This chapter looks at how the Republic of North Macedonia can align school evaluation with its core purposes of accountability and improvement. The country has developed a robust school evaluation framework, however it has not been fully implemented or appropriated by stakeholders. Rather than encouraging a culture of reflection in the country, school evaluation focuses largely on compliance. This is exacerbated by a useful, yet complicated evaluation framework, which inspectors and schools find difficult to apply, and little support to schools to use evaluation results to lead improvements. North Macedonia should take steps to bridge the gap between the purpose of school evaluation and its perception among stakeholders. Another key priority is to make the process more manageable and provide schools with greater support to ensure that they appropriate evaluation and direct improvement.

OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: North Macedonia

Chapter 4. Aligning school evaluation with its core purposes of accountability and improvement

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Introduction

The core purpose of school evaluation is to help schools improve their practices and keep them accountable for the quality of the education that they provide to students. Over the past ten years, the Republic of North Macedonia (referred to as “North Macedonia” hereafter) has developed a school evaluation framework that covers the key areas that are important for an effective school evaluation system, in particular the quality of teaching and learning practices.

However, this framework has not been fully implemented or appropriated by stakeholders. Both external and self-evaluation focus largely on ensuring compliance with the framework, rather than encouraging a culture of reflection and improvement in schools. Fundamentally, this reflects a disconnect between the aims of the framework – to enhance school quality and school-led improvement – and the perception of evaluation among inspectors and schools as an administrative requirement. This is exacerbated by a useful, yet complicated evaluation framework, which inspectors and schools find difficult to apply, and by the lack of support to schools on how to use evaluation results to inform improvements efforts.

The State Education Inspectorate (SEI) needs to be urgently reformed to take on a role of leadership and responsibility for the quality of the country’s schools. This role will need to be matched by far greater scrutiny and accountability of the inspectorate, so that it is accountable for the quality of its work. Another priority is to better support schools ‒ through evaluation follow-up, training, data and adequate financial resources – so that they can appropriate evaluation to direct improvements. Finally, small changes to the evaluation framework and process will help to better orient evaluation towards improvement and create a more manageable process for schools and inspectors.

Key features of an effective school evaluation system

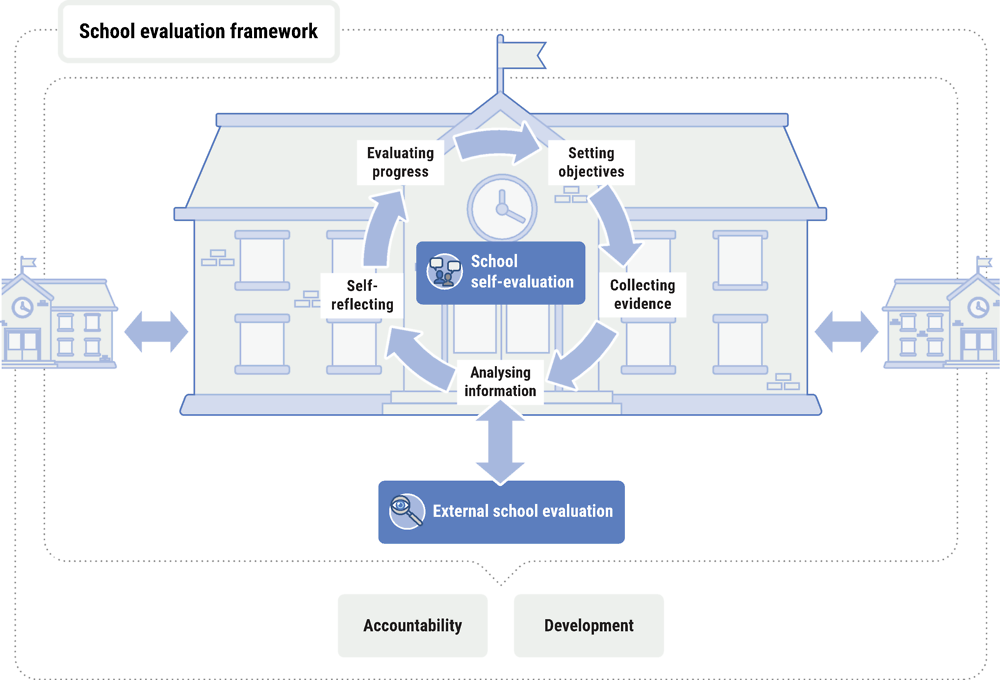

In most OECD countries, school evaluations ensure compliance with rules and procedures, and focus increasingly on school quality and improvement (see Figure 4.1). Another recent trend has been the development of school self-evaluation, which has become a central mechanism for encouraging school-led improvement and objective setting. Internationally, strengthened systems for external and school-level monitoring and evaluation are seen as essential complements to the increasing decentralisation of education systems to ensure local and school accountability for education quality.

Frameworks for school evaluation ensure transparency, consistency and focus on key aspects of the school environment

Frameworks for school evaluation should align with the broader aims of an education system. They should ensure that schools create an environment where all students can thrive and achieve national learning standards. As well as ensuring compliance with rules and procedures, effective frameworks focus on the aspects of the school environment that are most important for students’ learning and development. These include the quality of teaching and learning, support for teachers’ development, and the quality of instructional leadership (OECD, 2013[1]). Most frameworks also use a measure of students’ educational outcomes and progress according to national learning standards, such as assessments results or teachers’ reports.

A number of OECD countries have developed a national vision of a good school (OECD, 2013[1]). The vision guides evaluation, helping to focus on the ultimate purpose of ensuring that every school is good. Visions are often framed around learners, setting out how a good school supports their intellectual, emotional and social development.

Figure 4.1. School evaluation framework

Countries’ external evaluations balance accountability and improvement

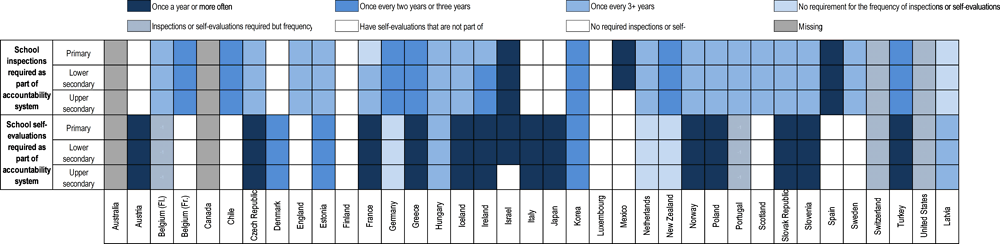

The vast majority of OECD countries have external school evaluation (see Table 4.1). Schools tend to be evaluated on a cyclical basis, most commonly every three to five years. (OECD, 2015[2]). Within the broad purpose of evaluating school performance, some countries emphasise accountability for teaching quality and learning outcomes. In these countries, national assessment data, school ratings and the publication of evaluation reports play an important role. In contrast, in countries that place greater emphasis on improvement, evaluations tend to focus more on support and feedback to schools. They also place strong emphasis on helping schools develop their own internal evaluation and improvement processes.

Evaluations aim to establish a school-wide perspective on teaching and learning

Administrative information for compliance reporting is a standard source of information for evaluations, although it is now collected digitally in most countries (OECD, 2015[2]). This frees up time during school visits to collect evidence of school quality. Most evaluations are based on a school visit over multiple days. Visits frequently include classroom observations. Unlike for teacher appraisal, these observations do not evaluate individual teachers but rather aim to cover a sample of classes across different subjects and grades to establish a view of teaching and learning across the school. Inspectors also undertake interviews with school staff, students and sometimes collect the views of parents. Since much of this information is qualitative and subjective, making it difficult to reliably evaluate, countries develop significant guidance such as rubrics for classroom observations to ensure fairness and consistency.

