed by the opinions of managers, clients and stakeholders. Managers mentioned various ways of addressing access barriers for youth, including youth-friendly opening hours taking into account study and work commitments; service facilities located centrally and close to public transport or areas of interest to youth; mobile services to engage with youth outside the main facility; and investment in developing cultural competency skills in staff. All three survey groups thought that YOSS were very effective in helping young people receive the health service they need and quite effective in promoting access to other (non-health) services. However, as mentioned above, lacking capacity for prompt appointments with a YOSS representative or counsellor was a major barrier to better outcomes.

Concrete evidence on improvements in health and wellbeing was unavailable due to a lack of concerted data collection; the 2009 evaluation had to rely on questions posed to the three survey groups. All managers thought that YOSS were effective in helping to improve young people’s health and wellbeing, and 94% of the clients and 89% of the stakeholders agreed to this. Managers stressed the importance of developing a national minimum dataset of clinical and demographic information. A renewed evaluation would be timely now, almost ten years later, given that no national data on clinical and social outcomes has been made available since. Systematic outcome measurement including information on (mental) health, education and social outcomes (such as e.g. employment success) would make a stronger case for expanding YOSS and investing in a better integration of its services with other youth services, and understanding and addressing inequities.

YOSS services were especially valued by the survey respondents for their unique focus on youth appropriateness and the creation of a collaborative environment by linking up with other service providers, which enabled primary and secondary health and social services to be integrated successfully. Of the surveyed stakeholders, almost half were linked with a YOSS by referring clients to it and 20% received referrals from a YOSS. Only few stakeholders (9%), however, provided services through a YOSS suggesting that a true integration of services is still an exemption. This especially concerns youth primary mental health services, which – back in 2009 – were seen as an important service gap by the survey respondents. A strong integration of YOSS with the parallel structure of Youth Primary Mental Health Services could contribute to further closing this gap.

Youthline and SPARX are two other prominent initiatives nationally available to youth with mental health conditions. Youthline is a charity organisation, set up in 1970, forming a collaboration of youth development organisations. Nine Youthline centres are established across New Zealand. Their main goal is to ensure that young people know where to get help and how to access support when needed. Youthline contributes to the development of leadership and personal skills in young people, and offers remote‑access support (self-help programmes and a helpline operating through telephone and email) to young people experiencing mental distress. It also offers face-to-face, non‑acute mental health-related support and can refer clients to clinical and social services. Youthline’s mental health advice covers general wellbeing themes (self-esteem and confidence, grief and loss, life transitions or change) alongside more acute mental health‑related problems like anxiety and depression, bullying, abuse and violence, self‑harm and suicide. Evaluations for single Youthline centres suggest that they are well known and received but under-resourced (Research Services, 2018[31]).

SPARX is a web-based therapeutic tool to help young people experiencing mild‑to‑moderate depression and facing high levels of anxiety or stress. A randomised‑controlled trial has shown that SPARX results in a clinically significant reduction of depression, anxiety and hopelessness and an improvement in quality of life (Merry et al., 2012[32]). As one of the initiatives under the government’s Youth Mental Health Project, funding was directed at a national rollout of SPARX. An evaluation in 2016 showed that in the financial year 2014‑15, 2 577 young people had registered on SPARX (in comparison, the total number of youth clients in Youth Primary Mental Health Services was 13 500). Māori, Pasifika and Asian youth were highly under-represented among SPARX users. Of all users, 82% completed at least one of the seven modules, and the share of completers was highest among those with more severe depression symptoms (Malatest International, 2016[33]). However, only 40% completed the first of the seven modules and only 24% and 10% of those went on to completing module four and seven, respectively. Reasons for not completing all SPARX modules were technical difficulties, which have meanwhile been removed (28%), no more help being needed (25%), the idea that SPARX was not helping (19%), and not liking SPARX (16%). The low adherence rates are comparable to other online mental health tools. Of the young people surveyed about their use of SPARX, 43% indicated their use for about a month, while 35% used it for a week or less. SPARX was most commonly used two or three times a week (by 42% of the respondents), followed by less than once or twice a month (32%). The Patient Health Questionnaire which is used to measure the person’s mental health status is completed before using SPARX and after completion of modules four and seven (i.e. data on these three measurement points are only available for the small group who completed all these modules). The results showed an overall trend of improvement in depressive symptoms, especially for those who had more severe symptoms at the beginning. The majority of users also reported improvements in their wellbeing and the ability to manage their own wellbeing. For a slight majority, SPARX also was as an initiator to seek additional help.

