This chapter examines the broad framework conditions that affect the operation of higher education in Mexico, focusing on governance arrangements, strategic planning and funding. The chapter first focuses on the broad governance of the higher education system and, in particular, the respective roles of the federal government, state authorities and individual higher education institutions. It goes on to examine recent national strategy for higher education, as articulated in the National Development Plan and Sectoral Education Programme, as well as the role and capacity of states in higher education planning. Finally, the chapter examines the level of public funding for public higher education institutions and the mechanisms used to allocate resources. For each of these three areas, the chapter provides a specific set of recommendations for improvement.

The Future of Mexican Higher Education

Chapter 3. Governance, planning and resources

Abstract

3.1. Focus of this chapter

In this chapter, we examine key elements of the public policy environment in which higher education providers in Mexico operate, looking in particular at the legal and governance framework, strategic planning, and public funding of higher education. These are areas where public authorities play an important role in all higher education systems, although with considerable variation in terms of regulation and intervention across jurisdictions.

In many countries, including Mexico, the oldest universities are older than the state in which they are located and have often developed with a strong degree of institutional autonomy. This is the case in Latin America, but also in the English-speaking world and most of continental Europe. Although universities are frequently public institutions, they have greater independence than most other parts of the public sector. Over time, particularly as higher education has expanded, governments have tended to increase their level of intervention in the regulation of higher education systems and have often sought to steer higher education institutions in line with goals established at a political level. Key examples of government intervention include:

Expansion of higher education enrolment and provision through provision of grants programmes for students, the creation of new institutions, or expansion of existing ones;

Introducing new types of institutions to meet national needs in professional or technological sectors (for example, through the creation of polytechnics in many countries in the 1960s to 1990s);

Establishment of national qualification frameworks that regulate the types of qualifications that exist, often in partnership with or under the leadership of academic communities, but sometimes with a strong political dimension (as in the case of the Bologna reforms in Europe that instituted a standard bachelor’s, master’s, doctorate degree structure, a single credit system and recommendations for external and internal quality assurance);

Facilitating coordination between parts of the education system and pathways between different levels of education and training: this may include determining general entrance requirements for higher education (deciding between open access and selective systems) or support for common application systems1;

Regulating employment conditions for staff, sometimes even through specific, jurisdiction-wide rules governing the employment conditions of academic staff;

Establishing common standards for external quality assurance in teaching, research, and funding external quality assurance bodies, and

Funding higher education: while governments have long been providers of funding, in the past this was often unconditional. Increasingly, governments ask for greater accountability from higher education institutions and greater proof of the quality and impact of the activities higher education institutions conduct. There has been an increase in competitive funding and performance-related funding that seeks to incentivise institutions to act in specific ways and achieve specific goals.

As the role of public authorities in higher education has expanded, so has the volume of legislation and regulation that affects the sector and the need for effective forms of coordination between policies and communication between authorities and higher education institutions.

This chapter focuses on three dimensions of the broader public policy framework for higher education in Mexico:

1. The legal, administrative and procedural framework for the higher education system that establishes operating rules, the roles and responsibilities of different actors in the system and shared process and systems, as well as governance bodies that regulate, coordinate, support and guide the institutions that make up the national system of higher education;

2. The political and policy strategies that identify challenges, establish goals for the future development of higher education in Mexico and provide a framework for more specific government policies and a reference point for institutional strategies; and

3. The resourcing of the higher education system, with a particular focus on the mechanisms that are used to distribute public funding to higher education institutions and ensure it is spent effectively.

3.2. Governance frameworks for higher education in Mexico

3.2.1. Frameworks and governance bodies in higher education systems

Higher education institutions operate within a particular legal, administrative and procedural environment, which affects their legal status, their rights and obligations and how they undertake their work. Within this environment, it is conceptually possible to distinguish: a) the legal framework (laws) that establish basic rules and principles; b) the administrative and procedural framework, composed of “system-level” administrative bodies and procedures and processes in which higher education institutions participate; and c) coordination and governance bodies that help to coordinate and promote communication within the higher education system.

Within complex systems of higher education, the legal framework might be expected to establish the ground rules of the operation of the sector and provide legal certainty to higher education institutions, public authorities and citizens. Primary legislation governing higher education varies between countries in its scope as a result of differing legal and political traditions, but public authorities typically use it to define:

The legal status of public higher education institutions, their primary objectives (teaching, research, engagement) and their basic rights and obligations;

Where applicable, basic rules for the establishment and operation of private higher education providers;

The division of responsibility for public policy relating to higher education (regulation, strategy, funding etc.) between levels of government in a state;

The rights and obligations of coordinating public authorities (such as ministries of education) in relation to funding, sharing of information and reporting; and

The status and roles of any other public bodies involved in regulating or coordinating higher education, including coordinating councils, quality assurance agencies, statistics agencies or arms-length funding or coordination agencies.

In federal systems, the constitution and broader legislative frameworks often make higher education the primary responsibility of state governments. This is the case in the United States, Canada, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium or Australia, for example. In such systems, it is common to establish coordination mechanisms at the level of the federation, so that state education systems remain compatible and can work together. It is also common to assign certain functions to the federal level. In the United States and Germany, for example, responsibility for student financial support lies with the federal governments.

The administrative and procedural framework comprises both administrative entities of public authorities who oversee, regulate and fund higher education (generally government departments) and system-wide procedures managed by public authorities or independent agencies, which may include:

A national qualification framework, a common credit system, and rules for transfer and articulation of studies;

A common, unique, and persistent student identifier, that allows students’ records to be maintained and transferred and their progress through the education system and subsequently to be tracked anonymously;

A unified system of institutional data collection and an agreed methodology for reporting data to government and calculating key indicators;

An agreed and published methodology(ies) for the funding of public higher education institutions;

A coordinated assessment, application and prioritisation process allocating seats in public higher education institutions;

A detailed student aid methodology for the determination of eligibility and award of grant or loan benefits; and

A comprehensive and compulsory system of quality assurance.

In both unitary and federal higher education systems, organisations often exist to promote communication and coordination between (often autonomous) higher education institutions and government. This may simply be through sector umbrella bodies, such as Rectors’ Conferences or University Associations, which are independent of government, or it may be through formal coordinating councils or similar bodies established by public authorities. The existence of such coordination bodies and communication channels should facilitate effective policy-making and the work of individual higher education institutions.

The remainder of this section analyses the extent to which the current legal frameworks for Mexican higher education provide clarity and legal certainty about the roles, rights and responsibilities of different actors in the system; whether the administrative and procedural frameworks create effective system-wide procedures; and whether effective coordination bodies are in place to support good governance and policy-making.

3.2.2. Strengths and challenges

A complex and evolving system of federalism, lacking a clear legal division of responsibilities for higher education

Higher education in Mexico has developed within a system of government that is marked by strong national authority and comparatively weak state governments that operate within an evolving system of federalism. It is also characterised by a legal and doctrinal vision of autonomy that has sharply circumscribed the role of public authorities in relation to the oldest and largest higher education institutions in the country. These features of the governance context in Mexico have resulted in a comparatively weak role for public authorities in steering large parts of the higher education sector (the autonomous research universities) and a lack of clarity about the real division of responsibility for higher education policy among the federal government, the governments of the states and individual higher education institutions.