Many countries have created school inspectorates in central government

External evaluations are led by national education authorities, frequently from central government (OECD, 2013[1]). Across Europe, most countries have created an inspectorate that is affiliated to, but frequently independent of government. This arrangement ensures integrity and enables the inspectorate to develop the significant professional expertise necessary for effective evaluation. School inspectors may be permanent staff or accredited experts contracted to undertake evaluations. The latter provides flexibility for countries, enabling them to meet the schedule of school evaluations and draw on a range of experience, without the costs of maintaining a large permanent staff. Inspectors across OECD countries are generally expected to have significant experience of the teaching profession.

Figure 4.2. School evaluation in OECD countries

Source: (OECD, 2015[2]), Education at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2015-en.

The consequences of evaluations vary according to their purpose

To serve improvement purposes, evaluations must provide schools with clear, specific feedback in the school evaluation report, which helps them understand what is good in the school, and what they can do to improve. To follow-up and ensure that recommendations are implemented, countries often require schools to use evaluation results in their development plans. In some countries, local authorities also support evaluation follow-up and school improvement. Around half of OECD countries use evaluation results to target low-performing schools for more frequent evaluations (OECD, 2015[2]).

In most countries, evaluations also result in a rating that highlights excellent, satisfactory or underperforming schools. To support accountability, most OECD countries publish evaluation reports (OECD, 2015[2]). Public evaluation reports can generate healthy competition between schools and are an important source of information for students and parents in systems with school choice. However, publishing reports also risks distorting school-level practices such as encouraging an excessive focus on assessment results or preparation for evaluations. This makes it critical that evaluation frameworks emphasise the quality of school-level processes, and an inclusive vision of learning where all students, regardless of ability or background, are supported to do their best. Evaluation systems that emphasise decontextualised outcome data like assessment results are likely to unfairly penalise schools where students come from less advantaged backgrounds, since socio-economic background is the most influential factor associated with educational outcomes (OECD, 2016[3]).

Self-evaluation is an internal tool for improvement

Most OECD countries require schools to undertake self-evaluations annually or every two years (see Figure 4.2). Self-evaluations encourage reflection, goal setting and inform school development plans (OECD, 2013[1]). To be an effective source of school-led improvement, many countries encourage schools to appropriate self-evaluation as an internal tool for improvement rather than an externally imposed requirement. In some countries, schools develop their own frameworks for self-evaluation. In others, they use a common framework with external evaluation, but have the discretion to add or adapt indicators to reflect their context and priorities.

The relationship between external and internal evaluations varies across countries. In general, as systems mature, greater emphasis is placed on self-evaluation while external evaluation is scaled back. Most OECD countries now use the results from self-evaluations to feed external evaluations, with, for example, inspectors reviewing self-evaluation results as part of external evaluations. However, the relationship is also shaped by the degree of school autonomy – in centralised systems, external evaluations continue to have a more dominant role, while the reverse is true for systems that emphasise greater school autonomy.

Effective self-evaluation requires strong school-level capacity

Effective self-evaluation requires strong leadership, and strong processes for monitoring, evaluating and setting objectives (SICI, 2003[4]). Many OECD countries highlight that developing this capacity in schools is a challenge. This makes specific training for principals and teachers in self-evaluation – using evaluation results, classroom and peer observations, analysis of data and developing improvement plans – important (OECD, 2013[1]). Other supports include guidelines on undertaking self-evaluations and suggested indicators for self-evaluations.

While a principal’s leadership plays a critical role in self-evaluation, creating teams to share self-evaluation roles is also important. The most effective self-evaluation team involves a range of staff that are respected by their colleagues and have a clear vision of how self-evaluation can support school improvement. In order to support collective learning, self-evaluation should engage the whole school community. This includes students, who have a unique perspective on how schools and classrooms can be improved (Rudduck, 2007[5]). Students’ views also help to understand how the school environment impacts students’ well-being and their overall development. This is important for evaluating achievement of a national vision focused on learners.

Data systems provide important inputs for evaluation

Administrative school data – like the number of students, their background and teacher information – provides important contextual information for internal and external evaluators. Increasingly, countries use information systems that collect information from schools for multiple purposes including evaluation and policy making.

Most countries also collect information about school outcomes. Standardised assessments and national examinations provide comparative information about learning to national standards. Some countries also use this information to identify schools at risk of low performance and target evaluations (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[6]). However, since assessment results do not provide a full picture of a school, they are often complemented by other information like student retention and progression, student background, school financial information and previous evaluation results. A number of countries use this data to develop composite indicators of school performance. Indicators frequently inform evaluation and support school accountability.

Principals must be able to lead school improvement

Strong school leadership is essential for effective school self-evaluation, and school improvement more generally. Principals support evaluation and improvement through a number of leadership roles – defining the school’s goals, observing instruction, supporting teachers’ professional development and collaborating with teachers to improve instruction (Schleicher, 2015[7]). This diversity points to a major shift in the principal’s role in recent years, with principals increasingly leading instructional improvement.

Principals need a deep understanding of teaching and learning, and strong leadership skills to become instructional leaders

Most principals bring significant experience of the teaching profession – among the countries participating in the OECD Teacher and Learning International Survey (TALIS), the average principal has 21 years of teaching experience. Teaching experience alone however is not sufficient, and the ability to demonstrate strong leadership of the school community is particularly important. Nearly 80% of principals in TALIS participating countries reported that they received training in instructional leadership either before or after taking up their position, or both (OECD, 2014[8]).

Principals’ initial training must be complemented by opportunities for continued professional development once in post. One of the most effective types are collaborative professional learning activities, where principals work together to examine practices and acquire new knowledge (DuFour, 2004[9]). In countries where international assessment results suggest that learning levels are high like Australia, the Netherlands and Singapore, more than 80% of principals reported participating in these kinds of activities in the last 12 months (OECD, 2014[8]).

Professionalising school leadership – standards, selection and appraisal

Given the important role that principals occupy, OECD countries are taking steps to professionalise the role. A number of countries have developed professional principal standards that set out what a school leader is expected to know and be able to do. Principal standards should include how principals are expected to contribute to self‑evaluation and improvement. Similar to teachers, principal standards guide the recruitment of principals, their training and appraisal.

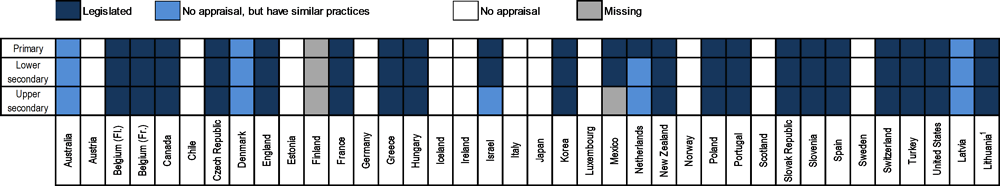

Around half of OECD countries have legislated appraisal of school leaders (see Figure 4.3) (OECD, 2015[2]). These kinds of appraisals hold principals accountable for their leadership of the school, but also provide them with valuable professional feedback and support in their demanding role. Responsibility for principal appraisal varies. In some countries, it is led by central authorities, like the school inspectorate or the same body that undertakes external teacher appraisals. In others, it is the responsibility of a school-level body, like the school board. While the latter provides the opportunity to ensure that appraisal closely reflects the school context, boards need significant support to appraise principals competently and fairly.

