This chapter discusses barriers to competition in the legal professions: lawyers, notaries, solicitors and enforcement agents. In 2016, the legal professions accounted for EUR 823 million, corresponding to 0.4% of Portuguese GDP, and employed 35 631 people. These professions play a decisive role in the administration of justice. There are significant economic arguments for regulations specific to the legal professions which, when left unaddressed, could lead to inefficient market outcomes and a direct impact on social welfare. The legal professions enjoy exclusive rights to provide specified services and access to these professions is restricted. In return, legal professionals are required to comply with a range of regulations restricting advertising, licence quotas and geographic limitations for notaries, and fixed and maximum fees. The report proposes recommendations to reduce the negative impact of such restrictions while addressing the policy objective identified.

OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Portugal

Chapter 4. Legal professions in Portugal

Abstract

4.1. Introduction

In Portugal, legal services are mostly provided by four types of professionals ̶ lawyers, notaries, solicitors and enforcement agents. These professions provide a variety of services such as advice and representation in court, drafting of legal documents, authentication of private contracts, filing patents and copyrights, drafting of deeds, execution of wills and legal arbitration.

Lawyers and the solicitors can practise the same legal acts, except in the case of judicial mandate (legal representation). Notaries serve the public in non-contentious legal matters, usually concerning legal documentation, estates, authentication and other formalities. Enforcement agents (agentes de execução) ensure due diligence in the execution process, to execute individual citations and notifications and to promote evictions.1

The four legal professions are represented by three professional associations: the Bar Association (public association of lawyers),2 the Public Association of Notaries3 and the Public Association of Solicitors and Enforcement agents.4 These professions are analysed together as they constitute the main supporting pillars of the legal infrastructure in Portugal. The activities carried out by each of these professions are closely related to and occasionally depended on activities performed by the other legal professions. Several regulatory barriers to competition that have been identified are common to several types of professionals (legal and otherwise): these are addressed together in Chapter 3.

The recommendations discussed in this section were developed after a thorough analysis of the relevant legislation and of its impact in terms of harm to competition. Overall, the review identified 185 potential regulatory barriers in the 395 legal texts selected for assessment. In total, the report makes 182 specific recommendations to mitigate harm to competition within the legal professions. These are listed in Annex B of the report.

Table 4.1. Summary of analysed provisions applicable to the legal professions

|

|

Lawyers |

Notaries |

Solicitors and enforcement agents |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pieces of legislation |

103 |

168 |

124 |

395 |

|

Potential restrictions identified |

76 |

65 |

44 |

185 |

|

Recommendations made |

75 |

63 |

44 |

182 |

This chapter is divided into six subsections. After discussing the particular case of regulation of the legal services and providing an economic overview of such services, we describe each of the self-regulated regimes. The main regulatory barriers to competition in the legal professions are analysed next, identifying their harm to competition. Finally, we provide recommendations to mitigate or eliminate such harm. Barriers regarding the limits to advertising for legal professions are tackled in Section 4.3.4. Section 4.5 analyses the establishment of licensing quotas and geographical barriers. Section 4.6 deals with regulation on maximum and fixed fees.

4.2. The particular need for regulation of legal services

Legal services are tightly regulated through a form of social contract that one may think of as a "grand bargain" between legal professionals and society (Susskind and Susskind, 2015). The bargain is intended to solve the problem of asymmetric information between professionals and clients (see also Chapter 2) by providing a codifying licensing system to ensure quality and trust. However, this solution is weighed up against a certain loss of competition which may lead to above-normal rents. The "bargain" involves granting lawyers and notaries exclusivity to provide a set of prescribed services (see section 3.4.1.). Exclusivity is generally enforced through government recognition of the services provided (e.g. a requirement that certain documents are notarised) as well as legal prohibitions on providing services without a professional licence. In return for the exclusive right to provide legal services, professionals are required to comply with regulations seeking to address market failures and policy goals, such as:

Qualitative entry restrictions, which set out minimum requirements for professionals permitted to offer legal services, including education, professional experience, internships, examinations and personal characteristics, such as citizenship, language competence and the absence of criminal or civil convictions. These regulations reflect a desire to address information asymmetries as well as externalities. Qualitative entry restrictions are intended to address market failures because alternative measures, such as minimum quality standards and consumer information regulations, may be more difficult to implement and monitor. Instead, these restrictions, or prescriptive regulations, attempt to exclude low-quality service providers from accessing the market rather than setting out required characteristics of their output (outcome-based regulation). However, as highlighted by Canton et al (2014) and others, this may also reflect a degree of institutional capture, as the professions themselves, through their professional associations, contribute to the definition and setting of entry barriers to the profession to such an extent that the number of professionals remains limited. This is a major contributing factor to the high cost of such services. In Portugal all legal professionals are required to have a law degree and complete a professional internship before obtaining a professional licence (see Chapter 3).

Quantitative entry restrictions, aiming at ensuring service availability, particularly in remote areas, by guaranteeing a certain level of profitability through restrictions on competition. These restrictions apply to the notarial profession in several countries. However, there is debate about whether there are less restrictive alternatives to achieving the same goal, since this type of measure limits supply, increases prices and can create local monopolies. This is also the case in Portugal, where quotas and geographic restrictions are intended to guarantee the availability of notarial services all over the country (see section 4.3.5).

Fee restrictions, such as setting minimum fees, which were introduced in legal professions to prevent adverse selection on the basis of price and prevent moral hazard, while also reducing the burden of negotiation on the consumer. Economic theory suggests that price restrictions have an anticompetitive effect, which can be exacerbated by entry restrictions (see OECD, 2007). Specifically, fee restrictions can have a negative effect on market efficiency by reducing incentives to innovate and reduce costs. They may also facilitate market co-ordination and market sharing and not be proportional to the issues they purport to address. In Portugal, maximum and fixed fees are set for certain notarial activities (see Section 4.3.6).

Advertising restrictions, which are designed to prevent consumers from being persuaded into making decisions when they lack sufficient information, and prevent negative externalities to society (judicial system). The market for legal services is characterised by information asymmetry in the context of a "credence good" (see Chapter 2). Advertising can improve information available to consumers, reduce search costs and better enable prospective clients to choose among professionals, leading to more competition among established firms. The literature on advertising in the legal profession (Nelson, 1970, 1974; Grossman and Shapiro, 1984; Stahl 1994) suggests that advertising can have pro-competitive effects to facilitate entry. As OECD (2007) notes, there do not appear to be well-founded arguments against permitting advertising. Furthermore, studies have found that restrictions on advertising lead to higher prices (OECD, 2007). A similar analysis on the pro-competitive benefits of competition on consumer choice and market entry can be found in the Competition Assessment on Greece (OECD, 2014).

