This chapter examines the external mechanisms in place in Mexico to assure the quality of higher education. Unlike many other OECD member countries, Mexico does not have a comprehensive and mandatory system of external accreditation and quality assurance for higher education providers. Rather, for undergraduate programmes, it relies on the voluntary participation of higher education institutions in external accreditation processes organised by non-governmental accreditation bodies. At postgraduate level, the National Council for Science and Technology (CONACyT) plays a significant role in external quality assurance. The chapter assesses government policy in relation to external quality assurance and the relevance and likely effectiveness of the structures and processes currently in place, before providing a series of specific recommendations for improvement.

The Future of Mexican Higher Education

Chapter 4. Quality in higher education

Abstract

4.1. Focus of this chapter

Well-functioning systems of higher education ensure the quality of the higher education programmes offered to students, and the relevance of the skills they develop to life beyond higher education – as citizens and as working professionals. They do this while permitting – and encouraging - higher education institutions to engage in innovation – with respect to valuable new course content, new technologies or learning approaches. Below we briefly outline the characteristics of effective quality assurance systems, and then examine the performance of Mexico’s system in light of these characteristics.

Many variables can affect the design of quality assurance systems in higher education. National contexts have a strong impact on how quality assurance systems are organised, and there is no one-size-fits-all institutional model of good practice. However, the analyses of various international associations working in the field of quality assurance in higher education point to a growing international consensus around a set of principles that can guide the design of effective external quality assurance. Based on international guidelines and available literature, some key attributes of effective external quality assurance systems are summarised in Table 4.1 below.

Table 4.1. Characteristics of effective quality assurance systems

|

Aspect of the system |

Characteristics of effective QA systems |

|---|---|

|

1. Objectives and scope of QA processes. |

The objectives of quality assurance {QA] processes are clearly formulated and relevant to the challenges faced by the higher education system. The QA system is comprehensive every higher education institution awarding a recognised credential participates in the system. An appropriate balance is struck between avoiding poor quality provision and improving existing provision, including provision that is already judged to be of good quality. |

|

2. Definition and measurement of quality fitness, relevance, and diversity. |

The quality of teaching and learning is evaluated in light of its capacity to develop skills needed for a lifetime of active citizenship, professional success, and intellectual growth. QA procedures consider the relevance of programmes and skills to society and to the labour market, and engage external stakeholders with a commitment to quality. Definitions and indicators of quality are flexible and recognise quality in different forms in different types of educational programmes (e.g. academic vs professional courses). Quality is measured using an appropriately wide range of relevant and reliable indicators, including input, process and output indicators. |

|

3. Responsibility for quality and for quality assurance. |

Teaching staff and higher education providers are clearly identified as those with primary responsibility for delivering quality. Subsidiarity: decisions about quality are taken at the lowest level possible while maintaining effectiveness and adequate accountability. Quality assurance agency/ agencies act in the public interest; are adequately resourced; and are sufficiently independent from both the higher education sector and government. Additional government initiatives to promote quality are coordinated with quality assurance systems to ensure consistency. |

|

4. Use of information about quality. |

Where appropriate, evidence of poor quality is used to eliminate poor quality provision, with demonstrable results. Information about the performance of programmes and institutions is used by institutions to improve quality, and made public to ensure transparency. |

|

5. Adaptation to innovation. |

The QA system adapts flexibly to take account of changes in the way teaching and learning are offered, and supports the adoption of valuable new course content, new technologies or learning approaches. |

Source: Developed by the OECD Education and Skills Directorate, drawing on INQAAHE Guidelines of Good Practices 2016 (INQAAHE, 2016[1]); Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG, 2015[2]) and; CIQG International Quality Principles: Toward a Shared Understanding of Quality (CHEA, 2016[3]).

The design of licensing, evaluation, and accreditation procedures for higher education in Mexico falls short of these principles.

Mexico lacks an authoritative public quality assurance body. It has a variety of public and non-governmental bodies that engage in licensing, evaluating, and accrediting higher education programmes, and in assessing student learning. Though the federal government attempts to coordinate their work, there is no single framework for quality assurance, and they function with different criteria, standards and procedures to evaluate quality of programmes and institutions, not as a system.

The work of accreditation and evaluation bodies is not comprehensive. Many higher education programmes in Mexico at the undergraduate and postgraduate level are not subject to external evaluation and accreditation procedures.

Public policies and institutional leaders are less strongly oriented towards the continuous improvement of quality than in other higher education systems.

The work of CENEVAL to undertake standardised assessments of student learning outcomes helps to focus the quality on the development of skills; however, participation in its assessments is limited.

Quality standards used in external accreditation and quality assessment are not suitably linked to labour market relevance, and experts from the world of practice, including firms and non-profit bodies, are not consistently engaged in quality processes.

The definition and measurement of quality in higher education programmes is beginning to adapt to the diversity of provision, including professional and distance education, though further progress is needed.

The common landscape of indicators to measure inputs, processes, and outputs – such as cohort graduation rates, and graduate employment and earnings - is badly underdeveloped, and hampers quality assurance.

There are no effective procedures for the accreditation of higher education institutions, preventing them from taking an appropriate role in assuring the quality of their programmes.

Evidence about institutional performance is not used to ensure public transparency, and appears to play a modest role in eliminating poor provision.

The varied and voluntary arrangements for quality in higher education do not typically constrain innovation in new technologies, courses, or pedagogical approaches, and do little to promote these developments.

In this chapter, we examine the mechanisms for quality assurance that lead to these results, and identify options for their improvement.

4.2. Mexico’s existing mechanisms for quality assurance

The existing mechanisms for external quality assurance of higher education provision in Mexico fall into four categories:

Procedures regulating the establishment of new higher education programmes in private institutions – effectively a form of licensing;

Procedures for the external evaluation and accreditation of undergraduate programmes;

Procedures for the external evaluation and accreditation of higher education institutions (limited to specific cases in Mexico) and;

Procedures for external evaluation and accreditation of postgraduate programmes.

These four regulatory and quality assurance-related functions exist in many OECD countries, albeit in varying forms and combined in different ways. In Mexico, as in some other OECD countries, private providers are subject to distinct licensing rules, which public sector providers do not have to follow. However, in contrast to many other OECD higher education systems, all aspects of the external licensing and quality assurance process are essentially voluntary for higher education institutions.

4.2.1. Licensing Private Higher Education Programmes

The creation of study programmes by private institutions in Mexico is not subject to compulsory approval or monitoring by public authorities. If, however, private higher education institutions wish for a programme to be recognised as part of the National Education System, and for graduates of the programme to obtain a professional certificate (cédula profesional) or professional title (titulado profesional), they must obtain official recognition of the programme, and a separate recognition for each location in which the programme is offered (SEP, 2018[4]). This recognition (or licensing) process is known as Recognition of the Official Validity of Study Programmes (Reconocimiento de Validez Oficial de Estudios, or RVOE). Academic programmes of all levels (short-cycle, bachelor’s (licenciatura), master’s and doctorate) and all types of educational modalities (face-to-face, distance and blended) are subject to this process of recognition. In 2018, 21 981 study programmes offered by 1 918 private institutions held a RVOE.

If private institutions choose to offer the study programme without recognition, they have a legal obligation to state that the programme offers “studies without recognition of official validity”, and students may consult the website of the federal Secretariat for Public Education (SEP) to identify whether a programme is recognised (SEP, 2018[5]). Holding a cédula profesional or título profesional is required for entry to postgraduate study in a higher education programme that is part of the National Education System, and may frequently be beneficial when seeking employment. However, these formal certificates are not indispensable. Fewer than three-quarters (72.5%) of all students who completed their studies (egresados) in bachelor’s programmes in 2016-2017 obtained formal certification from their programmes to become a titulado.

The SEP awards a RVOE that is valid on a nationwide basis for study programmes in private institutions. State government authorities can also issue RVOEs for study programmes in private institutions; however, these are valid only within their own state. In addition, federal and state autonomous universities can authorise private operators to deliver study programmes that are like those they offer, similar to a franchising model (incorporación).

