This chapter examines how the Portuguese school system is managed, and the school opportunities available to students from a variety of backgrounds. In particular it attempts to address the question of whether the system is currently structured to promote the success of all students, including those for whom traditional schooling structures have been ineffective. Portugal has made considerable advances in designing a well-organised school network over the past 15 years, including consolidating many under-resourced schools, investing in some of its school buildings and expanding access for students with special education needs. However, important challenges remain related to shifting demographics, many deteriorating buildings and substantial regional- and school-level inequalities. The chapter makes a number of recommendations to address these challenges, particularly as it relates to the governance of schools.

OECD Reviews of School Resources: Portugal 2018

Chapter 3. The organisation of the school network

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Context and features

System-level governance

As described in Chapter 1, the governance of the Portuguese education system is relatively centralised; however, there has been a long-term, gradual shift towards decentralisation. Decentralisation in the education sector is not isolated but constitutes part of a gradual delegation of responsibilities to the local level in public sectors such as health and transportation. The education sector was one of the first to begin decentralising after the Revolution. Initially, municipalities were responsible for student transportation, meals and facilities management. In 1984, municipalities also became responsible for the construction and maintenance of buildings and equipment for early childhood education and care (ECEC), primary education and adult education, and for managing socio-educational activities (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). During the past decades, more financial authorities and executive powers have been assigned to municipalities concerning school buildings, equipment, non-teaching staff and Curriculum Enrichment Activities (Atividades de Enriquecimento Curricular – AEC) in pre-school and the 1st cycle of basic education. Since 2015, the decentralisation process has been accelerated by the introduction of a four-year pilot with inter-administrative contracts (contratos interadministrativos) between 13 municipalities and the central government. These contracts expand the financial authorities and executive powers of municipalities in such areas as hiring non-teaching staff, social support at school, construction, maintenance and equipping school buildings in the 2nd and 3rd cycles, transport, family support and AEC in pre-school and the 1st cycle of basic education.

The decentralisation process involves multiple subnational entities: inter-municipal associations, municipalities and parishes. Parishes operate under municipal structures. In the Lisbon Municipality, the responsibilities for pre-school education and the 1st cycle of basic education have been further decentralised from the municipal level to the civil parishes, by means of inter-administrative contracts. In this way, Lisbon parishes play an important role in education by undertaking maintenance of buildings, hiring non‑teaching staff, organising study supervision and support, social support, extracurricular activities and school holiday activities, providing meals and launching specific educational projects. Outside Lisbon, parishes have fewer responsibilities, only organising study supervision and support, undertaking small repairs or providing school bus transport.

The decentralisation goal articulated by the current government in education is to provide autonomy to municipalities to distribute funding for current spending on education – except teachers’ salaries – and capital expenditures in schools under their jurisdiction. This would allow municipalities more discretionary power, thereby promoting responsive governance close to the needs of its citizens and efficient in its operation. Current government leaders stressed during the review visit, however, that they intended to keep centralised responsibilities related to teacher hiring, placement and pay, as well as curriculum and the planning of the school network.

Organisation of the school offer

Public schooling

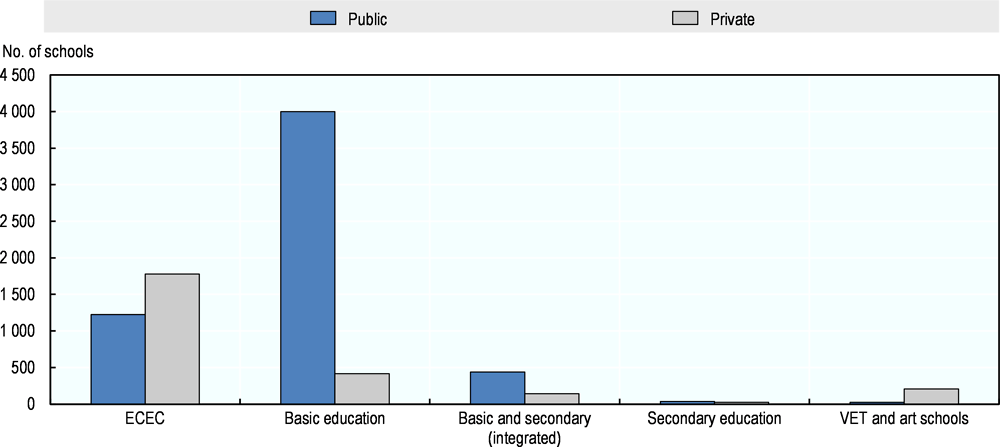

The Portuguese public school offer is organised in three sequential levels described in Chapter 1. Both public and private providers guarantee the school offer in Portugal. The Continental school network consists of 5 729 public schools and 2 569 private schools (CNE, 2017, pp. 45, 49[2]). The public school network is structured in school clusters that integrate schools from different education levels in one organisation. In 2016, there were 713 school clusters and 98 non-clustered schools. Almost all non-clustered schools provide secondary education exclusively (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]).

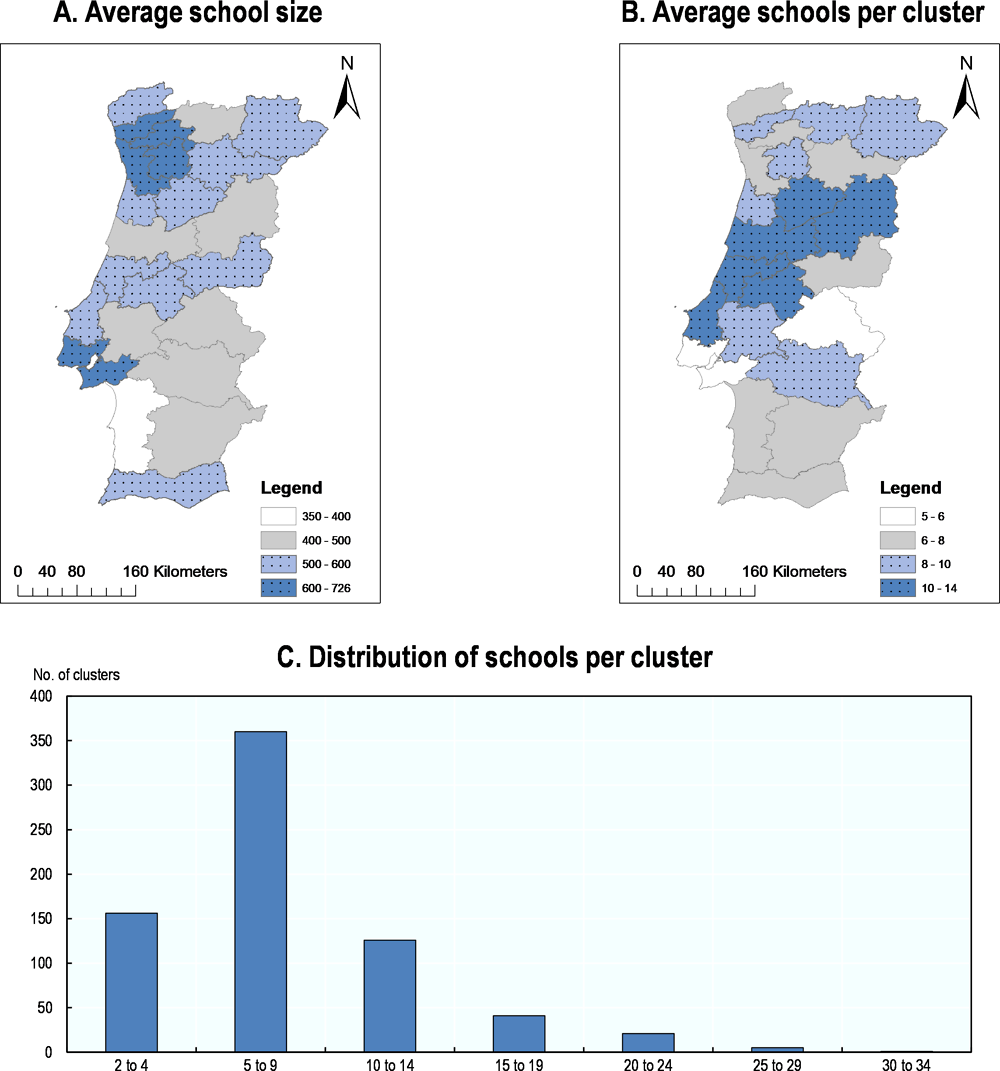

The average individual school size varies significantly across regions, often as a function of the regions’ population density. Panel A of Figure 3.1 shows the average school size by region. In the Lisbon Metropolitan Area and in the upper northwest around Porto, individual schools enrol on average more than 600 students, whereas in the rural northeast and in the western part of Alentejo, schools enrol, on average, 350 to 425 students.

The average size of clusters also varies significantly, including substantial regional variation. The modal school cluster size is five to nine schools, but clusters range from as small as two schools to as many as 30 schools (Figure 3.1, Panel C). In the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, the average school cluster size consists of five to six schools, whereas in rural areas of central Portugal, school clusters are composed of, on average, more than ten schools (see Figure 3.1, Panel B).

Central authorities in Portugal define the legal standards for class size. In 2013, the maximal number of students per class was legally increased by 2 students per class in basic and general secondary education (typically from 24 to 26 students), and by 6 students per class in vocational courses (typically from 18 to 24 students) but the new government has prioritised class size reduction and plans to reduce the sizes to pre-2013 levels in 2018/19 (Ministry of Education, 2018[3]). However, as Chapter 4 discusses in detail, even after the changes to class size maximums, the actual class sizes in Portugal are around the OECD average of 21 and 23 in primary and secondary schools respectively.

A regular school day comprises of five to eight hours of classroom instruction, divided by some short breaks. School day extension is becoming more common in Portugal: an increasing number of students have lunch at school and spend additional time in extracurricular activities (Ministry of Education, 2018[3]). The majority of students (86% in 2015/16) enrol in the full-time school programme for the 1st cycle of basic education. The current government aims to extend this full-time school programme to other educational levels. In addition to standard academic programming, 797 of 809 school clusters and non-clustered schools offer school sports clubs (Desporto Escolar). Students remain at school after the standard school day free of charge and may participate in 36 different sports with over 7 000 teams across all municipalities. To date, however, no comprehensive evaluation of the impact of Desporto Escolar on students’ health or well‑being has been conducted.

Simultaneous to the extension of the school day for many students, 10% of schools still work in double shifts where some groups of students have classes only in the morning, while others attend only in the afternoon, especially in the densely populated suburbs of Lisbon (Ministry of Education, 2018[3]).

Figure 3.1. Variation in average school size and number of schools per cluster, 2015/16

Source of administrative boundaries: Direção-Geral do Território (2016), Official Administrative Maps of Portugal ‑ Version 2016 [Carta Administrativa Oficial de Portugal ‑ Versão 2016], http://www.dgterritorio.pt/cartografia_e_geodesia/cartografia/carta_administrativa_oficial_de_portugal_caop_/caop__download_/carta_administrativa_oficial_de_portugal___versao_2016/.

Sources: CNE (2017), Estado da Educação 2016 [State of Education 2016], Conselho Nacional de Educação, Lisbon, http://www.cnedu.pt/content/edicoes/estado_da_educacao/CNE-EE2016_web_final.pdf, Tables 2.1.1 and 2.2.2; DGEEC administrative data, 2015/16.

Private schooling

According to the Constitution of the Portuguese Republic and the Comprehensive Law on the Education System (see Chapter 1), the state has the duty to provide public education to all, as well as the duty to allow and to certify private initiatives in education. So, families have the right to attend private schooling, but at their own expense, unless there is no public offer where they live or their child has a specialised need not met in the local public schools.

Almost a third (30%) of Portuguese schools are private, either government-dependent and privately run, or private independent. The share of private schools has increased substantially in recent years for various reasons. The number of public schools was nearly halved from 10 443 in 2006/07 to 6 078 in 2015/16, whereas the number of private schools grew from 2 587 in 2006/07 to 2 708 in 2015/16.