Restrictions on partnerships, ownership and management consist of prohibitions on partnerships between different legal disciplines (e.g. solicitors and barristers) or with non-lawyers (such as accountants), as well as restrictions on ownership and management of law firms by non-lawyers. In many cases, these restrictions extend to a prohibition against sharing offices with non-practitioners. In Portugal, a lawyer cannot share an office with an economist or auditor, nor enter into a formal partnership with non-lawyers. These restrictions, ostensibly in place to protect client-lawyer confidentiality, may prevent a more cost-efficient use of office space (sharing of overheads); or prevent the creation of “one-stop-shops” for business-client services (joining together legal advice, accounting and auditing, for instance), and ultimately prevent productivity gains (see section 3.5).

Requirements to provide legal aid are often imposed on lawyers and are aimed at providing low-income individuals with legal services to which they would not otherwise have access. Lawyers are compensated for their services, but often at a discounted rate compared to that which would be paid by other clients.

The enforcement and the development of the regulations for the legal professions are generally conducted through professional self-regulatory bodies that are recognised by the legislation. This approach reflects the view that members of a profession have information advantages over the lay person, and may be better positioned to enforce certain professional standards. However, self-regulation can create undue entry barriers while enabling the extraction of rents (OECD, 2007). In this regard, by increasing the level of difficulty to access the profession (by imposing an additional exam or a long internship), the supply of professionals will decrease which, in turn, will favour the arising of cartels and generate economic rents. The anticompetitive effects of self-regulation are also acknowledged by the US Federal Trade Commission: "Limits on state-action immunity are most essential when the state seeks to delegate its regulatory power to active market participants, for established ethical standards may blend with private anticompetitive motives in a way difficult even for market participants to discern. Dual allegiances are not always apparent to an actor. In consequence, active market participants cannot be allowed to regulate their own markets free from antitrust accountability."5

While the public policy objective consumer protection is clear, there is no guarantee that the thrust of much of the current regulation necessarily reduces the adverse effects of the imperfect information problem in the legal services market. As underscored by Canton et al. (2014), unless it is appropriately designed and implemented, regulation may in and by itself contribute to the creation of market restrictions and limit consumer choice.

More seriously, the barriers to competition imposed by regulation can also lead to reduced market performance as inefficient firms may remain in the market while efficient firms cannot grow, preventing an efficient allocation of resources in the market for legal services. There is ample empirical evidence that regulatory barriers may be used by incumbents to obtain higher margins, while a more competitive environment may be expected to drive prices down to competitive levels. Hence, certain population groups are excluded from access to legal services. This is one of the concerns raised about the legal services in several jurisdictions.

In 2013, the Legal Services Bureau (LSB) in the UK explored the reasons why people choose not to use lawyers, noting the importance of perception of cost and the lack of transparency of costs as key barriers. The Civil and Social Justice Panel Survey (CSJPS)6 found that 57% of participants who used a not-for-profit organisation rather than a lawyer did so because of the perceived or actual costs of a lawyer. As a consequence of perceptions around costs, the analysis found that individual consumers on lower incomes were less likely to take action or seek legal advice.

These obstacles are likely to reduce the overall size of the potential legal market, in particular where use of legal services is not mandatory. Studies carried out for England and Wales found that the cost of legal services is a contributing factor in the decision to reject legal support.7 Further research carried out jointly by the UK Law Society and the LSB in 2016 found that for those who had a legal problem over the 2012-2015 period and considered but did not use a solicitor, 28% made the assumption they would be too expensive. A further 11% did not think the solicitor would offer value for money.8 An ever-expanding legal aid programme is not necessarily the solution as it would weigh too heavily on tax payers. A smarter solution, such as online service provisions and advice for frequently asked questions, would lead to lower prices being charged in at least the routine legal cases.9

Recent findings by the World Justice Project General Population Poll on the Dispute Resolution Mechanism administered in 45 countries and jurisdictions in the fall of 2017 show that in Portugal the average time to solve a legal problem is around 24 months. This is significantly higher than in countries such as Austria, Denmark, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States.10 The percentage of people involved in a legal problem who reported that it was difficult or impossible to pay the costs incurred to resolve it, was around 19%. This percentage is the same as in Italy, and lower than in Greece, from among the countries mentioned.

Poor access to legal services and protracted legal resolution processes, due to factors such as a lack of financial means, the adoption of delaying tactics by legal professionals, a lack of information on how best to address a legal problem, and a negative view on the cost effectiveness of legal professions, result in unmet legal needs which in turn lead to an overall welfare loss.

The regulation of the legal profession has been the topic of several OECD Roundtable discussions – see OECD (2016), Section 4. OECD (2007) also provides an in-depth discussion of the competition aspects of the regulation of professional services. Further discussion on the rationale for legal services regulation, and associated competition considerations, can also be found in the OECD (2007) report.11

Box 4.1. Effect of deregulation of the legal professions in Poland

The study The Effects of Reforms Liberalising Professional Requirement in Poland (Rojek and Masior 2016), analyses the effects of professional deregulation (or changes in regulation) in Poland in a 10- year period (from 2005 to 2014), covering 22 different professions, including advocates, legal advisers and notaries.

For legal professions, deregulation initiatives took effect in 2005, 2009 and mid-2013. These initiatives introduced “objective and transparent” rules of access to the professions, and “disrupted” quantitative limits to access the profession, while slightly reinforcing governmental supervision to mitigate conflicts between self-corporate interests and the public interest.

In the case of advocates and legal advisers, changes were introduced in the examination procedures to join the professional associations to reduce the scope of discretion in the decisions over access. The Ministry of Justice was made responsible for the execution of access exams. Inter-professional mobility was increased, contributing to an inflow of judges and prosecutors into the advocate and legal adviser professions. For the period 2010 to 2015, prices of legal services increased at a rate comparable with other consumer services and the quality of advocate services seemed to increase between 2010 and 2013, based on a lower inflow of complaints, motions to disciplinary prosecutors and appeals to the National Bar Council. The number of active advocates during this same period more than doubled. The effects of these deregulation initiatives on the level of earnings enjoyed by advocates and legal advisers remain inconclusive.

In the case of notaries, deregulation initiatives took effect in 2005, 2006, 2009 and mid-2013. Simplified rules of entry resulted in higher numbers of new notaries supplying their services in the market. Between 2009 and 2014, notaries’ earnings decreased significantly and average profits for established notaries declined by 38%. The percentage of younger notaries increased during this same period 2009-2014.