For most of the 20th century Mexico’s system of government “…operated on the principles of theoretical federalism and de facto centralism,” in which the bulk of key governmental decisions were taken at the federal level, and most public spending was done by the federal government (Ordorika, Rodríguez Gómez and Lloyd, 2018[1]). Mexico’s largest and most prominent higher education institutions, its federal universities, were established and funded by national authorities. Non-university higher education institutions, such as the National Polytechnic Institute (founded in 1936) were also created and directed by national authorities. Government recognition of private institutions was also the responsibility of national authorities, who established a centralised licensing process for these institutions. Owing to the fiscal and political pre-eminence of the national government, and the limited capabilities of most states, by 1950 only 12 of Mexico’s 32 federal entities had established state universities, and until the 1970s, 80% of the nation’s higher education students were enrolled in the capital city (OECD, 2008, p. 43[2]).

As part of wider changes to the federal system in the late 1970s, responsibility for provision and regulation of higher education - and the fiscal resources to meet these responsibilities - were provided to states through new federal legislation, most importantly through the Fiscal Coordination Law (Congreso de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 1978[3]). States were also encouraged by federal authorities to create State Commissions for Higher Education Planning (COEPES), and given shared responsibility for licensing private higher education programmes with the power to issue their own certificates of Recognition of Official Validity of Study Programmes (RVOE). Additionally, efforts were made to create new higher education institutions across the country, including autonomous state universities where these did not exist, and other types of institutions established as decentralised entities of state governments. The latter group included the decentralised Institutes of Technology, Technological Universities and Polytechnic Universities (OECD, 2008[2]).

The distribution of responsibilities among governments remains complex and uncertain. Mexico does not have a Higher Education Act that comprehensively establishes the relationship between public authorities and higher education institutions, in contrast to the legislation in place in many Ibero-American countries, including Colombia (1992), Argentina (1995), Spain (2001), Portugal (2007), Peru (2014), and Chile (2018). These laws characteristically define, among other things, what institutions must do to achieve university status, what forms for autonomy are available to university institutions, how institutions are to govern themselves and take account of their social obligations, and how the quality of provision is to be assured.

Mexico has a Higher Education Coordination Act (Ley para la Coordinacion de la Educación Superior), dating from 1978 (Congreso de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 1978[4]). The statute stipulates that federal, state, and municipal authorities are to act “in a coordinated manner” (Article 8) in relation to higher education. However, their respective responsibilities to higher education institutions and procedures for coordination of their activities are not outlined with precision. The legislation specifies activities using vague terms such as “coordination”, without defining what this means in practice, and fails to make clear the respective roles of the federal and state governments, referring simply to “the State” (public authorities in general). For example, Article 11 provides that:

In order to develop higher education in response to national, regional and state needs and the institutional requirements of teaching, research and dissemination of culture, the State [el Estado] will coordinate this type of education throughout the Republic, through the promotion of harmonious and solidary interaction between higher education institutions and through the allocation of public resources available for this [public] service, in accordance with the priorities, objectives and guidelines provided by this law. (Congreso de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 1978[4])

During the course of meetings with higher education stakeholder groups, the Review Team was told that the 1978 Higher Education Coordination Act was badly outdated, having been adopted when the nation’s higher education system had not yet taken its modern form, and that the Act failed to specify sufficiently the responsibilities for public authorities in relation to higher education institutions, and the converse. In 2017 and 2018, deliberations took place to modernise the 1978 legislation, and resulted in the National Association of Universities and Higher Education Institutions (ANUIES), with the support of a number of members of Congress putting forward a proposal for a new draft Act (Anteproyecto de Ley General de Educación Superior). The stated intention of this exercise was to clarify the roles and responsibilities of different actors in the higher education system. However, the draft Act has not to date been debated in Congress and has thus not progressed towards becoming legislation.

Despite the imprecise legal framework governing higher education governance, national authorities in Mexico, through the federal Secretariat of Public Education (SEP), are de facto responsible for:

Setting plans for the development of the higher education system that are contained in the six-year Sectoral Education Programme;

Proposing a budget framework within which federal budgets for public higher education institutions and programmes are developed;

Establishing and managing federal higher programmes (extraordinary funding);

Establishing governance rules and providing strategic direction to non-autonomous federal higher education institutions;

Agreeing with state authorities on the governance rules and funding levels for non-autonomous state higher education institutions; and

Coordinating and implementing, in part, the regulation of private higher education institutions.

State education authorities, in contrast, continue to have a more limited role than is typically the case in other federal systems. They exercise responsibility for the establishment and shared funding of state higher education institutions, for the (shared with federal authorities) regulation of private higher education providers , and the development of state higher education plans that complement the federal government’s sectoral education programme.

Despite clear political will in some cases, states lack the resources and capacity to play a strong role in higher education policy-making and funding

Despite increased decentralisation over the last three decades and the formally shared responsibility for higher education between the federation and states, the states continue to possess modest fiscal and administrative capacities, which limit their ability to take on a stronger role in higher education, one similar to that seen in many other federal countries. As a recent OECD Better Policy Review (OECD, 2017[5]) noted:

Mexico remains a centralised country. Large spending areas are controlled by the federal government. Local government expenditure and investment shares in GDP and public spending are among the lowest in the OECD. At the same time, the distribution of functional responsibilities across levels of government is complex, undermining the effectiveness of policy delivery and public investment. Federal powers are extensive and sometimes overlap with responsibilities of states and municipalities.

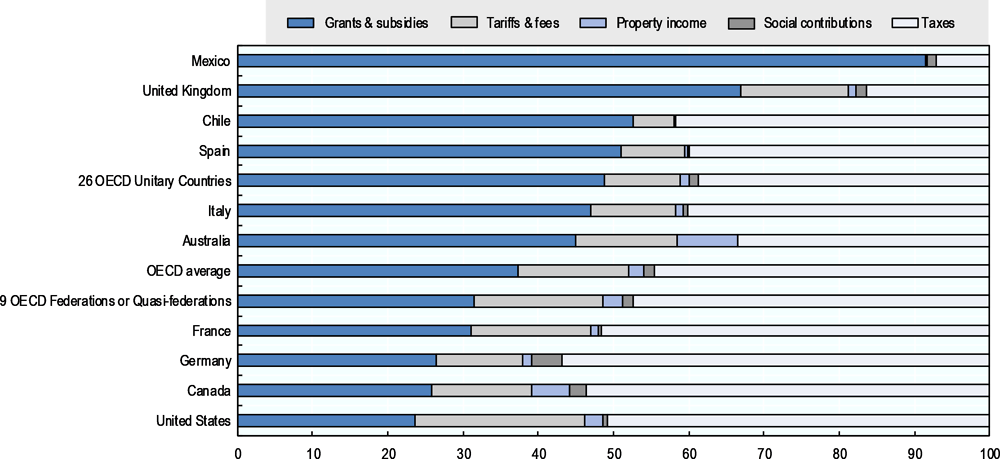

States in Mexico have limited tax-raising capacity and rely on financial transfers from the federal government (see Figure 3.1). They receive over 90% of their revenue from transfers from the federal government and less than 10% from taxes. This pattern contrasts sharply with other OECD federal states such as Canada, Germany, Switzerland, and the United States, in which, on average, transfers account for less than a third of sub-national revenue, and state and local taxation account for almost one-half of state and local government revenues.

