This chapter discusses return migration to Romania, starting with an analysis of return intentions of Romanian emigrants in OECD countries, and focusing more particularly on the Italian case. After a brief review of the institutional context of Romanian emigration and return, and especially the role of free movement in the European Union, estimates of the number of return migrants to Romania are provided, looking both at stock and flow data. The demographic characteristics of Romanian return migrants are analysed, as well as their educational attainment. Their economic contribution is also discussed, looking both at their integration on the labour market and their role as entrepreneurs. A discussion of remittances sent by emigrants to Romania concludes.

Talent Abroad: A Review of Romanian Emigrants

Chapter 5. Return migration to Romania

Abstract

This chapter discusses return migration to Romania, starting with an analysis of return intentions of Romanian emigrants in OECD countries, and focusing more particularly on the Italian case. After a brief review of the institutional context of Romanian emigration and return, and especially the role of free movement in the European Union, estimates of the number of return migrants to Romania are provided, looking both at stock and flow data. The demographic characteristics of Romanian return migrants are analysed, as well as their education distribution. The economic contribution of the diaspora is also discussed, looking at the integration of return migrants on the labour market, their role as entrepreneurs, as well as the remittances sent home by Romanian emigrants.

Return intentions among Romanian emigrants

According to the Gallup World Poll, about 26% of Romanian emigrants living abroad, surveyed between 2009 and 2018, considered moving to a different country, while 70% wanted to remain in their current country of residence (the remaining 4% have not responded to the question). This proportion was higher among those who had arrived in their destination country in the last five years, with 35% saying that they intended to leave, versus 23% among those who had been abroad for longer. Among those having indicated their wish to leave their current country of residence outside Romania, only about one‑third indicated that they would like to return to Romania, while about 10% said they would like to move to the United States (8% mentioned the United Kingdom, 7% Canada, 5% Germany or Spain).

Focusing on some of the main destination countries of Romanian emigrants provides additional insights. Among Romanian emigrants living in Spain in 2006, the National Immigrant Survey indicated that fewer than 10% intended to return home within the next five years, while more than three‑quarters wanted to stay in Spain, and more than 10% stated that they did not know what they would do. For Italy, which is one of the top destination countries of recent Romanian emigrants, the survey “Social Condition and Integration of Foreign Citizens” (2011‑12), shows that, at the time of the survey, about 32% of the Romanian respondents intended to return to their country of origin, while 66% wanted to remain in Italy indefinitely (Bonifazi and Paparusso, 2018[1]).

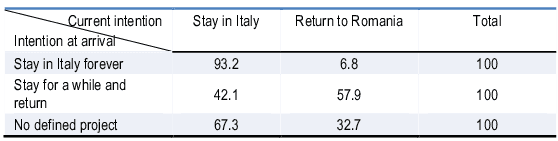

As shown in Table 5.1, these answers differed somewhat from their initial intentions. Among the respondents who stated that their intention at arrival was to stay in Italy forever, about 93% indicated that their current intention was to stay, while only 7% had changed their mind and stated that they intended to return. On the contrary, among those who stated that they initially planned to stay for some time in Italy and then return to Romania, more than 40% said that they now planned to stay in the country. Finally, among those who were not sure to stay when they arrived, one‑third had decided to remain in Italy.

Table 5.1. Current intentions of Romanian emigrants to stay in Italy or return to Romania, by intention at arrival, 2011‑2012 (in %)

Source: Survey “Social Condition and Integration of Foreign Citizens”, 2011‑‑12, Istat.

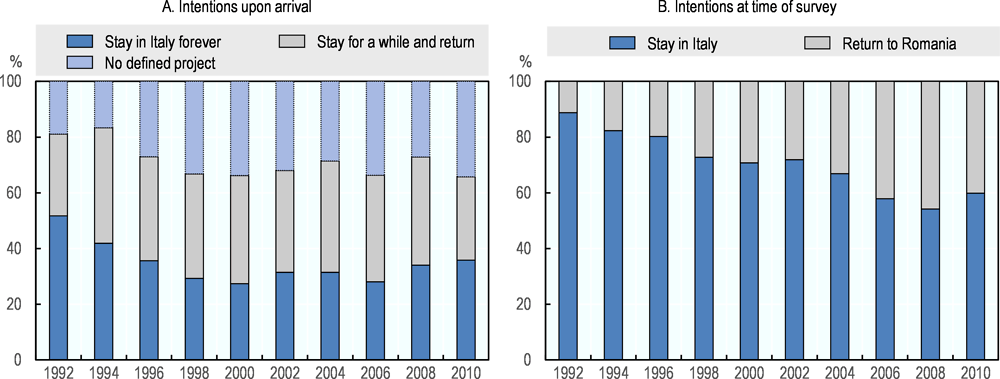

These results indicate that a number of Romanian emigrants change their mind over time and become more and more inclined to remain in Italy. Although results are partly driven by selection1, comparing return intentions across years of arrival in Italy shows that a substantial number of Romanian emigrants who initially intended to return finally decided to stay in Italy (Figure 5.1). For example, among those who arrived in the early 2000s and who were still living in Italy 10 years later, less than one‑third stated that they initially wanted to stay, while 70% said that their current intention was to stay.

Among those who intended to return to Romania, leaving Italy was a short‑term prospect (departure in two years or less) for only 10%, but this proportion varied significantly according to the time already spent in the country: those who had just arrived were more likely to say that they would leave quite soon.

Figure 5.1. Intentions of Romanian emigrants upon arrival and at the time of the survey (2011‑12), by year of arrival in Italy (%)

Source: Survey “Social Condition and Integration of Foreign Citizens”, 2011‑12, Istat.

A quantitative analysis of the same Italian survey indicates that several demographic, social and economic factors influence the return intentions of Romanian emigrants living in Italy. A first key determinant is gender: all else equal, men are more likely than women to say that they would like to return to Romania. Older emigrants also tend to have higher return intentions, even after controlling for the year of arrival (as noted above, recent emigrants are much more likely to say they want to return to Romania than those who came earlier). Compared to respondents with no children, those who only have children living with them are less likely to say they want to return to Romania, while those who have at least one child living separately, including in Romania, are more likely to say they would return. Respondents with the lowest levels of education are those expressing the lowest return intentions, but Romanian emigrants with a tertiary degree have similar return intentions as those with only secondary education. People currently in employment state more frequently that they intend to return to Romania. Finally, the experience of discrimination in Italy – in the labour market, for access to housing, or in daily life – is also a significant predictor of return intentions.

As discussed by De Coulon et al. (2016[2]), in the case of Italy, there has also been a significant effect of anti‐immigrant attitudes on the intended duration of stay of Romanian emigrants in the host country, especially for low‑skilled ones.

Characteristics of Romanian emigrants who returned to Romania

Accession of Romania to the European Union has made return migration easier, but also more difficult to measure

Romania joined the European Union in 2007. From this date, Romanian citizens benefited from free movement, but many EU countries opted to have a transition period before applying freedom of movement for Romanian workers2. Among the countries which implemented a transition period, some applied freedom of movement for Romanian workers in 2009, but many countries applied it as late as 2014. This was for example the case of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Italy lifted restrictions to the mobility of Romanian workers in 2012. Spain initially opened its labour market to Romanian workers in 2009, but then used a safeguard clause to restrict movement between 2011 and 2014.