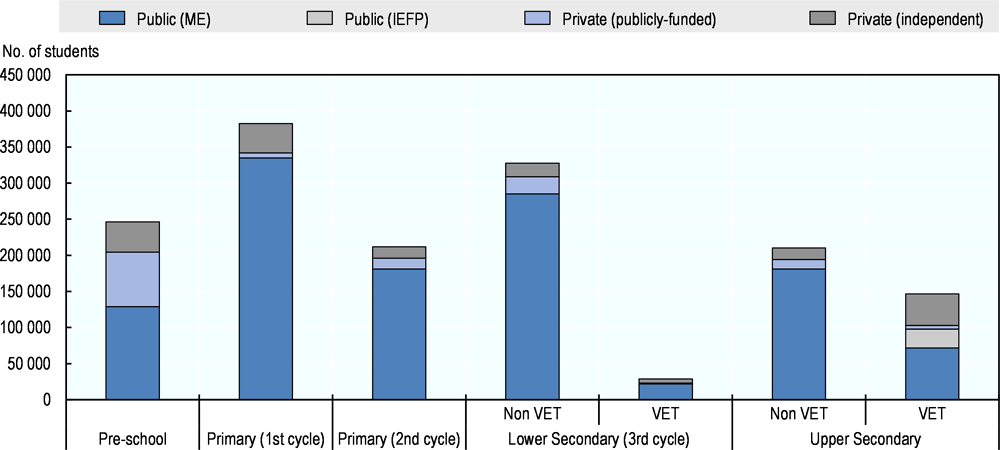

Private independent schools are self-financed through attendance fees, charged to students’ families. On the other hand, government-dependent private schools utilise a variety of contracted funding models with the government (see Chapter 2). Figure 3.2 presents total student enrolment numbers in public, government-dependent private and private independent schools by education level. Government-dependent private schools are most prevalent in the ECEC sector in institutions jointly financed and managed by the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Labour, Social Security and Solidarity (MTSSS). Private independent schools serve students in all levels but especially in VET programmes in upper secondary, as well as at the ECEC and 1st cycle primary educational levels. Annex A describes this distribution by the number of schools and highlights the dominance of private providers in the ECEC sector.

Figure 3.2. Student enrolment by type of provision and programme orientation, 2015/16

ME: Ministry of Education; IEFP: Institute for Employment and Vocational Training.

Source: Ministry of Education (2018), OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools: Country Background Report for Portugal, Ministry of Education, Lisbon, http://www.oecd.org/education/schoolresourcesreview.htm, Table 2.2.

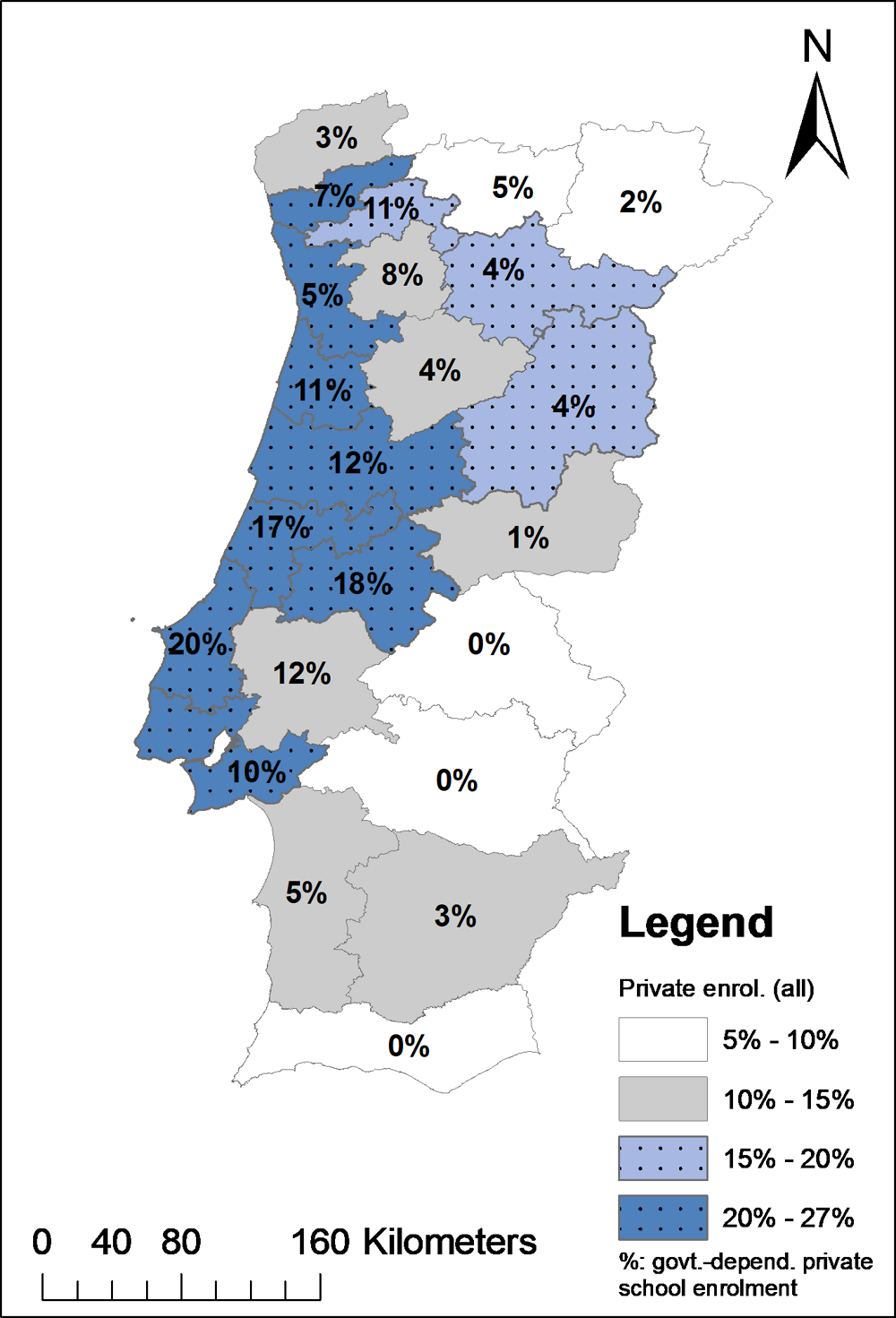

Government-dependent private schools are intended to fill gaps in the public supply of schooling in oversubscribed locales, remote locations, specialised artistic areas or special education. Figure 3.3 displays geographic patterns of enrolment in all private schools (shaded areas) and in government-dependent private schools (numbers). While some regions of Portugal have high rates of private school enrolment (up to one-quarter of all students), for the most part, the provision of private school places subsidised by the government exists only in areas where public school capacity is strained. Across the 278 Continental municipalities, there are only 21 municipalities in which the rate of government-dependent private school enrolment is over 10% and where fewer than 20% of schools at any educational level are over-capacity (defined here as having a total number of classes that exceed the number of available classrooms by 5% or more). In 8 of these 21 municipalities, no educational level has more than 20% of schools operating over capacity. Thus, with the exception of these few municipalities with no capacity issues but high government-dependent private enrolment, government-dependent private schools seem to be authorised, in line with stated priorities, to respond to the demand the public schools are unable to meet.

Figure 3.3. Private school enrolment

Note: The shaded regions on the figure display the proportion of students enrolled in all private schools in that region. The percentages inside the regions display the proportion of all students enrolled in government-dependent private schools. Government-dependent private schools are private schools with an association contract (contrato de associação), sponsorship contract (contrato de patrocínio) or any other type of agreement with local or central education authorities that provides public funding directly to schools. Schools enrolling students who receive direct financial assistance from the government that covers tuition fees in private schools are not considered government-dependent.

Source of administrative boundaries: Direção-Geral do Território (2016), Official Administrative Maps of Portugal ‑ Version 2016 [Carta Administrativa Oficial de Portugal ‑ Versão 2016], http://www.dgterritorio.pt/cartografia_e_geodesia/cartografia/carta_administrativa_oficial_de_portugal_caop_/caop__download_/carta_administrativa_oficial_de_portugal___versao_2016/.

Source: DGEEC administrative data, 2015/16.

Government-dependent private schools must obey the same set of criteria for the selection of students as those for public schools. Private independent schools have no specific regulatory constraints for the selection of students. They are free to set their own criteria as long as these do not violate non-discriminatory principles. As a consequence, private schools may give preference to children from specific backgrounds. Access to, or exclusion from, private independent schools is not subject to government inspection (Glenn and De Groof, 2002[4]).

The pedagogical and academic level of the curricula in government-dependent private schools must meet the national standards of general education policy. Independent private schools can follow the national curriculum or offer an alternative to be approved by the Inspectorate-General for Education and Science (Inspeção-Geral da Educação e Ciência – IGEC). In order to gain this approval from IGEC, schools must disclose the qualifications of their non-teaching staff, account for their educational philosophy by spelling out its educational orientation, explaining the principles by means of its “educational project” (projecto educativo) and show adequate physical facilities (Glenn and De Groof, 2002[4]). All private schools have the authority to determine what will be taught in at least 20% of the instructional time and choose textbooks and other materials without prior government approval. Private schools regulate their teachers' salaries in function of a pay scale which is based off the one used at public schools, though some divergence is possible (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). With respect to accountability, government-dependent private schools are subject to compulsory inspection of their teaching, learning and administrative processes by the Ministry of Education’s inspection services, though these take place outside of the regular external evaluation process. Inspection of private schools can include an evaluation of teaching methods, as long as the technical judgment is not of the ideological, philosophical or religious basis of the teaching (Glenn and De Groof, 2002, p. 422[4]).

School governance, performance evaluation and accountability

School governance

Due to the strong position of the central government in education and the relatively centralised decision-making, school-level governance in Portugal has traditionally been weak. It has long been characterised by limited school leadership skills and responsibilities. Teachers’ pedagogical approaches and curricular decisions tend to be dictated by central fiat (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]).

The nature of school-level governance changed in 2008 when the structure of schools and school clusters was recalibrated and professionalised; this provided more responsibilities to school cluster management and increased accountability. Today, a management team consisting of the principal and deputies manages each school cluster or non-clustered school. Most cluster principals now have some form of formal leadership training and ongoing professional leadership development courses are offered. Nonetheless, principals and other administrators continue to be conceived of within the profession as teachers on assignment, rather than professional managers (see Chapter 4). The management team shares its policy- and decision-making powers with and is assisted by a pedagogic council (Conselho Pedagógico), consisting of heads of subject departments and educational staff, and an administrative council (Conselho Administrativo), consisting of the principal, a deputy and financial staff. Chapter 4 explores leadership responsibilities and school management structures in more detail.