Figure 3.1. Funding of sub-national government

Source: OECD (2016) Sub-national Government Structure and Finance https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SNGF.

The federal transfers received by states in Mexico take three main forms. First is core funding allocated under Section (Ramo) 28 of the federal budget, referred to as “participations”2, which states have discretion in allocating. Second are so-called “federal contributions”3 which are earmarked for specific purposes – including aspects of education - under Section 33 of the federal budget and allocated to states on the basis of economic need. Third are specific “agreements” (convenios), through which the federal government provides a grant to a specific public institution.

The amount of Section 28 transfers each state receives depends on their contribution to national economic output, while the amount of Section 33 transfers is calculated to compensate states with high levels of economic disadvantage. This means the level of federal transfers and the proportions available for earmarked or discretionary spending vary between states. As highlighted in the more detailed discussion of funding later in this chapter, the level of funding allocated in convenios for specific institutions, which include the State Public Universities, depends on the outcomes of negotiations between the state and federal governments.

The fact that large proportions of the federal transfers that states receive are earmarked for existing fixed costs (payment of staff salaries and running costs, for example), or tied to agreements with specific institutions means that that state governments have comparatively few resources they can use for discretionary spending on higher education. Economically stronger states, which receive higher levels of non-earmarked funds and have higher revenues from state taxes, theoretically have more resources available that they could chose to allocate to higher education. However, the challenging fiscal and economic environment of recent years mean that all state governments have had limited room to increase public investment.

Within the limits imposed by the legal framework and available funds, it appears that some Mexican states have made greater efforts than others to develop coherent state higher education policies and direct resources to these initiatives. Stakeholders interviewed by the OECD team during the review visit argued that the administrative capacity of state administrations and the political will of individual governors and state governments varied considerably between states in Mexico. As a result, the efforts invested in developing state higher education systems vary correspondingly.

An uneven pattern of intervention by public authorities between subsystems: from laissez-faire to micro-management

Although governmental authority and resources in Mexico rest principally with national authorities, the authority of public officials in relation to higher education institutions is highly uneven. Three very different patterns of public authority and institutional autonomy co-exist within Mexico: for autonomous universities (federal universities and State Public Universities4); for non-autonomous public higher education institutions; and for private higher education institutions. The distinctive understanding and practice of university autonomy in Mexican higher education means that while some parts of the higher education system function under comprehensive and detailed control from the centre of government, others - the autonomous universities - have functioned with virtually no guidance or steering from government.

University autonomy in Mexico is based in principles first outlined in the Cordoba Declaration of 1918, and it evolved in a context of a strongly centralised and authoritarian regime, where the nation’s largest autonomous university became a centre of mobilisation and confrontation between student movements and government (Ordorika, 2003[6]). The principle of university autonomy, first articulated in the Constitution of 1917, is recognised in Article 3, Subsection VII of the current constitution, which guarantees the autonomy of universities, and provides that:

Universities and other institutions of higher education to which the law grants autonomy, will have the power and responsibility to govern themselves; to fulfil their educational goals, pursue research and disseminate culture in accordance with the principles of this article, respecting the freedom of teaching and research and free debate of ideas; determine their plans and programmes; they will set the terms of entry, promotion and retention of their academic staff; and they will manage their assets. Labour relations, for both academic and administrative staff, will be regulated by section A of article 123 of this Constitution, in the terms and with the modalities established by the Federal Labour Law in a manner consistent with [institutional] autonomy, the freedom of teaching and research and the objectives of the institutions to which this subsection refers (Gobierno de la República, 2017[7])

As higher education in Mexico underwent expansion in the 1960s and 1970s, it did so with wider autonomy than elsewhere in Latin America (Levy, 1980[8]), with federal and state universities awarded autonomous status by legislatures. Today, by contemporary international standards, such as those outlined by the European University Association (EUA, 2018[9]), autonomous universities in Mexico continue to exercise wide control over key decisions about internal organisation and governance; the allocation and management of their budgets; human resources (recruitment, salaries, dismissals, and promotions); and especially academic autonomy (including decisions about student admissions, academic content, and the introduction of degree programmes).

While public authorities do not have a highly developed legal basis for steering autonomous higher education institutions, since the 1990s the scope of institutional steering by public authorities has nonetheless widened with respect to state autonomous universities. Extraordinary targeted funding for state universities (in addition to basic funding) was adopted in 1991, and, as discussed later in this chapter, has been used to incentivise state universities to work towards national goals. The rules governing use of extraordinary funds significantly reduce institutional autonomy with respect to the allocation and management of budgets in question.

State Public Universities with Solidarity Support, Intercultural Universities, Technological and Polytechnic Universities, decentralised and federal Institutes of Technology, normal schools and other forms of public institution such as music academies, do not operate as autonomous institutions. Rather, federal non-autonomous institutions operate under the direction of federal authorities (SEP), while non-autonomous state institutions operate under the direction of both federal (SEP) and state education authorities (state education or higher education secretariats). This direction may be exercised in great detail, with the SEP exercising control over funding levels, curriculum, staffing levels, and infrastructure improvements. For example, by some accounts, the selection of rectors and top officials in Intercultural Universities, while notionally the responsibility of the universities, is subject to intervention by state or federal authorities (Ordorika, Rodríguez Gómez and Lloyd, 2018, p. 291[1]).

Private organisations are permitted to provide higher education under the Mexican constitution (Article 3, VI). However, the constitution requires that the State “grant and withdraw the recognition of official validity to studies that are carried out in private schools.” Private universities that wish to award validated credentials have a regulatory process they must undertake for market entry (see Chapter 4). However, they subsequently function with a high level of autonomy, with the capacity to take their own decisions about internal organisation and governance, staffing, resource allocation, and academic decisions.

As a consequence of a strongly centralised federal system in which governing authority is circumscribed university autonomy, there is in Mexico a sharply uneven legal and political scope for the exercise of central government authority, with virtual “no-go zones” (of autonomous university institutions) and areas within which public authorities exercise detailed control.

A proliferation of higher education subsystems and administrative units hinders system-wide policy-making and processes

Mexican scholars suggest that the complexity of the higher education landscape in Mexico means it is inaccurate to speak of a higher education system in the country:

Higher education is not a system in the strict sense, defined in the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española as “a set of rules and principles relating to a subject rationally linked to each other” or “a set of things that are related to each other in an orderly manner and contribute to a determined goal”…One of the characteristics of the “subsystems of higher education” is their disarticulation and fragmentation, which limits their ability to achieve synergies and contribute to achieving the goals of higher education. (Mendoza Rojas, 2018, p. 8[10])

Successive waves of policy initiatives have led national authorities to develop new institutions and institutional types in the interstices where they have freedom of action, creating Polytechnic Universities, Technological Universities, Intercultural Universities, and a national distance university. The proliferation of “subsystems” of different institutional types has a) led to a fragmented institutional structure in the administrative apparatus that oversees higher education in Mexico and b) further complicated the already challenging development of system-wide norms and administrative procedures.