Accession to the European Union and the establishment of free mobility for Romanian nationals facilitated their emigration towards other European countries, but also their return to Romania, leading to more frequent and more temporary stays abroad. Freedom of movement for workers further facilitated working abroad in other EU Member States and probably reinforced this trend towards increasing mobility. Repeat migration, and more complex mobility patterns across several EU countries, are therefore likely to have become more common in recent years (Ciobanu, 2015[3]). This makes it more difficult to identify and enumerate return migrants with standard data sources. First and foremost because few EU countries track adequately the exits of nationals from other Member States, but also because return migrants are less likely to be captured in surveys if they stay in their country of origin for only a short time before moving again. This difficulty in measuring temporary migration within the European Union obviously does not concern only Romanian emigrants, but applies to all EU countries. Considering the magnitude of the gross flows of Romanian nationals towards other EU countries in the recent years, this issue is however particularly significant in the Romanian case.

In 2015‑17, at least 160 000 Romanian emigrants returned to Romania each year from European OECD countries

Existing estimates indicate that return migration is very prevalent in Romania: according to Ambrosini et al. (2015[4]), return migrants represented about 7% of the population aged 24‑65 in 2002‑04, corresponding to about 820 000 individuals. For 2008, Martin and Radu (2012[5]) estimate that the share of return migrants had risen to almost 8% of the population aged 24‑65, or about 900 000 individuals in this age range. This suggests a 10% increase in the number of returnees in Romania in just five years, highlighting the dynamics of this phenomenon.

The number of return migrants can be apprehended either through outflows from destination countries of nationals going back to their origin country, or through the number of nationals who state in a census or representative survey in the origin country that they have lived abroad in the past. In the case of Romanian returnees, relevant information, albeit limited, can be obtained by exploiting these two types of sources.

The most recent Romanian census was conducted in 2011; it is therefore too old to include the Romanian emigrants who have returned in recent years. In addition, the questionnaire does not allow adequate identification of return migrants: it only asks about the most recent previous residence, whether in Romania or abroad. As a result, return migrants having changed their locality of residence in Romania after coming back in the country cannot be identified as return migrants. This severely limits the overall number of return migrants which can be counted. Since emigrants who have returned shortly before the census are less likely to have had the opportunity to change residence, it can be thought that the census can at least provide a reasonable estimate of the number of Romanian emigrants who returned in the previous two years. Considering the existing estimates discussed above and the magnitude of the flows from some of the main destination countries (see below), the estimated number, only 3 200 Romanian emigrants having returned between 2009 and 2011, appears excessively small and quite improbable. For this reason, the 2011 census is not used in analyses carried out in this chapter.

Another source of information on emigrants who have returned to Romania is the 2014 EU labour force survey, which included a specific module on migration. The survey asks respondents whether they have worked and lived abroad, for a period of six months or longer, in the last ten years. Combining this information with country of birth and citizenship allows identification of 385 000 Romanian nationals aged 15‑64 living in the country in 2014 and who had lived abroad in the previous 10 years3. This figure is however probably a lower bound on the actual number of return migrants, because people who have lived abroad without being employed may not have responded positively to the question. This could include for example students, people who did not manage to find a job abroad, but also inactive accompanying family members of people working abroad.

While it is unfortunately not possible to know exactly when those return migrants came back to Romania, their most recent former country of residence abroad is known. The five main countries were Italy (220 000 return migrants), Spain (73 000), Germany (38 000), Hungary (12 000) and France (6 600). Together, these countries accounted for 90% of the total number of return migrants, with Italy alone representing 57%. Returns from non‑European countries, especially from the United States and Canada – which account for 8% of the Romanian diaspora in OECD countries – were negligible.

Data on outflows of foreigners collected by some countries can be used to estimate the magnitude of return migration. In the case of Romanian emigrants, three of the main countries of origin – Italy, Germany and Spain – release statistics on outflows of foreigners, which originate from population or foreigners registers. A key issue with register data on outflows is whether emigrants actually report their departure and what incentives or obligations they have to do so. Each country has specific rules regarding deregistration and figures may not be comparable from one country to the other. Register data are nevertheless very useful to account for changes in outflows over time.

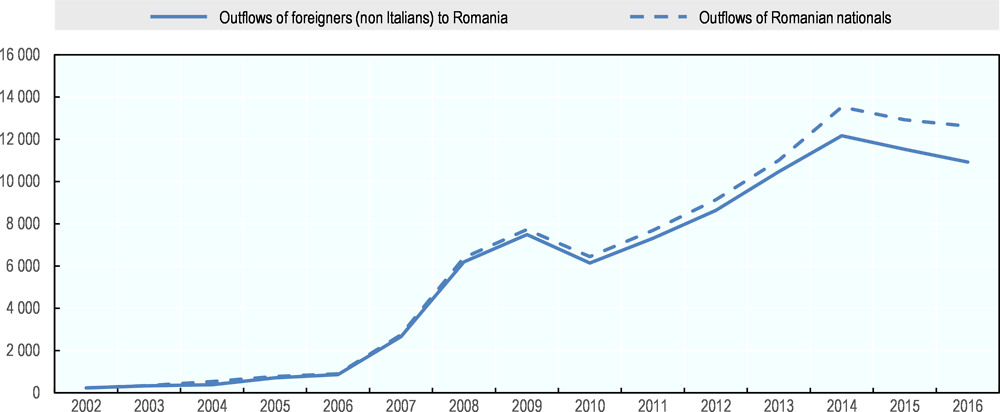

According to the Italian register statistics, outflows from Italy to Romania of non‑Italian nationals amounted in 2016 to about 11 000 departures, with a slight decline in the recent years (Figure 5.2). Since there is little reason to expect significant flows of migrants with other nationalities from Italy to Romania, it can be assumed that virtually all those captured here are Romanian return migrants4. Outflows were negligible in the early 2000s and started to increase significantly in 2007, coinciding with the accession of Romania to the European Union and the very large inflows towards Italy witnessed that year (see Chapter 2). They reached a first peak in 2009, and increased again significantly between 2010 and 2014. A similar pattern is observed for departures of Romanian nationals from Italy (to any destination), suggesting a strong overlap between the two series, although the level is slightly higher, with about 13 000 departures in 2016.

Compared to data on inflows to Italy of non‑Italian nationals from Romania (or overall inflows of Romanian nationals) from the same source, the ratio of outflows to inflows has strongly increased in the recent years, from 1% on average in 2002‑06 to 7% in 2009 and to 25% in 2014‑16 (i.e. one departure for four arrivals in Italy). This trend reflects the increasing mobility of Romanian nationals in the EU area discussed above.

Figure 5.2. Outflows from Italy of foreigners towards Romania, and outflows from Italy of Romanian nationals, 2002‑16

Note: Outflows are measured by cancellations from the population registers.

Source: Instituto Nazionale di Statistica, Italy.