As a consequence, from 2005 to 2016, the number of advocates and legal advisors almost doubled and the quality of advocate services increased between 2010 and 2013, based on the lower number of complaints, motions to disciplinary sanctions and appeals to National Bar Council, which between 1989 and 2010 was in a negative upward trend.

Source: Rojek et al, Warsaw School of Economics, 2016 “The Effects of Reforms liberalising Professional Requirements in Poland”, Report funded by the EC/DG Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs.

4.3. Overview of legal services

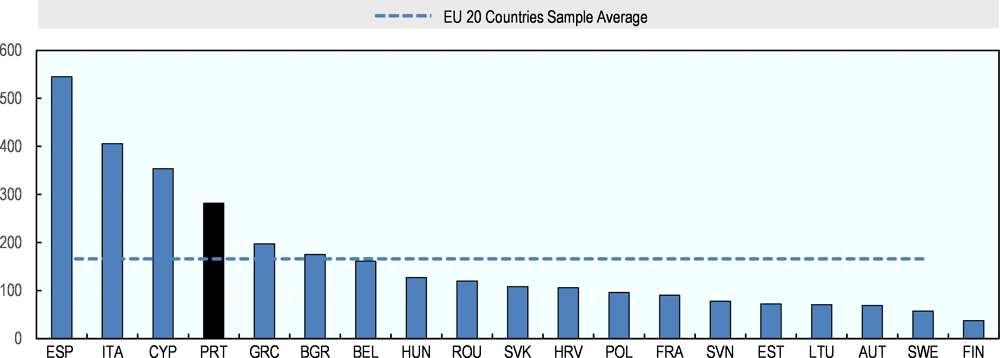

In 2015, legal services to firms accounted for EUR 1 245 million, almost 10% of all services to firms, an increase of 2% since 2008 (EUR 1 172 million).12 In 2017 there were 1 765 law firms13 operating in Portugal and, in 2016, the most recent data available, there were 42 firms composed of solicitors and 25 of solicitors and enforcement agents together. In 2017 there were 50 454 lawyers registered with the Bar Association, of which 30 593 lawyers were active members. Per 100 000 inhabitants, the number of active lawyers has grown from 96 in 1999 to 297 in 2017, almost twice the EU average (Figure 4.1).14 Regarding notaries, in 2017 there were around 375 active and 44 professionals waiting for a licence. In 2016, there were 3 559 solicitors active in Portugal.

Figure 4.1. Active lawyers per 100 000 inhabitants, 2015

Note: There is no information available for Germany and Denmark on the CCBE website. The United Kingdom was not considered due to the particularity of having barristers and solicitors.

Source: Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe (CCBE) and AdC/OECD own calculations. For Greece only members of the Athens Bar Association are included. The numbers of lawyers for Spain is likely to include all registered lawyers, including those currently with suspended practice.

While there is a prevalent argument in Portugal claiming that there are "too many lawyers", this seems to be grounded in an erroneous interpretation of the way the market for legal services works or ought to work. This market is not static nor is its dimension pre-defined. Baarsma et. al. (2008) reports a positive relation between the level of regulation and the number of lawyers per inhabitant. In countries where the profession of lawyer is less regulated, the number of lawyers per 100 000 inhabitants is lower than in countries where the profession is more regulated. According to the same study, this result may be partially due to the stronger competition lawyers face in less regulated countries, from outside professionals, e.g., other qualified jurists. Also, the fact that there are more lawyers per 100 000 inhabitants does not lead to lower prices charged for services as long as the entry into the market is restricted and activities are reserved.

4.3.1. Regulation of lawyers

Practising lawyers in Portugal have to be registered members of the Portuguese Bar Association.15 The bar association is the professional regulatory body with control over access to and exercise of the law profession, including disciplinary powers over its members.16

The title of “lawyer” is a protected professional title, implying that the use of the title is subject to a particular professional qualification by virtue of legislative, regulatory or administrative provisions. Lawyers are assigned certain “reserved activities”, either exclusively, or in some cases shared with notaries and solicitors.17 The judicial mandate, whereby lawyers represent clients before administrative authorities including tax authorities, and before all courts, is a task exclusive to lawyers, except in cases specifically opened to solicitors (see below).

Lawyers from other EU member states who wish to establish their legal practice in Portugal under the professional title gained in their home country, are subject to prior registration with the Portuguese Bar Association. They can then exercise their legal practice in Portugal under the Portuguese title of “Advogado”, and they are subject to the same professional and ethical rules applicable to all lawyers belonging to the Portuguese Bar Association. Should these lawyers wish to provide only occasional legal services, they should give notification of their activity in Portugal to the bar association.18

4.3.2. Regulation of notaries

In Portugal, the privatisation of notarial activity was initiated in 200419 concomitantly with the creation of the Professional Association of Notaries (Ordem dos Notários)20 that regulates access to and exercise of notarial activity. All practising notaries must be registered in the Association.21 22 Membership is open to those with the title of “notary” and professional firms formed exclusively by members of the Order.

The title of “notary” is granted to university law graduates who have successfully concluded their internship programme, after a public licence-awarding procedure run by the Ministry of Justice. This recruitment involves a written and oral exam to assess the candidates’ capacity to exercise the profession.

Notarial activity can only be performed in notarial offices, meaning that titled notaries need to obtain a licence for a notarial office before they can exercise their profession. However, the licences are subject to strict quotas. Titled notaries without a licence may join a waiting list, which included around 44 professionals by end-2017 (compared to just 300 active notaries), or they may work as clerks in a notarial office run by a licensed notary. In general, each notary is only allowed to have one notarial office licence, but some notaries also run other notarial offices on a temporary basis (e.g. due to the retirement of their licensed notaries).

The professional association of notaries has created a Compensation Fund financed by members’ contributions and fines imposed on members by the association to ensure the coverage of notaries’ presence throughout Portugal. This Compensation Fund awards a benefit to notaries running a notarial office located in less populated municipalities. In 2017, 18 notarial offices benefited from the Compensation Fund representing 4.45% of the total number of active notarial offices.

Starting in 2011, there was a significant decrease in the notarial activity in GVA, from around EUR 112 million in 2007 to around EUR 40.5 million at current prices.23 This can be explained by the financial crises and the subsequent contraction in the volume of real estate commercialised during the crisis.

4.3.3. Regulation of solicitors

Solicitors provide professional legal advice and act on behalf of their clients before a notary or a legal administrator representing the state.24 However, when compared to lawyers, solicitors face some limitations on the judicial mandate they can practise, imposed by their professional association bylaws and by procedural law.