Figure 4.3. Existence of school leader appraisal in OECD countries (2015)

Notes: Data for Lithuania are drawn from (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[6]) Assuring Quality in Education: Policies and Approaches to School Evaluation in Europe, The European Union, Luxembourg, https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/4a2443a7-7bac-11e5-9fae-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 15 June 2018).

Sources: OECD (2015[2]), Education at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2015-en and European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2015) Assuring Quality in Education: Policies and Approaches to School Evaluation in Europe, The European Union, Luxembourg, https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/4a2443a7-7bac-11e5-9fae-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 21 June 2018).

School governance in North Macedonia

The school leadership function is relatively underdeveloped in North Macedonia. Principals receive little training or guidance to lead the school, and limited support from school boards. In recent years the Ministry of Education and Science (MoES) has taken some steps to address these concerns. In 2016, a new training and licensing process was introduced to ensure that new principals receive minimum preparation in core aspects of school leadership. However, the principal role remains primarily administrative, and principals’ capacity to steer teaching and learning and set goals for improvement remain relatively limited. In addition, the politicisation of the appointment process and high turnover rate make it difficult to develop a corps of professional school principals with experience and competence.

Principals receive little training in instructional leadership and school management

As is the case in most European countries, school principals in North Macedonia are required to have a Bachelor’s degree and some teaching experience (at least five years) (Eurydice, 2013[10]). However, the Law on Principles envisages that principal candidates must undertake 192 hours of mandatory training over a year provided by the National Examination Centre (NEC) since 2016. Contrary to training programmes in many OECD and European countries, the training in North Macedonia is primarily theoretical and does not include practical training, where new school principals or candidates can observe the work of an experienced principal (Eurydice, 2013[10]). At the end of the training, candidates take the school principal certification and licensing examination, also administered by the NEC (60% in 2018). The examination is organised at least twice a year and consists of three parts: practical test of computer skills, test to assess the candidates’ theoretical knowledge and a presentation of a seminar paper, including a case study. After passing the certification exam, new principals need to find a school placement within five years.

Once in school, principals receive very limited in-service training (four days a year) and there are no specific modules for vocational education and training (VET) schools. The principals have to find and pay for the professional development programmes they undertake themselves.

The hiring of school principals is highly politicised

School boards are responsible for selecting principals. The board issues a call for application and selects a candidate from a pool of licensed principals. However, there are no national guidelines or criteria to guide the board in the selection process. Municipalities are responsible for validating the board’s choice for secondary education institutions. The municipality can only refuse a board’s nomination once. This rule was introduced in 2004 to try to curb municipal political interference in school appointments. However, it was reported to the OECD team that in practice, political influence means that principals often continue to be selected from candidates of the same party in power at the municipal level.

High turnover make it difficult to develop a professional school leadership body

The school board is also responsible for renewing principals’ appointments at the end of their four-year mandate, but most principals are not renewed and go back to being full‑time teachers. For example, principals surveyed for this review reported being a principal for four years on average. This is short compared to the average years of experience that principals in OECD countries report - nine years) (OECD, 2014[8]). It was reported to the review team that one reason for such frequent change is that principals are rarely renewed when the party in power at the municipal level changes. In addition, the SEI, the body in charge of school external evaluation in North Macedonia, is sometimes requested to conduct ad hoc school inspections to justify a political decision to dismiss a principal.

School boards are involved in key strategic decisions, but lack training and independence

School boards are also responsible for validating school self-evaluation reports and schools’ annual work plans, and indicating the school’s budget needs to the municipality. The board comprises 9 members in primary schools and 12 members in secondary schools representing the teacher council, the parent association, students and the local community, elected for 4 years.

Despite their important responsibilities, boards receive limited national support. For example, there are no national guidelines for boards. While there are manuals and workshops available, the board members that the review team met had not received any training. Political interference in the boards’ decisions regarding principal hiring and firing, and their general functioning further hinder their capacity to steer decisions at the school level.

There are few formal school roles or bodies that support the principal

Principals are not supported by any administrative staff, and do not have a deputy to share leadership responsibilities. There is no formal practice of experienced teachers taking on leadership for their subject or for teaching more broadly across the school. While there is a proposal to define clearer pedagogical leadership for teachers as part of a differentiated career structure, this has yet to be implemented (see Chapter 3).

The main support for principals comes from the multi-actor team of a pedagogue, psychologist and special needs teacher. However, there are a number of issues which hinder the team’s capacity to support teaching and learning effectively. Notably, their lack of practical teaching experience and predominant focus on identifying special learning needs, rather than being driven by a more inclusive approach for adapting learning to the individual needs of all students (see Chapter 3).

School evaluation in North Macedonia

North Macedonia has well-established practices for school evaluation. In 2011, an external evaluation process, called the School Integral Evaluation carried out by the State Education Inspectorate, was introduced. The process aims to evaluate the quality of schools to inform improvement by providing formative feedback to stakeholders. Since 2008, schools have also been required to undertake self-evaluation every two years (Table 4.1). However, in reality, both school external and self-evaluation focus primarily on compliance with regulation and administrative processes, and do not give schools specific, high quality feedback to improve learning and teaching practices.

Table 4.1. School evaluation in North Macedonia

|

Types of school evaluation |

Reference standards |

Body responsible |

Guideline documents |

Process |

Frequency |

Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

School external evaluation |

The School Performance Quality Indicators (SPQI) framework |

State Education Inspectorate |

School Integral Evaluation Handbook |

1. Preparatory phase (inspectors check school documents and schools complete a questionnaire. 2. Implementation phase (3 days visit by three inspectors for interview, classroom observations and check additional documents). 3. Reporting phase (draft the school report). |

Every three years |

Provide feedback to the school on its performance. A follow-up school visit is organised 6 months after the evaluation to check if recommendations were effectively implemented. |

|

School self‑evaluation |

The school |

Rulebook for school self-evaluation in secondary schools |

The guidelines define that the school self-evaluation should include three phases (preparatory phase, implementation phase and dissemination and action plan adoption phase). |

Every two years |

Used to inform the school action plan. |

Source: (MoES, 2018[11]), Republic of North Macedonia - Country Background Report, Ministry of Education and Science, Skopje.

School performance quality indicators set expectations for school evaluation but gaps remain

The School Performance Quality Indicators (SPQI) framework developed in 2011, and refined in 2014, is the key reference document for school evaluation in North Macedonia. The SPQI framework was modelled on indicator frameworks in countries with long standing traditions of school evaluation such as Scotland in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. It includes seven areas of evaluation, which are common to both the external evaluation carried by the State Education Inspectorate and schools’ self-evaluations (see Table 4.2).

These areas cover most of the main factors that research suggests are important for school quality such as teaching and learning practices, school environment, school planning and management. Each area includes several indicators to measure school performance. The descriptors include both qualitative descriptions of school practices like teaching and learning practices (see example in Table 4.3), and administrative compliance descriptors. However, there are some notable gaps such as the absence of indicators on school principals’ pedagogical leadership and the quality of school self-evaluation. For each indicator, schools receive a rating of: very good, good, satisfactory, or not satisfactory. They also receive an overall rating. It was reported to the OECD that most schools get a good rating, but less than 1% received a very good rating (MoES, 2018[11]).