To conclude, several strong community initiatives to support youth with mental health conditions are available in New Zealand. YOSS especially has great potential to further integrate (mental) health, social, educational and employment services for young people. Together with Youthline, it functions as a first point of entry from where young people can be guided quickly to additional appropriate services. Full coverage across the country would be essential and the YOSS workforce would need to be increased to be able to balance the high demand for their services remaining unmet.

Attention to and support for early school leavers

Children and young people with moderate-to-severe mental health problems are more likely to leave school early (OECD, 2015[1]). Young people who disengage from school limit their potential for gaining adequate qualifications and weaken their job opportunities. Some may disengage from the labour market and come to rely on social assistance, further weakening their mental state and increasing the burden placed on public services.

The regular pathway through education in New Zealand

Primary and secondary education in New Zealand encompass pupils aged between 5 and 19 years, with attendance being compulsory for those aged 6 to 16 years (Ministry of Education, 2017[9]).13 School years 1‑8 make up primary level education; years 9‑10 lower‑secondary; and years 11‑13 upper-secondary level (with a possible extension into years 14 and 15 for repeaters).14

In 2017, some 2 500 schools in New Zealand delivered primary and secondary education to a pupil body of around 800 300 children and adolescents. State primary and secondary schools are free and accounted for 84.9% of school pupils in 2017. State schools teach the national curriculum and cater to all ethnic groups. State integrated schools accounted for an additional 11.2% of pupils in 2017. They deliver the national curriculum in the same way regular state schools do but apply an alternative pedagogic approach to their teaching (for example, based on a particular religious or philosophical lens) and may, in some instances, charge modest fees. The remaining 3.8% of school pupils in 2017 attended private schools and an additional 6 008 school-aged children in New Zealand were home‑schooled in 2017 (Ministry of Education, 2018[15]).

New Zealand has universal enrolment in compulsory education. Enrolment in primary education has been virtually universal since at least the 1970s and enrolment in lower‑secondary education has risen from around 90% in the mid-1970s to 98% today. Educational attainment at the upper-secondary level has increased steadily. Pupils in upper‑secondary school study for the National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) at one of three levels corresponding to the three years of upper-secondary education (years 11‑13). The share of adolescents leaving upper-secondary school with at least NCEA level 1 rose from 80.9% in 2009 to 89.4% by 2016. Meanwhile, those leaving school with at least NCEA level 2 rose from 67.5% to 80.3% and those finishing with NCEA level 3 rose from 41.9% to 53.9% (Duncanson et al., 2017[34]).