In civil proceedings, a solicitor can exercise a judicial mandate in cases in which a lawyer’s participation is not mandatory, and as such the involved parties may also represent themselves or be represented by probationary lawyers. Solicitors by themselves cannot practise the judicial mandate in cases under court jurisdiction in which an ordinary appeal is admissible. This is the case when the amount at stake is above EUR 5 000; any cases in which an appeal is always admissible, regardless of the value; or proposed appeals and cases presented to higher courts. In criminal cases, the solicitor may exercise a judicial mandate when the intervention of a lawyer is not mandatory.25 26 27 28 29

Solicitors’ activities are regulated by the bylaws of the professional association of solicitors and enforcement agents which regulate the access to both professions as well as their exercise, and endow the professional association with disciplinary powers over its members.30 The professional association includes two separate professional colleges, one for each profession.

Solicitors have to be a registered member of the College of Solicitors to exercise their profession. The candidates must have a degree in law or in solicitor’s practice, and successfully complete a professional internship programme. Enforcement agents must be registered in the College of Enforcement agents (see Box 4.2).

Box 4.2. Enforcement agents

The regulation of enforcement agents aims to guarantee that they perform the procedural acts for which they are responsible in a diligent manner, provide the court and the different parties with the necessary information in accordance with the law, render an account of the performed activities, promptly deliver the amounts, objects or documents held by them as a result of their performance as executors, and assure they do not exercise activities that are incompatible with their profession of enforcement agent.

Mandatory enrolment in the college of enforcement agents of the professional association depends on the following requirements: possession of Portuguese nationality and enrolment in the college up to three years after having successfully completed the internship programme.

The requirement of Portuguese nationality was taken by drawing a parallel with public magistrates. It excludes from the market professionals from other EU Member States who may understand and speak Portuguese fluently. This requirement should be replaced by one that requires clear evidence of their adequate knowledge of the Portuguese language and of the Portuguese judicial system.

Enforcement agents, who have practised for more than three years up to the publication of these Bylaws, must undergo the examination provided for in no. 3 of Art. 115 and obtain a favourable opinion from the CAAJ to be exempted from the internship.

4.3.4. Restrictions on advertising

Advertising is defined as the making of a representation in any form in connection with a trade, business, craft or profession in order to promote the supply of goods or services, including immovable property, rights and obligations.31

Description of the barrier

Lawyers, solicitors, notaries and enforcement agents are not allowed to:32 33 34

publicly advertise persuasive, ideological, self-aggrandizement and comparative contents;

mention the quality level of the office or practice (this also applies to customs brokers);35 and

engage in unsolicited direct publicity.

Harm to competition

The regulations limit the freedom of legal professionals to advertise their own activity, which might be especially harmful for those not yet well established in the market. Advertising services to inform and potentially gain clients is crucial to promote competition and to establish a level playing field among professionals in the market. Advertising legal services may also lead to lower prices for legal services as it spurs competition among providers.

Advertising can improve consumer information and reduce search costs leading to more competition among established firms. Nelson (1970; 1974) Grossman and Shapiro (1984) and Stahl (1994) suggest that advertising can have pro-competitive effects to facilitate entry. Following OECD (2007), there are no well-founded arguments against permitting advertising that is truthful. Furthermore, studies have found that restrictions on advertising lead to higher prices (OECD, 2007).

In 2007, the Canadian Competition Bureau (CCB) stated that there is empirical evidence of the effect of advertising restrictions on the price and quality of professional services (including accountants, lawyers, optometrists, pharmacists and real estate agents). Restrictions on advertising increase the price of professional services, increase professionals’ incomes and reduce the entry of certain types of firms. Additionally, there is little evidence of the positive relationship between advertising restrictions and quality of services, even though it may result in fewer consumers using the service.36 37

Directive 2006/114/EC states that only misleading and unlawful comparative advertising can lead to distortion of competition within the internal market. The interdiction of misleading advertising is foreseen under national legal regimes.38 To go beyond the EU benchmark, in particular ruling out publicity of comparative contents in a generic way for specific professions, will have an adverse effect on consumer choice and no clear benefits.39

Recommendation

Any prohibition or restriction for legal professions beyond the prohibition on misleading and unlawful comparative advertising (already covered in other legal texts) should be removed.

4.3.5. Licence quotas and geographical barriers for notaries

Description of the barrier

To have a notarial office, the notary needs to obtain a licence from the Ministry of Justice, following the established quotas per region.40 Notaries are restricted geographically as they are prohibited from cannot actively seek to exercise their practice over persons and property from another municipality. They are restricted to being a passive recipient of service requests from the clients.41 Furthermore, several additional legal procedural rules also establish exclusive powers of notaries located within the boundaries of a municipality. 42

Harm to competition

Licence quotas for notaries officially aim to ensure that all people across the national territory have access to notarial services, as these services are mandatory for certain acts, such as property transactions. On the other hand, to ensure that a notary is willing to establish an office in a remote or weakly populated area, the quota system aims to guarantee a minimum income for the local notary, complemented with the current Compensation Fund.

The number of notaries and the localisation of their offices are included in a notarial map approved by a decree-law, after consultation with the Professional Association of Notaries and the Council of Notaries.43 The state determines the total number of notaries to be licensed and the way they will be distributed across the different municipalities. It establishes a territorial segmentation for the attribution of notarial licences, where each notary can only hold one licence. The latest version of the notarial map dates back to 2004.44 The map clearly needs to be brought up-to-date to reflect new territorial, economic and demographic characteristics. The 2004 map indicates that around 72% of all the municipalities across the country have only one licence (221 out of 310 municipalities).

The current quota model clearly restricts the number of notaries in the market and may reduce the incentives of existing notaries to compete on price and quality with each other for the provision of services. It also prevents competition between notaries in a one-licence area as no new notary can enter the market and seek custom.

Limiting the number of licences to operate a notarial office as defined in the notarial map restricts the overall number of professional titles that are available to be granted. This leads to long waiting times for prospective notaries working as clerks, while no competitive pressure is exerted on incumbents.

These restrictions are even more difficult to justify in the case of municipalities with higher population density and higher incomes (urban areas and along Portugal's attractive coastal and touristic areas). In these cases, quota restrictions currently allow incumbents to pick and choose their clients with little incentive to improve services, innovate or adapt to the market in other ways.

A less restrictive and more market-oriented mechanism for the allocation of notaries throughout the national territory would encourage lower prices, higher quality and innovation as a result of greater competition. Such a mechanism is unlikely to imply more difficult or more expensive access to notarial services. On the contrary, greater consumer welfare would arise not only from more but also better services being available.