While it has an established school evaluation framework, North Macedonia does not have a national vision of a good school. An increasing number of OECD countries have developed a vision of a good school to guide evaluation. The vision helps focus evaluation on accountability for school quality and improvement, to avoid that evaluation becomes a check box exercise. North Macedonia could build on the SPQI when developing its national vision. Countries frequently use national consultations including teachers and principals to develop the national vision, creating opportunities to build national understanding of the purpose of school evaluation for educational improvement. Countries may also choose to include additional criteria specific to vocational schools to acknowledge their different mandate.

Table 4.2. North Macedonia’s School Performance Quality Indicator Framework

|

Area |

Indicators |

|---|---|

|

School curriculum |

|

|

Student outcomes |

|

|

Teaching |

|

|

Student support |

|

|

School environment |

|

|

Resources |

|

|

Management, governance and policy making |

|

Source: (State Education Inspectorate, 2014[12]), Indicators of school quality, http://dpi.mon.gov.mk/images/pravilnici/IKRU-MAK.pdf.

Table 4.3. Examples of descriptors for the indicator “teaching process” in the SPQI framework

|

Area |

Indicators |

Examples of descriptors of a “very good” school |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Teaching |

Teaching process |

|

Source: (State Education Inspectorate, 2014[12]), Indicators of school quality, http://dpi.mon.gov.mk/images/pravilnici/IKRU-MAK.pdf.

School external evaluation does not fulfil its school improvement purpose

The School Integral Evaluation is carried out in all schools every three years, to evaluate the quality of school practices and inform improvement (Government of the Republic of North Macedonia, 2015[13]). During the evaluation, the inspection team collects data and school documents like the school plan, observes the classroom practices of all teachers and interviews school staff, the school board, representatives of the parent council and students. At the end of the visit, the inspectors discuss the results with the principal and submit a written report to the school within two weeks. The evaluated school then sets an action plan detailing how it intends to implement the recommendations from the evaluation, and submits it to the SEI (see Table 4.1).

The process and tools for evaluation do not reflect its intended purpose

There is a perception throughout the SEI that the primary role of evaluation is to monitor schools’ compliance with the law and regulation. Moreover, the tools for evaluation focus primarily on checking whether the school has documented its processes (e.g. recorded minutes of council meetings or the availability of a school plan), and not as extensively on a qualitative assessment of teaching and learning practices. This is apparent when looking at the limited time allocated for classroom observations (one-fifth of the evaluation visit time) which is mostly used to check classroom documents (e.g. student portfolios and teacher plans), leaving little time for observing classroom teaching and stakeholder interviews. In contrast, the quality of instruction is a central component of external evaluations in 22 out of 35 OECD countries (OECD, 2015[2]).

School integral evaluation reports are provided to the school and made public

Schools receive written reports detailing their strong points and areas for improvement across the seven areas of the school evaluation framework. While schools are given a descriptive mark overall and for each of the seven areas, these scores are not accompanied by descriptions of performance justifying the score. The Handbook for School Integral Evaluation provides detailed guidelines for inspection teams about how to draft the report, such as making it clear and writing in an accessible manner. The school reports are made public and available on the State Education Inspectorate’s website.

Evaluation is perceived to be high stakes by school actors

School staff reported to the OECD team feeling that the significant number of documents produced and kept for the integral evaluation distracts them from their core mission and responsibilities. This perception may be due to the fact that they often prepare all the documentation in few days, before the integral evaluation, rather than regularly throughout the year. Teachers and students reported feeling stressed and under pressure to perform well during the evaluations. The introduction in 2014 of individual teacher appraisals as part of integral evaluations might have contributed to teachers’ perception of evaluation as high stakes, as every teacher is scored. However, the grade has no impact on a teachers’ career and teachers do not receive written feedback on their performance (see Chapter 3).

The State Education Inspectorate lacks professional independence

The State Education Inspectorate that leads integral evaluations is a separate body, but remains part of the ministry. The SEI is strongly influenced by the ministry, which manages its budget annually and selects its director. On occasion, the SEI’s work has been subject to political influence, such as when the inspectorate has been requested to undertake inspections to justify principal dismissals. Unlike in many OECD and other European countries, integrity and professional independence are not sufficiently emphasised as expectations for the SEI’s director’s role, even though staff are required to adhere to a code of conduct.

Another reason that the SEI lacks professional independence is its limited accountability. Like the other ministry agencies in North Macedonia, there are few mechanisms to ensure that the inspectorate is effectively fulfilling its mandate. In contrast, most OECD countries have statutory requirements to keep inspectorates accountable for the quality of their work. This includes annual reports, parliamentary hearings, and performance reviews.

Inspectors receive little training or guidance on how to undertake evaluations

As is the case in most European countries, state inspectors in North Macedonia are former teachers with a minimum of five years of experience (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[6]). However, contrary to practices in most European countries, they receive little preparation – just three days ‒ for the role of inspector. This is far less than new inspectors commonly receive in most European countries, which varies from several months to one year (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[6]). In North Macedonia, there is also no regular professional development for inspectors once they are in post. Inspectors may occasionally take part in training on new reforms organised by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and donor institutions. Unlike the practice in a number of OECD countries, the inspectorate relies solely on a corps of permanent inspectors.

The lack of preparation and training that inspectors receive significantly limits their capacity to provide meaningful feedback to schools. It also undermines their authority in schools.

The quality of school self-evaluation varies

Almost all (99%) of students participating in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2015 were in schools that conduct self-evaluations (OECD, 2016[3]). During the preparatory phase of self-evaluation, the school board forms an ad hoc, self-evaluation committee that leads the evaluation. School principals are responsible for establishing the committees, but are not themselves a member of it. The self-evaluation committee includes teachers, students, school support staff, parents and the local and business community (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[6]). The committee assesses the school’s performance in the seven areas specified by the SPQI indicators and drafts a self-evaluation report that is submitted to the school board and principal. The reports are also made available online for the wider public.

Schools receive limited guidance and tools to undertake self-evaluations, resulting in considerable heterogeneity in practices and quality. A rulebook for self-evaluation defines the areas that schools need to look at, which are the same seven domains as in the SPQI framework. However, the rulebook does not define the indicators that schools should use to evaluate quality or possible sources of evidence. As evaluation systems mature, they frequently provide schools with considerable autonomy to determine self-evaluation procedures. However, at the beginning, when effective self-evaluation is still being established, some guidance is important. The absence of such guidance in North Macedonia risks that evaluations do not consistently address key issues of school quality, and that conclusions are not based on valid evidence. The review team analysed four school self-evaluation reports and found that while all four reports included an analysis of strengths and weaknesses, in most cases very little evidence was given to explain the choices of priority actions.

Self-evaluations may also not be consistently drawing on a broad range of evidence. Classroom observations, discussions with school staff, data analysis and discussions with students are all important sources of evidence to understand overall school quality. However, in only one of the four reports that the review team read were the opinions of students and parents reflected.

Schools’ capacity for self-evaluation is limited

School principals and other staff receive no mandatory training in school self-evaluation as part of their initial training or while in-service. In contrast, in most OECD countries, principals’ initial training include modules on school self-evaluation and planning (OECD, 2013[1]). Some NGOs and donor organisations have taken the initiative to provide training to improve the school capacity for self-evaluation, but this remains occasional.