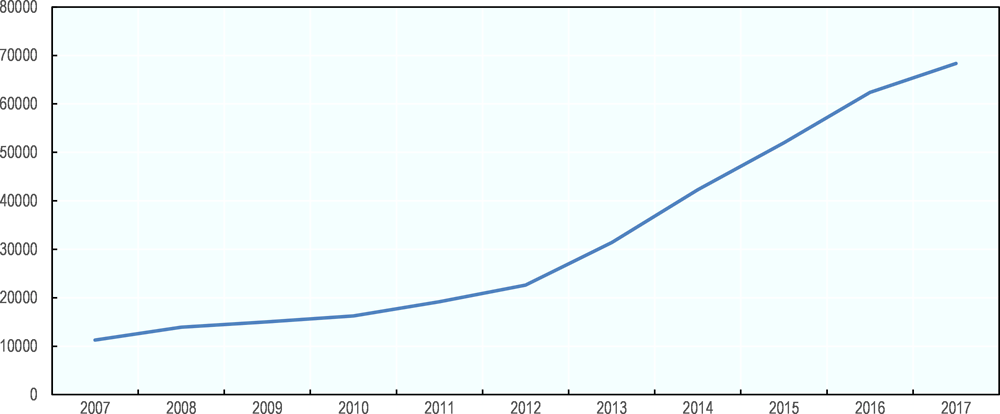

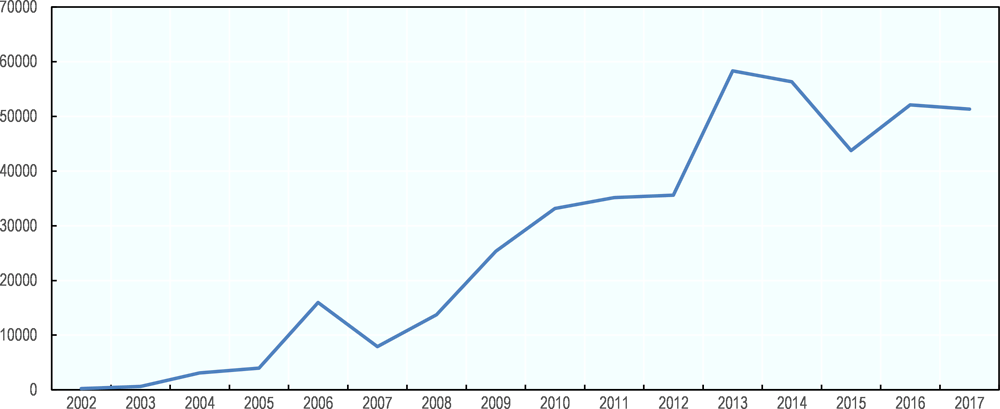

In the case of Germany, for which data is only available since 2007, outflows of Romanian nationals have reached almost 70 000 departures in 2017, while they were six times smaller 10 years earlier. They have initially increased quite slowly, before accelerating in 2013‑14. Since then, the growth has remained positive, but has slowed down significantly (Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3. Outflows of Romanian nationals from Germany, 2007‑17

Source: Register.statistics, Destatis, Germany.

Comparing these outflows to the inflows of Romanian nationals to Germany reveals that the retention rate is much lower than in Italy: the ratio of outflows to inflows has indeed averaged about one‑third over the period 2007‑17. Additional data on the average length of stay of Romanian nationals leaving Germany between 2007 and 2017 shows that about 36% of them have remained in the country for less than one year, a share that has remained stable throughout the period.

In Spain, data from the population registers are used by the Spanish National Statistics Institute to estimate residential variations, including from and to foreign countries. Although information is theoretically available on the country of destination of those leaving Spain, it is actually left blank for most cases, which requires looking at total departures, instead of departures to Romania. In 2017, outflows of Romanian nationals amounted to about 51 000 departures, more than the inflows of Romanians the same year, leading to a negative net migration which has persisted since 2012 (see Chapter 2). Outflows have however diminished compared to the peak observed in 2013, where more than 58 000 Romanians left Spain (Figure 5.4).

Just as for Italy, the ratio of outflows to inflows was very small in 2002‑05, averaging 2%. It increased however much more quickly than in Italy, reaching 19% in 2008 and 60% in 2011, before reaching 200% in 2013. It has since diminished and was close to 130% in 2017.

Figure 5.4. Outflows of Romanian nationals from Spain, 2002‑17

Source: Estadística de variaciones residenciales, Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Spain.

Overall, outflows of Romanian emigrants from Italy, Germany and Spain have increased considerably in the last 15 years. A striking result is the much larger number of returns from Germany and Spain than from Italy, despite the fact that, in 2015/16, the population of Romanian emigrants in Italy was 1.5 times larger than in Germany and 1.8 times larger than in Spain. This is also at odds with the much larger number of return migrants from Italy identified in the 2014 Romanian EU labour force survey, compared to those who had come back from Spain or Germany. It is therefore likely that the Italian register fails to capture a significant number of departures of Romanian emigrants.

Despite this limitation, assuming that the registers from these three countries generate comparable enough figures, it can be estimated that, on average between 2015 and 2017, approximately 135 000 Romanian emigrants have returned to Romania each year from these countries. These three countries hosted two‑thirds of all Romanian emigrants in European OECD countries in 2015/16, but represented 85% of all return migrants identified in the 2014 Romanian EU labour force survey. Using these shares as upper and lower bounds to the actual share of these three countries in total return migration flows to Romania, one can estimate that the total yearly number of Romanian return migrants has ranged between at least 160 000 and 200 000 in recent years, although this does not account for a potential under‑declaration of departures from Italy.

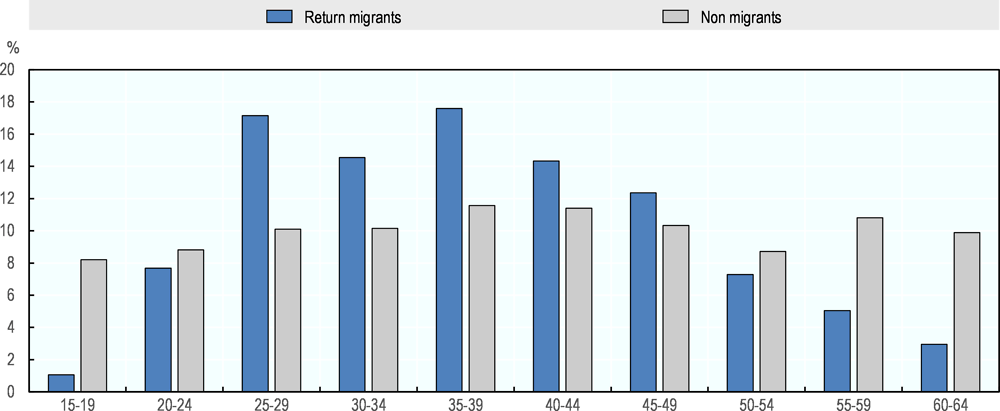

Romanian return migrants are much younger than non‑migrants

The age distribution of return migrants is quite different from that of non‑migrants who have always remained in Romania. According to the 2014 EU labour force survey of Romania, among the Romanians (aged 15‑64) who have worked and lived abroad at some point in the period 2004‑14 and then returned to Romania, 63% were aged between 25 and 44, while the same age group represented only 43% of the non‑migrants (Figure 5.5). This age distribution is even more skewed than that of the diaspora itself, where 54% of the 15‑64 years old were in the 25‑44 age group in 2015/16.

Comparing emigrants having returned from the three main destination countries (Italy, Germany and Spain), Germany stands out as the one with the youngest return migrants, with almost 40% of the 15‑64 being aged 20‑29, while this share is only 24% among those having returned from both Italy and Spain. This is consistent with the previous finding that Romanian emigrants remain in Germany for shorter periods than they do in Italy and Spain.

Figure 5.5. Age distribution of return migrants and non‑migrants aged 15‑64 in Romania, 2014

Source: Romania EU labour force survey, 2014, Eurostat.