As new subsystems have been created, they have generated new administrative entities in the Secretariat for Public Education, Directorates-General or Coordination offices responsible for funding or steering institutions within its purview. The cumulative result of this pattern is that the higher education landscape and the SEP is highly compartmentalised and fragmented. This has been repeatedly noted by international observers (OECD, 2008[2]), national researchers (Mendoza Rojas, 2018[10]), and higher education stakeholder organisations (ANUIES, 2018[11]). SEP has an Under-secretariat for Higher Education (SES) that provides a notional integration to much of national higher education policy. However, some aspects of higher education, such as the regulation of private institutions and Intercultural Universities5, are located outside the under-secretariat. Within the under-secretariat there are three nominally “decentralised” institutions (the Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, the Universidad Abiertia y a Distancia de Mexico, and the Tecnológico Nacional de México) and five administrative units (see Table 3.1) that work semi-autonomously.

Table 3.1. Administrative units in the Under-secretariat for Higher Education (SES)

|

Abbreviation |

Main tasks |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Directorate-general for university education Dirección General de Educación Superior Universitaria |

DGESU |

Oversight and steering of public universities |

|

General coordination [office] for Technological and Polytechnic Universities Coordinación General de Universidades Tecnológicas y Politécnicas |

CGUTyP |

Oversight and steering of Technological and Polytechnic Universities |

|

Directorate-general for higher education for educational professionals Dirección General de Educación Superior de Profesionales de la Educación |

DGESPE |

Teacher education – oversight and steering of the normal schools |

|

Directorate-general for professions Dirección General de Profesiones |

DGP |

Professional certification – issuing professional certificates |

|

National coordination [office] for higher education scholarships Coordinación Nacional de Becas de Educación Superior |

CNBES |

Coordination and award of student scholarships |

Source: Organigrama de la Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP, 2018[12])

This compartmentalisation of higher education system and its governance into separate subsystems has combined with the traditionally weak regulatory role of the Mexican state in higher education and the influence of university autonomy to make it harder to develop some of the common norms and procedural standardisation that are typically seen in high-performing higher education systems. Striking examples are:

The absence of a widely recognised and used national qualifications framework that situates higher education qualifications in the wider landscape of educational credentials.

The absence of system-wide credit accumulation and transfer system that underpins the qualifications systems, ensures the comparability of qualifications.

The absence of a single, common student identifier to ensure educational records can be shared between institutions and systems.

The comparative weakness of the educational statistical system (despite some recent improvements).

The absence of a comprehensive system of external quality assurance for higher education

The absence of commonly agreed principles and cost guidelines to guide the allocation of public funds to public higher education institutions

We address the implications of the current funding system later in this chapter and examine external quality assurance mechanism in the next chapter. The lack of the other main elements of system-level infrastructure listed above further weakens the existence of a coherent higher education system in Mexico. In many higher education systems in the OECD, national qualifications frameworks, credit accumulation and transfer systems (such as the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System, ECTS) and unique student identifiers have been introduced to increase the coherence and integration of national higher education systems. In particular, these mechanisms facilitate the mobility of students between institutions and study programmes at different levels of education (from undergraduate to postgraduate, for example) and cooperation between different institutions in the same level (allowing joint programmes or mobility periods at other institutions). As seen with the introduction of the ECTS in European countries, the implementation of credit systems is complex, as it is tightly intertwined with a range of other factors, such as the definition of expected learning outcomes, assessment methods and marking practices, and requires strong leadership and close cooperation between higher education institutions (European Commission, 2018[13]).

In Mexico, steps have been taken to develop a national credit accumulation and transfer system, in the form of the Sistema de Asignación y Transferencia de Créditos Académicos (SATCA), principles for which were adopted by the National Association of Universities and Higher Education Institutions (ANUIES) in 2007. However, despite widespread acceptance among the academic community, implementation of system stalled in the early years of implementation as a result of limited funds and resistance among university administrators (Sánchez Escobedo and Martínez Lobatos, 2011[14]) Recent updates to the General Education Act (LGE) (Congreso de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 1993[15]) explicitly call on the federal government to put in place national qualifications framework and national academic credit system (LGE, Article 12, paragraph IX). However, progress in translating this into practice has been slow (ANUIES, 2018[11]).

A lack of effective coordination bodies, despite strong sector organisations

In addition to the imprecise legal basis and fragmented structure of the institutional landscape in Mexican higher education, the absence of strong coordination bodies at national and state level further hinders the development of strong, system-wide procedures and norms and coherent regional higher education systems.

At state level, many of the states do have a State Commission for Higher Education Planning (Comisión Estatal para la Planeación de la Educación Superior, COEPES), notionally responsible for coordinating different higher education providers at state level and aligning supply of higher education with regional demand. Nevertheless, it appears that the COEPES have long struggled to fulfil this role effectively. In 2011, the SEP reported that only 22 of the 32 federal entities had an operational COEPES (ANUIES, 2018, p. 53[11]). Moreover, stakeholders consulted by the OECD Review Team argued that the COEPES that do exist lack the capacity and resources to have a significant impact on the coordination of state higher education systems and are in most cases de facto inoperative. The most recent policy position paper from ANUIES calls for the COEPES to be “reinstated”, implying they are all but non-existent at present (ANUIES, 2018[11]).

While state coordination bodies might be expected to support the development of state and regional systems of higher education, as discussed above, a series of common standards and processes are needed for an effective national higher education system. In other federal systems, national coordination bodies exist to agree on common standards for higher education systems to ensure state higher education systems remain compatible and interact with federal governments in the fields where the national government has responsibilities (such as student support or research)6. Over the years, there have been various attempts to establish such a coordination body in Mexico, including the National Coordination for Higher Education Planning (Coordinación Nacional para la Planeación de la Educación Superior, CONPES) and the National Council of Higher Education Authorities (Consejo Nacional de Autoridades de Educación Superior, CONAES), relaunched in 2016. However, as with the COEPES, these instances appear to lack the clear mandate and sustainable resources to operate effectively.

In comparison to other OECD countries, non-government sector organisations play a particularly strong role in Mexican higher education, to some extent compensating for the lack of strong formal coordination bodies. ANUIES not only formulates position papers, but plays an important role in collecting and analysing data about the higher education system. As a representative body for a large part of the higher education sector, the association will remain a key stakeholder in Mexican higher education. While the Federation of Private Mexican Higher Education Institutions (FIMPES) is primarily a representative organisation for the private sector, it too has engaged in tasks that go beyond those fulfilled by its counterparts in many other OECD countries, notably through the establishment of its own institution accreditation system.

3.2.3. Key recommendations

In the medium term, reform the federal legislation governing the higher education system to define a clearer division of responsibilities

The 1978 Higher Education Coordination Act provides little clarity on the respective roles, rights and responsibilities of the main actors in the higher education system and their relationships which each other. Although, in the short term, it may be possible to improve coordination and develop effective policies for higher education within the existing legal framework, ultimately, a more transparent legal framework is needed to provide the clarity and certainty needed for the long-term development of higher education in Mexico. The federal government, in consultation with the states and autonomous universities, should therefore develop new federal legislation that specifies the respective roles of the federal government (SEP) and the governments of the states, ensuring that these are distinct and complementary, and makes clear the rights of autonomous institutions and their responsibilities to citizens and government.