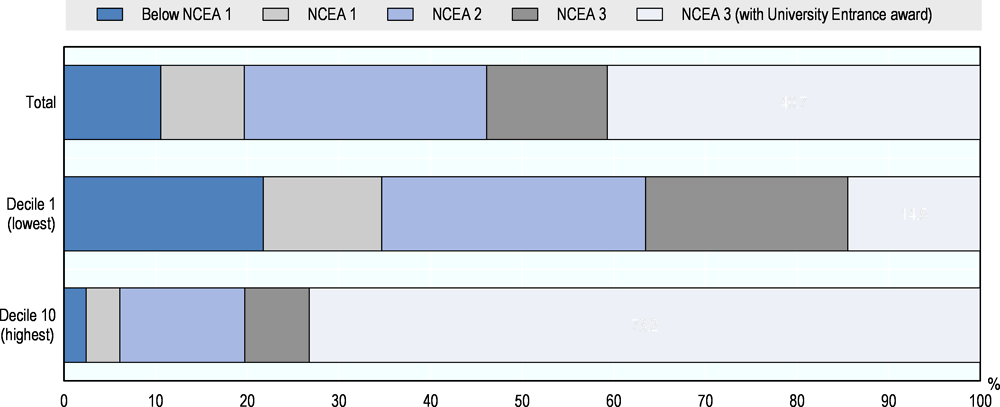

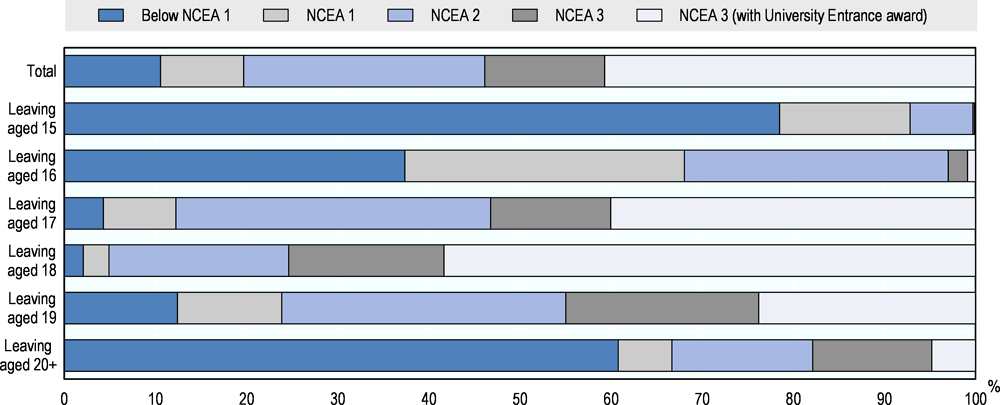

Although secondary attainment is increasing on aggregate, there remain some pockets of pupils with particularly weak outcomes. While 53.9% of school-leavers attained NCEA level 3 in 2016, on aggregate, the proportion was lower among young men (47.7%) and markedly lower among Māori and Pasifika youth (33.8% and 43.4%, respectively) (Ministry of Education, 2018[15]). Pupils from schools in poorer areas of the country also tend to achieve worse outcomes; the share of school-leavers with NCEA level 3 was only 36.5% among decile 1 schools but as high as 80.1% among decile 10 schools (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4. Secondary pupils in top-decile schools in New Zealand perform significantly better than their peers in low-decile schools

Note: NCEA=National Certificate of Educational Achievement. “School leavers” are secondary school pupils that have finished their schooling. School leavers are identified from the Ministry of Education’s ENROL system, while the highest qualification status for each leaver is obtained from the New Zealand Qualifications Authority (or directly from schools for pupils attaining non-NQF qualifications).

Source: Ministry of Education (2018) Education Works Database.