Schools use evaluation results to draft their school action plan, which is developed every four years. The State Education Inspectorate uses self-evaluation results to inform external school evaluations. Although the inspectorate reviews the quality of the self‑evaluations by reviewing the report and interviewing school staff, it does not systematically provide schools with feedback on the quality of their self-evaluations.

Other forms of school evaluation and quality assurance

In addition to integral evaluations, the SEI carries out frequent ad-hoc inspections of school practice or individual practices following a formal complaint from parents, parent councils, school staff or other citizens. Municipalities can also carry out audits of schools to monitor compliance with regulation and finances.

Policy issues

While North Macedonia has the foundations for an effective school evaluation system, a number of factors are currently preventing the latter from coming to fruition. A major issue that requires immediate attention is creating an inspectorate with the integrity, independence and capacity to act with professional authority. Simple changes to the evaluation framework and process will help to create a more manageable system that schools and inspectors can apply more easily to evaluate school quality. Finally, schools will need more direct support and resources, so that they can fully use external evaluation results, and adopt self-evaluation as an internal tool for their own improvement.

Policy issue 4.1. Professionalising the State Education Inspectorate

External school evaluation in North Macedonia does not yet fulfil its stated core functions of ensuring school accountability and helping them improve. The process is focused heavily on ensuring schools’ compliance with regulations and administrative processes, and the SEI lacks the technical capacity and independence to lead a meaningful school evaluation system.

To make external evaluation more effective, North Macedonia needs to invest in professionalising the SEI. The inspectorate needs to be reformed so that it undertakes its role with independence and integrity and is accountable for the quality of its work. This needs to be accompanied by building professional capacity for school evaluation within the SEI.

Recommendation 4.1.1. Guarantee the independence and integrity of the inspectorate

The stated purpose of evaluation in North Macedonia is to improve school quality. However, the overwhelming perception of evaluation – external and internal - as reported to the review team by the inspectorate, principals and teachers, was as a process to ensure compliance with regulations and the evaluation framework. Creating more meaningful school evaluation requires a shared national understanding of the important role that it is expected to play for school improvement. A number of steps are important to create this understanding.

First, the head of the SEI needs to be appointed based on demonstrated competence in school improvement. Second, increased professional independence of the SEI needs to be balanced by greater oversight of, and accountability for, the inspectorate’s work. Accompanying these measures with a national consultation to create a vision of a good school will encourage national understanding and ownership of evaluation as a means to support school improvement. Developing a national vision will also help to keep evaluation focused on its core purpose of school improvement.

Ensure the integrity and professional competence of the SEI’s director

Leadership of the SEI is key for shaping how staff within the SEI and schools understand the role of school evaluation. The SEI’s director must combine a deep understanding of school improvement, strong leadership skills and integrity. As well as being responsible for the quality of the country’s schools, the director should hold a senior leadership position within a country’s education system, regularly advising the ministry and minister directly, on issues of school quality.

At present however in North Macedonia, the director of the SEI is not expected to occupy this leadership role. The minimum eligibility requirements for the director are similar to those of other inspectors (e.g. five years of teaching experience, having at least a bachelor’s degree). In contrast, Education Scotland, a country where school evaluation has a major role in school improvement, defines the role of the Director of Inspection as “a member of the senior management team [of Education Scotland] with appropriate experience, stature and credibility in relation to Scottish education, quality evaluation and improvement” (Education Scotland, n.d.[14]).

The ministry should revise the selection criteria and recruitment process for the director of the SEI, to focus on demonstrating significant professional expertise in school improvement. The selection process should also require candidates to demonstrate their strong understanding of the role of evaluation, and how it impacts school quality.

Ensure that inspectors undertake their role with utmost integrity

One step to ensure that inspectors carry out their role with integrity and independence is to encourage the widespread use of the existing code of practice that sets out how inspectors are expected to perform their duties. North Macedonia’s codes of practice ‒ including one currently being developed ‒ should provide inspectors with a practical handbook that sets out the ethical values and principles they are expected to follow. It should also explicitly indicate practices which are considered unethical.

Another important step is to ensure, given the inspectorate’s influence, that all stakeholders – principals, teachers, students and parents – have clear and fair opportunities to redress any grievances. For example, all actors should clearly understand how to make a complaint about an evaluation. As well as having a clearly stipulated internal complaints and review process, most countries also have parliamentary ombudsmen, to deal fairly with complaints about public organisations.

Create a board to oversee the SEI’s work

Given the powerful influence that inspectorates have on schools’ work, a number of countries have boards, composed of respected educationalists that help to maintain the inspectorate’s independence and integrity. In North Macedonia, such a board could also play an important oversight role ‒ monitoring the work of the inspectorate to ensure that it is focused on school quality and improvement and does not veer into administrative compliance checks again.

The independent advisory board should be composed of education professionals with significant experience in school improvement. Given North Macedonia’s ethnic composition, the board might also include representatives from the country’s main communities, Macedonian, Albanian and possibly others. North Macedonia might also consider inviting one or more international representatives to provide an external perspective and guidance. One option is a representative from a country with an established tradition of school evaluation – such as the Netherlands or Scotland (United Kingdom). Alternatively a country that has relatively recently established school evaluation – such as Romania – could be invited to provide practical advice in addressing common challenges.

Make the SEI accountable for the quality of its work

The SEI is legally required to produce annual, public reports on the inspectorate’s work and the quality of the education system based on the integral evaluation results. To ensure that these reports produce valuable information for the system, North Macedonia can look to the many examples of inspectorate reports from other countries. In England for example, the state inspectorate Ofsted, produces an annual report on its performance, governance, and finances. In the report, Ofsted reports its performance against key objectives, including how far schools perceive the inspectorate to be a force for improvement, and ensuring that inspections focus on learning standards for all groups of students (Ofsted, 2018[15]).

In North Macedonia, as in other countries, the ministry should also consider requiring that the inspectorate’s annual report be debated in parliament. In England, the senior leadership of Ofsted is required to attend a hearing of the investigative parliamentary committee on education. This kind of public reporting and debate in North Macedonia will create impetus within the inspectorate to better understand its role, and the accountability to encourage each inspector to focus on achieving it. Over time, public reporting and debate will educate the wider education system and the public on the role of the inspectorate.

Develop a national vision of a “good school”

While the overall framework for school evaluation in North Macedonia focuses on many of the important aspects of school quality, it is not guided by an overall vision of schooling. This vision is important to avoid that evaluation becomes focused on mechanically complying with individual descriptors in the evaluation framework. Instead, it helps to focus teachers, schools and evaluators on the fundamental purpose of evaluation – to create schools where all students can learn and thrive.

In general, visions are often short and simple (see Box 4.1). Avoiding long, complicated descriptive text helps to ensure that schools and evaluators do not become distracted interpreting what the vision means. It also makes the vision easier for schools to appropriate as a goal that guides their own planning and self-evaluation, and for external evaluators to reflect upon during school evaluations.

Box 4.1. Defining “good schools” at the national level

Education systems develop a definition of a “good school” at the national level in order to provide standard quality criteria for the evaluation of educational processes and outcomes. This common definition of effectiveness often includes several characteristics, including the quality of teaching and learning, how teachers are developed and made more effective, the quality of instructional leadership, the use of assessment for learning, the rate and equity of student outcomes and progress, setting the school’s vision and expectations, self-evaluation practices and factors concerning the curriculum.