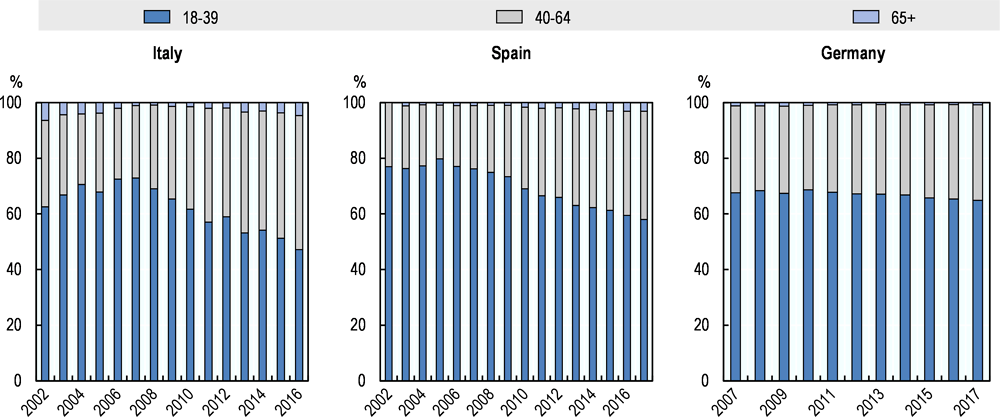

Looking directly at the age distribution of return flows of Romanian emigrants from Italy, Germany and Spain, using population registers data, the overall picture is similar: among adult (18+) return migrants, a majority are aged between 18 and 39 years old (Figure 5.6). On average, the share of this age group was 62% in Italy (2002‑16), 70% in Spain (2002‑17) and 67% in Germany (2007‑17). For all three countries, return migrants aged 65 years old and over were rare: about 3% in Italy, 1.5% in Spain and less than 1% in Germany. There has been, however, a trend towards a decreasing share of young return migrants from Italy and Spain since 2007, while this is much less the case for emigrants coming back from Germany. In 2007, those aged 18‑39 represented 73% of all 18+ return migrants from Italy, while this share dropped to 47% in 2016. For those coming back from Spain, the trend has been similar, although less marked: those aged 18‑39 represented 77% of the total in 2007 and 58% in 2017. In contrast, for Germany, the share of the 18‑39 has remained more stable: 67% in 2007 and 65% in 2017.

Figure 5.6. Age distribution of return migrants aged 18+ from Italy, Spain and Germany

Source: Instituto Nazionale di Statistica, Italy; Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Spain; Destatis, Germany.

For Italy and Spain, there are also signs of an increasing share of individuals aged 65 years old and over among return migrants, although they remain a very small number. Among return migrants from Italy, individuals aged 65 years old and over made up less than 5% of the total in 2016, but this share was only 1% in 2007‑08. For Spain, the share is still small as well, 3% in 2017, but increasing from about 1% in 2007. While retirees make up a significant share of return migration flows in other European countries, this is not currently the case in Romania, as return migration is dominated by emigrants who stay abroad temporarily before returning to Romania (and maybe leaving again later on). While there is a large number of Romanian emigrants who follow this pattern, there is an even larger number of them who settle more durably in OECD countries, including in countries where many Romanians stay only temporarily, such as Germany. It remains to be seen whether those emigrants will finally return to Romania when they retire, but even if a relatively modest fraction of them do, this may generate significant flows of retiring return migrants to Romania in 10 to 20 years.

The share of women is higher among migrants returning from Italy than from Germany and Spain

According to the 2014 Romanian EU labour force survey, among Romanians who have worked and lived abroad at some point between 2004 and 2014 before returning, only 35% were women. This is as strikingly low share, as women represented almost 50% of the 15‑64 population of Romanian nationals, and about 54% of the 15‑64 population of Romanian emigrants in OECD countries in 2015/16. This gender imbalance was slightly less acute among former emigrants who had returned from Italy (40% of women), but was more pronounced among those returning from Spain (31% of women), Germany (22%) and Hungary (18%). This underrepresentation of women is probably partly because only return migrants having worked abroad are considered here. Indeed, as shown in Chapter 4, the employment rate of Romanian emigrant women in OECD countries was only 63% in 2015/16, compared to 77% for men. Accounting for these employment rates, and assuming that gender differences in return behaviour are not significantly affected by the employment status of emigrants during their stay abroad, the share of women among return migrants would be close to 40%5. An additional explanation for this lower representation of women among return migrants would be that they have a lower propensity to return than men.

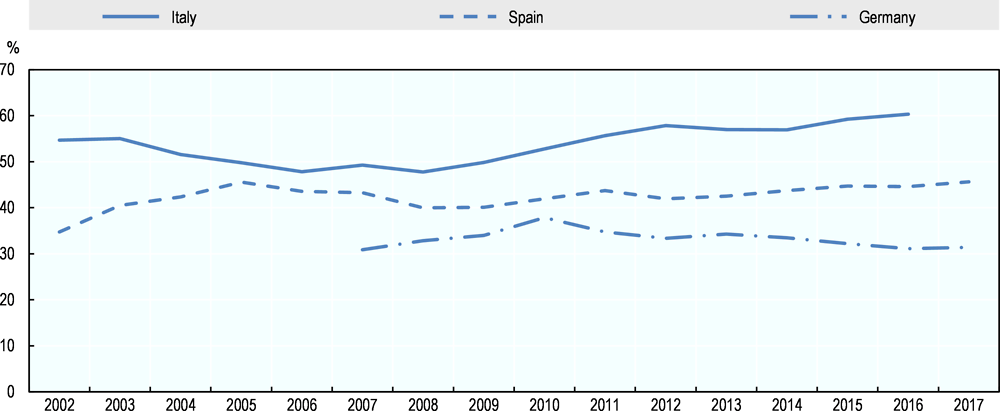

However, the data on flows of return migrants from Italy, Germany and Spain paint a quite different picture. As shown in Figure 5.7, among return migrants coming back from Italy, women have made up a majority of the flows since 2010 and their share has increased to 60% in 2016. In contrast, women are a minority among return migrants from Spain and Germany, with respectively 46% and 31% of the flows in 2017. In Spain, the share of women has increased in the last 10 years (from 40% in 2008‑09) while it has been decreasing in Germany (from 38% in 2010).

Figure 5.7. Share of women among Romanian return migrants from Italy, Spain and Germany, 2002‑17

Source: Instituto Nazionale di Statistica, Italy; Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Spain; Destatis, Germany.

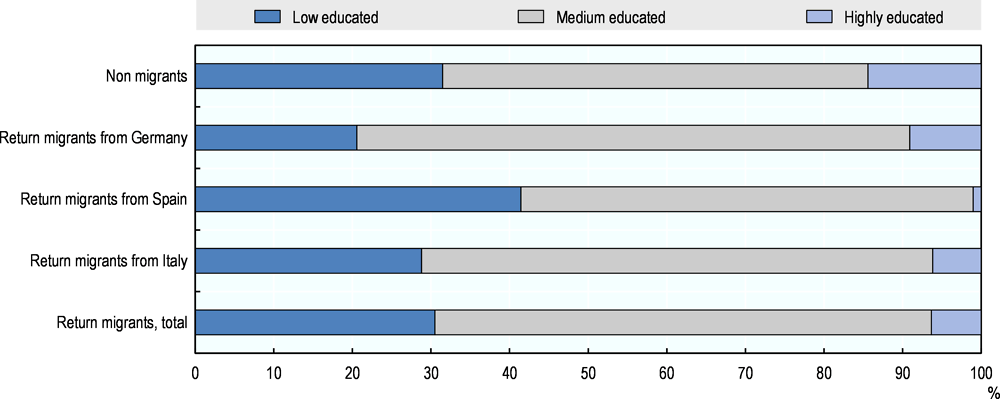

Romanian return migrants have on average lower levels of education than non‑migrants and those who stayed abroad

While Romanian emigrants living in OECD countries tend to be better‑educated than the Romanian population in general, this is not the case for return migrants, who are, on average, both less educated than those who have remained abroad and less educated than those who have not left Romania. Due to the concentration of lower‑educated emigrants in European destination countries, especially those that are relatively close, those lower‑educated Romanian emigrants are also more likely to return. Data from the 2014 Romanian EU labour force survey show that less than 7% of return migrants report having a tertiary education, while this share is twice as large among non‑migrants (Figure 5.8).