Taking into account the financial and administrative capacity of state governments, the guiding principle should be that government tasks should be undertaken at the lowest level possible that guarantees effectiveness and efficiency. Tasks related to a) creating system-wide norms and procedures and b) distribution of financial resources between territories and social groups should rest with the federal authorities. Federal authorities should also assume primary responsibility for establishing the rules regarding licensing higher education (RVOE), external quality assurance, the form and validity of qualifications, credit transfer and accumulation, certification of studies and data reporting, as well as for student aid and most targeted institutional funding. State authorities should focus primarily on shaping and adapting their regional higher education systems to fit regional circumstances and needs, within the common rules and frameworks established at federal level. To ensure shared engagement in the state higher education systems, it makes sense for states to maintain a role in providing funding to public institutions, alongside federal authorities. This could potentially be on the 50:50 basis currently used for many subsystems, but with transparent and unified allocation rules and procedures (see section on funding below).

While respecting the principle of academic freedom enshrined in the Mexican Constitution, the new legislative framework should also make more explicit the responsibilities of autonomous public universities. Universities in many OECD member countries have a strong tradition of autonomy, but are equally expected to respect the rules of agreed national frameworks (on qualifications, access rules, quality assurance etc.) and be accountable to the public for their use of taxpayers’ money. The principle of accountability, as well as autonomy, should guide the formulation of the new federal legislation.

Strengthen the capacity of states to play a strong role in coordinating and steering regional higher education systems that respond to regional needs

In the framework of an adjusted allocation of responsibilities between the federal and state authorities, state authorities should focus on aspects of higher education policy where they can make a real difference at regional level. In some areas, state authorities could remain responsible for the implementation of common rules or programmes agreed at federal level – in areas such as licensing private higher education providers or payment of student scholarships. In other areas, states should have freedom to shape policy to help develop their local and regional higher education systems. This might include convening regional higher education institutions and supporting joint projects to foster cooperation and sharing of resources (see below); identifying regional skills and innovation requirements to which higher education must respond; promoting access to higher education among specific regional populations (complementing a national system of student grants) and providing targeted funding to support quality, relevance and equity through state-level programmes, as long as clearly coordinated with national extraordinary funds (see below).

States currently have varying levels of administrative capacity to implement regional higher education policies and invest varying amounts of resources in higher education, including their respective autonomous State Public Universities. To be able to fulfil the role sketched out above in full, most states need to develop their administrative capacity and have access to adequate financial resources. Devolution of responsibility to individual state governments should therefore take into account the administrative and financial capacity of the states in question. A differentiated system, whereby states that demonstrate greater capacity and meet established criteria gain additional responsibilities could be considered.

To strengthen administrative capacity, the federal government could consider a dedicated targeted funding programme, made conditional on high quality, rational proposals and some level of match funding from state governments. Moreover, to ensure the sustainability of state funding for higher education (state shares of funding for institutions, administrative tasks and regional targeted funds), the federal government (SEP and the Secretariat for Finance and Public Credit) should review current allocation mechanisms to states. In particular, they should examine whether the current balance of earmarked federal transfers (Ramo 33), block transfers (Ramo 28), institutional agreements (convenios) and state resources from local taxes provides the right level and mix of resourcing.

Within a more favourable legal and funding environment, states should be held publicly accountable for the performance their higher education policies, through effective monitoring and publication of results.

Work towards a system of responsibly autonomous institutions

Autonomous higher education institutions are likely to be best placed to design and implement effective educational programmes and develop relevant research, innovation and engagement activities that respond to their specific mission and the environment around them (EUA, 2018[9]). Particularly for publicly funded institutions, with autonomy comes responsibility to act in the general public interest and make good use of resources. Serving the general public interest includes abiding by commonly agreed and transparent rules about things like qualifications, quality assurance, study credits and certification, which influence the effectiveness of the whole higher education system. It also implies cooperating with public authorities and other higher education subsystems. Making good use of resources implies transparency about the use of public funds, effective management of resources, and responsiveness when problems are identified.

Autonomous universities in Mexico have historically tended to equate autonomy with freedom from government intervention. Mexico’s distinctive vision of autonomy emerged and developed in response, in important part, to an authoritarian political regime. However, in an age of multi-party democracy it is incumbent on these institutions to work constructively with federal and state authorities and institutions in other sectors to develop a more effective and coherent higher education system in Mexico. The OECD review team was generally impressed by the constructive attitude of representatives of autonomous institutions that they met, which are also reflected in the most recent policy position paper from university association ANUIES (ANUIES, 2018[11]).

In contrast to the autonomous universities, many other public higher education institutions have very limited institutional autonomy, with most of their activities governed by decisions taken in Mexico City. This is particularly the case of the Institutes of Technology - which from part of the Tecnológico Nacional de México - and the normal schools. For Institutes of Technology, there is scope to grant individual schools that have are of an adequate size greater responsibility in budgetary and staffing matters, as well as more flexibility to tailor study programmes to local needs. For smaller institutes, responsibility could be devolved to regional alliances of institutions that would share some management functions. This latter approach could also work for public normal schools, which currently suffer from micro-management from central government, but are also characterised their small scale and weak management and administrative capacity. As such, regional alliances could also provide a solution for these institutions.

Complete work to create essential system-wide frameworks and procedures, while simplifying federal administrative structures steering higher education policy

The federal administration needs to take a stronger lead in the creation and implementation of system-wide frameworks and procedures, including a national qualifications framework; a credit transfer and accumulation system; a single student identifier and an effective system of educational statistics. As discussed in the next chapter, federal authorities also have a key role to play in enforcing universal licensing of private institutions and facilitating – with the higher education sector - comprehensive external quality assurance.

Developing these system-wide frameworks and procedures will require some initial investment of federal resources to cover start-up and initial implementation. It may be appropriate to create a dedicated extraordinary funding programme to support development of procedures and administrative infrastructure at federal level (within SEP, or in associated non-governmental bodies) and support implementation in institutions. Some system-wide frameworks – as an improved statistical system - will require additional ongoing investment. Others, such as a qualifications framework and credit system cost little to maintain once they are in place and active.

To support the process of creating a more coherent system of higher education in Mexico, it would also make sense to streamline some of the internal structures in the SEP, to ensure:

that responsibility for all higher education subsectors is included under the Under-secretariat for Higher Education or, at least, within a single department in a restructured SEP;

that there are sufficient resources at the level of the Under-secretariat (or equivalent, future department) to maintain strategic overview of the whole higher education system and push forward the system-wide projects noted above (this might be a unit reporting directly to the Undersecretary) and;

that cooperation with the National Council for Science and Technology (CONACyT) – the federal government’s research and innovation agency – is strengthened.

Clarify the mandates and strengthen the capacity of coordination bodies for higher education at federal level and in each state.

In a large and fragmented higher education system like that in Mexico, cooperation bodies at state and federal level can support the development of stronger regional higher education systems and a more coherent national system. Nevertheless, attempts to date to create such bodies in Mexico have been largely unsuccessful. To increase the chances that newly established or reinvigorated bodies are effective, it is crucial that they have clearly defined and realistic mandates and tasks and adequate resources to perform their roles. It is important to avoid creating bureaucratic entities that serve no valuable purpose: the effectiveness of any new coordination bodies must therefore be carefully monitored and their missions periodically reviewed.

Taking these conditions into account, it would be valuable to create coordination forums at federal level and in each state. A federal body would bring together representatives of state higher education systems, representatives of the federal government (the SEP and potentially the Secretariat of Finance) and representatives of national agencies and sector associations (representatives of quality assurance bodies, ANUIES, FIMPES, etc.). Its role could include:

Helping to steer and monitor the development of national system-wide frameworks and procedures (see above);

Ensuring effective communication between federal government and regional higher education systems and;

Providing input into federal development plans and education and science plans and providing a forum for identification of shared challenges, problems in policy implementation and possible solutions.