Governments award an RVOE when the study programme meets conditions with respect to staff, infrastructure and curriculum. SEP officials train state officials and invite them to adopt procedures and criteria consistent with those they have developed, although exact conditions and procedures needed to obtain a RVOE vary from one state to another, and between state and federal governments. SEP has worked to align RVOE standards among authorities who are authorised to recognise programmes. A ministerial agreement from November 2017, referred to as Agreement 17/11/17, (SEP, 2017[6]) established revised requirements and mechanisms for RVOEs awarded by SEP, including procedures to simplify the RVOE process.

The SEP RVOE approval process consists of a desk-based review of educational plans, instructional materials, and web-based resources submitted by the institution; and, for institutions without a prior RVOE, a site visit to assess the suitability and safety of facilities. Site-based inspections to ensure continuing compliance with the RVOE, or to commence an administrative process to withdraw it, are initiated in response to complaints from students, news reports, or recommendations from state authorities, according to SEP officials who oversee the process.

4.2.2. External programme evaluation and accreditation

Public and private higher education institutions are not obligated to have their programmes of study undergo external evaluation or accreditation; however, they may volunteer to do so. The evaluation of undergraduate programmes is organised by the Inter-institutional Committees for the Evaluation of Higher Education (Comités Interinstitucionales para la Evaluación de la Educación Superior) or CIEES, and their accreditation by the Council for the Accreditation of Higher Education (Consejo para la Acreditación de la Educación Superior) or COPAES.

CIEES was established in 1991 as an initiative of the National Association of Universities and Higher Education Institutions (ANUIES), and, in 2009, was relaunched as an independent, non-profit civil association. CIEES is comprised of nine committees, seven of which focus on broad fields of knowledge, such as health sciences or agricultural sciences, and two of which focus, respectively, on the management and external engagement activities of institutions. The committees perform evaluations of public and private institutions, for all modes of instruction – face-to-face, blended and distance courses – and at study programmes at all degree levels.

Following the submission of a self-evaluation, CIEES draws upon a pool of over 1200 external peer evaluators to organise visits by expert teams, who carry out site-based reviews (CIEES, 2018[7]). The relevant committee makes a decision on the quality of the programme or institution. Over 350 evaluations are carried out annually, and evaluations can result in one of three categories of quality designation, two of which are classed as “level one” (with durations five and three years respectively), and another (level two) that indicates recognition of “good” quality is not granted (CIEES, 2018[8]).

The second body, COPAES, is an independent, non-profit civil association that operates as coordinating body or umbrella organisation: it defines a reference framework for accreditation of academic programmes, and recognises and supervises 30 accrediting organisations (Organismos acreditadores). These accrediting organisations carry out the work of assessing programmes in different fields of study, and range in focus from veterinary medicine (CONEVET, Consejo Nacional de Educación de la Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia) to the social sciences (ACCECISO, Asociación para la Acreditación y Certificación de Ciencias Sociales). The accrediting agencies draw upon a pool of more than 3 500 evaluators, who are higher education instructors, researchers, and, in some cases, from firms (COPAES, 2018[9]).

The accreditation framework established by COPAES identifies ten domains of programme quality on which accrediting organisations are to focus, including:

|

Academic staff |

Support services for learning |

|

Student experience |

Extension and linkage |

|

Curriculum |

Research |

|

Evaluation of learning |

Infrastructure and equipment |

|

Comprehensive training |

Administrative management and financing |

This framework further disaggregates each of these domains into criteria and associated indicators. With respect to the student experience, for example, accredited programmes are required to report on processes of student selection, induction, and grouping, as well as progression though the programme and formal certification (titulación) at its end. The framework also specifies the evidence needed to support programme evaluation. In the case of the student experience, programmes must provide evidence with respect to completion rates (“terminal efficiency”) and graduates’ results in CENEVAL’s standardised exit examinations for bachelor’s programmes (Exámenes Generales para el Egreso de Licenciatura, EGEL). Once obtained, the programme accreditation remains valid for a period of five years. At the time of writing, the 30 agencies recognised by COPAES had accredited 3 797 programmes in 393 institutions (COPAES, 2018[9]).

The evaluation and accreditation activities performed by CIEES and the bodies accredited by COPAES are mostly overlapping, but, in part, complementary. Stakeholders with whom the OECD review team met noted that higher education institutions designate programmes with clear professional profiles for accreditation by agencies recognised by COPAES, while simultaneously relying upon CIEES to carry out reviews for study fields where no specialised agencies of COPAES are available, or where they wish to have distance or blended programmes evaluated. Some higher education institutions choose to participate in both processes. Taken together, programmes positively evaluated by CIEES (at level one, with a five-year quality designation) and accredited by COPAES are designated by SEP as “programmes of quality” and encompass about one-half (53%) of undergraduate enrolments in Mexico (SEP, 2018[10]).

4.2.3. Institutional evaluation

Both CIEES and COPAES assess the quality of individual higher education programmes – or, in the case of CIEES, some functional areas within higher education institutions. However, neither evaluates institutions in toto, or academic departments. Mexico has one evaluation process focused on higher education institutions, as distinct from programmes: the institutional evaluation process organised by the Mexican Federation of Private Higher Education Institutions (Federación de Instituciones Mexicanas Particulares de Educación Superior, FIMPES). Created in 1982, FIMPES is an association of 109 private universities, both non-profit and for-profit. While FIMPES members comprise only four percent of private institutions, together they contain just over half of enrolment in private higher education institutions, and 18% of all higher education enrolment in Mexico (FIMPES, 2018[11]). FIMPES admits institutions to membership following an external, peer-review process of institutional evaluation. In this process, academic units, services, and management are subject to assessment against a set of ten indicators ranging from institutional philosophy to financial resources. First implemented in 1994, this evaluation process has been supported by SEP, which since 2003 has permitted universities accredited by FIMPES to seek SEP’s approval to join a “Register of Academic Excellence” (Registro de Excelencia Académica) permitting them to access SEP’s Programme for Administrative Simplification and thereby benefit from a streamlined RVOE process (FIMPES, 2018[12]). In 2018, 38 private institutions were part of the register, and were authorised to follow simplified and expedited procedures for establishing new programmes or modifying existing programmes (FIMPES,(n.d.)[13]).

4.2.4. Quality assurance of postgraduate education

As with undergraduate programmes, accreditation of postgraduate programmes in Mexican higher education is not mandatory. However, the National Council for Science and Technology (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, CONACyT) operates a system to accredit postgraduate programmes through the National Programme of Quality Postgraduate Studies (Programa Nacional de Posgrados de Calidad, PNPC). The accreditation of programmes encompasses face-to-face programmes with a professional orientation, as well as those with research orientation, programmes with industry, programmes for medical specialisations, and distance and blended programmes. The methodology implemented in the accreditation process is based in 25 years of evolution and continuous improvement.