Box 4.3. Recommendation 1/2007 by the Portuguese Competition Authority

In 2007 the Portuguese Competition Authority (AdC), under its supervisory and regulatory powers, issued Recommendation 1/2007 containing several measures to reform the notaries’ legal framework and promote competition in notarial services. This recommendation was the culmination of a series of initiatives taken since 2005, including the commission of a study on the notarial activity carried out by academics from the Centre for Studies in Public Law and Regulation (CEDIPE)/University of Coimbra, and the organisation of a workshop with the participation of several stakeholders.

The AdC issued the following recommendations: (i) eliminate the quota plus licensing model and the regime of territorial jurisdictions; (ii) establish the freedom to open extensions of notarial offices; (iii) eliminate the prohibition of collaboration between notaries and the possibility of the same notary managing more than one notarial office; (iv) eliminate the prohibition of the notary publicising his activity in order to attract clients; (v) liberalise the prices for services provided by private notaries; (vi) eliminate the Compensation Fund.

Regarding the existence of a quota regime in the attribution of notarial licences across the different municipalities, the public interest in securing an adequate geographic coverage of notarial services, in particular in less economically developed and less populated municipalities, can be ensured through measures less restrictive of competition. However, the AdC considered that if the implementation of recommendations (i) and (ii) did not ensure an adequate geographical coverage of notarial services, then a public tender could be launched for the provision of such services, regarded as public services, in the affected geographical areas, with the award of a compensation financed by the state.

Regarding recommendation (v), the AdC proposed the generalization of a free price regime to acts performed by private notaries who already face significant competition from other professionals. This competition resulted from the extension of the range of entities legally qualified to practise such acts or from the progressive reduction in the number of legal acts subject to public deed. However, the AdC also recommended the adoption, over a transitional period, of a system of maximum prices for services that remained within the exclusive competence of notaries and whose social relevance justified the need to guarantee universal access. At the same time, quantitative restrictions on access to the profession would be maintained, through the imposition of a quota regime.

The AdC also recommended a three-step timetable for the implementation of the above measures, lasting a total of five years plus the time needed to eliminate the existing table of fees, notary charges and the Compensation Fund.

Sources: Recomendação N.º 1/2007 – “Medidas de reforma do quadro legal do notariado, com vista à promoção da concorrência nos serviços notariais” (in PRT).

The need for quotas has largely been superseded by technology and the gradual removal of reserved activities as the exclusive preserve of notaries. The need for the physical presence of a notary is therefore less pressing, as many acts can be dealt with over the internet and by email, or by lawyers and solicitors. The Portuguese government has already recognised this. As part of the Portuguese "Simplex" e-government programme, citizens have been given a unique identity card and "e-identity" that can be used to officially sign documents remotely. The Portuguese government should consider internet availability and use their e-government programme to facilitate the use of notarial services remotely, thereby reducing the number of remote geographic areas identified as in need of notaries with a unique licence.

Such alternative solutions may better balance competition and universal access to notarial services, as twin public goods. One solution put forth by the Portuguese Competition Authority’s Recommendation 1/2007 (see Box 4.3) calls for widening the range of legal services a notary may provide in a disadvantaged geographical area.

Recommendation

Following the AdC's Recommendation 1/2007 (see Box 4.3) and more recent international developments, such as the legal reform in France known as the Macron Law (Loi Macron, see Box 4.4 below), a technical study on the current organisation of notarial services in Portugal needs to be carried out. The objectives of such a study are to explore alternatives that would increase professional mobility and clients’ freedom of choice, while still guaranteeing universal access to notarial services. Therefore is the following is recommended:

1. Abolish the existing licence quotas for establishment of a person(s) as a notary. Alternatively,

2. Study the potential demand and economic viability for notarial services, taking into account population density, economic activity, dynamism of the local real-estate market, demand for other services provided by notaries and the existence of alternative internet solutions. Based on the data:

i. Identify high-density high-activity areas that can sustain competition in notarial activities (typically Lisbon, Porto, Faro, high-tourism areas, highly-industrialised areas) and fully liberalise the establishment of notarial offices there.

ii. In low-density areas, allow for open competition for the establishment of one or two offices per areas (or whichever density is determined by the study).

3. Revisit the existing Compensation Fund and find alternative ways to guarantee the delivery of notarial services in low-density areas, taking into account the fact that many notarial acts can also be practised by both lawyers and solicitors who may also practise in those areas.

Box 4.4. Reform of the profession of notary in France (Loi Macron)

In June 2016, following the French Law 2015-990 of 6 August 2015 for the growth, activity and equality of economic opportunities (also known as the “Macron law”), the French Competition Authority (FCA) issued an opinion on the reform of the establishment of notarial offices in France.

The new reform should increase access to and competition in notarial services in France. “Three objectives guided the formulation of the recommendations:

(1) To improve territorial coverage, in order to bring notaries closer to the population and the companies located in areas currently poorly served by public transportation;

(2) To open up the notarial profession, giving newly graduated notaries the opportunity to set up their own offices and offer new services;

(3) To preserve the economic viability of existing offices, especially in rural areas.”

This would lead to a more market-oriented and efficient allocation of a greater number of notarial offices across the country, resulting also in enhanced territorial coverage and better access to the profession

The FCA recommended the liberal establishment of 1 650 new notary offices by 2018, an increase of 20% compared with the current 8 600 (2017). Even taking into consideration the number of salaried notaries, this figure will remain below the one suggested by the Superior Council of French Notaries (Conseil Supérieur du Notariat - CSN) in 2008, which had publicly committed to reaching 12 000 notaries by 2015.

Across the entire country, the FCA has identified 247 so-called "green zones", or free-establishment areas (out of a total of 307 areas). These are areas that were found to be economically viable and where demand for notarial services was found to be high. The 1 650 new offices will be attributed by a draw among qualified applicants, and shared out proportionally according to the needs identified locally.

The FCA made a further 23 recommendations to the Ministry of Justice in order to ensure the sustainability of the system, to improve access to notarial offices (particularly for women and the younger generation), to lower the barriers to entry for future applicants, and to ensure continuity in the quality of service, for the benefit of those who use it.

The FCA had undertaken its reform proposals based on data demonstrating a strong increase in notarial activities (up by 6.3% year on year in 2015, in France). This prompted an analysis of the need and demand for notarial services, which indicated that a large number of areas were lacking in notaries, whereas recent qualified notaries were not able to establish their own offices, but had to wait for existing offices to be vacant (mostly as a result of retirement).

Sources: French Competition Authority de la Concurrence (France), Press Release, 9 June 2016 “Freedom of establishment for notaries”.

Bylaw jointly by the Ministries of Justice and the Economy on 20 September 2016.