The state bodies, most probably building on the existing COEPES, where these exist, could focus on:

Acting as a liaison point between higher education institutions and state governments, and between institutions from the different subsystems (a forum for discussion and launch of cooperation projects);

Providing input to state development plans and state education and science agendas;

Being a forum for decision making about certain strategic issues, such as expansion or development of study programmes and extra study places and;

Sharing practice in the implementation of national frameworks and procedures, pinpointing challenges and helping to develop solutions if these fall within the scope of state responsibilities for higher education (issues related to the national frameworks would need to be discussed and resolved in the national forum).

3.3. Higher education strategy in Mexico

3.3.1. The role of strategy in higher education

Governments use strategy documents to establish goals in specific fields of public policy and to identify actions that will be taken to achieve the goals established. Although their precise legal forms may vary between jurisdictions and policy fields, such strategies often seek to provide a guiding framework for other policy activities affecting the subjects they address. Such policy activities may include new primary and secondary legislation, regulatory activities and public funding programmes and projects. Policy strategies may be drafted to reflect an established political vision – perhaps based on an election manifesto or coalition agreement - or be the product of open consultation exercises that seek to take into account a broad spectrum of stakeholder interests. In many cases, they result from a combination of these two approaches.

Governments in many OECD countries have formulated, or encouraged the formulation of, policy strategies to articulate goals for the development of their higher education systems. In some OECD countries, such as France (Ministère de l’Éducation nationale, 2017[16]) or Ireland (Department of Education and Skills, 2011[17]), the development of recent higher education strategies has been entrusted to expert groups, with the emerging recommendations subsequently endorsed in full or in part by government. In other cases, such as the most recent higher education strategies in the Netherlands (Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, 2015[18]) or England (BIS, 2014[19]), higher education strategies have been developed within government departments under the authority of the relevant minister and the cabinet. In common with the United States (Department of Education, 2018[20]), Mexico has adopted strategic goals for its higher education system as part of a broader, government-led education strategy (SEP, 2013[21]).

Across these countries, strategies for higher education tend to identify similar challenges and establish broadly similar objectives, in areas such as expansion of enrolment, equity, quality, relevance or innovation. In contrast, differences in the composition and autonomy of the higher education system, and in the organisation of government between countries, have a major impact on the kinds of action included in strategy documents. Central government in jurisdictions with a strong tradition of government intervention may propose changes and initiatives where government takes a strong lead, including through new legislation and regulations that impact directly on the operation of higher education institutions. In federal systems and systems where higher education institutions have stronger autonomy, central governments necessarily rely more on indirect stimulus and support measures, and place more emphasis on negotiation and cooperation between different actors in the higher education system.

Irrespective of differences in government forms and traditions, good policy strategies – in higher education as in other sectors - might be expected to:

1. Be coherent with, and complementary to, related strategies in the same or other policy areas formulated at other levels or in other parts of government.

2. Use reliable evidence to assess the current situation in the higher education sector and identify (internal) strengths and weaknesses and (external) opportunities and threats;

3. Take into account – but not necessarily adopt - the views and perspectives of higher education providers, funders of higher education, students, employers and other sections of society;

4. Provide a clear vision of how the higher education should develop and goals that should be achieved within a defined timeframe;

5. Establish objectives which are specific, measurable, attainable, realistic and time-bound (SMART);

6. Specify actions that will be taken to achieve the objectives, who will take these and what resources will be used and;

7. Indicate mechanisms for monitoring progress and addressing problems encountered in achieving objectives over the lifetime of the strategy.

The sections that follow assess the national strategies currently in place to guide the development of higher education in Mexico, identifying strengths and challenges, before formulating recommendations for the next generation of strategies being prepared by the new government.

3.3.2. Strengths and challenges

A tradition of national planning and consultative strategy-setting, but a lack of clarity about implementation activities and limited transparency in monitoring

Mexico has a well-established tradition of strategic planning at federal level. Article 26 of the Mexican constitution and the national Planning Law (Congreso de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 2018[22]) require the establishment of a National Development Plan (PND) for each six-year presidential term. This plan, which by law should take into account the results of a wide-ranging consultation of citizens, sets out broad priorities for the development of Mexico. As such, it provides a framework of reference for sectoral policy programmes, including a Sectoral Programme for Education (discussed below); for Development Plans drawn up by state governments and; for annual budgeting processes at federal and state level.

The National Development Plan for the period 2013-2018 (Gobierno de la República, 2013[23]), covering the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto, establishes “Mexico with quality education” as one of its five strategic priorities. Under the education priority, the Plan includes specific objectives, “strategies” and “action lines” that explicitly address higher education. These are summarised in Table 3.2. Alongside the action lines, which vary from general objectives to specific activities, the PND establishes a set of indicators that are intended to overall monitor progress in the areas covered by the Plan.

The National Development Plan does not, however, establish fixed targets or benchmarks to be reached. The only indicator focusing explicitly on higher education in the PND is the completion rate (literally, “terminal efficiency”)7 in higher education. In addition, the PND includes Mexico’s position in two international composite indicators, which are published annually and also consider higher education. The first of these is the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index, which scores countries on a scale of one to seven in a range of dimensions including in the category “higher education and training” (Schwab, 2017[24]). Secondly, under the strategic goal “Mexico with global responsibility”, the PND includes the Elcano Index of Global Presence (Real Instituto Elcano, 2018[25]), which incorporates the “number of foreign students in tertiary education on the national territory” as one of its variables.

Table 3.2. Higher education in the National Development Plan 2013-2018

Objectives within the strategic priority “Mexico with quality education”

|

Objective |

“Strategy” |

“Action lines” relevant to Higher Education |

|---|---|---|

|

3.1 Develop the human potential of Mexicans through quality education. |

3.1.3 Ensure that study programmes and plans are relevant and contribute to students’ progressing successfully and acquiring skills they will need in life. |

Creating an entrepreneurial culture through study programmes at HE level. Reform the evaluation and certification system for higher education. Promote development of joint postgraduate programmes with foreign higher education institutions (HEIs). Create a programme to allow students and staff to spend periods at HEIs abroad. |

|

3.2 Ensure inclusion and equality in the education system. |

3.2.1 Increase opportunities to access education in all regions and for all sectors of the population. |

Establish alliances with HEIs and social organisations to reduce illiteracy and poor educational results. |

|

3.2.2 Increase support to disadvantaged and vulnerable children and young people to reduce illiteracy and poor educational results. |

Use a grants programme to increase the proportion disadvantaged young people that transition from secondary education to upper secondary and from this level to higher education. |

|

|

3.2.3 Create new educational services, expand existing ones and exploit the capacity of existing facilities. |

Increase in a sustained way the coverage of (enrolment in) upper secondary and higher education to achieve at least 80% in upper secondary and 40% in higher education. Promote diversification of the educational offer in line with the requirements of local and regional development. |

|

|

3.5 Make scientific and technological development and innovation a pillar of social and economic progress. |

3.5.1 Contribute to raising investment in RTD annually to reach a level of 1% of GDP. |

Promote investment in RTD in public HEIs. |

|

3.5.4 Contribute to the transfer and use of knowledge, linking HEIs and research centres with the public, social and private sectors. |