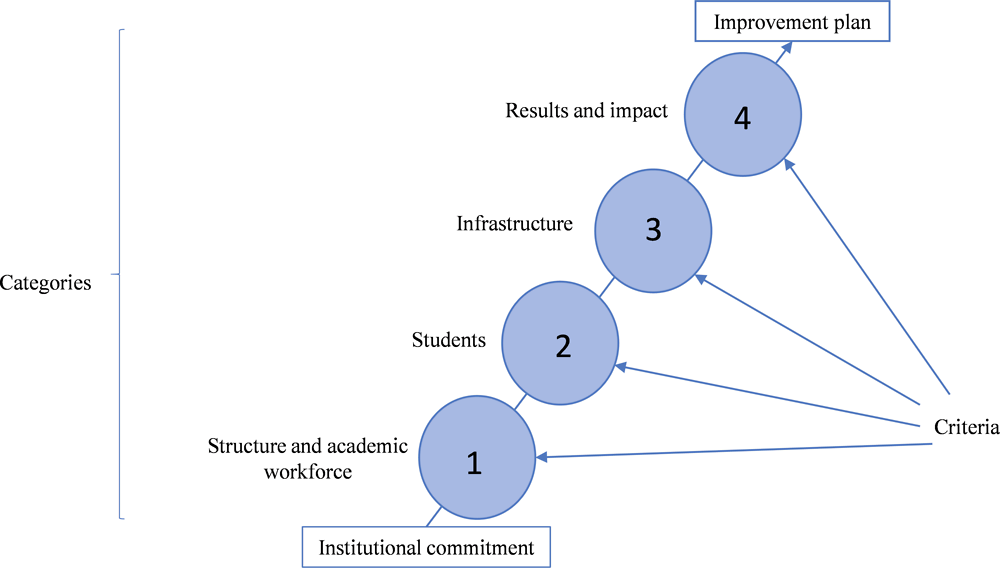

The evaluation process follows a sequence of self-evaluation (ex-ante evaluation); peer evaluation (external evaluation), and assessment of results and impact (ex-post evaluation), by the National Graduate Council (Consejo Nacional de Posgrado). The evaluation focuses on four areas of quality represented in Figure 4.1: the programme structure and academic workforce, the student experience, the programme infrastructure, and the research results and external impact of the programme. Programmes are required to have in place a continuous improvement plan.

Figure 4.1. Elements of the CONACyT Evaluation Model

The National Graduate Council recognises four levels of programme quality: international level; well-developed (consolidado); developing; and recently established, and in recent years about four in ten programmes that have undergone review have been judged to be at first two levels (SEP, 2015[14]).

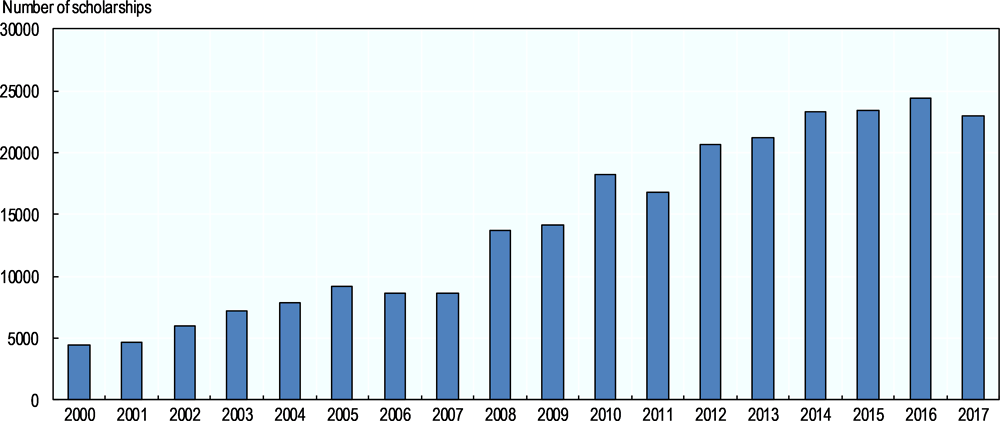

In 2018, about one in four (23.5%) postgraduate programmes in Mexico were recognised by CONACyT to be a quality programme (2 297 out of 9 737 postgraduate programmes). Most (66%) these programmes were in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM), while the remaining 34% were in Social Science, Humanities, and Arts. Completion of CONACyT accreditation permits researchers and their institutions to receive CONACyT grants for the projects they submit, and students on the programmes to receive CONACyT fellowships (SEP, 2018[15]). CONACyT awards over 20 000 new scholarships for postgraduate students in PNPC programmes directly each year (Gobierno de la República, 2018[16]).

Figure 4.2. New CONACyT scholarships for postgraduate students, 2000-2017

4.3. Strengths and challenges of the current systems for external quality assurance

4.3.1. SEP has undertaken reforms aimed at simplifying and updating the RVOE process for private providers, but shortcomings remain

In November 2017, SEP adopted a redesign of the RVOE process that aimed, among other things, to close loopholes in the existing procedures, to accommodate the growing importance of distance education, and to modernise, accelerate and streamline the RVOE administrative procedures.

SEP has also attempted to increase participation in the RVOE process by making administrative procedures less burdensome to applicants. Agreement 17/11/17, adopted in November 2017, aims to (a) streamline the RVOE process to make it less difficult for private institutions operating programmes without a RVOE to undertake, thus raising the proportion of programmes with a RVOE and (b) ensure that RVOE standards support educational innovation, and “the capacity and employability of graduates” (SEP, 2017[6])

Streamlining was accomplished by the introduction of an Institutional Improvement Programme that established three categories of institutions: those in the process of accreditation, recently accredited institutions, and institutions with well-established (consolidado) accreditation. Institutions in each category receive a different level of administrative simplification commensurate with their accreditation status.

Responding to the growing importance of distance education, SEP also put forward for the first time programmatic guidelines with respect to online and hybrid programmes. Among these requirements is a description of the theoretical and pedagogical model the programme plans follow; learning strategies, teaching materials and resources, and processes for evaluating learning outcomes; the technology platform to be used, both software and hardware; and plans for continuity of service and the protection of personal information.

Nonetheless, the process provides little guarantee that minimum levels of educational quality are achieved by all private higher education institutions. A proportion of institutions is likely to continue to operate without RVOEs. The requirements of the RVOE process with respect to key educational inputs are focused heavily on educational plans and materials, and permissive with respect to instructional resources. There is little assurance that the programme plans approved are implemented with fidelity, owing to weak processes of monitoring and infrequent enforcement.

Participation in the RVOE process is likely to remain incomplete

The registration of private higher education programmes through the RVOE process is not strictly compulsory: private institutions may establish programmes and enrol students without obtaining Ministerial recognition of their programmes as part of the national system of education. An unknown number of programmes in private institutions operate in this way.

Some private institutions do not comply with regulations, and offer programmes without indicating - as the law requires - that their programmes lack “the recognition of official validity.” Other institutions, stakeholders averred when meeting with the OECD Review Team, may mislead prospective students by falsely reporting that recognition of their programmes is pending, although this practice is explicitly prohibited by Article 43 of Agreement 17/11/17. (SEP, 2017[6])

Private higher education institutions acknowledge that revisions to the RVOE procedures promise to simplify administrative processes. However, representatives of higher education associations do not expect the revised procedures to have a significant impact on the quality of provision. Private institutions with few resources and little reputation to safeguard are expected to remain weakly motivated to embark upon registration to obtain RVOEs. Their decision to forego recognition results, in part, from the functioning of Mexican labour markets. Many young higher education graduates are self-employed (10%) or work in informal jobs (25%), and many work in jobs that do not require a higher education (46%) (OECD, 2019[17]). For these students the absence of a cédula profesional or titulado profesional that comes from a registered programme may not adversely affect their employment prospects or earnings.

Permissive input requirements create a risk of poor educational quality

The RVOE process focuses heavily upon the review and approval of programmes as intended, rather than the programmes as implemented or delivered. Institutions submit a study plan (plan de estudio), a proposed curricular map (mapa curricular), evidence with respect to the infrastructure of provision, and a statement indicating the suitability of staff qualifications and experience to the proposed programme of study.

Among the inputs thought to be prerequisites of quality education – infrastructure that is fit for purpose, carefully designed study plans and well-chosen materials, and skilful instructors – the last of these, instructors, are often believed to be the most important factor in student learning (Strang et al., 2016[18]). Because the quality of instructors is not directly observable, quality assurance systems typically set policies with respect to proxies that can be observed and measured: the number, contractual status, educational qualifications, and specialisation of instructors associated with a programme (Strang et al., 2016[18]).