While migrants returning from Italy have a distribution of education that is close to that of the overall return migrant population, those returning from Germany have a higher share of medium and highly educated, while those returning from Spain have a very high share of low educated and a much smaller share of tertiary educated. Compared to Romanian emigrants who were still abroad in 2015/16 (see Chapter 3), those who have returned are much less likely to have a tertiary degree, except for return migrants from Italy, where the share of tertiary educated is quite similar (6% among return migrants, versus 7% for those still abroad). While only 9% of Romanian emigrants returning from Germany are tertiary educated, the share among those still in Germany in 2015/16 was 23%. In the case of Spain, the gap is even larger: barely 1% of the return migrants had a tertiary degree, while 17% of those living in Spain had one.

Romanian emigrants coming back from Spain and Germany are therefore quite strongly negatively selected, while this does not seem to be the case for those returning from Italy. In the case of Spain, recent return migration was mostly motivated by the poor employment prospects in the country, where unemployment has been very high since 2009, especially for low‑educated immigrants. In fact, the employment rate of low‑educated Romanian emigrants in Spain has dropped catastrophically between 2005 and 2010, from 70% to 40%. This has not been the case in Italy, where the employment rate of this group has remained roughly stable over this period, at 57%. Romanian emigrants with higher levels of education have also seen their employment prospects drop significantly between 2005 and 2010, but not as strongly as the low educated.

The case of Germany is more complex because of the prevalence of seasonal and temporary migration among low‑educated Romanians, while those with higher levels of education have tended to settle more durably (Anghel et al., 2016[6]).

Figure 5.8. Distribution of education of return migrants and non‑migrants aged 15‑64 in Romania, 2014

Source: Romania EU labour force survey, 2014, Eurostat.

Economic contributions of Romanian emigrants

Romanian emigrants contribute in many ways to the economic development of their country of origin, particularly through the supply of labour and skills, but also by returning to Romania and settling there. While some mechanisms – such as the supply of skilled labour, entrepreneurship and knowledge transfer – normally require Romanian emigrants to return to Romania at least temporarily, they may also have a positive influence from abroad through mechanisms such as remittances, trade and business networks. This section presents available data on some of the main mechanisms by which emigrants can contribute to the development of Romania, but also the obstacles they may face.

Prime‑age and highly educated return migrants face difficulties to reintegrate the Romanian labour market

Although reintegration in the country of origin is a multifaceted process, the economic dimension is primordial and will often condition other dimensions of returnees’ well‑being. For those of working‑age, access to employment is critical. A substantial literature has been devoted to the determinants of return migration, and employment prospects in the origin country figure prominently as one the key drivers of return (see OECD (2008[7]) for an extensive review). This is especially true when emigration itself was largely motivated by economic reasons, as is the case for the recent Romanian emigration towards OECD countries (see Chapter 1).

The labour market situation of Romanian return migrants can be analysed using the 2014 Romanian EU labour force survey. As discussed above, this survey documents the previous country of residence of Romanians who have come back to the country in the previous 10 years. Looking at their employment outcomes in 2014 therefore provides a medium‑term outlook of their reintegration on the labour market.

In addition, pooling the Romanian EU labour force surveys of 2015, 2016 and 2017, it is also possible to look at the short‑term reintegration of Romanian returnees. Indeed, these surveys include a question on the country of residence one year before. Although these surveys are not designed to provide estimates of the number of recent returnees – in particular because people who have arrived in the country very recently are much less likely to be sampled – they can still provide relevant insights on the labour market outcomes of those recent returnees.

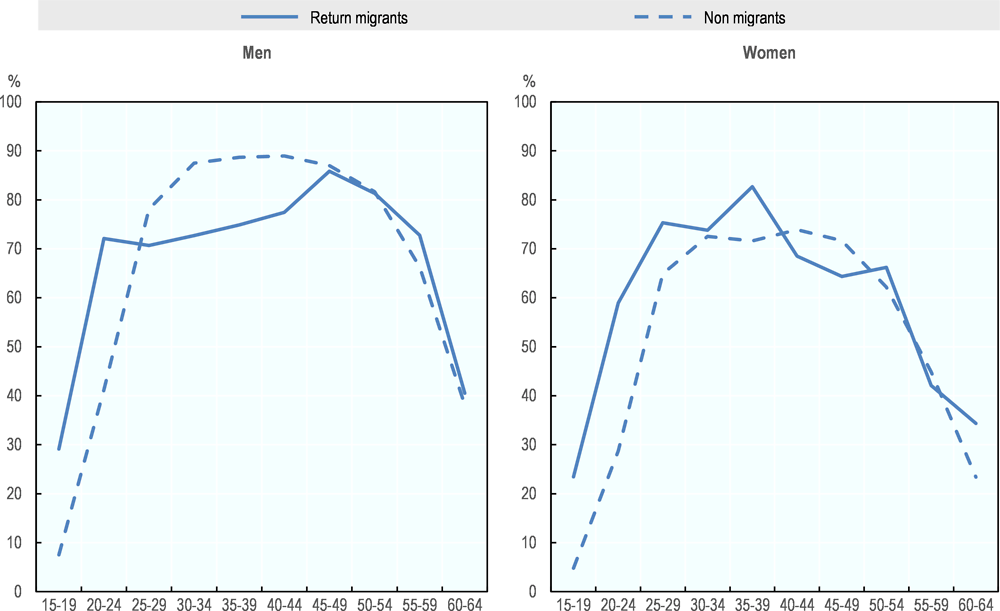

At first glance, it appears that return migrants have better employment prospects than non‑migrants. Indeed, in 2014, the employment rate of return migrants aged 15‑64 who have come back to Romania in the previous 10 years was 69%, while that of the non‑migrants Romanian nationals was only 61%. This was also true in 2015‑2017 for return migrants (also aged 15‑64) who were just returning and were abroad the year before: their employment rate was even higher at 73%, while only 62% of the non‑migrant Romanians had a job. Looking separately at men and women provides similar results: with the medium‑term perspective (i.e. with the 2014 survey) the employment gap between return migrants and non migrants was four percentage points among men and 10 percentage points among women. The short‑term outcomes of return migrants were qualitatively similar, with an employment gap of eight points in favour of return migrants among men, and 12 points among women.

There is, however, a strong composition effect due to age differences between return migrants and non‑migrants. As noted above, return migrants are on average much younger than non‑migrants, and the employment rate among the 15‑24 is much higher for return migrants than for non‑migrants, many of whom are still in education. Among prime‑age men (25‑49), return migrants suffer from a significant disadvantage compared to non‑migrants, with employment rates almost 15 points lower for those aged 30‑39. In comparison, women returnees fare much better: their employment rate is higher than that of non‑migrants in almost all age groups, except from 40 to 49 years old (Figure 5.9). A similar picture emerges when looking at the age profile of employment rates for short‑term return migrants: those aged 20‑29 have higher employment rates than non‑migrants, but those aged 35‑54 are less often in employment than the non‑migrants.

Figure 5.9. Employment rates of return migrants and non-migrants by age and sex in Romania, 2014

Note: Return migrants are defined as Romanian nationals born in Romania who have been working and living abroad at some point in the 10 years prior to the survey. Non‑migrants are Romanian nationals born in Romania who have remained in Romania in the 10 years prior to the survey.

Source: Romania EU labour force survey, 2014, Eurostat.

There are also significant differences in the pattern of employment rates between return migrants and non‑migrants with respect to educational attainment (Table 5.2). Among low‑educated individuals, the employment rate of medium‑term return migrants is 20 percentage points higher than that of non‑migrants, which again is partly due to the age difference between the two groups. For individuals with medium education, the gap is lower but still in favour of return migrants. In contrast, tertiary educated return migrants fare worse than their non‑migrant counterparts, with an employment rate gap of almost eight points. In fact, while tertiary education is associated with a gain of 18 points in employment rate among non‑migrants (compared to medium educated people), the gain is only four points among returnees. Although the small sample size prevents drawing strong conclusions, a similar pattern seems to emerge for short‑term return migrants: while those with low and medium education have larger employment rates than non‑migrants, those with tertiary education seem to do much worse and they actually also do worse than lower educated return migrants.