Early school leaving programmes need a focus on mental and social issues

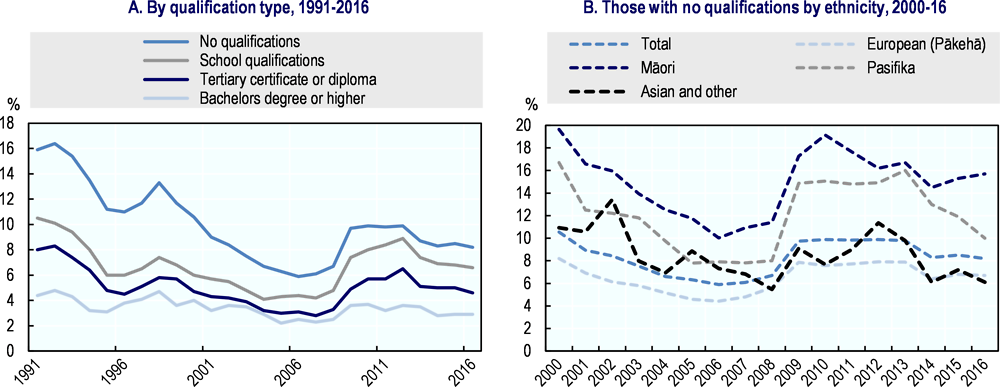

Early school leaving is detrimental for educational attainment and, ultimately, employment. As shown in A study from 2017 showed that NEET in New Zealand frequently use services for substance abuse and mental health conditions. Among 15‑24 year-old NEETs, the share who had ever used services or treatments for substance abuse and for other mental health conditions was approximately 20% and 40%, respectively. This figure is roughly three times the proportion of youth of the same age who are still in education, and two times the level of those who are in employment. Many NEETs also received some form of social benefits during 2015: approximately 30% and 50% of males in the ages of 15‑19 years and 20‑24 did so, respectively, compared to about 40% and 60% of females in the same age groups . These poor social and health outcomes for NEETs demonstrate the importance of investing in the prevention of early school leaving.

Figure 3.5, almost 80% of students leaving school at age 15 end with education below NCEA 1 level, while this share drops to 40% of students leaving school at age 16. Remaining in education up until age 18 is important for achieving higher educational attainment which, in turn, increases employment opportunities, especially so for those with a mental health problem (see Chapter 1). While some early school leavers may move on to work or other training, many end up in the group of youth not in education, employment or training (NEET). In New Zealand , the share of NEET among youth aged 15‑19 years and 20‑24 years was 5.4% and 13.1% in 2016, respectively, just below the OECD averages of 6% and 16.2% (OECD, 2018[35]).

A study from 2017 showed that NEET in New Zealand frequently use services for substance abuse and mental health conditions. Among 15‑24 year-old NEETs, the share who had ever used services or treatments for substance abuse and for other mental health conditions was approximately 20% and 40%, respectively. This figure is roughly three times the proportion of youth of the same age who are still in education, and two times the level of those who are in employment. Many NEETs also received some form of social benefits during 2015: approximately 30% and 50% of males in the ages of 15‑19 years and 20‑24 did so, respectively, compared to about 40% and 60% of females in the same age groups (Stats NZ, 2017[36]). These poor social and health outcomes for NEETs demonstrate the importance of investing in the prevention of early school leaving.

Figure 3.5. Educational attainment is highest for New Zealand students when they leave school at age 18

Note: NCEA=National Certificate of Educational Achievement. “School leavers” are secondary school pupils who have finished their schooling. School leavers are identified from the Ministry of Education’s ENROL system, while the highest qualification status for each leaver is obtained from the New Zealand Qualifications Authority (or directly from schools for pupils attaining non-NQF qualifications).

Source: Ministry of Education (2018) Education Works Database.

New Zealand has a number of monitoring and support systems in place to prevent early school leaving and/or re-direct early school-leavers (or those removed from their school) back to education. Some of the most prominent institutions currently in place are: the Attendance Service; a strictly regulated Early Leaving Exemption (to prevent school suspensions and expulsions); and a variety of alternative learning pathways for vulnerable pupils including Alternative Education Programmes, Activity Centres, Teen Parent Units, Correspondence Schools and Service Academies.

The Attendance Service provides support for pupils aged 5‑16 who cannot justify their absence from school. Pupils’ school attendance and enrolment are monitored closely by their school, with an obligation to notify the Ministry of Education for any absence of 20 days (though the service usually engages with the pupil sooner than this) and for punitive measures like suspensions, exclusions and expulsions. The Attendance Service is delivered by a number of NGOs through an annual budget of NZD 9.6 million funded by the Ministry of Education.