In the design of quality assurance systems, higher education institutions with a record of effective performance and demonstrated capacity for the management of quality are typically authorised to exercise independent judgment with respect to questions of staffing, while institutions that lack this record of performance and evidence of capacity are not. In contrast, Article 7 of the 17/11/17 Agreement, permits private institutions of all types of private institutions to determine the staff profile fitted to the proposed programme:

It is the responsibility of the institution to ensure the profile of its academic staff is suitable for the delivery of its plans and study programs, gathering staff with sufficient academic background, knowledge, skills and experience necessary for the development of teaching activities, learning, evaluations and other academic activities under their charge. The institution will determine the profile of instructors, and may demonstrate they have the necessary preparation, whether self-educated or through experience, of at least five years in teaching, work or professional field. (SEP, 2017[6])

Monitoring and enforcement are not robust

Well-developed ex-post monitoring and enforcement can mitigate the risk of poor quality that results from insufficient ex-ante requirements. However, the RVOE process lacks these capacities. Programmes holding a RVOE are not subject to planned compliance inspections. Authorities do not have information systems that permit them to monitor the performance of recognised programmes against a dashboard of indicators that might signal quality problems, such as poor job placement rates or cohort-based graduation rates. Rather, authorities act in response to news reports or complaints from students and local officials about anomalies in the functioning of higher education institutions or one of its academic programmes. Some participants in stakeholder meetings with the OECD review team expressed concerns that state officials have very limited administrative capacities to respond to complaints, and that there were also risks of non-enforcement arising from corruption. SEP authorities responsible for the federal RVOE process indicate that follow-up monitoring may result in prescriptions for corrective actions. Sanctions however, are rare. In 2017, more than 20 000 programmes operated with a RVOE, two of which were withdrawn.

4.3.2. Sound processes for external programme accreditation and evaluation exist, but they remain voluntary and are not appropriate for all sectors of higher education

Established external accreditation and evaluation processes and an institutional commitment to quality in some universities.

Mexico has developed stable and mature processes for quality assurance of undergraduate education. As described above, these processes are managed and guided by independent, fee-based, non-profit organisations – CIEES and COPAES - that are independent of government, that operate following established and well documented procedures, drawing upon a range of scholars to participate in their peer review processes, and produce results that are generally trusted within the higher education community.

External quality evaluation and accreditation is a voluntary activity on the part of Mexican higher education institutions, participation in which requires a significant investment of money (fees) and staff time. Academic and administrators with whom the OECD review team met identified a range of incentives that lead them to participate in quality assurance, notwithstanding these costs. For public universities subject to annual federal budget negotiations, institutional representatives argued that participation in quality assurance “is used in our favour” and provides an increment of additional public spending. For private institutions with moderate or high fees, accreditation is a useful quality signal to prospective students and their families that supports their pricing model. For other institutions, especially those whose graduates enter formal jobs that require higher education skills, external quality assurance provides evidence of graduate quality that assists programmes in securing employer engagement and labour market success for their graduates.

For the federal authorities, expanding the participation of public universities in external processes of accreditation and evaluation has long been a key policy commitment. For nearly two decades, SEP programmes have aimed to improve the quality of public higher education institutions by linking institutional planning processes, institutional self-evaluation and accreditation. These began in 2001 with the Integrated Programme for Institutional Strengthening (Programa Integral de Fortalecimiento Institucional PIFI). Over time, the programme has evolved and been periodically redesigned and renamed, and now operates as the Programa de Fortalecimiento de la Calidad Educativa or PFCE. These programmes have had an impact on public higher education institutions, increasing the number of accredited undergraduate and graduate programmes, promoting doctorate level training of academics, increasing their research output, incorporating new forms of academic planning and management defined in institutional development plans, and in many cases exercising genuinely participatory processes (Ibarra Colado, 2009[19]).

As discussed in the previous chapter, widening participation in quality assurance and programme evaluation was adopted as a goal in the 2013-2018 Sectoral Education Programme. Progress is monitored and publicised by the SEP through its web-based National Census of Quality Education Programmes (Padrón Nacional de Programas Educativos de Calidad) (SEP, 2018[10]); and remains a focus of made the focus of targeted public investment in institutions through the Programme to Strengthen Higher Education Quality (PCFE). In 2018, public higher education institutions received MXN 1.86 million to “improve the quality of educational programmes and achieve accreditation.” Fees for programme accreditation or evaluation range from approximately EUR 3 200 to EUR 6 200 per programme, and public higher education institutions do not recover their investment in quality by charging higher tuition fees when programmes are quality assured. This programme has therefore been helpful in aiding public higher education institutions meet the outlays associated with accreditation.

SEP and the Coordinating Commission of Evaluation and Higher Education Bodies (COCOEES) agreed in 2018 to “a new paradigm for evaluation and accreditation of higher education programmes,” in which the National Centre for Higher Education Evaluation (CENEVAL) will also recognise quality programmes, through its Census of High Performance programmes (Padrón de Alto Rendimiento) (SEP, 2018[20]). Under CENEVAL procedures, programmes enter its Census if a sufficient percentage of students exiting a programme achieve satisfactory or outstanding scores on the standardised Exámenes Generales para el Egreso de Licenciatura (EGEL).

This set of initiatives has been, in important respects, a success. Just under half of undergraduate students are now enrolled in programmes for which the quality has been assured by CIEES or a COPAES-recognised body.

The growing number of accredited and evaluated programmes is having a positive impact on the culture of evaluation and quality in some higher education institutions, fostering the development of specialised offices to provide data and training for administrators and faculty members to perform self-evaluation of their programmes.

International engagement on questions of learning and quality is emerging. Some institutions, such as the University of Guadalajara, demonstrate a commitment to quality through their participation in international initiatives on learning assessment, such as the OECD AHELO project and the work of CLA+. Others participate in quality assurance processes outside of Mexico, like the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS), a US regional accreditation body. Foreign peers, though rarely used in the accreditation of undergraduate programmes, are used in some areas of postgraduate study. Some COPAES accrediting bodies (CAEI, ANPADEH, CONAIC and CONEVET) are members of international networks that group accrediting agencies from different countries in their disciplines. These experiences have influenced the definition of evaluation criteria and standards, and the incorporation of international good practices in quality assurance processes.

However, there are critical shortcomings with respect to the assurance of quality: its coverage remains incomplete; it can be poorly adapted to vocationally oriented education and the demands of working life, or to distance education; and it provides no procedures for institutions to demonstrate their fitness to manage the quality of their programmes.

But the coverage of external evaluation and accreditation is incomplete, particularly in the private and professionally oriented public sectors

In the private sector, just under two in ten students study in programmes that have been externally accredited or evaluated. These are likely to be students from comparatively affluent households enrolled in selective and well-financed institutions, while the risk of seriously deficient provision is borne by low-income students enrolled in poorly resourced private institutions.

Many private institutions compete in a segment of the higher education market in which students from low-income households are attracted by low prices and convenient provision. The system of licensing (RVOE) is the only process of external review with an orientation to quality in which low-price programmes in private institutions will normally participate – and, even then, not in all cases. However, in design and implementation, the RVOE process is not yet sufficient to achieve minimal standards of provision. Fee-based accreditation and external quality assurance are not economically feasible for them, since they are unable to recover their investment in quality by charging higher prices for quality assured programmes.

While the federal government has made large, long-term efforts to reward public higher education for participation in external evaluation and accreditation, it has not done so for private higher education institutions. They are not eligible to participate in competitive funding schemes, such as the PFCE. Only Sistema Nacional de Investigadores (SNI) funding and CONACyT funding for postgraduate study and research through PNPC are accessible to private institutions, and few private institutions benefit (Gobierno de la República, 2014[21]). For example, out of more than 2 500 private higher education institutions in Mexico, 17 receive CONACyT funding through PNPC.

Among public sector higher education institutions, there is wide variation in the frequency of quality assurance, with low levels of participation among institutions for whom existing quality assurance arrangements may be maladapted, particularly in the professionally and technologically oriented subsystems.

Poor adaptation to the needs of certain institutional types and modes of provision, coupled with limited institutional capabilities

Some sectors of public higher education have very low rates of participation in external evaluation, including Intercultural Universities and public Teacher Education Colleges (educación normal). Public Teacher Education Colleges are typically exceptionally small institutions, with 70% containing 250 or fewer students. Consequently, they lack the qualified human resources necessary to perform self-evaluation processes. Moreover, existing accreditation agencies do not have fully adequate criteria and procedures to evaluate educational programmes provided by Intercultural Universities adequately, given the special characteristics of the education provided.