Table 5.2. Employment rates of return migrants and non‑migrants by educational attainment in Romania, 2014 and 2015‑2017

|

2015‑17 |

2014 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Short-term return migrants |

Non-migrants |

Medium-term return migrants |

Non-migrants |

|

|

Low educated |

71% |

42% |

65% |

45% |

|

Medium educated |

78% |

66% |

71% |

65% |

|

Highly educated |

55% |

87% |

75% |

83% |

Note: In 2015‑17, short-term return migrants are defined as Romanian nationals born in Romania who were living abroad one year before the survey. Non‑migrants are those who were living in Romania one year before the survey. In 2014, medium‑term return migrants are defined as Romanian nationals born in Romania who have been working and living abroad at some point in the 10 years prior to the 2014 survey. Non‑migrants are those who have remained in Romania in the 10 years prior to the survey.

Source: Romania EU labour force surveys, 2014 and 2015‑17, Eurostat.

A more complete picture is obtained with a multivariate analysis of the correlates of employment in the 2014 survey. Controlling for sex and age, return migrants with low education enjoy an employment rate that is significantly higher than that of their non‑migrant counterparts, with a difference of seven percentage points. In contrast, highly educated return migrants have a disadvantage over non‑migrants, with a significant negative difference of nine percentage points6.

To sum up, although aggregate employment rates are higher for return migrants than for non‑migrants, specific categories are at a disadvantage and do not seem to reintegrate very well. The first group is prime‑age men, who may have difficulties competing for jobs with non‑migrants who have accumulated more experience on the Romanian labour market. This raises the question of the transferability of experience and skills acquired abroad. In particular, if the technology or management practices of Romanian firms are too different from that of firms in destination countries of Romanian emigrants, it may prove difficult for them to fully use their skills in Romania.

Another group of return migrants that has relatively poor reintegration outcomes is the highly educated. They have higher employment rates than low and medium educated returnees, but they do not fare as well as highly educated non‑migrants. While some of them may have obtained their tertiary degree abroad, there are not the majority, considering the small number of Romanians enrolled in higher education in OECD countries. Issues with the recognition of foreign qualifications by Romanian firms are therefore unlikely to be a major cause of the situation of highly educated return migrants. A potential explanation is the lack of a reliable network to help them find a job, or the loss of country‑specific knowledge during the stay abroad. It is also possible that those highly educated return migrants are negatively selected on unobserved characteristics: among the highly educated Romanian emigrants, if only those who have the highest motivation and abilities manage to find a job in OECD destination countries, those who are unsuccessful will return. This is in fact consistent with earlier findings in the literature (Ambrosini et al., 2015[4]; de Coulon and Piracha, 2005[8]).

Entrepreneurship and occupations of return migrants: Choices or constraints?

Beyond access to employment, the qualitative dimension of labour market reintegration also matters to evaluate the economic contribution and social prospects of return migrants in Romania. This includes in particular the type of activity undertaken by return migrants, in terms of both entrepreneurship and occupations.

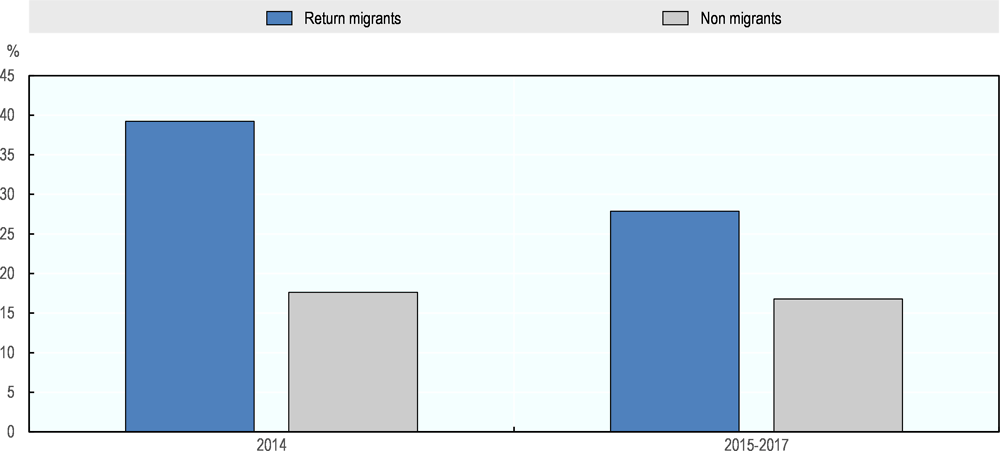

Entrepreneurship – or self‑employment – is a widespread activity among migrants in OECD countries and contributes significantly to job creation (OECD, 2010[9]). Its role among return migrants has also been largely discussed in the literature (Marchetta, 2012[10]; Piracha and Vadean, 2010[11]; Dustmann and Kirchkamp, 2002[12]). In the case of Romania, using data from the mid‑2000s, Martin and Sandu (2012[5]) find that return migrants are not more likely to become self‑employed than non‑migrants. However, data from the 2014 and 2015‑17 Romanian EU labour force surveys show that the share of entrepreneurs or self‑employed is significantly higher among return migrants than among non‑migrants (Figure 5.10). This result persists for 2014 after controlling for age, sex and education: the share of self‑employed is 13 percentage points higher among low educated return migrants than among low educated non‑migrants. The difference is smaller for the medium educated and not significantly different from zero for the highly educated. For short‑term return migrants in 2015‑17, there is no significant difference in self‑employment among the low educated, compared to non‑migrants. There is, however, a significant difference for the medium educated.

Overall, among return migrants, those with a low level of education are more likely to be self‑employed or entrepreneurs: in the 2014 labour force survey, the share of self‑employed or entrepreneurs among low‑educated return migrants was about 50%, while it was 20% among those with higher education.

Figure 5.10. Share of entrepreneurs and self‑employed among return migrants and non‑migrants in Romania, 2014 and 2015‑17

Note: In 2015‑17, short‑term return migrants are defined as Romanian nationals born in Romania who were living abroad one year before the survey. Non‑migrants are those who were living in Romania one year before the survey. In 2014, medium‑term return migrants are defined as Romanian nationals born in Romania who have been working and living abroad at some point in the 10 years prior to the 2014 survey. Non‑migrants are those who have remained in Romania in the 10 years prior to the survey.

Source: Romania EU labour force surveys, 2014 and 2015‑17, Eurostat.

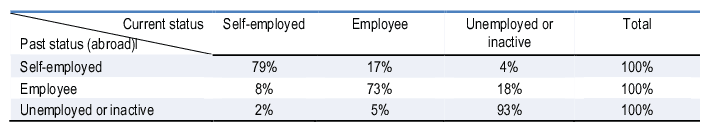

In addition to the country of residence one year before, the 2015‑17 labour force surveys also ask about the previous employment status. It is therefore possible to analyse to what extent self‑employed return migrants were already self‑employed abroad. Table 5.3 and Table 5.4 show transitions between past and current professional status for return migrants who were abroad one year before. Table 5.3 indicates that 79% of those who were self‑employed before returning have remained in this category after coming back to Romania, while 17% have become employees. Transitions in the other direction, from employee abroad to self‑employed in Romania, were much less frequent. Table 5.4 shows, for each current professional status, the distribution of past status: 74% of those self‑employed after coming back to Romania were already self‑employed abroad, while 24% were employees. For those who are employees in Romania, the transition from self‑employment was much less frequent, with only 7%. These results indicate that self‑employment is most likely a fallback option for many recent Romanian return migrants who do not manage to become employees.