A shared, future-focused and compelling vision at the national level can provide direction and steering to an educational system, bringing key actors together to work towards achieving the vision. It should be shared across all levels of the education system, while allowing space for interpretation based on local or regional differences. A clearly communicated and shared vision can also help ensure reforms continue in the long-term, particularly when faced with challenges or obstacles.

Ontario’s (Canada) vision for education explicitly incorporates goals:

Ontario’s vision for education is focused on four core goals: achieving excellence, ensuring equity, promoting well-being and enhancing public confidence.

In 2008, the government of Japan developed the Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education, in which it set out a ten-year education vision:

1) To cultivate, in all children, the foundations for independence within society by the time they complete compulsory education.

2) To develop human resources capable of supporting and developing our society and leading the international society.

In Estonia, the Lifelong Learning Strategy 2020 guides the formal education system, as well as in-service, non-formal and informal education and retraining. The vision for 2020 is:

Learning is a lifestyle. Development opportunities are noticed and smart solutions are pursued.

In order to develop their national vision, many countries undertake a consultation process. Such a strategy helps to gather input, engage stakeholders and build consensus. Moreover, when education stakeholders, including teachers, support the vision it is more likely they will dedicate time and energy to their roles. Indeed, effective policy implementation requires a shared vision, and the acceptance, ownership and legitimacy of a policy’s plan and purpose and the process of change must be developed among actors in order to move toward the vision (Burns, Köster and Fuster, 2016[16]).

Sources: (OECD, 2013[1]), Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment, OECD Publishing Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264190658-en; (Kitchen et al., 2017[17]), Romania 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264274051-en; (OECD, 2018[18]), Developing Schools as Learning Organisations in Wales, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264307193-en; (Ontario Ministry of Education, n.d.[19]), Education in Ontario, https://www.ontario.ca/page/education-ontario; (MEXT, 2008[20]), Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education (Provisional translation), http://www.mext.go.jp/en/policy/education/lawandplan/title01/detail01/1373797.htm; (Ministry of Education and Research, n.d.[21]), The Estonian Lifelong Learning Strategy 2020, https://www.hm.ee/sites/default/files/estonian_lifelong_strategy.pdf; (OECD, 2018[22]), Education for a Bright Future in Greece, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264298750-en; (Burns, Köster and Fuster, 2016[16]), Education Governance in Action: Lessons from Case Studies, Educational Research and Innovation, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264262829-en.

The process of developing the national vision can be almost as important as the final vision itself. Many countries use its development as an opportunity to undertake a national consultation that involves students, teachers and schools, asking them what they consider the most important characteristics of a good school. This process would be particularly valuable in North Macedonia, since the school evaluation framework and national strategy were developed in the absence of wide consultation. An inclusive process, similar to that undertaken for the development of the Comprehensive Education Strategy 2018-25, would also help promote awareness of the role of evaluation in school quality, and create a sense of ownership of the standards among school actors.

Recommendation 4.1.2. Build the professional capacity of the State Education Inspectorate

Another issue that currently undermines the SEI professional authority is its lack of technical capacity. Inspectors’ initial training is too short and inadequate to enable them to carry out meaningful school evaluations. To build capacity for evaluations, the inspectorate should consider revising the content and length of inspectors’ training, and include other actors from outside the inspectorate in the evaluation teams.

Reinforce the training of school inspectors

The SEI first priority should be to ensure that its current staff have the necessary knowledge and skills to carry out the integral evaluations. Inspectors’ training needs to focus on the major knowledge gaps that are currently preventing inspectors from undertaking evaluations that support school improvement, such as understanding how evaluation supports school accountability and improvement. Training should provide inspectors with practical examples of how school evaluation supports these functions, illustrated by specific evaluation practices that best support accountability and improvement. Training should also help inspectors to identify evaluation practices that only focus on ensuring administrative compliance. Other important areas to address include how to evaluate teaching and learning and how to provide formative feedback.

The ministry should also ensure that the SEI has enough resources to cover regular training of its staff on key priority areas such as curriculum reform, student assessment, and inclusive education and any new reform affecting teaching and learning in schools.

An overriding concern in developing all training should be to ensure that it provides inspectors with practical learning opportunities. For example, inspectors should have the opportunity to try out new techniques and receive feedback, and to participate in an evaluation visit. Practical training on how to conduct meaningful classroom observations will also be essential. Such a model would be similar to the one currently in place in Lithuania, which has also recently introduced school evaluation. In Lithuania, external evaluators complete 80 hours of theoretical training and 45 hours of practical training (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[6]). This training should be provided to full-time inspectors and to the pool of licensed part-time evaluators.

To accommodate the above, the initial training period of inspectors needs to be increased. The current initial training lasts three days which is short compared to initial training of inspectors in other European countries, which in most cases lasts at least several months (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[6]). The limited time is primarily used to review the laws, regulations and the evaluation process. The inspectorate should consider increasing the initial training period.

Create a roster of licensed inspectors to undertake school integral evaluations

The SEI should consider training and licensing experts as external consultants that can join the evaluation teams on an ad hoc basis to contribute different experience and perspectives. This would also be an important learning opportunity – inspectors can learn from other educationalists with different skills and experience, while school leaders that participate in the evaluations of other schools can learn from their practices.

Several inspectorates in OECD countries use similar practices. School inspection teams in Scotland include full-time inspectors as well as high- performing school practitioners such as school principals and deputy school principals from other schools and other non‑education profiles that are contracted as external experts for school evaluations (e.g. doctors, psychologists etc.) (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[6]). The SEI should consider recruiting external inspectors with the following profiles:

Experienced teachers from other schools: when the new teacher career development structure is implemented, the SEI can hire ad hoc inspectors from the pool of expert teachers. Expert teachers will have experience observing classroom practices and providing feedback to their peers (see Chapter 3). As the practice becomes more established, prior participation in an integral evaluation could be a pre-requisite for teachers who want to apply to become permanent inspectors.

Advisors from the Bureau for the Development of Education (BDE) and the Vocational Education and Training Centre (VETC): the Law on the State Education Inspectorate states that BDE advisors and VETC experts can be invited to join evaluations to lead the classroom observation component. Both agencies have some experience in classroom observation and provide closer pedagogical support to schools than the inspectorate. However in practice, the BDE and the VETC are rarely able to join the inspection teams. Including BDE and the VETC experts more regularly will help improve the quality of the classroom observations and ensure alignment in classroom observation practices between the agencies. Advisors from the BDE and the VETC might be given an explicit role to lead or co‑ordinate classroom observations during evaluations.

The inspectorate might also invite other types of experts to join the inspection team based on the focus of the evaluation (e.g. school health, infrastructure, resources, etc.).

Policy issue 4.2. Ensuring that integral school evaluations focuses centrally on improving school quality

There are many aspects of North Macedonia’s school evaluation process that are positive, and reflect the practices used in many OECD countries. Professionalising the SEI and investing in its capacity will help to ensure that it is better equipped to undertake evaluations so that they reflect their intended purpose. However, this review suggests that this will be complemented by a few revisions to the school evaluation framework, so that it becomes a more manageable tool for inspectors to implement. Refocusing follow-up support, so that those schools in greatest need receive proportionally more support, will help to ensure a fairer, more efficient model of follow‑up.