The largest number of students who study in programmes without quality assurance attend Technological Universities and Institutes of Technology. For these sectors, both institutional capacity to manage the burden of participation and the maladaptation of quality assurance standards designed for university programmes may pose obstacles to further use of quality assurance. Staff in Institutes of Technology stressed the second of these concerns with the OECD Review Team, noting that some of accreditation bodies set standards poorly adapted to the structure and content of their programmes.

While State Public Universities have very high rates of enrolment in quality assured programmes (90%), federal universities have a significantly lower rate (72%), with about 115 000 federal university students enrolled in programmes without an external assurance of quality. At the National Pedagogical University (UPN) 80% are - a share below the average level of state institutions - while at UNAM one-third of students (33.1%) of students study in programmes that are not externally evaluated or accredited. Institutional capacity and alignment of criteria to programmes are unlikely to be major obstacles to participation by federal universities, though concerns about the benefit of external accreditation or quality assurance might be.

Table 4.2. Enrolment in programmes designated as “good quality”, by sector (August 2018)

|

Subsystem |

Enrolment in “quality” programmes |

Enrolment in evaluable programmes* |

Total enrolment |

% coverage (“quality” programmes) |

% coverage (evaluable programmes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

State Public Universities |

956 660 |

1 062 650 |

1 144 944 |

83.56% |

90.03% |

|

State Public Universities with Solidarity Support |

22 913 |

44 562 |

60 433 |

37.91% |

51.42% |

|

Polytechnic Universities |

34 004 |

83 934 |

96 442 |

35.26% |

40.51% |

|

Intercultural Universities |

789 |

11 300 |

13 784 |

5.72% |

6.98% |

|

Federal public universities |

294 554 |

409 443 |

432 569 |

68.09% |

71.94% |

|

Technological Universities |

94 529 |

163 721 |

245 154 |

38.56% |

57.74% |

|

Institutes of Technology |

299 153 |

551 054 |

591 989 |

50.53% |

54.29% |

|

Other public higher education institutions (HEIs) |

6 975 |

84 161 |

114 270 |

6.10% |

8.29% |

|

Professional HEIs of education |

435 |

26 922 |

37 194 |

1.17% |

1.62% |

|

Public normal schools |

13 715 |

68 108 |

77 033 |

17.80% |

20.14% |

|

Private institutions |

209 698 |

1 111 886 |

1 396 048 |

15.02% |

18.86% |

|

Total |

1 933 425 |

3 617 741 |

4 209 860 |

45.93% |

53.44% |

Source: SEP, Corte de Calidad del mes de agosto 2018, Tab 10. Evaluable programmes: those with one or more cohorts of exiting students in programmes not established in the period 2013-2017.

Distance education has presented a special challenge to Mexico’s policies of registration and external quality assurance, one that affects both public and private sectors in Mexican higher education. While a total 1.9 million students study in quality assured undergraduate programmes, representing over half of all undergraduate students, only 46 000 study in quality distance education programmes, representing only about 17.5% of all undergraduates enrolled in distance education programmes (DGESU, 2018[22]).

The public and private bodies responsible for evaluation, accreditation, and registration have been slow to develop processes tailored to distance and hybrid (blended) programmes. Their policies have lagged behind the growth of distance education enrolments, and in some instances impeded participation in external accreditation. CIEES has responded most swiftly to the challenge of distance and hybrid programmes, carrying out its first evaluation of a distance programme in 2006. In 2014, CIESS established a common methodology for quality evaluation of distance and hybrid programmes, and by 2015, it had awarded 22 distance programmes and 12 hybrid programmes a Level 1 rating – among the 1 156 programmes it had awarded this distinction in total.

COPAES has responded slowly to the challenge of distance education, and in the view those seeking accreditation for distance education programmes, the accreditors that it recognises have created an uneven and sometimes contradictory accreditation processes:

Each [COPAES-recognised accrediting] organisation has its own instrument, which is similar [to the ones used by other organisations], but not the same. There is a lack of a common reference framework for the accreditation of distance programmes and each [accrediting] organisation has adopted distinct criteria, with radically opposed positions, ranging from organisations that will evaluate virtual programmes without a specific instrument, but offer flexibility to use alternative equivalent criteria aligned to the mode [of provision], to organisations with a developed instrument for distance education that refuse to conduct evaluations because they are awaiting approval from COPAES (Navarro Navarro and Gómez Hernández, 2017[23]).

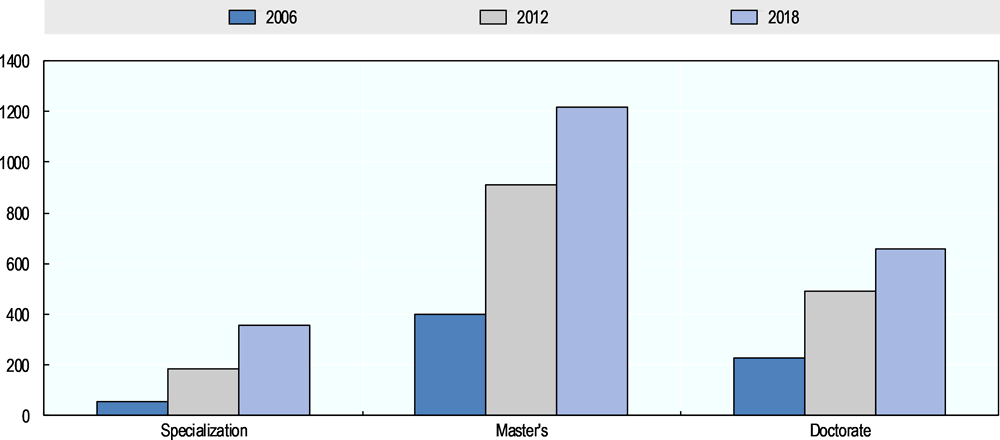

At postgraduate level, CONACyT has established an especially well conceived evaluation process, the scale of which has expanded substantially over the past decade, with the total number of accredited programmes increasing from 859 in 2 007 to 2 207 in 2017. Programmes below the doctoral level (specialisation programmes and master’s degrees) comprise about 70 percent of the total number of accredited programme (SEP, 2018[15]).

Figure 4.3. Number of postgraduate programmes in the PNPC, 2006, 2012 and 2018

The recognition of postgraduate programme quality by CONACyT is not designed to be a comprehensive system for the accreditation of all postgraduate programmes in Mexico. Rather, its evaluation of postgraduate programmes is a means to an end: to ensure that public monies invested in research and postgraduate training are well spent. The number and type of accredited programmes is guided by the availability of resources to finance scholarships for students, and it is possible that there will be quality postgraduate programmes that are not accredited by CONACyT, as they are outside its areas of investment priority.

While Mexico had 9 737 postgraduate programmes (specialisation, master’s degrees and doctorates) offered by higher education institutions and research centres, only 2 054 (21%) were recognised “programmes of quality” as part of CONACyT’s National Programme of Quality Postgraduate Education (PNPC) as of January 2018. Of the 334 109 postgraduate students enrolled, just under one in four (23.4%) were enrolled in a programme registered in the PNPC (Table 4.3).