Table 5.3. Distribution of current professional status according to past professional status (abroad) of return migrants aged 15‑64, 2015‑17

Note: 79% of return migrants who were self-employed abroad (one year before the survey) have remained self-employed after returning, while 17% have become employees.

Source: Romania EU labour force surveys, 2015‑17, Eurostat.

Table 5.4. Distribution of current professional status according to past professional status (abroad) of return migrants aged 15-64, 2015-17

|

Current status Past status (abroad)l |

Self-employed |

Employee |

Unemployed or inactive |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Self-employed |

74% |

7% |

3% |

|

Employee |

24% |

91% |

33% |

|

Unemployed or inactive |

2% |

2% |

64% |

|

Total |

100% |

100% |

100% |

Note: Panel B: 74% of return migrants who are self-employed after returning were self-employed abroad (one year before the survey), while 24% were employees.

Source: Romania EU labour force surveys, 2015‑17, Eurostat.

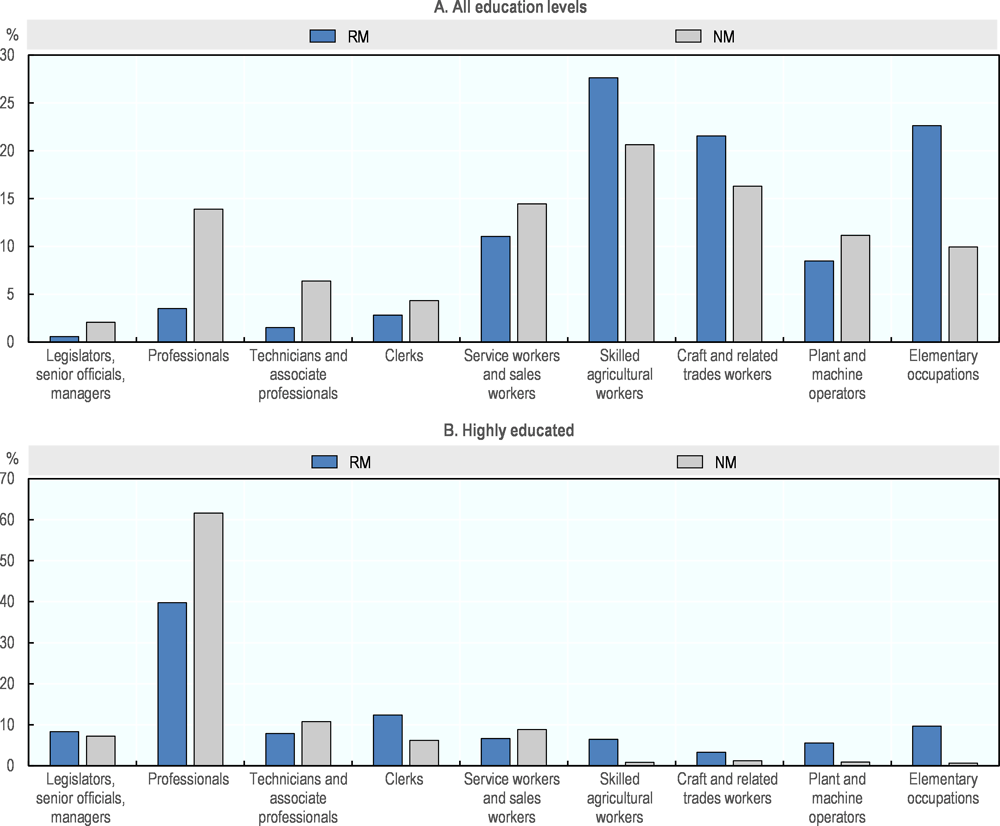

Beyond the alternative between self‑employment and salaried work, occupational choice is another key dimension of job quality, especially the matching between educational attainment and the skills required for the job. Comparing the distribution of occupations held by return migrants with that of non‑migrants is a first step to assess the position of return migrants on the Romanian labour market. In Figure 5.11, Panel A shows that return migrants are under‑represented in occupations requiring a high skill level, especially ‘Professionals’ and ‘Technicians and associate professionals’ (ISCO groups 2 and 3) where they are under‑represented by a factor of four compared to non‑migrants. In contrast, they are over‑represented in jobs with relatively low skill content, such as ‘Skilled agricultural workers’, ‘Craft and related trade workers’ (ISCO groups 6 and 7), and most importantly ‘Elementary occupations’ (ISCO group 9), where 23% of them work, while the employment share of non‑migrants in this group is less than 10%.

In Panel B of Figure 5.11, the distribution of employment by occupation is shown only for the highly educated. As discussed in Chapter 4, over‑qualification rates are particularly high for Romanian emigrants in OECD countries. This problem also affects return migrants: while 40% of employed highly educated return migrants have a job in the category ‘Professionals’, which require the highest skill level, this proportion is more than 50% higher among non‑migrants. Highly educated return migrants are also under‑represented in the ‘Technicians and associate professionals’, where less than 8% of them work, while the share among non‑migrants is 11%. More strikingly, there is a large number of highly educated return migrants who hold low‑skilled jobs: 25% of them work as ‘Skilled agricultural workers’, ‘Craft and related trade workers’, ‘Plant and machine operators’ (ISCO group 8) or in ‘Elementary occupations’, while this is the case for less than 4% of the highly educated non‑migrants. As a result, the overqualification rate of return migrants is 44%, almost as high as the one estimate for Romanian emigrants in OECD countries (see Chapter 4), while it is only 19% for non‑migrants.

The prevalence of self‑employment among low educated return migrants and the high overqualification rate of highly educated returnees are indicators of poor economic reintegration of many Romanian emigrants upon their return in their country of origin. Added to the lower employment rates of prime‑age men and tertiary educated returnees, compared to their non‑migrant counterparts, this paints a relatively bleak picture of their economic and social prospects in Romania.

Several factors can help explain this situation. First, emigration episodes can interrupt careers and therefore lead to lower country‑specific professional experience, which can harm employment prospects of prime‑age workers. Second, emigration can also disrupt personal relationships and weaken the networks in which emigrants were embedded in Romania before leaving. Considering the key role of social networks in job search, return migrants might therefore be at a disadvantage when looking for employment when they come back to Romania. Third, as discussed above, there is evidence that Romanian return migrants are negatively selected on unobserved characteristics, which would explain why some groups fare worse than non‑migrants on the labour market. Finally, large flows of returning migrants in the recent years may have led to a high level of competition for jobs among return migrants themselves, making it more difficult for them to find a job corresponding to their formal qualifications.

Figure 5.11. Distribution of employment by occupations for return migrants and non‑migrants in Romania, 2014

Source: Romania EU labour force survey, 2014, Eurostat.

Each year, Romanian emigrants send remittances amounting to 2% of GDP

In 2017, Romania received EUR 3.8 billion in remittances sent by Romanian emigrants abroad, corresponding to about 2% of GDP. Compared to neighbouring countries, this a relatively low level: according to World Bank data, remittances represented about 20% of GDP in Moldova, 14% in Ukraine, 9% in Serbia, 3.5% in Bulgaria and 3% in Hungary. These remittances may, however, represent significant financial resources for the origin households of Romanian emigrants.