In 2016, the Attendance Service received 10 854 referrals for non-attendance and 7 514 referrals for non-enrolment. Of this latter group, 47% were successfully placed into education by the end of the year; 19% were legitimately withdrawn (either because they had turned 16, moved abroad, had died or been exempted for some other valid reason); while the remaining 34% continued to received support from the Attendance Service into the following year. Non-enrolment rates vary significantly by ethnic group: while they fluctuate around two per 1 000 of the corresponding student population among European and Asian New Zealanders (age-standardised rate across all age groups), they were at eight per 1 000 in 2012 for Pasifika students (up from 4 per 1 000 in 2007) and at over 14 per 1 000 for Māori students (up from 10 per 1 000 in 2007). The link between non‑enrolment and socio-economic disadvantage is strong: in 2012, students in decile 1 and 2 schools were 16 times more likely to be reported non-enrolled than students from decile 9&10 schools. Data on the link between mental health and non-enrolment are unavailable.

While school enrolment is compulsory for children and adolescents aged 6‑16, the Ministry of Education may grant an Early Leaving Exemption (ELX) to pupils aged 15 who intend to pursue a promising alternative pathway.15 An ELX may be granted only to pupils with documented problems around learning or conduct and on the condition that they would clearly benefit more from their proposed pathway than they could from school. Up to age 16, recipients of an ELX are closely monitored by the Ministry of Education – through regular contact with the employer or vocational training provider. Recipients of an ELX are eligible for Youth Service support under the Ministry of Social Development. There were 522 ELXs granted in 2017 (equivalent to 9.2 for every 1 000 15-year-olds in New Zealand). This is a big decrease from before 2007, when the Ministry of Education considerably strengthened its early leaving application and approval process to reduce the number of exemptions and the associated social and economic disadvantages those students were facing. Māori students have much higher rates of early leaving exemptions but the decline has affected all ethnic groups equally.

The Ministry of Education organises Alternative Education programmes (for pupils aged 13‑15) and enrolment in Activity Centres (for those aged 14‑17) as alternative routes through secondary education for pupils with particularly challenging behaviours or who disengage from mainstream education altogether. Alternative Education is a short‑term intervention aimed at re-engaging students in a meaningful learning programme shaped to their individual needs (through an Individual Learning Plan). It supports them to transition back to school, further education, training or employment. Schools can use Activity Centres to refer students who are likely to benefit from a specialist programme meeting their social and academic needs.

In 2016, 2 872 young New Zealanders attended Alternative Education and 482 gained support from an Activity Centre – most of them boys and the biggest number identified as Māori. A review of the way at-risk pupils are supported through Alternative Education and Activity Centres concluded support is variable and generally insufficient and coming too late to make a meaningful change to young people’s life choices and pathways. A main problem is adequate self-review and a lack of high-quality Individual Education Plans. A policy tool kit available for Activity Centres to support them in adequate service delivery is rarely used (Education Review Office, 2013[37]).

Adolescents challenged with completing their schooling alongside the demands of pregnancy and early parenthood can continue their education through government-funded Teen Parent Units. Governed by mainstream high schools, these units deliver lessons based on the national curriculum alongside on-site childcare facilities, guidance and mentoring, and access to support for health, mental health and social needs. In mid‑2017, Teen Parent Units supported 495 young mothers and seven young fathers throughout New Zealand. A disproportionate share of them were Māori, accounting for 61.8% of the total (Ministry of Education, 2018[15]). A recent evaluation concluded that specialised school-based services designed to meet the needs of young mothers reduce their disadvantage. Teen Parent Units are somewhat effective in raising educational enrolment and very effective in improving educational attainment (Vaithianathan et al., 2017[38]).

Children and adolescents unable to attend a local school may also engage in government‑funded distance learning via the Correspondence School (now known as Te Aho o Te Kura Pounamu). Originally founded in 1922 to cater for around 100 children living in New Zealand’s remotest parts, the Correspondence School today delivers classes to some 25 000 pupils across New Zealand (from early childhood education to secondary education) including some with specific developmental and mental health-related needs.