Table 4.3. Enrolment in postgraduate programmes with quality recognition, 2018

|

Active institutions, postgraduate |

Institutions with quality programmes* |

Postgraduate enrolment |

Enrolment in quality programmes* |

Postgraduate programmes |

Quality programmes* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Subsystem |

a |

b |

c = b/a (%) |

d |

e |

f = e/d (%) |

g |

h |

i = h/g (%) |

|

Federal public universities |

7 |

6 |

85.7 |

43 051 |

33 030 |

76.7 |

545 |

320 |

58.7 |

|

State Public Universities |

34 |

34 |

100.0 |

54 723 |

29 431 |

53.8 |

2 091 |

1 183 |

56.6 |

|

State Public Universities with Solidarity Support |

16 |

8 |

50.0 |

1 248 |

440 |

35.3 |

104 |

36 |

34.6 |

|

Intercultural Universities |

2 |

0 |

0.0 |

73 |

0 |

0.0 |

8 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Technological Universities |

1 |

0 |

0.0 |

20 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Polytechnic Universities |

16 |

6 |

37.5 |

1 151 |

119 |

17.3 |

45 |

13 |

28.9 |

|

Federal Institutes of Technology |

60 |

42 |

70.0 |

3 701 |

2 585 |

69.8 |

171 |

98 |

57.3 |

|

Decentralised Institutes of Technology |

19 |

6 |

31.6 |

897 |

322 |

35.9 |

39 |

9 |

23.1 |

|

CONACyT Research Centres |

24 |

24 |

100.0 |

4 161 |

3 665 |

88.1 |

147 |

124 |

84.4 |

|

Public normal schools |

33 |

0 |

0.0 |

3 108 |

0 |

0 |

71 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Other public HEIs |

145 |

14 |

9.7 |

28 145 |

4 830 |

17.2 |

719 |

145 |

20.2 |

|

Public HEIs (total) |

357 |

140 |

39.2 |

140 278 |

74 502 |

53.1 |

3 941 |

1 928 |

48.9 |

|

Private HEIs |

1 041 |

17 |

1.6 |

193 831 |

3 816 |

2 |

5 796 |

126 |

2.2 |

|

Total |

1 398 |

157 |

11.2 |

334 109 |

78 318 |

2.4 |

9 737 |

2 054 |

21.1 |

Note: *Programs listed in the PNPC of CONACyT in January 2018 in any of its four levels: recent creation, in development, “consolidated” and international competency.

Source: Adapted from (ANUIES, 2018[24]) Visión y acción 2030.

Doctoral programmes in science and technology more often obtain CONACyT recognition for quality than those in other areas of study, and the Sectoral Education Programme set for the agency the goal of increasing the proportion of science and technology doctoral programmes gaining PNPC recognition from 63.5% in 2012 to 71.6% in 2018 (SEP, 2013[25]). Moreover, PNPC programmes are heavily concentrated in a comparatively small number of higher education institutions, principally in the nation’s federal and state public universities. About three in four (73%) of quality postgraduate programmes are located either in a federal or state university.

4.3.3. Quality assurance policies have focused on programmes and not supported the development of institutional capabilities and responsibilities with respect to quality.

Education programmes within higher education institutions – rather than institutions themselves - have been the focus of public policies with respect to quality assurance, including external evaluation, accreditation, and registration. Institutional accreditation has been limited to the reviews that FIMPES performs as part of its admission process to the organisation, and institutional evaluations are limited to the examination of management and extension functions that CIEES undertakes as part of its external evaluation of universities.

The absence of institutional accreditation has important implications for higher education in Mexico. In the private sector, although some private institutions have strong and consistent records of achievement in providing educational programmes of high quality, they have no option by which they may exit the RVOE process and take institutional responsibility for the quality of their programmes. While they welcome processes of administrative simplification for the RVOE process, they are displeased at being obligated to comply with a registration and reporting regime from which public institutions are exempt, and disappointed that the new procedures do not offer them the opportunity to autonomously design new academic programmes, modify programmes, or create new campuses.

In the public sector, institutions wishing to demonstrate the quality of their educational processes only have the option to seek external evaluation and accreditation on a programme-by-programme basis. This situation contrasts with that in most other OECD countries, where external accreditation and quality assurance processes typically include institution-wide evaluations. In a number of such systems, public institutions with a demonstrated record of quality provision may self-accredit their own programmes, with the prerequisite that they have rigorous internal quality procedures in place. This is the pattern in most English-speaking countries and the basis of systems in Nordic countries. In other cases, such as the Netherlands, institutions with a strong performance in internal quality assurance are eligible for “lighter touch” programme-level accreditation.

Programmatic autonomy, or self-accrediting status, requires that higher education institutions participate in a rigorous institutional evaluation process that permits them to demonstrate regularly that they have the capacity to take responsibility for the quality of their programmes, and a process that is public and accessible to all institutions, fully independent of the membership process for a private association. This feature is missing from the policy landscape of higher education in Mexico.

4.4. Key recommendations

Mexico is a large, diverse, and socially stratified nation, and it has a higher education system to match. This presents government with very different quality challenges and opportunities at the “top”, “middle”, and “lower end” of the system – among its universities of global or national standing, a strong and effective “middle” of public and some private universities and institutions, and its small and poorly resourced private and public institutions.

To address these challenges effectively Mexico will need a quality assurance system that is more comprehensive than at present. This has been a focus on policy, and should continue to be in future. However, equally important, Mexico needs a quality assurance system that is much more differentiated – both vertically, and horizontally - to accommodate different types of institutions with different missions. Lastly, it needs a quality assurance system that is better coordinated. Coordination does not mean the establishment of a coordinating body in which stakeholders meet. Rather, a coordinated system of quality assurance is one in which the component parts – registration or licensing, programme accreditation, and institutional accreditation – work together in a coordinated way, permitting institutions to take as much responsibility for quality as their own capacities permit and the system to collectively raise the quality of teaching and learning in its undergraduate and postgraduate programmes.

4.4.1. Promote further quality improvements in strong institutions by increasing institutional responsibility for programme quality

A decade ago, few public higher education institutions in Mexico had carried out an external review of all or many study programmes they offered. Today, many have. Among Mexico’s 34 state universities, 32 have more than 75% of students studying in programmes that have participated in external quality assurance - 21 of which have more than 9 out of 10 students in “quality programmes.” In the private sector, another 42 higher education institutions have achieved 75% of enrolments in quality programmes – with 27 surpassing 90%. In total, 229 higher education institutions enrol more than 75% of their students in quality assured undergraduate programmes.

Across the world, and within the OECD, systems of higher education quality assurance that began with comprehensive programmatic quality assurance procedures have often shifted their focus to the development of institutional accreditation procedures. In these systems, institutions that have successfully demonstrated the quality of their programmes - and proven that their institution has the capacity to take responsibility for the quality of their study programmes through a process of institutional accreditation – are permitted to assume responsibility for the quality of their programme offerings, subject to a continuing and periodic renewal of this self-accrediting status. (Lemaitre and Zenteno, 2012[26]). For Mexican higher education institutions like the Universidad Autónoma De Nuevo León and the Universidad La Salle – in which all undergraduate students are enrolled in quality assured programmes - there is no opportunity to transition from an exclusively programme-focused to institution-level process of quality assurance.

The rationale for providing a pathway from programmatic to institutional accreditation is threefold:

Lower Costs/Improved Efficiency. Large higher education institutions manage scores of programmes, and find it very costly to manage fee-based participation in programmatic accreditation for each of their degree programmes. Institutional accreditation makes it possible to achieve efficiencies by combining reviews of adjacent study programmes (e.g. political science and public administration) or vertically integrated (bachelor’s and master’s degrees in nursing). Moreover, information and data related with different programmes and departments are usually processed by offices that operate at the central levels of the organisations. Implementing institutional evaluation lessens costs and increases consistency in the cases of institutions that systematically present their programmes to accreditation processes.

Improved Learning. Institutions that have participated in repeated cycles of programme evaluation or accreditation point to diminishing benefits that result from repetition of the accreditation process. As one institutional leader observed in our meetings, “With repetition we stop learning. We know the path to approval.” Institutional evaluation can also produce information and strengthen internal quality assurance practices that are difficult to evaluate through specialised reviews of academic programmes. An important set of criteria for accreditation of the programmes, in fact, aims at evaluating the common institutional context of those programmes.

Linking Quality to Institutional Strategy. Fixing responsibility for quality at the level of the university and having it undergo accreditation provides them with an external view of how they are functioning, and helps them to link questions of quality to institutional governance, management, and resource allocation. (Cifuentes-Madrid, Landoni Couture and Llinas-Audet, 2015[27]).