Promote links (vinculación) between HEIs and research centres with public, social and private sectors. Promote entrepreneurial development of HEIs and research centres to foster technological innovation and self-employment among young people. Promote and simplify the registration of intellectual property between HEIs, research centres and the scientific community. |

|

|

Horizontal Strategy I: Democratise productivity. |

Increase and improve the cooperation and coordination between all government agencies to bring technical and higher education to places which lack an adequate educational offer and marginalised areas. Strengthen institutional capacity and links between upper secondary schools and HEIs with the productive sector and encourage the continual review of the educational offer. Establish a system for tracking graduates from upper secondary and HE and conduct studies of employer needs. |

|

|

Horizontal Strategy II: Responsive and modern government. |

Strengthen mechanisms, instruments and practices for evaluation and accreditation of quality in upper secondary and higher education for campus, mixed and distance courses. |

|

|

Horizontal Strategy III: Gender perspective. |

Promote access, staying on and timely completion of studies by women at all levels and particularly in upper secondary and higher education. |

Source: (Gobierno de la República, 2013[23]) – translation by the OECD Secretariat.

On the basis of the PND, the federal Secretariat of Public Education (SEP) is required to develop a separate strategy for the activities under its responsibility: the Sectoral Education Programme (PSE). The most recent PSE (SEP, 2013[21]) has six strategic objectives for the education sector as a whole. For each strategic objective, the PSE establishes intermediate objectives, each with a set of actions. The most relevant objectives of the PSE for higher education are:

Strategic Objective Two8 focuses on the quality and relevance of upper secondary education, professional training and higher education. Specific objectives include improving quality assurance mechanisms; developing the capacity of HEIs in research and innovation; improving the relevance of higher education programmes to national needs; exploiting information and communication technologies in higher education (including for distance education) and supporting improvements in higher education infrastructure and facilities.

Strategic Objective Three9 focuses on social equity, including access and completion in higher education. Specific objectives include improving student financial support; ensuring further expansion of the system is aligned to regional needs and; “support” for institutions to help them reduce drop-out rates.

Strategic Objective Six deals with strengthening research and innovation capacity. Specific objectives include a commitment to increase investment in R&D (notably though funding for CONACyT programmes); expanding and improving the quality of postgraduate education (including through increase coverage of quality assurance mechanism) and promoting better links between HEIs and the productive sector. Objective six has a specific focus on expanding the capacity and quality of postgraduate education in science and technology fields.

The Sectoral Education Programme establishes five progress indicators related specifically to higher education and, unlike the PND, fixes specific targets for the end of the programming period in 2018, as show in Box 3.1.

Box 3.1. Higher education indicators in the Sectoral Education Programme 2013-18

1. Indicator 2.2 (Quality and relevance objective): Increase the proportion of students enrolled in programmes recognised for their quality (accredited by CIEES or COPAES) from 61.7% in 2012 to 72% in 2018;

2. Indicator 3.1 (Inclusion objective): Increase the gross enrolment rate in higher education (for higher education, calculated as the number of enrolled students as a proportion of the total population aged 18-22) from 32.1% in 2012 to 40% in 2018;

3. Indicator 3.2 (Inclusion objective): Increase the gross enrolment rate in higher education for individuals from households in the bottom four income deciles, with the target of raising the rate from 14.7% in 2012 to 17% in 2018.

4. Indicator 6.1 (R&D objective): Increase expenditure on research and development undertaken in higher education institutions [HERD] as a proportion of GDP from 0.12% in 2012 to 0.25% by 2018.

5. Indicator 6.2 (R&D objective): Increase the proportion of doctoral programmes in the fields of science and technology in the [CONACyT] National Programme for Quality Postgraduate education (PNPC) from 63.5% in 2012 to 71.6% in 2018.

Although the Sectoral Education Programme fixes targets for drop-out rates (tasas de abandono escolar) for primary, secondary and upper secondary education, it does not establish equivalent targets for higher education. This is curious, as the National Development Plan includes completion rates (eficiencia terminal) in all levels of education, including tertiary, as indicators of progress.

Progress in relation to the goals of the both the National Development Plan and the Sectoral Education Programme and policy activities related to these strategies are outlined in the annual “Government Reports” (Gobierno de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 2018[26]), which enumerate actions taken by government in each policy field each year. Data relating to the Sectoral Education Programme indicators on enrolment in accredited programmes and gross enrolment rates are published and regularly updated on the higher education section of the SEP website (Dirección General Educación Superior Universitaria (DGESU), 2018[27]).

If considered in light of the characteristics of good strategies outlined above, the most recent National Development Plan and Sectoral Education Programme demonstrate both strengths and weaknesses.

It is positive that both documents seek to take an evidence-based approach to strategy-setting, including extensive analyses of the challenges facing higher education, even if this analysis is in some cases constrained by a lack of reliable data (see discussion below). Those drafting the documents received well-formulated inputs from stakeholders in the higher education sector - a notable example being the proposals prepared by the National Association of Universities and Higher Education Institutions (ANUIES) in advance of the 2012 presidential elections (ANUIES, 2012[28])10. Both strategic documents also take into account the results of broader consultations with citizens, reflecting Mexico’s strong tradition in this respect. Furthermore, the priorities and action lines identified are in general both aligned with the diagnoses in the documents themselves and relevant to the broader challenges facing higher education in Mexico and discussed in this report.

While the OECD review team was generally impressed by the level of debate about key issues in higher education policy and the awareness of government officials and stakeholders about the challenges the Mexican system faces, it considers that the current strategic policy framework for higher education in Mexico fails to fulfil its potential in guiding effective policy for a number of reasons:

1. First, the complementarity between the National Development Plan (PND) and the Sectoral Education Programme (PSE) – and in particular the specific added value of the PSE – is not sufficiently clear. As part of its whole-of-government strategy, the PND already establishes comparatively detailed objectives and lines of action to guide higher education policy. Although it provides a more fine-grained breakdown of objectives and lines of action, the PSE does not provide a greater level of detail on the specific actions that will be taken to implement the strategy and achieve its objectives. The indicators specified in the PND and the PSE do not appear to be fully consistent and the relationship between the two indicator sets is not clear. As a result, the Sectoral Education Programme to some extent merely duplicates the PND, rather than providing an easily understandable and actionable roadmap for future policy.

2. Second, the logical relationships between the challenges identified, the actions that are proposed and the expected results and impacts are not adequately explained in the Sectoral Education Programme. Diagnoses, objectives and actions lines and indicators are presented in separate chapters without clear links between them. The PSE includes a very large number of action lines with limited or no explanation of each and only very few indicators with no clear explanation of how the planned actions will affect the indicators chosen. As a result the PSE reads rather like a list of good intentions. A programme with fewer action lines, each with clearly identified indicators of progress (at an appropriate level of ambition and meeting SMART criteria) would make it possible for policy makers to understand where their activities fit into the wider picture and for everyone to monitor progress towards goals more effectively.

3. Third, the choice, in the PND and PSE, to formulate general objectives that apply to all sectors of education and training makes it harder to understand and monitor the strategy for individual educational sectors, including higher education. As educational institutions and the public bodies responsible for their supervision and steering are largely organised by educational sector, a sector-by-sector structure in strategy documents would seem more appropriate to aid readability and facilitate implementation and monitoring.