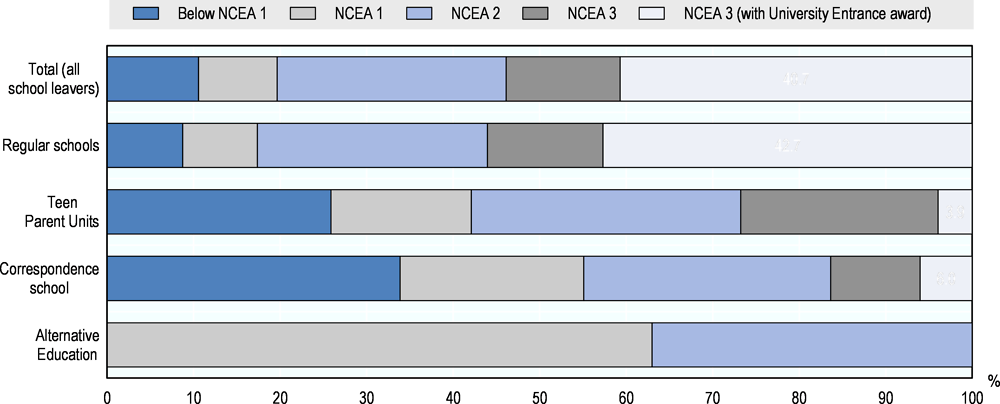

Learning outcomes for students in alternative forms of education stay way behind those of students in mainstream education. Of all students leaving a regular school in 2016, 56% left with NCEA 3 qualification, another 26.6% with NCEA 2 and less than 10% with below NCEA 1 (Figure 3.6). One in four students in Teen Parent Units and one in three in the Correspondence School leave school with a qualification below level 1, and only 26.7% and 16.4%, respectively, leave with NCEA 3 qualification. Outcomes for Alternative Education (for which only rough data are available) are even worse: only 37% achieve NCEA level 2 or above by age 18.

Service Academies are military-focused programmes run within secondary schools in collaboration with the New Zealand Defence Force. The Academies provide 580 places for students annually at 29 schools around New Zealand. The target group is year 12 and 13 students, particularly Māori and Pasifika males, at risk of disengaging from mainstream school who would benefit from a military-style programme. The programme offers courses in leadership and outdoor education, and is integrated with the wider school, supporting students to achieve at least NCEA level 2. An evaluation in 2011 found a high level of effectiveness of these Academies due to high quality teaching and strong leadership but also raised concerns about a lack of evidence on transitions back into regular schools and the degree to which access criteria ensure the right group of adolescents is being covered (Education Review Office, 2011[39]). The review called for stronger monitoring of the progress of students who return to school following their year in a service academy.

New Zealand has a large range of tools and options available to keep youth at risk of leaving school in education or to help those already out of school back into education. However, these programmes generally lack a focus on social and mental health issues, which may partly explain the much poorer outcomes from alternative forms of education. Social and mental health problems often play a key role among early school leavers, as shown by the situation and service use of the NEET population. Links between various ‘back to education’ programmes and social and mental health services are weak. Stronger interaction with available youth programmes, especially Youth One Stop Shops and Youthline centres, which could play a bridging function, but also with Youth Primary Mental Health Services will be critical to make the system more effective. It is also crucial that resources and approaches are targeted at and led-by Māori, otherwise the inequities in outcomes will continue.

Figure 3.6. Educational attainment for New Zealand pupils varies by the type of school they have attended

Note: NCEA=National Certificate of Educational Achievement. “School leavers” are secondary school pupils that have finished their schooling. School leavers are identified from the Ministry of Education’s ENROL system, while the highest qualification status for each leaver is obtained from the New Zealand Qualifications Authority (or directly from schools for pupils attaining non-NQF qualifications).

Source: Ministry of Education (2018) Education Works Database.

Transitions into further education and work