Recommendation 4.2.1. Revise school integral evaluation to focus more centrally on the quality of teaching and learning

While the framework for school evaluation in North Macedonia focuses on many important aspects of school quality, it can be difficult for inspectors to implement. With nearly 30 indicators, it can seem overwhelming for schools and inspectors. Revising the framework to prioritise core indicators will help better orient inspectors in their work. This will be complemented by one important change, which will be to give more space to meaningful evaluation of teaching and learning across the school.

Revise the School Performance Quality Indicators (SPQI) framework to focus on core teaching and learning areas

The School Performance Quality Indicators (SPQI) provides a relatively complete framework, including indicators of school quality and descriptors of the practices and behaviours expected from schools. It is also very positive that the majority of school principals interviewed by the review team were aware of the seven areas of evaluation, which shows that the SPQI is a well‑established reference framework.

However, the framework is very dense compared to indicator frameworks used by OECD countries. The SPQI framework includes seven areas, 28 indicators and 99 parameters detailing further the indicators. In contrast, the indicator framework of Education Scotland, which was used as a model for the SPQI, only includes three areas – Leadership and Management, Learning Provision and Successes and Achievement – and 15 quality indicators (Education Scotland, 2015[23]). A long list of indicators can encourage evaluation to become a checkbox exercise. Internationally, as many countries have implemented their school evaluation frameworks, they have found that it has been important to simplify their frameworks to focus on key aspects of school quality. This is important to move evaluation from a checkbox exercise, to a more focused, in-depth review of the quality of school practices and how they can be improved.

Given that school evaluation in North Macedonia frequently emphasises compliance with descriptors, rather than evaluation of quality, reviewing the evaluation framework to simplify it would be helpful. The number of indicators in the framework should be reduced to around 10 to 15 indicators to make it more manageable for inspection teams and give them more time to focus on key indicators of teaching and learning quality.

The SPQI can be revised to distinguish between a set of core indicators evaluated in each integral evaluation and a set of secondary indicators evaluated on a rotating basis or when a problem arises. The indicators that have a direct and proven impact on improving learning and teaching in schools such as “teaching process” and “students’ learning experience” should be prioritised as core indicators. Indicators related to the quality of the school environment such as “health”, “school climate” and “accommodation and premises” could be evaluated on a rotating basis. The rotation of indicators will also allow the inspectorate to go deeper in investigating the non-core areas and produce thematic reports to inform national policies.

As part of this review, some gaps in the existing framework should also be addressed. The framework should include school pedagogical leadership as an indicator under teaching and learning. The SPQI framework should also include the quality of self‑evaluation and schools’ capacity to reflect on its processes. This might be addressed in an indicator on schools’ capacity for improvement.

Streamline and reduce administrative reporting

Schools in North Macedonia spend considerable time preparing and submitting many administrative documents and data to the SEI. As well as distracting schools from their core role, some of the documents reported to the inspectorate are already reported to other parts of the ministry. For instance, schools provide inspection teams with data on retention rates and students’ attendance, information about the school principal and teacher. While this information is already available in the ministry’s Education Management and Information System (EMIS), but it is not shared with the SEI.

The SEI should simplify and digitalise the collection of administrative data as the majority of OECD countries have. (OECD, 2013[1]). The SEI should try to retrieve as much administrative data as it can (such as grade retention rates, school staff profiles and student attendance rates) directly from the EMIS database. The SEI should also work with the EMIS unit to ensure that administrative data needed for the evaluation are adequately reported and included in EMIS in the future (see Chapter 5). It is also recommended that the SEI stop requesting and collecting some documents produced specifically for the inspection and which do not provide valuable information about the quality of the school practices, such as minutes of school board meetings and teacher council meetings.

Revise classroom observations to focus on teaching and learning across the school

The individual teacher appraisals as part of school evaluations in North Macedonia play a limited role in supporting school improvement. Teachers do not receive written feedback or their scores from the classroom observation. Given the limited time available for observing all teachers, individual classroom observations are often very short, just ten minutes, during which inspectors will simply check documents such as students’ portfolios and lesson plans.

While the teacher appraisal component has no consequences for teachers’ career or salaries, teachers feel under pressure to perform well during the classroom observation. It even leads to some distortive teaching behaviour, such as only calling on the best students in the class to respond to questions, or providing students with the answers to the questions in advance.

The SEI should replace the individual teacher appraisals with more extended classroom observations of a sample of classrooms to gain a deeper understanding of instruction across the school. Inspectors should plan to visit a range of classrooms across different subjects and grades. The focus of these classroom observations would be to develop a general overview of teaching and learning across the school. Instead, individual teacher appraisals will be led by the school principal and the BDE (see Chapter 3).

Develop guidance on how to observe teacher practice and student-teacher interactions

The classroom observation protocol included in the evaluation handbook specifies expectations for inspectors’ conduct and the documents they need to look at. However, it does not help inspectors understand how to meaningfully observe teacher practice. The inspectorate should consider introducing a set of qualitative measures for classroom observations to help inspectors evaluate teaching practice in a structured way, since by its very nature, it is subjective and difficult to evaluate.

In this exercise, the inspectorate might draw on the classroom observation indicators developed by the International Comparative Analysis of Learning and Teaching (ICALT). The ICALT indicators are based on teaching and learning practices with a proven impact on student learning (see Box 4.2).

Box 4.2. Example of classroom observation indicators to evaluate the quality of teaching and learning

Guidelines should explain clearly the purpose of the classroom observation and list the indicators and descriptors that will be used. The International Comparative Analysis of Learning and Teaching (ICALT) was a collaboration among European external school evaluation bodies to develop an instrument to observe and analyse the quality of teaching and learning in primary schools.

The study found that the following five aspects could be compared in a reliable and valid way and that these were positively correlated with student involvement, attitude, behaviour and attainment: efficient classroom management, safe and stimulating learning climate, clear instruction, adaptation of teaching, and teaching-learning strategies. The final observation instrument was adopted for use by external school evaluation bodies in five European countries: Belgium (Flemish Community), Lower Saxony (Germany), the Netherlands, the Slovak Republic, and Scotland (United Kingdom). Below are a subset of the observation indicators:

|

Indicators |

Good practice descriptors |

|---|---|

|

Safe and stimulating learning climate (five indicators) |

|

|

The teacher ensures a relaxed atmosphere |

The teacher addresses the children in a positive manner The teacher reacts with humour and stimulates humour The teacher allow children to make mistakes The teacher demonstrates warmth and empathy towards all students |

|

The teacher shows respect for the students in behaviour and language use |

The teacher allows students to finish speaking The teacher listens to what students have to say The teacher makes no role-confirming remarks |

|

The teacher promotes the mutual respect and interest of students |

The teacher encourages children to listen to each other The teacher intervenes when children are being laughed at The teacher takes (cultural) differences and idiosyncrasies into account The teacher ensures solidarity between students The teacher ensures that events are experienced as group events |

|

The teacher supports the self-confidence of students |

The teacher feeds back on questions and answers from students in a positive way The teacher pays students compliments on their results The teacher honours the contribution made children |

|

The teacher encourages the students to do their utmost |

The teacher praises students for efforts towards doing their utmost The teacher makes clear that all students are expected to do their utmost The teacher expresses positive expectations to students about what they are able to take on |

|

Involvement of students (three indicators) |

|

|

There is good individual involvement of students |

The students are attentive The students take part in learning/group discussions The students work on the assignments in a concentrated and task-focused way |

|

Students are interested |

The students listen to the instructions actively The students ask questions |

|

Students are active learners |

The students ask deeper questions The students take responsibility for their own learning process The students work independently The students take initiatives The students use their time efficiently |

Source: (OECD, 2013[1]), Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment, OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264190658-en.