Mexico presently has a process for higher education institutional review organised by FIMPES, the purpose of which is to authorise accession to its membership. Mexico needs a new and separate process for institutional accreditation that is different to this private and organisational process.

Institutional review leading to self-accrediting status could be opened to any public or private institution in which all programmes had successfully undergone external review (accreditation or evaluation) for more than one cycle. It would focus in a comprehensive way on the capacity of institutions to monitor and improve the quality of their educational programmes.

Mexico could benefit from the experience of the European Higher Education Area, and require higher education institutions to have policies for quality assurance. European Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Higher Education set general standards and guidelines in areas that are important for successful quality provision in higher education to guide the work of institutions, quality assurance agencies and governments. The standards and guidelines for learning and teaching in higher education institutions include a policy for quality assurance; the design and approval of programmes; student-centred learning, teaching and assessment; student admission, progression, recognition and certification; teaching staff; learning resources and student support; information management; public information; ongoing monitoring and the periodic review of programmes; and cyclical external quality assurance (ENQA, 2015).

The process of external institutional review could be organised by a body that is independent of government and higher education institutions, and employ differentiated criteria to take account of the varying missions of higher education institutions. It would award approved institutions self-accrediting status for fixed duration, and monitor their performance on a continuing basis.

Federal policymakers should consider whether a process of institutional review might best be developed drawing upon the processes and capabilities of CIEES. CIEES currently evaluates university functions including administrative and financial management, and infrastructure and services, and it has recently developed optional evaluation modules focusing on research management, innovation, outreach, internationalisation, and management of the dissemination of culture and science (CIEES, 2017[28]).

4.4.2. Expand external quality assurance in other higher education institutions, including through processes better tailored to professional programmes

Many higher education institutions in Mexico have begun to engage in the practice of external quality assurance, but have had limited experience with it. In these institutions, half or fewer of their students are studying in “quality” programmes, or the institution has only recent, but not recurring experience of programme-level of quality assurance. Some of these operate in Mexico’s public sector of higher education, with examples including Technological Universities (UTs) and Institutes of Technology (ITs). Many others are part of Mexico’s private sector of institutions.

The focus of public policy for this large, intermediate set of institutions should be to twofold. First, government should aim to expand participation in external programme-level review. The important support provided by Programa de Fortalecimiento de la Calidad Educativa (PCFE) should be continued, potentially at past levels. However, as leading public universities transition to institutional accreditation, government should target these funds at those parts of the public sector in which participation in quality assurance has been lagging.

Second, government policy should focus on supporting the development of suitable diversity in quality assurance, so accreditors and evaluators define and measure quality in ways that are consistent with the missions of all types of institution.

For example, a process of quality assurance for research-led universities might appropriately expect instructors to hold PhD degrees and for many to work with permanent and full-time contracts and hold exclusive employment with their university institution. This model is neither affordable nor suited to private institutions that provide high-quality education programmes in law or business, nor is it suitable to public institutions such as Institutes of Technology. For institutions that are not research-led universities, an accreditation process that is suitably adapted to institutional missions would evaluate the instructional workforce by focusing on the durability and quality of the relationship between instructors and students. Indicators of sufficient durability and quality might include (among others) the continuity of the teaching workforce, the availability of the instructors to mentor and advise students, the institution’s investment in the continued professional development of its instructors, the institution’s willingness to evaluate and properly reward excellent teaching, and the link between the instructor’s professional accomplishments and teaching responsibilities.

Diversifying quality assurance to take proper account of the missions and instructional practices of technical and professionally oriented higher education institutions is a challenge in higher education systems across the world, within the OECD, and, stakeholders indicated, in Mexico as well.

Well-functioning higher education institutions with a professional and technical focus – whether in France, Netherlands, or Portugal – differ from research universities in their curriculum, staff, pedagogy, and the external stakeholders with which they engage. Quality assurance processes need to take these differences into account in developing evaluation criteria, in assessing learning outcomes, and in looking for labour market outcomes of graduates.

Likewise, quality assurance needs to be adapted to the mode of provision, with attention to the particular risks and needs of programmes delivered in whole or in large part through distance education. According to stakeholders with whom the review team met, CIEES has most effectively performed this work to date, and the processes it has established should be continued.

Quality assurance in Mexico needs significantly greater attention to labour market outcomes and stronger input with respect to the key skills that graduates need, including from private firms, public agencies, professional associations, and non-profit organisations – than at present. This is most especially true for technically oriented institutions.

Federal policymakers can help support the development of both capacities by providing targeted funding to evaluation and accreditation bodies to develop and implement a more diversified set of evaluation and accreditation instruments and processes.

4.4.3. Raising the bar – ensure better protection for students by enforcing minimum quality standards in the private sector more rigorously

Ensuring that every student has a higher education that meets minimum standards of quality – and therefore prepares them for a lifetime of engaged citizenship and productive employment – remains a policy goal that has not been fully achieved.

Mexico should prioritise reform of the licensing system, the RVOE, so that it provides an effective guarantee basic quality in the private sector. The reform of RVOE would benefit from a new legal basis. Borrowing from the experience of other higher education systems in the region (and across the OECD), Mexico could consider a compulsory registration process in which private institutions must obtain permission to operate – to enrol students - from the federal government. Here Mexico might look, for example, to the model of Brazil, which has a vast system of private higher education. In this system, every private higher education institution is part of the Federal system of education, and is required to obtain formal external accreditation (credenciamento) from federal authorities to begin operation, and to participate in a periodic process of recredenciamento to continue operations.

Like registration and recognition arrangements through the region and across the OECD, the aim of the recognition process must be modest and realistic: to ensure an acceptable minimum level of provision through a process of inspection that focuses on educational inputs and processes for new institutions and programmes, and extending to outputs for programmes seeking re-accreditation. The process would pay attention both to institutional features and maintain a requirement for all programmes to be licensed separately.

Where governments aim to protect students by ensuring a common minimum level of provision, there is no rationale for criteria and processes to differ from one sub-national jurisdiction to another. Thus, for example, the accreditation process in Brazil is the responsibility of federal authorities, and uniform across its states. Mexico would benefit from a similar consistency in policy across its federal system, aiming to ensure that students can expect a common minimum, whether they study in Baja California or Chiapas.

A reformed system would benefit from improved monitoring and enforcement capabilities. Permission to operate should be accompanied by a requirement that institutions provide federal authorities with a minimum data set that supports ongoing monitoring and enforcement, diminishing their exclusive reliance on complaints as the basis for intervention. Clear and effective sanctions for non-compliance with RVOE conditions should be introduced.

Mexican authorities should build upon the work begun with 17/11/17 Agreement, moving forward to develop a fuller framework for the categorisation of private institutions. This framework should take into account the progress that institutions make in accrediting their programmes. The process should provide a graduated pathway permitting institutions progressively wider responsibility in developing new study programmes or modifying study plans.

These changes should be part of a strategic rethinking about the role of the private sector within the nation’s higher education system, and of the relationship between public authorities and private institutions. Apart from support at the postgraduate level - for a small number of institutions - federal programmes do not fund students and activities in private higher education institutions. As we have indicated in Chapter 5, Mexico should consider extending eligibility to award maintenance grants to private institutions – if students who study in SEP-recognised quality programmes, and if these programmes are based within higher education institutions that have a well-demonstrated capacity for sound financial management. This would assist Mexico in achieving quality expansion, fairer treatment of disadvantaged students who enrolled in public and private institutions, and provide an inducement for private institutions to expand their participation in external quality assurance.

4.4.4. Widen coverage of external quality assurance for postgraduate education

CONACyT has an important role to play in developing the national research capacity of Mexico, most especially in fields that are critical to the development of the nation’s economy, including life sciences, exact sciences, technology, and engineering. However, its assessment of postgraduate study programmes through the PNPC is not entirely aligned to this mission, since PNPC focuses more heavily on specialisation and master’s programmes than PhD programmes, which comprise only 28.5% of all PNPC programmes.