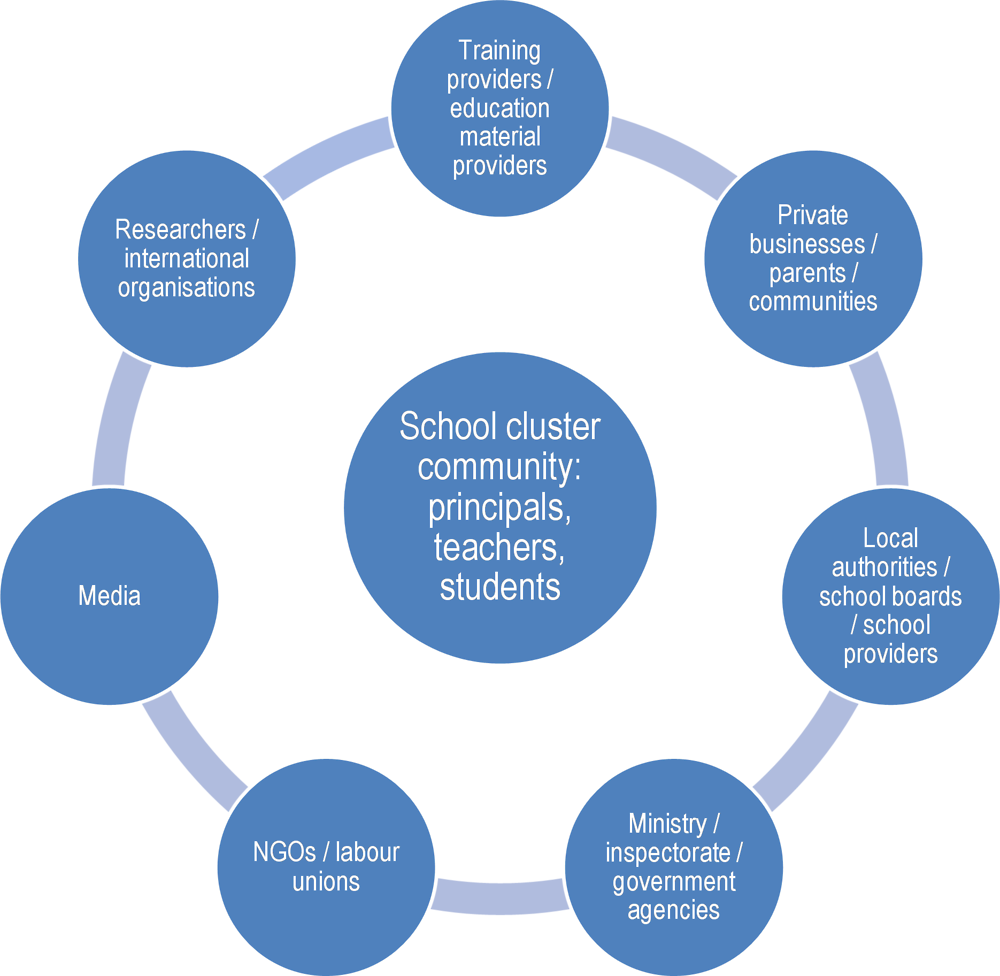

The formal governing body of each school cluster (and non-clustered school) is the General Council (Conselho Geral). The General Council is composed of teachers, non‑teaching staff, parents, secondary students, representatives from the municipality and representatives co-opted by the elected membership. The General Council selects the school cluster principal, approves the educational improvement plan for the school, and conducts the school’s internal evaluation Since the beginning of the process of democratisation, school autonomy has been framed in terms of participation and democracy at subcentral levels; a primary justification for the inclusion of teachers, students, parents and local stakeholders in school governance is this goal of democratic participation. The inclusive representation on the General Council is broader in Portugal than in many other democracies (Glenn and De Groof, 2002[4]).

Despite the original intent of a broad-based, representative local governance structure, due to lack of community participation and shifts in General Council membership, concerns have arisen about whether the General Councils continue to promote a governance structure that is fully accountable to all stakeholders and student interests. In the 1990s, the predominance of teachers in decision-making and the powers they were granted became a topic of contention. Debates ensued about the extent to which parents and members from local communities should participate in school governance (Eurydice, 2007, p. 11[5]). At the turn of the century, the vision of school autonomy gradually shifted from a political-administrative reform to a mechanism to improve the quality of education, emphasising the link between pedagogical and curricular autonomy and school success.

As it stands today, provisions for school autonomy in the governance of educationally important decisions are limited. The current pilot autonomy contracts (Pilot Project of Autonomy and Curriculum Flexibility) in Portugal allow for the carving out of time in school schedules during which modest amounts of the national curriculum (up to 25% of teaching time) may be tailored by the school to the specific needs and interests of its students. All schools will be eligible to participate starting in the 2018/19 school year. Additionally, starting in 2016/17, seven school clusters launched a separate Pedagogical Innovation Pilot Project (Projeto-Piloto de Inovação Pedagógico – PPIP) providing more complete curricular and scheduling autonomies with the goal of improving learning outcomes and reducing year repetition rates to zero. However, other types of school autonomy such as the autonomy to manage financial resources within the school cluster by means of a lump-sum budget instead of earmarked funding, or autonomy to manage human resources such as the freedom to select teachers, are not typically part of the policy discussions around school autonomy.

School accountability

According to international classifications of accountability in education, the current school accountability mechanisms can best be characterised as strong regulatory school accountability complemented with modest elements of school performance accountability (Hooge, 2016[6]). Strong regulatory school accountability enforces compliance with laws and regulations and focuses on inputs and processes within the school by means of reporting to the central government (Hooge, 2016[6]). It is a vertical accountability mechanism: top-down and hierarchical. The traditionally strong emphasis on the use of regulatory school accountability in Portugal corresponds with its highly centralised government and legalistic approach of educational policy- and decision-making.

Recently, Portugal has introduced some elements of school performance accountability on top of regulatory school accountability. School performance accountability mechanisms focus on outputs of schools such as efficiency and effectiveness, holding schools accountable for the use of resources in relation to the quality of education they provide (Hooge, 2016[6]). The new forms of school performance accountability introduced in Portuguese education are periodic school performance evaluations. By design, they were intended to involve a five-year evaluation cycle which would include a visit from an external inspection team examining: i) student performance data; ii) the quality of education service provision; and iii) leadership of the school. Coupled with the internal evaluation, schools were required to draft improvement plans based on the results of these external evaluations and a follow-up was planned to assess the extent to which the school was making progress towards these goals (Santiago et al., 2012[7]).

However, the 2nd cycle of external evaluations concluded in 2017 and at the time of the site review, no external evaluations were underway. Stakeholders reported that, during the 2017/18 school year, they were conducting internal evaluations but no external evaluations were taking place. Furthermore, at the time of the drafting of the report, no overall cycle report had been completed for the 2012-17 evaluation cycle. Finally, though a working group was meeting to discuss details of the 3rd evaluation cycle, no framework or schedule of evaluations had been created (IGEC, 2018[8]). Thus, for the 2017/18 school year, no external evaluations were to be conducted. In practice, therefore, Portugal’s form of performance accountability recently has been accomplished by means of common student assessments and by public reporting of school performance. While the public reporting of performance is a form of performance accountability, even on paper Portugal’s inspection and testing regime are relatively low-stakes compared to contexts in which poor performance can result in sanctions and high performance may result in additional autonomies or incentives.

Distribution of students to schools

In the 2015/16 school year, more than 1.5 million children and youngsters went to school in Portugal. The enrolment in pre-school education is above international averages (see Chapter 1). Particularly the share of 3-year-olds in ECEC has increased by 17 percentage points during the last decade, from a 63% enrolment rate in 2006/07 to 80% in 2015/16 (CNE, 2017, p. 81[2]). The enrolment in Portuguese basic education overall has been stable during the past decade. Almost all 15-year-olds (97%) are enrolled in the 3rd cycle of basic education, which is at the OECD average (OECD, 2017, p. 257[9]). As Chapter 1 highlights, total student enrolment has remained relatively stable over the past decade, reflecting countervailing trends of increased ECEC and upper secondary enrolment and declining basic education enrolment. Given that Portugal is approaching the upper bounds of enrolment rates and it is experiencing a long-term decline in its school-age population, it is expected to see a decline in overall enrolment in the coming years.

As discussed in Chapter 1, Portugal relies on geographic assignment to schools. While siblings’ enrolment is considered first, this, of course, is dictated by the initial enrolment of the oldest child. After special educational needs are considered, students’ legal residence is the next and most influential factor in school assignment. Thus, for parents enrolling their children in the public school system, the primary mechanism by which they can influence the school their child attends is through their choice of residence and to a lesser degree their choice of employment location. As a result of concerns about some families manipulating their residential or occupational address to access a more desirable school, for the 2018-19 academic year, the criteria have been changed to require students to use their legal address, defined via the tax declaration process, for their public school application. Additionally, as noted in Chapter 1, new for the 2018-19 academic year, students receiving social support will have preferential status after the above factors are applied in an attempt to increase opportunities for low-income students and increase socio-economic integration in schools.

Parents’ choices of residence, and by extension schools, are heavily influenced by public reporting on school quality. The yearly coverage by the media of school rankings based on average scores in national tests during the past decade and a half has generated competition between schools and led to socio-economic- and achievement-based segregation between schools (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). Until recently, the school rankings published in Portugal did not take students’ demographic characteristics into account. Currently, the Directorate-General for Education and Science Statistics (Direção-Geral de Estatísticas da Educação e Ciência – DGEEC) publishes performance ratings of schools that consider the demographic characteristics of their student bodies following recommendations from the OECD Review of Evaluation and Assessment in Education (2012[7]). The DGEEC also publishes indicators of school performance online in the Schools Portal (InfoEscolas) and the IGEC external evaluation reports of all public schools are available on the internet. However, the most intensive media attention remains on the raw rankings based solely on test scores published in leading newspapers.

The results of a recent study show that the reporting of school rankings in Portugal has had significant effects on families’ choices. Specifically, an improvement of 10 ranking places for the average school is associated with an increase of about 0.4 percentage points in the number of enrolled students. Additionally, lower performing schools, particularly private ones, are more likely to close since the public release of rankings (Nunes, Reis and Seabra, 2016[10]).