4.3.6. Maximum fees for notaries

Description of the barrier

The notarial acts performed exclusively by notaries are governed by a maximum price regime, except those set for inventory procedures that are under a fixed fee regime.45 All other acts have free fees.

Harm to competition

Maximum and fixed price regimes limit the incentives to compete and innovate. Even though maximum price regimes allow for price competition, they often serve as a focus point to co-ordinate prices.

Nevertheless, according to stakeholders, the regulation of fixed prices related to the inventory process, such as in a judicial separation process, might be justified on exceptional public interest grounds to guarantee economic access to inventory processes equally by all people.

The existence of maximum prices in exclusive notarial activities intends to guarantee universal access to these services independently of the clients’ income level. Notary services exhibit characteristics of public goods, which can lead to positive externalities. Because public goods tend to be under-produced, the state usually establishes regulation on the provision of such services. Additionally, it is claimed that price control guarantees a notary's impartiality and independence in the provision of a public service, as they wouldn't have to negotiate prices with their clients.

In a competitive market, prices tend to reflect more closely the costs of the services provided, and do not necessarily jeopardise the quality of those services.

In its Recommendation 1/2007, the AdC proposed the adoption of a system of maximum prices during a transitional period for services which remain within the exclusive competence of notaries and whose social relevance justified the need to guarantee universal access. This regime would be phased out as the quantitative restrictions imposed by the quota system were phased out.

Other alternatives, rather than fixing maximum prices, may be adopted to overcome any lack of information from the demand side, such as the publication of historical or survey-based price information by independent parties, e.g. consumer associations. This would improve transparency and allow greater competition in prices.46 The same principle applies when the regulator opts for establishing maximum prices, based on the attempt to avoid excessive prices charged to consumers, in particular when the regulator wants to guarantee universal access to notarial services.

Recommendation

The maximum prices regime should be revisited, with the aim to gradually phase them out as appropriate. This view also reflects the position of the AdC.

References

Andrews, P. (2002), “Self-regulation by professions—the approach under EU and US competition rules”, European Competition Law Review, Vol. 23, No. 6, pp. 281-285.

Baarsma, Barbara et al. (2008), “Regulation of the legal profession and access to law: an economic perspective”, Report commissioned by the International Association of Legal Expenses Insurance (RIAD), Amsterdam.

Canadian Competition Bureau (CCB) (2007): “Self-regulated professions: Balancing competition and regulation”, at: http://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/eng/02523.html

Canton, E., et al (2014), “The Economic Impact of Professional Services Liberalization”, European Commission, DGEcoFin, European Economy Series, Economic Papers No. 533, September.

Decker, Christopher and George Yarrow (2010), “Understanding the economic rationale for legal services regulation”, a Report from the Regulatory Policy Institute for the Legal Services Board, October.

European Economic and Social Committee, 2014, “The State of Liberal Professions Concerning their Functions and Relevance to European Civil Society”.

Garoupa, N. (2004), “Regulation of Professions in the US and Europe: A Comparative Analysis”, WP George Mason University Law School, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, and Centre for Economic Research , London.

Garoupa, N. (2008), “Providing a Framework for Reforming the Legal Profession: Insights from the European Experience”, European Business Organization Law Review, Vol. 9, pp. 463-495.

Garoupa, N. (2014), “Globalization and Deregulation of Legal Services”, International Review of Law and Economics, Vol. 38, Supplement, June, pp. 77 – 86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2013.07.002.

Goldsmith, Jonathan (2008), “The impact of economic values on the future of the legal profession”, Speech given to the General Assembly of the Swedish Bar, 13 June. https://www.advokatsamfundet.se/globalassets/advokatsamfundet_sv/nyheter/goldsmith_fullmaktige.pdf.

Grossman, G. and C. Shapiro (1984), “Informative Advertising with Differentiated Products”, The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 51(1), pp. 63–81.

Iossa, E. and B. Julien (2012), "The market for lawyers and quality layers in legal services", The RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 43, No. 4 (Winter 2012), pp. 677-704.

Jones, A. and B. Sufrin, B. (2014), “EU Competition Law: Text, Case and Materials” (5th edition) Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Kanke, Renee N. (2012), “Democratizing the Delivery of Legal Services”, Ohio State Law Journal, Vol. 73, pp. 1-46.

Kleiner, M. M. (2000), “Occupational Licensing”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 14, No. 4, autumn, pp. 189-202.

Kleiner, M. M. and R.T. Kudrle (2000), “Does regulation affect economic outcomes? The case of dentistry”, Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 43, No. 2, pp. 547-582.

Kleiner, M. M. (2006), Licensing Occupations: Ensuring Quality or Restricting Competition? W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, Kalamazoo, MI, http://dx.doi.org/10.17848/9781429454865

Kleiner, M. M. and A. Krueger (2008), “The Prevalence and Effects of Occupational Licensing”, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Working Paper, No. 14308, September.

Kleiner, M. M. and A. Krueger (2009), “Analysing the Extent and Influence of Occupational Licensing on the Labour Market”, NBER, Working Paper No. 14979, May.

Kleiner, M. M. (2011), “Occupational Licensing: Protecting the Public Interest or Protectionism?,” Policy Paper No. 2011-009, Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, Kalamazoo, MI.

Kox, Henk L.M. (2012), "Unleashing Competition in EU Business Services", CEPS Policy Brief, No. 284, 24 Sept.

Leland, H.E. (1979), “Quacks, lemons and licensing: a theory of minimum quality standards”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 87, pp. 1328-1346.

Monteagudo, J., A. Rutkowski, A., and D. Lorenzani (2012), “The Economic Impact of the Services Directive: A first assessment following implementation”, European Commission, DGEcoFin, European Economy Series, Economic Papers No. 456, June.

Nelson, Phillip (1970), “Information and Consumer Behaviour”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 78 (2), pp. 311-329.

Nelson, Phillip (1974), “Advertising as Information”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 82(4), pp. 729-754.

OECD (2016), "Hearing on Disruptive Innovations in Legal Services" Working Party 2 on Competition and Regulation, DAF/COMP/WP2/WD(2016), June.

OECD (2014), OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Greece, OECD Competition Assessment Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264206090-en. Box. 5.1. Literature review of the effect of advertising on retail prices.

OECD (2010), OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform: Italy 2009: Better Regulation to Strengthen Market Dynamics, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264067264-en.

OECD (2007), “Competitive Restrictions in Legal Professions”, DAF/COMP(2007)39, version from April 2009.

Optimisa Research (2013), “Consumer use of legal services – understanding consumers who don’t use, choose or don’t trust legal services providers”, Report of Qualitative Research Findings prepared for the Legal Services Board, UK, April.