In the decade ahead, higher education institutions will gain experience in monitoring and improving quality, and accreditation and evaluation bodies operating at undergraduate level gain further experience in supporting HEIs. As they do, they should be able to take responsibility for professionally oriented postgraduate education (at the specialisation and master’s degree levels), thereby permitting CONACyT to focus its attention on the training of PhDs, as is often the case in other systems of quality assurance (such as Brazil or many European countries).

Mexico’s PhD students in quality assured programmes should be trained at an international level, and to ensure that this level is met the evaluation of programmes should consistently engage international researchers. International experience demonstrates that it is a good practice for quality assurance systems to incorporate international academics: this grants a higher degree of impartiality to evaluations in specialised fields that contain few national experts, and introduces beneficial learning from other university systems. (Gacel-Ávila and Rodríguez-Rodríguez, 2018[29]).

The link between CONACyT funding and quality assurance should continue, with the award of postgraduate study scholarships made dependent on students studying on a quality assured programme.

4.4.5. Adapt institutional arrangements for external quality assurance to implement the preceding recommendations

What institutional arrangements are best suited to take forward these quality policies? It is the view of the OECD review team that Mexico should establish a quality assurance body to guide the work of quality assurance for undergraduate and postgraduate professional education, while continuing to rely upon CONACyT to organise quality assurance in doctoral education.

To be trusted, impartial, and stable the body must be independent of both higher education institutions and government. Given the success that non-profit, non-governmental bodies have had in taking forward the work of quality assurance – such as COPAES, CIEES, and CENEVAL – it is advisable that a quality assurance body take this form. International experience offers models of special legal forms that provide quality assurance bodies with a very high degree of autonomy, such as Portugal’s Agency for Assessment and Accreditation of Higher Education (A3ES). However, national policy makers must adapt international experience to local legal forms.

In the near-term, targeted public funding would be necessary to develop properly the capacities of the quality assurance organisation, while on a long-term basis the organisation would best achieve independence by operating on a fee basis.

The organisation would be responsible for:

Taking a strategic view of the relationship between quality in undergraduate and postgraduate education.

Ensuring that quality is being properly cared for across the entire system of higher education: by institutions that are self-accrediting; by institutions that are gaining increasing experience of external programme-level review; and by institutions that operate within a reformed system of institutional registration or licensing (RVOE).

Advising the Secretary for Public Education which bodies should be recognised to perform the work of evaluation, assessment, and accreditation of higher education institutions and programmes.

Setting the conditions that institutions need to achieve to become self-accrediting (as, for example, the Australian Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency does in Risk Assessment Framework) (Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency, 2017[30]).

Ensuring that programme-focused quality reviews are sufficiently diversified to accommodate the range of higher education providers.

Ensuring selection and training processes for peer reviewers, including foreign academics, are rigorous and appropriate.

Advising the Secretary for Public Education which bodies should be recognised to perform the work of evaluation, assessment, and accreditation of higher education institutions and programmes.

Giving advice to government on questions of policy related to quality, including on suitable policy targets for the Sectoral Education Programme, and the means best suited to achieve them.

Advising the Secretary for Public Education on programmes or institutions that fail to meet quality standards, and should therefore be subject to de-recognition (in the private sector) or loss of eligibility for public funds (discretionary funds awarded through calls and competition).

Advising the SEP on the data infrastructure that is needed to support the monitoring of quality in a reformed RVOE process, and to determine whether HEIs are eligible for self-accrediting status.

References

[22] ANUIES (2018), Visión y acción 2030: Propuesta de la ANUIES para renovar la educación superior en México, Asociación Nacional de Universidades e Instituciones de Educación Superior (ANUIES), México, D. F., http://www.anuies.mx/media/docs/avisos/pdf/VISION_Y_ACCION_2030.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2018).

[3] CHEA (2016), The CIQG International Quality Principles: Toward a Shared Understanding of Quality, Council for Higher Education Accreditation/International Quality Group, Washington, DC, https://www.chea.org/userfiles/CIQG/Principles_Papers_Complete_web.pdf.

[7] CIEES (2018), CIEES in English, Comités Interinstitucionales para la Evaluación de la Educación Superior (CIEES), CDMX, https://ciees.edu.mx/ciees-in-english/ (accessed on 22 November 2018).

[8] CIEES (2018), Proceso general para la evaluación de programas educativos de educación superior, Comités Interinstitucionales para la Evaluación de la Educación Superior (CIEES), CDMX, http://www.ciees.edu.mx (accessed on 22 November 2018).

[26] CIEES (2017), Estándares para la acreditación de funciones de instituciones de educación superior de México 2017, Comités Interinstitucionales para la Evaluación de la Educación Superior (CIEES), CDMX, http://www.sgc.uagro.mx/Descargas/CIEES.pdf.

[25] Cifuentes-Madrid, J., P. Landoni Couture and X. Llinas-Audet (2015), Strategic Management of Universities in the Ibero-America Region: A Comparative Perspective, Springer International Publishing, Dordrecht, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14684-3.

[9] COPAES (2018), Padrón de Evaluadores, Consejo para la Acreditación de la Educación Superior A.C. (COPAES), Ciudad de México, http://www.copaes.org/padron_evaluadores.php (accessed on 26 October 2018).

[20] DGESU (2018), Corte 31 de Agosto 2018 - matricula de calidad, Dirección General Educación Superior Universitaria, http://www.dgesu.ses.sep.gob.mx/Calidad.aspx (accessed on 24 October 2018).

[2] ESG (2015), Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG).

[11] FIMPES (2018), ¿Qué es la FIMPES?, Federación de Instituciones Mexicanas Particulares de Educación Superior (FIMPES), Ciudad de México, https://www.fimpes.org.mx/index.php/fimpes/que-es-la-fimpes (accessed on 29 October 2018).

[12] FIMPES (2018), Sistema de Acreditación a través del Desarrollo y Fortalecimiento Institucional, Federación de Instituciones Mexicanas Particulares de Educación Superior (FIMPES), Ciudad de México, https://www.fimpes.org.mx/congreso-academico/images/banners/V3_2/Index.html (accessed on 29 October 2018).

[27] Gacel-Ávila, J. and S. Rodríguez-Rodríguez (2018), Internacionalización de la educación superior en América Latina y el Caribe. Un balance, UNESCO IESALC, Universidad de Guadalajara, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, México, http://obiret-iesalc.udg.mx/sites/default/files/publicaciones/libro_internacionalizacion_un_balance_0.pdf.

[15] Gobierno de la República (2018), Becas CONACyT Nacionales 2018 Inversión en el Conocimiento, Dirección Adjunta de Posgrado y Becas, CONACyT, México, D.F., https://www.conacyt.gob.mx/index.php/convocatorias-b-nacionales/convocatorias-abiertas-becas-nacionales/16819-conv-bn-18/file (accessed on 29 October 2018).

[19] Gobierno de la República (2014), Firma de Convenio entre el CONACyT y Universidades Particulares para Fomentar el Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico de México, CONACyT, México D.F., https://www.conacyt.gob.mx/index.php/comunicacion/comunicados-prensa/293-firma-de-convenio-entre-el-conacyt-y-universidades-particulares-para-fomentar-el-desarrollo-cientifico-y-tecnologico-de-mexico (accessed on 29 October 2018).

[17] Ibarra Colado, E. (2009), “Impacto de la Evaluación en la Educación Superior Mexicana: Valoración y Debates”, Revista de la Educación Superior, Vol. 38/149, pp. 173-182, http://publicaciones.anuies.mx/pdfs/revista/Revista149_S5A1ES.pdf.

[1] INQAAHE (2016), INQAAHE Guidelines of Good Practices 2016 - revised edition, International Network for Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (INQAAHE), Barcelona, http://www.inqaahe.org/.

[24] Lemaitre, M. and M. Zenteno (2012), Aseguramiento de la calidad en Iberoamerica: Educación Superior Informe 2012, Centro Interuniversitario de Desarrollo (CINDA), Santiago.