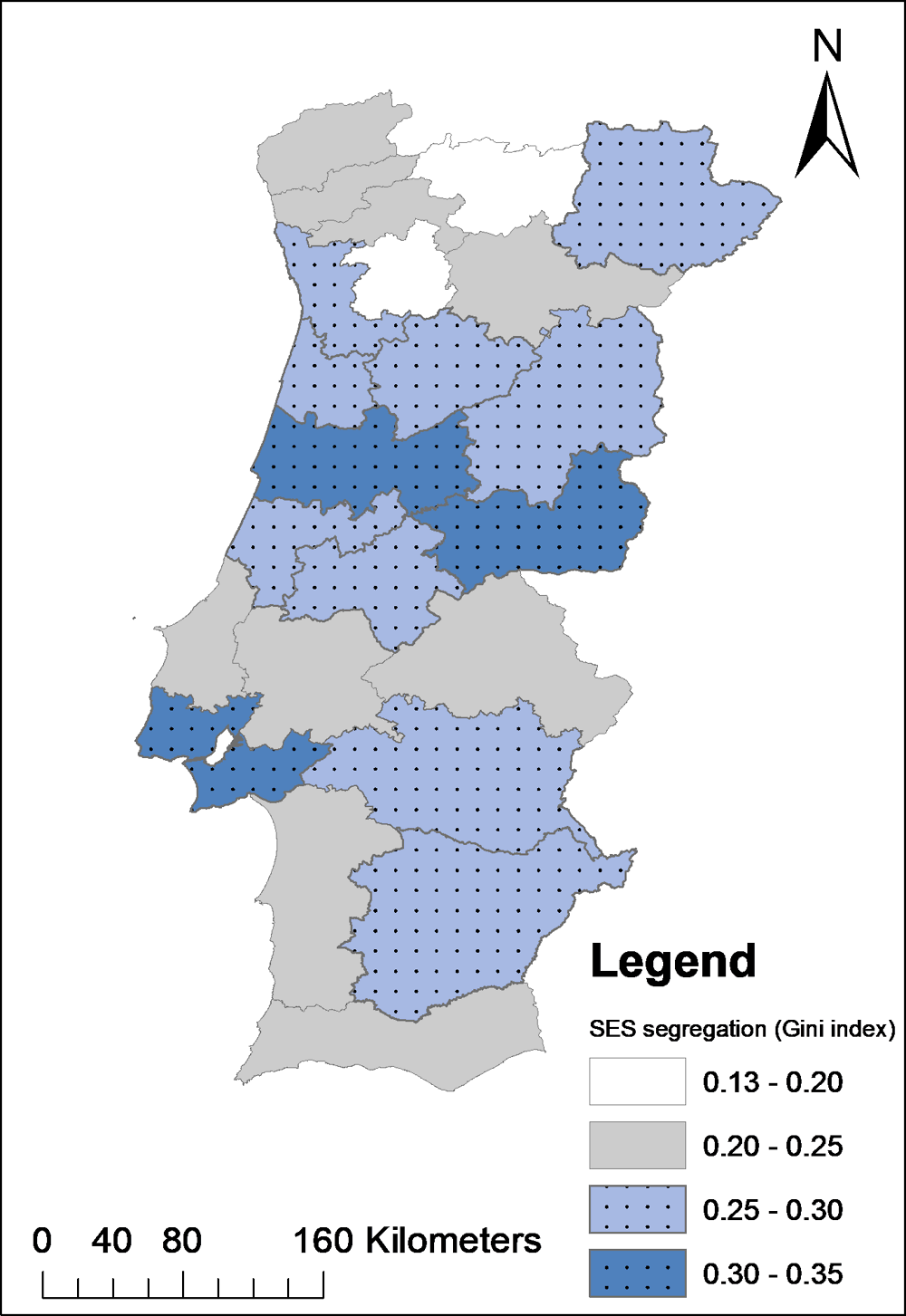

Residential segregation, geographic assignment and public rankings all contribute to the fact that the level of between-school socio-economic segregation in the Portuguese education system is substantial. Figure 3.4 and Figure 3.5 display the unevenness in the distribution of students across schools across regions in the country. Figure 3.4 reveals the high degree of between-school segregation, in which children receiving School Social Assistance (Ação Social Escolar – ASE) and who have low levels of maternal education are concentrated in particular schools. In half of continental Portugal’s NUTS III regions, including the most populated areas of Lisbon and Porto, the Gini index measuring between-school socio-economic variation is above 0.25. This is higher than the findings in a recent study that found between-school socio-economic variation in the 100 largest United States metropolitan areas registered a Gini index of 0.23 (Owens, Reardon and Jencks, 2016[11]). These findings accord with a recent DGEEC report finding high rates of socio-economic segregation within 2nd cycle schools. In particular, the report found a startling difference in the school enrolling the highest percentage of students receiving School Social Assistance (78%) in the Lisbon municipality and the school enrolling the lowest percentage (8%). Even more startling, in the 2nd cycle Lisbon school with the lowest levels of maternal education, 91% of students had mothers who had not completed secondary education. Conversely, in the school with the highest level of maternal education, only 2% of students had mothers who had not completed secondary education (Oliveira Baptista, Pereira and DGEEC, 2018[12]). Similar variation held in the Porto municipality as well.

Figure 3.4. Level of student segregation across schools by socio-economic status (Gini coefficient)

Note: Index of socio-economic need measured by rank percentile-ordering the proportion of students within a school receiving School Social Assistance A and average years of maternal education at the school level. The average of the 2 ranks was then demeaned (mean = 0) and assigned a standard deviation of 1. High values of the index indicate high levels of socio-economic challenge. A within-NUTS III region Gini index was calculated based on the standardised value of school-level disadvantage. The Gini coefficient ranges from 0 to 1, where 1 represents perfect inequality and 0 represents perfect inequality between subunits.

Source of administrative boundaries: Direção-Geral do Território (2016), Official Administrative Maps of Portugal ‑ Version 2016 [Carta Administrativa Oficial de Portugal ‑ Versão 2016], http://www.dgterritorio.pt/cartografia_e_geodesia/cartografia/carta_administrativa_oficial_de_portugal_caop_/caop__download_/carta_administrativa_oficial_de_portugal___versao_2016/.

Source: DGEEC administrative data, 2015/16.

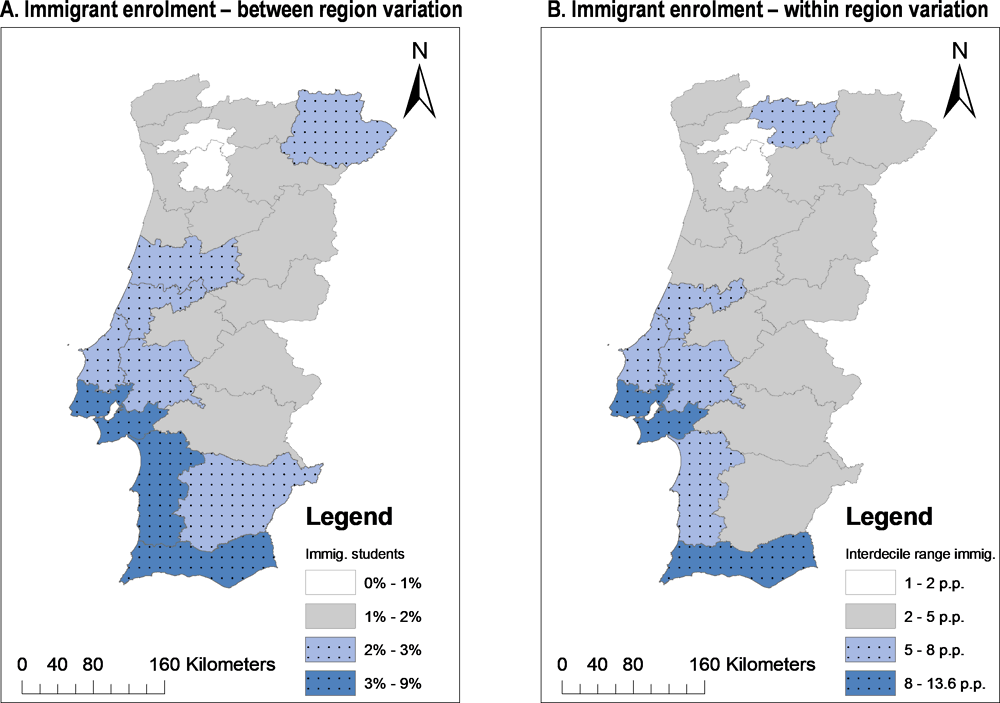

Similarly, while the overall proportion of immigrants in Portugal tends to be low, immigrant students are more common in some regions and are concentrated in a small number of schools. Immigrant student enrolment is highest in Lisbon and southern Portugal, whereas there are relatively few immigrant students in eastern Alentejo, the Centre and the North. More striking is the range of immigrant enrolment across schools in those areas that do have more immigrant students. Schools in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (AML) that enrol more immigrant students than 90% of all other AML schools are 15.1% immigrant. On the other hand, schools that enrol fewer immigrant students than 90% of all other AML schools are only 1.5% immigrant (Figure 3.5). Thus, it is evident that for a small but not marginal proportion of schools, meeting the needs of immigrant students is a central concern.

Figure 3.5. Immigrant student distribution

Note: The proportion of immigrant students is the weighted average of the proportion of the immigrant enrolment rate for all schools within a region. The interdecile range is the difference between the immigrant enrolment rate for schools in the 90th percentile for immigrant enrolment within the region and the immigrant enrolment rate for schools in the 10th percentile. For example, in the Metropolitan Area of Lisbon (AML), schools in the 90th percentile for immigrant enrolment have immigrant enrolment rates of 15.1%. Schools in the 10th percentile have immigrant enrolment rates of 1.5%. Thus, the interdecile range for immigrant enrolment in AML is 13.6 percentage points.

Source of administrative boundaries: Direção-Geral do Território (2016), Official Administrative Maps of Portugal ‑ Version 2016 [Carta Administrativa Oficial de Portugal ‑ Versão 2016], http://www.dgterritorio.pt/cartografia_e_geodesia/cartografia/carta_administrativa_oficial_de_portugal_caop_/caop__download_/carta_administrativa_oficial_de_portugal___versao_2016/.

Source: DGEEC administrative data, 2015/16.

The levels of between-school segregation evidenced by the school-system wide census data are borne out by PISA samples of 15-year-old students. Within the OECD, Portugal has the 5th highest rate of between-school socio-economic variation, trailing only Turkey, Spain, Chile and Mexico (Table I.6.10 in OECD (2016[13])). An important caveat is that Portugal also has some of the largest overall variations in students’ socio-economic status within the OECD which drives a large proportion of the level of between-school segregation (Figure II.5.12 in OECD (2016[14])).

Between-school segregation is also related to between-school performance variation. As noted in Chapter 1, student performance in Portugal is strongly correlated with the environment in which children grow up and the composition of the student population of each school is also closely related to average learning outcomes on national assessments. PISA data reveal in more detail how between-school segregation relates to between-school performance variation. There is a moderately strong, positively signed correlation between school systems that have higher rates of social inclusion across schools and school systems that have higher rates of performance inclusion across schools (Figure II.5.12 in OECD (2016[14]).

In addition to evidence suggestive of high degrees of public school segregation, there are also patterns of socio-economic segregation between public and private schools. Among schools enrolling 15-year-old students, schools in the top quartile of socio-economic status are 13 percentage points less likely to be public schools than those in the bottom quartile of socio-economic status (Table II.4.10 in OECD (2016[14])). Further, when examining census data of all Portuguese Year 6 students, Brás de Oliveira (2018[15]) found that 1.3% of students at private independent schools receive social support, while 45.4% in government-dependent private ones receive social support and 53.6% in public schools. Thus, there are clear socio-economic differences between students in private and public schools, and this is particularly true for private independent schools (Brás de Oliveira, 2018[15]).

With respect to the level of within-school segregation, Table 3.1 shows that in Portugal, tracking at the age of 15 is in line with most OECD countries. Year repetition in Portugal is almost 3 times higher than the OECD average (31.2% compared to 11.3%). Official ability grouping is much lower than the OECD average (4.3% compared to 7.8%) (Table II.5.22 in OECD (2016[14]). However, no system-wide regulations exist governing how class groups are formed that would prohibit class-level sorting on the basis of prior academic achievement. As a result, important concerns exist about these informal mechanisms of within-school sorting (see below).

Table 3.1. Grouping and student selection

|

|

Portugal |

OECD average |

|---|---|---|

|

Tracking (Age of selection into different education types or programmes) |

15 |

14.3 |

|

Year repetition (Percentage of students who have repeated a year at least once in primary, lower secondary or upper secondary school) |

31.2 |

11.3 |

|

Ability grouping (Percentage of students in schools where students are grouped by ability into different classes for all subjects) |

4.3 |

7.8 |

Source: OECD (2016), PISA 2015 Results (Volume II): Policies and Practices for Successful Schools, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en, p. 178.

Contributing to the relatively high levels of segregation, the Portuguese education system offers multiple curricular pathways for students with special profiles, starting in the first cycle of basic education. Besides the general path, attended by most students in basic education, about 8% of the total number of enrolled students complete the Year 9 under alternative offerings (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). In particular, the provision of Alternative Curricular Pathways (percursos curriculares alternativos – PCA) is targeted to students in the 2nd and 3rd cycles of education who are overage, have learning difficulties and are at-risk of year repetition or dropping out. This type of offer is intended to be temporary in nature and aims to motivate students to re-gain interest in school. There are also programmes that target highly mobile students. A programme for Distance Learning for Itinerant Students (Ensino a Distância para a Itinerância) seeks to ensure basic school education to students that, due to their parents’ occupation or lifestyle, are forced to change schools frequently, particularly targeting students from Roma communities. Regular education primary and secondary programmes also offer Portuguese as a Second Language (Português Lingua Não Materna – PLNM) for students who need Portuguese language instruction. Students are initially orally screened and families complete a home language survey. Students then sit for a placement test if necessary to determine Portuguese proficiency levels. Students in vocational programmes do not have access to PLNM courses in all schools. Finally, home-schooling (ensino doméstico) is permitted, as long as it is under the responsibility of a qualified adult and the supervision of a school (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]).

For adults, several second-chance education programmes are available, depending on their needs and previous educational experiences, whose provision is under the umbrella of the recently created Qualifica programme (see Chapter 1, Box 1.2).