4. Finally, leaving aside the inherent difficulty of reporting clearly on implementation of a strategy as wide-ranging and unspecific as the PSE, current systems for reporting progress appear inadequate. The Government Reports are long and lack a clear analytical framework and structure for reporting, while monitoring data is presented in a raw form without explanatory analysis that would allow stakeholders and citizens to gain a clear understanding of progress.

Despite recent improvements, incomplete data about the characteristics and performance of the higher education system still hinder policy-making

As already highlighted, reliable information about the characteristics and performance of the higher education system is crucial to developing an accurate diagnosis of the challenges the sector faces and – on this basis – designing appropriate policy measures to improve the situation. Mexico has put in place a compulsory data reporting system coordinated by SEP’s Directorate-General for Planning, Programming and Educational Statistics (DGPPyEE). All educational establishments are required to report key information on institutional structures, income, enrolment and graduation at the beginning of every academic year using standardised reporting tools, referred to as Format 911, submitted through an online reporting portal (SEP, 2018[29]).

SEP’s Directorate-General for University Higher Education (DGESU) publishes basic data on the higher education system, derived primarily from the Format 911 reporting system, on its website (Dirección General Educación Superior Universitaria (DGESU), 2018[27]). This database provides accessible data on enrolment, completion of studies (egreso) and formal graduation (titulación), broken down by federal state and higher education subsystem. Data on enrolment rates in accredited programmes (a key indicator in the Sectoral Education Programme) from COPAES and CIEES are provided on the same site, while data on teaching staff and basic funding data are available on the website of SEP’s planning division (DGPPyEE, 2018[30]). The National Association of Universities and Higher Education Institutions (ANUIES) contributes directly to the development of the data collection tools and conducts its own analysis of the information collected (Mendoza Rojas, 2018[10]; ANUIES, 2018[11]).

While key elements of a comprehensive data system for higher education are in place, a number of variables that would be valuable for policy-making and evaluation are not currently available in Mexico. Some of these information gaps are common to all or nearly all higher education systems and are inherently difficult to address. As representatives of SEP note in a recent presentation to universities (Malo, 2018[31]), policy makers in Mexico – in common with the counterparts in most other countries - lack good information about educational processes: the content of programmes, pedagogical approaches, support given to students etc. To address this to some extent, in 2016-17, SEP undertook a wide-ranging survey of institutional leaders, teaching staff and students in higher education (SEP, 2018[32]), focusing on the educational approaches used within institutions. While such surveys can only ever provide a partial picture of reality and face many methodological difficulties, the results of the TRESMEX exercise do appear to provide some useful insights for policy-making. In contrast to many OECD countries, Mexico does have some reliable data on student learning outcomes, from the standardised student assessments undertaken by the National Centre of Evaluation for Higher. Education CENEVAL. However, these data are not comprehensive, nor representative, as they are the results of a subset of programmes that choose to evaluate their learners.

Other current information gaps in Mexico have been tackled in other countries and could be addressed in Mexico to improve understanding of the higher education system. Two issues stand out in particular:

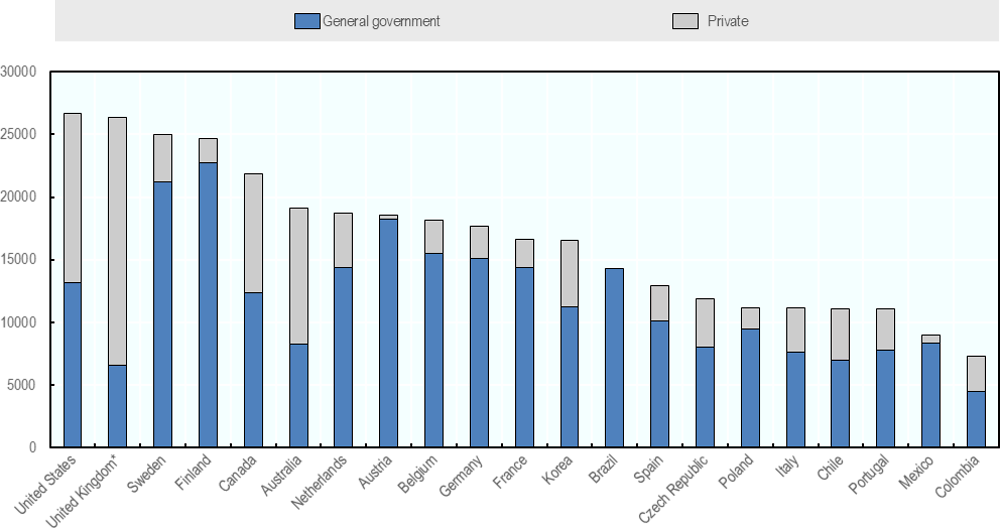

1. First, as far as the OECD review team can determine, consolidated data on educational spending per student in the different subsystems is not available. As discussed below, the absence of transparent, consolidated data on public and private spending on education per student makes it hard to compare resourcing levels and assess efficiency. It seems likely that many higher education institutions do not have internal accounting and cost allocation systems in place to allow them to report spending on educational activities with complete accuracy. Particular complications include the difficulty of distinguishing staff costs associated with education and research (a challenge common to all higher education systems) and the inclusion of upper secondary and higher education services in the same budget in many public universities (a challenge specific to Mexico).

2. Second, accurate, true cohort data on students’ educational careers and subsequent education and employment status and outcomes is not available in Mexico. At present, completion (egreso) and formal graduation (titulación) rates are often reported in relation to current enrolment levels rather than on the basis of individual’s actual progression within the educational system. Given the legitimate focus on completion and graduation rates (eficiencia terminal) in Mexico, the shortcomings of current data should be addressed. At the same time, despite commitments made in both the current National Development Plan and the Sectoral Education Programme, Mexico lacks a comprehensive system of graduate tracking. This hampers good student choices in selection of programmes, undermines transparency and accountability and makes internal and external monitoring of institutional performance more challenging. While high rates of informal employment in the Mexican economy create specific challenges, better information on employment outcomes can be very useful for informing policy and practice in a changing economy. Mexico does have a universal Unique Population Registry Code (Clave Única de Registro de Población, CURP) which could be used as a basis for better follow-up of individuals within and after education, following developments in practice in several of other education systems.

Ongoing efforts to engage with the higher education sector across the country, but with uncertain results

As noted in the discussion of the National Development Plan and Sectoral Education Programme above, it is hard to obtain a clear picture of progress in relation to the many action lines for higher education contained in these national strategies. This in part reflects the fact that activities and follow-up of the strategies is dispersed across the different Directorates-General of the SEP. One of the most substantial follow-up activities related to the Sectoral Education Programme has been the so-called “Comprehensive higher education planning initiative” (PIDES), started in 2015 and still underway at the time of writing (SEP, 2018[33]).

Described as a “collective reflection and working exercise”, PIDES has been conceived as a way for the SEP to engage with the higher education community in Mexico, to further refine priorities identified in existing strategies and develop specific projects involving groups of HEIs working towards the priorities and objectives identified. The exercise has involved the organisation of eight two-day sessions each year since 2016 in different regions of Mexico, each bringing together representatives of around 120 higher education institutions to discuss challenges and develop projects. A total of 83 inter-institutional projects in seven thematic areas and involving 721 HEIs have been started (Malo, 2018[31]).