Pagliero, M. (2011), “What is the objective of professional licensing? Evidence from the US market for lawyers”, International Journal of Industrial Economics, Vo. 29, pp. 473-483.

Paterson, I., M. Fink and A. Ogus (2007), “Economic Impact of Regulation in the Field of Liberal Professions in Different Member States”, Parts I & II, WP Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna, and ENEPRI WP No. 52/February.

Persico, N. (2014), “The Political Economy of Occupational Licensing Associations”, Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 213-241.

Rojek, M. and M. Masior (2016), “The Effects of Reforms Liberalising Professional Requirements in Poland”, Report funded by the EC/DG Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, Warsaw School of Economics (SGH).

Semple, Noel, R.G. Pearce and Renee N. Knake (2015), “A Taxonomy of Lawyer Regulation: How Contrasting Theories of Regulation Explain the Divergent Regulatory Regimes in Australia, England and wales, and North America”, Legal Ethics, Vol. 16(2), pp. 258-283. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5235/1460728X.16.2.258.

Shaked, A. and J. Sutton (1981), "The Self-Regulating Profession", Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 48, pp. 217-234.

Shapiro, C. (1986), "Investment, Moral Hazard and Occupational Licensing," Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 53, pp. 843-862.

Stahl, Dale O. (1994), “Oligopolistic pricing and advertising”, Journal of Economic Theory, Vol. 64, pp. 162- 177.

Stephen, Frank (2002), “The European Single Market and the Regulation of the Legal Profession: An Economic Analysis”, Managerial and Decision Economics, Vol. 23, pp. 115–125.

Stephen, Frank (2014), “An Economic Perspective on the Regulation of Legal Service Markets”, Evidence submitted to the Justice 1 Committee’s Inquiry into the Regulation of the Legal Profession, UK.

Stephen, Frank (2016), “A Revolution in ‘Lawyering’? Implications for Welfare Law of Alternative Business Structures”, in Ellie Palmer et al (Eds.), Access to Justice: Beyond the Policies and Politics of Austerity, Hart Publishing, Oxford.

Susskind, R. and D. Susskind (2015), The Future of the Professions: How Technology Will Transform the Work of Human Experts, Oxford University Press.

Tavares, António and Miguel Rodrigues (2013), “From civil servants to liberal professionals: an empirical analysis of the reform of Portuguese notaries”, International Review of Administrative Sciences, Vol. 79(2), pp. 347-367.

Thornton and Timmons (2015), “The de-licensing of occupations in the United States”, Monthly Labor Review, May issue.

Annex 4.A. Benefits to consumers

Consumer welfare can increase to as much as EUR 31.90 million with the lifting of restrictions arising from regulations applicable to the legal professions, making them more competitive with regard to entry and exercise requirements, allowing for more competition between professionals.

Annex Table 4.A.1. Impacts of legal services on all firms in Portugal, 2015

|

Price changes |

Increase in consumer welfare (W) in EUR when ePD=2 |

|---|---|

|

∆PP=0.20% |

2 494 968 |

|

∆PP=0.40% |

4 999 896 |

|

∆PP=0.50% |

6 256 095 |

|

∆PP=0.75% |

9 407 486 |

|

∆PP=1.00% |

12 574 439 |

|

∆PP=1.50% |

18 955 034 |

|

∆PP=2.00% |

25 397 878 |

|

∆PP=2.50% |

31 902 971 |

Source: Data from INE (2017), “principais indicadores económicos, segundo a atividade principal da empresa”, https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_destaques&DESTAQUESdest_boui=281447433&DESTAQUESmodo=2 (accessed on 23 March 2018) and methodology presented in Annex A.2.

Notes

← 1. For an overview of legal professions across all EU Member States see: https://e-justice.europa.eu/content_legal_professions-29-en.do. The EU Single Market/Regulated Professions Database defines legal practice in Portugal as the exercise of the legal mandate; legal advice; preparation of contracts and the practice of preparatory acts leading to the establishment, modification or termination of legal transactions, particularly those charged with the registries and notary offices; negotiation aimed at credit recovery; terms of office under the claim or objection to administrative or tax acts. Furthermore, lawyers can also pursue activities related to the representation or defence of a client in legal proceedings. Moreover, lawyers can assist citizens before any kind of authorities in defence of citizens’ rights. In addition lawyers are also responsible for studying cases and processes and interpreting laws, ordinances, regulations regarding doctrine and case law.

See http://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/regprof/index.cfm?action=regprof&id_regprof=1481

← 2. See Law 145/2015.

← 3. Created by Decree-Law 27/2004.

← 4. See Law no. 154/2015, from Sept 14th.

← 5. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/blogs/competition-matters/2015/02/supreme-court-self-interested-boards-must-be-actively.

← 6. See the Civil and Social Justice Panel Survey (CSJPS) results as reported in the Legal Services Board Report, 2016.

← 7. See Optimisa Research (2013) for the Legal Services Board.

← 8. See Legal Services Board (2016), pp. 76 and 77.

← 9. For a useful discussion of the impact of economic values on the legal profession, see Goldsmith, 2008. For an economic analysis of regulation of the legal profession and access to law, see Baarsma et al., 2008.

← 10. See https://worldjusticeproject.org/sites/default/files/documents/Access-to-Justice-Portugal.pdf.

← 11. Most recently the issue was discussed in the OECD June 2016 Hearing on Disruptive Innovations in Legal Services in the Working Party 2 on Competition and Regulation. Further discussion on the rationale for legal services regulation and some of its impacts, can be found in Andrews, 2002; Decker and Yarrow, 2010; Garoupa, 2004, 2008, 2014; Iossa & Julien, 2012; Kanke, 2012; Kleiner, 2000, 2006, 2011; Kleiner & Kudrle, 2000; Kleiner & Krueger, 2008, 2009; Kox, 2012; Leland, 1979; Monteagudo et al , 2012); Pagliero, 2011; Paterson et al. 2007; Persico, 2014; Semple et al, 2013; Shaked & Sutton, 1981; Shapiro, 1986; Stephen, 2002, 2014, 2016; Thornton & Timmons, 2015.

← 12. For lack of proper data, we have not been able to compute a “Consumer Price Sub-Index for Legal Services” for Portugal, as is available in the United States. The aim would be to compare the evolution of this Consumer Price Sub-Index with that of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to determine whether legal services have become relatively more or less expensive for consumers over time when compared with the bundle of goods and services considered for the calculation of the CPI. The Portuguese Statistics Bureau (INE) adopts the COICOP (“Classification of individual consumption by purpose”) methodology, from which we can select the sub-category “Other services n.e.c. (i.e., not elsewhere classified)” from the category “Miscellaneous goods and services”. However, apart from including fees for legal services, this sub-category also includes charges and payments for several other miscellaneous services which renders its price index unsuitable as a proxy for the non-existent Consumer Price Sub-Index for Legal Services. An alternative would be to conduct a survey over a representative sample of legal service providers on the prices charged for the different services provided, which falls beyond the scope of this Project.