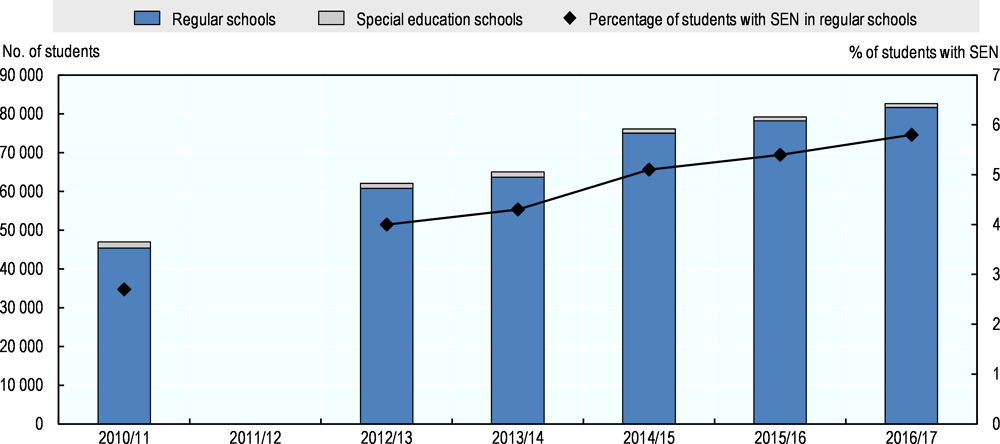

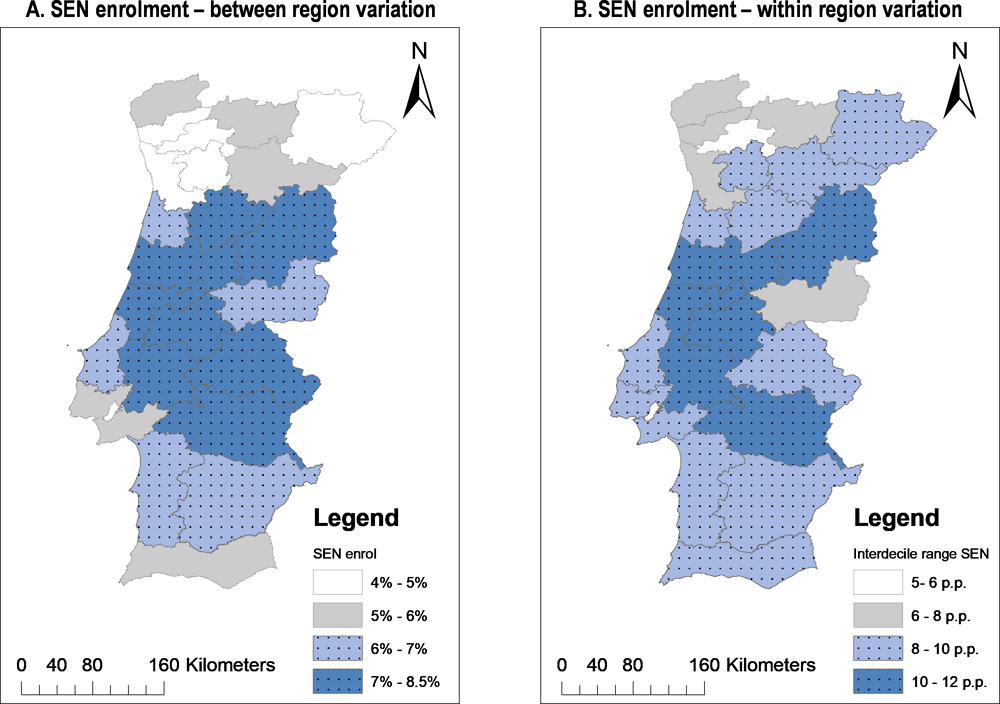

Adapted provision for students with SEN

School education in Portugal recognises the special educational needs (SEN) of some students. The law for inclusion (Decree-Law 3/2008), at the time of writing of this report, does not explicitly define special educational needs nor formally set criteria for identification of SEN, rather leaving to the discretion of specialised personnel operating according to international standards. Differentiated provision for SEN students translates into the adaptation or modification of curricula, and potentially the assignment of a student to a different learning environment. Education of students identified as SEN is almost exclusively provided in mainstream schools – 98.8% of SEN students were integrated into such settings as of 2016 – with special education schools being now almost entirely restricted to fulfil a role of resource centres for inclusion (see Chapter 2 and below). Students may only attend special education institutions, a total of 50 of which exist nationwide, under approval from the Ministry of Education and when learning limitations are sufficiently severe to require education in a separate school (EASNIE, forthcoming, p. 23[16]). The identification and enrolment of students with special education in regular schools have significantly increased in recent years, alongside a continuous decrease of enrolment in special education schools (Figure 3.6). Mainstream-school educated students with SEN grew by 76% between 2010 and 2017. In total, 5.8% of all students are identified as SEN, most of whom attend basic education (7.7% of all students in Years 1-9) (Ministry of Education, 2018, p. 88[1]).

Specialised support to students with SEN within schools is complemented by a network of 93 specialised resources centres for inclusion (centros de recursos para a inclusão – CRI) and 25 information and communication technology (ICT) resource centres for special education spread across the country. About 581 school clusters (72% of the public school network) receive support from CRIs. CRIs deploy a total of 2 251 technicians, such as occupational therapists, speech therapists, physiotherapists or psychologists, and 1 141 technicians work directly in schools (DGEEC, 2017[17]). Additional resources have recently been targeted to the support of students with SEN. In 2016/17, an additional 221 full-time psychologists were allocated to schools, with a commitment to contract an additional 200 psychologists in 2018 in order to improve the student-psychologist ratio to 1 140-to-1. The resource centres are designed to support the inclusion of children with disabilities, build partnerships with local actors and facilitate the access of students with SEN to different activities. The network of support is further complemented by the identification of schools specialised in teaching students with given disabilities. Finally, students with severe needs rely on two types of structured teaching units: one for the education of students with autism spectrum disorders and another for the education of children with multiple disabilities and congenital deaf-blindness (Ministry of Education, 2018[3]) where students are educated in largely separate classrooms, even if in a mainstream school building. Together, these types of specialised teaching units supported 5% of SEN students, as of 2016/17.

Figure 3.6. Change in the number and proportion of students with SEN by type of school, 2010-17

Source: DGEEC (2017), Necessidades Especiais de Educação [Special Educational Needs], http://www.dgeec.mec.pt/np4/224/.

Since 2017, and while this report was being prepared, there has been public discussion of a new law on the inclusion of students with special educational needs. The reform aims to clarify the roles of the different actors involved in the identification of SEN students. In particular, the new law aims to make a medical evaluation an optional, rather than mandatory, procedure to identify a student as having SEN and trigger the development of an Individualised Education Plan (Planos Educativos Individuais – PEI). The intent of this reform is to recognise special educational needs as learning obstacles, rather than medical conditions.

Vocational education and training

Vocational Education and Training (VET) plays an important role in upper secondary education in Portugal. When entering upper secondary education, typically at 15 years of age, students choose between different tracks and fields of study (see Chapter 1). Just as several strands are available in the general track, initial VET is separated into five strands. For the purpose of this report, initial VET courses refer to a vocational offer that is targeted at young students – typically until 24 years of age – and at the upper secondary level of education. Table 3.2 provides the main features for each of these programmes.

Table 3.2. Characteristics of initial VET programmes

|

Type of programme |

Theoretical duration of studies (in years) |

Number of learning hours |

Work-based learning (%) |

Fields of study |

Target age (years-old) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Professional programmes |

3 |

3 200 |

19-24 |

40 |

15-18 |

|

Apprenticeship programmes |

2.5 |

2 800-3 700 |

40 |

.. |

15-24 |

|

Specialised artistic |

3 |

.. |

[in the 3rd year] |

.. |

15-18 |

|

CEF courses |

1-2 |

1 125-2 276 |

.. |

.. |

15-18 |

|

Vocational courses |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

15-18 |

.. : Information not available.

Source: DGERT (2016), Vocational Education and Training in Europe ‑ Portugal, http://libserver.cedefop.europa.eu/vetelib/2016/2016_CR_PT.pdf.

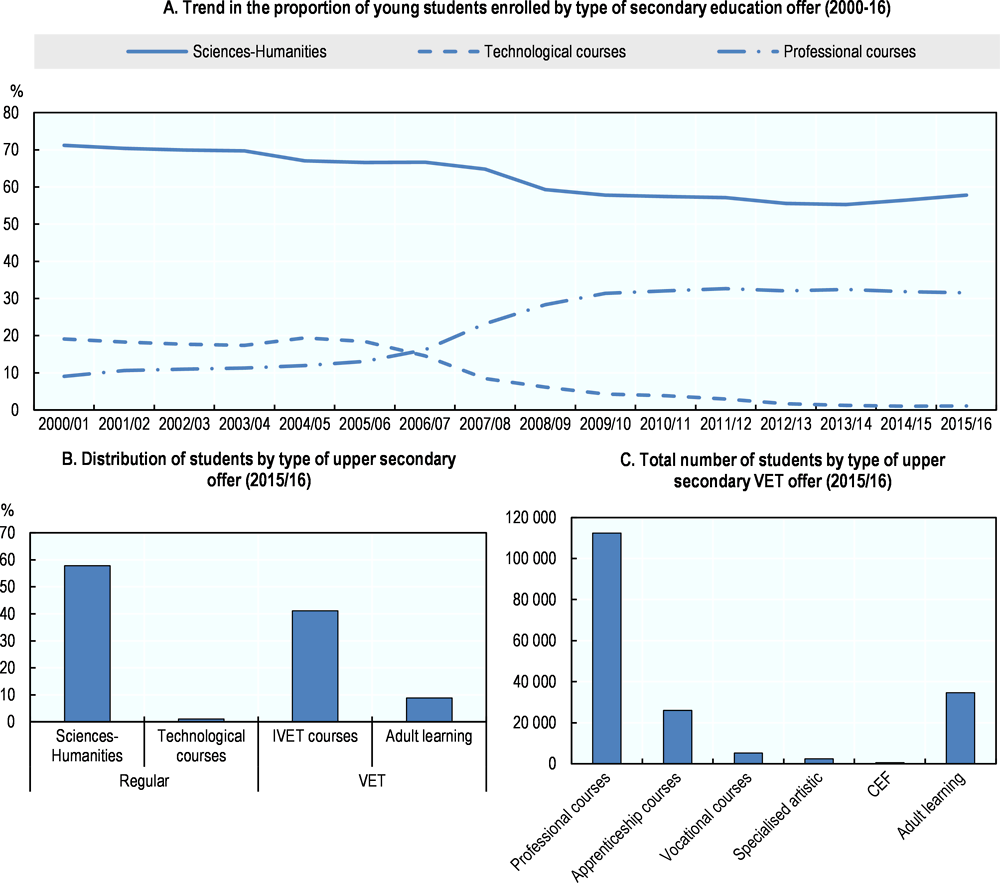

Each type of VET programme combines specific learning components. The development of general skills is built into socio-cultural or scientific components, which correspond to learning that occurs in the classroom context at school. On the other hand, technical, technological or practical components are typically learned on the job or in a simulated working environment. As Table 3.2 displays, each programme has different dosages of work-based learning, often dependent on the field of study. The fields of study vary considerably. Professional courses, the most popular among VET students (Figure 3.7, Panel C), offer as divergent study options as computer sciences, electronics, engineering, tourism, business administration, construction or applied arts, among forty different possibilities. In turn, apprenticeship programmes focus on priority areas of training such as computer sciences, construction and repair of motor vehicles or manufacture of textiles, among others. As in most other OECD countries, completion of any of the VET offerings leads to a double certificate allowing students to pursue further studies in post-secondary education. However, access to tertiary academic education is subject to the same entrance requirements as for upper secondary students from the general track (DGERT, 2016, pp. 17-19[18]).

Upper secondary VET is currently offered through different networks of provision. Building on the strategic orientation to improve the status of VET and the extension of compulsory education, Ministry of Education schools have recently expanded their offering of VET courses. As of the 2015/16 school year, 453 schools offered VET. On the other hand, a network of public, private independent and publicly-funded professional schools (escolas profissionais) also provides upper secondary and post-secondary education VET. There were 224 professional schools offering upper secondary VET, only 16 of which were strictly public. Finally, 33 professional training public centres managed by the Institute for Employment and Vocational Training (IEFP), as well as other private providers certified by the institute, offer apprenticeship programmes, in which over 26 000 students are enrolled annually.