Recommendation 4.2.2. Make sure that integral evaluations deliver constructive feedback to schools

For school evaluations to lead to school improvement, they need to help schools understand what they do well, and where improvements can be made. At present however, schools in North Macedonia do not feel that evaluations help them to do this. The review team’s interviews revealed that schools largely perceive evaluation to be an externally imposed process that is disassociated from their own planning and development efforts.

This concern will be addressed by enhancing the SEI’s professional authority and capacity, and re-orienting the process to focus more centrally on school quality (Recommendations 4.1.1., 4.1.2. and 4.2.1.). However, another important dimension is ensuring that evaluations result in more useful, actionable feedback, complemented by greater follow-up support where necessary.

Improve the quality of feedback to schools

Precise and actionable feedback to schools following evaluations is important to help them understand their strengths, where improvement is needed and how to take action to achieve this (Faubert, 2009[24]). This is even more important in education contexts like North Macedonia where school leaders receive limited support – in terms of training or other support roles across the school – to become instructional leaders.

According to the SEI’s guidelines, the school report should include feedback to schools on the seven areas evaluated, highlighting strengths and weakness, and providing examples of good practices to help schools improve. These guidelines are in line with the approach to reporting results of external evaluations in OECD countries (OECD, 2013[1]). However, teachers reported to the review that they found that the report’s recommendations on teaching processes of little value.

The SEI might review the feedback that is provided to schools, to ensure that it is easily understood and useful. This might include reviewing a sample of reports nationally, conducting interviews with schools and looking at international practices. The review would result in recommendations for improvements in written and oral feedback. In the future, schools should continue to be surveyed periodically to make sure that reports are useful, with revisions made to the school report format as necessary.

Create a more meaningful follow-up process, focused on schools in greatest need of improvement

The SEI should consider reviewing the evaluation follow-up process so that schools with a “non-satisfactory” rating receive sufficient support. Currently, follow-up mainly plays a compliance function – to make sure that schools have implemented the evaluation’s recommendations. However, no external support is provided to help schools implement the recommendations. Moreover, the timing of the follow-up visit (six months after an evaluation) does not leave enough time to schools to put in place significant changes that may be necessary. Instead, the SEI should consider:

Gradually introducing a risk-based approach to evaluation and follow-up: meaningful follow-up is demanding in terms of technical expertise and time‑consuming. Given the limited resources available at the BDE and the municipal level, North Macedonia might consider introducing a risk-based approach to follow-up. Such an approach prioritises follow up with schools at greater risk of not meeting evaluation recommendations and low performance more generally. In North Macedonia, a result of “not satisfactory” in the integral evaluation might trigger follow-up for a school, while those that receive a “very good” grading do not. In the latter case, the SEI will simply check implementation of the recommendations during the next evaluation.

Replacing the follow-up visit with more continuous support: the SEI is too remote from schools to provide meaningful follow‑up. In most OECD countries, follow-up to external evaluation is not carried out by the external evaluator but by agencies closer to the school (see examples in Box 4.3). While municipalities in some countries perform this role, the very limited capacity of municipalities in North Macedonia (1-2 education officers per municipality) and their large number (81) make it unfeasible to provide support within each municipality. Instead, North Macedonia might consider establishing support improvement officers that work across multiple municipalities; developing a separate unit dedicated to school improvement within the inspectorate.

Box 4.3. Local follow-up to external evaluation in OECD countries

Wales (United Kingdom)

External evaluation in schools is conducted by Estyn, the Office of Her Majesty's Inspectorate for Education and Training in Wales. When a school is found not to be performing at the level defined in Estyn’s standards, the school may be classified into one of four categories. In three of the categories, Estyn itself monitors and revisits the school. In the fourth category, the classification for schools of least concern, schools are monitored by the local authority.

The local authority meets with Estyn every term and produces a report on the school’s progress in improving and implementing Estyn’s inspection recommendations. Estyn uses the report to decide on the extent to which Estyn itself must monitor the school. When Estyn has serious concerns about a school, local authorities are expected to intervene, as they are responsible for standards. For example, local authorities might address issues of staff performance and professional competence, school governance, resources and training.

Scotland (United Kingdom)

Education Scotland is responsible for conducting inspections of schools in Scotland. A school that is inspected will receive one of four ratings - innovative practice, no continuing engagement, additional support and further inspection ‒ each of which includes follow-up by local authorities :

In the case where Education Scotland identifies “innovative practice” in the school, Education Scotland works with the local authority to create a record of and disseminate the practice.

When a school receives the “no continuing engagement” designation, Education Scotland conducts no further follow-up visits in relation to this inspection and the local authority reports to parents on the progress of the school.

An “additional support” designation engages Education Scotland in providing support alongside the local authorities to improve the school.

If a school is in need of “further inspection,” Education Scotland, via an Area Lead Officer who oversees all scrutiny and capacity building activity in a particular local authority, will work with the local authority to identify the supports needed to improve the school. In this case, the Area Lead Officer monitors progress via the local authority and Education Scotland returns at a later date to evaluate progress and improvement.

Source: (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[6]), Assuring Quality in Education: Policies and Approaches to School Evaluation in Europe, The European Union, Luxembourg, https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/4a2443a7-7bac-11e5-9fae-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

Communicate and educate the school community on the purpose of school evaluation

Given the mistrust associated with school evaluation, and the distortive influence it has had on practices in some schools, the SEI should invest in communication materials to explain clearly its purpose teachers, other school staff, students and parents. For instance, the external school evaluation agency in England, United Kingdom, Ofsted, has developed a guideline called “Ofsted inspections: myths” that debunk some of the most common misconceptions about the inspection process (Ofsted, 2018[15]).

Similar brochures should be developed in North Macedonia and given to schools. They should address clearly a number of common concerns by clearly explaining for example that: school evaluation carries no consequences for individual teachers; no information on individual teachers, classes or students is made publicly available in the report; and that the school evaluation results cannot directly lead to a school principals’ dismissal.

Policy issue 4.3. Developing schools’ capacity to carry out meaningful self‑evaluation

While most schools in North Macedonia undertake regular self-evaluations and develop school action plans, few have appropriated these processes as internal tools to improve the quality of their practices. An overriding reason is that the improvement function of school evaluation is not well embedded in the country. Steps to professionalise the inspectorate and create a national vision of a good school will engage schools in a conversation about what school evaluation means, and its role for school improvement (see Recommendation 4.1.1.).

The above will need to be accompanied by more practical steps to provide schools with greater support for self-evaluation. At present, school actors with a leading role in self‑evaluation in schools do not receive any training or guidance to implement an effective self-evaluation process that is embedded in school planning activities. Steps also need to be taken to develop principals’ capacity to become instructional leaders in schools. Principals play an essential role in engaging the whole of a school community in self-evaluating and galvanising the school behind the self-evaluation process.

Recommendation 4.3.1. Provide support and training for school actors on self‑evaluation

There needs to be greater national investment in improving school-level capacity for self‑evaluation, and helping to develop a culture of improvement in schools. This will include more practical guidance for schools – through self-evaluation guidance and by promoting the exchange of good practices across schools. Actors with a key role in self‑evaluation ‒ school principals, boards and teachers – need far more support and training so that they can undertake their roles effectively.