← 13. Of this total number of law firms, 14 are registered as branches of foreign law firms, either from Spain or from the United Kingdom.

← 14. In 2015, there were 106 other European lawyers working in Portugal, registered under their home-country professional title. This number compares with 80 in Austria, 125 in the Czech Republic, 1 020 in France, 123 in Greece, and 4 521 in Italy (as of July 2014). Out of those 106 lawyers, 75 were from Spain, 10 from Germany, 8 from the United Kingdom, 7 from France, 2 from Sweden, and 1 each from Italy, Austria, the Netherlands and Poland (see http://www.ccbe.eu/fileadmin/speciality_distribution/public/documents/Statistics/EN_STAT_2015_Number_of_lawyers_in_European_countries.pdf).

← 15. ‟As regards members of the Bar [i.e., of the various Bars in the different EU Member States], it has consistently been held that, in the absence of specific Community rules in the field, each Member State is in principle free to regulate the exercise of the legal profession in its territory (Case 107/83 Klopp [1984] ECR 2971) and Case C-3/95 Reisebüro Broede [1996] ECR 1-6511). For that reason, the rules applicable to that profession may differ greatly from one Member State to another” - See Jones, A. & Sufrin, B., 2014. P. 217.

← 16. As established by its bylaws, approved by Law no. 145/2015.

← 17. See “Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on a proportionality test before adoption of new regulation of professions,” COM(2016) 822 final, 10.Jan.2017, Art. 3, page 18.

← 18. Out of those 106 lawyers, 75 were from Spain, 10 from Germany, 8 from the United Kingdom, 7 from France, 2 from Sweden, and 1 each from Italy, Austria, the Netherlands, and Poland. In 2015, there were 106 other European lawyers working in Portugal, registered under their home-country professional title. This number compares with 80 in Austria, 125 in the Czech Republic and 123 in Greece (as of July 2014). Source : http://www.ccbe.eu/fileadmin/speciality_distribution/public/documents/Statistics/EN_STAT_2015_Number_of_lawyers_in_European_countries.pdf.

← 19. See Decree-Law 26/2004 and Decree-Law 27/2004.

← 20. For an analysis of the recent reforms of Portuguese notaries, see Tavares and Rodrigues, 2013.

← 21. See the Professional Association of Notaries' own bylaws (in Annex I to Law 155/2015), the Notarial Statutory Law (in Annex II to Law 155/2015), and the legal framework for the inventory process (Law 23/2013).

← 22. By Decree-law 207/95, lawyers, solicitors and other entities were allowed to practice several notarial acts previously reserved for notaries.

← 23. See INE (Instituto Nacional de Estatística/National Statistics Institute) and PORDATA. INE data on economic activity by subclass - CAE Rev. 3, was extracted on 22 Nov 22 2017.

← 24. See Law 49/2004. It defines the meaning and scope of lawyers’ and solicitors’ own, or reserved, acts and typifies the crime of unlawful practice of legal acts.

← 25. See Art. 40 of the Code of Civil Procedure, although in accordance with paragraph 2 of this article, the solicitor is authorised to submit certain requirements. In cases where a lawyer’s participation is not mandatory, solicitors, law interns and the parties themselves may represent themselves in court – see Art. 42 of Code of Civil Procedure, adopted by Law 41/2013 with amendments.

← 26. See Art. 1(5) of Law 49/2004, Art. 136 of Law 154/2015, and Art. 1(11) of Law 49/2004.

← 27. Art. 42 Code of Civil Procedure, Law 41/2013 with amendments.

← 28. See Art. 64 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, Decree-law 78/87 with amendments.

← 29. On the role played by lawyers, see also Art. 20, Art. 32 and Art. 208 of the Constitution (CRP).

← 30. See Law no. 154/2015, from Sept 14th.

← 31. Art. 3 (1) of the Decree-Law 330/90 (Portuguese publicity code).

← 32. Art. 94(4)(a) (b) (e) of the Law 145/2015.

← 33. Annex I art. 82 of Law 155/2015 "Professional Association of Notaries Bylaws".

← 34. Art. 4 to 14 of Regulation 786/2010 "Publicity and Image of solicitors and enforcement agents".

← 35. Art. 41 of Law 112/2015.

← 36. See Canadian Competition Bureau, 2007, pp. 28-30, including Table 2. http://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/eng/02523.html

← 37. Other professionals, such as nutritionists, are also forbidden to engage in publicity of a comparative nature as such practices may mislead users and encourage the acquisition of services without prior individual diagnosis. Art. 116 of Law 51/2010 as amended by Law 126/2015 "Nutritionists Professional Association Bylaws".

← 38. See in particular the Advertising Code (which transposes Directive 2006/114 /EC), the Unfair Commercial Practices Act (which transposes Directive 2005/29/) and the Code of Industrial Property, focusing in particular on the Unfair Competition provided in Art. 317.

← 39. Recitals 8 and 9 and Art. 4 of Directive 2006/114/EC. ‘Misleading advertising’ means any advertising which in any way, including its presentation, deceives or is likely to deceive the persons to whom it is addressed or whom it reaches and which, by reason of its deceptive nature, is likely to affect their economic behaviour or which, for those reasons, injures or is likely to injure a competitor. ‟Comparative advertising” means any advertising which explicitly or by implication identifies a competitor or goods or services offered by a competitor. Comparative advertising is not forbidden when it compares material, relevant, verifiable and representative features and is not misleading. It is considered to be a legitimate means of informing consumers of their advantage. The directive stresses the need for EU Member States to include criteria of objective comparison of the features of goods and services, which may include price.

← 40. Decree-Law 26/2004, Article 6 (1) (2).

← 41. Decree-Law 26/2004, Article 7.

← 42. For instance only notaries located in the municipality where a succession process is open can execute a legal inventory process (see Article. 3 of Law 23/2013).

← 43. Art. 6(3) and Art. 53(f) Decree-Law 26/2004.

← 44. See annex to Decree-Law 26/2004.

← 45. Ordinance 574/2008.

← 46. OECD, 2009, “Competition and Regulatory Reforms in Professional Services”, in OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform: Italy 2009: Better Regulation to Strengthen Market Dynamics, OECD Publishing.