Figure 3.7. Trends and distribution of the provision of VET programmes

Note: Panel A depicts the trend in the number of young students in each of the tracks as a proportion of the total enrolment of young students in upper-secondary education. In Panels A and B, the proportion of students in the regular track includes those enrolled in technological courses, a type of vocationally-oriented offer that is included in the regular track and has been progressively discontinued (see Chapter 1). In Panel B, IVET refers to initial vocational education and training, i.e. VET offer targeted at young students. IVET offer includes professional, apprenticeship, specialised artistic, vocational and education and training courses (cursos de educação e formação – CEF). In Panel C, enrolment in adult learning courses include individuals in recurrent upper secondary classes (ensino recorrente), education and training courses for adults (Educação e Formação de Adultos – EFA), certified modular training (Formaçãos Modulares Certificadas – FMC) and in the national system of prior learning assessment and recognition (Sistema Nacional de Reconhecimento, Validação e Certificação de Competências – RVCC).

Source: DGEEC (2016), Estatísticas da Educação 2015/2016 [Education Statistics 2015/16], http://www.dgeec.mec.pt/np4/96/%7B$clientServletPath%7D/?newsId=145&fileName=DGEEC_DSEE_2017_EE201520164.pdf.

Current government leaders are eager to improve the status of VET as an alternative track to general education. The current government has stated the goal of reaching a 50‑50 distribution of upper secondary students across general and vocational programmes by 2020. But the historical reputation of vocational education in the country is weak. After a backlash against the development of a “technical education” sector following the democratisation process started in 1974, it was not until 1989 when publicly regulated professional schools offering VET were created. The opening of professional schools occurred alongside the emergence of professional courses offered in IEFP training centres, mainly created to address local employment needs. The integration of VET courses in the mainstream education system only occurred in 2006, with the development of an alternative vocational track in upper secondary public schools (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). Since then, the share of young upper secondary students enrolled in initial VET programmes has been steadily increasing, reaching about 41% in 2015/16 (Figure 3.7, Panel B). The surge has been followed by a decrease in the provision of technological courses, offered alongside sciences-humanities programmes in the general track. Technological courses, despite being vocationally-oriented, do not offer any work-based learning and have been essentially discontinued, enrolling only about 1% of upper secondary youth (Figure 3.7, Panel A).

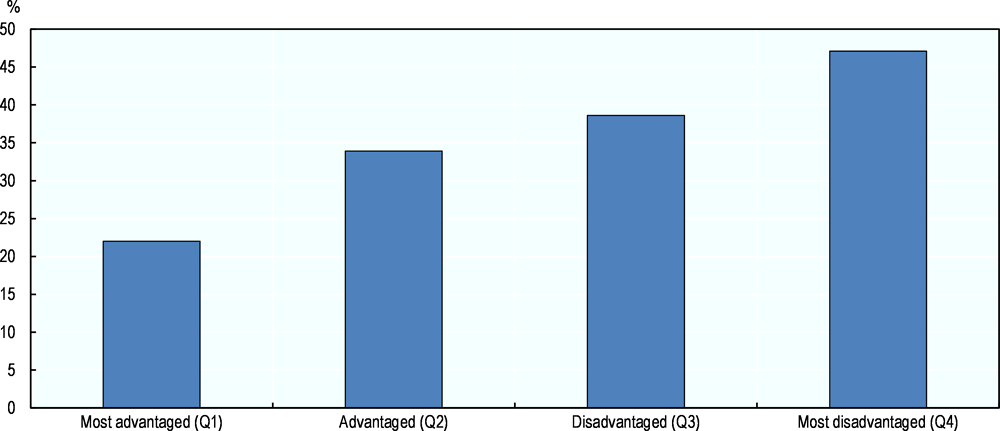

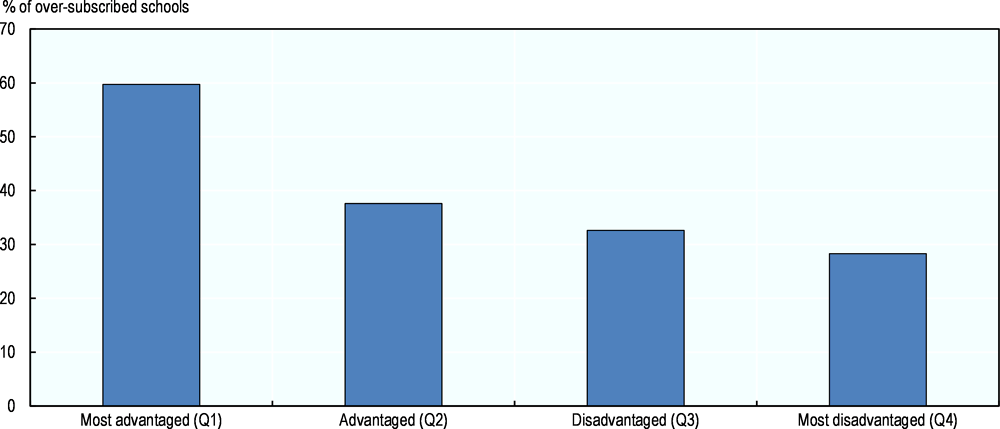

As in most OECD countries, enrolment in VET programming is tied to students’ socio-economic status. Upper secondary schools with higher proportions of socio-economically disadvantaged students concomitantly have higher proportions of students enrolled in VET programmes. In fact, as Figure 3.8 shows, in schools that enrol the most students receiving social support and with the lowest levels of maternal education, an average of 47% of students enrol in VET programmes. On the other hand, in the most advantaged schools, only 22% of students study in VET courses. A key policy consideration is whether the greater concentration of VET students in schools with higher levels of socio-economic need is an attempt to design curriculum that better engages this group of students and helps them progress towards secondary school completion, or whether the differences reflect a lowering of expectations and a circumscription of educational and professional opportunities for students from low socio-economic status backgrounds (OECD, 2018[19]).

The strategic priority to develop the vocational education and training system in Portugal has been extended to lower secondary education. CEF courses are offered to students who have not yet reached upper secondary education, targeting those at risk of early school leaving at the 2nd or 3rd cycles of basic education. In 2013, pre-vocational programmes (cursos vocacionais no ensino básico) were introduced for students 13 or older, who have repeated at least twice in the same cycle or three times overall. Classes were organised into modules and teaching was intended to have a strong involvement of private companies from communities surrounding the school. The expansion of this type of offer was limited to schools with technical and pedagogical capacity and did not have full national coverage. However, this type of offer did not gather political support due to concerns with the effectiveness and equity of tracking students earlier and has been discontinued since 2016. Offerings in CEF courses for students 15 or older are still an option available to schools to tackle early school leaving (DGERT, 2016[20]; Ministry of Education, 2018[3]).

Figure 3.8. Proportion of upper-secondary students enrolled in VET programme by level of school disadvantage

Note: The figure shows the distribution of the proportion of VET students by quartile of an index of socio-economic disadvantage. Index of socio-economic disadvantage is measured by rank percentile-ordering the proportion of students within a school receiving School Social Assistance A (ASE A) and average years of maternal education at the school level. The average of the 2 ranks was then demeaned (mean = 0) and assigned a standard deviation of 1. High values of the index indicate high levels of socio-economic challenge.

Source: DGEEC administrative data, 2015/16.

Planning of the VET network is centrally steered and monitored by ANQEP (Agência Nacional para a Qualificação e o Ensino Profissional), an inter-ministerial public agency (see Chapter 1, Annex B). The recently created System for Anticipation of Qualification Needs (Sistema de Antecipação de Necessidades de Qualificações – SANQ) is the cornerstone of the process of strategic decision-making with regards to VET. Together with the broader architecture of the National System of Qualifications (SNQ), which extends to adult learning (see Box 3.1), the SANQ plays an important role in closing the gap between VET courses on offer and labour market needs. SANQ aims at increasing both vertical co-ordination of VET and promoting horizontal co-operation among relevant actors at subnational levels (in this case, the 23 inter-municipal communities, CIMs - Comunidades Intermunicipais). SANQ has three main strategic priorities: i) a diagnosis of past and forecasted labour market dynamics; ii) a planning module aimed at building a ranking of qualification priorities; and iii) a regional co‑ordination module. The planning module includes the characterisation of the VET offer profile, relating the current number of enrolled students by type of offer and qualification priorities. The ranking of priorities is defined by ANQEP based on the assessment of labour market needs, in the first stage. The regional co-ordination module combines the two first priorities at the regional level: inter-municipal communities are asked to adjust centrally-defined priorities according to SANQ’s methodology, with priority given to local stakeholders’ perspectives. The CIMs that decide to not participate in this phase of the process abide the prioritisation established at the central level. After updating the priorities according to CIM feedback, ANQEP has the legal power to define and regulate the minimum and maximum number of classes to open in each CIM. According to ministry officials, currently the criteria are only being applied to providers under the Ministry of Education supervision.

Box 3.1. National System of Qualifications (SNQ)

Overview of main instruments

The National Qualification Framework (NQF) defines a hierarchical structure of qualification levels aligned with the European Qualifications Framework (EQF).

The National Qualifications Catalogue (Cátalogo Nacional de Qualificações – CNQ) is a catalogue of non-tertiary qualifications under the purview of the National Agency for Qualifications and Professional Training (Agência Nacional para a Qualificação e o Ensino Profissional – ANQEP). For each qualification, the CNQ identifies relevant skills, which are broken down as “skill units” (unidades de competência) as well as relevant training units of short duration (unidades de formação de curta duração – UFCD). The catalogue is regularly updated and managed through the collaboration of 16 different Sector Councils for Qualification co-ordinated by ANQEP. Each sector council integrates several stakeholders, such as employers, trade unions, schools and VET providers, technology and innovation centres, sector regulators, professional associations and invited experts. The participants in each sectorial council, as well as other entities registered in SNQ, can at any time propose the integration of new qualifications or the deletion of existing ones, through an online tool – the Open Model of Consultation.

The National Credit System for VET seeks to exploit the modular structure of the CNQ to implement flexible training paths. Every skill unit or UFCD corresponds to certain credits, enabling users to easily capitalise on prior skills acquisition when pursuing new qualifications. It is used only in double-certification training courses.

The Integrated System of Information and Management of Education and Training Supply (‘SIGO’) is a platform created for registering training activities of individual students with providers in the SNQ, whether their qualifications are part of the CNQ or not. Upon conclusion of any training activity, a certificate is issued by SIGO.

Source: OECD (2018), Skills Strategy Implementation Guidance for Portugal: Strengthening the Adult-Learning System, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264298705-en.

Strengths

Clear governmental priorities and targets with respect to expanding access to schooling

The current and previous Portuguese governments have set very clear education policy priorities and targets which have pinpointed precisely how and for whom school places are needed across the education system. These include:

Universal expansion of upper secondary access in 2008-09, followed by increases in graduation rates to 90% by 2020.

Universal access to early childhood education and care (ECEC) for 3-5 year‑olds by 2019.

90% participation in extended school day (full-time schooling).

Increase in enrolment in VET programmes to 50% by 2020.

Involvement of 600 000 adults in education by 2020.

These priorities will provide education access at nearly universal levels. The realisation of these priorities and targets require sufficient solid physical infrastructure, appropriate network planning and recruitment of a new wave of teachers (see below and Chapter 4). Importantly, when these priorities are realised, it will create additional pressure to ensure the quality provision of the expanded educational offer.

Articulated priorities for decentralisation in education

In spite of its highly centralised governance of the educational system, there has been broad political and societal support for decentralisation in Portugal since the democratic revolution of 1974, favouring the development of civil society and participation at the local level. The primary priorities the ministry and government currently articulate for decentralisation in education relate to the construction and maintenance of school buildings, the hiring and employment of non-teaching staff, and peri-educational activities such as full-day enrichment activities, sports, etc.