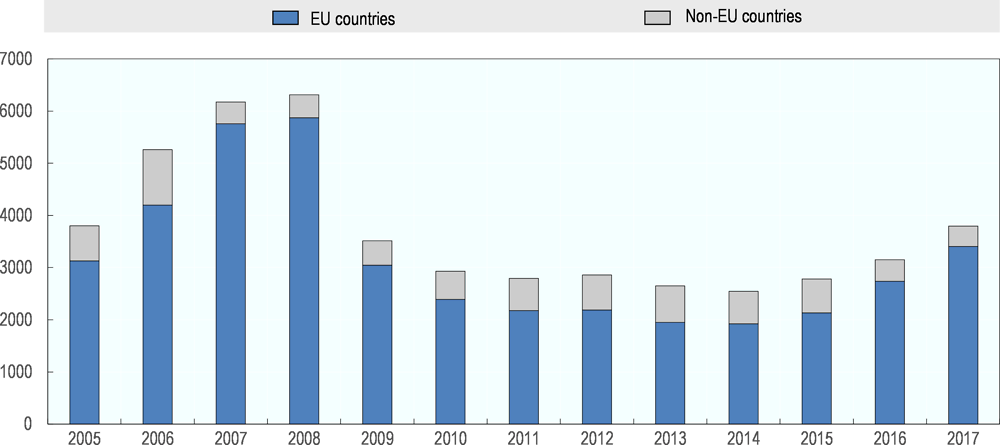

In line with the geographical distribution of the Romanian diaspora (see Chapter 1), 90% of remittances originated from EU countries (Figure 5.12). In the recent years, the level of remittances sent to Romania from abroad has been strongly affected by the economic crisis in the main destination countries of Romanian emigrants: while remittances increased by almost 70% between 2005 and 2008, they dropped very strongly after 2008, and only started to increase again in 2015.

Figure 5.12. Remittances to Romania sent from EU and non‑EU countries, 2005‑17

Note: Remittances include workers remittances and compensation of employees.

Source: Eurostat, balance of payment data.

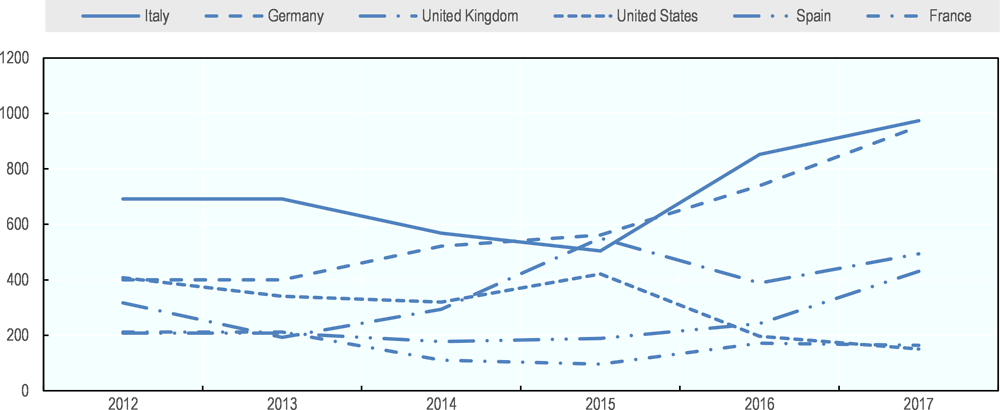

In 2017, the main sending countries were Italy and Germany, with close to EUR 1 billion each, the United Kingdom, with EUR 0.5 billion, Spain (EUR 0.4 billion), France and the United States (EUR 0.15 billion each) (Figure 5.13). Although changes across these key destination countries of Romanian emigrants in recent years partly reflected changes in migration flows, there were also significant differences in the average amount sent by Romanian emigrants in different destination countries. For example, Romanian emigrants aged 15‑64 living in Italy sent on average about EUR 700 per year in 2015/16, while those living in the United Kingdom sent on average around EUR 1 900. Among the main destination countries, the lowest average amount was sent by those living in Spain, with about EUR 450.7

Figure 5.13. Remittances to Romania sent from selected OECD countries, 2012‑17

Note: Remittances include workers remittances and compensation of employees.

Source: Eurostat, balance of payment data.

Conclusions

Large outflows of Romanian emigrants in the last 10 to 15 years towards OECD countries, especially EU Member States, have quite logically led to large flows of return migration to Romania. It is, however, quite challenging to determine exactly how large these return migration flows are. Indeed, free movement in the European Union has both increased opportunities for mobility for Romanian nationals, and reduced the ability to measure those flows. Mobility patterns have become more complex and more diverse, and the traditional tools used to apprehend return migration are insufficient to capture some of these movements. It is likely that more and more Romanian nationals will engage in complex migration trajectories, both within the European Union and outside.

This makes it particularly challenging to accompany efficiently return migrants in their reintegration in Romania. Indeed, in order to develop and implement specific policies that could help return migrants who are struggling to find adequate employment in the country, for example, it is necessary to adequately identify the characteristics of this population, and to understand the constraints they face on the labour market, but also in other dimensions of their life in Romania.

This chapter provides some insights on these topics. As noted above, an important limitation concerns the measurement of return migration to Romania. Developing a multi‑country survey targeting specifically Romanian emigrants and returnees to better understand their diverse migration trajectories would be a very useful step to overcome this issue.

References

[4] Ambrosini, J. et al. (2015), “The selection of migrants and returnees in Romania: Evidence and long-run implications”, Economics of Transition, Vol. 23/4, pp. 753-793, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ecot.12077.

[6] Anghel, R. et al. (2016), International Migration, Return Migration, and their Effects: A Comprehensive Review on the Romanian Case, http://www.iza.org.

[1] Bonifazi, C. and A. Paparusso (2018), “Remain or return home: The migration intentions of first-generation migrants in Italy”, Population, Space and Place, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/psp.2174.

[3] Ciobanu, R. (2015), “Multiple Migration Flows of Romanians”, Mobilities, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2013.863498.

[8] de Coulon, A. and M. Piracha (2005), “Self-selection and the performance of return migrants: the source country perspective”, Journal of Population Economics, Vol. 18/4, pp. 779-807, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0004-4.

[2] de Coulon, A., D. Radu and M. Steinhardt (2016), “Pane e Cioccolata: The Impact of Native Attitudes on Return Migration”, Review of International Economics, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/roie.12212.

[12] Dustmann, C. and O. Kirchkamp (2002), “The optimal migration duration and activity choice after re-migration”, Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 67/2, pp. 351-372, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3878(01)00193-6.

[10] Marchetta, F. (2012), “Return Migration and the Survival of Entrepreneurial Activities in Egypt”, World Development, Vol. 40/10, pp. 1999-2013, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.05.009.

[5] Martin, R. and D. Radu (2012), “Return Migration: The Experience of Eastern Europe”, International Migration, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2012.00762.x.

[9] OECD (2010), Open for business: Migrant entrepreneurship in OECD countries, OECD Publishing.

[7] OECD (2008), “Return Migration: A New Perspective”, in International Migration Outlook 2008, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2008-7-en.

[11] Piracha, M. and F. Vadean (2010), “Return Migration and Occupational Choice: Evidence from Albania”, World Development, Vol. 38/8, pp. 1141-1155, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.12.015.

Notes

← 1. By definition, the Romanian emigrants who have left Italy – and who were more likely to have always intended to leave – were not surveyed.

← 2. The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union defines freedom of movement for workers as “the abolition of any discrimination based on nationality between workers of the Member States as regards employment, remuneration and other conditions of work and employment” (Art. 45).

← 3. The relevant question was only asked to individuals aged 15‑64.

← 4. Emigrants born in Romania and having acquired Italian citizenship are not counted here, as it is not possible to distinguish them from Italians born in Italy and moving to Romania.

← 5. The same calculation to correct for gender differences in employment rates, applied specifically to migrants returning from Italy, would raise the share of women to 45%, versus 40% without this correction.

← 6. The model estimated includes direct effects of sex, age, education and return status, as well as an interaction between educational attainment and the return variable.

← 7. This average amount is computed by dividing the total remittances sent by the number of Romanian emigrants aged 15‑64.