A country’s fiscal balance is the difference between government revenues and expenditures. A fiscal deficit occurs when, in a given year, a government spends more than it receives in revenues. When fiscal deficits occur recurrently, the shortages are offset with debt accumulation. Over time, growing debt levels increase the burden of capital and interest payments and could send negative signals to international financial markets, affecting the sustainability of public finances. A complementary indicator of a country’s fiscal situation is the primary balance: the difference between the fiscal balance and the primary balance reflects the relative weight of interest payments within government accounts.

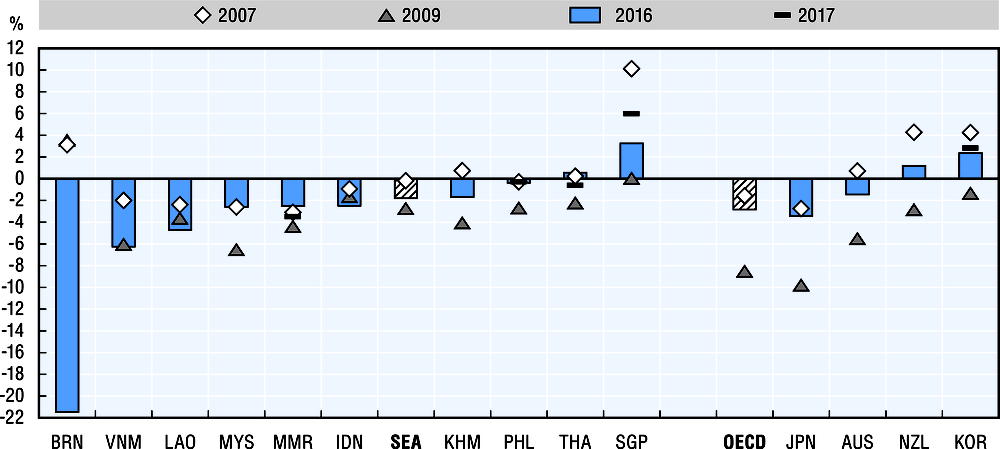

In 2009 the average deficit in SEA countries reached 2.73% of GDP. This fell to 1.79% in 2016, but still indicates a weaker fiscal position than in 2007, when on average SEA countries were close to having balanced budgets (average deficit 0.19%). The 2009-16 SEA fiscal balance improvements can be explained by relatively high levels of economic growth, e.g. higher than OECD member countries (average deficit 2.8% in 2016), allowing room to maintain a growing pattern of nominal expenditures. In turn, a positive trade balance (difference between exports and imports), high investment levels and resilient domestic consumption have triggered growth in SEA countries.

Still, the latest available data show a wide variation in the fiscal balance across SEA countries, from a deficit of 21.5% in Brunei Darussalam to a surplus of 3.26% in Singapore in 2016. Both are influenced by changes in the global economic landscape; Brunei Darussalam was affected by the steep slide in energy (i.e. oil and gas) prices, and Singapore is benefitting from the upswing of manufacturing and trade-related services, reflected in an even higher fiscal balance figure in 2017 (a surplus of 5.97% of GDP).

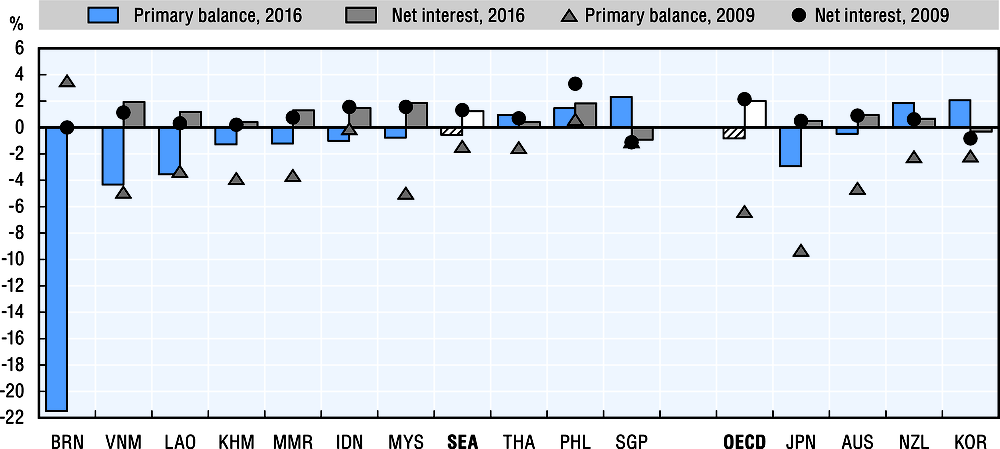

A negative primary balance means that further debt must be contracted to finance interest payments. According to 2016 data, SEA countries experienced an average primary deficit of 0.56% of GDP and interest payments amounted to 1.24% of GDP, lower than the OECD average (2.01%), but higher than OECD neighbouring countries (i.e. Australia, Japan, New Zealand and Korea). In general, SEA countries have conducted expansionary fiscal policies recently to finance the infrastructure spending needed to keep up the pace of economic growth. While SEA countries’ overall fiscal positions are stable, reducing the primary deficit would strengthen fiscal sustainability and increase resilience to future economic shocks. Like the 2009-16 period, further reductions of the primary balance and net interest payments are expected for most SEA countries in the years ahead.

Yet not all SEA countries are running primary deficits. In 2016, Singapore (2.33%), the Philippines (1.46%) and Thailand (0.97%) experienced primary surpluses; while Brunei Darussalam (21.48%), Viet Nam (4.33%) and Lao PDR (3.55%) ran the largest primary deficits. Brunei Darussalam has a small debt and relies substantially on reserves to fund financial resource shortages. In 2009-16, both Viet Nam and Lao PDR had a persistent gap in public finances (i.e. public expenditures growing faster than public revenues; see 2.4 2.6) and a consequent high reliance on public debt.