The inter-administrative contracts between central and local governments (see above) seem flexible enough to explore different approaches to decentralisation and to conduct experiments. The review team observed promising policies and practices at the municipality level, such as the development of local targeted educational projects, the promotion and fostering of education networks across teachers, school leaders, parents and families, educational stakeholders and private partners and the involvement of private entities in training school administrators, ad hoc management consulting, school visits to companies and timely traineeship opportunities for students and engagement in the design of VET and general schooling offerings.

Despite clearly articulated priorities around decentralisation in education, the political leadership of the ministry is clear that the following core three areas are not under consideration for local control: hiring and placement of instructional staff; curriculum; and the organisation of the school network.

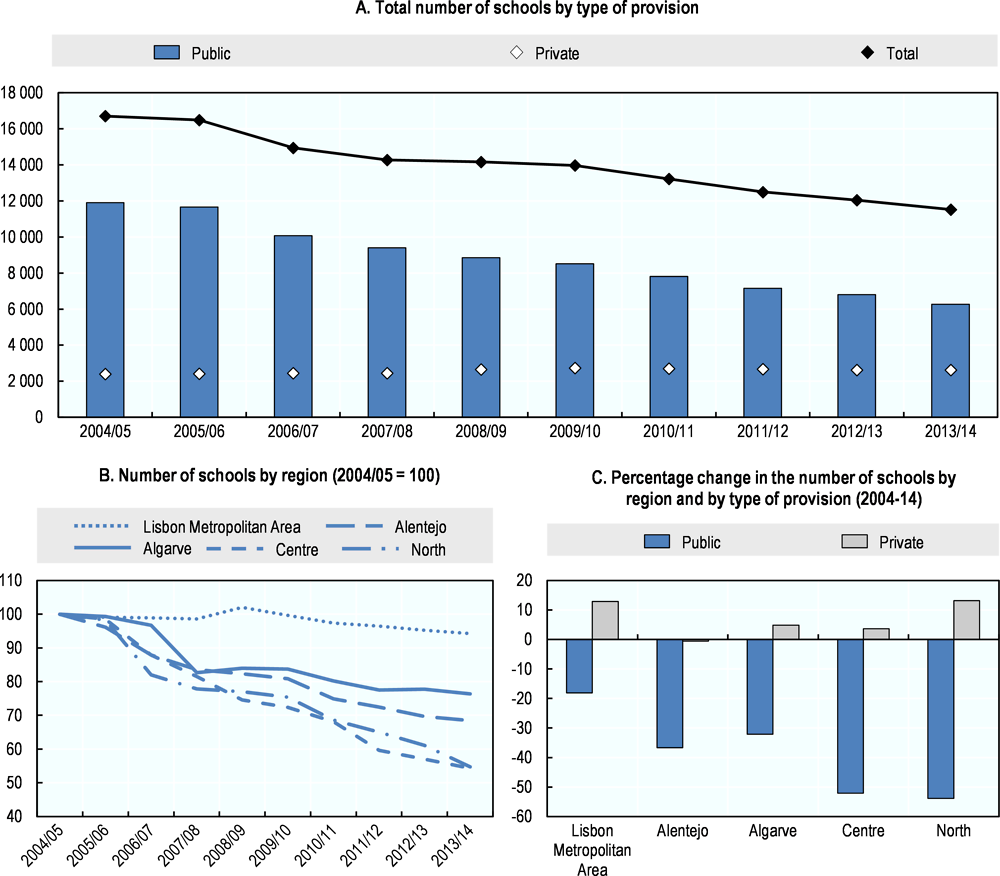

There is an ambitious and overarching strategy to respond to declining student populations

The Portuguese education system has witnessed a major process of consolidation in the past decade, leading to a considerable reduction of educational institutions in the public school network. Between 2004 and 2014, Portuguese educational authorities shuttered more than 47% of public education institutions – a total of 5 600 schools (Figure 3.9, Panel A), compared to a decline of about 15% of students enrolled in primary education during the same period (Figure 1.7, Panel A). In 2006, a new policy let municipalities recalibrate the 1st cycle school network and thousands of small schools were closed. Prior to the reform, the school network was dominated by small primary schools with poor facilities and low performance – particularly in rural areas (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). As Panel B of Figure 3.9 shows, while the school network in the densely populated Lisbon Metropolitan Area shrunk by only 6%, the consolidation process meant the closure of almost half the schools in the rural North (45%) and Centre (46%) regions.

Central authorities have recently been employing additional efforts to also reduce the number of government-dependent private schools. Contrary to the tendency in the public school network, the number of private schools increased in all regions but Alentejo. In the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, for every 10 public schools that were closed, a net average of 7 new private providers entered the school network (Figure 3.9, Panel C). While there are no strict regulations to discourage the growth in independent private provision, such increase in the face of declining student populations can lead to greater misallocations of school resources, double offering and greater pressure to keep consolidating the public network (see Challenges section). In order to curtail double provision of school places, the current government has further tightened the criteria for the public funding of private providers, de-funding classes in areas with available public offer, thus signalling the intention to keep rationalising the overall offer. Availability of centrally collected data allowed the decision to be based on a study of available infrastructure capacity and travelling distances to the closest public schools, effectively reducing duplicate offer (DGEEC, 2016[21]). These approaches align with the OECD recommendations in the Responsive School Systems: Connecting Facilities, Sectors and Programmes for Student Success report (OECD, 2018[19]) to tie the licensing of government-dependent private providers to the local need for additional school places as an effective means to enhance the efficiency of school networks, particularly in areas characterised by lack of available places in public schools.

Consolidation can be a disruptive experience for students and families having to relocate to a new school, often further removed from their home. The experience of OECD review countries has demonstrated the importance of public authorities and schools working together to make this transition as smooth as possible. Careful planning can ameliorate negative impacts on students’ well-being and learning outcomes, for example by ensuring the provision of school transport services where needed (OECD, 2018[19]). In Portugal, educational authorities implemented complementary policies alongside the reduction of the number of schools to address the challenges of consolidation. These policies improved the quality and capacity in the school network, to potentially cushion the shock caused by school closures.

First, the close co-ordination between central and local authorities, responsible for identifying the underperforming schools in need of consolidation and ensuring the transport of students to their new schools, was instrumental to the success of the process. Municipalities, in partnership with civil parishes, played a prominent role in reducing the disruptive nature of school closures.

Second, at the time of the initial round of school closures, new school centres that offered youth and community programming were built to serve as small town hubs. Further, a new school transport system was developed to ensure students who suddenly had to commute to other localities could do so with no additional costs for families.

Figure 3.9. Change over time in school facilities, 2004-14

Source: DGEEC (2017), Educação em Números 2016 [Education in Numbers 2016], DGEEC.

Third, the Secondary Schools Modernisation Programme, led by the Parque Escolar agency, invested in refurbishing and modernising secondary school buildings. The additional capital investment stream permitted the expansion and requalification of school buildings that would otherwise lack the capacity to take new incoming students. All stages, from the planning process to the maintenance of completed buildings, included a thorough community involvement process (Veloso, Marques and Duarte, 2014, p. 410[22]). At the local level, this engagement took the form of information sessions and consultation meetings before and during the construction process, which brought together parents, teachers, students, school boards and non-teaching staff on the one hand, and engineers and architects on the other hand (Blyth et al., 2012, p. 47[23]) (see below for more on Parque Escolar). Independently from the Parque Escolar interventions, but as part of the overall strategy of consolidation, many small schools have also been replaced by new buildings with a minimum capacity for 150 students (Ares Abalde, 2014[24]).

Fourth, the organisation of school administration into clusters has also facilitated the consolidation process. Clustering allows students to be integrated into larger school communities, increasing access to a greater variety of services, such as extracurriculars or student counselling and career guidance. Relatedly, school clustering eased transitions of students across education levels. In the same cluster, students could more easily progress through the years within the same extended school community, allaying concerns associated with moving to different school environments and facilitating a sense of belonging at school. Furthermore, as resource planning is made at the cluster level, variations in demand for a particular school can be more easily dealt with by shifting human and material resources across commonly managed school buildings.

Finally, the new organisation of the school offer provided greater pedagogical coherence across education levels. Teachers are now more aware of student needs as they progress through different educational levels, provided that additional opportunities for professional collaboration in an extended school community are actually fulfilled (see Chapter 4).

Although consolidation plans across OECD countries are often met with strong opposition from students, parents, teachers and staff (Ares Abalde, 2014[24]), most stakeholder groups the review team spoke with did not express particular concerns with the general direction of the process, recognising it as a necessary step to rationalise provision in face of falling birth rates. However, particularly at the school level, stakeholders with whom the review team spoke voiced concerns related to uneven administrative oversight over the schools in the cluster, greater weight given to administrative tasks distributed to teachers and an unequal utilisation of collaborative potential across clusters (see Chapter 4). In fact, the clustering process has also led to unequal distributions of enrolled students in each cluster and number of schools per cluster (see Challenges section).

The physical infrastructure of schools requalified by Parque Escolar is of high quality

In 2007, the Portuguese Government launched an unprecedented plan to modernise and improve public secondary school infrastructures, implementing a new management and maintenance model and optimising the allocation of resources and the sustainability of school infrastructures (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]). The state-owned company Parque Escolar was established to carry out the programme. A total of 173 secondary schools have been involved, which means that the school infrastructure of more than two-thirds of all secondary school students in 2016 has been improved (Ministry of Education, 2018, pp. 67-68[1]).

In only one decade, the central government succeeded in building, renovating, upgrading and pedagogically modernising 173 upper secondary schools throughout the country. A strength of the Parque Escolar model is linking the design of the school building to the development of innovative and modern instructional spaces, such as advanced laboratories and flexible classroom layouts. Blyth and colleagues provide an extensive description of the Secondary Schools Modernisation Programme (Blyth et al., 2012[23]).

During school visits to sites intervened by Parque Escolar, the review team heard from students, parents, teachers and school administrators a high-level satisfaction with their new secondary school infrastructure. They stated that they felt the new buildings met the requirements of teaching and learning, well-being and social safety in school. Parque Escolar involved strategic and thorough infrastructural planning and maintenance. Nevertheless, the successful process and results of Parque Escolar highlight the poor physical condition of most other schools (see Challenges section).

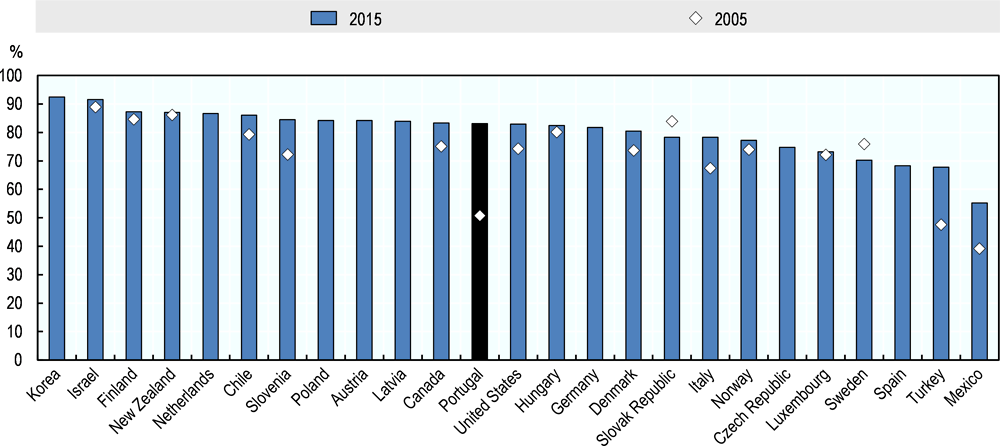

There is increased access to, and attainment in, upper secondary education

Graduation rates from upper secondary education have been climbing and are approaching OECD averages. Between 2005 and 2015, the proportion of upper secondary students under 25 years of age that graduate from secondary schooling jumped from 51% to 83% – by far the largest increase among countries for which there is available data (Figure 3.10). Interestingly, the increase in the secondary enrolment and graduation rates preceded the increase in the compulsory age of education to 18 years of age in 2009. In fact, between 2005 and 2015, the proportion of 18-year-olds enrolled in education increased from 66% to 81% (Figure C1.2 in OECD (2017, p. 251[9])). Declining rates of early school leaving and year repetition in basic education are important drivers of this change.

