Digital technologies are rapidly being ingrained in all government activities and processes. As a result, the size and prevalence of investments in public information and communication technology (ICT) are becoming more important in countries’ national budgets. Strategic planning is necessary to optimise public ICT expenditures in order to secure efficiency, coherence and sustainability, avoiding gaps and/or duplications that typically result from siloed approaches. The public sector’s capacity to measure the economic benefits of ICT expenditures for central government, for citizens and for businesses can therefore contribute to better informed policies and practices for ICT investments.

Governments also face the challenge of processing increasingly diverse and complex digital technologies. They need simple, agile business case methodologies to identify the value proposition of ICT investments across different sectors and levels of government in a context of permanently evolving technological trends. Standardised project management models are also needed for the public sector to consistently follow project and initiative lifecycles, allowing for coherence and synergies across different government sectors and ensuring that the expected benefits are realised.

The Government of New Zealand provides an interesting example in the region of how ICT investments and capabilities could be managed. It requires public sector organisations to submit their strategic plans for review by the government Chief Information Officer (CIO), specifying the investments plans as well. The government CIO has the mandate and responsibility to advise public sector organisations to adopt advantageous cross-cutting government initiatives and shared services.

Three of the ten SEA countries – Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand – measure the direct financial benefits of ICT projects within their respective central governments. Malaysia, Singapore and Viet Nam each measure the financial benefits for businesses and for citizens. The four OECD countries in the region (Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand) all measure the direct financial benefits within central governments. Among the regional OECD countries, only Japan measures the expected benefits for both businesses and citizens, while New Zealand measures benefits for citizens only.

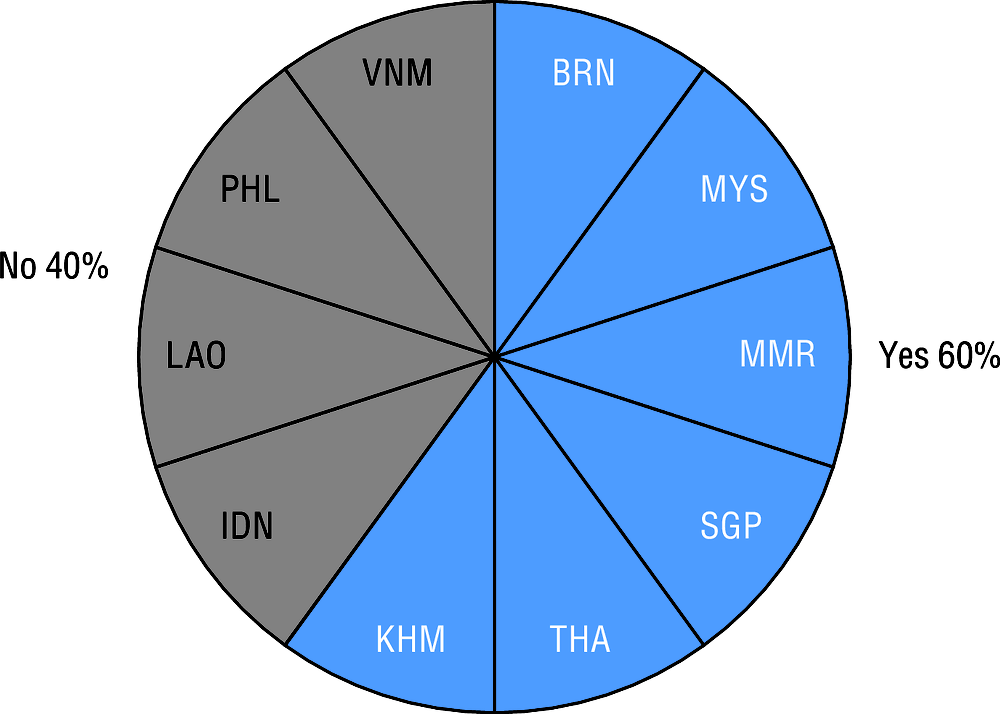

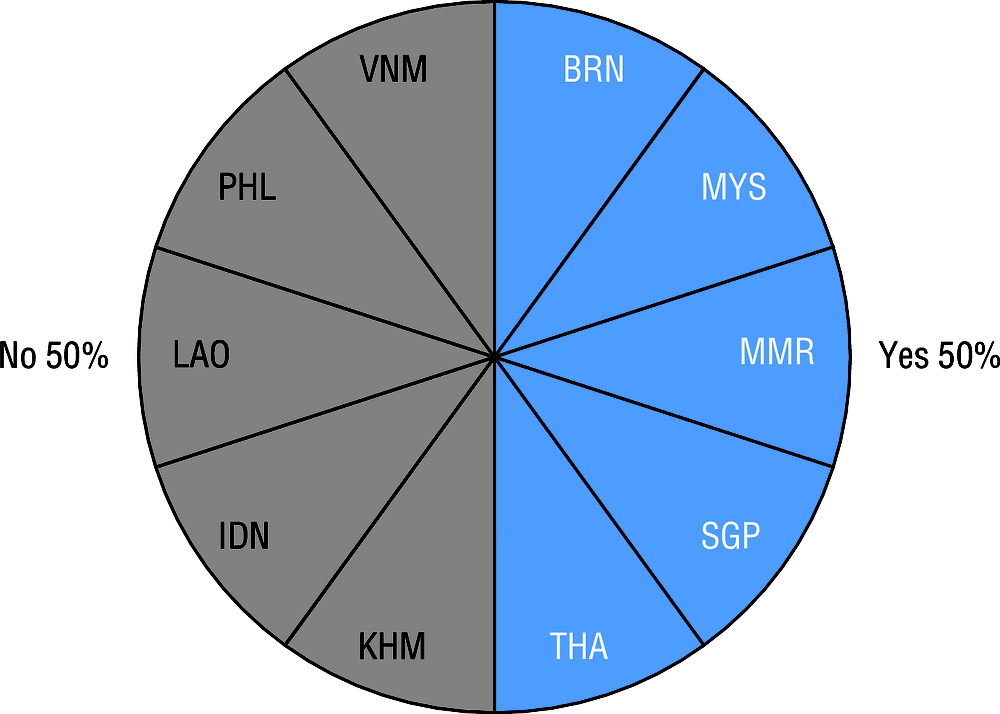

On the use of business cases to better estimate and evaluate ICT investments, 60% of the SEA countries declare the existence and use of a standardised model at national level, which is in line with OECD countries (58%, 2014). In Brunei Darussalam, a centralised approach to approve ICT investments supports the government in overseeing and ensuring coherence on digital government cross-sector efforts. Half of the countries also have a standardised model for ICT project management in central government. The Philippines has a standardised model for presenting business cases, but not specifically on ICT project management. Five countries have both policy levers in place – Brunei Darussalam, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore and Thailand – reflecting a substantial level of maturity in planning ICT projects and initiatives. This impacts on government’s capacity to co-ordinate and secure coherent and sustainable public sector ICT expenditures.

The positive experiences of more digitally advanced countries in the region – in measuring financial benefits and using standardised ICT business cases and project management methods – could inspire other countries to improve ICT investments planning and management as an essential component of sound digital government policies.