Figure 3.10. Change in graduation rates from upper secondary education, 2005 and 2015

Note: Countries with missing data for both periods or with missing data for 2015 are not presented. The change for OECD average is not presented due to missing data.

Source: OECD (2017), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en, Table A2.3.

It should be noted that the surge in graduation rates and expansion of the upper secondary schooling occurred in spite of efficiency-driven measures aimed at consolidating the school network and declining number of teachers (see also Chapter 4). Costs associated with the greater need of provision were also contained through a general increase in average class size, associated with the increased legal maximum number of students per class in 2013. Therefore, it seems that, while holding resources constant in the face of a growing secondary population, Portuguese secondary schools still increased the proportion of students graduating successfully. Additionally, clearly articulated standards – e.g. through a stable policy of national exams at the end of the 3rd cycle and during upper secondary education – have steered the quality and rigour of the curriculum delivered in the classroom. Greater emphasis should now be given to continue decreasing the still high rates of year repetition and early school leaving (see Challenges section).

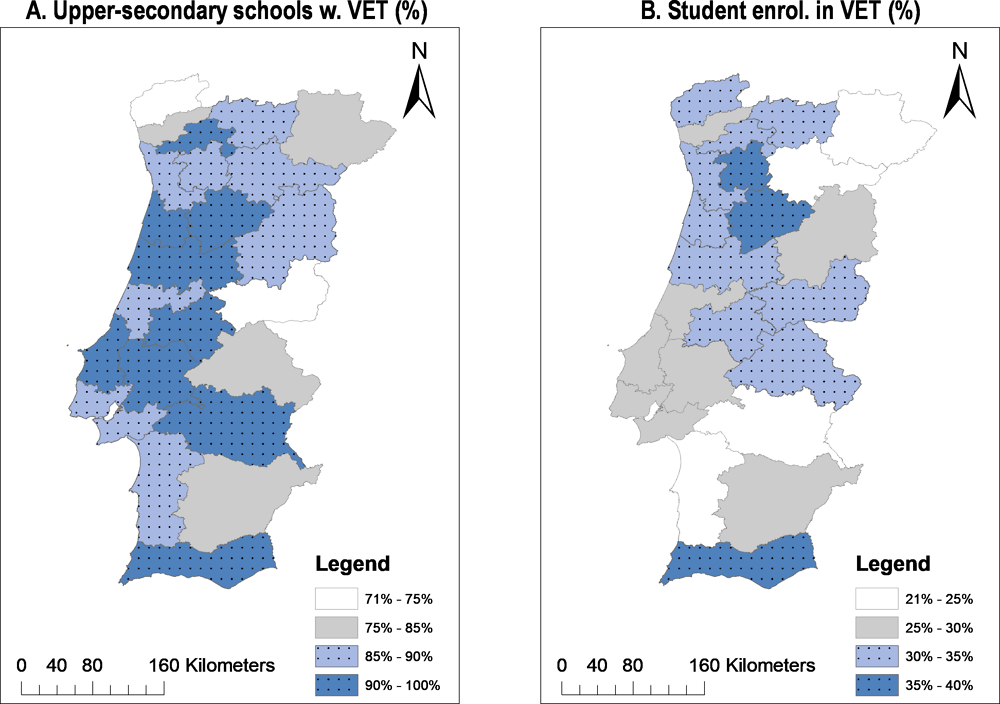

Efforts have been made to improve the profile of VET pathways

While Portugal has traditionally favoured enrolment in general education programmes in upper secondary education, education officials have gradually improved the profile of VET programmes. In particular, the number of students opting to enrol in professional programmes has grown simultaneously with the expansion of VET courses in mainstream educational institutions. According to administrative data for 2016, the great majority of public upper secondary schools in the country (89%) offers some type of VET programme – a consistent pattern across regions. In fact, the proportion of schools offering VET is above 70% in every NUTS III region (Figure 3.11, Panel A). Mirroring this pattern, there is no region in the country in which the proportion of students enrolled in school-based VET programmes is lower than 20%, with regions such as the Algarve having enrolment rates over 35% (Figure 3.11, Panel B).

Figure 3.11. Geographic variation in provision of vocational education and training (VET)

Note: Figures present only school-aged, initial VET programmes and enrolment by school-aged secondary students (under 24 years of age).

Source of administrative boundaries: Direção-Geral do Território (2016), Official Administrative Maps of Portugal ‑ Version 2016 [Carta Administrativa Oficial de Portugal ‑ Versão 2016], http://www.dgterritorio.pt/cartografia_e_geodesia/cartografia/carta_administrativa_oficial_de_portugal_caop_/caop__download_/carta_administrativa_oficial_de_portugal___versao_2016/.

Source: DGEEC administrative data, 2015/16.

According to recent evidence from Portugal, the choice to enrol in VET depends on such factors as the pathway options available in schools, students’ previous achievement, as well as the guidance and supervision of students by psychology and orientation services (Serviços de Psicologia e Orientação - SPOs) at school. Importantly, peers, family and teachers also influence the choice of track (Vieira, Pappámikail and Resende, 2013[25]). Similarly to other OECD countries, students that opt to enrol in VET tracks generally come from relatively more disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds and have lower chances of accessing higher education (Cruz and Mamede, 2015[26]; Henriques et al., forthcoming[27]). However, despite attracting students from lower socio-economic backgrounds, Cruz and Mamede (2015[26]) find that the expansion of VET pathways in Portugal has had significant positive impacts on the progression and outcomes of students in the labour market. In line with evidence from other countries, enrolment in the VET track has also been shown to increase the chances that low-performing students will remain enrolled in school compared to low-performing performing students who opted to enrol in the regular track (Henriques et al., forthcoming[27]). Stakeholders with whom the review team met repeatedly emphasised the expansion of vocational offer in schools as a good opportunity to attend the needs of students in risk of dropping out or willing to experience more school success in an alternative offer to the academic track.

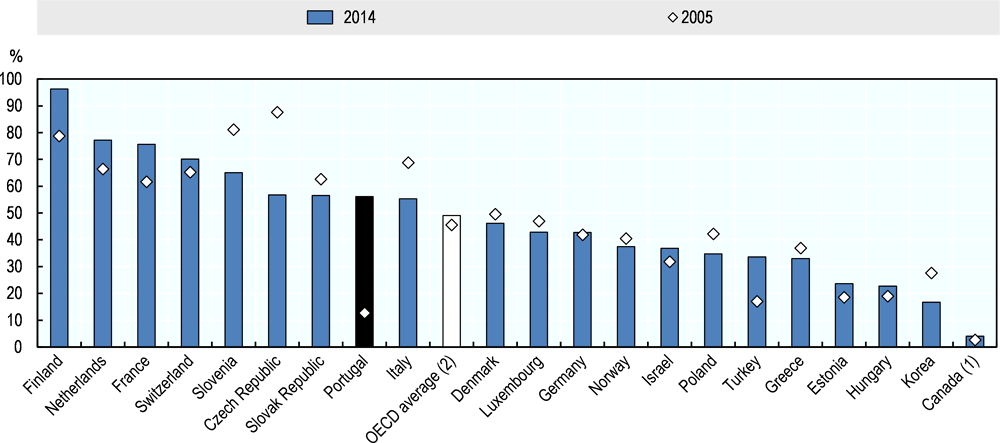

Alongside the expansion of VET offer, graduation and completion rates have increased. The proportion of students graduating from VET programmes in Portugal increased from only 13% in 2005 to 56% in 2014 – the largest growth among OECD countries (Figure 3.12). Likewise, the percentage of students completing professional courses in a given year climbed from 55% in 2002 to 74% in 2016 (Figure 1.4.5 in DGEEC (2017, p. 50[28])). Across all VET programmes, 51% of students conclude their studies during their theoretical duration, above the 49% among those in general programmes in 2015. But despite the progress, the proportion of VET students completing their studies on time is still considerably lower than other education systems with available data (Figure A9.3 in OECD (2017, p. 158[9])).

Portuguese educational authorities have taken specific steps to increase the status of VET programming through a range of initiatives to match the VET offer to labour market needs. First, work-based learning has been gradually built into professional programmes, while VET programmes have preserved academic coursework requirements in a school setting. In 2013, a reformulation of VET upper secondary syllabi introduced changes aimed at providing more training hours in a work context, continued expansion of vocational pathways in lower and upper secondary aimed at students in risk of dropping out and further harmonisation of VET programmes across upper secondary schools and IEFP training centres (Ordinance 276/2013).

Second, Portuguese authorities set, in 2014, the legal framework for Professional Business Reference Schools (Escolas Profissionais de Referência Empresarial – EPRE). EPREs are intended to be created by companies or employers’ associations willing to develop courses directly related to their activity (Decree-Law 92/2014). According to the government’s intentions, 50% of the teaching hours in the EPREs – excluding work-based learning – would be provided by companies’ employees with adequate pedagogical qualifications. Nonetheless, since the publication of the legal framework, no Reference Schools have yet started to operate. While the design of these schools appears promising, and despite review team inquiries into this policy development, it is unclear why none have opened.

Figure 3.12. Change in graduation rates of VET students in upper secondary education, 2005 and 2014

1. Year of reference is 2013.

2. OECD average is calculated only for countries with available data for all reference years.

Source: OECD (2016), Education at a Glance 2016: OECD Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.187/eag-2016-en, Table A2.4.

Third, Portugal has gradually developed a coherent national qualifications framework, which is data-driven and informed by consultation with labour market stakeholders. The procedure for ensuring the VET network has labour-market relevance is facilitated by a tradition of dialogue and stakeholder involvement in the discussions. In particular, vertical and horizontal co-ordination mechanisms have been put in place to steer the VET offer. The system for anticipation of skills, coupled with regulations on the limit of classes per field of study, help centrally steer the VET network of provision according to labour market needs. While vertical steering mechanisms can be effective tools to streamline vocational offer, the involvement of subcentral actors in the process – through the regional module of SANQ – incentivises local commitment and the sharing of common goals (OECD, 2018[19]). In turn, horizontal co-ordination can be leveraged through a network of almost 300 Qualifica Centres that help implement VET programmes at the school-level and guide young and adult students through the National Qualifications Catalogue (see also Chapter 1).

Fourth, Portuguese authorities have set higher quality standards for vocational programming. Alignment with the European Quality Assurance in Vocational Education and Training (EQAVET) system has provided an internationally agreed-upon framework for quality assurance of VET providers. An increasing number of schools are already included in this system, improving their esteem among students, families and companies. In particular, EQAVET certification is used as a criterion in decisions pertaining to opening new programmes or to extend the existing ones (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]).

Finally, all VET tracks lead to a double certification qualification in recognition of students’ mastery of both academic and vocational skill sets. Double certification holds the potential to foster transitions to academic pathways in post-secondary levels while remaining relevant for entering the labour market. Professional qualifications are organised into stackable modules that help facilitate the progression of students throughout the duration of their studies and to higher education levels. But challenges still remain regarding the fulfilment of such potential. A recent follow-up survey on the status of students one year after graduation has found that for those completing upper secondary education through VET tracks, only 34.1% were not employed but studying, 6.7% were both working and studying, while 18.9% were neither studying nor working (DGEEC, 2018[29]). Nevertheless, the number of VET students employed one year after graduation has been improving considerably in comparison to other waves of the survey (Ministry of Education, 2018[1]).

Extremely high rates of inclusion of students with Special Educational Needs (SEN)